Abstract

Acute necrotizing esophagitis, also known as “black esophagus,” is typically characterized by a circumferential, friable black mucosal surface and preferentially involves the distal esophagus. It predominantly affects elderly men and presents as an upper gastrointestinal bleed. We describe a 60-year-old man with an acute upper gastrointestinal bleed and sepsis and subsequently acute necrotizing esophagitis.

Keywords: Acute esophageal necrosis, acute necrotizing esophagitis, black esophagus, esophageal infarction, Gurvits syndrome

Acute esophageal necrosis, a rare disorder with an incidence of 0.01% to 0.28%, was first characterized by Goldenberg et al in 1990.1,2 The typical presenting symptom is an upper gastrointestinal bleed.2 It is seen in the elderly with numerous comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and chronic renal insufficiency and demonstrates a male predominance.3 Associated symptoms may include abdominal pain, nausea, low-grade fever, and dysphagia.4

Case report

A 60-year-old white man presented to the emergency room after a presyncopal episode at home. Three days prior to presentation, he reported multiple episodes of nonbloody, loose stools and bilious emesis, which later progressed to hematemesis. The patient denied dysphagia or ingestion of any caustic material. His medical history was significant for colitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, seasonal allergies, and rheumatoid arthritis. His medications included fluticasone 50 mcg one spray daily, aspirin 81 mg once daily, loratadine 10 mg once daily, acetaminophen 500 mg, and prednisone 20 mg oral twice daily for his arthritic pain. He was also a current marijuana user.

He was admitted to the intensive care unit with initial assessment suggesting a septic and hypovolemic shock. He was alert and oriented but appeared to be in mild distress. His general appearance was frail looking with some pallor. He had clear lung sounds bilaterally with nonlabored respirations. His heart rate was 115 beats per minute with blood pressure of 93/55 mm Hg. Peripheral pulses were not palpable. There were no signs of oropharyngeal injury but he had oral thrush at the time of presentation. Abdominal assessment was normal.

Routine labs revealed leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 33,100/mL (normal range 4000–11,000/mL); decreased hemoglobin and hematocrit of 7.3 g/dL and 23.8%, respectively (normal range 13.5–17.5 g/dL and 38.8%–50%); a low albumin of 2.5 g/dL (normal range 3.5–5.5 g/dL); and a low total protein of 5.5 g/dL (normal range 6–8.3 g/dL). Renal function was profoundly abnormal with a glomerular filtration rate of 15.85 mL/min/1.73 m2 (normal 120 mL/min/1.73 m2) consistent with prerenal azotemia. The coagulation panel and complete metabolic panel including liver function tests showed a worsening trend initially along with severe lactic acidosis of 12 mmol/L (normal <2 mmol/L).

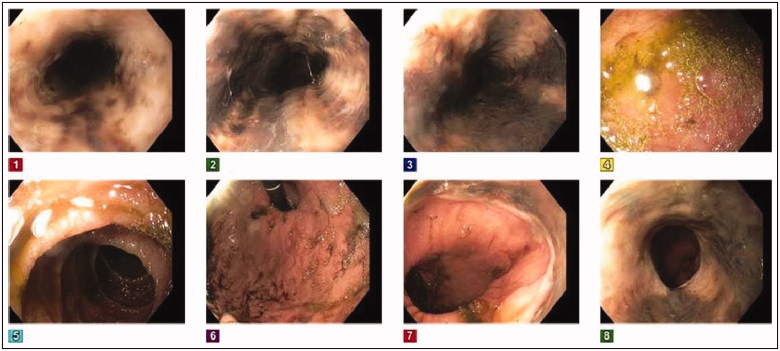

Immediate volume resuscitation, antibiotics, and proton pump inhibitor therapy were initiated. Antigen testing for herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus returned negative. Due to a history of prolonged steroid use and the presence of oral thrush at admission, Candida infection was the primary suspect as the causative agent. The patient was initially started on fluconazole 400 mg empirically and then switched to micafungin 150 mg intravenously every 24 h, after positive cultures from a pelvic abscess showed Candida glabrata. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) evaluation on day 2 of hospitalization revealed ischemic gangrenous esophagitis (Figure 1); candidiasis was thought to be an unlikely source due to lack of pseudomembrane exudates on EGD examination along with a history negative for chest pain and odynophagia. Biopsy was contraindicated based on a high risk of perforation. A gastrografin esophagram was negative for esophageal perforation. Antifungal treatment was then stopped and the patient was diagnosed with ischemic esophagitis, likely due to compromised esophageal perfusion secondary to septic and hypovolemic shock.

Figure 1.

The inital endoscopic appearance showing black esophagus with diffuse and circumferential esophageal necrosis.

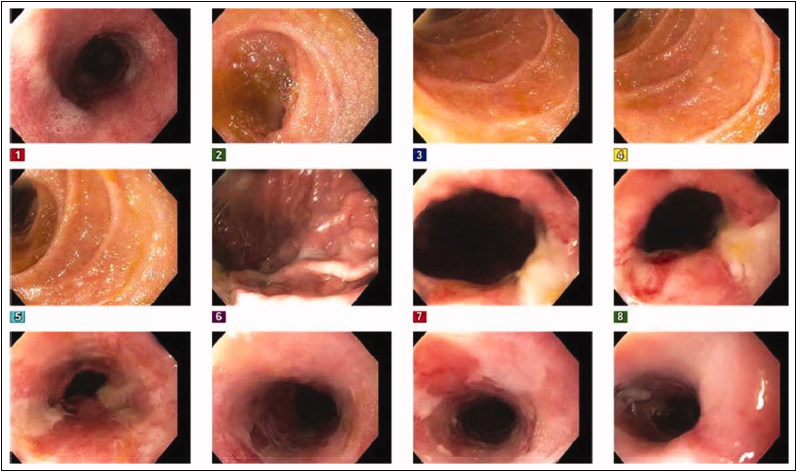

Because the patient could not tolerate oral intake, total parenteral nutrition was initiated. Repeat EGD 2 weeks later showed improvement of the ischemic gangrenous esophagitis (Figure 2). His diet was advanced as tolerated thereafter. Repeat blood work showed normalizing trends, and the patient showed good clinical improvement. The remainder of his hospitalization was uneventful, and he was discharged home after a 4-week stay.

Figure 2.

Follow-up endoscopic image 2 weeks later of the proximal esophagus showing clearing of black color.

Discussion

The primary differential when presented with a case of ischemic esophageal necrosis is an acute caustic ingestion, which should be ruled out by the absence of oropharyngeal injury5 and based on the patient’s history. Other possible causes include broad antibiotic use, herpes infection, gastric volvulus, alcohol abuse, and candidiasis.6–10 The diagnosis is made with an EGD and the finding of a circumferential, friable black mucosal surface with a sharp transition at the Z line.11 Findings may also include white exudates that have a patchy appearance if picked away.5 EGD can help classify the disease into four stages: stage 0, a preliminary stage with still viable esophageal mucosa; stage 1, the peak of the disease with increased necrosis and friability; stage 2, the beginning of healing of the esophagus, with its appearance described as a “checkerboard,” alternating white and black mucosa; and stage 3, the return to normal mucosa.2

A distended stomach and a thickened distal esophagus can be seen on computed tomography imaging.12 Biopsy is generally contraindicated in ischemic esophageal necrosis but if performed may reveal mucosal and submucosal necrosis on histology.11 Leukocytosis, lactic acidosis, and abnormal liver function tests are other common laboratory findings.3 Management is symptomatic and entails treatment of the underlying cause, fluid resuscitation, and proton pump inhibitors.2 Despite appropriate treatment, complications are reported in over 20% of diagnosed patients. These include esophageal strictures, esophageal perforation, mediastinitis, and abscess formation.9 The prognosis is unfortunately poor, with about a 36% mortality rate, usually from septic, cardiogenic, or hypovolemic shock,3,11 and mortality is higher in those with comorbidities.

Although the etiology of acute esophageal necrosis is hypothesized to be multifactorial, vascular compromise seems to be a mainstay.2 The “two-hit” hypothesis describes an initial low flow state due to a vasculopathy or hemodynamic instability that leaves the esophageal mucosal barriers susceptible to gastric acid reflux insults in the setting of gastric outlet obstruction. The esophagus has an intricate vascular supply that is rarely susceptible to ischemia but in the case of the two-hit hypothesis can reveal transient necrosis that will rapidly recover with restoration of flow. The blood supply is distributed among segments of the esophagus, with the distal segment known as a “watershed” area where acute esophageal necrosis tends to be detected. The upper esophagus is supplied by the descending branches of the inferior thyroid arteries. The middle esophagus receives its blood supply from branches off the descending aorta that include the bronchial arteries, right third or fourth intercostal arteries, and esophageal arteries. Lastly, the distal esophagus derives its supply from the branches off the left gastric artery or left inferior phrenic artery. In addition, numerous contributions are derived from surrounding arteries leading to a rich vascular supply.2 This rich arterial connection makes ischemic esophagus necrosis a rare finding.

The age of our patient and his comorbidities, substance abuse, and chronic steroid usage made it a unique and complicated case wherein a detailed differential and workup was paramount. This case report illustrates that a thorough history, a high level of suspicion, and prompt treatment for ischemic esophagitis are key to a positive outcome. The ischemic esophagitis in this patient was proposed to be related to hypovolemic shock that compromised blood flow to the esophagus.

References

- 1.Goldenberg SP, Wain SL, Marignani P. Acute necrotizing esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:493–496. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90844-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurvits GE. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3219–3225. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i26.3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurvits GE, Shapsis A, Lau N, Gualtieri N, Robilotti JG. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:29–38. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1974-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimura Y, Seno H, Yamashita Y. A case of acute necrotizing esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:525–526. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Day A, Sayegh M. Acute oesophageal necrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg. 2010;8:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mangan TF, Colley AT, Wytock DH. Antibiotic-associated acute necrotizing esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:900. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90997-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cattan P, Cuillerier E, Cellier C, et al. Black esophagus associated with herpes esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:105–107. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(99)70455-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kram M, Gorenstein L, Eisen D, Cohen D. Acute esophageal necrosis associated with gastric volvulus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:610–612. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(00)70304-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Endo T, Sakamoto J, Sato K, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis caused by alcohol abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5568–5570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YH, Choi SY. Black esophagus with concomitant candidiasis developed after diabetic ketoacidosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5662–5663. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i42.5662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watermeyer GA, Shaw JM, Krige JE. Education imaging gastrointestinal: acute necrotizing esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonaldi M, Sala C, Mariani P, Fratus G, Novellino L. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis, clinical case and review of literature. J Surg Case Rep. 2017;2017. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjx037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]