Summary:

Capsular contracture is a frequent complication of breast augmentation and reconstruction that affects up to 30% of patients. The authors describe the effect of fat grafting on capsular contracture used in cases with the primary intention of improving soft-tissue characteristics before implant to implant or implant to fat exchange. Fifteen patients (18 breasts) with capsular contracture Baker grade 4 were reviewed. Pain from capsular formation was able to be ameliorated in all cases after lipofilling sessions, with 11 of them achieving analgesia. Afterward, 4 patients underwent implant to implant and 7 patients implant to fat exchange. Four patients chose to keep the implants after the end of fat grafting procedures, due to satisfying cosmetic results and excellent pain management. Fat grafting may be a useful addition to therapies currently used to treat capsular contracture.

One of the most common causes of reoperation after breast augmentation or implant-based reconstruction is capsular contraction, with a prevalence of 0.5–30%.1 It seems that the problem is multifactorial, leading to a variety of treatments, while scientists are continually in search of new substances to influence the capsule formation.2,3 In our retrospective study, we report the effect of fat grafting on patients who had a capsule contracture but were treated primarily with the intention of restoring thickness to the soft-tissue envelope and finally exchanging the implant with fat or with another implant.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The present study has been conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. A retrospective review was performed to identify patients who had been treated due to capsular contracture grade Baker 4 from 2013 to 2017, with the goal of exchanging the implant with a new one or totally replacing the implant with fat. In the first group, due to the thinness of the parenchyma, fat grafting was performed to strengthen the entire skin envelope and to treat deformities. In the second group, serial lipofilling sessions were conducted that increased the volume of the treated breast. After completion, the implant was removed and the remaining breast was reshaped. Patient demographic information, history of capsular contracture and previous treatments, surgical indication, placement of implant, pain sensation, and postoperative complications were recorded (Table 1). Before and after the operations, we asked the patients to quantify the pain using the Numerical Rating Scale (Table 2), which has been proven a very reliable measure of pain intensity.4 In our series, we used the Body-Jet (Human Med, Schwerin, Germany) technique, which combines water-jet-assisted liposuction, purification and grafting.5 Regarding the fat transfer, subpectoral and epipectoral cases were treated in the same way without direct visualization of the capsule. Before the operations, ultrasound assessment of the tissue envelope was performed. Once an overview of the thickness was obtained, efforts were concentrated to position the fat on the capsule.

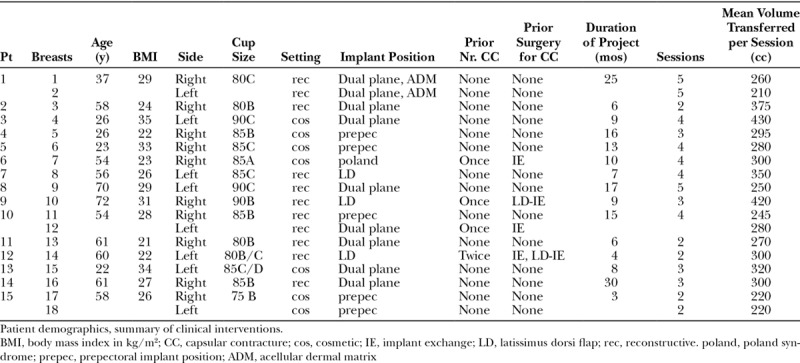

Table 1.

Patients' Demographics with Baker 4 Grade Capsular Contracture

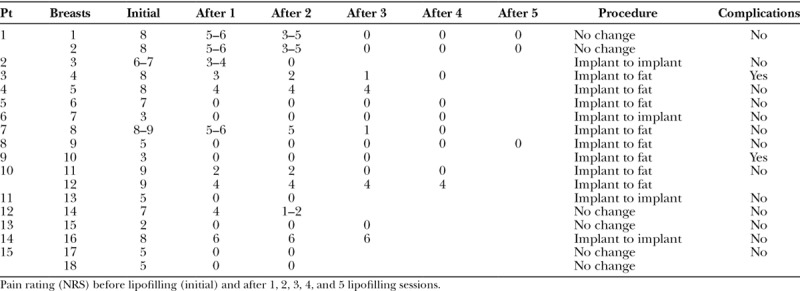

Table 2.

Pain Development and Complications

RESULTS

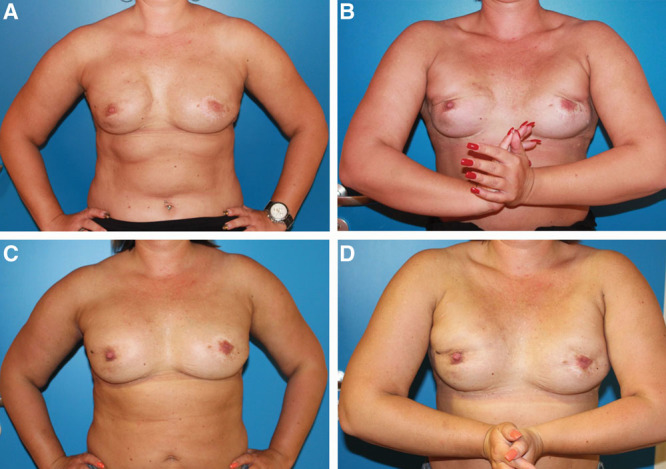

Fifteen patients (18 breasts) were reviewed. Ten patients (13 breasts) had undergone surgery for postmastectomy implant-based reconstruction and 5 (5 breasts) for aesthetic indications, Poland syndrome and anisomastia. Four patients underwent implant to implant and 7 patients implant to fat exchange. Four patients chose to keep the implants after the end of fat grafting procedures, due to satisfying cosmetic results and excellent pain management (Fig. 1). In all cases, it was possible to ameliorate pain from capsular formation. Two of the 8 patients with subpectoral/dual plane, 1 of the 4 patients with subglandular implant position and 1 of the 3 patients with implant under the latissimus dorsi could not achieve analgesia, but, at the end of the fat grafting sessions, experienced significant pain reduction, which translated into an improved quality of life (eg, they could again exercise or sleep on the side with the capsular contracture).

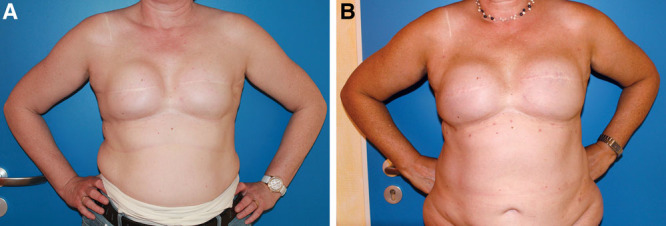

Fig. 1.

Reaching and sustaining analgesia. Preoperative pictures (A and B) of a 37-year-old patient (patient 1 of Table 1) with a history of breast cancer on the right side, after nipple-sparing mastectomies and implant-based reconstruction on both sides. Implant position is subpectoral/dual plane on both sides. The postoperative pictures (C and D) were taken 12 months after the last of 5 sessions of fat grafting. The ultrasound examination of the soft-tissue envelope before the procedures revealed a thickness of at least 0.2 cm and after them of at least 1.2 cm. The patient reported a softening of the capsule after the lipoinjections on both sides. Animation deformity improved also considerably.

Fat grafting led in all cases to better breast sensation, this being defined as a reduction of the foreign body sensation, the feeling of tension in the breast often radiating to the axilla and the feeling of a cold breast. In most cases, the period between lipofilling sessions lasted 3–4 months, which can be regarded as the mean follow-up time. In other (Table 3), the follow-up periods were definitively longer, up to 1 1/2 years. In these time spaces, regular examinations took place, demonstrating that the reduction of pain sensation was remarkably steady. The data show that the effect of fat grafting sets in mere weeks after the intervention, with all patients reporting an improvement as soon as 6 weeks.

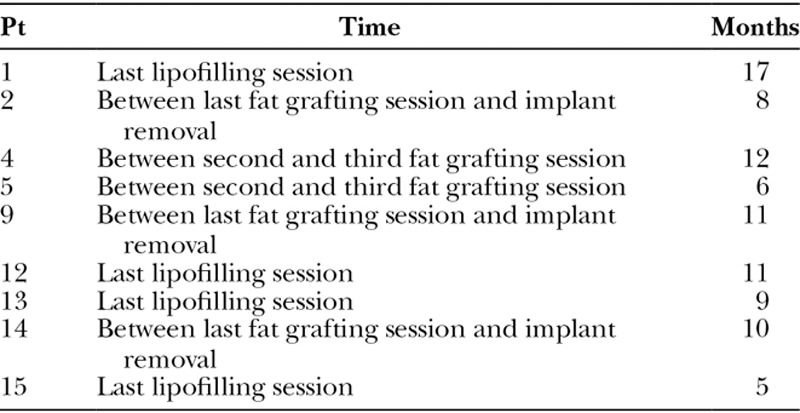

Table 3.

Follow-up Periods

Two patients developed an infection, one during the fat grafting sessions and one after the implant removal.

DISCUSSION

Roça et al.6 evaluated the efficacy of autologous fat grafting in a porcine model as a treatment for capsular contracture reporting a lack of difference in Baker classification after lipoinjection, although the capsules of treated animals were softer than those of untreated animals.

Our results go a step further and demonstrate that fat grafting can be used for pain relief due to capsular formation, regardless of the implant position to the pectoral muscle. Lipofilling has even the ability to reverse the capsular contracture grade from 4 to at least 3 and especially in subglandular positioned implants. In the cases of subpectoral/dual plane positions, the outcome seems to depend on the ability to position the fat graft directly in the interface between muscle and capsule, which is a more difficult task, mainly due to fears of damaging the implant, but can also be excellent. Patient 10 with prepectoral implant reconstruction on the right and dual plane on the left side highlights the different effects in both situations (Fig. 2). In the cases where latissimus dorsi muscle was used for implant coverage, putting the fat graft in the right plane was easier and led to excellent pain reduction. The possible reasons that 3 patients (patients 4, 10 left side, and 14) did not achieve freedom from pain could be, besides unsuitable placement of fat (currently we place the fat under direct visualization of the plane using ultrasound), that with lipoinjections only the ventral part of the capsule, the one pointing to the breast, is treated, and this does not influence pain that is generated by the dorsal capsule on the thoracic wall. But as pain rating scales between patients are not directly comparable (there is no direct comparison of the low starting pain levels of some patients with the higher ones of other patients),7 the emphasis should be given on the pain reduction achieved. Even in those patients who started with “high” pain levels (patients 4, 10 left side, and 14) and did not reach pain freedom, the pain reduction is significant (pain reduction in 2 of them was 50%, only patient 14 experienced reduction of 25%). Additionally, follow-up intervals of more than a year indicate that fat grafting can produce stable results over a long period of time.

Fig. 2.

Effects depending on implant position. A and B, Preoperative and postoperative views (after the lipofilling sessions) of a 54-year-old patient with a history of breast cancer on the left side, skin-sparing mastectomies and implant-based reconstruction on both sides with bilateral capsular contracture (patient 10 of Table 1). On the right side, implant position is prepectoral, on the left subpectoral/dual plane. Although the patient reported a softer capsule on the right side, the capsule was only partially softer on the other.

Our cases demonstrate that, with the adequate management of pain at the presence of an acceptable cosmetic result, the need for implant replacement is delayed, or even eliminated. This can be of great benefit in aesthetic surgery, but predominantly in reconstructive surgery, given that the most frequent type of breast reconstruction worldwide is implant based. Due to its regenerative properties, the concept of fat grafting could be applied to ameliorate fibrotic damage, especially after implant-based reconstruction and successive radiation therapy, a setting that degrades the cosmetic outcome and substantially increases the risk of capsular contraction. The number of sessions needed to achieve analgesia varies from patient to patient because the pain attributed to capsular fibrosis is experienced very differently among them and correlates often, but not always, with the capsule stiffness. Some patients needed one session to achieve good pain control, whereas others 5 sessions, showing an adding effect of the lipofilling over time. In this regard, patient 12 would have reached analgesia, had she not declined a third session. Our findings are in line with results reported from other groups, showing that fat grafting can be used successfully to treat pain, for example, pain after breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy (postmastectomy pain syndrome).8,9

CONCLUSIONS

Our observations lend support to the potential benefit of fat grafting as a novel strategy for the treatment of pain due to capsular contracture. Lipofilling could be a valuable tool in treating capsular contracture, in alleviating pain, and in improving skin quality and sensation of the breast.

Footnotes

Published online 13 November 2018.

Disclosure: Dr. Papadopoulos has received a lecture honorarium from Human med AG, Schwerin, Germany. Dr. Vidovic, Dr. Neid, and Dr. Abdallah have no financial information to disclose. No funding was received for this article. The Article Processing Charge was paid by the authors.

Liposuction device: Bodyjet, Human med AG, Schwerin, Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wan D, Rohrich RJ. Revisiting the management of capsular contracture in breast augmentation: a systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araco A, Caruso R, Araco F, et al. Capsular contractures: a systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frenkiel BA, Temple-Smith P, de Kretser D, et al. Follistatin and the breast implant capsule. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:e1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferreira-Valente MA, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Jensen MP. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain. 2011;152:2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Münch DP. [Breast augmentation with autologous fat - experience of 96 procedures with the BEAULI-technique]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2013;45:80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roça GB, Graf R, da Silva Freitas R, et al. Autologous fat grafting for treatment of breast implant capsular contracture: a study in pigs. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34:769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marco CA, Plewa MC, Buderer N, et al. Self-reported pain scores in the emergency department: lack of association with vital signs. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maione L, Vinci V, Caviggioli F, et al. Autologous fat graft in postmastectomy pain syndrome following breast conservative surgery and radiotherapy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38:528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caviggioli F, Maione L, Forcellini D, et al. Autologous fat graft in postmastectomy pain syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]