Abstract

Background and aims

Child maltreatment is a global health priority affecting up to half of all children worldwide, with profound and ongoing impacts on physical, social and emotional wellbeing. The perinatal period (pregnancy to two years postpartum) is critical for parents with a history of childhood maltreatment. Parents may experience ‘triggering’ of trauma responses during perinatal care or caring for their distressed infant. The long-lasting relational effects may impede the capacity of parents to nurture their children and lead to intergenerational cycles of trauma. Conversely, the perinatal period offers a unique life-course opportunity for parental healing and prevention of child maltreatment. This scoping review aims to map perinatal evidence regarding theories, intergenerational pathways, parents’ views, interventions and measurement tools involving parents with a history of maltreatment in their own childhoods.

Methods and results

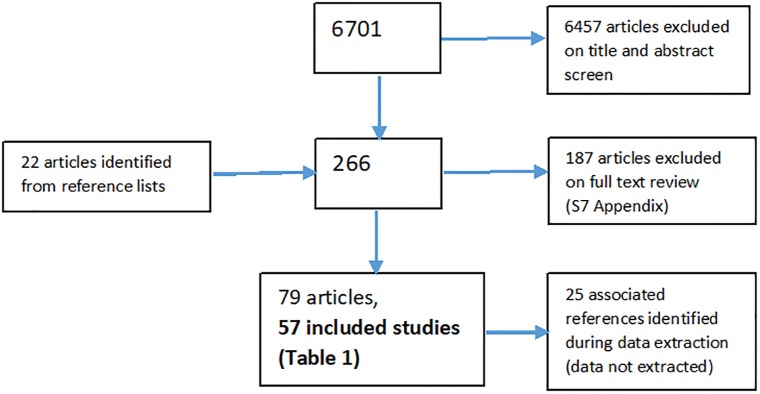

We searched Medline, Psychinfo, Cinahl and Embase to 30/11/2016. We screened 6701 articles and included 55 studies (74 articles) involving more than 20,000 parents. Most studies were conducted in the United States (42/55) and involved mothers only (43/55). Theoretical constructs include: attachment, social learning, relational-developmental systems, family-systems and anger theories; ‘hidden trauma’, resilience, post-traumatic growth; and ‘Child Sexual Assault Healing’ and socioecological models. Observational studies illustrate sociodemographic and mental health protective and risk factors that mediate/moderate intergenerational pathways to parental and child wellbeing. Qualitative studies provide rich descriptions of parental experiences and views about healing strategies and support. We found no specific perinatal interventions for parents with childhood maltreatment histories. However, several parenting interventions included elements which address parental history, and these reported positive effects on parent wellbeing. We found twenty-two assessment tools for identifying parental childhood maltreatment history or impact.

Conclusions

Perinatal evidence is available to inform development of strategies to support parents with a history of child maltreatment. However, there is a paucity of applied evidence and evidence involving fathers and Indigenous parents.

Introduction

Child maltreatment is a global health priority affecting 25 to 50% of children worldwide [1] and can have profound and ongoing impacts on physical and social and emotional wellbeing and development [2, 3]. Conflicting infant attachment and defence (fear or ‘flight, fright and freeze’) systems can be activated in response to child maltreatment which can lead to internal confusion and behavioural responses that are an attempt to manage distress and promote self-regulation, but may also result in increased confusion and harm [4]. These responses can be maintained into adulthood as part of a cluster of symptoms associated with recently proposed criteria for diagnosis of complex post-traumatic stress disorder (complex PTSD) [5]. Complex PTSD, caused by cumulative exposure to traumatic experiences that often involve interpersonal violation within a child’s care giving system (sometimes referred to as ‘developmental’ or ‘relational’ trauma), can occur in families, within the context of social institutions [6], and be exaberbated by cumulative traumatic experiences as an adult.

Long-term associations with childhood maltreatment include smoking, eating disorders, adolescent [7] and unplanned pregnancies [8], adverse birth outcomes [9], and a range of physical and psychological morbidities [10]. Critically, these long-lasting relational effects can impede the capacity of parents to nurture and care for children, leading to ‘intergenerational cycles’ of trauma [4]. Parental fear responses can be triggered by their child’s distress, and are often re-experienced as conflicting sensations and emotions, rather than as a thought-out narrative [11]. This in turn can give rise to hostile or helpless responses to the growing child’s needs [12]. In addition, the intimate nature of some perinatal experiences associated with pregnancy, birth and breastfeeding pose a high risk of triggering childhood trauma responses.

Conversely, the transition to parenthood during the perinatal period (pregnancy to two years postpartum) offers a unique life-course opportunity for improving health [13], for healing [3] and for relational growth [14]. Growing research into the ‘neurobiology of attachment’ demonstrates that healing can occur despite severe experiences of maltreatment, by restoring a sense of safety and well-being through nurturing, supportive relationships with others—a transition sometimes referred to as ‘earned security’. A positive strengths-based focus during the often-optimistic perinatal period has the potential to disrupt the ‘vicious cycle’ of intergenerational trauma into a ‘virtuous cycle’ that contains positively reinforcing elements that promote healing [14].

Despite the critical importance of the perinatal period for parents who have a history of maltreatment in their own childhoods; and frequent scheduled contacts with service providers during pregnancy, birth and early parenthood; there is limited specific guidance for care in the perinatal period for parents who have experienced maltreatment in their own childhoods [15]. In Australia, National Trauma Guidelines emphasize the need for trauma-informed care and trauma-specific support for the general population [6], and Perinatal Mental Health Guidelines recommend that perinatal care providers conduct a psychosocial assessment for mothers, including childhood maltreatment history [16]. However, there is limited guidance on trauma-specific care and support interventions in the perinatal period for parents with a history of childhood maltreatment, which is required for any population-based screening program [17].

Child maltreatment is not randomly distributed. The World Health Organization (WHO) use a socioecological framework [18] to explain why some people are at higher risk of experiencing interpersonal violence [19]. Parents with a history of childhood maltreatment are also more likely to have multiple socio-economic challenges, including unintended pregnancies [8], antenatal and postnatal depression [20], contact with the justice system and low employment [21]. Within Australia, there have been harrowing reports documenting high rates of child maltreatment and violence among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (Aboriginal) communities in Australia [22]. The reasons for this are complex and lie beyond the scope of this review but are influenced by a legacy of past governmental policies of forced removal of Aboriginal children from their Aboriginal families and communities, intergenerational effects of these previous separations from family and culture, ongoing oppressive policies, social exclusion, marginalisation and poverty [23, 24]. Thus, Australian National Trauma Guidelines emphasize the need for understandings of complex trauma to be contextualised within socioecological environments [6].

The primary aim of this scoping review is to map perinatal evidence involving parents with a history of childhood maltreatment. Our specific purpose is to identify relevant evidence to support the co-design of strategies for perinatal trauma-informed care (awareness), recognition, assessment and support for Aboriginal parents with a history of maltreatment in their own childhoods. We briefly illustrate how this scoping review is being incorporated into the co-design process in the discussion, with a project led by our team [25]. While this review is designed to address a direct practical purpose, we expect that it will have broader applicability to those working with parents who have experienced maltreatment in their own childhoods and help to prioritise future research in this critical area. A secondary aim is to use this scoping review to refine the search strategy and develop detailed protocols for further in-depth systematic reviews (see S1 Appendix for overview of planned reviews).

The specific questions for this ‘phase 1’ scoping review are:

What theories are used during the perinatal period to understand and frame the impact of a parental history of childhood maltreatment?

What risk and protective factors are identified in epidemiological evidence of life-course and intergenerational pathways (mediators/moderators) between a parental history of childhood maltreatment and behavioural/health outcomes for parents and their infants?

What are the perinatal experiences of parents with a history of childhood maltreatment? And what perinatal strategies do these parents report using to heal and prevent intergenerational transmission of trauma to their child?

What perinatal interventions are described to support parents with a history of childhood maltreatment to improve parental and child wellbeing?

What tools have been reported in the perinatal period to identify parents with a history of childhood maltreatment and/or assess symptoms of complex trauma?

Methods

PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews informed the reporting of this scoping review (see S2 Appendix for checklist) and the protocol on which it is based (S3 Appendix). We have also referred to extension statements for scoping reviews [26] and equity-focussed reviews [27].

Criteria for inclusion

Participants: Prospective (pre-pregnancy), pregnant and new parents (mothers and/or fathers) or families caring for children up to two years after birth. Where mean ages only were reported (and it was unclear if children were two years of age or younger), studies reporting a mean age of less than five years only (i.e. preschool age) were included. Studies which reported a proportion of participants as parents of children aged two years or less were also included, to err towards inclusivity. Despite the primary aim of the research being to inform co-design of strategies to support Aboriginal parents, we have not restricted the inclusion criteria to Aboriginal or Indigenous parents for several reasons. Firstly, we know there will be very limited published Indigenous-specific evidence available. Second, we will incorporate evidence from other population groups in a comprehensive co-design process which draws on the knowledge of Aboriginal parents and key-stakeholders, and enables Aboriginal Australian parents to consider the relevance of this evidence for them.

Interventions/exposures: Any parental report of childhood maltreatment. There is no broadly accepted consensus on a definition for complex PTSD, and this lack of consensus will be reflected in previously published included studies in this review. Therefore, for the purposes of this review, we are using the WHO definition of a key antecedent, child maltreatment:

“abuse and neglect that occurs to children under 18 years of age. It includes all types of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, negligence and commercial or other exploitation, which results in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power. Exposure to intimate partner violence is also sometimes included as a form of child maltreatment.”

[1]

We also include ‘proxy measures’ such as child protection substantiations or removal from their family of origin.

Study type/comparisons: Any study design, including randomised controlled studies (RCTs), cluster RCTs, cohort studies (including measurement/assessment studies), economic evaluations or qualitative studies (see S1 Appendix for an overview of the study types considered relevant to each question). We excluded reviews, guidelines, discussion and opinion papers, government reports and non-peer reviewed reports of primary studies. Review articles were screened for additional primary studies.

Outcomes: Theories; risk or protective factors which mediate or moderate parental or child outcomes; experiences, perspectives and strategies parents use for healing or preventing intergenerational transmission of trauma; acceptability, effectiveness and cost of current perinatal interventions; and perinatal tools used for assessing symptoms of complex trauma or exposure to childhood maltreatment. Studies which only reported associations between parental childhood maltreatment history and outcomes, without any investigation of mediating/moderating factors, were not included in this review as these associations have been well-established in other reviews [28].

Search methods

We searched the following databases: Psychinfo, Medline, Cinahl and Embase up to 30/11/2016. The search terms included both thesaurus (MeSH) and keyword synonyms for ‘child abuse’ AND ‘intergenerational’ AND ‘prevention’ AND ‘parent’, using a search strategy developed and piloted in Psychinfo (see S4 Appendix) and subsequently modified for use in the remaining databases. We checked reference lists from relevant reviews identified from the search for additional potentially relevant primary studies.

References were downloaded into bibliographic reference management software (Endnote) and de-duplicated. One reviewer (CC) independently screened titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant studies using an over-inclusive approach. The full texts of all potentially relevant studies were independently assessed by two reviewers (CC/GG) for inclusion, based on the pre-specified criteria for inclusion. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

A data extraction tool was developed and piloted in Microsoft Excel by two reviewers (CC/SB). Two reviewers (CC & GG/SG/YV/SC/SB) independently extracted data on the items that follow.

Population: study setting; selection criteria; recruitment process and sample size; parenting stage (pre-pregnancy, pregnancy to six weeks postpartum, six weeks to one year postpartum, one to two years postpartum); type of childhood trauma reported; parent characteristics that relate to progress-plus ‘equity’ criteria relevant to this review population (‘at risk’ status, age, place of residence, race/ethnicity, gender, language, religion, socio-economic status, social capital (e.g. marital status), and other (e.g. mental illness)) [29].

Intervention/study detail coding was based on the TiDIER framework [30]: aims; brief description; mode of delivery; who conducted study/intervention; duration and frequency of contacts; theoretical basis; analysis framework; individual tailoring; modifications/fidelity; collaboration/engagement.

Outcomes: how assessed (e.g. mail, face to face); unit of analysis; results summary; conclusion summary; detailed results under each of the main outcome categories (theories; mediating/moderating factors; parent experiences/perceptions; interventions; assessment tools and ‘other’).

Assessment of risk of bias within studies

For each included study, the risk of bias was assessed independently by two reviewers using domains from one of the following tools as appropriate for the study design (S5 Appendix).

RCTs and cluster RCTs: Cochrane risk of bias tool [31].

Controlled studies: Cochrane risk of bias tool with additional EPOC terms [32].

Cohort/observational studies: ROBINs [33].

Qualitative studies: CASP tool [34].

Assessment/screening tool accuracy studies: QUADAS checklist [35].

Overall confidence in study findings was assessed using an adaption of the GRADE approach (S6 Appendix). This provides a transparent and systematic method for incorporating information about study limitations (risk of bias), the validity of outcome measures (indirectness/relevance), and the adequacy of the sample (imprecision) in a summary of findings for each study. The overall assessment was conducted by one reviewer (CC), with the first ten assessments checked and discussed with a second reviewer (SB) before completing the remaining assessments. All studies started with an assessment of ‘high’ confidence, and were downgraded one level for serious concerns or two levels for very serious concerns about: study/methodological limitations; indirectness/relevance; and imprecision/adequacy to attain a final assessment of high, moderate, low or very low confidence. Overall confidence across study findings (e.g. consistency and publication bias) was not assessed in this scoping review.

Data synthesis

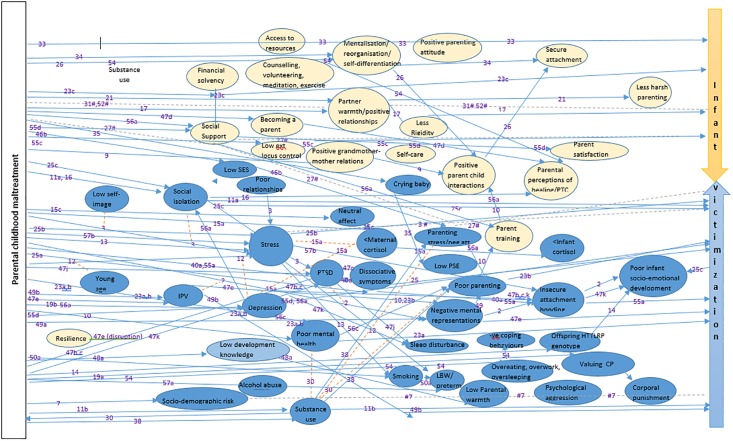

Outcome data were synthesized narratively under each of the main outcome categories (theories, risk and protective factors, parents’ views, interventions, assessment tools). Outcomes are summarised only briefly in this scoping review to map and illustrate the breadth of evidence, rather than offer a comprehensive assessment of strengths and limitations of the evidence. Evidence map templates were generated using primary and secondary outcomes specified in the scoping review protocol. Each study providing relevant information was illustrated numerically in the map/table, using a number which corresponds to an allocated study ID number in the Characteristics of Included Studies (COIS) Table (Table 1). The COIS table (Table 1) provides summary study-level information on the country, setting, participant number, parenting stage, parental childhood maltreatment history, study type, study aim, main results and overall confidence in study findings. In subsequent systematic reviews, we will use synthesis methods appropriate for specific study designs and explore the respective evidence and strengths and limitations of the evidence in more depth (S1 Appendix).

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

| Study number/ Study First Author surname/year (Associated refs)* = data extracted for AR [ref] | Country Setting [Study years if reported] | Number of participants (brief description) | Parenting stage | Childhood Trauma History (including proportion with history) | Study type | Study aim (specific) | Briefly describe the main results of the study | Confidence (primary study) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Adams 1996 [36] | USA (San Diego, California) |

206 parents | Pregnancy | 13/89 mothers reported emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, or ‘other‘. (Fathers self-report considered too low to be reliable.) | Cross-sectional | Screening and uptake of support (1) to determine the rate at which expectant first-time mothers will identify themselves as mistreated during childhood and, (2) for those who will, the rate at which they will accept offers of support services. | 43% expectant mothers responded to the survey. Of these almost 15% reported being abused. Nine of those 13 (69%), as well as 20 of the 76 (26%) who denied abuse, expressed interest in services ‘especially designed for expectant parents who were mistreated as children’. | Very low |

| 2. Ahlfs-Dunn 2015 [37] | USA (Washentaw and Wayne County) |

120 ’low income or high risk’ mother-infant dyads (46% African American, mostly unmarried but college educated) | Pregnancy to two years postpartum | Emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and emotional and physical neglect, childhood intimate partner violence (IPV) exposure, adult IPV. | Prospective cohort | Investigate intergenerational pathways: disrupted maternal representations of the child as a mediator of the association between mothers’ histories of interpersonal trauma and their infants’ socio-emotional development at 1 year of age. | There was an indirect effect of maternal childhood interpersonal trauma history on infant attachment security through disrupted prenatal maternal representations of the child. | High |

| 3. Altemeier 1986 [38] | USA (Inner city hospital, 1975–1976) |

927 mother-infant dyads (caucasian only, mostly low income, married with less than high school education) | Pregnancy | Physical abuse | Prospective cohort | Investigate intergenerational pathways: rates of abuse and characteristics associated with continuity. | Compared to mothers with no abuse history, abused mothers were: more likely to have felt unwanted and unloved as children, to have lower self-images and more isolation, greater stress (many reflecting disturbances in interpersonal relationships). However children were reported to protective services for abuse at the same frequency as control children. | Low |

| 4. Aparicio 2016 [39] | USA (Foster-child transition programme) |

6 teen mothers transitioning out of foster care (5 African-American and homeless) | unclear | Physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, witness to domestic violence | Qualitative (Interviews) | Parent strategies to break cycle: ’How do teen mothers in foster care experience motherhood in terms of working to break the cycle of child abuse and neglect?) | Two themes emerged: (i) treating children well/parenting differently and avoiding the system; and (ii) reducing isolation and enhancing support. | Low |

| 5. Armstrong 1999 [40] | Australia (Brisbane hospital, 1996) |

181 ’at risk’ parents (only mother’s outcomes assessed) (6% Indigenous, almost 20% did not complete high school, 40% sole parents). | Birth to 6 weeks postpartum | Childhood abuse’ otherwise unspecified (part of range of inclusion criteria) | Intervention (RCT) | Home visiting intervention for ’at risk’ parents | At 6wks pp, women in the intervention group had significant reductions in postnatal depression (primiparous women only), and improvements in their parental role and ability to maintain their own identity. Maternal-child interactions were likely to be more positive, with higher scores related to aspects of the home environment, particularly secure maternal infant-attachment. | Very low |

| 6. Arons 2005 [41] | USA (Massachusetts, Jewish family service) |

1 mother-infant dyad receiving therapy | 12 months postpartum ongoing | Physical (attempted homicide) and emotional abuse | Case study | Psychotherapy aims: the ability to recognize, to name, and to metabolize feelings; the ability to evoke a soothing maternal affect to aid in containment and integration of self-states; and the ability to be aware of and to relate to the partner’s mind. | Detailed vignette concluding: "Mary’s need to defend against the feelings John aroused coupled with her cognitive dysregulation (dissociation and transient thought disorder) had rendered her unable to consistently attend to their relationship. In mother-baby sessions we worked to enhance responsive relating by containing the fear and anger aroused by John’s need for comfort. In individual sessions we explored how Mary’s attachment needs within the transference paralleled those of her son.…Less constricted by her own defensive exclusion of painful affects, Mary developed freer access to her own inner world and to the emotional world of her son. As she began to release John from her malevolent projections and her need to control the fear he aroused, he emerged as a positive force of nature, a baby to be loved and understood." | Moderate |

| 7. Barrett 2009 [42] | USA (Illinois) |

494 mothers receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) benefits participating in waves 1 & 2 of Illinois Families study (83% African American and 11% Hispanic, 68% completed high school, 17% married/partner, 30% prior CPS involvement) | Children 3 years of age or younger | Child sexual abuse (CSA) and 5 other forms of childhood adversity (childhood physical abuse, perceiving that one had been neglected in childhood, observing domestic violence, childhood poverty, and living apart from one or both parents for all or part of childhood). | Cross-sectional study within longitudinal cohort. | Investigate intergenerational pathways: explore the association between CSA and adulthood parental stress, parental warmth, use of nonviolent discipline strategies, psychological aggression, and use of physical punishment. Additionally, whether other forms of childhood adversity altered this relationship. | CSA survivors reported significantly lower rates of parental warmth, higher rates of psychological aggression, and more frequent use of corporal punishment than mothers who had not experienced childhood sexual abuse. These effects, however, were non-significant when sociodemographic factors and other forms of childhood adversity were considered, suggesting that CSA may not be as salient a predictor of certain parenting practices than other forms of childhood adversity. | High |

| 8a. Bartlett 2015 [43] (8b. Bartlett 2012) [44] |

USA (Massachusetts, 2008–2010) |

447 mothers participating in Home Visiting Program evaluation (ethnically diverse, 56% receiving welfare). | Pregnancy (64%) to postpartum (36%) (child’s age unclear). This study uses RCT data collected at enrolment) and one year later. | Physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect | Prospective cohort (RCT participation as a control variable) | Investigate intergenerational pathways: examine whether positive care in childhood, social support while parenting, and older maternal age at birth moderate the association between young mothers’ childhood history of abuse and neglect and neglect of their own infants, and maternal lack of empathy as a correlate. | Approximately 77% of maltreated mothers broke the cycle with their infants (<30 months). Maternal age moderated the relation between a maternal history of neglect and infant neglect, and social support moderated the relation between childhood neglect and maternal empathy. Neglected mothers had considerably higher levels of parenting empathy when they had frequent access to social support than when they had less frequent support, whereas the protective effect of social support was not nearly as strong for non-maltreated mothers. | Moderate |

| 9. Baumgardner 2007 [45] | USA (Baltimore Maryland, 1997 ongoing) |

141 women (African American, under 18 years of age, primiparous, low income (eligible for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children—WIC), and residing within three-generation households. | Shortly after birth and this study reports followup at 24 months postpartum. | Physical and sexual abuse (38% reported abuse) | Cross-sectional study within longitudinal cohort. | Investigate intergenerational pathways: view of three generations examining a history of child abuse within the larger context of relationship quality to consider: (1) How does a history of abuse relate to the early parent-child relationship? (2) whether a history of abuse correlates with problems in the relationships between generations (3) does a more positive relationship with one’s own mother act as a buffer? (4) whether there are components of the intergenerational relationship, beyond attachment, that are affected by a history of childhood abuse, and (5) whether different types of abuse contribute to problems in the early mother-baby relationship. | Grandmother-adolescent mother relationship did show some moderating effect, in the presence of abuse, on parent-child interaction. Even in the presence of a history of childhood abuse, when grandmother-adolescent mother relationship quality is good and characterized by mutuality, autonomy, and comfort with negotiating disagreement, maternal behaviours promoting attachment processes and infant social competence are high. | Moderate |

| 10a. Baydar 2003 [46] (10b. Webster Stratton 1998b [47]; 10c. Webster-Stratton 2001 [48]) |

USA (Puget Sound area Head Start centers, 1993 to 1997) |

426 parents participating in Incredible Years Parenting Training Program (60% caucasian). | Pregnancy with followup after 6–12 week intervention | Measures of “harsh/ negative, supportive/positive, and inconsistent/in- effective parenting" | RCT/SEM | Parenting intervention: Evaluation of ‘Incredible Years’ program compared to Head Start’ curriculum to improve understanding of the way some psychological risk factors influence mothers’ parenting, mothers’ participation in parent training programs, and their ability to benefit from the parenting program. | Parent engagement training was associated with improved parenting in a dose-response fashion. Mothers with mental health risk factors (i.e., depression, anger, history of abuse as a child, and substance abuse) exhibited poorer parenting than mothers without these risk factors. However, mothers with risk factors were engaged in and benefited from the parenting training program at levels that were comparable to mothers without these risk factors. | Moderate |

| 11a. Berlin 2011 [49] (11b. Appleyard 2011*) [50] |

USA (Prenatal care clinics in a small southeastern city and its surrounding county) | 499 women (diverse ethnicity, most have partner, high proportion less than high school) | Pregnancy to two years postpartum | Physical abuse, sexual abuse and neglect (Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale) | Prospective cohort | Investigate intergenerational pathways: to examine associations between mothers’ childhood physical abuse and neglect and their child’s victimization during the first two years of life (Berlin 2011) and maternal substance use as a mediator (Appleyard 2011). | Mothers’ childhood physical abuse—but not neglect—directly predicted offspring victimization. This association was mediated by mothers’ social isolation, aggressive response biases (Berlin 2011). Maternal substance use was significantly associated with history of physical and sexual abuse, and mediated the mediated the pathway to offspring victimization (Appleyard 2011). | High |

| 12. Blackmore 2016 [9] | USA (Hospital obstetric clinic, 2007–2012) | 358 women (ethnically diverse, Mostly high school educated, 70% receiving Medicaid, 55% sole parents). | 18 and 32 weeks of pregnancy | Physical and sexual abuse, neglect. | Prospective cohort (longitudinal) | Investigate intergenerational pathways: trauma and trauma severity and adverse obstetric outcomes (lower birthweight, earlier gestational age, or delivery complications.) | Childhood trauma exposure increased vulnerability for low birthweight delivery associated with prenatal mood disturbance. | High |

| 13a. Blalock 2011 [51] (13b. Blalock 2013*)[52] |

USA (Texas, Houston metropolitan area, 2005–2008) |

201 women smoking in early pregnancy (Over 60% African-American or Hispanic, 34% less than high school, 65% receiving Medicaid, 48% sole parents). | Pregnancy | Emotional, sexual, and physical abuse and emotional and physical neglect categorised using cut scores to delineate none to minimal, low to moderate, moderate to severe, and severe to extreme levels of maltreatment. 59% sample experienced maltreatment. | RCT | Smoking cessation intervention: examines link between childhood trauma and smoking, and mediating role of depression (Blalock 2011); and whether childhood trauma moderated the treatment effect from a smoking cessation trial (Blalock 2013). | Moderate to extreme levels of childhood trauma were significantly related to smoking dependence and were partially mediated by depressive symptoms (Blalock 2011). There was a dose response association of treatment on depression outcome through 6 months postpartum; those with increasing amounts of childhood trauma benefitted more from CBASP, compared to those in the HW condition. Childhood trauma did not moderate the treatment effect on smoking abstinence, although increasing amounts of trauma were associated with reduced likelihood of abstinence at 6 months post treatment (Blalock 2013). | Moderate |

| 14. Bouvette-Turcot 2015 [53] | Canada (Montreal (Quebec) and Hamilton (Ontario) antenatal clinics) |

154 mother-term infant dyads (89% caucasian). | Pregnancy to 36 months postpartum | Emotional, physical and sexual abuse, emotional and physical neglect. | Prospective cohort | Investigate intergenerational pathways: relation between maternal adversity and NE/BR in the child, and if the effect of maternal childhood adversity is moderated by child 5-HTTLPR genotype. | There was a significant interaction effect of maternal childhood adversity and offspring 5-HTTLPR genotype on child negative emotionality/behavioural dysregulation. | Moderate |

| 15a. Brand 2010 [54] (15b. Cammack 2016* [55], 15c. Juul 2016* [56]) |

USA (Atlanta, Georgia Emory Women’s Mental Health Program, 2002–2011) |

126–255 women participating in mental health program, predominantly caucasian (94%), married (95%) and college-educated (82%). | Pregnancy to 6 months postpartum | Emotional, physical, sexual abuse and emotional and physical neglect. 30% sample experienced trauma. | Cross-sectional study within longitudinal cohort/Test retest survey. | Investigate intergenerational pathways) (1) (investigate the association between maternal history of child abuse and maternal cortisol levels in a clinical sample of postpartum women, and to explore whether depressive symptoms and stressful life events, as well as comorbid PTSD moderated this relationship, and transgenerational effects on the infant (Brand 2010). (2) Examine the stability of responses to the CTQ at two pregnancy timepoint (Cammack 2016) and (3) relationship between maternal history to differences in maternal affect and HPA axis functioning (Juul 2016). | Maternal childhood abuse was associated with steeper declines in cortisol in the mothers, and lower baseline cortisol in their infants. Comorbid maternal PTSD, current maternal depressive symptoms, and recent life stressors significantly moderated maternal cortisol change. Maternal abuse history was associated with increases in cortisol levels in those mothers who experienced these additional stressors. Similarly, a history of early maternal abuse and comorbid PTSD was associated with greater increases in infant cortisol levels (Brand 2010). CTQ response reliability was generally at least moderate, indicating consistent reporting across two time-points (Cammack 2010). Childhood maltreatment history predicted increased neutral affect and decreased mean cortisol in the mothers and that cortisol mediated the association between trauma history and maternal affect. Maternal depression was not associated with affective measures or cortisol (Juul 2016). | Low |

| 16. Bysom 2000 [57] | USA | 29 mothers who had experienced childhood abuse or witnessed IPV (mean age 40, predominantly college-educated and married). | Unclear | Physical abuse or witnessing IPV before age 13 (whole sample). | Cross-sectional study (mixed quantitative/qualitative) | Investigate intergenerational pathways: to identify types of social support utilized by resilient individuals from abusive backgrounds; and to explore the relationship between perceived social support and the ability to interrupt the cycle of violence. | No one type of social support was identified as being more prevalent than another. There was a positive relationship between perception of one’s own abuse after the age of 13 and type of support labelled as belonging social support. Similarly, there was a positive correlation between experienced abuse after the age of 13 and belonging and self-esteem support. There was a negative correlation between perception and experience of one’s own abuse prior to age 13 and the presence of a caring adult in childhood and a negative correlation between the perception and experience of one’s own abuse after age 13 and the presence of a caring adult and friend in childhood. Two thirds of the participants were affirmative in their belief that social support was helpful in breaking the cycle of violence. Narrative themes of social support, internal aspects of self and spirituality emerged as factors which played a role in breaking the cycle of violence. Awareness of alternatives and non-judgmental support were identified as aspects of social support which were deemed helpful. | Very low |

| 17. Caliso 1992 [58] | USA (Division of Youth and Family Services and the Correctional Institution for Women) |

90 mothers (30 perpetuating abuse, 30 discontinuing abuse and 30 with no abuse history (matched on socio-demographic characteristics: mean age 30, ethnically diverse, mean education 12 years, 30% married). | Unclear | Physical abuse (66% sample) | Cross-sectional study | Investigate intergenerational pathways: To determine the effect of a childhood history of abuse on adult child abuse potential. | Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) verbal and violence scales were higher for the abusive and non-abusive mothers with a childhood history of abuse. Child Abuse Potential (CAP) scores distinguished between all three study groups. However, only the rigidity and unhappiness factors discriminated between abusive and non-abusive mothers with a childhood history of abuse. Non-abusive mothers with a childhood history of abuse were less rigid in their child expectations and were happier in their interpersonal relationships than abusive mothers with a childhood history of abuse. | Low |

| 18. Chemtob 2011 [59] | USA (child welfare agencies in New York) |

127 mothers receiving preventive CW services with PTSD score >15. (63% Latina & 19% African American, 41% sole parents). | Preschool children | Any maternal trauma—including adult sexual assault, war, illness, imprisonment. | Cross-sectional study | Investigate intergenerational pathways: (1) trauma exposure rates among mothers and children receiving preventive services screened by the preventive services partners; (2) maternal PTSD and depression symptoms among the mothers in preventive services screened; and (3) ethnic differences in trauma exposure and trauma-related symptoms | There were high levels of trauma exposure among screened mothers (92%) and their young children (92%). 54.3% mothers met probable criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression (61.7%). Nearly half (48.8%) met criteria for co-morbid PTSD and depression. Most were not receiving mental health services. Latina women had significantly more severe PTSD symptoms than African American women. Case planners reported that the screening process was useful and feasible. | High |

| 19a. Chung 2009 [60] (19b. Chung 2008* [61], 19c. Chung 2006 [62], 19d. Chung 2004 [63], 19e.Culhane 2001 [64]) |

USA (community health centres in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2000–2002) |

1265–1476 women completing pre and postnatal interviews (predominantly African-American/Latina and low income, 40% did not complete high school, 78% sole parents). | Pregnancy to 11 months postpartum | Physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal hostility, domestic violence, witnessing or knowing a victim of a shooting (ACE). (76% reported at least 1 ACE and 51% reported at least 2.) | Prospective cohort | Investigate intergenerational pathways: (1) to assess associations among maternal childhood experiences and subsequent parenting attitudes and Infant spanking (IS), and to determine if parenting attitudes mediate (Chung 2009) (2) association between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), positive influences in childhood (PICs), and depressive symptoms among low-income pregnant women (Chung 2008). | (1) Mothers exposed to childhood physical abuse and verbal hostility were more likely to report IS use than those not exposed. In the adjusted analyses, maternal exposure to physical abuse, other ACEs, and valuing CP were independently associated with IS use. Attitudes that value CP did not mediate these associations (Chung 2009). (2) For each ACE, affected women were more likely to have depressive symptoms than their counterparts. There was a dose-response effect in that a higher number of ACEs was associated with a higher likelihood of having depressive symptoms. PICs, on the other hand, were associated with a lower likelihood of having risk. Efforts to prevent ACEs and to promote PICs might help reduce the risk of depressive symptoms and their associated problems in adulthood (Chung 2008). | Moderate |

| 20. Coles 2009 [65] | Australia (Melbourne Metropolitan area, 2005) | 11 mothers who had breastfed their baby. | Less than 2 years postpartum | Sexual abuse (whole sample). | Qualitative (Interviews) | To explore the experience of successful breastfeeding with mothers with a history of CSA. | Four key themes are identified: enhancement of the mother—baby relationship, validation of the maternal body, splitting of the breasts’ dual role as maternal and sexual objects, and exposure and control when breastfeeding in public. | Moderate |

| 21. Conger 2013 [66] | USA (rural counties in north central Iowa, 1994 Generation (G1) and 2005 (G2)). |

290 parents (G2) (120 males, 170 females) who had a G3 child eligible for participation by 2005. | Min 18 months, mean 2.31 years postpartum | Direct observation of G1 mother hostility (angry or rejecting behaviour), angry coercion (demanding, stubborn, coercive), physical attacks (hitting, pushing, pinching, etc.), and antisocial behaviour (self-centred, immature, insensitive) behaviour toward the G2 parent during adolescence. | Prospective cohort | Investigate intergenerational pathways: dimensions of adult romantic relationships that hold promise for reducing continuity in harsh parenting. | Romantic partner warmth and positive communication with G2 were associated with less G2 harsh parenting toward G3 (a direct effect) and when these partner behaviours were high, there was no evidence of intergenerational continuity from G1 to G2 harsh parenting. When the partner was low on warmth and communication, intergenerational continuity in harsh parenting significantly increased. G1 harsh parenting slightly decreased the likelihood that G2 would select a positive spouse. | High |

| 22. Dijlska 1995 [67] | Netherlands (1994) | 2 mothers | One with an 18month old and the other with a 6yo and 9yo child. | Physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect | Qualitative/Case study | Parent strategies to break cycle: how intergenerational patterns of violence are transformed and broken. | Invisibility of former abuse in adult life and limited ability to speak freely about the meaning of this. Discusses process orientated trauma therapy and transformations due to time and developmental stages/triggers—such as having a child and changing work challenges. Suggests triggers can be viewed as ticking time bombs but also as opportunities for working through certain aspects of trauma. | Low |

| 23a. Dixon 2005 [68] (23b. Dixon 2005b*[69], 23c. Dixon 2009*[70]) |

UK (Southend on Sea, Essex, England, 1995–1998) |

4351 parents (majority caucasian) | During first 13 months postpartum | Physical and/or sexual abuse in their own childhood (<16 years), (135/4351 parents). | Prospective cohort | Investigate intergenerational pathways (1) to explore risk factors, parental attitudes and behaviour implicated in the intergenerational cycle of maltreatment (Dixon 2005); (2): explore the mediating properties of secure relationships and their interplay with risk factors in the intergenerational cycle of maltreatment (Dixon 2005b) and; (3) investigate factors associated with both the continuation and discontinuation of the intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment (Dixon 2009). | Within 13 months after birth, 6.7% AP families were referred for maltreating their own child in comparison to.4% NAP families. AP families had significantly higher numbers of risk factors. Mediational analysis found that intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment was explained to a larger extent (62% of the total effect) by the presence of poor parenting styles together with the three significant risk factors (parenting under 21 years, history of mental illness or depression, residing with a violent adult). The three risk factors alone were less explanatory (53% of the total effect) (Dixon 2005, 2005b). Protective factors of financial solvency and social support distinguished Cycle Breakers from Maintainers and Initiators. Therefore, it is the presence of protective factors that distinguish Cycle Breakers from families who were referred to Child Protection professionals in the first year after birth (Dixon 2009). | Moderate |

| 24. Draucker 2011 [71] | USA (metropolitan Akron, OH) |

95 men and women (50% African-American, 68% employed). | unclear | Sexual abuse (mostly in context of caregiving relationship). Whole sample. | Qualitative (Interviews) | To describe, explain, and predict women’s and men’s responses to sexual violence throughout their lives and construct a healing model. | The CSA Healing Model is a model that represents the multifaceted and dynamic process of healing from CSA over the lifespan. The model does not focus on discrete variables associated with positive or negative coping but rather captures some complex healing processes that culminate in the experience of laying claim to one’s life. The model includes four stages of healing, five domains of functioning, and six enabling factors that facilitate movement from one stage to the next. The model indicates that clinicians should focus on how clients might move from grappling with the meaning of the CSA, to figuring out its meaning, to tackling its effects, and ultimately, to laying claim to their lives, and they should be ready to discuss healing in any one of several domains. Because parenting was of great concern to most participants, it should routinely be addressed as a therapeutic issue. The model suggests that parenting should not be considered a dichotomous factor; that is, one either abuses or one nurtures one’s children. Rather, the processes of wishing to stop the cycle of abuse and attempting to stop the cycle of abuse were critical steps that need to be acknowledged and fostered. | Moderate |

| 25a. Egeland 1996 [72] (25b. Egeland 1988 [73], 25c. Bosquet 2016 [74]) |

USA (Maternal and Infant Care Clinics, Minneapolis Health Department, from 1975) |

24, 30 (Egeland) and 187 (Bosquet 2016) mother-infant dyads (80% caucasian, 40% had not completed high school, 62% sole parents). | Pregnancy (recruitment) to 48–54 months postpartum | Sexual abuse, physical abuse or neglect (Edgeland -whole sample, Bosquet includes women with and without abuse history). | Prospective cohort | Investigate intergenerational pathways (1): to determine whether two groups of mothers, those who broke the cycle of abuse compared to those who did not, differ on dissociative process and symptomatology (Egeland 1996); (2) contrast the incidence of supportive relationships experienced by mothers who continued the cycle by abusing their own child versus those who broke the cycle and provided the child with adequate care (Egeland 1988); and (3) examine whether a maternal history of maltreatment in childhood has a detrimental impact on young children’s mental health and to test theoretically and empirically informed pathways by which maternal history may influence child mental health (Bosquet 2016). | (1) Mothers who were abused and are abusing their children were rated higher on idealization, inconsistency, and escapism in their description of their childhood and they scored higher on the Dissociative Experience Scale compared to mothers who broke the cycle. Mothers who were abused and abused their children recalled the care they received as children in a fragmented and disconnected fashion whereas those who broke the cycle integrated their abusive experience into a more coherent view of self. Even after partialling out the effects of IQ, large differences were found indicating that dissociative process plays a part in the transmission of maltreatment across generations (Egeland 1996). (2) Abused mothers who were able to break the abusive cycle were significantly more likely to have received emotional support from a nonabusive adult during childhood, participated in therapy during any period of their lives, and to have had a nonabusive and more stable, emotionally supportive, and satisfying relationship with a mate. Abused mothers who re-enacted their maltreatment with their own children experienced significantly more life stress and were more anxious, dependent, immature, and depressed (Egeland 1988). (3) Maltreated mothers experienced greater stress and diminished social support, and their children were more likely to be maltreated across early childhood. By age 7, children of maltreated mothers were at increased risk for clinically significant emotional and behavioral problems. A path analysis model showed mediation of the effects of maternal childhood maltreatment history on child symptoms, with specific effects significant for child maltreatment (Bosquet 2016). | Very low |

| 26. Ensink 2016 [75] | Canada (community) | 88 women with uncomplicated pregnancies (All caucasian, mostly college-educated, 66% married). | Pregnancy to 16 months postpartum | Physical, sexual, or emotional abuse (30%) (AAI). | Longitudinal study/ prospective cohort | Investigate intergenerational pathways: from mothers’ RF regarding attachment through parenting to infant attachment. | Mothers’ mentalization regarding their own early attachment relationships was associated with later parenting and infant attachment. Negative parenting behaviours explained the link between mothers’ RF about their own attachment relationships and infant attachment disorganization. | Low |

| 27. Esaki 2008 [76] | USA (East (EA), Midwest (MW), and South (SO) sites, 1991–2004) |

477 mothers categorised as ’high risk’ (80% ’non-white', lean less than high school education, 75% sole parents, 49% reported IPV) | 1, 4, 6 and 8 years postpartum | Physical and sexual abuse | Longitudinal/ prospective cohort | Investigate intergenerational pathways: (1) the relationship between experiences of multiple types of maternal childhood abuse and frequency of perpetration of child maltreatment in adulthood. (2) whether parenting attitude predicts child maltreatment and mediates the relationship between maltreatment history and maltreating one’s own children. (3) the moderating effect of social support on the relationship between maternal childhood abuse and parenting attitude. (4) the role of social support in moderating the relationship experiences of maltreatment and perpetration of child maltreatment. | Multiple types of maternal childhood abuse were significantly associated with increased frequency of perpetration of child maltreatment in adulthood. No mediating role of parenting attitude between maternal childhood abuse and perpetration of child maltreatment in adulthood or for the moderating role of social support on this pathway were found. | Moderate |

| 28a.Fornburg 1996 [77] (28b. Gara 2000) [78] |

USA (inner-city community mental health clinics, early prevention/baby nutrition programs and an early intervention program, New Jersey). |

60 first time mothers with and without abuse (matched case control) (60% African-American, 24% Hispanic) | Less than 6 months postpartum | Physical abuse (AEIII-SD). (50%) | Prospective cohort | Investigate intergenerational pathways: to identify changes in mothers’ perceptions of their baby, in terms of negative and positive attributions, over the course of the first year of the baby’s life. | The abused mothers perceived their baby in significantly less positive terms at age 12 months than they had at age 6 months of the baby. | Very Low |

| 29a.Grote 2012 [20] (29b. Grote 2009 [79]; 29c. Grote 2014 [80]; 29d. Grote 2015 [81]) |

USA (large public obstetrics and gynaecology clinic in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) |

53 women experiencing prenatal depression (70% African-American, >80% completed high school, 50% sole parents). | Pregnancy (T1) to 6 months postpartum (T3). | Emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect (CTQ). | Intervention/RCT | Psychological intervention (compare UC to brief IPT (IPT-B) plus IPT maintenance. | Trauma exposure did not moderate changes in symptoms and functioning over time for women in UC versus IPT-B, suggesting that IPT including maintenance sessions is a reasonable approach to treating depression in this population. Within the IPT-B group, women with more versus less trauma exposure had greater depression severity and poorer outcomes at 3-month post baseline. At 6-month postpartum, they had outcomes indicating remission in depression and functioning, but also had more residual depressive symptoms than those with less trauma exposure, suggesting longer periods of support may be required for women with trauma experiences. | Moderate |

| 30. Harmer 1999 [82] | Australia (substance use treatment centre in the Australian Capital Territory, 1995–1996) | 46 mothers recovering from addiction (predominantly caucasian (3 Indigenous), low-middle income, all sole parents) | 6 months to 12 years age | Negative home environment/neglect, sexual abuse and punishment (62% had experienced abuse) | Cross-sectional study | Investigate intergenerational pathways: association between mothers’ aversive childhood experiences, their subsequent social support in adulthood, psychological distress, parenting stress, and problematic parenting behaviours; and moderating effect of social support. | Mothers in this substance use treatment centre reported very high levels of aversive childhood experiences, psychological distress, parenting stress and use of problematic parenting behaviours along with lower levels of social support. Higher levels of neglect and growing up in a negative home environment were significantly correlated with lower levels of social support from the family, higher levels of distress and parenting stress, and greater use of problematic parenting behaviours. | Low |

| 31. Herronkohl 2013 [83] | USA (child welfare and community centres, 1975–2010) |

268 parents (78% caucasian) | unclear | Physical abuse (severe ’Harsh physical discipline') | Longitudinal/cross-sectional study | Investigate intergenerational pathways: examine evidence of the continuity in abusive discipline across two generations (G1 and G2) and the role of Safe, Stable, and Nurturing Relationships (SSNRs) as protective factors. | Significant predictive association between physical discipline by G1 and G2 parents, after accounting for childhood socioeconomic status and gender. While being physically disciplined as a child was inversely related to reports of having had a caring relationship with one’s mother, only care and support from one’s father predicted a lower risk of harsh physical discipline by G2s. None of the SSNR variables moderated the effect of G1 discipline on G2 discipline. A case-level examination of the abusive histories of G2 harsh discipliners found they had in some cases been exposed to physical and emotional abuse by multiple caregivers and by adult partners. | Moderate |

| 32. Hooper 2004 [84] | UK (North Yorkshire) |

24 mothers with CSA. | unclear | Sexual abuse (whole sample). Many had also experienced other forms of abuse. | Qualitative/interviews | Experience of services: ways in which their good intentions towards their children could be undermined by their experience and environment, with the aim of identifying how this group of mothers could be better supported. | Many issues may affect survivors’ well-being and access to social support and hence their ability to care effectively for their children. For example the impacts of survivors’ issues around attachment, and the impact on children of deterioration in their mothers’ mental health when appropriate services are not available. Ways of supporting both survivors and their children involve greater collective responsibility for children, effective collaboration between mental health services and child-care services, and professional responses which take account of contextual issues. | Moderate |

| 33. Hunter 1979 [85] | USA (Special Care Nursery) |

40 parents of infants born preterm, with a history of childhood abuse and no perpetuation of violence by 12 months postpartum (>60% married). | After birth to 12 months postpartum | Mistreated’ (63% mothers, 55% fathers) | Prospective cohort | Investigate intergenerational pathways: Examine protective factors in ’non-repeating’ families | The mechanisms for change included reliance on a broad network of resources, a degree of self-differentiation, an attitude of realistic optimism, and the ability to marshal extra resources to meet crisis situations. | Very low |

| 34. Iyengar 2014 [86] | USA | 47 first-time mothers (ethnically diverse, majority married). | Pregnancy to 11 months postpartum | Unresolved or resolved trauma and AAI (secure or insecure). | Prospective cohort | Investigate intergenerational pathways: to examine; the process of reorganization on the transmission of attachment across generations; associations between unresolved trauma and mother-child attachment, while testing whether reorganization is associated with more secure child attachment. | Mothers with unresolved trauma had insecure attachment themselves and were more likely to have infants within secure attachment. However, the one exception was that all of the mothers with unresolved trauma who were reorganizing toward secure attachment had infants with secure attachment. | Low |

| 35. Kunseler 2016 [87] | Netherlands (prenatal clinics) |

243 first time mothers, 101 ’at risk’ who reported experiences with youth care or with a psychiatrist or psychologist before the age of 18, and 142 comparison group. (73% Dutch, 58% university educated) | Pregnancy to one year postpartum. | Physical maltreatment, sexual abuse, bizarre punishments of the child, parents’ attempts of suicide, or other frightening behaviours exhibited by parents in presence of the child (AAI). (25%) | Cross-sectional study | Investigate intergenerational pathways: whether women who report abuse in childhood adapt in less resilient ways to challenges to their sense of parenting competence due to infant difficult behaviour than women who report no childhood abuse. | Pregnant women who reported childhood abuse decreased more in Parenting Self Efficacy (PSE) in response to the difficult-to-soothe infant (i.e., failure condition) than pregnant women who reported no abuse, whereas no differences were found in women’s adjustment of PSE to the easy-to-soothe infant (i.e., success condition) or with respect to PSE at baseline. Effects did not vary according to resolution of trauma. | Moderate |

| 36a. Lancaster 2007 [88] (36b. Hill 2000 [89], 36c. Hill 2001 [90]) |

UK | 192 | Unclear | Sexual abuse, physical abuse, psychological abuse, antipathy and neglect. | cross-sectional study | Screening/assessment tool evaluation | The discriminative ability of PBI care scores to predict measures of neglect in the CECA were moderate to high, and the addition of paternal scores did not add to the prediction from maternal scores. Shortened forms of the PBI maternal care scales provided comparable predictions to those from the full scale, particularly three items from the maternal care scale, identified by logistic regression. | Low |

| 37. Leifer 1990 [91] | USA (early-intervention program at the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinic, Chicago) |

1 mother-infant dyad receiving therapy (16 yo African-American living with her mother, living on aid and did not complete high school). | 4 months pp onwards. | Physical and sexual abuse and neglect. | Case study | Psychotherapy description: to illustrate the diagnostic and therapeutic issues in the course of an intervention designed to prevent intergenerational abuse. | Drawing upon an ecological, transactional model of development, the case study utilized a multimethod, longitudinal approach to assess the mother’s history and current psychosocial functioning, the infant’s developmental competence and attachment status, patterns of mother-infant interaction and components of the family’s social ecology. The treatment involved two weekly therapy sessions; one, an individual session for the mother and the other, a session in which mother and infant were seen together. The findings at the one-year evaluation showed improved maternal psychosocial functioning, the infant’s shift from an insecure to a secure attachment classification and improved patterns of mother-infant interactions. | Low |

| 38. Libby 2008 [92] | USA (Southwest and Northern Plains Indian tribes, 1997). |

2221 Indigenous parents (Almost 50% reported financial strain, fathers reported lower social support scales and higher rates of alcohol abuse than mothers) | Up to 13 years of age. | Physical and sexual abuse prior to 13 years of age. | Cross-sectional study | Investigate intergenerational pathways: To examine the relationship of childhood physical and sexual abuse with reported parenting satisfaction and parenting role impairment later in life among American Indians (AIs). | Only substance use, not depression, mediated the relationship between childhood abuse and parenting outcomes. Instrumental and perceived social support significantly enhanced parenting satisfaction; negative social support reduced satisfaction and increased the likelihood of parenting role impairment. Exposure to parental violence while growing up had deleterious effects on parenting outcomes. Mothers and fathers did not differ significantly in the relation of childhood abuse experience and later parenting outcomes. | Moderate |

| 39. Lieberman 2005 [93] | USA (child–parent psychotherapy) |

Ethnically and socioeconomically diverse sample. | Birth to 6 years | Unclear | Qualitative/Clinical record review (AAI transcripts) | Parent strategies to break cycle: examine parental narratives in assessment instruments and clinical notes reflecting on their early years, their relationships with their parents; their thoughts on how these experiences influenced their hopes for their children’s future, to identify early experiences of love, care, and nurturing that might stand out as sources of strength in the parents’ sense of themselves and ability to care for their children. | Authors propose that angels in the nursery—care-receiving experiences characterized by intense shared affect between parent and child in which the child feels nearly perfectly understood, accepted, and loved—provide the child with a core sense of security and self-worth that can be drawn upon when the child becomes a parent to interrupt the cycle of maltreatment. Uncovering angels as growth-promoting forces in the lives of traumatized parents is as vital to the work of psychotherapy as is the interpretation and exorcizing of ghosts. | Very low |

| 40a. Lyons-Ruth 1996 [94] (40b. Lyons-Ruth 1990 [95]) |

USA | 45 mothers (low-income, | After birth to 18 months postpartum | Experiences of witnessing violence, neglect, or physical or sexual abuse (Adult Attachment Interview) (47%). | Longitudinal/prospective cohort | Investigate intergenerational pathways: (associations between childhood trauma and rates of disorganized infant attachment strategies as well as less involved and more hostile maternal caregiving. and mediating role of the continued presence of trauma-related symptoms in adulthood, such as dissociative or post-traumatic symptoms, unresolved trauma on the caregiving and attachment systems.) | A history of physical abuse was associated with increased hostile-intrusive behaviour toward the infant, increased infant negative affect, and a decreased tendency to act on trauma-related symptoms. A history of sexual abuse was associated with decreased involvement with the infant, more restricted maternal affect, and more active reporting of trauma-related symptoms. Infants of mothers who had experienced childhood violence or abuse were not more likely to display insecure attachment strategies than infants of mothers who had not experienced trauma. However, the form of insecure behaviour was significantly different. Insecure infants of violence-exposed mothers displayed predominantly disorganized strategies, whereas insecure infants of mothers with benign childhoods or neglect only displayed predominantly avoidant strategies. | Low |

| 41a. Madigan 2016 [96] (41b. Madigan 2015*[97]) |

Canada (Young Parent Resource Centre in large metropolitan children’s hospital) |

32 adolescent (12–18 yrs) women enrolled in intervention study (49% African-American, 29% caucasian, 13% Hispanic; mean 10 years school; 89% sole parents; 99% living ’below poverty threshold',) | Pregnancy to 12 months postpartum | Emotional Abuse, Physical Abuse, Sexual Abuse, Physical Neglect, and Emotional Neglect (CTQ/AAI). | Prospective cohort | Screening/assessment tool evaluation: Investigate stability of ’unresolved’ (AAI) classification by investigating its stability, as well as exploring predictors of initial levels and rates of change in Unresolved loss and trauma scales across three time points during the developmental transition to parenthood, in a high-risk sample of adolescent mothers. | There is significant stability for the Unresolved classification over the transition to parenthood: Adolescents who were Unresolved prenatally were 8 and 18 times more likely to be classified as Unresolved when their infants were 6 and 12 months old, respectively. On average, there was a steady linear decline in Unresolved loss scores over time, with a rate of change of 27% from the prenatal to 12 months postpartum assessments. There were also significant individual differences in this rate of change. Physical abuse was associated with higher levels of Unresolved loss at the prenatal assessment, and preoccupied attachment attenuated the likelihood of a decline over time in Unresolved loss scores. There was no significant mean rate of change for Unresolved trauma; however, there was considerable variability in scores, with some individuals increasing and others decreasing. Dismissing classifications and a history of sexual abuse were associated with higher levels of Unresolved trauma at the prenatal assessment, and severity of physical abuse was associated with increasing scores of Unresolved trauma over time. | Low |

| 42a. McWey 2013 [98] (42b. McWey 2011 [99]) |

USA | 24 parents notified to CPS (Caucasian (11), African American (10) and Hispanic (3); majority sole parents). | Unclear | Childhood maltreatment (100%). | Qualitative/Interviews | To examine intergenerational patterns of maltreatment and understand: how parents at-risk of losing their children because of maltreatment make connections between their own experiences of maltreatment and their children’s experiences of maltreatment; how they desire to parent differently and / or similarly to their own parents; and how these beliefs are reflected in their behaviours with their children. | Three major categories were identified: patterns, beliefs, and behaviours. A majority of the parents stated that they recognized intergenerational patterns, most expressed that they wanted to be different from their own parents, yet many described parenting actions that were ‘‘destructive.” | Moderate |

| 43. Mohler 2001 [100] | Germany (Parent–Infant Programme at Heidelberg University Clinic) |

1 (case study) | 8 weeks postpartum | Physical abuse | Qualitative/case study | Parent strategies to break cycle: to describe the reactions, attitudes and interactional characteristics of a young mother with a history of abuse, illustrating projective mechanisms in the transmission of a ‘potential for violence’. | Maternal perception of her infant was distorted to the extent that the mother was re-experiencing encounters with her own intrusive and traumatizing mother in the face of her screaming child. She also perceived the infant’s motor impulses as physical attacks on herself and expressed intense anxieties about her daughter’s future aggressive potential. She tried to ward off these anxieties by employing a rigid scheme of rules and obsessively controlling the father’s and grandmother’s interaction with the child. For the success of therapy in this case, ‘containment’ of Mrs L’s needs turned out to be important. However, this also underlined the need for including the partner in the therapy in order to make the abused woman’s striving for acceptance, her narcissistic vulnerability and her mistrust of relationships understandable to the husband. | Moderate |

| 44. Monaghan-Blout 1999 [101] | USA (Massachusetts branch of Parents Anonymous, 1996–1998) |

8 mothers who viewed some aspect of their parenting to be harmful (mostly caucasian and married; 3 did not complete high school; most depressed). | 5 parents between 4 months to 3 years and 3 parents with children under 6 | Emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, physical and emotional neglect, witnessing of the physical abuse of siblings (100%). | Qualitative (Interviews) | Parent strategies to break cycle: investigate the process of resisting the legacy of intergenerational maltreatment as well as explore the ways in which helpers help or fail to help these families as they struggle with the challenges of parenting. | Results suggest that some of the difficulties in helping at risk or maltreating parents may come from an insufficient respect for how the themes developed through a childhood of maltreatment interfere with the establishment of a positive relationship. Key qualities in building a helping alliance were described by the participants, and the good match between client needs and a self/mutual help model were noted. Important aspects of resilient outcomes involved childhood sibling bonds and the successful negotiation of earlier critical events. | Moderate |

| 45a. Montgomery 2015 [102] (45b. Montgomery 2015b [103]) |

UK (maternity service in South England, 2008–2011) |

9 mothers (caucasian, married). | 9 weeks to 28 years postpartum | sexual abuse <16yrs | Qualitative (Interviews) | Experience of services: (1) Explore maternity care experiences of women who were sexually abused in childhood that demonstrate ways that maternity care can be reminiscent of abuse. (2) Inform practice by exploring the impact that childhood sexual abuse has on the maternity care experiences of adult women. | The main themes identified were: women’s narratives of self, women’s narratives of relationship, women’s narratives of context and the childbirth journey. The concept of silence linked all these themes. Women sometimes experienced re-enactment of abuse through intimate procedures but these were not necessarily problematic in themselves. How they were conducted was important. Women also experienced re-enactment of abuse through pain, loss of control, encounters with strangers and unexpected triggers…Maternity care was reminiscent of abuse for women irrespective of whether they had disclosed to midwives and was not necessarily prevented by sensitive care. Recommendations: As staff may not know of a woman’s history, they must be alert to unspoken messages and employ ‘universal precautions’ to mitigate hidden trauma. | Moderate |

| 46a. Murphy 2014 [104] (46b. Steele 2016* [105], 46c. Steele 2010 [106] 46d. Murphy 2013 [107]) |

USA (Bronx, New York, ’clinical’ sample referred with child welfare concerns and a ’community’ sample) |

75–118 mothers (clinical sample contains higher number of African American and Hispanic women who did not complete high school) | Unclear | Emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, household dysfunction (witnessing DV, divorce, mental illness, substance abuse, incarceration) (ACE, CTS, CTQ). | Cross-sectional and prospective study | Assessment tool evaluation (1) Examine relationship between ACE and AAI across both high and low risk populations (Murphy 2014) (2) consider the possible additive effect of ACEs, poverty, and clinical levels of parenting stress (Steele 2016). | (1) ACE responses were internally consistent. In the clinical sample, 84% reported ≥4 ACEs compared to 27% among the community sample. AAIs judged U/CC occurred in 76% of the clinical sample compared to 9% in the community sample. When ACEs were ≥4, 65% of AAIs were classified U/CC. Absence of emotional support in the ACEs questionnaire was associated with 72% of AAIs being classified U/CC. As the number of ACEs and the lack of emotional support increases so too does the probability of AAIs being classified as U/CC. (2) Parenting distress and ACEs were significantly higher in the low SES group; yet, even after controlling for SES, higher ACE scores explained variance in parental distress. | Low |

| 47a. Muzik 2013 [108] (47b. Muzik 2013b* [109], 47c. Seng 2013* [110], 47d. Fava 2016* [14], 47e. Malone 2010* [111], 47f. Malone 1996 [112], 47g. Sexton 2015* [113], 47h Sexton 2017 [114], 47h Seng 2009 [115], 47i Malone 2015 [116], 47j. Swanson 2014* [117], 47k Hairston 2011* [118]) |

USA (Prenatal care clinics in mid-Michigan, 2005–2010) |