Abstract

Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) enzyme could be acted as a unique biomarker for forecasting and diagnosing certain diseases. Therefore, it is important to monitor PLA2 activity in biological and clinical samples. In this work, a simple electrochemical assay for PLA2 activity was developed based on a screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) with 3D graphene-like surface. When the PLA2-containing sample was mixed with the nanoprobes, i.e. the electroactive marker methylene blue (MB) encapsulated within nanometer-sized phospholipid liposomes, MB was released and adsorbed/enriched in site onto the surface of SPCE in a micro-cell. The encapsulation and enzymatic release of MB were evaluated using UV–Vis and fluorescence. The peak current due to oxidation of the adsorbed MB on the SPCE was measured by square-wave voltammetry (SWV). The current was directly linear to the PLA2 activity from 5 U/L to 200 U/L with a detection limit of 3 U/L. The same method can also be used for screening PLA2 inhibitors. Thus, the enrichment strategy developed in this work could be a promising signal amplification method for the sensitive and selective detection of PLA2 in biological or clinical samples.

Keywords: Phospholipase A2, Screen-printed carbon electrode, 3D graphene-like structure, Liposome, Methylene blue, Enrichment

1. Introduction

Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) is a heterogeneous group of enzymes that specifically recognize and catalytically hydrolize the sn-2 ester bond of glycerophospholipids, releasing free fatty acids such as arachidonic acid (AA) and lysophospholipids (Dennis et al., 2011). Owing to the involvement in a variety of homeostatic and pathologic processes, PLA2 enzyme could serve as a unique biomarker for forecasting and diagnosing certain diseases, including asthma (Triggiani et al., 2009), atherosclerosis (Kugiyama et al., 1999), pancreatitis (Agarwal and Pitchumoni, 1991), and some forms of cancer (Abe et al., 2003). For example, numerous studies have reported that PLA2 activity is significantly increased in the prostate cancer (Dong et al., 2010). Because of its diverse role, much effort has been recently devoted into the development of analytical methods, including radiometric-based assays (Aufenanger et al., 1993), pH-stat titration (Menashe et al., 1981), enzyme-linked immunoassay (Dorsam et al., 1995), surface plasmon resonance (Chen et al., 2014), colorimetric assay (Cho et al., 1988), fluorescence assay (Wichmann et al., 2007), and electrochemical sensors (Chen and Abruna, 1997; Wieckowska et al., 2011; Nayak et al., 2017), for the determination of PLA2 activity and concentration. However, these methods often suffer from limitations such as the high cost, complexity and inapplicable in biological or clinical samples. It would be desirable to develop a PLA2 assay that is sensitive, cost-effective, and easy-to-use in clinical or biological samples.

Liposome is an artificial phospholipid bilayer vesicle and could be acted as an ideal PLA2 substrate since PLA2 acts primarily on aggregated phospholipids that are organized within lipid bilayers (Singh et al., 2010). The aqueous interior of liposomes can be used to entrap almost any water-soluble signal molecule, such as fluorophores (Zhou and Li, 2015), enzymes (Qu et al., 2010), magnetic resonance materials (Cheng and Tsourkas, 2014) and electroactive molecules (Ho et al., 2010), owing to their unique composition and structure. Liposomes have been extensively used as carriers for signal molecules because signal amplification can be achieved by monitoring the large amount of signal molecules released from liposomes using appropriate detection methods (Liao and Ho, 2009). Electrochemical sensor-based methods are favorable due to their simplicity and ease of operation (Labib et al., 2016). However, the sensitivity of electrochemical detection may be limited, due to diluted signal molecules when they are released from liposomes into surrounding medium (Viswanathan et al., 2006). To address this problem, magnetic beads are used to enrich signal molecules on the electrode (Qi et al., 2013). The approach, however, is complicated and increases the cost for the analysis. Therefore, directly enrichment of the signal molecules on the electrode surface without aid is desirable.

The electrochemical sensor based on screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) is particularly attractive because it is highly portable, disposable and cost-effective (Ping et al., 2012). To improve selectivity or increase sensitivity (Arduini et al., 2016), various inorganic and organic materials including copper (Zen et al., 2003), porous nickel (Niu et al., 2013), polyaniline (Gosselin et al., 2017), redox polymers (Gao et al., 2002), bacteriophage (Shabani et al., 2008), gold nano-particles (Labib et al., 2012), and reduced graphene (Scala-Benuzzi et al., 2018) have been used to modify the SPCEs. One approach is to create graphene-based electrochemical sensors that possess abundant binding-sites which could enhance signal detection because of its large accessible surface area and distinct electronic properties (Haque et al., 2012; Pumera, 2010; Zhou et al., 2009a, 2009b). Modification approaches including drop casting, screen-and inkjet-printing and electrodeposition have often been used to prepare graphene-based screen-printed electrochemical (bio)sensors (Cinti and Arduini, 2017). However, the inevitable aggregation and restacking of graphene sheets induced from these modification approaches could significantly reduce the specific surface area and therefore affect the detection limit (Chen et al., 2010). Fabrication of 3D graphene structure can be adopted to overcome this problem (Zhang et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2013). However, preparation of 3D graphene structure on the electrode surface has been rarely reported (Bollella et al., 2017).

In this work, we developed an assay to monitor PLA2 activity based on electrochemical detection of methylene blue (MB) adsorbed on the SPCE with 3D graphene-like surface. MB is encapsulated into phospholipid liposomes. Once it is released from liposomes in the presence of PLA2, the released MB is strongly adsorbed on electrode surfaces because of its sufficient hydrophobicity property (Handa et al., 1990). To further increase detection limit, 3D graphene-like structure is also generated on a SPCE, which further enhances MB adsorption. Moreover, an electrochemical approach is used to prepare 3D graphene-like carbon structure on a SPCE in site, which is simple, environmentally friendly, and potentially scalable (Guo et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2009a, 2009b). The enzymatic release of MB from MB-loaded liposomal nanoprobes and enrichment of MB on the SPCE were investigated using optical and electrochemical methods. The developed assay was evaluated in real sample analysis and enzyme inhibition screening.

2. Experimental

2.1. Preparation of 3D graphene-like carbon structure on SPCE surface

Electrochemical method was used to obtain a 3D graphene-like carbon structure on the surface of SPCE. Electrochemical treatment was performed by applying a potential of 2 V on a bare SPCE for 2 min in a 0.2 M aqueous solution of ammonium sulfate. Then, a potential of 10 V was applied for another 1 min to exfoliate graphite on the SPCE surface electrochemically (Sevilla et al., 2016). After washing with pure water, the resultant SPCE was immersed into a phosphate-buffered solution (PBS), and a potential of −1.5 V was applied for 5 min for electro-chemical reduction of the oxidized graphene on the SPCE surface (Ambrosi and Pumera, 2013). After washing with water and drying, the as-prepared SPCEs were stored for further use. All processes were conducted with stirring at room temperature.

2.2. Preparation of MB-loaded liposomal nanoprobes

Liposomal nanoprobes were prepared by utilizing the thin-film hydration method following the previously published protocol (Cheng and Tsourkas, 2014). In brief, a mixture of 280 μL of DPPC (25 mg/mL) and 110 μL of DSPE-PEG2000 (25 mg/mL) stock solution in chloroform was placed in a round-bottom flask and dried under nitrogen, which formed a homogeneous lipid film on the flask walls. Then, trace amount of organic solvents was removed by maintaining the lipid film under vacuum for 12 h. This film was hydrated with 1 mL of HEPES buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) solution containing 100 mM MB, and then incubated at approximately 50 °C in a water bath for 1 h with vigorous shaking until the entire film peeled off the flask walls, followed by sonication for 10 min to produce MB-loaded liposomes. To increase the encapsulation efficiency, the liposome suspension was subjected into six freeze–thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen and water bath (50 °C).

The above liposome suspension was dialyzed for 24 h against distilled water by using a Snake Skin Dialysis Tubing (MD34, MWCO 7000, Thermo Scientific Inc.). The resultant solution was extruded for 10 times through 100 nm diameter polycarbonate membranes by using a stainless-steel extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids). The probe was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography with HEPES buffer as the mobile phase. The obtained MB-loaded liposome probes were stored in HEPES buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) at 4 °C for further use.

2.3. Analytical procedure

The MB-loaded liposomal nanoprobes (200 μL) and the PLA2-containing sample (200 μL) were dropped simultaneously on the SPCE surface in the micro-cell at room temperature. The cell was then covered to avoid drying, and an accumulation potential of −0.3 V (versus Ag/ AgCl) was applied during 60 min the incubation period. After washing, PBS was introduced into the electrochemical cell for the SWV analyses. Control experiments, i.e. without PLA2, were also conducted to evaluate SWV signal due to the nonspecific binding of liposomal nanoprobes on the electrode.

For the inhibitor assay, LY311727 was preincubated with PLA2 (100 U/L) in 50 μL of HEPES buffer for 20 min prior to mixing with the probe solution.

2.4. Determination of PLA2 in serum samples

Human serum specimens were obtained from the University Hospital of Shaanxi Normal University and centrifuged. For the assay of PLA2, serums were spiked with different concentrations of PLA2. PLA2 analyses were conducted with three replicates for each sample. The SWV peak current was averaged from three different measurements.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Principle of PLA2 activity detection

Principle of PLA2 activity detection was shown in Fig. 1. MB-loaded liposomal nanoprobes and PLA2-containing samples were co-dropped onto the surface of SPCE mounted in an electrochemical micro-cell. During incubation, MB was released from a liposome nanoprobe, due to enzymatic cleavage of phospholipids by PLA2 (Fig. 1A). Because of the strong adsorptive capacity of MB to the surface of graphite through π–π interaction (Kannan and Sundaram, 2001), the released MB molecules were adsorbed and then enriched on the surface of SPCE (Fig. 1B). After the PBS washing, PLA2 activity was monitored by measuring the electrochemical signals of adsorbed MB (Fig. 1C). To maintain the sample and nanoprobes on SPCE surface, an electrochemical cell with special design was used to mount the SPCE, as shown in Fig. S1. The exchange of SPCE can be easily performed by reopening the cell.

Fig. 1.

(A) The addition of PLA2 to the methylene blue (MB)-loaded liposome nanoprobe leads to hydrolysis of the phospholipid. (B) The released MB from the liposomes is strongly adsorbed onto a screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) with 3D graphene-like structure surface. (C) The PLA2 activity is monitored by measuring the electrochemical signal change.

3.2. Characteristic of MB-loaded liposomal nanoprobes

To reduce background signal and improve assay reproducibility, the nanometer-sized MB-loaded liposomes were prepared and un-encapsulated MB was completely removed (Fig. S2). After purification, the morphology and the size distribution of MB-loaded liposomes were analyzed by TEM and DLS. As shown in Fig. 2A, the liposomal nanop-robes exhibited similar particle sizes (approximately 110 nm), indicating that the successfully liposomal nanoprobes formation. DLS data also showed that the MB-loaded liposomal probes had narrow size distributions with a mean diameter of 110 nm (Fig. 2B). The polydispersity index (PDI) was 0.084, suggesting a good monodispersity.

Fig. 2.

MB-loaded liposome nanoprobes characterized by transmission electron microscopy (A) and dynamic light scattering profile (B).

To increase detection sensitivity, it is desirable to achieve the high MB concentration in liposome interior. Here, UV–vis analysis is used to study the liposomal encapsulation of MB since MB exhibits different optical absorption properties in the solution phase (Ghosh and Mukerjee, 1970). Fig. 3A shows the UV–vis spectra of MB-loaded liposomal nanoprobes before and after incubation with PLA2. The spectra of the probe (curve a) mainly shows the band at 590 nm with a small shoulder at 660 nm. MB could reversibly aggregate and the resulted stacking interactions provide both dimers (dimerization constant:4.71 × l03 M−1) and n-meric forms at relatively high concentrations in aqueous solution (Jockusch et al., 1995; Baeumner et al., 1996). The absorption at 590 nm could be reversible aggregation that forms MB oligomers or dimers, thus indicating a local high concentration of MB in a nanoprobe solution (Massari and Pascolini, 1977). The absorption at 660 nm can be attributed to the presence of small amounts of the monomer, because maximum absorbance of monomer and dimer species are located at 660 and 610 nm, respectively (Spencer and Sutter, 1979; Zanocco et al., 1998). After incubation of the liposome nanop-robes with 100 U/L PLA2, a large increase in absorption at 660 nm (MB monomer peak) was observed (curve b). The appearance of this spectrum indicates that the MB oligomers were released from the inner cavity of the liposome to the solution and decomposed into MB monomers owing to the decrease in MB concentration. Meanwhile, the original absorption maximum at 590 nm shifted to a longer wavelength by 20 nm, possibly because of the change in MB oligomers to dimers (Nakagaki et al., 1981). A substantial increase in the absorption in MB monomer peak and a decrease in MB dimer peak with the addition of Triton X-100 into probe solution were observed (curve c). This result indicates the complete release of MB to the buffer solution by treatment of the probes with a detergent. Thus, a high concentration of MB was successfully loaded into the liposome and entrapped MB can be released by PLA2.

Fig. 3.

(A) UV–vis absorbance spectra of the MB-loaded liposome nanoprobes (curve a), nanoprobes with 100 U/L of PLA2 (curve b), and nanoprobes after addition of Triton X-100 (curve c). (B) Fluorescence responses of different concentrations (bottom to up: 0, 20, 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300 U/L) of PLA2 to the MB-loaded liposome nanoprobes.

For the measurement of MB concentration in liposomal nanoprobes, 50 μL of liposomal nanoprobe was diluted to 1 mL with HEPES buffer (pH 7.4). Then, adsorption at 660 nm was measured after adding Triton X-100 into the solution. By comparison with standard calibration plot obtained using standard MB solutions (Fig. S3), the measured MB concentration was 2.2 mM in original liposomal nanoprobe solution. The relative standard deviation was 1.6% for five replicates.

The MB monomer presents fluorescence with a maximum at 690 nm when excited at 660 nm while the dimer was nonfluorescent. The nonfluorescent nature of the MB dimer was probably due to self-quenching of the dimer (Jockusch et al., 1996). Thus, the fluorescence intensity of MB was measured as a function of time after addition of PLA2, which was used to verify the release of encapsulated MBs from liposomal nanoprobes. PLA2 activity evaluation relies on intensity changes in MB fluorescence. As shown in Fig. 3B, the fluorescence increased after addition of PLA2. Measurements at varying PLA2 concentrations were performed to verify that the increase in MB fluorescence originated from the release of MB by PLA2 lysis. Results indicated that the fluorescence responses increased with increasing PLA2 concentration from 20 U/L to 300 U/L. Thus, MB was released from the liposome probe in the presence of PLA2.

3.3. Evaluation of SPCE platform for electrochemical sensing of PLA2

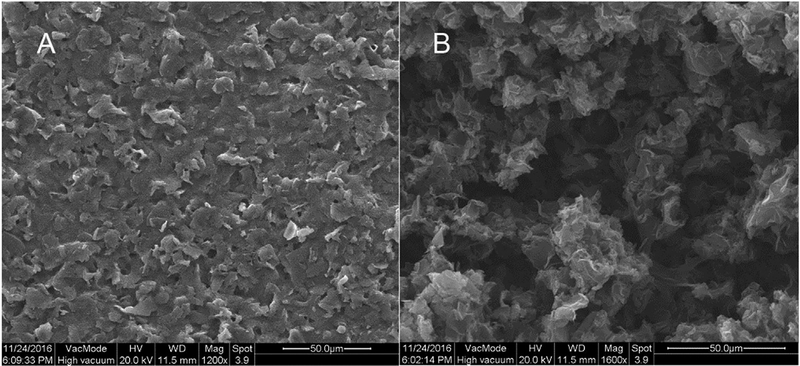

It was previously reported that the adsorption of phenothiazine dyes, such as MB, through stacking interactions on graphene was more favorable compared with the unmodified graphite surface (Liu et al., 2009; Yan et al., 2005). To improve the MB adsorption on the SPCE surface, a 3D graphene-like carbon structure was formed on the SPCE surface by electrochemical method. Morphology change following the electrochemical exfoliation of graphite mounted in SPCE surface was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The typical SEM image of a bare SPCE (Fig. 4A) showed a rough and jagged structure with graphite particles distributed randomly. After the electrochemical exfoliation, the graphite particles were expanded on the surface of SPCE, with the layers noticeably separated. In addition, a graphitic nanostructures consisting of petaloid flakes were observed (Fig. 4B). Due to incomplete exfoliation, the formed flakes appeared to be thicker than genuine graphene, which could indicate that densely packed graphene-like nanoflakes were formed on the SPCE. Thus, the SPCE modified with the unique 3D few-layer graphene-like carbon structures, consisting of randomly interconnected graphene-like sheets, was named 3D graphene-like SPCE.

Fig. 4.

Scanning electron microscopy images of SPCE before (A) and after (B) electrochemical treatment.

Electrochemical responses of the sensor in the presence of PLA2 were studied to evaluate the feasibility of the proposed assay. After incubation of the liposomal nanoprobe (200 μL) and sample on the SPCE surface, the cyclic voltammogram (CV) behavior of SPCE in 100 mM PBS (containing 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.0) was recorded. As shown in Fig. 5, no electrochemical response was observed when the sample did not contain PLA2 (curve a), indicating that MB-loaded liposome could not produce an electrochemical signal since the leakage of MB from liposome did not occur. However, a pair of well-defined peaks (approximately −0.2 V versus Ag/AgCl), corresponding to the reduction and oxidation of MB monomer on the SPCE surface, were observed when MB-loaded liposomal probes were incubated with the sample containing PLA2 (curve b). The redox reaction of MB was reversible on the SPCE surface, as evidenced by peak splitting (ΔEp = 20 mV). Then, the CVs of SPCE were investigated at various scan rates. Results showed that peak currents were linearly proportional to the scan rates of 200 mV s−1 (Fig. S4), indicating a surface redox process. This result suggests that the released MB molecules were successfully adsorbed on the electrode surface through the interaction between graphite and MB. Thus, our developed assay can be used to detect PLA2 activity. Compared with original SPCE (curve c), an approximately 40-fold increase in current was obtained on the SPCE with 3D graphene-like surface. Thus, the 3D graphene-like structure is beneficial for the adsorption and enrichment of MB on the SPCE surface. It should also be noted that, an increase in capacitive current was also observed as electrode surface areas were increased.

Fig. 5.

Cyclic voltammograms recorded by using the SPCE with 3D graphene-like surface after incubation with a mixture of the MB-loaded liposome nanoprobe and sample without PLA2 (curve a) and with 50 U/L PLA2 (curve b). (curve c) Cyclic voltammogram recorded by using the bare SPCE after incubation with a mixture of the MB-loaded liposome nanoprobe and sample with 50 U/L PLA2. Inset: A zoomed-in view of the curve c. Scan rate: 20 mV s−1.

3.4. Applications of the assay

To improve detection sensitivity, an accumulation potential was applied during the 60 min incubation. Since MB is a positively-charged ionic species, a potential varying from 0.1 V to −0.50 V was used to evaluate the accumulation behavior of MB on the electrode surface. Maximum peak current was observed for an accumulation potential of −0.3 V (Fig. S5), which was mainly due to the electrostatic interaction between the negative charged electrode at this potential and the positively charged MB monomer. Hence, an accumulation potential of −0.3 V was selected for further studies.

The optimal amount of the liposomal nanoprobes was also investigated. Using serums spiked with 50 U/L of PLA2 as sample, an increase in electrochemical signal was obtained when the volume of probe was changed from 0 μL to 150 μL (Fig. S6). With further increase in probe volume to 200 μL, no significant increase in sensor response was observed. Hence, the liposomal nanoprobe (200 μL) was considered as the optimum concentration.

Electrochemical measurements of MB were carried out in a blank buffer, detection of PLA2 activity was expected not to be interfered by most electroactive substances in serum. Therefore, the effect of some protein toward the nanoprobes was tested. The SWV signal was investigated in the presence of phospholipase C (PLC) or phospholipase D (PLD) (50 U/L), and the data was shown in Fig. S7. There was no significant response was observed when liposomal nanoprobes were incubated with PLD, and only a small change was observed for PLC. These results indicated that PLC and PLD did not affect PLA2 detection in this system. To mimic physiological conditions and evaluate the specificity of this assay, other potential interfering proteins, such as human serum albumin (HAS), hemoglobin, phosphatase, myoglobin, cytochrome C, transferrin, ribonuclease A, trypsin, protease, β-lactoglobulin, β-casein, actin, trypsinogen, lysozyme, and carbonic anhydrase (100 nM for each) were investigated. The results (Fig. S8) indicated that no significant response of the probe for these proteins was observed.

Under the optimal conditions, the PLA2 concentration-dependent behavior of the SWV peak current signal was investigated to evaluate the sensitivity of the assay in detecting PLA2. As shown in Fig. 6, the peak current increased with the increasing concentration of PLA2. The assay was shown to be linear over the wide range of 5.0 U/L to 200 U/L. A detection limit of 3.0 U/L was estimated at a signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of 3. Given that the cut-off value of human PLA2 is 6.0 U/L, the developed electrochemical sensor showed potential for the detection of PLA2 in clinical sample.

Fig. 6.

SWV recorded using the SPCE after incubation with a mixture of the MB-loaded liposome probe and sample with different concentrations of PLA2 (bottom to up: 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 50, 100, 150, 200 U/L).

The reproducibility of the assay was also investigated. Seven detections were performed to test a sample spiked with 50 U/L of PLA2. Results showed that the relative standard deviation for seven replications of different sensors was 6.8%, which indicated that the developed assay was acceptable in terms of the reproducibility.

This simple and sensitive assay was also evaluated for enzyme inhibition assay. LY311727, a commercial PLA2 inhibitor, was used to test the inhibition of PLA2 activity. Results showed that presence of LY311727 significantly decreased the SWV current signal (Fig. S9), indicating that PLA2 activity was inhibited by LY311727. Further studies showed that the IC50 value was 10 μM when the sample contained 100 U/L PLA2 (Fig. S10). Therefore, these results suggest that the developed assay can be used for screening PLA2 inhibitors.

To further demonstrate the clinical potential, five serum samples obtained from healthy individuals were tested by the electrochemical assay. The PLA2 activity was analyzed by the standard addition method and serum samples were spiked with 0–50 U/L PLA2. As shown in Table S1, the samples without any additional PLA2 showed no response and the recoveries of the assay are satisfactory (in the range of 98–108%), indicates that the developed assay is applicable and acceptable for detection of PLA2 activity in real samples.

4. Conclusions

A simple and sensitive assay was developed for the detection of PLA2 activity based on the electrochemical detection of PLA2 enzymatic released MB adsorbed on a SPCE with 3D graphene-like structure surface. PLA2 can hydrolyze phospholipids from MB-containing liposomal nanoprobes and release MB. The 3D graphene-like structure prepared by in-site electrochemical method on SPCE surface particularly favors the adsorption of the released MB from nanoprobes. The assay of PLA2 activity with high sensitivity (detection limit of 3 U/L) and selectivity was achieved by electrochemical detection of oxidation current of adsorbed MB on the SPCE. This simple assay could be applied to the detection of PLA2 in serum samples with acceptable sensitivity, and thus may be a promising tool for biological samples or Point-of-Care (POC) testing applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21175089), the Open Funds of the State Key Laboratory of Electroanalytical Chemistry (SKLEAC201807). This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, U.S.A R01NS100892 (Z.C.)

Footnotes

Supporting information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on Photo and figures mentioned in the main text.

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.bios.2018.11.004.

References

- Abe T, Sakamoto K, Kamohara H, Hirano Y, Kuwahara N, Ogawa M, 2003. Int. J.Cancer 1255, 351–360. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal N, Pitchumoni CS, 1991. Am. J. Gastroenterol 86, 1385–1391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosi A, Pumera M, 2013. Chem. Eur. J 19, 4748–4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arduini F, Micheli L, Moscone D, Palleschi G, iermarini S, Ricci F, Volpe G, 2016Trends Anal. Chem 79, 114–126. [Google Scholar]

- Aufenanger J, Zimmer W, Püttmann M, Ensenauer R, 1993. Eur. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem 31, 777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeumner AJ, Kummer T, Schmid RD, 1996. Anal. Lett 29, 2601–2613. [Google Scholar]

- Bollella P, Fusco G, Tortolini C, Sanzò G, Favero G, Gorton L, Antiochia R, 2017Biosens. Bioelectron 89, 152–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Tang LH, Li JH, 2010. Chem. Soc. Rev 39, 3157–3180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, Tsourkas A, 2014. Sci. Rep 4, 6958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Abruna HD, 1997. Langmuir 13, 5969–5973. [Google Scholar]

- Chen SH, Hsu YP, Lu HY, Ho JA, 2014. Biosens. Bioelectron 52, 202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Ren W, Gao L, Liu B, Pei S, Cheng HM, 2011. Nat. Mater 10, 424–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho W, Markowitz MA, Kezdy FJ, 1988. J. Am. Chem. Soc 110, 5166–5171. [Google Scholar]

- Cinti S, Arduini F, 2017. Biosens. Bioelectron 89, 107–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis EA, Cao J, Hsu YH, Magrioti V, Kokotos G, 2011. Chem. Rev 111,6130–6185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong ZY, Liu Y, Scott KF, Levin L, Gaitonde K, Bracken RB, Burke B, Zhai QJ,Wang J, Oleksowicz L, Lu S, 2010. Carcinogenesis 31, 1948–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsam G, Harris L, Payne M, Fry M, Franson R, 1995. Clin. Chem 41, 862–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao ZQ, Binyamin G, Kim HH, Barton SC, Zhang YC, Heller A, 2002. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 41, 810–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh AK, Mukerjee P, 1970. J. Am. Chem. Soc 92, 6408–6412. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin D, Gougis M, Baque M, Navarro FP, Belgacem MN, Chaussy D, Bourdat AG, Mailley P, Berthier J, 2017. Anal. Chem 89, 10124–10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo HL, Wang XF, Qian QY, Wang FB, Xia XH, 2009. ACS Nano 9, 2653–2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa T, Nakagaki M, Miyajima K, 1990. J. Colloid Int. Sci 137, 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Haque AJ, Park H, Sung D, Jon SY, Choi SY, Kim K, 2012. Anal. Chem 4,1871–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho JA, Hsu WL, Liao WC, Chiu JK, Chen ML, Chang HC, Li CC, 2010Biosens. Bioelectron 26, 1021–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jockusch S, Lee D, Turro NJ, Leonard EF, 1996. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93,7446–7451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jockusch S, Turro NJ, Tomalia DA, 1995. Macromolecules 28, 7416–7418. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan N, Sundaram MM, 2001. Dyes Pigments 51, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kugiyama K, Ota Y, Takazoe K, Moriyama Y, Kawano H, Miyao Y, Sakamoto T, Soejima H, Ogawa H, Doi H, Sugiyama S, Yasue H, 1999. Circulation 100, 1280–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labib M, Sargent EH, Kelley SO, 2016. Chem. Rev 116, 9001–9090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labib M, Zamay AS, Kolovskaya OS, Reshetneva IT, Zamay GS, Kibbee RJ, Sattar SA, Zamay TN, Berezovski MV, 2012. Anal. Chem 84, 8114–8117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao WC, Ho JA, 2009. Anal. Chem 81, 2470–2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Gao J, Xue MQ, Zhu N, Zhang MN, Cao TB, 2009. Langmuir 20,12006–12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu LH, Liu JH, Hu Y, Zhang YW, Chen W, 2013. Adv. Mater 25, 1270–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massari S, Pascolini D, 1977. Biochemistry 16, 1189–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menashe M, Lichtenberg D, Gutierrez-Merino C, Biltonen R, 1981. J. Biol. Chem 256, 4541–4543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagaki M, Katoh I, Handa T, 1981. Biochemistry 20, 2208–2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak S, Blumenfeld NR, Laksanasopin T, Sia SK, 2017. Anal. Chem 89, 102–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu XH, Lan MB, Zhao HL, Chen C, 2013. Anal. Chem 85, 3561–3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ping JF, Wang YX, Ying YB, Wu J, 2012. Anal. Chem 84, 3473–3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumera M, 2010. Chem. Soc. Rev 39, 4146–4157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi HL, Qiu XY, Xie DP, Ling C, Gao Q, Zhang CX, 2013. Anal. Chem 85,3886–3894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu B, Guo L, Chu X, Wu DH, Shen GL, Yu RQ, 2010. Anal. Chim. Acta 663,147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scala-Benuzzi ML, Raba J, Soler-Illia GJAA, Schneider RJ, Messina GA, 2018. Anal. Chem 90, 4104–4111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla M, Ferrero GA, Fuertes AB, 2016. Chem. Eur. J 22, 17351–17358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabani A, Zourob M, Allain B, Marquette CA, Lawrence MF, Mandeville R, 2008. Anal. Chem 80, 9475–9482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J, Ranganathan R, Hajdu J, 2010. Anal. Biochem 407, 253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer W, Sutter JR, 1979. J. Phys. Chem 83, 1573–1576. [Google Scholar]

- Triggiani M, Giannattasio G, Calabrese C, Loffredo S, Granata F, Fiorello A, Santini M, Gelb MH, Marone G, 2009. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 124, 558–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan S, Wu LC, Huang MR, Ho JA, 2006. Anal. Chem 78, 1115–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann O, Gelb MH, Schultz C, 2007. Chem. Biochem 8, 1555–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieckowska A, Jablonowska E, Rogalska E, Bilewicz R, 2011. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 13, 9716–9724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Zhang M, Gong K, Su L, Guo Z, Mao L, 2005. Chem. Mater 17, 3457–3463. [Google Scholar]

- Zanocco AL, Günther G, Lemp E, Lissi EA, 1998. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans 2,319–323. [Google Scholar]

- Zen JM, Chung HH, Yang HH, Chiu MH, Sue JW, 2003. Anal. Chem 75,7020–7025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WL, Xu C, Ma CQ, Li GX, Wang YZ, Zhang KY, Li F, Liu C, Cheng HM, Du YW, Tang NJ, Ren WC, 2017. Adv. Mater 29, 1701677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FL, Li BX, 2015. Anal. Chem 87, 7156–7162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Wang YL, Zhai YM, Zhai JF, Ren W, Wang F, Dong SJ, 2009a. Chem. Eur. J 15, 6116–6120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Zhai YM, Dong SJ, 2009b. Anal. Chem 14, 5603–5613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.