SUMMARY

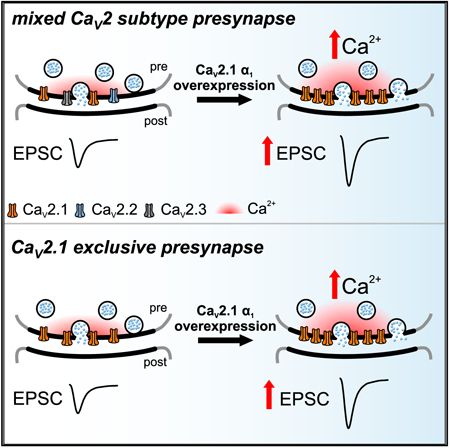

The abundance of presynaptic CaV2 voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (CaV2) at mammalian active zones (AZs) regulates the efficacy of synaptic transmission. It is proposed that presynaptic CaV2 levels are saturated in AZs due to a finite number of slots that set CaV2 subtype abundance and that CaV2.1 cannot compete for CaV2.2 slots. However, at most AZs, CaV2.1 levels are highest and CaV2.2 levels are developmentally reduced. To investigate CaV2.1 saturation states and preference in AZs, we overexpressed the CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 α1 subunits at the calyx of Held at immature and mature developmental stages. We found that AZs prefer CaV2.1 to CaV2.2. Remarkably, CaV2.1 α1 subunit overexpression drove increased CaV2.1 currents and channel numbers and increased synaptic strength at both developmental stages examined. Therefore, we propose that CaV2.1 levels in the AZ are not saturated and that synaptic strength can be modulated by increasing CaV2.1 levels to regulate neuronal circuit output.

Graphical Abstarct

In Brief

Lübbert et al. uncover that presynaptic active zones are not fully occupied by CaV2.1 during different states of neuronal circuit maturity. They propose that CaV2.1 levels in the presynaptic active zone can be increased to regulate neuronal circuit output.

INTRODUCTION

At central synapses, the CaV2 channel family, CaV2.1 (P/Q type), CaV2.2 (N type), and CaV2.3 (R type), mediate Ca2+ signals that trigger neurotransmitter release (Simms and Zamponi, 2014). Among the CaV2 family, CaV2.1 is dominant and most effective in triggering action potential (AP)-evoked release at the majority of central synapses (Eggermann et al., 2011; Iwasaki and Takahashi, 2001; Takahashi and Momiyama, 1993; Wheeler et al., 1994; Wu et al., 1998; Wu et al., 1999). A critical determinant of synaptic vesicle (SV) release probability (Pr) and release kinetics in response to APs is CaV2 subtype number (Ariel et al., 2013; Holderith et al., 2012; Sheng et al., 2012), which impacts synaptic strength (Schneggenburger and Rosenmund, 2015). In addition, CaV2 subtypes differentially control Ca2+ influx, which impacts synaptic transmission, plasticity, and strength (Catterall, 2011). Finally, presynaptic CaV2 subtype levels vary between synapses and can change with development and disease (Eggermann et al., 2011; Iwasaki and Takahashi, 2001; Momiyama, 2003; Scholz and Miller, 1995). Therefore, elucidating mechanisms regulating presynaptic CaV2 subtype levels is fundamental to understanding information encoding in the nervous system.

Since synaptic CaV2 levels at the AZ are distinct from the soma (Doughty et al., 1998; Miki et al., 2013), it is proposed that slots regulate CaV2 levels within the presynaptic AZ independent of the soma (Cao et al., 2004; Cao and Tsien, 2010). Although the molecular identity of slots is unknown, it is hypothesized that they differentially interact with the CaV2 α1 subunit to set relative CaV2 levels and that slot preference can vary depending on synapse type. It is thought some slots are CaV2.2 specific and that others prefer CaV2.1 but can accept CaV2.2, but that none are CaV2.1 exclusive and that these slots are always saturated (Cao et al., 2004; Cao and Tsien, 2010).

During neuronal circuit maturation, many presynaptic terminals either decrease the relative levels of CaV2.2 and CaV2.3 or shift to CaV2.1 exclusivity (Bucurenciu et al., 2010; Hefft and Jonas, 2005; Iwasaki et al., 2000; Iwasaki and Takahashi, 1998; Scholz and Miller, 1995). In addition, presynaptic Ca2+ currents are severely reduced with CaV2.1 α1 subunit deletion and only slightly compensated for by increased CaV2.2 currents; while there is no compensation by CaV2.3 currents (Inchauspe et al., 2004; Lübbert et al., 2017). This suggests that at CaV2.1-dominated presynaptic terminals in vivo, CaV2.1-exclusive slots exist, and CaV2.1 are preferred over CaV2.2. More importantly, if slots existed in a CaV2.1-saturated state, this would constrain how CaV2.1-exclusive presynaptic terminals could increase Ca2+ entry to modulate synaptic strength and SV release kinetics and implies that increases in Ca2+ entry could only be achieved through CaV2.1 channel modulation, and not by increasing CaV2.1 levels in the presynaptic AZ.

To investigate the role of the CaV2 α1 subunit in AZ preference and CaV2.1 saturation states at a CaV2.1 dominate presynaptic terminal, we used the calyx of Held, a giant axosomatic presynaptic terminal in the auditory brainstem which is similar to GABAergic cerebellar, thalamic, and hippocampal synapse and transitions from a mixed CaV2 subtype to CaV2.1 exclusivity during neuronal circuit maturation (Borst and Soria van Hoeve, 2012; Hefft and Jonas, 2005; Iwasaki et al., 2000). We used helper-dependent adenovirus (HdAd) viral vectors (Lübbert et al., 2017; Montesinos et al., 2016) and developed a surgery technique to overexpress CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 α1 subunits before (mixed subtype) and after neuronal circuit maturation (CaV2.1 exclusive) to analyze their impact on CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 currents, channel numbers, and AP-evoked release. Here we show that CaV2.1 α1 subunit overexpression leads to larger presynaptic Ca2+ currents due to increases in CaV2.1 currents and CaV2.1 channel number, which results in increased Pr at both developmental stages. In addition, we found that CaV2.1 channels, and not CaV2.2 channels, were preferred at both developmental stages. Therefore, we propose a modified “slot” model in which AZs are not fully occupied by CaV2.1 during different states of neuronal circuit maturity and that CaV2.1 can compete with other CaV2 subtypes. This implies that CaV2.1 levels in the AZ can be increased to regulate neuronal circuit output.

RESULTS

CaV2.1 α1 Subunit Overexpression Increases CaV2.1 Currents with a Corresponding Loss of CaV2.2 in the Immature Calyx

To test if slots in synapses within a native neuronal circuit prefer CaV2.1 or CaV2.2 and whether CaV2 slots exist in a saturated state, we overexpressed the mouse CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 α1 subunits at the P7 calyx of Held, a developmental time point at which the mouse calyx expresses a mixture of CaV2.1, CaV2.2, and CaV2.3 (~60% CaV2.1), similar to many other CNS synapses (Iwasaki et al., 2000; Iwasaki and Takahashi, 1998). We injected either HdAdCaV2.1 α1 or HdAd CaV2.2 α1 by utilizing the high-level overexpression cassette pUNISHER (Montesinos et al., 2011) to drive CaV2 α1 expression, independent of an EGFP or myristoylated EGFP (mEGFP) reporter, into the cochlear nucleus (CN) of P1 mice (Figures 1A-1C; Table S1). Viral particle to infectious unit ratios (VP:IU) of HdAd CaV2.1 α1 or HdAd CaV2.2 α1 were similar, therefore ensuring that CaV2.1 α1 and CaV2.2 α1 expression in vivo is equivalent. Using whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings at transduced or nontransduced P7 calyces, we measured the sensitivity of pharmacologically isolated Ca2+ currents (ICa) to the CaV2 subtype-specific blockers, ω-agatoxin IVA (Aga) (CaV2.1-selective) and ω-conotoxin GVIA (Cono) (CaV2.2-selective). All remaining Ca2+ currents (CaV2.3-mediated) were subsequently blocked with Cd2+ (nonspecific CaV2 channel blocker).

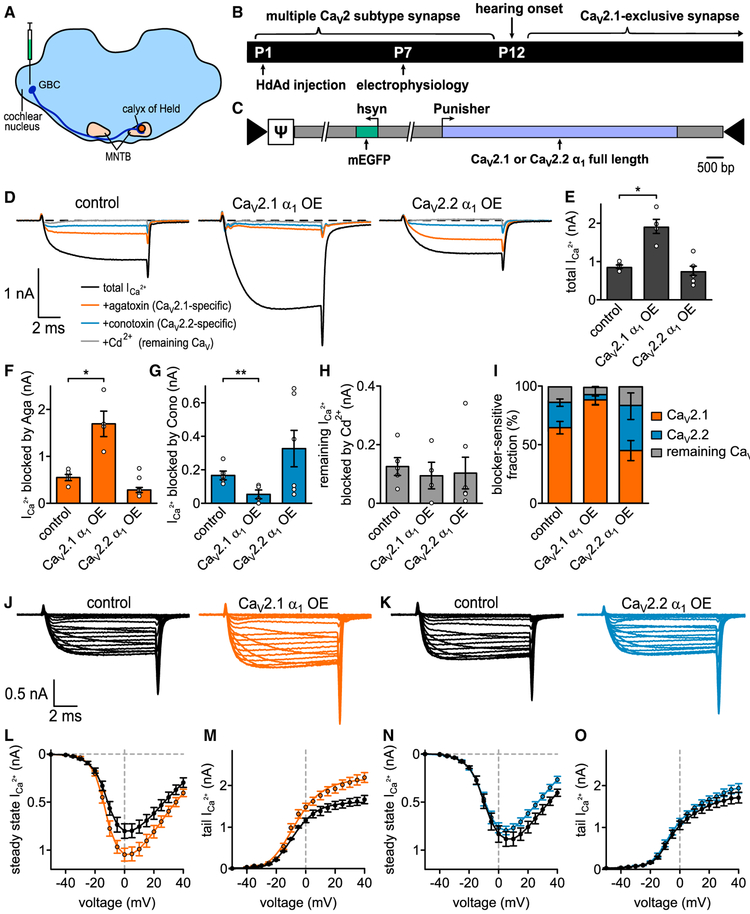

Figure 1. CaV2.1 α1 OE Results in Increased CaV2.1 Currents and Almost Complete Loss of CaV2.2 Currents at the P7 Calyx.

(A) Schematic of auditory brainstem. Globular bushy cells (GBC) which give rise to the calyx of Held are depicted for clarity.

(B) (Top) Developmental transition of calyx of Held from multiple CaV2 subtype synapse to CaV2 exclusive at onset of hearing (P12). (Bottom) Experimental timeline from virus injection into VCN at P1 to electrophysiological recordings at P7.

(C) Schematic of HdAd constructs expressing either CaV2.1 or CaV2.2 cDNAs (light blue) driven by the Punisher overexpression cassette and mEGFP marker (green) driven by a 470 bp human synapsin promoter; arrows indicate viral inverted terminal repeat sequences; J indicates the viral genome packaging signal sequence.

(D) Pharmacological isolation of CaV2 isoforms expressed in the presynaptic terminal at P7 in control (n = 5), CaV2.1 α1 OE (n = 4), or CaV2.2 α1 OE (n = 6). Average traces before application of blockers (black), after applying 200 nM ω-agatoxin IVA to specifically block CaV2.1 (Aga, brown), after 2 μM ω-conotoxin GVIA to block CaV2.2 (Cono, blue) and 50 μM Cd2+ to block the remaining Ca2+ currents (gray).

(E–H) Ca2+ current amplitudes before blocker application (CaV2.1 α1 OE versus control, p = 0.0328 Mood’s median test and post hoc Bonferroni test), Aga-sensitive Ca2+ current amplitudes (CaV2.1 α1 OE versus control, p = 0.0328), Cono-sensitive Ca2+ current amplitudes (CaV2.1 α1 OE versus control, p = 0.0054), and Cd2+-sensitive Ca2+ current amplitudes (n.s., Kruskal Wallis and post hoc Dunn’s test, n = 5/4/6 for control, CaV2.1 α1 OE, and CaV2.2 α1 OE, respectively).

(I) Relative Ca2+ current fractions sensitive to respective blockers.

(J and K) Average Ca2+ current traces to 10 ms step depolarizations from −80 mV holding to voltages between −50 and +40 mV for control (J and K, left, black) and CaV2.1 α1 OE (J, right, brown) or CaV2.2 α1 OE (K, right, blue).

(L–O) Current-voltage relationships of either steady-state Ca2+ currents (L and N) or tail Ca2+ currents (M and O, n = 10 for control, CaV2.1 α1 OE and CaV2.2 α1 OE). All data are shown as mean ± SEM. See also Table S1.

Measurements of the maximum steady-state ICa amplitudes in the absence of CaV2 blockers revealed a significant increase in the total ICa in the CaV2.1 α1 overexpression (OE) calyces compared to control (1,916 ± 211 pA versus 868 ± 51 pA, n = 4, n = 5, p = 0.0328, Mood’s median test and post hoc Bonferroni test). However, this increase was absent in the CaV2.2 OE calyces (758 ± 132 pA, n = 6, p > 0.99, Mood’s median test and post hoc Bonferroni test). Analysis of the CaV2 subtype contributions revealed the ICa increase in the CaV2.1 α1 OE calyces was due to an ~3-fold increase in the Aga-sensitive current (1,712 ± 272 pA versus 567 ± 66 pA, n = 4,n = 5,p = 0.0328, Mood’s median test and post hoc Bonferroni test). In addition, we found a 65% decrease in the Cono-sensitive current (59 ± 26 pA versus 172 ± 26 pA, n = 4, n = 5, p = 0.0054, Mood’s Median test and post hoc Bonferroni test) compared to control. Normalization of the Ca2+ currents revealed the contribution of CaV2.1 to ICa was strongly increased (91% ± 3.2% versus 65.2% ± 5.3%,) while the contribution of CaV2.2 (3% ± 1.5% versus 20.2% ± 3.1%) and CaV2.3 (4.7% ± 2.3% versus 14% ± 2.5%) were decreased (Figure 1I). In contrast, there were no changes in the toxin-sensitive fractions when overexpressing CaV2.2 α1.

Since CaV2.2 activates at more positive voltages than CaV2.1 at the calyx (Inchauspe et al., 2004), it was possible that we underestimated the ability of CaV2.2 to compete for CaV2.1 slots. To further characterize how CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 α1 OE influence ICa, we carried out current-voltage (IV) recordings (Figures 1J–1O). We switched to 1 mM external Ca2+ to minimize the potential influence of voltage clamp errors. Results of the IV relationships revealed that CaV2.1 α1 OE increased ICa compared to control while CaV2.2 α1 OE did not. The slow component of the cell capacitance (Cslow) in whole-cell configuration can be used as an estimate for the size of the presynaptic terminal. Since Cslow values were unchanged (Table S1), this indicates that ICa increases were not due to changes in calyx size. Fits of the presynaptic ICa revealed that CaV2.2 α1 OE did not change the voltage dependence of activation. In summary, these results demonstrate that CaV2.1 α1 OE leads to an increase in CaV2.1 currents which is paralleled by a reduction in CaV2.2 currents with no change in calyx size. Therefore, we conclude that presynaptic CaV2.1 current levels at the calyx of Held are not saturated and prefer CaV2.1 instead of CaV2.2.

The Increased Presynaptic CaV2.1 Currents Correspond to Increased CaV2.1 Numbers

To determine if the increased presynaptic CaV2.1 currents correlated to changes in CaV2.1 channel numbers, we carried out SDS-digested freeze fracture replica immunogold labeling (SDS-FFRL) at calyces transduced with either HdAd CaV2.1 α1 OE mEGFP or untransduced calyces (Figure 2; Table S2). Since CaV2 channels predominantly exist as clusters in the AZ (Baur et al., 2015; Budisantoso et al., 2012; Holderith et al., 2012; Indriati et al., 2013; Miki et al., 2017; Nakamura et al., 2015), we wanted to determine whether CaV2.1 numbers were increased specifically within clusters or randomly throughout the calyx. To do so, we used 30 nm radius circles extending from the center of each gold particle which accounts for CaV2 localization uncertainty (Althof et al., 2015) to measure the cluster area, number of gold particles per cluster, and gold particle density in clusters. We found that CaV2.1 α1 OE resulted in a distribution shift to larger cluster areas which was evidenced by a mean increase in the cluster area (0.0122 ± 0.0004 μm2 versus 0.0091 ± 0.0003 μm2, p = 0.0006, Mann-Whitney U test), the number of gold particles per cluster (7.3 ± 0.3 versus 4.8 ± 0.2, p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test), and the gold particle density per μm2 cluster area (563.3 ± 4.2 versus 506.3 ± 4.6, p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test) (Figures 2B–2D). In addition, we found a decrease of inter-particle distance per cluster (Table S2) and that there was a decrease in the number of single gold particles not found in a cluster compared to control (4.8% versus 10.9%, p < 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test) (Figure 2E), indicating the increased number of CaV2.1 channels lead to a higher probability of CaV2.1 channels being in clusters. Finally, these changes were not due to mEGFP expression, as previous reports have demonstrated that mEGFP expression alone does not lead to increases in Cav2.1 numbers (Dong et al., 2018).

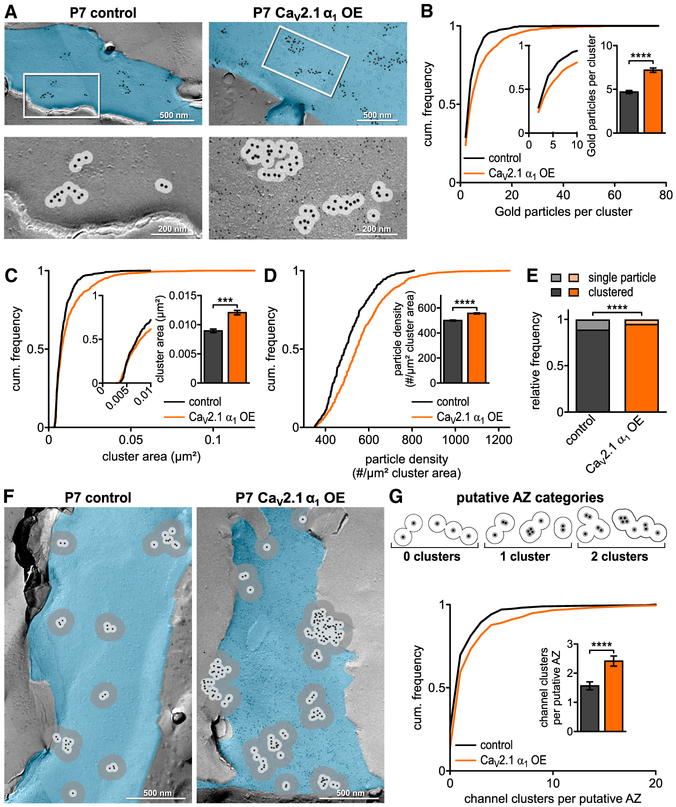

Figure 2. CaV2.1 α1 OE Leads to Increase in CaV2.1 Channels and Clusters at Putative AZ at P7.

(A) Representative SDS-digested freeze-fracture immunogold-labeled replicas of calyx P-faces (pseudocolored blue) of control and CaV2.1 α1 OE at P7. (Top) CaV2.1 distribution. Large gold particles (12 nm) label CaV2.1, small gold particles (6 nm) label mEGFP (CaV2.1 α1 OE only). (Bottom) High-magnification images of the boxed areas showing clustering of gold particles. A 30 nm circle indicates spatial uncertainty of CaV2.1 (light gray). Note that 12 nm gold particles have been enhanced for better visibility.

(B) Cumulative frequency distribution of gold particles per cluster; (insets) closeup of 0–10 particle clusters and corresponding bar graph (p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test, n = 428 for control and n = 957 for CaV2.1 α1 OE).

(C) Cumulative frequency distribution of cluster area; (inset) closeup of 0–0.01 μm2 and corresponding bar graph (p = 0.0006, Mann-Whitney U test, n = 428 for control and n = 957 for CaV2.1 α1 OE).

(D) Cumulative frequency distribution of gold particle density per μm2 cluster area; (inset) bar graph (p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test, n = 428 for control and n = 957 for CaV2.1 α1 OE).

(E) Relative frequency of single channels to channel clusters at P7 (p < 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test, n = 2,290 particles in 8 replicas for control and n = 7,314 particles in 7 replicas for CaV2.1 α1 OE).

(F) Representative SDS-digested freeze-fracture immunogold-labeled replicas of calyx P-faces (blue) of control and CaV2.1 α1 OE. Light gray circles indicate 30 nm radius, and dark gray circles indicate 100 nm radius around gold particles.

(G) (Top) Scheme of putative AZ categories. Cluster defined as overlap of at least two 30 nm circles and putative AZ as overlap of all 100 nm circles of clusters. (Bottom) Cumulative frequency distribution of channel cluster assembly within a putative AZ. (Inset) Number of clusters per putative AZ (p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test, n = 271 for control and n = 390 for CaV2.1 α1 OE). All data are shown as mean ± SEM. EM images are montage of multiple images assembled from the calyx P-face area containing CaV2.1. See also Table S2.

Individual presynaptic AZs contain multiple CaV2 clusters in a nonrandom organization (Holderith et al., 2012; Indriati et al., 2013; Nakamura et al., 2015). Therefore, we wanted to determine if CaV2.1 α1 OE increased the number of CaV2.1 channels and clusters within the AZ. At the calyx, a 100 nm radius extending from the center of the gold particle is equivalent to the average putative AZ area (Dong et al., 2018). Thus, we used a 100 nm radius from individual gold particles to measure the putative AZ area, the number of gold particles, particle density, and the 30 nm cluster distribution within the putative AZ (Figures 2F and 2G; Table S2). We found that CaV2.1 α1 OE increased the putative AZ area (0.153 ± 0.011 μm2 versus 0.105 ± 0.008 μm2, p = 0.0015, Mann-Whitney U test) and a corresponding increase gold particle density within the putative AZ (110.8 ± 2.6 versus 86.6 ± 2.2, p < 0.0001 Mann-Whitney U test). Subsequently, we counted the number of 30 nm clusters (>1 particle within 30 nm area) within the putative AZ. Our analysis revealed a shift towards putative AZs with increased cluster numbers (2.44 ± 0.17 versus 1.59 ± 0.14, p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test; Figure 2G). Taken together, our results demonstrate that the increase in presynaptic CaV2.1 currents upon CaV2.1 α1 OE correlates with increased CaV2.1 numbers, density per cluster, and cluster numbers.

Increased CaV2.1 Channels Numbers Do Not Change AZ Ultrastructure

Our SDS-FFRL data demonstrated that the putative AZ at the calyx increases in size with CaV2.1 α1 OE. However, the putative AZ area is based on CaV2.1 numbers and therefore an indirect measurement of AZ size. To directly measure the AZ length, we carried out ultrathin section TEM on the CaV2.1 α1 OE calyces and control (Figure 3; Table S2). The presynaptic AZ was defined as the membrane opposing the postsynaptic density (PSD) (Clarke et al., 2012). We found no increase in AZ length compared to control (Figures 3B and 3C). Since CaV2.1 clusters are suggested to correlate to SV docking sites (Miki et al., 2017), we measured the number of docked SV, defined as those within 5 nm of the plasma membrane (Taschenberger et al., 2002). Analysis of SV distribution revealed no change in docked SV number or SV distribution (Figures 3D and 3E). Our data demonstrate that AZ length and SV docking do not change with an increase in CaV2.1 channel numbers at the AZ. Therefore, we conclude that the AZ area does not increase to accommodate more CaV2.1 channels.

Figure 3. CaV2.1 α1 OE Does Not Affect AZ Ultrastructure or Quantal Size at P7.

(A–C) Representative EM images depicting AZs (yellow line) and docked SV (blue circles) of control (left) or CaV2.1 α1 OE (right) calyces. Transduced terminals are identified by antibody-coupled gold nanoparticles directed against EGFP (black dots in right image). (B and C) AZ length (B, n.s., Mann-Whitney U test, n = 120 for control and n = 118 for CaV2.1 α1 OE), cumulative frequency of AZ length (C).

(D) Number of docked vesicles per AZ (n.s., Mann-Whitney U test).

(E) SV distribution up to 200 nm distance from AZ in 5 nm bins.

(F) Representative traces of mEPSC recordings.

(G) Averaged mEPSCs for representative cell in (F).

(H) Average mEPSC amplitude (left, p = 0.56, two-tailed t test, n = 15) and mEPSC rate (right, p = 0.04, two-tailed t test). All data are shown as mean ± SEM. See also Table S2.

Increase in Presynaptic Cav2.1 Numbers Do Not Impact Quantal Amplitude

Although our ultrastructural data indicated there were no changes in AZ ultrastructure, it was possible that there were changes in SV volume that would not be apparent in the ultrathin section EM. Therefore, we recorded spontaneous AMPA-mediated miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSC) in medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) principal cells innervated by transduced or non-transduced calyces (Figures 3F–3H). We found no change in the mEPSC amplitudes between the CaV2.1 α1 OE and control calyces (37.2 ± 1.6 pA versus 35.7 ±1.9 pA, p = 0.56, two-tailed t test, n = 15), while there was an ~2-fold increase in the mEPSC frequency (0.56 ± 0.1 Hz versus 0.92 ± 0.1 Hz, p = 0.04, two-tailed t test, n = 15). Since quantal amplitude was not increased, we conclude that CaV2.1 α1 OE does not lead to an increase in SV volume.

Increased Presynaptic CaV2.1 Numbers Result in Increased Pr

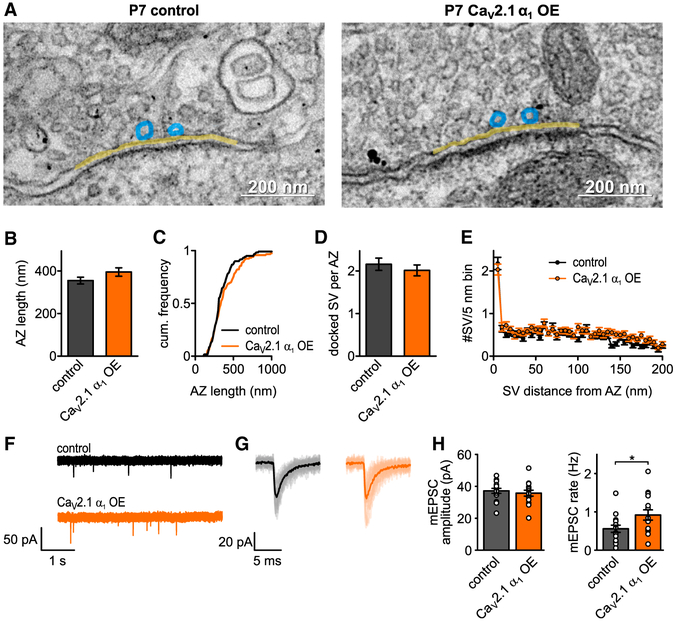

The strength of neurotransmitter release in response to APs is positively correlated to CaV2 numbers within the AZ (Holderith et al., 2012; Sheng et al., 2012), and AP-evoked release is highly dependent on the positioning of SVs relative to VGCCs (Neher, 2010). Since our EM data suggested that CaV2.1 numbers were increased within the AZ, this would significantly increase synaptic strength. However, if CaV2.1 channels were inserted outside the AZ, this would lead to no change in synaptic strength. To determine if the observed CaV2.1 channel increase impacts AP-evoked release, we carried out afferent fiber stimulation of the calyx axons and recorded the AMPAR-mediated EPSCs from the MNTB principal cells innervated by transduced or non-transduced calyces (Figure 4; Table S3). We measured AP-evoked synaptic transmission using a stimulation frequency of 0.05 Hz (in 1.2 mM [Ca2+]ext, Figures 4A–4C). Our analysis revealed a dramatic increase in AP-evoked EPSC of the CaV2.1 α1 OE versus control (3.1 ± 0.37 nA versus 1.47 ± 0.21 nA, p = 0.0006, Mann-Whitney, n = 20), while normalized EPSC waveforms and analysis of rise time and half-width indicated no change in EPSC kinetics (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Increased CaV2.1 Levels at AZ Increase SV Release Probability at P7.

(A) Average basal EPSC.

(B) EPSC peak amplitudes (p = 0.0006, Mann-Whitney U test, n = 20 for control and CaV2.1 α1 OE).

(C) Basal EPSC normalized to peak.

(D) Average traces of 50 Hz EPSC trains for control (left, n = 17) and CaV2.1 α1 OE (right, n = 20).

(E) 50 Hz train EPSC absolute peak amplitudes.

(F) 50 Hz train EPSC peak amplitudes normalized to first EPSC.

(G) Cumulative EPSC amplitudes.

(H) 50 Hz paired-pulse ratio (PPR, n.s., t test).

(I) RRP quantified with corrected SMN and NpRf methods (n.s., Mann-Whitney U test, n = 17 for control and n = 20 for CaV2.1 α1 OE).

(J) Release probability Pr quantified with corrected SMN and NpRf methods (p = 0.033 and p = 0.045, respectively, Mann-Whitney U test). All data are shown as mean ± SEM. See also Table S3.

Although the RRP has been correlated to the morphologically docked SVs (Schikorski and Stevens, 2001), recent data suggest otherwise (Sakamoto et al., 2018). Therefore, despite no change in docked SV number (Figure 3), the increased AP-evoked release could be due to either an increase in the readily releasable pool (RRP) size, an increase in the initial Pr, or both. To measure the RRP size, we carried out 50 Hz stimulation and used an SMN plot with correction for incomplete pool depletion (Neher, 2015) or fitting with a pool depletion model (NpRf model) (Thanawala and Regehr, 2016). Both analysis methods indicated that increased CaV2.1 numbers did not lead to an increase in RRP size. Calculation of initial Pr by dividing the first EPSC by the RRP size demonstrated that CaV2.1 α1 OE calyces had a significant increase in initial Pr compared to control (SMN, 0.34 ± 0.04 versus 0.2 ± 0.03, p = 0.033, Mann-Whitney U test; NpRf, 0.31 ± 0.05 versus 0.19 ± 0.03, p = 0.045, Mann-Whitney U test, n = 20, n = 17). The increase in Pr was further confirmed as normalization of the EPSC in the trains to the first EPSC demonstrated an increased rate of depression in the CaV2.1 α1 OE calyces compared to control. These results demonstrate that the higher CaV2.1 channel numbers by CaV2.1 α1 OE resulted in increased synaptic strength that is due to increases in Pr. Thus, we conclude that additional CaV2.1 channels resulting from CaV2.1 α1 OE are located within the AZs and that CaV2.1 channel levels are not saturated in the AZ.

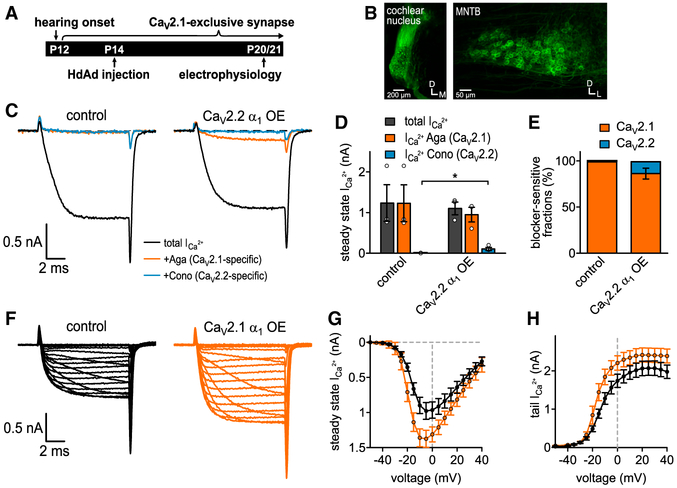

CaV2.1 α1 Overexpression Increases CaV2.1 Current Levels in the Mature Calyx of Held

Around the onset of hearing in mice at ~P12, the calyx of Held becomes a CaV2.1-exclusive terminal (Doughty et al., 1998; Iwasaki and Takahashi, 1998), similar to many cerebellar, thalamic, and other auditory brainstem synapses (Iwasaki et al., 2000). By ~P14, the calyx has undergone AZ ultrastructure refinement (Taschenberger et al., 2002) and supports adult-like auditory processing (Sonntag et al., 2009, 2011). Furthermore, by P18 the calyx of Held/MNTB synaptic responses to sound is indistinguishable from that in adult animals (Sonntag et al., 2009).Therefore, it was imperative to determine if our findings were specific to an early developmental stage or also applied to synapses in a mature neuronal circuit. Therefore, we developed a stereotactic surgery to target the CN in P14 mice (Figures 5A and 5B; Table S4) and subsequently measured how CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 α1 OE impacted CaV2.1 levels, organization, AZ ultrastructure, and synaptic transmission at the adult-like P20/P21 calyx.

Figure 5. CaV2.2 α1 OE Results in Slight Loss of CaV2.1 Currents, while CaV2.1 α1 OE Results in an Increase in CaV2.1 Currents at P20/21 Calyx.

(A) Experimental timeline from virus injection into CN at P14 to electrophysiological recordings at P20/21.

(B) Confocal images of brainstem slices injected with CaV2.1 α1 OE construct. (Left) CN injection site. (Right) Contralateral MNTB with mEGFP-expressing calyx of Held terminals.

(C) Pharmacological isolation of CaV2 isoforms expressed in the presynaptic terminal at P21 in control (n = 3) and CaV2.2 α1 OE (n = 3). Average current traces before application of blockers (black), after applying 200 nM ω-agatoxin IVA to specifically block CaV2.1 (Aga, brown) and after applying 2 μM ω-conotoxin GVIA to specifically block CaV2.2 (Cono, blue).

(D) Ca2+ current amplitudes before blocker application (black, n.s., two-tailed t test), Aga-sensitive Ca2+ current amplitudes (brown, n.s., one-tailed t test), and Cono-sensitive Ca2+ current amplitudes (blue, 0.016, one-tailed t test).

(E) Relative Ca2+ current fractions sensitive to blockers.

(F) Average Ca2+-current traces to 10 ms step depolarizations from −80 mV holding to voltages between −50 and +40 mV for control (left, n = 9) and CaV2.1 α1 OE (right, n = 10).

(G and H) Current-voltage relationships of either peak Ca2+ currents (G) or tail Ca2+ currents (H). All data are shown as mean ± SEM. See also Table S4.

To test if CaV2.2 could compete for CaV2.1 slots in a CaV2.1-exclusive synapse, we injected CaV2.2 α1 OE virus into the P14 CN and then measured ICa sensitivity to Aga and Cono at either untransduced or transduced P20/P21 calyces (Figures 5C-5E). Similar to the results at P7, CaV2.2 α1 OE did not increase the total ICa. Fractional current analysis revealed that CaV2.2 α1 OE led to small CaV2.2 currents (Figure 5D) amounting to ~10% of the overall ICa amplitude not found in controls (125 ± 37 pA versus 3 ± 3 pA, p = 0.016, n = 3, t test). To determine if CaV2.1-mediated increases were dependent on the developmental stage, we injected CaV2.1 α1 OE virus and recorded ICa. Our results demonstrated that CaV2.1 currents were increased compared to control (Figures 5F–5H) (Table S4), while normalization and fits revealed a change in ICa kinetics. In addition, we found no increase in Cslow, indicating that the increase in ICa is not due to a parallel increase in calyx size. Based on these results, we conclude that CaV2.1 preference and CaV2.1 increases are not restricted to an early developmental stage.

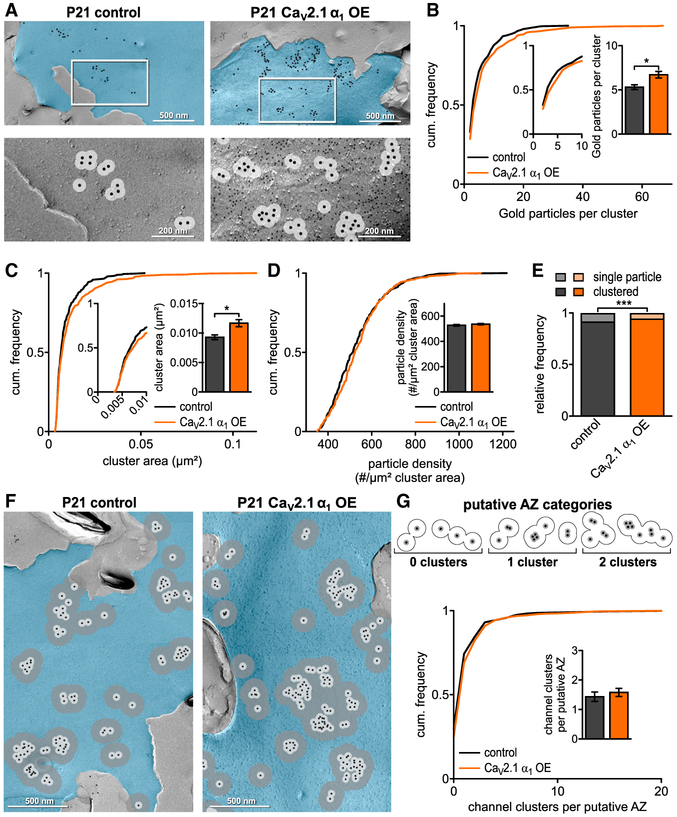

The Increased CaV2.1 Currents Correspond to Increased CaV2.1 Numbers in the Mature Calyx

Since the calyx undergoes morphological changes at hearing onset, it was important to know how CaV2.1 numbers and their organization were impacted upon CaV2.1 OE. Therefore, we applied an identical approach as performed at P7 to conduct SDS-FFRL at either transduced or untransduced calyces at P21 (Figure 6; Table S5). Using a 30 nm radius to measure CaV2.1 clustering, we measured the cluster area, number of gold particles per cluster, and cluster particle density. We found that CaV2.1 α1 OE resulted in a shift in the distribution to larger cluster areas (0.0118 ± 0.0006 μm2 versus 0.0094 ± 0.0004 μm2, p = 0.0315, Mann-Whitney U test) and a parallel increase in the number of gold particles per cluster (6.8 ± 0.4 versus 5.4 ± 0.3, p = 0.0139, Mann-Whitney U test). Analysis of the gold particle density per cluster and inter-particle distance in CaV2.1 α1 OE versus control showed no difference, indicating that cluster areas grew to accommodate increased CaV2.1 channel numbers (Figure 6D; Table S5). Finally, we found no change in the cluster density on the P-face.

Figure 6. CaV2.1 α1 OE Increases CaV2.1 Channels and Cluster Area at the Putative AZ at P21 Calyx.

(A) Representative SDS-digested freeze-fracture immunogold labeled replicas of calyx P-faces (pseudocolored blue) of control and CaV2.1 α1 OE at P21. (Top) CaV2.1 distribution. Large gold particles (12 nm) label CaV2.1, small gold particles (6 nm) label mEGFP (CaV2.1 α1 OE only), and 30 nm circle indicates spatial uncertainty of CaV2.1 (light gray). (Bottom) High-magnification images of the boxed areas showing clustering of gold particles. Note that 12 nm gold particles have been enhanced for better visibility.

(B) Cumulative frequency distribution of gold particles per cluster; (insets) closeup of 0–10 particle clusters and corresponding bar graph (p = 0.0139, Mann-Whitney U test, n = 334 for control and n = 456 for CaV2.1 α1 OE).

(C) Cumulative frequency distribution of cluster area; (inset) closeup of 0–0.01 μm2 and corresponding bar graph (p = 0.0315, Mann-Whitney U test).

(D) Cumulative frequency distribution of gold particle density per μm2 cluster area; (inset) bar graph (p = 0.1080, Mann-Whitney U test).

(E) Relative frequency of single channels to channel clusters (p = 0.0003, Fisher’s exact test, n = 1,982 particles in 13 replicas for control and n = 3,307 particles in 10 replicas for CaV2.1 α1 OE).

(F) Representative SDS-digested freeze-fracture immunogold labeled replicas of calyx P-faces (blue) of control and CaV2.1 α1 OE at P21. Large gold particles (12 nm) label CaV2.1, small gold particles (6 nm) label mEGFP (control and CaV2.1 α1 OE only), 30 nm circle (light gray), and 100 nm circle (dark gray).

(G) (Top) Diagram of putative AZ categories. Cluster defined as overlap of at least two 30 nm circles and putative AZ as overlap of all 100 nm circles of clusters. (Bottom) Cumulative frequency distribution of channel cluster assembly within a putative AZ. (Inset) Number of clusters per putative AZ (p = 0.0663, Mann-Whitney U test, n = 230 for control and n = 285 for CaV2.1 α1 OE). All data are shown as mean ± SEM. EM images are a montage of multiple images assembled from the calyx P face area containing CaV2.1. See also Table S5.

Subsequently, we measured putative AZ area and the number of gold particles, particle density, and cluster distribution within the putative AZ (Figures 6F and 6G). Analysis of the putative AZ area in the CaV2.1 α1 OE condition revealed a shift in the distribution to putative AZs with larger size (0.116 ± 0.008 μm2 versus 0.102 ± 0.011 μm2, p = 0.0075 Mann-Whitney U test). We found an increase in gold particle density per putative AZ, indicating that putative AZs were larger and contained more gold particles (105.9 ± 3.3 versus 88.8 ± 3.2, p = 0.001 Mann-Whitney U test) (Table S5). Counts of the number of 30 nm clusters within the putative AZ revealed no change in cluster numbers within the putative AZs (Figure 6G). Furthermore, there was no change in relative frequency in the number of single particles within the putative AZ with CaV2.1 OE versus control. Taken together, our results revealed that increases in CaV2.1 current were correlated with increases in the CaV2.1 numbers and density per cluster, but not cluster numbers within the putative AZ. Therefore, we conclude that AZs are not saturated for CaV2.1 channels in the mature presynaptic terminal.

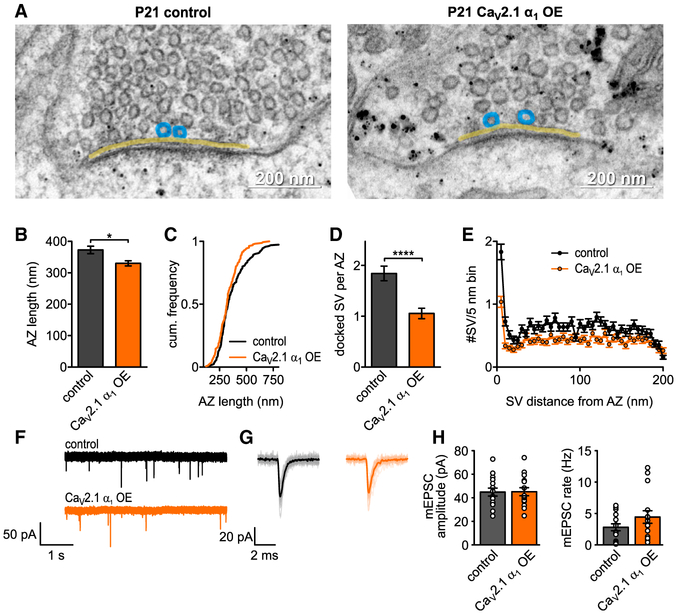

CaV2.1 α1 OE Leads to Smaller AZs and a Reduction in SV Docking at the P21 Calyx

To determine if AZs increased in size to accommodate more CaV2.1 channels, we performed ultrathin section TEM at the P21 CaV2.1 α1 OE calyces and control (Figure 7; Table S5). Analysis of the AZ length revealed that CaV2.1 α1 OE calyces (Figure 7B) had slightly smaller AZs compared to control (329.9 ± 8.2 nm versus 376.7 ± 12.2 nm, p = 0.0339, Mann-Whitney U test). In addition, we found a reduced number of docked SVs (1.0 ± 0.09 versus 1.8 ± 0.12, p < 0.0001 Mann-Whitney U test) (Figures 7D and 7E). For this reason, we conclude that the AZ can accept more CaV2.1 channels without increasing in size and that CaV2.1 levels in the AZ are not saturated in the mature calyx.

Figure 7. CaV2.1 α1 OE Affects Presynaptic Ultrastructure without Affecting Quantal Size at P21.

(A) Representative EM images depicting AZs (yellow line) and docked SV (blue circles) of control (left) or CaV2.1 α1 OE (right) calyces. Transduced terminals identified by antibody-coupled gold nanoparticles directed against EGFP (black dots). (B and C) AZ length (B, p = 0.0339, Mann-Whitney U test, n = 160 for control and CaV2.1 α1 OE), cumulative frequency of AZ length (C).

(D) Number of docked vesicles per AZ (p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test).

(E) SV distribution up to 200 nm distance from AZ in 5 nm bins.

(F) Representative traces of mEPSC recordings.

(G) Averaged mEPSC recordings for representative cell in (F).

(H) Average mEPSC amplitude (left, p = 0.95, two-tailed t test, n = 15) and mEPSC rate (right, p = 0.35, Mann-Whitney U test). All data are shown as mean ± SEM. See also Table S5.

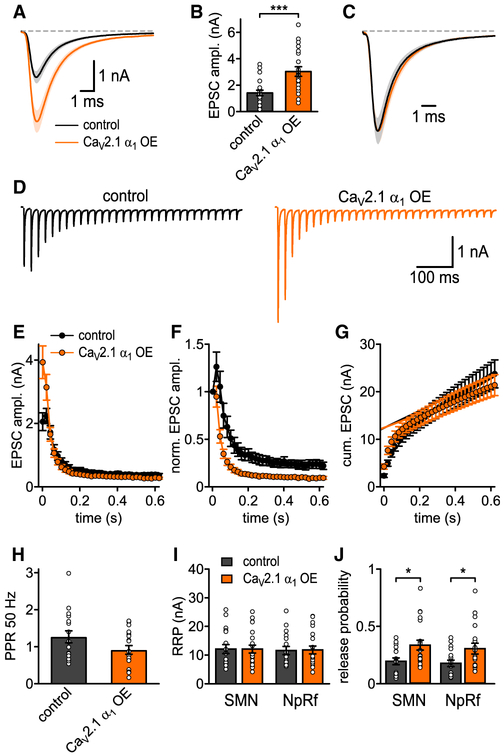

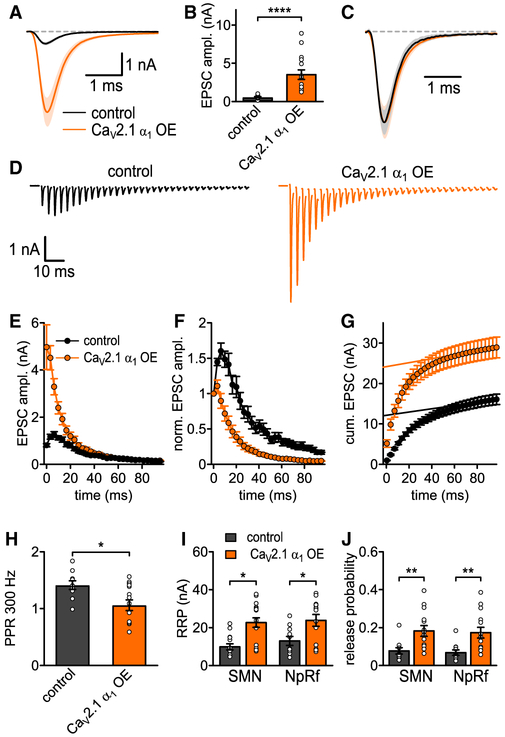

Increased CaV2.1 Numbers Result in Increased Pr in the Mature calyx

The mature calyx of Held utilizes nanodomain release modality to support the initial stages of auditory processing in adult animals (Fedchyshyn and Wang, 2005). Since single CaV2.1 channels can trigger SV fusion in response to APs in nanodomain release modality (Stanley, 2016), it was important to determine how CaV2.1 channel increases in the AZ impact synaptic strength at the P20/21 calyx. First, to determine if there were changes in quantal amplitudes (Figure 7), we measured spontaneous release at the P20/21 calyces. Analysis revealed no change in mEPSC frequency or amplitudes (Figures 7F–7H; Table S5). Subsequently, we carried out afferent fiber stimulation in 1.2 mM [Ca2+]ext to mimic in vivo Pr (Lorteije et al., 2009) and measured AP-evoked release (Figure 8; Table S6). In response to 0.05 Hz stimulation, we found an ~6-fold increase in the AP-evoked EPSC amplitude of CaV2.1 α1 OE calyces compared to control (3.64 ± 0.6 nA versus 0.57 ± 0.1 nA, p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test, n = 15, n = 10), while analysis of the EPSC waveforms indicated no change in the release kinetics. To determine if the increase in AP-evoked release was due to an increase in RRP or initial Pr, we conducted fiber stimulation at 300 Hz, which is similar to sound-evoked firing rates (Sonntag et al., 2009). Analysis of the RRP size revealed a dramatic increase of the RRP in the CaV2.1 α1 OE calyces for both the SMN and NpRf method (Figure 8I). Calculation of initial Pr by dividing the first EPSC by the RRP size demonstrated that CaV2.1 α1 OE increased initial Pr compared to control (SMN, 0.19 ± 0.03 versus 0.08 ± 0.02, p = 0.0024, Mann-Whitney U test; NpRf, 0.18 ± 0.03 versus 0.07 ± 0.01 versus, p = 0.0067, two-tailed t test, n = 14, n = 10). The increase in Pr was further confirmed as we found reduced facilitation and an increased rate of depression in the CaV2.1 α1 OE calyces versus control. These results demonstrate that the increase in CaV2.1 channels results in increased synaptic strength that is due to increases in both the Pr and the RRP in the mature calyx of Held. Therefore, we conclude that the increased CaV2.1 channel numbers are located within the AZs and that AZs are not saturated in vivo.

Figure 8. Increased CaV2.1 Levels at AZs Increase Pr and RRP Size at P20/21 Calyx.

(A) Average basal EPSC.

(B) EPSC peak amplitudes (p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test, n = 10 for control and n = 15 for CaV2.1 α1 OE).

(C) Basal EPSC normalized to peak.

(D) Average 300 Hz EPSC trains for control (left, n = 10) and CaV2.1 α1 OE (right, n = 14).

(E) 300 Hz train EPSC peak amplitudes.

(F) 300 Hz train EPSC absolute peak amplitudes normalized to first EPSC.

(G) Cumulative EPSC amplitudes.

(H) 300 Hz paired-pulse ratio (PPR, p = 0.04, t test).

(I) RRP quantified with corrected SMN and NpRf methods (p = 0.0109 and p = 0.0177, respectively, Mann-Whitney U test, n = 10 for control and n = 14 for CaV2.1 α1 OE).

(J) Release probability Pr quantified with corrected SMN and NpRf methods (p = 0.0024 and p = 0.0067, respectively, Mann-Whitney U test). All data are shown as mean ± SEM. See also Table S6.

DISCUSSION

By overexpressing the CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 α1 subunits in a native neuronal circuit at two distinct developmental stages, we determined CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 preference and saturation states at the presynaptic AZ and their impact on synaptic transmission and plasticity. Based on our data, we conclude that in vivo presynaptic AZs with mixed CaV2 composition which are CaV2.1 dominate, or CaV2.1 exclusive are not saturated for CaV2.1 and prefer CaV2.1. Therefore, we propose that synaptic plasticity and strength can be modulated by increasing CaV2.1 levels in both mixed CaV2 and CaV2.1-exclusive synapses to increase efficacy and to diversify information encoding by neuronal circuits.

In general, our results contrast with studies based on primary cultured CA3/CA1 hippocampal neurons at mixed CaV2 subtype, CaV2.1 dominate synapses (Cao et al., 2004; Cao and Tsien, 2010; Hoppa et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2015). The ability of CaV2.1 α1 OE to increase CaV2.1 levels may be due to conditions specific to the network activity of the native neuronal circuits which is not replicated in in vitro cultured neuronal circuits. Since the CaVβ and α2δ auxiliary subunits of the CaV2 channel complex and the synprint region are critical for trafficking CaV2 channels to the presynaptic terminal and control CaV2 levels in the plasma membrane (Catterall, 2011), it is possible that these trafficking pathways to the presynaptic terminal are saturated for CaV2.1 in cultured hippocampal neurons, but not in a native setting. Finally, we only analyzed the impact of chronic CaV2.1 overexpression 6–7 days post-expression, while prior studies measured CaV2.1 levels at the presynaptic terminal after 2 weeks post-expression (Hoppa et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2015). Thus, it is possible that chronic overexpression of CaV2.1 on the time course of weeks may result in a homeostatic reduction in CaV2.1 levels at the calyx.

In previous studies, CaV2.2 α1 OE led to a complete loss of CaV2.1-mediated AP-evoked release (Cao and Tsien, 2010; Schneider et al., 2015). However, it is important to note that our experimental paradigms were different. We used HdAd vectors (Montesinos et al., 2016) in combination with high-level transgene expression, pUNISHER (Chen et al., 2013; Montesinos et al., 2011; Young and Neher, 2009), to overexpress the mouse CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 α1 subunit in a synapse within its native neuronal circuit at two well-defined developmental time points. In contrast, prior studies expressed human CaV2.1 and human or rabbit CaV2.2 α1 subunit cDNA in a mixed population of hippocampal synapses at an in vitro neuronal circuit. Therefore, the differences in our results are likely due to multiple reasons: differences between cDNAs used (mouse versus human, rabbit), synapse types, synapse developmental stages, neuron environment in vivo versus in vitro, and use of SDS-FFRL immuno-EM versus fluorescence microscopy to detect CaV2.1 levels in the presynaptic terminal.

Our findings demonstrate that CaV2.1 current increases were correlated with increased CaV2.1 channel numbers with no changes in AZ zone size and provide evidence for the existence of unoccupied slots at the AZ. Our SDS-FFRL immune-EM measurements detected on average a 2- to 3-fold channel increase per 30 nm cluster at both the P7 and the P21 plasma membrane, which represents a 40% and 20% increase, respectively. Furthermore, at both developmental time points we found an increase in gold particle density per cluster area. However, although we found a decrease in the inter-particle distance in P7 CaV2.1 OE calyces, we found no change at P21. Since CaV2.1 channels represent only ~60%–70% of ICa at the P7 calyx, while the P20/21 calyx is CaV2.1 exclusive, the 40% increase at P7 compared to the 20% increase at P21 is likely due to the replacement of CaV2.2 with CaV2.1 in addition to filling the unoccupied slots and may explain the ability to more tightly pack CaV2.1 channels at P7 compared to P21. More importantly, since we found an increase in gold particle density but not a decrease in the inter-particle distance in CaV2.1 clusters at the P21 calyx, this suggests there is a limit on the packing of CaV2.1 channels. Regardless, in both cases these levels of increase are likely not detectable in studies using fluorescent measurements to qualitatively count CaV2.1 numbers due to technical limitations (Hoppa et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2015). However, overexpression of a CaV2.1 α1 EGFP tagged subunit did lead to an ~20% increase in EGFP signal in presynaptic boutons (Hoppa et al., 2012). Since AP-evoked release is highly dependent on the location of CaV2 channels within the AZ (Schneggenburger and Rosenmund, 2015), it is an indirect readout of CaV2 channel localization. Thus, our observation that AP-evoked release was dramatically increased indicates that CaV2.1 channels were localized within the AZ.

Since defining the AZ with SDS-FFRL immuno-EM is difficult (Hagiwara et al., 2005; Holderith et al., 2012; Indriati et al., 2013; Miki et al., 2017; Nakamura et al., 2015), it was possible that AZ size increased to accommodate more channels. Although we were unable to accurately measure the AZ area with SDS-FFRL immuno-EM technique due to the lack of presynaptic morphological signatures, we relied on using a 100 nm radius to measure the putative AZ area, the rationale being that the putative AZ sizes measured under control conditions are similar to previous AZ area measurements using ultrathin section TEM (Dong et al., 2018; Sätzler et al., 2002; Taschenberger et al., 2002). However, our putative AZ measurements are inherently biased, since they depend on CaV2.1 labeling. For example, we likely underestimated the putative AZ size at the P7 calyx in our control calyces by 30%−40%, since CaV2.1 channels represent only ~60%–70% of ICa. Heavy metal staining with ultrathin TEM using the PSD density as a measure of presynaptic AZ length is independent of CaV2 labeling and therefore a more accurate measure of AZ length, since AZ and PSD scale in a 1:1 manner (Clarke et al., 2012). However, we cannot rule out that the presynaptic AZ increased independent of the postsynaptic side.

The molecular identity of slots is unknown. Currently, there is no correlation between the levels of key AZ proteins implicated to control either CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 levels at different synapses (Althof et al., 2015; Holderith et al., 2012; Indriati et al., 2013; Lenkey et al., 2015; Miki et al., 2017; Nakamura et al., 2015). Although RIMs (Han et al., 2011; Kaeser et al., 2011; Müller et al., 2012) and CAST/ELKS (Dong et al., 2018; Kittel et al., 2006) control CaV2 levels, currently bassoon is the only AZ protein proposed to specifically control CaV2.1 channel levels compared to CaV2.2 channels (Davydova et al., 2014). However, mutant CaV2.1 channels lacking the bassoon binding interaction domain can rescue CaV2.1 channel levels similarly to wild-type levels (Lübbert et al., 2017). Additionally, knockdown of bassoon or combined knockout of bassoon and piccolo has no effect on basal AP-evoked release at the CaV2.1 exclusive calyx (Parthier et al., 2018), and CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 mEOS-tagged protein levels appear to be equivalent at bassoon-positive punctae (Schneider et al., 2015).

Alternatively, it is possible that slots do not exist. Evidence in support of this hypothesis comes from work in Drosophila, where it was demonstrated that CaV2 channels arrive first at the presynaptic plasma membrane and are then followed by AZ proteins (Fouquet et al., 2009). In addition, CaV2.2 and CaV2.1 have been found to be interspersed and not mutual exclusive within the presynaptic AZ (Lenkey et al., 2015). However, whether this is universal to all presynaptic AZs is not known, as specific antibody staining for CaV2.2 is difficult because the conditions for specific staining in different presynaptic AZs need to be developed. Regardless, in the scenario in which slots do not exist, multiple processes that control CaV2 trafficking, insertion, retention, and stability to the plasma membrane may all contribute to give the appearance of a slot in the AZ. Thus, differences between the different CaV2 α1 subunits and their interactions with CaVβ, synprint sites, AZ proteins (Catterall, 2011; Müller et al., 2010; Simms and Zamponi, 2014), and ubiquitination pathways (Felix and Weiss, 2017) will be critical for CaV2 subtype levels in the AZ. In addition, alternative splicing of CaV2 α1 subunits which impacts these pathways will diversify CaV2 α1 presynaptic specificity (Lipscombe et al., 2013). Finally, since many AZ protein isoforms are expressed in different synapses (Nusser, 2018), it is likely that CaV2 preference in the AZ varies between synapses and with development. In support of this scenario, we found variable competition in CaV2.2 αl OE for CaV2.1 channels at the P7 calyx, suggesting that AZs at P7 calyces are not homogenous for CaV2 preference, and we found that CaV2.2 α1 OE results in appearance of a small CaV2.2 current that corresponded to ~10% of the overall ICa in the P21 calyx. In addition, CaV2.2 channels cannot entirely compensate for the loss of CaV2.1 channels at the calyx (Inchauspe et al., 2004) or in mature CA1 hippocampal neurons (Mallmann et al., 2013). Finally, although α2δ proteins are critical for CaV2 channel trafficking, a previous report indicates that α2δ proteins do not differentially regulate individual CaV2 subtype levels (Hoppa et al., 2012). Although α2δ overexpression led to increased CaV2 channel numbers (Hoppa et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2015), this was paralleled by increases in AZ size (Schneider et al., 2015).

The prehearing calyx utilizes microdomain release (Bollmann et al., 2000; Schneggenburger and Neher, 2000), while the P21 calyx utilizes nanodomain release (Fedchyshyn and Wang, 2005). The increased synaptic strength at CaV2.1 α1 OE was caused by higher Pr at P7, while at P20/21 both Pr and RRP were increased with no change in quantal amplitude. These findings suggest that CaV2.1 level increases differentially impact synaptic strength in microdomain and nanodomain release synapses. What could be the reasons? Recent work has suggested that CaV2.1 cluster numbers in the presynaptic plasma membrane correlate to the functional RRP size in CaV2.1 nanodomain synapses (Miki et al., 2017). However, at P21 we found no increases in the number of CaV2.1 clusters in the putative AZs. Although SV docking is considered the morphological correlate of the functional RRP (Rollenhagen et al., 2007), our morphological data from P20/21 calyces demonstrate a reduction in SV docking that is not in agreement with the functional RRP size. In addition, although we found larger CaV2.1 clusters in P7 calyces, we did not find increases in SV docking. This discrepancy may be due to our fixation methods using PFA, which may not accurately represent SV docking states (Siksou et al., 2007) and may result in preferential depletion of docked SVs in the CaV2.1 OE calyces during PFA fixation (Smith and Reese, 1980). Regardless, prior studies indicate that SV docking does not correlate with the functional RRP size (Neher, 2015; Sakamoto et al., 2018; Thanawala and Regehr, 2013). Although changes in post-priming can increase SV fusogenicity which increases mEPSC frequency and the functional RRP size (Basu et al., 2007), we found no change in mEPSC frequencies in P20/21 CaV2.1 OE terminals, indicating post-priming changes that increase SV fusogenicity are not responsible for the increase RRP size.

Although individual AZs have multiple release sites (Maschi and Klyachko, 2017), recent modeling studies have indicated that a perimeter release model accurately reproduces calyx release characteristics (Chen et al., 2015; Nakamura et al., 2015). In this model, increases of CaV2.1 number will increase Pr at individual release sites, which will lead to increases in AP evoked release. However, one CaV2 channel can theoretically trigger SV release at nanodomain synapses due to tight coupling (Stanley, 2016). Therefore, it is possible that increases in the perimeter due to more CaV2.1 channels lead to the RRP increase only in the mature calyx. In this scenario, since increases in CaV2.1 will increase the number of open CaV2.1 channels in response to APs, the tight coupling state will increase the probability that SVs located around the perimeter will be released in response to repetitive AP stimulation.

In summary, our findings counter prevailing views that CaV2.1 channel levels are saturated at presynaptic active zones. Since modulation of synaptic strength is a fundamental process that regulates synaptic transmission and plasticity and CaV2 channels are key targets of regulation (Davis and Müller, 2015), our findings provide important insights into how CaV2.1 channels are modulated to regulate synaptic transmission and plasticity at different synaptic release modalities in native neuronal circuits. Future studies will resolve the molecular mechanisms and their signaling pathways and physiological conditions by which CaV2 levels are regulated at the presynaptic active zone in different synapses.

STAR★METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Samuel M. Young, Jr., at samuel-m-young@uiowa.edu.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

Custom written software used for series resistance compensation and offset correction used in this study is available as part of the Patcher’s Power Tools (RRID:SCR_001950). Other custom software used in this study is available under https://doi.org/10.17632/4ycrjtpfc6.1.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animals

For all experiments C57Bl6 mice (Jackson Laboratories; RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664) of both sexes at age P7 or P20/P21 were used for analysis, while both sexes were used at age P1 or P14 for stereotaxic surgery. Animals were bred in-house at 12/12h light/dark cycle and had access to food and water ad libitum. All procedures were performed in accordance with the animal welfare laws of the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience and University of Iowa Institutional Animals Care and Use Committee and complied with accepted ethical best practice.

METHOD DETAILS

Helper-Dependent Adenoviral vectors

The CaV2.1 α1 (Mus musculus, Accession No.: NP_031604.3) or CaV2.2 α1 subunit cDNA (Mus musculus, Accession No.: NP_001035993.1) were each codon optimized for expression in mouse (GeneArt) and cloned individually into the EcoRI and NotI sites of the pUNISHER expression cassette (Montesinos et al., 2011; Young and Neher, 2009). Next, the expression cassettes were cloned into pdelta28E4 (kindly provided by Dr. Philip Ng) (Palmer and Ng, 2003) which also contained a separate neurospecific expression cassette to drive either EGFP or mEGFP (Lübbert et al., 2017). The final HdAd plasmid allows for expression of CaV2.1 or CaV2.2 independently of EGFP or mEGFP.

Production of HdAd was carried out as previously described (Montesinos et al., 2016; Palmer and Ng, 2011). Briefly, pHdAd was linearized by Pmel to expose the ends of the 5’ and 3’ inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) and then transfected into 116 producer cells (Profection® Mammalian Transfection System, Promega). For HdAd production, helper virus (HV) was added the following day. 48h post infection, after cytopathic effect (CPE), cells were subjected to three freeze/thaw cycles. Lysate was amplified in a total of five serial coinfections of HdAd and HV from 3× 6 mm tissue culture dishes followed by a 15 cm dish and finally 30 × 15 cm dishes of 116 cells (confluence ~90%). HdAd was purified by CsCl ultracentrifugation and stored at −80 °C in storage buffer (in mM): 10 HEPES, 250 sucrose, 1 MgCl2 at pH 7.4.

HdAd titering and quality control

HdAds were titered by qPCR as described previously (Puntel et al., 2006). The purified reference virus (RV); Ad5-CMV-EGFP (UNC, Gene Therapy Center, Chapel Hill, North Carolina) was titered by endpoint dilution and by transducing units, as described previously (Bewig and Schmidt, 2000). Human Adenovirus 5 Adenovirus Reference Material (ARM) was purchased from ATCC (VR-1516) (Palmer and Ng, 2003). To titer the HdAd by qPCR, adenoviral gDNA from HdAd, RV and ARM was purified from 6 cm plates. Plates were seeded with 3.75 × 106 HEK293 cells in DMEM with 10% FBS and coinfected with HdAd plus RV on the following day at a multiplicity of 100 vp/cell. The cells were incubated for 1 hr at 37°C with 5% CO2 and washed to remove unabsorbed virions. Cells were harvested 4 hr post-infection, then washed with 1 mL PBS and centrifuged for 5 min at 4°C. Pellets were resuspended in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, lysed by freeze/thaw cycles and treated with 20 U/mL Benzonase for 10 min. Subsequently, lysate was incubated in ProtK-SDS solution for 3 hr at 50°C. After protein precipitation with 1.65 M NaCl on ice, DNA was precipitated from supernatants with isopropanol and 3 M sodium acetate, pH 5.2. Samples were mixed well and incubated for 1 hr at −80°C then spun at 4°C for 30 min. Pellets were washed with cold ethanol, dried and resuspended in 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0. A plasmid standard containing three specific DNA sequences; Ad5 E1a (replication-competent Adenovirus (RCA) detection), Ad5 E2B Iva2 (viral DNA polymerase and terminal protein precursor, HV-exclusive), and Ad genomic stuffer sequence (Cosmid 346 and HPRT1 gene, in all HdAd-exclusive) was used. Three specific primer/probe sets were used for these 3 regions in the plasmid for the detection in qPCR:

Ad5 E1a (RCA): probe: NED-5’-AGCACCCCGGGCACGGTTG-3’-MGBNFQ; fwd: 5’-GGGTGAGGAGTTTGTGTTAGATTA TG-3’; rev: 5’-TCCTCCGGTGATAATGACAAGA-3’

E2B Iva2 (HV): probe: FAM-5’-TGTCTTTCAGTAGCAAGCT-3’-TAMRA, HV fwd primer: 5’-TGGGCGTGGTGCCTAAAA-3’, rev: 5’-GCCTGCCCCTGGCAAT-3’

Genomic stuffer DNA (HdAd): probe: VIC-5’- AGCCTCTCTCATCTCACAGT -3’-MGBNFQ, fwd: 5’-CCCCGCTACCCCA ATCC-3’, rev: 5’-TTAGCTTTTTTGGGTGATTTTTCC-3’.

Sample DNA was diluted 1:103, 1:104 or 105 in 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0. For HdAd and HV probes, a 6-point standard curve was constructed with the plasmid standard using 107- 102 molecules/well. For RCA detection, two 7-point curves were constructed with 107 - 10 molecules/well (one plasmid standard and one using ARM gDNA spiked with 107 copies of HdAd gDNA). Real-Time PCR parameters were 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of: 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min. Outliers and results out of range of standard curve were discarded. Results within range of the standard curve were corrected for their dilution and determined as HdAd vector genomes/mL. All samples were negative for RCA.

To determine the IU copies/mL from purified coinfection samples, averaged results were divided by 3 μL and multiplied by 25 μL giving IU copies/coinfection. Next, this number was divided by the volume in μL of HdAd added to the coinfection giving IU copies/μL then multiplied by 1000 to obtain the Infectious HdAd genomes/mL.

Calculation to determine the titer of purified HdAd virus:

where Ad5-CMV-EGFP is RV, RV infectivity is VP/IU. IU is the average titer of end point dilution and transducing unit assays, HdAd vector genomes and RV genomes are the number of genomes from purified virus as determined by qPCR, and infectious HdAd genomes and infectious RV genomes are the number of genomes in DNA purified from coinfections.

HdAd CaV2.1 α1 OE_mEGFP had a physical titer of 3.42*1012 VP/mL, and an infectious titer of 2.44*1011 IU/mL; 14:1 VP/IU. HdAd CaV2.2 α1 OE_ mEGFP had a physical titer of 4.39*1012 VP/mL, and an infectious titer of 2.40*1011 IU/mL; 18:1 VP/IU.

Stereotaxic viral vector injections

HdAds were injected into the cochlear nucleus (CN) of C57BL/6J mice at postnatal day 1 (P1) using a stereotaxic injection approach (Chen et al., 2013). Briefly, P1 mice were anesthetized by hypothermia, using an ice bath for 5 min. Injection of 1.5 μL of HdAds expressing either CaV2.1 α1 and EGFP, CaV2.1 α1 and mEGFP, or CaV2.2 α1 and mEGFP (~2.4×108 transducing units (TU)/μL) into the CN at a rate of 1 μL/min was performed using a glass needle (Blaubrand; IntraMARK). To dissipate the pressure, the needle was slowly removed two or three minutes after the injection. Afterwards, animals were placed under a warm lamp at ~37°C until fully recovered and were returned to their respective cages with their mothers.

For HdAd injections at P14, mice were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane inhalation and kept under 2% isoflurane throughout the procedure. Subcutaneous injection of physiological saline, lidocaine, bupivacaine and meloxicam was used to treat loss of liquid and alleviate pain. The fur on the scalp was removed chemically using hair remover lotion (Nair, Church & Dwight, UK). After cleaning and aseptic treatment with betadine and ethanol the skin was cut along the anterior-posterior axis. Injection site was determined using the Neurostar Stereodrive software (Neurostar) and corrected for head orientation and tilt. A small hole (diameter <1 mm) was drilled into the skull using a foot-pedal controlled drill MH-170 (Foredom). Virus solution identical to that used at P1 was injected via a 3.5” glass pipet (Drummond) at a rate of 100 nl/min with a nanoliter injector (NanoW, Neurostar) at 4 different positions, distance from lambda: (i) anterio-posterior (AP) −0.79, medio-lateral (ML) −2.34, dorso-ventral (DV) 5.4), (ii) AP −1.09, ML −2.34, DV5.4, (iii) AP −0.79, ML −2.44, DV 5.4, (iv) AP −1.09, ML-2.44, DV 5.4). After the injection, the skin was sutured, and the animal was kept under supervision until fully recovered. Afterwards it was returned to its mother.

Electrophysiology

During all experiments, slices were continuously perfused with standard aCSF at RT (~25°C) and visualized by an upright microscope (BX51WI, Olympus) through a 60x water-immersion objective (LUMPlanFL N, Olympus) and either CCD (QI-Click, QImaging) or EMCCD camera (LucaEM S, Andor™ Technology, Belfast, UK). Patch-clamp recordings were performed by using an EPC 10/2 patch-clamp amplifier, controlled by Patchmaster Software (HEKA, RRID:SCR 000034). Data were acquired at a sampling rate of 50 kHz and low-pass filtered at 6 kHz. To allow identification of calyces transduced with HdAd expressing CaV2.1 α1 OE or CaV2.2 α1 OE, we co-expressed mEGFP as a marker. To visualize mEGFP, slices were illuminated at 470 nm wavelength using a Lumen 200 metal arc lamp (Prior Scientific) or a Polychrome V xenon bulb monochromator (ThermoFisher).

Preparation of acute slices

Acute brainstem slices were prepared as previously described (Chen et al., 2013). Briefly, after decapitation, the brains were immersed in ice-cold low-calcium artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF, in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 10 glucose, 25 NaHCO3,1.25 NaHPO4, 0.4 L-ascorbic acid, 3 myo-inositol, and 2 Na-pyruvate, pH 7.3-7.4 (310 mOsmol). Coronal slices containing the MNTB were obtained using a vibrating tissue slicer (either Campden 7000 smz; Campden Instruments LTD or Leica VT1200; Leica Biosystems). Slices were immediately transferred to standard aCSF (37°C, continuously bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2) containing the same as the low-calcium aCSF but with 1 mM MgCl2and 1-2 mM CaCl2 (further specified below). After 45 min incubation, slices were transferred to a recording chamber with the same extracellular buffer at room temperature (RT: ~25°C).

Presynaptic recordings

To isolate presynaptic Ca2+ currents, the standard aCSF was supplemented with 1 μM tetrodotoxin (TTX; Tocris Bioscience), 100 μM 4-aminopyridin (4-AP; Tocris) and 20 mM tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA-Cl; Sigma Aldrich) to block Na+ and K+ channels. Calyces were whole-cell voltage clamped at −80 mV. Current-voltage relationships were recorded in the presence of 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM CaCl2, while pharmacological isolation of VGCC subtypes was performed in 2 mM CaCl2. We used 200 nM ω-agatoxin IVA (Alomone labs) to selectively block CaV2.1 (P/Q-type) VGCCs and 2 μM ω-conotoxin GVIA (Alomone labs) for selective inhibition of CaV2.2(N-type) VGCCs and supplemented 0.1 mg/mLcytochrome C to prevent toxin adsorption. All remaining Ca2+ channels were blocked by 50 μM CdCl2. At P20/21 application of Cd2+ was not necessary because Ca2+ currents were completely blocked in presence of ω-agatoxin IVA and ω-conotoxin GVIA. Presynaptic patch pipettes were pulled to 4.5-6 MΩ and were filled with the following (in mM): 145 Cs-gluconate, 20 TEA-Cl, 10 HEPES, 2 Na2-phosphocreatine, 4 MgATP, 0.3 NaGTP, and 0.5 EGTA, pH 7.2, 325-340 mOsmol). Sylgard coating was used to improve voltage-clamp quality. Presynaptic series resistance was between 6 and 25 MU (usually between 10-15 MΩ) and was compensated online to 6 MΩ with a time lag of 10 μs by the HEKA amplifier.

Afferent fiber stimulation

To trigger AP-evoked neurotransmitter release, we performed afferent fiber stimulation as previously described (Forsythe and Barnes-Davies, 1993). Briefly, a bipolar electrode (FHC Inc.) was placed halfway between the brainstem midline and MNTB. Recordings were performed in aCSF containing 1 mM MgCl2 and 1.2 mM CaCl2. Pipettes for postsynaptic recordings were pulled to a resistance of 2.5-4 MΩ and were filled with the same solution as presynaptic pipettes, but with 5 mM EGTA and 6 mM QX-314 (Sigma Aldrich). Postsynaptic MNTB principal neurons were voltage clamped to a holding potential of −60 mV. The standard aCSF was supplemented with 50 μM D-AP5 to block NMDA receptors (Tocris Bioscience), 20 μM bicuculline and 5 μM strychnine (Tocris Bioscience) to block inhibitory inputs. Furthermore, 0.25 mM (P7) or 1 mM (P20/21) kynurenic acid (Tocris Bioscience) was added to avoid saturation of postsynaptic AMPA receptors. Postsynaptic Rs (<8 MΩ) was online compensated to Rs <3 MΩ. The remaining Rs was further compensated offline to 0 MΩ for all EPSCs with custom IgorPro routine (Traynelis, 1998).

Miniature postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs)

Miniature postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) were recorded with 2 mM CaCl2 in the aCSF. MNTB principal neurons were whole-cell voltage-clamped at −80 mV and aCSF was supplemented with 50 mM D-AP5, 20 mM bicuculline, 5 mM strychnine, 1 mM TTX and 20 mM TEA. For all recordings, series resistance was <8 MΩ and not compensated.

ELECTRON MICROSCOPY

Pre-embedding Immuno-Electron Microscopy

Wild type (C57BL/6J) and CaV2.1 α1 OE injected mice, P7 and P21 were anesthetized with Tribromoethanol (250 mg/kg of body weight, i.p.) and perfused transcardially with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM Sørensen’s phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) followed by fixative solution containing 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), 0.1% or 0.5% glutaraldehyde, and 0.2% picric acid in 100mM Sørensen’s phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4) for 7-9 min. Brains were post-fixed with 4% PFA in PB overnight and 50 μm coronal sections of the brainstem were obtained on a vibratome (Leica VT1200). Expression of EGFP at calyx of Held terminals was visualized using an epifluorescence inverted microscope (CKX41, Olympus) equipped with an XCite Series 120Q lamp (Excelitas technologies), and only EGFP positive samples were further processed as previously reported (Montesinos et al., 2015). After washing with PB, sections were cryoprotected with 10%, 20% and 30% sucrose in PB and submersed into liquid nitrogen for permeabilization, then thawed. Then sections were incubated in a blocking solution containing 10% normal goat serum (NGS), 1% fish skin gelatin (FSG), in 50 mM Tris-buffered saline (TBS, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4) for 1h, and incubated with an anti-GFP antibody (0.1 μg/mL, Abcam, cat# ab6556, RRID:AB_305564) diluted in TBS containing 1% NGS, 0.1% FSG plus 0.05% NaN3 at 4°C for 48h. After washing with TBS, sections were incubated overnight in nanogold conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:100, Nanoprobes, Cat# 2003) diluted in TBS containing 1% NGS and 0.1% FSG. Immunogold-labeled sections were washed in PBS, briefly fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS, and silver intensified using HQ silver intensification kit (Nanoprobe). After washing with PB, they were treated with 0.5% OsO4 in 0.1M PB for 20 min, en-bloc stained with 1% uranyl acetate, dehydrated and flat embedded in Durcupan resin (Sigma-Aldrich). After trimming out the MNTB region, ultrathin sections were prepared with 40 nm-thickness using an ultramicrotome (EM UC7, Leica). Sections were counterstained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined in a Tecnai G2 Spirit Bio-Twin transmission electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 100kV acceleration voltage. Images were taken with a Veleta CCD camera (Olympus) operated by TIA software (FEI). Images used for quantification were taken at 60,000x magnification.

SDS-digested freeze fracture replica immunogold labeling

CaV2.1 α1 OE-injected mice harboring myristoylated EGFP were anesthetized with tribromoethanol (250 mg/kg of body weight, i.p.) and perfused transcardially with PBS followed by 2% PFA, and 0.2% picric acid in 0.1M PB for 12 min. 130 μm-thick coronal sections of brainstem were obtained using a vibratome (Leica VT1200). Only those samples showing mEGFP expression were selected. The brain slices containing the MNTB region were cryoprotected in 10%, 20% for 30 min each and 30% glycerol at 4°C overnight. Small pieces containing MNTB region were trimmed out and frozen using a high pressure freezing machine (HPM100, Leica). Frozen samples were fractured in two halves using a double replication device at −120°C, replicated first with a 2 nm carbon deposition, shadowed from 60 degree angle by carbon-platinum of 2 nm and supported by a final carbon deposition of 20-30nm, using a JFDV Freeze fracture machine (JEOL/Boeckeler). The tissue was dissolved by placing the replicas in a digesting solution containing 2.5% SDS, 20% sucrose and 15mM Tris-HCl (pH8.3) with gentle agitation in an oven at 82.5°C for 18 hours. The replicas were washed and blocked with 4% BSA and 1% FSG in TBS for 1 hour, then incubated with a mixture of primary antibody; rabbit anti- GFP (1 μg/mL, AbCam cat#ab6556, RRID:AB_305564) and guinea pig anti-CaV2.1 α1 subunit (0.7 μg/mL, Synaptic Systems cat# 152205, RRI-D:AB_2619842) diluted in 0.04% BSA and 0.01% FSG in TBS for 18 h at room temperature. After several washes, the replicas were incubated in donkey anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to 6 nm gold particles and donkey anti-guinea pig IgG conjugated to 12 nm gold particles (1:30; Jackson ImmunoResearch; RRID:AB_2340585 and RRID:AB_2340465) diluted in 0.04% BSA and 0.01% FSG in TBS for 18 h at room temperature. After being washed, the replicas were picked up on 100-parallel-bar copper grids or aperture grids and examined with a Tecnai G2 Spirit BioTwin transmission electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 100 kV acceleration voltage. Images were taken with a Veleta CCD camera (Olympus).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Electrophysiological data analysis

All data were analyzed offline with Fitmaster (Harvard Instruments, RRID:SCR_016233) and custom routines in Matlab (version 9.3; Mathworks, RRID:SCR_001622) or IgorPro (version 6.37, Wavemetrics, RRID:SCR_000325) equipped with Patcher’s Power Tools (version 2.19, RRID:SCR_001950). Voltage-dependence of Ca2+ channel activation was described by peak of the steady state current as well as tail currents as functions of voltage. Peak currents were fitted with an IgorPro routine according to a Hodgkin-Huxley formalism with four independent gates assuming a Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) open-channel conductance Γ(V) as function of voltage:

| (1) |

with Erev as reversal potential, Vm as half-maximal activation voltage per gate, and km as the voltage-dependence of activation. Tail currents were measured as peaks minus baseline and fitted with an IgorPro routine according to a Boltzmann formalism:

| (2) |

with V0.5 as half-maximal activation voltage and k voltage-dependence of activation. EPSCs were measured as peak minus baseline preceding the EPSC.

Miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) were analyzed using a custom written script in IgorPro provided by H. Taschenberger based on (Clements and Bekkers, 1997). All events were manually curated and non-linear least-square fit with a multi-exponential equation of the form:

| (3) |

Fitting of the events was performed in Matlab using the Trust-Region-Reflective fitting algorithm and mEPSC amplitudes were derived from the fit. Overlapping events were first deconvolved with a template mEPSC to determine their onset and then fit as a linear sum of multi-exponential equations.

Readily-releasable pool (RRP) approximations

The afferent fiber stimulation data were used to determine the RRP with a back-extrapolation method (SMN, (Neher, 2015; Schneggenburger et al., 1999). Briefly, the cumulative EPSC amplitude vs. stimulus number was plotted and then back extrapolated with a line fit from the steady state increase of cumulative EPSC amplitudes. To account for the underestimation in pool sizes due to incomplete pool depletion we applied a correction method assuming no change in Pr throughout the train (p0/pn = 1) and no replenishment between 1st and 2nd pulse (Neher, 2015). Release probability was calculated by dividing the first EPSC by the respective RRP. Additionally, a pool depletion model (NpRf model, (Thanawala and Regehr, 2016) was used to fit EPSCs using theTrust-Region-Reflective fitting algorithm with N0 (initial RRP size), p0 (initial release probability) and R (replenishment rate) being constrained to positive values. For the NpRf model, Pr was determined during the fit and defined as EPSC0/N0.

TEM image analysis for active zone length and synaptic vesicle numbers

We identified calyces which were positive for EGFP expression by immunogold labeling with an anti-GFP antibody and compared EGFP-positive terminals (CaV2.1 α1 OE) to EGFP-negative terminals (control) in the same slice. All TEM data were analyzed using Fiji imaging analysis software (RRID:SCR_002285, http://fiji.sc)(Schindelin et al., 2012). Each presynaptic active zone (AZ) was defined as the membrane directly opposing postsynaptic density, and the length of each AZ was measured. Vesicles within 200 nm of each AZ were manually selected and their distances relative to the AZ were calculated using a 32-bit Euclidean distance map generated from the AZ. For data analysis, vesicle distances were binned every 5 nm and counted. Vesicles less than 5 nm from the AZ were considered “docked” (Taschenberger et al., 2002). At least three animals for each condition and 40 AZs per animal were analyzed.

Replica image collection and analysis

Presynaptic P-faces (protoplasmic face of the cell membrane) of the calyx of Held were morphologically identified by existence of cross-fractured cytoplasm containing synaptic vesicles and/or by existence of glutamate receptor clusters uniquely shown on the adjacent E-face (exoplasmic face) of the postsynaptic cell of principle neuron of MNTB (Budisantoso et al., 2012; Nakamura et al., 2015). Specifically, immunogold-labeled presynaptic P-faces that were in contact with the postsynaptic soma were imaged at 43,000x magnification. mEGFP-positive presynaptic P-faces were identified by the existence of 6 nm immunogold particles as CaV2.1 α1 OE terminals, and mEGFP-negative calyx terminals were categorized as control. We analyzed the distribution and number of CaV2.1 from the 12 nm immunogold labeling in both mEGFP positive and negative terminals. Between seven and thirteen individual P-faces, including small to large pieces, were analyzed for each condition, comprising 50-165 μm2 of P-face area respectively. For each continuous P-face, images were manually stitched and minimally adjusted for brightness and contrast (Adobe Photoshop CS6), and 12 nm gold particles corresponding to CaV2.1 channels were thresholded and quantified using Microscopy Image Browser (RRID:SCR_016560(Belevich et al., 2016). A custom macro was used in Fiji to extend a circle with a 30nm and a 100 nm radius from each 12 nm gold particle to form clusters of closely distributed CaV2.1 channels (Althof et al., 2015; Nakamura et al., 2015). Cluster size and the number of particles within clusters were then analyzed. The parameters “Gold particle # per cluster”, “Cluster area” and “Gold particle density per cluster area” are derived from the 30 nm analysis. The parameters “Gold particle density per putative AZ” and “Putative AZ area” derived from the 100 nm analysis. By combining both the 30 nm and 100 nm analyses we derived “Cluster number per putative AZ” defined as all 30 nm clusters within 100 nm radius and “single Gold particles per putative AZ” which correspond to all single particles within 100 nm radius/AZ. The nearest neighbor distance of CaV2.1 channels was calculated as the minimal Euclidean distance of each gold particle to all other gold particles within the same cluster.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical tests were conducted in Prism 7 (RRID:SCR_002798, GraphPad Software) and Matlab. All data were tested for normal distribution by performing a Shapiro-Wilk test for normality and variances of all data were estimated and compared using Levene’s test. To account for unequal variance between two groups, t test with Welch’s correction was applied. In case of unequal variance between three groups, Mood’s median test with a post hoc Bonferroni test was performed. Electrophysiological data were compared with unpaired t test or Mann-Whitney U test when comparing two groups and Kruskal-Wallis test with a post hoc Dunn’s test, when comparing more than two groups using the control dataset for comparison. Since our hypothesis was that CaV2.1 α1 OE increased CaV2.1 levels at the AZ, one-tailed tests were used for comparing ICaand CaV2.1 numbers and clusters. Patch clamp recordings lacking proper clamp quality or with high leak (>100 pA presynaptic, >200 pA postsynaptic) were excluded from data sets. Only EPSC trains without failures were used to quantify RRP size and Pr. EM data were compared using unpaired t test or Mann-Whitney U test. The contingency of the distribution of clustered and single nanogold particles in SDS-FFRL data were assessed with Fisher’s exact test. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. Statistical significance was accepted at * P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001; **** P<0.0001. In figures and tables, data are reported as mean ± SEM, unless otherwise stated.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti-GFP | Abcam | Cat# ab6556; RRID:AB_305564 |

| Guinea pig anti-alpha 1A | Synaptic systems | Cat# 152205; RRID:AB_2619842 |

| 6 nm colloidal Gold-AffiniPure Donkey anti rabbit IgG | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 711005152; RRID:AB_2340585 |

| 12 nm colloidal Gold-AffiniPure Donkey anti guinea pig IgG | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 706205148; RRID:AB_2340465 |

| Nanogold IgG goat anti rabbit IgG (H+L) Antibody | Nanoprobes | Cat# 2003; RRID:AB_2687591 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| HdAd 28E4 pun CaV2.1 α1 syn mEGFP | Young Laboratory, University of Iowa | N/A |

| HdAd 28E4 pun CaV2.1 α1 syn EGFP | Young Laboratory, University of Iowa | N/A |

| HdAd 28E4 pun CaV2.2 α1 syn EGFP | Young Laboratory, University of Iowa | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Kynurenic acid | Tocris Bioscience | Cat# 0223 |

| Lidocaine N-ethyl bromide (QX-314) | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# L5783 |

| D-AP5 | Tocris Bioscience | Cat# 0106 |

| (−)-Bicuculline methochloride | Tocris Bioscience | Cat# 0131 |

| Strychnine hydrochloride | Tocris Bioscience | Cat# 2785 |

| 4-Aminopyridine | Tocris Bioscience | Cat# 0940 |

| Tetraethylammonium chloride | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# T-2265 |

| Tetrodotoxin | Alomone labs | Cat# T-550 |

| ω-Agatoxin AgaIVA | Alomone labs | Cat# STA-500 |

| ω-Conotoxin GVIA | Alomone labs | Cat# C-300 |

| Cadmium chloride hemi(pentahydrate) | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# C3141 |

| Lucifer Yellow | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# L0259 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mice: C57BL/6J | Jackson Laboratory | Cat# JAX:000664; RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Ad5 E1a (RCA) probe: NED-5’-AGCACCCCGGGC ACGGTTG-3’-MGBNFQ | This study | N/A |

| Ad5 E1a (RCA) fwd: 5’-GGGTGAGGAGTTTGTGT TAGATTATG-3’ | This study | N/A |

| Ad5 E1a (RCA) rev: 5’-TCCTCCGGTGATAATGAC AAGA-3’ | This study | N/A |

| E2B Iva2 (HV) probe: FAM-5’-TGTCTTTCAGTAGC AAGCT-3’-TAMRA | This study | N/A |

| E2B Iva2 (HV) fwd: 5’-TGGGCGTGGTGCCTAAAA-3’ | This study | N/A |

| E2B Iva2 (HV) rev: 5’-GCCTGCCCCTGGCAAT-3’ | This study | N/A |

| Genomic stuffer DNA (HdAd) probe: VIC-5’- AGC CTCTCTCATCTCACAGT -3’-MGBNFQ | This study | N/A |

| Genomic stuffer DNA (HdAd) fwd: 5’-CCCCGCTA CCCCAATCC-3’ | This study | N/A |

| Genomic stuffer DNA (HdAd) rev: 5’-TTAGCTTTTT TGGGTGATTTTTCC-3’ | This study | N/A |

| CaV2.1 α1 subunit cDNA (Mus musculus) | NCBI | NP_031604.3 |

| CaV2.2 α1 subunit cDNA (Mus musculus) | NCBI | NP_001035993.1 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Matlab | The Mathworks | RRID:SCR_001622; v9.3, v9.5 |

| Patchmaster | HEKA; Harvard Bioscience | RRID:SCR_000034; v2×90.2 |

| Igor Pro | Wavemetrics | RRID:SCR_000325; v6.37 |

| Prism | Graphpad software | RRID:SCR_002798; v7.04 |

| Fiji | https://fiji.sc/ | RRID:SCR_002285 |

| Fitmaster | HEKA; Harvard Bioscience | RRID:SCR_016233; v2×90.2 |

| Patcher’s Power Tools | Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry; Gottingen; Germany | RRID:SCR_001950; v2.19 |