Abstract

Context:

Cathepsin S (CTSS) activity is elevated in Sjögren’s Syndrome (SS) patient tears.

Objective:

To evaluate longitudinal expression of tear and tissue CTSS activity relative to other disease indicators in Non-Obese Diabetic (NOD) mice.

Methods:

CTSS activity was measured in tears and lacrimal glands (LG) from male 1–6 month (M) NOD and 1 and 6M BALB/c mice. Lymphocytic infiltration was quantified by histopathology, while disease-related proteins (Rab3D, CTSS, collagen 1) were quantified using q-PCR and immunofluorescence.

Results:

In NOD LG, lymphocytic infiltration was noted by 2M and established by 3M (P<0.01). IFN-ɣ, TNF-α, and MHC II expression were increased by 2M (P<0.01). Tear CTSS activity was significantly elevated at 2M (P<0.001) to a maximum of 10.1-fold by 6M (P<0.001). CTSS activity in LG lysates was significantly elevated by 2M (P<0.001) to a maximum of 14-fold by 3M (P<0.001). CTSS and Rab3D immunofluorescence were significantly increased and decreased maximally in LG acini by 3M and 2M, respectively. Comparable changes were not detected between 1 and 6M BALB/c mouse LG, although Collagen 1 was decreased by 6M in LG of both strains.

Conclusion:

Tear CTSS activity is elevated with other early disease indicators, suggesting potential as an early stage biomarker for SS.

Keywords: Cathepsin S, Non-obese diabetic mouse, Lacrimal gland, Sjögren’s Syndrome, Dacryoadenitis, Autoimmune inflammation

Introduction

The autoimmune disease, Sjögren’s Syndrome (SS), is characterized by lymphocytic infiltration and altered secretory function of lacrimal gland (LG) and salivary gland (SG), causing autoimmune-mediated dry eye and dry mouth, respectively [1, 2]. SS is a chronic systemic disease, with patients experiencing additional symptoms of weight loss, fatigue, and inflammation of the heart, kidney, brain, lungs, liver, nervous system, and/or gastrointestinal tract which can worsen over time [3, 4]. SS patients are also 44 times more likely to develop non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphoma, which in turn may lead to high-grade malignant tumors [5, 6]. SS can be classified into primary (pSS) and secondary (sSS) disease, based on the development of symptoms in the absence or presence, respectively, of other autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [7, 8]

SS occurs in males and females of all ages, but the majority of patients diagnosed are middle-aged women with a male to female ratio of 1:10 [9]; however, ocular and extra-glandular complications may be more serious in men [10]. Despite being the second most common autoimmune rheumatic disease in the United States, a large subset of SS patients are estimated to remain undiagnosed due to a lack of specific classification criteria and biomarkers [11]. Several classification criteria have been proposed but lack proper validation. In 2002, American and European experts in SS set forth classification criteria that included oral and ocular symptoms, histopathology of SG to confirm lymphocytic infiltration, and elevated serum markers like autoantibodies to Ro (SSA) and La (SSB) [12]. However, none of these classifications were endorsed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) or the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) until, in 2012, the Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance (SICCA) registry developed new classification criteria, which were endorsed by the ACR in the interim [13]. Most recently, in 2016, a set of new classification criteria were developed and endorsed by the ACR and EULAR based primarily on hallmark symptoms like histological evaluations and autoantibody profiles [14]. Each of these “gold standard” criteria has its own drawbacks, ranging from a lack of specificity to SS to the need for use of invasive methods and the high costs of the assay. Even with these criteria, it still takes ~3.5 years to diagnose a SS patient (source: https://www.sjogrens.org/home/about-the-foundation/breakthroughgoal-/4yearupdate). Hence, there continues to be a need for specific and non-invasive diagnostic markers for timely diagnosis of SS.

Of the many mouse models of SS, the NOD mouse is one of the most widely utilized, as it spontaneously develops most of the attributes of SS in humans such as elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines, lymphocytic infiltration of LG and SG, and low secretory flow [15–17]. This model has also provided important insights into the changes in gene and protein expression in affected exocrine glands in human SS [18, 19], leading to insights into mechanisms of disease development. These mice demonstrate increased levels of the serum autoantibodies SSA (anti-Ro) and SSB (anti-La), components of the current classification criteria [20]. The development of autoimmune dacryoadenitis in male NOD mice is much more prominent than in females, while inflammation of pancreas and submandibular gland, leading to insulitis and submandibularitis, respectively, develops earlier and to a greater extent in female NOD mice relative to males [21, 22]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the LG in NOD mice is normal at 3–4 weeks of age but that by 6–8 weeks of age lymphocytic infiltration begins while manifestation of symptoms such as reduced tear flow and increased corneal fluorescein staining is detected by 12–16 weeks of age. Extensive destruction of the LG is reported at 28 weeks in male NOD mice [23, 24]. The presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, and IL-18 paralleling lymphocytic infiltration of exocrine glands in mouse models of SS and human patients is well studied [20, 25, 26], and a plethora of knockout NOD mouse models have been used to study the roles of these cytokines in the pathogenesis of SS [27–29]. It is also well-established in male NOD mice that expression levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10 and MHC-II are elevated in the LG whereas levels of ECM markers such as collagen 1 and 3 are decreased during the progression of autoimmune dacryoadenitis [30, 31].

The main focus of this study is a cysteine protease, cathepsin S (CTSS), which we have shown is elevated in LG lysates and tears of male NOD mice aged 12 weeks relative to age- and gender- matched controls [30]. We subsequently demonstrated elevated tear CTSS in diagnosed female SS patients in comparison to age- and gender-matched healthy controls and in comparison, to patients with other autoimmune or eye diseases [32, 33]. These clinical findings derived from preclinical studies in the NOD model thus suggested that tear CTSS has potential as a non-invasive diagnostic marker for SS. However, the relationship between elevated tear and LG CTSS with disease pathogenesis and progression has not been previously determined. The purpose of the present study is to investigate the relationship between increased CTSS expression and activity in tears and LG to the onset and progression of autoimmune dacryoadenitis, and to correlate this with other indicators of SS in male NOD mice. Insights from this work will shed light on the utility of this potential tear biomarker in clinical SS populations.

Materials and Methods

Animals:

NOD/ShiLtJ (001976) mice obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and BALB/c mice obtained from Charles River Laboratories were housed, and aged in the vivarium facilities at the University of Southern California. All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the University of Southern California Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), and in accordance with the ARVO statement for Animal Use in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. In the current study, male NOD mice aged 1 to 6 months (M) and male BALB/c mice aged 1 and 6 M were used. 12–15 male NOD mice, each at the experimental time points of 1 M, 2 M, 3 M, 4 M, 5 M and 6 M, and 10 male BALB/c mice, each at experimental time points of 1 M and 6 M were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 50–60 mg of Ketamine and 5–10 mg of Xylazine per kg of body weight. Tears were collected from these mice by stimulating with 3 μl of 50 μM CCH as described below and used for the CTSS activity assay. After tear collection, the mice were immediately euthanized by cervical dislocation. The LG pair was retrieved, and the tissues were divided with one LG allocated for biochemistry to accommodate either lysate preparation for CTSS activity assays, or mRNA extraction for expression analysis of CTSS, IFN-γ, TNF-α, MHC-II, Rab3D, Col1a1 and Col3a1, and the other LG allocated and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) for histology or 4% paraformaldehyde for indirect immunofluorescence. The number of mice (n) used for each experiment are indicated in the relevant figure legends.

Reagents:

CTSS activity assay kits were obtained from Biovision (Milpitas, CA). The RNeasy plus universal mini kit was bought from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). The Reverse Transcription Kit, the Universal Master Mix, and primers for real-time PCR analysis of ctss (Mm01255859_m1), MHC-ii (Mm00439216_m1), IFN-γ (Mm00801778_m1), Col1a1 (Mm00801666_g1), RAB3D (Mm01151273_mh), TNF-α (Mm00443258_m1) and GAPDH Mm99999915_g1) were all purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). The eye irrigating solution for washing the mouse ocular surface was from Bausch + Lomb (Rochester, NY). The 2-μL microcaps micropipettes for tear collection were obtained from Drummond (Broomall, PA). Ketamine hydrochloride (VetaKet) was from Akorn (Lake Forest, IL) and Xylazine (XylaMed) was obtained from MWI animal health (Boise, ID). Carbachol, used to stimulate LGs for tear production, was from Sigma-Aldrich Corp (St. Louis, MO). The Bio-Rad Protein Assay dye reagent was from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Optimal cutting compound (OCT) was from Sakura Lifetek (Torrance, CA). Rabbit anti-CTSS polyclonal antibody was from Biovision Inc (cat # 6686–100) (Milpitas, CA). Rabbit anti-Col1a1 polyclonal antibody was from Abcam (cat# ab34710) (Cambridge, MA). Rabbit anti-Rab3D polyclonal antibody was from Proteintech (cat# 12320–1-AP) (Rosemont, IL). Rhodamine Phalloidin, ProLong® Gold Antifade mounting medium, Alexa Fluor® 488 donkey anti-rabbit and Alexa Fluor® 568 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Analysis of Lymphocytic Infiltration:

LGs from male NOD and BALB/c mice, fixed in 10% NBF, were embedded in paraffin, cut into 5 μm horizontal sections, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) according to standard procedures. Sections were imaged using a Nikon 80i microscope equipped with a digital camera (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY). Multiple low magnification images covering the entire LG section were captured and the percentage of lymphocytic infiltration in the total tissue area represented by multiple continuous stitched images was measured across three LG sections acquired at approximately ¼, ½ and ¾ depths of sectioning within each LG utilizing ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, http://imagej.nih.gov/ij) by a blinded reviewer. These values were averaged to provide a single value for lymphocytic infiltration for one mouse LG.

Stimulated Tear Collection:

Tears were collected from anesthetized male NOD and BALB/c mice at the aforementioned ages as described. The mice were kept resting on their side and the LG was exposed by making a small incision along the axis of the outer eyelid and ear. The connective tissue capsule around the LG was carefully removed and a small layer of fine cellulose (Kimwipe; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) was applied on top of the gland. The ocular surface was washed with an eye irrigating solution. The LG was then stimulated by applying 3μl of 50 μM carbachol (CCH) topically on the gland. Tear fluid was carefully collected by gently placing a 2 μl microcapillary tubes at the medial canthus for 5 min. Each gland was stimulated three times resulting in 15 min of tear collection per LG. The tears were emptied into sterile vials and analyzed immediately.

CTSS Activity Assay in Tears and LG lysates:

Lysates were prepared by placing LG from male NOD and BALB/c mice at the ages indicated into 2.0 ml tubes with 2.0 mm zirconium beads. 300 μL of CTSS lysis buffer was added to each tube, and LG were homogenized using a BeadBlaster™ 24 microtube homogenizer (Benchmark Scientific, Inc. Edison, NJ). The homogenate was then centrifuged at 6000 X g for 10 min at 4°C; the supernatant collected was analyzed immediately. 10 μL of LG lysate with 40 μL of CTSS lysis buffer and 50 μL of CTSS reaction buffer or 100 μL of mouse tears diluted in CTSS reaction buffer were added to 96-well plates in duplicates. 2 μL of CTSS inhibitor was added to one of the two wells and 2 μL of substrate was added to each well with and without the CTSS inhibitor for each sample. The reaction was then incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The quantity of the resulting fluorescent products obtained from the CTSS and substrate reaction was measured with a microplate spectrofluorometer (Spectramax Gemini EM; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale CA) using 400 nm/505 nm excitation/emission filters.

mRNA Extraction and Real Time PCR Analysis:

mRNA was extracted from LG from male NOD and BALB/c mice at the indicated ages using the RNeasy plus Universal Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. mRNA concentration was measured using the NanoDrop™ spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE). cDNA was prepared with the Reverse Transcription Kit for all the samples using equal amounts of mRNA. Real time PCR was then performed for ctss, MHC II, IFN-γ, TNF-α, Rab3D, Col1a1, and Col3a1 using GAPDH as an internal control. The recorded data was then analyzed using the ΔΔCt method. The change ratio for a specific gene was obtained by calculating ΔCt = Ct (target gene) − Ct (internal control), ΔCt (control) − ΔCt (samples) = ΔΔCt. Finally, relative quantification (RQ) was calculated using the formula 2−ΔΔCt.

Immunofluorescence labeling of LG:

LGs from male NOD and BALB/c mice at the indicated ages were retrieved following euthanasia; fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 3 h, transferred to 30% sucrose and incubated overnight at 4oC. Fixed glands were inserted into OCT compound and flash-frozen on dry ice. The blocks were cryosectioned at 5 μm thickness and mounted onto a glass slide. The sections were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min and 1% SDS for 5 min. Following this, the sections were blocked with 1% BSA for 1 h and later incubated with primary and secondary antibodies for a period of 1 h each at 37oC. Between each incubation, the slides were washed with PBS three times for 5 min each. Finally, the samples were mounted with ProLong anti-fade and imaged using a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Average Mean gray values of 3 random acini from 3 randomly selected images obtained from each of 3 mice in each age group was measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, http://imagej.nih.gov/ij) to quantify the expression level of different proteins tested.

Statistical Analysis:

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software. A one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used between all pairs of the group. A P≤0.05 was considered as a significant difference.

Results

LG lymphocytic infiltration in male NOD mice is established by 3 M of age:

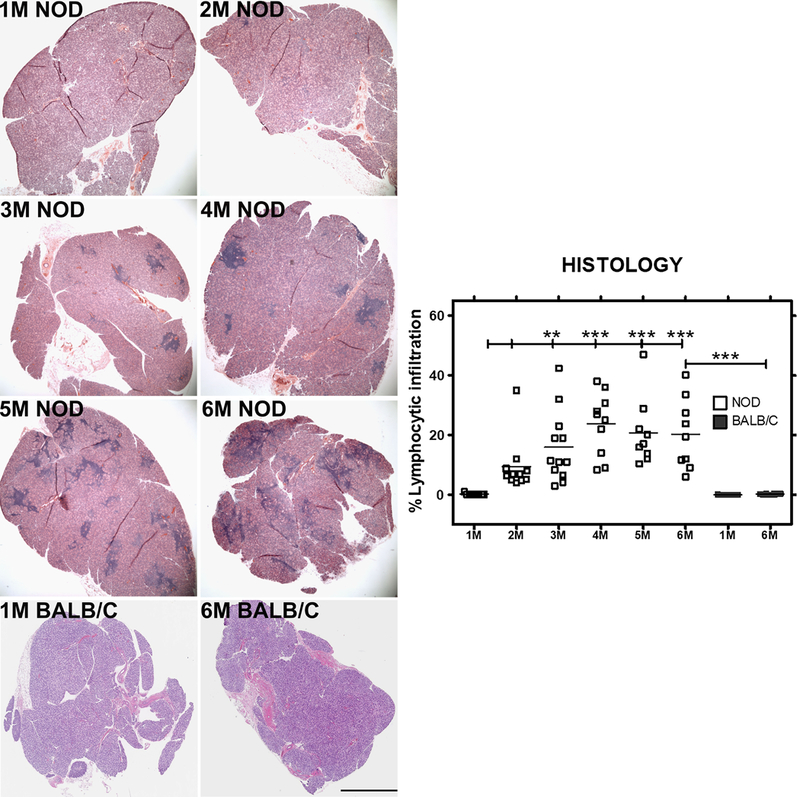

The presence of infiltrating lymphocytes in the tear- and saliva-producing exocrine glands is a principal hallmark of SS in patients. Similarly, lymphocytic infiltration characterizes the LG of male NOD mice, an experimental model of autoimmune dacryoadenitis. We quantified the extent of lymphocytic infiltration over time as an indicator of disease progression in these mice. H&E stained sections of LG were obtained from NOD mice aged 1–6 M and BALB/c control mice aged 1 M and 6 M, and the level of lymphocytic infiltration (dark purple patches) was quantified as a percentage of the total area of the gland. As shown in Fig 1, there were no signs of infiltration in LG at 1M in NOD mice and in LG at 1 M and 6 M BALB/c mice; however, initial lymphocytic infiltrates were observed in the LG (dark purple) at 2 M, increasing to 20–40% by 3 M (P<0.01), and remaining at that general level up to 6 M in male NOD mice, suggesting disease is well established and lymphocytic infiltration is maximal and significant by 3 M.

Fig 1: Representative images and quantitative assessment of lymphocytic infiltration in LG of male NOD and BALB/c mice.

1 to 6 M old male NOD mice and 1 and 6M old male BALB/c (n=9–12 mice per group) LGs were sectioned and stained with H&E. Images show foci of infiltrating lymphocytes (dark purple patches) within tissue, representing a measure of disease progression over time. Bar, 300 μm. Image J was used to quantify the percentage of lymphocytic infiltration. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to for statistical comparison. The overall ANOVA p-value was < 0.0001. * indicates post-test P-values for each of the NOD age groups (2 M, 3 M, 4 M, 5 M, 6 M) compared to NOD at 1 M, and also 6 M NOD compared to 6 M BALB/c. * P<0.05; **, P< 0.01; and *** P < 0.001.

Gene expression analysis in male NOD mice LG shows early elevations in pro-inflammatory cytokines by 2 M of age:

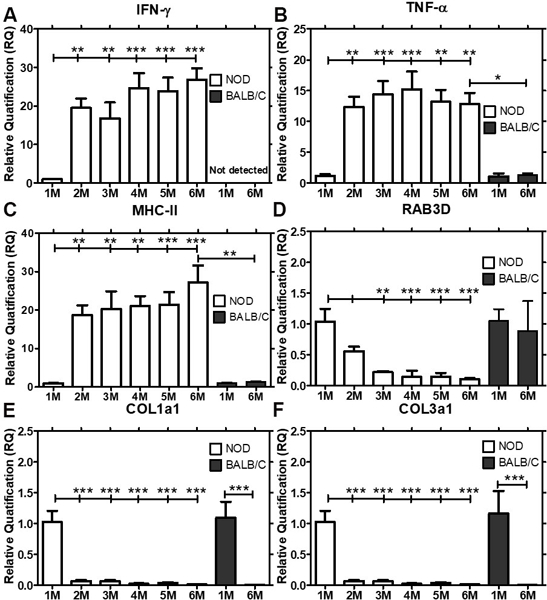

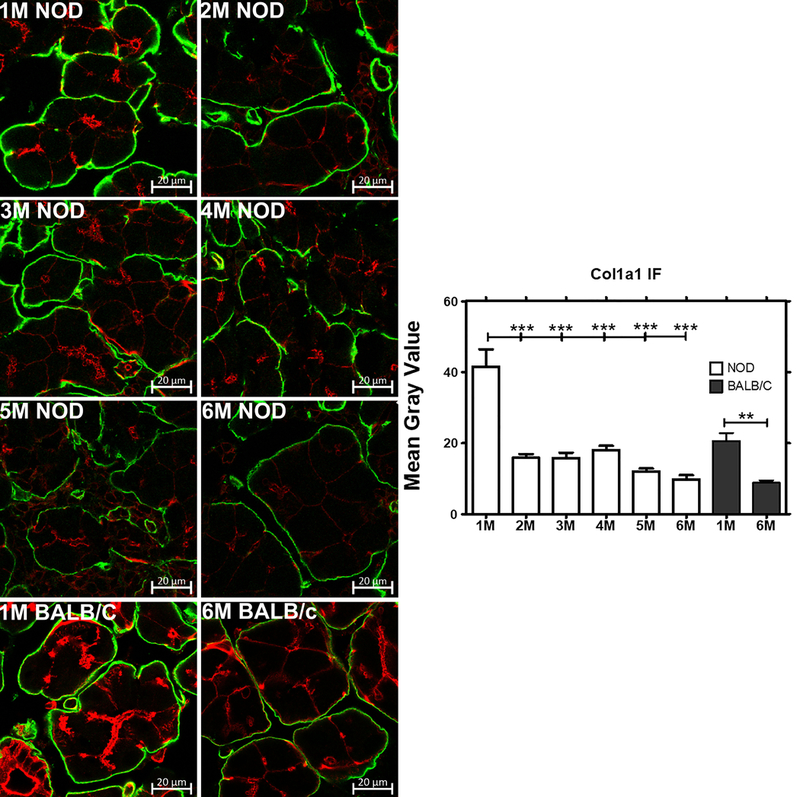

Gene expression of several genes commonly associated with the etiology and autoimmune exocrinopathy in SS were analysed to understand how their expression changed with lymphocytic infiltration and disease progression over time. Quantitative real time-PCR revealed significant up-regulation of IFN- ɣ (Fig 2A) and TNF-α (Fig 2B), cytokines commonly associated with inflammation in SS patients [34–36], as well as upregulation of MHC II, which is associated with increased antigen presentation [37–39] (Fig 2C), by 2 M (P<0.01) in male NOD LG when compared to 1 M old male NOD mice. Expression of these genes each increased remarkably between 1– 2 M, prior to major lymphocytic infiltration of the LG, and then remained elevated at all time points measured up to 6 M, suggesting a possible causative or initiating role in lymphocytic infiltration. However, the expression levels of these genes in 6 M male BALB/c mice did not change when compared to 1 M BALB/c mice. A progressive and significant down-regulation in the gene expression of the major secretory Rab protein associated with formation and maintenance of mature secretory vesicles in acinar cells of the LG, Rab3D, which is also decreased in exocrine glands of SS patients [40] was conversely detected in parallel in LG of NOD mice by 2 M which continued at 3 M and was sustained to 6 M (Fig 2D), while no change in its expression level were observed in 6 M BALB/c LGs when compared to 1 M BALB/c mice LG. A more precipitous decline in gene expression of the major ECM proteins, collagen type 1 (col1a1) (Fig 2E) and collagen type 3a1 (Fig 2F), also decreased in SS LG and SG [31, 41], was seen by 2 M and sustained to 6 M (P<0.001) in NOD LGs and also seen in 6 M (P<0.001) BALB/c LGs when compared to 1 M LGs from each strain, respectively. As shown in Fig 3, by 2 M and continuing to 6 M, collagen 1 immunofluorescence was markedly reduced in the NOD mouse LG when compared to the amount in 1 M mouse LG, and but also was diminished with age in BALB/c mouse LG at 6 M.

Fig 2: Expression levels of IFN- γ, MHC-II, TNF-α, RAB3D, COL1a1 and COL3a1 in male NOD and BALB/c mouse LG from 1 M through 6 M of age determined by qPCR.

Gene expression of IFN-γ, MHC-II, TNF-α, RAB3D, COL1a1 and COL3a1 were quantified in male NOD mice at 1 M of age, prior to initiation of inflammation of the LG, through 6 M of age (n=7–9 mice per group), when autoimmune dacryoadenitis is established and in BALB/c mice at 1 M and 6 M of age (n=4 mice per group). Data represents Mean ± SEM of relative quantification, which was measured using the formula 2-ΔΔCt. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical comparison. The overall ANOVA p-values for each of IFN- γ, MHC-II, TNF-α, RAB3D, COL1a1 and COL3a1 was < 0.0001. * indicates post-test p-values for each of the NOD age groups (2 M, 3 M, 4 M, 5 M, 6 M) compared to NOD 1 M, and 6 M NOD compared to 6 M BALB/c. * P<0.05; **, P< 0.01; and *** P < 0.001.

Fig 3: Collagen type 1 expression and quantitative analysis in male NOD and BALB/c mice LG visualized by indirect immunofluorescence.

The intensity of Collagen 1 immunofluorescence was clearly decreased from 1–6 M in parallel with the decreased col1a1 gene expression seen in NOD and BALB/c mice LG (n=3 mice per group). Green, collagen 1 visualized with a Rabbit anti-Col1a1 polyclonal antibody and an Alexa Fluor® 488-donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody; red, actin labeled with rhodamine-phalloidin. Bar, 20 μm. Image J was used to quantify the expression level of Col1a1. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical comparison. The overall ANOVA p-value was < 0.0001. * indicates post-test p-values for each of the NOD age groups (2 M, 3 M, 4 M, 5 M, 6 M) compared to NOD 1 M, and 6 M BALB/c compared to 1M BALB/c. * P<0.05; **P< 0.01; and *** P < 0.001.

ctss gene expression in LG and Activity in LG Lysates and Tears is increased in parallel to disease development:

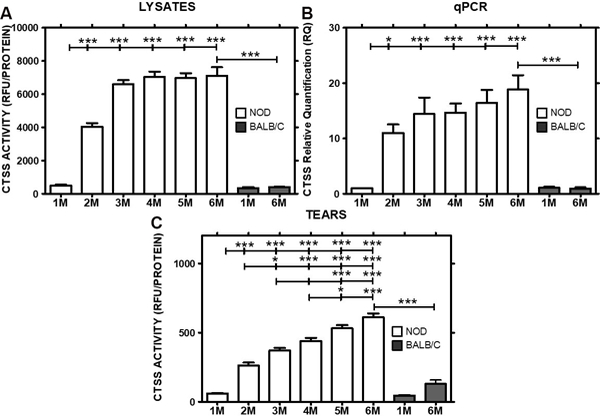

Cathepsin S (CTSS) was previously observed to be increased in tears of male NOD mice with significant lymphocytic infiltration of the LG [30] by 3 M of age and is also elevated in diagnosed SS patients [32, 33]. CTSS activity was measured in LG lysates or in carbachol-stimulated tears collected from male NOD mice aged 1 to 6 M. A significant increase in CTSS activity in LG lysates was seen as early as 2 M (8.1-fold increase, P<0.0001), which peaked at 14-fold increase at 3 M (P<0.0001) and remained elevated at this level when compared to levels in 1 M mice (Fig 4A). Gene expression changes in ctss in LG paralleled the elevated enzyme activity in LG lysates (Fig 4B). In tears, mean CTSS activity was significantly elevated in mice aged 2 to 6 M when compared to 1 M old mice, where little to no lymphocytic infiltration was observed as shown in Fig 1. However, in contrast to the CTSS activity in LG lysates, the age-dependent increase in tear CTSS continued throughout the time measured. The activity increased by 4.4-fold at 2 M (P<0.001), 6.2-fold at 3 M (P<0.001), 7.3-fold at 4 M (P<0.0001), 8.8-fold at 5 M old mice (P<0.0001), and 10.1 in 6 M old mice (P<0.001) (Fig 4C) relative to 1 M old mice. However neither LG and tear CTSS activity nor ctss gene expression were significantly changed in 6 M BALB/c mice when compared to 1 M mice. Moreover both LG and tear activity and gene expression levels of ctss in 6 M NOD mice were significantly elevated when compared to 6 M BALB/c mice as shown in Fig 4A-C. Values shown in Fig 4A and4C are normalized to 50 μg of total LG protein concentration and normalized to 100 μg tear protein, respectively; tear CTSS activity is significantly less than that seen in CTSS lysates. However, the gradual increase in its activity over time in these mice relative to the constant elevation in lysates suggests an active change in its cellular sorting into the tear fluid.

Fig 4: CTSS activity in tear fluid and CTSS expression and activity in LG lysates in 1 to 6 M old male NOD and BALB/c mice.

A) CTSS activity in LG lysates of NOD mice increased with time from 1–3 M and then remained elevated, whereas no significant difference in activity was observed in 6 M BALB/compared to 1 M BALB/c mice (n=6–10 mice per group). B) Relative CTSS expression levels were increased in NOD mouse LG from 2 M to 6 M when compared to 1 M old mice, while no change was observed in BALB/c mice (n=5–9 mice per group). C) CTSS activity was progressively increased in tears of NOD mice aged 1 to 6 M, but was not significantly different in 1 M and 6 M BALB/c mice (n=6–10 mice per group). Data represents Mean± SEM. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to calculate the significance and the overall ANOVA p-value for each of LG lysate CTSS activity, tear CTSS activity and CTSS qPCR analysis was < 0.0001. * indicates post-test p-values for each of the NOD age groups (2 M, 3 M, 4 M, 5 M, 6 M) compared to NOD 1 M, and 6 M NOD compared to 6 M BALB/c. * P<0.05; **P< 0.01; and *** P < 0.001.

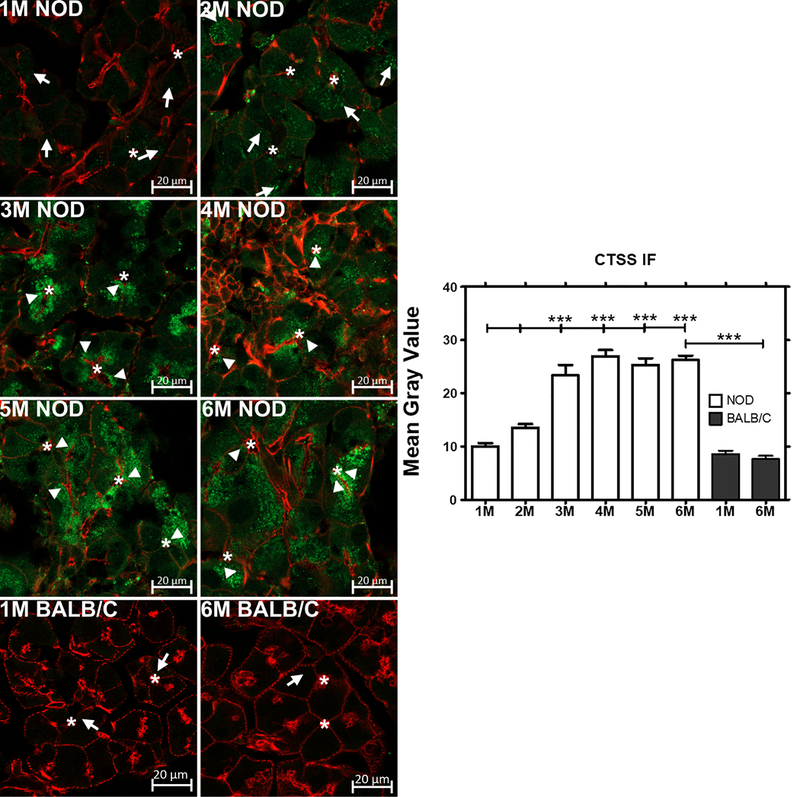

CTSS Activity in tears parallels changes in CTSS and Rab3D distribution within the secretory pathway in acinar cells:

To understand how the intracellular distribution of CTSS is affected with progression of autoimmune dacryoadenitis, indirect immunofluorescence was performed on sections of LG from male NOD mice aged 1–6 M. Representative images are shown in Fig 5. At 1 M of age, CTSS immunofluorescence was barely detectable in LG acinar cells, occasionally detected in large basolateral organelles with morphology and distribution consistent with lysosomes. This distribution is consistent with the known role of CTSS in all cells in lysosomal protein catabolism [30, 42]. By 2 M of age, CTSS immunofluorescence was detected more abundantly throughout the cytoplasm in large basolateral vesicles, again consistent with lysosomes. However, by 3 M of age, a significant increase in CTSS-enriched organelles was also detected immediately beneath the apical plasma membranes, suggestive of the enrichment of CTSS in vesicles destined for secretion at the apical membrane and into tears. CTSS immunofluorescence in subapical organelles appeared to increase from 4–5 M and to remain constant at 6 M. These data suggest that CTSS present in increasing abundance in acinar cells of the LG is increasingly recovered in vesicles that discharge their contents by regulated secretion, consistent with its increased activity in tears throughout this period. No detectable CTSS immunofluorescence in BALB/c mice was seen at 6 M relative to 1 M in LG acinar cells as also shown in Fig 5.

Fig 5: Expression and quantification of CTSS immunofluorescence in male NOD and BALB/c mouse LG from 1 M thorough 6 M.

CTSS showed increased immunofluorescence consistent with its increased gene expression. In addition, its distribution shifted from enrichment in apparent basolateral lysosomes (arrows) to apparent secretory vesicles located beneath the apical plasma membrane (arrowheads). CTSS immunofluorescence was not abundant in both 1 and 6 M old male BALB/c mice LG (n=3 mice per group). *, luminal regions and Bars, 20 μm. Green, CTSS immunofluorescence obtained with a rabbit anti-CTSS polyclonal antibody and Alexa Fluor® 488-donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Red, actin filaments labeled with rhodamine-phalloidin. Image J was used to quantify the expression of CTSS in NOD and BALB/c mice acini. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical comparison. The overall ANOVA p-value was < 0.0001. * indicates post-test p-values for each of the NOD age groups (2 M, 3 M, 4 M, 5 M, 6 M) compared to NOD 1 M, and 6 M NOD compared to 6 M BALB/c. * P<0.05; **P< 0.01; and *** P < 0.001.

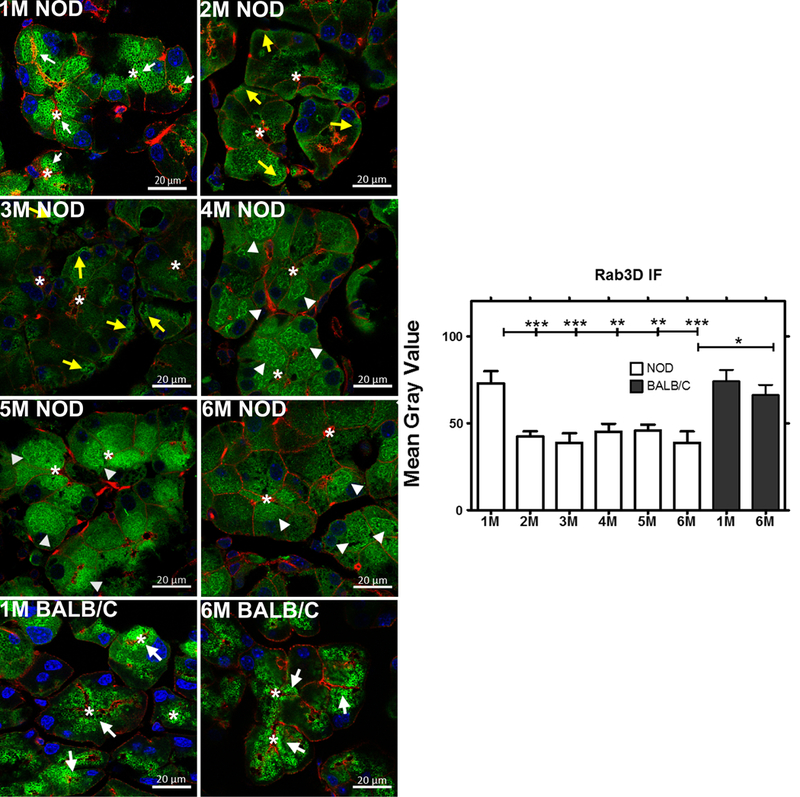

We have previously shown that secretion of CTSS is increased in mice lacking Rab3D [40]. As shown in Fig 6, male NOD mice exhibit a dramatic reduction and redistribution of Rab3D positive vesicles suggestive of reduced function of Rab3D in the regulated secretory pathway with aging. At 1 M of age, male NOD mice showed robust Rab3D immunofluorescence associated with apparent mature secretory vesicles located from the apical region and extended abundantly into the cytoplasm. By 2 M of age, reduced immunofluorescence was noticeable and by 3 M of age, the immunofluorescence signal was further reduced while labeling at the basolateral membrane could be detected. Additionally, in LG from mice aged 4 and 5 M, Rab3D immunofluorescence was detected in apparent bands around aggregates of large vesicles in the middle region of the cell. By 6 M of age, Rab3D immunofluorescence was almost undetectable. These images suggest profound changes in the function of this major effector of regulated secretion during disease progression, likely related to the altered secretory profile of CTSS. Meanwhile the immunofluorescence associated with Rab3D in LG acinar cells in 6 M BALB/c mice was unchanged in intensity and distribution relative to 1 M BALB/c mice (Fig 6).

Fig 6: Expression, distribution and quantification of Rab3D immunofluorescence in male NOD and BALB/c mouse LG from 1 M thorough 6 M of age.

Rab3D showed decreased immunofluorescence with time, consistent with its decreased gene expression in NOD mouse LG, while the immunofluorescence labeling associated with Rab3D in 1 M and 6 M BALB/c mice was unchanged (n=3 mice per group). The distribution pattern in young NOD and in both 1 M and 6 M BALB/c mouse LG acini showed enrichment at the apical region in large vesicles which in some cases extended all the way into the cell interior. In older NOD mice, Rab3D distribution shifted from enrichment in large subapical mature secretory vesicles (white arrows) to more dispersed aggregates beneath the basolateral membrane (yellow arrows) and to apparent bundles around vesicle aggregates (arrowheads). *, luminal regions and bars, 20 μm. Green, Rab3D immunofluorescence obtained with a rabbit anti-Rab3D polyclonal antibody and Alexa Fluor® 488-donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Red, actin filaments labeled with rhodamine-phalloidin; Blue, DAPI. Image J was used to quantify the expression of Rab3D expression in NOD and BALB/c mice acini. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical comparison. The overall ANOVA p-value was < 0.0001. * indicates post-test p-values for each of the NOD age groups (2 M, 3 M, 4 M, 5 M, 6 M) compared to NOD 1 M, and 6 M NOD compared to 6 M BALB/c. * P<0.05; **P< 0.01; and *** P < 0.001.

Discussion

While SS affects up to 4 million Americans, the lack of specific diagnostic markers means that patients are not diagnosed until later stages of the disease when irreversible damage to the exocrine glands may have occurred. The current classification criteria are based on a weighted sum of five items: a positive Anti-SSA (Ro) antibody; demonstration of focal lymphocytic sialadenitis (FLS) with a focus score of ≥ 1 foci/ 4 mm2; an ocular staining score (OSS) of ≥5; a Schirmer’s test of ≤ 5 mm/5 min; and an unstimulated whole saliva flow rate ≤ 0.1 mL/min [14]. While this set of criteria is endorsed by the ACR and EULAR, these tests/criteria have major limitations including the lack of specificity of SSA antibodies and the invasive nature and potential side effects of lip biopsies for FLS assessment. Moreover, a lip biopsy may not reflect the extent of autoimmune dacryoadenitis, since exocrinopathy may not equivalently impact the LG and SG. Dry eye and dry mouth can be symptoms of other diseases and/or result from low humidity levels, use of computers or tablets for prolonged periods, exposure to smoke [43], Due to many of these limitations, diagnosis of SS remains challenging.

The main objective of the present study was to evaluate the time course of development of elevated activity of a putative SS biomarker, tear CTSS, identified utilizing the male NOD mouse model [30] and validated in an SS patient population [32, 33], relative to other indicators of disease. Our findings show that significant elevations of CTSS occur in LG lysates and are detectable in tears as early as 2 M of age in the male NOD mice, in parallel with early elevations in the pro-inflammatory cytokines, IFN-γ and TNF-α, and of MHC II in the LG. IFN-γ and TNF-α are implicated in disease pathogenesis, as a majority of T-cells isolated from infiltrates in LG of male NOD mice produce IFN-γ and TNF-α upon ex vivo antigen stimulation, which is consistent with their elevation in the early stages of disease [44]. The timeline of LG disease development, observed in our cohort is consistent with what have been shown in other NOD mice cohorts, with early elevation of LG gene expression of TNF-α and IFN-γ at 6–8 weeks along with lymphocytic infiltration around 2 months of age [45–47]. Although not measured here, we have previously shown in diseased NOD mice that changes in pro-inflammatory gene expression of these cytokines are correlated with their increased protein expression, utilizing multiplex ELISA [48]. Elevated tear CTSS occurs concomitant with the earliest detectable lymphocytic infiltration of the LG and before lymphocytic infiltration reaches maximum levels. The continued increase in tear CTSS with aging in the mice may reflect the continued deterioration of the Rab3D-mediated secretory pathway, which has been linked to negative regulation of CTSS secretion [40] from lacrimal acini, and has also been shown to be down-regulated in SS patient exocrine glands [49, 50].

CTSS is an endopeptidase that belongs to the C1 (papain) family, and is abundant in late endosomes and lysosomes, with a role in protein catabolism [51, 52]. It is also responsible for immune responses through participation in MHC II-mediated antigen presentation in professional antigen-presenting cells [53, 54]. Consistent with this function, it is well-established that ctss expression is responsive in particular to IFN-γ, which also evokes expression of other components of MHC II-mediated antigen presentation through the transcription factor (class II transactivator) CIITA including the class II α and β chains, invariant chain and the DMA and DMB-chains [48, 55]. Thus, CTSS may serve as an early and sensitive readout reflective of onset of autoimmune-mediated exocrine gland autoimmune inflammation.

Tear CTSS activity in SS patients has thus far been shown to be significantly elevated only in patients with diagnosed disease [32, 33]. These new data, extrapolated to SS patients, suggest that CTSS may be elevated in LG and tears early in disease development at first onset of tissue cytokine elevation and onset of LG lymphocytic infiltration. This would suggest significant value in the testing of CTSS as an early stage diagnostic biomarker of SS, in parallel with “gold standard” biomarkers in SS patients since it might represent an earlier disease stage than any of the classification criteria in current use. Tear CTSS measures are non-invasive, in contrast to measures such as FLS, and they are capable of discriminating between patients with SS and patients with non-autoimmune mediated dry eye [32, 33].

It should be noted that the ability of CTSS to contribute to antigen presentation and processing, and to be stable at neutral pH when compared to other cysteine proteases [52], allows it to play a key role in inflammation. Its role in MHC II-mediated antigen presentation involves degradation of proteins to antigenic peptides [56, 57], maturation and trafficking of MHC II αβ heterodimer with invariant chain (Ii) and sequential degradation of Ii to class II associated invariant chain peptide (CLIP) that facilitates Antigen loading and presentation [58–60]. Moreover, CTSS has the potential to participate in extracellular events within tissue and on the ocular surface. CTSS is implicated in extracellular matrix remodeling and degradation [61, 62], which in turn leads to cell infiltration, migration and differentiation [63, 64]. Various ECM proteins are the substrates of CTSS [65, 66]. In the current study, we examined two types of collagen, col1a1 and col3a1, which are known to be degraded in the exocrine glands of SS patients [41]. Although we did observe loss of collagen 1 immunofluorescence, we were surprised to detect early changes in gene expression of these proteins by 2 M of age, with their expression remaining decreased through 6 M. We also observed the loss of col1a1 and col3a1 by gene expression and collagen 1 by immunofluorescence in 6 M BALB/c mice when compared to 1 M BALB/c mice. While elevated tissue CTSS can potentially contribute to reduced tissue collagen 1, the findings of reduced gene expression and loss of col1agen 1 shown by immunofluorescence in BALB/c are unexpected and suggest additional potential contributions beyond CTSS-mediated degradation, potentially related to aging.

The ability of CTSS to participate in multiple events in inflammation suggest that it may play an active role in disease progression, a subject of active investigation by many groups. Studies utilizing CTSS inhibitors in NFS/sld, another mouse model of SS, have shown suppression of autoimmune sialadenitis [67]. Several CTSS inhibitors are in clinical trials for treatment of autoimmune diseases and other disorders including celiac disease [68], abdominal aortic aneurysm [69], RA (www.clinicaltrails.gov, Identifier: NCT00425321), psoriasis (www.clinicaltrails.gov, Identifier: NCT00396422) and most recently, a phase II study to assess the efficacy of a small molecule CTSS inhibitor in pSS (www.clinicaltrails.gov, Identifier: NCT02701985). If CTSS represents a therapeutic target as well as a biomarker of disease, the relationship of its levels in tears with response to therapy will be important to determine. It is important to note that we have treated autoimmune dacryoadenitis in male NOD mice with rapamycin formulations administered both intravenously and topically and, in both cases, reduction of lymphocytic infiltration of the LG was accompanied by a parallel reduction in tear CTSS levels, suggesting this as a potentially pharmacodynamic biomarker [70, 71].

Conclusion

Tear and tissue CTSS levels were evaluated in the male NOD mice in parallel with other indicators of autoimmune dacryoadenitis, in order to understand how these indicators may emerge during the disease process and relate to other available biomarkers for disease diagnosis. Autoimmune dacryoadenitis in the male NOD mouse shares many attributes with SS patients. We find that tear CTSS is elevated early at the first detectable lymphocytic infiltration of the LG, in parallel with the first spikes in pro-inflammatory cytokines and MHC II gene expression. The absence of significantly elevated tear CTSS in the non-diseased BALB/c control mouse model further suggests that this elevation is disease-specific and may serve as a potential tool to identify patients with early stage SS.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Significance:

The diagnosis of SS is often delayed due to overlapping symptoms with other autoimmune diseases and lack of specific biomarkers [43, 72, 73]. We have previously shown that CTSS activity is elevated in tears of female SS patients compared to patients with other autoimmune diseases including RA, SLE or other eye conditions including non-autoimmune associated dry eye and Blepharitis and healthy controls [32, 33], thus constituting a promising biomarker for SS. This study furthers the understanding of the utility of tear CTSS activity as a biomarker of SS, as it shows its increase early in disease development.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants EY011386 and EY026635 to SHA and in part by an unrestricted grant to the USC Department of Ophthalmology from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY. The authors would like to thank the Translational Research Laboratory in the USC School of Pharmacy for supporting this work. The Cell and Tissue Imaging Core of the USC Research Center for Liver Diseases provided histology services (NIH P30 DK048522).

Abbreviations:

- ACR

American College of Rheumatology

- CCH

carbachol

- CTSS

Cathepsin S

- ECM

Extra cellular matrix

- EULAR

European League Against Rheumatism

- FLS

focal lymphocytic sialadenitis

- LG

Lacrimal Gland

- MHC

Major Histocompatibility complex

- NOD

Non-Obese Diabetic

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- SS

Sjögren’s Syndrome

- SG

Salivary Gland

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- SICCA

Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance

Footnotes

Disclosure of Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Fox RI and Kang HI, Pathogenesis of Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheum Dis Clin North Am, 1992. 18(3): p. 517–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramos-Casals M, et al. , Primary Sjogren syndrome. Bmj, 2012. 344: p. e3821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voulgarelis M, Tzioufas AG, and Moutsopoulos HM, Mortality in Sjogren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol, 2008. 26(5 Suppl 51): p. S66–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tzioufas AG and Voulgarelis M, Update on Sjogren’s syndrome autoimmune epithelitis: from classification to increased neoplasias. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol, 2007. 21(6): p. 989–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambrosetti A, et al. , Most cases of primary salivary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma are associated either with Sjoegren syndrome or hepatitis C virus infection. British Journal of Haematology, 2004. 126(1): p. 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kassan SS, et al. , Increased risk of lymphoma in sicca syndrome. Ann Intern Med, 1978. 89(6): p. 888–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel R and Shahane A, The epidemiology of Sjogren’s syndrome. Clin Epidemiol, 2014. 6: p. 247–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peri Y, et al. , Sjogren’s syndrome, the old and the new. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol, 2012. 26(1): p. 105–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramos-Casals M, et al. , Google-driven search for big data in autoimmune geoepidemiology: analysis of 394,827 patients with systemic autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev, 2015. 14(8): p. 670–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathews PM, et al. , Ocular complications of primary Sjogren syndrome in men. Am J Ophthalmol, 2015. 160(3): p. 447–452.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mavragani CP and Moutsopoulos HM, The geoepidemiology of Sjogren’s syndrome. Autoimmun Rev, 2010. 9(5): p. A305–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vitali C, et al. , Classification criteria for Sjogren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis, 2002. 61(6): p. 554–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiboski SC, et al. , American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Data-Driven, Expert Consensus Approach in the SICCA Cohort. Arthritis care & research, 2012. 64(4): p. 475–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiboski CH, et al. , 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Classification Criteria for Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Consensus and Data-Driven Methodology Involving Three International Patient Cohorts. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 2017. 69(1): p. 35–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esch TR, et al. , A Novel Lacrimal Gland Autoantigen in the NOD Mouse Model of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology, 2002. 55(3): p. 304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunger RE, et al. , Inhibition of submandibular and lacrimal gland infiltration in nonobese diabetic mice by transgenic expression of soluble TNF-receptor p55. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 1996. 98(4): p. 954–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu Y, et al. , Functional changes in salivary glands of autoimmune disease-prone NOD mice. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism, 1992. 263(4): p. E607–E614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavoie TN, Lee BH, and Nguyen CQ, Current Concepts: Mouse Models of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology, 2011. 2011: p. 549107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brayer J, et al. , Alleles from chromosomes 1 and 3 of NOD mice combine to influence Sjogren’s syndrome-like autoimmune exocrinopathy. J Rheumatol, 2000. 27(8): p. 1896–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delaleu N, et al. , Biomarker profiles in serum and saliva of experimental Sjögren’s syndrome: associations with specific autoimmune manifestations. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 2008. 10(1): p. R22–R22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toda I, et al. , Impact of Gender on Exocrine Gland Inflammation in Mouse Models of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Experimental Eye Research, 1999. 69(4): p. 355–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunger RE, et al. , Male gonadal environment paradoxically promotes dacryoadenitis in nonobese diabetic mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 1998. 101(6): p. 1300–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winer S, et al. , Primary Sjögren’s syndrome and deficiency of ICA69. The Lancet, 2002. 360(9339): p. 1063–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doyle ME, et al. , Autoimmune dacryoadenitis of NOD/LtJ mice and its subsequent effects on tear protein composition. Am J Pathol, 2007. 171(4): p. 1224–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roescher N, Tak PP, and Illei GG, Cytokines in Sjogren’s syndrome. Oral Dis, 2009. 15(8): p. 519–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park YS, Gauna AE, and Cha S, Mouse Models of Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome. Curr Pharm Des, 2015. 21(18): p. 2350–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brayer JB, et al. , IL-4-dependent effector phase in autoimmune exocrinopathy as defined by the NOD.IL-4-gene knockout mouse model of Sjogren’s syndrome. Scand J Immunol, 2001. 54(1–2): p. 133–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cha S, et al. , A dual role for interferon-gamma in the pathogenesis of Sjogren’s syndrome-like autoimmune exocrinopathy in the nonobese diabetic mouse. Scand J Immunol, 2004. 60(6): p. 552–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson CP, et al. , Transfer of human serum IgG to nonobese diabetic Igmu null mice reveals a role for autoantibodies in the loss of secretory function of exocrine tissues in Sjogren’s syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1998. 95(13): p. 7538–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X, et al. , Increased expression of cathepsins and obesity-induced proinflammatory cytokines in lacrimal glands of male NOD mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2010. 51(10): p. 5019–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schenke-Layland K, et al. , Increased degradation of extracellular matrix structures of lacrimal glands implicated in the pathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology, 2008. 27(1): p. 53–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamm-Alvarez SF, et al. , Tear cathepsin S as a candidate biomarker for Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2014. 66(7): p. 1872–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edman MC, et al. , Increased Cathepsin S activity associated with decreased protease inhibitory capacity contributes to altered tear proteins in Sjögren’s Syndrome patients. Scientific Reports, 2018. 8(1): p. 11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fox RI, et al. , Cytokine mRNA expression in salivary gland biopsies of Sjögren's syndrome. The Journal of Immunology , 1994. 152(11): p. 5532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willeke P, et al. , Interleukin 1ß and tumour necrosis factor α secreting cells are increased in the peripheral blood of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 2003. 62(4): p. 359–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Woerkom JM, et al. , Salivary gland and peripheral blood T helper 1 and 2 cell activity in Sjögren’s syndrome compared with non-Sjögren’s sicca syndrome. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 2005. 64(10): p. 1474–1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arakaki R, et al. , Role of plasmacytoid dendritic cells for aberrant class II expression in exocrine glands from estrogen-deficient mice of healthy background. Am J Pathol, 2009. 174(5): p. 1715–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Low HZ and Witte T, Aspects of innate immunity in Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther, 2011. 13(3): p. 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moutsopoulos HM, et al. , HLA-DR expression by labial minor salivary gland tissues in Sjogren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis, 1986. 45(8): p. 677–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meng Z, et al. , Imbalanced Rab3D versus Rab27 increases cathepsin S secretion from lacrimal acini in a mouse model of Sjogren’s Syndrome. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 2016. 310(11): p. C942–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goicovich E, et al. , Enhanced degradation of proteins of the basal lamina and stroma by matrix metalloproteinases from the salivary glands of Sjögren’s syndrome patients: Correlation with reduced structural integrity of acini and ducts. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 2003. 48(9): p. 2573–2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brix K, et al. , Cysteine cathepsins: Cellular roadmap to different functions. Biochimie, 2008. 90(2): p. 194–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kassan SS and Moutsopoulos HM, CLinical manifestations and early diagnosis of sjögren syndrome. Archives of Internal Medicine, 2004. 164(12): p. 1275–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barr JY, et al. , CD8 T cells contribute to lacrimal gland pathology in the nonobese diabetic mouse model of Sjogren syndrome. Immunol Cell Biol, 2017. 95(8): p. 684–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robinson CP, et al. , Characterization of the changing lymphocyte populations and cytokine expression in the exocrine tissues of autoimmune NOD mice. Autoimmunity, 1998. 27(1): p. 29–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takahashi M, et al. , High incidence of autoimmune dacryoadenitis in male non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice depending on sex steroid. Clin Exp Immunol, 1997. 109(3): p. 555–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tornwall J, et al. , T cell attractant chemokine expression initiates lacrimal gland destruction in nonobese diabetic mice. Lab Invest, 1999. 79(12): p. 1719–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meng Z, et al. , Interferon-γ treatment in vitro elicits some of the changes in cathepsin S and antigen presentation characteristic of lacrimal glands and corneas from the NOD mouse model of Sjögren’s Syndrome. PLOS ONE, 2017. 12(9): p. e0184781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bahamondes V, et al. , Changes in Rab3D expression and distribution in the acini of Sjögren’s syndrome patients are associated with loss of cell polarity and secretory dysfunction. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 2011. 63(10): p. 3126–3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kamoi M, et al. , Accumulation of secretory vesicles in the lacrimal gland epithelia is related to non-Sjogren’s type dry eye in visual display terminal users. PLoS One, 2012. 7(9): p. e43688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Claus V, et al. , Lysosomal enzyme trafficking between phagosomes, endosomes, and lysosomes in J774 macrophages. Enrichment of cathepsin H in early endosomes. J Biol Chem, 1998. 273(16): p. 9842–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bromme D, et al. , Functional expression of human cathepsin S in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Purification and characterization of the recombinant enzyme. J Biol Chem, 1993. 268(7): p. 4832–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shi GP, et al. , Molecular cloning and expression of human alveolar macrophage cathepsin S, an elastinolytic cysteine protease. J Biol Chem, 1992. 267(11): p. 7258–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shi GP, et al. , Cathepsin S required for normal MHC class II peptide loading and germinal center development. Immunity, 1999. 10(2): p. 197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang CH and Flavell RA, Class II transactivator regulates the expression of multiple genes involved in antigen presentation. J Exp Med, 1995. 181(2): p. 765–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hsieh C-S, et al. , A Role for Cathepsin L and Cathepsin S in Peptide Generation for MHC Class II Presentation. The Journal of Immunology, 2002. 168(6): p. 2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Plüger Esther BE, et al. , Specific role for cathepsin S in the generation of antigenic peptides in vivo. European Journal of Immunology, 2002. 32(2): p. 467–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beers C, et al. , Cathepsin S controls MHC class II-mediated antigen presentation by epithelial cells in vivo. J Immunol, 2005. 174(3): p. 1205–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lotteau V, et al. , Intracellular transport of class II MHC molecules directed by invariant chain. Nature, 1990. 348(6302): p. 600–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Riese RJ, et al. , Essential role for cathepsin S in MHC class II-associated invariant chain processing and peptide loading. Immunity, 1996. 4(4): p. 357–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fonović M and Turk B, Cysteine cathepsins and extracellular matrix degradation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects, 2014. 1840(8): p. 2560–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reddy VY, Zhang QY, and Weiss SJ, Pericellular mobilization of the tissue-destructive cysteine proteinases, cathepsins B, L, and S, by human monocyte-derived macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1995. 92(9): p. 3849–3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patel VN, Rebustini IT, and Hoffman MP, Salivary gland branching morphogenesis. Differentiation, 2006. 74(7): p. 349–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thompson HA and Spooner BS, Proteoglycan and glycosaminoglycan synthesis in embryonic mouse salivary glands: effects of beta-D-xyloside, an inhibitor of branching morphogenesis. J Cell Biol, 1983. 96(5): p. 1443–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maciewicz RA, et al. , Collagenolytic Cathepsins of Rabbit Spleen: A Kinetic Analysis of Collagen Degradation and Inhibition by Chicken Cystatin. Collagen and Related Research, 1987. 7(4): p. 295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Olga V, et al. , Emerging Roles of Cysteine Cathepsins in Disease and their Potential as Drug Targets. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 2007. 13(4): p. 387–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saegusa K, et al. , Cathepsin S inhibitor prevents autoantigen presentation and autoimmunity. J Clin Invest, 2002. 110(3): p. 361–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kurada S, Yadav A, and Leffler DA, Current and novel therapeutic strategies in celiac disease. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology, 2016. 9(9): p. 1211–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jadhav PK, et al. , Discovery of Cathepsin S Inhibitor LY3000328 for the Treatment of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 2014. 5(10): p. 1138–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shah M, et al. , A rapamycin-binding protein polymer nanoparticle shows potent therapeutic activity in suppressing autoimmune dacryoadenitis in a mouse model of Sjögren’s syndrome. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society, 2013. 171(3): p. 269–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shah M, et al. , Rapamycin Eye Drops Suppress Lacrimal Gland Inflammation In a Murine Model of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 2017. 58(1): p. 372–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Akpek EK, et al. , Evaluation of patients with dry eye for presence of underlying Sjogren syndrome. Cornea, 2009. 28(5): p. 493–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, and Font J, The overlap of Sjogren’s syndrome with other systemic autoimmune diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum, 2007. 36(4): p. 246–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.