Abstract

The nutritional quality of foods/drinks available at urban food pantries is not well established. In a study of 50 pantries listed as operating in the Bronx, NY, data on food/drink type (fresh, shelf-stable, refrigerated/frozen) came from direct observation. Data on food/drink sourcing (food bank or other) and distribution (prefilled bag versus client choice for a given client’s position in line) came from semi-structured interviews with pantry workers. Overall nutritional quality was determined using NuVal® scores (range 1–100; higher score indicates higher nutritional quality). Twenty-nine pantries offered zero nutrition at listed times (actually being closed or having no food/drinks in stock). Of the 21 pantries that were open as listed and had foods/drinks to offer, 12 distributed items in prefilled bags (traditional pantries), 9 allowed for client choice. Mean NuVal® scores were higher for foods/drinks available from client-choice pantries than traditional pantries (69.3 vs. 57.4), driven mostly by sourcing fresh items (at 28.3% of client-choice pantries vs. 4.8% of traditional pantries). For a hypothetical ‘balanced basket’ of one of each fruit, vegetable, grain, dairy and protein item, highest-NuVal® items had a mean score of 98.8 across client-choice pantries versus 96.6 across traditional pantries; lowest-NuVal® items had mean scores of 16.4 and 35.4 respectively. Pantry workers reported lower-scoring items (e.g., white rice) were more popular--appeared in early bags or were selected first--leaving higher-scoring items (e.g., brown rice) for clients later in line. Fewer than 50% of sampled pantries were open and had food/drink to offer at listed times. Nutritional quality varied by item type and sourcing and could also vary by distribution method and client position in line. Findings suggest opportunities for pantry operation, client and staff education, and additional research.

Keywords: Food insecurity, urban, food pantry, food bank, food assistance, nutrition

INTRODUCTION

Food insecurity is widespread in the U.S., affecting up to 15.8 million U.S. households (12.7 percent).1 The term ‘food insecurity’ means lacking consistent access to adequate food as a result of monetary or other resource constraints.1 Experiencing food insecurity has been linked to social and academic problems,2,3 mental health issues,3–5 and diet-related chronic diseases.6–9 Food insecurity has also been linked to poorer overall health.10–12

For many who are food insecure, an important resource for obtaining food can be food pantries.13–15 Food pantries are emergency food programs that distribute free foods and drinks to those struggling to achieve nutritional adequacy.16 However, whether adequate nutrition can come from food pantries is not well-established.

Studies examining nutrition from food pantries have mostly considered only select nutrients. Such studies have, for example, demonstrated lacking levels of vitamins A and C,17–20 zinc,17,20 and calcium17–19 in pantry foods and drinks. Other research has documented deficits in the availability of dairy products, fruits, and vegetables from food pantries.17,20–22 Beyond considerations of food constituents and food groups though, studies have generally not considered broader nutritional quality, e.g. as with an overall nutritional index. Studies have also generally not considered potential differences in nutrition by item type (e.g., fresh, frozen, shelf stable) or by item sourcing.

Two studies from Minnesota did use an overall nutritional index, the Healthy Eating Index, to suggest that the items procured specifically from two food banks (non-profits supplying food pantries with shelf-stable items16) were of only ‘mid-range’ nutritional quality.23,24 However the nutritional quality of other types of food, procured from other suppliers, has not specifically been reported. Also not reported is whether nutritional quality relates to the methods pantries use to distribute food to clients; other authors have speculated that whether allowing clients to choose items for themselves or giving them handouts in a prefilled bag could be important.25

In the current study, investigators sought to examine the overall nutritional quality of pantry foods and drinks. Specifically assessed were associations with item type, item sourcing, and distribution method.

METHODS

This study began with early exploratory visits to a sample of food pantries. Exploratory visits informed later data collection about pantries and their offerings (e.g., regarding food/drink sourcing and pantry distribution methods) as described in another publication.26 The study did not include human subjects and was considered exempt by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Setting

The study took place in the Bronx, NY. The Bronx is both one of the five boroughs of New York City (NYC) and a county of New York State. The Bronx has the worst health outcomes of all 62 counties in New York State (e.g., higher rates of obesity, poor or fair health, and premature death),27 and the southern half of the borough is home to the country’s poorest congressional district (where more than 50% of census tracts have poverty rates exceeding 30% of individuals).28

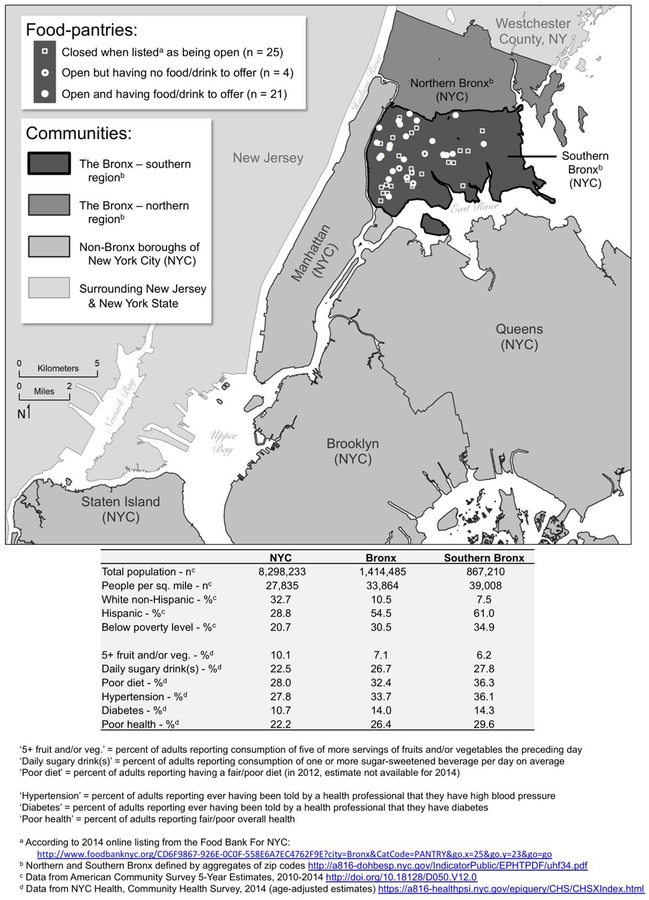

Food insecurity is higher in the Bronx than in any other borough of NYC, with 31% of residents overall and 37% of children living in food-insecure homes.29 In the context of food insecurity, residents of the southern Bronx report less-healthful dietary intake (i.e., lower consumption of fruits and vegetables, higher consumption sugar-sweetened beverages), higher rates of diet-related chronic diseases, and poorer overall health than the rest of the Bronx or rest of NYC30 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The southern Bronx, and its food pantries, in the context of New York City and surrounding areas

Sample

Investigators identified food pantries in the southern Bronx using an online listing from the city’s largest hunger-relief organization, the Food Bank For NYC.31 The listing included 88 pantry sites. Investigators aimed to include all of these sites in the study.

Ultimately, the study only included 50 sites (Figure 1 and Appendix - Figure 1). Other sites were not included for three related reasons: (1) pantries had limited hours of operation; generally being open fewer than 2 hours per week26 and having operating hours that often overlapped with those of other pantries in different, non-neighboring locations; (2) pantries were not reliably open as listed; the time spent making second or third visits to some pantries was time not making initial visits to others, (3) the availability of data collectors--and funding for data collection--was limited to an eight-week period; 50 pantry sites was the total number of pantries investigators were able to reach over eight weeks.

Data Collection

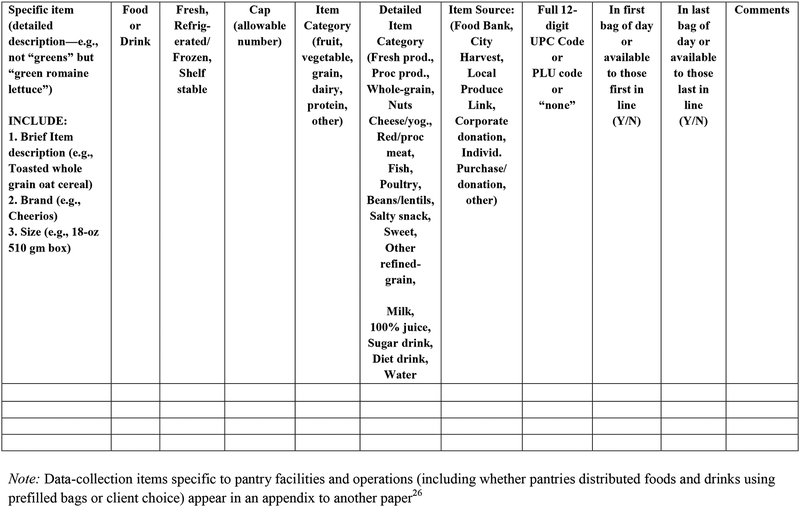

As a starting point for data collection, investigators drafted a rough data-collection tool based on tools from prior food-environment research.32–37 The tool was then refined based on early exploratory visits to a sample of three food pantries. At these visits, investigators made observations about pantry operations and had unstructured interviews with pantry workers. From these activities, investigators learned about several aspects of food-pantry operations that distinguished pantries from other previously studied local food sources: e.g., the possibility of pantries not being open as listed; the potential suppliers of pantry foods and drinks; the types of food and drink items that might be available at pantries; the methods pantries generally use to distribute items to clients; and that the popularity of specific items along with clients’ positions in line might influence what items clients receive. All of these considerations were included in the final data-collection tool (Appendix - Figure 2 for items specific to food and drink offerings; Appendix of another publication for items specific to pantry facilities and operations26).

Guided by the data-collection tool, two investigators conducted assessments at food pantries June-August 2014. Assessments of all available food and drink items (everything in stock) occurred whenever visited pantries were open and had items to offer. Investigators used paper audit forms while onsite, and then entered structured data elements into REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), version 5.6.3 (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN).38 Structured data included detailed descriptions of fresh items, and detailed package information--including brand, size, and barcode UPC (universal product code)--for other items, in order to allow later determination of nutritional quality. Items that might be available to clients first in line versus clients last in line were determined based on reports of pantry staff (Appendix - Figure 2).

Nutritional Quality Determination

To determine nutritional quality of food and drink items, investigators used the Overall Nutritional Quality Index (ONQI). The ONQI summarizes overall nutrition for a food or drink item into a single score, NuVal®, by considering favorable and unfavorable nutrients and ingredients on a per unit basis. The score can range from 1 to 100, with higher value indicating higher nutritional quality. Details about the development, components, and performance of the ONQI algorithm and NuVal® scoring have been published elsewhere.39,40 A large longitudinal study demonstrated that consuming products with higher NuVal® scores is associated with lower body mass index, lower risk of chronic disease, and lower total mortality.41

NuVal® scores are higher for whole foods (e.g., apples = 100) and have an inverse relationship with food processing, which may, for example, increase the concentration of sugars, the glycemic index, and/or the energy density (e.g., apple juice = 10).39,40 Ultra processed products--particularly those low in vitamins, minerals, and fiber and/or high in added sugars, sodium, and/or trans fat--score particularly poorly (e.g., cinnamon buns = 2, soda = 1). Based on nutrient composition, NuVal® scores for similar products can differ substantially (e.g., yellow cling peaches in light syrup = 37, yellow cling peaches in pear juice = 73). Scores can also differ somewhat for different brands of the same product (e.g., canned chunk lite tuna in water can vary from 51–58 depending on brand, due to differences in ingredients like salt). Investigators obtained exact NuVal® scores for all the items pantries offered based on precise descriptions for fresh products (e.g., “French haricots verts green beans”) and UPC or exact package details for other products.

Data Analysis

From early exploratory visits, it became clear that there were essentially two distinct methods for distributing foods and drinks at pantries: (1) prefilled bags, where pantry workers pack a set assortment of items to hand out to clients (with generally consistent offerings bag-to-bag and client-to-client as long as provisions last); and (2) client choice, a system more like grocery shopping, where clients choose a certain number of specific items from a set selection, often in item categories. Analyses separately considered pantries operating by a prefilled-bag model (traditional pantries) and those operating by client choice.

Analyses included frequency distributions, proportions, means, minima, and maxima, calculated using Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Classifications for individual items included the following characteristics: food vs. drink; item form (fresh, refrigerated/frozen, or shelf-stable); food-group category (fruit, vegetable, grain, dairy, protein--based on MyPlate.gov categorizations42--or ‘other’); item source (food bank versus others); and detailed item category (more-specific food and drink classifications).

Investigators calculated the absolute number of items offered at each pantry, the relative proportion of specific items, and corresponding NuVal® scores both by individual pantry and across all assessed pantries. Analyses considered items available overall, and then separately by prefilled-bag or client-choice models. Analyses also considered whether items were likely to be available to clients first in line or last in line (based on reports of pantry staff who packed bags or arranged items for client choice). Finally, analyses considered hypothetical best- and worst-case scenarios for nutritional quality of pantry provisions using hypothetical collections--or ‘balanced baskets’ (one of each of fruit, vegetable, grain, dairy, and protein)--with the highest and lowest NuVal® scores.

RESULTS

Of the 50 food pantries included in the study, 25 were not open (on at least two occasions when attempts to visit were made) and, thus, did not have any food or drink to assess. The reasons for pantries not being open--including temporary and permanent closures, with and without notification--are detailed elsewhere.26 Of the 25 open pantries, four were completely out of food and drink; they had not received deliveries and thus had no items to offer clients to consume or investigators to assess. For the 21 pantries that did have foods and drinks to distribute (example images shown in Appendix - Figure 2), 12 operated by a traditional prefilled-bag model of distribution and nine operated by client choice.

Table 1 details the type, sources, and nutrition quality of specific foods and drinks available from the 12 traditional pantries that used prefilled bags. These pantries offered about a dozen items (11.8 on average) that had a mean NuVal® score of 57.4. Food items predominated over drink items and were mostly shelf-stable (94.3% on average), with a mostly even distribution across food-group categories (except for dairy, which was less common). Most foods (74.1% on average) came from the Food Bank For NYC (a non-profit with government contracts to distribute shelf-stable food). Processed produce--e.g., sauces, soups, canned fruits and vegetables--predominated (37.1% of all pantry items on average). Footnotes to Table 1 gives specific examples of the food and drink items that were available. Pantries using traditional prefilled-bags offered several items not carried by client-choice pantries: lower-NuVal® items like Vienna sausages, ham, BBQ sauce, sugary granola bars, and fruit punch.

Table 1.

Type, sources, and nutrition quality of foods and drinks from Bronx food pantries using traditional prefilled bags (n = 12 pantries)

| Number of items | Percentage of offerings | NuVal® scores by pantry | NuVal® across all pantries | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item characteristic | Mean n across pantries | Min n at any pantry | Max n at any pantry | Mean % across pantries | Min % at any pantry | Max % at any pantry | Mean of all pantries’ mean scores | Mean of all pantries’ min score | Mean of all pantries’ max score | Median score | Min score | Max score |

| Total items | 11.8 | 2 | 26 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 57.4 | 7.0 | 93.0 | 70.5 | 1 | 100 |

| Food or drink | ||||||||||||

| Food items | 10.3 | 2 | 24 | 86.2 | 42.9 | 100.0 | 62.5 | 17.9 | 93.0 | 77 | 1 | 100 |

| Drink items | 1.5 | 0 | 4 | 13.8 | 0.0 | 57.1 | 41.9 | 17.4 | 70.0 | 10 | 2 | 89 |

| Item form | ||||||||||||

| Fresh | 0.7 | 0 | 4 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 21.1 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Refrigerated or frozen | 0.3 | 0 | 3 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 11.5 | 55.0 | 33.0 | 88.0 | 44 | 33 | 88 |

| Shelf stable | 10.8 | 2 | 23 | 94.3 | 78.9 | 100.0 | 55.3 | 7.0 | 91.7 | 65 | 1 | 100 |

| Food-group categorya | ||||||||||||

| Fruit | 2.8 | 0 | 9 | 23.3 | 0.0 | 47.4 | 52.1 | 28.5 | 75.4 | 49.5 | 4 | 100 |

| Vegetable | 2.5 | 1 | 5 | 23.3 | 11.1 | 50.0 | 79.5 | 65.4 | 89.3 | 99 | 10 | 100 |

| Grain | 2.3 | 0 | 8 | 17.4 | 0.0 | 30.8 | 66.2 | 49.5 | 80.8 | 84 | 9 | 94 |

| Dairy | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 89.0 | 89.0 | 89.0 | 89 | 89 | 89 |

| Protein | 2.7 | 1 | 10 | 23.2 | 6.3 | 50.0 | 52.4 | 36.5 | 68.3 | 51.5 | 20 | 100 |

| Other | 0.9 | 0 | 3 | 8.7 | 0.0 | 28.6 | 8.9 | 6.3 | 11.6 | 6.5 | 1 | 29 |

| Item source | ||||||||||||

| Food Bank | 8.3 | 0 | 26 | 74.1 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 58.5 | 6.2 | 91.6 | 84 | 1 | 100 |

| City Harvest | 0.2 | 0 | 1 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Corporations/ Businesses | 1.6 | 0 | 9 | 13.4 | 0.0 | 90.0 | 57.0 | 40.3 | 76.3 | 30 | 1 | 100 |

| Local Produce Link | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Detailed item categoryb | ||||||||||||

| Fresh produce | 0.7 | 0 | 4 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 21.1 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Processed produce | 4.1 | 1 | 7 | 37.1 | 23.1 | 70.0 | 64.9 | 33.6 | 88.3 | 83 | 4 | 100 |

| Whole-grain products | 0.8 | 0 | 3 | 5.8 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 93.1 | 93.0 | 93.3 | 93 | 93 | 94 |

| Nuts | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cheese/yogurt | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Red/processed meats | 0.5 | 0 | 2 | 6.9 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 26.9 | 26.0 | 27.8 | 27.5 | 20 | 33 |

| Fish | 0.8 | 0 | 4 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 15.4 | 68.8 | 60.8 | 75.2 | 77 | 51 | 91 |

| Poultry | 0.6 | 0 | 1 | 4.6 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 30.1 | 30.1 | 30.1 | 25 | 20 | 44 |

| Beans, lentils, legumes | 0.9 | 0 | 3 | 7.6 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 75.0 | 65.0 | 84.2 | 84 | 29 | 100 |

| Salty snacks | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sweet | 0.5 | 0 | 2 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 7 | 1 | 24 |

| Other refined-grain item | 1.6 | 0 | 5 | 11.6 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 58.5 | 44.7 | 74.2 | 65 | 9 | 84 |

| Milk | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 89.0 | 89.0 | 89.0 | 89 | 89 | 89 |

| 100% juice | 0.6 | 0 | 2 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 11.8 | 11.7 | 12.0 | 10 | 6 | 24 |

| Sugary drinks | 0.3 | 0 | 2 | 3.7 | 0.0 | 28.6 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 6.0 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

| Diet drinks | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Water/carbonated water | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Example items by food-group category (bold typeface = items not offered through pantries operating by ‘client choice’):

Fruit = fresh fruits, 100% juices, applesauce, dried fruits, and canned fruits in syrups

Vegetable = fresh vegetables, tomato-based pasta sauces, vegetable soups, and canned vegetables and corn

Grain = hot and cold cereals, rice, breads, and pasta/noodles including ‘Mac and Cheese’

Dairy = shelf-stable 1% milk

Protein = included canned meats and fish, canned soups and casseroles with meat, canned and dried beans and lentils and chickpeas, peanut butter, frozen tilapia

Other = sweetened cereals, sugar-added juice cocktails, fruit jellies, cranberry sauce, BBQ sauce, sugary granola bars, condensed soups including cheese soup

Example items by detailed item category (bold typeface = items not offered through pantries operating by ‘client choice’):

Fresh produce = whole fresh fruits and vegetables

Processed produce = tomato-based pasta sauces, vegetable soups, canned vegetables canned corn, canned sweet fruits in syrups, applesauce, dried fruits

Whole gain = brown rice, oatmeal, whole-wheat pasta

Red and processed meats = Vienna sausages, beef ravioli, pork, and ham

Fish = canned salmon, tuna, mackerel, and sardines, and frozen tilapia

Poultry = canned chicken, canned chicken soups

Beans, lentils, legumes = dried and canned beans, lentils, peanut butter

Sweets = sweetened cereals, fruit jellies, cranberry sauce, BBQ sauce, sugary granola bars

Other refined grains = hot and cold refined cereals, white rice, white breads, corn flakes, and refined pasta/noodles, including ‘Mac and Cheese’

Milk = shelf-stable 1% milk

Juice = 100% apple, grape, grapefruit, and 100% fruit punch

Sugary drinks = sweetened teas, juice cocktails and concentrates

NOTE: There were no nuts, cheese/yogurt, salty snacks (like potato chips and pretzels), diet drinks, or bottled water/carbonated water available.

Reported differences in pantry offerings for clients near the fronts of pantry lines (Appendix - Table 1) versus near the backs of pantry lines (Appendix - Table 2) were generally unremarkable at traditional pantries using prefilled bags. Exceptions were for the following two values: (1) the mean of all pantries’ mean NuVal® scores and (2) the median NuVal® score across all pantries. These values were both higher for items reportedly available towards the back of lines (60.7 and 83 respectively; Appendix - Table 2) than for items reportedly available towards the front of lines (58.5 and 77 respectively; Appendix - Table 1). Contributing to these differences, lower-scoring refined-grain items were reportedly more available at the fronts of lines, whereas higher-scoring whole-grain items were reportedly available at both the fronts and backs of lines. Correspondingly, the mean of all traditional pantries’ mean NuVal® scores for the food-group ‘grain’ was lower for items reportedly available near fronts of lines (65.3; Appendix - Table 1) than near the backs of lines (73.8; Appendix - Table 2). The suggestion is that refined-grain products were offered to clients preferentially up front, leaving whole-grain products for those arriving later.

Table 2 shows type, sources, and nutrition quality of offerings from the nine client-choice pantries. Compared to traditional pantries that distributed items using prefilled bags, the average number of available items at client-choice pantries was nearly three times higher (at 35.1), and the average NuVal® score was also higher (by >20%, at 69.3). These differences reflected a greater availability of fresh items at client-choice pantries, especially fresh vegetables. Differences also reflected alternative sourcing: playing bigger roles at client-choice pantries were City Harvest (a non-profit, rescuing foods from restaurants, grocers, and manufacturers) and Local Produce Link (a non-profit connecting pantries directly with local farms). Client-choice pantries offered items that could not be found at pantries using traditional prefilled bags: higher-NuVal® items like fresh herbs, whole wheat bread, cottage cheese, chickpeas, and whole chickens.

Table 2.

Type, sources, and nutrition quality of foods and drinks from Bronx food pantries using ‘client choice’ (n = 9 pantries)

| Number of items | Percentage of offerings | NuVal® scores by pantry | NuVal® across all pantries | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item characteristic | Mean n across pantries | Min n at any pantry | Max n at any pantry | Mean % across pantries | Min % at any pantry | Max % at any pantry | Mean of all pantries’ mean scores | Mean of all pantries’ min score | Mean of all pantries’ max score | Median score | Min score | Max score |

| Total items | 35.1 | 9 | 65 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 69.3 | 5.7 | 100.0 | 84 | 1 | 100 |

| Food or drink | ||||||||||||

| Food items | 31.6 | 8 | 60 | 90.1 | 84.6 | 96.7 | 72.3 | 6.8 | 100.0 | 87 | 1 | 100 |

| Drink items | 3.6 | 1 | 10 | 9.9 | 3.3 | 15.4 | 49.5 | 29.2 | 70.8 | 24 | 2 | 100 |

| Item form | ||||||||||||

| Fresh | 10.3 | 1 | 30 | 28.3 | 4.5 | 55.6 | 92.9 | 64.2 | 100.0 | 100 | 2 | 100 |

| Refrigerated or frozen | 0.6 | 0 | 2 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 6.5 | 39.3 | 24.3 | 54.3 | 36 | 7 | 99 |

| Shelf stable | 24.2 | 4 | 56 | 70.4 | 44.4 | 95.5 | 59.6 | 5.7 | 99.0 | 75 | 1 | 100 |

| Food-group categorya | ||||||||||||

| Fruit | 7.2 | 2 | 17 | 21.8 | 9.2 | 36.4 | 53.5 | 6.6 | 99.7 | 37 | 1 | 100 |

| Vegetable | 12.2 | 3 | 28 | 35.9 | 13.6 | 66.7 | 91.4 | 58.8 | 100.0 | 100 | 20 | 100 |

| Grain | 6.4 | 0 | 22 | 17.0 | 0.0 | 33.8 | 56.6 | 21.5 | 85.0 | 65 | 8 | 94 |

| Dairy | 1.9 | 0 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.0 | 9.8 | 81.6 | 72.0 | 94.1 | 89 | 28 | 100 |

| Protein | 5.4 | 1 | 13 | 16.5 | 6.5 | 31.8 | 66.4 | 37.2 | 89.1 | 77 | 25 | 100 |

| Other | 1.9 | 0 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.0 | 7.7 | 11.8 | 7.4 | 16.7 | 10 | 1 | 28 |

| Item source | ||||||||||||

| Food Bank | 12.7 | 0 | 53 | 37.3 | 0.0 | 86.4 | 67.3 | 21.5 | 96.5 | 83 | 1 | 100 |

| City Harvest | 6.1 | 0 | 27 | 13.0 | 0.0 | 52.9 | 76.3 | 19.2 | 99.8 | 100 | 2 | 100 |

| Corporations/ Businesses | 1.6 | 0 | 5 | 9.2 | 0.0 | 55.6 | 61.4 | 44.0 | 81.3 | 79.5 | 23 | 100 |

| Local Produce Link | 0.8 | 0 | 4 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 13.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Detailed item categoryb | ||||||||||||

| Fresh produce | 9.3 | 1 | 30 | 26.0 | 4.5 | 55.6 | 99.5 | 96.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 88 | 100 |

| Processed produce | 8.8 | 2 | 17 | 26.6 | 16.9 | 32.3 | 65.7 | 19.2 | 97.9 | 83 | 1 | 100 |

| Whole-grain products | 1.7 | 0 | 5 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 13.6 | 75.9 | 57.8 | 92.0 | 93 | 38 | 94 |

| Nuts | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cheese/yogurt | 0.7 | 0 | 3 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 6.5 | 50.6 | 33.0 | 70.5 | 38 | 28 | 99 |

| Red/processed meats | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 28.0 | 28.0 | 28.0 | 28 | 25 | 31 |

| Fish | 1.4 | 0 | 2 | 4.7 | 0.0 | 9.5 | 71.9 | 62.7 | 81.0 | 77 | 51 | 91 |

| Poultry | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 25 | 25 | 36 |

| Beans, lentils, legumes | 3.2 | 0 | 11 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 18.2 | 86.0 | 59.7 | 100.0 | 84 | 28 | 100 |

| Salty snacks | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sweet | 0.8 | 0 | 2 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 9.0 | 6.4 | 11.6 | 4 | 1 | 24 |

| Other refined-grain item | 4.8 | 0 | 17 | 12.2 | 0.0 | 26.2 | 49.0 | 21.5 | 77.8 | 51 | 8 | 93 |

| Milk | 1.2 | 0 | 3 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 4.8 | 90.0 | 87.8 | 93.3 | 89 | 82 | 100 |

| 100% juice | 1.6 | 0 | 4 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 13.6 | 19.6 | 15.0 | 24.8 | 24 | 6 | 29 |

| Sugary drinks | 0.7 | 0 | 3 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 4.6 | 9.3 | 8.0 | 10.5 | 10 | 2 | 20 |

| Diet drinks | 0.1 | 0 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Water/carbonated water | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Example items by food-group category (bold typeface = items not offered through pantries operating by prefilled bags):

Fruit = fresh fruits, 100% juices, applesauce, dried fruits, and canned fruits in syrups

Vegetable = fresh vegetables, fresh herbs, tomato-based pasta sauces, vegetable soups, instant potatoes, and canned vegetables and canned corn

Grain = hot and cold cereals, rice, breads, and pasta/noodles including ‘Mac and Cheese’

Dairy = dried milk, shelf-stable liquid milk, cottage cheese, and plain and flavored sweetened yogurts

Protein = canned meats and fish, canned soups and casseroles with meat, canned and dried beans and lentils and chickpeas, peanut butter

Other = sweetened cereals, sugar-added juice cocktails, fruit jellies and cranberry sauce, grain-based desserts, pudding, condensed soups including cheese soup, and sweetened teas

Example items by detailed item category (bold typeface = items not offered through pantries operating by prefilled bags):

Fresh produce = whole fresh fruits and vegetables and fresh herbs

Processed produce = tomato-based pasta sauces, vegetable soups, instant potatoes, canned vegetables canned corn, canned sweet fruits in syrups, applesauce, dried fruits

Whole gain = brown rice, cornmeal, oats and oatmeal, whole-wheat bread, whole-wheat pasta

Cheese/yogurt = cottage cheese, plain and flavored sweetened yogurts

Red and processed meats = beef ravioli, beef stew

Fish = canned salmon, tuna, mackerel, and sardines

Poultry = canned chicken, canned chicken soups, and whole refrigerated chickens

Beans, lentils, legumes = dried and canned beans, lentils, and chickpeas, peanut butter

Sweets = sweetened cereals, grain-based desserts, fruit jellies, puddings

Other refined grains = hot and cold refined cereals, white rice, white breads, and refined pasta/noodles, corn flakes

Milk = instant dried milk, shelf-stable liquid milk (1% or nonfat except for one instance of whole milk)

Juice = 100% apple, grape, grapefruit, or orange juice

Sugary drinks = sweetened teas, juice cocktails and concentrates

Diet drinks = pomegranate, berry, and guarana low-calorie juice drink

NOTE: There were no nuts, salty snacks (like potato chips and pretzels), or bottled water/carbonated water available.

At client-choice pantries, reported differences in availability for clients near the fronts of lines versus near the backs of lines could be substantial (Appendix - Tables 6 and 7). The mean number of items reportedly available for clients at the backs of lines was about 66% lower (11.0; versus. 34.6 reportedly available to clients at the fronts of lines). Yet the mean of all client-choice pantries’ mean NuVal® scores and the median NuVal® score across client-choice pantries were both higher for items reportedly available near the backs of lines (80.7 and 91 respectively; Appendix - Table 4) than near the fronts of lines (69.8 and 84 respectively; Appendix - Table 3). These differences reflected greater proportions of offerings reportedly coming from fresh vegetables near the backs of lines. The implication is that clients who have other items to select do not select fresh vegetables as often.

Table 3 shows NuVal® scores of the items at pantries with the highest, median, and lowest nutritional quality. The table also shows the best and worst-case scenarios for nutrition in ‘balanced baskets’--hypothetical collections of one of each fruit, vegetable, grain, dairy, and protein. Client-choice pantries had the highest-scoring NuVal® items in each MyPlate category, but also the lowest-scoring NuVal® items (with the exception of items in the protein category). If a client created a ‘balanced basket’ from the highest-scoring items across pantries, ‘balanced baskets’ would have near-perfect NuVal® scores both from client-choice and from traditional pantries (scores of 98.8 and 96.6, respectively). If a client created a ‘balanced basket’ from the lowest-scoring items across pantries, the result would be very poor nutrition from client-choice pantries (score of 16.4) and somewhat less-poor quality from pantries using prefilled bags (score of 35.4). Although not shown in the table, it is notable that 5.8% of all items at traditional pantries, and 6.3% of all items at client-choice pantries, had single-digit NuVal® scores (i.e., extremely poor nutritional quality).

Table 3.

Highest, median, and lowest-nutrition items, and best and worst-case nutritional quality for a ‘balanced basket’a from Bronx food pantries (n = 13)b

| NuVal® Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food-pantry items by MyPlate.gov food-group categories | Across all pantries | Across all prefilled-bag pantries | Across all ‘client choice’ pantries | Mean of all pantries’ highest or lowest score | Mean of all prefilled-bag pantries’ highest or lowest score | Mean of all ‘client choice’ pantries’ highest or lowest score |

| Highest-NuVal® itemc | ||||||

| Fruit | 100 | 100 | 100 | 85.6 | 69.3 | 99.6 |

| Vegetable | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98.3 | 96.3 | 100.0 |

| Grain | 94 | 94 | 94 | 83.7 | 74.0 | 92.0 |

| Dairy | 100 | 89 | 100 | 91.8 | 89.0 | 94.1 |

| Protein | 100 | 100 | 100 | 89.2 | 80.3 | 96.7 |

| Basket of all 5 items (mean) | 98.8 | 96.6 | 98.8 | 89.7 | 81.8 | 96.5 |

| Median-NuVal® item | ||||||

| Fruit | 49.5 | 32.5 | 67.5 | 55.1 | 44.8 | 63.9 |

| Vegetable | 100 | 99 | 100 | 93.9 | 88.5 | 98.6 |

| Grain | 65 | 84 | 65 | 63.6 | 61.6 | 65.3 |

| Dairy | 89 | 89 | 89 | 83.3 | 89.0 | 78.4 |

| Protein | 77 | 52 | 77 | 65.2 | 52.3 | 76.2 |

| Basket of all 5 items (mean) | 76.1 | 71.3 | 79.7 | 72.2 | 67.3 | 76.5 |

| Lowest-NuVal® itemd | ||||||

| Fruit | 1 | 4 | 1 | 12.5 | 22.0 | 4.4 |

| Vegetable | 20 | 55 | 20 | 60.6 | 70.5 | 52.1 |

| Grain | 8 | 9 | 8 | 32.5 | 44.8 | 21.9 |

| Dairy | 28 | 89 | 28 | 79.8 | 89.0 | 72.0 |

| Protein | 20 | 20 | 25 | 34.7 | 27.7 | 40.7 |

| Basket of all 5 items (mean) | 15.4 | 35.4 | 16.4 | 44.0 | 50.8 | 38.2 |

A’balanced basket’ is a hypothetical bundle of five items, one from each of the five MyPlate.gov food-group categories of fruit, vegetable, grain, dairy, and protein

Analyses here restricted to the pantries that offered at least one item from each of the 5 MyPlate.gov food-group categories: 6 pantries operating by the traditional prefilled-bag model and 7 pantries operating by a client-choice model. For an imputed analysis, considering all pantries at which any foods or drinks were being offered (12 pantries operating by a prefilled-bag model and nine operating by a client-choice model) and setting missing items to a NuVal® score of zero, please see Appendix - Table 5.

In the fruit and vegetables categories, fresh varieties--and canned varieties without added sodium--were among the items with NuVal® scores of 100 at pantries of both types. Brown rice was the whole-grain item with NuVal® score of 94 at both types of pantries. The dairy food with NuVal® of 89 at pantries using prefilled bags was 1% milk; fat-free milk (in either powdered or liquid form) was the dairy item with NuVal® score of 100 at client choice pantries. Scoring 100 in the protein category at pantries of both types were dried beans and lentils.

In the fruit category, sweetened dried cranberries had the NuVal® score of 4 and sweetened cranberry sauce had the NuVal® score of 1. For vegetables, diced, salted, canned tomatoes had the NuVal® score of 55, cut yams in light syrup had the NuVal® of 20. The grain item with NuVal® score of 9 was Mac and Cheese, the grain item with the NuVal® score of 8 was gluten-free tagliatelle. For dairy, 1% milk scored 89, and sweetened flavored yogurts scored the 28. The protein item having a NuVal® score of 20 was Vienna sausages, and the protein items having the NuVal® score of 25 were canned beef stew and canned chicken.

Values across pantries give a sense of overall inventory. However, from a client perspective, it may be more meaningful to consider scores for ‘balanced baskets’ that could come from single pantries (rather than from getting certain items from one pantry and other items form another). At a single pantry, items in the best possible ‘balanced baskets’ for prefilled bags would have a mean NuVal® score of 81.8, whereas items in the worst possible ‘balanced baskets’ would have a mean NuVal® score of only 50.8. At client-choice pantries, clients could select ‘balanced baskets’ scoring very high (mean NuVal® for the five basket items of 96.5), but could also select baskets scoring quite low (mean NuVal® of 38.2). Median values for five-item-mean scores were around 70 for both pantry types (slightly lower for traditional pantries and slightly higher for client-choice pantries).

The values in Table 3 are restricted to pantries that had items in all five of the MyPlate food-group categories (13 pantries; eight pantries fewer than the 21 having any foods or drinks to offer at all). If all assessed pantries are considered (including those without items to offer in some MyPlate food-group categories), and a NuVal® score of zero is assigned in categories where items were not available (absent items provide zero nutrition), the results are shown in Appendix - Table 5. While the results across all pantries are somewhat worse (‘balanced baskets’ having slightly lower nutritional quality), the results for a given traditional or client-choice pantry on average are not meaningfully different (‘balanced baskets’ having comparably high, median, and low mean NuVal® scores).

DISCUSSION

This study examined the nutritional quality of food and drink offerings from a sample of urban food pantries. Findings revealed that when pantries were open and had food or drink items to offer (in fewer than 50% of cases listed online by the local food bank), there were differences in nutritional quality based on item type and sourcing, and likely by distribution method and client position in line.

Fully 58% of pantries (29 of 50) offered no foods or drinks at all—either because they were closed when they were listed as being open or because they simply had no items in stock. These pantries provided precisely zero nutrition at listed times.

Among pantries that did have food or drink, more than a third (8 of 21) did not have any items in at least one of the five MyPlate.gov food-group categories. The suggestion is that, when available, foods and drinks might be lacking in variety and balance. Prior studies of food pantries have also identified lack of balance, for example due to deficits in food-group categories like dairy products, fruits, and vegetables.17,20–22

Even when pantries had items representing all five food-group categories, products in some categories may not have been of high nutritional quality. For example, canned fruit cocktail in syrup could have counted as “fruit,” and instant potatoes could have counted as “vegetable.” Two prior studies showed that most “fruits and vegetables” at pantries were highly processed items like sauces and juices.22,43

In the current study, the type and quality of fruits and vegetables were related to both distribution method and item suppliers. Pantries offering client choice had more fresh items, especially vegetables, and sourced more items from organizations connecting pantries to local farms and other sources of fresh produce. In contrast, traditional pantries handing out prefilled bags depended much more heavily on shelf-stable items from food bank deliveries.

Another difference between traditional and client-choice pantries was the range of products offered. Client-choice pantries offered a greater number of items, having a wider range of nutritional quality. Across all client-choice pantries (that had food), one could have theoretically assembled a ‘balanced basket’ of fruit, vegetable, grain, dairy, and protein having near perfect nutritional quality (NuVal® score of 98.8). However, one could have also theoretically assembled a ‘balanced basket’ of items with a mean NuVal® score of only 16.4. Across traditional pantries using prefilled bags, the range was 35.4–96.6. In a study of six client-choice pantries in Connecticut, less than half of all available products were in the green (choose often) category(One author and colleagues, under review) using a stoplight nutritional grading system.44 In the current study, 6% of items at pantries of either type (traditional or client choice) had NuVal® scores only in the single digits.

Inventories across pantries provide the total range of items available. A more applicable consideration for individual clients though is the inventory at a given pantry. At a given client-choice pantry (on average), the NuVal® score of ‘balanced basket’ could range from 38.2 (considering only the lowest-quality items) to 96.5 (considering only the highest-quality items). At a given traditional pantry using prefilled bags, the range was narrower and less extreme (50.8 – 81.8). While median NuVal® scores were around 70 for ‘balanced baskets’ from pantries of either type, where exactly in the range an actual client might land could depend on that client’s position in line. Pantries operating by both client choice and prefilled bags reportedly offered lower-nutrition items to clients near the fronts of lines versus near the backs of lines. This difference was especially pronounced at client-choice pantries. The implication at client-choice pantries is that clients choose lower-NuVal® items preferentially; the implication at traditional pantries is that workers provide lower-NuVal® items preferentially. Perhaps explaining both practices is pantry workers’ reported impressions of clients’ preferences; workers reported that clients preferred white rice and refined pasta, for example, over higher-nutrition alternatives like brown rice and whole-wheat pasta.

It is worth asking why individuals who are food-insecure would choose--or why pantry workers serving them would provide--less-nutritious items when there are healthier options available. One reason may be that nutrient density is not the most relevant concern for hungry people. Vegetables--as found at more client-choice pantries--often have perfect NuVal® scores, but may not be very filling. A study using focus group interviews showed that many pantry clients, especially those with children, seek more calorie-dense foods such as macaroni and cheese, peanut butter and jelly, sweet cereals, and white sandwich bread.45 Unfortunately, some such items are unlikely to be more filling and may even promote hunger,46 revealing that nutritional knowledge and confusion about healthy eating may play a role in pantry food provision. Other obstacles to healthier provision at pantries may relate to practical considerations: e.g., an appreciation that clients may lack cooking equipment, lack food-preparation knowledge, or be challenged by carrying heavier produce items long distances19,47–50(One author and colleagues, under review)). Ubiquitous advertising for unhealthful products likely also plays a role;51,52 such advertising extends even to mass transit stations in food-pantry communities.53 Cultural traditions (e.g. beans and white rice as opposed to beans and brown rice) may be important too.26,54 In prior research, food-pantry clients cited cultural appropriateness as an important factor in food choice, and they reported difficulty obtaining culturally appropriate foods from food pantries.45 From the perspective of pantry workers providing the food, concerns about scarcity or running out early--along with concerns for adverse reactions from clients who are towards the back of the line and forced to go without--might translate to setting limits up front and holding some provision of items until later in line.47,(One authors and colleagues, under review)

The current study had several strengths. First, investigators conducted exploratory visits to a sample of pantries before initiating data collection; in doing so, the team learned about key variables to include that were not considered in prior studies. Second, the study included a relatively large number of pantries and included findings about pantries not being open or not having food; these findings are important because foods and drinks offer precisely zero nutrition if they are absent. Third, the study assessed nutritional quality more comprehensively than in prior studies, using a validated nutritional scoring system that considers favorable and unfavorable components and that is supported by cohort-based morbidity and mortality data. Fourth, analyses included consideration of item type, sourcing, and distribution method, as well as clients’ position in line. Analyses also considered best- and worst-case scenarios for nutrition based on hypothetical ‘balanced baskets’ of food provision.

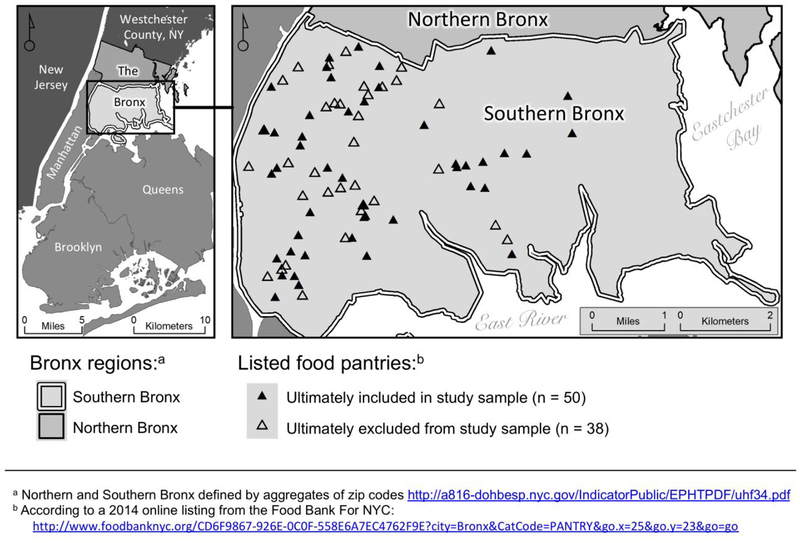

A limitation of the current study was the final sampling, restricted by pantry hours and locations. Nonetheless, the online listing of all food pantries31 reassured about comparable operating hours between included and excluded sites. Also, a map of all pantry locations (Appendix - Figure 1) reassured that included pantries reflected the full geographic distribution of pantries overall. The ultimate total of 50 included pantries might technically be described as a “convenience sample,” but would be comparable to a patient sample from a randomized clinical trial where inclusion is based on willingness and availability of eligible individuals to participate.

Another limitation of the current study was the cross-sectional design. Nonetheless, at least two visits were made to all pantries that were closed so findings on closures (pantries not being open as listed online) were based not just on single time points. Moreover, investigators attempted to visit initially closed pantries at other times when alternative hours were listed by on-site signage;26 pantries that were “closed” were closed on at least two occasions. When pantries were open, investigators asked workers not only about present conditions but also about typical conditions; workers reported that sourcing of fresh produce directly from local farms (e.g., through Local Produce Link) can vary seasonally but that other produce sourcing (as through City Harvest) is more stable. The end result might have been slightly less of a difference in fresh-produce availability between traditional pantries and client-choice pantries in the winter. From the standpoint of generalizability, pantries in other locations might have different sourcing and different offerings.

An additional limitation relates to not having data on the items clients actually received--either through their own choice or through handouts in prefilled bags (and, moreover, no data on the items clients--or their families--actually consumed, or what other food sources contributed to their overall nutrition on pantries days, at other times during the week, over the month, etc.). Future client-focused ethnographic research would be valuable in these areas. In the interim, the analyses in the current study provide best- and worst-case scenarios to bound the possibilities of foods received from pantries.

A final limitation relates less to the study itself and more to the nuance of applying nutritional scoring to a full range of pantry offerings. For example, fresh vegetables usually have perfect NuVal® scores and yet are not, in and of themselves, nutritionally complete. A pantry that provided only vegetables would score very near 100 for its inventory, but such a pantry would provide clients with a diet of inadequate balance. Thus, NuVal® scores across items should be interpreted cautiously. Our ‘balanced basket’ approach is one method to begin to address this limitation.

CONCLUSION

The current study showed substantial variation in the nutrition available from urban food pantries. In more than half of all cases, visited pantries were not open or had no items to distribute. When pantries did have foods and drinks, nutritional quality varied by item type and sourcing, and likely by distribution method and client position in line. Under worst-case scenarios, pantries could offer less-than-nutritious food and client preferences and worker practices could contribute to unhealthful food provision.

To help ensure better nutrition at more pantries at more times, increasing linkages to fresh produce—e.g. local farms or organizations that rescue fresh items from stores, restaurants, and manufacturers—could help. Manipulating displays to highlight nutritious items could support healthier selections when clients have a choice.44,55–57 Additionally, educational efforts may support client preferences for healthier items and workers’ willingness to make them available. Education for clients might include information on nutrition, introductions to new foods through cooking demonstrations and tastings, and sessions to build food-preparation skills.54 Facilities for food preparation may also be important.

Most important though will be efforts to ensure greater reliability in supply and provision. When it comes to nutrition, almost any food is better than no food, and adequacy is a chief concern. Future work should exam barriers to the regular provision and uptake of healthful items from pantries.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sarah O’Connor, RD, Manager of Imputation and Scoring, NuVal® LLC, for her assistance in providing nutrition scores for the food and drink items available at sampled food pantries.

Financial support

SCL is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award K23HD079606. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Student stipends through the Albert Einstein College of Medicine supported data collection. For data management, the study used REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted through the Harold and Muriel Block Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at Einstein and Montefiore under grant UL1 TR001073.

Appendix - Figure 1.

Food pantries in the southern Bronx included in and excluded from the study sample

Appendix - Figure 2.

Data-collection tool for food and drink assessments at food pantries

Appendix - Figure 3.

Montage of food and drink images from food pantries in the southern Bronx, 2014

Appendix - Table 1.

Type, sources, and nutrition quality of foods and drinks from Bronx food pantries using traditional prefilled bags (n = 12 pantries); foods reportedly available to clients near the front of the linea

| Number of items | Percentage of offerings | NuVal® scores by pantry | NuVal® across all pantries | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item characteristic | Mean n across pantries | Min n at any pantry | Max n at any pantry | Mean % across pantries | Min % at any pantry | Max % at any pantry | Mean of all pantries’ mean scores | Mean of all pantries’ min score | Mean of all pantries’ max score | Median score | Min score | Max score |

| Total items | 11.2 | 2 | 23 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 58.5 | 6.7 | 92.4 | 77 | 1 | 100 |

| Food or drink | ||||||||||||

| Food items | 10.0 | 2 | 21 | 88.7 | 66.7 | 100.0 | 62.5 | 17.4 | 92.4 | 77 | 1 | 100 |

| Drink items | 1.2 | 0 | 3 | 11.3 | 0.0 | 33.3 | 39.5 | 18.4 | 64.1 | 11 | 2 | 89 |

| Item form | ||||||||||||

| Fresh | 0.7 | 0 | 4 | 5.2 | 0.0 | 21.1 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Refrigerated or frozen | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Shelf stable | 10.5 | 2 | 23 | 94.8 | 78.9 | 100.0 | 56.0 | 6.7 | 90.9 | 67.5 | 1 | 100 |

| Food-group category | ||||||||||||

| Fruit | 2.6 | 0 | 9 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 47.4 | 53.1 | 32.6 | 71.3 | 62 | 4 | 100 |

| Vegetable | 2.5 | 1 | 5 | 25.7 | 11.1 | 50.0 | 79.9 | 65.8 | 89.1 | 99 | 10 | 100 |

| Grain | 2.4 | 0 | 8 | 17.7 | 0.0 | 34.8 | 65.3 | 47.8 | 80.4 | 84 | 9 | 94 |

| Dairy | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 3.7 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 89.0 | 89.0 | 89.0 | 89 | 89 | 89 |

| Protein | 2.4 | 1 | 7 | 23.8 | 6.3 | 50.0 | 52.5 | 37.5 | 65.4 | 54.5 | 20 | 100 |

| Other | 0.8 | 0 | 3 | 9.1 | 0.0 | 33.3 | 5.8 | 3.3 | 8.2 | 2.5 | 1 | 29 |

| Item source | ||||||||||||

| Food Bank | 7.5 | 0 | 23 | 71.8 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 60.1 | 5.8 | 90.7 | 84 | 1 | 100 |

| City Harvest | 0.2 | 0 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Corporations/ Businesses | 1.7 | 0 | 9 | 14.6 | 0.0 | 90.0 | 57.0 | 40.3 | 76.3 | 30 | 1 | 100 |

| Local Produce Link | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Detailed item category | ||||||||||||

| Fresh produce | 0.7 | 0 | 4 | 5.2 | 0.0 | 21.1 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Processed produce | 4.0 | 1 | 7 | 37.4 | 25.0 | 70.0 | 65.4 | 37.8 | 86.9 | 80 | 4 | 100 |

| Whole-grain products | 0.8 | 0 | 3 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 93.1 | 93.0 | 93.3 | 93 | 93 | 94 |

| Nuts | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cheese/yogurt | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Red/processed meats | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 7.2 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 26.0 | 26.0 | 26.0 | 24 | 20 | 31 |

| Fish | 0.7 | 0 | 3 | 5.1 | 0.0 | 13.0 | 68.2 | 60.8 | 75.2 | 71.5 | 51 | 91 |

| Poultry | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 28.4 | 28.4 | 28.4 | 25 | 20 | 43 |

| Beans, lentils, legumes | 0.8 | 0 | 3 | 8.5 | 0.0 | 33.3 | 75.2 | 68.4 | 81.0 | 84 | 29 | 100 |

| Salty snacks | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sweet | 0.5 | 0 | 2 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 3 | 1 | 12 |

| Other refined-grain item | 1.5 | 0 | 5 | 11.2 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 56.5 | 42.1 | 73.0 | 65 | 9 | 84 |

| Milk | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 3.7 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 89.0 | 89.0 | 89.0 | 89 | 89 | 89 |

| 100% juice | 0.5 | 0 | 2 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 9.3 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 10 | 6 | 12 |

| Sugary drinks | 0.3 | 0 | 1 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 33.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Diet drinks | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Water/carbonated water | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Pre-filled bags could reportedly vary in terms of size and content based on a client’s position in line; the values in this table are based on items pantry workers reported as among those that would be available to clients in the first bags of the day.

Appendix - Table2.

Type, sources, and nutrition quality of foods and drinks from Bronx food pantries using traditional prefilled bags (n = 12 pantries); foods reportedly available to clients near the back of the linea

| Number of items | Percentage of offerings | NuVal® scores by pantry | NuVal® across all pantries | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item characteristic | Mean n across pantries | Min n at any pantry | Max n at any pantry | Mean % across pantries | Min % at any pantry | Max % at any pantry | Mean of all pantries’ mean scores | Mean of all pantries’ min score | Mean of all pantries’ max score | Median score | Min score | Max score |

| Total items | 9.0 | 1 | 23 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 60.7 | 13.8 | 89.8 | 83 | 1 | 100 |

| Food or drink | ||||||||||||

| Food items | 7.9 | 1 | 21 | 85.3 | 50.0 | 100.0 | 66.4 | 28.5 | 89.8 | 84 | 1 | 100 |

| Drink items | 1.1 | 0 | 2 | 14.7 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 37.6 | 17.6 | 57.6 | 11 | 2 | 89 |

| Item form | ||||||||||||

| Fresh | 0.3 | 0 | 1 | 9.7 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Refrigerated or frozen | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Shelf stable | 8.8 | 0 | 23 | 90.3 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 56.7 | 6.0 | 88.9 | 77 | 1 | 100 |

| Food-group category | ||||||||||||

| Fruit | 1.8 | 0 | 4 | 22.6 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 55.1 | 31.3 | 75.0 | 62 | 4 | 99 |

| Vegetable | 2.0 | 0 | 5 | 29.2 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 78.9 | 66.5 | 88.3 | 95 | 10 | 100 |

| Grain | 2.1 | 0 | 8 | 15.6 | 0.0 | 34.8 | 73.8 | 56.3 | 88.6 | 84 | 9 | 94 |

| Dairy | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 3.7 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 89.0 | 89.0 | 89.0 | 89 | 89 | 89 |

| Protein | 1.8 | 0 | 7 | 19.9 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 54.4 | 39.8 | 67.1 | 62 | 24 | 100 |

| Other | 0.8 | 0 | 3 | 9.1 | 0.0 | 33.3 | 8.4 | 6.3 | 10.4 | 3 | 1 | 29 |

| Item source | ||||||||||||

| Food Bank | 7.8 | 0 | 23 | 74.1 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 60.4 | 6.2 | 91.6 | 84 | 1 | 100 |

| City Harvest | 0.2 | 0 | 1 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Corporations/ Businesses | 0.5 | 0 | 6 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 18.7 | 1.0 | 29.0 | 21.5 | 1 | 29 |

| Local Produce Link | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Detailed item category | ||||||||||||

| Fresh produce | 0.3 | 0 | 1 | 9.7 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Processed produce | 3.2 | 0 | 7 | 35.2 | 0.0 | 70.0 | 69.7 | 44.8 | 85.5 | 88 | 4 | 100 |

| Whole-grain products | 0.8 | 0 | 3 | 6.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 93.1 | 93.0 | 93.3 | 93 | 93 | 94 |

| Nuts | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cheese/yogurt | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Red/processed meats | 0.3 | 0 | 1 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 26.3 | 26.3 | 26.3 | 24 | 24 | 31 |

| Fish | 0.4 | 0 | 3 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 13.0 | 72.8 | 67.0 | 78.0 | 77 | 58 | 91 |

| Poultry | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 29.4 | 29.4 | 29.4 | 25 | 25 | 43 |

| Beans, lentils, legumes | 0.8 | 0 | 3 | 8.4 | 0.0 | 33.3 | 78.6 | 66.6 | 89.6 | 92 | 29 | 100 |

| Salty snacks | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sweet | 0.5 | 0 | 2 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 7 | 1 | 24 |

| Other refined-grain item | 1.3 | 0 | 5 | 9.7 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 64.9 | 51.0 | 81.3 | 65 | 9 | 84 |

| Milk | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 3.7 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 89.0 | 89.0 | 89.0 | 89 | 89 | 89 |

| 100% juice | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 6.9 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 10 | 6 | 12 |

| Sugary drinks | 0.3 | 0 | 1 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 33.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Diet drinks | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Water/carbonated water | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Pre-filled bags could reportedly vary in terms of size and content based on a client’s position in line; the values in this table are based on items pantry workers reported as among those that would be available to clients in the last bags of the day.

Appendix - Table 3.

Type, sources, and nutrition quality of foods and drinks from Bronx food pantries for using ‘client choice’ (n = 9 pantries); foods reportedly available to clients near the front of the linea

| Number of items | Percentage of offerings | NuVal® scores by pantry | NuVal® across all pantries | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item characteristic | Mean n across pantries | Min n at any pantry | Max n at any pantry | Mean % across pantries | Min % at any pantry | Max % at any pantry | Mean of all pantries’ mean scores | Mean of all pantries’ min score | Mean of all pantries’ max score | Median score | Min score | Max score |

| Total items | 34.6 | 9 | 65 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 69.8 | 5.7 | 100.0 | 84 | 1 | 100 |

| Food or drink | ||||||||||||

| Food items | 31.0 | 8 | 60 | 89.9 | 84.6 | 96.7 | 72.9 | 6.8 | 100.0 | 88 | 1 | 100 |

| Drink items | 3.6 | 1 | 10 | 10.1 | 3.3 | 15.4 | 49.5 | 29.2 | 70.8 | 24 | 2 | 100 |

| Item form | ||||||||||||

| Fresh | 10.1 | 1 | 30 | 28.3 | 4.5 | 55.6 | 93.4 | 64.4 | 100.0 | 100 | 2 | 100 |

| Refrigerated or frozen | 0.4 | 0 | 2 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 6.5 | 45.0 | 22.5 | 67.5 | 37 | 7 | 99 |

| Shelf stable | 24.0 | 4 | 56 | 70.6 | 44.4 | 95.5 | 59.8 | 5.7 | 99.0 | 76 | 1 | 100 |

| Food-group category | ||||||||||||

| Fruit | 7.2 | 2 | 17 | 22.1 | 9.2 | 36.4 | 53.5 | 6.6 | 99.7 | 37 | 1 | 100 |

| Vegetable | 12.0 | 3 | 28 | 35.7 | 13.6 | 66.7 | 92.5 | 61.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 20 | 100 |

| Grain | 6.4 | 0 | 22 | 17.3 | 0.0 | 33.8 | 56.6 | 21.5 | 85.0 | 65 | 8 | 94 |

| Dairy | 1.6 | 0 | 4 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 6.5 | 86.9 | 80.7 | 94.1 | 89 | 38 | 100 |

| Protein | 5.4 | 1 | 13 | 16.6 | 6.5 | 31.8 | 66.4 | 37.2 | 89.1 | 77 | 25 | 100 |

| Other | 1.9 | 0 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.0 | 7.7 | 11.8 | 7.4 | 16.7 | 10 | 1 | 28 |

| Item source | ||||||||||||

| Food Bank | 12.6 | 0 | 53 | 37.2 | 0.0 | 85.7 | 67.5 | 21.5 | 96.5 | 83.5 | 1 | 100 |

| City Harvest | 5.8 | 0 | 24 | 12.8 | 0.0 | 51.1 | 77.7 | 19.2 | 99.8 | 100 | 2 | 100 |

| Corporations/ Businesses | 1.6 | 0 | 5 | 9.2 | 0.0 | 55.6 | 61.4 | 44.0 | 81.3 | 79.5 | 23 | 100 |

| Local Produce Link | 0.8 | 0 | 4 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Detailed item category | ||||||||||||

| Fresh produce | 9.3 | 1 | 30 | 26.5 | 4.5 | 55.6 | 99.5 | 96.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 88 | 100 |

| Processed produce | 8.6 | 2 | 17 | 26.2 | 16.9 | 32.3 | 66.2 | 19.2 | 97.9 | 83 | 1 | 100 |

| Whole-grain products | 1.7 | 0 | 5 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 75.9 | 57.8 | 92.0 | 93 | 38 | 94 |

| Nuts | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cheese/yogurt | 0.3 | 0 | 2 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 6.5 | 68.5 | 38.0 | 99.0 | 68.5 | 38 | 99 |

| Red/processed meats | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 28.0 | 28.0 | 28.0 | 28 | 25 | 31 |

| Fish | 1.4 | 0 | 2 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 9.5 | 71.9 | 62.7 | 81.0 | 77 | 51 | 91 |

| Poultry | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 25 | 25 | 36 |

| Beans, lentils, legumes | 3.2 | 0 | 11 | 8.4 | 0.0 | 18.2 | 86.0 | 59.7 | 100.0 | 84 | 28 | 100 |

| Salty snacks | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sweet | 0.8 | 0 | 2 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 9.0 | 6.4 | 11.6 | 4 | 1 | 24 |

| Other refined-grain item | 4.8 | 0 | 17 | 12.4 | 0.0 | 26.2 | 49.0 | 21.5 | 77.8 | 51 | 8 | 93 |

| Milk | 1.2 | 0 | 3 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 4.8 | 90.0 | 87.8 | 93.3 | 89 | 82 | 100 |

| 100% juice | 1.6 | 0 | 4 | 5.7 | 0.0 | 13.6 | 19.6 | 15.0 | 24.8 | 24 | 6 | 29 |

| Sugary drinks | 0.7 | 0 | 3 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 4.6 | 9.3 | 8.0 | 10.5 | 10 | 2 | 20 |

| Diet drinks | 0.1 | 0 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Water/carbonated water | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Options available for selection in a ‘client choice’ model often reportedly depended on a client’s position in line; the values in this table are based on items pantry workers reported as among those that would be available to clients at the start of a pantry session.

Appendix - Table 4.

Type, sources, and nutrition quality of foods and drinks from Bronx food pantries for using ‘client choice’ (n = 9 pantries); foods reportedly available to clients near the back of the linea

| Number of items | Percentage of offerings | NuVal® scores by pantry | NuVal® across all pantries | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item characteristic | Mean n across pantries | Min n at any pantry | Max n at any pantry | Mean % across pantries | Min % at any pantry | Max % at any pantry | Mean of all pantries’ mean scores | Mean of all pantries’ min score | Mean of all pantries’ max score | Median score | Min score | Max score |

| Total items | 11.0 | 2 | 20 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 80.7 | 34.2 | 100.0 | 91 | 1 | 100 |

| Food or drink | ||||||||||||

| Food items | 10.0 | 2 | 18 | 92.1 | 84.6 | 100.0 | 80.4 | 34.2 | 100.0 | 93 | 1 | 100 |

| Drink items | 1.0 | 0 | 2 | 7.9 | 0.0 | 15.4 | 75.8 | 65.0 | 86.7 | 85.5 | 24 | 89 |

| Item form | ||||||||||||

| Fresh | 3.0 | 1 | 5 | 39.7 | 14.3 | 100.0 | 99.9 | 99.6 | 100.0 | 100 | 99 | 100 |

| Refrigerated or frozen | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Shelf stable | 8.0 | 0 | 17 | 60.3 | 0.0 | 85.7 | 67.9 | 17.8 | 98.5 | 84 | 1 | 100 |

| Food-group category | ||||||||||||

| Fruit | 1.8 | 0 | 4 | 11.7 | 0.0 | 23.1 | 70.4 | 42.3 | 99.7 | 62.5 | 4 | 100 |

| Vegetable | 4.2 | 1 | 7 | 47.3 | 14.3 | 100.0 | 93.5 | 71.6 | 100.0 | 100 | 40 | 100 |

| Grain | 2.4 | 0 | 5 | 21.0 | 0.0 | 57.1 | 69.7 | 24.0 | 93.3 | 88.5 | 15 | 94 |

| Dairy | 0.6 | 0 | 1 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 86.7 | 86.7 | 86.7 | 89 | 82 | 89 |

| Protein | 1.8 | 0 | 3 | 13.5 | 0.0 | 23.1 | 58.4 | 52.3 | 64.8 | 77 | 28 | 100 |

| Other | 0.2 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Item source | ||||||||||||

| Food Bank | 6.0 | 0 | 17 | 44.9 | 0.0 | 85.7 | 70.0 | 17.3 | 98.0 | 86 | 1 | 100 |

| City Harvest | 1.2 | 0 | 3 | 27.5 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Corporations/ Businesses | 0.4 | 0 | 2 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 15.4 | 79.5 | 75.0 | 84.0 | 79.5 | 75 | 84 |

| Local Produce Link | 0.6 | 0 | 3 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 15.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Detailed item category | ||||||||||||

| Fresh produce | 3.0 | 1 | 5 | 39.7 | 14.3 | 100.0 | 99.9 | 99.6 | 100.0 | 100 | 99 | 100 |

| Processed produce | 2.6 | 0 | 6 | 16.8 | 0.0 | 38.5 | 69.8 | 32.0 | 97.0 | 69 | 4 | 100 |

| Whole-grain products | 1.4 | 0 | 4 | 15.0 | 0.0 | 57.1 | 88.5 | 74.7 | 93.3 | 93 | 38 | 94 |

| Nuts | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cheese/yogurt | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Red/processed meats | 0.2 | 0 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 7.7 | 31.0 | 31.0 | 31.0 | 31 | 31 | 31 |

| Fish | 0.4 | 0 | 2 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 84.0 | 77.0 | 91.0 | 84 | 77 | 91 |

| Poultry | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Beans, lentils, legumes | 1.2 | 0 | 3 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 23.1 | 60.8 | 58.0 | 64.3 | 79.5 | 28 | 100 |

| Salty snacks | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sweet | 0.2 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Other refined-grain item | 1.0 | 0 | 3 | 6.1 | 0.0 | 15.4 | 48.3 | 17.0 | 84.0 | 36 | 15 | 84 |

| Milk | 0.6 | 0 | 1 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 86.7 | 86.7 | 86.7 | 89 | 82 | 89 |

| 100% juice | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 7.7 | 24.0 | 24.0 | 24.0 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| Sugary drinks | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Diet drinks | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Water/carbonated water | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Options available for selection in a ‘client choice’ model often reportedly depended on a client’s position in line; the values in this table are based on items pantry workers reported as among those that would be available to clients at the end of a pantry session.

Appendix - Table 5.

Highest, median, and lowest-nutrition items, and best and worst-case nutritional quality for a ‘balanced basket’a from Bronx food pantries (n = 21)b

| NuVal® Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food-pantry items by MyPlate.gov food-group categories | Across all pantries | Across all prefilled-bag pantries | Across all ‘client choice’ pantries | Mean of all pantries’ highest or lowest score | Mean of all prefilled-bag pantries’ highest or lowest score | Mean of all ‘client choice’ pantries’ highest or lowest score |

| Highest-NuVal® item | ||||||

| Fruit | 100 | 100 | 100 | 82.2 | 69.1 | 99.7 |

| Vegetable | 100 | 100 | 100 | 93.9 | 89.3 | 100.0 |

| Grain | 94 | 94 | 94 | 78.3 | 73.5 | 75.6 |

| Dairy | 100 | 89 | 100 | 85.2 | 76.3 | 82.4 |

| Protein | 100 | 100 | 100 | 77.2 | 68.3 | 89.1 |

| Basket of all 5 items (mean) | 98.8 | 96.6 | 98.8 | 83.4 | 75.3 | 89.3 |

| Median-NuVal® item | ||||||

| Fruit | 37 | 37 | 37 | 52.7 | 47.9 | 37 |

| Vegetable | 100 | 99 | 100 | 89.1 | 82.1 | 100 |

| Grain | 65 | 84 | 65 | 60.5 | 60.8 | 65 |

| Dairy | 89 | 44.5 | 89 | 77.3 | 76.3 | 89 |

| Protein | 75 | 51.5 | 77 | 59.8 | 52.6 | 75 |

| Basket of all 5 items (mean) | 73.2 | 63.2 | 73.6 | 67.9 | 63.9 | 73.2 |

| Lowest-NuVal® item | ||||||

| Fruit | 0 | 0 | 1 | 17.7 | 26.1 | 6.6 |

| Vegetable | 10 | 10 | 20 | 62.6 | 65.4 | 58.8 |

| Grain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35.1 | 45.0 | 19.1 |

| Dairy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 74.1 | 76.3 | 63.0 |

| Protein | 20 | 20 | 25 | 36.8 | 36.5 | 37.2 |

| Basket of all 5 items (mean) | 6.0 | 6.0 | 9.2 | 45.3 | 49.9 | 36.9 |

A’balanced basket’ is a hypothetical bundle of five items, one from each of the five MyPlate.gov food-group categories of fruit, vegetable, grain, dairy, and protein

Analyses here were imputed for pantries not offering at least one of item from each of the 5 MyPlate.gov food-group categories: six pantries operating by a prefilled-bag model and two pantries operating by a client-choice model. For imputation, NuVal® scores were set to zero for missing items.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None of the other authors have any disclosures.

Ethical Standards Disclosure

This study was considered exempt under federal regulations 45 CFR 46.101 (b) (2,4) and Einstein IRB policy

References

- 1.Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2016 - A report summary from the Economic Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture. September 2017; https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/84973/err237_summary.pdf?v=42979. Accessed June 11, 2018.

- 2.Jyoti DF, Frongillo EA, Jones SJ. Food insecurity affects school children’s academic performance, weight gain, and social skills. The Journal of nutrition. 2005;135(12):2831–2839, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shankar P, Chung R, Frank DA. Association of Food Insecurity with Children’s Behavioral, Emotional, and Academic Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J Dev Behav Pediatr. Feb-Mar 2017;38(2):135–150, PMCID: 28134627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA. Family food insufficiency, but not low family income, is positively associated with dysthymia and suicide symptoms in adolescents. The Journal of nutrition. 2002;132(4):719–725, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ke J, Ford-Jones EL. Food insecurity and hunger: A review of the effects on children’s health and behaviour. Paediatr Child Health. March 2015;20(2):89–91, PMCID: PMC4373582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. February 2010;140(2):304–310, PMCID: PMC2806885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seligman H, Bindman A, Vittinghoff E, Kanaya A, Kushel M. Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(1):5, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaemsiri S, Olson EC, He K, Kerker BD. Food concern and its associations with obesity and diabetes among lower-income New Yorkers. Public health nutrition. 2012;15(1):39–47, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):6–9, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkpatrick SI, McIntyre L, Potestio ML. Child hunger and long-term adverse consequences for health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. August 2010;164(8):754–762, PMID [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gundersen C, Kreider B. Bounding the effects of food insecurity on children’s health outcomes. J Health Econ. September 2009;28(5):971–983, PMID [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryu JH, Bartfeld JS. Household food insecurity during childhood and subsequent health status: the early childhood longitudinal study--kindergarten cohort. Am J Public Health. November 2012;102(11):e50–55, PMCID: PMC3477974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robaina KA, Martin KS. Food insecurity, poor diet quality, and obesity among food pantry participants in Hartford, CT. J Nutr Educ Behav. March 2013;45(2):159–164, PMID [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kempson K, Keenan DP, Sadani PS, Adler A. Maintaining food sufficiency: Coping strategies identified by limited-resource individuals versus nutrition educators. J Nutr Educ Behav. Jul-Aug 2003;35(4):179–188, PMID [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daponte BO, Lewis GH, Sanders S, Taylor L. Food pantry use among low-income households in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 1998;30(1):50–57, [Google Scholar]

- 16.Food Bank of Central New York. Food Bank vs. Food Pantry. 2018; https://www.foodbankcny.org/about-us/food-bank-vs-food-pantry/. Accessed May 6, 2018.

- 17.Irwin JD, Ng VK, Rush TJ, Nguyen C, He M. Can food banks sustain nutrient requirements? A case study in Southwestern Ontario. Canadian Journal of Public Health/Revue Canadienne de Sante’e Publique. 2007:17–20, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akobundu UO, Cohen NL, Laus MJ, Schulte MJ, Soussloff MN. Vitamins A and C, calcium, fruit, and dairy products are limited in food pantries. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104(5):811–813, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greger J, Maly A, Jensen N, Kuhn J, Monson K, Stocks R. Food pantries can provide nutritionally adequate food packets but need help to become effective referral units for public assistance programs. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2002;102(8):1126–1128, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jessri M, Abedi A, Wong A, Eslamian G. Nutritional quality and price of food hampers distributed by a campus food bank: A Canadian experience. Journal of health, population, and nutrition. 2014;32(2):287, [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Reilly S, O’Shea T, Bhusumane S. Nutritional vulnerability seen within asylum seekers in Australia. Journal of immigrant and minority health. 2012;14(2):356–360, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Starkey LJ. An evaluation of emergency food bags. Journal of the Canadian Dietetic Association (Canada). 1994, [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nanney MS, Grannon KY, Cureton C, Hoolihan C, Janowiec M, Wang Q, Warren C, King RP. Application of the Healthy Eating Index-2010 to the hunger relief system. Public Health Nutr. November 2016;19(16):2906–2914, PMID [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grannon KY, Hoolihan C, Wang Q, Warren C, King RP, Nanney MS. Comparing the Application of the Healthy Eating Index–2005 and the Healthy Eating Index–2010 in the Food Shelf Setting. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 2017/01/02 2017;12(1):112–122, [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simmet A, Depa J, Tinnemann P, Stroebele-Benschop N. The Dietary Quality of Food Pantry Users: A Systematic Review of Existing Literature. J Acad Nutr Diet. April 2017;117(4):563–576, PMID [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ginsburg ZA, Bryan AD, Rubinstein EB, Frankel HJ, Maroko AR, Schechter CB, Cooksey Stowers K, Lucan SC. Unreliable and Difficult-to-Access Food for Those in Need: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study of Urban Food Pantries. J Community Health. July 17 2018, PMID [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. County Health Rankings and Roadmaps: Building a Culture of Health, County by County - New York: Bronx. 2017; http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/new-york/2017/rankings/bronx/county/outcomes/overall/snapshot. Accessed February 26, 2018.

- 28.Austensen M, Been V, O’Regan KM, Rosoff S, Yager J. State of New York City’s Housing and Neighborhoods, 2016 Focus: Poverty in New York City. NYU Furman Center; http://furmancenter.org/files/sotc/SOC_2016_FOCUS_Poverty_in_NYC.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunger Free America. One in Three Bronx Children Still Living in Food Insecure Households. 2016.

- 30.Health NYC. Community Health Survey, 2002–2016. https://a816-healthpsi.nyc.gov/epiquery/CHS/CHSXIndex.html Accessed January 8, 2018.

- 31.Food Bank for New York City. Find Food Pantries. http://www.foodbanknyc.org/CD6F9867-926E-0C0F-558E6A7EC4762F9E?city=Bronx&CatCode=PANTRY&go.x=25&go.y=23&go=go. Accessed June 2, 2014.

- 32.Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Sanon O, Frias R, Schechter CB. Urban farmers’ markets: accessibility, offerings, and produce variety, quality, and price compared to nearby stores. Appetite. July 2015;90:23–30, PMCID: PMC4410073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lucan SC, Varona M, Maroko AR, Bumol J, Torrens L, Wylie-Rosett J. Assessing mobile food vendors (a.k.a. street food vendors)--methods, challenges, and lessons learned for future food-environment research. Public health. August 2013;127(8):766–776, PMCID: PMC3759625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Bumol J, Varona M, Torrens L, Schechter CB. Mobile food vendors in urban neighborhoods-implications for diet and diet-related health by weather and season. Health & place. May 2014;27:171–175, PMCID: PMC4017652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucan SC, Maroko A, Shanker R, Jordan WB. Green Carts (mobile produce vendors) in the Bronx--optimally positioned to meet neighborhood fruit-and-vegetable needs? Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. October 2011;88(5):977–981, PMCID: PMC3191209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Seitchik JL, Yoon DH, Sperry LE, Schechter CB. Unexpected Neighborhood Sources of Food and Drink: Implications for Research and Community Health. Am J Prev Med. June 11 2018, PMID [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Seitchik JL, Yoon D, Sperry LE, Schechter CB. Sources of Foods That Are Ready-to-Consume (‘Grazing Environments’) Versus Requiring Additional Preparation (‘Grocery Environments’): Implications for Food-Environment Research and Community Health. J Community Health. March 14 2018, PMID [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. April 2009;42(2):377–381, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katz DL, Njike VY, Faridi Z, Rhee LQ, Reeves RS, Jenkins DJ, Ayoob KT. The stratification of foods on the basis of overall nutritional quality: the overall nutritional quality index. Am J Health Promot. Nov-Dec 2009;24(2):133–143, PMID [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katz DL, Njike VY, Rhee LQ, Reingold A, Ayoob KT. Performance characteristics of NuVal and the Overall Nutritional Quality Index (ONQI). Am J Clin Nutr. April 2010;91(4):1102S–1108S, PMID [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiuve SE, Sampson L, Willett WC. The association between a nutritional quality index and risk of chronic disease. Am J Prev Med. May 2011;40(5):505–513, PMCID: PMC3100735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.United States Department of Agriculture. ChooeMyPlate.gov. https://www.choosemyplate.gov/. Accessed February 28, 2018.

- 43.Willows ND, Au V. Nutritional quality and price of university food bank hampers. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research. 2006;67(2):104–107, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin KS, Wolff M, Callahan K, Schwartz MB. Supporting Wellness at Pantries: Development of a Nutrition Stoplight System for Food Banks and Food Pantries. J Acad Nutr Diet. May 1 2018, PMID [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verpy H, Smith C, Reicks M. Attitudes and behaviors of food donors and perceived needs and wants of food shelf clients. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2003;35(1):6–15, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ball SD, Keller KR, Moyer-Mileur LJ, Ding Y-W, Donaldson D, Jackson WD. Prolongation of satiety after low versus moderately high glycemic index meals in obese adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):488–494, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cooksey-Stowers K, Read M, Wolff M, Martin K, Schwartz M. Food Pantry Staff Perceptions of Using a Nutrition Rating System to Guide Client Choice. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition. (In Press), [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones CL, Ksobiech K, Maclin K. “They Do a Wonderful Job of Surviving”: Supportive Communication Exchanges Between Volunteers and Users of a Choice Food Pantry. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 2017:1–21,28491205 [Google Scholar]