Abstract

Background:

HIV prevalence has increased among South African women who use alcohol and other drugs (AOD). However, HIV prevention and treatment efforts have not focused on this population. This study presents efficacy of the Women’s Health CoOp Plus (WHC+) in a cluster-randomized trial to reduce AOD use, gender-based violence, and sexual risk and to increase linkage to HIV care among women who use AODs, compared with HIV counseling and testing alone.

Methods:

Black African women (N = 641) were recruited from 14 geographic clusters in Pretoria, South Africa, and underwent either an evidence-based gender-focused HIV prevention intervention that included HIV counseling and testing (WHC+) or HIV counseling and testing alone. Participants were assessed at baseline, 6-months, and 12-months post enrollment.

Results:

At 6-month follow-up, the WHC+ arm (vs. HCT) reported more condom use with a main partner and sexual negotiation, less physical and sexual abuse by a boyfriend, and less frequent heavy drinking (ps < 0.05). At 12-month follow-up, the WHC+ arm reported less emotional abuse (p < 0.05). Among a subsample of women, WHC+ arm was significantly more likely to have a non-detectable viral load (measured by dried blood spots; p = 0.01).

Conclusion:

The findings demonstrate the WHC+’s efficacy to reduce HIV risk among women who use AODs in South Africa. Substance abuse rehabilitation centers and health centers that serve women may be ideal settings to address issues of gender-based violence and sexual risk as women engage in substance use treatment, HIV testing, or HIV care.

Clinical Trial Number: NCT01497405

Keywords: HIV Prevention, HIV Care, Women, Alcohol and Other Drug Use, Gender-Based Violence, Sexual Risk

1. Introduction

In 2014, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) launched the 90-90-90 targets (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2014a). The aim is that by 2020, 90% of people living with HIV will know their HIV status, 90% of those diagnosed with HIV will receive sustained antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 90% of those receiving ART will be virally suppressed. These targets addressed the progress along the HIV treatment cascade. As we near 2020, significant progress has been made toward the 90-90-90 goals (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2017a). However, psychosocial factors such as alcohol and other drug (AOD) use, gender-based violence (GBV), and sexual risk create barriers to achieving these benchmarks, especially among women.

AOD use has been consistently linked to HIV risk for more than a decade (Kalichman et al., 2007; Parry and Pithey, 2006). Women who use substances are especially vulnerable to HIV risk (Pitpitan et al., 2013; Pitpitan et al., 2012), as AOD use increases HIV risk through impaired judgment, increasing the likelihood of condomless sex (Fisher et al., 2007; Kalichman et al., 2007; Strathdee, 2010; Wechsberg et al., 2012). Additionally, women who are dependent on AODs may rely on sex work to obtain drugs or money for drugs, and they may be less likely to negotiate condom use, which can increase their risk for HIV (Strathdee, 2010). Alternatively, women may use AODs to cope with trading sex, which may lower their inhibitions to engage in condomless sex (Wechsberg et al., 2005; Wechsberg et al., 2006). Consequently, it is troublesome that HIV prevention and treatment efforts such as seek, test, treat, and retain (STTR) and HIV treatment as prevention (TasP) have not focused on this population (Hull and Montaner, 2013; World Health Organization, 2012).

Further, AOD use is a barrier to health care access and ART adherence for women living with HIV (Azar et al., 2010; Luseno et al., 2010). Women who use AODs are less likely to initiate and adhere to HIV care and treatment (Medley et al., 2014; Mekuria et al., 2017; Ndirangu et al., 2014; Shoptaw et al., 2013). Some women may not take their antiretroviral (ARV) medication on the weekends because they fear that mixing alcohol and ARV medication may result in adverse side effects or reduce the effect of the medication (Kalichman et al., 2012; Kalichman et al., 2013; Pellowski et al., 2016). As a result of not being linked to care or not adhering to ART, some women who use AODs may have increased viral loads, suffer adverse health consequences, and transmit HIV (Cohen et al., 2011; Cohen and Gay, 2010). Unfortunately, AOD use is not addressed in standard HIV prevention and treatment efforts such as HIV testing and counseling (Republic of South Africa, 2015), many women are unaware of the effects of AOD use, especially alcohol (Hlomani, 2013), and there are multiple barriers to accessing substance abuse treatment (Myers et al., 2011). Consequently, to reduce HIV infection and prevent HIV transmission, substance use must be addressed among women in South Africa.

Moreover, women who use AODs are more likely to experience GBV (El-Bassel et al., 2011), which increases risk for HIV (Dunkle et al., 2004; El-Bassel et al., 2011; Jewkes et al., 2010) and decreases the ability to seek HIV care (Skovdal et al., 2011). GBV increases risk for HIV through coerced condomless sex, rape, and the inability of women to negotiate safer sex (Dunkle et al., 2004; Jewkes and Abrahams, 2002; Jewkes et al., 2010; Townsend et al., 2011; Wechsberg et al., 2013b). Among women living with HIV, GBV may impair their ability to seek HIV care (Lopez et al., 2010; Maman et al., 2002). Some South African men use violence to prevent their female partners from seeking HIV health services because they fear that their own HIV-positive status will be revealed (Skovdal et al., 2011). GBV poses a significant challenge to HIV prevention and care for South African women, especially those who use AODs.

In sum, the nexus of AOD use, GBV, and sexual risk contributed to HIV risk and decreased access to HIV care (Meyer et al., 2011). Consequently, interventions must address these risk factors to reduce HIV incidence (Meyer et al., 2011) and increase access to HIV healthcare (Luseno et al., 2010) among women who use AODs. Some interventions address AOD use, GBV, or sexual risk as HIV risk factors (Cain et al., 2012; Jewkes et al., 2006; Kalichman, 2010). However, few interventions address these factors to increase linkage to care or address the nexus of these factors (Wechsberg et al., 2010a).

The Women’s Health CoOp (WHC) is an evidence-based, woman-focused, behavioral intervention that addresses AOD use, GBV, and sexual risk, with the primary goal of increasing skills and knowledge to reduce HIV risk among women who use AODs. The WHC is based on social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1994) and empowerment theory(Wechsberg, 1998), and it was originally developed for African American women who used crack cocaine in North Carolina (Wechsberg et al., 2004). The WHC has been adapted for multiple populations, named a best-evidence intervention by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and included in the United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID) compendium of prevention interventions that are recommended for use in Africa (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013; Lyles et al., 2007; USAID, 2009). Although the WHC has demonstrated efficacy in reducing behavioral HIV risk, it has not emphasized STTR; consequently, linkage to care and the promotion of ART initiation and adherence were added as an important biobehavioral advancement (Wechsberg et al., 2017c), given that TasP is key to accomplishing the UNAIDS goals (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2014b).

The current study evaluates the efficacy of the Women’s Health CoOp Plus (WHC+), an evidencebased gender-focused HIV prevention intervention that includes HIV counseling and testing (HCT), to reduce AOD use, GBV and sexual risk, and to increase linkage to HIV care among women who use AODs, as compared with HCT alone. This cluster-randomized trial (CRT) was conducted in Pretoria, South Africa, where there is a high prevalence of HIV and AOD use among the study’s target population (Wechsberg et al., 2011). A CRT design was used to prevent contamination across study arms. Our hypotheses, which focused on individual-level outcomes, were that women in the WHC+ arm would be less likely to report AOD use, GBV, and sexual risk behaviors at 6- and 12-month follow-up, as compared with women in the HCT arm. It is also expected that, among women who test positive for HIV, a greater proportion of women in the WHC+ arm will report attending a medical evaluation, as compared with women in the HCT arm.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study design and procedure

Pretoria was divided into 14 mutually exclusive geographic clusters. Cluster creation was informed by the previous mapping of “hot spots” for AOD use and HIV risk among women across the city. Clusters were separated by barriers such as freeways, railroads, and rivers. Each cluster was matched with a similar cluster based on size, urbanicity, and previously known behaviors of AOD use, sex trading, and HIV risk. Within each pair, one cluster was randomized to either the WHC+ arm or the HCT arm. The randomization system was developed by the data manager and conducted using a computer-generated sequence. Consent at the cluster-level was not obtained. However, we consulted with a Community Collaborative Board and outreach workers familiar with Pretoria to determine the clusters and develop recruitment strategies.

The South African Medical Association Research Ethics Committee (SAMAREC), Tshwane Research Committee (TRC), and the RTI International Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects approved the study procedures. Additionally, we established a Data and Safety Monitoring Board comprising experts and physicians in HIV and bioethics. The study results are reported in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines for CRTs (Campbell et al., 2012).

2.2. Participant recruitment and procedures

Recruitment was completed from May 2012 through September 2014 using a variety of community outreach methods (Wechsberg et al., 2010b; Wechsberg et al., 2006). Participants had to be Black African women aged 15 or older (if aged 15 to 17, with evidence of tacit emancipation1); use at least one substance (which could be alcohol) weekly for the past 3-months; have had sex with a male partner without a condom in the past 6-months; speak English, Sesotho, Zulu/isiXhosa, or Setswana; provide informed consent; and provide verifiable locator information and plan to remain in Pretoria for the next 12-months. Eligible women who wanted to participate in the study were scheduled for an intake appointment at the field site or in a private setting in the community. At the intake appointment, women were rescreened and asked to provide informed consent, complete a baseline interview using computerassisted personal interviewing (CAPI), and participate in biological testing for drugs (i.e., panel drug urine screen), alcohol (i.e., breathalyzer), pregnancy (i.e., urine test), and HIV (i.e., rapid blood test). At a later stage of the study, dried blood spots were collected to measure the viral load concentration of participants who tested positive for HIV.

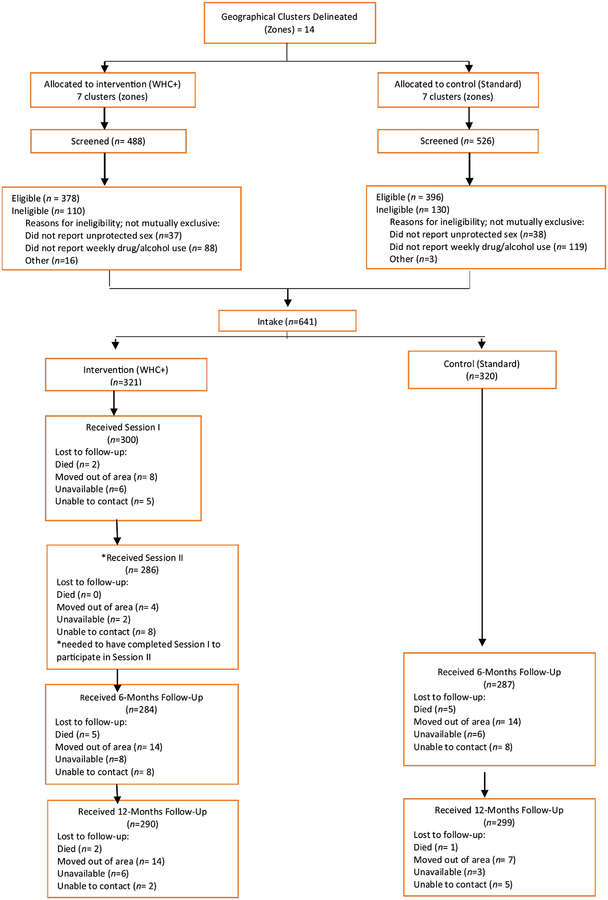

Women in the WHC+ arm were scheduled for two intervention sessions approximately one week apart. All participants were scheduled to return at 6- and 12-months to complete follow-up interviews and biological testing. Staff members who conducted the WHC+ intervention or baseline assessments did not conduct the follow-up interviews. Participants were provided with refreshments and vouchers valued at R70 (approximately $7), R100 (approximately $10), and R150 (approximately $15) for their time during the baseline, 6-month, and 12-month appointments respectively. Health kits were also provided at the 6- and 12-month appointments. Staff members also provided meals, coordinated childcare, and arranged transportation to the field site for all appointments. A total of 641 participants (between 16 and 58 women from each cluster) were enrolled (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

2.3. Interventions

2.3.1. Standard HIV counseling and testing

Participants in the HCT arm underwent the standard individual HCT protocol in accordance with South African treatment guidelines (Republic of South Africa, 2010). This protocol included pretesting, rapid HIV testing, post-counseling, and a brief syndromic tuberculosis screener. Participants who tested positive for HIV were first referred for further medical evaluation to determine eligibility for ART. To help alleviate the barrier to clinical staging, the study began conducting CD4 testing at the study site using a point of care PIMA™ analyzer. Participants received CD4 testing at 6- and 12-month follow-up. However, these data were not used for analysis. Women who were not eligible for ART at that time were referred to a wellness program conducted in local health facilities.

The study staff also provided passive referrals to substance abuse rehabilitation, GBV counseling, and skills development. If participants tested positive for pregnancy, they were provided active referrals for antenatal care.

On January 1, 2015, the South African HIV treatment guidelines changed and the CD4 count eligibility criterion for ART initiation changed from ≤350 cells/mm2 to ≤500 cells/mm2 (Department of Health, 2014). Consequently, some participants who tested positive for HIV who were ineligible for ART at enrollment later became eligible for ART though this change was slow to take effect.

2.3.2. Women’s Health CoOp Plus

Women in the WHC+ arm underwent HCT and participated in two individual intervention sessions approximately a week apart. Each session lasted about an hour. Sessions took place at the study site and were facilitated by an experienced, multilingual female interventionist from the community.

The sessions aimed to educate participants about the risks of AOD use and how AOD use and sexual risk are related to HIV for women and their gender power. Sessions also covered risk-reduction strategies—such as correct condom use, sexual negotiation, and violence prevention strategies—and included role-play and rehearsal. Participants created personalized action plans after their first session and completed this plan in their second session. The action plan included specific actions to reduce risk. Participants took home the plan at the end of the second session. A goal of the intervention was to provide case management via in-person visits or by mobile phone by study staff at least monthly to support the participant in her goals and risk-reduction behavior. Staff worked with substance abuse rehabilitation facilities to coordinate referrals to treatment for participants with AOD use problems.

2.4. Measures

Condom use was assessed as the number of vaginal sex episodes with a condom during the past month. Condom use at last sex was also assessed.

Alcohol use was measured by the number of days of heavy drinking (4 or more drinks) in the past 30-days. Given the high prevalence of heavy drinking in South Africa (Parry et al., 2005), participants who reported they had engaged in heavy drinking on 11 or more of the past 30-days were categorized as a frequent heavy drinker; participants who reported they did not, were categorized as not a frequent heavy drinker (Wechsberg et al., 2017b). We also assessed the number of days that participants engaged in alcohol use and the average number of alcoholic beverages that participants consumed when they were drinking in the past month.

Use of the most commonly used drugs—marijuana, cocaine, and opiates—was assessed using a urine drug screen. Test results were coded as positive or negative. Drug use was also measured using self-reported frequency of drug use in the past 30-days. Participants who reported using at least one drug every day during the past 30-days were categorized as a daily drug user; participants who did not were categorized as not a daily drug user.

GBV during the past 90-days was assessed using four individual items to measure emotional abuse, being attacked with a weapon, being beaten, or sexual abuse by a boyfriend. Each response was coded as 0 = No or 1 = Yes.

Among participants who had been diagnosed with HIV before their study appointment, self-reported linkage to care was assessed by the item “Have you been referred to a medical assessment?” Participants responded either 1 = Yes, went to medical assessment, 2 = Yes, but have not gone to medical assessment, or 3 = No. Responses were coded such that referral for a medical assessment (no or yes) and attendance at a medical assessment (no or yes) were separate variables.

To assess ART initiation, participants were asked, “Have you been prescribed any anti-HIV medications?” Participants responded either yes or no.

To assess ART adherence, whole blood spots (dried blood spot [DBS]) samples were taken from a subsample (n=290) of participants living with HIV at the 6- and 12-month follow-up visits to test for viral load concentration. DBS samples were collected and prepared according to the recommended protocol from the World Health Organization (WHO) for the collection and handling of DBS (World Health Organization, 2005). Two assays were used to analyze the samples. The Abbott RealTime HIV-1 Assay using the 0.6 ml program was used to measure HIV-1 viral load in 103 samples, and the Panther® system Assay was used to measure HIV-1 viral load in an additional 188 samples (using one whole spot from each sample), accounting for the dilution factor of eluting the DBS, making the lower limit of quantification 1360 cp/ml for DBS on the Abbott assay and 600 cp/ml for DBS on the Hologic assay.

Samples that were below the lower limit of quantification of 1360 cp/ml were listed as “Nondetectable.” Samples that were at or above the lower limit of quantification were considered “Detectable.” A non-detectable viral load is associated with optimal ART adherence of 85% or higher (Kobin and Sheth, 2011). Consequently, we used viral load as a proxy for at least 85% ART adherence. Participants with a non-detectable viral load were considered adherent and participants who had a detectable viral load were considered nonadherent.

Sexual negotiation with a boyfriend in the past 90-days also was assessed. Condom negotiation, condom use while high, and the refusal of sex without a condom were assessed using three separate items. Responses were given on a Likert scale, with 1 = Not at all and 4 = All the time.

Sex worker status (i.e., engaging in sex work during the past 6-months) was entered as a covariate because 41% of the sample reported engaging in sex work, and sex work has been associated with sexual risk, AOD use, and engagement in HIV care (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). HIV status at baseline also was included as a covariate because of its association with the outcomes of interest.

2.5. Analytic approach

We used Stata version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for all analyses and a p-value of 0.05 was used for significance testing.

The study arms were compared on baseline sociodemographic characteristics. Participants who tested positive for HIV at enrollment were compared in terms of HIV care. Comparisons were made using analysis of variance for continuous variables and logistic regression for binary variables, accounting for clustering. Participants lost to follow-up also were compared with participants who returned for their appointments across study arms and with sociodemographic variables at baseline.

The primary analyses sought to assess whether there were differences between the study arms in outcomes at 6-month follow-up and whether differences were sustained at 12-month follow-up. Treatment differences were estimated using multiple linear regression (for continuous outcomes), logistic regression (for binary outcomes), and negative binomial regression (for count outcomes because of overdispersion (Hilbe, 2011), with robust standard errors to account for geographical clustering. The intraclass correlation also was calculated for all outcomes, per the CONSORT guidelines (Campbell et al., 2004). All analyses controlled for baseline HIV status, sex worker status, and baseline level of each outcome.

We performed outcome analyses using an intent-to-treat approach, with participants analyzed based on the study arm to which their cluster had been assigned, regardless of attendance or exposure. All clusters were included in each analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the sample by study arm are shown in Table 1. An average of 46 (SD = 18.7; median = 47) women were recruited in each cluster (not shown). At study enrollment, fewer women in the WHC+ arm reported trading sex in the past 6-months (p = 0.01) or engaging in frequent heavy drinking in the past 30-days (p < 0.001). More women in the WHC+ arm reported daily drug use and tested positive for cocaine, heroin, and marijuana (all p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Sample for the Women’s Health CoOp PLUS by treatment (n = 641 at enrollment)

| Total | HCT | WHC+ | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n= 641* | n= 320 | n= 321 | |||||

| N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | ||

| Age | 29.86 | 7.80 | 29.90 | 7.61 | 29.82 | 7.99 | 0.90 |

| Currently homeless | 171 | 26.68 | 90 | 28.13 | 81 | 25.23 | 0.41 |

| Currently unemployed | 576 | 89.86 | 285 | 89.06 | 291 | 90.65 | 0.50 |

| Traded sex in the past 6 months | 262 | 40.87 | 148 | 46.25 | 114 | 35.51 | 0.01 |

| HIV positive | 354 | 55.23 | 196 | 61.25 | 158 | 49.22 | < 0.001 |

| HIV care-related factors | |||||||

| Received a medical evaluation (n =241) | 121 | 50.21 | 72 | 54.14 | 49 | 45.37 | 0.18 |

| Prescribed Antiretrovirals (n = 236 who were diagnosed before enrollment) | 80 | 33.90 | 47 | 35.34 | 33 | 32.04 | 0.60 |

| Alcohol and Drug Use | |||||||

| Frequent Heavy Drinking | 205 | 31.98 | 124 | 38.75 | 81 | 25.23 | < 0.001 |

| Days of Binge Drinking | 8.67 | 8.18 | 9.93 | 8.28 | 7.41 | 7.89 | < 0.001 |

| Daily Drug Use | 205 | 31.98 | 86 | 26.88 | 119 | 37.07 | 0.01 |

| Tested positive for cocaine | 92 | 14.35 | 26 | 8.13 | 66 | 20.56 | < 0.001 |

| Tested positive for opiates | 115 | 17.94 | 30 | 9.38 | 85 | 26.48 | < 0.001 |

| Tested positive for marijuana | 201 | 31.36 | 79 | 24.69 | 122 | 38.01 | < 0.001 |

| Abuse and Violence | |||||||

| Lifetime physical or sexual abuse | 226 | 35.26 | 114 | 35.63 | 112 | 34.89 | 0.85 |

| Abuse by a Boyfriend in the Last 90 Days (n = 535) | |||||||

| Emotional abuse | 252 | 45.57 | 128 | 47.06 | 124 | 44.13 | 0.49 |

| Attacked with a weapon | 37 | 6.69 | 19 | 6.99 | 18 | 6.41 | 0.79 |

| Beaten or struck | 79 | 14.29 | 44 | 16.18 | 35 | 12.46 | 0.21 |

| Sexual abuse | 73 | 13.20 | 37 | 13.60 | 36 | 12.81 | 0.78 |

| Sexual Risk | |||||||

| Condomless last sex (n = 632) | 400 | 63.29 | 199 | 62.78 | 201 | 63.81 | 0.79 |

| Condom use with main partner at last sex (n = 553) | 122 | 22.06 | 52 | 19.12 | 70 | 24.91 | 0.10 |

| Condom use with casual partner or client at last sex (n =352) | 289 | 82.10 | 159 | 82.81 | 130 | 81.25 | 0.70 |

| Alcohol or drugs before or during sex at last sex | 359 | 56.01 | 173 | 54.06 | 186 | 57.94 | 0.32 |

| Number of episodes of sex with a condom with main partner in the past 30 days (n = 535) | 2.00 | 4.47 | 2.11 | 4.97 | 1.90 | 3.93 | 0.59 |

| Number of episodes of sex with a condom with casual partner in the past 30 days (n= 179) | 2.68 | 3.46 | 2.98 | 4.33 | 2.37 | 2.23 | 0.24 |

3.2. Intervention dose and study retention

As shown in the CONSORT diagram in Figure 1, of the participants who were in clusters randomized to the WHC+ arm, 93% completed the first session and 89% completed the second session. Approximately, 89% of participants completed their 6-month follow-up appointment and 92% of participants completed their 12-month follow-up appointment. There were no differences in 6- or 12month attrition by study arm (all p > 0.05). There were 15 non-study related deaths during the study. Other reasons for attrition were that participants had moved out of the area or the staff were unable to contact participants for their follow-up appointment. Differences were found in 6- and 12-month attrition across clusters randomized to the WHC+ arm and HCT study arm (all p < 0.04).

There were differences in attrition by drug use. Participants who did not complete the 6-month follow-up were less likely to test positive for any drug (p = 0.009) and to report daily drug use in the past 30-days at baseline as compared to those who completed the follow-up visit (all p <.05). Participants who did not complete the 6-month follow-up also tested positive for a greater number of drugs at baseline than those who completed the appointment (p = 0.02). However, significant differences in drug use were only found in the WHC+ arm; there were no significant differences in drug use in the HCT only arm (all p < 0.05). Participants who did not complete the 6-month follow-up were also less likely to report being beaten by their boyfriend in the past 3-months at baseline (p = 0.004), and this difference was only significant in the WHC+ arm (p = 0.03). Lastly, participants who did not complete the 6-month follow-up appointment were younger than those who completed the appointment (p = 0.004). This difference was only significant in the WHC+ arm (p = 0.007).

There were also differences in 12-month attrition by drug use. Participants who did not complete the 12-month follow-up were less likely to test positive for any drug at baseline (p < 0.001). This difference was significant in both study arms (p < 0.05). However, participants who did not complete the 12-month follow-up tested positive for a greater number of drugs at baseline (p = 0.02) than those who completed the appointment (WHC+: p = 0.09; HCT: p = 0.22). Participants who did not complete the 12-month follow-up appointment were less likely to report daily drug use in the past 30-days (p = 0.001), and this difference was only significant in the WHC+ arm (p = 0.003). Participants who did not complete the 12month follow-up were also less likely to report at baseline that their boyfriend had attacked them in the past 3-months (p = 0.05), and this difference was only significant in the WHC+ arm (p = 0.01). Participants who did not complete the 12-month follow visit were also less likely to test positive for HIV at baseline (p = 0.02; WHC+: p = 0.07; HCT: p = 0.06). Lastly, participants who did not complete their 12-month follow-up were more likely to report engaging in condomless sex at their last sex act (p = 0.005), and this difference was only significant in the WHC+ arm (p = 0.04).

3.3. Primary outcomes

The effects of the WHC+ intervention on sexual risk, AOD use, and gender-based violence, controlling for reported sex work, HIV status, and baseline data are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Models with Treatment Condition Predicting Outcomes with HCT only as the Reference Group

| 6-month follow-up | ||||||||||||||||

| Sexual Risk | Substance Use | Gender-based Violence | HIV Care | ARVs | ||||||||||||

| Condom Use at Last Sex (Y/N) | Number of Sex Acts with a Condom in the Last Month | Alcohol/Drug Use at Last Sex (Y/N) | Frequen t Heavy Drinking (Y/N) | Daily Drug Use (Y/N) | Pos. Opiates (Y/N) | Pos. Cocaine (Y/N) | Pos. Marijuana (Y/N) | Emotional Abuse (Y/N) | Attack ed w/Weapon (Y/N) | Beaten (Y/N) | Sexually Abused (Y/N) | Attended Appointment Since Diagnosis (Y/N) | Prescribed ARVs (Y/N) | |||

| Main Partner/Boyfriend | Casual Partn er or Client | Main Partner/Boyfriend | Casual Partneror Client | Any Partner | ||||||||||||

| AOR/β | 1.63 | 1.03 | 0.43 | 0.07 | 1.18 | 0.45 | 1.21 | 1.79 | 1.34 | 1.13 | 0.63 | 0.33 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.86 | 0.98 |

| CI | 1.0099, 2.26156 | 0.3140, 3.3877 | 0.0488, 0.8085 | −0.4494, 0.5992 | 0.5593, 2.4820 | 0.2792, 0.7345 | 0.4172, 3.5360 | 0.4272, 7.5312 | 0.3513, 5.1451 | 0.5033, 2.5502 | 0.3626, 1.0810 | 0.1180, 0.9224 | 0.2574, 0.6655 | 0.1860, 0.8630 | 0.4133, 1.8001 | 0.3888, 2.4810 |

| p-value | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.03 | 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.001 | 0.72 | 0.43 | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.09 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 0.97 |

| 12-month follow-up | ||||||||||||||||

| AOR/B | 1.43 | 0.90 | 0.28 | −0.02 | 0.97 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 1.77 | 1.78 | 0.89 | 0.73 | 0.57 | 1.27 | 1.09 | 1.21 | 1.00 |

| CI | 0.9187, 2.2137 | 0.3007, 2.6780 | −0.0815, 0.6368 | −0.5138, 0.4825 | 0.5181, 1.8057 | 0.4327, 1.1792 | 0.2518, 1.6144 | 0.8041, 3.8969 | 0.5424, 5.8310 | 0.4690, 1.7020 | 0.5988, 0.8861 | 0.2502, 1.3032 | 0.6639, 2.4172 | 0.4407, 2.6784 | 0.5512, 2.6505 | 0.4653, 2.1564 |

| p-value | 0.11 | 0.85 | 0.13 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.16 | 0.34 | 0.73 | 0.002 | 0.18 | 0.47 | 0.86 | 0.64 | 1.00 |

3.3.1. Sexual risk

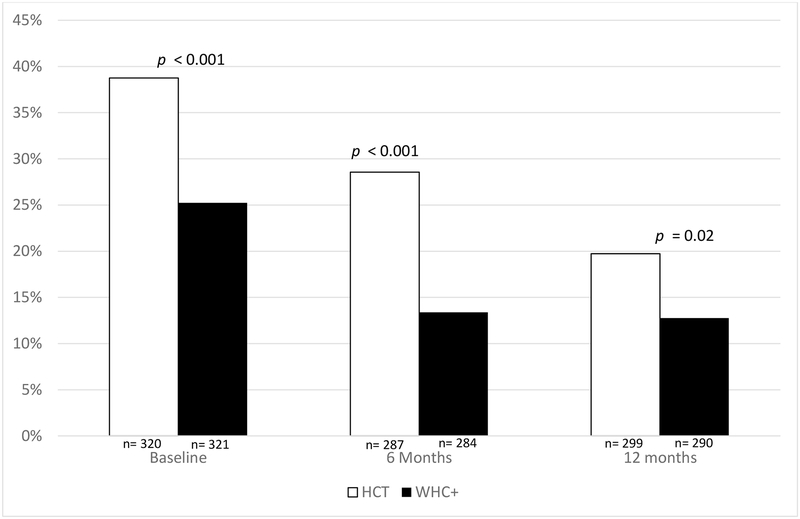

Women in the WHC+ arm were significantly more likely to report at 6-month follow-up that they used a condom during their last sex act with their boyfriend (p = 0.05), but not at 12-month follow-up (p = 0.11), as shown in Figure 2. Women in the WHC+ arm also reported significantly more episodes of condom use during sex with their boyfriends in the past month at 6-month follow-up (p = 0.03), but not at 12-month follow-up (p = 0.13).

Figure 2.

Proportion of Women Reporting Condom Use during Last Sex with Boyfriend by Treatment and Time

*Note: P-values represent the differences between groups at each time point based on chi-squared difference tests.

No statistically significant difference was found in condom use during the last sex act with participants’ casual partner or client between the WHC+ arm and the HCT arm at 6- or 12-month followup (all p > 0.05). Episodes of condom use during sex with a casual partner or client in the past month did not differ between the WHC+ arm and the HCT arm at 6- or 12-month follow-up (all p > 0.05).

AOD use during the last sex act was not significantly different between the WHC+ arm and the HCT arm at 6- or 12-month follow-up (all p > 0.05).

3.3.2. Alcohol and other drug use

Participants in the WHC+ arm were significantly less likely to report frequent heavy drinking at 6-month follow-up (p = 0.001), but not at 12-month follow-up (p = 0.19; see Figure 3). Participants in the WHC+ also reported fewer heavy drinking days at 6-month follow-up (p = 0.01), but not 12-month followup (p = 0.36). Participants in the WHC+ arm also reported fewer drinking days in the past month than participants in the HCT arm (p = 0.03) at 6-month follow-up, but not at 12-month follow-up (p = 0.63; not shown). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the average number of drinks that participants drank during a typical drinking day in the past month at 6- or 12-month follow-up (all p > 0.05; not shown).

Figure 3.

Proportion of Women Who Reported Frequent Heavy Drinking by Treatment and Time

*Note: P-values represent the differences between groups at each time point based on chi-squared difference tests.

No statistically significant difference was found in the proportion of participants who tested positive for opiates, cocaine, or marijuana at 6- or 12-month follow-up (all p > 0.05). Self-reported daily drug use did not differ between the WHC+ arm and the HCT arm at 6- or 12-month follow-up (all p > 0.05).

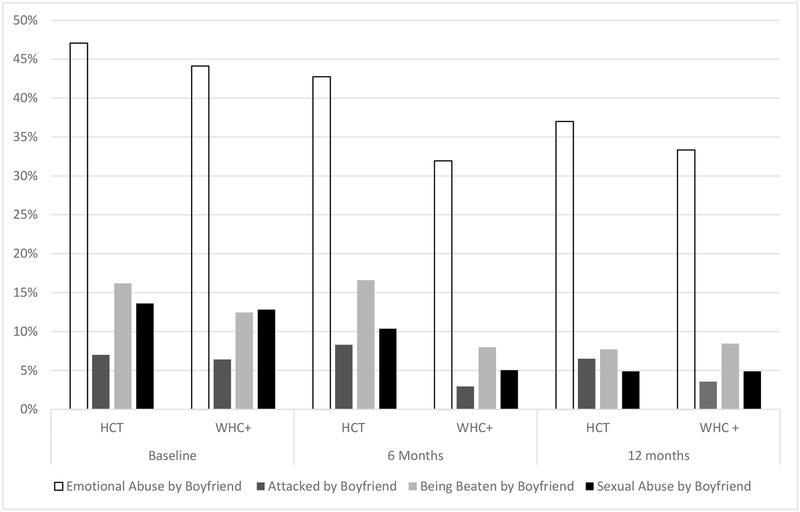

3.3.3. Gender-based violence

Participants in the WHC+ arm were significantly less likely to report being attacked with a weapon, beaten, or sexually abused by a boyfriend at 6-month follow-up (all p < 0.05), but not at 12month follow-up (all p > 0.05). No significant difference was found in emotional abuse from a boyfriend between the WHC+ arm and the HCT arm at 6-month follow-up (p = 0.09; see Figure 4). However, at 12month follow-up, participants in the WHC+ arm were significantly less likely to report emotional abuse from a boyfriend (p = 0.002).

Figure 4.

Proportion of Women Who Reported Frequent Heavy Drinking by Treatment and Time

*Note: P-values represent the differences between groups at each time point based on chi-squared difference tests.

3.3.4. HIV care

Among participants who tested positive for HIV, no statistically significant difference was found in the proportion of participants who attended an appointment for a medical evaluation since their HIV diagnosis between the WHC+ arm and the HCT arm at 6- or 12-month follow-up (all p > 0.05). There was also no statistically significant difference at 6- or 12-month follow-up (all p > 0.05) in the proportion of participants who reported that they had been prescribed ART.

Chi-square tests of independence using the DBS samples indicated that there was no difference in the proportion of participants who had non-detectable viral loads at 6-month follow-up (p = 0.83). However, there was a significant difference at 12-month follow-up (p = 0.01). Approximately 53% of participants in the WHC+ arm (n = 50) had non-detectable viral loads compared with 47% of participants in the HCT arm (n = 45) at 12-month follow-up (n = 172).

3.4. Secondary outcomes

3.4.1. Sexual negotiation

Participants in the WHC+ arm reported significantly more frequent condom negotiation, using a condom while high, and refusing sex without a condom with a boyfriend in the past 3-months at 6-month follow up (all p < 0.05), but not at 12-month follow-up (all p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

Globally, gender inequality puts women at greater risk for HIV, and South Africa is a country where HIV is a gendered issue (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2017b). Furthermore, South Africa has one of the most hazardous patterns of alcohol use, and heavy alcohol use is prevalent among South African women. STTR and TasP hold the promise to eliminate the spread of HIV (World Health Organization, 2012); however, the nexus of AOD use, GBV, sexual risk, and lack of sexual agency may challenge the potential of these strategies. Consequently, these factors must be addressed in concert when trying to reduce the burden of HIV among South African women.

The current study is among the first to test the efficacy of a biobehavioral, gender-focused, empowerment-based HIV prevention intervention that aims to both prevent HIV and increase linkage to HIV care. Our findings suggest that WHC+ intervention was efficacious in improving behavioral outcomes. Participants in the WHC+ arm reported significantly reduced frequent heavy drinking, a greater number of sex episodes with a condom with a boyfriend, and less physical and sexual abuse perpetrated by a boyfriend at 6-month follow-up, as compared with participants in the HCT arm. Similarly, participants in the WHC+ arm reported less emotional abuse by a boyfriend at 12-month follow-up, as compared with participants in the HCT arm. This study also provided some preliminary evidence that the WHC+ may have a positive effect on ART adherence. While most of the outcomes were not significantly different at 12-month follow-up, the data suggest that participants’ risky behavior at follow-up remained lower than their risky behavior at baseline. Nonetheless, it may also be helpful to offer the WHC+ biannually, with a booster session 6-months after the initial intervention.

Overall, these results demonstrate the potential of a brief woman-focused intervention that addresses the nexus of AOD use, GBV, and sexual risk to reduce short-term HIV risk through primary and secondary prevention for wider scale up. The long-term effects of brief interventions should still be explored; however, deterioration should be expected.

The WHC+ offers an opportunity to reach both HIV-negative and women living with HIV who use AODs, as historically this group has been underserved. This study and previous research demonstrate the efficacy of woman-focused interventions to reduce the risks of HIV infection among women who use AODs (Wechsberg et al., 2013a; Wechsberg et al., 2004; Wechsberg et al., 2010b; Wechsberg et al., 2011). The WHC+ could provide a platform to address both HIV prevention and AOD use among women. This is particularly important because AOD use is a key driver of HIV risk in South Africa (Peltzer et al., 2009) and the current protocols for HCT do not include screening or linkage to care for AOD use disorders (Republic of South Africa, 2015). Therefore, the WHC+ may be a modality to help integrate HCT, AOD screening, and linkage to care as well as an intervention that can be used with other prevention tools such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among women in South Africa.

HIV prevention programs, HCT facilities, and substance abuse rehabilitation centers that work with HIV-negative clients and those living with HIV may consider incorporating the WHC+ and other related biological interventions into their activities. In fact, currently, the WHC+ is being incorporated into substance use and healthcare settings (Howard et al., 2017; Wechsberg et al., 2017a). Co-locating services, like the WHC+, that address all these factors with treatment programs may increase access to services for clients as opposed to the current “silo” system of care and programs that is the norm in many healthcare settings. By linking the WHC+ within substance use or healthcare settings and other usual care settings, programs may also find that HIV-negative women and women living HIV may benefit from reduced AOD use, GBV and sexual risk, which may increase the likelihood of accessing HIV care or reduce their risk of HIV, respectively.

This study has important implications for the HIV prevention and treatment cascade for South African women and demonstrates that a brief intervention that addresses multiple contextual factors can lead to behavioral change over a 6-month period. Although South Africa has invested in HIV prevention efforts for women who conduct sex work (The South African National AIDS Council, 2016) and plans are underway for other key populations, these initiatives primarily address sexual risk and health, violence, and economic empowerment to reduce HIV. Rarely has the focus been on AOD use among women, despite the fact that alcohol is the most prevalent substance of abuse and a major contributor to HIV acquisition in South Africa (Kalichman et al., 2007). Additionally, fetal alcohol effects remain a major public health problem (Roozen et al., 2016).

The current study highlights the severity of the HIV epidemic among women who use AODs, as more than 55% of the women in the sample were HIV-positive at enrollment. Furthermore, the findings illustrate that addressing AOD use, GBV, sexual risk, and HIV care simultaneously is feasible and effective. This is important because decreasing the occurrence of HIV risk and increasing engagement in the HIV continuum of care may ultimately lead to lower HIV incidence among women and their partners. Consequently, including women who use AODs in HIV prevention programs is critical, as women represent an essential population in the fight against HIV.

Although these findings have important implications, some limitations should be noted. First, many of the measures were based on self-report. Consequently, there is the possibility of recall error or social desirability. Future studies may benefit from recent advances in ecological momentary assessments that allow for near-real-time data collection and reduce recall error.

Second, all women who tested positive underwent CD4 testing to facilitate clinical staging and were linked to HIV care, regardless of treatment condition. This procedure was aligned with the ethical principles of beneficence, justice, and respect. However, the effects of the WHC+ on linkage to care and prescription of ARVs may have been tempered by this protocol. Relatedly, this study was conducted during a period when the WHO and South African guidelines for the treatment of HIV were changing rapidly. The recent move toward universal treatment in South Africa will make ART more accessible to all persons living with HIV. Consequently, future studies should assess the impact of woman-focused interventions on HIV care and adherence within this new treatment context.

Third, ART adherence was assessed using viral load data from DBS samples from a subsample of women who were living with HIV. Although this method of viral load testing provides accurate information about viral load, this study did not assess the timing of ART initiation or re-initiation. Although viral load typically decreases rapidly after ARVs are initiated, it can take up to 6-months before viral loads become non-detectable in a person initiating an ART regimen, especially if they have trouble adhering (Cohen et al., 2011; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 2017). Consequently, it is possible that some participants who provided DBS samples had newly initiated ART, and therefore their viral loads may not accurately reflect their adherence levels. Relatedly, DBS collection capabilities were not available to the study team during the entire study. We were unable to collect DBS samples at baseline and were only able to collect data from a subsample of participants who completed their 6-month and 12-month follow-up, resulting in small sample sizes of 118 and 172 DBS samples at 6 and 12-month follow-up, respectively. This limits the inferences that can be made about the effectiveness of the WHC+ on adherence. However, it should be noted that even with this small sample size, participants in the WHC+ arm were more likely to have non-detectable viral loads than participants in the HCT arm. This is promising and should be explored further in future studies.

Fourth, while women who use AODs are a population vulnerable to HIV in South Africa and globally, our sample is specific to the Pretoria area. Consequently, these findings may not necessarily be generalizable to other regions of South Africa or other African countries.

Fifth, the interventions in this trial were slightly unequal because of the provision of case management for the WHC+ arm. The HCT arm was provided the standard of care, which usually does not include case management. Consequently, participants in the HCT arm were not provided case management.

Lastly, although the geographic zones were randomized to either the HCT arm or the WHC+ arm, differences still existed between the groups at baseline. Although each pair of clusters was matched based on similar characteristics, some of the zones were markedly different than other zones in terms of the severity of drug use and sex work. Consequently, there were still a few significant differences in conditions, even after randomization. We attempted to address these differences by controlling for baseline measures in the models; however, these differences may still threaten the internal validity of the inferences that can be made based on the results. However, the community-based and real-world nature of this study strengthens the external validity of the findings.

Despite these limitations, the study findings suggest that the WHC+ is an efficacious intervention with the potential to reduce HIV risk behaviors and increase protective behaviors among South African women who use AODs. Based on these findings, substance abuse rehabilitation centers that serve women may be ideal settings to address issues of GBV and sexual risk. Health centers also may be ideal settings to address these multiple risk factors as women test for or are treated for HIV. Given the outcomes at 6months with this brief WHC+ intervention, future research should examine the effectiveness of WHC+ in these real-world settings.

5. Conclusions

It is imperative to move forward in establishing the effectiveness and sustainability of this woman-focused intervention, which has the potential to reduce HIV risk among South African women. The WHC+ also could be a platform to introduce PrEP for women who report risk behaviors and test negative for HIV in public clinics. As more tools are added to the HIV prevention arsenal, all combinations of prevention need to be accessible and implementable.

Highlights.

Approximately 55% of the women in the study were living with HIV.

Women in the Women’s Health CoOp+ (WHC+) were more likely to use a condom.

Women in the WHC+ arm were less likely to engage in frequent heavy drinking.

Women in the WHC+ arm were less likely to report all forms of abuse.

The WHC+ shows promise for increasing adherence to ARVs among women who use AODs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions from the field staff, all of the women who participated in the study, and editorial support from Jeffrey Novey. We would also like to acknowledge the contributions and support of Julie Nelson at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research for assistance.

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse under grant number R01DA032061 (PI: Wendee M. Wechsberg, PhD) and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research P30 AI50410 (PI: Ronald Swanstrom). The funding source had no role in the analysis of the data, in writing the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

According to South African law, adolescents under 18, the age of majority, can provide consent unassisted if they can provide evidence of tacit emancipation. Tacit emancipation occurs when the capacity of a minor to act without parental consent is “enlarged” to encompass certain key areas that will enable him or her to be viewed by the law as a major. The prime consideration is the degree of financial independence that the minor has achieved. In this respect, ownership of a business or an occupation that brings in a salary is key. Residence outside the parental home is regarded as further proof of emancipation. van Heerden, B., Cockrell, A., Keightley, R. (Ed.), 1999. Boberg’s Law of Persons and the Family.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, Altice FL, 2010. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend 112, 178–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, 1994. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection, in: DiClemente RJ (Ed.) Preventing AIDS: Theories and Methods of Behavioral Interventions Plenum Press, New York, NY, pp. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cain D, Pare V, Kalichman SC, Harel O, Mthembu J, Carey MP, Carey KB, Mehlomakulu V, Simbayi LC, Mwaba K, 2012. HIV risks associated with patronizing alcohol serving establishments in South African Townships, Cape Town. Prev. Sci 13, 627–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, group C, 2004. CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 328, 702–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Group C, 2012. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 345, e5661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013. Compendium of evidence-based HIV behavioral interventions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Atlanta, GA https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016. HIV risk among persons who exchange sex for money or nonmonetary items https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/sexworkers.html.

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Hakim JG, Kumwenda J, Grinsztejn B, Pilotto JH, 2011. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N. Engl. J. Med 365, 493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Gay CL, 2010. Treatment to prevent transmission of HIV-1. Clin. Infect Dis 50 Suppl 3, S85–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health, 2014. National consolidated guidelines for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the management of HIV in children, adolescents and adults. Department of Health, Pretoria http://www.Healthgov.za/

- Dunkle K, Jewkes R, Brown H, Gray G, McIntryre J, Harlow S, 2004. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet 363, 1415–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Witte S, Wu E, Chang M, 2011. Intimate partner violence and HIV among drug-involved women: Contexts linking these two epidemics--challenges and implications for prevention and treatment. Subst. Use Misuse 46, 295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JC, Bang H, Kapiga SH, 2007. The association between HIV infection and alcohol use: a systematic review and meta-analysis of African studies. Sex. Transm. Dis 34, 856–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM, 2011. Negative Binomial Regression Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hlomani TJ, 2013. Alcohol use and abuse among female high school learners: A qualitative approach. School of Applied Human Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.887.5773&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Howard BN, Van Dorn R, Myers BJ, Zule WA, Browne FA, Carney T, Wechsberg WM, 2017. Barriers and facilitators to implementing an evidence-based woman-focused intervention in South African health services. BMC Health Serv. Res 17, 746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull MW, Montaner JS, 2013. HIV treatment as prevention: the key to an AIDS-free generation. J. Food Drug Anal 21, S95–s101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Abrahams N, 2002. The epidemiology of rape and sexual coercion in South Africa: An overview. Soc. Sci. Med 55, 1231–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Dunkle K, Khuzwayo N, Koss M, Puren A, Wood K, Duvvury N, 2006. A cluster randomized-controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of Stepping Stones in preventing HIV infections and promoting safer sexual behaviour amongst youth in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa: Trial design, methods and baseline findings. Trop. Med. Int. Health 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N, 2010. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: A cohort study. Lancet 376, 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2014a. 90-90-90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2017/90-90-90

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2014b. Fast-Track - Ending the AIDS Epidemic by 2030 http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/JC2686_WAD2014report

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2017a. Ending AIDS: Progress towards 90-90-90 targets. Geneva, Switzerland http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2017/20170720_Global_AIDS_update_2017.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2017b. UNAIDS Data 2017 http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2017/2017_data_book. [PubMed]

- Kalichman SC, 2010. Social and structural HIV prevention in alcohol-serving establishments: Review of international interventions across populations. Alcohol Res. Health 33, 184–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, White D, Swetsze C, Kalichman MO, Cherry C, Eaton L, 2012. Alcohol and adherence to antiretroviral medications: Interactive toxicity beliefs among people living with HIV. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 23, 511–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Grebler T, Amaral CM, McNerey M, White D, Kalichman MO, Cherry C, Eaton L, 2013. Intentional non-adherence to medications among HIV positive alcohol drinkers: Prospective study of interactive toxicity beliefs. J. Gen. Intern. Med 28, 399–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S, 2007. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci 8, 141151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobin AB, Sheth NU, 2011. Levels of adherence required for virologic suppression among newer antiretroviral medications. Ann. Pharmacother 45, 372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez EJ, Jones DL, Villar-Loubet OM, Arheart KL, Weiss SM, 2010. Violence, coping, and consistent medication adherence in HIV-positive couples. AIDS Educ. Prev 22, 61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luseno WK, Wechsberg WM, Kline TL, Ellerson RM, 2010. Health services utilization among South African women living with HIV and reporting sexual and substance-use risk behaviors. AIDS Patient Care STDS 24, 257–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Passin WF, Kim AS, Rama SM, Thadiparthi S, DeLuca JB, Mullins MM, 2007. Best-evidence interventions: Findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. Am. J. Public Health 97, 133–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Mbwambo JK, Hogan NM, Kilonzo GP, Campbell JC, Weiss E, Sweat MD, 2002. HIV-positive women report more lifetime partner violence: Findings from a voluntary counseling and testing clinic in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Am. J. Public Health 92, 1331–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medley A, Seth P, Pathak S, Howard AA, DeLuca N, Matiko E, Mwinyi A, Katuta F, Sheriff M, Makyao N, 2014. Alcohol use and its association with HIV risk behaviors among a cohort of patients attending HIV clinical care in Tanzania, Kenya, and Namibia. AIDS Care 26, 1288–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekuria LA, Prins JM, Yalew AW, Sprangers MA, Nieuwkerk PT, 2017. Sub-optimal adherence to combination anti-retroviral therapy and its associated factors according to self-report, clinician-recorded and pharmacy-refill assessment methods among HIV-infected adults in Addis Ababa. AIDS Care 29, 428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JP, Springer SA, Altice FL, 2011. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: A literature review of the syndemic. J. Womens Health 20, 991–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers B, Louw J, Pasche S, 2011. Gender differences in barriers to alcohol and other drug treatment in Cape Town, South Africa: Original. Afr. J. Psychiatry (Johannesbg) 14, 146–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 2017. 10 Things to Know About HIV Suppression https://www.niaid.nih.gov/news-events/10-things-know-about-hiv-suppression.

- Ndirangu J, Wechsberg WM, Zule W, Kine T, Doherty I, van der Hosrt C, 2014. Methods for increasing access and ARV retention among sex workers and drug using women in Pretoria, South Africa: Structural and individual determinants, Satellite Session of the International AIDS Conference. Melbourne, Australia http://pag.aids2014.org/PAGMaterial/PPT/5429_10978/final.pptx

- Parry CD, Pithey AL, 2006. Risk behaviour and HIV among drug using populations in South Africa. Afr J Drug Alcohol Stud 5, 140–157. [Google Scholar]

- Parry CD, Pluddemann A, Steyn K, Bradshaw D, Norman R, Laubscher R, 2005. Alcohol use in South Africa: Findings from the first Demographic and Health Survey (1998). J. Stud. Alcohol 66, 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellowski JA, Kalichman SC, Kalichman MO, Cherry C, 2016. Alcohol-antiretroviral therapy interactive toxicity beliefs and daily medication adherence and alcohol use among people living with HIV. AIDS Care 28, 963–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Simbayi L, Kalichman S, Jooste S, Cloete A, Mbelle N, 2009. Drug use and HIV risk behaviour in three urban South African communities. J. Soc. Sci 8, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Pitpitan EV, Kalichman SC, Eaton LA, Cain D, Sikkema KJ, Watt MH, Skinner D, Pieterse D, 2013. Co-occurring psychosocial problems and HIV risk among women attending drinking venues in a South African township: A syndemic approach. Ann. Behav. Med 45, 153–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitpitan EV, Kalichman SC, Eaton LA, Sikkema KJ, Watt MH, Skinner D, 2012. Gender-based violence and HIV sexual risk behavior: Alcohol use and mental health problems as mediators among women in drinking venues, Cape Town. Soc. Sci. Med 75, 1417–1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Republic of South Africa, 2010. National HIV counselling and testing policy guidelines Health D.o. (Ed.). https://aidsfree.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/hts_policy_south-africa.pdf

- Republic of South Africa, 2015. National HIV Counselling and Testing Policy Guidelines, in: Health D.o. (Ed.). https://aidsfree.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/hts_south_africa_2015.pdf

- Roozen S, Peters GJ, Kok G, Townend D, Nijhuis J, Curfs L, 2016. Worldwide prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: a systematic literature review including meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res 40, 18–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, Montgomery B, Williams CT, El-Bassel N, Aramrattana A, Metzger DS, Kuo I, Bastos FI, Strathdee SA, 2013. Not just the needle: The state of HIV prevention science among substance users and future directions. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 63, S174–S178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovdal M, Campbell C, Nyamukapa C, Gregson S, 2011. When masculinity interferes with women’s treatment of HIV infection: A qualitative study about adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Zimbabwe. J. Int. AIDS Soc 14, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Stockman JK, 2010. Epidemiology of HIV among injecting and non-injecting drug users: Current trends and implications for interventions. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep 7, 99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The South African National AIDS Council, 2016. The South African national sex worker HIV plan 2016–2019. South Africa http://sanac.org.za/2016/03/29/south-african-national-sex-worker-hiv-plan2016-2019/.

- Townsend L, Jewkes R, Mathews C, Johnston LG, Flisher AJ, Zembe Y, Chopra M, 2011. HIV risk behaviours and their relationship to intimate partner violence (IPV) among men who have multiple female sexual partners in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav 15, 132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USAID, 2009. Integrating multiple gender strategies to improve HIV and AIDS interventions: A compendium of programs in Africa. International Center for Research on Women, Geneva, Switzerland https://aidsfree.usaid.gov/resources/integrating-multiple-gender-strategies-improvehiv-and-aids-interventions-compendium.

- van Heerden B, Cockrell A, Keightley R (Ed.), 1999. Boberg’s Law of Persons and the Family [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, 1998. Facilitating empowerment for women substance abusers at risk for HIV. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 61, 158. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Browne FA, Ellerson RM, Zule WA, 2010a. Adapting the evidence-based Women’s CoOp intervention to prevent human immunodeficiency virus infection in North Carolina and international settings. N. C. Med. J 71, 477–481. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Jewkes R, Novak SP, Kline T, Myers B, Browne FA, Carney T, Morgan Lopez AA, Parry C, 2013a. A brief intervention for drug use, sexual risk behaviours and violence prevention with vulnerable women in South Africa: A randomised trial of the Women’s Health CoOp. BMJ Open 3, e002622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Lam WKK, Zule WA, Bobashev G, 2004. Facilitating empowerment for African-American women who use crack cocaine: Efficacy of a woman-focused, culturally specific intervention to reduce risk for HIV and increase self-sufficiency. Am. J. Public Health 94, 1165–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Luseno WK, Kline TL, Browne FA, Zule WA, 2010b. Preliminary findings of an adapted evidence-based woman-focused HIV intervention on condom use and negotiation among at-risk women in Pretoria, South Africa. J. Prev. Interv. Community 38, 132–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Luseno WK, Lam WK, 2005. Violence against substance-abusing South African sex workers: Intersection with culture and HIV risk. AIDS Care 17 Suppl 1, S55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Luseno WK, Lam WK, Parry CD, Morojele NK, 2006. Substance use, sexual risk, and violence: HIV prevention intervention with sex workers in Pretoria. AIDS Behav 10, 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Myers B, Kline TL, Carney T, Browne FA, Novak SP, 2012. The relationship of alcohol and other drug use typologies to sex risk behaviors among vulnerable women in Cape Town, South Africa. J. AIDS Clin. Res. Suppl 1, 015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Myers B, Reed E, Carney T, Emanuel AN, Browne FA, 2013b. Substance use, gender inequity, violence and sexual risk among couples in Cape Town. Cult. Health Sex 15, 1221–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Ndirangu JW, Speizer IS, Zule WA, Gumula W, Peasant C, Browne FA, Dunlap L, 2017a. An implementation science protocol of the Women’s Health CoOp in healthcare settings in Cape Town, South Africa: A stepped-wedge design. BMC Womens Health 17, 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Peasant C, Kline T, Zule WA, Ndirangu J, Browne FA, Gabel C, van der Horst C, 2017b. HIV prevention among women who use substances and report sex work: Risk groups identified among South African women. AIDS Behav 21, 155–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, van der Horst C, Ndirangu J, Doherty IA, Kline T, Browne FA, Belus JM, Nance R, Zule WA, 2017c. Seek, test, treat: Substance-using women in the HIV treatment cascade in South Africa. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract 12, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Zule WA, Luseno WK, Kline TL, Browne FA, Novak SP, Ellerson RM, 2011. Effectiveness of an adapted evidence-based woman-focused intervention for sex workers and non-sex workers: The Women’s Health CoOp in South Africa. J. Drug Issues 41, 233–252. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2005. Blood Collection and Handling – Dried Blood Spot (DBS) Module 14 http://www.who.int/diagnostics_laboratory/documents/guidance/pm_module14.pdf.

- World Health Organization, 2012. Programmatic update: antiretroviral treatment as prevention (TasP) of HIV and TB. Geneva: World Health Organization http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70904.