Abstract

Background

The use of biomarkers to target anti-EGFR treatments for metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) is well-established, requiring molecular analysis of primary or metastatic biopsies. We aim to review concordance between primary CRC and its metastatic sites.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis of all published studies (1991–2018) reporting on biomarker concordance between primary CRC and its metastatic site(s) was undertaken according to PRISMA guidelines using several medical databases. Studies without matched samples or using peripheral blood for biomarker analysis were excluded.

Findings

61 studies including 3565 patient samples were included. Median biomarker concordance for KRAS (n = 50) was 93.7% [[67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100]], NRAS (n = 11) was 100% [[90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100]], BRAF (n = 22) was 99.4% [[80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100]], and PIK3CA (n = 17) was 93% [[42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100]]. Meta-analytic pooled discordance was 8% for KRAS (95% CI = 5–10%), 8% for BRAF (95% CI = 5–10%), 7% for PIK3CA (95% CI = 2–13%), and 28% overall (95% CI = 14–44%). The liver was the most commonly biopsied metastatic site (n = 2276), followed by lung (n = 438), lymph nodes (n = 1123), and peritoneum (n = 132). Median absolute concordance in multiple biomarkers was 81% (5–95%).

Interpretation

Metastatic CRC demonstrates high concordance across multiple biomarkers, suggesting that molecular testing of either the primary or liver and lung metastasis is adequate. More research on colorectal peritoneal metastases is required.

Keywords: Biomarker, Concordance, Colorectal cancer, RAS, BRAF, PIK3CA

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Genetic mutations in key biomarkers are known to predict outcomes and response to treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer. Concordance in these biomarkers between the primary and metastatic sites is an important factor to consider with both diagnostic and therapeutic implications. We systematically reviewed all published comparative studies reporting on biomarker concordance between primary and metastatic sites. These studies were identified using PubMed, MEDLINE, Ovid, Embase, Cochrane, and Google Scholar databases. Biomarkers that were studied included KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, PIK3CA and PTEN, among others.

Added value of this study

This study provides a comprehensive review of the concordance rates of genetic biomarker mutations between primary and metastatic sites in colorectal cancer. This allows us to quantify the predictive value of a metastatic site biopsy in determining the biomarker mutation status of the primary colorectal cancer. It also presents what is currently known about biomarker concordance by metastatic site.

Implications of all the available evidence

This study demonstrates a high genetic concordance rate between primary colorectal cancers and their liver/lung metastases. Despite peritoneal metastases being the third most common site, little remains known about their concordance with the primary colorectal cancer. There is currently no evidence that multiple metastatic site biopsies will provide benefit, with single sites sufficient for diagnosis and biomarker profiling provided adequate samples can be taken. This has important implications for reducing the time to diagnosis, commencement of treatment, and cost.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. Introduction

Approximately 1.4 million patients per annum worldwide are diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC). Metastatic (stage IV) disease at presentation results in a 5-year overall survival (OS) of 14% [1,2], whilst 50% of patients undergoing surgery with curative intent develop metastatic disease within 5 years [3]. The most commonly reported sites include lymph nodes (35–40%) [4], liver (50–60%) [5,6], lung (10–30%) [7], and peritoneum (5–20%) [[8], [9], [10]].

Advances in biological therapies such as anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibodies (cetuximab and panitumumab) have resulted in biomarkers being used to target metastatic CRC (mCRC) [11]. KRAS is a key proto-oncogene downstream of EGFR and is activated in up to 50% of sporadic mCRC patients, with 95% of activations occurring in codons 12/13 of exon 2 [12]. Importantly, KRAS exon 2–4 mutations (involving codons 12, 13, 161, 117 & 146) demonstrate a significantly lower response to cetuximab and panitumumab [13,14]. Some studies have also indicated that KRAS mutations may confer resistance to bevacizumab [15,16]. The extended RAS family of oncogenes includes NRAS, with exon 2–4 mutations occurring in 3–5% of CRC's and similarly resulting in a lower response [17,18]. BRAF, a RAF gene kinase and immediate downstream effector of KRAS, shows mutations in nearly 10% of colorectal adenocarcinomas and is also a strong negative prognostic marker, predicting resistance to both cytotoxic and anti-EGFR therapy [[19], [20], [21]].

Mutations in genes other than those constituting the RAS/RAF pathway include PIK3CA and PTEN [22]. Approximately 15–20% of patients with mCRC, have mutations in exon 20 of PIK3CA and demonstrate resistance to cetuximab even in the presence of KRAS wild type [23]. Loss of expression of PTEN, a natural inhibitor of PI3K-initiated signalling, has itself also been associated with unresponsiveness to cetuximab and reduced OS [24,25]. Beyond the factors associated with EGFR signalling pathways, a number of other genes are significantly mutated in CRC, including APC (51–81%), TP53 (20–60%), and SMAD4 (10–20%) [12]. APC is the most prevalent gene in the establishment of sporadic colorectal malignancy [26]. Similar to APC, the TP53 gene is heavily involved in the malignant transformation of CRC, with mutation in TP53 resulting in a non-functional p53 protein and reduced OS [[27], [28], [29], [30]]. Unlike APC and TP53, which usually occur in early colorectal tumorigenesis, inactivation of SMAD4 is associated with late-stage or metastatic disease [31]. SMAD4, also known as DPC4, encodes a tumour suppressor that regulates transcriptional activity downstream of TGF-beta receptor signalling. Expression of SMAD4 is an important prognostic factor in CRC, with patients who retain higher levels of SMAD4 within their tumours having higher OS than those with low or absent expression [32,33].

This study aims to systematically review the literature and undertake meta-analysis where appropriate in order to determine the concordance between primary CRC and its metastatic site, with regards to the above-mentioned biomarkers and their combinations. It also aims to determine the variation in concordance by metastatic site, and the ‘absolute concordance’ in multiple biomarkers for mCRC. This is important for two reasons: First, it has implications for the understanding of how tumours evolve and differ between the primary and metastatic site. Studies demonstrating the dynamic changes in circulating DNA of mCRC patients with the clonal evolution and resistance to anti-EGFR treatments with time have suggested that the CRC genome adapts to drug schedules, providing a molecular explanation for changes in efficacy with re-challenge anti-EGFR therapies [34]. Second it also has implications for personalized treatment strategies used for patients based on single site biopsies [35,36]. This study tries to shed light in respect to the heterogeneity (studied as mutational discordance) between the primary and metastatic sites in light of evidence that significant intra-tumour heterogeneity exists between different points on the same primary CRC specimen [37]. There are cases where the primary tumour cannot be accessed, in which case knowledge on concordance between the metastatic sites (liver, lung, lymph node or peritoneum) is important.

2. Methods

This systematic review was undertaken in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [38]. A literature search was undertaken by two independent reviewers (DB and OA) of all published studies using PubMed, MEDLINE, Ovid, Embase, Cochrane, and Google Scholar databases using the following MeSH terms: “colorectal neoplasm”, “peritoneal neoplasm” and “mutation”, plus additional search terms including: “primary colorectal cancer”, “metastasis”, “biomarker”, and “concordance”. Further references were identified manually using the bibliographies of relevant papers and review articles. Equal consideration was given to fully published studies and those available in only abstract form.

2.1. Study selection

Studies were included provided that patients had a confirmed diagnosis of metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma, and mutational biomarker analysis on biopsies both from the colorectal primary and at least one site of metastasis. Studies were excluded if the primary and metastatic tumour samples were unmatched, concordance was reported in relation to peripheral blood samples instead of solid tumour, or there was insufficient data available to provide a value for concordance. The method and extent of mutational analysis was not a criterion for exclusion. In this study the biomarker concordance between primary tumour and metastasis was defined in terms of both mutant and wild-type pairs, and not limited to the mutant-only population.

2.2. Meta-analysis

The proportion of changes (discordance proportion) with exact 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was calculated for each study. The Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation was the chosen approach for the calculation of pooled estimates and corresponding 95% CIs [39,40]. If a study had a sample size below 10, the arcsine transformation was preferred. Random effects pooled estimates were calculated in order to take into account heterogeneity between estimates [41]. Statistical heterogeneity among studies was evaluated using the chi-square test statistic and was measured using the I2 statistic, which is the proportion of total variation contributed by between-study variance tau-squared (τ2) [42]. Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots and the asymmetry test developed by Egger et al. [43]

All analyses were carried out with R software (http://cran.r-project.org/) with packages ‘meta’ and ‘metafor’. All the reported P values were two sided.

3. Results

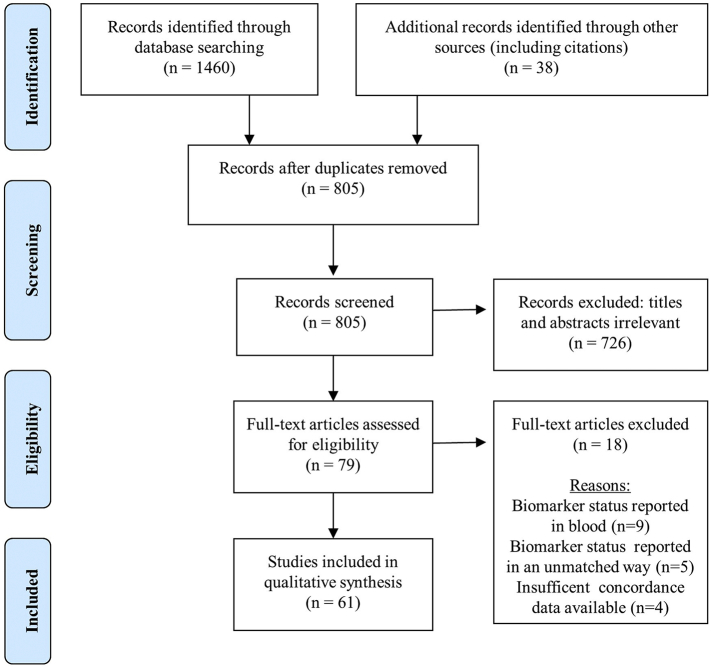

Literature search identified 1498 studies reporting on concordance in mCRC between 1991 and 2018. Of these, 61 articles including 3565 patients matched the selection criteria and were deemed suitable for qualitative synthesis as outlined in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search.

3.1. Concordance between primary CRC and its metastatic site

Concordance in individual biomarker status in patients with mCRC was reported in a range of oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes. The median reported concordance was 93.7% (range 67–100) for KRAS (n = 50) [24,[44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93]], 99.4% (range 80–100) for BRAF (n = 22) [44,45,48,49,54,60,61,[63], [64], [65],[67], [68], [69],71,[73], [74], [75], [76],79,80,83,86], 93% (range 42–100) for PIK3CA (n = 17) [44,[48], [49], [50], [51],53,54,[58], [59], [60],63,65,[67], [68], [69],73,76], 92.9% (range 73–100) for TP53 (n = 12) [44,48,[51], [52], [53],[58], [59], [60],63,64,68,87], and 100% (range 90–100) for NRAS (n = 11) [44,48,49,51,56,59,60,63,68,69,93]. Less commonly reported markers included: PTEN (n = 10) [24,44,48,53,63,67,71,76,79,94], APC (n = 10) [44,48,[51], [52], [53],58,59,63,64,88], SMAD4 (n = 6) [51,53,54,58,63,64], and EGFR (n = 5) [24,71,79,95,96]. Additional data was also available on the concordance of MSI status and MMR genes (n = 5) [45,48,65,97,98]. Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 summarize the concordance rates for KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA, the three most commonly studied biomarkers.

Table 1.

KRAS biomarker studies (n = 50).

| Study | Year | N | Analysis | Codons | Sites of metastasis | Concordance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moorcraft et al. | 2017 | 15 | NGS | – | Lu | 92 |

| Fujiyoshi et al. | 2017 | 457 | NGS | 12, 13, 61 | L + D | 96.9 |

| Petaccia de Macedo et al. | 2017 | 97 | Pyro | 12, 13, 61 | L + D | 97.9 |

| Pang et al. | 2017 | 72 | ARMS PCR | – | L + D | 81.9 |

| Nemecek et al. | 2016 | 12 | NGS | 12, 13, 22, 61, 117, 146 | L + D | 75 |

| Li et al. | 2016 | 58 | qRT-PCR + NGS | 12, 13 | D | 81 |

| He et al. | 2016 | 59 | PCR | 12, 13, 61, 117 | D | 76.3 |

| Kovaleva et al. | 2016 | 14 | NGS | 12, 13 | D | 78.6 |

| Crumley et al. | 2016 | 16 | NGS | – | L + D | 93.8 |

| Vignot et al. | 2015 | 13 | NGS | – | D | 100 |

| Jesinghaus et al. | 2015 | 24 | NGS | – | L + D | 100 |

| Siyar-Ekinci et al. | 2015 | 31 | Pyro | – | D | 77.4 |

| Lau et al. | 2015 | 82 | Sanger | 12, 13, 61 | D | 88.1 |

| Lee et al. | 2015 | 74 | Seq | 12, 13 | L + D | 79.7 |

| Lim et al. | 2015 | 34 | NGS + Sanger | – | Li | 97 |

| Kim et al. | 2015 | 19 | NGS | 12, 13, 61 | L + D | 100 |

| Kleist et al. | 2014 | 151 | Seq | 12, 13, 61 | L + D | 86.8 |

| Giannini et al. | 2014 | 17 | PCR + Pyro | 12, 13 | L + D | 82.4 |

| Paliogiannis et al. | 2014 | 31 | Seq | 12, 13, 61 | D | 90.3 |

| Brannon et al. | 2014 | 69 | NGS | – | D | 100 |

| Lee et al. | 2014 | 15 | NGS | – | Li | 80 |

| Murata et al. | 2013 | 26 | Pyro | 12 | L + D | 94 |

| Miglio et al. | 2013 | 45 | Seq | 12, 13 | L + D | 100 |

| Vakiani et al. | 2012 | 84 | Sanger | 12, 13, 22, 61, 117, 146 | L + D | 97.6 |

| Vermaat et al. | 2012 | 21 | NGS + Sanger | 12, 13, 61, 146 | Li | 85.7 |

| Knijn et al. | 2011 | 305 | Seq | 12, 13 | Li | 96.4 |

| Park et al. | 2011 | 17 | Seq | 12,13 | L + D | 76 |

| Watanabe et al. | 2011 | 43 | Seq | 12, 13 | D | 88.4 |

| Baldus et al. | 2010 | 75 | Pyro | – | L + D | 74.7 |

| Italiano et al. | 2010 | 64 | Seq | – | – | 94.9 |

| Mariani et al. | 2010 | 38 | Seq | 12, 13 | D | 97 |

| Perrone et al. | 2009 | 12 | Seq | 12, 13 | D | 80 |

| Cejas et al. | 2009 | 110 | Seq | 12, 13 | D | 94 |

| Garm-Spindler et al. | 2009 | 31 | qPCR | 12, 13 | D | 93.5 |

| Loupakis et al. | 2009 | 53 | Seq | 12, 13 | D | 95 |

| Molinari et al. | 2009 | 38 | Seq | 12, 13 | L + D | 92 |

| Gattenlöhner et al. | 2009 | 21 | AS-PCR | 12, 13 | L + D | 95 |

| Etienne-Grimaldi et al. | 2008 | 48 | PCR-RFLP | 12, 13 | Li | 100 |

| Santini et al. | 2008 | 99 | Seq | 12, 13 | D | 96 |

| Artale et al. | 2008 | 48 | Seq | 12, 13 | D | 94 |

| Gattenlohner et al. | 2008 | 106 | Seq | 12, 13 | L + D | 99 |

| Weber et al. | 2007 | 38 | Seq | 12, 13 | Li | 94.7 |

| Oliveira et al. | 2007 | 28 | – | – | L | 67.9 |

| Albanese et al. | 2004 | 30 | PCR-SSCP | 12, 13 | Li | 70 |

| Zauber et al. | 2003 | 42 | Seq | 12, 13 | L + D | 100 |

| Tórtola et al. | 2001 | 51 | SSCP + Seq | 12, 13 | BM | 70 |

| Al-Mulla et al. | 1998 | 58 | PCR ASO | 12, 13 | L + D | 87 |

| Suchy et al. | 1992 | 109 | PCR ASO | 12 | – | 100 |

| Losi et al. | 1992 | 35 | AS-PCR | 12, 13 | L + D | 100 |

| Oudejans et al. | 1991 | 31 | Seq | 12, 13, 61 | D | 93.5 |

N = no. of patients with matched samples

L = local metastasis e.g. loco-regional lymph nodes

D = distant metastasis e.g. liver, lung, peritoneum, omentum, mesentery, brain, bone, ovary, uterus, vagina, small intestine, adrenal gland, pancreas

Li = Liver only

Lu = Lung only

BM = Bone marrow only

Abbreviations: ARMS, amplification-refractory mutation system analysis; ASO, allele-specific oligonucleotide hybridisation; AS-PCR; allele-specific polymerase chain reaction; NGS, next generation sequencing; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism; Pyro, pyrosequencing; qPCR; quantitative PCR; qRT, quantitative reverse transcription; Sanger, sanger sequencing; Seq, sequencing; SSCP, single-stranded conformation polymorphism; −, information unavailable/unspecified.

Table 2.

BRAF biomarker studies (n = 22).

| Study | Year | N | Analysis | Codons | Sites of metastasis | Concordance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moorcraft et al. | 2017 | 15 | NGS | – | Lu | 100 |

| Fujiyoshi et al. | 2017 | 457 | PCR-RFLP | 600 | L + D | 100 |

| Nemecek et al. | 2016 | 12 | NGS | 600 | L + D | 92 |

| Li et al. | 2016 | 10 | NGS | – | D | 80 |

| Jesinghaus et al. | 2015 | 24 | NGS | – | D | 100 |

| Lee et al. | 2014 | 15 | NGS | – | Li | 93.3 |

| Kleist et al. | 2014 | 151 | PCR Seq | – | L + D | 98.7 |

| Giannini et al. | 2014 | 17 | PCR + Pyro | 600 | L + D | 94.1 |

| Brannon et al. | 2014 | 69 | NGS | – | D | 100 |

| Murata et al. | 2013 | 26 | Pyro | 600 | L + D | 100 |

| Voutsina et al. | 2013 | 83 | Sanger + ARMS AS-PCR | 600 | D | 100 |

| Vermaat et al. | 2012 | 21 | NGS + Sanger | 600 | Li | 100 |

| Vakiani et al. | 2012 | 84 | Sanger | 600 | L + D | 100 |

| Park et al. | 2011 | 20 | Seq | 600 | L + D | 90 |

| Mariani et al. | 2010 | 38 | Seq | 600 | D | 100 |

| Italiano et al. | 2010 | 48 | PCR Seq | – | – | 97.9 |

| Baldus et al. | 2010 | 75 | Pyro | 600 | L + D | 97.4 |

| Perrone et al. | 2009 | 12 | PCR Seq | 600 | D | 90.1 |

| Molinari et al. | 2009 | 38 | PCR Seq | 600 | L + D | 100 |

| Gattenlöhner et al. | 2009 | 21 | AS-PCR | 600 | D | 100 |

| Artale et al. | 2008 | 48 | Seq | 600 | D | 98 |

| Oliveira et al. | 2007 | 28 | – | 600 + 601 | L | 89.3 |

N = no. of patients with matched samples

L = local metastasis e.g. loco-regional lymph nodes

D = distant metastasis e.g. liver, lung, peritoneum, omentum, mesentery, brain, bone, ovary, uterus, vagina, small intestine, adrenal gland, pancreas

Li = Liver only

Lu = Lung only

BM = Bone marrow only

Abbreviations: ARMS, amplification-refractory mutation system analysis; AS-PCR; allele-specific polymerase chain reaction; NGS, next generation sequencing; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; Pyro, pyrosequencing; Sanger, sanger sequencing; Seq, sequencing; SSCP, single-stranded conformation polymorphism; −, information unavailable/unspecified.

Table 3.

PIK3CA biomarker studies (n = 17).

| Study | Year | N | Analysis | Codons | Site of metastases | Concordance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moorcraft et al. | 2017 | 15 | NGS | – | Lu | 86.7 |

| Li et al. | 2016 | 10 | NGS | – | D | 100 |

| He et al. | 2016 | 59 | PCR Seq | 542, 545, 1047 | D | 42.4 |

| Kovaleva et al. | 2016 | 14 | NGS | 542, 545, 1047 | D | 92.9 |

| Nemecek et al. | 2016 | 12 | NGS | 542, 545, 1047 | L + D | 83 |

| Vignot et al. | 2015 | 13 | NGS | – | D | 100 |

| Jesinghaus et al. | 2015 | 24 | NGS | – | D | 100 |

| Lim et al. | 2015 | 34 | NGS + Sanger | – | Li | 100 |

| Kim et al. | 2015 | 19 | NGS | 542, 545, 1047 | L + D | 100 |

| Kleist et al. | 2014 | 151 | PCR Seq | 542, 545, 1047 | L + D | 97.4 |

| Brannon et al. | 2014 | 69 | NGS | – | D | 94.2 |

| Murata et al. | 2013 | 32 | Pyro | 542, 545, 1047 | L + D | 88 |

| Voutsina et al. | 2013 | 83 | Sanger + ARMS AS-PCR | 525, 545, 1047 | D | 93 |

| Vakiani et al. | 2012 | 84 | Sanger | 345, 420, 542, 545, 546, 1043, 1047 | L + D | 98.8 |

| Vermaat et al. | 2012 | 21 | NGS + Sanger | 542, 545, 1047 | Li | 85.7 |

| Baldus et al. | 2010 | 75 | Pyro | – | L + D | 89.3 |

| Perrone et al. | 2009 | 12 | PCR Seq | 542, 545, 1047 | D | 90.1 |

N = no. of patients with matched samples

L = local metastasis e.g. loco-regional lymph nodes

D = distant metastasis e.g. liver, lung, peritoneum, omentum, mesentery, brain, bone, ovary, uterus, vagina, small intestine, adrenal gland, pancreas

Li = Liver only

Lu = Lung only

BM = Bone marrow only

Abbreviations: ARMS, amplification-refractory mutation system analysis; AS-PCR; allele-specific polymerase chain reaction; NGS, next generation sequencing; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; Pyro, pyrosequencing; Sanger, sanger sequencing; Seq, sequencing; −, information unavailable/unspecified

Other CRC biomarkers infrequently reported in the literature included AKT (n = 4, range 68–90%) [24,48,49,52], CTNNB1 (n = 4, range 95–100%) [44,48,52,54], MET (n = 3, range 75–100%) [48,52,67], and FBXW7 (n = 3, range 83–100%) [44,48,52]. Only two or fewer studies accounted for mutational concordance in the following genes: STK11, KIT, FGFR3, GNAQ, NOTCH, ATM, ARID1A, and FAT4, in addition to various others [44,48,51,52,54,64]. This also included singular studies of mitochondrial microsatellite instability (mtMSI), CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), neuroendocrine differentiation, and microRNA (miRNA) [60,[99], [100], [101]].

3.2. Concordance depending on metastatic site

The liver was the most commonly included metastatic site within studies (n = 53 studies including 2276 patients), followed by the: lung (n = 37 studies including 438 patients), lymph nodes (n = 30 studies including 1123 patients), and peritoneum (n = 17 studies, including 132 patients). 27 studies analysed biomarker concordance separately within these metastatic sites as displayed in Table 4, thus allowing comparison between metastatic location and the possible impact on concordance. Of these studies, 21 gave concordance data specific to liver metastases [[44], [45], [46],[49], [50], [51],53,56,61,[63], [64], [65],69,70,72,77,[80], [81], [82],94,100], 11 for lung metastases [38,42,49,59,60,65,68,[84], [85], [86], [87]] and 12 for lymph nodes [46,47,49,52,57,60,61,67,68,75,84,87]. Only two studies provided separate concordance for peritoneal metastases and likewise only single studies for ovarian and bone metastases were available, with most studies grouping these with other metastatic sites [45,53,63,89].

Table 4.

Concordance studies by metastatic type (n = 27).

| Biomarker concordance according to metastatic site (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Year | Biomarker | LN | Liver | Lung | PTM | Other |

| Kleist et al. | 2017 | mtMSI | 25 | 48 | |||

| Fujiyoshi et al. | 2017 | KRAS | 97.1 | 97.4 | 100 | 98 | 85.7 |

| BRAF | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| MSI/MSS | 98.8 | 100 | - | 92 | 100 | ||

| Moorcraft et al. | 2017 | KRAS | 100 | 93 | 100 | ||

| NRAS | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| BRAF | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| PIK3CA | 100 | 86.7 | 100 | ||||

| 100 | |||||||

| PTEN | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| TP53 | 100 | 100 80 | 100 | ||||

| 100 | |||||||

| APC | |||||||

| Petaccia et al. | 2017 | KRAS | 97.8 | 98.9 | 100 | ||

| Crumley et al. | 2016 | KRAS | 92.3 | 100 | |||

| TP53 | 92.3 | 100 | |||||

| APC | 84.6 | 100 | |||||

| He et al. | 2016 | KRAS | 75.8 | 66.7 | 92.9 | ||

| PIK3CA | 39.4 | 44.4 | 47.1 | ||||

| Kovaleva et al. | 2016 | KRAS | 85.7 | 85.7 | |||

| NRAS | 100 | 100 | |||||

| PIK3CA | 92.9 | 92.9 | |||||

| TP53 | 92.9 | 92.9 | |||||

| 78.6 | |||||||

| APC | 71.4 | 100 | |||||

| SMAD4 | 92.9 | ||||||

| Li et al. | 2016 | KRAS | 100 | 80 | 80 | ||

| NRAS | 100 | 100 | 50 | ||||

| BRAF | 0 | 80 | 100 | ||||

| PIK3CA | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| Vignot et al. | 2015 | KRAS | 100 | 100 | |||

| PIK3CA | 100 | 100 | |||||

| PTEN | 100 | 100 | |||||

| TP53 | 84.6 | 100 | |||||

| APC | 91.7 | 100 | |||||

| SMAD4 | 84.6 | 100 | |||||

| Lau et al. | 2015 | RAS | 100 | 66.7 | |||

| Giannini et al. | 2014 | KRAS | 78.6 | 100 | |||

| BRAF | 92.9 | 100 | |||||

| Kleist et al. | 2014 | KRAS | 88.1 | 83.3 | |||

| NRAS | 99.1 | 97.6 | |||||

| BRAF | 99.1 | 100 | |||||

| PIK3CA | 96.3 | 100 | |||||

| TP53 | 95.4 | 100 | |||||

| Brannon et al. | 2014 | KRAS | 100 | 100 | |||

| NRAS | 100 | 100 | |||||

| BRAF | 100 | 100 | |||||

| PIK3CA | 98.5 | 100 | |||||

| PTEN | 100 | 100 | |||||

| TP53 | 100 | 100 | |||||

| APC | 93.9 | 100 | |||||

| Lee et al. | 2014 | KRAS | 80 | ||||

| BRAF | 93.3 | ||||||

| TP53 | 73.3 | ||||||

| APC | 53.3 | ||||||

| SMAD4 | 93.3 | ||||||

| Atreya et al. | 2013 | PTEN | 98 | ||||

| Murata et al. | 2013 | KRAS | 100 | 94 | |||

| BRAF | 100 | 100 | |||||

| PIK3CA | 100 | 88 | |||||

| MSI | 100 | 96 | |||||

| Vermaat et al. | 2012 | KRAS | 85.7 | ||||

| NRAS | 100 | ||||||

| BRAF | 100 | ||||||

| PIK3CA | 100 | ||||||

| Knijn et al. | 2011 | KRAS | 80 | 96.4 | |||

| Watanabe et al. | 2011 | KRAS | 100 | 100 | |||

| Baldus et al. | 2010 | KRAS | 69 | 90 | |||

| BRAF | 96 | 100 | |||||

| PIK3CA | 87 | 95 | |||||

| Cejas et al. | 2009 | KRAS | 94.6 | 88.2 | |||

| Molinari et al. | 2009 | KRAS | 100 | 92 | |||

| BRAF | 100 | 100 | |||||

| PTEN | 87 | 89 | |||||

| Etienne-Grimaldi et al. | 2008 | KRAS | 100 | ||||

| Gattenlohner et al. | 2008 | KRAS | 98.6 | 99 | 100 | 96 | |

| Santini et al. | 2008 | KRAS | 96 | 80 | |||

| Oliveira et al. | 2007 | KRAS | 67.9 | ||||

| BRAF | 89.3 | ||||||

| Tórtola et al. | 2001 | KRAS | 70 | ||||

Abbreviations: LN, lymph nodes; PTM, peritoneum. ‘Other’ – includes bone, ovary, pancreas etc.

3.3. Absolute concordance

15 studies compared the overall molecular profiles of the matched primary and metastatic sites as shown in Table 5 [44,45,51,52,54,59,60,63,65,69,76,80,83,93,102]. An additional 2 studies reported on somatic variance between matched tumours [103,104]. Studies identified that the greater the number of genes included within the analysis, the lower the rate of absolute concordance. For example, a combination of KRAS and BRAF was concordant in 44 out of 48 of cases (91.7%) but sequencing of >1000 genes in a separate cohort saw concordance fall to only 1 in 19 cases (5.3%) [45,72].

Table 5.

Absolute concordance in all biomarkers (n = 15).

| Study | Year | N | Sequencing | Biomarkers included | Sites of metastases | Absolute (%) concordance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fujiyoshi et al. | 2017 | 257 | NGS | KRAS & BRAF | Li, Lu, LN, PTM | 94.6 |

| Moorcraft et al. | 2017 | 15 | NGS | KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, PTEN, TP53, APC… | Lu | 73 |

| Kovaleva et al. | 2016 | 14 | NGS | KRAS, NRAS, PIK3CA, TP53, APC… | Li, Lu | 57.1 |

| Crumley et al. | 2016 | 16 | NGS | KRAS, TP53 & APC | LN, Li, Lu | 81 |

| Jesinghaus et al. | 2015 | 24 | NGS - 12 genes | KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, PTEN, TP53, APC… | LN, Li, Lu, Br | 84.4 |

| Kim et al. | 2015 | 19 | NGS - 1321 genes | APC, KRAS, TP53, BRAF, PIK3CA… | LN, Li, Lu, Ov | 5 |

| Kleist et al. | 2014 | 42 | DNA PCR | KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA & TP53 | Li, Abw, Ut, Ov, Va, PTM, OTM, SI | 81 |

| Brannon et al. | 2014 | 69 | NGS - 230 genes | KRAS, NRAS, BRAF… | Li, Lu, Ov | 31.9 |

| Murata et al. | 2013 | 32 | Pyro | KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA & MSI | LN, Li | 84 |

| Vermaat et al. | 2012 | 21 | NGS + Sanger | KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA & EGFR | Li | 85.7 |

| Balschun et al. | 2011 | 5 | Sanger + Pyro | KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA & MSI | Li | 20 |

| Perrone et al. | 2009 | 12 | PCR | KRAS, BRAF, PI3KCA & PTEN | Li, Lu, Ut | 58.3 |

| Gattenlöhner et al. | 2009 | 21 | DNA PCR + AS-PCR | KRAS & BRAF | LN, Li, Lu, PTN, Mes, SI, ST | 95 |

| Artale et al. | 2008 | 48 | DNA PCR | KRAS & BRAF | Li, Lu, Ov, LN, Adr, Pan, OTM | 92 |

| Oudejans et al. | 1991 | 31 | DNA PCR | RAS | Li, Lu | 87.1 |

Abbreviations: Abw, abdominal wall; Adr, adrenal gland; AS-PCR; allele-specific polymerase chain reaction; Br, brain; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; Li, liver; LN, lymph node; Lu, lung; Mes, mesocolon; NGS, next generation sequencing; OTM, omentum; Ov, ovary; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PTM, peritoneum; Pyro, pyrosequencing; Sanger, sanger sequencing; SI, small intestine; ST, soft tissue; Ut, uterus; Va, vagina. (…) = additional CRC-related genes but not listed.

3.4. Meta-analysis of the discordance

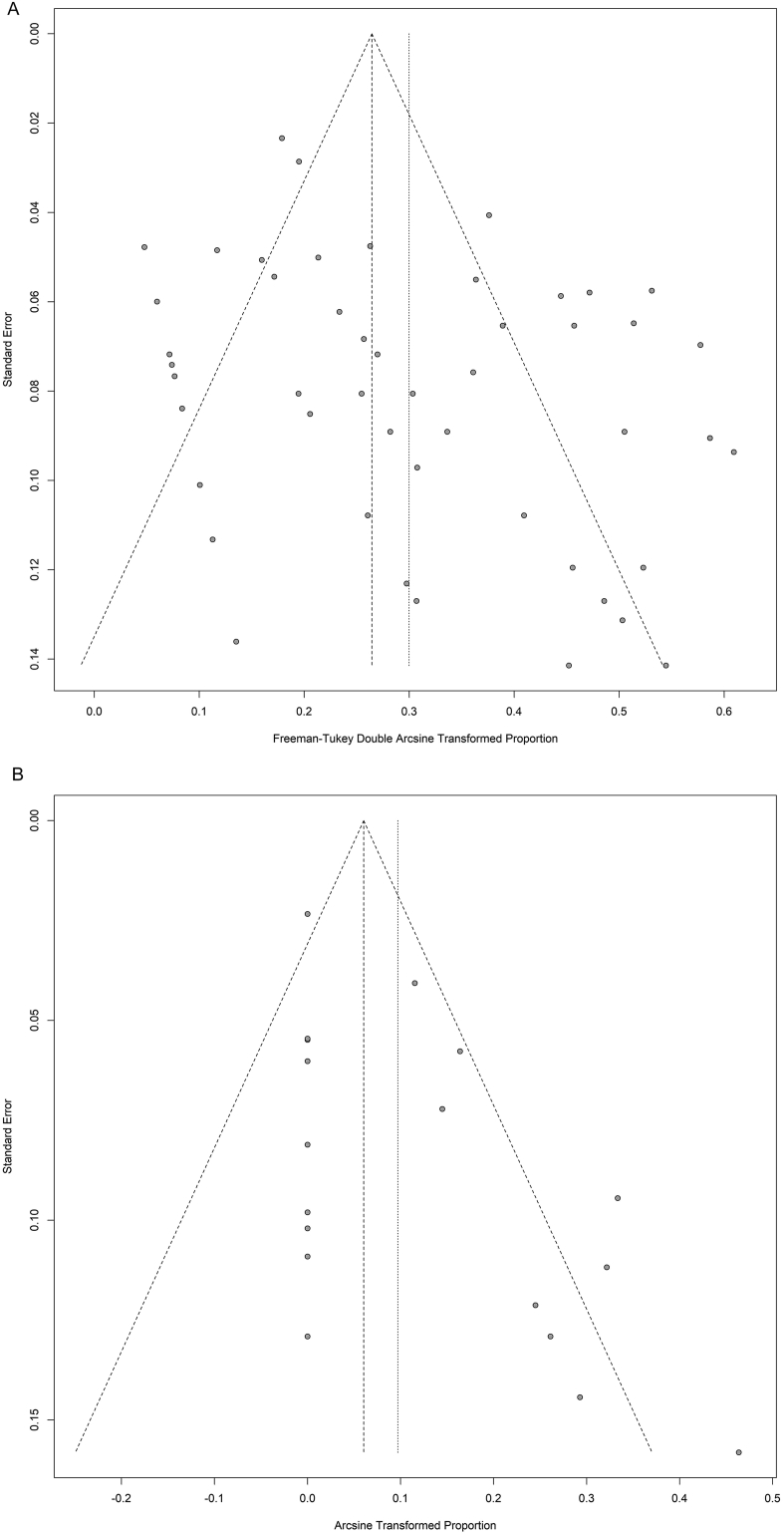

The discordance rate was assessed in 3066 patients for KRAS, 1312 patients for BRAF, 727 patients for PIK3CA and 626 patients with overall molecular profiles. There was no evidence for publication bias for PIK3CA and the overall molecular profiles (labelled as “ALL” in the Supplementary Fig. 1 (Egger's test: p = .76 and p = .08 respectively). However, publication bias was found in KRAS and BRAF studies (Egger's test: p = .01 and p = .01 respectively).

-

(i)

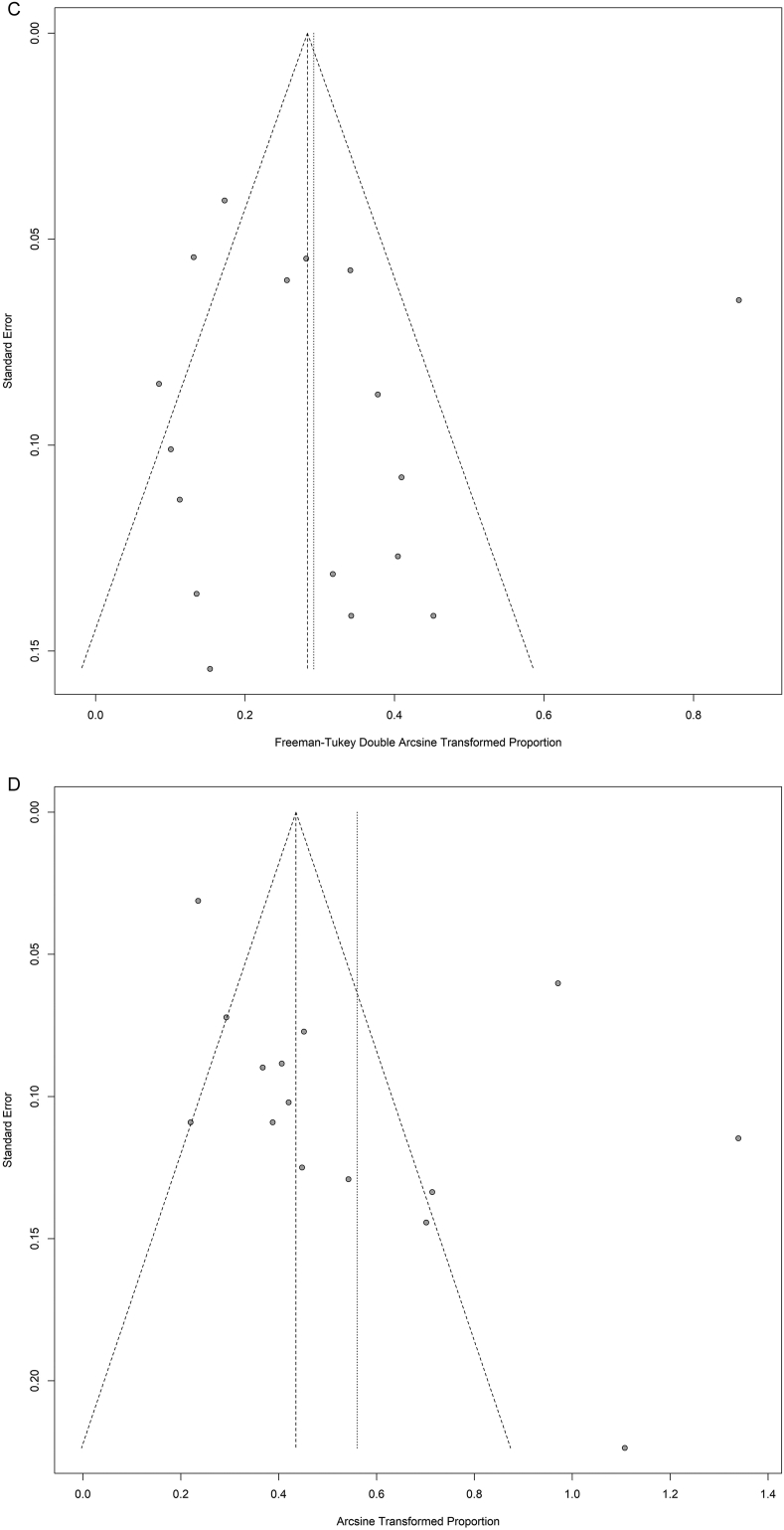

KRAS - Fig. 2 shows the discordance proportions reported for KRAS in each study included in the analysis. The heterogeneity between proportions ranged from 0% to 29% (I2 = 91%, τ2 = 0.012, p < .0001). The meta-analytic pooled discordance proportion was 8% (95% CI: 5–10%).

-

(ii)

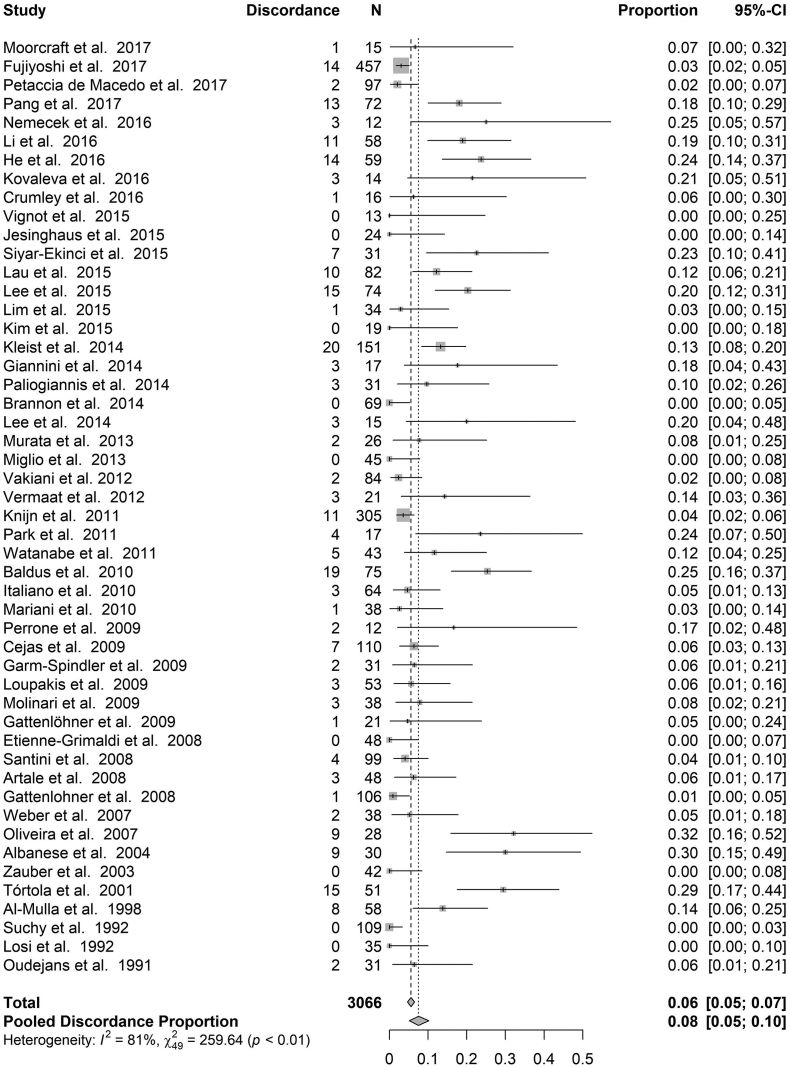

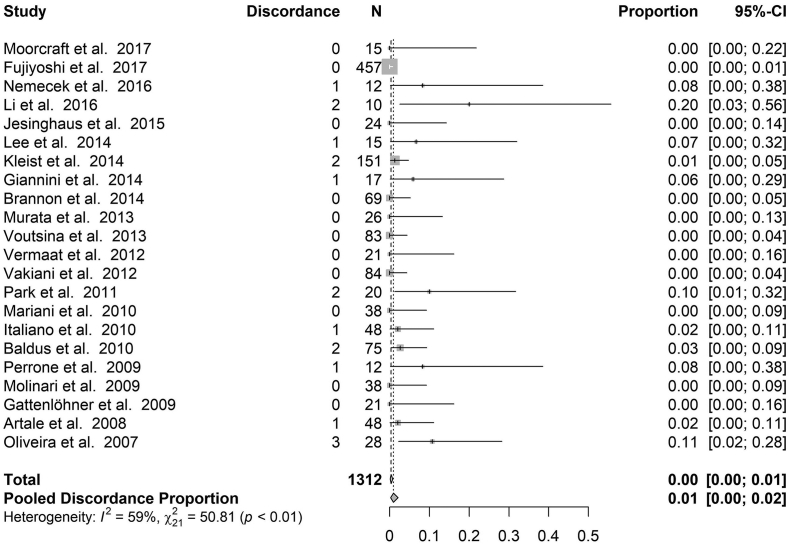

BRAF - Fig. 3 shows the discordance proportions reported for BRAF in each study included in the analysis. The heterogeneity between proportions ranged from 0% to 20% (I2 = 59%, τ2 = 0.007, p < .0003). The meta-analytic pooled discordance proportion was 8% (95% CI: 5–10%).

-

(iii)

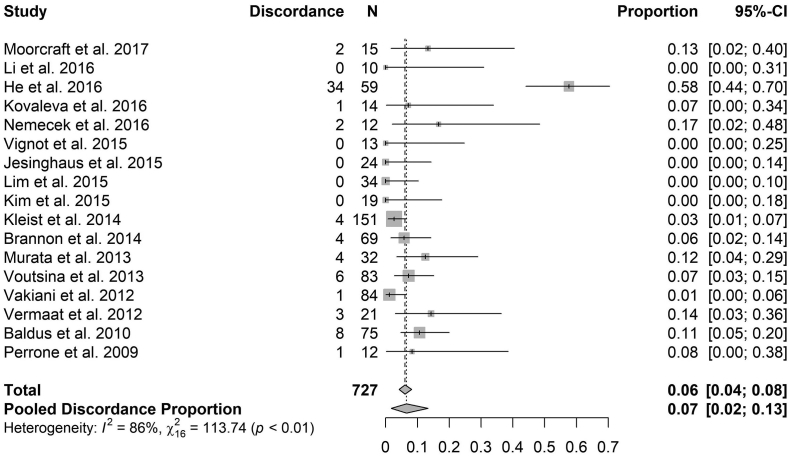

PIK3CA - Fig. 4 shows the discordance proportions reported for PIK3CA in each study included in the analysis. The heterogeneity between proportions ranged from 0% to 58% (I2 = 86%, τ2 = 0.04, p < .0001). The meta-analytic pooled discordance proportion was 7% (95% CI: 2–13%).

-

(iv)

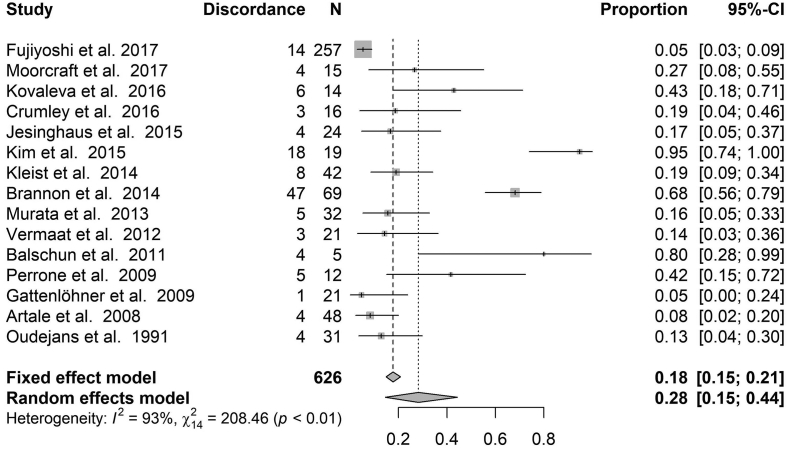

Overall molecular profiles – Fig. 5 shows the discordance proportions reported considering the overall molecular profiles. PIK3CA in for all studies included in the analysis. The heterogeneity between proportions ranged from 5% to 95% (I2 = 93%, τ2 = 0.1, p < .0001). The meta-analytic pooled discordance proportion was 28% (95% CI: 14–44%).

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Funnel plots to study the publication bias of all the subsets analysed. “ALL” labels the studies considering the overall molecular profiles. P-values for asymmetry obtained by the method developed by Egger and colleagues.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for proportion of discordance of KRAS. The estimate proportion and 95% CI interval at the level of the total number of cases reflects the calculation under a fixed effect model. The estimate proportion and 95% CI interval at the level of the Pooled Discordance Proportion are the random effects pooled estimates to take into account heterogeneity.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for proportion of discordance of BRAF. The estimate proportion and 95% CI interval at the level of the total number of cases reflects the calculation under a fixed effect model. The estimate proportion and 95% CI interval at the level of the Pooled Discordance Proportion are the random effects pooled estimates to take into account heterogeneity.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot for proportion of discordance of PIK3CA. The estimate proportion and 95% CI interval at the level of the total number of cases reflects the calculation under a fixed effect model. The estimate proportion and 95% CI interval at the level of the Pooled Discordance Proportion are the random effects pooled estimates to take into account heterogeneity.

Fig. 5.

Forest plot for proportion of discordance of studies considering the overall molecular profiles. The estimate proportion and 95% CI interval at the level of the total number of cases reflects the calculation under a fixed effect model. The estimate proportion and 95% CI interval at the level of the Pooled Discordance Proportion are the random effects pooled estimates to take into account heterogeneity.

4. Discussion

A total of 9 studies reported absolute concordance in KRAS point mutations within codons 12 and 13, despite apparent differences in sequencing methodologies, suggesting the stability in KRAS status between the primary and metastatic sites [53,54,59,63,66,81,88,91,92]. Of note, Tórtola et al. did identify some discordance when using single-stand conformational polymorphism (SSCP) analysis of bone micrometastases [89]. In this study, 17 mutations were found among the primary tumours compared to only 7 in corresponding metastases, and whereas the majority (88%) of mutated KRAS in primary CRC's were located in codon 12, in the bone marrow these mutations were mainly localised to codon 13 (71%) [89]. There are however studies that identified discordance rates in KRAS as high as 30% [86,87]. In the case of Baldus et al., the lower reported concordance was suggested to be attributable to intra-tumour heterogeneity; a phenomenon strongly evidenced in colorectal tumours as well as numerous other solid malignancies [37,73,105,106]. In a comparable study by He et al., a combination of low sensitivity testing and unrepeated mutation analysis of the tissues could have led to false-negatives [50,73]. This is effectively illustrated in the study by Vakiani and colleagues where concordance rates increased by 5% when more sensitive analysis methods were used [68]. KRAS status can therefore be determined from the primary tumour or the metastatic site as long as the sample is sufficient and sequencing technique adequate.

Although significantly fewer studies have evaluated NRAS status compared to KRAS in matched tumours, the available data suggests concordance rates are also high (median of 100%, range 90–100%) regardless of sequencing method [56,60,63]. BRAF notably demonstrated 100% mutation concordance in half of the identified studies, despite similar variances in the type of metastasis sampled and sequencing method [48,54,65,68]. Expanded analysis of BRAF mutations to include exons 11 and 15 did result in a slightly lower concordance (median of 99.4%, range 80–100%), with discordance limited to V600E region of exon 15 [76]. It is important to note that all of the studies reporting lower rates of BRAF concordance demonstrated a small sample size of paired specimens which may have impacted their results. This is aligned to the publication bias detected in this particular subset where usually smaller studies are published only with positive findings. Altogether 7 BRAF studies had sample sizes that were considered small, defined as less than or equal to 20 matched patient samples [49,71,76].

The results for PIK3CA in some cases show a much more discordant relationship between the primary tumour and the metastasis, with a median concordance of 93% (42–100%) [50]. While the aforementioned report is unhindered by its adequate sample size (>50 matched pairs), a combination of the low sensitivity method of sequencing within this study and the unusually high proportion of patients with detected PIK3CA mutation may somewhat explain its contradiction to the rest of the literature [50]. Thus, based on the consistent results of other studies, the concordance rate for PIK3CA is relatively high overall within the average CRC population [60,63,73]. Importantly, this study identified that some of the tumour suppressor genes (PTEN, TP53, APC and SMAD4) can show a more variable and discordant relationship between the primary tumour and the metastasis [59]. Mutation within these tumour suppressors, such as TP53, is at times more common in the metastasis than the primary [68]. However, cumulative data indicate that the PTEN and APC genes are among those demonstrating the greatest variation, revealing less consistency for higher rates of concordance [24,51,52,63,64,67,94]. We also found that although primary tumours and their metastases displayed a variable concordance with regards to MSI and EGFR, the number of studies reporting on these biomarkers was small making our findings difficult to interpret [24,45,95,97]. Nonetheless, EGFR does show notable evidence of a predisposition toward discordant expression [95,96].

This study was also able to determine biomarker concordance by metastatic site, with hepatic metastases most commonly studied and displaying a remarkably concordant relationship with the primary tumour [63,69]. The liver is a site that can be relatively easily biopsied with sufficient sample sizes (core biopsies). In contrast, pulmonary metastases are more challenging to sample and therefore not surprisingly were sampled less frequently than the liver. Much of the variation in concordance with lung metastases may be explained by this. It is however a valid site for biopsy and determination of RAS status. Peritoneal samples were extremely infrequently sampled and would also be potentially more difficult to obtain sufficient tissue from due to their location and size. It is therefore difficult to comment on their relationship with the primary. Only two studies reported on biomarker concordance specifically comparing peritoneal metastases to the primary tumour [45,53]. This suggests the need to investigate this area, particularly as peritoneal metastases have a significantly worse median OS (16.3 months) compared to liver (19.1 months) and lung (24.6 months) metastases [107].

It is not surprising that we found that absolute concordance in more than one biomarker fell as the number of biomarkers was increased. For example limiting analysis to KRAS and BRAF demonstrated a 92–95% concordance [45,80,83], falling to 87% with extended RAS mutation analysis (including KRAS, NRAS and HRAS) [93]. Cohorts tested for KRAS and BRAF as well as additional alterations in PIK3CA/PTEN/TP53/APC demonstrate a more variable absolute concordance ranging from 57 to 84% [44,51,54]. Finally studies comparing 12, 230 and 1321 gene sequencing have demonstrated how absolute concordance falls as more genes are included within the analysis to only 5% [59,63,108]. This suggests that the metastases are distinctly different in their genetic composition to the primary tumour [64]. In any case poor absolute concordance may provide some explanation as to the complexities of colorectal tumours and their resistance to cytotoxic and biological therapies [109]. Furthermore, as metastases generally possess greater mutational load than primary tumours as well as less intra-tumour heterogeneity, basing clinical decision-making on the profile of metastases in preference to generalising the data obtained from primary tumours may be beneficial [64,67].

It is important to note a number of limitations of this study. First it should be noted that the studies included were retrospective and varied in their sample size. This was reflected in the meta-analysis showing a clear publication bias for the KRAS and BRAF papers. Second, there was heterogeneity in sample collection and processing techniques as well as sequencing techniques used which have evolved over time, making absolute comparisons difficult. This would for example explain the higher concordance for newer biomarkers such as NRAS. Third, the patients varied in the systemic treatments they received, and the impact of this on the metastasis (tumour regression after chemo- or radiotherapy) may have affected the sequencing result through adequacy of the sample. Fourth, it is important to note that any change in concordance may represent the evolution of the tumour as it metastasises and therefore the time between the primary tumour and metastasis sampling is an important factor to consider which could not be accounted for. Finally inter-tumour heterogeneity means that sufficient samples may not have been possible to obtain in many of the studies to determine biomarker status especially at the metastatic sites.

Despite the above limitations, we feel that this study has demonstrated high biomarker concordance rate between primary tumours and the metastases with challenges in getting adequate sample size from metastatic sites likely to account for most discordance. This has important practical implications as it suggests there is little evidence for separate biopsy of the primary and metastatic sites. Whether the evolving use of liquid biopsy through circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) analysis adds anything further to a patient's treatment options remains to be seen. We also feel that little information is currently available on peritoneal metastases and this is an area for further research.

5. Conclusion

mCRC demonstrates remarkably high concordance across a number of individual biomarkers, suggesting that molecular testing of either the primary or liver and lung metastasis is adequate for determining biomarker status to personalize treatment. More research is required to determine concordance in colorectal cancer peritoneal metastases which may explain why these tumours have a significantly worse prognosis compared to other sites. Clonal selection and tumour evolution add further inherent complexities that may be addressed through new sampling strategies and novel technologies in development.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Authors' contributions

Dilraj S Bhullar - Literature search, figures, study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing.

Omer Aziz - Literature search, figures, study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing.

Sarah T O'Dwyer - Study design, data analysis, data interpretation, writing.

Jorge Barriuso - Figures, study design, data analysis, data interpretation, writing.

Saifee Mullamitha - Data interpretation, writing.

Mark P Saunders - Data interpretation, writing.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding

None declared.

References

- 1.Noone A., Howlader N., Krapcho M., Miller D., Brest A., Yu M. 2018. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2015. Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Cutsem E., Group on behalf of the EGW, Cervantes A, Group on behalf of the EGW, Nordlinger B, Group on behalf of the EGW Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann Oncol. 2014 Sep 1;25(Suppl_3):iii1–iii9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Dikshit R., Eser S., Mathers C., Rebelo M. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H., Wei X.-Z., Fu C.-G., Zhao R.-H., Cao F.-A. Patterns of lymph node metastasis are different in colon and rectal carcinomas. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Nov 14;16(42):5375–5379. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i42.5375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welch J.P., Donaldson G.A. The clinical correlation of an autopsy study of recurrent colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 1979 Apr;189(4):496–502. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197904000-00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geoghegan J., Scheele J. Treatment of colorectal liver metastases. BJS. 1999 Jan 2;86(2):158–169. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galandiuk S., Wieand H.S., Moertel C.G., Cha S.S., Fitzgibbons R.J.J., Pemberton J.H. Patterns of recurrence after curative resection of carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992 Jan;174(1):27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Segelman J., Granath F., Holm T., Machado M., Mahteme H., Martling A. Incidence, prevalence and risk factors for peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2012 May;99(5):699–705. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koppe M.J., Boerman O.C., Oyen W.J.G., Bleichrodt R.P. Peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: incidence and current treatment strategies. Ann Surg. 2006 Feb;243(2):212–222. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197702.46394.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riihimäki M., Hemminki A., Sundquist J., Hemminki K. Patterns of metastasis in colon and rectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2016 Jul 15;6:29765. doi: 10.1038/srep29765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lech G., Słotwiński R., Słodkowski M., Krasnodębski I.W. Colorectal cancer tumour markers and biomarkers: recent therapeutic advances. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Feb 7;22(5):1745–1755. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i5.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Network T.C.G.A. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012 Jul 19;487(7407):330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lievre A., Bachet J.-B., Le Corre D., Boige V., Landi B., Emile J.-F. KRAS mutation status is predictive of response to cetuximab therapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2006 Apr;66(8):3992–3995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loupakis F., Ruzzo A., Cremolini C., Vincenzi B., Salvatore L., Santini D. KRAS codon 61, 146 and BRAF mutations predict resistance to cetuximab plus irinotecan in KRAS codon 12 and 13 wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009 Aug 18;101(4):715–721. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurwitz H.I., Tebbutt N.C., Kabbinavar F., Giantonio B.J., Guan Z.-Z., Mitchell L. Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer: pooled analysis from seven randomized controlled trials. Oncologist. 2013;18(9):1004–1012. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou M., Yu P., Qu J., Chen Y., Zhou Y., Fu L. Efficacy of bevacizumab in the first-line treatment of patients with RAS mutations metastatic colorectal cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;40(1–2):361–369. doi: 10.1159/000452551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorich M.J., Wiese M.D., Rowland A., Kichenadasse G., McKinnon R.A., Karapetis C.S. Extended RAS mutations and anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody survival benefit in metastatic colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2014 Jan;26(1):13–21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peeters M., Oliner K.S., Price T.J., Cervantes A., Sobrero A.F., Ducreux M. Analysis of KRAS/NRAS Mutations in a phase III study of panitumumab with FOLFIRI compared with FOLFIRI alone as second-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015 Dec;21(24):5469–5479. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies H., Bignell G.R., Cox C., Stephens P., Edkins S., Clegg S. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002 Jun;417(6892):949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaughn C.P., Zobell S.D., Furtado L.V., Baker C.L., Samowitz W.S. Frequency of KRAS, BRAF, and NRAS mutations in colorectal cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011 May;50(5):307–312. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maughan T.S., Adams R.A., Smith C.G., Meade A.M., Seymour M.T., Wilson R.H. Addition of cetuximab to oxaliplatin-based first-line combination chemotherapy for treatment of advanced colorectal cancer: results of the randomised phase 3 MRC COIN trial. Lancet (London, England) 2011 Jun;377(9783):2103–2114. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60613-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Roock W., De Vriendt V., Normanno N., Ciardiello F., Tejpar S. KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, and PTEN mutations: implications for targeted therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(6):594–603. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao C., Yang Z.Y., Hu X.F., Chen Q., Tang J.L. PIK3CA exon 20 mutations as a potential biomarker for resistance to anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies in KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2012 Jun;23(6):1518–1525. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loupakis F., Pollina L., Stasi I., Ruzzo A., Scartozzi M., Santini D. PTEN expression and KRAS mutations on primary tumors and metastases in the prediction of benefit from cetuximab plus irinotecan for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Jun;27(16):2622–2629. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laurent-Puig P., Cayre A., Manceau G., Buc E., Bachet J.-B., Lecomte T. Analysis of PTEN, BRAF, and EGFR status in determining benefit from cetuximab therapy in wild-type KRAS metastatic colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Dec;27(35):5924–5930. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fodde R. The APC gene in colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002 May;38(7):867–871. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molleví D.G., Serrano T., Ginestà M.M., Valls J., Torras J., Navarro M. Mutations in TP53 are a prognostic factor in colorectal hepatic metastases undergoing surgical resection. Carcinogenesis. 2007 Jun 1;28(6):1241–1246. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fariña Sarasqueta A., Forte G.I., Corver W.E., de Miranda N.F., Ruano D., van Eijk R. Integral analysis of p53 and its value as prognostic factor in sporadic colon cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(1):277. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westra J.L., Schaapveld M., Hollema H., de Boer J.P., Kraak M.M.J., de Jong D. Determination of TP53 mutation is more relevant than microsatellite instability status for the prediction of disease-free survival in adjuvant-treated stage III colon cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Aug;23(24):5635–5643. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russo A., Bazan V., Iacopetta B., Kerr D., Soussi T., Gebbia N. The TP53 colorectal cancer international collaborative study on the prognostic and predictive significance of p53 mutation: influence of tumor site, type of mutation, and adjuvant treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Oct;23(30):7518–7528. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyaki M., Iijima T., Konishi M., Sakai K., Ishii A., Yasuno M. Higher frequency of Smad4 gene mutation in human colorectal cancer with distant metastasis. Oncogene. 1999 May;18(20):3098–3103. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alazzouzi H., Alhopuro P., Salovaara R., Sammalkorpi H., Jarvinen H., Mecklin J.-P. SMAD4 as a prognostic marker in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005 Apr;11(7):2606–2611. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kozak M.M., von Eyben R., Pai J., Vossler S.R., Limaye M., Jayachandran P. Smad4 inactivation predicts for worse prognosis and response to fluorouracil-based treatment in colorectal cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2015 May;68(5):341–345. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siravegna G., Mussolin B., Buscarino M., Corti G., Cassingena A., Crisafulli G. Clonal evolution and resistance to EGFR blockade in the blood of colorectal cancer patients. Nat Med. 2015 Jul;21(7):795–801. doi: 10.1038/nm.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baas J.M., Krens L.L., Guchelaar H.-J., Morreau H., Gelderblom H. Concordance of predictive markers for EGFR inhibitors in primary tumors and metastases in colorectal cancer: a review. Oncologist. 2011 Sep 8;16(9):1239–1249. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mao C., Wu X.-Y., Yang Z.-Y., Threapleton D.E., Yuan J.-Q., Yu Y.-Y. Concordant analysis of KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutations, and PTEN expression between primary colorectal cancer and matched metastases. Sci Rep. 2015 Feb 2;5:8065. doi: 10.1038/srep08065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerlinger M., Rowan A.J., Horswell S., Math M., Larkin J., Endesfelder D. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012 Mar;366(10):883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group TP Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009 Jul 21;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freeman M.F., Tukey J.W. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat. 1950;21(4):607–611. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller J.J. The inverse of the freeman – Tukey double arcsine transformation. Am Stat. 1978 Nov 1;32(4):138. [Google Scholar]

- 41.DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986 Sep;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higgins J.P.T., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003 Sep;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Egger M., Smith G.D., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moorcraft S.Y., Jones T., Walker B.A., Ladas G., Kalaitzaki E., Yuan L. Molecular profiling of colorectal pulmonary metastases and primary tumours: implications for targeted treatment. Oncotarget. 2017 Sep 12;8(39):64999–65008. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujiyoshi K., Yamamoto G., Takahashi A., Arai Y., Yamada M., Kakuta M. High concordance rate of KRAS/BRAF mutations and MSI-H between primary colorectal cancer and corresponding metastases. Oncol Rep. 2017 Feb;37(2):785–792. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.5323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petaccia de Macedo M., Melo F.M., Ribeiro H.S.C., Marques M.C., Kagohara L.T., Begnami M.D. KRAS mutation status is highly homogeneous between areas of the primary tumor and the corresponding metastasis of colorectal adenocarcinomas: one less problem in patient care. Am J Cancer Res. 2017 Sep 1;7(9):1978–1989. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pang X.-L., Li Q.-X., Ma Z.-P., Shi Y., Ma Y.-Q., Li X.-X. Association between clinicopathological features and survival in patients with primary and paired metastatic colorectal cancer and KRAS mutation. Onco Targets Ther. 2017 May 19;10:2645–2654. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S133203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nemecek R., Berkovcova J., Radova L., Kazda T., Mlcochova J., Vychytilova-Faltejskova P. Mutational analysis of primary and metastatic colorectal cancer samples underlying the resistance to cetuximab-based therapy. Onco Targets Ther. 2016 Jul 28;9:4695–4703. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S102891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Z.-Z., Bai L., Wang F., Zhang Z.-C., Wang F., Zeng Z.-L. Comparison of KRAS mutation status between primary tumor and metastasis in Chinese colorectal cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2016 Jul;33(7):71. doi: 10.1007/s12032-016-0787-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He Q., Xu Q., Wu W., Chen L., Sun W., Ying J. Comparison of KRAS and PIK3CA gene status between primary tumors and paired metastases in colorectal cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2016 Apr 20;9:2329–2335. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S97668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kovaleva V., Geissler A.-L., Lutz L., Fritsch R., Makowiec F., Wiesemann S. Spatio-temporal mutation profiles of case-matched colorectal carcinomas and their metastases reveal unique de novo mutations in metachronous lung metastases by targeted next generation sequencing. Mol Cancer. 2016 Oct 18;15:63. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0549-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crumley S.M., Pepper K.L., Phan A.T., Olsen R.J., Schwartz M.R., Portier B.P. Next-generation sequencing of matched primary and metastatic rectal adenocarcinomas demonstrates minimal mutation gain and concordance to colonic adenocarcinomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016 Jun;140(6):529–535. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0261-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vignot S., Lefebvre C., Frampton G.M., Meurice G., Yelensky R., Palmer G. Comparative analysis of primary tumour and matched metastases in colorectal cancer patients: evaluation of concordance between genomic and transcriptional profiles. Eur J Cancer. 2015 May;51(7):791–799. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jesinghaus M., Wolf T., Pfarr N., Muckenhuber A., Ahadova A., Warth A. Distinctive spatiotemporal stability of somatic mutations in metastasized microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015 Aug;39(8):1140–1147. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siyar Ekinci A., Demirci U., Cakmak Oksuzoglu B., Ozturk A., Esbah O., Ozatli T. KRAS discordance between primary and metastatic tumor in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma. J BUON. 2015;20(1):128–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lau K.S., Lam K.O., Choy T.S., Shek W.H., Chung L.P., Leung T.W. Vol. 26. 2015. Discordant RAS Status Between Primary and Metastatic Colorectal Cancer and Predicted Pattern of Metastases. Annals of Oncology. [46 p] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee K.H., Kim J.S., Lee C.S., Kim J.Y. KRAS discordance between primary and recurrent tumors after radical resection of colorectal cancers. J Surg Oncol. 2015 Jun;111(8):1059–1064. doi: 10.1002/jso.23936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lim B., Mun J., Kim J.-H., Kim C.W., Roh S.A., Cho D.-H. Genome-wide mutation profiles of colorectal tumors and associated liver metastases at the exome and transcriptome levels. Oncotarget. 2015 Sep 8;6(26):22179–22190. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim R., Schell M.J., Teer J.K., Greenawalt D.M., Yang M., Yeatman T.J. co-evolution of somatic variation in primary and metastatic colorectal cancer may expand biopsy indications in the molecular era. PLoS One. 2015 May 14;10(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126670. Suzuki H, editor. e0126670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kleist B., Kempa M., Novy M., Oberkanins C., Xu L., Li G. Comparison of neuroendocrine differentiation and KRAS/NRAS/BRAF/PIK3CA/TP53 mutation status in primary and metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014 Aug 15;7(9):5927–5939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Giannini R., Lupi C., Loupakis F., Servadio A., Cremolini C., Sensi E. KRAS and BRAF genotyping of synchronous colorectal carcinomas. Oncol Lett. 2014 May 21;7(5):1532–1536. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.PALIOGIANNIS P., COSSU A., TANDA F., PALMIERI G., PALOMBA G. KRAS mutational concordance between primary and metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2014 Oct 4;8(4):1422–1426. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brannon A.R., Vakiani E., Sylvester B.E., Scott S.N., McDermott G., Shah R.H. Comparative sequencing analysis reveals high genomic concordance between matched primary and metastatic colorectal cancer lesions. Genome Biol. 2014 Aug 28;15(8):454. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0454-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee S.Y., Haq F., Kim D., Jun C., Jo H.-J., Ahn S.-M. Comparative genomic analysis of primary and synchronous metastatic colorectal cancers. PLoS One. 2014 Mar 5;9(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090459. Wikman H, editor. e90459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Murata A., Baba Y., Watanabe M., Shigaki H., Miyake K., Ishimoto T. Methylation levels of LINE-1 in primary lesion and matched metastatic lesions of colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013 Jul 23;109(2):408–415. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miglio U., Mezzapelle R., Paganotti A., Allegrini S., Veggiani C., Antona J. Mutation analysis of KRAS in primary colorectal cancer and matched metastases by means of highly sensitivity molecular assay. Pathol Res Pract. 2013 Apr;209(4):233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Voutsina A., Tzardi M., Kalikaki A., Zafeiriou Z., Papadimitraki E., Papadakis M. Combined analysis of KRAS and PIK3CA mutations, MET and PTEN expression in primary tumors and corresponding metastases in colorectal cancer. Mod Pathol. 2013 Aug 31;26:302. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vakiani E., Janakiraman M., Shen R., Sinha R., Zeng Z., Shia J. Comparative genomic analysis of primary versus metastatic colorectal carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Aug;30(24):2956–2962. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vermaat J.S., Nijman I.J., Koudijs M.J., Gerritse F.L., Scherer S.J., Mokry M. Primary colorectal cancers and their subsequent hepatic metastases are genetically different: implications for selection of patients for targeted treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2012 Feb;18(3):688–699. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Knijn N., Mekenkamp L.J.M., Klomp M., Vink-Borger M.E., Tol J., Teerenstra S. KRAS mutation analysis: a comparison between primary tumours and matched liver metastases in 305 colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2011 Mar;104(6):1020–1026. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Park J.H., Han S.-W., Oh D.-Y., Im S.-A., Jeong S.-Y., Park K.J. Analysis of KRAS, BRAF, PTEN, IGF1R, EGFR intron 1 CA status in both primary tumors and paired metastases in determining benefit from cetuximab therapy in colon cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;68(4):1045–1055. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1586-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Watanabe T., Kobunai T., Yamamoto Y., Matsuda K., Ishihara S., Nozawa K. Heterogeneity of KRAS status may explain the subset of discordant KRAS status between primary and metastatic colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011 Sep;54(9):1170–1178. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31821d37a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baldus S.E., Schaefer K.-L., Engers R., Hartleb D., Stoecklein N.H., Gabbert H.E. Prevalence and heterogeneity of KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA mutations in primary colorectal adenocarcinomas and their corresponding metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2010 Feb;16(3):790–799. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Italiano A., Hostein I., Soubeyran I., Fabas T., Benchimol D., Evrard S. KRAS and BRAF mutational status in primary colorectal tumors and related metastatic sites: biological and clinical implications. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010 May;17(5):1429–1434. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0864-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mariani P., Lae M., Degeorges A., Cacheux W., Lappartient E., Margogne A. Concordant analysis of KRAS status in primary colon carcinoma and matched metastasis. Anticancer Res. 2010 Oct;30(10):4229–4235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Perrone F., Lampis A., Orsenigo M., Di Bartolomeo M., Gevorgyan A., Losa M. PI3KCA/PTEN deregulation contributes to impaired responses to cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2009 Jan;20(1):84–90. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cejas P., Lopez-Gomez M., Aguayo C., Madero R., de Castro Carpeno J., Belda-Iniesta C. KRAS mutations in primary colorectal cancer tumors and related metastases: a potential role in prediction of lung metastasis. PLoS One. 2009 Dec;4(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Garm Spindler K.-L., Pallisgaard N., Rasmussen A.A., Lindebjerg J., Andersen R.F., Cruger D. The importance of KRAS mutations and EGF61A>G polymorphism to the effect of cetuximab and irinotecan in metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2009 May;20(5):879–884. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Molinari F., Martin V., Saletti P., De Dosso S., Spitale A., Camponovo A. Differing deregulation of EGFR and downstream proteins in primary colorectal cancer and related metastatic sites may be clinically relevant. Br J Cancer. 2009 Apr 7;100(7):1087–1094. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gattenlöhner S., Etschmann B., Kunzmann V., Thalheimer A., Hack M., Kleber G. Concordance of KRAS/BRAF mutation status in metastatic colorectal cancer before and after anti-EGFR therapy. J Oncol. 2009 Mar 10;2009:831626. doi: 10.1155/2009/831626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Etienne-Grimaldi M.-C., Formento J.-L., Francoual M., Francois E., Formento P., Renee N. K-Ras mutations and treatment outcome in colorectal cancer patients receiving exclusive fluoropyrimidine therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008 Aug;14(15):4830–4835. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Santini D., Loupakis F., Vincenzi B., Floriani I., Stasi I., Canestrari E. High concordance of KRAS status between primary colorectal tumors and related metastatic sites: implications for clinical practice. Oncologist. 2008 Dec;13(12):1270–1275. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Artale S., Sartore-Bianchi A., Veronese S.M., Gambi V., Sarnataro C.S., Gambacorta M. Mutations of KRAS and BRAF in primary and matched metastatic sites of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4217–4219. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7286. Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. United States. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gattenlohner S., Germer C., Muller-Hermelink H.-K. K-ras mutations and cetuximab in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;360:835. United States. [author reply 835–6] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Weber J.-C., Meyer N., Pencreach E., Schneider A., Guerin E., Neuville A. Allelotyping analyses of synchronous primary and metastasis CIN colon cancers identified different subtypes. Int J Cancer. 2007 Feb;120(3):524–532. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oliveira C., Velho S., Moutinho C., Ferreira A., Preto A., Domingo E. KRAS and BRAF oncogenic mutations in MSS colorectal carcinoma progression. Oncogene. 2007 Jan;26(1):158–163. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Albanese I., Scibetta A.G., Migliavacca M., Russo A., Bazan V., Tomasino R.M. Heterogeneity within and between primary colorectal carcinomas and matched metastases as revealed by analysis of Ki-ras and p53 mutations. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004 Dec;325(3):784–791. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zauber P., Sabbath-Solitare M., Marotta S.P., Bishop D.T. Molecular changes in the Ki-ras and APC genes in primary colorectal carcinoma and synchronous metastases compared with the findings in accompanying adenomas. Mol Pathol. 2003 Jun 17;56(3):137–140. doi: 10.1136/mp.56.3.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tortola S., Steinert R., Hantschick M., Peinado M.A., Gastinger I., Stosiek P. Discordance between K-ras mutations in bone marrow micrometastases and the primary tumor in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001 Jun;19(11):2837–2843. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Al-Mulla F., Going J.J., Sowden E.T., Winter A., Pickford I.R., Birnie G.D. Heterogeneity of mutant versus wild-type Ki-ras in primary and metastatic colorectal carcinomas, and association of codon-12 valine with early mortality. J Pathol. 1998 Jun;185(2):130–138. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199806)185:2<130::AID-PATH85>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Suchy B., Zietz C., Rabes H.M. K-ras point mutations in human colorectal carcinomas: relation to aneuploidy and metastasis. Int J Cancer. 1992 Aug;52(1):30–33. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Losi L., Benhattar J., Costa J. Stability of K-ras mutations throughout the natural history of human colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28A(6–7):1115–1120. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(92)90468-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Oudejans J.J., Slebos R.J., Zoetmulder F.A., Mooi W.J., Rodenhuis S. Differential activation of ras genes by point mutation in human colon cancer with metastases to either lung or liver. Int J Cancer. 1991 Dec;49(6):875–879. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910490613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Atreya C.E., Sangale Z., Xu N., Matli M.R., Tikishvili E., Welbourn W. PTEN expression is consistent in colorectal cancer primaries and metastases and associates with patient survival. Cancer Med. 2013 Aug;2(4):496–506. doi: 10.1002/cam4.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yarom N., Marginean C., Moyana T., Gorn-Hondermann I., Birnboim H.C., Marginean H. EGFR expression variance in paired colorectal cancer primary and metastatic tumors. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010 Sep;10(5):416–421. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.5.12610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Scartozzi M., Bearzi I., Berardi R., Mandolesi A., Fabris G., Cascinu S. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) status in primary colorectal tumors does not correlate with EGFR expression in related metastatic sites: implications for treatment with EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibodies. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Dec;22(23):4772–4778. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jung J., Kang Y., Lee Y.J., Kim E., Ahn B., Lee E. Comparison of the mismatch repair system between primary and metastatic colorectal cancers using immunohistochemistry. J Pathol Transl Med. 2017 Mar;51(2):129–136. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2016.12.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Haraldsdottir S., Roth R., Pearlman R., Hampel H., Arnold C.A., Frankel W.L. Mismatch repair deficiency concordance between primary colorectal cancer and corresponding metastasis. Familial Cancer. 2016;15(2):253–260. doi: 10.1007/s10689-015-9856-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cohen S.A., Yu M., Baker K., Redman M., Wu C., Heinzerling T.J. The CpG island methylator phenotype is concordant between primary colorectal carcinoma and matched distant metastases. Clin Epigenetics. 2017 May 2;9:46. doi: 10.1186/s13148-017-0347-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kleist B., Meurer T., Poetsch M. Mitochondrial DNA alteration in primary and metastatic colorectal cancer: different frequency and association with selected clinicopathological and molecular markers. Tumour Biol. 2017 Mar;39(3) doi: 10.1177/1010428317692246. 1010428317692246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Neerincx M., Sie D.L.S., van de Wiel M.A., van Grieken N.C.T., Burggraaf J.D., Dekker H. MiR expression profiles of paired primary colorectal cancer and metastases by next-generation sequencing. Oncogene. 2015 Oct 5;4(10) doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2015.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Balschun K., Haag J., Wenke A.-K., von Schönfels W., Schwarz N.T., Röcken C. KRAS, NRAS, PIK3CA Exon 20, and BRAF genotypes in synchronous and metachronous primary colorectal cancers: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. J Mol Diagn. 2011 Jul 22;13(4):436–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sutton P.A., Jithesh P.V., Jones R.P., Evans J.P., Vimalachandran D., Malik H.Z. Exome sequencing of synchronously resected primary colorectal tumours and colorectal liver metastases to inform oncosurgical management. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018 Jan;44(1):115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.10.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tan I., Malik S., Ramnarayanan K., McPherson J., Ho D., Suzuki Y. High-depth sequencing of over 750 genes supports linear progression of primary tumors and metastases in most patients with liver-limited metastatic colorectal cancer. Genome Biol. 2015;16 doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0589-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Marusyk A., Almendro V., Polyak K. Intra-tumour heterogeneity: a looking glass for cancer? Nat Rev Cancer. 2012 Apr 19;12:323. doi: 10.1038/nrc3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Losi L., Baisse B., Bouzourene H., Benhattar J. Evolution of intratumoral genetic heterogeneity during colorectal cancer progression. Carcinogenesis. 2005 May 1;26(5):916–922. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Franko J., Shi Q., Meyers J.P., Maughan T.S., Adams R.A., Seymour M.T. Prognosis of patients with peritoneal metastatic colorectal cancer given systemic therapy: an analysis of individual patient data from prospective randomised trials from the Analysis and Research in Cancers of the Digestive System (ARCAD) database. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):1709–1719. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Goswami R.S., Patel K.P., Singh R.R., Meric-Bernstam F., Kopetz E.S., Subbiah V. Hotspot mutation panel testing reveals clonal evolution in a study of 265 paired primary and metastatic tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2015 Jun 1;21(11):2644–2651. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hammond W.A., Swaika A., Mody K. Pharmacologic resistance in colorectal cancer: a review. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2016 Jan;8(1):57–84. doi: 10.1177/1758834015614530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]