Abstract

Introduction:

Basal ganglia stroke following trauma has been known to occur and described in previous case studies. But exact etiology is unknown.

Aim:

To study the clinical characteristics, imaging features, and neurodevelopmental outcomes of children presented with basal ganglia stroke associated with mineralization in the lenticulostriate arteries in our center from January 2013 to June 2016.

Subjects and Methods:

Children with subcortical stroke during the study period were identified retrospectively, and those presented with basal ganglia stroke with mineralization of lenticulostriate vessels were analyzed for clinical profile, imaging features, and outcomes. Statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 17 (IBM, New York).

Results:

Of 38 children with basal ganglia stroke (20 boys, 18 girls, and mean age at presentation 14.026±5.8470 months), 27 had history of trauma preceding the stroke. Thirty-seven children presented with hemiparesis and one presented with hemidystonia. The mean follow-up time was 8 months, three children developed recurrence during that period. Five children with recurrence of stroke, initial episodes were not evaluated as they presented to us for the first time. A total of 17 of 30 infants who did not have stroke recurrence were normal on follow-up, whereas 9 infants showed persistent mild hemiparesis, 2 had motor delay, and 2 others had mild residual distal weakness. No identifiable causes were observed for vascular calcification. Two familial cases were also noted.

Conclusion:

Most common cause for acute basal ganglia stroke in toddlers was mineralizing angiopathy of lenticulostriate vessels. It was preceded by minor trauma in most cases.

KEYWORDS: Basal ganglia stroke, lenticulostriate vessels, mineralizing angiopathy, trauma, toddler

INTRODUCTION

Basal ganglia stroke following trivial trauma has been described in several case reports over last decades,[1,2,3,4,5] but the exact etiopathogenic factors were not known. In a study by Yang et al.,[6] basal ganglia calcification and cytomegalovirus infection were the major risk factors associated with cerebral infarction following mild head trauma in infants. Recently, Lingappa et al.[7] described a distinct clinicoradiological entity of mineralizing angiopathy in children with acute basal ganglia stroke. In this study, we analyzed clinical characteristics, imaging features, and outcome of 38 children with basal ganglia stroke associated with mineralization in the lenticulostriate arteries.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The study was conducted at a pediatric neurology clinic attached to a tertiary care center from south India. Consecutive children with basal ganglia stroke and mineralization of lenticulostriate arteries were selected from the neurology unit databases. Participants were identified retrospectively from January 2013 to June 2016, and follow-up period was up to December 2016. The hospital ethics committee clearance was obtained. All children with subcortical stroke who presented at the pediatric neurology unit during this period were included. The study group was formed by children with mineralization in the distribution of the lenticulostriate arteries and basal ganglia infarcts. Their age, sex, demography, history of onset, history of trauma/fall, time lag between fall and weakness, and neurological symptoms and signs were noted. Documentation was carried out on the history of developmental milestones, family history, as well as history of similar episodes in the past. Treatment response, neurodevelopmental outcome, and recurrence of stroke were documented during follow-up period.

The details of physical examination, systemic examination, organomegaly, and anthropometry were documented. Plain computed tomography (CT) of brain with axial and coronal sections was carried out in all infants. Complete blood count, sickling test, renal function test, liver function test, serum electrolytes, lipid profile, serum homocysteine, serum lactate, echocardiography, retroviral serology, serum calcium, serum phosphorous and serum alkaline phosphatase, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time were performed in all cases. TORCH screen (toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex, and human immunodeficiency virus) and eye examination were conducted in suspected cases of intrauterine infection. Serum parathyroid hormone level, serum and cerebrospinal fluid lactate levels, and procoagulant workup (protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III) were carried out in unilateral involvement and with no history of fall. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) were performed only in selected children who presented with severe weakness and with unilateral calcification in CT of brain.

The treatment was started with aspirin (3 to 3–5mg/kg) in all children. All the infants underwent rehabilitation therapy. The statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 17 (IBM, New York).

RESULTS

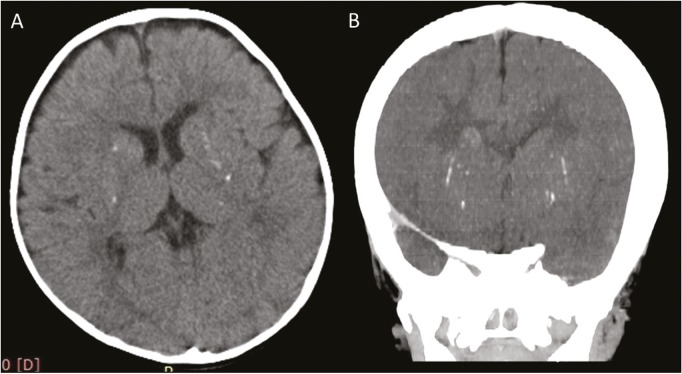

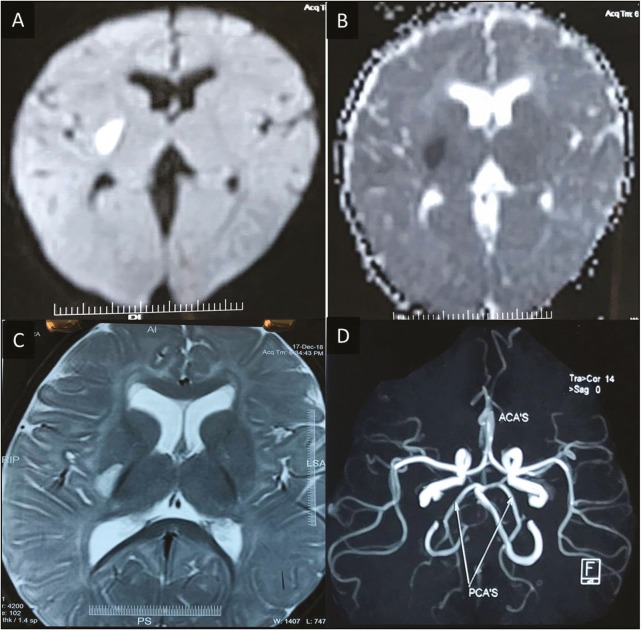

During the study period, a total of 125 children who had arterial ischemic stroke were observed. Of this, 80 had cortical stroke without parenchymal mineralization and 45 infants with subcortical infarcts were noted. In the subcortical infarct category, seven cases were due to neuroinfection, and they did not show any mineralization of lenticulostriate arteries. The remaining 38 infants formed the study group. This group had basal ganglia ischemic stroke and mineralization of the lenticulostriate arteries, which were detected on CT scan. Figure 1A and B shows punctate microcalcifications in bilateral basal ganglia. In MRI of brain, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) of MRI [Figure 2A] and corresponding apparent diffusion coefficient mapping [Figure 2B] show diffusion restriction in right posterior putamen, axial T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) [Figure 2C] shows hyperintensity in right posterior putamen without occlusion in the vessels [Figure 2D]. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the demographic profile, clinical, radiological characteristics, and neurodevelopmental outcomes of the study group.

Figure 1.

Axial (A) and coronal CT (B) scan shows presence of punctate microcalcifications in bilateral basal ganglia

Figure 2.

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) of MRI (A) and corresponding apparent diffusion coefficient mapping (B) show diffusion restriction in right posterior putamen. Axial T2-weighted imaging (C) shows hyperintensity in right posterior putamen. MRA shows no occlusion in the vessels (D)

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients (n = 38)

| Characteristic | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Mean age at presentation (months) | 14.026 |

| Age at presentation (SD) | 5.8470 |

| Male, female | 20, 18 |

| History of fall | 27/38 |

| Time lag between fall and development of symptoms (n = 27) | |

| Immediate | 8/27 |

| 10 min to 8 h | 13/27 |

| >48 h | 6/27 |

| Presenting complaints | |

| Hemiparesis | 37/38 |

| Hemidystonia | 1/38 |

| Neurological manifestations | |

| Hemiparesis | 38/38 |

| Hemidystonia | 28/38 |

| Dysarthria and speech delay | 4/38 |

| Mild encephalopathy | 3/38 |

Table 2.

Clinical and radiological features of participants

| Patient no. | Sex | Age (months) | History of fall? | Time lag (min)a | Acute dystonia | Mineralization (right, left)b | Neurodevelopmental outcome | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 12 | Yes | 30 | Yes | 2, 2 | Mild hemiparesis | 6 |

| 2 | M | 14 | Yes | 30 | Yes | 3, 2 | Normal | 6 |

| 3 | F | 9 | No | - | Yes | 4, 1 | Normal | 6 |

| 4 | M | 6 | Yes | Immediate | Yes | 3, 3 | Residual dysarthria and hemiparesis | 16 |

| 5 | M | 12 | No | - | Yes | 2, 2 | Normal | 6 |

| 6 | F | 16 | No | - | Yes | 1, 1 | Normal | 6 |

| 7 | M | 18 | Yes | 48 h | No | 2, 3 | Normal | 6 |

| 8 | F | 20 | Yes | 30 | Yes | 2, 3 | Mild residual hemiparesis | 16 |

| 9 | F | 22 | Yes | 60 | No | 2, 2 | Normal | 6 |

| 10 | F | 15 | Yes | Immediate | Yes | 1, 1 | Normal | 6 |

| 11 | M | 18 | Yes | 48 h | Yes | 3, 4 | Motor delay | 6 |

| 12 | F | 14 | Yes | 30 | No | 3, 3 | Mild residual hemiparesis | 16 |

| 13 | M | 12 | No | - | Yes | 1, 1 | Normal | 6 |

| 14 | M | 8 | Yes | 15 | No | 1, 2 | Mild distal upper limb weakness | 6 |

| 15 | M | 9 | No | - | No | 2, 3 | Mild residual hemiparesis | 8 |

| 16 | F | 16 | No | - | No | 3, 4 | Normal | 6 |

| 17 | M | 14 | Yes | 30 | No | 2, 3 | Normal | 6 |

| 18 | M | 12 | Yes | 30 | Yes | 5, 3 | Mild residual hemiparesis | 19 |

| 19 | F | 13 | No | - | Yes | 1, 1 | Mild residual hemiparesis | 6 |

| 20 | M | 12 | No | - | No | 2, 2 | Mild residual hemiparesis | 6 |

| 21 | F | 22 | Yes | 48 h | Yes | 3, 2 | Normal | 6 |

| 22 | M | 15 | Yes | 30 | Yes | 3, 3 | Normal | 6 |

| 23 | F | 6 | No | - | Yes | 4, 3 | Speech delay and motor delay with residual hemiparesis | 22 |

| 24 | F | 7 | Yes | Immediate | No | 4, 1 | Normal | 6 |

| 25 | F | 14 | Yes | 30 | Yes | 5, 3 | Normal | 6 |

| 26 | M | 12 | Yes | Immediate | Yes | 2, 2 | Normal | 6 |

| 27 | F | 15 | Yes | 30 | Yes | 1, 1 | Mild distal upper limb weakness with dysarthria | 6 |

| 28 | F | 13 | Yes | 10 | No | 1, 2 | Motor delay | 6 |

| 29 | M | 6 | No | - | Yes | 3, 3 | Normal | 6 |

| 30 | M | 9 | No | - | Yes | 2, 1 | Normal | 6 |

| 31 | F | 12 | Yes | 15 | Yes | 1, 1 | Speech delay and motor delay with residual hemiparesis | 14 |

| 32 | M | 18 | Yes | 48 h | Yes | 2, 2 | Speech delay and motor delay with residual hemiparesis | 18 |

| 33 | M | 13 | Yes | Immediate | No | 3, 2 | Residual hemiparesis | 6 |

| 34 | M | 19 | Yes | Immediate | Yes | 1, 2 | Residual hemiparesis | 6 |

| 35 | F | 24 | Yes | Immediate | Yes | 2, 2 | Residual hemiparesis | 6 |

| 36 | F | 7 | Yes | Immediate | Yes | 2, 2 | Residual hemiparesis | 6 |

| 37 | F | 36 | Yes | 48 h | Yes | 2, 2 | Residual hemiparesis | 6 |

| 38 | M | 13 | Yes | 48 h | Yes | 2, 2 | Residual hemiparesis | 6 |

aTime lag between fall and onset of symptoms, bNumber of mineralized lenticulostriate arteries seen using computed tomography at first presentation on right and left side

Of a total of 38, the age of 16 infants was less than or equal to 1 year. Of the 27 infants who had history of trauma, the event was caused by rolling over from a higher to a lower surface (from bed to ground) (n = 12) and falling while attempting to stand or walk (n = 15). In eight of the infants, the onset of neurological symptoms was immediate. In six infants, the neurological symptoms manifested after 48h of trauma. In 13 other children, the onset of neurological symptoms occurred between 10min and 8h after the fall. None experienced loss of consciousness or seizures after fall. Hemidystonia was noted in 28 cases on the affected side with onset between 24 and 72h after the fall subsiding within 24h. Electroencephalogram recording performed during these brief moments of hemidystonia lasting for few seconds was normal. Only one had recurrent hemidystonia, which presented after 48h of the fall.

CT of brain showed typical sharply marginated, linear hyperdense lesions emerging vertically through the inferior part of the lentiform nucleus in all the infants. On coronal and sagittal views, the distributions of these linear lesions were similar to that described in anatomical literature about lenticulostriate arteries. These lesions had attenuation values between 58 and 90 HU representing mineralization. The number of mineralized arteries varied from one to five on each side. The infarct was situated on one of the mineralization arteries.

Other etiological factors were ruled out. Ophthalmological examination, serum calcium, phosphorous, and alkaline phosphatase levels, and retroviral serology were normal in all cases.

Eight of the 38 infants experienced recurrent strokes [Table 3]. In five of the infants, there were lesions in bilateral basal ganglia, one side showing gliosis and other side was an acute infarct indicating that the first stroke was unnoticed. Three infants developed stroke recurrence after the initial diagnosis, all of which were precipitated by fall. Imaging studies in these children showed old gliosis on one side and acute infarct on the other side and all of them were on aspirin. The interval between first and second stroke was 2, 2, and 3 months, respectively. In patient number 32 (age of 18 months), the first stroke went unnoticed, presented with recurrent episodes of dystonia with hemiparesis.

Table 3.

Clinical features of patients with recurrent strokes

| Patient number | Age at first presentation | Interval between first and second stroke | Antiplatelet therapy before second stroke | Follow-up after second stroke |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 6 | 2 months | Aspirin | Residual dysarthria and hemiparesis at 16 months |

| 8 | 20 | Noted old and acute stroke at first presentation with hemiparesis | - | Mild residual hemiparesis at 16 months |

| 12 | 14 | Noted old and acute stroke at first presentation with hemiparesis | - | Mild residual hemiparesis at 16 months |

| 15 | 9 | 2 months | Aspirin | Mild residual hemiparesis at 8 months |

| 18 | 12 | Noted old and acute stroke at first presentation with hemiparesis | - | Mild residual hemiparesis at 19 months |

| 23 | 6 | 3 months | Aspirin | Speech delay and motor delay with residual hemiparesis at 22 months |

| 31 | 12 | Noted old and acute stroke at first presentation with hemiparesis | - | Speech delay and motor delay with residual hemiparesis at 14 months |

| 32 | 18 | Noted old and acute stroke at first presentation with recurrent dystonia | - | Speech delay and motor delay with residual hemiparesis at 18 months |

The mean follow-up time was 8.31 months (standard deviation [SD], 4.54 months; range, 6–22 months; median, 16 months). No deaths were observed in the study group. Eight of the infants with recurrent stroke had residual hemiparesis, one had dysarthria, and three had motor and speech delay. A total of 17 of the 30 infants who did not have stroke recurrence were normal on follow-up, whereas 9 of the infants showed persistent mild hemiparesis, 2 had motor delay, and 2 others had mild residual distal weakness.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we analyzed clinical characteristics, imaging features, and outcome of children who presented with basal ganglia stroke. The study group was formed by 38 infants with basal ganglia ischemic stroke and mineralization of lenticulostriate arteries detected on CT scan. Mean age at presentation in our study was 14.026 months (SD, ±5.8470 months), age group varied from 6 to 36 months. In total, 16 of 38 (42%) children were less than or equal to 1 year, which is comparable with previous study.[7] Of the 27 infants who had history of trauma, the event was caused by rolling over from a higher to a lower surface (from bed to ground) (n = 12) and falling while attempting to stand or walk (n = 15). Previous reports have also found an association between basal ganglia stroke in children younger than 18 months and recent trivial head trauma.[6,7,8] In eight of the infants, the onset of neurological symptoms was immediate. In 13 other children, the onset of neurological symptoms occurred between 10min and 8h after the fall. In six infants, the neurological symptoms manifested after 48h of trauma. Majority of children developed neurological symptoms within 8h of trauma, which is comparable to the previous study.[7]

None experienced loss of consciousness or seizures after fall. Hemidystonia was noted in 28 cases on the affected side with onset between 24 and 72h after the fall subsiding within 24h. This is comparable with the study by Lingappa et al.[7] Only one had recurrent hemidystonia, which presented after 48h of fall. Eleven children had similar presentation and courses without a recorded history of fall, as a trivial fall might not have been noticed by the parents.

CT of brain showed typical sharply marginated, linear hyperdense lesions emerging vertically through the inferior part of the lentiform nucleus similar to that described in anatomical literature about lenticulostriate arteries in all the infants. The number of mineralized arteries varied from one to five on each side. The infarct was situated on one of the mineralization arteries. These foci of hyperdensity within the infarcts have been variably interpreted as thrombus or tiny foci of hemorrhage in previous studies.[9,10]

Lenticulostriate vasculopathy is characterized by thickened hypercellular vessel walls with intramural and perivascular mineralization, which can be picked up easily by neurosonography, but exact etiology is not known.[11,12,13,14] Lingappa et al.[7] described it as a more severe and persistent form of lenticulostriate mineralization, which is extensive enough to be shown using CT. They proposed that mineralizing angiopathy is likely to represent pathological persistence of sonographic lenticulostriate vasculopathy.

A total of 8 of the 38 infants experienced recurrent strokes. Three of them developed recurrence on follow-up. All of them were on antiplatelet therapy. So the efficacy of antiplatelet agents in treatment of this particular entity is questionable and needs further research. Five of them showed old lesions in CT brain, but first episode had not come into clinical attention, probably because symptoms were subclinical.

Follow-up after 6 months of onset of the symptoms and signs showed complete recovery among 17 infants who did not have any recurrence. Nine had persistent mild hemiparesis, two had motor delay, and two had mild residual weakness. All children with recurrence had residual neurological deficit. Neurodevelopmental outcome on follow-up is comparable to previous study.[7]

Two familial cases were also noted (cases 35 and 24), the first one being born out of second-degree consanguineous marriage, whereas the second case being her maternal cousin. We could not find any similar cases reported in literature. The role of genetic factors in the incidence of mineralizing microangiopathy is not known and requires further research.

The infants in this series did not show any predilection for any particular gender, geographical, socioeconomic, or cultural backgrounds, or any particular ethnic group. These observations are comparable to previous case studies.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7]

The limitations of this study are that it is a retrospective study with short follow-up period. Investigations were not carried out uniformly. MRI with MRA and procoagulant workup was performed in only selected cases. Functional outcome was not categorized stringently and was largely subjective. Further studies should focus on etiological factors, role of genetic factors, underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, and efficacy of antiplatelet therapy in prevention of recurrence.

CONCLUSION

Basal ganglia stroke in young children is associated with mineralization of the lenticulostriate arteries, which, in most of the cases, was precipitated by trivial trauma. Two familial cases were also noted, and further studies are required to identify the role of genetic factors in this particular entity. We propose that the CT brain should be a part of workup in toddlers with stroke following trivial trauma.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge the help provided by the Department of Radiology, Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kieslich M, Fiedler A, Heller C, Kreuz W, Jacobi G. Minor head injury as cause and co-factor in the aetiology of stroke in childhood: a report of eight cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:13–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaffer L, Rich PM, Pohl KR, Ganesan V. Can mild head injury cause ischaemic stroke? Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:267–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.3.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishihara C, Sawada K, Tateno A. Bilateral basal ganglia infarction after mild head trauma. Pediatr Int. 2009;51:829–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2009.02924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seçkin H, Demirci AY, Değerliyurt A, Dağli M, Bavbek M. Posttraumatic infarction in the basal ganglia after a minor head injury in a child: case report. Turk Neurosurg. 2008;18:415–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobani ZA, Ali A. Pediatric traumatic putamenal strokes: mechanisms and prognosis. Surg Neurol Int. 2011;2:51. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.80116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang FH, Wang H, Zhang JM, Liang HY. Clinical features and risk factors of cerebral infarction after mild head trauma under 18 months of age. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;48:220–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lingappa L, Varma RD, Siddaiahgari S, Konanki R. Mineralizing angiopathy with infantile basal ganglia stroke after minor trauma. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56:78–84. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jauhari P, Sankhyan N, Khandelwal N, Singhi P. Childhood basal ganglia stroke and its association with trivial head trauma. J Child Neurol. 2016;31:738–42. doi: 10.1177/0883073815620674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn JY, Han IB, Chung YS, Yoon PH, Kim SH. Posttraumatic infarction in the territory supplied by the lateral lenticulostriate artery after minor head injury. Childs Nerv Syst. 2006;22:1493–6. doi: 10.1007/s00381-006-0157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dharker SR, Mittal RS, Bhargava N. Ischemic lesions in basal ganglia in children after minor head injury. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:863–5. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199311000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes P, Weinberger E, Shaw DW. Linear areas of echogenicity in the thalami and basal ganglia of neonates: an expanded association. Work in progress. Radiology. 1991;179:103–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.179.1.1848713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leijser LM, Steggerda SJ, de Bruïne FT, van Zuijlen A, van Steenis A, Walther FJ, et al. Lenticulostriate vasculopathy in very preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010;95:F42–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.161935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makhoul IR, Eisenstein I, Sujov P, Soudack M, Smolkin T, Tamir A, et al. Neonatal lenticulostriate vasculopathy: further characterisation. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:F410–4. doi: 10.1136/fn.88.5.F410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El Ayoubi M, de Bethmann O, Monset-Couchard M. Lenticulostriate echogenic vessels: clinical and sonographic study of 70 neonatal cases. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33:697–703. doi: 10.1007/s00247-003-0948-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]