Abstract

Oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC) are among the commonest cancers in South East Asia and more so in the Indian subcontinent. The role of tobacco and alcohol in the causation of these cancers is well-documented. Poor oral hygiene (POH) is often seen to co-exist in patients with OSCC. However, the role of poor oral hygiene in the etio-pathogenesis of these cancers is controversial. We decided to evaluate the available literature for evaluating the association of POH with OSCC. A thorough literature search of English-language articles in MEDLINE, PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Web of Science databases was conducted, and 93 relevant articles were short-listed. We found that POH was strongly associated with oral cancers. It aids the carcinogenic potential of other known carcinogens like tobacco and alcohol. Even on adjusting for known confounding factors like tobacco, alcohol use, education, and socio-economic strata, presence of POH exhibits higher odds of developing oral cancer.

Keywords: Mouth neoplasm, Oral cancer, Poor oral hygiene, Tooth brushing, Dental visits, Missing teeth

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC) are one of the most common cancers in the Indian subcontinent. India has the highest incidence of OSCC patients in the world. In 2015, approximately 80,000 new cases of OSCC were reported in the country and approximately 50,000 died of it [1]. This is a matter of grave concern not only for the health care professionals but also for the public at large.

Tobacco and alcohol consumption have been thought to be the major culprits for causing OSCC. OSCC prevalence is higher in areas where tobacco is used in smokeless forms. It is believed that apart from established etiological factors like tobacco, alcohol, and areca nut, other factors like chronic mucosal trauma [2, 3, 4], poor nutrition [5, 6], and poor oral hygiene (POH) may contribute to oral carcinogenesis [7].

POH has been considered as a risk factor for causing OSCC in several studies [8–10, 11]. Still, there is a definite lacuna in the knowledge about oral hygiene as a cause for OSCC and its etio-pathogenic mechanism. Therefore, through this review of literature, we have tried to shed light on the impact of POH on oral carcinogenesis.

Methodology

We searched the databases MEDLINE, PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Web of Science through November 2017. The search terms used were “oral cancer,” “mouth neoplasm” (which is a mesh term for oral cancer), “oral hygiene,” “missing teeth,” “halitosis,” “bad odor,” and “teeth brushing.” These were searched as text word and as subject headings individually as well as in different combination which accounted for a total of 523 articles. While searching for “mouth neoplasm” and “oral cancer” with “bad odor,” we could not get any results. Abstracts, headings, and titles of all the results were studied, and we excluded repetitions and those which failed to describe the factors of interest for the study. We short-listed 93 relevant articles, including retrospective studies, review articles, case-control studies, questionnaire-based surveys, cohorts, and randomized control trials. Some cross-references from these articles, which were found to be relevant for the topic, were also included.

Quantification of Poor Oral Hygiene

The assessment of oral hygiene is mostly done subjectively. There have been efforts to quantify it or objectively assess it. It has been quantified using various indices, like the Oral Hygiene Index—Simplified (OHI-S), Community Periodontal Index and Treatment Needs (CPITN), Plaque Index (PI), Gingival Index (GI), and Decayed Missing Filled Teeth Index (DMFT). Although they bring uniformity, most of the indices are highly complicated and can be used only by trained dental professionals. During our review of literature, we found that the majority of studies, instead of using these indices, utilized various other parameters as a measure of POH, like tooth brushing frequency, regular dental visit, number of missing teeth in oral cavity, and use of mouthwash/dental floss.

Causative Factors of Poor Oral Hygiene

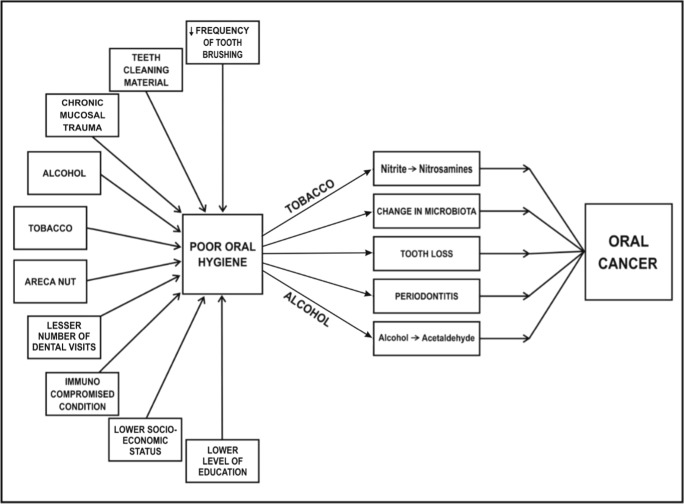

Factors contributing to POH include irregular teeth brushing habits, less number of dental visits, poor socioeconomic status, lower level of education, tobacco, and alcohol consumption (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Factors and mechanisms by which poor oral hygiene can cause oral carcinogenesis

Tooth Cleaning Habits

In the Indian subcontinent, a large number of people still do not use tooth brush and paste to clean their teeth. A case-control study in southern India assessed the influence of smoking, alcohol, paan (betel quid) chewing, and oral hygiene in causation of OSCC in 591 cases and 582 controls [12]. They found that majority of participants, both cases and controls, (80.73%) did not brush teeth more than once daily. Females who brushed their teeth once or even less daily had significantly increased risk of OSCC (OR 3.39). Even individuals who used their fingers for cleaning of teeth had significantly higher chances of oral malignancy irrespective of gender (males OR = 1.75; females OR = 3.40) compared to those who used tooth brush. A large number of males diagnosed with OSCC in this study were found to use various teeth cleaning aids other than tooth brush and fingers (OR = 3.65, 95% CI 1.50–8.84). People still use plant sticks [9, 12], salt [13], ash [14], charcoal [15], and even brick powder to clean their teeth [13, 14]. Even tobacco is used as a tooth cleaning agent in certain parts of India [15], available by various names viz. Gul-manjan, Masheri, and gadakhu. In another case-control study assessing dental and periodontal status in patients with OSCC, it was found that 93.4% of cancer cases reported to have brushed their teeth less than once daily as compared to 81.1% controls [9]. In an analysis of two multi-center case-control studies held in Central Europe and Latin America, it was found that lack of tooth brush use-causing POH were risk factor for HNC (independent of tobacco and alcohol use) [8]. A meta-analysis assessing 18 case-control studies has highlighted the advantageous role of brushing teeth twice daily in reducing the risk of HNC to half (OR = 2.08, 95% CI = 1.65–2.62) [16] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Association of frequency of teeth brushing (fully adjusted for confounding factors) as a causative factor of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC)/ Head and Neck Cancer (HNC)/ Carcinoma of Oral Cavity and Oropharynx (OCP)/ Upper Airway and Digestive Tract (UADT)Cancers

| STUDY | COHORT | FREQUENCY | OR | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen [15] | OSCC | >=2 | 0.88 | 0.46-1.68 |

| Chang [16] | OSCC | >=2 <2 |

1 1.45 |

- 0.92-2.27 |

| Guneri [17] | OSCC | <1 | 0.170 | - |

| Balaram [10] | OSCC | <=1 | M= 0.96 F = 3.39 |

0.59–1.59 1.65–6.98 |

| Talamini [18] | OSCC | >=2 1 <1 |

1 1.1 1.4 |

- 0.5-2.4 0.6-3.3 |

| Zheng [19] | OSCC | Never | M= 6.9 F = 2.5 |

2.5 - 19.4 0.9 - 7.50 |

| Franco [20] | OSCC | Infrequent | 2.3 | 1.4-3.7 |

| Kawakita [21] | HNC | <=1 | 1.13 | 0.89-1.44 |

| Hashim [22] | HNC | 1/Day | 0.83 | 0.79-0.88 |

| Tsai [23] | HNC | <2 | 1.40 | 1.02–1.91 |

| Guha [7] (Central Europe) |

HNC | >=2 1 <1 Never |

1 1.38 1.00 1.37 |

- 0.79-2.41 0.51-1.95 0.65-2.88 |

| Guha [7] (Latin America) |

HNC | >=2 1 <1 Never |

1 0.94 0.74 1.20 |

- 0.67-1.32 0.44-1.23 0.30-4.79 |

| Marques [24] | OCP | 1-2 <1 Never |

0.7 0.7 1.3 |

0.5-1.2 0.3-1.5 0.4-4.5 |

| Garrote [25] | OCP | >=2 1 <1 |

1 1.17 1.94 |

- 0.52-2.66 0.83-4.50 |

| Ahrens [26] | UADT | 2/Day 1/Day 1-4x / Week <1/WeekORNever |

1 1.25 1.39 1.37 |

- 1.03-1.53 1.03-1.87 0.95-1.99 |

| Sato [27] | UADT | Not brushing Once daily Brushing>1/ day |

6.11 1 0.81 |

1.35-27.6 - 0.57 -1.14 |

Surprisingly, there have been a couple of studies which have failed to find any correlation between tooth cleaning habits, POH, and OSCC. A case-control study could not find any association between the frequency of tooth brushing in causing cancers of upper airway and digestive tract (UADT) [8, 30, 31].

Frequency of Dental Visits

Due to the symptomatology associated with oral cancers, dentists are often the first contact person for oral cancer detection [32]. Thus, higher frequency of their consultation would certainly help in maintaining oral hygiene and allow early detection of cancer or precancerous lesions [33–35]. A pooled analysis of 13 case-control studies with a large sample size assessed the association of POH and head and neck cancers (HNC). They hypothesized that annual dental visits were associated with more than 25% reduction in HNC for patients with gingivitis/periodontitis (OR = 0.82; 95% CI 0.78, 0.87) [24]. A case-control study in an Indian tertiary care center pointed that all of the OSCC patients evaluated in the study for oral hygiene status used to visit dentist less than once a year [36]. These results were quiet similar to that of Laprise et al. who found that 93% of the oral cancer cases did not visit a dentist on regular terms [37]. Narayan et al. in their study found that more than half of the cases (57.85%) never had a dental visit when compared to controls (46.06%) [9]. Balaram et al. found dental check-up gives significant protection from cancers of oral cavity in females (OR 0.4 with 95% CI of 0.19–0.87), but it was not found to be significant in males (OR = 0.89 with 95% CI 0.56–1.42) [12] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association of Number of dental visits (fully adjusted for confounding factors) as a causative factor of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC)/ Head and Neck Cancer (HNC)/ Carcinoma of Oral Cavity and Oropharynx (OCP)/ Upper Airway and Digestive Tract Cancers (UADT)

| STUDY | COHORT | FREQUENCY | OR | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen [15] | OSCC | 0/Year <1 >=1 |

1 0.92 0.39 |

1 0.35-2.38 0.08-1.85 |

| Chang [16] | OSCC | Every 6 months or less 6-12 No |

1 0.81 3.73 |

1 0.13-4.96 1.60-8.72 |

| Guneri [17] | OSCC | Infrequent | 0.171 | - |

| Rosenquist [36] | OSCC | Regular | 0.4 | 0.2-0.6 |

| Balaram [10] | OSCC | Yes | M= 0.89 F= 0.41 |

0.56–1.42 0.19–0.87 |

| Talamini [18] | OSCC | >=1 in 5 years <1 in 5 years |

0.8 1.1 |

0.4-1.6 0.5-2.6 |

| Franco [20] | OSCC | <1/ year >=1/ year |

0.6 0.6 |

0.3-1.3 0.1-2.3 |

| Kawakita [21] | HNC | >=1 /year 1/ 2-4 years 1/>=5 years never |

1 1.72 2.09 3.70 |

1 1.10-2.67 1.40-3.14 2.51-5.45 |

| Hashim [22] | HNC | >=1/ year | 0.82 | 0.78-0.87 |

| Tsai [23] | HNC | <=6 months 6-12 months No |

1 0.78 2.19 |

- 0.30-2.04 1.30-3.70 |

| Divaris [37] | HNC | Routine visit | 0.68 | 0.53-0.87 |

| Marques [24] | OCP | Occasional Never |

1.5 2.25 |

0.8-2.8 1.3-4.8 |

| Garrote [25] | OCP | >=1 in 5 years <1 in 5 years |

1.61 0.71 |

0.83-3.07 0.64-1.86 |

| Ahrens [26] | UADT | Every year 2-5 years <5 years never |

1 1.25 1.52 1.93 |

1 1.02-1.53 1.23-1.87 1.48-2.51 |

Education Level

A questionnaire-based survey among Brazilian population found that the education level among the subjects had a direct influence on the knowledge about main oral diseases [40]. An Indian study categorized the participants in the study by their level of education as no education, basic education (up to 6 years), and higher education and found that OSCC cases were significantly lesser educated as compared to control subjects. This study also showed direct association between the level of education of spouse and risk of cancer [12]. A Chinese study assessing the influence of oral hygiene and its interaction with standard of education on the risk of oral cancer in women (adjusted for smoking and alcohol use) found that protection assumed due to tooth brushing twice a day was negated if the education of the subject was below high school. Only females with no habit abuse were included in this study; thus, there were no other confounding factors [17].

Arecanut, Tobacco, and Alcohol

Arecanut, tobacco, and alcohol habits may result in POH. These habits are an independent etiological factor for oral cancer [40–42]. They also promote POH which in turn may act as contributory factor for oral cancer [43]. Arecanut has been proven to cause POH, periodontal diseases, and precancerous conditions, which further deteriorates oral hygiene. Maier et al., in a Germany-based case-control study, have described chronic alcoholism to be a causative factor for neglecting oral health, leading to POH [33, 44, 45]. Tobacco use deteriorates oral hygiene represented by various indicators like tooth loss, dental caries, and periodontal diseases [46, 47].

Poor Oral Hygiene—an Additive Factor for Oral Carcinogenesis

Poor oral hygiene and areca nut: Areca nut usage is associated with oral pre-malignant conditions, such as oral submucous fibrosis, as well as OSCC. The particles of areca nut itself along with the oral submocous fibrosis being a resultant of areca nut chewing cause POH in quid chewers. This has predominantly been seen in South-Central and South-East Asia, where areca nut usage is very common not only as a habit but also as a part of culture and religious customs. Moreover, the individuals consuming it, especially without tobacco, are not even aware of its adverse effects. The OSCC which develops in the presence of oral sub-mucous fibrosis is believed to be a clinico-pathologically distinct entity.

Poor oral hygiene and tobacco: The role of POH in the formation of N-nitroso compounds was investigated by means of the NPRO assay. Endogenous nitrosation was significantly higher in tobacco chewers with POH (having greater plaque levels) compared to those who had good oral hygiene [48, 49]. NPRO levels in saliva of subjects with POH were found to be higher (190 μg NPRO/L) compared to those with good oral hygiene (24 μg NPRO/L) [50]. A case-control study assessing the oral conditions as risk factors for oral cancers found that the participants who smoked tobacco had greater missing teeth, representing POH were at greater risk of having oral cancer (OR = 7.3) than those who had a maintained oral hygiene and smoked tobacco (OR = 2.0) [21]. Thus, formation of nitrosamines is more extensive in tobacco users who have POH than those with better oral hygiene, thereby increasing the carcinogenic potential of tobacco.

Poor oral hygiene and alcohol: Alcohol is a known carcinogen involved in causation of oral cancer [51, 52]. A Chinese case-control study found that subjects who consumed alcohol and had POH (represented by inadequate dentition) had 5 times more risk of having oral cancer (OR = 9.1, 95% CI = 4.4–19) than those who just consumed alcohol but maintained a good oral hygiene (OR = 1.8, 95% CI = 0.7–4.7) [21]. According to a case-control study, the attributable risk percentage for causing OSCC due to alcohol consumption was 26% while that due to POH was 32%. This clearly shows that the effect of POH in causing OSCC was more significant as compared to that of alcohol in this particular study [12].

Periodontitis and tooth loss: POH is the main etiological factor for periodontitis [53], a plaque-induced chronic inflammatory disease. Tooth loss is an end result of POH [18] and is reported to be associated with oral cancer [54]. According to a meta-analysis studying relationship of tooth loss and HNC, tooth loss was found to be a significant risk factor for developing HNC. In fact, it was noted to have a dose-response effect too (> 5 vs. ≤ 5 OR 2.00, 95% CI 1.28–3.14; p = 0.002) [55]. However, this meta-analysis had substantial heterogeneity in the included studies (I2 = 82.9%; P = 0.000). People who lost six or more teeth are at a higher risk of HNC, and losing 11–15 teeth may be the threshold. Out of twelve studies included in this meta-analysis, seven were related to cancer of oral cavity and pharynx. A Chinese hospital-based case-control study aimed to assess the role of oral hygiene and dental conditions in the genesis of oral cancer. They found a strong correlation of missing teeth, which reflected POH, as a strong risk factor for oral cancer after adjustment for tobacco smoking and drinking habits. They found that adjusted ORs in males for missing 3–6 teeth were 4.9 with 95% CI (2.4–10) and for 7–14 teeth were 5.9 with 95% CI (2.8–12.2) [21, 56–58]. A questionnaire-based European case-control study with 8925 HNC cases and 12,527 controls found that HNC were inversely associated with < 5 missing teeth (OR = 0.78; 95% CI 0.74–0.82) [24] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of number of missing teeth (fully adjusted for confounding factors) as a causative factor of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC)/ Head and Neck Cancer (HNC)/ Carcinoma of Oral Cavity and Oropharynx (OCP)/ Upper Airway and Digestive Tract Cancers (UADT)

| STUDY | COHORT | FREQUENCY | OR | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen [15] | OSCC | <=5 >5 |

2.53 2.84 |

0.99-6.48 1.10- 7.34 |

| Chang [16] | OSCC | 1-10 10-20 >20 |

1.15 1.34 2.40 |

0.61-2.20 0.58-3.07 0.97-5.97 |

| Guneri [17] | OSCC | More natural teeth (case, control) |

Mean Cases= 12.04 Controls= 19.3 |

- - - |

| Rosenquist [36] | OSCC | >20 | 3.4 | 1.4-8.5 |

| Balaram [10] | OSCC | >5 | M=3.89 F= 7.61 |

2.46–6.17 3.89–14.88 |

| Talamini [18] | OSCC | <5 6-15 >= 16 |

1 1.1 1.4 |

1 0.5-2.6 0.6-3.1 |

| Zheng [19] | OSCC | Inadequate dentition | 3.9 | 2.1-7.4 |

| Kawakita [21] | HNC | <5 >=5 |

1 1.49 |

1 1.08-2.04 |

| Hashim [22] | HNC | <5 | 0.78 | 0.74-0.82 |

| Divaris [37] | HNC | 0-5 6-15 16-28 |

1 1.07 1.21 |

1 0.81-1.42 0.94-1.56 |

| Guha [7] Central Europe |

HNC | 6-15 | 2.84 | 1.26-6.41 |

| Guha [7] Latin America |

HNC | 6-15 >=16 |

0.87 1.21 |

0.56-1.35 0.77-1.90 |

| Garrote [25] | OCP | <=5 6-15 >=16 |

1 1.82 2.74 |

1 0.76-4.35 1.23-6.12 |

Mechanism of Action

POH may not be a direct causative agent for oral carcinogenesis, but it certainly catalyzes the process by increasing the carcinogenicity of known carcinogens.

Tobacco: Formation of nitrite and nitric oxide in the presence of POH status occurs [8]. Increased formation of nitrite and nitric oxide in the mouth was found in people with dental plaque [48], and bacterial enzyme-mediated formation of nitrosamines has been reported [59]. Nitrate, after its absorption in the upper gastrointestinal tract, reaches the salivary glands via the blood circulation where it is secreted into the oral cavity and partially reduced to nitrite by the oral microflora [60]. Conventional smoking has been found to be the strongest signal of subsequent smoking, e-cigarette use, and nicotine dependence [61]. At least 36 carcinogens have been documented in smokeless tobacco, whereas the International Agency for Research on Cancer has found over 60 carcinogens in cigarette smoke for which there is “sufficient evidence for carcinogenicity” in either laboratory animals or humans [62].

Alcohol: Alcohol is a known carcinogen. Induction of cytochrome P-4502E1-producing free radicals, alterations in normal cell cycle causing hyperproliferation, alterations of the immune system, etc. are various mechanisms by which alcohol causes carcinogenesis [63]. The main carcinogen in alcohol is acetaldehyde which is a group 1 carcinogen. The bacteria prevalent in oral cavity have been hypothesized to convert ethanol in alcohol to aldehyde [64–66]. Tsai et al. in a Taiwanese case-control study found that POH and genetic polymorphisms of alcohol-metabolizing genes (ADH1B and ALDH2) modify the process of carcinogenesis in chronic alcoholics. Although complete abstinence or reduction in alcohol consumption will definitely decrease the occurrence of HNC, a good oral hygiene is supposed to provide additional benefits [25].

Areca nut: Areca nut (a group 1 carcinogen) usage is associated with oral pre-malignant conditions, such as oral submucous fibrosis, as well as OSCC which is believed to be a clinico-pathologically distinct entity [67]. Areca nut extracts cause inhibition of growth, attachment loss, and cessation of matrix protein synthesis of cultured gingival fibroblasts; hence, betel nut chewing affects periodontal health and predisposes to colonization and periodontal disease [68]. Also, the particles of areca nut are hard, which causes abrasion of tooth surfaces. These sharp teeth surfaces cause chronic mucosal trauma which is associated with the development of carcinogenesis [69]. A non-interventional case-control study found significant levels of IL-6 (p < 0.001) and IL-8 (p < 0.0001) in salivary samples of areca nut chewers [68, 70].

C. albicans: Though not very well proven, few retrospective studies have found correlation between C. albicans and oral cancer. Oral cavities with POH may develop opportunistic infections. Candidiasis is one of the commonest lesions in immunocompromised individuals [71]. C. albicans invades keratinocytes either by digestion of surface components of epithelial cells or by surrounding itself by pseudopod-like structures. C. albicans present in oral cavity of an immunocompromised individual can form nitrosamines from their precursors, thereby leading to oral cancer [72]. A case-control study also found a significant association between oral colonization of Candida and oral cancer occurrence (OR = 3.242; 95% CI = 1.505–6.984) [73].

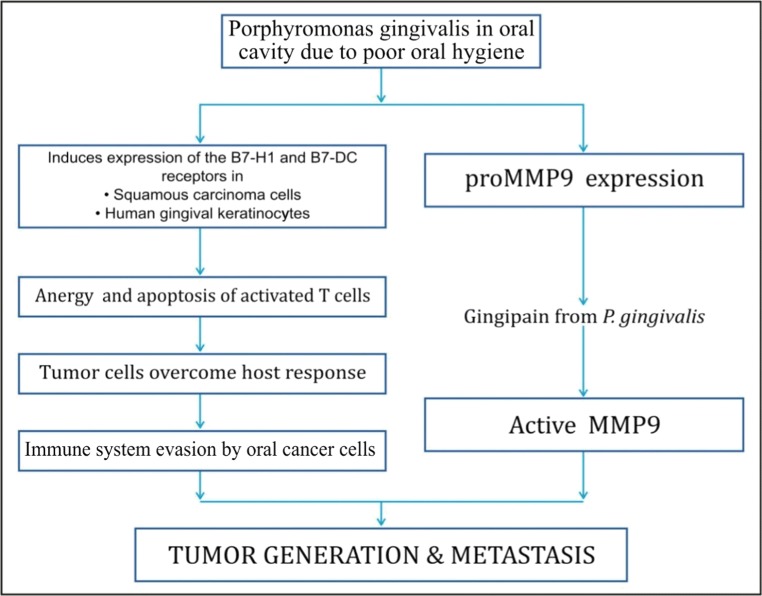

Porphyromonas gingivalis: P. gingivalis, one of the chief pathogens to cause acute periodontitis, has been reported to promote the invasion and metastasis of highly invasive oral cavity cancers [74]. In individuals with POH/periodontitis, infection with P. gingivalis is very common. A case-control study reported P. gingivalis infection in 79% of patients with periodontitis, which was statistically significant (p < 0.0001) [75, 76]. P. gingivalis aids in cancer formation and its metastasis by activation of promatrix metalloproteinase [74, 77] and also by anergy and apoptosis of activated T cells [77, 78] as explained in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Mechanisms of carcinogenesis by Porphyromonas gingivalis in the presence of poor oral hygiene

Oral Hygiene and Oral Cancer

Though most of the studies found POH as an additive factor in causation of oral cancer [79–83], some studies have reported a stronger correlation between the two [84]. A case-control questionnaire-based study adjusted for tobacco and alcohol habit proposed that POH may be a sole causative factor of OSCC. Inclusion criterion for the study was absence of habit abuse among the oral cancer patients; thus, confounding factor in the form of tobacco (smokeless or smoked) and alcohol was said to be negated [85]. However, the study was confined to two specialist hospitals, with low sample size (= 60). The content of the material used for tooth brushing was not mentioned. Oral cavity cancers show ethnic variation, which has also been missed out in the study [86]. An Indian retrospective tertiary hospital-based case-control study found that 79% of the cases of SCC of the oral cavity and oropharynx failed to have a good oral hygiene, compared to the 36% of controls [36]. Similarly, another Indian retrospective study evaluating etiological factors and patient characteristics in oral cancer on 337 patients found that 71% of the cases had poor to very POH [87]. A European case-control study assessed the association of oral health (OH), dental care (DC), and mouthwash use with upper-aerodigestive tract (UADT) cancer risk [28]. They have hypothesized POH as an independent risk factor for UADT cancers. Though almost half of the cases included in the study were oral cavity and oropharynx, the cases with poor oral health (having OH score > 6) were at double the risk of developing oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers (OR = 2.00, 95% CI = 1.21–3.31) as compared to those with better oral hygiene (having OH score = < 6) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association of Poor Oral Hygiene (fully adjusted for confounding factors) as a causative factor of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC)/ Head and Neck Cancer (HNC)/ Carcinoma of Oral Cavity and Oropharynx (OCP)/ Upper Airway and Digestive Tract Cancers (UADT)

| STUDY | COHORT | FREQUENCY | OR | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hashim [22] | OSCC | >=4 3 2 <=1 Worst |

1 2.45 2.42 3.12 |

- 1.93-3.12 1.87-3.15 2.08-4.68 |

| Subapriya [86] | OSCC | Poor | 9.63 | - |

| Balaram [10] | OSCC | Poor | M=4.90 F= 5.99 |

3.09–7.78 3.00–11.96 |

| Talamini [18] | OSCC | Good Average poor |

1 1.8 4.5 |

- 0.9-3.6 1.8-10.9 |

| Kawakita [21] | HNC | 0 (Best) 1 2 >=3 (Worst) |

1 1.99 1.88 4.76 |

- 1.41-2.82 1.30-2.71 2.88-7.85 |

| Tsai [23] | HNC | 1 (Good) 2 3 4 (Poor) |

1 3.50 3.40 5.64 |

- 1.56-7.87 1.54-7.47 2.48-12.83 |

| Guha (2007) [7] Central Europe |

HNC | Poor Average |

4.51 2.24 |

1.95-10.44 1.19- 4.21 |

| Guha (2007) [7] Latin America |

HNC | Poor Average |

2.91 1.28 |

1.87-4.52 0.84-1.96 |

| Dholam [34] | OCP | OHI-S score= 0-2 (Good) OHI-S score= 3-4 OHI-S score= 5-6 (Poor) |

1 4.385 17.4000 |

- 2.112–9.101 5.858–51.686 |

| Rosenquist [36] | OCP | Good Average Poor |

1 2.0 5.3 |

- 1.1-3.6 2.5-11.3 |

| Garrote [25] | OCP | Good Average Poor |

1 1.82 2.55 |

- 0.94-3.53 1.24-5.24 |

| Ahrens [26] | UADT | Low vs High | 2.22 | 1.45-3.41 |

Poor oral hygiene has been hypothesized to contribute to causing oral cancer. However, it may be stated that good oral hygiene may act as a protective barrier against oral cancer [28, 45, 89]. Though many studies from around the world have found a significant or strong correlation between the POH and OSCC/HNC, many still did not find any correlation between the two [8, 27, 90, 91]. Among the Indian population, buccal mucosa forms the commonest site involved in OSCC [9, 36, 37, 88]. If oral hygiene would have been responsible for oral cancer, then we would expect cancer to occur at sites which are more prone to have poor hygiene. Lingual surface of lower incisors have maximum plaque accumulation [92] resulting POH due to lack of maintenance in that particular region, but anterior floor of mouth and anterior lower alveolus are not the most common sites of oral cancers. Thus, reason for buccal mucosa involvement more convincingly appears to be placement of quid among tobacco chewers or chronic mucosal trauma from sharp cusped teeth in others [69].

Studies with Adjustment of Confounding Factors

INHANCE consortium conducted a multi-centric case-control study to evaluate the role of POH as a causative factor for HNC [24]. The study included 8925 patients of HNC and had adjustments done for the use of alcohol, tobacco, smoking, age, sex, race, and educational level. They found that among all HNC, oral cancers had strongest association with POH and that good oral habits decreased the odds of developing oral/HNC—< 5 missing teeth (OR = 0.78; CI 0.74–0.82), annual dentist visit (OR = 0.82; CI 0.78–0.87), and daily tooth brushing (OR = 0.83; CI 0.79–0.88).

Another multi-centric study where adjustment was done for smoking, alcohol, and socio-economic strata included 1963 patients of UADT tumors and 1993 controls [28]. They found that patients with POH had higher odds of developing UADT cancers (OR = 2.22; CI 1.45–3.41). Habits suggestive of POH were involved with higher odds of developing cancer like those who had never visited a dentist were noted to have an OR of 2.22 (CI 1.45–3.41) for developing UADT cancers.

There was a hospital based case-control study where they had adjustment done for ethnicity, education level, tobacco smoking, betel quid chewing, alcohol drinking, etc. [23]. They compared 921 cases of HNC and 806 controls. They also found that lesser dental visits and greater numbers of missing teeth were significantly associated with an increased HNC risk. Poorer oral hygiene was associated with greater odds of developing cancer.

Another study had data included from two centers—one in Central Europe and other in Latin America [8]. They had also done adjustment for education, tobacco pack-years, and cumulative alcohol consumption. They also found that POH had higher odd of developing HNC (OR in Central Europe 4.51; CI 1.95–10.44; in Latin America 2.91; CI 1.87–4.52). In a recent study, on adjusting for tobacco usage, POH was found to be an important factor for causing OSCC, only in tobacco chewers [93].

Indian Scenario

Poor general oral hygiene is observed in the Indian population. This may be due to lack of awareness and low socio-economic conditions. People generally do not brush teeth more than once a day, while some do not even brush daily. Regular dental checkups are not observed by a large population. Due to lack of awareness, a large percentage of cases of dental caries and periodontal diseases use tobacco for local application. Rampant tobacco and gutkha usage with/without alcohol make the condition worse. The Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) recorded a fall in tobacco prevalence in the Indian population from 35% in 2009–10 (GATS-1) to 28% in 2016–17 (GATS-2) [94].

National Oral Health Program

The National Oral Health Program (NOHP) was drafted by the Indian Dental Association (IDA) to address the burden of oral diseases in an effective manner for bringing about “optimal oral health” for all by 2020. It aims to improve total health for all Indians by oral health promotion and disease prevention and to improve knowledge, tools, and networks enabling effective dental practices and programs. It provides information regarding common oral health concerns and creates awareness about importance of oral health which is a better way of early detection of OSCC [95].

Oral cavity screening is a simple and effective tool which may help in detection of oral cancer cases at early stages. A Cochrane’s systematic review suggests that if the disease is treated in early stages, the survival rates are improved. Thus, a systematic examination of the oral cavity by a dental hygienist, dentist, or a general physician should be an integral part of routine check-up, especially in high-risk individuals [96–98]. Oral hygiene can be maintained by regular oral cavity check-up. Beneficial effects of oral cancer screening are well-established by cluster-randomized control trial done in Kerala. Results of this study have shown that oral cancer screening can help in reducing the mortality in high-risk individuals and has the potential in saving at least 37,000 lives worldwide. Thus, oral screening will not only reduce potential carcinogenic effects of POH but also help in diagnosing oral cancer at nascent stages and reducing mortality in high-risk individuals [99–101].

Conclusion

Poor oral hygiene is strongly associated with oral cancers. It aids the carcinogenic potential of other known carcinogens, like tobacco and alcohol. Even on adjusting for known confounding factors, like tobacco, alcohol use, education, and socio-economic strata, presence of POH exhibits higher odds of developing oral cancer.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no any conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012: Globocan 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singhvi HR, Malik A, Chaturvedi P. The role of chronic mucosal trauma in oral cancer: a review of literature. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017;38(1):44–50. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.203510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bundgaard T, Wildt J, Elbrønd O. Oral squamous cell cancer in non-users of tobacco and alcohol. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1994;19(4):320–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1994.tb01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreno-López LA, Esparza-Gómez GC, González-Navarro A, Cerero-Lapiedra R, González-Hernández MJ, Domínguez-Rojas V (2000) Risk of oral cancer associated with tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption and oral hygiene: a case-control study in Madrid. Spain Oral Oncol 36(2):170–174 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Baba ND. Cancer of the oral cavity in three brothers of the whole blood in Mauritania. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:156. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.25.156.10377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thumfart W, Weidenbecher M, Waller G, Pesch HG. Chronic mechanical trauma in the aetiology of oro-pharyngeal carcinoma. J Maxillofac Surg. 1978;6(3):217–221. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(78)80092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behnoud F, Torabian S, Zargaran M. Relationship between oral poor hygiene and broken teeth with oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Med Iran. 2011;49(3):159–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guha N, Boffetta P, Wünsch Filho V, Eluf Neto J, Shangina O, Zaridze D, et al. Oral health and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and esophagus: results of two multicentric case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(10):1159–1173. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narayan TV, Revanna GM, Hallikeri U, Kuriakose MA. Dental caries and periodontal disease status in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma: a screening study in urban and semiurban population of Karnataka. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2014;13(4):435–443. doi: 10.1007/s12663-013-0540-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Velly AM, Franco EL, Schlecht N, Pintos J, Kowalski LP, Oliveira BV, Curado MP (1998) Relationship between dental factors and risk of upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Oral Oncol 34(4):284–291 [PubMed]

- 11.Fossion E, De Coster D, Ehlinger P. Oral cancer: epidemiology and prognosis. Rev Belg Med Dent. 1994;49(1):9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balaram P, Sridhar H, Rajkumar T, Vaccarella S, Herrero R, Nandakumar A, Ravichandran K, Ramdas K, Sankaranarayanan R, Gajalakshmi V, Muñoz N, Franceschi S. Oral cancer in southern India: the influence of smoking, drinking, paan-chewing and oral hygiene. Int J Cancer. 2002;98(3):440–445. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain N, Mitra D, Ashok KP, Dundappa J, Soni S, Ahmed S. Oral hygiene-awareness and practice among patients attending OPD at Vyas Dental College and Hospital, Jodhpur. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16(4):524–528. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.106894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muhammad S, Lawal MT. Oral hygiene and the use of plants. Sci Res Essays. 2010;5(14):1788–1795. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen F, He BC, Yan LJ, Qiu Y, Lin LS, Cai L. Influence of oral hygiene and its interaction with standard of education on the risk of oral cancer in women who neither smoked nor drank alcohol: a hospital-based, case-control study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;55(3):260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2016.11.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeng X-T, Leng W-D, Zhang C, Liu J, Cao S-Y, Huang W. Meta-analysis on the association between toothbrushing and head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(5):446–451. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.02.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen F, He B-C, Yan L-J, Qiu Y, Lin L-S, Cai L. Influence of oral hygiene and its interaction with standard of education on the risk of oral cancer in women who neither smoked nor drank alcohol: a hospital-based, case-control study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;55(3):260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2016.11.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang JS, Lo H-I, Wong T-Y, Huang C-C, Lee W-T, Tsai S-T, Chen KC, Yen CJ, Wu YH, Hsueh WT, Yang MW, Wu SY, Chang KY, Chang JY, Ou CY, Wang YH, Weng YL, Yang HC, Wang FT, Lin CL, Huang JS, Hsiao JR. Investigating the association between oral hygiene and head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2013;49(10):1010–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Güneri P, Cankaya H, Yavuzer A, Güneri EA, Erişen L, Ozkul D, et al. Primary oral cancer in a Turkish population sample: association with sociodemographic features, smoking, alcohol, diet and dentition. Oral Oncol. 2005;41(10):1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talamini R, Vaccarella S, Barbone F, Tavani A, La Vecchia C, Herrero R, et al. Oral hygiene, dentition, sexual habits and risk of oral cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;83(9):1238–1242. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawakita D, Lee YA, Li Q, Chen Y, Chen CJ, Hsu WL, Lou PJ, Zhu C, Pan J, Shen H, Ma H, Cai L, He B, Wang Y, Zhou X, Ji Q, Zhou B, Wu W, Ma J, Boffetta P, Zhang ZF, Dai M, Hashibe M. Impact of oral hygiene on head and neck cancer risk in a Chinese population. Head Neck. 2017;39(12):2549–2557. doi: 10.1002/hed.24929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franco EL, Kowalski LP, Oliveira BV, Curado MP, Pereira RN, Silva ME, Fava AS, Torloni H. Risk factors for oral cancer in Brazil: a case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1989;43(6):992–1000. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawakita D, Amy Lee Y, Li Q, Chen Y, Chen C, Hsu W, et al (2017) Impact of oral hygiene on head and neck cancer risk in a Chinese population. Head Neck [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Hashim D, Sartori S, Brennan P, Curado MP, Wünsch-Filho V, Divaris K, Olshan AF, Zevallos JP, Winn DM, Franceschi S, Castellsagué X, Lissowska J, Rudnai P, Matsuo K, Morgenstern H, Chen C, Vaughan TL, Hofmann JN, D'Souza G, Haddad RI, Wu H, Lee YC, Hashibe M, Vecchia CL, Boffetta P. The role of oral hygiene in head and neck cancer: results from International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology (INHANCE) consortium. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2016;27(8):1619–1625. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai S-T, Wong T-Y, Ou C-Y, Fang S-Y, Chen K-C, Hsiao J-R, Huang CC, Lee WT, Lo HI, Huang JS, Wu JL, Yen CJ, Hsueh WT, Wu YH, Yang MW, Lin FC, Chang JY, Chang KY, Wu SY, Liao HC, Lin CL, Wang YH, Weng YL, Yang HC, Chang JS. The interplay between alcohol consumption, oral hygiene, ALDH2 and ADH1B in the risk of head and neck cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(10):2424–2436. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marques LA, Eluf-Neto J, Figueiredo RAO, de Góis-Filho JF, Kowalski LP, de Carvalho MB, et al. Oral health, hygiene practices and oral cancer. Rev Saude Publica. 2008;42(3):471–479. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102008000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garrote LF, Herrero R, Reyes RM, Vaccarella S, Anta JL, Ferbeye L, et al. Risk factors for cancer of the oral cavity and oro-pharynx in Cuba. Br J Cancer. 2001;85(1):46–54. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahrens W, Pohlabeln H, Foraita R, Nelis M, Lagiou P, Lagiou A, Bouchardy C, Slamova A, Schejbalova M, Merletti F, Richiardi L, Kjaerheim K, Agudo A, Castellsague X, Macfarlane TV, Macfarlane GJ, Lee YCA, Talamini R, Barzan L, Canova C, Simonato L, Thomson P, McKinney PA, McMahon AD, Znaor A, Healy CM, McCartan BE, Metspalu A, Marron M, Hashibe M, Conway DI, Brennan P. Oral health, dental care and mouthwash associated with upper aerodigestive tract cancer risk in Europe: the ARCAGE study. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(6):616–625. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato F, Oze I, Kawakita D, Yamamoto N, Ito H, Hosono S, Suzuki T, Kawase T, Furue H, Watanabe M, Hatooka S, Yatabe Y, Hasegawa Y, Shinoda M, Ueda M, Tajima K, Tanaka H, Matsuo K. Inverse association between toothbrushing and upper aerodigestive tract cancer risk in a Japanese population. Head Neck. 2011;33(11):1628–1637. doi: 10.1002/hed.21649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altini M, Peters E, Hille JJ (1989) The causation of oral precancer and cancer. J Dent Assoc South Afr Tydskr Van Tandheelkd Ver Van Suid-Afr (Suppl 1):6–10 [PubMed]

- 31.Young TB, Ford CN, Brandenburg JH. An epidemiologic study of oral cancer in a statewide network. Am J Otolaryngol. 1986;7(3):200–208. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(86)80007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thacker KK, Kaste LM, Homsi KD, LeHew CW. An assessment of oral cancer curricula in dental hygiene programmes: implications for cancer control. Int J Dent Hyg. 2016;14(4):307–313. doi: 10.1111/idh.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maier H, Zöller J, Herrmann A, Kreiss M, Heller WD. Dental status and oral hygiene in patients with head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol—Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 1993;108(6):655–661. doi: 10.1177/019459989310800606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van den Berg AD, Palmer NOA. An investigation of West Sussex general dental practitioners’ awareness, attitudes and adherence to NICE dental recall guidelines. Prim Dent Care J Fac Gen Dent Pract UK. 2012;19(1):11–22. doi: 10.1308/135576112798990755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laprise C, Shahul HP, Madathil SA, Thekkepurakkal AS, Castonguay G, Varghese I, Shiraz S, Allison P, Schlecht NF, Rousseau MC, Franco EL, Nicolau B. Periodontal diseases and risk of oral cancer in Southern India: Results from the HeNCe Life study. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(7):1512–1519. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dholam KP, Chouksey GC. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx in patients aged 18-45 years: a case-control study to evaluate the risk factors with emphasis on stress, diet, oral hygiene, and family history. Indian J Cancer. 2016;53(2):244–251. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.197725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laprise C, Shahul HP, Madathil SA, Thekkepurakkal AS, Castonguay G, Varghese I, Shiraz S, Allison P, Schlecht NF, Rousseau MC, Franco EL, Nicolau B. Periodontal diseases and risk of oral cancer in Southern India: results from the HeNCe Life study. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(7):1512–1519. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenquist K. Risk factors in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a population-based case-control study in southern Sweden. Swed Dent J Suppl. 2005;179:1–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Divaris K, Olshan AF, Smith J, Bell ME, Weissler MC, Funkhouser WK, Bradshaw PT. Oral health and risk for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: the Carolina Head and Neck Cancer Study. Cancer Causes Control CCC. 2010;21(4):567–575. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9486-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sham AS, Cheung LK, Jin LJ, Corbet EF. The effects of tobacco use on oral health. Hong Kong Med J. 2003;9(4):271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gillison ML. Current topics in the epidemiology of oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. Head Neck. 2007;29(8):779–792. doi: 10.1002/hed.20573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maier H, Zöller J, Herrmann A, Kreiss M, Heller WD. Dental status and oral hygiene in patients with head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;108(6):655–661. doi: 10.1177/019459989310800606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Friedlander AH, Marder SR, Pisegna JR, Yagiela JA. Alcohol abuse and dependence: psychopathology, medical management and dental implications. J Am Dent Assoc 1939. 2003;134(6):731–740. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maier H, Zöller J, Herrmann A, Kreiss M, Heller W-D (1993) Dental status and oral hygiene in patients with head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Neck Surg [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov 15]; Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/019459989310800606 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Wu PC, Pang SW, Chan KW, Lai CL. Statistical and pathological analysis of oral tumors in the Hong Kong Chinese. J Oral Pathol. 1986;15(2):98–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1986.tb00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Axelsson P, Paulander J, Lindhe J. Relationship between smoking and dental status in 35-, 50-, 65-, and 75-year-old individuals. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25(4):297–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirsch JM, Livian G, Edward S, Noren JG. Tobacco habits among teenagers in the city of Göteborg, Sweden, and possible association with dental caries. Swed Dent J. 1991;15(3):117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carossa S, Pera P, Doglio P, Lombardo S, Colagrande P, Brussino L, Rolla G, Bucca C. Oral nitric oxide during plaque deposition. Eur J Clin Investig. 2001;31(10):876–879. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krishna Rao SV, Mejia G, Roberts-Thomson K, Logan R. Epidemiology of oral cancer in Asia in the past decade--an update (2000-2012) Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(10):5567–5577. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.10.5567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mirvish SS. Experimental evidence for inhibition of N-nitroso compound formation as a factor in the negative correlation between vitamin C consumption and the incidence of certain cancers. Cancer Res. 1994;54(7 Suppl):1948s–1951s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krishna Rao SV, Mejia G, Roberts-Thomson K, Logan R. Epidemiology of oral cancer in Asia in the past decade—an update (2000–2012) Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2013;14(10):5567–5577. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.10.5567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adewole RA. Alcohol, smoking and oral cancer. A 10-year retrospective study at Base Hospital, Yaba. West Afr J Med. 2002;21(2):142–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet Lond Engl. 2005;366(9499):1809–1820. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67728-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kabat GC, Hebert JR, Wynder EL. Risk factors for oral cancer in women. Cancer Res. 1989;49(10):2803–2806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang R-S, Hu X-Y, Gu W-J, Hu Z, Wei B. Tooth loss and risk of head and neck cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang J, He B, Chen F, Liu F, Yan L, Hu Z, Lin L, He F, Cai L. Association between oral hygiene, chronic diseases, and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2015;49(8):688–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moergel M, Kämmerer P, Kasaj A, Armouti E, Alshihri A, Weyer V, al-Nawas B. Chronic periodontitis and its possible association with oral squamous cell carcinoma—a retrospective case control study. Head Face Med. 2013;9:39. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sadighi Shamami M, Sadighi Shamami M, Amini S. Periodontal disease and tooth loss as risks for cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2011;4(4):189–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calmels S, Ohshima H, Henry Y, Bartsch H. Characterization of bacterial cytochrome cd(1)-nitrite reductase as one enzyme responsible for catalysis of nitrosation of secondary amines. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17(3):533–536. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eisenbrand G, Spiegelhalder B, Preussmann R. Nitrate and nitrite in saliva. Oncology. 1980;37(4):227–231. doi: 10.1159/000225441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Selya AS, Rose JS, Dierker L, Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ. Evaluating the mutual pathways among electronic cigarette use, conventional smoking and nicotine dependence. Addict Abingdon Engl 2017 25; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Hoffmann D, Hoffmann I, El-Bayoumy K. The less harmful cigarette: a controversial issue. A tribute to Ernst L. Wynder. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14(7):767–790. doi: 10.1021/tx000260u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pöschl G, Seitz HK. Alcohol and cancer. Alcohol Alcohol Oxf Oxfs. 2004;39(3):155–165. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meurman JH. Infectious and dietary risk factors of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(6):411–413. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meurman JH, Uittamo J. Oral micro-organisms in the etiology of cancer. Acta Odontol Scand. 2008;66(6):321–326. doi: 10.1080/00016350802446527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Homann N, Tillonen J, Rintamäki H, Salaspuro M, Lindqvist C, Meurman JH. Poor dental status increases acetaldehyde production from ethanol in saliva: a possible link to increased oral cancer risk among heavy drinkers. Oral Oncol. 2001;37(2):153–158. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gupta B, Johnson NW. Emerging and established global life-style risk factors for cancer of the upper aero-digestive tract. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(15):5983–5991. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.15.5983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Khyani IAM, Qureshi MA, Mirza T, Farooq MU. Detection of interleukins-6 and 8 in saliva as potential biomarkers of oral pre-malignant lesion and oral carcinoma: a breakthrough in salivary diagnostics in Pakistan. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2017;30(3):817–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Davies R, Bedi R, Scully C. ABC of oral health. Oral health care for patients with special needs. BMJ. 2000;321(7259):495–498. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7259.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Najeeb T. Clinicopathological presentation of tongue cancers and early cancer treatment. J Coll Physicians Surg—Pak JCPSP. 2006;16(3):179–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Davies R, Bedi R, Scully C. Oral health care for patients with special needs. BMJ. 2000;321(7259):495–498. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7259.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sanjaya PR, Gokul S, Gururaj Patil B, Raju R. Candida in oral pre-cancer and oral cancer. Med Hypotheses. 2011;77(6):1125–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alnuaimi AD, Wiesenfeld D, O’Brien-Simpson NM, Reynolds EC, McCullough MJ. Oral Candida colonization in oral cancer patients and its relationship with traditional risk factors of oral cancer: a matched case-control study. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(2):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Inaba H, Sugita H, Kuboniwa M, Iwai S, Hamada M, Noda T, Morisaki I, Lamont RJ, Amano A. Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma through induction of proMMP9 and its activation. Cell Microbiol. 2014;16(1):131–145. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Griffen AL, Becker MR, Lyons SR, Moeschberger ML, Leys EJ. Prevalence of Porphyromonas gingivalis and periodontal health status. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36(11):3239–3242. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3239-3242.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Meurman JH, Bascones-Martinez A. Are oral and dental diseases linked to cancer? Oral Dis. 2011;17(8):779–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Galvão-Moreira LV, da Cruz MCFN. Oral microbiome, periodontitis and risk of head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2016;53:17–19. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Groeger S, Domann E, Gonzales JR, Chakraborty T, Meyle J. B7-H1 and B7-DC receptors of oral squamous carcinoma cells are upregulated by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Immunobiology. 2011;216(12):1302–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marshall JR, Boyle P. Nutrition and oral cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 1996;7(1):101–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00115642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Erisen L, Basut O, Tezel I, Onart S, Arat M, Hizalan I, et al. Regional epidemiological features of lip, oral cavity, and oropharyngeal cancer. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol Off Organ Int Soc Environ Toxicol Cancer. 1996;15(2–4):225–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.P MJ and B. Nutrition and oral cancer. - PubMed—NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8850439

- 82.Dhar PK, Rao TR, Sreekumaran Nair N, Mohan S, Chandra S, Bhat KR, Rao K. Identification of risk factors for specific subsites within the oraland oropharyngeal region--a study of 647 cancer patients. Indian J Cancer. 2000;37(2-3):114–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Marshall JR, Boyle P. Nutrition and oral cancer. Cancer Causes Control CCC. 1996;7(1):101–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00115642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dhar PK, Rao TR, Sreekumaran Nair N, Mohan S, Chandra S, Bhat KR, Rao K. Identification of risk factors for specific subsites within the oral and oropharyngeal region—a study of 647 cancer patients. Indian J Cancer. 2000;37(2–3):114–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oji C, Chukwuneke F. Poor oral hygiene may be the sole cause of oral cancer. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2012;11(4):379–383. doi: 10.1007/s12663-012-0359-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Scully C, Bedi R. Ethnicity and oral cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2000;1(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Purushothaman, Roshni A retrospective study on etiological factors, patient characteristics and prescription pattern of oral carcinoma in a tertiary care hospital. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2015;8(5):160–162. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Subapriya R, Thangavelu A, Mathavan B, Ramachandran CR, Nagini S. Assessment of risk factors for oral squamous cell carcinoma in Chidambaram, Southern India: a case-control study. Eur J Cancer Prev Off J Eur Cancer Prev Organ ECP. 2007;16(3):251–256. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000228402.53106.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wu JF, Lin LS, Chen F, Liu FQ, Huang JF, Yan LJ, Liu FP, Qiu Y, Zheng XY, Cai L, He BC. A case-control study: association between oral hygiene and oral cancer in non-smoking and non-drinking women. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2017;51(8):675–679. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Winn DM, Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK, Austin DF, Greenberg RS, Preston-Martin S, Schoenberg JB, Fraumeni JF Jr Mouthwash use and oral conditions in the risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer. Cancer Res. 1991;51(11):3044–3047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Marshall JR, Graham S, Haughey BP, Shedd D, O’Shea R, Brasure J, et al. Smoking, alcohol, dentition and diet in the epidemiology of oral cancer. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1992;28B(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(92)90005-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dawes C. Why does supragingival calculus form preferentially on the lingual surface of the 6 lower anterior teeth? J Can Dent Assoc. 2006;72(10):923–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gupta et al (2017) Associations between oral hygiene habits, diet, tobacco and alcohol and risk of oral cancer: a case–control study from India Cancer Epidemiology 51 7–148 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 94.Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) 2016-17 revealed decreased prevalence of tobacco among young India [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 29]. Available from: http://www.biospectrumindia.com/news/59/9056/global-adult-tobacco-survey-gats-2016-17-revealed-decreased-prevalence-of-tobacco-among-young-india-.html

- 95.NOHP. www.nohp.org.in

- 96.Kujan O, Glenny A-M, Duxbury J, Thakker N, Sloan P. Evaluation of screening strategies for improving oral cancer mortality: a Cochrane systematic review. J Dent Educ. 2005;69(2):255–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Maurizio SJ, Eckart AL. A case study associated with oropharyngeal cancer. J Dent Hyg JDH. 2010;84(4):170–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.LD. [Epidemiology of oral cancer]. - PubMed—NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17546894

- 99.Sankaranarayanan R, Ramadas K, Thomas G, Muwonge R, Thara S, Mathew B, Rajan B. Effect of screening on oral cancer mortality in Kerala, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2005;365(9475):1927–1933. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66658-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Awan KH, Hussain QA, Patil S, Maralingannavar M. Assessing the risk of oral cancer associated with Gutka and other smokeless tobacco products: a case-control study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2016;17(9):740–744. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Huang C-C, Ou C-Y, Lee W-T, Hsiao J-R, Tsai S-T, Wang J-D. Life expectancy and expected years of life lost to oral cancer in Taiwan: a nation-wide analysis of 22,024 cases followed for 10 years. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(4):349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]