Abstract

The purpose of this study was to (1) provide data on maximal sprinting speed (MSS) and maximal acceleration (Amax) in elite rugby sevens players measured with GPS devices, (2) test the concurrent validity of the signal derived from a radar device and a commercially available 16 Hz GPS device, and (2) assess the between-device reliability of MSS and Amax of the same GPS. Fifteen elite rugby sevens players (90 ± 12 kg; 181 ± 8 cm; 26 ± 5 y) participated in the maximal sprinting test. A subset of five players participated in the concurrent validity and between-devices reliability study. A concurrent validity protocol compared the GPS units and a radar device (Stalker ATS II). The between-device reliability of the GPS signal during maximal sprint running was also assessed using 6 V2 GPS units (Sensorevery-where, Digital Simulation, Paris, France) attached to a custom-made steel sled and pushed by the five athletes who performed a combined total of 15 linear 40m sprints. CV ranged from 0.5, ±0.1 % for MSS and smoothed MSS to 6.4, ±1.1 % for Amax. TEM was trivial for MSS and smoothed MSS (0.09, ±0.01) and small for Amax and smoothed Amax (0.54, ±0.09 and 0.39, ±0.06 respectively). Mean bias ranged from -1.6, ±1.0 % to -3.0, ±1.1 % for smoothed MSS and MSS respectively. TEE were small (2.0, ±0.55 to 1.6, ±0.4 %, for MSS and smoothed MSS respectively. The main results indicate that the GPS units were highly reliable for assessing MSS and provided acceptable signal to noise ratio for measuring Amax, especially when a smoothing 0.5-s moving average is used. This 16 Hz GPS device provides sport scientists and coaches with an accurate and reliable means to monitor running performance in elite rugby sevens.

Keywords: Sprint assessment, Reliability, Validity, Global positioning system, Elite rugby sevens

INTRODUCTION

In rugby union generally, sprinting is a major component of physical performance and is related to key match outcomes such as line breaks and tackle effectiveness [1]. In younger age categories, sprint performance is also reported to be a key predictor of future elite players’ career [2]. As such, the profiling of sprint performance in rugby players is systematically performed in development squad and senior elite rugby team programs [3, 4]. The competitive physical demands in rugby sevens competition differ greatly to the 15-a-side format. In sevens match-play, players cover a greater total distance per min as well as a higher proportion of this distance at high velocities [5]. Maximal sprinting speed and acceleration are therefore key qualities targeted in physical conditioning programs for rugby Sevens players [6]. To our knowledge however, little information exists on performance in these variables in elite rugby sevens players.

In contemporary field assessments of sprint performance, investigators frequently employ dual-beamed photocells or radar devices [7]. While these systems ensure accurate and practical measurements [7], they only permit testing of a single player at a time. In elite team sport contexts, the time allocated to testing and training is frequently short due to intensive competitive schedules. Thus, time effective and simple practices to evaluate performance must be developed. Accordingly, Global positioning system (GPS) devices have become a key tool in field sport monitoring. Numerous studies have investigated their validity and reliability in various contexts [7, 8] in order to establish proof of concept for analyzing team sport performance. Although acceptable accuracy and reliability of GPS for measuring total running distance were reported in these studies, the devices were not considered sufficiently valid to enable accurate assessments of peak velocity during sprinting actions. The literature suggests that GPS with a higher frequency rate provide greater validity for the measurement of distance and speed [9]. Recently, some brands have increased sampling rates of their units from 5-10 Hz to 16-20 Hz, providing a promising alternative means to assess sprint performance in team sport players. Quality control assessments of such devices is nevertheless essential.

Thus, the purposes of this study in elite rugby sevens players were to (1) provide data on maximal sprinting speed and maximal acceleration of players derived from a new commercial GPS device, (2) test the concurrent validity of the maximal velocity derived from a radar device and the 16 Hz GPS unit and, (3) assess the between-device reliability of maximal sprinting speed and maximal acceleration measured using the 16 Hz GPS unit in relation to elite rugby sevens performance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Fifteen elite rugby sevens players (90 ± 12 kg; 181 ± 8 cm; 26 ± 5 y) participated in the maximal sprinting test. A subset of five players participated in the concurrent validity study. The data arose as a condition of elite player monitoring in which player activities are routinely monitored over the course of the competitive season. Nevertheless, local institution ethics clearance was obtained, and this study conformed to the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent of all participants was obtained prior to the beginning of the study. To ensure confidentiality, all performance data were anonymized.

Design

First, maximal sprint testing was performed to determine maximal acceleration and maximal velocity in this population to calculate the smallest worthwhile change in an elite rugby sevens population. Second, concurrent validity of maximal velocity data derived from the GPS units was assessed against velocity curves recorded using the radar device in a subset of 5 players who performed 25 maximal sprints. Finally, a between-devices reliability protocol was conducted to assess the reliability of maximal acceleration and maximal velocity measured derived from the GPS signal during maximal sprint running.

Maximal sprint testing

15 players performed 2 sprints over 40 m interspersed by 5-min of passive recovery on an artificial outdoor pitch. After preliminary testing, the distance was chosen to allow all players to reach their maximal speed in the sprint [10]. Prior to testing, subjects performed a 15-minute dynamic warm-up consisting of foam rolling, active mobility, progressive lower-body loading with squats and lunges, running drills such as wall drills, skipping, and single leg bounces and finish with 2 progressive sprints. Participants wore the GPS unit (Sensoreverywhere V2 GPS units, Digital simulation, Paris, France) in a specific designed lycra vest which positioned the device on the upper thoracic spine between the scapulae.

Players began each sprint from a standing static position start and were instructed to sprint as fast as possible over the 40 m distance. The best performance (lowest time) was used in the analysis.

Concurrent validity

A concurrent validity protocol was conducted to compare the 16 Hz GPS units with a radar device (Stalker ATS II, Stalker Sports Radar, Plano, TX, 48 Hz). A perfect correlation has been observed between speed recorded with a Stalker ATS radar devices and photocells [7]. Regarding test-retest reliability, ICC values ranging between 0.96-0.99, TE of 0.05 m · s-1 and CV comprised between 0.7-1.9% have been reported [7].

In this protocol, GPS and the radar device concomitantly measured running speed in a subset of five players who performed five 40-m sprints each (total: 25 trials), separately. Analysis of the signal derived from the GPS units was of interest in this part of the protocol and not player performance. Hence only a subset of players was used for the concurrent validity protocol. All the sprints were performed on an artificial rugby field following the same specific warm-up used in the maximal sprint testing assessment. The radar device was fixed up on a tripod approximately 5-m behind the starting line and 1 m above the ground, which corresponds approximately to the height of players’ center of mass. Participants wore the GPS in the same vest used in the maximal sprint testing assessment.

The concurrent validity of maxA recorded with the GPS and radar devices was not assessed due to technical constraints. Indeed, when using radar, the position targeted by a radar is usually the lumbar spine and the non-negligible variation of the position of the lumbar spine within the first few steps leads to discrepancies in velocity recorded using a GPS [11].

Between-device reliability

Six V2 GPS units (Digital simulation, Paris, France) were attached to a custom-made steel sled in which the units could be vertically aligned with 15 cm between them. This was pushed by the subset of 5 players who performed a total of 15 linear 40-m sprints (n=75 files).

During the sessions, the mean number of satellites per unit was 10±1 and average horizontal dilution was 1.56±0.07.

Data processing

The processing of all measurements was performed by the same operator using the same computational process. For each sprint, instantaneous raw running speed data recorded by the GPS and the radar device were extracted from the respective software (Sensoreverywhere Analyser, Digital Simulation, France and Stalker ATS 5.0, Stalker Sports Radar, USA for GPS and radar respectively). Raw velocity from the GPS was obtained using the Doppler-Shift method which demonstrates a higher level of precision and lower error compared with velocity measured via positional differentiation [12]. Maximal velocity (maxVraw, m · s-1) and maximal acceleration (maxAraw; m · s-2) were subsequently assessed from the raw signal. As providers usually filter the signal using a moving average to smooth the signal (0.2-0.3 second rolling average, [12]), we decided to use the 0.5-s moving average originally employed by the Sensoreverywhere Analyser software to smooth both the GPS and radar device signals. Consequently, maxVsmooth and maxAsmooth were recalculated from the filtered signal.

For the between-device reliability study, the start of the sprint was defined when the initial speed had risen above the mean + 2SD of the standing-still preparation period (mean: 0 m · s-1, SD: ~0.1 m · s-1) and this time was used to synchronize all GPS signals.

Statistical analysis

Data in the figures are presented as means with 90% confidence intervals (CI). All data were first log transformed to reduce bias arising from non-uniformity error. For the sake of clarity however, values presented in the text and figures are nontransformed (ie, back-transformed). Smallest worthwhile change (SWC) was calculated by multiplying the between-subject standard deviation (SD) of the performance by 0.2 (SWC, 0.2* between-subject SD). Between-device reliability was expressed as typical error of measurement (TE; absolute in m · s-1 or m · s-2 or standardized) and as coefficient of variation (CV; %). Intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC (1,1) = (SD2 – sd2/SD2) where SD is the between-subject standard deviation and sd is the within-subject standard deviation) were also calculated to provide a measure of between-device reliability.

Least squares linear regression was conducted to establish the agreement between the criterion (radar device) and the practical measure (GPS). Typical error of the estimate (TEE) and bias with respective 90% confidence intervals were calculated to provide measures of agreement between the criterion and practical measures.

Threshold values for standardized typical error were >0.2 (small), >0.6 (moderate), >1.2 (large) and very large (>2) [13].

The ‘usefulness’ of the test variables was assessed by comparing their noise (TE) to the SWC. The variable was considered as good when the TE was below the SWC, as OK when TE was similar to the SWC and as marginal when TE was higher than the SWC [14].

All the statistical procedures were computed in an Excel spreadsheet designed by Hopkins [15].

RESULTS

Maximal velocity testing

The mean value for maximal velocity of the rugby sevens players was 9.2±0.4 m · s-1 and 4.6±0.5 m · s-2 for maximal acceleration. Respective SWC for these variables were 1.3% (0.12 m · s-1) for maxV and 2.9% (0.12 m · s-2) for maxA (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Maximal sprinting speed (MSS) and acceleration (Acc max) in elite rugby sevens players derived using a 16 Hz Global positioning system.

| Performance | CV (%) | SWC (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSS (m.s-1) | 9.2±0.4 | 4.4% | 0.9% |

| Smoothed MSS (m.s-1) | 9.1±0.4 | 4.4% | 0.9% |

| Acc max (m.s-2) | 4.6±0.5 | 9.8% | 2.0% |

| Smoothed Acc (m.s-2) | 4.3±0.4 | 9.3% | 1.9% |

CV: coefficient of variation; SWC: Smallest worthwhile change; MSS: Maximal sprinting speed; Acc max: maximal acceleration.

Concurrent validity of maximal velocity

The concurrent validity data for maxVraw and maxVsmooth are presented in table 2. Mean bias ranged from -3.0, ±1.1 % to -1.6, ±1.0 % for maxVraw and maxVsmooth respectively with the GPS devices underestimating MSS. TEE were small (2.0, ±0.55 to 1.6, ±0.4% for maxVraw and maxVsmooth respectively).

TABLE 2.

Overall bias, typical error of measurement and 95% limits of agreement for maximal sprinting speed (MSS) comparisons between a 16 Hz Global positioning system and radar device.

| observed values |

Overall bias (%) | TEE (%) | 95% LOA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (unit) | 16 Hz GPS | Radar | |||

| MSS (m · s-1) | 8.11 ± 0.39 | 8.37 ± 0.26 | -3.00, ±1.11 | 2.03, ±0.55 | 1.07 |

| smoothed MSS (m · s-1) | 8.09 ± 0,38 | 8.22 ± 0.23 | -1.61, ±1.06 | 1.59, ±0.42 | 1.06 |

TEE: Typical error of estimate; LOA: Limit of agreement; MSS: Maximal sprinting speed.

Between-device reliability

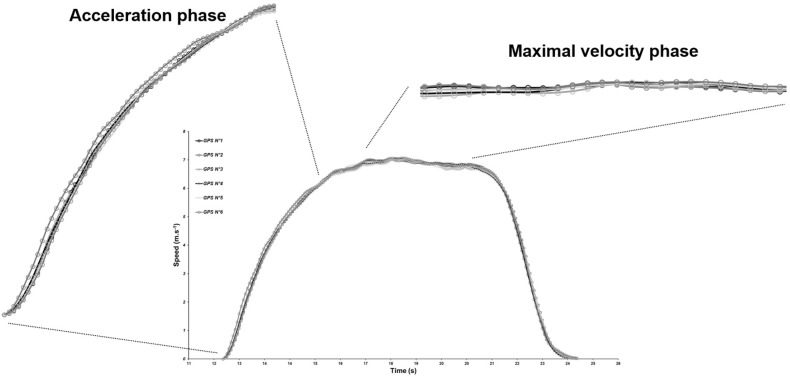

Reliability data for all the variables assessed are presented in table 3. CV ranged from 0.5, ±0.1 % for maxVraw and maxVsmooth to 6.4, ±1.1 % for maxAsmooth. TE was trivial for maxVraw and maxVsmooth (0.09,±0.01) and small for maxAraw and maxAsmooth (0.54, ±0.09 and 0.39, ±0.06 respectively). Figure 1 presents the synchronized overall speed-time curves obtained from the six GPS units during a representative sprint.

TABLE 3.

Reliability data for maximal sprinting speed (MSS) and maximal acceleration (Amax) measured using a 16 Hz Global positioning system.

| MSS (m · s-1) | smoothed MSS (m · s-1) | Accmax (m · s-2) | Smoothed Acc (m · s-2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical error as a CV (%) | 0.5, ±0.1 | 0.5, ±0.1 | 6.4, ±1.1 | 3.9, ±0.6 |

| Typical error (standardised) | 0.09, ±0.01 | 0.09, ±0.01 | 0.54, ±0.09 | 0.39, ±0.06 |

| Typical error (absolute) | 0.03, ±0.01 | 0.03, ±0.01 | 0.25, ±0.04 | 0.14, ±0.02 |

| Intraclass correlation | 0.99, ±0.0 | 0.99, ±0.0 | 0.74, ±0.14 | 0.87, ±0.08 |

CV: coefficient of variation; TE: Typical error; MSS: Maximal sprinting speed; Acc max: maximal acceleration.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of six typical signals derived from 16 Hz Global Positioning system units during a maximal sprint test.

DISCUSSION

This technical report assessed two main variables of sprint performance (maxV and maxA) in elite rugby sevens players. It also investigated the concurrent validity and between-device reliability of a commercially available 16 Hz GPS unit for assessing the two aforementioned variables of sprint performance. Results indicate that the GPS is a highly reliable device for assessment of maxV and provides acceptable between-device reliability for measurement of maxA, especially when a smoothing 0.5-s moving average is used and several trials are performed. However, small TEE and bias were measured between the radar and GPS units for maxV highlighting that caution is needed when comparing data between the two systems.

The present study is the first to report data on maxV and maxA in elite rugby sevens players. Our results for MSS (~9.1 ± 0.4 m · s-1) accord with those reported in Ross et al. [5] who investigated elite New-Zealand rugby sevens players. Indeed, in this latter study, players were able to perform a 10-m sprint in 1.68 ± 0.05 and 40-m in 4.99 ± 0.11 s resulting in a mean speed of 9.06 m · s-1 between 10 and 40-m. Positively, the SWC for the present elite rugby sevens players is similar than the generic SWC reported for team sport players (~1 to 2%) [7].

The relative bias for maxV measurement was low (-1.6 to -3.0%) and the correlations obtained between maxV derived from GPS and the radar were high for the smoothed maxVsmooth (TEE: 1.6, ±0.4; 95% limits of agreement: ±1.06). These results were similar to those observed in a comparison between 20 Hz GPS units and the same radar system used in the present study [16]. This result confirms that high sampling rate GPS devices (> 15 Hz) demonstrate satisfactory accuracy for measurements of maxV in team sport players on the field. However, it is worth noting that SWC for MSS measurement in the present population was ~1%. As such, using radar and GPS devices interchangeably (TEE: 1.6 to 2.0%) could lead to unclear results.

The comparison of maxV and maxA obtained simultaneously from 6 units attached to the same sled showed trivial to small between-unit variations (CV: 0.5% and 6.4% respectively). These between-unit variations were in the lower range of those previously reported in the literature [17]. It is noteworthy that between-unit variations could be further improved by using a 0.5-s rolling average to smooth the data, especially for maxA (CV: 6.4 vs 3.9%; TE: 0.54 vs 0.33 m · s-2 for maxAraw and maxAsmooth respectively) and thus, acceptable signal to noise ratios can be obtained. A reasonable suggestion is the lower variability for both maxV and maxA observed in this study may be related to the increased sample rate of the present GPS units (> 15 Hz vs 5-10 Hz habitually). Accordingly, measurements of maxV (CV: 0.5%) and to a lesser extent maxA (CV: 3.9%) performance could be performed more frequently in elite team sport settings.

It is important to note that TE for maxA was higher than the SWC which reduces the ability of GPS to detect small changes in maximal acceleration, for example, following a training period or when players have decreased readiness to train. When the TE is much larger than the SWC, repeated trials can be used to decrease the TE and in turn increase the signal-to-noise ratio (TE decrease by a factor of repetition; [7]). As there is no fatigue occurrence during repeated short distance sprint testing [18], maxA testing could be repeated multiple times to provide a more reliable measure of the true maximal acceleration capacity of the players. Three repetitions might be enough to decrease the TE from 3.9 to 2.3, and in turn, obtain a TE < SWC.

Practical applications:

While MSS measured by a commercial 16 Hz GPS unit is accurate, GPS and radar should not be used interchangeably.

Reliability of maxV and maxA measured with GPS units could be improved by using a 0.5-s moving average smoothing function.

maxV measurement using GPS devices is reliable and could be a practically useful means to assess meaningful changes in performance (>TE+SWC = 1.8%) in a team sport setup.

maxA measurement might be repeated multiple times (e.g. 3 repetitions) with sufficient recovery time (~3-min) to increase the signal-to-noise ratio and thus, the ability to detect true changes in performance.

CONCLUSIONS

To conclude, our study has demonstrated that a new commercially available GPS with increased sampling rate (> 15 Hz vs 5-10 Hz previously) was sufficiently reliable to measure maxV and to a lesser extend maxA in team sport. While maxV is accurately assessed by GPS devices, values assessed with GPS devices and radar should not be used interchangeably. These latest GPS devices offer fresh possibilities for sport scientists and coaches to track performance and readiness to perform in team sports where large squad and low available time require effective and simple monitoring processes.

Conflict of interest

Authors do not have any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smart D, Hopkins WG, Quarrie KL, Gill N. The relationship between physical fitness and game behaviours in rugby union players. Eur J Sport Sci. 2014;14(Suppl 1):S8–17. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2011.635812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontana FY, Colosio AL, Da Lozzo G, Pogliaghi S. Player’s success prediction in rugby union: From youth performance to senior level placing. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20:409–14.3. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barr MJ, Sheppard JM, Gabbett TJ, Newton RU. Long-term training-induced changes in sprinting speed and sprint momentum in elite rugby union players. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28:2724–31. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darrall-Jones JD, Jones B, Till K. Anthropometric and Physical Profiles of English Academy Rugby Union Players. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29:2086–96. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross A, Gill N, Cronin J. Match analysis and player characteristics in rugby sevens. Sports Med. 2014;44:357–67. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuster J, Howells D, Robineau J, Couderc A, Natera A, Lumley N, Gabbett TJ, Winkelman N. Physical Preparation Recommendations for Elite Rugby Sevens Performance. Int J Sports Phys Perf. 2017;13(3):255–67. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2016-0728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haugen T, Buchheit M. Sprint Running Performance Monitoring: Methodological and Practical Considerations. Sports Med. 2016;46:641–56. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0446-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varley MC, Fairweather IH, Aughey RJ. Validity and reliability of GPS for measuring instantaneous velocity during acceleration, deceleration, and constant motion. J Sports Sci. 2012;30:121–27. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2011.627941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cummins C, Orr R, O’Connor H, West C. Global positioning systems (GPS) and microtechnology sensors in team sports: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2013;43(10):1025–42. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marrier B, Le Meur Y, Robineau J, Lacome M, Couderc A, Hausswirth C, Piscione J, Morin JB. Quantifying Neuromuscular Fatigue Induced by an Intense Training Session in Rugby Sevens. Int J Sports Phys Perf. 2016;12(2):218–23. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2016-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bezodis NE, Salo AI, Trewartha G. Measurement error in estimates of sprint velocity from a laser displacement measurement device. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33:439–44. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1301313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malone JJ, Lovell R, Varley MC, Coutts AJ. Unpacking the Black Box: Applications and Considerations for Using GPS Devices in Sport. Int J Sports Phys Perf. 2017;12(Suppl 2):S218–s26. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2016-0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopkins WG, Marshall SW, Batterham AM, Hanin J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:3–13. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cb278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchheit M, Lefebvre B, Laursen PB, Ahmaidi S. Reliability, usefulness, and validity of the 30-15 Intermittent Ice Test in young elite ice hockey players. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25:1457–64. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d686b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopkins WG. Spreadsheets for analysis of validity and reliability. Sportscience. 2015;19:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagahara R, Botter A, Rejc E, Koido M, Shimizu T, Samozino P, Morin JB. Concurrent Validity of GPS for Deriving Mechanical Properties of Sprint Acceleration. Int J Sports Phys Perf. 2017;12:129–32.17. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2015-0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchheit M, Al Haddad H, Simpson BM, Palazzi D, Bourdon PC, Di Salvo V, Mendez-Villanueva A. Monitoring accelerations with GPS in football: time to slow down? Int J Sports Phys Perf. 2014;9:442–45. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2013-0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haugen T, Tonnessen E, Oksenholt O, Haugen FL, Paulsen G, Enoksen E, Seiler S. Sprint conditioning of junior soccer players: effects of training intensity and technique supervision. PloS one. 2015;10:e0121827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]