Abstract

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is a highly pervasive and dynamic modification found on eukaryotic RNA. Despite the failure to comprehend the true regulatory potential of this epitranscriptomic mark for decades, our knowledge of m6A has rapidly expanded in recent years. The modification has now been functionally linked to all stages of mRNA metabolism and demonstrated to regulate a variety of biological processes. Furthermore, m6A has been identified on transcripts encoded by a wide range of viruses. Studies to investigate m6A function in viral-host interactions have highlighted distinct roles indicating widespread regulatory control over viral life cycles. As a result, unveiling the true influence of m6A modification could revolutionise our comprehension of the regulatory mechanisms controlling viral replication. This article is part of a Special Issue entitled: mRNA modifications in gene expression control edited by Dr. Soller Matthias and Dr. Fray Rupert.

Keywords: m6A, Viral replication, Epitranscriptomics, RNA modification, Post-transcriptional gene regulation, Virus-host interactions

Highlights

-

•

m6A methylation is functionally linked to all stages of mRNA metabolism and regulates a variety of biological processes.

-

•

m6A methylation marks both the genomic RNA and mRNAs of multiple viruses.

-

•

m6A methylation plays a significant role in modulating the replication of many viruses.

1. Introduction

Although the internal modification of RNA residues in mammalian cells was first identified over 40 years ago, recent technological advances are only now beginning to unravel the functional importance of these changes in widespread physiological processes [1]. While over 100 distinct modifications comprise the epitranscriptome, most are constrained to noncoding RNAs such as tRNAs, rRNAs and snRNAs. However, the most prevalent internal modification of messenger RNAs (mRNAs), m6A, decorates the transcriptome to bring about profound changes in mRNA biology [[2], [3], [4]]. For several decades, m6A has been known to mark both the genomic RNA and mRNAs of multiple viruses although the precise functional importance of m6A in the life cycles of these viruses is still relatively unknown [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]]. However, in the last few years, several publications have suggested this modification plays a significant and tantalising role in modulating viral replication.

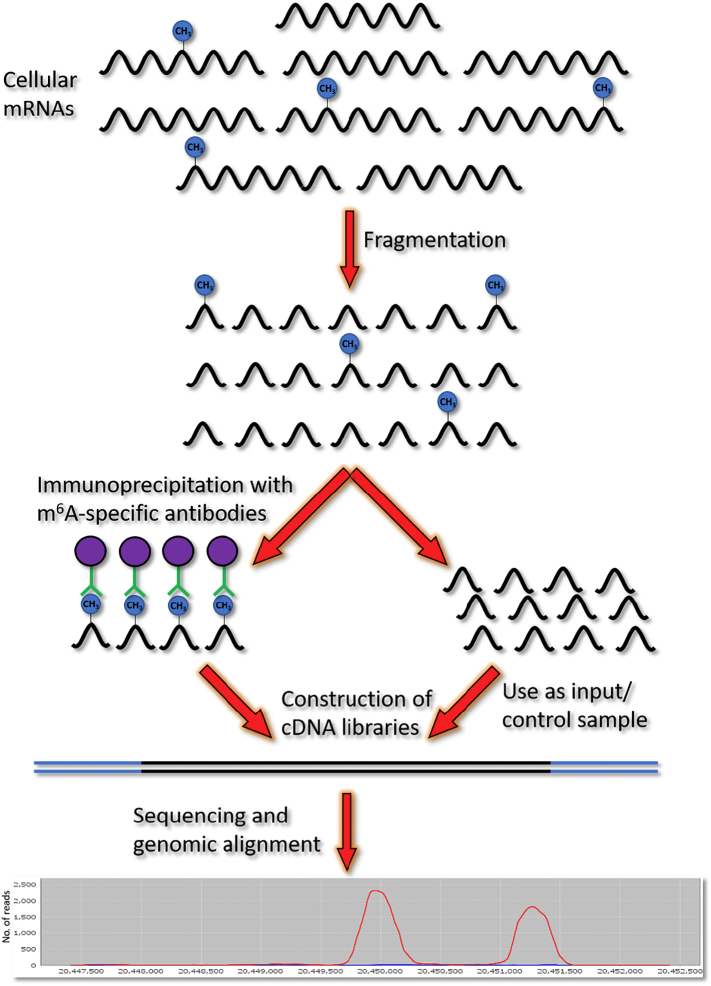

m6A was originally identified on cellular mRNAs at a prevalence of approximately three modifications per transcript [1]. However, early technologies reliant on the quantification of m6A in RNA lysates could not map individual m6A sites to specific transcripts and were unable to determine the true variability of m6A content across cellular mRNAs. Consequently, the development of a novel methylated RNA immunoprecipitation-sequencing (MeRIP-seq or m6A-seq) method for mapping of the m6A methylome in 2012 was a huge breakthrough in the study of the epitranscriptome and reignited interest in RNA modifications (Fig. 1). In recent years, MeRIP-seq and subsequent enhanced versions of the technique have been harnessed to divulge crucial insight into the topology of m6A in the cellular transcriptome [12,13]. Some mRNAs, especially those of housekeeping genes, have been found to contain no m6A while others contain many sites of methylation. Furthermore, m6A is clustered in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons [14]. Together, these insights into the unequal distribution of m6A on cellular transcripts allude to fundamental regulatory roles for this post-transcriptional modification in mRNA biology.

Fig. 1.

MeRIP-seq. The general procedure for MeRIP-seq involves the shearing of poly(A)+-selected mRNAs into 100–200 nt fragments followed by immunoprecipitation using m6A-specific antibodies attached to magnetic beads. The antibodies recognise N6-methylation but are therefore unable to distinguish m6A from the related RNA modification 2-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am). Immunoprecipitated RNA fragments are reverse transcribed, used to construct cDNA libraries and subjected to deep sequencing. Reads are then mapped to specific transcripts and 100–200 nt peaks, containing sites of m6A methylation, are called using bioinformatic detection algorithms. A portion of the non-precipitated RNA is used as the input sample.

2. The m6A machinery

2.1. Readers, writers and erasers

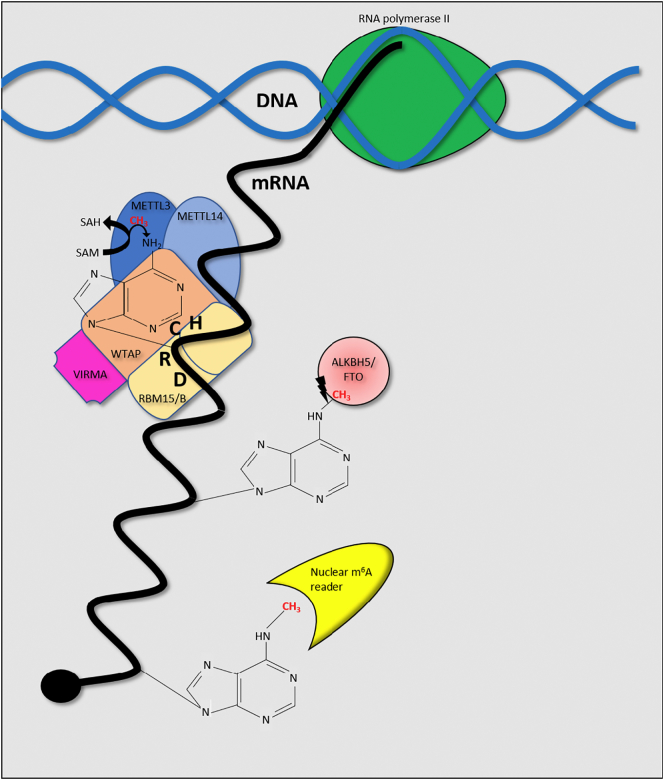

The reversible addition and removal of m6A upon cellular mRNAs is thought to be dynamically regulated by m6A writers and erasers allowing rapid adjustment of mRNA fate and thus regulatory control over various physiological processes (Fig. 2). However, the reversibility of m6A and wider RNA modifications is disputed by some groups which claim that significant and widespread demethylation does not occur in most cell types [15]. Similarly, although m6A has often been suggested to be added in a co-transcriptional manner, METTL3, METTL14 and ALKBH5 are all detectable among both nuclear and cytoplasmic cellular fractions [[16], [17], [18]]. Furthermore, m6A is found in the RNA of cytoplasmically-replicating viruses suggesting that post-transcriptional addition of m6A may also take place [18].

Fig. 2.

Dynamics of m6A. m6A is thought to be added to mRNAs at DRACH consensus sites. A methyl group is donated to the adenine base through the hydrolysis of S-adenosylmethionine to S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) by the methyltransferase complex, which contains a number of proteins crucial for efficient localisation and catalytic activity. Removal of the modification is undertaken by the m6A erasers ALKBH5 and FTO while recognition of m6A is carried out by m6A readers.

The deposition of m6A is catalysed by a large heteromultimeric methyltransferase complex or m6A writer complex, within which methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) is the catalytically active subunit and transfers a methyl group to adenosine residues through its S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) activity [[19], [20], [21]]. Using its adaptor protein methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14), which adopts a structural role essential for recognition of the RNA substrate, METTL3 deposits m6A on cellular transcripts at the preferred DR(m6A)CH (D = A, G or U; R = A or G; H = A, C or U) consensus sequence [13,[22], [23], [24]]. Wilms Tumour 1 associated protein (WTAP) is responsible for the localisation of the METTL3-METTL14 heterodimer to nuclear speckles; whereas interaction partners RBM15 and RBM15B are proposed to regulate the selective distribution of m6A to only a proportion of total transcriptomic DRACH sites [25,26]. Finally, KIAA1429 is suspected to act as protein scaffold maintaining the structural integrity of the m6A methyltransferase complex, but it has also recently been suggested to mediate the preferential enrichment of m6A in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons [27,28]. The deletion of any of these components of the m6A writer complex leads to a profound loss of m6A methylation on cellular transcripts, emphasising the necessity for each subunit in efficient control of m6A dynamics [21,25,27,29]. However, the additional proteins ZC3H13 and HAKAI have recently been found to comprise the m6A methyltransferase complex indicating that additional factors regulate the activity and selectivity of m6A methylation [28,[30], [31], [32], [33]]. To date, two m6A erasers have been proposed to revert m6A to adenosine residues and facilitate the dynamicity of the modification, α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase alkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5) and fat mass obesity protein (FTO). Only subtle changes in m6A content have been observed in ALKBH5-depleted cells and knockout mice are mostly normal apart from impaired fertility; however, it is possible that the demethylase acts on only a fraction of specific m6A sites in specific sequence or structural contexts [34]. Although some evidence suggests FTO instead demethylates m6Am, a related RNA modification adjacent to the m7G 5′ cap structure on approximately 35% of cellular mRNAs, the extent to which the demethylase targets m6A remains unclear [35,36]. Nevertheless, the deletion of both proteins increases global m6A/m content indicating these erasers contribute additional molecular fine-tuning to the regulation of mRNA biology [[34], [35], [36]].

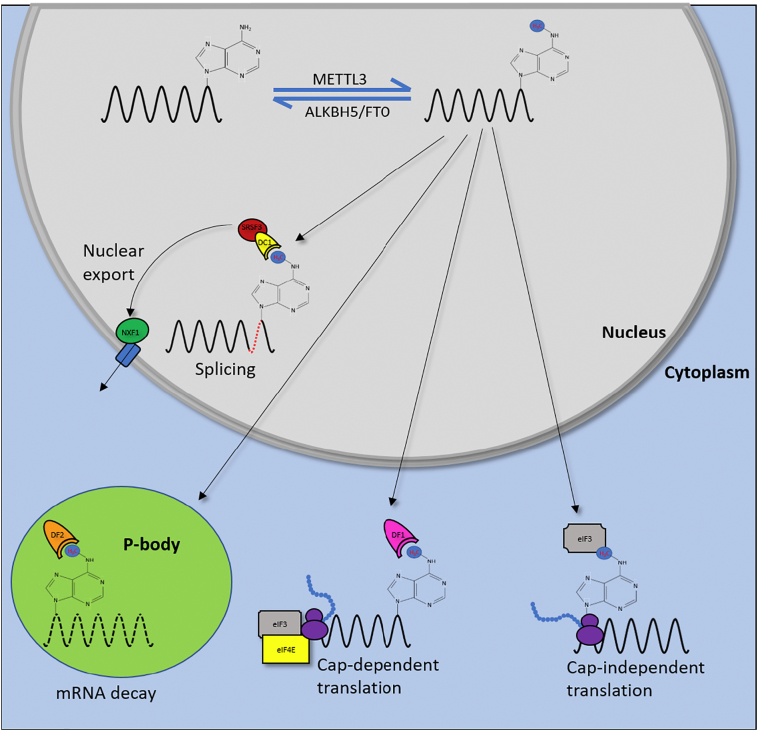

m6A exerts its influence over mRNAs in cis by recruiting RNA binding proteins, known as m6A readers, which recognise the site of modification and direct the methylated transcript towards distinct biological fates (Fig. 3). The best characterised among this group are the YT521-B homology (YTH) domain containing proteins including YTHDF1 (DF1), YTHDF2 (DF2) and YTHDF3 (DF3), which reside in the cytoplasm, and YTHDC1 (DC1) which adopts a nuclear localisation [37,38]. The final YTH protein is YTHDC2, however this protein is poorly characterised, unrelated to the other members of its family and further work is required to determine whether DC2 targets m6A. The YTH RNA-binding motif contains an aromatic cage comprised of three tryptophan residues which can specifically bind to the methyl group through hydrophobic interactions [39]. m6A also reduces base pair stability and is found in regions with reduced RNA structure; though importantly, a recent study has demonstrated that m6A can stabilise regions of RNA under certain structural contexts [40]. It is suggested that m6A can permit RNA unfolding and improve the accessibility of certain RNA binding proteins to their target sites. As a result, proteins which exploit this ‘m6A switch’ mechanism such as HNRNPC and HNRNPG have also been suggested as m6A readers despite the indirect nature of their interaction [41,42]. However, recently a new type of m6A reader protein was described which utilises a common RNA binding motif, the KH domain, in cooperation with flanking regions to selectively bind methylated adenosines [43]. The amounting evidence that a myriad of m6A readers exist suggests that m6A has evolved as an integral cellular mechanism that permits widespread regulatory control over gene expression.

Fig. 3.

Biological functions of m6A. Following the dynamic m6A-modification of mRNAs in the nucleus through the actions of the methyltransferase complex and m6A erasers, the methylation site is bound by m6A readers such as DC1, DF1–3 and eIF3 in both the cytoplasm and nucleus. Depending on the context of the m6A residue within a transcript, the fate of the mRNA may be diverted towards splicing, export, translation or decay.

2.2. Functions of m6A

The life of an mRNA includes processing, nuclear export, translation and decay. The earliest evidence that m6A plays a regulatory role in this biological cycle arises during splicing. In one mechanism, the reduction in base pair stability associated with an m6A residue improves the accessibility of HNRNPC and HNRNPG to their respective U-rich and purine-rich binding sites, facilitating the alternative splicing of target mRNAs [41,42]. Furthermore, the depletion of a proposed m6A reader, HNRNPA2B1 has been suggested to phenocopy the effect of METTL3 depletion on the alternative splicing of certain primary microRNAs [44]. Recent studies indicate this protein also utilises an m6A switch mechanism, thus the m6A-dependent binding of HNRNPA2B1 to pre-mRNAs could similarly regulate their processing [45]. Finally, functional studies into DC1 have identified that the nuclear YTH protein facilitates the subcellular localisation of the pre-mRNA splicing factor SRSF3 to nuclear speckles; but repels SRSF10, leading to specific exon-inclusion patterns [46,47]. Furthermore, multiple bodies of evidence suggest DC1 suppresses the recognition of a splice site in the Drosophila Sxl transcript, through the binding of an m6A site, to control sex determination [[48], [49], [50]]. Finally, a recent report has demonstrated that the majority of m6A peaks upon newly transcribed mRNAs lie within introns and correlate with reduced splicing efficiency [16]. In addition, m6A sites were also enriched around 5′ splice junctions; therefore, through the deployment of its reader proteins, m6A influences the alternative splicing of thousands of exons.

Recent studies involving DC1 and the m6A writer complex have further expanded the known functions of m6A to involve the regulation of mRNA export. DC1 facilitates the RNA-binding of both the adaptor protein SRSF3 and the major mRNA export receptor NFX1, which in turn drives the nuclear export of the methylated transcript [47]. Accordingly, depletion of DC1 results in increased nuclear residence times of modified mRNAs, independent of splicing. Thus, m6A could act as a non-canonical nuclear export signal to be decoded by DC1, which in turn delivers the methylated transcript to NFX1.

Once in the cytoplasm, m6A residues have also been proposed to enhance the translational efficiency of certain transcripts using eIF4E cap-dependent or cap-independent mechanisms. In the former method, DF1 binds 3′ UTR m6A and interacts with the 5′ UTR-associated eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3) to promote translation; perhaps through the stabilisation of the 5′-3′ looping mechanism observed during canonical translation initiation [3]. Early research into DF1–3 analysed heterologously expressed DF proteins and identified distinct functions for each YTH m6A reader. However, DF1–3 show nearly identical overlap with m6A sites and recent studies examining endogenous DF proteins suggest these m6A readers all promote translation [21,51,52]. Further study is required to determine whether the DF proteins behave redundantly. While the YTH proteins can promote translation through association with 3′ UTR-m6A, m6A-crosslinking assays have also shown that eIF3 is able to directly bind m6A in the 5′ UTRs of cellular transcripts using a multi-domain interface [4]. This leads to recruitment of the 43S pre-initiation complex, independent of the eIF4E cap-binding protein, promoting a unique, non-canonical form of m6A-driven translation initiation. This surrogate mechanism may be particularly important under cellular stress where eIF4E activity is hindered. Reinforcing this hypothesis, m6A increases at the 5′ UTRs of cellular transcripts in response to heat shock suggesting this modification may be used to bypass the dependency on a cap binding protein in the translation of mRNAs [53].

An early study into the function of the YTH proteins found that DF2 directs methylated-transcripts towards RNA decay. Accordingly, in cells where DF2 is depleted, its targets showed elevated half-lives [2]. The protein is proposed to bind m6A through its C-terminal YTH domain and then relocalise methylated transcripts to P-bodies for degradation through interactions at its N-terminal low-complexity region. However, given that mass spectrometry has shown that none of the DF proteins are enriched in P-bodies this interaction may be transient [2,54]. Additional research has provided further insight into this process whereby, prior to translocation of m6A-methylated transcript, mRNAs are deadenylated through interactions between DF2 and members of the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex [55]. Importantly, this study found that all DF proteins interact with the CCR4-NOT complex reinforcing evidence that these m6A-readers behave redundantly [18,52].

3. m6A in viral infections

Although there is much ground to cover in the elucidation of m6A function, major developments in the field of epitranscriptomics now permit the study of RNA modification during viral life cycles. Currently, only limited evidence has been gathered in viruses (Table 1). Most of these reports have involved the depletion of the m6A machinery followed by assessment of any associated changes in viral replication. However, these changes could be indirect due to alterations in the fate of cellular RNAs rather than viral transcripts. As a result, some groups have specifically mutated sites of m6A in viral transcripts to elucidate the function of the modification at certain loci. Nevertheless, all studies into the function of m6A in viral life cycles suggest epitranscriptomics has the potential to profoundly change our understanding of virus-host interactions.

Table 1.

List of viruses in which m6A has been functionally investigated through depletion or overexpression of components of the m6A machinery.

| Virus | Phenotype of writer depletion | Phenotype of eraser depletion | Phenotype of reader depletion | Phenotype of reader overexpression | Specific function of m6A | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 | Antiviral (METTL3; METTL14) | Proviral (ALKBH5) | – | – | Nuclear export | [56] |

| – | – | Antiviral (DF2) | Proviral (DF1–3) | mRNA abundance | [51] | |

| Antiviral (METTL3; METTL14) | Proviral (FTO; ALKBH5) | Proviral (DF1–3) | Antiviral (DF1–3) | Reverse transcription | [57] | |

| HCV | Proviral (METTL3; METTL14) | Antiviral (FTO) | Proviral (DF1–3) | – | Virion packaging | [58] |

| ZIKV | Proviral (METTL3; METTL14) | Antiviral (FTO; ALKBH5) | Proviral (DF1–3) | Antiviral (DF1–3) | – | [18] |

| IAV | Antiviral (METTL3) | – | – | Proviral (DF2) | mRNA abundance | [59] |

| KSHV | Antivirala (METTL3) | Provirala (FTO) | – | – | ORF50 pre-mRNA splicing | [60] |

| – | – | Proviralb (DF2) | Antiviralb (DF2) | – | [61] | |

| Provirala and antiviralb (METTL3) | – | Provirala and antiviralb (DF2) | – | – | [62] | |

| SV40 | Antiviral (METTL3) | – | Antiviral (DF2) | Proviral (DF2, DF3) | Nuclear export, Translation | [63] |

|

HBV |

Proviral and antiviral (METTL3 & METTL14) | Proviral and antiviral (ALKBH5; FTO) | Proviral and antiviral (DF2, DF3) | – | mRNA abundance, reverse transcription | [64] |

| AMV | – | Antiviral (ALKBH9B) | – | – | Interaction with viral coat protein | [65] |

B-cell line.

Endothelial cell line.

3.1. m6A in HIV-1 infection

During HIV-1 replication, viral mRNAs are subjected to both cap-dependent and independent forms of translation, a non-canonical form of nuclear export reliant on the HIV-1 protein Rev and extensive alternative splicing [[66], [67], [68]]. Given the known functions of m6A in the control of these processes, it is conceivable that the modification plays crucial roles in the epitranscriptomic regulation of HIV-1 gene expression.

In 2016, three studies were conducted investigating the role of m6A in HIV-1 infection; all using MeRIP-seq or the enhanced m6A mapping technology PA- m6A-seq to identify specific sites of m6A methylation on HIV-1 RNA [51,56,57]. Furthermore, two of these studies performed cross-linking immunoprecipitation (CLIP) assays to examine the binding sites of the DF proteins [51,57]. Lichinchi and colleagues identified 14 distinct methylation peaks in the 5′ and 3′ UTRs, coding sequences and splicing regulatory sequences, suggesting a variety of functions for m6A in HIV-1 genomic RNA (gRNA). All three studies reported shared 3′ UTR m6A clusters in the 3′ 1.4 kb of the 9.2 kb HIV-1 RNA genome. However, Kennedy and colleagues reported between zero and two further 3′ UTR m6A clusters in three HIV-1 isolates while Tirumuru et al. only identified one additional 5′ UTR m6A peak. Much of the variation between these studies likely arises from differences in bioinformatic methods of calling m6A peaks or alternatively due to the use of different HIV-1 isolates in varying cell types. In the former case, implementation of a consistent and effective method for identifying m6A sites, of which many are being developed, will dissolve these mapping incongruities in future studies [69]. Nevertheless, all three studies agree on the presence of m6A at the 3′ end of HIV-1 gRNA demonstrating indisputably the epitranscriptomic modification of the HIV-1 RNA genome.

To address the role of m6A in HIV-1 infection, two of the studies modified expression levels of m6A writers, readers and erasers in order to observe any associated changes in viral replication efficiency. Lichinchi et al. carried out shRNA-mediate depletion of METTL3, METTL14 and ALKBH5, then quantified RNA levels of the HIV-1 GP120 envelope glycoprotein and immunoblotted for the viral capsid protein p24, 72 h post-infection [56]. Knockdown of METTL3 and METTL14 decreased GP120 and p24 levels and accordingly an additive effect was identified for depletion of both writers. Conversely, a prominent increase in GP120 and p24 was seen in ALKBH5-depleted cells. In agreement with these results, Tirumuru and colleagues also depleted METTL3, METTL14, FTO and ALKBH5 finding a decrease in structural polyprotein precursor p55 Gag and p24 protein levels associated with knockdown of components of the m6A writer complex and the opposite effect for depletion of the demethylases [57]. Together, these studies suggest m6A positively regulates HIV-1 replication.

Harnessing an alternative approach to interrogate m6A function during HIV-1 infection, Kennedy and colleagues overexpressed the reader proteins DF1–3. They observed enhanced expression of the HIV-1 mRNAs Nef, Tat and Rev in addition to increased protein levels of p55 Gag, p24 and Nef [51]. In contrast, CRISPR-Cas-mediated deletion of YTHDF2 in HIV-1-infected CD4+ T cells was associated with a significant decline in p24 and Nef protein levels, supporting the hypothesis that m6A positively regulates HIV-1 replication. However, Tirumuru et al. observed contradictory results associated with modulation of DF1–3 expression. Overexpression of these m6A readers in HeLa cells inhibited HIV-1 infection by 10-fold and led to substantial downregulation of Gag protein; while a 4–14-fold increase in HIV-1 infectivity was observed following DF1–3 depletion [57]. These observations were corroborated in a CD4+ T-cell line and primary CD4+ T-cells. Further examination found that overexpression of DF1–3 led to a decrease in late reverse transcription products while their depletion reversed this effect, suggesting that m6A inhibits HIV-1 reverse transcription. In turn, this increase or decrease in reverse transcription products was positively correlated with changes in the expression gag mRNA and therefore HIV-1 gene expression. The authors of Kennedy et al. have since suggested the use of a modified HIV-1 strain by the Tirumuru and colleagues, containing a firefly luciferase HIV-1 reporter to measure viral infection, as a possible source for the divergent results. They suggest that pronounced sites of m6A modification in firefly luciferase mRNA may affect how the DF proteins influence HIV-1 replication [70]. Nevertheless, more recent evidence from Tirumuru and colleagues using wild type virus suggests their previous observations were not affected by methylation of firefly luciferase RNA. Furthermore, they identified that DF1–3 bind preferentially to two 5′ UTR sites in HIV-1 gRNA to reduce levels of viral gRNA and both early and late reverse transcription (RT) products [71]. In addition, the authors demonstrate an RNA-dependent interaction between DF1–3 and HIV-1 Gag but not p24. Thus, despite some differences, these studies demonstrate unequivocally that the m6A machinery plays profound roles in HIV-1 replication.

To assess the precise function of four m6A peaks mapped to the 3′ 1.4 kb of the HIV-1 NL4–3 genome, Kennedy and colleagues transfected HEK 293T cells with two Renilla Luciferase (RLuc)-based indicator plasmids containing either two or four of these putative m6A clusters [51]. Interestingly, these putative m6A clusters in the 3′ 1.4 kb of the HIV-1 genome mostly localised to the 3′ UTR in their corresponding viral mRNAs. The two plasmids were transfected in either wild type or mutant form where all DRACH consensus sites within the putative m6A regions were mutated to prevent methylation. Both plasmids containing wild type HIV-1 sequences expressed significantly higher RLuc mRNA and protein compared to their respective m6A-deficient forms. However, the level of enhancement was equivalent at both RNA and protein levels, suggesting that 3′ UTR m6A increases the steady state RNA levels of HIV-1 transcripts without influencing translation. In addition, artificial tethering of DF1–3 to the 3′ UTR of an RLuc indicator plasmid phenocopied this effect by increasing RLuc expression. Together, these results suggest that the DF proteins bind m6A residues within the 3′ UTR of HIV-1 transcripts and enhance expression of viral mRNAs in cis.

To tether a specific functional role to an m6A site discovered through MeRIP-seq, Lichinchi and colleagues examined an m6A peak which localised to stem loop IIB of the Rev response element (RRE). Binding of Rev protein to its RRE facilitates the nuclear export of viral mRNAs and is therefore a pivotal step in HIV-1 replication. Using m6A-sensitive and insensitive primers, the presence of two m6A sites at nucleotides 7877 and 7883 was confirmed within this region [56]. To identify whether the m6A-modification of these sites affects the affinity of Rev for its response element, Lichinchi and colleagues mutated these residues to prevent methylation. No significant effect on viral replication or nuclear export was associated with mutation of A7877. However, a striking decrease in both viral replication and RNA export was observed when m6A was abrogated at A7883. Furthermore, comparison of this position in 2501 HIV-isolates identified a mutation rate of just 0.28%; far lower than the frequencies associated with other adenosine nucleotides in stem loop IIB. Previous in vitro structural studies using NMR have demonstrated that A7883 bulges out of the stem region of the RRE and associates with Rev at position W45 [72]. However, depletion of METTL3 and METTL14 also reduced nuclear export of viral RNAs while ALKBH5 knockdown produced the opposite effect. Taken together, these results not only suggest that residue A7883 is critical for the Rev-RRE interaction and nuclear export of HIV-1 RNA, but additionally that this adenosine nucleotide must be m6A-modified. As a result, Lichinchi and colleagues provide a compelling example of the importance of m6A in viral-host interactions. Importantly however, neither Kennedy et al. nor Tirumuru et al. identified this RRE-located m6A peak in their MeRIP-seq data sets. As a result, further epitranscriptomic characterisation of HIV-1 gRNA is needed to fully understand the regulatory influence of m6A in HIV-1 replication.

3.2. m6A in flaviviruses

The investigation of m6A in HIV-1 infection was followed by two publications in late 2016, providing unexpected evidence of m6A in the positive sense, single-stranded RNA genomes of cytoplasmically-replicating flaviviruses. Although the m6A methyltransferase complex and ALKBH5 have been previously described as confined to the nucleus, both studies immunoblotted against METTL3, METTL14 and ALKBH5 in both nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of mock and flavivirus-infected cells. They identified all three proteins in both fractions, suggesting m6A writers and erasers can enter the cytoplasm where they facilitate the methylation and demethylation of flaviviral RNAs [18,58].

Gokhale and colleagues carried out MeRIP-seq to map the m6A landscape in Hepatitis C virus (HCV), identifying 19 peaks in the total 9.6 kb RNA genome. PAR-CLIP mapping of FLAG-tagged DF1–3 identified 42 binding sites; only 50% of which overlapped with regions of m6A reported by MeRIP-seq [58]. Although other studies have indicated that the YTHDF proteins bind almost all m6A sites, this discrepancy can be partially attributed to the binding of these proteins to non-methylated target sites [38]. To identify any conservation in the m6A landscape between flaviviruses, Gokhale and colleagues performed MeRIP-seq on the RNA genomes of Dengue, yellow fever, West Nile and two isolates of Zika virus (ZIKV). Interestingly, a fraction of the mapped m6A sites localised to similar regions among all the viruses, including the NS3 and NS5 genes, which may suggest a conserved role for m6A in their post-transcriptional regulation. Lichinchi et al. identified 12 m6A peaks in the full length 10.8 kb ZIKV RNA genome through MeRIP-seq [18]. Comparison of these putative m6A sites with four additional ZIKV strains demonstrated a high degree of sequence similarity indicating the m6A landscape is conserved in this virus. Furthermore, the identification of these m6A clusters in the NS3 and NS5 genes in both studies demonstrates conclusively the m6A-modification of flaviviral RNA.

In a similar method of investigation to those carried out in the HIV-1 studies, both Lichinchi et al. and Gokhale et al. depleted the cellular m6A machinery and screened for associated changes during flaviviral infection. Depletion of METTL3 and METTL14 by Gokhale and colleagues increased extracellular HCV RNA levels and infectious virion production, whereas knockdown of FTO had the opposite effect and reduction of ALKBH5 expression did not affect viral titre [58]. However, the use of a Gaussia-luciferase reporter virus to assess HCV RNA replication found no significant change in luciferase levels upon depletion of the m6A machinery, suggesting that m6A instead restricts the production or release of infectious virions. In agreement with these results, shRNA-mediated knockdown of METTL3 and METTL14 in ZIKV-infected HEK293T cells by Lichinchi et al. increased viral titre and ZIKV RNA levels, but also enhanced the expression of ZIKV envelope protein [18]. In contrast however, depletion of ALKBH5 or FTO decreased viral titre, ZIKV RNA expression and levels of envelope protein. In both studies, these results were validated by overexpressing these components of the m6A machinery and observing the reverse effects to those seen for depletion. Excluding ALKBH5 knockdown in HCV-infected cells, the results of the two papers demonstrate the negative regulation of flavivirus life cycles by the m6A landscape. It remains unclear why these viruses would retain m6A if it negatively impacted their life cycles given that consensus sites could be quickly lost through selection. Perhaps m6A positively regulates these viruses at certain stages of their replication or, as suggested in both reports, the modification facilitates escape from host antiviral immune responses. Indeed, the m6A modification of several in vitro synthesised RNAs suppresses recognition by the host pattern recognition receptors, TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and RIG-1 [73,74].

Next, DF1–3 were depleted to identify whether these readers mediate the negative regulation of ZIKV and HCV RNA by m6A. In both cases, knockdown of DF1–3 increased levels of extracellular viral RNA [18]. Furthermore, in ZIKV-infected cells, these observations were corroborated by DF1–3 overexpression which reduced extracellular viral RNA levels. The studies also demonstrated the discriminatory binding of YTH proteins to HCV and ZIKV RNA by immunoprecipitation of FLAG-tagged DF proteins followed by qRT-PCR. Finally, Gokhale and colleagues demonstrated the redistribution of all three DF proteins to cytoplasmic sites of HCV virion assembly, known as lipid droplets. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the modulation of RNA levels in HCV and ZIKV is functionally linked to DF binding of m6A-methylated viral RNA.

To interpret the functional relevance of a specific m6A cluster in the HCV RNA genome, Gokhale and others selected one region in the E1 gene which they had identified as bound by all three DF proteins and m6A-modified through their previous mapping experiments. Within this location, a cluster of four potential m6A sites were mutated to abolish the potential for N6-methylation without affecting the encoded amino acid sequence [58]. Electroporation of m6A-deficient HCV RNA into Huh7 cells resulted in three-fold higher HCV virion production compared with control HCV RNA. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that E1-mutated HCV RNA was bound more efficiently by HCV core protein, enhancing its packaging into nascent virions. Thus, Gokhale et al. demonstrated a specific mechanism for m6A-mediated regulation of HCV viral particle production.

3.3. m6A and influenza A

Influenza A virus (IAV) contains a segmented, negative sense, single-stranded RNA genome and replicates in the nucleus. Several decades ago, the presence of approximately 24 m6A-modified residues were identified on IAV mRNAs with eight sites concentrated onto the haemagglutinin (HA) mRNA segment; encoding a major viral envelope protein [11,75]. However, at the time, these sites of modification could not be accurately mapped and thus m6A function could not be elucidated. In a recent study, Courtney et al. mapped the topology of m6A on both the positive-cRNA and negative-vRNA segments of the IAV genome using PA-m6A-seq and PAR-CLIP for DF1–3. With some exceptions, the m6A peaks and DF binding sites were consistent [59]. The results identified an abundance of m6A in the genes encoding highly expressed structural proteins but far fewer sites of modification in mRNAs encoding the RNA polymerase subunits.

Utilising the same interrogatory methods employed for other viruses, Courtney and colleagues abrogated METTL3 expression through CRISPR/Cas-mediated knockout in the human lung epithelial cell line A549 [59]. Subsequent measurement of the IAV replicative ability in these METTL3-deficient cells identified an eight-fold decrease in the expression of viral structural proteins including NS1, NP and M2 compared to wild type virus. In addition, reduced viral titre and mRNA levels of NP and M2 were also reported in the METTL3 mutants. Supporting these results, overexpression of DF2 enhanced the expression of the same viral proteins and mRNAs, in addition to increasing viral titre roughly 5-fold. Surprisingly however, no significant effect could be detected for DF1 or DF3 overexpression, suggesting these m6A readers may not play a substantial role during IAV infection, at least in A549 cells. Nevertheless, together these data indicate that the m6A-modification of IAV RNA positively regulates the replication of the virus.

In agreement with previous studies, Courtney and others identified eight m6A sites in the HA cRNA segment and a further nine peaks in HA vRNA. To identify any regulatory importance for these m6A residues, Courtney and colleagues produced two IAV HA mutant viruses; each containing either a vRNA or cRNA segment in which the majority of m6A sites were silently mutated to prevent N6-methylation without affecting the amino acid sequence [59]. In cells infected with m6A-deficient virions, HA was specifically downregulated at both the protein and mRNA level without any effect on expression of other viral genes including NS1 and M2. Furthermore, these HA mutants displayed significantly attenuated pathogenicity in infected mice compared to their parental wild type highly pathogenic IAV strain. Thus, m6A plays a crucial role in modulating expression of HA and therefore IAV infectivity.

Employing a strategy absent from previous studies in viruses, Courtney et al. attempted to interpret how m6A positively regulates IAV by comparing the immune response to the m6A-depleted HA mutants and wild type virus. However, no difference was detected in the expression of various anti-viral innate immune response proteins including RIG-1, MGA5 and Interferon β suggesting m6A positively regulates IAV RNA levels through mechanisms other than downregulation of immune activity.

Given that the m6A enhances the expression of both splice variants of the NS1 and M2 genes at equal ratios and similarly increases mRNA and protein levels of IAV viral genes at identical proportions, Courtney and colleagues suggest the effects mediated by m6A do not affect splicing or translation [59]. Furthermore, m6A residues enhance the abundance of both IAV HA mRNA and vRNA; the latter of which is constrained to the nucleus until late in the viral life cycle where it is packaged into virions. Given this information, Courtney et al. suggest an m6A-mediated effect on RNA export is unlikely and instead the modification increases IAV RNA abundance through enhanced stability or replication.

3.4. m6A and KSHV

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated virus (KSHV) is a double stranded DNA virus associated with the endothelial tumour Kaposi's sarcoma and two lymphoproliferative disorders [76,77]. Like all herpesviruses, KSHV undergoes distinct latent and lytic life cycles. In the latent stage, KSHV is episomally maintained in the host nucleus and expresses only a few genes to sustain a state of dormancy. Upon reactivation from the latent phase, expression of ORF50, encoding the master regulator of lytic replication RTA, is sufficient to initiate a temporally regulated cascade of gene expression leading to the production of infectious virions [78].

To date, three independent studies have been published detailing the m6A-modification of both lytic and latent KSHV transcripts. Ye and colleagues conducted MeRIP followed by qPCR of viral transcripts to demonstrate the extensive m6A modification of the KSHV genome [60]. The abundance of lytic transcripts and their m6A content increased robustly following induction of various KSHV-infected cell lines with multiple different stimuli. Additionally, Tan and others identified numerous changes in the viral m6A landscape upon both infection of five cell lines with KSHV and following induction of lytic replication in two of these cell lines [61]. In all five latently-infected cell types, they found conserved m6A peaks in latent transcripts including LANA, vFLIP and vCyclin. Interestingly, these transcripts gained additional peaks when lytic replication was stimulated in the endothelial KiSLK and B-cell-derived TREX-BCBL1 cell lines. Furthermore, the studies identified numerous conserved and some cell type specific m6A peaks on viral lytic mRNAs following induction. Finally, Hesser and colleagues reported a 3-fold increase in cellular m6A content upon induction of iSLK.219 cells by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry [62]. They later attribute this change to the m6A-modification of the KSHV non-coding RNA PAN which is suggested to comprise more than 80% of nuclear polyA+ RNA levels during lytic reactivation [79,80]. In addition, MeRIP-seq was carried out to demonstrate that approximately one third of KSHV mRNAs become m6A methylated upon KSHV induction. Taken together, these studies suggest m6A might play a crucial role in both the establishment of KSHV infection and controlling the regulatory switch between lytic and latent KSHV replication programmes.

To assess whether modulation of m6A levels would affect KSHV lytic replication, Ye and colleagues performed lentiviral knockdowns of METTL3 and FTO in the KSHV-infected TREX-BCBL1 cell line and stimulated lytic gene expression [60]. METTL3-depletion reduced virion production and decreased both the mRNA and proteins levels of ORF50 and the early gene ORF57. Furthermore, addition of the drug 3-deazaadenosine (DAA), which inhibits SAM activity and thus the addition of m6A to RNA, abolished KSHV lytic replication. In contrast, FTO-depletion or addition of the FTO inhibitor meclofenamic acid (MA) enhanced the production of KSHV viral particles and expression of ORF50 and ORF57 [81]. Although these results suggest m6A positively regulates the production of KSHV virions, Tan and colleagues found that depletion of DF2 in KiSLK cells led to a four-fold increase in virion production alongside a two- to six-fold rise in expression of the viral mRNAs ORF50, ORF57, ORFK8 and ORF65 leading to concomitant increases in their protein levels while DF2 overexpression reversed these effects [61]. However, no consistent or significant effect was observed for overexpression of other YTH proteins which may be due to their lower expression levels relative to DF2. Tan and colleagues also showed that depletion of DF2 elevated the half-lives of lytic KSHV transcripts through actinomycin D treatment and confirmed a 1.5-fold increase in the half lives of LANA, ORF57, ORF59, ORFK8 and ORF65 by RT-qPCR. As a result, the authors suggest YTHDF2 may act as an antiviral cellular restriction factor by targeting KSHV transcripts for degradation in P-bodies or to proteins with decapping, deadenylation or exonuclease activity in a P-body independent mechanism.

Hesser and colleagues repeated the depletions of both METTL3 and the YTHDF proteins in both the iSLK.219 and TREX-BCBL1 cell lines and carried out a range of assays to determine the phenotypic effect on KSHV lytic replication [62]. Viral transfer assays, assessing the ability of GFP-expressing virions produced in endothelial cells to reinfect 293T cells, demonstrated that depletion of DF2 and METTL3 strikingly decreased infectious virion production. Additionally, while significant reductions in the abundance of the late viral transcript ORFK8.1 were only observed for knockdown of METTL3, depletion of DF2 reduced the levels of the immediate early, delayed early and late KSHV mRNAs ORF50, ORF37 and ORFK8.1 and also the RTA and ORF59 proteins. These observations may be the result of upstream alterations in the expression of early viral transcripts which in turn cause a reduction in the levels of mRNAs expressed later during KSHV reactivation. In agreement with Tan and colleagues, no significant or consistent effect could be observed for depletion of DF1 or DF3. Surprisingly however, when Hesser and colleagues repeated these assays in TREX-BCBL1 cells, METTL3 and DF2 depletion had no significant effect on infectious virion production nor ORF50 and ORF59 mRNA levels, but increased protein levels of RTA and ORF59 indicating that m6A restricts KSHV replication in these cells. As a result, the authors suggest that m6A could elicit both pro- and antiviral control over KSHV lytic replication depending on the host cell type. Conceivably, the differential methylation of DRACH sites, alternative recognition by m6A readers or the availability of certain host cell factors could contribute to the opposing functions of m6A observed in these cells. However, the observations of Hesser and colleagues are not fully consistent with those seen by the other two studies in the iSLK and TREX-BCBL1 cell lines. Consequently, the role of m6A in KSHV infection remains uncertain and future studies are required to resolve the outstanding discrepancies.

Given that m6A-abolition impaired the induction of the lytic transactivator RTA in TREX-BCBL1 cells and m6A has been functionally linked to splicing through DC1 recognition, Ye and colleagues investigated whether m6A might affect pre-mRNA splicing of ORF50 [46,60]. Induction of KSHV lytic replication increased both pre-mRNA and mRNA levels of ORF50, but in the presence of DAA, mRNA abundance significantly declined without significantly altering pre-mRNA levels. To show that m6A was important for this decrease in mRNA to pre-mRNA ratio, Ye and colleagues carried out MeRIP-seq to determine the m6A landscape of ORF50 mRNA, identifying 14 sites of methylation. Next, the ORF50 gene was cloned into a pCMV-myc plasmid and in vitro mutagenesis of the 14 methylation sites carried out to produce individual plasmids lacking a single ORF50 m6A site. The plasmids were transfected into HEK 293T cells to assess the effects on pre-mRNA splicing. Four of these plasmids, three of which lacked m6A in the single ORF50 intron and one of which was m6A-deficient at a site in exon 2, displayed significantly reduced ratios of mRNA to pre-mRNA suggesting that splicing had been impaired. Furthermore, coimmunoprecipitation and RNA immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that the m6A reader YTHDC1, SRSF3 and SRFS10 interact with each other and bind ORF50 mRNA. Finally, Ye and colleagues show that at these four site of modification within the ORF50 transcript, m6A regulates the association of the splicing factors SRSF3 and SRSF10 to control both exon inclusion and intron exclusion. Taken together, these results suggest m6A modulates alternative splicing within ORF50 pre-mRNA and thus regulates KSHV lytic replication.

3.5. m6A in SV40

Another dsDNA virus whose transcripts are subjected to m6A-methylation is SV40; a member of the polyomavirus family. Although the modification of SV40 mRNAs was elucidated several decades ago, the functional link between m6A methylation and viral replication has only recently been examined [5]. Tsai and others commenced by modifying expression of the m6A machinery to identify any associated changes in viral replication [63]. Overexpression of DF2 elevated expression of both the early large T antigen protein and the late structural protein VP1, while an increase in both the size and number of viral plaques were observed in viral plaque assays. Furthermore, a similar, but less profound effect was observed on overexpression of DF3. In contrast, CRISPR-Cas-mediated deletion of both DF2 and METTL3 reversed the effects seen for DF2 overexpression. Accordingly, these results suggest m6A positively regulates SV40 replication.

Consistent with strategies employed for previous viruses, Tsai and colleagues proceeded to map sites of m6A-modification within the SV40 genome through both PA-m6A-seq and PAR-CLIP for binding of DF2 and DF3 [63]. Although the binding sites identified through the two techniques were not identical, they were mostly overlapping; permitting the discovery of 13 m6A peaks within the SV40 genome including 11 in late region encoding structural proteins. Notably, nine of these peaks were detected in the VP1 gene which also forms the 3′ UTR of the transcripts VP2 and VP3.

To determine whether the enhancement of SV40 replication associated with modulating the m6A machinery resulted from changes to cellular or viral transcripts, Tsai and colleagues produced a hypomethylated SV40 mutant termed ‘VPm’ in which all 20 DRACH consensus sequences within the 11 putative m6A regions of late transcripts were disrupted [63]. PA-m6A-seq was used to demonstrate the complete abrogation of m6A at three locations and partial removal at a further six m6A sites in the VPm mutant. Next, Tsai et al. compared the replicative ability of VPm with wild type SV40 in three permissive cell lines; BSC40, CV-1 and Vero. A significant decrease in the expression of viral early and late proteins was observed, in combination with reduced plaque size, confirming that a reduction in m6A content on viral transcripts is responsible for impaired SV40 replication.

Given that SV40 undergoes a complex pattern of splicing and the nuclear reader DC1 has been reported to undertake m6A-directed splicing of cellular transcripts, Tsai and colleagues investigated whether VPm produced aberrant splicing patterns in late mRNAs through the RT-PCR of late transcripts. However, no significant difference in the expression pattern of SV40 transcript variants could be observed between cells infected by wild type and mutant viruses suggesting that m6A is not required for splicing of SV40 mRNAs.

To examine a specific role for m6A in the expression of late SV40 proteins, Tsai et al. produced constructs containing the VP1 gene derived from wild-type SV40 or VPm. When both constructs were transfected into HEK 293T cells, 10-fold lower VP1 protein levels were observed in cells expressing the hypomethylated VP1 transcript despite the lack of a significant change in mRNA abundance. However, comparing both cytosolic and nuclear fractions, a 2-fold decrease was identified in the cytosolic levels of the hypomethylated VP1 transcript suggesting m6A is important for the nuclear export of VP1 mRNA [63]. However, since this change cannot individually account for the 10-fold lower VP1 protein levels identified previously, Tsai et al. hypothesize that m6A primarily influences VP1 expression by enhancing its translation. Together, these results suggest m6A positively regulates SV40 replication through enhanced translation and export of viral late transcripts; providing yet another example of the regulatory importance of m6A in the life cycle of a virus. Supporting this conclusion, the addition of DAA profoundly reduces expression of SV40 late viral proteins; attesting to the potential for m6A as a molecular target in the treatment of viral infection [63].

3.6. m6A in HBV

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) is a dsDNA virus which replicates through the reverse transcription of an RNA intermediate known as pregenomic RNA (pgRNA). The majority of HBV pgRNA is translated into the viral protein while the remainder is encapsidated with core and pol subunits, followed by reverse transcription to produce mature capsids. A recent study described dual-functionality for m6A in the HBV life cycle [64]. Initially, Imam and colleagues demonstrated the m6A-modification of HBV RNA by performing meRIP followed by qRT-PCR of methylated RNA using primers specific to a 3′ UTR sequence shared by all HBV transcripts. Importantly, viral RNA was methylated in two HBV-infected cell lines and the liver tissues of patients with chronic hepatitis B. Furthermore, the pool of pgRNA which is destined for reverse transcription was also shown to be methylated by meRIP-RT-qPCR following isolation from core particles. Finally, pgRNA was enriched in DF2 and DF3 immunoprecipitates following transfection of HBV-infected HepAD38 cells with FLAG-tagged DF2 and DF3 providing further evidence of m6A-modified HBV RNA.

To determine whether m6A exerts any effect on the HBV life cycle, Imam et al. simultaneously depleted the methyltransferase components METTL3 and METTL14, in addition to the independent knockdown of the m6A erasers FTO and ALKBH5 [64]. The results showed that METTL3 and METTL14-depletion increased expression of the viral proteins HBs and Hbc, while the reverse effect was observed in cells lacking FTO or ALKBH5 expression. Furthermore, knockdown of the m6A readers DF2 and DF3 recapitulated the increase in viral protein expression observed for depletion of METTL3 and METTL14, suggesting that m6A negatively regulates expression of HBV proteins. Interestingly, an increase in expression of the pgRNA was also seen for DF2- and DF3-knockdown; suggesting that the decrease in HBV protein levels is due to diminished RNA abundance rather than reduced translation. Confirming this hypothesis, the group measured the stability of HBV transcripts by actinomycin D treatment in cells lacking METTL3 and METTL14 or DF2. They observed over a two-fold increase in the half-life of pgRNA following depletion of these m6A machinery components suggesting that m6A negatively affects the stability of HBV RNA. Interestingly however, the group also measured the effect of m6A on the reverse transcription of HBV pgRNA by measuring core-associated DNA levels in cells lacking METTL3 and METTL14 or FTO. Reverse transcription was significantly reduced in cells lacking METTL3 and METTL14, but enhanced in those lacking FTO. Taken together, these results suggest a dual-role for m6A in the HBV life cycle involving the destabilisation of HBV transcripts in conjunction with enhanced reverse transcription of HBV pgRNA.

To precisely locate sites of m6A within HBV RNA, Imam and colleagues performed m6A-seq on uninfected and HBV-expressing hepatocytes and identified a single m6A peak at position A1907 in the HBV genome; however, they did not investigate any changes in m6A content of cellular transcripts [64]. The identified m6A site falls within a 3′ epsilon stem loop present in all HBV transcripts; though importantly, pgRNA possesses this m6A residue in both its 5′ and 3′ epsilon stem loop. To specifically determine the function of these m6A sites, the group created three mutants deficient in m6A at one or both of the pgRNA stem loops. By assessing protein levels, RNA half-life and viral DNA synthesis in core particles, Imam and colleagues demonstrated that 3′ m6A-mutant pgRNA is more stable than its wild type counterpart while 5′ m6A-deficient pgRNA undergoes less efficient reverse transcription. Furthermore, the pgRNA lacking m6A within both epsilon stem loops displays both of these phenotypes, recapitulating the effect seen for depletion of METTL3 and METTL14. The A1907C mutation leads to a base pair mismatch within the epsilon stem loop structure, thus m6A-deficiency could lead to structural alterations which might explain the effects on RNA stability and reverse transcription. Importantly however, the restoration of base pairing with a compensatory mutation could not reverse the decrease in protein expression and enhanced reverse transcription. As a result, Imam and colleagues provide strong evidence that methylation of A1907 in HBV RNA affects the virus life cycle through the modulation RNA stability and reverse transcription.

3.7. m6A in a plant virus

To date, very few studies have been conducted regarding the function of m6A in plants and very little is known about the m6A machinery in these organisms. Despite this, a recent study has expanded the field of viral epitranscriptomics by providing the first evidence of a functional role for m6A in the regulation of a plant virus. Martínez-Pérez et al. identified a member of the AlkB family of demethylases, ALKBH9B, among a yeast two-hybrid screen for interaction partners of the multifunctional alfalfa mosaic virus (AMV) coat protein (CP) in Arabidopsis thaliana [65]. After validating this interaction, Martínez-Pérez and colleagues compared the infective ability of AMV in an ALKBH9B-deficient Arabidopsis stock to wild type plants. They found that both vRNA and CP levels were significantly reduced in the mutants compared to wild type plants following AMV inoculation suggesting that viral infection is attenuated. Intriguingly, fluorescence microscopy studies showed that ALKBH9B overlaps perfectly with SGS3, a component of siRNA bodies, and DCP1, a decapping enzyme in P-bodies, suggesting ALKLBH9B m6A activity might be linked to mechanisms of mRNA silencing and decay that are conserved among eukaryotes.

To determine whether ALKBH9B is indeed an m6A eraser, Martínez-Pérez et al. assessed the ability of GST-purified ALKBH9B to remove m6A from a methylated RNA oligonucleotide [65]. The RNA substrate was almost entirely demethylated by ALKBH9B confirming the protein as an m6A eraser. Given the link between m6A and AMV infection, Martínez-Pérez and colleagues mapped the m6A landscape in AMV by MeRIP-seq and identified six putative m6A sites. Furthermore, the ALKBH9B-depleted Arabidopsis stock displayed a 35% increase in m6A levels. Together, these results suggest that the RNA hypermethylation in ALKBH9B-mutants impairs AMV infection and thus m6A negatively regulates the virus life cycle. Importantly however, depletion of ALKBH9B did not potentiate infection by cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), another Arabidopsis pathogen, despite its m6A-modified RNA genome suggesting ALKBH9B does not regulate CMV infection. Notably, a lack of interaction between ALKBH9B and CMV CP was identified which may explain this finding. Nevertheless, this recent publication provides exciting evidence that m6A plays a fundamental regulatory function in the life cycles of plant viruses, attesting to the ubiquitous nature of the modification in the field of virology.

4. Changes in the cellular m6A landscape during viral infection

While the m6A-methylation of viral genomes clearly plays a crucial role in regulating viral infection, changes in the host m6A landscape represent another mechanism for potentiating viral-host interactions. Five of the studies discussed previously chose to investigate this fascinating hypothesis by mapping the m6A methylome in both uninfected and virally-infected host cells. In each case, a set of uniquely or differentially methylated transcripts were identified and subjected to gene ontology (GO) analysis to discover enriched pathways by functional clustering. Lichinchi and colleagues identified 56 transcripts uniquely methylated under HIV-1 infection, for which the most represented category was viral gene expression [56]. Indeed, 19 of the protein products of these cellular mRNAs had been previously linked to HIV replication; a subset of which interact directly with HIV viral components and undertake mostly proviral functions. However, an identical investigation by Tirumuru et al. found that transcripts which were differentially methylated upon HIV-1 infection were functionally clustered in broader cellular pathways such as immunity, metabolism and development [57]. Similarly, during ZIKV infection, Lichinchi and colleagues also identified immune-related genes as those most enriched among cellular transcripts containing de novo m6A peaks [18]. In addition, Tan and others found that transcripts involved in pathways associated with oncogenesis and KSHV latency programmes were most enriched among those subjected to differential methylation during KSHV infection [61]. Conceivably however, differentially methylated transcripts involved in KSHV lytic replication were most abundant when comparing cells undergoing latent and lytic infection programmes. In contrast, Hesser and colleagues found a striking 25% decrease in m6A content upon cellular transcripts during KSHV induction, but could not find any notable enrichments in GO analysis of these downregulated transcripts implying that viral transcripts are prioritised for methylation during reactivation. Nevertheless, taken together, these results strongly evidence the re-organisation of the host m6A landscape in order to modulate viral infection; however, it remains unclear whether these observations are due to the cell mounting an antiviral response, viral subversion of host cell machinery or a combination of both of these phenomena.

To identify any changes in the cellular topology of m6A in response to viral infection, several of these studies compared the preference in m6A consensus site between uninfected and infected conditions. In HIV-1, Lichinchi and colleagues identified a 5% increase in m6A-methylated MGACK (A/C-GAC-G/U) motifs during infection [56]. However, Tirumuru and others found only a minor 0.2–0.8% and 0.2–0.4% in RRACH and GGACU motifs respectively [57]. In ZIKV infection, cellular m6A levels increased in 5′ UTRs and coding sequences while correspondingly decreasing in 3′ UTRs and exon junctions [18]. In addition, comparison of consensus site usage in ZIKV-infected and uninfected cells showed a loss in m6A from GAC sites and a gain at AAC sites. Finally, in KSHV-infected cells, changes in m6A distribution differed with cell type and in response to both latent and lytic replication programmes [61]. Although Tan and colleagues suggested GGAC as the most frequently utilised m6A consensus site under uninfected, latently-infected and lytically-infected conditions they did not compare changes in m6A motif usage. Importantly however, they identified that few of the differentially m6A-modified transcripts were likely to be sites of m6Am suggesting a minimal effect for this related modification in initiating lytic replication. Together, these results suggest the cellular m6A landscape is dynamically regulated under viral infection, hinting towards the exciting possibility that the preferred consensus site of the m6A machinery may be altered in response to physiological conditions.

5. Concluding remarks and future perspectives

Although the m6A-modification of viral RNAs was first discovered several decades ago, the evidence gathered by just a small number of studies in the last two years has indicated that this ubiquitous and dynamic epitranscriptomic phenomenon likely plays widespread regulatory roles in a broad range of viruses. The development of precise methods for m6A mapping has established the nexus for systematically expanding our understanding of m6A function. Nevertheless, upgraded technologies permitting the direct sequencing of viral RNAs are now emerging which have the potential to abolish the difficulties and inaccuracies associated with current techniques [82]. Depletion of the host m6A machinery and abrogation of methylation at specific sites continue to be indispensable methods for determining m6A function in viral life cycles. However, the targeted methylation or demethylation of specific sites of modification, while technically challenging, would indisputably permit the elucidation of m6A function. Furthermore, the ability of m6A to positively regulate the replication of some viruses, while inhibiting others remains a key question that must now rise to the precipice for exploration. Similarly, it is unclear if changes in the host epitranscriptome, whether proviral or antiviral, play significant roles in modulating virus infection. The resolution of these outstanding questions will likely accelerate our understanding of m6A function in virus-host interactions and bring forth the coming enlightenment in viral epitranscriptomics.

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in parts by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/M006557/1), Medical Research Council (MR/R010145/1 and 95505168) and Worldwide Cancer Research (16-1025).

Footnotes

This article is part of a Special Issue entitled: mRNA modifications in gene expression control edited by Dr. Soller Matthias and Dr. Fray Rupert.

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in online version.

References

- 1.Desrosiers R., Friderici K., Rottman F. Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1974;71:3971–3975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X., Lu Z., Gomez A., Hon G.C., Yue Y., Han D., Fu Y., Parisien M., Dai Q., Jia G., Ren B., Pan T., He C. m(6)A-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505:117–120. doi: 10.1038/nature12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X., Zhao B.S., Roundtree I.A., Lu Z., Han D., Ma H., Weng X., Chen K., Shi H., He C. N6-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell. 2015;161:1388–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer K.D., Patil D.P., Zhou J., Zinoviev A., Skabkin M.A., Elemento O., Pestova T.V., Qian S.-B., Jaffrey S.R. 5′ UTR m6A promotes cap-independent translation. Cell. 2015;163:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canaani D., Kahana C., Lavi S., Groner Y. Identification and mapping of N6-methyladenosine containing sequences in Simian Virus 40 RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;6:2879–2899. doi: 10.1093/nar/6.8.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimock K., Stoltzfus C.M. Sequence specificity of internal methylation in B77 avian sarcoma virus RNA subunits. Biochemistry. 1977;16:471–478. doi: 10.1021/bi00622a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane S.E., Beemon K. Precise localization of m6A in Rous sarcoma virus RNA reveals clustering of methylation sites: implications for RNA processing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1985;5:2298–2306. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.9.2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss B., Gershowitz A., Stringer J.R., Holland L.E., Wagner E.K. 5′ terminal and internal methylated nucleosides in herpes and simplex virus type 1 mRNA. J. Virol. 1977;23:234–239. doi: 10.1128/jvi.23.2.234-239.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei C.M., Moss B. Methylated nucleotides block 5′-terminus of vaccinia virus messenger RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1975;72:318–322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.1.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sommer S., Salditt-Georgieff M., Bachenheimer S., Darnell J.E., Furuichi Y., Morgan M., Shatkin A.J. The methylation of adenovirus-specific nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1976;3:749–766. doi: 10.1093/nar/3.3.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krug R.M., Morgan M.A., Shatkin A.J. Influenza viral mRNA contains internal N6 methyladenosine and 5′ terminal 7 methylguanosine in cap structures. J. Virol. 1976;20:45–53. doi: 10.1128/jvi.20.1.45-53.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linder B., Grozhik A.V., Olarerin-George A.O., Meydan C., Mason C.E., Jaffrey S.R. Single-nucleotide-resolution mapping of m6A and m6Am throughout the transcriptome. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:767–772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dominissini D., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Schwartz S., Salmon-Divon M., Ungar L., Osenberg S., Cesarkas K., Jacob-Hirsch J., Amariglio N., Kupiec M. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer K.D., Saletore Y., Zumbo P., Elemento O., Mason C.E., Jaffrey S.R. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell. 2012;149:1635–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darnell R.R., Shengdong K.E., Darnell J.E. Pre-mRNA processing includes N6methylation of adenosine residues that are retained in mRNA exons and the fallacy of “RNA epigenetics”. RNA. 2018;24:262–267. doi: 10.1261/rna.065219.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louloupi A., Ntini E., Conrad T., Ørom U.A.V. Transient N-6-methyladenosine transcriptome sequencing reveals a regulatory role of m6A in splicing efficiency. Cell Rep. 2018;23:3429–3437. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ke S., Pandya-Jones A., Saito Y., Fak J.J., Vågbø C.B., Geula S., Hanna J.H., Black D.L., Darnell J.E., Darnell R.B. m6A mRNA modifications are deposited in nascent pre-mRNA and are not required for splicing but do specify cytoplasmic turnover. Genes Dev. 2017;31:990–1006. doi: 10.1101/gad.301036.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lichinchi G., Zhao B.S., Wu Y., Lu Z., Qin Y., He C., Rana T.M. Dynamics of human and viral RNA methylation during Zika virus infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:666–673. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bokar J.A., Shambaugh M.E., Polayes D., Matera A.G., Rottman F.M. Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. RNA. 1997;3:1233–1247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu J., Yue Y., Han D., Wang X., Fu Y., Zhang L., Jia G., Yu M., Lu Z., Deng X. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:93–95. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patil D.P., Chen C.-K., Pickering B.F., Chow A., Jackson C., Guttman M., Jaffrey S.R. m6A RNA methylation promotes XIST-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature. 2016;537:369–373. doi: 10.1038/nature19342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Śledź P., Jinek M. Structural insights into the molecular mechanism of the m(6)A writer complex. elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.18434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang P., Doxtader K.A., Nam Y. Structural basis for cooperative function of Mettl3 and Mettl14 methyltransferases. Mol. Cell. 2016;63:306–317. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X., Feng J., Xue Y., Guan Z., Zhang D., Liu Z., Gong Z., Wang Q., Huang J., Tang C., Zou T., Yin P. Structural basis of N6-adenosine methylation by the METTL3–METTL14 complex. Nature. 2016;534:575. doi: 10.1038/nature18298. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature18298#supplementary-information [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ping X.-L., Sun B.-F., Wang L., Xiao W., Yang X., Wang W.-J., Adhikari S., Shi Y., Lv Y., Chen Y.-S. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res. 2014;24:177–189. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horiuchi K., Kawamura T., Iwanari H., Ohashi R., Naito M., Kodama T., Hamakubo T. Identification of Wilms' tumor 1-associating protein complex and its role in alternative splicing and the cell cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:33292–33302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.500397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz S., Mumbach M.R., Jovanovic M., Wang T., Maciag K., Bushkin G.G., Mertins P., Ter-Ovanesyan D., Habib N., Cacchiarelli D. Perturbation of m6A writers reveals two distinct classes of mRNA methylation at internal and 5′ sites. Cell Rep. 2014;8:284–296. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yue Y., Liu J.J., Cui X., Cao J., Luo G., Zhang Z., Cheng T., Gao M., Shu X., Ma H., Wang F., Wang X., Shen B., Wang Y., Feng X., He C., Liu J.J. VIRMA mediates preferential m(6)A mRNA methylation in 3′UTR and near stop codon and associates with alternative polyadenylation. Cell Discov. 2018;4 doi: 10.1038/s41421-018-0019-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geula S., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Dominissini D., Mansour A.A., Kol N., Salmon-Divon M., Hershkovitz V., Peer E., Mor N., Manor Y.S. m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naïve pluripotency toward differentiation. Science (80-) 2015;347:1002–1006. doi: 10.1126/science.1261417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wen J., Lv R., Ma H., Shen H., He C., Wang J., Jiao F., Liu H., Yang P., Tan L., Lan F., Shi Y.G., Shi Y.G., Diao J. Zc3h13 regulates nuclear RNA m(6)A methylation and mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Mol. Cell. 2018;69:1028–1038.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo J., Tang H.-W., Li J., Perrimon N., Yan D. Xio is a component of the Drosophila sex determination pathway and RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:3674–3679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720945115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knuckles P., Lence T., Haussmann I.U., Jacob D., Kreim N., Carl S.H., Masiello I., Hares T., Villaseñor R., Hess D., Andrade-Navarro M.A., Biggiogera M., Helm M., Soller M., Bühler M. Zc3h13/Flacc is required for adenosine methylation by bridging the mRNA-binding factor Rbm15/Spenito to the m6A machinery component Wtap/Fl(2)d. Genes Dev. 2018;32:415–429. doi: 10.1101/gad.309146.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Růžička K., Zhang M., Campilho A., Bodi Z., Kashif M., Saleh M., Eeckhout D., El-Showk S., Li H., Zhong S., De Jaeger G., Mongan N.P., Hejátko J., Helariutta Y., Fray R.G. Identification of factors required for m6A mRNA methylation in Arabidopsis reveals a role for the conserved E3 ubiquitin ligase HAKAI. New Phytol. 2017;215:157–172. doi: 10.1111/nph.14586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng G., Dahl J.A., Niu Y., Fedorcsak P., Huang C.-M., Li C.J., Vågbø C.B., Shi Y., Wang W.-L., Song S.-H. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol. Cell. 2013;49:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jia G., Fu Y., Zhao X., Dai Q., Zheng G., Yang Y.Y.-G., Yi C., Lindahl T., Pan T., Yang Y.Y.-G. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:885–887. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mauer J., Luo X., Blanjoie A., Jiao X., Grozhik A.V., Patil D.P., Linder B., Pickering B.F., Vasseur J.-J., Chen Q., Gross S.S., Elemento O., Debart F., Kiledjian M., Jaffrey S.R. Reversible methylation of m6Am in the 5′ cap controls mRNA stability. Nature. 2016;541:371. doi: 10.1038/nature21022. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature21022#supplementary-information [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu C., Wang X., Liu K., Roundtree I.A., Tempel W., Li Y., Lu Z., He C., Min J. Structural basis for selective binding of m6A RNA by the YTHDC1 YTH domain. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:927. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1654. https://www.nature.com/articles/nchembio.1654#supplementary-information [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Z., Theler D., Kaminska K.H., Hiller M., de la Grange P., Pudimat R., Rafalska I., Heinrich B., Bujnicki J.M., Allain F.H., Stamm S. The YTH domain is a novel RNA binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:14701–14710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.104711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Theler D., Dominguez C., Blatter M., Boudet J., Allain F.H.T. Solution structure of the YTH domain in complex with N6-methyladenosine RNA: a reader of methylated RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:13911–13919. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu B., Merriman D.K., Choi S.H., Schumacher M.A., Plangger R., Kreutz C., Horner S.M., Meyer K.D., Al-Hashimi H.M. A potentially abundant junctional RNA motif stabilized by m6A and Mg2+ Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05243-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu N., Dai Q., Zheng G., He C., Parisien M., Pan T. N6-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature. 2015;518:560–564. doi: 10.1038/nature14234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu N., Zhou K.I., Parisien M., Dai Q., Diatchenko L., Pan T. N6-methyladenosine alters RNA structure to regulate binding of a low-complexity protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:6051–6063. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang H., Weng H., Sun W., Qin X., Shi H., Wu H., Zhao B.S., Mesquita A., Liu C., Yuan C.L., Hu Y.C., Hüttelmaier S., Skibbe J.R., Su R., Deng X., Dong L., Sun M., Li C., Nachtergaele S., Wang Y., Hu C., Ferchen K., Greis K.D., Jiang X., Wei M., Qu L., Guan J.L., He C., Yang J., Chen J. Author correction: recognition of RNA N6-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018;20:1. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0045-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alarcón C.R., Goodarzi H., Lee H., Liu X., Tavazoie S.S.F., Tavazoie S.S.F. HNRNPA2B1 is a mediator of m6A-dependent nuclear RNA processing events. Cell. 2015;162:1299–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu B., Su S., Patil D.P., Liu H., Gan J., Jaffrey S.R., Ma J. Molecular basis for the specific and multivariant recognitions of RNA substrates by human hnRNP A2/B1. Nat. Commun. 2018;9 doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02770-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiao W., Adhikari S., Dahal U., Chen Y.-S., Hao Y.-J., Sun B.-F., Sun H.-Y., Li A., Ping X.-L., Lai W.-Y. Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell. 2016;61:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roundtree I.A., Luo G.-Z., Zhang Z., Wang X., Zhou T., Cui Y., Sha J., Huang X., Guerrero L., Xie P., He E., Shen B., He C. YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N(6)-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.31311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lence T., Akhtar J., Bayer M., Schmid K., Spindler L., Ho C.H., Kreim N., Andrade-Navarro M.A., Poeck B., Helm M., Roignant J.Y. M6A modulates neuronal functions and sex determination in Drosophila. Nature. 2016;540:242–247. doi: 10.1038/nature20568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haussmann I.U., Bodi Z., Sanchez-Moran E., Mongan N.P., Archer N., Fray R.G., Soller M. M6A potentiates Sxl alternative pre-mRNA splicing for robust Drosophila sex determination. Nature. 2016;540:301–304. doi: 10.1038/nature20577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kan L., Grozhik A.V., Vedanayagam J., Patil D.P., Pang N., Lim K.S., Huang Y.C., Joseph B., Lin C.J., Despic V., Guo J., Yan D., Kondo S., Deng W.M., Dedon P.C., Jaffrey S.R., Lai E.C. The m6A pathway facilitates sex determination in Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1–16. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kennedy E.M., Bogerd H.P., Kornepati A.V.R., Kang D., Ghoshal D., Marshall J.B., Poling B.C., Tsai K., Gokhale N.S., Horner S.M., Cullen B.R. Posttranscriptional m6A editing of HIV-1 mRNAs enhances viral gene expression. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:675–685. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi H., Wang X., Lu Z., Zhao B.S., Ma H., Hsu P.J., Liu C., He C. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N6-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res. 2017;27:315. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.15. (https://www.nature.com/articles/cr201715#supplementary-information) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou J., Wan J., Gao X., Zhang X., Jaffrey S.R., Qian S.-B. Dynamic m6A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature. 2015;526:591. doi: 10.1038/nature15377. (https://www.nature.com/articles/nature15377#supplementary-information) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hubstenberger A., Courel M., Bénard M., Souquere S., Ernoult-Lange M., Chouaib R., Yi Z., Morlot J.-B., Munier A., Fradet M. P-body purification reveals the condensation of repressed mRNA regulons. Mol. Cell. 2017;68:144–157. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Du H., Zhao Y., He J., Zhang Y., Xi H., Liu M., Ma J., Wu L. YTHDF2 destabilizes m6A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4–NOT deadenylase complex. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12626. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12626. (https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms12626#supplementary-information) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lichinchi G., Gao S., Saletore Y., Gonzalez G.M., Bansal V., Wang Y., Mason C.E., Rana T.M. Dynamics of the human and viral m6A RNA methylomes during HIV-1 infection of T cells. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;1 doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tirumuru N., Zhao B.S., Lu W., Lu Z., He C., Wu L. N(6)-methyladenosine of HIV-1 RNA regulates viral infection and HIV-1 Gag protein expression. elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.15528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gokhale N.S., McIntyre A.B.R., McFadden M.J., Roder A.E., Kennedy E.M., Gandara J.A., Hopcraft S.E., Quicke K.M., Vazquez C., Willer J., Ilkayeva O.R., Law B.A., Holley C.L., Garcia-Blanco M.A., Evans M.J., Suthar M.S., Bradrick S.S., Mason C.E., Horner S.M. N6-methyladenosine in flaviviridae viral RNA genomes regulates infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;20:654–665. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]