Abstract

Background & Aims

A high proportion of patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) respond to placebo in clinical trials (estimated at about 40%). We aimed to identify factors that contribute to the high placebo response rate using data from a placebo-controlled trials of patients with IBS.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of 599 women with IBS with constipation who were in the placebo group of a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial of the experimental medication renzapride. Primary analyses evaluated frequency of abdominal pain in patients who received placebo, defined as ≥ 30% pain improvement from baseline for ≥6 of the 12 study weeks. We performed backward elimination regression with bootstrapping to identify factors associated with response to placebo.

Results

In the placebo group, 29.0% of the patients had an abdominal pain response. Factors associated with a response to placebo were baseline variation in abdominal pain (odds ratio [OR], 1.71), maximum baseline pain severity (OR, 1.34), and placebo response in study week 2 (OR, 2.23) or week 3 (OR, 3.69). Factors associated with lack of response to placebo were number of baseline complete spontaneous bowel movements (OR, 0.73; P=.019) and final baseline pain ratings (OR, 0.73; P<.001).

Conclusion

We identified factors associated with a response in abdominal pain to placebo using original data from an IBS clinical trial. Baseline factors associated with the placebo response in women with IBS and constipation include variation in baseline pain symptoms, severity of baseline symptoms, and early improvement of abdominal pain. These findings have significant implications for clinical trial design.

Keywords: CSBM, IBS-C, predict, outcome

Introduction

The use of placebos as a research control has been the gold-standard in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) since the mid-twentieth century1. By current standards, treatment is considered effective if proven to be superior to placebo. However, placebo-response rates vary2. For example, conditions associated with patient-reported symptom severity without reliable physiologic correlates, such as chronic pain disorders, mental illnesses, and functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), are known to have high placebo response rates when compared to diseases measured with objective endpoints3,4. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the magnitude of the placebo response might be increasing over time 5–7, necessitating larger sample sizes to demonstrate efficacy of experimental therapies.

The high placebo response rate in Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) has garnered increasing attention over the years 8. Estimates of the placebo response rate in IBS range between 15%–72% with pooled response rates of approximately 40%9–11. Several systematic reviews have attempted to identify predictors of placebo response in randomized controlled IBS drug trials, but have produced conflicting results. For example, while some reviews have found that more frequent study visits and longer study duration are associated with higher placebo response rates10, others suggest that fewer visits and shorter study duration predict higher placebo response9,11. In 2008, Kaptchuk et al tested components of the placebo effect in IBS and concluded that the placebo response rate could be enhanced through contextual factors (e.g. a warm patient-practitioner interaction compared to a neutral interaction)12.

To our knowledge, no study to-date has evaluated specific clinical predictors of the placebo response using original data from a placebo-controlled drug trial in IBS. A recent evaluation of 75 systematic reviews and meta-analyses performed in a range of medical specialties, found that younger age was a predictor of placebo response in some medical specialties, but not in IBS, and that female gender was not associated with higher placebo response rate in IBS or in the combined analysis of all conditions13. This same evaluation also noted that lower symptom severity at baseline, more recently performed studies, and study designs with a greater likelihood of receiving active treatment were all associated with higher placebo response rates in the combined analysis across medical conditions13. Not enough data were available for individual analysis of these variables in IBS specifically. Similarly, in a sample of 220 patients with Functional Dyspepsia who received placebo as part of a clinical trial, age and gender were not associated with placebo response14.

The aim of the current study is to evaluate specific clinical predictors of the placebo response in a large sample of patients with IBS with constipation (IBS-C) receiving placebo as part of a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, Phase III clinical trial 15.

Methods

Study sample

Patients recieving placebo as part of a Phase III clinical trial with the experimental medication renzapride, a 5-hydroxytryptamine type-4, 5-HT4 receptor agonist and 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, were included in the current analysis. The larger trial was a multicenter study conducted at 201 secondary and teriary care centers in five countries (US, Argentina, Canada, Columbia, and Chile) in which women with IBS-C were randomized to renzapride 4mg, 2mg, or placebo for 12 weeks. Inclusion criteria included women ages 18 and older who met Rome II criteria for IBS-C and who reported at least moderate symptoms (defined as having at least mild symptoms on ‘most’ (self-reported) of the baseline days) during the 2-week baseline period. Subjects were excluded if they reported recurrent diarrhea, history of abdominal surgery, were pregnant/lactating, or had ‘alarm features’. Additional inclusion/exclusion criteria are described elsewhere15.

Responder criteria

Abdominal pain placebo response

In accordance with FDA-recommended criteria, we used abdominal pain placebo response as our primary endpoint16. For the purpose of this study, abdominal pain placebo responders were classified using the criteria of ≥ 30% improvement from baseline in the average weekly abdominal pain scores for at least 6 of the 12 study weeks. Abdominal pain was measured daily utilizing the following question: On a scale of 1 to 10 (with 1 representing no pain and 10 representing the worst possible pain), how would you describe any abdominal pain/discomfort you experienced today?”. Weekly abdominal pain scores were calculated for each participant using the average of 7 daily pain scores.

Adequate relief and Complete Spontaneous Bowel Movements (CSBMs)

In secondary analyses, we evaluated responder status using adequate relief and CSBM definitions. Adequate relief of abdominal pain was measured as a dichotomous variable (yes/no) at the end of every study week. Patients were asked “Have you experienced adequate relief of your abdominal pain/discomfort during the past week?”. Patients who reported ‘adequate relief’ for at least 6 out of the 12 weeks of the treatment period were considered to be adequate relief placebo responders.

CSBMs were measured by first asking about daily Spontaneous Bowel Movements (SBMs), defined as bowel movements occurring in the absence of laxative or enema use and then identifying how many of the SBMs were associated with “a feeling of complete evacuation”. A patient who reported an increase of ≥1 CSBM per week compared to baseline for at least 6 out of the 12 weeks of the treatment period was considered to be a CSBM placebo responder.

Demographics and baseline variables

Demographic variables included age, gender (all female), race, and duration of IBS in months. Other baseline variables included IBS-Quality of Life (QOL)17; baseline variability in reported pain over 2 weeks (defined by the standard deviation of the average daily pain scores during the 2 week baseline period), self-reported history of anxiety or depression; and concurrent medical illnesses (seasonal allergies, migraines, headaches, insomnia, dyspepsia, hypothyroidism, back pain, asthma, drug hypersensitivity, hypertension, myopia, anemia, and endometriosis). Additional information about methods and data collection, including a study flow-chart describing enrollment and allocation, is provided in a previously published paper 15, a complete list of variables is included in Appendix 1.

Statistics

Data were stored and analyzed using STATA software version 14.2 (College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to report mean pain scores, mean CSBMs, and responder frequency. Notably, there were a significant number of subjects with missing adequate relief data and, thus, our sample size for adequate relief analyses was smaller (n=443) than our sample size for the other variables (n=599). Even with a conservative sample size of 443, however, all analyses were adequately powered at 28 potential predictors.

Separate analyses were run to evaluate 3 dependent variables (DV): 1) abdominal pain placebo response; 2) adequate relief placebo response; and 3) CSBM placebo response. For each DV, we first ran univariate logistic regression models to evaluate unadjusted associations. Twenty-eight independent variables (IV) were entered into the regression model to evaluate predictors of the placebo response. These variables included: age, QOL, baseline pain scores, baseline bowel movements frequency (CSBMs and SBMs), pain scores for weeks 1–3, mood scores, and medical comorbidities (appendix 1). Next, we employed backwards elimination regression models with bootstrapping to reduce the number of IVs. “Bootstrapping” is a non-parametric method of estimating statistical parameters by means of continued resampling of the empirical sample, and was utilised to increase the robustness of model results and decrease the chance of type 1 errors. The variables that remained significant in >50% of the 500 bootstrapped samples were kept and entered in to a final multivariable logistic regression model.

Results

A total of 599 women with IBS-C were randomized to receive placebo as part of the phase III clinical trial15. Mean age was 43.6 years (range 18–65) and 79% were White. Median duration of IBS-C symptoms was 49 months.

Abdominal pain placebo response

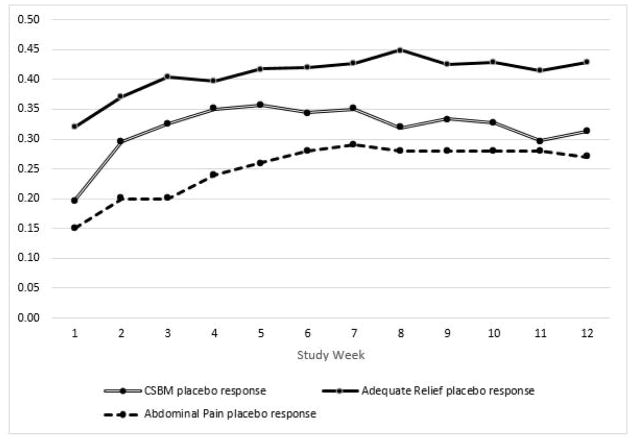

Overall, 29.0% percent of the women with IBS-C receiving placebo were abdominal pain placebo responders (i.e., reported ≥ 30% improvement from baseline in the average weekly abdominal pain score for at least 6 of the 12 weeks of the treatment period). Between 15–25% of the women with IBS-C were weekly responders in any given week. Notably, 47% of the sample did not meet abdominal pain response criteria in any of the 12 study weeks, though all participants were included in the analyses. Figure 1 shows weekly trends in abdominal pain response to placebo.

Figure 1.

Proportion of participants reporting placebo response in each week

Predictors of the abdominal pain placebo response

In univariate analysis, factors associated with an increased likelihood of abdominal pain placebo response included higher QOL scores, higher variability of baseline abdominal pain severity, higher maximum baseline pain severity, and reported abdominal pain relief in week 2 or in week 3. Higher final baseline pain severity (i.e. the pain severity score recorded on the final day of baseline measurement) was associated with a decreased likelihood of abdominal pain placebo response (table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate predictors of placebo response (abdominal pain response; adequate relief response; and CSBM response)

| Abdominal pain placebo response N=599 |

Adequate relief placebo response N=443 |

CSBM placebo response N=599 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio |

|

| |||

| Age | .99 (p=.093) | 1.00 (p=.602) | 1.01 (p=.195) |

|

| |||

| Quality of Life | 1.01 (p=.011) | 1.00 (p=.768) | 1.00 (p=.174) |

|

| |||

| Baseline Pain | .98 (p=.712) | 0.91 (p=.060) | 0.96 (p=.394) |

|

| |||

| Variability in Baseline Pain | 2.40 (p<.001) | 1.18 (p=.366) | 1.07 (p=.692) |

|

| |||

| Baseline # CSBM | .98 (p=.403) | 1.90 (p<.001) | 1.18 (p=.111) |

|

| |||

| Baseline # Bms | 1.00 (p=.961) | 1.06 (p=.071) | 1.02 (p=.511) |

|

| |||

| Variability in baseline BMs | 1.02 (p=.610) | 1.05 (p=.266) | 1.09 (p=.051) |

|

| |||

| Max baseline pain | 1.16 (p=.001) | 0.98 (p=.599) | 0.96 (p=.359) |

|

| |||

| Last recorded baseline pain score | .896 (p=.006) | 0.90 (p=.014) | 0.94 (p=.123) |

|

| |||

| Pain relief week 1 | 1.22 (p=.817) | 3.93 (p=.237) | 1.08 (p=.932) |

|

| |||

| Pain relief week 2 | 3.42 (p<.001) | 13.09 (p<.001) | 2.74 (p<.001) |

|

| |||

| Pain relief week 3 | 4.69 (p<.001) | 12.86 (p<.001) | 3.86 (p<.001) |

|

| |||

| No. of comorbidities | 1.01 (p=.907) | 0.87 (p=.015) | 1.04 (p=.446) |

|

| |||

| Self-reported history of: | |||

|

| |||

| Anxiety | 1.06 (p=.817) | 1.01 (p=.962) | 0.70 (p=.178) |

|

| |||

| Depression | 1.21 (p=.368) | 0.80 (p=.343) | 0.90 (p=.608) |

|

| |||

| Allergies | 1.00 (p=.985) | 0.79 (p=.327) | 0.76 (p=.258) |

|

| |||

| Migraine | 1.05 (p=.841) | 0.74 (p=.251) | 1.20 (p=.442) |

|

| |||

| Headache | 1.70 (p=.757) | 0.75 (p=.247) | 1.56 (p=.031) |

|

| |||

| Insomnia | .83 (p=.488) | 0.77 (p=.345) | 1.14 (p=.608) |

|

| |||

| Dyspepsia | .83 (p=.514) | 0.83 (p=.556) | 1.14 (p=.624) |

|

| |||

| Hypertension | .677 (p=.205) | 0.90 (p=.744) | 1.06 (p=.835) |

|

| |||

| Back pain | .668 (p=.254) | 0.29 (p=.003) | 1.23 (p=.498) |

|

| |||

| Asthma | 1.32 (p=.293) | 0.97 (p=.922) | 1.18 (p=.566) |

|

| |||

| Drug hypersensitivity | 1.22 (p=.374) | 0.55 (p=.022) | 1.10 (p=.681) |

|

| |||

| Hypertension | 1.07 (p=.763) | 1.37 (p=.208) | 1.22 (p=.396) |

|

| |||

| Myopia | 1.05 (p=.877) | 0.57 (p=.123) | 1.12 (p=.718) |

|

| |||

| Anemia | .936 (p=.863) | 1.02 (p=.964) | 1.58 (p=.189) |

|

| |||

| Endometriosis | .869 (p=.790) | 0.31 (p=.075) | 0.25 (p=.062) |

In multivariate regression, factors that predicted an increased likelihood of abdominal pain placebo response included greater baseline variability of abdominal pain severity (OR=1.71, p=0.016), higher maximum baseline pain severity (OR=1.34, p<0.001) and experiencing a placebo response in week 2 (OR=2.23, p<0.001) or week 3 (OR=3.69, p<0.001). Factors that predicted a decreased likelihood of abdominal pain placebo response were greater number of baseline CSBMs (OR=0.73, p=0.019) and higher final baseline pain severity (OR=0.73, p<0.001), Table 2.

Table 2.

Multivariate predictors of placebo response (abdominal pain response; adequate relief response; and CSBM response) after backwards regression with bootstrapping

| Analysis 1: Predictors of abdominal pain placebo response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | SE | P | 95% CI | |

| ≥30% pain reduction week 2 | 2.23 | 0.508 | <0.001 | 1.43–3.49 |

| ≥30% pain reduction week 3 | 3.69 | 0.839 | <0.001 | 2.36–5.76 |

| Baseline pain variability | 1.71 | 0.379 | 0.016 | 1.11–2.64 |

| Maximum baseline pain rating | 1.34 | 0.098 | <0.001 | 1.16–1.54 |

| QOL | 1.01 | 0.004 | 0.029 | 1.00–1.16 |

| Baseline # CSBMs | 0.73 | 0.099 | 0.019 | 0.55–0.95 |

| Final baseline pain rating | 0.73 | 0.045 | <0.001 | 0.65–0.82 |

| Analysis 2: Predictors of adequate relief placebo response | ||||

| OR | SE | P | 95% CI | |

| ≥30% pain reduction week 2 | 7.70 | 2.17 | <0.001 | 4.43–13.38 |

| ≥30% pain reduction week 3 | 7.53 | 2.01 | <0.001 | 4.46–12.71 |

| Baseline # CSBMs | 1.70 | 0.266 | 0.001 | 1.25–2.31 |

| History of back pain | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.10–0.73 |

| Analysis 3: Predictors of CSBM placebo response | ||||

| OR | SE | P | 95% CI | |

| ≥30% pain reduction week 2 | 1.81 | 0.37 | 0.004 | 1.21–2.70 |

| ≥30% pain reduction week 3 | 3.11 | 0.64 | <0.001 | 2.08–4.66 |

| History of headache | 1.84 | 0.41 | 0.006 | 1.19–2.84 |

Adequate relief placebo response

43.6% of patients were adequate relief placebo responders (i.e. patients reporting adequate relief for at least 6 weeks). Figure 1 shows weekly trends of participants reporting adequate relief over the course of the study. Between 30–45% of the women with IBS-C were weekly adequate relief placebo responders in any given week. 21% of the sample did not meet adequate relief response criteria in any of the 12 study weeks.

Predictors of adequate relief placebo response

In univariate analysis, factors associated with an increased likelihood of adequate relief placebo response included more CSBMs at baseline and reported abdominal pain relief in weeks 2 or 3. Factors associated with decreased likelihood of adequate relief placebo response included higher final baseline pain rating, a reported history of back pain, reported history of drug hypersensitivity, and higher number of reported medical comorbidities (Table 1).

In multivariate regression, patients were significantly more likely to be adequate relief responders if they reported pain relief in week 2 (OR=7.70), pain relief in week 3 (OR=7.53), or higher CSBMs at baseline (OR=1.70). A reported history of back pain was associated with a decreased likelihood of adequate relief placebo response (OR=0.27; Table 2).

CSBM placebo response

31.7% of the sample met CSBM placebo responder criteria (i.e. patients reporting ≥1 additional CSBM compared to baseline for at least 6 weeks). Between 20–36% of the sample were weekly CSBM placebo responders in any given week. 28.7% of the sample did not meet CSBM response criteria in any of the 12 study weeks. Figure 1 shows weekly trends of participants reporting CSBM relief over the course of the study. Mean weekly number of CSBMs significantly decreased from baseline to Week 12 (Mbaseline = 0.66, SD = 0.84; M12 = 1.32, SD = 1.84; t(598) = −9.19, p<.001).

Predictors of CSBM placebo response

In univariate analysis, factors associated with an increased likelihood of CSBM placebo response included reported abdominal pain relief in weeks 2 or 3 and a reported history of headaches. No factors were significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of CSBM placebo response (table 1).

In multivariate regression, patients were significantly more likely to be CSBM placebo responders if they experienced early pain relief in week 2 (OR=1.81), early pain relief in week 3 (OR=3.11), or if they reported a history of headaches (OR=1.84; Table 2).

Discussion

This study reports specific clinical predictors of the placebo response in an IBS clinical trial. Our findings suggest that the strongest predictors of placebo response in women with IBS-C were early improvement of abdominal pain (i.e., weeks 2 or 3), increased variability in baseline pain symptoms, and increased severity of baseline symptoms.

The most consistent predictor of placebo response in this study was early reported pain relief (in weeks 2 or 3). Although our primary outcome in this study was “abdominal pain placebo response”, early pain relief was the most consistent predictor for all of the responder definitions evaluated in this study including adequate relief placebo response and CSBM placebo response. This finding is consistent with the results of a recent study evaluating early response to eluxadoline in diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) patients, which mentioned en passant that early response to placebo predicted sustained response to both placebo. Specifically, 77.2% of patients taking placebo who responded within the first 4 weeks maintained the placebo response over 3 months and 66.3% of early responders maintained placebo response over 6 months (compared to 8.1% and 12.9% of patients who did not respond to placebo in the first 4 weeks)18.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report baseline symptom variability or severity as predictors of the placebo response in a GI population. Our findings regarding baseline pain variability as a predictor of abdominal pain placebo response is consistent with a recent analysis of 12 clinical trials in neuropathic pain, which revealed that increased variability in 7-day baseline pain diaries predicted response to placebo, but not to active medications19. Similarly, a trial evaluating pain variability in fibromyalgia in 2005 reported that greater baseline variability in pain predicted response to placebo but not to an active drug20. Although it is not yet clear why baseline variability in pain might differentially predict the pain placebo response, Farrar et al have suggested that this may be due to the overlap between mind-body factors and physiologic pain-reduction pathways19. Interestingly, baseline pain variability was only a predictor of our primary endpoint, abdominal pain placebo response, and was not a predictor of adequate relief response or of CSBM response, suggesting that this finding may be unique to symptoms of pain.

Similarly, our findings that baseline symptom severity predicted placebo response only applied to our primary outcome of abdominal pain. In our study, the abdominal pain placebo response was predicted by higher maximum baseline pain scores and fewer baseline CSBMs. Available literature regarding the association between baseline symptom severity and placebo response is mixed. A previous study evaluating predictors of placebo response in Functional Dyspepsia did not find any association between baseline symptom severity and response to placebo14. One analysis of 75 meta-analyses across 6 diverse disease groups (including 12 papers in gastroenterology) found that lower symptom severity at baseline predicted higher placebo response13, which is in contrast to the results of the current study. Interestingly, placebo research in autism21 and depression22–24 have suggested that lower baseline symptom burden may be associated with higher placebo response rates, while research in chronic neuropathic pain25 and bipolar disorder26 have found higher baseline pain scores to be associated with higher placebo response. Our findings may be influenced by the study design in which patients submitted daily symptom ratings for a 2-week, no-treatment baseline period prior to randomization, which may have provided more robust baseline data than is typically available in clinical trials. Furthermore, the inconsistent literature regarding baseline symptom severity as a predictor of placebo response may be better explained by our finding that baseline symptom variability was a significant predictor of placebo response. This possibility is supported by our finding that both higher maximum baseline pain as well as lower pain scores on the final day of baseline period predicted abdominal pain placebo responders.

Other factors that were significantly associated with placebo response included higher QOL scores, which predicted increased likelihood of abdominal pain placebo response; self-reported history of back pain, which predicted decreased likelihood of adequate relief placebo response; and self-reported history of headache, which predicted increased likelihood of CSBM placebo response.

It is noteworthy that several factors were significant in the Adequate Relief univariate analyses that did not maintain significance in the multivariate analyses. While the univariate analyses must be interpreted with caution because they do not account for correlations between individual predictors, our univariate analyses revealed that patient-reported hypersensitivity to medications and higher number of medical comorbidities were both associated with a decreased likelihood to report adequate relief placebo response. These, combined with multivariate findings that history of back pain was also associated with a lower likelihood of adequate relief placebo response might suggest that using adequate relief as a global endpoint may be influenced by centrally mediated mechanisms such as hypersensitivity or hypervigilance to pain and other physical symptoms. Based on our findings, it is possible that patients with more central sensitization could be less likely to meet adequate relief criteria in the placebo arm of an IBS study.

The results of this study have implications for clinical trial design in IBS. Based on our findings and other available research suggesting that baseline variability is a predictor of placebo response but not drug response 19,20, it is possible that removing patients with high pain variability during baseline monitoring or stratifying randomization by baseline pain variability could reduce the placebo effect while maintaining the drug effect. This may be especially relevant in light of recent research that has suggested that the magnitude of the placebo response is increasing over time, especially in conditions known to have high placebo response rates5–7. Of course, this requires further retrospective and even prospective replication and verification. Our findings regarding early response to placebo as a predictor of placebo response at the end of the study may also support the use of run-in periods to eliminate patients who respond early to placebo. However, early response to active medication is also associated with sustained response to treatment in IBS 18 and the only study in IBS to prospectively investigate the efficacy of a run-in period (testing acupuncture) did not find any differences when eliminating versus keeping run-in responders27. Caution is warranted concerning placebo run-in efficacy given that prospective and retrospective studies on the efficiency of the placebo run-in to detect drug-placebo differences have not been consistently successful28–30. It is possible that eliminating placebo responders during the run-in would also eliminate significant numbers of medication responders.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design, as our analyses were based on previously collected clinical trial data15. In this study, the abdominal pain placebo response rate (our primary endpoint) was approximately 29%, which is lower than the pooled response rate estimates for placebo in IBS of approximately 40%. Previously suggested explanations for the low abdominal pain placebo response rate in this study include that this study included a selected research population and lower frequency of study visits15. It is possible that our findings may have been different in a sample with a higher placebo response rate. Related to the previous point, the current study is also limited by the fact that it did not measure behavioral and psychobiological factors (e.g. conditioning and expectancy) that are associated with the placebo response31,32, nor did it measure contextual factors (e.g. the therapeutic relationship and confidence in the treatment)12,33. These factors have been shown in multiple studies to be meaningful predictors of the placebo response. However, such behavioral, contextual, and psychobiological variables are not routinely collected in randomized controlled drug trials and, unfortunately, were not available as part of this dataset.

Another limitation is regarding certain baseline demographic variables that were used in our models. For example, patient histories of medical and mental health comorbidities were all based on self-report and were not measured using validated questionnaires. Finally, the results of this study are limited only to women with IBS-C and we cannot generalize these findings to men or to subjects with other subtypes of IBS. The data evaluating sex differences in the placebo response is inconclusive. One recent systematic review found that men responded more strongly to placebo compared to women34, while another review reported no difference in placebo respond between men and women13.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This project was funded in part by NIH/NIDDK grant # T32DK007760 (SB) and NIH/NCCIH grant # R01-AT008573 (AL, TK).

Abbreviations

- IBS

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- SBM

spontaneous bowel movement

- CSBM

complete spontaneous bowel movement

- QOL

quality of life

- DV

dependent variable

- IV

independent variable

- OR

odds ratio

Appendix 1. List of variables entered into multiple regression model

| Age |

| Quality of Life |

| Baseline pain |

| Maximum pain measured at baseline |

| Variability in baseline pain |

| Final measured pain score (last day of baseline monitoring) |

| Pain Relief |

| Pain relief reported in week 1 |

| Pain relief reported in week 2 |

| Pain relief reported in week 3 |

| Baseline bowel movements |

| Mean number of BMs |

| Mean number of CSBMs |

| Variability in number of BMs |

| Mental health |

| Anxiety |

| Depression |

| Medical comorbidities |

| Seasonal allergies |

| Migraines |

| Headache |

| Insomnia |

| Dyspepsia |

| Hypothyroidism |

| Back pain |

| Asthma |

| Drug hypersensitivity |

| Hypertension |

| Myopia |

| Anemia |

| Endometriosis |

| Total number of medical comorbidities |

Footnotes

Disclosures: none

Author Contributions: The idea for the article was conceived by AL, AB, SB, TK, and MJ. The manuscript was drafted by SB. Statistical analysis was performed by AB and MJ. The draft manuscript was critically reviewed by AL, MJ, AB, TJK, WH, TS, JN, JI, PS, and VR. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kaptchuk TJ. Intentional ignorance: a history of blind assessment and placebo controls in medicine. Bull Hist Med. 1998;72:389–433. doi: 10.1353/bhm.1998.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Straus JL, von Ammon Cavanaugh S. Placebo effects. Issues for clinical practice in psychiatry and medicine. Psychosomatics. 1996;37:315–326. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(96)71544-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaptchuk TJ, Miller FG. Placebo Effects in Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:8–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1504023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wechsler ME, Kelley JM, Boyd IOE, et al. Active albuterol or placebo, sham acupuncture, or no intervention in asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:119–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuttle AH, Tohyama S, Ramsay T, et al. Increasing placebo responses over time in U.S. clinical trials of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2015;156:2616–2626. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan A, Fahl Mar K, Brown WA. Does the increasing placebo response impact outcomes of adult and pediatric ADHD clinical trials? Data from the US Food and Drug Administration 2000–2009. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;94:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dold M, Kasper S. Increasing placebo response in antipsychotic trials: a clinical perspective. Evid Based Ment Health. 2015;18:77–79. doi: 10.1136/eb-2015-102098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah E, Pimentel M. Placebo effect in clinical trial design for irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20:163–170. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2014.20.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorn SD, Kaptchuk TJ, Park JB, et al. A meta-analysis of the placebo response in complementary and alternative medicine trials of irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil Off J Eur Gastrointest Motil Soc. 2007;19:630–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel SM, Stason WB, Legedza A, et al. The placebo effect in irritable bowel syndrome trials: a meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil Off J Eur Gastrointest Motil Soc. 2005;17:332–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford AC, Moayyedi P. Meta-analysis: factors affecting placebo response rate in the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:144–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Conboy LA, et al. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ. 2008;336:999–1003. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39524.439618.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weimer K, Colloca L, Enck P. Age and sex as moderators of the placebo response – an evaluation of systematic reviews and meta-analyses across medicine. Gerontology. 2015;61:97–108. doi: 10.1159/000365248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talley NJ, Locke GR, Lahr BD, et al. Predictors of the placebo response in functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:923–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lembo AJ, Cremonini F, Meyers N, et al. Clinical trial: renzapride treatment of women with irritable bowel syndrome and constipation - a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:979–990. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: Irritable bowel syndrome-clinical evaluation of drugs for treatment. 2012 http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM205269.pdf.

- 17.Patrick DL, Drossman DA, Frederick IO, et al. Quality of life in persons with irritable bowel syndrome: development and validation of a new measure. Dig Sci. 1998;43:400–411. doi: 10.1023/a:1018831127942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chey WD, Dove LS, Andrae DA, et al. Early response predicts a sustained response to eluxadoline in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea in two Phase 3 studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:1319–1328. doi: 10.1111/apt.14031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrar JT, Troxel AB, Haynes K, et al. Effect of variability in the 7-day baseline pain diary on the assay sensitivity of neuropathic pain randomized clinical trials: An ACTTION study. PAIN®. 2014;155:1622–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris RE, Williams DA, McLean SA, et al. Characterization and consequences of pain variability in individuals with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3670–3674. doi: 10.1002/art.21407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King BH, Dukes K, Donnelly CL, et al. Baseline Factors Predicting Placebo Response to Treatment in Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorders. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:1045–1052. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bridge JA, Birmaher B, Iyengar S, et al. Placebo response in randomized controlled trials of antidepressants for pediatric major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:42–49. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen D, Consoli A, Bodeau N, et al. Predictors of placebo response in randomized controlled trials of psychotropic drugs for children and adolescents with internalizing disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20:39–47. doi: 10.1089/cap.2009.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown WA, Johnson MF, Chen MG. Clinical features of depressed patients who do and do not improve with placebo. Psychiatry Res. 1992;41:203–214. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90002-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman R, Emir B, Parsons B. Predictors of placebo response in peripheral neuropathic pain: insights from pregabalin clinical trials. J Pain Res. 2015;8:257–268. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S78303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nierenberg AA, Østergaard SD, Iovieno N, et al. Predictors of placebo response in bipolar depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30:59–66. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lembo AJ, Conboy L, Kelley JM, et al. A treatment trial of acupuncture in IBS patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1489–1497. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Walker JR, Jakul L, et al. Does elimination of placebo responders in a placebo run-in increase the treatment effect in randomized clinical trials? A meta-analytic evaluation Depress Anxiety. 2004;19:10–19. doi: 10.1002/da.10134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faries DE, Heiligenstein JH, Tollefson GD, et al. The double-blind variable placebo lead-in period: results from two antidepressant clinical trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:561–568. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trivedi MH, Rush H. Does a placebo run-in or a placebo treatment cell affect the efficacy of antidepressant medications? Neuropsychopharmacol Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 1994;11:33–43. doi: 10.1038/npp.1994.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voudouris NJ, Peck CL, Coleman G. The role of conditioning and verbal expectancy in the placebo response. Pain. 1990;43:121–128. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90057-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Enck P, Klosterhalfen S. The placebo response in functional bowel disorders: perspectives and putative mechanisms. Neurogastroenterol Motil Off J Eur Gastrointest Motil Soc. 2005;17:325–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weinland SR, Morris CB, Dalton C, et al. Cognitive factors affect treatment response to medical and psychological treatments in functional bowel disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1397–1406. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vambheim SM, Flaten MA. A systematic review of sex differences in the placebo and the nocebo effect. J Pain Res. 2017;10:1831–1839. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S134745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]