Abstract

Mounting evidence in the literature suggests that RNA–RNA binding protein aggregations can disturb neuronal homeostasis and lead to symptoms associated with normal aging as well as dementia. The specific ablation of cyclin A2 in adult neurons results in neuronal polyribosome aggregations and learning and memory deficits. Detailed histologic and ultrastructural assays of aged mice revealed that post-mitotic hippocampal pyramidal neurons maintain cyclin A2 expression and that proliferative cells in the dentate subgranular zone express cyclin A2. Cyclin A2 loss early during neural development inhibited hippocampal development through canonical/cell-cycle mechanisms, including prolonged cell cycle timing in embryonic hippocampal progenitor cells. However, in mature neurons, cyclin A2 colocalized with dendritic rRNA. Cyclin A2 ablation in adult hippocampus resulted in decreased synaptic density in the hippocampus as well as in accumulation of rRNA granules in dendrite shafts. We conclude that cyclin A2 functions in a noncanonical/non–cell cycle regulatory role to maintain adult pyramidal neuron ribostasis.

In the adult nervous system, several processes change with advanced age. For instance, rRNA transcription in hippocampal neurons is down-regulated in conditions associated with learning impairment, including alcohol exposure,1 Alzheimer disease,2 and advanced animal age.3 Studies in Caenorhabditis elegans have underlined the relationship between rRNA synthesis pathways and longevity,4 whereas others have hypothesized that RNA–protein granules contribute to aberrant proteostasis of neurodegenerative disorders.5 Ribonucleoprotein transport has been a particular focus of investigation in the ageing brain. Transcribed genes generate mRNA molecules, which then associate with many ribonucleoproteins to form the messenger ribonucleoprotein complex. Neurons have unique challenges regarding messenger ribonucleoprotein complex regulation not present in other cells, including the need to transport translationally inactive messenger ribonucleoprotein complexes to dendrites and axons. Indeed, transcriptomic analyses have shown that up to one-third of all messenger ribonucleoprotein complexes generated in a neuron are present in its axons and dendrites,6 where local protein synthesis occurs in response to activation of signal transduction cascades. Specific candidate molecules implicated in ribosomal homeostasis (ribostasis) of aged brains have been lacking. In this study, we provide evidence that cyclin A2 regulates rRNA in aged brains.

Cyclin A2 (gene name CCNA2), the main mammalian S-phase cyclin, is required for replication fork initiation and S-G2 progression of dividing cells. However, cyclin A2 has been implicated in other noncanonical cyclin pathways, including cytoskeletal protein regulation via RhoA kinase,7 detection of DNA double-strand breaks,8 and regulation of mRNA.9 Embryonic CCNA2 ablation results in cerebellar cortical dyslamination, dentate gyrus hypoplasia, and developmental delay in forebrain neurons.8, 10, 11 CCNA2 ablation in adult hippocampal neurons, achieved by expressing cre-recombinase under the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II alpha chain (CAMKIIα) promoter in a CCNA2fl/fl background, results in learning and memory deficits. These studies suggested that cyclin A2 may play different roles during development and hippocampal maintenance. In this report, we show that in mature hippocampal neurons, cyclin A2 colocalizes with rRNA in hippocampal pyramidal neurons and that cyclin A2 ablation results in decreased synaptic density in hippocampal neurons and accumulation of rRNA granules. These data point to a nonredundant role of cyclin A2 in hippocampal homeostasis through rRNA regulation in aged mice and provide a mechanism for learning and memory deficits identified in cyclin A2 ablated mice.

Materials and Methods

Animal Husbandry and Tissue Processing

All work involving animals was performed under the auspices of a protocol approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. CCNA2fl/fl and CamkIIacre transgenic mice were bred, as described previously, for embryonic ablation of CCNA2 expression.11 Briefly, adult pups were anesthetized with ketamine (30 mg/mL) and xylazine (2 mg/mL) and perfused transcardially with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were post-fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose, and snap frozen in OCT. Cryosections of OCT-embedded brains were obtained and stained with pertinent antibodies. Control mice are littermates of CCNA2fl/fl, CamkIIacre mice with preserved CCNA2.

Immunofluorescence

Animal brains were harvested as described above. Cryosections (12 μm thick) were obtained and mounted onto slides. Tissue sections were permeabilized for 20 minutes in 0.05 mol/L PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 at room temperature. Antigen retrieval was performed with 10 mmol/L citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 20 minutes. Blocking was performed by 2-hour incubation with a solution containing: 0.05 mol/L PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100 (v/v), 5% normal goat serum (v/v; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA; number 10000C), and 1% bovine serum albumin (w/v; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following antibodies: mouse monoclonal anti-rRNA 5.8s antibody (Y10B; 1:50; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; number ab171119), cyclin A antibody (C-19; 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX; sc-596), Ki-67 (8D5) mouse monoclonal antibody (1:800; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA; number 9449), bromodeoxyuridine (for detection of CldU; 1:600; Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO; number NB500-169), cyclin D1 mouse IgG2 monoclonal (2 μg/mL; Thermo Fisher Scientific; number MA5-12702), anti–glial fibrillary acidic protein chicken polyclonal (1:100; Abcam; number ab134436), TAU (5A6; 7 μg/mL; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA), microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2; 1:1000; EnCor Biotechnology, Gainesville, FL; number CPCA-MAP2), anti-GW182 antibody (4B6) P/GW body marker (1:100; Abcam; number ab70522), and neuronal nuclear antigen (NeuN) chicken polyclonal (1:400; Aves Lab Inc., Tigard, OR). Sections were rinsed with 0.05 mol/L PBS and 0.1% Triton X-100 (v/v), and stained with the appropriate secondary antibodies: goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific; number A-11029); goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 594 (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific; number A-11037); goat anti-mouse IgG antibody Alexa Fluor 647 (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific; number A21244); goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 594 (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific; number A11032); goat anti-chicken IgY (H+L) secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific; number A11039); goat anti-mouse IgG3 cross-adsorbed secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 594 (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific; number A21155); and goat anti-mouse IgG1 cross-adsorbed secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific; number A21121). DAPI (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific; number D1306) was used as a nuclear counterstain. Slides were mounted with ProLong Gold Antifade (Thermo Fisher Scientific; number P36934).

Imaging and Fluorescent Quantification of rRNA

Images were obtained using a Carl Zeiss Axio Imager Z.1 with LSM700 confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). We obtained fluorescent images as a single optical slice or Z-stacks. For rRNA analysis by confocal microscopy, cryosections were stained with anti-rRNA antibodies and counterstained with DAPI. Image capture was performed by Z-stack tiling the hippocampal formation using a 20× objective lens. rRNA was quantified in regions of interest delineated as stratum radiatum (SR) of CA1 and CA2 and stratum moleculare (SM) of the dentate gyrus. rRNA granules were identified and manually counted using the Fiji package for ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD; https://imagej.net/Fiji). rRNA granules per section were quantified and normalized to area to yield rRNA granule density. Two sections per animal were analyzed at equivalent anatomical locations and averaged to yield an rRNA granule density per animal (defined as n = 1). Arithmetic means from the groups (control and CamkIIacre, CCNA2fl/fl) were determined and plotted (n = 3 for control 8 month, n = 3 for CamkIIacre, CCNA2fl/fl 8 month, n = 2 for control 4 month, n = 2 for CamkIIacre, CCNA2fl/fl 4 month).

Golgi Impregnation, Neurolucida Tracing, and Morphometry

Golgi impregnation was performed as described previously,10 with a few modifications. After perfusion as stated above, whole brains were dissected under a stereomicroscope and prepared by Golgi method using the protocol of the manufacturer (FD Neurotechnologies, Columbia, MD); slides were prepared with a 100-μm cryosection thickness. Slide labels of each animal were randomized and analyzed in a blinded manner by an experienced observer (M.G.). Tracing was performed with Neurolucida version 11 (MBF Biosciences, Williston, VT) on Z-stack images obtained from StereoInvestigator version 11 (MBF Biosciences). Contours for tracing were drawn at ×10 magnification, and the Meander Scan function was used to generate a collage of Z-stack (1 image per micron Z-step) photomicrographs (at 13,600 × 13,600 pixels) that were then saved as .tiff images linked to a .dat file. The tracings were exported for illustration as a PDF file for graphic layout in Adobe Illustrator (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA). Neuronal tracings were performed with Neurolucida Explorer. Dendrite complexity index was calculated as defined by Pillai et al,12 and dendrite complexity was calculated by Sholl analysis.

Ultrastructure Analysis

Animals were perfusion fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brains were extracted and placed in fresh fixative (2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS, pH 7.2, for 2 days at 4°C). Tissue was then washed for 24 hours in PBS. Brains were embedded in 4% agarose and divided into sections (300 μm thick) on a vibratome. Sections were stored in PBS and delivered to the Campus Microscopy & Imaging Facility at The Ohio State University for transmission electron microscopy processing. All processing steps were performed at room temperature. Samples were post-fixed in 0.1 mol/L osmium tetroxide for 2 hours, followed by thorough rinsing in distilled water and en bloc staining with 2% ethanolic uranyl acetate. Samples underwent dehydration through a graded ethanol series (30% to 100%) and transitioned into acetone for resin infiltration. An epoxy resin, Eponate 12 (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA), was used for a graded infiltration series and embedding. Final embedding was done in a flat embedding mold and weighted down with a prepolymerized specimen holding capsule to ensure proper orientation and avoid warping of tissue. Tissue was placed in a 60°C oven and polymerized overnight. Blocks were trimmed, and semithin sections (500 nm thin) were cut on a glass knife and stained with 1% toluidine blue stain to identify slices containing the SR, SM, and dentate granule neurons. The region of interest was further trimmed on the basis of the thick sections, and sections (70 nm thin) were cut using a diamond knife (Diatome, Inc., Hatfield, PA) on a Leica EM UC6 ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Thin sections were collected on 200 mesh copper grids and post-stained with 1% uranyl acetate and Reynold's lead citrate. Transmission electron microscopy micrographs were taken on an FEI Tecnai G2 Biotwin transmission electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) operating at 80 kV, and micrographs were captured using an Advanced Microscopy Techniques camera (Woburn, MA). Three animals per group were evaluated in this manner. Images were analyzed by an experienced user (M.G.) in a blinded manner, and quantifications of synaptic density and polyribosomes were performed as described previously.13

Cell Culture

In vitro cultures of mouse hippocampal pyramidal neurons were performed as described previously.14 Briefly, hippocampal neurons were isolated from embryonic day 17 CD1 mice embryos. Pregnant females were anesthetized with ketamine (30 mg/kg) and xylazine (2 mg/kg), and embryonic day 17 embryos were extracted and their brains were dissected out in Hanks' balanced salt solution medium containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Meninges were removed from the medial aspect of cerebral hemispheres, and hippocampi were dissected out. Hippocampal neurons were dissociated with StemPro Accutase Cell Dissociation Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific; catalog number A1110501) by 15 minutes at 37°C. Cell dissociation reagent was then removed and replaced with Hanks' balanced salt solution medium containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The tissue was dissociated by repeatedly pipetting through a P1000 pipette tip, followed by a glass Pasteur pipette until a homogeneous solution was obtained. A total of 5 × 104 cells were seeded on each 12-mm round poly-l-lysine–coated coverslip containing wax dots and incubated 4 hours at 37°C in minimal essential medium supplemented with glucose (0.6% w/v) and containing 10% (v/v) horse serum. Coverslips with isolated hippocampal neurons were placed inverted into 60-mm dishes containing a glial feeder layer in minimal essential medium supplemented with glucose (0.6% w/v) and a 1:10 dilution of 100× N2 supplement. One third of the culture medium was replaced every 3 days for a total of 2 weeks.

Culture Immunofluorescence

After 2 weeks in culture, hippocampal neurons were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/sucrose in PBS for 30 minutes. After fixation, hippocampal neurons were permeabilized for 10 minutes in 0.05 mol/L PBS with Triton X-100 at room temperature. Blocking was performed as described above. Coverslips were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following antibodies: anti-rRNA 5.8s (Y10B; 1:100; Abcam; number ab171119) and cyclin A antibody (C-19; 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The following steps were performed as described above.

Poly(A) Detection with Fluorescent Poly-dT Probe

Coverslips containing neuron cells were fixed as described above. After fixation, cells were permeabilized by 10 minutes with cold methanol and stored at 4°C in 70% ethanol until the hybridization step. Ethanol was aspirated, and 1 mol/L Tris-HCL (pH 8.0) was added by 5 minutes and cells were incubated with hybridization buffer at 37°C overnight. The hybridization buffer comprised 0.005% bovine serum albumin, 1 mg/mL yeast RNA, 10% dextran sulfate, 25% formamide deionized 25% diluted in 2× saline sodium citrate buffer (SSC; 3 mol/L NaCl in 0.3 mol/L sodium citrate, pH 7.0; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; number S6639). 5-Cy3-OligdT-30 probe (Sigma Aldrich) was diluted into a final concentration of 2 ng/μL in the hybridization buffer. Samples were rinsed once with 4× SSC, and once with 2× SSC. Cyclin A antibody (C-19; 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and MAP2 (1:1000; EnCor Biotechnology; number CPCA-MAP2) were diluted in 2× SSC containing 0.1% Triton-X-100, and cells were incubated overnight at 4°C. After being rinsed with 2× SSC buffer, coverslips were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with the following secondary antibodies: goat anti-mouse IgG antibody Alexa Fluor 647 (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific; number A21244); goat anti-chicken IgY (H+L) secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific; number A11039), and DAPI (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific; number D1306). Coverslips were rinsed twice with 2× SSC buffer and were mounted into slides with ProLong Gold Antifade.

Results

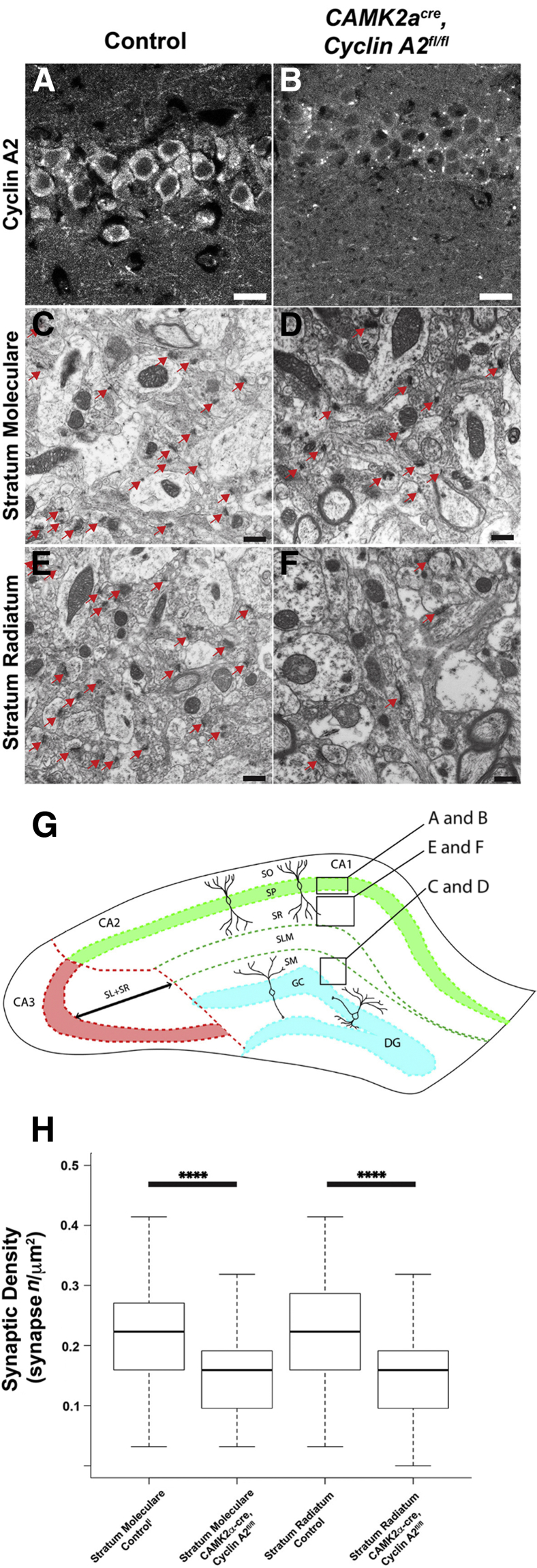

Cyclin A2 Ablation in Adult Mice Results in Decreased Synaptic Density in the Stratum Moleculare and Stratum Radiatum

CCNA2 ablation in adult brain cells results in learning and memory defects in mice aged to 8 months, as assayed by conditional fear response and Barnes Maze neurobehavioral assays.8 Therefore, the extent to which adult CCNA2 ablation changes hippocampal cytoarchitecture and ultrastructure was evaluated. A CAMKIIa-promoter–driven CRE mouse in which high-level CRE expression is restricted to the adult (postnatal day 21 to 90) was used.15 CCNA2fl/fl mice were crossed with CAMKIIacre mice to ablate the CCNA2 locus in CAMKIIa-expressing cells. To verify the success of ablating cyclin A2 in this system, histochemical evaluation was performed on 8-month–old control and CamkIIacre, CCNA2fl/fl animals (Figure 1, A and B). These stains showed a non-specific perinuclear dot-like morphology in both control and induced CCNA2 knockouts. However, a significant decrease in cytoplasmic and dendritic cyclin A2 in hippocampus was noted in the CCNA2 conditional knockout. In older adults, cyclin A2 seems to be expressed in hippocampal neurons, and CCNA2 can be successfully abrogated in the CamkIIacre, CCNA2fl/fl animals.

Figure 1.

Cyclin A2 loss in adult neurons results in decreased synaptic density in stratum moleculare (SM) and stratum radiatum (SR). A: Cyclin A2 expression in CA1 pyramidal neurons is lost in CamkIIacre, CCNA2fl/fl mice at 8 months. Genotypes are on top. A and B: Cyclin A2 immunostaining. Cyclin A2 shows cytoplasmic staining in CA1 pyramidal neurons, which is absent in the conditional cyclin A2 knockout. Perinuclear punctated staining present in B represents a non-specific reaction that is also present in A. C–F: Electron photomicrographs of control and mutant from the SM and SR layers of the hippocampus. Red arrows point to synapses. G: Illustration showing the anatomical hippocampal areas that are being analyzed with electron microscopy. H: Box-whisker plots of the synaptic density (per area) where the solid bar is the arithmetic median, the extent of the boxes is the interquartile range, and the whiskers are 1.5× the interquartile range. H: Results from P values derived from two-tailed homoscedastic t-test are plotted. All images and quantifications were obtained from 8-month–old mutant or control animals. ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. Scale bars: 10 μm (A and B); 500 nm (C–F). DG, dentate gyrus; GC, granule cell layer; SLM, stratum lacunosum-moleculare; SM, stratum moleculare; SO, stratum oriens; SP, stratum pyramidale; SR, stratum radiatum.

Previous studies knocking out cyclin E in the adult have described a memory defect due to decreased synapse number and decreased dendritic spine number and density in CA1 and CA2 hippocampal pyramidal cells.16 To determine whether cyclin A2 functions in the same manner, synaptic density in the SM and SR of CA1 to CA2 was determined using electron microscopy (Figure 1, C–H). The synaptic density in both the SM and SR is significantly reduced in the CCNA2 ablated animals. To test if the cytoarchitecture of hippocampal neurons was affected, Golgi impregnation studies were performed to analyze neuronal architecture. Golgi impregnated dentate granule neurons and CA1 pyramidal neurons were evaluated by Neurolucida to determine dendrite complexity index, mean spine density, and Sholl analyses (Figure 2). No statistical difference was observed between dendrite complexity index and neuronal complexity index measured by Sholl analysis in dentate granule neurons and CA1 pyramidal neurons with or without CCNA2 loss. CCNA2 ablation alters neither dendrite complexity of CA1 pyramidal neurons nor dentate granule neurons at 4 and 8 months. However, CCNA2 ablation in the adult hippocampus results in decreased SM and SR synaptic density.

Figure 2.

CamkIIacre, CCNA2fl/fl mice show no significant morphologic changes on Golgi impregnation relative to control mice. A–D: Examples of dentate granule neurons (DGNs) traced using Neurolucida obtained from Golgi impregnated slides. Genotype is indicated on top, and anatomical region and animal age are delineated on the left. A–G: Traced dentate granule neurons (A–D), dendrite complexity index (E), mean dendritic spine density (F), and complexity by Sholl analysis (G). No statistical difference is identified in neuronal complexity and dendritic spine density in dentate granule neurons between control and CamkIIacre, CCNA2fl/fl mice at 4 and 8 months. E–P: In whisker plots, the box of the whisker plot represents the interquartile range, the solid black bar represents the median, and the whiskers represent 1.5× the interquartile range.

Adult CCNA2 Ablation Results in Hippocampal rRNA Granule Accumulation

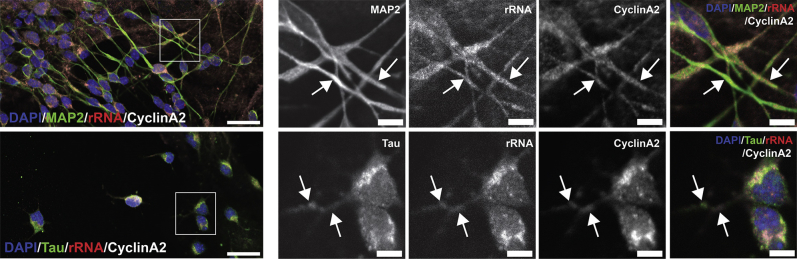

Cyclin A2 shows some functional redundancies with cyclin E in some cell types,17 and cyclin E localizes to post-synaptic densities of hippocampal neurons, where it modulates the activity of cyclin-dependent kinase 5.16 The localization of cyclin A2 in primary hippocampal neuron cell cultures was therefore evaluated (Figure 3). Cyclin A2 was present in the cytoplasm and neurites of primary hippocampal pyramidal neurons, with cyclin A2–positive varicosities located along the dendritic arborization (Figure 3). To ensure this was a specific cyclin A2 phenomenon, this pattern of localization was compared with that of cyclin D1, a G1 cyclin in which ablation results in similar cerebellar phenotypes to cyclin A2 loss18, 19 (Figure 4). Cyclin D1 staining did not appear to overlap with rRNA in neuronal processes (Figure 4). To confirm that cyclin A2 colocalized with ribosomes, mRNA poly(A) was detected by in situ hybridization with OligodT-labeled probes in neuronal cells (Figure 5). OligodT staining was highly enriched in the nuclear and perinuclear compartments of the neuron, corresponding to the nuclear and Golgi/endoplasmic reticulum pools of mRNA (Figure 5). Neuronal processes staining for cyclin A2 also contained diffuse OligodT fluorescence in situ hybridization signal, presumably corresponding to ribosomes being trafficked along processes (Figure 5). This finding supports our hypothesis that cyclin A2 is involved in ribosomal function. This subcellular distribution was further investigated to determine whether cyclin A2 appeared preferentially in axonal or dendritic processes by immunostaining with Tau and MAP2, respectively (Figure 6). Cyclin A2 staining was observed within MAP2- (Figure 6) and Tau-positive processes (Figure 6) showing presence of this protein along either axonal or dendritic compartments and indicating no preference between these compartments in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. These data collectively support a novel role for cyclin A2 in neuronal cells interacting with ribosomes as they are being trafficked along processes.

Figure 3.

Cyclin A2 colocalizes with rRNA and OligodT in hippocampal pyramidal neurons in vitro. Hippocampal pyramidal neuron cultures were generated and allowed to mature. These cells were then fixed and stained with anti–cyclin A2 (red) and anti-rRNA antibodies. A: A stitched tiled confocal image of a population of pyramidal neurons. The molecular markers are on the bottom left of each panel and color coded when appropriate. Small squares in A denote high-magnification images in B–D, E–G, and H–J. In these panels, each fluorescent channel is shown separately, followed by a merged channel. Yellow arrows indicate points where cyclin A2 and rRNA show colocalization, which tended to occur at locations of dendritic varicosities. Scale bars: 50 μm (A); 5 μm (B–J).

Figure 4.

Cyclin A2 colocalizes with rRNA and OligodT in hippocampal pyramidal neurons in vitro. Hippocampal pyramidal neuron cultures were generated and allowed to mature. A–G: These cells were then fixed and stained with anti–cyclin D1 (green) and anti-rRNA antibodies. The molecular markers are on the bottom left of each panel and color coded when appropriate. A: A stitched tiled confocal image of a population of pyramidal neurons. A–G: Small squares in A denote high-magnification images in B–D and E–G. In these panels, each fluorescent channel is shown separately, followed by a merged channel. Red arrows point to rRNA accumulation on neuronal processes; green arrows, cyclin A2 accumulation; yellow arrows, points where cyclin A2 and rRNA show colocalization, which tends to occur at locations of dendritic varicosities. These accumulations tend to occur at separate locations on the neuronal process. Scale bars: 20 μm (A); 5 μm (B–G).

Figure 5.

A: A confocal image of a pyramidal neuron in a mixed culture. The neuron is identified by its expression of MAP2 (green), the mRNA granules are identified by OligodT fluorescence in situ hybridization (red), and cyclin A2 is identified by staining in white. B–D: MAP2-positive processes maintain a light staining pattern for both OligodT and cyclin A2. E–G: OligodT is most highly enriched in the nucleus and perinuclear area. Scale bars: 20 μm (A); 10 μm (B–G).

Figure 6.

Cyclin A2 is present in both axons and dendrites of hippocampal neurons. Cultured hippocampal neurons from postnatal day 0 mice were matured in vitro and immunostained for cyclin A2 and MAP2 or Tau to evaluate the colocalization of cyclin A2 with dendritic processes or axonal processes, respectively. Cyclin A2 immunostaining colocalizes to both MAP2-positive processes (arrows, top row) and Tau-positive processes (arrows, bottom row). Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification to the right. Scale bars: 20 μm (left column); 5 μm (higher magnification).

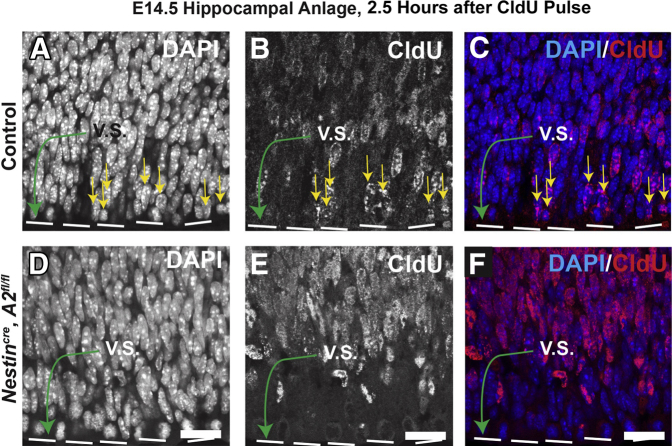

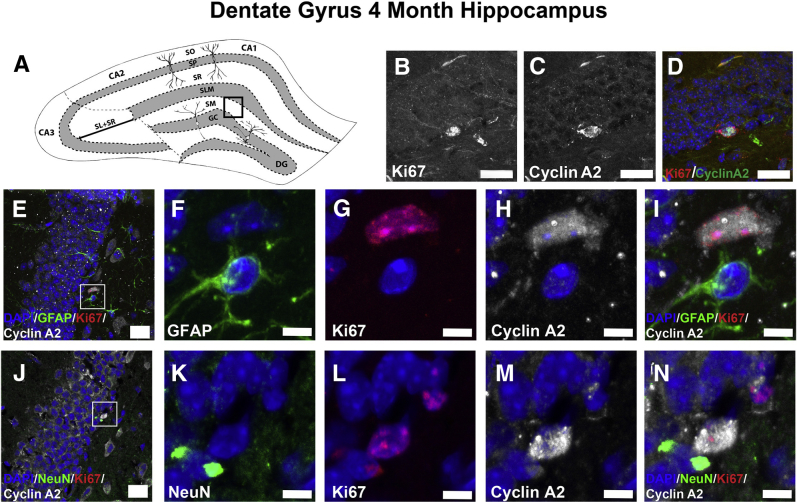

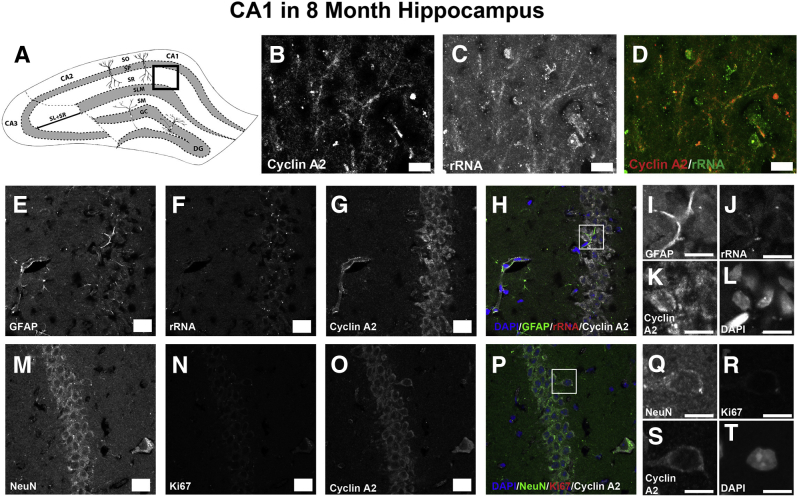

The subcellular staining pattern of cyclin A2 seen in neuronal cultures is different from that observed in postnatal mice in vivo (Figure 7). Cyclin A2 colocalizes with Ki-67 in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus (Figure 7, A–E) and is negative in neurons and astrocytes of the CA1 layer (Figure 7, F–J), consistent with the previously described cyclin A2 role in S-phase.20 Although astrocytes are actively proliferating in these regions, cyclin A2 staining was not observed in astrocytes of dentate granule (Figure 7, K–O) or CA1 (Figure 7, P–T) regions. Abrogation of cyclin A2 in embryonic neural progenitor cells through Nestin-induced cre expression reduces cell cycle time of embryonic neural progenitors. In control CldU pulsed animals that have a preserved CCNA2 locus, a 2.5-hour pulse of CldU permits cells to exit the S-phase and undergo interkinetic nuclear migration to the ventricular surface (Figure 8, A–C). In contrast, the interkinetic nuclear migration in Nestincre, CCNA2fl/fl animals was delayed (Figure 8, D–F). These data indicate that in proliferating cells of the developing hippocampus, cyclin A2 may function in a more canonical cell cycle role. We also found evidence that cyclin A2 is expressed in cycling cells of the hippocampal dentate gyrus of young adult mice (Figure 9, A–D). These cells did not appear to stain for neuronal or astrocytic markers (Figure 9, E–N), indicating that these cells were still in an undifferentiated state. In contrast, the SR of 8-month control animals contained numerous cyclin A2–positive dendrite-like processes, which also showed colocalization with rRNA (Figure 10, A–D). These cells were positive for neuronal markers and negative for astrocytic markers (Figure 10, E–T), supporting an alternative post-mitotic role for cyclin A2 in adult hippocampal neurons. Cyclin A2 likely plays canonical cell cycle–associated roles in proliferating cells during hippocampal development and may continue to perform these roles during hippocampal dentate gyrus maintenance in mice. Also, cyclin A2 does not solely localize to proliferative cells in 8-month–old mice, possibly supporting an additional role for this protein in adult tissues.

Figure 7.

Cyclin A2 regulates proliferation of hippocampal progenitor cells. Brains from postnatal day 0 (P0) mice immunostained for cyclin A2 and Ki-67 to evaluate the colocalization of cyclin A2 in proliferative cells in the P0 dentate gyrus (A–E and K–O) and CA1 layer (F–J and P–T). All cyclin A2 immunoreactive cells colocalize to proliferative cells in the P0 hippocampus and do not colocalize to neurons or astrocytes. Scale bars: 20 μm (A, F, K, and P); 5 μm (B–E, G–J, L–O, and Q–T). GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein.

Figure 8.

Cyclin A2 regulates proliferation of hippocampal progenitor cells. A–F: To test the effects of cyclin A2 ablation on proliferation in the embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5) hippocampal anlage, females impregnated with Nestincre, CCNA2fl/fl mice, and controls were pulsed with CldU for 2.5 hours. Green arrows denote the ventricular surface (V.S.); yellow arrows, progenitor cells that are CldU positive that have exited S-phase and have traversed to the ventricular surface via interkinetic nuclear migration. Scale bars = 10 μm (all images).

Figure 9.

Cyclin A2 colocalizes to 4-month–old subgranular dentate gyrus progenitors. A: Hippocampal illustration denoting the localization of subsequently analyzed sections [boxed area indicates stratum moleculare (SM)]. B–D: Brain of control 4-month–old animal stained with anti–cyclin A2 and anti–Ki-67 antibodies. Note the presence of proliferative cells in the subgranular zone. E–I: Control dentate gyrus (DG) stained with glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; green), Ki-67 (red), and cyclin A2 (white) shows no cyclin A2 colocalization to astrocytes in the DG. J–N: Control DG stained with NeuN (green), Ki-67 (red), and cyclin A2 (white) shows no cyclin A2 colocalization to neurons in the DG. Scale bars: 10 μm (B–D); 20 μm (E and J); 5 μm (F–I and K–N). DG, dentate gyrus; GC, granule cell layer; SLM, stratum lacunosum-moleculare; SM, stratum moleculare; SO, stratum oriens; SP, stratum pyramidale; SR, stratum radiatum.

Figure 10.

Cyclin A2 colocalizes with rRNA in neurons of the 8-month–old hippocampal neuropil. A: Illustration depicting hippocampal area analyzed [boxed area indicates stratum radiatum (SR) of CA1]. B–D: The SR stained with rRNA and cyclin A2. Neurites show colocalization of cyclin A2 with rRNA in 8-month–old SR. E–L: Control SR stained with glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; green), rRNA (red), and cyclin A2 (white) shows no cyclin A2 colocalization to astrocytes in the SR. Boxed area in H is shown at higher magnification in I–L. M–T: Control SR stained with NeuN (green), rRNA (red), and cyclin A2 (white) shows that cyclin A2 colocalizes to neurons in the 8-month–old SR. Boxed area in P is shown at higher magnification in Q–T. Scale bars: 10 μm (B–D, I–L, and Q–T); 20 μm (E–H and M–O). DG, dentate gyrus; GC, granule cell layer; SLM, stratum lacunosum-moleculare; SM, stratum moleculare; SO, stratum oriens; SP, stratum pyramidale; SR, stratum radiatum.

These morphology and localization patterns suggest that cyclin A2 may be involved in rRNA homeostasis. Because the nucleolus is involved in regulation of the RNA transcription machinery in response to cellular stress, the morphology of dentate gyrus granule neuron nucleoli was first evaluated. Nucleoli are separated into a fibrillary center and a dense fibrillar compartment.21 A significant difference was not observed in nucleolar structure in dentate gyrus granule neurons of CamkIIacre, CCNA2fl/fl animals (data not shown).

To identify any possible effects on rRNA trafficking in neuronal processes, the rRNA in the neuropil of the SM and SR was analyzed (Figure 11, A–J and L). In cyclin A2–ablated SR, clusters of polyribosomes were found in the SR dendrite shafts (Figure 11D), which resulted in an increase in SR mean polyribosome density in CCNA2 ablated animals (mean polyribosome density in SR is 0.059 polyribosomes/μm2 in control animals and 0.13 polyribosomes/μm2 in CCNA2 ablated animals). Large accumulation of rRNA staining was also observed in the conditional CCNA2 knockout brains by confocal immunofluorescence analysis for rRNA (Figure 11, K and M). On immunofluorescence staining, the morphology of the polyribosome accumulation found in the transmission electron microscopy manifested as clusters of rRNA-immunoreactive aggregates, consistent with rRNA granules described by Krichevsky and Kosik.22 The mean density of rRNA granules was measured and plotted (Figure 11, N and O). Although increased rRNA granules were not observed in both SR and SM, only the quantification in the SR showed statistical significance. It was tested whether the rRNA accumulation observed corresponded to aggregation of cytoplasmic mRNA granules referred to as processing bodies (P-bodies). P-bodies consist of mRNAs that are inhibited from being translated through repression and degradation involving mRNA binding protein GW182.23, 24, 25 Most of these ribosomal accumulations were positive for P-body marker GW182, indicating that these ribosomes were not functionally viable (Figure 12). Cyclin A2 depletion leads to ribosomal accumulation along processes of adult SR neurons, which coincide with markers for P-bodies.

Figure 11.

Cyclin A2 ablation in adult brains results in accumulation of rRNA in dendritic shafts in stratum radiatum (SR). A–D: Representative electron photomicrographs obtained from stratum moleculare (SM) and SR (designated to the left of each panel) in control or CamkIIacre, CCNA2fl/fl mice (denoted on the top). Significant accumulation of polyribosomes is noted by electron microscopy in dendritic shafts of 8-month–old mutants. Red arrows indicate the polyribosomes within a dendritic shaft. E: The polyribosome quantification is graphed. P values obtained from t-test are shown in the head-to-head comparisons. F and G: Representative low-power views of 4-month–old control or CamkIIacre, CCNA2fl/fl hippocampi, respectively. H–M: Representative low-power views of 8-month–old control or CamkIIacre, CCNA2fl/fl hippocampi, respectively (H and I). Boxed areas in H are seen at higher magnification in J and L. Boxed areas in I are seen at higher magnification in K and M. Note the presence of rRNA accumulation in both of these regions in the CamkIIacre, CCNA2fl/fl hippocampus (arrows). N and O: The quantification of rRNA immunostaining in the hippocampus. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. Scale bars: 500 nm (A–D); 50 μm (F–M).

Figure 12.

rRNA accumulation in dendritic shafts of the stratum radiatum (SR) and stratum moleculare (SM) coincide with P-bodies. Panels show 8-month CamkIIacre, CCNA2fl/fl hippocampus immunostained for P-body marker GW182 (green) and rRNA (red) demonstrated on the SM and SR. Colocalization of GW182 with rRNA is denoted with arrows. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification to the right. Scale bars: 20 μm (left column); 10 μm (higher magnification).

Discussion

Canonical and Noncanonical Roles of Cyclin A2 and Redundancy with Cyclin E

Cyclin A2 has been shown to play a crucial role in cell cycle progression, where it interacts with cyclin-dependent kinases 2 and 1 during S-phase and at the G2 → M transition, respectively20; the cyclin A2/cyclin-dependent kinase 1 complex, in turn, regulates cyclin B activity during the G2 → M transition.26 These canonical, cell cycle–dependent cyclin A2 functions have been well documented and reproduced by multiple groups. However, the list of noncanonical/non–cell cycle–related cyclin A2 functions has been ever expanding. Some of these novel functions involve regulation of translation and cell motility. Specifically, cyclin A2 has been found to stabilize the DNA repair gene MRE11 by directly binding to the mRNA and assisting in polysome loading.9 Similarly, cyclin A2 regulates cortical actin polymerization through its interaction with RhoA, leading to decreased cell motility.7 Persistence of cyclin A2 beyond S-phase raises the possibility that it may be assisting in the stabilization of other mRNAs that are subsequently trafficked along neural processes. Concurrently, cyclin A2 may be involved in mediating the structural integrity of the axon terminus through its interaction with small Rho GTPases. Indeed, actin remodeling at both the dendritic spine and axon terminal is crucial to formation and maintenance of functional synapses.27, 28 The findings that cyclin A2 depletion leads to polysome dysregulation as well as decreased number of synapses support the notion that cyclin A2 possesses one or more of these noncanonical functions in the adult cell.

Redundancy between E- and A-type cyclins was first suggested by reports that both cyclins were capable of S-phase promoting activity.29 In fibroblasts, cyclin A2 loss does not prevent cell proliferation due to compensation by cyclin E1, which then becomes expressed throughout the cell cycle.17 Thus, in some canonical cell cycle roles, cyclin E1 can substitute for cyclin A2 activity. Cyclin E1 has also been shown to play a role in hippocampal homeostasis.16 Specifically, cyclin E1 localizes to hippocampal pyramidal neurons and regulates hippocampal pyramidal neuron dendritic spine density. Although ablation of cyclin E1 and cyclin A2 results in mice with neurobehavioral deficits, the deficit types are slightly distinct. For instance, cyclin E1–deficient mice show defects in spatial learning and memory, as assayed by the Morris Water Maze, a test that induces elevated stress in rodents during testing because rodents are nonaquatic mammals.16, 30 Although mice showing cyclin A2 ablation also showed defects in spatial learning and memory, as assayed by Barnes Maze, these mice also showed defects in associative learning, as assayed by the Contextual Fear Test, as well as other neurobehavioral changes, including improved performance relative to controls in rotarod testing (balance) and hot plate testing (pain).8 Although both cyclin E1– and cyclin A2–null hippocampi show decreases in synaptic density, cyclin E1–null hippocampal neurons show a significant decrease in dendritic spine density, which was not found in cyclin A2–null hippocampal neurons. Therefore, cyclin E1 and cyclin A2 possess nonredundant functions in the adult hippocampus.

Ribostasis in Neurodegeneration and the Aging Brain

Ramaswami et al proposed the definition of ribostasis to be “the appropriate production and regulation of the cellular transcriptome, which has downstream effects on protein homeostasis.”5,pp.731 The notion that certain RNA–RNA binding protein aggregations disturb neuronal homeostasis has been well documented in the scientific literature. For instance, cytoplasmic aggregation of the RNA-binding protein TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) is a neuropathological hallmark of sporadic and familial forms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal lobar degeneration.31 Furthermore, hexanucleotide expansion of C9ORF72 leads to its RNA accumulation in certain forms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and CGG expansions in the fragile X gene lead to toxic RNA aggregates and result in fragile X tremor ataxia syndrome.32, 33 These entities underline the importance of elucidating the molecular pathways by which ribostasis occurs in the aged brain. In contrast to proteostasis, the molecular underpinnings that underlie the formation of RNA aggregates have been poorly characterized. Herein, we report that cyclin A2 loss induces the formation of P-body–enriched RNA aggregates, which then leads to synaptic loss in the hippocampus. The mechanism(s) by which cyclin A2 induces this loss is unknown. RNA granule formation may induce pathologies by alteration of the population of mRNAs available for translation, sequestration of regulatory RNAs, such as miRNAs or noncoding RNAs, or sequestration of regulatory factors. The colocalization of cyclin A2 with rRNA in dendrites of hippocampal neurons may suggest a role in RNA transport; however, other functions of cyclin A2 cannot be excluded. In summary, this study provides the first evidence of cyclin A2 involvement in ribostasis of adult neurons and demonstrates that alteration of ribostasis in the absence of other neurodegeneration-prone mutations can induce synaptic loss in the hippocampus.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fay Patsy Catacutan for maintaining the animal colonies and preparing experimental tissues, and the University Laboratory Animal Resources (ULAR) staff at The Ohio State University for performing animal husbandry.

Footnotes

Supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant R01HL123355 (C.M.C. and J.J.O.), NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant 8UL1TR000090-05 (J.J.O.), and the Ohio State University Department of Pathology Internal/Start-Up Funds (J.J.O.).

M.J.A. and M.G. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures: None declared.

Presented in part at the Experimental Biology 2018 Meeting, April 21 to 25, 2018, San Diego, CA.

Contributor Information

José J. Otero, Email: jose.otero@osumc.edu.

Catherine M. Czeisler, Email: catherine.czeisler@osumc.edu.

References

- 1.Garcia-Moreno L.M., Conejo N.M., Pardo H.G., Gomez M., Martin F.R., Alonso M.J., Arias J.L. Hippocampal AgNOR activity after chronic alcohol consumption and alcohol deprivation in rats. Physiol Behav. 2001;72:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00408-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pietrzak M., Rempala G., Nelson P.T., Zheng J.J., Hetman M. Epigenetic silencing of nucleolar rRNA genes in Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiryk A., Sowodniok K., Kreiner G., Rodriguez-Parkitna J., Sonmez A., Gorkiewicz T., Bierhoff H., Wawrzyniak M., Janusz A.K., Liss B., Konopka W., Schutz G., Kaczmarek L., Parlato R. Impaired rRNA synthesis triggers homeostatic responses in hippocampal neurons. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:207. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tiku V., Jain C., Raz Y., Nakamura S., Heestand B., Liu W., Spath M., Suchiman H.E.D., Muller R.U., Slagboom P.E., Partridge L., Antebi A. Small nucleoli are a cellular hallmark of longevity. Nat Commun. 2016;8:16083. doi: 10.1038/ncomms16083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramaswami M., Taylor J.P., Parker R. Altered ribostasis: RNA-protein granules in degenerative disorders. Cell. 2013;154:727–736. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cajigas I.J., Tushev G., Will T.J., tom Dieck S., Fuerst N., Schuman E.M. The local transcriptome in the synaptic neuropil revealed by deep sequencing and high-resolution imaging. Neuron. 2012;74:453–466. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arsic N., Bendris N., Peter M., Begon-Pescia C., Rebouissou C., Gadea G., Bouquier N., Bibeau F., Lemmers B., Blanchard J.M. A novel function for cyclin A2: control of cell invasion via RhoA signaling. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:147–162. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gygli P.E., Chang J.C., Gokozan H.N., Catacutan F.P., Schmidt T.A., Kaya B., Goksel M., Baig F.S., Chen S., Griveau A., Michowski W., Wong M., Palanichamy K., Sicinski P., Nelson R.J., Czeisler C., Otero J.J. Cyclin A2 promotes DNA repair in the brain during both development and aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8:1540–1570. doi: 10.18632/aging.100990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanakkanthara A., Jeganathan K.B., Limzerwala J.F., Baker D.J., Hamada M., Nam H.J., van Deursen W.H., Hamada N., Naylor R.M., Becker N.A., Davies B.A., van Ree J.H., Mer G., Shapiro V.S., Maher L.J., 3rd, Katzmann D.J., van Deursen J.M. Cyclin A2 is an RNA binding protein that controls Mre11 mRNA translation. Science. 2016;353:1549–1552. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang J., Leung M., Gokozan H.M., Gygli P.E., Catacutan F.P., Czeisler C., Otero J.J. Mitotic events in murine cerebellar granule progenitor cells that expand cerbellar surface area are critical for Normal cerebellar cortical lamination. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2015;74:261–272. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otero J.J., Kalaszczynska I., Michowski W., Wong M., Gygli P.E., Gokozan H.N., Griveau A., Odajima J., Czeisler C., Catacutan F.P., Murnen A., Schuller U., Sicinski P., Rowitch D. Cerebellar cortical lamination and foliation require cyclin A2. Dev Biol. 2014;385:328–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pillai A.G., de Jong D., Kanatsou S., Krugers H., Knapman A., Heinzmann J.M., Holsboer F., Landgraf R., Joels M., Touma C. Dendritic morphology of hippocampal and amygdalar neurons in adolescent mice is resilient to genetic differences in stress reactivity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hazai D., Szudoczki R., Ding J., Soderling S.H., Weinberg R.J., Sotonyi P., Racz B. Ultrastructural abnormalities in CA1 hippocampus caused by deletion of the actin regulator WAVE-1. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaech S., Banker G. Culturing hippocampal neurons. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2406–2415. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dragatsis I., Zeitlin S. CaMKIIalpha-Cre transgene expression and recombination patterns in the mouse brain. Genesis. 2000;26:133–135. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<133::aid-gene10>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odajima J., Wills Z.P., Ndassa Y.M., Terunuma M., Kretschmannova K., Deeb T.Z., Geng Y., Gawrzak S., Quadros I.M., Newman J., Das M., Jecrois M.E., Yu Q., Li N., Bienvenu F., Moss S.J., Greenberg M.E., Marto J.A., Sicinski P. Cyclin E constrains Cdk5 activity to regulate synaptic plasticity and memory formation. Dev Cell. 2011;21:655–668. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalaszczynska I., Geng Y., Iino T., Mizuno S., Choi Y., Kondratiuk I., Silver D.P., Wolgemuth D.J., Akashi K., Sicinski P. Cyclin A is redundant in fibroblasts but essential in hematopoietic and embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2009;138:352–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pogoriler J., Millen K., Utset M., Du W. Loss of cyclin D1 impairs cerebellar development and suppresses medulloblastoma formation. Development. 2006;133:3929–3937. doi: 10.1242/dev.02556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciemerych M.A., Kenney A.M., Sicinska E., Kalaszczynska I., Bronson R.T., Rowitch D.H., Gardner H., Sicinski P. Development of mice expressing a single D-type cyclin. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3277–3289. doi: 10.1101/gad.1023602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pagano M., Pepperkok R., Verde F., Ansorge W., Draetta G. Cyclin A is required at two points in the human cell cycle. EMBO J. 1992;11:961–971. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hetman M., Pietrzak M. Emerging roles of the neuronal nucleolus. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krichevsky A.M., Kosik K.S. Neuronal RNA granules: a link between RNA localization and stimulation-dependent translation. Neuron. 2001;32:683–696. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braun J.E., Huntzinger E., Fauser M., Izaurralde E. GW182 proteins directly recruit cytoplasmic deadenylase complexes to miRNA targets. Mol Cell. 2011;44:120–133. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chekulaeva M., Mathys H., Zipprich J.T., Attig J., Colic M., Parker R., Filipowicz W. miRNA repression involves GW182-mediated recruitment of CCR4-NOT through conserved W-containing motifs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1218–1226. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fabian M.R., Cieplak M.K., Frank F., Morita M., Green J., Srikumar T., Nagar B., Yamamoto T., Raught B., Duchaine T.F., Sonenberg N. miRNA-mediated deadenylation is orchestrated by GW182 through two conserved motifs that interact with CCR4-NOT. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1211–1217. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devault A., Fesquet D., Cavadore J.C., Garrigues A.M., Labbe J.C., Lorca T., Picard A., Philippe M., Doree M. Cyclin A potentiates maturation-promoting factor activation in the early Xenopus embryo via inhibition of the tyrosine kinase that phosphorylates cdc2. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:1109–1120. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.5.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tada T., Sheng M. Molecular mechanisms of dendritic spine morphogenesis. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsiao K., Harony-Nicolas H., Buxbaum J.D., Bozdagi-Gunal O., Benson D.L. Cyfip1 regulates presynaptic activity during development. J Neurosci. 2016;36:1564–1576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0511-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strausfeld U.P., Howell M., Descombes P., Chevalier S., Rempel R.E., Adamczewski J., Maller J.L., Hunt T., Blow J.J. Both cyclin A and cyclin E have S-phase promoting (SPF) activity in Xenopus egg extracts. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1555–1563. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.6.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whishaw I.Q., Tomie J. Of mice and mazes: similarities between mice and rats on dry land but not water mazes. Physiol Behav. 1996;60:1191–1197. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumann M., Sampathu D.M., Kwong L.K., Truax A.C., Micsenyi M.C., Chou T.T., Bruce J., Schuck T., Grossman M., Clark C.M., McCluskey L.F., Miller B.L., Masliah E., Mackenzie I.R., Feldman H., Feiden W., Kretzschmar H.A., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeJesus-Hernandez M., Mackenzie I.R., Boeve B.F., Boxer A.L., Baker M., Rutherford N.J., Nicholson A.M., Finch N.A., Flynn H., Adamson J., Kouri N., Wojtas A., Sengdy P., Hsiung G.Y., Karydas A., Seeley W.W., Josephs K.A., Coppola G., Geschwind D.H., Wszolek Z.K., Feldman H., Knopman D.S., Petersen R.C., Miller B.L., Dickson D.W., Boylan K.B., Graff-Radford N.R., Rademakers R. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron. 2011;72:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hagerman R.J., Leavitt B.R., Farzin F., Jacquemont S., Greco C.M., Brunberg J.A., Tassone F., Hessl D., Harris S.W., Zhang L., Jardini T., Gane L.W., Ferranti J., Ruiz L., Leehey M.A., Grigsby J., Hagerman P.J. Fragile-X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) in females with the FMR1 premutation. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1051–1056. doi: 10.1086/420700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]