Abstract

Objectives:

To determine if any presenting symptoms are associated with aspiration risk, and to evaluate the reliability of clinical feeding evaluation (CFE) in diagnosing aspiration compared with videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS).

Study design:

We retrospectively reviewed records of children under 2 years who had evaluation for oropharyngeal dysphagia by CFE and VFSS at Boston Children’s Hospital and compared presenting symptoms, symptom timing, and CFE and VFSS results. We investigated the relationship between symptom presence and aspiration using the Fisher exact test and stepwise logistic regression with adjustment for comorbidities. CFE and VFSS results were compared using the McNemar test. Intervals from CFE to VFSS were compared using the Student t-test.

Results:

412 subjects with mean (±SD) age 8.9±6.9 months were evaluated. No symptom, including timing relative to meals, predicted aspiration on VFSS. This lack of association between symptoms and VFSS results persisted even in the adjusted multivariate model. The sensitivity of CFE for predicting aspiration by VFSS was 44%. Patients with a reassuring CFE waited 28.2±8.5 days longer for confirmatory VFSS compared with those with a concerning CFE (P < .05).

Conclusions:

Presenting symptoms are varied in patients with aspiration and cannot be relied upon to determine which patients have aspiration on VFSS. The CFE does not have the sensitivity to consistently diagnose aspiration so a VFSS should be performed in symptomatic patients.

Keywords: Oropharyngeal dysphagia, videofluoroscopic swallow study, clinical feeding evaluation, pediatrics

Infants and children are typically referred for swallow evaluation if they have signs or symptoms suspicious for aspiration1–3. These symptoms typically include coughing, choking, eyes turning red, difficulty feeding or changes in color with feeding4. Little is known about the actual correlation between presenting symptoms and the risk of finding aspiration either by clinical feeding evaluation (CFE) or videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS)4, 5. The CFE typically consists of assessing feeding with one or more textures (eg, thin, nectar, honey thick or purees) using one or more methods of feeding (e.g. bottle, cup, spoon) by a speech-language pathologist (SLP) specializing in the treatment of pediatric dysphagia and feeding disorders3, 6. A VFSS typically involves similar trials though the feeding is assessed using fluoroscopy of the oropharynx, larynx and upper esophagus to determine if there is evidence of aspiration7–9. There is limited data on the sensitivity of CFE compared with the VFSS to assess for aspiration risk and prior studies have only included small numbers of patients4, 5, 10–13.

Objective assessment of swallow function is critical in children with chronic respiratory symptoms because some of the classic signs of aspiration such as aspiration pneumonia are rare, occurring in less than 10% of children14–16. Determining the best method to assess for aspiration risk is not known and each method has pros and cons. The VFSS can assess if there is direct aspiration or laryngeal penetration because the airways are visualized, but involves radiation exposure17–19. Although the CFE does not involve radiation risk, it can only identify signs and symptoms during feeding. This is not ideal because more than 80% of pediatric aspiration is silent and therefore occurs without overt clinical signs11, 20–22. Choosing the most sensitive test is critical because inadequately treated aspiration can lead to a variety of poor outcomes including pulmonary injury, failure to thrive and oral aversion1, 23–25. The aim of this study was to describe the range of symptoms in children presenting for both CFE and VFSS and determine if any presenting symptoms, and the timing of those symptoms relative to meals, could predict aspiration risk in the pediatric population. An additional aim was to determine the reliability of the CFE in making the diagnosis of aspiration compared with VFSS in children.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the records of all children under 2 years of age who had both a CFE and VFSS for the evaluation of oropharyngeal dysphagia at Boston Children’s Hospital in 2015. Records were reviewed for patient characteristics, comorbidities and swallow study characteristics including radiation dose. VFSS results were considered abnormal if there was evidence of aspiration or laryngeal penetration seen for any texture. Laryngeal penetration was considered abnormal based on our clinical experience that these patients have similar outcomes to patients with frank aspiration14, 26. All CFEs were performed by speech language pathologists specializing in pediatric dysphagia and all VFSS were performed by SLPs in conjunction with pediatric radiologists. The CFE and VFSS exams were performed in standard fashion, starting with evaluation of thin liquids followed by increasing the thickness of liquids delivered in stepwise fashion (from thin to nectar to honey to puree) if there is concern for aspiration/penetration, as previously described6–9.

The primary aims were to determine if presenting symptoms could determine which patients would be at greatest risk for having an abnormal VFSS and whether the CFE could reliably predict aspiration or laryngeal penetration such that radiation exposure might be avoided. Presence of symptoms was obtained from the medical record based on parental and SLP report and included gastrointestinal symptoms and pulmonary symptoms in addition to how symptoms were related to meals (during, after, or both). We first described the prevalence of presenting symptoms in this cohort and then used the Fisher exact test to determine if there was any association between each individual symptom and the result of each subject’s CFE and VFSS. A stepwise logistic regression model was used to determine symptoms independently associated with CFE and VFSS, after adjustment for age at VFSS, male sex, and all comorbidities (neurologic, cardiac, metabolic, immunologic, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, prematurity). Firth’s penalized maximum likelihood estimation was used to reduce bias due to sparse table cells27. Additionally, a multiple logistic regression model containing all presenting symptoms, adjusted for age at VFSS, male sex, and comorbidities (neurologic, cardiac, metabolic, immunologic, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, prematurity), using Firth’s penalized maximum likelihood estimation, was used to obtain Wald chi-square results and p-values in order to put all symptoms in a single model to determine the relative strength of each effect.

We next compared the dichotomous assessment (normal vs abnormal) of CFE to VFSS as the gold standard to report test characteristics, including sensitivity, specificity, positive predicted value, and negative predicted value with 95% confidence interval, and used the McNemar test to assess the concordance between these 2 modalities. Lastly we used the Student t-test to compare the time in days from initial CFE with initial VFSS for subjects who were ultimately found to have aspiration in order to determine the delay in aspiration diagnosis as a result of having a normal CFE. Data are presented as mean ± standard error and % (n) unless indicated otherwise. Data were analyzed using SPSS and multivariate analysis was conducted with SAS (Cary, NC).

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Results

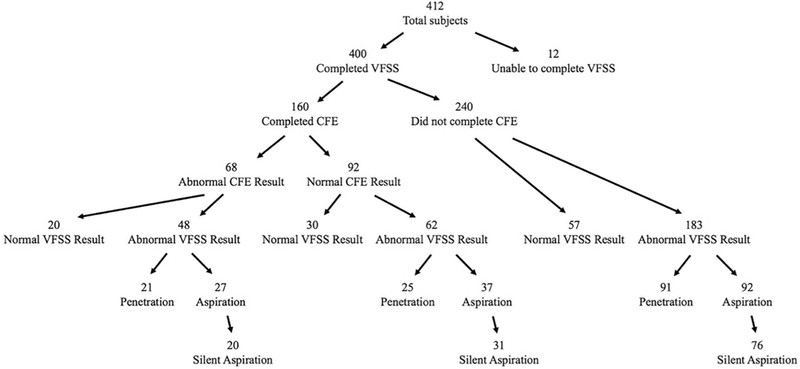

We evaluated 412 total subjects with a mean age of 8.9 ± 6.9 months, all of whom had VFSS performed; 160 of these had both CFE and VFSS performed. Within the entire cohort, 38% (n=156) of the VFSS showed aspiration, 33% (n=137) showed penetration alone, and 27% (n=107) did not show evidence of aspiration or penetration; 3% (n=12) of subjects were unable to complete their VFSS. Subject characteristics, symptoms present at the time of referral, and subject comorbidities are shown in Table I. Notably, subjects were symptomatic for a mean (±SD) of 5.3 ± 5.0 months prior to their first formal swallow evaluation. Overall, 29% of the subjects had a neurologic comorbidity and 32% of the subjects were premature with a mean gestational age of 31.9±0.3 months. A flow diagram of the patient population, including the overall rates of swallow testing by VFSS and CFE and the results of these evaluations, is shown in the Figure.

Table 1: Subject Characteristics and Presenting Symptoms.

Baseline characteristics, VFSS results, and comorbidities are shown above. There were varied presenting symptoms for the cohort overall and those with abnormal and normal VFSS results are shown. Data are expressed as percentage (n) and mean ± standard error.

| All Subjects (n=412) | Abnormal VFSS (n=293) | Normal VFSS (n=107) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 59% (243) | 60% (177) | 55% (59) |

| Age at VFSS | 9.0 ± 0.4 | 8.8 ± 0.4 | 8.8 ± 0.7 |

| Duration of Symptoms Prior to VFSS | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.9 |

| Abnormal VFSS Result | 71% (293) | 100% (293) | 0% (0) |

| Aspiration | 38% (156) | 38% (156) | 0% (0) |

| Silent Aspiration | 81% (127/156) | 81% (127/156) | 0% (0) |

| Penetration | 33% (137) | 33% (137) | 0% (0) |

| Comorbidities Neurologic | 29% (120) | 31% (90) | 27% (25) |

| Cardiac | 11% (46) | 11% (33) | 9% (10) |

| Metabolic | 13% (53) | 13% (37) | 13% (14) |

| Immunologic | 1% (3) | 1% (2) | 1% (1) |

| Pulmonary | 14% (58) | 16% (46) | 11% (12) |

| Gastrointestinal | 21% (81) | 17% (50) | 26% (28) |

| Prematurity | 32% (130) | 34% (100) | 27% (29) |

| GI Symptoms Choking/Gagging | 37% (153) | 38% (112) | 36% (38) |

| Regurgitation | 29% (121) | 28% (81) | 33% (35) |

| Vomiting | 27% (112) | 25% (72) | 33% (35) |

| Poor Feeding | 23% (94) | 22% (63) | 26% (28) |

| Slow Feeding | 6% (24) | 6% (16) | 8% (8) |

| Pulmonary Symptoms Coughing | 58% (239) | 59% (173) | 52% (56) |

| Noisy Breathing | 25% (104) | 28% (81) | 20% (21) |

| Congestion | 21% (87) | 20% (58) | 24% (26) |

| Spells | 17% (68) | 18% (53) | 14% (15) |

| Respiratory Distress | 12% (50) | 13% (38) | 11% (12) |

| Recurrent Pneumonia | 11% (44) | 12% (34) | 7% (7) |

| Oxygen Requirement | 5% (19) | 6% (16) | 3% (3) |

| Relationship to Meals Only During | 53% (217) | 55% (162) | 46% (49) |

| Only After | 8% (34) | 9% (25) | 8% (9) |

| During and After | 21% (87) | 20% (58) | 24% (26) |

| No Relationship to Meals | 18% (74) | 16% (48) | 22% (23) |

Figure: Study Population.

The flow diagram above shows the numbers of subjects in each group, including the overall rates of swallow testing by VFSS and CFE and the results of these evaluations.

234 patients had radiation exposure reported in the VFSS results, with a mean exposure of 1.98 ± 1.30 mGy. There were significantly lower exposure values in subjects with normal VFSS (1.54 ± 0.12 mGy) compared with those with an abnormal VFSS (2.20 ± 0.11 mGy, p<0.0001).

The association between individual symptoms and VFSS results are shown in Table 2. No single symptom predicted risk of aspiration (all p≥0.05) by VFSS; even timing of symptoms relative to meals did not predict aspiration risk. In contrast, symptoms of coughing (odds ratio (OR) 2.67, 95% CI 1.4–5.09, p=0.003), choking/gagging (OR 2.412, 95% CI 1.248–4.666, p=0.012), noisy breathing (OR 2.55, 95% CI 1.135–5.730, p=0.025), and the presence of symptoms during meals (OR 3.36, 95% CI 1.37–8.26, p=0.008) were significantly associated with CFE results suggesting that presenting symptoms may bias results of the CFE which did not then correlate with the VFSS.

Table 2: Association between Presenting Symptoms and VFSS.

Odds ratio (OR) for each presenting symptom and abnormal VFSS results are shown above. No single clinical symptom predicted risk of aspiration by VFSS. However, symptoms of choking/gagging, coughing, noisy breathing, and symptoms during meals were significantly correlated with CFE results but not with the gold standard VFSS results.

| GI Symptoms | VFSS Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR for Abnormal VFSS | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | |

| Choking/Gagging (n=150) | 1.12 | 0.71–1.78 | 0.64 |

| Reflux (n=116) | 0.79 | 0.49–1.27 | 0.32 |

| Vomiting (n=107) | 0.67 | 0.41–1.09 | 0.13 |

| Poor Feeding (n=91) | 0.77 | 0.46–1.29 | 0.35 |

| Slow Feeding (n=24) | 0.72 | 0.30–1.72 | 0.49 |

| Pulmonary Symptom | VFSS Result | ||

| OR for Abnormal VFSS | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | |

| Coughing (n=229) | 1.31 | 0.84–2.05 | 0.25 |

| Noisy Breathing (n=102) | 1.57 | 0.91–2.69 | 0.12 |

| Congestion (n=84) | 0.77 | 0.45–1.30 | 0.33 |

| Spells (n=68) | 1.35 | 0.73–2.52 | 0.37 |

| Respiratory Distress (n=50) | 1.18 | 0.59–2.35 | 0.73 |

| Recurrent Pneumonia (n=41) | 1.88 | 0.81–4.37 | 0.19 |

| Oxygen Requirement (n=19) | 2.00 | 0.57–7.01 | 0.43 |

| Relationship to Meals | VFSS Result | ||

| OR for Abnormal VFSS | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | |

| During Meals (n=295) | 1.38 | 0.84–2.27 | 0.24 |

| After Meals (n=119) | 0.80 | 0.50–1.29 | 0.39 |

| During and After Meals (n=84) | 0.78 | 0.46–1.32 | 0.41 |

No presenting symptoms were associated with an abnormal VFSS result even when combined in a multivariate model with adjustment for comorbidities, as shown in Table 3. A best-fitting model by stepwise regression identified only gastrointestinal comorbidity as independently associated with abnormal VFSS (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.33–0.96, p=0.03). A similar model identified neurologic comorbidity, vomiting and slow feeding as independently associated with aspiration on VFSS (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.34–3.31, p=0.001 for neurologic comorbidity, OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.36–0.97, p=0.04 for vomiting, and OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.09–0.85, p=0.02 for slow feeding).

Table 3: Association between Presenting Symptoms and VFSS after Adjustment for Comorbidities.

No symptoms were associated with VFSS results even when assessed in a multivariate model with adjustment for comorbidities. Data are expressed as n (percentage). Punadjusted by the Fisher exact test. Padjusted by a logistic regression model containing a single symptom, adjusted for age at VFSS, male sex, and comorbidities (neurologic, cardiac, metabolic, immunologic, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, prematurity), using Firth’s penalized maximum likelihood estimation to reduce bias due to sparse table cells.

| Symptom | VFSS Result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (n=107) | Abnormal (n=293) | Punadjusted | Padjusted | |

| Choking/Gagging | 38 (35.5%) | 112 (38.2%) | 0.64 | 0.44 |

| Reflux | 35 (32.7%) | 81 (27.7%) | 0.32 | 0.43 |

| Vomiting | 35 (32.7%) | 72 (24.6%) | 0.13 | 0.27 |

| Poor feeding | 28 (26.2%) | 63 (21.5%) | 0.35 | 0.44 |

| Slow feeding | 8 (7.5%) | 16 (5.5%) | 0.49 | 0.34 |

| Coughing | 56 (52.3%) | 173 (59.0%) | 0.25 | 0.16 |

| Noisy Breathing | 21 (19.6%) | 81 (27.7%) | 0.12 | 0.15 |

| Congestion | 26 (24.3%) | 58 (19.8%) | 0.33 | 0.45 |

| Spells | 15 (14.0%) | 53 (18.1%) | 0.37 | 0.36 |

| Respiratory Distress | 12 (11.2%) | 38 (13.0%) | 0.73 | 0.90 |

| Recurrent Pneumonia | 7 (6.5%) | 34 (11.6%) | 0.19 | 0.24 |

| Oxygen Requirement | 3 (2.8%) | 16 (5.5%) | 0.43 | 0.54 |

| During Meals | 75 (70.1%) | 220 (75.1%) | 0.24 | 0.28 |

| After Meals | 36 (33.6%) | 83 (28.3%) | 0.39 | 0.38 |

| During and After Meals | 26 (24.5%) | 58 (20.2%) | 0.41 | 0.43 |

No presenting symptoms were associated with abnormal VFSS result even when combined in a multiple logistic model using Wald chi-square analysis (all p>0.08).

There was poor agreement between the two assessments of swallow function by the McNemar test (p<0.0001). Even when we only included those patients with aspiration (excluding patients with penetration only) on VFSS, there was still poor agreement (p=0.03). Follow-up CFEs compared with follow-up VFSS testing were also found to show poor concordance (p=0.0004). Using the VFSS as a gold standard, the CFE had a sensitivity 44% (34 – 53), specificity 60% (45 – 74), positive predictive value 71% (62 – 78), and negative predictive value 33% (27 – 39) for predicting aspiration. Similar results were found even when we only compared CFE for those patients with aspiration (without penetration) on VFSS, with sensitivity 42% (30 – 55), specificity 60% (45 – 74), positive predictive value 58% (46 – 68), and negative predictive value 45% (37 – 53).

The time from the initial CFE to VFSS was 55.9 ± 8.5 days on average in patients with a CFE that did not raise concerns for aspiration. In contrast, in patients in whom the CFE was concerning for aspiration, there was a mean 27.7 ± 7.6-day time lag between CFE and the VFSS, which was significantly shorter than in patients with a CFE that did not raise concerns. Therefore, patients with a reassuring CFE waited 28.2±8.5 days longer for confirmatory VFSS compared with those with a concerning CFE (p<0.05).

Discussion

In the present study we evaluated presenting symptoms for children under 2 years of age who had their first CFE and VFSS, and compared the agreement between these two modes of swallow evaluation, and determined the ability of each presenting symptom to predict VFSS and CFE results. We found that there was no single symptom that could reliably predict which patients would have evidence of aspiration on VFSS and this translates to decreased sensitivity of the CFE compared with the VFSS.

Relatively few studies have examined the presentation and epidemiology of swallowing dysfunction in young children; this remains both an under-studied and under-appreciated area in clinical pediatrics and the prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia appears to be increasing due to increased survival of premature infants and other children with chronic medical problems 2, 28, 29. We focused our study on infants and children under age 2 because this group has the highest rate of oropharyngeal dysphagia of any pediatric age group. Additionally, their symptoms are often non-specific, making diagnosis and management difficult for the general or specialist provider 1, 30. Pediatricians frequently treat patients with swallowing dysfunction with medications for reflux, perhaps due to frequent symptom overlap, which might do more harm than good 31, 32. Our group recently showed that oropharyngeal dysphagia and aspiration are associated with brief resolved unexplained events (BRUE, formerly known as apparent life threatening events), suggesting that this disorder may play a significant role in common pediatric events 12. In most cases, oropharyngeal dysphagia with aspiration can be treated with thickening of feeds in the great majority of pediatric patients, and continued oral feeding with thickened liquids has superior outcomes than feeding with enteral tubes33. However, in order to treat oropharyngeal dysphagia appropriately, it first must be diagnosed correctly.

Weir et al have consistently shown the high prevalence of silent aspiration in the pediatric population and suggested the need to consider VFSS to appropriately diagnose oropharyngeal dysphagia, but this practice has not become standard of care in many pediatric centers4, 11. Svystun et al recently reviewed their cohort of 128 otherwise healthy children with aspiration and described the range of presentations in addition to varied diagnostic and management strategies in this patient population with similar age range and rates of VFSS abnormalities 5. They reported choking, coughing and respiratory distress in more than 60% of their patients and also notably found vomiting as a presenting symptom in 26% of their cohort. In contrast to our results, however, they did find an association between recurrent pneumonia and abnormal VFSS5. Several groups have examined characteristics of children with swallowing dysfunction and consistently identified neurologic impairment as a major risk factor as we have shown in the current study 30, 34.

Many of what have traditionally been thought of as typical presenting symptoms of aspiration, such as recurrent pneumonia, were actually relatively infrequent in this cohort, and symptoms that are not typically considered, such as vomiting, were more common. Additionally, almost one-third of patients had symptoms either only after meals or both during and after meals, which may explain why oropharyngeal dysphagia with aspiration is so frequently misdiagnosed as gastroesophageal reflux disease. These varied symptoms suggest that providers should be mindful of the myriad presentations of oropharyngeal dysphagia in this age group.

Our results also show that one third of children with a normal CFE were actually found to have aspiration on VFSS. Because of the high prevalence of silent aspiration in children, patients with persistent symptoms, even with a reassuring CFE, may still need a VFSS to diagnose aspiration. A high index of suspicion is needed if symptoms persist to order a VFSS to avoid a delay in diagnosis. A systematic review showed poor agreement between the CFE and VFSS but even the largest study included only 91 subjects 35. Other research groups have attempted to modify the approach to the CFE to improve its accuracy but even the addition of maneuvers such as cervical auscultation have not been shown to improve its sensitivity to the extent that the CFE could be used in isolation 36.

In addition to merely assessing for the presence or absence of aspiration, there are multiple other components to the clinical feeding evaluation that should be considered. The CFE assesses the oral phase of swallowing to evaluate oral structures and document current oral motor skill level and developmental feeding skills. The CFE also assesses the patient’s ability to receive, contain and propel the bolus to determine appropriate diet level6. Therefore, the CFE remains a valuable tool that contributes significantly to the management of these patients.

There are a number of practical implications from our findings. First, specific presenting symptoms cannot be relied on in our pre-test consideration of whether a child will be found to have aspiration on their swallow study. None of the common symptoms predicted aspiration and, conversely, none of the symptoms ruled-out aspiration. Additionally, providers should not be fully reassured by a normal CFE in the case of troublesome or ongoing symptoms. Another important finding was the relatively low radiation exposure involved in obtaining VFSS, especially in children who go on to have a normal VFSS result. Our results suggest that the exposure is significantly less than an upper GI series17. Pediatric radiologists continue to work with SLPs to minimize radiation in performing these studies and other groups have already shown that radiation exposure can be decreased in the performance of VFSS 17, 18, 37. Lastly, the children in our study were symptomatic for a mean of more than 5 months prior to having formal swallow evaluation performed, suggesting there might be room for earlier diagnosis of oropharyngeal dysphagia, which might prevent morbidity. A multidisciplinary approach for these patients is essential to optimize their care, limit unnecessary testing and maximize their future pulmonary and feeding outcomes3, 23, 38.

There are a number of limitations to the present study which should be considered. First, the retrospective nature of the study makes it difficult to know if there might be other historical characteristics or presenting features that might reliably discriminate between different presentations of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Additionally, we only had records for those patients who ultimately went on to receive a videofluoroscopic swallow study and therefore might be missing some proportion of patients who only had a clinical evaluation because of the mild degree of symptoms or in whom their symptoms could be modified by changes in feeding techniques such as pacing without needing a VFSS. Lastly, the children in the study all received their care at a tertiary children’s hospital, which might bias the study group towards a more medically complex population. However, the majority of the subjects included did not have any comorbidities and we did control for these in our multivariate model.

Presenting symptoms are varied in patients with aspiration and these symptoms cannot be relied upon to determine which patients have oropharyngeal dysphagia and aspiration. The evaluation of oropharyngeal dysphagia in young children should always include an objective assessment of VFSS as clinical feeding evaluations are inadequate to assess swallow function and lead to delays in making a diagnosis of aspiration.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Translational Research Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, NIH R01 DK097112-01, and NIH T32 DK007477-33.

List of Abbreviations

- CFE

Clinical feeding evaluation

- SLP

Speech-Language Pathologist

- VFSS

Videofluoroscopic swallow study

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Portions of this study were presented at Digestive Diseases Week, May 6–9, 2017, Chicago, Illinois and the NASPGHAN Annual Meeting, November 1–4, 2017, Las Vegas, Nevada.

References

- [1].Lefton-Greif MA, Carroll JL, Loughlin GM. Long-term follow-up of oropharyngeal dysphagia in children without apparent risk factors. Pediatric pulmonology 2006;41:1040–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Vaquero-Sosa E, Francisco-Gonzalez L, Bodas-Pinedo A, Urbasos-Garzon C, Ruiz-de-Leon-San-Juan A. Oropharyngeal dysphagia, an underestimated disorder in pediatrics. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2015;107:113–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Durvasula VS, O’Neill AC, Richter GT. Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in children: mechanism, source, and management. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America 2014;47:691–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Weir K, McMahon S, Barry L, Masters IB, Chang AB. Clinical signs and symptoms of oropharyngeal aspiration and dysphagia in children. The European respiratory journal 2009;33:604–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Svystun O, Johannsen W, Persad R, Turner JM, Majaesic C, El-Hakim H. Dysphagia in healthy children: Characteristics and management of a consecutive cohort at a tertiary centre. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology 2017;99:54–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rangarathnam B, McCullough GH. Utility of a Clinical Swallowing Exam for Understanding Swallowing Physiology. Dysphagia 2016;31:491–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jadcherla SR, Stoner E, Gupta A, Bates DG, Fernandez S, Di Lorenzo C, et al. Evaluation and management of neonatal dysphagia: impact of pharyngoesophageal motility studies and multidisciplinary feeding strategy. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 2009;48:186–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hiorns MP, Ryan MM. Current practice in paediatric videofluoroscopy. Pediatric radiology 2006;36:911–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Arvedson JC, Lefton-Greif MA. Instrumental Assessment of Pediatric Dysphagia. Seminars in speech and language 2017;38:135–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Newman LA, Keckley C, Petersen MC, Hamner A. Swallowing function and medical diagnoses in infants suspected of Dysphagia. Pediatrics 2001;108:E106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Weir KA, McMahon S, Taylor S, Chang AB. Oropharyngeal aspiration and silent aspiration in children. Chest 2011;140:589–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Duncan DR, Amirault J, Mitchell PD, Larson K, Rosen RL. Oropharyngeal Dysphagia Is Strongly Correlated With Apparent Life-Threatening Events. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 2017;65:168–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Silva-Munhoz Lde F, Buhler KE, Limongi SC. Comparison between clinical and videofluoroscopic evaluation of swallowing in children with suspected dysphagia. CoDAS 2015;27:186–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Serel Arslan S, Demir N, Karaduman AA. Both pharyngeal and esophageal phases of swallowing are associated with recurrent pneumonia in pediatric patients. The clinical respiratory journal 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [15].Owayed AF, Campbell DM, Wang EE. Underlying causes of recurrent pneumonia in children. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine 2000;154:190–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Weir K, McMahon S, Barry L, Ware R, Masters IB, Chang AB. Oropharyngeal aspiration and pneumonia in children. Pediatric pulmonology 2007;42:1024–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hersh C, Wentland C, Sally S, de Stadler M, Hardy S, Fracchia MS, et al. Radiation exposure from videofluoroscopic swallow studies in children with a type 1 laryngeal cleft and pharyngeal dysphagia: A retrospective review. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology 2016;89:92–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bonilha HS, Humphries K, Blair J, Hill EG, McGrattan K, Carnes B, et al. Radiation exposure time during MBSS: influence of swallowing impairment severity, medical diagnosis, clinician experience, and standardized protocol use. Dysphagia 2013;28:77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Weir KA, McMahon SM, Long G, Bunch JA, Pandeya N, Coakley KS, et al. Radiation doses to children during modified barium swallow studies. Pediatric radiology 2007;37:283–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gasparin M, Schweiger C, Manica D, Maciel AC, Kuhl G, Levy DS, et al. Accuracy of clinical swallowing evaluation for diagnosis of dysphagia in children with laryngomalacia or glossoptosis. Pediatric pulmonology 2017;52:41–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Arvedson J, Rogers B, Buck G, Smart P, Msall M. Silent aspiration prominent in children with dysphagia. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology 1994;28:173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Velayutham P, Irace AL, Kawai K, Dodrill P, Perez J, Londahl M, et al. Silent aspiration: Who is at risk? The Laryngoscope 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [23].Rommel N, De Meyer AM, Feenstra L, Veereman-Wauters G. The complexity of feeding problems in 700 infants and young children presenting to a tertiary care institution. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 2003;37:75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tutor JD, Srinivasan S, Gosa MM, Spentzas T, Stokes DC. Pulmonary function in infants with swallowing dysfunction. PloS one 2015;10:e0123125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sheikh S, Allen E, Shell R, Hruschak J, Iram D, Castile R, et al. Chronic aspiration without gastroesophageal reflux as a cause of chronic respiratory symptoms in neurologically normal infants. Chest 2001;120:1190–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gurberg J, Birnbaum R, Daniel SJ. Laryngeal penetration on videofluoroscopic swallowing study is associated with increased pneumonia in children. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology 2015;79:1827–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Firth D Bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates. Biometrika 1993;80:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Coon ER, Srivastava R, Stoddard GJ, Reilly S, Maloney CG, Bratton SL. Infant Videofluoroscopic Swallow Study Testing, Swallowing Interventions, and Future Acute Respiratory Illness. Hosp Pediatr 2016;6:707–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bhattacharyya N The prevalence of pediatric voice and swallowing problems in the United States. The Laryngoscope 2015;125:746–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Adil E, Al Shemari H, Kacprowicz A, Perez J, Larson K, Hernandez K, et al. Evaluation and Management of Chronic Aspiration in Children With Normal Upper Airway Anatomy. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery 2015;141:1006–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].D’Agostino JA, Passarella M, Martin AE, Lorch SA. Use of Gastroesophageal Reflux Medications in Premature Infants After NICU Discharge. Pediatrics 2016;138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [32].Barron JJ, Tan H, Spalding J, Bakst AW, Singer J. Proton pump inhibitor utilization patterns in infants. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 2007;45:421–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].McSweeney ME, Kerr J, Amirault J, Mitchell PD, Larson K, Rosen R. Oral Feeding Reduces Hospitalizations Compared with Gastrostomy Feeding in Infants and Children Who Aspirate. The Journal of pediatrics 2016;170:79–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bae SO, Lee GP, Seo HG, Oh BM, Han TR. Clinical characteristics associated with aspiration or penetration in children with swallowing problem. Annals of rehabilitation medicine 2014;38:734–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Calvo I, Conway A, Henriques F, Walshe M. Diagnostic accuracy of the clinical feeding evaluation in detecting aspiration in children: a systematic review. Developmental medicine and child neurology 2016;58:541–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Frakking TT, Chang AB, O’Grady KF, David M, Walker-Smith K, Weir KA. The Use of Cervical Auscultation to Predict Oropharyngeal Aspiration in Children: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Dysphagia 2016;31:738–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wentland C, Hersh C, Sally S, Fracchia MS, Hardy S, Liu B, et al. Modified Best-Practice Algorithm to Reduce the Number of Postoperative Videofluoroscopic Swallow Studies in Patients With Type 1 Laryngeal Cleft Repair. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery 2016;142:851–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wolter NE, Hernandez K, Irace AL, Davidson K, Perez JA, Larson K, et al. A Systematic Process for Weaning Children With Aspiration From Thickened Fluids. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]