Abstract

Diencephalic syndrome (DES) is an extremely uncommon occurrence, and approximately 100 cases have been reported. It presents as a failure to thrive in infants and children but rarely occurs in adult population. The characteristic clinical features of DES include severely emaciated body, normal linear growth and normal or precocious intellectual development, hyperalertness, hyperkinesis, and euphoria usually associated with intracranial sellar–suprasellar mass lesion, usually optico-chiasmatic glioma or hypothalamic mass. DES as a presentation of craniopharyngioma is extremely uncommon but can also occur with brain stem mass. Detailed PubMed and MEDLINE search for craniopharyngioma associated with DES yielded only six cases in children below 6 years of age. Thus, we reviewed a total of seven cases including previously published six cases and added additional our own case. Overall, the mean age at diagnosis was 4.15 years with male:female ratio of 4:3, the mean time interval between symptom of DES appearance and final diagnosis was 6.6 months. The most commonly observed symptom of DES was weight loss (85%). The clinical feature, imaging, and management of such rare syndrome along with pertinent literature are briefly reviewed.

KEYWORDS: Craniopharyngioma, diencephalic syndrome, failure to thrive, management, neuroimaging study

INTRODUCTION

In 1951, Russell described diencephalic syndrome (DES), characterized by the presence of profound emaciation during infancy associated with the loss of subcutaneous fat despite normal or slightly reduced calorie intake, nystagmus, and hyperkinesis, secondary to an intracranial neoplasm involving anterior hypothalamus or optico-chiasmatic glioma.[1] The clinical features of DES can be categorized into major and minor features. The major features include severe emaciation despite caloric intake being normal or slightly decreased, locomotor hyperactivity, and euphoria, whereas minor features comprise skin pallor, hypotension, and hypoglycemia. DES may also be associated with locomotor hyperkinesis, usually normal height, and endocrinologic functions.[2,3,4,5,6] As DES typically exhibits complex signs and symptoms related to hypothalamic dysfunction, such nonspecific clinical features often lead to miss diagnosis, and lack of awareness among physicians, pediatricians, and neurosurgeons and nonspecific presenting symptoms are other factors responsible for delayed diagnosis of DES and associated causative lesions.[2,7] In 2017, a review by Klochkova et al.[2] found out approximately 100 cases of DES in detailed literature search. Childhood craniopharyngiomas are usually associated with excessive weight gain and hypothalamic obesity but typical clinical manifestations include the development of a diencephalon syndrome with a failure to thrive or maintain weight at appropriate body mass index. Association of DES with craniopharyngioma is extremely uncommon.[4,5,6] We review seven children with DES that occurred in children less than 6 years of age with the diagnosis of craniopharyngioma.

CASE ILLUSTRATION

A 6-year-old boy presented to outpatient department with the complaints of progressive weight loss associated with diminution of vision for the last two and half years. He was the second issue of non-consanguineous parents with a history of normal growth and development with proper immunization at government primary health-care center. His parents consulted local practitioner, who advised medication; despite medication, he had progressive weight loss. The child had rapid deterioration of vision for 6 months for which parents also consulted ophthalmologist, and cranial computed tomography (CT) scan was advised to investigate the unexplained weight loss and thereafter referred to higher neurological center, where he was evaluated and biopsy of the intracranial mass lesion was taken; histopathological evaluation of the specimen was consistent with craniopharyngioma. General examination at current admission showed severely cachectic boy with a body weight of only 12kg [Figure 1], height 120cm, and body mass index of 8.3. He was conscious, oriented with absence of perception of light in both the eyes with spastic quadriparesis. Endocrinologic evaluation revealed low serum T3, T4, and cortisol levels, and accordingly hormonal supplementation was initiated. On admission, contrast-enhanced cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed the presence of a giant sellar–suprasellar heterogeneous mass lesion with intraventricular extension and the presence of associated obstructive hydrocephalus [Figures 2 and 3]. He first underwent bilateral ventriculoperitoneal shunt. After shunt surgery, he continued to receive nutritional supplementation along with hormonal replacement. He was taken up for left frontotemporal orbitozygomatic craniotomy with transcavernous approach; gross total excision of craniopharyngioma was carried out under general anesthesia. He had uneventful postoperative course except development of giant subdural hygroma on cerebral convexity ipsilateral of craniotomy and underwent successful surgical burr hole evacuation. He was discharged from hospital on the 18th day following surgery. At the last follow-up at 3 months after discharge from hospital, he regained weight but still continued to have bilateral absence of perception of light.

Figure 1.

Clinical photograph showing grossly emaciated body but preserved height

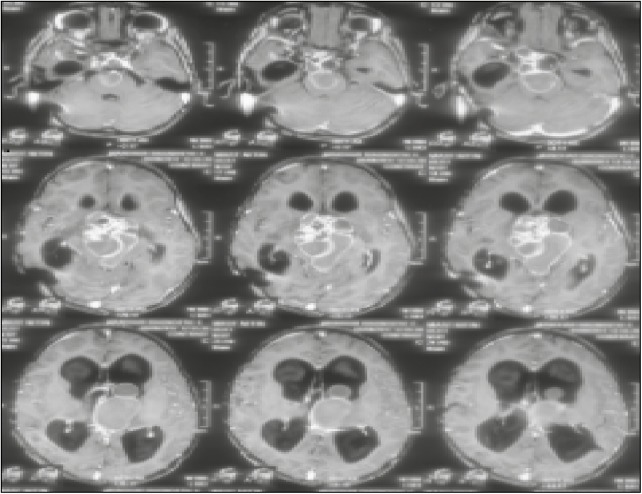

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced axial section MRI of brain showing heterogeneous multi-compartmental giant mass lesion in sellar, parasellar, and also extending into posterior fossa

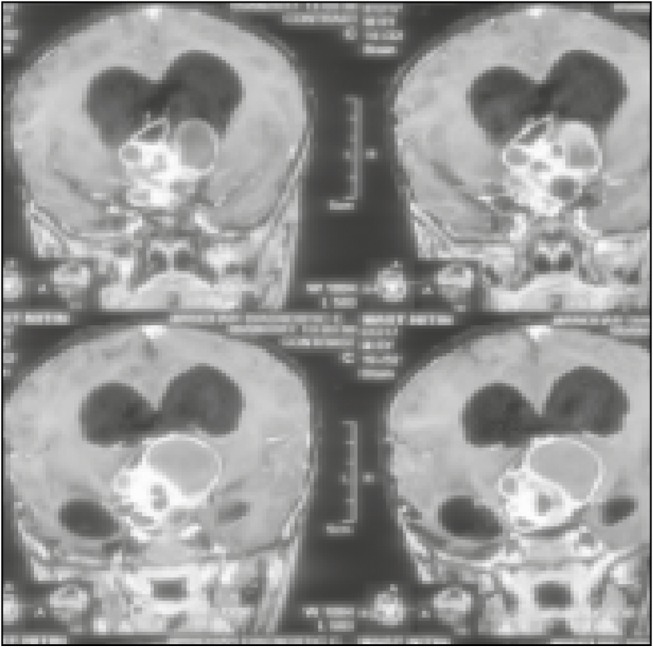

Figure 3.

MRI of brain, contrast-enhanced, coronal section image showing giant mass lesion with epicenter in sellar with extension into parasellar and posterior fossa region

DISCUSSION

DES diagnosis is based on the presence of major features comprising severe emaciation despite caloric intake being normal or slightly decreased, locomotor hyperactivity, and euphoria, and minor features such as skin pallor, hypotension, and hypoglycemia.[7] DES usually tends to occur in association with mass lesion located in the sellar–suprasellar hypothalamic region, comprising typically glioma of hypothalamic or optico-chiasmatic region but extremely rarely with craniopharyngioma. Children presenting with DES as a manifestation of intracranial tumor appear to present earlier than those presenting without DES with primary pathology as compared to general population. Similarly, DeSousa et al.[8] observed that the age at diagnosis of optic nerve gliomas was 14 months in patients associated with DES as clinical presentation compared to 27 months in those without DES. Similarly, Pelc[9] noted the median age at diagnosis of optic gliomas without DES was 6.5 years. Klochkova et al.[2] reported a case of DES in a 24-year-old female with papillary craniopharyngioma managed surgically, suggesting DES can also occur in adult population.

Our detailed literature search [Table 1] showed seven children with age below 6 years including our own one case.[4,5,6] The mean age of patients associated with craniopharyngioma presenting with DES was 4.15 years with the range of 2.4–6 years with male:female ratio of 1.3:1; the mean time interval between diagnosis and appearance of first symptom of DES was approximately 6.6 months. The most common presenting symptom of DES was loss of weight (85%). In our case, delay in the diagnosis of DES seen in the developing countries, which may be attributed to high prevalence of illiteracy and poverty, lack of adequate health-care facility as well as lack of awareness among physicians, led to delay in the confirmation of diagnosis by approximately two and half years.

Table 1.

Feature of previously reported craniopharyngioma associated with diencephalic syndromes in children less than 6 years of age

| S. no. | Author/references | Age (years)/sex | Duration of symptom (months) | Clinical features | Symptoms of diencephalic syndrome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Hoffman et al.[6] | 3.1/Male | 2 | Polyuria, polydipsia | Weight loss |

| 5.4/Female | 0.5 | Headache | Weight loss | ||

| 5.3/Female | 0.5 | Headache | Weight loss | ||

| 2.4/Male | 2 | Headache, raised intracranial pressure feature | Weight loss | ||

| 3.5/Male | 6 | Vomiting, polydipsia | Weight loss | ||

| 3.4/Female | 5 | Polydipsia, diarrhea, vomiting | Progressive weight loss | ||

| 2. | Current study | 6 years/Male | 30 | Loss of visual acuity | Weight loss |

Exact pathophysiology of DES development is still not well understood. Various postulates are hypothesized. These include release of hypothalamic growth hormone–releasing factors by intracranial neoplasm, which may in turn produce paradoxical response to hyperglycemias or hypoglycemic events. The elevated growth hormone levels probably result because of involvement of the hypothalamus.[9] Drop et al.[10] hypothesized unregulated release of β-lipotropin, produced in excess by either primary neoplasm or as a secondary effect to invasion causing excessive lipolysis and subsequently almost complete loss of subcutaneous tissue producing a characteristic cachectic appearance.

DES is a rare condition and usually heralds the presence of significant intracranial pathology and high clinical index of diagnosis of DES, and appropriate cranial imaging should be considered for infants and children. The role of different hormones including leptin, growth hormone, ghrelin, or insulin in the pathophysiology in DES is controversial, and routine endocrine hormonal assessment may be normal.[11] Visual manifestation includes reduction of visual acuity and decreased visual field, which occurs in 65% of cases.[12]

Diagnosis of the primary pathology includes CT scan for screening, whereas MRI study describes location, epicenter, extension, associated hydrocephalus, extension into ventricle, and encasement of neurovascular structures. In many cases, exact assessment of site of origin of tumor may be difficult as compared to larger tumor with usually aggressive biological behavior.[11]

Surgery remains the mainstay of therapy and maximum safe resection should be the aim, and subtotal tumor resection may be possible in selected cases as the involvement of visual pathways and pituitary–hypothalamic axis precludes often radical surgical surgical resection.[11] The role of radiotherapy is a matter of concern but encouraging results are observed with chemotherapy of optico-chiasmatic and hypothalamic region glioma. Stival et al.[1] reported a case of diencephalic cachexia because of hypothalamic anaplastic astrocytoma. After histological diagnosis, he received chemotherapy program followed by hematopoietic stem cell rescue with a good response. He had good visual function at 21 months after initiation of chemotherapy.[1]

Recovery of weight gain following surgery is gradual and progressively picks up over 2 years to approach almost up to the normal level. Kim et al.[7] retrospectively analyzed 11 cases of DES caused by proven hypothalamic involvement in cases of craniopharyngioma and observed that within the first 2 years of time interval following diagnosis and surgical management of craniopharyngioma, the weight of the patient increases and approaches to near normal and further noted that tumor size does not play a role with respect to DES development.

Conway et al.[13] reported a 21-month-old girl with a diagnosis of cervicomedullary brain stem astrocytoma, who presented with severe motor developmental delay, decreased growth velocity, and respiratory difficulty. She had features suggestive severe failure to thrive but typically neurologic signs associated with DES were not present.[13] Authors reported a rare case of hypothalamic glioma unassociated with DES in a 6-year-old boy who presented with seizures and diabetes insipidus and underwent near-total surgical decompression. He had a stormy postoperative course because of status epilepticus but went on to make a complete recovery. He remained symptom and seizure free on regular antiepileptic medication at 3 years following surgical management.[14]

CONCLUSION

DES represents an uncommon but very important cause of cachexia in infants, young children, and rarely in adults, which the physicians, neurologists, and neurosurgeons should be aware of, and in the event of any infants or children presenting with unexplained failure to thrive, the diagnosis of DES must be considered as one of the differential diagnosis. DES is most often associated with a hypothalamic or chiasmatic glioma but occasionally occurs with craniopharyngioma, and neuroimaging study and high index of suspicion increases hope for early confirmation of diagnosis and recovery of cachexia, and judicious adjuvant therapy is also advocated. These patients may regain body weight within 2 years of surgical and adjuvant therapy and usually carry a fair chance of recovery of weight loss.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stival A, Lucchesi M, Farina S, Buccoliero AM, Castiglione F, Genitori L, et al. An infant with hyperalertness, hyperkinesis, and failure to thrive: a rare diencephalic syndrome due to hypothalamic anaplastic astrocytoma. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:616. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1626-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klochkova IS, Astaf’eva LI, Konovalov AN, Kadashev BA, Kalinin PL, Sharipov OI, et al. [A rare case of diencephalic cachexia in an adult female with cranio-pharyngioma] Zh Vopr Neirokhir Im N N Burdenko. 2017;81:84–95. doi: 10.17116/neiro201781584-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tosur M, Tomsa A, Paul DL. Diencephalic syndrome: a rare cause of failure to thrive. BMJ Case Rep. 2017 Jul 6;:2017. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-220171. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-220171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rohrer TR, Fahlbusch R, Buchfelder M, Dörr HG. Craniopharyngioma in a female adolescent presenting with symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Klin Padiatr. 2006;218:67–71. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-921506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyoshi Y, Yunoki M, Yano A, Nishimoto K. Diencephalic syndrome of emaciation in an adult associated with a third ventricle intrinsic craniopharyngioma: case report. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:224–7; discussion 227. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200301000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffmann A, Gebhardt U, Sterkenburg AS, Warmuth-Metz M, Müller HL. Diencephalic syndrome in childhood craniopharyngioma–results of German multicenter studies on 485 long-term survivors of childhood craniopharyngioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:3972–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim A, Moon JS, Yang HR, Chang JY, Ko JS, Seo JK. Diencephalic syndrome: a frequently neglected cause of failure to thrive in infants. Korean J Pediatr. 2015;58:28–32. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2015.58.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeSousa AL, Kalsbeck JE, Mealey J, Jr, Fitzgerald J. Diencephalic syndrome and its relation to opticochiasmatic glioma: review of twelve cases. Neurosurgery. 1979;4:207–9. doi: 10.1227/00006123-197903000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelc S. The diencephalic syndrome in infants. A review in relation to optic nerve glioma. Eur Neurol. 1972;7:321–34. doi: 10.1159/000114436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drop SL, Guyda HJ, Colle E. Inappropriate growth hormone release in the diencephalic syndrome of childhood: case report and 4 year endocrinological follow-up. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1980;13:181–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1980.tb01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brauner R, Trivin C, Zerah M, Souberbielle JC, Doz F, Kalifa C, et al. Diencephalic syndrome due to hypothalamic tumor: a model of the relationship between weight and puberty onset. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2467–73. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olsen EM, Petersen J, Skovgaard AM, Weile B, Jørgensen T, Wright CM. Failure to thrive: the prevalence and concurrence of anthropometric criteria in a general infant population. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:109–14. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.080333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conway M, Ejaz R, Kouzmitcheva E, Savlov D, Rutka JT, Moharir M. Child neurology: diencephalic syndrome-like presentation of a cervicomedullary brainstem tumor. Neurology. 2016;87:e248–51. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta DK, Satyarthee GD, Sharma MC, Mahapatra AK. Hypothalamic glioma presenting with seizures. A case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2006;42:249–53. doi: 10.1159/000092364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]