Abstract

Cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC is a therapeutic option that benefits only selected patients with peritoneal metastases (PM). New treatments like pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) have been developed to overcome some limitations of intraperitoneal chemotherapy and treat patients who are not eligible for a curative approach. The safety and feasibility of the procedure in the first few Indian patients treated with PIPAC, and the technique and the set-up required for PIPAC are described here. From May 2017 to August 2017, data was collected prospectively for all patients undergoing PIPAC at three Indian centers. The patients’ characteristic, operative findings, and perioperative outcomes were recorded. Seventeen procedures were performed in 16 patients with peritoneal metastases from various primary sites using standard drug regimens developed for the procedure. The median hospital stay was 1 day, minor and major complications were seen in two patients each (11.7%), and there was one post-operative death. Of the six patients who completed at least 6 weeks of follow-up, there was disease progression in two, unrelated problems in two patients, and a second procedure was performed in one patient. One patient underwent subsequent CRS and HIPEC. Our results show the feasibility and safety of PIPAC in Indian patients with a low morbidity and mortality and short hospital stay. While clinical trials will determine its role in addition to systemic chemotherapy, it can be used in patients who have progressed on one or more lines of systemic chemotherapy and those who have chemotherapy-resistant ascites.

Keywords: PIPAC, Indian experience, PIPAC review, Peritoneal metastases

Introduction

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a therapeutic option for selected patients with peritoneal metastases (PM) that can result in a prolonged survival when treated at experienced centers [1]. The patients who are not eligible for this treatment are offered systemic chemotherapy alone. The response rates to systemic therapies are limited in patients with PM and the effect short lived [2]. One of the new therapeutic options in such patients is pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) that has shown good response rates in patients who have progressed on one or more lines of chemotherapy. PIPAC is currently used only in the palliative setting and is being prospectively evaluated in phase I and II trials. Pending the results of these trials, it is in clinical use for selected patients. This procedure that involves administering aerosolized chemotherapy in a carbon-dioxide pneumoperitoneum requires a special device to generate the aerosol and has certain safety measures that need to be followed. This manuscript describes the technical aspects of performing this procedure in the Indian setting and the perioperative outcomes of the first 16 patients treated at 3 Indian centers.

Materials and Methods

From May 2017 to August 2017, data was collected prospectively for all patients undergoing pressurized intraperitoneal chemotherapy at three Indian centers. The patients’ characteristic, operative findings, and perioperative outcomes were recorded for all patients. The various processes involved in starting a PIPAC program are described here.

Permissions and Patient Education

Permission from the institutional review board was obtained at each center. A special patient information leaflet and consent form for the procedure was used. Patients were educated and counseled about the procedure. A standard operating procedure laying emphasis on handing of the chemotherapeutic agents was prepared. Staff training was performed to educate the health care personnel involved about the procedure.

Indications

The indications included patients with colorectal and ovarian cancer progressing on two or more lines of chemotherapy, patients with gastric PM progressing after first line of chemotherapy, ascites not responsive to chemotherapy, and patients with any primary site not eligible for CRS and HIPEC. These indications are not all inclusive and are based on the results obtained from retrospective studies showing a clinical response to PIPAC in these situations [3].

Fitness for the Procedure

Patients were eligible if they had blood counts, liver, and renal function test within the normal range with a good performance status (ECOG ≤ 2); all patients had one or more tumor masses which could be evaluated on CT scan. CT scans were performed for response evaluation using RECIST criteria when clinically indicated and not after every procedure. Tumor marker response and clinical response were evaluated and recorded.

Set-up

The generation of the aerosol requires a microinjection pump (Capnopen®, Capnomed, Villingendorf, Germany) which is a single use disposable device. Apart from this, a high pressure injector (Arterion Mark 7®, Medrad, Bayer, Germany) is required. Since the pressure injector is available in the cardiac catheterization laboratory and is not portable, the procedure was performed there instead of the operating room in two of the three centers. A table mounted abdominal wall retractor is required in addition to hold the camera in place when the procedure is being performed. The operating area should have a laminar air flow.

Training for the Procedure

For using the microinjection pump, product training is required and all three surgeons completed the certified training for the same.

Technique of PIPAC

The procedures were performed following the protocol laid down by the pioneering surgeon and is described here [4].

All operations were performed under general anesthesia; venous thromboembolism prophylaxis was administered, and antibiotic prophylaxis with a single dose of cefuroxime 1.5 g IV was administered at the time of induction of anesthesia. A nasogastric tube and urinary drainage were not used unless there was a specific indication for their use.

After insufflation of a 12 mmHg CO2 pneumoperitoneum (with open access or Veres needle), two balloon trocars measuring 5 and 12 mm were inserted into the abdominal wall. The preferred sites of insertion were the left subcostal region in the mid-clavicular line and in the left iliac fossa along the same line.

An evaluation of the PCI was done. Biopsies were performed from four different regions of the peritoneal cavity, and ascitic fluid was completely drained and sent for cytological examination.

The 9-mm microinjection pump was connected to an intravenous high-pressure injector and inserted into the abdomen through the 12-mm access port.

A 5-mm camera was inserted through the other port keeping the tip of the Capnopen in view. A safety checklist was performed which briefly comprised of the following:

Zero flow of CO2 was documented for tightness of the abdomen and to ensure there is no escape of drug.

The patient had to be completely paralyzed using curarizing agents.

The suction device was connected to side port through an outlet channel which was connected to a closed suction unit.

Alternatively, a Buffalo filter, Visiclear®, New York, USA, was used.

A polythene sheet was placed on the floor under the outlet tube to prevent contamination in case of a spill.

The video laparoscopy and anesthesiology monitors were turned towards the window to facilitate patient monitoring from outside the operating room.

The chemotherapy injection was remote-controlled, and nobody remained in the operating room during the application (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PIPAC procedure in progress—all personnel are out of the operating room during the procedure

One hundred fifty milliliters of NaCl 0.9% containing cisplatin 7.5 mg/m2 body surface and doxorubicin 1.5 mg/m2 body surface area or oxaliplatin 92 mg/m2 body surface in 150 ml dextrose was injected through the Capnopen at a pressure of 200 psi at the rate of 1 ml/s to generate the aerosol. The intra-abdominal pressure throughout the procedure was maintained at 12 mmHg [8].

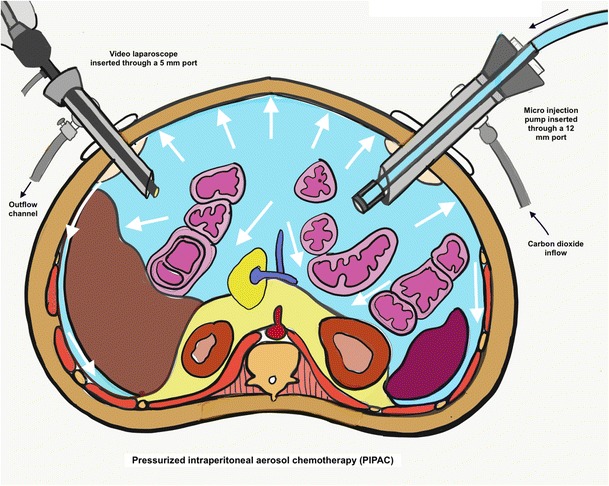

The therapeutic capnoperitoneum was then maintained for 30 min (Fig. 2). Then, the chemotherapy aerosol was exsufflated via a closed line into a closed suction system that solidifies the aerosol. The hospital air-waste systems are not designed to handle chemotherapeutic agents, and hence, this alternative was employed deviating from the recommendations of the pioneering institute. One center used a “buffalo filter for the same.” Finally, trocars were retracted and laparoscopy was ended.

Fig. 2.

Diagramatic representation of the pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy. (Adapted from reference [4] with permission)

Abdominal drains were not inserted. Nasogastric tube and urinary catheter if inserted were removed at the end of the operation.

Patients were allowed oral liquids on the same day and discharged on the following day in the absence of adverse events.

Perioperative Outcomes

Post-operative management was in the ward, and routine intensive care admission was not done. Adverse events were recorded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4 [5].

Histological Criteria of Tumor Regression

On visual inspection, it was possible to determine a general pattern of tumor regression (change in consistency, progressive scarring, and vanishing of ascites) in patients who undergo subsequent PIPAC procedures. The histopathological response was assessed and graded according to the generic score devised by Solass et al. [6].

Results

From May 2017 to July 2017, 17 PIPAC procedures were performed in 16 patients. There were 5 males and 12 females. The primary tumor site was ovary in eight patients (47.0%), appendix in four (23.5%), colon in three (17.6%), and stomach in two (11.7%). Three patients had an ECOG performance status of two, and all others had a performance status of 0–1. The volume of ascites was > 1 l in two patients. Thirteen patients received prior chemotherapy with a mean number of 3.1 lines per patient (range 1–4 lines). Of the four patients who had not received chemotherapy, a PIPAC was used for palliation in two patients aged > 75 years who did not wish to undergo CRS for low-grade pseduomyxoma peritonei from appendiceal primary tumors. In two other patients with colon and gastric cancer with extensive PM, PIPAC was used with systemic chemotherapy to produce tumor downstaging. One patient underwent pressurized intra-thoracic aerosol chemotherapy (PITAC) for pleural effusion from a recurrent ovarian tumor; for the PM, a simultaneous PIPAC was planned but could not be performed due to laparoscopic non-access. Patient and tumor characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 16 patients undergoing PIPAC

| No. | Age | Sex | Primary site | No. of chemotherapy lines | Prior CRS | Prior HIPEC | Ascites (volume in cc) | Bowel obstruction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | Female | Ovary | 4 | Yes incomplete | No | Yes (5000) | No |

| 2 | 62 | Male | Appendix | 2 | No | No | Yes (2000) | No |

| 3 | 72 | Male | Stomach | 1 | No | No | No | No |

| Female | Ovary | 4 | Yes incomplete | No | No | Yes | ||

| 4 | 45 | Female | Ovary | 4 | Yes incomplete | No | No | Yes |

| 5 | 48 | Female | Ovary | 4 | Yes complete | No | Yesa (2000) | No |

| 6 | 47 | Female | Ovary | 4 | Yes complete | No | Yes (< 500) | No |

| 7 | 58 | Female | Ovary | 2 | Yes complete | No | Yes (500) | No |

| 8 | 77 | Female | Appendix | 0 | Yes incomplete | No | Yes (50) | No |

| 9 | 30 | Male | Colon | 2 | No | No | No | No |

| 10 | 48 | Female | Ovary | 4 | Yes complete | No | Yes (1000) | No |

| 11 | 44 | Male | Stomach | 0 | No | No | Yes | No |

| 12 | 52 | Female | Ovary | 3 | Yes | No | No | No |

| 13 | 43 | Female | Appendix | 1 | No | No | Yes | No |

| 14 | 75 | Male | Appendix | 0 | No | No | Yes | No |

| 15 | 45 | Female | Colon | 3 | No | No | Yes | No |

| 16 | 45 | Male | Colon | 0 | No | No | Yes | No |

| 17 | 54 | Female | Ovary | 3 | Yes | No | Yes | No |

The mean operating time was 142 min (range 75–160). Laparoscopic access could not be obtained in two of the patients, and they were excluded from this analysis. The mean hospital stay was 2.35 (range 1–12 days) days, and the median stay was 1 day. Mean PCI was 25.1 (range 7–39). CTCAE grades 1–2 adverse events were observed in two patients (11.7%), and grade 3–4 adverse events in two patients (11.7%). One patient developed renal dysfunction possibly due to hypotension resulting from sudden decompression of massive ascites, and it resolved with fluid therapy and albumin. One patient developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and died on the 12th post-operative day. The second patient developed cardiac arrest on the second post-operative day from which he was revived. Another patient developed obstruction of the colorectal primary tumor on the seventh post-operative day for which a surgical intervention was needed; this was unrelated to the PIPAC procedure. There was one post-operative mortality (5.8%). The operative findings and perioperative outcomes are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Operative findings and perioperative outcomes in patients undergoing PIPAC

| No. | Non-access | PCI | Drug/s used | Additional surgical procedure performed | Operative time (min) | Hospital stay (days) | Grade 1 and 2 adverse events | Grade 3 and 4 adverse events | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No | 24 | Cisplatin + adriamycin | 184 | 5 | Large volume paracentesis-related renal dysfunction. Settled with albumin and diuretics | Nil | No | |

| 2 | No | 32 | Cisplatin + adriamycin | 95 | 7 | Nil | Cardiac arrest; patient resuscitated and discharged | No | |

| 3 | No | 7 | Cisplatin + adriamycin | 98 | 2 | Nil | Nil | No | |

| 4 | No | 28 | Cisplatin + adriamycin | 150 | 12 | Nil | ARDS—respiratory failure | Yes | |

| 5 | No | 26 | Cisplatin + adriamycin | 120 | 1 | Nil | Nil | No | |

| 6 | No | 28 | Cisplatin + adriamycin | 160 | 1 | Nil | Nil | No | |

| 7 | No | 18 | Cisplatin + adriamycin | 120 | 1 | Nil | Nil | No | |

| 8 | No | 14 | Oxaliplatin | 120 | 2 | Nil | Nil | No | |

| 9 | No | 30 | Oxaliplatin | 140 | 1 | Nil | Nil | No | |

| 10 | No | 26 | Cisplatin + adriamycin | Adhesionolysis | 100 | 1 | Nil | Nil | No |

| 11 | No | 3 | Cisplatin + adriamycin | 120 | Nil | Nil | No | ||

| 12 | No | > 34 | Cisplatin + adriamycin | 75 | 1 | Nil | Nil | No | |

| 13 | No | Cisplatin + adriamycin | 130 | 1 | Nil | Nil | No | ||

| 14 | No | 27 | Oxaliplatin | 120 | 1 | Nil | Nil | No | |

| 15 | No | Not evaluated | Oxaliplatin | 90 | 1 | Infection | Nil | No | |

| 16 | No | 37 | Oxaliplatin | 120 | 1 | Nil | Nil | No | |

| 17 | No | 39 | Oxaliplatin | 120 | 1 | Nil | Nil | No |

Six out of 17 patients (35.2%) had completed 6 weeks of follow-up. Disease progression was seen in two patients. A clinical response was seen in four patients of which one patient who had previously refused CRS and HIPEC agreed for the same, in one, the second procedure was delayed due to a low platelet count, and another patient had to undergo surgery for an obstructed primary tumor due to which the second procedure was delayed. A second procedure was performed in one patient.

Discussion

PIPAC is a new method of intraperitoneal drug delivery and involves off-label use of chemotherapeutic agents. Aerosolized chemotherapy is sprayed in to the peritoneal cavity in the setting of a carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum—also known as “therapeutic capnoperitoneum.” The technique which was developed by Prof. Marc Reymond from Germany has several advantages over other methods of intraperitoneal chemotherapy, one of which is increased penetration of drug into the tumor nodules using 1/10 the dose of systemic chemotherapy [4]. This is achieved by the synergistic effect of raised intra-abdominal pressure and aerosolized chemotherapy [4].

The intraperitoneal drug distribution is more homogenous in PIPAC [7]. It has other advantages like being simple to perform with no learning curve, being well tolerated and the feasibility of concurrent use with systemic chemotherapy [8]. Multiple applications, each performed at 6–8 weeks after the previous one, are possible and both a visual and pathological response evaluation is possible. The reduced dose leads to substantially fewer systemic side effects compared to other methods of intraperitoneal chemotherapy. The reported rate of complications ranges from 0 to 12% [3]. One study in which PIPAC was performed after CRS reported a high incidence of bowel perforations, and currently performing PIPAC with CRS is not recommended [9].

Currently, PIPAC is an experimental therapy, being evaluated in clinical trials (NCT02735928, NCT0185425, NCT02320448) for patients who are not eligible for CRS and HIPEC; however, there are certain indications for which it can be used outside clinical trials. Patients with PM who have progressed on one or more lines of systemic chemotherapy can be offered PIPAC depending on the primary tumor site [10]. For patients who experience severe side effects of systemic chemotherapy or do not want systemic chemotherapy, PIPAC is an option. It can be used for chemotherapy refractory malignant ascites. It is important to properly counsel patients about PIPAC being an experimental therapy and its benefits in comparison to best supportive care/palliative chemotherapy.

In the clinical setting, response rates to 60–70% for colorectal, gastric, and recurrent ovarian cancer have been reported which are based on radiological and pathological evaluation [3]. Most of the published reports are case reports, prospective and retrospective case series, and a phase II trial. PIPAC has shown good results in two difficult clinical situations—platinum-resistant ovarian cancer and gastric cancer with metachronous PM [9, 11, 12]. It has shown response in patients with PM of pancreatic origin and in elderly patients who are not eligible for chemotherapy [13, 14].

Our results show the feasibility of PIPAC in Indian patients with similar rates of laparoscopic non-access, morbidity, and mortality as previously published reports (two patients; 11.7% for all three parameters). In patients who have had prior extensive surgery or have extensive disease leading to adhesions, laparoscopic access may not be possible; the reported rates range from 0 to 17% [9]. Apart from this, the procedure does not have technical challenges like CRS and HIPEC. This procedure has a reported morbidity rate of 0–12%; major morbidity is uncommon. One series that combined CRS and PIPAC showed a high incidence of bowel perforation, and hence, combining CRS and PIPAC is not currently recommended. Most patients require only a day or two of hospital admission, and intensive care admission is not required; this was seen in our patients as well with a median hospital stay of 1 day and mean of 2.3 days.

To avoid inadvertent exposure of healthcare workers to aerosolized chemotherapy, the safety guidelines and protocols have been well established by the pioneering institute and these can be easily and effectively duplicated [15]. Though in principle, PIPAC seems to be a promising option, proper patient selection is important. Patients who have bowel obstruction, massive ascites leading to debility, and malnutrition and those with a poor performance status are unlikely to benefit from the procedure. Appropriate patient selection with good monitoring is essential to avoid mortality and significant morbidity so as to pursue this in larger numbers in the future for research.

In our preliminary experience, morbidity was observed in the two patients that had a performance status of ≥ 2. PIPAC was used in two patients who were treatment naïve and had extensive PM not amenable to CRS and HIPEC. In these patients, PIPAC was used as an adjunct to systemic chemotherapy in order to downstage the disease. In a retrospective study, PIPAC led to reduction in the disease extent making CRS and HIPEC feasible in a small percentage of patients [16]. Such a treatment strategy is currently being evaluated in two clinical trials for colorectal and gastric cancer (PIPAC EstoK 01 trial).

In the palliative setting, the ideal timing for introducing PIPAC in the disease timeline is unclear—whether it should be performed for asymptomatic patients or when patients start becoming symptomatic?

Only 6 out of 16 patients had completed 6 weeks of follow-up (excluding one perioperative mortality), and it is not possible to draw conclusions on the efficacy. A minimum of three procedures is recommended for each patients for a durable response. Only one of the six patients underwent the stipulated second procedure. This underlines the importance of the disease timeline when this therapy is introduced. Despite its low toxicity, the disease timeline when procedure is performed is important and the therapy should be introduced early in course of the disease process to obtain the maximum benefit. Dose escalation studies (NCT02475772) as well as safety and efficacy studies for other chemotherapy agents are underway to determine the optimal drug regimens for the procedure. Some investigators have suggested that PIPAC should be combined with systemic chemotherapy to obtain the maximal benefit [17].

Conclusions

Our results show the feasibility and safety of PIPAC in Indian patients. The procedure is simple to perform and in appropriately selected patients had a low morbidity and mortality and a short hospital stay. The possibility of multiple applications and combining it with systemic chemotherapy along with the pharmacokinetic advantages make it a suitable option for patients with extensive PM that cannot be treated with CRS and HIPEC. While clinical trials will determine its role as an alternative and/or adjunct to systemic chemotherapy, it can be used in patients who have progressed on one or more lines of systemic chemotherapy and those who have chemotherapy-resistant ascites.

References

- 1.Glehen O, Elias D, Gilly F-N. Carcinoses Péritonéales D’Origine Digestive et Primitive: Rapport du 110ème Congrès de L’Association Française de Chirurgie—Monographie de L’Association française de Chirurgie. Arnette: Rueil-Malmaison, France; 2008. pp. 101–151. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franko J, Shi Q, Meyers JP, et al. (2016) Prognosis of patients with peritoneal metastatic colorectal cancer given systemic therapy: an analysis of individual patient data from prospective randomised trials from the Analysis and Research in Cancers of the Digestive System (ARCAD) database. Lancet Oncol; published online Oct 12. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30500-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Grass F1, Vuagniaux A1, Teixeira-Farinha H1, Lehmann K2, Demartines N1, Hübner M1 (2017) Systematic review of pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced peritoneal carcinomatosis. Br J Surg 104(6):669–678. 10.1002/bjs.10521 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Solass W, Kerb R, Mürdter T, Giger-Pabst U, Strumberg D, Tempfer C, Zieren J, Schwab M, Reymond MA. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy of peritoneal carcinomatosis using pressurized aerosol as an alternative to liquid solution: first evidence for efficacy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(2):553–559. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3213-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.https://evs.nci.nih.gov/.../CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_8.5x11.p...CTCAE4.03. Common Terminology Criteria for. Adverse Events (CTCAE). Version 4.0. Published: May 28, 2009 (v4.03: June 14, 2010)

- 6.Solass W, Sempoux C, Detlefsen S, Norman JC, Bibeau F. Peritoneal sampling and histological assessment of therapeutic response in peritoneal metastasis: proposal of the peritoneal regression grading score (PRGS) Pleura Peritoneum. 2016;1:99–107. doi: 10.1515/pp-2016-0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solass W, Hetzel A, Nadiradze G, Sagynaliev E, Reymond MA Description of a novel approach for intraperitoneal drug delivery and the related device. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1849–1855. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanco A, Giger-Pabst U, Solass W, Zieren J, Reymond MA. Renal and hepatic toxicities after pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(7):2311–2316. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2840-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nadiradze G, Giger-Pabst U, Zieren J, Strumberg D, Solass W, Reymond MA. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) with low-dose cisplatin and doxorubicin in gastric peritoneal metastasis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;20(2):367–373. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2995-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hübner M, Teixeira Farinha H, Grass F, Wolfer A, Mathevet P, Hahnloser D, Demartines N. Feasibility and safety of pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis: a retrospective cohort study. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:6852749. doi: 10.1155/2017/6852749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demtroder C, Solass W, Zieren J, Strumberg D, Giger-Pabst U, Reymond MA. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) with oxaliplatin in colorectal peritoneal metastasis. Color Dis. 2015;18(4):364–371. doi: 10.1111/codi.13130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tempfer CB, Winnekendonk G, Solass W, Horvat R, Giger-Pabst U, Zieren J, Rezniczek GA, Reymond MA. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy in women with recurrent ovarian cancer: a phase 2 study. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(2):223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graversen M, Detlefsen S, Bjerregaard JK, Pfeiffer P, Mortensen MB. Peritoneal metastasis from pancreatic cancer treated with pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) Clin Exp Metastasis. 2017;34:309–314. doi: 10.1007/s10585-017-9849-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giger-Pabst U, Solass W, Buerkle B, Reymond MA, Tempfer CB. Low-dose pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) as an alternative therapy for ovarian cancer in an octogenarian patient. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(4):2309–2314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solass W, Giger-Pabst U, Zieren J, Reymond MA. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC): occupational health and safety aspects. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(11):3504–3511. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3039-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girshally R, Demtröder C, Albayrak N, Zieren J, Tempfer C, Reymond MA. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) as a neoadjuvant therapy before cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:253. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-1008-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robella M, Vaira M, De Simone M. Safety and feasibility of pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) associated with systemic chemotherapy: an innovative approach to treat peritoneal carcinomatosis. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:128. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0892-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]