Abstract

Cross-coupling of nitrogen with hydrocarbons under fragment coupling conditions stands to significantly impact chemical synthesis. Herein, we disclose a C(sp3)—N fragment coupling reaction between terminal olefins and N-triflyl protected aliphatic and aromatic amines via Pd(II)/SOX catalyzed intermolecular allylic C-H amination. A range of (56) allylic amines are furnished in good yields (avg. 75%) and excellent regio- and stereoselectivity (avg. >20:1 linear:branched, >20:1 E:Z). Mechanistic studies reveal that the SOX ligand framework is effective at promoting functionalization by supporting cationic π-allyl Pd.

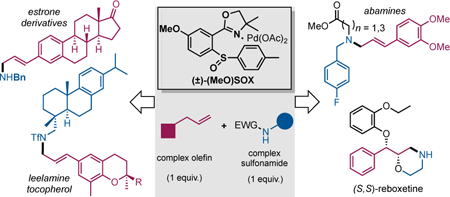

Graphical Abstract

Aliphatic amines are prominent in pharmaceuticals,1 with ca. half of all heteroatom derivatizations being C(sp3)—N bond formation.2 These reactions couple amines and prefunctionalized compounds (e.g. N-alkylation, reductive amination), necessitating unproductive synthetic steps.2 Advances in olefin hydroamination to furnish aliphatic amines underscore the advantages of coupling amines directly to hydrocarbons.3 Allylic C—H amination is an orthogonal approach furnishing amines where functionalities prone to reduction are maintained.

Methods for allylic C—H aminations typically require doubly activated, acidic nitrogen nucleophiles not amenable to fragment coupling.4, 5 For example Pd(II)-catalyzed intermolecular allylic C—H aminations require use of N-tosyl carbamate nucleophiles (Figure 1).4 The nearly ligandless conditions (e.g. fluxional sulfoxide ligands) renders catalyst deactivation and the ability to tune functionalization limited. Mixed sulfoxideoxazoline ligands (SOX),6,7 were recently reported for Pd(II)-catalyzed asymmetric allylic C—H oxidations.7 The uniform, high level of asymmetric induction (>90% ee) suggests that SOX does not dissociate from Pd during catalysis.7 Herein we report the discovery of a novel Pd(II)/(±)-MeO-SOX catalyzed allylic C—H amination that enables complex olefins to be coupled to complex N-triflyl amines8 to afford allylic amines in good yields and excellent regio- and stereoselectivity.

Figure 1.

From allylic C—H amination to cross-coupling

We initiated our investigation by examining the reactivity of bench-stable N-triflyl phenethylamine with allyl cyclohexane under previously reported allylic C—H amination conditions4b, d (Table 1). Using the less acidic aliphatic sulfonamide, we observed trace reactivity with the Pd(II)/bis-sulfoxide, even in the presence of additives reported to promote functionalization (entry 1).4b, d Using Pd(II)(OAc)2 with a simple racemic (±)-SOX ligand (L-1) we observed the reaction proceeds in 30% yield with outstanding regio- and stereoselectivity to form the sterically preferred linear product (entry 2). Evaluation of quinone oxidants indicated alkyl substitution was beneficial: benzoquinone (BQ) diminished the reactivity (entry 3), whereas 2,5-dimethylbenzoquinone (2,5-DMBQ) boosted it (entry 4). The modularity of the SOX ligand framework enables rapid evaluation of electronic and steric modifications.7 Exchanging the dimethyl groups on the oxazoline for diphenyls lowered the yield to 21% (entry 5). Whereas electronic modifications on the aryl backbone para to the oxazoline did not significantly positively impact the yield (entry 6, 7), electron donating methoxy para to the sulfoxide on the ligand backbone and the aryl sulfoxide resulted in substantial improvements in yield (entry 8, 9). No synergy resulted from combining these electron donating modifications (entry 10, 11). Lowering the (L-5)/Pd(OAc)2 catalyst loading to 5% maintained a useful yield (entry 12), whereas, omission of L-5 gave no detectable product (entry 13). Shorter reaction times at 45 °C (48h or 24h, entries 8, 14, Figure 3a) or 55°C (24 h, entry 14) afforded product in useful yields.

Table 1.

Reaction development

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Pd(II) | Ligand | Quinone | Time (h) | % Yield |

| 1a | Pd(OAc)2 | BQ | 72 | <5 | |

| 2 | Pd(OAc)2 | L-1 | 2,6 DMBQ | 72 | 30 |

| 3 | Pd(OAc)2 | L-1 | BQ | 72 | 24 |

| 4 | Pd(OAc)2 | L-1 | 2,5 DMBQ | 72 | 52 |

| 5 | Pd(OAc)2 | L-2 | 2,5 DMBQ | 72 | 21 |

| 6 | Pd(OAc)2 | L-3 | 2,5 DMBQ | 72 | 32 |

| 7 | Pd(OAc)2 | L-4 | 2,5 DMBQ | 72 | 55 |

| 8 | Pd(OAc)2 | L-5 | 2,5 DMBQ | 72 (48) | 75 (73) |

| 9 | Pd(OAc) | L-6 | 2,5 DMBQ | 72 | 63 |

| 10 | Pd(OAc) | L-7 | 2,5 DMBQ | 72 | 55 |

| 11 | Pd(OAc)2 | L-8 | 2,5 DMBQ | 72 | 74 |

| 12 | Pd(OAc)2 (5%) | L-5 (5%) | 2,5 DMBQ | 72 | 53 |

| 13b | Pd(OAc)2 | none | 2,5 DMBQ | 72 | ND |

| 14 | Pd(OAc)2 | L-5 | 2,5 DMBQ | 24 | 54 (65)c |

| |||||

Isolated yields average 2 runs.

Conditions: 10 mol% Pd(OAc)2/bis-sulfoxide, 2.0 equiv. BQ, 6% Cr(salen)Cl or DIPEA, TBME, 45 °C, 72 h.

96% recovered amine.

55°C.

Exploring reaction scope with respect to the amine, we found biologically relevant aniline and benzyl amines1 could be introduced with good yields and excellent selectivities (Table 2a, 2-4). Basic aliphatic amines such as methyl-and butylamine are also well tolerated (5, 6). Notably, amines with dense functionality all afforded product in good yields: ethylene diamine (7), aminoethanol (8) bromoethanamine (9) and trifluoroethanamine (10). Amino acid derived nucleophiles with α-stereocenters underwent intermolecular allylic C—H amination with no epimerization (11–13).

Table 2.

Substrate scope*

|

Isolated yields average 3 runs.

24 h.

No stereoerosion observed.

Reactivity was not observed with internal olefins.

PhSH, yield over 2 steps.

Evaluating the scope with respect to the olefin component, remote electrophilic functionality such esters, amides, and ketones and even a terminal epoxide were found to be well tolerated under these oxidative conditions (Table 2b, 14–17). Di- and tri-substituted internal olefins (18, 19) are preserved with this allylic C—H amination that is completely chemoselective for terminal olefins. A dibenz[b,f]azepine derived substrate (20) as well as sugar derivative (21) underwent C—H amination with good yields and selectivities. Electrophilic functionality susceptible to reduction during N-triflyl deprotection can be maintained by aminating with N-nosyl alkyl amines (22). Homoallylic stereogenic centers on the olefin do not epimerize (23–27) and may be coupled with chiral sulfonamides to rapidly generate chiral allylic amines as all possible diastereomers (24–27).

Late-stage C—H oxidation has emerged as a powerful strategy for streamlining synthesis9a, b and rapidly diversify complex molecules9c-g. In contrast to current methods that add functionality, Pd(II)/SOX allylic C—H amination enables late-stage fragment coupling (Figure 2).4b, d. δ-Tocopherol, a vitamin E antioxidant, was coupled to medicinally important N-triflyl benzylamine1 in good yield using only 5 mol% catalyst (28). Basic tertiary amine functionality, prevalent in alkaloids and pharmaceuticals, is well-tolerated upon in situ protonation with dichloroacetic acid.10 Under these conditions a dextromethorphan derivative furnished allylic amine (29) in excellent yields. Allylated derivatives of the steroid hormones ethinyl estradiol and estrone aminated, notably in the presence of an unprotected tertiary alcohol, internal alkyne, and ketone (30–32). N-nosyl benzylamine may be coupled, abeit in lower yields, and readily deprotected to afford aminated estrone derivative (32) with preserved C17 ketone. Alternatively, the C17 ketone of 31 can be diversified to a medicinally relevant homoallylic alcohol11a and vinyl pyridine11b, that after deprotection afford N-benzyl cinnamylamine analogues 31a and 31b.

Figure 2.

Late-stage C—H cross-coupling

Allylated δ-tocopherol was next coupled with a variety of complex amines (Figure 2b). Chiral α-methyl benzyl amine, N-triflyl protected amino acid, and gramine indole derivative were all coupled to allylated δ-tocopherol to furnish aminetocopherol hybrids in good yields with high regio- and stereoselectivities (33–35). Even leelamine, a complex diterpenic amine with chemotherapeutic activity,12 was effectively coupled to afford conjugate 36. It is significant to note the use of only 1 equivalent of olefin and amine, underscoring this C—H amination’s capacity to serve as a late-stage cross-coupling method for complex fragments.

The capacity of Pd(II)/SOX catalyzed C—H amination to streamline syntheses of important allylic amine cores and intermediates was investigated (Figure 3). The core of abamine (37), an inhibitor of the abscisic acid biosynthetic pathway,13a is rapidly accessed via allylic C-H amination of 1,2-dimethoxy-4-allylbenzene with N-triflyl 4-fluoro- benzylamine using only 2.5 mol% (±)-MeO-SOX ligand (L-5)/Pd(OAc)2 catalyst followed by deprotection.13b Conventional syntheses proceed from cinnamic acids via a reduction/oxidation/amination sequence.13a Sixteen novel, functionally diverse abamine derivatives, many more circuitous to access via a cinnamic acid route (e.g. 39, 40, 42, 47), are directly accessed via this method. Functionality prone to reduction are maintained during deprotection using the N-nosyl amine nucleophile (43, 44).

Figure 3.

Streamlining the synthesis of medicinally important small molecules via C—H to C—N cross-coupling.

The allylic amines generated via Pd(II)/SOX catalysis serve as intermediates for amino diols (Figure 3b). Moreover, amine protection confers compatibility with electrophilic functionalities, that may be further derivatized prior to deprotection. Previous syntheses of (S, S)-Reboxetine, a clinically used antidepressant, proceed via asymmetric epoxidation of cinnamyl alcohol followed by functional group manipulations to afford the terminal amine.14 Allylic C—H amination between commercial allylbenzene and N-triflyl 2-bromoethylamine nucleophile furnished E-allylic amine 56. Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation furnished the chiral amino diol that upon exposure to sodium hydride cyclized with the alkyl bromide to the key morpholine 57. Coppercatalyzed etherification followed by lithium aluminum hydride triflate removal furnished (S, S)-Reboxetine in 96% ee. The five step sequence (48% overall yield) compares favorably with the seven step industrial route (41% overall yield).14 Although not yet optimal for manufacturing, this route’s capacity for rapid core diversification by altering the allylated aromatic and/or amine are features useful in the drug discovery phase.

We hypothesized that the catalytic cycle for Pd(II)/SOX catalyzed allylic C—H amination proceeds via allylic C—H cleavage to afford a cationic Pd(SOX) π-allyl intermediate A, activated towards functionalization (Figure 4a, 4b). We hypothesized that SOX’s ability to support A is a key to why it promotes C—H amination with less activated amines and the previous bis-sulfoxide ligand is ineffective. Initial rate studies on parallel reactions gave a primary kinetic isotope effect (KIE) of 2.4 ± 0.1, consistent with a mechanism proceeding via C—H cleavage. The higher intramolecular competition KIE 4.0 ± 0.1 suggests that C—H cleavage is not the sole rate-determining step.15 To investigate if N-triflylamine inhibits Pd(II)/bis-sulfoxide catalysis, we ran a standard reaction4d with N-tosyl carbamate in the presence of 1 equiv. of a N-triflyl amine (Figure 4c). Despite the drop in yield, reactivity was not prevented and no amination product from the N-triflyl amine was seen. This suggests that failure to promote functionalization is the problematic step rather than catalyst deactivation via amine binding. To directly probe functionalization, we synthesize a π-allyl Pd acetate dimer16 in situ and observed complexation with (±)-MeO-SOX ligand by 1H NMR (Figure 4d). Subsequently subjection of complex A to mock catalytic conditions furnished aminated product 61 in yields and selectivities comparable those of the catalytic reaction. In contrast, using the bis-sulfoxide ligand in analogous experiments no complexation or functionalization was observed. This is consistent with previous studies showing that while bis-sulfoxide is critical for C—H cleavage it is unable to promote functionalization.16 Collectively, this data strongly supports that a unique feature of the SOX ligand platform is the ability to chelate and stabilize cationic π-allyl Pd intermediates electrophilically activated towards functionalization.

Figure 4.

Proposed mechanism and mechanistic studies

The (±)-MeO-SOX ligand/Pd(OAc)2 catalyzed intermolecular allylic C—H amination showcases the ability of C—H functionalizations to serve as cross-coupling methods that simultaneously introduce new functionality while joining two complex fragments. Mechanistic studies indicate that the SOX ligand is effective at promoting functionalizations with π-allyl Pd electrophiles by stabilizing a cationic intermediate. This is analogous to the role of phosphine ligands in Pd(0)-catalyzed allylic substitutions and suggests that the SOX framework may provide an oxidatively stable ligand platform for C—H oxidation that controls functionalization.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Financial support NIGMS MIRA (R35 GM122525). We thank W. Liu, Dr. S. Ammann for preliminary ligand studies; Dr. J. Clark, Dr. J. Griffin for checking experimental procedure; Dr. L. Zhu for NMR data analysis, and Johnson Matthey for Pd(OAc)2.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. The Supporting information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI 10.1021/jacs.7b13492.

Experimental details, characterization data, spectral data (PDF)

REFERENCES:

- (1).Vitaku E; Smith DT; Njardarson JT J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 10257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Roughley SD J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Copper: Miki Y; Hirano K; Satoh; Misura M Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2013, 52, 10830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhu S-L; Niljianskul N; Buchwald SL J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 15746 Other metals: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sevov CS; Zhou JS; Hartwig JF J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yang X; Dong VM J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 1774 organocatalytic: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Shapiro ND; Rauniyar V; Hamilton GL; Wu J; Toste FD Nature 2011, 470, 245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Margrey KA; Nicewicz DA Acc. Chem. Res 2016, 49, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Musacchio AJ; Lainhart BC; Zhang X; Naguib SG; Sherwood TC; Knowles RR Science 2017, 355, 727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Fraunhoffer KJ; White MC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 7274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Reed SA; White MC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu G; Yin G; Wu L Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2008, 47, 4733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Reed SA; Mazzotti AR; White MC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 11701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Liron F; Oble J; Lorion MM; Poli G Eur. J. Org. Chem 2014, 5863. [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Collet F; Dodd RH; Dauban P Chem. Commun 2009, 5061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Harvey ME; Musaev DG; Du Bois JJ Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 17207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Paradine SM; Griffin JR Zhao J, Petronico AL Miller SM; White MC Nat. Chem 2015, 7, 987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Kondo H; Yu F; Yamaguchi J; Liu G-H; Itami K Org. Lett 2014, 16, 4212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ammann SE; Liu W; White MC Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 9571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hendrickson JB; Bergeron R Tetrahedron Lett 1973, 14, 3839. [Google Scholar]

- (9) (a).Stang EM; White MC Nat. Chem 2009, 1, 547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen K & Baran PS Nature 2009, 459, 824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen MC; White MC Science 2007, 318, 783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gormisky PE; White MC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 14052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Huang X-Y; Bergsten TM; Groves JT J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 5300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Karimov RR, Sharma A & Hartwig JF ACS, Cent. Sci 2016, 2, 715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Czaplyski WL; Na CG; Alexanian EJ J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 13854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Howell JM; Feng K; Clark JR; Trzepkowski LJ; White MC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 14590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11) (a).Eignerová B; Sedlák D; Dračínský M; Bartůněk P; Kotora M J. Med. Chem 2010, 53, 6947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) 3-vinyl pyridine is in steroidal drug ZYTIGA (abiraterone acetate). [Google Scholar]

- (12).González MA Eur. J. Med. Chem 2014, 87, 834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13) (a).Han S; Kitahata N; Saito T; Kobayashi M; Shinozaki K; Yoshida S Asami T Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2004, 14, 3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Prediger P; Barbosa LF; Génisson Y; Correia CR D. J. Org. Chem 2011, 76, 7737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hayes ST; Assaf G; Checksfield G; Cheung C; Critcher D; Harris L; Howard R; Mathew S; Regius C; Scotney G Scott A Org. Process Res. Dev 2011, 15, 1305. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Simmons EM; Hartwig JF Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51, 3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Chen MS; Prabagaran N; Labenz NA; White MC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 6970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.