Abstract

The stiffness of the microenvironment surrounding a cell can result in cytoskeletal remodeling, leading to altered cell function and tissue macrostructure. In this study, we tuned the stiffness of the underlying substratum on which neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were grown in culture in order to mimic normal (10 kPa), pathological stiffness of fibrotic myocardium (100 kPa), and a non-physiological extreme (glass). Cardiomyocytes were then challenged by beta adrenergic stimulation through isoproterenol treatment to investigate the response to acute work demand for cells grown on surfaces of varying stiffness. In particular, the PKCɛ signaling pathway and its role in actin assembly dynamics were examined. Significant changes in contractile metrics were seen for cardiomyocytes grown on different surfaces, but all cells responded to isoproterenol treatment, eventually reaching similar time to peak tension. In contrast, the assembly rate of actin was significantly higher on stiff surfaces, so that only cells grown on soft surfaces were able to respond to acute isoproterenol treatment. Förster Resonance Energy Transfer of immunofluorescence on the cytoskeletal fraction of cardiomyocytes confirmed that the molecular interaction of PKCɛ with the actin capping protein, CapZ, was very low on soft substrata, but significantly increased with isoproterenol treatment, or on stiff substrata. Therefore, the stiffness of the culture surface chosen for in vitro experiments might mask the normal signaling and affect the ability to translate basic science more effectively into human therapy.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

In response to functional demands, muscle remodels at the macroscopic level by changing the shape, cytoskeletal content, and performance of individual cardiomyocytes (CMs). The mechanisms for CM shape and strength are not fully understood, but it is likely to involve multiple processes, such as gene transcription, protein translation, post-translational modification, and the assembly of the sarcomeres in cell hypertrophy [Russell et al., 2010; Sanger et al., 2010]. Exercise or chronic disease increases cell hypertrophy, which has been modeled by static or dynamic strain of CMs in culture to reveal mechanisms by which sarcomeres are added [Li and Russell, 2013; Lin et al., 2013; Sharp et al., 1997; Torsoni et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2016; Yu and Russell, 2005]. Most studies are done either with acute or chronic loading models, but little is done to determine how cells respond to acute work when they are already in a chronically loaded pathological state.

It is well accepted that increased load leads to muscle bulking. A cell senses external forces impinging on it, which are balanced against forces generated internally by the sarcomere. Increased cell tension triggers mechanotransduction pathways, leading to thin filament assembly. Multiple mechanosensors detect increased mechanical loading to initiate actin filament assembly [Hoshijima, 2006; Skwarek-Maruszewska et al., 2009]. Forces are transmitted internally to the Z-disc, permitting an extensive amplification of filament assembly throughout the width and length of the CM. At the Z-disc, the thin actin filaments insert and reverse their polarity, making it the pivotal sarcomere assembling site in CMs [Gautel and Djinovic-Carugo, 2016]. Upon mechanical stimulation of CMs, assembly may be controlled in an hour by an acute bout of activity through modification of the actin capping protein, CapZ, where load increases actin dynamics, filament assembly, and cell size [Lin et al., Mechanotransduction arising from stress or strain modifies the function of CapZ by phosphorylation via protein kinase C (PKC) [Disatnik et al., 1994; Kim et al., 2010; Wear and Cooper, 2004], lipid binding with phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) [Hartman et al., 2009; Li et al., 2014; Li and Russell, 2013], and through acetylation [Lin et al., 2016]. Here, we concentrate on phosphorylation, which has recently been thoroughly reviewed [Scruggs et al., 2016]. In particular, the PKCε isoform translocates to the Z-disc when CMs are activated [Disatnik et al., 1994], where it is anchored to the myofilaments [Hartman et al., 2009; Pyle et al., 2006; Robia et al., 2001].

Mechanobiological cues read by a cell depend upon the underlying material scaffold for micro-scale, cell-specific instruction [Engler et al., 2008; Wozniak and Chen, 2009]. Stiffness of a 3D matrix significantly affects maturation and differentiation into myocytes [Jacot et al., 2010], as well as force generation [Bhana et al., 2010; Broughton and Russell, 2015; Curtis et al., 2013; Hazeltine et al., 2012]. The stiffness in the heart varies during development from embryonic/neonatal myocytes 5–10 kPa [Bhana et al., 2010] to the normal adult rat myocardium of 10–70 kPa [Yoshikawa et al., 1999]. Infarct stiffness and collagen content increase dramatically with time, so that by 6-weeks post-infarct it may rise to 400 kPa [Fomovsky et al., 2010; Fomovsky and Holmes, 2010]. Traditionally, cell culture is done almost exclusively using flat, hard, plastic surfaces, which poorly mimic the external forces existing in normal living tissues. Thus, most studies in culture actually mimic pathological conditions, which may obscure the more normal physiological signal transduction.

In this study, we use 10–100 kPa polyacrylamide substrata along with glass surfaces to mimic the softness of the healthy and pathological heart in order to study mechanotransduction. We explore the effects of the combination of acute and/or chronic loading on mechanosignaling by applying acute challenges through β-adrenergic receptor (βAR) stimulation of CMs cultured on substrata of varying stiffness. βAR activation by epinephrine or isoproterenol causes positive inotropy and chronotropy [Kaumann and Molenaar, 2008]. We assess contractility, actin assembly, PKCɛ signaling and distribution, as well as the molecular interactions between PKCɛ and CapZ. The effect of local tension and acute demand on CM contractility is assessed by line scan kymographs [Broughton and Russell, 2015]. Additionally, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) of sarcomeric actin is used to study actin dynamics [Hartman et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2013]. Proteomics, colocalization, and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) are used to study the molecular interactions of Z-disc proteins and PKCɛ distribution in the sarcomere. By these approaches, we determine that the effect of PKCɛ signaling seen in a soft environment following βAR stimulation is diminished in CMs within a stiff environment, a phenomenon that could contribute to maladaptive responses in disease states.

2 |. RESULTS

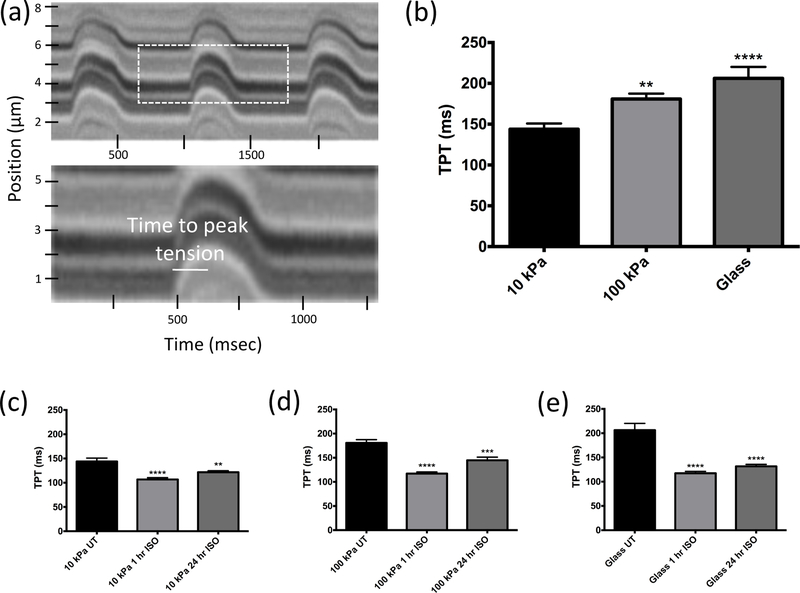

2.1 |. Substrate stiffness and increased acute demand alter contractile time to peak tension

Following culture for 48 hours, contractile measurements of CMs were made on varying substrate stiffness with or without isoproterenol treatment. A representative image of a line scan readout on a 10 kPa substrate shows characteristic peaks from which time to peak tension were obtained (Figure 1a). Untreated cells grown on 10 kPa, 100 kPa, and glass substrata had time to peak tension values of 144 ms, 181 ms, and 206 ms, respectively (Figure 1b). Statistically significant differences were seen in untreated 100 kPa and glass groups when compared to untreated 10 kPa group (p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001, respectively), though there was no significance between 100 kPa and glass (Figure 1b). Time to peak tension in all CMs was significantly reduced by treatment with isoproterenol compared to untreated CMs grown on 10 kPa (Figure 1c), 100 kPa (Figure 1d), or glass (Figure 1e).

Figure 1. Contractile time to peak tension decreases with increased stiffness, and with isoproterenol treatment of CMs on soft substrata.

(a) Representative line scan image acquisition showing how time to peak tension (TPT) was measured. y-axis is line scan position; x-axis is time. (b) Time to peak tension measurements for cells grown on 10 kPa (n=28 cells), 100 kPa (n=27 cells), and glass (n=21 cells). CMs grown with 1- or 24-hour isoproterenol treatment on (c) 10 kPa (n=24 and 22 for treated cells, respectively), (d) 100 kPa (n=27 and 17 for treated cells, respectively), or (e) glass (n=26 and 24 for treated cells, respectively). Values are mean ± SE. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001.

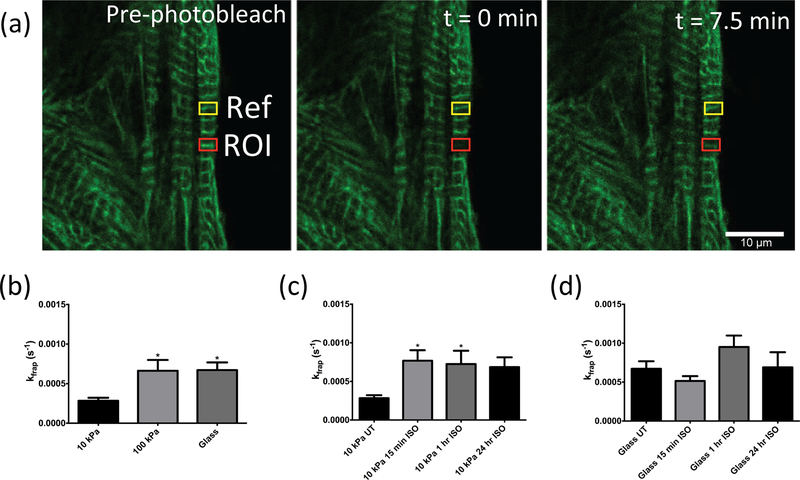

2.2 |. Actin cytoskeletal assembly rate increases with isoproterenol treatment on soft substrata

Actin-GFP infected cells cultured for 48 hours were photobleached to observe the rate of fluorescence recovery in sarcomeric actin over a 7.5 min time period (Figure 2a). Increased substrate stiffness led to significantly increased kfrap on 100 kPa and glass substrata when compared to 10 kPa (p < 0.05), but no difference was observed between 100 kPa and glass groups (Figure 2b). kfrap values of untreated cells on 10 kPa, 100 kPa, and glass substrata were 2.8×10−4 s−1, 6.6×10−4 s−1, 6.7×10−4 s−1, respectively. Notably, isoproterenol treatment led to significantly increased kfrap only on 10 kPa (p < 0.05 for 15-minutes and 1 hour) (Figure 2c), but there was no significant difference with isoproterenol treatment for CMs grown on glass (Figure 2d).

Figure 2. Actin dynamics increase with substrate stiffness, but only respond to isoproterenol treatment on 10 kPa substrata.

(a) Representative images showing FRAP experiment within region of interest (red box, ROI), pre-bleached (left panel), immediately following bleaching (middle panel), and after 7.5 minutes of recovery time (right panel). Scale bar, 10 µm. (b) kfrap values for cells grown 10 kPa, 100 kPa, or glass substrata (n=13, 17, and 15, respectively), and with 15-minute, 1-hour, or 24-hour isoproterenol treatment of CMs (c) on 10 kPa (n=12, 11, and 10 for treated cells, respectively), (d) or on glass (n=12, 12, and 14 for treated cells, respectively). Values are mean ± SE. * p < 0.05.

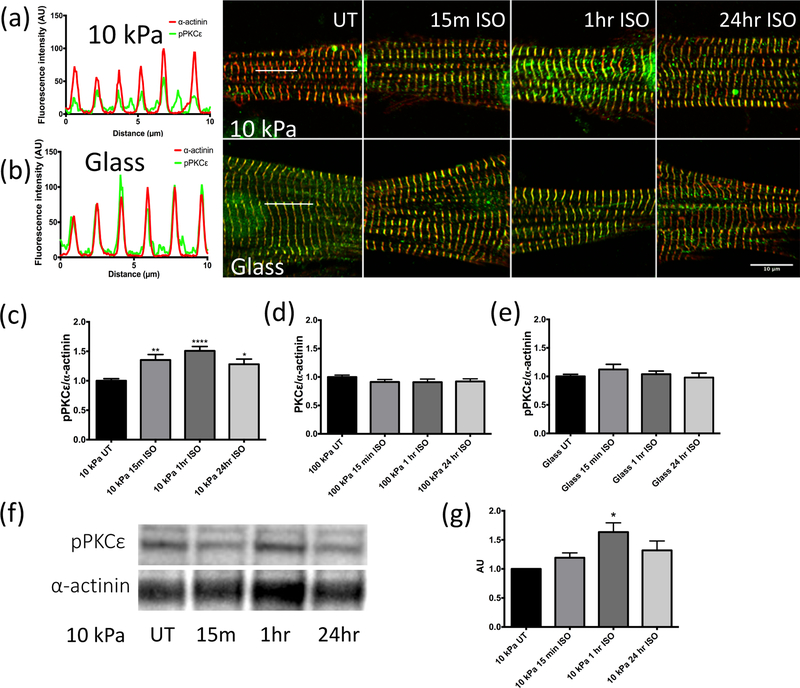

2.3 |. Time course of colocalization of phosphorylated PKCε and α-actinin with isoproterenol treatment of cardiomyocytes

CMs grown on 10 kPa, 100 kPa, or glass with membrane and cytosol extracted to retain the cytoskeleton were probed to study pPKCε distribution as a function of stiffness, and for the time course of increased muscle beating caused by βAR stimulation. Representative fluorescence images of pPKCε and α-actinin are shown in 10 kPa (Figure 3a) or glass (Figure 3b). Untreated CMs on 10 kPa had little yellow compared to treated groups, indicating lower colocalization at the Z-disc. A redistribution of pPKCε was seen with isoproterenol treatment as evidenced by increased yellow at the Z-disc, with peak levels reached between 15 minutes and 1 hour for cells grown on the soft substrate (Figure 3a), However, cells grown on glass remained strongly striated throughout isoproterenol treatment (Figure 3b). Line scans shown for 10 kPa and glass (left panels Figures 3a and b, respectively) were analyzed to acquire peak intensities and normalized to α-actinin. Histograms for ratios of pPKCε/α-actinin of fluorescence intensity (Figure 3c, d, and e for 10 kPa, 100 kPa, and glass, respectively) confirm the visual impressions. A significant difference due to isoproterenol treatment was observed only on 10 kPa substrata (Figure 3c), with ratio changes at 15 min, 1 hr, and 24 hr of 1.35-, 1.51-, and 1.28-fold compared to untreated baseline (p < 0.01, p < 0.0001, p < 0.05, respectively). However, no changes in colocalization of pPKCε and α-actinin were observed on 100 kPa or glass.

Figure 3. Localization of phosphorylated PKCε at the Z-disc increases with isoproterenol treatment of CMs on 10 kPa substrata.

Immunofluorescence images of CMs on 10 kPa or glass with phosphorylated PKCε (green), and α-actinin (red). (a) On 10 kPa substrata, pPKCε was low on untreated (UT) CMs but moved to the Z-disc with isoproterenol treatment, seen at 15 minutes, 1 hour, and 24 hours. (b) No change was seen over treatment time for cells grown on glass. (a) and (b) (left panels) show examples of line scans, drawn as white lines on UT panels, that were used to quantify colocalization of pPKCε and α-actinin with stiffness and time of isoproterenol treatment. Scale bar: 10 µm. (c), (d), (e): The ratio of pPKCε to α-actinin intensity at the Z-disc in untreated, 15-minute, 1-hour, and 24-hour isoproterenol treated cells was normalized within 10 kPa (n=28, 18, 28, and 26 cells, respectively), 100 kPa (n=42, 45, 34, and 42 cells, respectively), and glass (n=20 cells for all conditions) substrata, confirming increased localization only occurred on 10 kPa substrata. Values are mean ± SE. ** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001 compared to untreated 10 kPa group. (f) Representative western blot performed on the cytoskeletal fraction of cells grown on 10 kPa substrata. (g) Histogram of phosphorylated PKCε over time of isoproterenol treatment normalized to α-actinin in the untreated group (n=3). Values are mean ± SE. * p < 0.05.

In order to confirm the findings of PKCε phosphorylation, an independent biochemical approach was used with Western blot analysis on the cytoskeletal fraction of CMs (Figures 3f and g). PKCε phosphorylation on 10 kPa substrata following isoproterenol treatment began to increase by 15 minutes (not significant) and reached a maximum at 1-hour (p < 0.01), which was sustained but not significant at 24 hours. From untreated group, changes of 1.19-, 1.63-, and 1.32-fold are seen at 15-minute, 1-hour, and 24-hour treatments, respectively. Changes were not observed with isoproterenol treatment for cells grown on stiff substrata (data not shown).

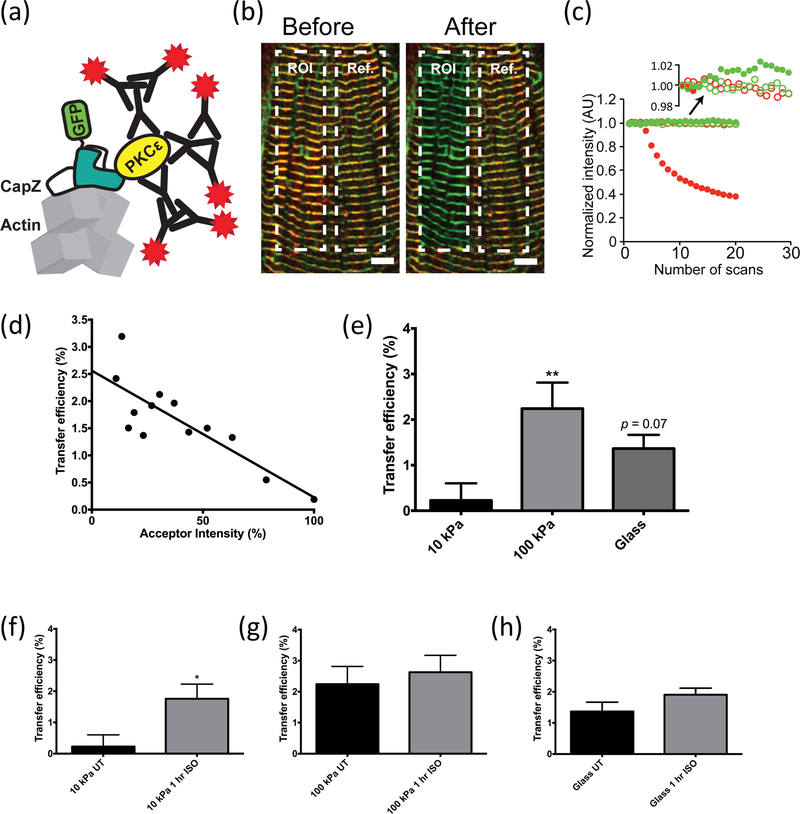

2.4 |. Molecular interactions of CapZ-GFP and pPKCε with stiffness and isoproterenol

Direct molecular interactions between CapZ-GFP and pPKCε were assessed by FRET (Figure 4a). Under glass and isoproterenol treatment for 1 hour, a typical ROI shown (Figure 4b left panel) was fully bleached after 20 scans (right panel), while the reference ROI was unchanged. Increasing donor fluorescence intensity (CapZ, green) was accompanied by concomitant acceptor intensity decay of pPKCε (red) (Figure 4c). The regression line between the acceptor intensity and transfer efficiency for this example (Figure 4d) showed a FRET response. Varying substrate stiffness resulted in a significant change in transfer efficiency in cells grown on 100 kPa substrata compared to 10 kPa (p < 0.01). Transfer efficiency was higher on glass substrata, but not significant (p = 0.07) (Figure 4e). Low transfer efficiency was seen for untreated cells on 10 kPa substrata, but this was significantly increased with 1-hour isoproterenol treatment (p < 0.05) (Figure 4f). Isoproterenol treatment did not lead to significant changes on stiff substrata (Figure 4g, h). These data suggest an increase in the molecular interactions between CapZ and pPKCε under stiff conditions, or when challenged to additional work under soft conditions.

Figure 4. FRET analysis of PKCε interaction with CapZ at the Z-disc.

CMs grown on 10 kPa and 100 kPa substrata or glass were infected by CapZ-GFP. Untreated and 1-hour isoproterenol treated CMs were compared following component extraction, fixation, and immunolabeling with pPKCε antibody (S729) and red secondary antibody for confocal imaging and FRET analysis. (a) Diagram showing how molecular range interactions of CapZ with the GFP (green) as donor and a secondary antibody to pPKCε (red) as acceptor. (b) A typical scan for a striated CM on glass with 1-hour isoproterenol treatment before scanning a region of interest (ROI) and the unbleached reference panel (Ref). Right panel shows after 20 scans the red acceptor is bleached leaving only the green donor fluorescence. (c) Photobleaching trace of pPKCε acceptor (solid, red circles) over 20 scans showing steady bleaching over time while the acceptor in the reference region is unchanged (open, red circles). The GFP donor (solid, green circles) increased slightly in bleached ROI (expanded in upper area for clarity) relative to the donor in the reference region (open, green circles). (d) Linear fit of acceptor intensity and transfer efficiency, where the intercept represents the recovered transfer efficiency (intercept = 2.56 %, R2 = 0.69). (e) Transfer efficiency significantly increased in 100 kPa compared to 10 kPa, but was not significantly different on glass (p = 0.07). (f), (g), (h) Changes in transfer efficiency when treated with isoproterenol on different stiffness conditions. Only 10 kPa exhibited a significant change following treatment (n=19 cells for 10 kPa and glass; n=10 cells for 100 kPa). Values are mean ± SE. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

3 |. DISCUSSION

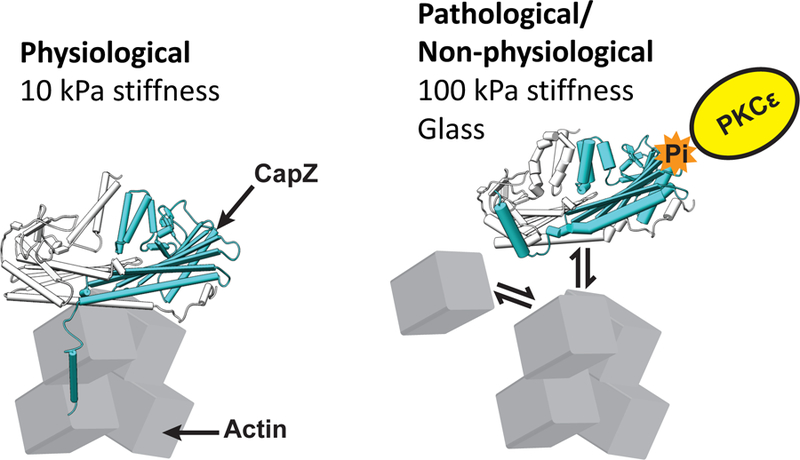

The objective of this study was to investigate the response to acute work demand for cells grown on surfaces of varying stiffness. In particular, the PKCɛ signaling pathway and its role in actin assembly dynamics were examined. Interestingly, novel findings suggest that pathological stiffness diminishes the effect of PKCɛ signaling on actin assembly in neonatal rat heart cells. Immunofluorescence studies found that substrate stiffness similar to the normal neonatal heart leads to significantly increased PKCɛ activation in the CM cytoskeleton upon isoproterenol treatment, whereas this response is not seen on pathological and non-physiological substrate stiffness. Our FRAP and FRET data further support the notion that at the pathological stiffness, CapZ is already phosphorylated, loosening the capping conformation, which results in increased actin assembly rate. A proposed mechanism is depicted (Figure 5), where upon translocation of PKCɛ to the sarcomere, CapZ is phosphorylated, leading to a conformational change and decreased association with the actin barbed end. In that scenario, isoproterenol treatment could not lead to additional phosphorylation of CapZ, and the actin assembly rate would remain the same. Conversely, CMs grown on physiological stiffnesses are free to undergo CapZ phosphorylation by PKCɛ and increase assembly rate accordingly.

Figure 5. Model for altered isoproterenol response with increased substrate stiffness.

Actin assembly rate is lower in CMs grown on surfaces mimicking physiological stiffness, and CMs are able to respond to isoproterenol treatment. CMs grown on surfaces mimicking chronic disease state are at a higher basal actin assembly rate and unable to respond to isoproterenol treatment. Conventional Petri dishes are stiffer than fibrotic tissue, so that many in vitro experiments might yield results that do not translate correctly for drug studies and human therapy.

At the tissue level, translocation of PKCɛ to the sarcomere has been associated with cardiac hypertrophy [Mochly-Rosen et al., 2000], a phenomenon correlated with increased actin assembly rate. PKCɛ translocation has also been shown in vitro following CM stretch [Vincent et al., 2006]. Our lab has demonstrated that mechanical stimulation through increased substrate stiffness or cyclic mechanical stretch leads to greater actin dynamics, which is mediated through a variety of signaling molecules, including PKCɛ, PIP2, and FAK [J. Li et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2015]. It has been shown that isoproterenol treatment leads to rapid translocation of PKCɛ to the cell particulate fraction [L. Li et al., 2015], making it a strong candidate here for implication in increased actin assembly rate. Indeed, this is supported by the increased FRAP kinetics that were seen 15 minutes after isoproterenol treatment.

We demonstrate that although the physiological metric of time to peak tension are altered by substrate stiffness, they each respond rapidly to βAR stimulation through isoproterenol stimulation, reaching common peak measurements. It is well known that changes in the mechanical environment leads to aberrations in CM contractility. In particular, a substrate tuned in stiffness to the natural myocardium yields embryonic CMs that work optimally [Engler et al., 2008]. Although the stiffness of the underlying substrata affected contractility, βAR stimulation still led to increases in contractile velocity, which is most easily explained by changes in calcium handling. PKCɛ-dependent phosphorylation of phospholamban [Okumura et al., 2014], as well as phospholamban and ryanodine receptor phosphorylation are triggered by various signaling molecules.

CMs here were grown on substrata of varying stiffness for two days before the acute isoproterenol treatment to provide time for the initial and subsequent response to occur. Lack of response under high stiffness could be part of a more persistent desensitization mechanism to β agonists. It is known that catecholamine response is depressed in the failing heart [El-Armouche and Eschenhagen, 2009]. Our results suggest a desensitization mechanism in single myocytes with two days of chronic high stiffness that caused a blunted response of PKCε to isoproterenol. This time might be sufficient for activation of beta signaling desensitization mechanisms like upregulation of G-coupled receptor kinase 5 [Islam and Koch, 2012; Zelarayan et al., 2009]. Our findings suggest that the chronic pathological state can be replicated by manipulating substrate stiffness levels.

It seems likely that filaments are built to serve the functional work being demanded by the myocyte, and that local mechanical conditions ultimately regulate filament assembly and muscle mass. Our findings suggest that the CM responds to acute changes in demand differentially based on the underlying matrix stiffness, a condition which would be altered with cardiac fibrosis. This could ultimately affect the response an individual might have to particular drug therapies. Results also suggest that the matrix stiffness on which cells are cultured has implications for drug screening studies. Since we show cells become non-responsive to treatment when grown for several days on a pathologically stiff surface, investigators might fail to detect results that are necessary to translate in vitro studies more effectively to human therapy.

4 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1 |. Isolation of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes

Primary heart cultures were obtained from 1–2 day old neonatal rats according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Hearts were removed and CMs isolated from 1–2 day old Sprague-Dawley rats with collagenase type II (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) as previously described [J. Li et al., 2015]. Neonatal rat ventricular CMs were re-suspended, filtered through a 70 µm nylon sieve to remove large material, and plated in PC–1 medium (Lonza Group, Basel, Switzerland). Dishes were coated with fibronectin for at least 2 hours prior to plating. Polyacrylamide (10 kPa and 100 kPa) substrata were functionalized according to previous studies prior to incubation with fibronectin [J. Li et al., 2015].

4.2. Line scans of live cardiomyocytes to measure contraction

Following 48-hour culture and drug treatment, CMs were placed into a temperature/CO2 chamber connected to a Zeiss 710 or 880 (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) confocal microscope system. Polarized, isolated individual CMs were selected in an unbiased manner, and a single line was scanned repeatedly at high speed along the contractile axis of the CM using transmitted light. Output kymographs were then analyzed using Zen software in order to measure time to peak tension. At least 17 cells over three separate cultures were analyzed for each condition.

4.3. Actin fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

CMs were grown in culture 24 hours before infecting cells with actin-GFP virus (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Cells were cultured an additional 24 hours before FRAP studies were carried out on adequately expressing striated cells within a temperature/CO2 chamber. A region of sarcomeric actin was photobleached to at least 50% of its original fluorescence intensity and re-imaged every five seconds for 450 seconds to monitor the rate of fluorescence recovery. The rate constant, kfrap, was determined using a single parameter, non-linear regression fit in OriginLab Pro (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA). Measurements were taken on cultures over several months, with at least 10 cells from each condition coming from 3 or more separate cultures.

4.4 |. Immunofluorescence

CMs were fixed using a 10% formalin solution, incubated overnight at 4°C in a 1:200 primary antibody, 1% BSA, 0.1% Tween-20 solution. Primary antibodies used for IF were anti-phospho-PKCε [S729] (pPKCε) (ab88241, abcam, Cambridge, MA), and anti-α-actinin (ab9465, abcam). Dishes were then washed and incubated at room temperature for one hour in a secondary antibody (Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L Alexa Fluor 488 or Goat anti-Mouse IgG H+L Alexa Fluor 568, Cat. # A-11034 and A-11004, ThermoFisher Scientific) in PBS. Secondary antibodies were diluted at 1:400 for α-actinin and 1:200 for pPKCε. Cells were counterstained using Vectashield Antifade mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). No changes were observed with antibodies to total-PKCε (ab124806, abcam) under any condition, so no data are reported.

4.5 |. Analysis of PKCε localization and phosphorylation using immunofluorescence

CMs grown in all conditions were fractionated to remove the membrane and cytosol but retain the cytoskeletal and nuclear fractions using the ProteoExtract Subcellular Proteome Extraction kit (MilliporeSigma, Billerica, MA) as described previously [Boateng et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2016; Ryba et al., 2017]. CMs were then probed with anti-α-actinin and pPKCε. Phosphatase inhibitor (not standard with kit, #539131, MilliporeSigma) was included to preserve sites of phosphorylation. CMs were then probed with secondary antibodies and mounted. For each material, intensity levels were normalized on a week-by-week basis to account for small variations in antibody dilutions or probing efficiency. Due to differences in optical properties, analysis was only conducted between cells grown on the same material/stiffness with the same antibody combination. For normalization, a maximum laser intensity and gain was found in untreated dishes and scaled back to account for potential experimental changes in levels, thus preventing peaking of fluorophore signal in subsequent dishes where changes might occur. This process was done for α-actinin and pPKCε. Following the setting of levels, all dishes within that stiffness and antibody combination were imaged at the same settings. Polarized, isolated CMs were chosen in an unbiased manner. Following acquisition, ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD) and a custom MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) script were used for analysis. Five line scans of at least 5 sarcomeres within a single cell were taken of α-actinin and pPKCε. Peak intensities of each Z-disc localization were determined, averaged, and the ratio of pPKCε/α-actinin was calculated and recorded. At least 5 cells were analyzed for each condition per culture, coming from at least 3 separate cultures.

4.6. Immunoblotting

The extraction kit was used per manufacturer protocol with the addition of phosphatase inhibitors as above. Samples were then prepared for western blot by adding 4X Laemmli sample buffer (BioRad, Inc., Hercules, CA). Protein extracts from sarcomeric subcellular fractions were resolved by SDS/PAGE, transferred to polyvinyl difluoride. Blots were blocked for one hour in 5% non-fat skim milk at room temperature and washed three times for 10 min each in tris-buffered saline, pH 7.5, containing 0.1% Tween-20. Blots were then probed in primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Antibodies were diluted in 2.5% bovine serum albumin and used at the following dilutions: 1:1000 anti-pPKCε [S729] (#06–821, MilliporeSigma) and anti-sarcomeric α-actinin.

4.7 |. Förster resonance energy transfer for molecular interactions of phosphorylated PKCε and CapZ

FRET interactions between CapZ-GFP and pPKCε by the acceptor photobleaching method [König et al., 2006] was used to determine nano-range interaction with higher resolution than can be determined with IF confocal microscopy of the Z-disc. CMs were infected with a mouse CapZβ1-GFP adeno-associated virus (MOI 20), incubated for 1 hour, washed with media, and left overnight as described [Hartman et al., 2009]. CMs were incubated with 2.5 μM isoproterenol for 1 hour. Dishes were treated with a cytosolic and membrane extraction buffer as described above. After gentle washing, CMs were fixed, incubated with a 1:100 dilution of anti-pPKCε antibody, a secondary antibody chosen because of its smaller size (F(ab’)2 anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555, A21430, ThermoFisher Scientific), a second formalin treatment to stabilize the acceptor probe, and mounted.

FRET response was determined by the acceptor photobleaching method. Serial scans of donor CapZ-GFP (ex: 488, em: 509) and acceptor (pPKCε secondary antibody, ex: 568, em: 603) signals were captured with alternating acceptor photobleaching steps in designated regions of interest (ROIs). We found that 20 scans taken over a two to three-minute time period were necessary to attain complete bleaching of the GFP donor necessary for the FRET analysis and curve flitting. Preliminary testing showing the optimal result was with an ROI of 100×500 µm2. Average donor fluorescence intensities in the acceptor photobleached ROI (D), a reference ROI (Dr), and a background ROI (Db) are used to compute the FRET efficiency E(i) in step i:

where D(0) and Dr(0) are the fluorescence intensities before the photobleaching sequence begins. The recovered transfer efficiency is estimated by extrapolation of E as a function of the acceptor intensity to the origin, in order to determine the intercept with the y-axis that represents the recovered transfer efficiency.

4.8 |. Statistics

Statistical analysis of experiments involving substrata of varying stiffness was done using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. For experiments testing the response of cells grown on a single stiffness following isoproterenol treatment (3 or more groups), the untreated group was considered the control, and one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used. Student’s t-test was used in experiments comparing two groups.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH HL-62426 (Brenda Russell, Project 2 and Chad M. Warren, Core C).

REFERENCES

- Bhana B, Iyer RK, Chen WLK, Zhao R, Sider KL, Likhitpanichkul M, Simmons CA, & Radisic M (2010). Influence of substrate stiffness on the phenotype of heart cells. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, Vol. 105, No.6, pp. 1148–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boateng SY, Belin RJ, Geenen DL, Margulies KB, Martin JL, Hoshijima M, de Tombe PP, & Russell B (2007). Cardiac dysfunction and heart failure are associated with abnormalities in the subcellular distribution and amounts of oligomeric muscle LIM protein. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology, Vol. 292, No.1, pp. H259–H269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton KM, & Russell B (2015). Cardiomyocyte subdomain contractility arising from microenvironmental stiffness and topography. Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Vol. 14, No.3, pp. 589–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MW, Budyn E, Desai TA, Samarel AM, & Russell B (2013). Microdomain heterogeneity in 3D affects the mechanics of neonatal cardiac myocyte contraction. Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology, Vol. 12, No.1, pp. 95–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disatnik MH, Buraggi G, & Mochly-Rosen D (1994). Localization of protein kinase C isozymes in cardiac myocytes. Experimental cell research, Vol. 210, pp. 287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Armouche A, & Eschenhagen T (2009). β-Adrenergic stimulation and myocardial function in the failing heart. Heart Failure Reviews, Vol. 14, No.4, pp. 225–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler AJ, Carag-Krieger C, Johnson CP, Raab M, Tang HY, Speicher DW, Sanger JW, Sanger JM, & Discher DE (2008). Embryonic cardiomyocytes beat best on a matrix with heart-like elasticity: scar-like rigidity inhibits beating. Journal of cell science, Vol. 121, No.Pt 22, pp. 3794–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomovsky GM, & Holmes JW (2010). Evolution of scar structure, mechanics, and ventricular function after myocardial infarction in the rat. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology, Vol. 298, No.Ivc, pp. 221–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomovsky GM, Thomopoulos S, & Holmes JW (2010). Contribution of extracellular matrix to the mechanical properties of the heart. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, Elsevier Ltd, Vol. 48, No.3, pp. 490–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautel M, & Djinovic-Carugo K (2016). The sarcomeric cytoskeleton: from molecules to motion. Journal of Experimental Biology, Vol. 219, No.2, pp. 135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman TJ, Martin JL, Solaro RJ, Samarel AM, & Russell B (2009). CapZ dynamics are altered by endothelin-1 and phenylephrine via PIP2- and PKC-dependent mechanisms. American journal of physiology - Cell physiology, Vol. 296, No.5, pp. C1034–C1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazeltine LB, Simmons CS, Salick MR, Lian X, Badur MG, Han W, Delgado SM, Wakatsuki T, Crone WC, Pruitt BL, & Palecek SP (2012). Effects of substrate mechanics on contractility of cardiomyocytes generated from human pluripotent stem cells. International journal of cell biology, Vol. 2012, p. 508294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshijima M (2006). Mechanical stress-strain sensors embedded in cardiac cytoskeleton: Z disk, titin, and associated structures. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology, Vol. 290, No.4, pp. H1313–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam KN, & Koch WJ (2012). Involvement of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway in regulation of cardiac G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 (GRK5) expression. Journal of Biological Chemistry, Vol. 287, No.16, pp. 12771–12778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacot JG, Martin JC, & Hunt DL (2010). Mechanobiology of cardiomyocyte development. Journal of Biomechanics, Elsevier, Vol. 43, No.1, pp. 93–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann AJ, & Molenaar P (2008). The low-affinity site of the β1-adrenoceptor and its relevance to cardiovascular pharmacology. Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Vol. 118, No.3, pp. 303–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T, Cooper JA, & Sept D (2010). The Interaction of Capping Protein with the Barbed End of the Actin Filament. Journal of Molecular Biology, Elsevier Ltd, Vol. 404, No.5, pp. 794–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König P, Krasteva G, Tag C, König IR, Arens C, & Kummer W (2006). FRET-CLSM and double-labeling indirect immunofluorescence to detect close association of proteins in tissue sections. Laboratory Investigation, Vol. 86, No.8, pp. 853–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Mkrtschjan MA, Lin YH, & Russell B (2015). Variation in stiffness regulates cardiac myocyte hypertrophy via signaling pathways. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, Vol. 94, No.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, & Russell B (2013). Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate regulates CapZβ1 and actin dynamics in response to mechanical strain. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology, Vol. 305, No.11, pp. H1614–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Tanhehco EJ, & Russell B (2014). Actin dynamics is rapidly regulated by the PTEN and PIP2 signaling pathways leading to myocyte hypertrophy. AJP: Heart and Circulatory Physiology, Vol. 307, No.11, pp. H1618–H1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Cai H, Liu H, & Guo T (2015). β-adrenergic stimulation activates protein kinase Cε and induces extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Molecular Medicine Reports, Vol. 11, No.6, pp. 4373–4380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YH, Li J, Swanson ER, & Russell B (2013). CapZ and actin capping dynamics increase in myocytes after a bout of exercise and abates in hours after stimulation ends. Journal of Applied Physiology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lin YH, Swanson ER, Li J, Mkrtschjan MA, & Russell B (2015). Cyclic mechanical strain of myocytes modifies CapZβ1 post translationally via PKCε. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility, Vol. 36, No.4–5, pp. 329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YH, Warren CM, Li J, McKinsey TA, & Russell B (2016). Myofibril growth during cardiac hypertrophy is regulated through dual phosphorylation and acetylation of the actin capping protein CapZ. Cellular Signalling, Elsevier B.V, Vol. 28, No.8, pp. 1015–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochly-Rosen D, Wu GY, Hahn H, Osinska H, Liron T, Lorenz JN, Yatani A, Robbins J, & Dorn GW II (2000). Cardiotrophic effects of protein kinase C e - Analysis by in vivo modulation of PKCe translocation. Circulation Research, Vol. 86, No.11, pp. 1173–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura S, Fujita T, Cai W, Jin M, Namekata I, Mototani Y, Jin H, Ohnuki Y, Tsuneoka Y, Kurotani R, Suita K, Kawakami Y, Hamaguchi S, Abe T, Kiyonari H, Tsunematsu T, Bai Y, Suzuki S, Hidaka Y, Umemura M, Ichikawa Y, Yokoyama U, Sato M, Ishikawa F, Izumi-Nakaseko H, Adachi-Akahane S, Tanaka H, & Ishikawa Y (2014). Epac1-dependent phospholamban phosphorylation mediates the cardiac response to stresses. Journal of Clinical Investigation, Vol. 124, No.6, pp. 2785–2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyle WG, La Rotta G, de Tombe PP, Sumandea MP, & Solaro RJ (2006). Control of cardiac myofilament activation and PKC-βII signaling through the actin capping protein, CapZ. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, Vol. 41, No.3, pp. 537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robia SL, Ghanta J, Robu VG, & Walker JW (2001). Localization and kinetics of protein kinase C-epsilon anchoring in cardiac myocytes. Biophysical Journal, Elsevier, Vol. 80, No.5, pp. 2140–2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell B, Curtis MW, Koshman YE, & Samarel AM (2010). Mechanical stress-induced sarcomere assembly for cardiac muscle growth in length and width. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, Elsevier Ltd, Vol. 48, No.5, pp. 817–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryba DM, Li J, Cowan CL, Russell B, Wolska BM, & Solaro RJ (2017). Long-Term Biased β-Arrestin Signaling Improves Cardiac Structure and Function in Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circulation, Vol. 135, No.11, pp. 1056–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger JW, Wang J, Fan Y, White J, & Sanger JM (2010). Assembly and dynamics of myofibrils. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology, Vol. 2010, No.Figure 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scruggs SB, Wang D, & Ping P (2016). PRKCE gene encoding protein kinase C-epsilon-Dual roles at sarcomeres and mitochondria in cardiomyocytes. Gene, Elsevier B.V, Vol. 590, No.1, pp. 90–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp WW, Simpson DG, Borg TK, Samarel AM, & Terracio L (1997). Mechanical forces regulate focal adhesion and costamere assembly in cardiac myocytes. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology, Vol. 273, No.2 Pt 2, pp. H546–H556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skwarek-Maruszewska A, Hotulainen P, Mattila PK, & Lappalainen P (2009). Contractility-dependent actin dynamics in cardiomyocyte sarcomeres. Journal of Cell Science, Vol. 122, No.12, pp. 2119–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torsoni AS, Marin TM, Velloso L a, & Franchini KG (2005). RhoA/ROCK signaling is critical to FAK activation by cyclic stretch in cardiac myocytes. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology, Vol. 289, No.4, pp. H1488–H1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent F, Duquesnes N, Christov C, Damy T, Samuel JL, & Crozatier B (2006). Dual level of interactions between calcineurin and PKC-ε in cardiomyocyte stretch. Cardiovascular Research, Vol. 71, No.1, pp. 97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear MA, & Cooper JA (2004). Capping protein: new insights into mechanism and regulation. Trends in biochemical sciences, Vol. 29, No.8, pp. 418–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak MA, & Chen CS (2009). Mechanotransduction in development: A growing role for contractility. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, Vol. 10, No.1, pp. 34–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Schmidt LP, Wang Z, Yang X, Shao Y, Borg TK, Markwald R, Runyan R, & Gao BZ (2016). Dynamic Myofibrillar Remodeling in Live Cardiomyocytes under Static Stretch. Scientific Reports, Nature Publishing Group, Vol. 6, pp. 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Y, Yasuike T, Yagi A, & Yamada T (1999). Transverse elasticity of myofibrils of rabbit skeletal muscle studied by atomic force microscopy. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, Vol. 256, No.1, pp. 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JG, & Russell B (2005). Cardiomyocyte Remodeling and Sarcomere Addition after Uniaxial Static Strain In Vitro. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry, Vol. 53, No.7, pp. 839–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelarayan L, Renger A, Noack C, Zafiriou M-P, Gehrke C, van der Nagel R, Dietz R, de Windt L, & Bergmann MW (2009). NF-κB activation is required for adaptive cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovascular Research, Vol. 84, No.3, pp. 416–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]