Abstract

Introduction:

Nanoproteomics, which is defined as quantitative proteome profiling of small populations of cells (<5000 cells), can reveal critical information related to rare cell populations, hard-to-obtain clinical specimens, and the cellular heterogeneity of pathological tissues.

Areas covered:

We present a brief review of the recent technological advances in nanoproteomics. These advances include new technologies or approaches covering major areas of proteomics workflow ranging from sample isolation, sample processing, high-resolution separations, to MS instrumentation.

Expert commentary:

We comment on the current state of nanoproteomics and discuss perspectives on both future technological directions and potential enabling applications.

Keywords: Nanoproteomics, small cell populations, single cell proteomics, spatially resolved, nanoPOTS, laser capture microdissection

1. Introduction

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics has become the method of choice to identify proteins and quantify the dynamic changes in the levels of protein expression and post-translational modifications (PTM) in complex biological systems in a global fashion [1]. Fueled by rapid technological advances in both instrumentation and informatics during the past decade, MS-based proteomics has enabled deep quantitative profiling of ~10,000 proteins for human tissues and has greatly expanded our understanding of signaling, regulatory, and metabolic pathways [2]. However, most proteomics studies to date are based on bulk analyses of cell lysates or tissue homogenates from large populations of cells (e.g., >1 million cells), thus masking critical information related to cell-type specificity and cellular heterogeneity of cells and biological tissues. The applications of MS-based proteomics to rare cell populations—such as circulating tumor cells, fine needle aspiration biopsies, and substructures within heterogeneous tissues—has been largely restricted.

During the past decade, substantial technological advances have been made towards enabling a “nanoproteomics” capability, i.e., proteomics analyses of small cell populations. The term “nanoproteomics” was recently defined as proteomics analysis of small cell populations ranging from single cells to populations of cells that will result in a total protein amount less than 1 μg [3,4]. Assuming a typical mammalian cell containing ~0.2 ng of proteins, nanoproteomics deals with any types of samples equivalent to <5,000 mammalian cells. Since the first several reports nearly a decade ago [5,6], nanoproteomics has undergone significant advances from sample isolation and processing, separations, MS detection, to data analysis. Confident identification and quantification of over 3000 proteins was recently demonstrated for as few as 10 mammalian cells containing <2 ng of protein [7]. Single cell proteomics with a coverage of ~700 proteins has also been reported utilizing a similar approach [8]. These advances demonstrate a rapid maturation of nanoproteomics technologies, which are now poised to transform biological and biomedical research. Herein, we present a brief appraisal of the state of nanoproteomics, discuss the remaining technological challenges, and offer future perspectives on both technological advances and potential applications.

2. Challenges in nanoproteomics

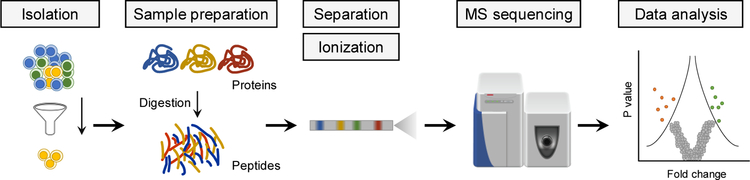

Unlike genomics and transcriptomics, there is no whole-proteome amplification approach available for proteins. Thus, one of the most critical factors for nanoproteomics is the overall achievable sensitivity of the proteomics workflow, which in turn depends on two main factors: (1) the efficiency and recovery of proteomic sample processing and (2) the sensitivity along with spectrum-acquisition speed of the MS platform. In a typical bottom-up proteomics workflow (Figure 1), proteins are extracted from cells, reduced, alkylated, and finally digested into peptides. During this process, non-specific sample losses to surfaces such as container walls significantly limit the overall sensitivity for nanoproteomics although such losses are rarely detrimental for large sample inputs. To achieve an in-depth proteome coverage, the sensitivity of the typical liquid chromatography (LC)-MS platform is also a limiting factor, especially for single cell proteomics. In addition to proteome coverage, the reproducibility and robustness of analyses between replicates is also critical for reliable quantification. Finally, to gain understanding of cellular heterogeneity at single cell or near single cell levels, the analysis of a larger number of samples is often required, and the sample throughput of the nanoproteomics platform is also a significant challenge. For example, single cell omics studies commonly analyze hundreds to thousands of cells to reveal cell subtypes by statistical analysis. Spatially resolved proteome mapping of heterogeneous tissue sections require analysis of hundreds of spots with high spatial resolution. However, the current LC-MS/MS platform (with a typical 10−25 cm long LC column) typically requires at least 1 hour to analyze a single sample. This throughput is insufficient for large scale nanoproteomics studies.

Figure 1. Typical workflow for bottom-up nanoproteomics.

Briefly, specified cell population is isolated from tissues or cultured cells. Proteins are extracted and digested by proteolytic enzymes (e.g., trypsin) into peptides. The digested samples are analyzed by nanoflow LC or capillary electrophoresis (CE) coupled with MS through electrospray ionization. Peptide sequences are identified from MS/MS spectra through database searching, and MS intensity information is typically utilized for protein quantification.

3. Advances in analytical platforms

Protein digests are typically analyzed by LC or CE coupled with MS through an electrospray ionization (ESI) interface. Advances in the sensitivity of LC or CE-MS platforms are critical in the overall performance of nanoproteomics.

The sensitivity of LC-MS platform generally depends on the LC flow rate, the resolution of the separation, and the ionization efficiency of an ESI source in addition to MS instrumentation itself. One of the foundational discoveries in ESI-MS was that ionization efficiency can be dramatically enhanced by nearly ~100-fold when ESI was operated at low flow rate (20–40 nL/min) (i.e., nanoESI) compared to conventional flow rate (>1 µl/min)) [9–11]. To enable nanoflow LC without compromising separation resolution, the inner diameter (i.d.) of the LC column is often decreased to maintain optimal linear flow rate. In 2004, Shen et.al. [12] demonstrated that sensitivity of proteomic analyses can be significantly improved by decreasing column i.d. from 75 μm to 15 μm, corresponding to reducing flow rates from 300 nL/min to 20 nL/min. A detection limit of 10 zmol (~6000 molecules) was reported using BSA tryptic digest as a model sample. In a more recent study, we demonstrated a coverage of 965 proteins from 500 pg bacterial digest using a 30-μm LC column coupled to an LTQ-Orbitrap MS [13]. To mitigate the challenge of packing small i.d. columns, Ivanov and coworkers [14] developed porous layer open tubular (PLOT) columns with an i.d. of 10 μm and a flow rate of 20 nL/min. When coupled to a Q-Exactive MS, the PLOT column led to detection limits of 10 zmol for a standard digested protein mix. In addition to LC-MS, capillary zone electrophoresis (CZE)-MS has been employed as an alternative method for ultrasensitive detection. Sun et.al. [15] developed an electrokinetically pumped sheath–flow interface to couple high resolution CZE separation with ESI-MS for proteomics studies. The new interface efficiently minimized sample dilution and led to identification of >60 proteins from just 400 fg of protein digest, corresponding to a detection limit of 1 zmol.

In addition to the progress in separations and ESI, dramatic advances in MS instrumentation during the past decade has been an essential factor for enabling nanoproteomics. One of the most significant advances in MS instrumentation was the invention and commercialization of the Orbitrap analyzer [16]. Orbitrap detect ions by measuring image current and then employing Fourier transformation for data processing, which is similar to Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) mass analyzer. However, Orbitrap utilizes electrical fields to manipulate ions rather than magnetic fields as with FT-ICR, dramatically reducing the size and cost of the instrument, leading to widespread adoption by the proteomics community. The detection limit of Orbitrap is determined by internal preamplifier noise, which is approximate 2−4 elementary charges in a 1 s acquisition. Such low noise level has made possible single molecule detection of intact proteins, including myoglobin [17] and E. coli GroEL [18]. In addition to the mass analyzer, front-end ion transmission optics have also been substantially improved. One of the most important improvements is the development of the ion funnel [19], which sought to efficiently transfer ions from the first vacuum stage to the high vacuum of the ion detector. The ion funnel employs a stacked radio frequency ring electrode arrangement in a funnel shape to focus ions. Nearly 1 order of magnitude gain in sensitivity relative to a standard skimmer device was achieved [20]. When combined with a low-flow sub-ambient pressure ionization source (SPIN) [21], 50% of the analyte ions initially in the solution can be delivered into high vacuum mass detector [22], representing the highest overall ion utilization efficiency yet achieved.

Finally, advances in data analysis algorithms provide another avenue to improve the sensitivity of proteome identification and quantitation. In a typical proteomics workflow, peptides are identified by tandem MS spectra, where individual peptides are isolated and dissociated, followed by fragment measurement and database searching. However, the stochastic sampling nature limits the ability to achieve broad proteome coverage because many detectable molecules may never be sampled for fragmentation due to the overall low sampling efficiency for fragmentation. Several advances have been made to address this limitation through informatics algorithms. For example, Smith and coworkers [23] initially reported the accurate mass and time (AMT) tag concept that peptides can be identified by matching accurately measured masses and retention times to a pre-established peptide AMT database. The database was typically generated by two-dimensional LC-MS/MS analyses of the proteome samples. This concept has been further adopted into the more broadly disseminated MaxQuant software with integrated match between runs (MBR) algorithm [24] as well as the recently reported IonStar approach [25]. Our recent results demonstrated ~1000 proteins can be identified from 0.5 ng tryptic digest of S. oneidensis using MBR algorithm [13].

Taken together, these advances suggest that current analytical sensitivity of LC-MS or CE-MS platforms is sufficient to make proteome-level measurements even in single mammalian cells containing subnanogram amounts of protein.

4. Minimizing loss during proteomic sample processing

With the great progress in advancing analytical sensitivity, the next grand challenge is how to maximize sample recovery of proteomic sample processing. Initial efforts suggested that MS incompatible surfactants, acetone precipitation, and multi-step transfers should be avoided to reduce the sample losses to vessel surfaces or cleanup steps [5,6]. Additionally, sufficient protein and enzyme concentrations are required in order to achieve efficient tryptic digestion. Considerable efforts have been recently devoted into developing new sample preparation systems for nanoproteomics, including online processing systems [26–31], single tube preparation systems [6,14,32,33], and a microfluidic nanodroplet processing system (Table 1) [7,8,34].

Table 1.

A summary of nanoproteomics performance with different sample preparation methods along with LC-MS platforms

| Sample preparation method | Analytical systems | Minimal sample size | Protein identifications | Publication year and Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetone precipitation | 75 μm × 100 mm C18 LC, QTOF Premier MS | 500 MCF-7 cells | 187 | 2010, [5] |

| Proteomic reactor | 75 μm × 50 mm C18 LC, LTQ ion trap MS | 300 P19 testicular cancer cells | 17 | 2006, [26] |

| Proteomic reactor | 50 μm × 200 mm C18 LC, LTQ-Orbitrap XL MS | 500 embryonic stem cells | 68 | 2011, [27] |

| Spintip-based proteomic reactor | 75 μm × 200 mm C18 LC, Orbitrap Fusion MS | 2000 HEK 293 cells | 1270 | 2016, [28] |

| Immobilized enzyme reactor | 50 μm × 750 mm C18 LC, Q-Exactive plus MS | 500 mouse lung alveoli cells | 652 | 2016, [31] |

| PPS Silent Surfactant-based single tube preparation | 40 μm × 220 mm C18 LC, LTQ-Orbitrap MS | single pancreatic islets (~2000 cells) |

2013 | 2009, [32] |

| TFE-based single tube preparation | 150 μm × 650 mm C18 LC, 11 T FTICR MS | 5000 MCF-7 | 224 | 2005, [6] |

| Focused ultrasonication-based single tube preparation | 10 μm × 400 cm C18 PLOT LC, Q-Exactive MS | 1000 MCF-7 | 2512 | 2015, [14] |

| On-valve single tube digestion system | 75 μm × 100 mm C18 LC, Q-Exactive MS | 100 DLD cells | 635 | 2015, [33] |

| Single-pot solid-phase-enhanced sample preparation | 75 μm × 300 mm C18 LC, Q-Exactive MS | Single Drosophila embryo (~200 ng total proteins) | 2937 | 2014, [37] |

| Nanodroplet-based preparation system | 30 μm × 600 mm C18 LC, Fusion Lumos MS | 10 HeLa cells | 3092 | 2018, [7] |

| LCM and nanodroplet-based preparation | 30 μm × 600 mm C18 LC, Fusion Lumos MS | ~100 cells from single pancreatic islet section | 2676 | 2018, [7] |

| FACS and nanodroplet-based preparation system | 30 μm × 600 mm C18 LC, Fusion Lumos MS | 1 HeLa cells | 669 | 2018, [8] |

| LCM and urea-based single tube preparation | 75 μm × 500 mm C18 LC, Orbitrap Fusion MS | 0.5 mm2 mouse kidney tissue | 3440 | 2016, [41] |

| in situ droplet digestion | 50 μm × 150 mm C18 LC, Q-Exactive MS | 0.25 mm in diameter of rat brain tissue | 515 | 2017, [42] |

| in situ hydrogel digestion | 75 μm × 250 mm C18 LC, Orbitrap Fusion MS | 0.26 mm in diameter of rat liver tissue | 671 | 2017, [43] |

Two types of online proteomic processing systems have been developed. The first is based on a strong cation exchange (SCX) capillary column, termed as a proteomic reactor [26]. Cell lysates were directly loaded, and proteins were trapped in the SCX capillary. Protein denaturation, alkylation, and tryptic digestion were performed by serially introducing reagents into the SCX column [26,27]. Proteome profiling of 17 and 68 proteins from 300 mouse P19 testicular cancer cells [26] and 500 human embryonic stem cells [27] were reported, respectively. To improve the sample throughput of the proteomic reactor approach, Tian and coworkers [28] prepared the SCX columns in pipette tips and introduced reagents by centrifugation, allowing multiple samples to be processed in parallel. The second type of online processing system was based on an immobilized enzyme reactor (IMER), where proteins were directly loaded and digested in an IMER column [29]. Huang et.al. [30] reported a simplified nano-proteomics platform (SNaPP), which consisted of an online IMER digestion system and a solid phase extraction (SPE) column coupled with a nanoLC separation system. SNaPP was applied for proteome profiling for as few as 500 mouse lung alveoli cells isolated by laser capture microdissection (LCM) [31]. Although online processing systems have greatly increased the preparation efficiency and simplified experimental operations, sample loss on the surfaces of SCX or IMER beads is still a significant factor precluding the effective analysis of smaller cell population (e.g., <500 cells).

Single tube preparation is an interesting concept to minimize surface exposure by performing all procedures in a single centrifugation tube or vial. Low binding tubes or plates (e.g., Eppendorf Protein LoBind) were commonly used. To facilitate efficient cell lysis and protein extraction, numerous modified procedures and alternative surfactants have been introduced. For instance, MS and trypsin-compatible surfactants—such as RapiGest, ProteaseMAX, PPS Silent Surfactant, and sodium deoxycholate—were introduced to replace sodium dodecyl sulfate and avoid extra cleanup steps. Waanders et. al. [32] described a PPS Silent Surfactant-based workflow for proteomic profiling of single pancreatic islets containing 2,000–4,000 cells. To avoid the use of detergent, Wang et al. [6] reported a trifluoroethanol (TFE)-based approach where the volatile organic solvent TFE facilitates efficient protein extraction and denaturation from cells or tissues. This TFE approach was demonstrated for proteome profiling of 5000 MCF-7 cells. The Ivanov group [14] introduced focused ultrasonication for cell lysis and protein extraction. When coupling with ultrasensitive PLOT LC, 2512 proteins were identified by injecting an aliquot equivalent to 122 cells taken from a single tube preparation of 1000 MCF-7 cells. The focused ultrasonication approach was applied to measure protein expression in single mammalian cells [35]. To improve proteome coverage of single cell samples, a signal boost concept was introduced, where one tandem mass tag (TMT) labeled channel that contains a large amount of reference sample served as a signal boost to trigger MS/MS and to enable detect low abundance species in other single cell channels [35,36]. A total of 767 proteins were quantified across a group of 24 single cells, which could be clustered by cell types in a two-dimensional principal component analysis plot. Chen et. al. [33] developed a single tube preparation system based on on-valve tryptic digestion, termed the integrated proteome analysis device (iPAD). Living cells were injected into an on-valve sample loop together with trypsin solution. Cells were lysed, and proteins were digested by heating the loop at an elevated temperature of 50 °C. Generated peptides were purified by online SPE column and identified by LC-MS. An average of 635 proteins were identified from 100 DLD cancer cells. The Krijgsveld group [37,38] developed a single-pot, solid-phase-enhanced sample preparation (SP3) method, where hydrophilic paramagnetic beads were used to trap proteins and peptides during multiple-step sample processing. A unique advantage of the SP3 method is that it allows the use of strong detergents for protein extraction and organic solvent for sample clean-up. The performance of SP3 for nanoproteomics was evaluated in the analysis of single Drosophila embryo, and 2937 proteins were identified [37]. In the above-mentioned single tube approaches, low reaction volumes from 3.2 μL to 25 μL were commonly used to minimize total surface exposure, which suggested a new direction to improve sample recovery.

Despite of all these advances in minimizing sample loss during processing, it is still challenging for effective processing of very small cell populations (e.g., <100 cells) without significant loss. We recently achieved a major breakthrough in developing a microfluidics-based sample preparation system, termed as nanodroplet Processing in One-pot for Trace Samples (nanoPOTS) [7]. NanoPOTS significantly reduced adsorptive sample losses to surfaces by minimizing processing volumes to <200 nL in microfabricated nanowells with diameter of only 1 mm. Compared with typical 100-μL sample preparation in microcentrifuge tubes, nanoPOTS reduced total surface area exposure by 99.5% [7]. Meanwhile, nanoliter reaction volumes increased both concentrations of proteins and trypsin, thus greatly enhancing enzymatic digestion kinetics. When coupled with an ultrasensitive LC-MS system (30-μm-i.d. nanoLC, Orbitrap Fusion Lumos), nanoPOTS enabled quantitative profiling of ~3000 proteins from 10 HeLa cells by incorporating the MBR algorithm of MaxQuant and ~2400 proteins from single human pancreatic islet thin sections isolated from clinical specimen from human donors [7]. In a follow-up study, we further demonstrated the identification of 770 proteins from single HeLa cells using this system [8].

5. Sample isolation techniques for nanoproteomics

To enable broad applications of nanoproteomics, successful integration of sample isolation techniques with nanoproteomics workflows will be critical. Currently, there are two commonly used sample isolation techniques for small cell populations: fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) and LCM, which have been coupled effectively to nanoproteomics. In a FACS system, cells can be precisely counted and collected for quantitative analysis, including single cell analysis. We have demonstrated FACS can precisely isolate single mammalian cells and minimize protein contamination for highly sensitive nanoPOTS-based proteomic analysis [8]. The FACS-based sample isolation method has also been employed to purify small numbers of colon stem cells from mouse intestines for proteomic characterization [39]. Using only 5000 sorted cells, the authors observed 21% of stem cell-specific genes could be detected at protein level. Despite the advantages, FACS has inherent limitations for analysis of solid tissues because enzymatic dissociation step is required to generate sortable individual cells, thus inevitably losing the spatial information of the tissue sample. Thus, critical molecular information relating to the tissue microenvironment, heterogeneity, and cell-to-cell interactions is mostly lost. Moreover, the cell proteome may alter during the tissue dissociation steps, thus not actually reflecting the in situ proteome.

LCM offers a particularly useful alternative for in situ and spatially resolved analyses of tissue samples [40]. By combing optical microscopy with laser ablation, it enables the precise isolation of specific cell types or tissue microstructures based on morphology, autofluorescence, antibody staining, or MS imaging. McDonnell and coworkers [41] employed LCM to isolate mouse kidney cortex and medulla microdissections as small as 0.5 mm2. A total of 3440 proteins were identified, and statistically significant protein expression differences were revealed. We also coupled LCM with nanPOTS to analyze single human islet sections obtained from a non-diabetic donor and a type 1 diabetes (T1D) donor [7]. Furthermore, automated sample transfer of LCM isolates to nanoPOTS was achieved through prepopulating nanowells with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and spatially resolved proteome mapping of rat brain cortex tissue was demonstrated [34].

In addition to LCM, in situ protein digestion approaches have also been developed for spatially resolved proteomic analysis of tissue sections [42,43]. In these approaches, small trypsin droplets [42] or hydrogels [43] were directly applied on tissue sections to digest proteins into peptides. The peptide samples were either directly injected into LC or recovered for subsequent analysis. Approximately 500–600 proteins could be identified by sampling small tissue areas with diameters of 250–260 μm.

6. Expert commentary

An effective nanoproteomics and single cell proteomics capability holds tremendous potential for biomedical research by enabling in-depth characterization of cellular heterogeneity, spatially resolved proteome mapping of pathological tissues (i.e., highly multiplexed molecular pathology), the generation of foundational protein atlas for organs and tissues, and the discovery of cell subtypes and novel signatures for specific cell populations. While other single cell technologies have already made significant strides into revealing novel molecular information about the great heterogeneity of cell populations and rare cells [44,45], nanoproteomics for a long time has been considered infeasible for practical applications. However, the aspiration of nanoproteomics down to even the single cell level has come a long way built upon the dramatic advances in nearly all facets of the overall proteomics workflow. The state of nanoproteomics is now a reality for enabling effective quantitative analyses of very few cells (e.g., 10–100 cells) with technologies such as nanoPOTS coupled with advanced LC-MS platforms [7]. The current nanoproteomics technologies are poised to enable broad biomedical applications.

Despite the promising aspects of nanoproteomics, there are still a number of challenges that need to be addressed in the near future in order to realize the full impact of nanoproteomics or single cell proteomics capabilities. First, the absolute sensitivity of the current workflows is still insufficient to obtain in-depth coverage for single cell proteomics although prototype measurements of single cells have been reported [8]. It is possible that the continued advances in MS instrumentation would provide further enhancement in sensitivity needed for single cell proteomics. Second, the current sample throughput for nanoproteomics is a major limitation since a typical LC-MS/MS analysis takes at least 1 hour. Much higher throughput will be necessary for single cell proteomics or other applications involving spatially resolved proteome mapping or imaging of heterogeneous tissues. There are several potential avenues to improve the overall sample throughput. First, the concept of multiplexing labeling, such as TMT-based isobaric labeling or even hyperplexing (e.g., 50- or 100-plex) labeling, might greatly enhance the overall throughput for nanoproteomics or single cell proteomics; however, the accuracy of quantification of such methods will be an important concern due to the potential co-eluting peptide species within the same mass isolation window for MS/MS fragmentation. Second, the continued advances in MS acquisition speed in the newer generation of instrumentation could allow much shorter LC separations to be employed (e.g., 5–10 min). Finally, advances in ultrafast gas phase separations such as structure of lossless ion manipulation (SLIM)-based ion mobility spectrometry may enable much faster separations in nanoproteomics applications [46].

Another important aspect of future nanoproteomics is the potential of performing top-down proteomics at the near single cell level. Most current technological advances are focused on bottom-up nanoproteomics; the extension of nanoproteomics to top-down and PTM measurements still lags significantly behind. In principle, top-down proteomics directly analyzes intact proteins, allowing much better characterization of proteoforms and combinatory PTMs. Protein PTMs (e.g., phosphorylation, acetylation, or glycosylation) are highly significant in the regulation of protein function and are involved in a large variety of biological processes such as enzymatic activity, signal transduction, and gene expression regulation. However, top-down and PTM proteomics pose even greater analytical challenges for nanoscale samples than typically global bottom-up proteomics. For example, compared with digested peptides, over 100-time signal reduction is commonly observed for intact proteins due to low ionization and transmission efficiency in ESI source, multiple-charged precursors, and complex proteoforms [47]. In PTM proteomics, modified peptides usually presented in low abundance and low stoichiometry together. Additional enrichment steps are required to purify PTM peptides for MS detection. Low sample recovery was observed in these enrichment steps for nanoscale samples [48]. Despite these challenges, given the great importance of top-down and PTM proteomics, increasing research efforts and more technological advances are anticipated for these areas.

7. Five-year view

Nanoproteomics is still in its early stage of enabling broad biomedical applications. In the next 5 years, we anticipate both the continued technological advances in this field, but also much broader biological and biomedical applications in the areas of nanoproteomics for analyzing small cell populations, single cells, and spatially resolved proteome mapping of tissues of both normal and disease subjects. In the technological aspects, substantial progress in both sensitivity and throughput is anticipated for the nanoproteomics workflow, and true single cell proteomics technologies may become reality, similar to those in single cell RNA sequencing. We anticipate more technical developments will be focused on top-down and PTM proteomics to improve the overall sensitivity of intact proteins and modified peptides. We would anticipate that vast amounts of detailed novel proteomic information regarding cellular heterogeneity, subpopulations of cells, and spatial organization will be revealed by the enabling technologies. The integration of proteome, genome, and transcriptome data will allow us to gain much better understanding of the molecular underpinning of cellular heterogeneity in normal physiology and pathophysiology. Finally, we anticipate the nanoproteomics capability will be extended to analyzing cell-type-specific and spatially resolved PTMs across heterogeneous tissue to advance our knowledge of signal transduction pathways.

Key Issues.

The sample recovery during processing and the sensitivity of LC or CE-MS platforms are the two most critical factors for nanoproteomics.

Substantial advances have been made in analytical platforms, and the current advanced LC or CE-MS platforms have sufficient sensitivity for single cells.

The main bottleneck for nanoproteomics is actually the loss of proteins or peptides on the various vessel surfaces during sample processing.

The development of the NanoPOTS platform represents a major breakthrough in processing extremely small numbers of cells or single cells by achieving high processing efficiency and recovery through the nanodroplet-based procedure.

Future advances in sensitivity and throughput will make nanoproteomics or single cell proteomics a much more powerful technology for enabling broad biomedical applications.

Funding

This paper was in part supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health: UC4 DK104167, DP3DK110844, R21EB020976, and R33CA225248.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

* of interest

** of considerable interest

- 1.Aebersold R, Mann M. Mass-spectrometric exploration of proteome structure and function. Nature 2016;537:347–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mann M, Kulak NA, Nagaraj N, et al. The Coming Age of Complete, Accurate, and Ubiquitous Proteomes. Mol. Cell 2013;49:583–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen Y, Tolić N, Masselon C, et al. Nanoscale proteomics. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2004;378:1037–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yi L, Piehowski PD, Shi T, et al. Advances in microscale separations towards nanoproteomics applications. J. Chromatogr. A 2017;1523:40–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang N, Xu M, Wang P, et al. Development of mass spectrometry-based shotgun method for proteome analysis of 500 to 5000 cancer cells. Anal. Chem 2010;82:2262–2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.*.Wang H, Qian W-J, Mottaz HM, et al. Development and evaluation of a micro- and nanoscale proteomic sample preparation method. J. Proteome Res 2005;4:2397–2403.The first report of nanoproteomics by analyzing 5000 mammalian cells using a single-tube technique.

- 7.**.Zhu Y, Piehowski PD, Zhao R, et al. Nanodroplet processing platform for deep and quantitative proteome profiling of 10–100 mammalian cells. Nat. Commun 2018;9:882.Demonstrated a dramatical enhancement of overall proteomic sensitivity by reducing the processing volumes to nanoliters using nanodroplet-based sample preparation.

- 8.*.Zhu Y, Clair G, Chrisler WB, et al. Proteomic Analysis of Single Mammalian Cells Enabled by Microfluidic Nanodroplet Sample Preparation and Ultrasensitive NanoLC-MS. Angew. Chemie Int Ed. 2018;57:12370–12374.Single cell proteomics was demonstrated with a moderate coverage.

- 9.Schmidt A, Karas M, Dülcks T. Effect of different solution flow rates on analyte ion signals in nano-ESI MS, or: When does ESI turn into nano-ESI? J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2003;14:492–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilm MS, Mann M. Electrospray and Taylor-Cone theory, Dole’s beam of macromolecules at last? Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Process 1994;136:167–180. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilm M, Mann M. Analytical Properties of the Nanoelectrospray Ion Source. Anal. Chem 1996;68:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.*.Shen Y, Tolić N, Masselon C, et al. Ultrasensitive Proteomics Using High-Efficiency On-Line Micro-SPE-NanoLC-NanoESI MS and MS/MS. Anal. Chem 2004;76:144–154.Demonstration of detection limit of 10 zmol proteins using 15 μm LC column.

- 13.Zhu Y, Zhao R, Piehowski PD, et al. Subnanogram proteomics: Impact of LC column selection, MS instrumentation and data analysis strategy on proteome coverage for trace samples. Int. J. Mass Spectrom 2018;427:4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li S, Plouffe BD, Belov AM, et al. An Integrated Platform for Isolation, Processing, and Mass Spectrometry-based Proteomic Profiling of Rare Cells in Whole Blood. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2015;14:1672–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun L, Zhu G, Zhao Y, et al. Ultrasensitive and fast bottom-up analysis of femtogram amounts of complex proteome digests. Angew. Chemie - Int Ed. 2013;52:13661–13664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zubarev RA, Makarov A. Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem 2013;85:5288–5296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.*.Makarov A, Denisov E. Dynamics of Ions of Intact Proteins in the Orbitrap Mass Analyzer. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2009;20:1486–1495.Orbirtap MS was applied to detect single protein molecules.

- 18.Rose RJ, Damoc E, Denisov E, et al. High-sensitivity Orbitrap mass analysis of intact macromolecular assemblies. Nat. Methods 2012;9:1084–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly RT, Tolmachev AV, Page JS, et al. The ion funnel: Theory, implementations, and applications. Mass Spectrom. Rev 2010;29:294–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaffer SA, Prior DC, Anderson GA, et al. An Ion Funnel Interface for Improved Ion Focusing and Sensitivity Using Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 1998;70:4111–4119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Page JS, Tang K, Kelly RT, et al. Subambient pressure ionization with nanoelectrospray source and interface for improved sensitivity in mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem 2008;80:1800–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marginean I, Page JS, Tolmachev AV, et al. Achieving 50% ionization efficiency in subambient pressure ionization with nanoelectrospray. Anal. Chem 2010;82:9344–9349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasa-Tolić L, Masselon C, Barry RC, et al. Proteomic analyses using an accurate mass and time tag strategy. Biotechniques 2004;37:621–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tyanova S, Temu T, Cox J. The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nat. Protoc 2016;11:2301–2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen X, Shen S, Li J, et al. IonStar enables high-precision, low-missing-data proteomics quantification in large biological cohorts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2018;115:E4767–E4776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ethier M, Hou W, Duewel HS, et al. The proteomic reactor: A microfluidic device for processing minute amounts of protein prior to mass spectrometry analysis. J. Proteome Res 2006;5:2754–2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian R, Wang S, Elisma F, et al. Rare Cell Proteomic Reactor Applied to Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC)-based Quantitative Proteomics Study of Human Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2011;10:M110–000679.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen W, Wang S, Adhikari S, et al. Simple and Integrated Spintip-Based Technology Applied for Deep Proteome Profiling. Anal. Chem 2016;88:4864–4871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Safdar M, Sproß J, Jänis J. Microscale immobilized enzyme reactors in proteomics: Latest developments. J. Chromatogr. A 2014. p. 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang EL, Piehowski PD, Orton DJ, et al. Snapp: Simplified nanoproteomics platform for reproducible global proteomic analysis of nanogram protein quantities. Endocrinology 2016;157:1307–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clair G, Piehowski PD, Nicola T, et al. Spatially-Resolved Proteomics: Rapid Quantitative Analysis of Laser Capture Microdissected Alveolar Tissue Samples. Sci. Rep 2016;6:39223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waanders LF, Chwalek K, Monetti M, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of single pancreatic islets. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci U.S.A 2009;106:18902–18907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Q, Yan G, Gao M, et al. Ultrasensitive Proteome Profiling for 100 Living Cells by Direct Cell Injection, Online Digestion and Nano-LC-MS/MS Analysis. Anal. Chem 2015;87:6674–6680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu Y, Dou M, Piehowski PD, et al. Spatially Resolved Proteome Mapping of Laser Capture Microdissected Tissue with Automated Sample Transfer to Nanodroplets. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2018;17:1864–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Budnik B, Levy E, Slavov N. Mass-spectrometry of single mammalian cells quantifies proteome heterogeneity during cell differentiation. bioarXiv DOI: 10.1101/102681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Russell CL, Heslegrave A, Mitra V, et al. Combined tissue and fluid proteomics with Tandem Mass Tags to identify low-abundance protein biomarkers of disease in peripheral body fluid: An Alzheimer’s Disease case study. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2017;31:153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hughes CS, Foehr S, Garfield DA, et al. Ultrasensitive proteome analysis using paramagnetic bead technology. Mol. Syst. Biol 2014;10:757–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Virant-Klun I, Leicht S, Hughes C, et al. Identification of Maturation-Specific Proteins by Single-Cell Proteomics of Human Oocytes. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2016;15:2616–2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Palma S, Stange D, Van De Wetering M, et al. Highly sensitive proteome analysis of FACS-sorted adult colon stem cells. J. Proteome Res 2011;10:3814–3819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Espina V, Wulfkuhle JD, Calvert VS, et al. Laser-capture microdissection. Nat. Protoc 2006;1:586–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Graaf EL, Pellegrini D, McDonnell LA. Set of Novel Automated Quantitative Microproteomics Protocols for Small Sample Amounts and Its Application to Kidney Tissue Substructures. J. Proteome Res 2016;15:4722–4730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quanico J, Franck J, Cardon T, et al. NanoLC-MS coupling of liquid microjunction microextraction for on-tissue proteomic analysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Proteins Proteomics 2017;1865:891–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rizzo DG, Prentice BM, Moore JL, et al. Enhanced Spatially Resolved Proteomics Using On-Tissue Hydrogel-Mediated Protein Digestion. Anal. Chem 2017;89:2948–2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kolodziejczyk AA, Kim JK, Svensson V, et al. The Technology and Biology of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Mol. Cell 2015;58:610–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyamoto DT, Zheng Y, Wittner BS, et al. RNA-Seq of single prostate CTCs implicates noncanonical Wnt signaling in antiandrogen resistance. Science 2015;349 (6254):1351–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deng L, Ibrahim YM, Hamid AM, et al. Ultra-High Resolution Ion Mobility Separations Utilizing Traveling Waves in a 13 m Serpentine Path Length Structures for Lossless Ion Manipulations Module. Anal. Chem 2016;88:8957–8964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Catherman AD, Skinner OS, Kelleher NL. Top Down proteomics: Facts and perspectives. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2014; 445(4): 683–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yi L, Shi T, Gritsenko MA, et al. Targeted Quantification of Phosphorylation Dynamics in the Context of EGFR-MAPK Pathway. Anal. Chem 2018;90:5256–5263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]