Abstract

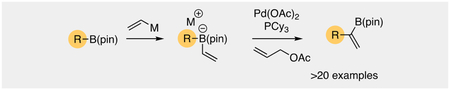

Organoboron ‘ate’ complexes undergo a net vinyl insertion reaction to give 1,1-disubstituted alkenyl boronic esters when treated with stoichiometric allyl acetate and a palladium catalyst. Reactions that employ vinyllithium afforded good to excellent yields after one hour, while reactions that employ vinylmagnesium chloride furnished modest to good yields after 18 hours.

Keywords: Boron, Allyl Complex, Palladium, Catalysis

Graphical Abstract

α-Methylene Organoboronic Esters: These compounds are prepared in a catalytic fashion for precursor boronic esters by a Pd-catalyzed rearrangement of the derived ‘ate’ complexes.

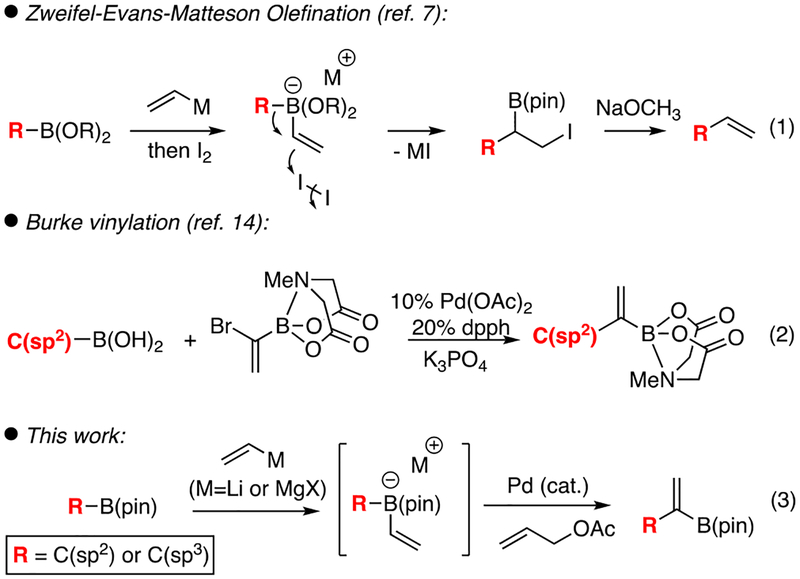

Organoboronic esters are valuable reagents in contemporary synthetic chemistry owing to the variety of stereospecific transformations they undergo.1 These processes include oxidation,2 amination,3 cross-coupling,4 homologation,5 and alkynylation, among others.6 Because of this utility, the development of new methods for constructing organoboronic esters from new classes of starting materials holds significant value. A particularly powerful transformation that applies to organoboronic esters is the halogen-promoted Zweifel-Evans-Matteson7 reaction that results in olefination of organoboron reagents (Scheme 1, eq. 1). This process occurs by conversion of an organoboronic ester to the derived ‘ate’ complex, followed by halogen induced 1,2-metallate shift and, finally, elimination to establish the alkene. While this process has been applied broadly to accomplish vinylation reactions, recent advances from Aggarwal employing selenium activation allow for stereoselective cis or trans alkenylation as well.8 In this manuscript, we present a reaction design that allows Pd(allyl) electrophiles to activate alkenylboron ‘ate’ complexes for the metallate shift reaction. While this activation mechanism has been employed in the context of conjunctive cross-coupling reactions, here we demonstrate the catalytic intermediate can be diverted towards β-hydride eliminination9 that establishes an alkene while leaving the original boronic ester group intact (eq. 3). This process thereby affords strategically-useful 1,1-disubstituted alkenylboronic esters by a catalytic vinylidenation of organoboronic ester precursors (Scheme 1). While a number of methods allow construction of similarly-substituted boron reagents,10,11,12,13 the only direct conversion of an organoboron starting material to the vinylidenation product involves cross-coupling to (α-bromovinyl)-MIDA boronate (eq. 2) and this process is limited to C(sp2) boronic acids as starting materials.14

Scheme 1.

Vinylidenation of Boronic Esters

Recently, we developed Pd-catalyzed conjunctive cross-coupling reactions between an organoboronic ester, a vinyllithium reagent, and a C(sp2) triflate to give chiral organoboronic esters with high levels of enantiopurity.15 This reaction has been expanded to include the use of Grignard reagents and C(sp2) halide electrophiles,16 alkenyl migrating groups,17 and has extended to nickel catalysts with both aryl18 and alkyl electrophiles.19 Perhaps unsurprisingly, direct extension to allyl electrophiles has proved a challenge, likely because η3 coordination of the allyl group occupies a coordination site necessary for binding and activation of the ‘ate’ complex. Indeed, recent reports by Ready20 suggest that enantioselective Pd-catalyzed reaction of indole-derived ‘ate’ complexes with allyl electrophiles, and similar racemic processes established by Ishikura21 and Murakami22, appear to occur by outer-sphere anti addition of electron-rich alkynyl- and indole-derived ‘ate’ complexes to the back side of the Pd(allyl). In this report, we show that catalyst features that allow Pd(allyl) complexes to bind an ‘ate’ complex and promote the metallate shift also allow β-hydrogen elimination of the intermediate and thus equation 3 to operate.

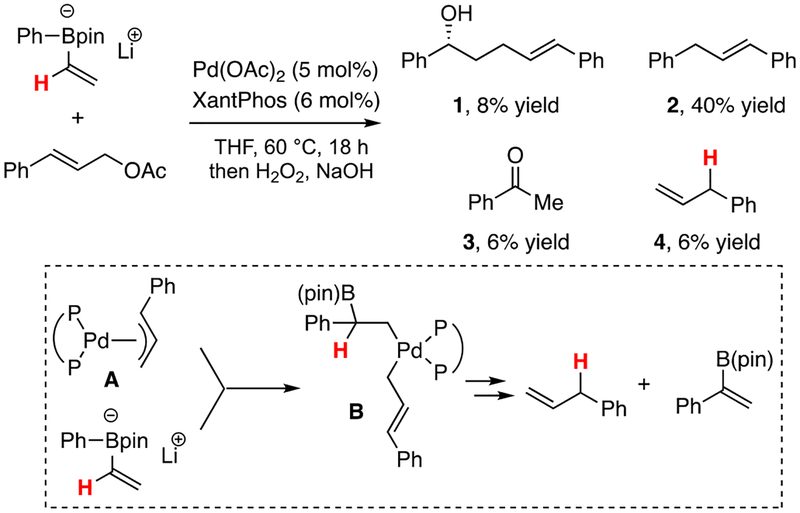

Initial efforts to promote metallate shift reactions with Pd(allyl) complexes showed that reactions with allyl electrophiles could deliver products of 1,2-rearrangement, but they were formed in low yield. As exemplified by the experiment in Scheme 2, when cinnamyl acetate was treated with (phenyl)vinylB(pin) ‘ate’ complex in the presence of Pd(OAc)2 and wide-bite-angle bidentate diphosphine ligands, the conjunctive coupling product 1 was formed in very low yield and, in addition, small amounts of Suzuki-Miyaura coupling products (2) were formed, as well as acetophenone and allyl benzene. That the latter two compounds were formed in equal amounts signaled that a palladium-induced 1,2-metallate shift-β-hydrogen elimination process can operate (inset Scheme 2) and deliver the alkenylboronic ester, which is converted to 3 upon oxidative work-up.

Scheme 2.

Initial Observations of Boronic Ester Vinylidenation

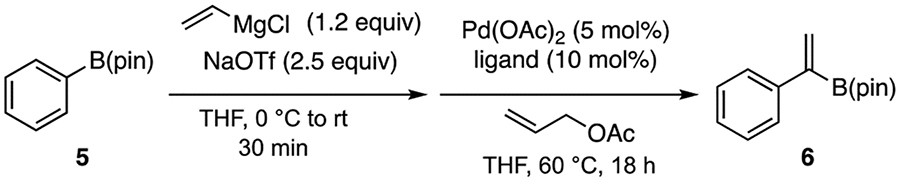

With an initial experiment suggesting that catalytic cycles involving β-hydrogen elimination might provide a route to unique vinylidenation products, we considered alternate catalyst choices that might facilitate the metallate shift–β-elimination sequence. Of note, the coordinative saturation of bis(phosphine)-ligated palladium(allyl) complex A (Scheme 2) would render this species less able to bind and activate the ‘ate’ complex. To remedy this situation and to provide an open coordination site for β-hydrogen elimination from B, we considered replacing the bis(phosphine) ligand with monodentate structures. After a ligand survey using phenylB(pin), vinylmagnesium chloride, sodium triflate, and allyl acetate23 (Table 1), it was found that monodentate phosphine ligands can provide higher yields compared to bidentate ligands, with PCy3 being an optimal ligand (entry 9). Additionally, it was found that increasing the amount of vinylmagnesium chloride and NaOTf leads to improved yields, and that the catalyst loadings could be reduced to 2.5 mol % with reaction times as short as one hour.

Table 1.

Ligand Survey for Vinylidenation of PhenylB(pin)a

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ligand | Recovered 5 (%)b | Yield 6 (%)b |

| 1 | XantPhos | 37 | 5 |

| 2 | dppe | 72 | <2 |

| 3 | PPh3 | 39 | 49 |

| 4 | P(o-tolyl)3 | 46 | 35 |

| 5 | PPh2Me | 61 | 24 |

| 6 | PPh2Cy | 36 | 54 |

| 7 | PPhCy2 | 18 | 61 |

| 8 | CyJohnPhos | 28 | 59 |

| 9 | PCy3 | 28 | 65 (58) |

Reactions conducted at initial [5] = 0.1 M.

Yields determined by 1H NMR using 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane as an internal standard. Yields in parentheses represent isolated yields.

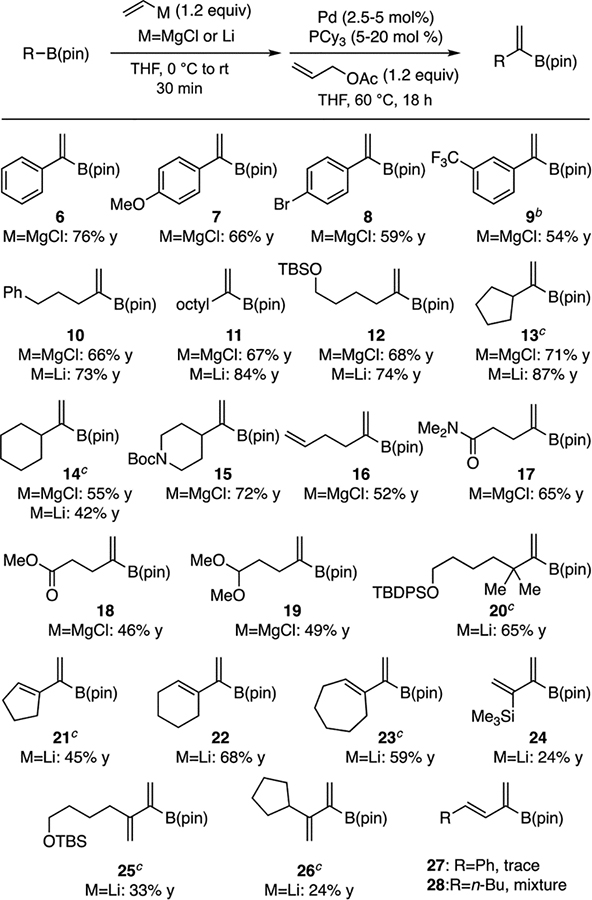

With optimized conditions, we embarked on a study of the generality of this reaction. As shown in Table 2, arylboronic esters (entries 6–9) underwent the reaction in useful efficiency, and showed that the reaction tolerates both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups. Alkylboronic esters also proved to be competent substrates but benefitted from modified reaction conditions. In a previous study,9 the addition of DMSO as a co-solvent was found to stabilize the ‘ate’ complex formed from alkylboronic esters and Grignard reagents and this modification proved helpful to the reaction of these substrates here as well. However, the addition of DMSO retarded the reaction rate and 18 hours were required for these reactions to reach completion. Furthermore, changing the palladium source from Pd(OAc)2 to Pd2(dba)3 gave slightly increased yields, but required catalyst loadings of 5% (see Supporting Information for details.). With these modifications, 3-phenylpropyl (10) and n-octyl (11) migrating groups were tolerated, as was a silyl ether (12). The reaction was also effective with cyclic substrates, including cyclopentyl (13), cyclohexyl (14), and N-Boc-protected pipiridine (15) migrating groups. Migrating groups bearing potentially sensitive functional groups such as a monosubstituted olefin (16), amide (17), ester (18), or acetal (19) were also well-tolerated in this reaction. While examples in Table 2 suggest that the reaction is effective with Grignard-derived ‘ate’ complexes, it should be noted that alkyllithium derived ‘ate’ complexes often offer superior reactivity such that catalyst loading can be reduced to 1 mol% Pd, with many substrates still achieving complete conversion in one hour (10–12). Cyclic substrates (13 and 14), as well as tertiary substrate (20), required catalyst loadings of 5 mol% for productive reaction. Of note, it was also found that cycloalkenyl substrates (21–23), which proved unsuitable with vinylmagnesium chloride, were transformed to their corresponding 1,1-disubstituted boronic esters with Li-based reagents. Acyclic alkenylboronic esters, however, were not as effective in this reaction giving modest yields (24-26). Lastly, β-disubstituted vinylboronic esters (27-28) were ineffective substrates.

Table 2.

Vinylation of Organoboronic Esters[a]

|

Reactions conducted at [substrate] = 0.1 M. Yields are isolated yields and are an average of two experiments. Where necessary, yields are corrected to account for inseparable co-eluting unreacted starting material. For arylboronic esters, 2.5% Pd(OAc)2/5% PCy3 was employed; for alkylboronic esters with vinylmagnesium chloride, 2.5% Pd2(dba)3 and 20% PCy3 were employed in 1:1 THF/DMSO solvent. For reactions employing vinyllithium, 1 mol% Pd(OAc)2 and 2 mol% PCy3 were employed. [b] Reaction time = 3 h. [c] Reaction employed 5 mol% Pd(OAc)2 and 10 mol% PCy3.

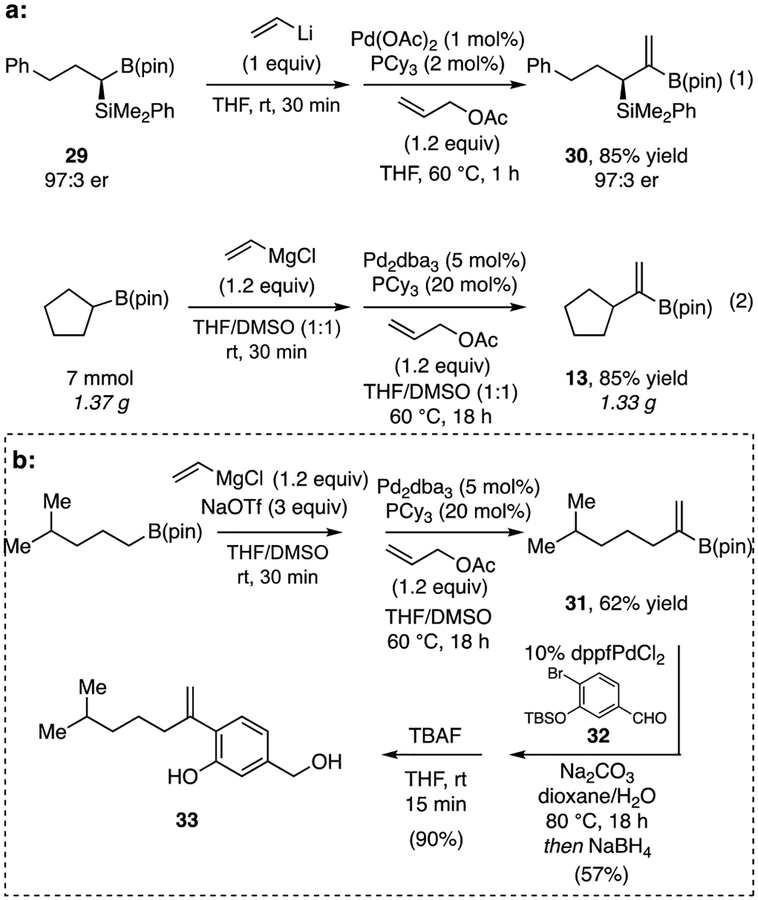

To examine features related to practical utility, the experiments in Scheme 3 were conducted. As the experiment in eq. 1 demonstrates, the vinylidenation occurs with complete sterospecificity: with enantiomerically-enriched boronic ester 29, prepared by Pt-catalyzed asymmetric hydrosilylation reaction,24 vinylidenation to 30 occurs in good yield and without erosion of enantiomeric purity. In addition, the experiment in equation 2 demonstrates that the vinylidenation could be conducted on preparative scale (> one gram) and occurs with similar efficiency as smaller scale reactions. Lastly, we examined cross-coupling of homologation products as a route to the natural product 7-deoxy-7,14-didehydrosydonol25 (33, Scheme 3b). While experiments that directly employ the unpurified vinylidenation product 31 in cross-coupling with bromide 32 could deliver product, yields were low and not reproducible. However, 31 is stable to silica gel chromatography and, after purification, participated in efficient Suzuki-Miyaura reaction. After reduction of the aldehyde and TBAF deprotection natural product 33 was obtained in reasonable yield.

Scheme 3.

Practical Features of Boronic Ester Vinylidene Homolgation

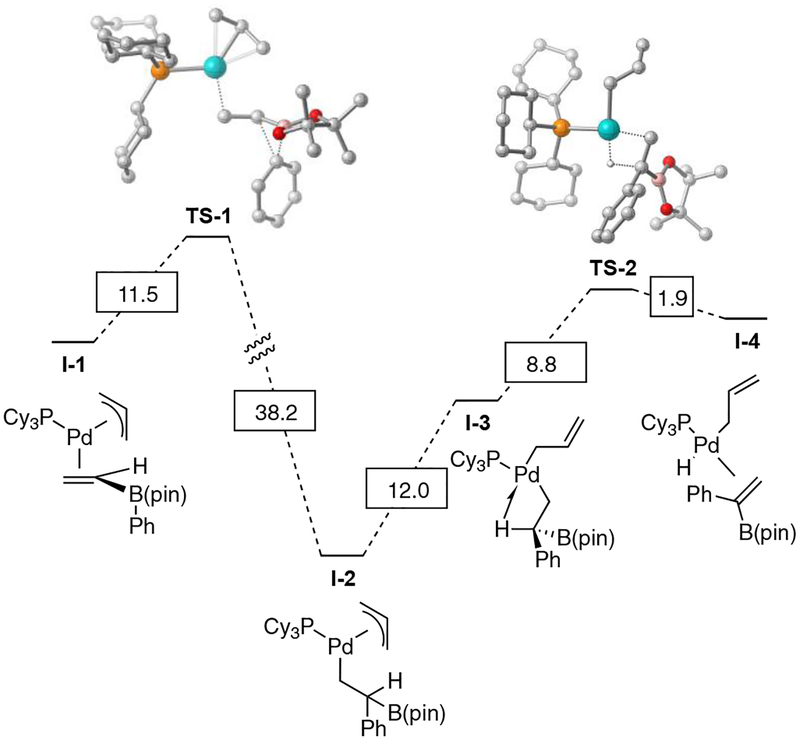

Conjunctive cross-coupling reactions involving diphosphine palladium complexes appear to occur by a low-barrier metal-induced metallate shift followed by reductive elimination.26 Because the vinylidene insertion operates with an alternate Pd complex than previously described couplings, it was of interest to learn about this new reaction pathway. Analysis of the reaction was conducted by DFT (see Scheme 4 for description of method) and employed a complex between (η3-allyl)Pd(PCy3) and the ‘ate’ complex as a starting point (I-1, the pathway involving a bis(phosphine)Pd(η1-allyl) is much higher in energy). As depicted in Scheme 4, metallate shift promoted by (PCy3)Pd(η3-allyl) occurs via TS-1 with an activation barrier of 11.5 kcal/mol and furnishes complex I-2 as the product. It is notable that this barrier is higher than that involved in conjunctive cross-coupling reactions (ca. 5 kcal/mol); however, it is not so high that it provides an impediment to successful reaction. An important feature of the allyl ligand in complex I-2 is that it can adopt the η1-bonding mode thereby providing an open coordination site for an agostic interaction27 with the substrate β-hydrogen (to give I-3). This change in bonding mode is 12 kcal/mol uphill and is followed by an 8.8 kcal/mol β-hydrogen elimination via TS-2. While the β-hydrogen elimination is an endothermic process, it is followed by exothermic displacement of the alkenylboron as the allyl group reassumes the η3 bonding mode (see Supporting Information for details).

Scheme 4.

Calculated reaction coordinate for metal-induced metallate shift/β-hydrogen elimination involved in the vinylidenation reaction. Optimized geometries calculated using DFT (BP86/Def2-SVP; PCM solvent model with THF). ΔG Values are in kcal/mol, calculated using DFT (PBE0-D3BJ/def2-TZVPP//BP86/def2-SVP; SMD solvent model with THF). Hydrogen atoms removed from structures for clarity.

In summary, we have described a catalytic vinylidenation of organoboronic esters that provides a new synthesis route to alkenylboronic esters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH (GM-R35–127140).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- (1).Hall DG, Ed. Boronic Acids: Preparation, Applications in Organic Synthesis and Medicine, 2nd ed; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Brown HC, Synder C, Subba Rao BC, Zweifel G Tetrahedron 1986, 42, 5505. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Mlynarski SN, Karns AS, Morken JP J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 16449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Miyaura N, Suzuki A Chem. Rev 1995, 95, 2457. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lennox AJ, Lloyd-Jones GC Chem. Soc. Rev 2014, 43, 412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cherney AH, Kadunce NT, Reisman SE Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 9587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rygus JPG, Crudden CM J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 18124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Matteson DS, Sadhu KM J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 2077. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Wang Y, Noble A, Myers EL, Aggarwal VK Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 4270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Zweifel G, Polston NL, Whitney CC J. Am. Chem. Soc 1963, 90, 6243.Matteson DS Synthesis 1975, 147.Matteson DS, Jesthi PK J. Organomet. Chem 1976, 110, 25.Evans DA, Thomas RC, Walker JA Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 17, 1427.Evans DA, Crawford TC, Thomas RC, Walker JA J. Org. Chem 1976, 41, 3947.For a recent advance in this area, see:Armstrong RJ, Niwetmarin W, Aggarwal VK Org. Lett 2017, 19, 2762.

- (8).Armstrong RJ, García-Ruiz C, Myers EL, Aggarwal VK Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).For a recent relevant β-hydrogen elimination with Pd(allyl) complexes, see:Murray SA, Luc ECM, Meek SJ Org. Lett 2018, 20, 469.Shvo Y, Arisha YAHI J. Org. Chem 1998, 63, 5640.Chen Y, Romaire JP, Newhouse TR J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 5875.Chen Y, Turlik A, Newhouse TR J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 1166.Chen Y, Huang D, Zhao Y, Newhouse TR Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 8258.Huang D, Zhao Y, Newhouse TR Org. Lett 2018, 20, 684.

- (10).(a) Gao F, Hoveyda AH J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 10961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jang H, Zhugralin AR, Lee Y, Hoveyda AH J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 7859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Moure AL, Arrayás RG, Cárdenas DJ, Alonso I, Carretero JC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 7219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Moure AL, Mauleón P, Arrayás RG, Carretero JC Org. Lett 2013, 15, 2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) García-Rubia AG, Romero-Revilla JA, Mauleón P, Arrayás RG, Carretero JC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 6857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Ojha DP, Prabhu KR Org. Lett 2016, 18, 432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Yoshida H ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 1799. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Takagi J, Takahashi K, Ishiyama T, Miyaura N J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 8001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Guan W, Michael AK, McIntosh ML, Koren-Selfridge L, Scott JP, Clark TB J. Org. Chem 2014, 79, 7199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Coombs JR, Zhang L, Morken JP Org. Lett 2015, 17, 1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Woerly EM, Miller JE, Burke MD Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 7732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Zhang L, Lovinger GJ, Edelstein EK, Szymaniak AA, Chierchia MP, Morken JP Science 2016, 351, 6268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lovinger GJ, Aparece MD, Morken JP J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Edelstein EK, Namirembe S, Morken JP J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 5027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Chierchia MP, Law C, Morken JP Angew. Chem. Int. End 2017, 56, 11870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lovinger GJ, Morken JP J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 17293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).(a) Panda S, Ready JM J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Panda S, Ready JM J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 13242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Ishikura M, Agata I Heterocycles 1996, 43, 1591. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ishikura M, Kato H Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 9827. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Ishida N, Shinmoto T, Sawano S, Miura T, Murakami M Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 2010, 83, 1380. [Google Scholar]

- (23).For seminal reports on β-hydride elimination reactions promoted by allyl reagents as the oxidant, see:Shimizu I, Tsuji J J. Am. Chem. Soc 1982, 104, 5844.Shimizu I, Minami I, Tsuji J Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 1797.Minami I, Takahashi K, Shimizu I, Kimura T, Tsuji J Tetrahedron 1986, 42, 2971.Shvo Y, Arisha Y.sA. H. I. J. Org. Chem 1998, 63, 5640.

- (24).Szymaniak AA, Zhang C, Coombs JR, Morken JP ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Chung Y-M, Wei CK, Chuang D-W, El-Shazly M, Hsieh C-T, Asai T, Oshima Y, Hsieh T-J, Hwang T-L, Wu Y-C, Chang F-R Bioorg. & Med. Chem 2013, 21, 3866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Myhill JA, Zhang L, Lovinger GJ, Morken JP Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 12799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).For a recent review of agostic interactions, see:Brookhart M, Green MLH, Parkin G Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci 2007, 104, 6908.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.