Abstract

Summary. This paper provides a linear sequence of four subfamilies, 15 tribes and 106 genera of the magnoliid family Annonaceae, based on state-of-the-art and stable phylogenetic relationships. The linear sequence facilitates the organisation of Annonaceae herbarium specimens.

Key Words: Annonaceae, classification, herbaria, phylogenetic hypotheses, systematics, taxonomy

Introduction

Plant taxonomy is a scientific expression for one of the defining characteristics of the human species: observing, assembling and classifying. The ordering of the plant world has been attempted ever since the origin of modern man, and even before. Neanderthals were able to distinguish fruit, nuts, roots, bulbs and tubers that were exploited as food resources (Henry et al. 2011), and upper palaeolithic hunter-gatherers recognised and categorised plants for economic and ritual uses (Nadel et al. 2013; Power et al. 2014). From Theophrastus onwards, in the fourth century BC, botanists have attempted to organise plants into classification systems. The sexual system published by Linnaeus (1753) in his Systema Naturae is the classical example of a classification system that has been designed for convenience, most notably to facilitate plant recognition and identification, and unequivocal communication about plants.

In Linnaeus’s time the practice of drying and conserving plants for future study was well established. In the first half of the 16th century, the Bolognese botanist Luca Ghini introduced a new way of studying plants by making the earliest hortus siccus. By pressing plants and storing them in a book, he invented the herbarium. It is in this era that botanic gardens, illustrated botanical publications, and herbaria were established as a trinity of resources for botanical sciences, a foundation that is still fundamental to botanical research today.

Botany in the eighteenth and nineteenth century to a large extent involved the rejection of Linnaeus’ artificial system, replacing it with classifications that reflected supposed evolutionary relationships based on careful observations of plant characters. This endeavour was greatly facilitated by collections that arrived in Europe from all over the world and were kept in newly established flourishing herbaria. Up to that point, private ownership of plant collections had been common practice. In the mid-19th century, however, these collections were often sold to the burgeoning herbaria, with the specific goal of making the collections available for study by staff and visitors. Until then, classifications such as those by Linnaeus and de Jussieu (1789) had primarily been based on European temperate plants. The influx of samples representing the wide plant diversity in colonial territories challenged these classification systems, with many non-temperate plant groups such as Annonaceae that were largely unknown to European botanists. Proliferating collections and botanical studies resulted in natural classifications by, e.g., Bentham & Hooker (1862 – 1883) and Engler & Gilg (1924), which have been the basis for taxonomic literature and for the arrangement of herbaria and botanic gardens for a long time. Given the Herculean task of changing the classification system followed in any sizeable herbarium (e.g. Wearn et al. 2013; Le Bras et al. 2017), many herbaria are still organised to date on the basis of outmoded classification systems going back in time a century or more.

Over the past two decades or so, phylogenetic systematics has resulted in a notable transformation of the classification of plants, and of angiosperms in particular. Based on the results of phylogenetic analyses, initially the delineation of angiosperm orders and families was evaluated and changed if necessary to make plant families comply with the prime guiding criterion of monophyly (APG I 1998; APG II 2003; APG III 2009; APG IV 2016). Subsequently, working groups of systematists have applied the results of phylogenetic analyses to revise infrafamilial classifications (e.g. Schneider et al. 2014; Bone et al. 2015; Chacón et al. 2016; Claudel et al. 2017; De Faria et al. 2017; Simões & Staples 2017), an endeavour that is still ongoing. Systematists have spent great effort in revising the classification of angiosperms because of the awareness that phylogenetics has brought methodological rigour to systematics and predictivity to classifications, which enabled the treatment of phylogenetic relationships — and therefore of classifications — as testable hypotheses, rather than opinions of scientists, however scholarly they might be.

Recently, the herbarium of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, was reorganised following the APG III system at the family level and taking phylogenetic classifications into account at the infrafamiliar level. Linear sequences of plant taxa enable curators to curate herbarium collections in accordance with phylogenetic relationships among genera. Linear sequences reflect the order of names attached to the tips of a phylogenetic tree, after the branches in the tree have been ordered according to some projection method. Alternatively, herbarium collections may be organised alphabetically, and the choice between an arrangement based on alphabet or on classification has been cause for debate (Funk 2003; Burger 2004). Storing collections according to any organising system remains indispensable as herbaria have retained their historic functions, being the basis for plant systematics and taxonomy, floristics and identification, assessment of botanical diversity, and teaching. In addition, scientific developments have unlocked new applications of herbarium collections, such as the characterisation of phenological responses to climate change (Willis et al. 2017), the assessment of global rarity of plant species to guide conservation (bioquality; Marshall et al. 2016), the sequencing of near-complete plastomes (Bakker et al. 2016; Hoekstra et al. 2017) and the targeted enrichment of nuclear genes (Hart et al. 2016), both for phylogenetic and evolutionary studies.

In this paper, we present a linear sequence of genera of Annonaceae. Generally, the family is among the most species-rich and abundant families in tropical rain forest communities (e.g. Cardoso et al. 2017; Sosef et al. 2017; Turner in press) and is amply represented in major herbaria.

Linear sequences

Haston et al. (2007, 2009) published a simple methodology for translating tree-like relationships into a linear sequence, and applied this to a phylogenetic tree of angiosperm families. Similarly, linear sequences have been produced for gymnosperms (Christenhusz et al. 2011a) and lycophytes and ferns (Christenhusz et al. 2011b). In order to extend the phylogenetic arrangement of collections to the level of genera, linear sequences that translate family phylogenies are indispensable. So far, linear sequences are available for Fabaceae (Lewis et al. 2013), and monocots excluding Poaceae and Orchidaceae (Trias-Blasi et al. 2015).

The assembly of the phylogenetic tree underpinning the linear sequence, and the translation of the tree into the sequence consisted of the following steps.

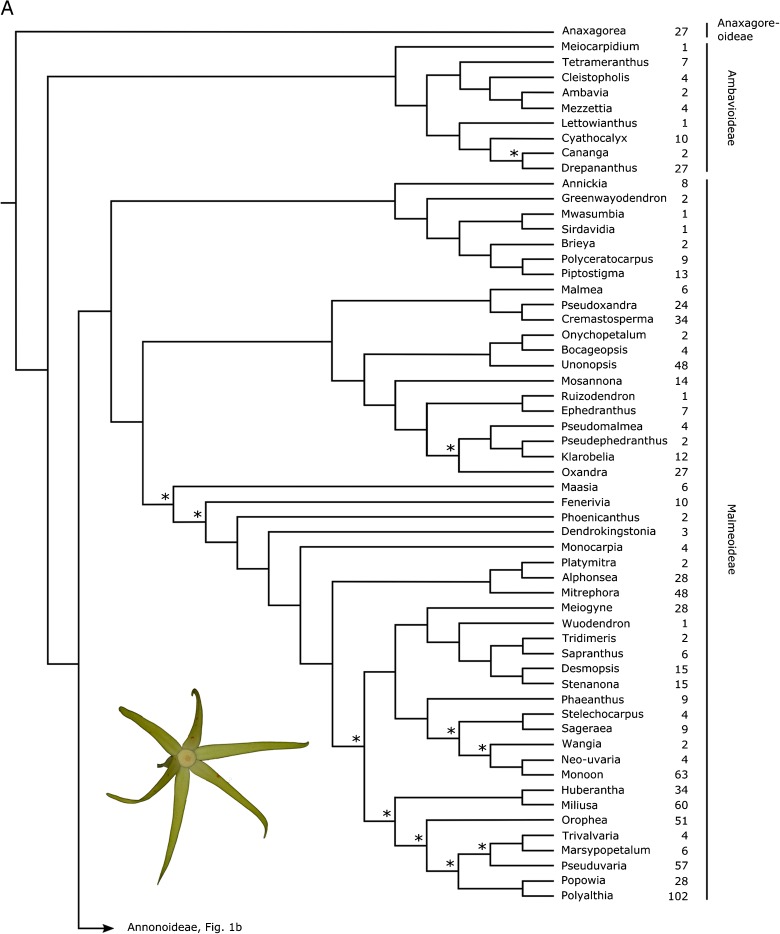

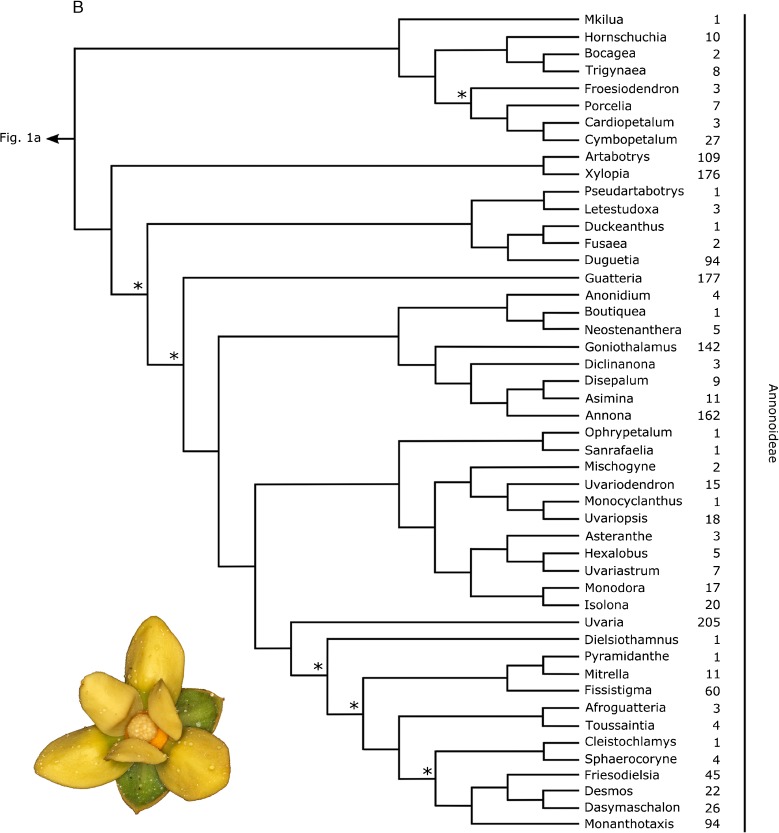

a summary tree showing relationships of all genera of Annonaceae was assembled. Details are given below, in the section ‘Annonaceae classification’. Nodes that did not receive significant support (parsimony or maximum likelihood bootstrap percentages, Bayesian posterior probabilities) in any of the published studies were resolved according to the topology most frequently inferred in all used publications.

we defined clade size in terms of number of species, and not number of higher taxa (e.g. number of genera to define the size of tribes) as the former estimate of clade size can be expected to be more stable than the latter, i.e. more robust to changing taxonomic concepts (Hawthorne & Hughes 2008).

species numbers for all genera were taken from Annonbase (Rainer & Chatrou 2006).

following Haston et al. (2007), nodes of the phylogenetic tree were rotated in such a way that clades with fewer species were placed before clades with more species. This clade size criterion was applied subsequently to all nodes in the tree, starting from the root node (Fig. 1). The names along the tips, reading down from the top, represent the linear sequence.

Fig. 1.

Summary tree underlying the linear sequence of Annonaceae genera (Fig. 1a: Anaxagoreoideae, Ambavioideae and Malmeoideae; Fig. 1b: Annonoideae). Nodes marked with an asterisk have not received significant support (parsimony or maximum likelihood bootstrap, Bayesian posterior probability) in any publication. The number of species for each genus is indicated. Inset pictures show flowers of Fenerivia capuronii (Cavaco & Keraudren) R. M. K. Saunders (Fig. 1a) and Guatteria aeruginosa Standl. (Fig. 1b). photos: l. w. chatrou.

Annonaceae classification

Historically, botanists have been reluctant to provide a classification for genera in the magnoliid family Annonaceae. Even though subfamilies and tribes were described by eminent botanists such as Rafinesque (1815), Endlicher (1839), Hooker & Thomson (1855) and Baillon (1868), these were hardly used by Annonaceae workers at the end of the 20th century, just before the breakthrough of phylogenetic methods. The classification most frequently referred to was the one by Fries (1959), who identified informal groups of genera but was reluctant to solidify his arrangement into a formal classification. Based on phylogenetic analyses of almost all genera, Chatrou et al. (2012) revised the infrafamilial classification of the family, and divided the family into four subfamilies and 14 tribes. An addition to the classification by Chatrou et al. (2012) was published by Guo et al. (2017b) with the new tribe Phoenicantheae, necessary to achieve monophyly of infrafamilial taxa belonging to the grade of species-poor lineages basal to tribe Miliuseae. Further detailed phylogenetic studies of specific tribes and genera, or the discovery of new genera of Annonaceae, did not reveal any previously overlooked deeper lineages within the family, and changes in generic circumscription could be accommodated into existing tribes (Chaowasku et al. 2012; Chaowasku et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2014; Xue et al. 2014; Chaowasku et al. 2015; Couvreur et al. 2015; Tang et al. 2015; Thomas et al. 2015; Ortiz-Rodriguez et al. 2016; Ghogue et al. 2017; Guo et al. 2017a; Stull et al. 2017; Pirie et al. 2018). Thus, we have arrived at a point where the classification of Annonaceae, principally based on plastid sequence data, can be considered stable, and can be used to arrange herbarium specimens. Annonaceae currently contain 2430 species (Rainer & Chatrou 2006, accessed 15th May 2018), classified into 106 genera.

A few decisions, which cannot be derived from the large-scale phylogenetic trees in Chatrou et al. (2012), Chaowasku et al. (2014) and Guo et al. (2017b), need to be justified:

We consider the generic name Haplostichanthus a synonym of Polyalthia. Xue et al. (2012) reduced nine species of Haplostichanthus into synonymy of Polyalthia, but did not discuss the status of Haplostichanthus gamopetala (Boerl. ex Koord.) Heusden. Given the morphological similarities of this species with other former species of Haplostichanthus (van Heusden 1994a) we consider this species a synonym of Polyalthia gamopetala Boerl. ex Koord., thus removing the name Haplostichanthus from accepted names in Annonaceae taxonomy.

Thomas et al. (2012) showed that species formerly included in Oncodostigma are nested in Meiogyne, thus validating the classification of some species of Oncodostigma in the latter genus by van Heusden (1994b). The last remaining species of Oncodostigma have recently been sunk into synonymy of Meiogyne (Turner & Utteridge 2015; Xue et al. 2017), making the further use of the name Oncodostigma unnecessary.

We have not included the genus Melodorum. The type specimen of the type species Melodorum fruticosum Lour. cannot be distinguished from Uvaria siamensis (Scheff.) L. L. Zhou, Y. C. F. Su & R. M. K. Saunders. The problem has been that Melodorum fruticosum has widely been misapplied to Sphaerocoryne spp. Guo et al. (2017b) note this as the probable reason that the position of Melodorum was not resolved before.

For the tribe Malmeeae we based the linear sequence on Chatrou et al. (2012) and Pirie et al. (2006) with one exception. Analysing an alignment of 66 plastid markers, Lopes et al. (2018) inferred the Malmea / Cremastosperma / Pseudoxandra clade as sister to the remaining Malmeeae, instead of the Onychopetalum / Bocageopsis / Unonopsis clade. As these relationships were maximally supported in Bayesian analyses we adopt the result of Lopes et al. (2018).

the position of Diclinanona was clarified in Erkens et al. (2014), that of Wangia was taken from Guo et al. (2014).

we consider the genus Winitia (Chaowasku et al. 2013) a synonym of Stelechocarpus (Turner 2016).

Linear sequence of Annonaceae

Accepted names are listed in bold and synonyms in italics. We listed Unona L.f. and Uva Kuntze as synonyms of Xylopia and Uvaria respectively, as the type specimens of the former two genera have been put into synonymy of the latter two. Note, however, that species previously classified in Unona or Uva can now be found in dozens of genera of Annonaceae.

We considered it beyond the scope of this paper to include details on revisions and other taxonomic information, for which we refer to a recent overviews (e.g. Maas et al. 2011; Erkens et al. 2012) and continuously updated taxonomic data in Annonbase (Rainer & Chatrou 2006), and the website http://annonaceae.myspecies.info.

A naxagoreoideae C hatrou , P irie , E rkens & C ouvreur

Anaxagorea A.St.-Hil.

Eburopetalum Becc., Pleuripetalum T. Durand, Rhopalocarpus Teijsm. & Binn. ex Miq.

A mbavioideae C hatrou , P irie , E rkens & C ouvreur

Meiocarpidium Engl. & Diels

Tetrameranthus R. E. Fr.

Cleistopholis Pierre ex Engl.

Ambavia Le Thomas

Mezzettia Becc.

Lonchomera Hook. f. & Thomson

Lettowianthus Diels

Cyathocalyx Champ. ex Hook. f. & Thomson

Cananga (Dunal) Hook. f. & Thomson

Canangium Baill. ex King, Fitzgeraldia F. Muell.

Drepananthus Maingay ex Hook. f.

M almeoideae C hatrou , P irie , E rkens & C ouvreur

Piptostigmateae Chatrou & R. M. K. Saunders

Annickia Setten & Maas

Enantia Oliv.

Greenwayodendron Verdc.

Mwasumbia Couvreur & D. M. Johnson

Sirdavidia Couvreur & Sauquet

Brieya De Wild.

Polyceratocarpus Engl. & Diels

Alphonseopsis Baker f., Dielsina Kuntze

Piptostigma Oliv.

Malmeeae Chatrou & R. M. K. Saunders

Malmea R. E. Fr.

Pseudoxandra R. E. Fr.

Cremastosperma R. E. Fr.

Onychopetalum R. E. Fr.

Bocageopsis R. E. Fr.

Unonopsis R. E. Fr.

Mosannona Chatrou

Ruizodendron R. E. Fr.

Ephedranthus S. Moore

Pseudomalmea Chatrou

Pseudephedranthus Aristeg.

Klarobelia Chatrou

Oxandra A. Rich.

Maasieae Chatrou & R. M. K. Saunders

Maasia Mols, Kessler & Rogstad

Fenerivieae Chatrou & R. M. K. Saunders

Fenerivia Diels

Phoenicantheae X. Guo & R. M. K. Saunders

Phoenicanthus Alston

Dendrokingstonieae Chatrou & R. M. K. Saunders

Dendrokingstonia Rauschert

Kingstonia Hook. f. & Thomson

Monocarpieae Chatrou & R. M. K. Saunders

Monocarpia Miq.

Miliuseae Hook. f. & Thomson

Platymitra Boerl.

Macanea Blanco

Alphonsea Hook. f. & Thomson

Mitrephora (Blume) Hook. f. & Thomson

Kinginda Kuntze

Meiogyne Miq.

Ancana F. Muell., Ararocarpus Scheff., Chieniodendron Tsiang & P. T. Li, Fitzalania F. Muell., Guamia Merr., Oncodostigma Diels, Polyaulax Backer

Wuodendron B. Xue, Y. H. Tan & Chaowasku

Tridimeris Baill.

Sapranthus Seem.

Desmopsis Saff.

Reedrollinsia J. W. Walker

Stenanona Standl.

Phaeanthus Hook. f. & Thomson

Stelechocarpus Hook. f. & Thomson

Winitia Chaowasku

Sageraea Dalzell

Wangia X. Guo & R. M. K. Saunders

Neouvaria Airy Shaw

Monoon Miq.

Cleistopetalum H. Okada, Enicosanthum Becc., Griffithia Maingay ex King, Griffithianthus Merr., Marcuccia Becc., Woodiella Merr., Woodiellantha Rauschert

Huberantha Chaowasku

Hubera Chaowasku

Miliusa Lesch. ex A. DC.

Hyalostemma Wall., Saccopetalum Benn.

Orophea Blume

Mezzettiopsis Ridl.

Trivalvaria (Miq.) Miq.

Marsypopetalum Scheff.

Pseuduvaria Miq.

Craibella R. M. K. Saunders, Y. C. F. Su & Chalermglin, Oreomitra Diels, Petalolophus K. Schum.

Popowia Endl.

Polyalthia Blume

Haplostichanthus F. Muell., Papualthia Diels, Sphaerothalamus Hook. f.

Annonoideae Raf.

Bocageeae Endl.

Mkilua Verdc.

Hornschuchia Nees

Mosenodendron R. E. Fr.

Bocagea A. St.-Hil.

Trigynaea Schltdl.

Froesiodendron R. E. Fr.

Porcelia Ruiz & Pav.

Cardiopetalum Schltdl.

Stormia S. Moore

Cymbopetalum Benth.

Xylopieae Endl.

Artabotrys R. Br.

Ropalopetalum Griff.

Xylopia L.

Coelocline A. DC., Habzelia A. DC., Krockeria Necker, Parabotrys Müll., Parartabotrys Miq., Patonia Wight, Pseudannona Saff., Unona L. f., Waria Aubl., Xylopiastrum Roberty, Xylopicron Adans., Xylopicrum P. Browne

Duguetieae Chatrou & R. M. K. Saunders

Pseudartabotrys Pellegr.

Letestudoxa Pellegr.

Duckeanthus R. E. Fr.

Fusaea (Baill.) Saff.

Duguetia A. St.-Hil.

Aberemoa Aubl., Alcmene Urb., Geanthemum (R. E. Fr.) Saff., Pachypodanthium Engl. & Diels

Guatterieae Hook. f. & Thomson

Guatteria Ruiz & Pav.

Guatteriella R. E. Fr., Guatteriopsis R. E. Fr., Heteropetalum Benth.

Annoneae Endl.

Anonidium Engl. & Diels

Boutiquea Le Thomas

Neostenanthera Exell

Stenanthera Engl. & Diels

Goniothalamus Hook. f. & Thomson

Atrutegia Bedd., Beccariodendron Warb., Richella A. Gray

Diclinanona Diels

Disepalum Hook. f.

Enicosanthellum Bân

Asimina Adans.

Deeringothamnus Small, Orchidocarpum Michx., Pityothamnus Small

Annona L.

Guanabanus Mill., Raimondia Saff., Rollinia A. St.-Hil., Rolliniopsis Saff.

Monodoreae Baill.

Ophrypetalum Diels

Sanrafaelia Verdc.

Mischogyne Exell

Uvariodendron (Engl. & Diels) R. E. Fr.

Monocyclanthus Keay

Uvariopsis Engl.

Dennettia Baker f., Tetrastemma Diels, Thonnera De Wild.

Asteranthe Engl. & Diels

Asteranthopsis Kuntze

Hexalobus A. DC.

Uvariastrum Engl.

Monodora Dunal

Isolona Engl.

Uvarieae Hook. f. & Thomson

Uvaria L.

Anomianthus Zoll., Armenteria Thouars ex Baill., Balonga Le Thomas, Cyathostemma Griff., Dasoclema J. Sinclair, Ellipeia Hook. f. & Thomson, Ellipeiopsis R. E. Fr., Marenteria Thouars, Melodorum Lour., Narum Adans., Naruma Raf., Pyragma Noronha, Rauwenhoffia Scheff., Tetrapetalum Miq., Uva Kuntze, Uvariella Ridl.

Dielsiothamnus R. E. Fr.

Pyramidanthe Miq.

Mitrella Miq.

Fissistigma Griff.

Afroguatteria Boutique

Toussaintia Boutique

Cleistochlamys Oliv.

Sphaerocoryne (Boerl.) Scheff. ex Ridl.

Friesodielsia Steenis

Oxymitra (Blume) Hook. f. & Thomson, Schefferomitra Diels

Desmos Lour.

Dasymaschalon (Hook. f. & Thomson) Dalla Torre & Harms

Pelticalyx Griff.

Monanthotaxis Baill.

Atopostema Boutique, Clathrospermum Planch. ex Benth., Enneastemon Exell, Exellia Boutique, Gilbertiella Boutique

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Bentham-Moxon Trust is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Thomas Couvreur and Michael Pirie for constructive criticism.

Contributor Information

Lars W. Chatrou, Email: lars.chatrou@wur.nl

Ian M. Turner, Email: i.turner@kew.org

References

- APG I An ordinal classification for the families of flowering plants. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 1998;85:531–553. doi: 10.2307/2992015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- APG II An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG II. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2003;141:399–436. doi: 10.1046/j.1095-8339.2003.t01-1-00158.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- APG III An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2009;161:105–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00996.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- APG IV An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016;181:1–20. doi: 10.1111/boj.12385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baillon, H. E. (1868). Anonacées. L. Hachette et Cie., Paris.

- Bakker FT, Lei D, Yu J, Mohammadin S, Wei Z, van de Kerke S, Gravendeel B, Nieuwenhuis M, Staats M, Alquezar-Planas DE, Holmer R. Herbarium genomics: plastome sequence assembly from a range of herbarium specimens using an Iterative Organelle Genome Assembly pipeline. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2016;117:33–43. doi: 10.1111/bij.12642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bentham, G. & Hooker, J. D. (1862 – 1883). Genera Plantarum. A. Black, London.

- Bone RE, Cribb PJ, Buerki S. Phylogenetics of Eulophiinae (Orchidaceae: Epidendroideae): evolutionary patterns and implications for generic delimitation. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2015;179:43–56. doi: 10.1111/boj.12299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burger WC. Up with alphabetically arranged herbaria (and with floristic listings too for that matter) Plant Sci Bull. 2004;50:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso D, Särkinen T, Alexander S, Amorim AM, Bittrich V, Celis M, Daly DC, Fiaschi P, Funk VA, Giacomin LL, Goldenberg R, Heiden G, Iganci J, Kelloff CL, Knapp S, Cavalcante de Lima H, Machado AFP, dos Santos RM, Mello-Silva R, Michelangeli FA, Mitchell J, Moonlight P, de Moraes PLR, Mori SA, Nunes TS, Pennington TD, Pirani JR, Prance GT, de Queiroz LP, Rapini A, Riina R, Rincon CAV, Roque N, Shimizu G, Sobral M, Stehmann JR, Stevens WD, Taylor CM, Trovó M, van den Berg C, van der Werff H, Viana PL, Zartman CE, Forzza RC. Amazon plant diversity revealed by a taxonomically verified species list. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:10695–10700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706756114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacón J, Luebert F, Hilger HH, Ovchinnikova S, Selvi F, Cecchi L, Guilliams CM, Hasenstab-Lehman K, Sutorý K, Simpson MG, Weigend M. The borage family (Boraginaceae s.str.): A revised infrafamilial classification based on new phylogenetic evidence, with emphasis on the placement of some enigmatic genera. Taxon. 2016;65:523–546. doi: 10.12705/653.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaowasku T, Johnson DM, van der Ham RWJM, Chatrou LW. Characterization of Hubera (Annonaceae), a new genus segregated from Polyalthia and allied to Miliusa. Phytotaxa. 2012;69:33–56. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.69.1.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaowasku T, Johnson DM, van der Ham RWJM, Chatrou LW. Huberantha, a replacement name for Hubera (Annonaceae: Malmeoideae: Miliuseae) Kew Bull. 2015;70:23. doi: 10.1007/s12225-015-9571-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaowasku T, Thomas DC, van der Ham RWJM, Smets EF, Mols JB, Chatrou LW. A plastid DNA phylogeny of tribe Miliuseae: Insights into relationships and character evolution in one of the most recalcitrant major clades of Annonaceae. Amer. J. Bot. 2014;101:691–709. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1300403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaowasku T, van der Ham RWJM, Chatrou LW. Integrative systematics supports the establishment of Winitia, a new genus of Annonaceae (Malmeoideae, Miliuseae) allied to Stelechocarpus and Sageraea. Syst. Biodivers. 2013;11:195–207. doi: 10.1080/14772000.2013.806370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatrou LW, Pirie MD, Erkens RHJ, Couvreur TLP, Neubig KM, Abbott JR, Mols JB, Maas JW, Saunders RMK, Chase MW. A new subfamilial and tribal classification of the pantropical flowering plant family Annonaceae informed by molecular phylogenetics. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2012;169:5–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2012.01235.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christenhusz MJM, Reveal JL, Farjon A, Gardner MF, Mill RR, Chase MW. A new classification and linear sequence of extant gymnosperms. Phytotaxa. 2011;19:55–70. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.19.1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christenhusz MJM, Zhang X-C, Schneider H. A linear sequence of extant families and genera of lycophytes and ferns. Phytotaxa. 2011;19:7–54. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.19.1.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Claudel C, Buerki S, Chatrou LW, Antonelli A, Alvarez N, Hetterscheid W. Large-scale phylogenetic analysis of Amorphophallus (Araceae) derived from nuclear and plastid sequences reveals new subgeneric delineation. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2017;184:32–45. doi: 10.1093/botlinnean/box013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Couvreur TLP, Niangadouma R, Sonké B, Sauquet H. Sirdavidia, an extraordinary new genus of Annonaceae from Gabon. PhytoKeys. 2015;46:1–19. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.46.8937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Faria AD, Pirani JR, Ribeiro JELDS, Nylinder S, Terra-Araujo MH, Vieira PP, Swenson U. Towards a natural classification of Sapotaceae subfamily Chrysophylloideae in the Neotropics. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2017;185:27–55. doi: 10.1093/botlinnean/box042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Endlicher S. Genera plantarum secundum ordines naturales disposita. Fr. Vienna: Beck Universitatis Bibliopolam; 1839. [Google Scholar]

- Engler A, Gilg E. Syllabus der Pflanzenfamilien. Berlin: Gebrüder Borntraeger Verlag; 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Erkens RHJ, Chatrou LW, Chaowasku T, Westra LYT, Maas JW, Maas PJM. A decade of uncertainty: Resolving the phylogenetic position of Diclinanona (Annonaceae), including taxonomic notes and a key to the species. Taxon. 2014;63:1244–1252. doi: 10.12705/636.34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erkens RHJ, Mennega EA, Westra LYT. A concise bibliographic overview of Annonaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2012;169:41–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2012.01232.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fries RE. Annonaceae. In: Engler A, Prantl K, editors. Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien. ed. 2. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot; 1959. pp. 1–171. [Google Scholar]

- Funk VA. Down with alphabetically arranged herbaria (and alphabetically arranged floras too for that matter) Plant Sci Bull. 2003;49:131–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ghogue J-P, Sonké B, Couvreur TLP. Taxonomic revision of the African genera Brieya and Piptostigma (Annonaceae) Plant Ecol. Evol. 2017;150:173–216. doi: 10.5091/plecevo.2017.1137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Hoekstra PH, Tang CC, Thomas DC, Wieringa JJ, Chatrou LW, Saunders RMK. Cutting up the climbers: Evidence for extensive polyphyly in Friesodielsia (Annonaceae) necessitates generic realignment across the tribe Uvarieae. Taxon. 2017;66:3–19. doi: 10.12705/661.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X., Tang, C. C., Thomas, D. C., Couvreur, T. L. P. & Saunders, R. M. K. (2017b). A mega-phylogeny of the Annonaceae: taxonomic placement of five enigmatic genera and support for a new tribe, Phoenicantheae. Sci. Rep. 7: 7323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Guo X, Wang J, Xue B, Thomas DC, Su YCF, Tan Y-H, Saunders RMK. Reassessing the taxonomic status of two enigmatic Desmos species (Annonaceae): Morphological and molecular phylogenetic support for a new genus, Wangia. J. Syst. Evol. 2014;52:1–15. doi: 10.1111/jse.12064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hart ML, Forrest LL, Nicholls JA, Kidner CA. Retrieval of hundreds of nuclear loci from herbarium specimens. Taxon. 2016;65:1081–1092. doi: 10.12705/655.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haston E, Richardson JE, Stevens PF, Chase MW, Harris DJ. A linear sequence of Angiosperm Phylogeny Group II families. Taxon. 2007;56:7. [Google Scholar]

- Haston E, Richardson JE, Stevens PF, Chase MW, Harris DJ. The Linear Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (LAPG) III: a linear sequence of the families in APG III. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2009;161:128–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.01000.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne WD, Hughes CE. Optimising linear taxon sequences derived from phylogenetic trees — a reply to Haston & al. Taxon. 2008;57:698–704. [Google Scholar]

- Henry AG, Brooks AS, Piperno DR. Microfossils in calculus demonstrate consumption of plants and cooked foods in Neanderthal diets (Shanidar III, Iraq; Spy I and II, Belgium) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:486–491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016868108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra PH, Wieringa JJ, Smets E, Brandão RD, Lopes JC, Erkens RHJ, Chatrou LW. Correlated evolutionary rates across genomic compartments in Annonaceae. Molec. Phylogenet. Evol. 2017;114:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2017.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker JD, Thomson T. Flora Indica. London: W. Pamplin; 1855. pp. 86–153. [Google Scholar]

- Jussieu, A. L., de. (1789). Genera plantarum. Herissant, Paris.

- Le Bras G, Pignal M, Jeanson ML, Muller S, Aupic C, Carré B, Flament G, Gaudeul M, Gonçalves C, Invernón VR, Jabbour F, Lerat E, Lowry PP, Offroy B, Pimparé EP, Poncy O, Rouhan G, Haevermans T. The French Muséum national d’histoire naturelle vascular plant herbarium collection dataset. Sci. Data. 2017;4:170016. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis GP, Schrire BD, Mackinder BA, Rico L, Clark R. A 2013 linear sequence of legume genera set in a phylogenetic context — a tool for collections management and taxon sampling. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2013;89:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2013.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linnaeus C. Species plantarum. Stockholm: Laurentius Salvius; 1753. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes JC, Chatrou LW, Mello-Silva R, Rudall PJ, Sajo MG. Phylogenomics and evolution of floral traits in the Neotropical tribe Malmeeae (Annonaceae) Molec. Phylogenet. Evol. 2018;118:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2017.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas PJM, Westra LYT, Rainer H, Lobão AQ, Erkens RHJ. An updated index to genera, species, and infraspecific taxa of Neotropical Annonaceae. Nord. J. Bot. 2011;29:257–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-1051.2011.01092.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall CAM, Wieringa JJ, Hawthorne WD. Bioquality hotspots in the tropical African flora. Curr. Biol. 2016;26:3214–3219. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadel D, Danin A, Power RC, Rosen AM, Bocquentin F, Tsatskin A, Rosenberg D, Yeshurun R, Weissbrod L, Rebollo NR, Barzilai O, Boaretto E. Earliest floral grave lining from 13,700 – 11,700-y-old Natufian burials at Raqefet Cave, Mt. Carmel, Israel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:11774–11778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302277110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Rodriguez AE, Ruiz-Sanchez E, Ornelas JF. Phylogenetic relationships among members of the Neotropical clade of Miliuseae (Annonaceae): generic non-monophyly of Desmopsis and Stenanona. Syst. Bot. 2016;41:815–822. doi: 10.1600/036364416X693928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pirie MD, Chatrou LW, Mols JB, Erkens RHJ, Oosterhof J. Andean-centred' genera in the short-branch clade of Annonaceae: testing biogeographical hypotheses using phylogeny reconstruction and molecular dating. J. Biogeogr. 2006;33:31–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01388.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pirie MD, Maas PJM, Wilschut RA, Melchers-Sharrott H, Chatrou LW. Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of South America. Roy. Soc. Open Sci. 2018;5:171561. doi: 10.1098/rsos.171561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power RC, Rosen AM, Nadel D. The economic and ritual utilization of plants at the Raqefet Cave Natufian site: The evidence from phytoliths. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2014;33:49–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2013.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rafinesque CS. Analyse de la nature. Palermo: Aux dépens de l'auteur; 1815. [Google Scholar]

- Rainer, H. & Chatrou, L. W. (2006). AnnonBase: World species list of Annonaceae — version 1.1, 12 Oct 2006 [and updated continuously]. http://www.sp2000.org/ and http://www.annonaceae.org/.

- Schneider JV, Bissiengou P, Amaral MCE, Tahir A, Fay MF, Thines M, Sosef MSM, Zizka G, Chatrou LW. Phylogenetics, ancestral state reconstruction, and a new infrafamilial classification of the pantropical Ochnaceae (Medusagynaceae, Ochnaceae s.str., Quiinaceae) based on five DNA regions. Molec. Phylogenet. Evol. 2014;78:199–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simões AR, Staples G. Dissolution of Convolvulaceae tribe Merremieae and a new classification of the constituent genera. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2017;183:561–586. doi: 10.1093/botlinnean/box007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sosef MSM, Dauby G, Blach-Overgaard A, van der Burgt X, Catarino L, Damen T, Deblauwe V, Dessein S, Dransfield J, Droissart V, Duarte MC, Engledow H, Fadeur G, Figueira R, Gereau RE, Hardy OJ, Harris DJ, de Heij J, Janssens S, Klomberg Y, Ley AC, Mackinder BA, Meerts P, van de Poel JL, Sonké B, Stévart T, Stoffelen P, Svenning J-C, Sepulchre P, Zaiss R, Wieringa JJ, Couvreur TLP. Exploring the floristic diversity of tropical Africa. BMC Biol. 2017;15:15. doi: 10.1186/s12915-017-0356-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stull GW, Johnson DM, Murray NA, Couvreur TLP, Reeger JE, Roy CM. Plastid and seed morphology data support a revised infrageneric classification and an African origin of the pantropical genus Xylopia (Annonaceae) Syst. Bot. 2017;42:211–225. doi: 10.1600/036364417X695484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang CC, Thomas DC, Saunders RMK. Molecular phylogenetics of the species-rich angiosperm genus Goniothalamus (Annonaceae) inferred from nine chloroplast DNA regions: synapomorphies and putative correlated evolutionary changes in fruit and seed morphology. Molec. Phylogenet. Evol. 2015;92:124–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DC, Chatrou LW, Stull GW, Johnson DM, Harris DJ, Thongpairoj U, Saunders RMK. The historical origins of palaeotropical intercontinental disjunctions in the pantropical flowering plant family Annonaceae. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2015;17:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ppees.2014.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DC, Surveswaran S, Xue B, Sankowsky G, Mols JB, Keßler PJA, Saunders RMK. Molecular phylogenetics and historical biogeography of the Meiogyne-Fitzalania clade (Annonaceae): generic paraphyly and late Miocene-Pliocene diversification in Australasia and the Pacific. Taxon. 2012;61:559–575. [Google Scholar]

- Trias-Blasi A, Baker WJ, Haigh AL, Simpson DA, Weber O, Wilkin P. A genus-level phylogenetic linear sequence of monocots. Taxon. 2015;64:552–581. doi: 10.12705/643.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner IM. Notes on the Annonaceae of the Malay Peninsula. Gard. Bull. Singapore. 2016;68:65–69. doi: 10.3850/S2382581216000028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, I. M. (in press). Annonaceae of the Asia-Pacific region: names, types and distributions. Gard. Bull. Singapore.

- Turner IM, Utteridge TMA. A new species and a new combination in Meiogyne (Annonaceae) of New Guinea. Contributions to the Flora of Mt Jaya, XXI. Kew Bull. 2015;70:27. doi: 10.1007/s12225-015-9577-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Heusden ECH. Revision of Haplostichanthus (Annonaceae) Blumea. 1994;39:215–234. [Google Scholar]

- van Heusden ECH. Revision of Meiogyne (Annonaceae) Blumea. 1994;38:487–511. [Google Scholar]

- Wearn JA, Chase MW, Mabberley DJ, Couch C. Utilizing a phylogenetic plant classification for systematic arrangements in botanic gardens and herbaria. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2013;172:127–141. doi: 10.1111/boj.12031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willis CG, Ellwood ER, Primack RB, Davis CC, Pearson KD, Gallinat AS, Yost JM, Nelson G, Mazer SJ, Rossington NL, Sparks TH, Soltis PS. Old plants, new tricks: phenological research using herbarium specimens. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017;32:531–546. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2017.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue B, Liu M-F, Saunders RMK. The nomenclatural demise of Oncodostigma (Annonaceae): the remaining species transferred to Meiogyne. Phytotaxa. 2017;309:297–298. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.309.3.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue B, Su YCF, Thomas DC, Saunders RMK. Pruning the polyphyletic genus Polyalthia (Annonaceae) and resurrecting the genus Monoon. Taxon. 2012;61:1021–1039. [Google Scholar]

- Xue B, Thomas DC, Chaowasku T, Johnson DM, Saunders RMK. Molecular phylogenetic support for the taxonomic merger of Fitzalania and Meiogyne (Annonaceae): new nomenclatural combinations under the conserved name Meiogyne. Syst. Bot. 2014;39:396–404. doi: 10.1600/036364414X680825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]