Abstract

Introduction

Post-operative length of stay (LOS) after the arterial switch operation (ASO) is variable. The association between pre-operative non-invasive measures of ventricular function and post-operative course has not been well established. The aims of this study were to (1) evaluate the relationship between pre-operative non-invasive measures of ventricular function and post-operative LOS and (2) evaluate the change in ventricular function after ASO.

Methods

Data were reviewed in consecutive ASO patients between 2010 and 2016. The primary outcome was post-operative LOS. Echocardiograms obtained during the pre-operative period and at the time of discharge were retrospectively analyzed using speckle-tracking echocardiography. Pearson’s correlation between patient-specific, pre-operative, and echocardiographic data versus post-operative LOS was assessed.

Results

Fifty-two patients were included in analyses, 39 neonates and 13 infants. Left ventricular (LV) longitudinal strain correlated with post-operative LOS for infants age > 28 days (r = 0.62, p = 0.03), but not for neonates (r = 0.14, p = 0.40). Operative age (r = − 0.42, p = 0.003), weight at surgery (r = − 0.48, p ≤ 0.001), and cardiopulmonary bypass time (r = 0.30, p = 0.045) also correlated with post-operative LOS. Standard 2D measures of ventricular function did not correlate with post-operative LOS. LV ejection fraction and longitudinal strain worsened post-operatively.

Conclusion

Higher pre-operative LV longitudinal strain (representing worse LV function) is associated with increased post-operative LOS after ASO in infants > 28 days, but not in neonates. LV ejection fraction and longitudinal strain worsened after ASO. Future studies should assess the utility of performing STE in risk stratifying patients prior to ASO.

Keywords: Speckle-tracking echocardiography, Transposition of the great arteries, Congenital heart disease, Neonatal surgery

Introduction

The arterial switch operation (ASO) is the preferred surgical repair for neonates and infants with dextro-position of the great arteries (d-TGA) and double outlet right ventricle (DORV) with malposed great arteries [1]. Overall, long-term outcomes are improving [2]. However, there remains significant post-operative morbidity and mortality; most recent data report a perioperative mortality rate of 2.2–5.1% [3]. Patient factors have been identified that are associated with increased morbidity and mortality [4–9]. For patients undergoing late ASO, there are conflicting reports as to the utility of echocardiographic data to predict post-operative outcomes [10–13]. Anecdotal evidence suggests that patients with pre-operative ventricular dysfunction experience increased morbidity including prolonged length of stay (LOS) after ASO. However, the relationship between pre-operative ventricular function and post-operative morbidity has not been well established.

Speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE) is a non-invasive modality for the assessment of myocardial deformation. Reference ranges have been published for the pediatric population [14, 15], and STE has increasingly been applied in patients with congenital heart disease [16–18]. STE has several characteristics that make it appealing for evaluation of ventricular function in this patient population. Measures derived from STE have geometry independence, good reproducibility, and have been shown to be more sensitive to changes in systolic function than standard measures such as ejection fraction [19–22]. The purposes of this study are to (1) evaluate the relationship between pre-operative and post-operative non-invasive measures of ventricular function and post-operative LOS and (2) evaluate the change in ventricular function after ASO.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed identifying all patients who underwent ASO at the Medical University of South Carolina between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2016. Patients were excluded if they underwent ASO at > 90 days of life or if their echocardiogram images were not sufficient to permit STE analysis. The primary outcome was post-operative LOS. This study protocol was approved by the Medical University of South Carolina’s Institutional Review Board.

Echocardiographic Analysis

Clinical echocardiograms previously stored in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine format at 30 frames per second were analyzed on Xcelera (Philips, Andover, MA). The pre-operative echocardiogram was defined as the most recent echocardiogram prior to the surgical date. The post-operative echocardiogram was defined as the echocardiogram obtained prior to hospital discharge. A single blinded reviewer retrospectively analyzed all echocardiograms. Standard 2D measurements were performed in accordance with the recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography [23]. Left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction was calculated using the (5/6 × area × length) method. Right ventricular (RV) fractional area change was calculated as [(RV area diastole − RV area systole)/RV area diastole].

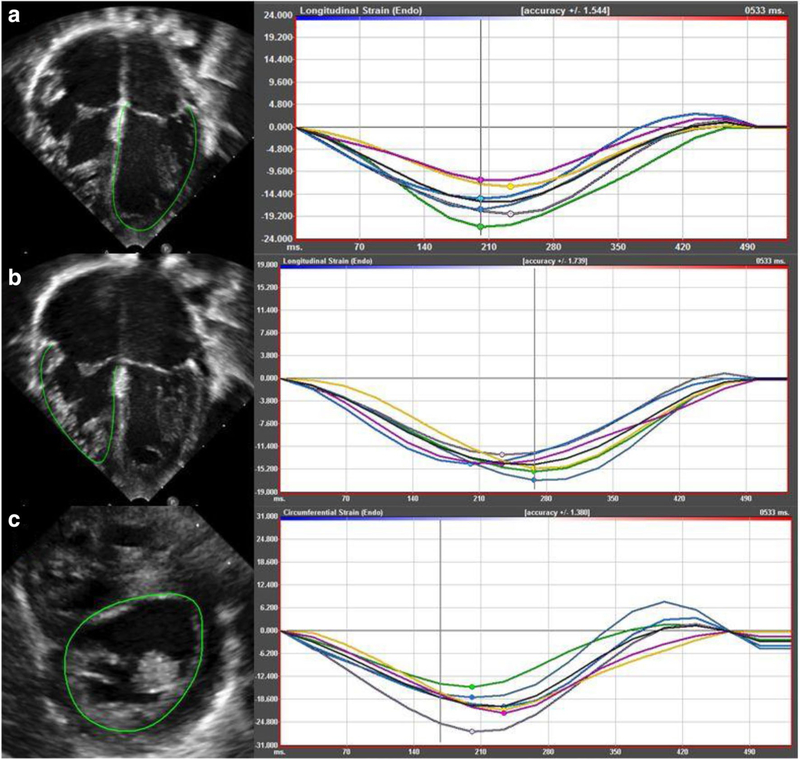

Speckle-tracking echocardiography was performed using vendor independent software, Cardiac Performance Analysis v3.0 (Tomtec Imaging Systems, Munich, Germany) on all echocardiograms. Longitudinal strain was obtained from an apical four chamber view. Circumferential strain was obtained from a parasternal short-axis view at the level of the papillary muscles or sub-valvular apparatus. In the absence of acceptable parasternal acoustic windows, circumferential strain was obtained from a subcostal short-axis view. The endocardial border was identified manually and automatically traced by the software throughout the cardiac cycle (Fig. 1). The ventricular myocardium was divided into six discrete segments. Segments that did not track the endocardium accurately were excluded. STE data were included if four out of six segments tracked appropriately. Longitudinal and circumferential strain represented an average of the included wall segments [22]. A more negative value for strain indicates better ventricular function.

Fig. 1.

Representation of STE with corresponding deformation curves: a analysis of LV longitudinal strain from apical four chamber view; b analysis of RV longitudinal strain from apical four chamber view; c analysis of LV circumferential strain from parasternal short-axis view

Statistical Analysis

Shapiro–Wilk test was utilized to analyze the distribution of data. Independent t-tests, Chi-square tests, and Mann–Whitney U tests were used to identify differences between neonates (age < 28 days) and infants (age ≥ 28 days). Paired t-tests or Wilcoxson signed rank tests were used to evaluate for changes in measures of ventricular function before and after ASO. We used Pearson’s correlation to assess relationship between LOS and echocardiographic measures of ventricular function. Log transformations were used to account for non-parametric distribution of data. Statistical significance was defined as p-value < 0.05. IBM SPSS Statistics software v 24 was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Sixty-nine patients underwent ASO at the Medical University of South Carolina between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2016. Two were excluded based on age > 90 days at time of surgery. Fifteen were excluded based on inadequate echocardiogram images. Fifty-two patients were included in analysis and patient characteristics are represented in Table 1. No patients died prior to hospital discharge. The underlying lesion varied. Thirty-two (62%) of patients had d-TGA with intact ventricular septum (IVS), 13 (25%) had d-TGA with ventricular septal defect (VSD), and 7 (13%) had DORV with malposed great arteries and d-TGA physiology.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Neonates (< 28 days) n = 39 |

Infants (≥ 28 days) n = 13 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 22 (56%) | 6 (46%) | |

| Operative weight (kg) | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 5.3 ± 2.1 | 0.009 |

| Height (cm) | 50.2 ± 2.4 | 60.0 ± 9.1 | 0.003 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 39 (38, 39) | 39 (36, 39) | 0.243 |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 0.020 |

| XCL time (min) | 110 (94, 150) | 156 (118, 175) | 0.016 |

| CPB time (min) | 225 (197, 271) | 261 (221, 288) | 0.136 |

| Days intubated | 5 (3, 8) | 2 (1, 11) | 0.149 |

| Post-op LOS (days) | 15 (11, 21) | 10 (6, 23) | 0.133 |

| Hospital LOS (days) | 23 (19, 27) | 10 (6, 49) | 0.038 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 72 ± 10 | 88 ± 13 | ≤ 0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 41 ± 9 | 53 ± 11 | ≤ 0.001 |

| RV fractional area change | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 0.30 ± 0.09 | 0.322 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 62 ± 8 | 63 ± 8 | 0.591 |

| LV longitudinal strain | − 14.5 (− 16.6, − 12.2) | − 17.6 (− 20.7, − 15.3) | 0.011 |

| RV longitudinal strain | − 14.5 ± 4.6 | − 14.9 ± 1.6 | 0.630 |

| LV circumferential strain | − 15.8 (− 18.0, − 14.6) | − 19.8 (− 21.4, − 16.3) | 0.024 |

Each value is expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range)

XCL aortic cross clamp, CPB cardiopulmonary bypass, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, RV right ventricle, LV left ventricle

Neonates Versus Infants

Of the 52 patients included in the study, 39 (75%) were neonates and 13 (25%) were infants. Neonates had a longer median hospital LOS at 23 days (IQR 19, 27) compared to infants who had a median hospital LOS at 10 days (IQR 6, 49). However, the difference in post-operative LOS was not statistically significant. Neonates had a higher birth weight (3.4 ± 0.5 kg) than infants (2.7 ± 0.8 kg), but infants had a higher operative weight (5.3 ± 2.1 kg) than neonates (3.4 ± 0.4 kg) at the time of surgery. Neonates had more days intubated (5 [IQR 3, 8]) than infants (2 [IQR 1, 11]) although this did not reach statistical significance. There was no difference in standard measures of ventricular function between neonates and infants. Neonates had worse LV longitudinal strain [− 14.5% (IQR − 16.6%, − 12.2%) vs. − 17.6% (IQR − 20.7%, − 15.3%)] and LV circumferential strain [− 15.8% (IQR − 18.0%, − 14.6%) vs − 19.9% (IQR − 21.4%, − 16.3%)] than infants.

Predictors of Post‑operative LOS

Among the full cohort, there was a weak correlation (r = 0.30, p = 0.04) between pre-operative LV longitudinal strain and post-operative LOS. We then evaluated this correlation for neonates and infants separately. For neonates, there was no correlation between pre-operative LV longitudinal strain and post-operative LOS (r = 0.14, p = 0.40) (Fig. 2). However there was a moderate correlation between pre-operative LV longitudinal strain and post-operative LOS in infants (r = 0.62, p = 0.03) (Fig. 3). Operative age (r = − 0.42, p = 0.003), weight at surgery (r = − 0.48, p ≤ 0.001), and cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) time (r = 0.30, p = 0.045) also correlated with post-operative LOS in the full cohort.

Fig. 2.

Neonates Pre-operative LV longitudinal strain on x-axis (more negative indicates better ventricular function), post-operative LOS on y-axis

Fig. 3.

Infants Pre-operative LV longitudinal strain on x-axis (more negative indicates better ventricular function), post-operative LOS on y-axis

Change in Ventricular Function after ASO

Table 2 demonstrates changes in ventricular function after ASO. LV ejection fraction decreased from pre-operative echo to post-operative echo (62 ± 8% to 58 ± 7%), p = 0.001. LV longitudinal strain likewise worsened from −15.3% (IQR − 18.3%, − 13.1%) to − 13.9% (IQR − 16.1%, − 12.6%), p = 0.007. End diastolic volume did not change. RV fractional area change increased from 0.28 ± 0.06 to 0.36 ± 0.09, p ≤ 0.001. There was no statistically significant change in RV longitudinal strain.

Table 2.

Change in non-invasive measures of function after ASO

| Pre-operative | Post-operative | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SBP (mmHg) | 76 ± 13 | 88 ± 15 | ≤ 0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 42 (37, 50) | 49 (42, 56) | 0.059 |

| EDV (mL) | 10.0 (7.3, 12.7) | 10.2 (7.8, 11.8) | 0.703 |

| RV fractional area change | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 0.36 ± 0.09 | ≤ 0.001 |

| LV ejection fraction (as %) | 62 ± 8 | 58 ± 7 | 0.001 |

| LV longitudinal strain | − 15.3 (− 18.3, − 13.1) | − 13.9 (− 16.1, − 12.6) | 0.007 |

| RV longitudinal strain | − 14.7 ± 4.2 | − 12.4 ± 2.9 | 0.067 |

| LV circumferential strain | − 17.1 (− 20.0, − 14.8) | − 16.8 (− 18.7, − 15.2) | 0.648 |

Each value is expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range)

EDV end diastolic volume, RV right ventricle, LV left ventricle

Discussion

There are few studies evaluating STE in patients who underwent ASO. Some of these studies focused on mid to long-term analysis of ventricular function [24, 25]. Others have evaluated the changes in pre-operative versus post-operative function [26]. To our knowledge, no studies have used clinical outcomes as a primary endpoint. This study shows that pre-operative LV function as measured by longitudinal strain correlates with post-operative LOS in infants > 28 days undergoing ASO, but not in neonates.

Neonates versus Infants

We divided patients into two groups, neonates and infants. There were statistically significant differences between these groups in characteristics that have been shown in other studies to be predictive of either post-operative morbidity or LOS.

Unsurprisingly neonates were smaller than infants, although none weighed less than 2.5 kg, a cut off which has been shown to be a risk factor for morbidity in previous studies [8]. Infants had a lower birth weight, but a higher operative weight. Infants also had longer aortic cross clamp (and trended toward longer CPB times). Of the patients undergoing ASO as infants, a VSD was present 92% (12 out of 13). Overall these data are consistent with our institutions preference to perform ASO within the first week of life for standard risk patients. Patients with low birth weight and complicated intracardiac anatomy had delayed repair after a period of interval growth if they had a mechanism to keep the LV trained (such as an unrestrictive VSD).

It is unclear why neonates in the current study had abnormal pre-operative ventricular function as measured by STE. Pre-operative d-TGA patients in a previous study had normal pre-operative LV longitudinal strain [26]. It is possible that our echocardiograms were obtained in the setting of perinatal hypoxia and acidosis from a neonate during stabilization, and that repeat echocardiography obtained immediately pre-operatively would have shown improved ventricular function. LV “de-training” would be unlikely over this time period, as 97% (38/39) had the presence of either a VSD or a patent ductus arteriosus, which would expose the LV to systemic vascular resistance. Alternatively, STE was performed using different software packages and at different frame rates, which may account for the differences between studies. However, it is important to note that both studies showed worsened longitudinal strain after ASO.

Predictors of Post‑operative LOS

Overall, pre-operative LV longitudinal strain correlated with post-operative LOS; however standard 2D measures of ventricular function did not. This correlation became stronger when we evaluated the infant separately from neonates. This suggests that infants who were identified as having normal function by standard 2D measures may indeed have had subclinical ventricular dysfunction that influenced the post-operative course. We suspect that subclinical ventricular function pre-operatively corresponds with worse cardiac output in the immediate post-operative period, requiring increased ionotropic support, prolonging time to extubation, and delaying time until re-initiation of feeds, all of which prolong the post-operative LOS. This hypothesis should be investigated in future larger studies.

We did not find a correlation between pre-operative LV longitudinal strain and post-operative LOS in neonates undergoing ASO. This is not altogether surprising. There are multiple patient characteristics and perioperative factors that have been associated with the clinical course of patients undergoing ASO [4–9]. These factors appear to be stronger predictors of post-operative LOS compared to pre-operative myocardial deformation. Neonates also face unique post-operative considerations compared to infants including the development of feeding skills and family training that may play a significant role in post-operative LOS.

We have also shown that CPB time correlated with post-operative LOS, while operative age and weight inversely correlated with post-operative LOS. Unfortunately, the small sample size precluded multiple variable regressions, and therefore, identifying independent predictors of LOS was not feasible in this study.

Change in Ventricular Function After ASO

Overall LV function worsened after ASO when measured by LV ejection fraction and LV longitudinal strain. LV circumferential strain was unchanged. RV fractional area change improved while RV longitudinal strain worsened. This is consistent with previous studies that have shown worsening biventricular function after undergoing CPB [26, 27]. Potential etiologies include CPB, changes in loading conditions, and myocardial ischemia–reperfusion. The RV seems particularly sensitive to CPB [21].

Implementation and Future Directions

STE is becoming more prevalent in the field of pediatric cardiology and congenital heart disease. It can easily be performed on standard echocardiographic views recommended as part of a complete pre-operative transthoracic echocardiogram [28]. If included in the pre-operative evaluation, it may help to risk stratify infants based on expected post-operative course and more accurately counsel families. As the correlation was strongest for infants, STE may have a role in the assessment of patients with delayed presentation for surgery. For example, in patients who undergoing a palliative surgery prior to the ASO, STE may be used to assess readiness or predict outcome after ASO. It is also worth noting that late ASO for TGA with IVS is not uncommon in countries with developing health systems; ASO may be useful to determine the degree of LV “training” prior to ASO in this setting. Further studies should evaluate the ability of STE to predict outcomes in patients undergoing ASO prospectively in a larger cohort.

Limitations

This was a retrospective study and by its nature could not establish causality. Our analysis required high quality echocardiographic images and complete studies. There was no defined echocardiogram protocol for pre-operative studies, and a thorough post-operative or “discharge” study only became standard later during our study period [29]. Anecdotally, many of the patients excluded from the study due to inadequate windows were from early during the study period, which may have affected results. Our definition of pre-operative and post-operative echocardiogram meant that there was some variability in the proximity of the echocardiogram to the operative date. This study type is susceptible to unmeasured confounders. The small sample size lacked the power to perform multiple variable regression analyses. The STE analysis was performed on DICOM images at 30 frames per second; potentially leading to underestimated strain values, though some studies purport the adequacy of these images in evaluating strain [22].

Conclusions

Pre-operative LV longitudinal strain correlates moderately with post-operative LOS in infants > 28 days undergoing ASO. LV longitudinal strain worsens after ASO. STE should be considered for inclusion in the standard pre-operative evaluation to help risk stratify patients prior to ASO, especially in patients undergoing late repair.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Villafane J, Lantin-Hermoso MR, Bhatt AB, Tweddell JS, Geva T, Nathan M, Elliott MJ, Vetter VL, Paridon SM, Kochilas L, Jenkins KJ, Beekman RH IIIrd, Wernovsky G, Towbin JA (2014) D-transposition of the great arteries: the current era of the arterial switch operation. J Am Coll Cardiol 64:498–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khairy P, Clair M, Fernandes SM, Blume ED, Powell AJ, Newburger JW, Landzberg MJ, Mayer JE Jr (2013) Cardiovascular outcomes after the arterial switch operation for D-transposition of the great arteries. Circulation 127:331–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs JP, Mayer JE Jr, Pasquali SK, Hill KD, Overman DM, St Louis JD, Kumar SR, Backer CL, Fraser CD, Tweddell JS, Jacobs ML (2018) The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database: 2018 update on outcomes and quality. Ann Thorac Surg 105:680–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iliopoulos I, Burke R, Hannan R, Bolivar J, Cooper DS, Zafar F, Rossi A (2016) Preoperative intubation and lack of enteral nutrition are associated with prolonged stay after arterial switch operation. Pediatr Cardiol 37:1078–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qamar ZA, Goldberg CS, Devaney EJ, Bove EL, Ohye RG (2007) Current risk factors and outcomes for the arterial switch operation. Ann Thorac Surg 84:871–878 (discussion 878–879) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wheeler DS, Dent CL, Manning PB, Nelson DP (2008) Factors prolonging length of stay in the cardiac intensive care unit following the arterial switch operation. Cardiol Young 18:41–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blume ED, Altmann K, Mayer JE, Colan SD, Gauvreau K, Geva T (1999) Evolution of risk factors influencing early mortality of the arterial switch operation. J Am Coll Cardiol 33:1702–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fricke TA, d’Udekem Y, Richardson M, Thuys C, Dronavalli M, Ramsay JM, Wheaton G, Grigg LE, Brizard CP, Konstantinov IE (2012) Outcomes of the arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries: 25 years of experience. Ann Thorac Surg 94:139–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X, Shi S, Shi Z, Ye J, Tan L, Lin R, Yu J, Shu Q (2012) Factors associated with prolonged recovery after the arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries in infants. Pediatr Cardiol 33:1383–1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foran JP, Sullivan ID, Elliott MJ, de Leval MR (1998) Primary arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries with intact ventricular septum in infants older than 21 days. J Am Coll Cardiol 31:883–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ota N, Sivalingam S, Pau KK, Hew CC, Dillon J, Latiff HA, Samion H, Yakub MA (2018) Primary arterial switch operation for late referral of transposition of the great arteries with intact ventricular septum in the current era: do we still need a rapid two-stage operation? World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg 9:74–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacour-Gayet F, Piot D, Zoghbi J, Serraf A, Gruber P, Macé L, Touchot A, Planché C (2001) Surgical management and indication of left ventricular retraining in arterial switch for transposition of the great arteries with intact ventricular septum. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 20:824–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarris GE, Balmer C, Bonou P, Comas JV, da Cruz E, Chiara LD, Di Donato RM, Fragata J, Jokinen TE, Kirvassilis G, Lytrivi I, Milojevic M, Sharland G, Siepe M, Stein J, Büchel EV, Vouhé PR (2017) Clinical guidelines for the management of patients with transposition of the great arteries with intact ventricular septum. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 51:e1–e32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain A, El-Khuffash AF, Kuipers BCW, Mohamed A, Connelly KA, McNamara PJ, Jankov RP, Mertens L (2017) Left ventricular function in healthy term neonates during the transitional period. J Pediatr 182:197–203.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy PT, Machefsky A, Sanchez AA, Patel MD, Rogal S, Fowler S, Yaeger L, Hardi A, Holland MR, Hamvas A, Singh GK (2016) Reference ranges of left ventricular strain measures by two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 29:209–225. e206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mokhles P, van den Bosch AE, Vletter-McGhie JS, Van Domburg RT, Ruys TP, Kauer F, Geleijnse ML, Roos-Hesselink JW (2013) Feasibility and observer reproducibility of speckle tracking echocardiography in congenital heart disease patients. Echocardiography (Mount Kisco NY) 30:961–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forsey J, Friedberg MK, Mertens L (2013) Speckle tracking echocardiography in pediatric and congenital heart disease. Echocardiography (Mount Kisco NY) 30:447–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colquitt JL, Pignatelli RH (2016) Strain imaging: the emergence of speckle tracking echocardiography into clinical pediatric cardiology. Congenit Heart Dis 11:199–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toro-Salazar OH, Ferranti J, Lorenzoni R, Walling S, Mazur W, Raman SV, Davey BT, Gillan E, O’Loughlin M, Klas B, Hor KN (2016) Feasibility of echocardiographic techniques to detect subclinical cancer therapeutics-related cardiac dysfunction among high-dose patients when compared with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 29:119–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klitsie LM, Roest AAW, Blom NA, ten Harkel ADJ (2014) Ventricular performance after surgery for a congenital heart defect as assessed using advanced echocardiography: from doppler flow to 3D echocardiography and speckle-tracking strain imaging. Pediatr Cardiol 35:3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karsenty C, Hadeed K, Dulac Y, Semet F, Alacoque X, Breinig S, Leobon B, Acar P, Hascoet S (2017) Two-dimensional right ventricular strain by speckle tracking for assessment of longitudinal right ventricular function after paediatric congenital heart disease surgery. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 110:157–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koopman LP, Slorach C, Manlhiot C, McCrindle BW, Jaeggi ET, Mertens L, Friedberg MK (2011) Assessment of myocardial deformation in children using Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) data and vendor independent speckle tracking software. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 24:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez L, Colan SD, Frommelt PC, Ensing GJ, Kendall K, Younoszai AK, Lai WW, Geva T (2010) Recommendations for quantification methods during the performance of a pediatric echocardiogram: a report from the Pediatric Measurements Writing Group of the American Society of Echocardiography Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease Council. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 23:465–495 (quiz 576–467) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Salvo G, Al Bulbul Z, Issa Z, Fadel B, Al-Sehly A, Pergola V, Al Halees Z, Al Fayyadh M (2016) Left ventricular mechanics after arterial switch operation: a speckle-tracking echocardiography study. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown MD) 17:217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pettersen E, Fredriksen PM, Urheim S, Thaulow E, Smith HJ, Smevik B, Smiseth O, Andersen K (2009) Ventricular function in patients with transposition of the great arteries operated with arterial switch. Am J Cardiol 104:583–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klitsie LM, Roest AA, Kuipers IM, Hazekamp MG, Blom NA, Ten Harkel AD (2014) Left and right ventricular performance after arterial switch operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 147:1561–1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boer JM, Kuipers IM, Klitsie LM, Blom NA, Harkel ADJ (2017) Decreased biventricular longitudinal strain shortly after congenital heart defect surgery. Echocardiography (Mount Kisco NY) 34:446–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen MS, Eidem BW, Cetta F, Fogel MA, Frommelt PC, Ganame J, Han BK, Kimball TR, Johnson RK, Mertens L, Paridon SM, Powell AJ, Lopez L (2016) Multimodality imaging guidelines of patients with transposition of the great arteries: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography Developed in Collaboration with the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 29:571–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parthiban A, Levine JC, Nathan M, Marshall JA, Shirali GS, Simon SD, Colan SD, Newburger JW, Raghuveer G (2016) Impact of variability in echocardiographic interpretation on assessment of adequacy of repair following congenital heart surgery: a pilot study. Pediatr Cardiol 37:144–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]