Abstract

The Cre-mediated genetic switch combines the ability of Cre recombinase to stably invert or excise a DNA fragment depending upon the orientation of flanking mutant loxP sites. In this work, we have tested this strategy in vivo with the aim to generate two conditional knock-in mice for missense mutations in the Impad1 and Clcn7 genes causing two different skeletal dysplasias. Targeting constructs were generated in which the Impad1 exon 2 and an inverted exon 2* and the Clcn7 exon 7 and an inverted exon 7* containing the point mutations were flanked by mutant loxP sites in a head-to-head orientation. When the Cre recombinase is present, the DNA flanked by the mutant loxP sites is expected to be stably inverted leading to the activation of the mutated exon.

The targeting vectors were used to generate heterozygous floxed mice in which inversion of the wild-type with the mutant exon has not occurred yet. To generate knock-in mice, floxed animals were mated to a global Cre-deleter mouse strain for stable inversion and activation of the mutation. Unexpectedly the phenotype of homozygous Impad1 knock-in animals overlaps with the lethal phenotype described previously in Impad1 knock-out mice. Similarly, the phenotype of homozygous Clcn7 floxed mice overlaps with Clcn7 knock-out mice. Expression studies by qPCR and RT-PCR demonstrated that mutant mRNA underwent abnormal splicing leading to the synthesis of non-functional proteins. Thus, the skeletal phenotypes in both murine strains were not caused by the missense mutations, but by aberrant splicing. Our data demonstrate that the Cre mediated genetic switch strategy should be considered cautiously for the generation of conditional knock-in mice.

Introduction

In the era of big data the question for geneticists is often whether a mutation identified by next generation sequencing in a particular gene can explain the clinical phenotype of the patient. Indeed a crucial issue in biomedical research is to convert sequence information, -omics, analytical and clinical data into knowledge about gene function.

Skeletal dysplasias represent one of the largest classes of birth defects with 436 different disorders that have been clustered in 42 different groups depending on molecular and/or clinical features. More than 350 disease genes have been identified encoding for proteins involved in a wide spectrum of biological functions in cartilage and bone [1, 2]. To shed light on the molecular mechanisms of skeletal disorders, mechanistic studies using in vitro and in vivo approaches are necessary to elucidate the role of the disease gene in the disorder.

Cell cultures, or in vitro studies, provide the first important system to study human diseases, preserving the physiology of living cells and enabling the manipulation under controlled laboratory condition. Patient-derived cells including fibroblasts, induced pluripotent stem cells, primary chondrocytes, osteoblasts and osteoclasts are widely used to model congenital disorders of cartilage and bone [3]; however, their use does not always mirror the whole body condition.

Due to the complexity of skeletal pathologies in vivo models represent a need for the field. Recently, Danio rerio (Zebrafish) has become an appealing animal model to study skeletal development as well as to test drug’s efficacy [4–6], nevertheless nowadays mouse models still represent the gold standard for bone disease modeling since they are anatomically and physiologically close to humans. The mouse genome can be manipulated in many different ways in order to generate models that carry the same disease causing mutation detected in patients [7]. Moreover, patient specific mutations might be helpful to identify genotype-phenotype correlations and differences in the effects of particular mutations.

For more than 20 years the most suitable technique to generate animal models has been based on homologous recombination in murine embryonic stem cells to change the expression of an endogenous gene [8]. The gene-targeting technique has many advantages related to the fact that homologous recombination defines the site of integration and the genetic change in a very specific manner. Gene-targeting can be designed to introduce different genetic modifications such as gene deletions (knock-out), point mutations (knock-in), gene insertions in a certain locus or chromosomal rearrangements.

Knock-out mice can be also generated by the gene trap strategy, which is based on the disruption of an endogenous gene function by the random insertion of an intronic gene-trap cassette [9]. More recently, the genome-editing CRISPR/Cas9 technology has offered a new, quick and cheap way to model genetic disorders [10].

Genetic changes in the germ line might be useful to track the gene function, but may also result in severe developmental consequences complicating or precluding the experimental analysis (i.e. because of embryonic lethality in knock-outs). To overcome these limits related to constitutive expression of the targeting construct, conditional mice expressing the gene modification only at a specific developmental stage or in selected cells have been generated. Different conditional systems are available; among them, the tetracycline (tet) regulatory system and Cre/loxP or Flp/FRT recombination systems are the most widely used [11, 12]. Cre and Flp recombinases mediate different effects on their DNA target sequences including excision, duplication, integration, inversion and translocation depending on the orientation of their specific recognition sequence, namely loxP and FRT, respectively.

However, integration and inversion between wild-type loxP sites is inefficient due to activation of a vicious cycle of re-excision through intramolecular recombination. To overcome such limitation the left element/right element (LE/RE) mutant strategy using LE mutant lox carrying mutations in the left-inverted repeat region and RE mutant lox carrying mutations in the right-inverted repeat region can be used [13, 14]. Recombination between a LE mutant lox and a RE mutant lox results in the generation of a double mutant lox site with mutations in both ends and a wild-type loxP site. The double mutant lox site is no longer a substrate for Cre recombinase; therefore, the recombination reaction proceeds only in the forward direction.

By combining the ability of Cre recombinase to invert or excise a DNA fragment and the use of wild-type and mutant loxP sites, an efficient and reliable Cre-mediated genetic switch has been proposed [15]. Through this strategy expression of a given gene can be turned off, while expression of another one can be simultaneously turned on. This innovative, flexible and powerful approach can be used to easily generate many genetic modifications in a conditional manner [16].

The genetic switch has also been proposed to invert a wild-type exon with a mutated one in order to generate conditional point mutations [14]. In the present work, we have tested this powerful tool to generate two conditional knock-in mice bearing patient specific missense mutations causative of two different skeletal disorders: chondrodysplasia with joint dislocations, gPAPP type and autosomal dominant osteopetrosis type 2 (ADO2).

Materials and methods

Preparation of the gene targeting vectors and generation of mutant mice

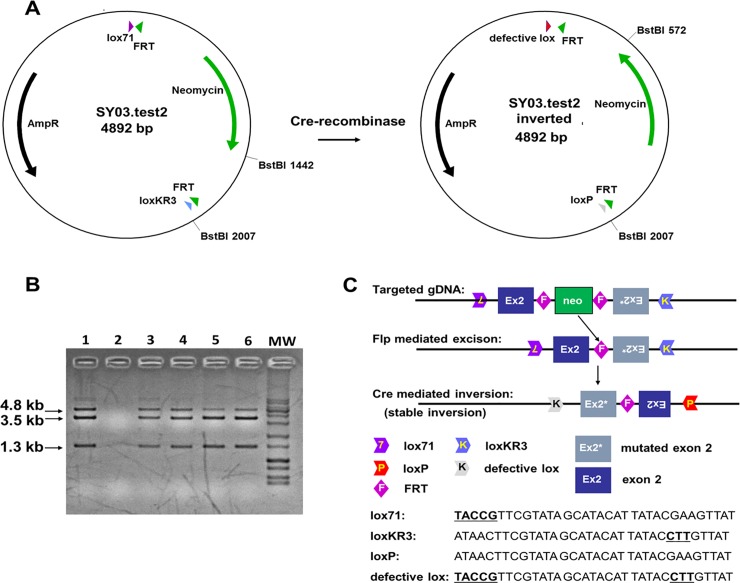

A vector for the stable inversion mediated by Cre-recombinase was generated by gene synthesis with a combination of lox71 as LE mutant loxP (carrying mutations in the left-inverted repeat region) and loxKR3 as RE mutant loxP (carrying mutations in the right-inverted repeat region) in a head-to-head orientation [13]. Different restriction sites were synthesized upstream, downstream and in between the lox sites, to allow insertion of different cassettes. To test the efficiency of the Cre-mediated irreversible inversion we took advantage of an FRT-flanked neomycin resistance cassette cloned between the lox-sites using EcoRV and EcoRI. The resulting vector was transformed in E.coli expressing Cre-recombinase where efficient recombination was confirmed by inversion in vivo.

Subsequently, the lox71/loxKR3 vector was used for the assembly of the Impad1 and Clcn7 conditional knock-in gene targeting constructs. Briefly, the vectors contained homology arms for the Impad1 or Clcn7 genes of about 5 kb and 2.7 kb or 3.7 kb and 2.8 kb, respectively. Between the homologous sequences a duplicated region of the wild-type and mutated exon (exon 2 for Impad1 and exon 7 for Clcn7) were introduced in a head-to-head orientation; exons were flanked by the head-to-head lox71 and loxKR3 sites and separated by an FRT-flanked neomycin cassette (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Strategy for conditional knock-in generation via inversion.

(A) Scheme of the plasmid used to test recombination and stable inversion with lox71 and loxKR3. Magenta arrowhead: lox71; light blue arrowhead: loxKR3; grey arrowhead: loxP; red arrowhead: double mutant lox; green arrowhead: FRT site. (B) Restriction fragment analysis with BstBI of the plasmid (4.8 kb) after transformation in Cre-expressing E.coli. The correctly inverted plasmid results in restriction fragments of 3.5 kb and 1.3 kb. Lanes 1, 3–6: positive clones; lane 2: blank (water); MW: DNA molecular weight marker. (C) Two versions of the targeted exon (wild-type and mutated) are inserted in head-to-head orientation between a loxKR3 and a lox71 site. The two versions of the exon are separated by an FRT-flanked neomycin cassette. After targeting the neomycin cassette is deleted via Flp-mediated recombination in vivo. The mutation is activated by stable inversion of the two exons mediated by Cre-recombinase. The targeted exon in the Impad1 conditional knock-in is exon 2, as shown in the figure, while exon 7 is the targeted exon in the Clcn7 conditional knock-in. The sequences of lox sites used in this study are reported and mutated sequences are indicated by bold and are underlined. Lox71 carries mutations in the left element, while loxKR3 carries mutations in the right element.

The missense mutation knocked in the Impad1 gene was a c.726G>A transition (NM_177730.4) leading to substitution of p.Asp175>Asn in exon 2. This mutation corresponds to the p.Asp177>Asn mutation detected in a patient with chondrodysplasia with joint dislocations, gPAPP type [17]. In addition close to the mutation two silent mutations, c.716T>C and c.719C>T respectively, were inserted to generate a ClaI restriction site useful for animal genotyping.

The missense mutation knocked in the Clcn7 gene was a g.14365G>A transition (NM_011930.4) leading to substitution of p.Gly213>Arg. This mutation corresponds to the most common human mutation, p.Gly215>Arg, detected in patients with ADO2 [18].

Generation of Impad1 and Clcn7 targeted embryonic stem cells and mice

The two targeting vectors bearing the Impad1 or the Clcn7 mutation were electroporated into 2 × 107 C57Bl/6N-based and 129Ola-based ES cells, respectively. After selection with 200 μg/ml neomycin (G418) for 8 days, about 400 ES cell clones were isolated and analyzed via PCR screening.

In both ES cell lines, positive ES cell clones in which correct homologous recombination has occurred were identified via long range PCR and confirmed by Southern blot analysis. A list of all primers used for PCR analyses and for the synthesis of the Southern blot probe (generated by PCR with primers Neo3-for and Neo4-rev) as well as for animal genotyping are reported in S1 Table.

For Impad1 mouse generation, two positive ES cell clones were injected into grey C57Bl/6N derived blastocysts. The resulting chimeras were bred to C57Bl/6N-based Flp-deleter mice (B6gr-Tg(ACTFLPe)9205Dym/NPg) and the resulting black offspring was analyzed by PCR. Several positive mice that lost the FRT-flanked neomycin cassette via Flp-recombination were identified (here called "floxed" mice, Impad1Flox/WT mice). Deletion of the neomycin cassette was demonstrated by PCR using primers Neo3-for and Neo4-rev (S1 Table); moreover, the presence of the floxed allele was confirmed by the presence of the lox71 site checked by PCR with primers SY08.20 and SY08.21. Impad1Flox/WT mice were mated to a Cre mouse strain (B6.FVB-Tg(EIIa-cre)C5379Lmgd) to generate the heterozygous knock-in of the p.Asp175>Asn mutation (Impad1D175N/WT mouse). Correct Cre-mediated switch was checked taking advantage of the insertion of the ClaI restriction site close to the missense mutation. The 480 bp PCR product of the mutant allele obtained using Imp3 and Imp8 primers was digested by ClaI in two restriction fragments of 124 bp and 356 bp, respectively.

For Clcn7 mouse generation, three positive clones were injected into blastocysts from black C57Bl/6N females. The resulting chimeras were bred to C57Bl/6N-based Flp-deleter (B6gr-Tg(ACTFLPe)9205Dym/NPg) mice. The resulting agouti offsprings were then genotyped and several positive mice showing deletion of the neomycin resistance cassette were identified (here called "floxed" mice, Clcn7Flox/WT mice). These were bred further with each other to generate homozygous floxed mice. For animal genotyping the insertion of the lox71 site, used as marker of the mutant allele, was checked by PCR with primers flanking the insertion site (SY03.11 and SY03.12). Deletion of the neomycin cassette was demonstrated by PCR using primers Neo3-for and Neo4-rev (S1 Table).

Animals

Animals were bred and maintained in community housing (≤5 mice/cage, 22° C) on a 12 h light/dark cycle with free access to water and standard pelleted food. Care and use of mice for this study were in compliance with relevant animal welfare institutional guidelines in agreement with EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animals, the Italian Legislative Decree 4.03.2014, n. 26 and the Swiss animal protection act (TschG). The experimental protocols were approved by the Italian Ministry of Health (Animal protocol n. 844/2017-PR and n. 564/2016-PR). Research staff received appropriate training in animal care. Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation before the disease status was considered severe. For genetically modified animals, the evaluation of the severity was based on daily monitoring of the mice behavior, including evaluation of mobility and body weight.

Euthanasia was always done before the animals reached the endpoint, Impad1 knock-in animals died at birth. The Impad1 knock-out strain, generated by Frederick et al. [19] was provided by “The Jackson Laboratories”, Bar Harbor, Maine, USA.

Mouse genotyping

Mice were genotyped by PCR using genomic DNA from mouse tail or ear clips. For animal genotyping of the Impad1 knock-in strain, the mutant allele was detected by digestion with ClaI of a PCR product generated with primers Imp3 and Imp8. The 480 bp PCR product of the mutant allele was digested by ClaI in two restriction fragments of 124 bp and 356 bp, respectively. Genotyping of the Impad1 knock-out strain was performed as described previously [19].

For animal genotyping of the Clcn7 floxed strain SY03.11 and SY03.12 PCR primers were used to genotype homozygous mutant mice from heterozygous and wild-type animals.

X-rays and image analysis

X-ray analyses were performed using a Faxitron MX-20 cabinet X-ray system (Faxitron Bioptics LLC, USA) and X-ray images were digitalized with a Kodak DirectView Elite CR System (Carestream Health Italia, Italy).

Micro computed tomography

Femurs from 3 week-old mice were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 48 hours and then scanned by a μCT SkyScan 1174 (Bruker Italia, Italy). The scan was performed with 6.4 μm resolution at 50 kV. The Skyscan NRecon software was used to reconstruct images with a modified Feldkamp algorithm. Three-dimensional analysis was carried out employing a Marching Cubes type model with a rendered surface [20]. Threshold values were applied for segmenting trabecular bone. Bone trabecular and cortical variables were determined according to Bouxsein et al [21].

Differential skeletal staining with alcian blue and alizarin red

Skeletal staining of newborn mice were performed with alcian blue and alizarin red [22]. Briefly, pups were skinned, dehydrated in 96% ethanol, defatted in acetone and stained with alcian blue and alizarin red. Muscles were removed with 1% KOH in 20% glycerol and preparations were stored in glycerol. Mice were then photographed using a Leica M165 FC stereomicroscope connected to a Leica DFC425 C digital camera (Leica Microsystems, Italy).

qPCR and alternative splicing analysis

Skin from newborn mice was homogenized in 1 ml of QIAzol Lysis Reagent (QIAGEN, Italy) and total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription of 1 μg RNA in a final volume of 20 μl was performed using the SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Italy) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For expression analyses by RT-qPCR, the QuantiFast Primer Assays with validated primer sets for Impad1 and Gapdh (QIAGEN) were used with the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The primer set of Impad1 span exon 2 and 3. Each sample was run in triplicate in 96 well plates in three independent experiments with the MX3000P apparatus (Stratagene, USA). The expression of Impad1 relative to the housekeeping Gapdh gene was obtained by ΔΔCt method.

For alternative splicing detection, total RNA was used for RT-PCR analysis using primers in exon 1 and exon 5 of the Impad1 gene and in exon 6 and 25 of the Clcn7 gene. PCR products were analyzed by 1.5% agarose gels. For DNA sequencing of the spliced forms of Impad1, the PCR products were cloned with the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) followed by Sanger sequencing.

HPLC analysis of cartilage glycosaminoglycan sulfation

For cartilage disaccharide analysis, cartilage was obtained from the femoral heads of newborn mice by careful dissection under the dissection microscope and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) were recovered by papain digestion and cetylpyridinium chloride precipitation as previously described [23]. Purified GAGs were digested with 30 mU of both chondroitinase ABC and chondroitinase ACII (Seikagaku Corp., Japan) in 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 7.35 at 37°C overnight. Released disaccharides were lyophilized and redissolved in 40 μl of 12.5 mM 2-aminoacridone (Invitrogen) in 85% DMSO/15% acetic acid and incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Then, 40 μl of 1.25 M sodium cyanoborohydride in water was added and the mixture was incubated overnight at 37°C. Disaccharides were fractioned with a ProntoSIL HPLC column (4.6 mm × 200 mm, Bischoff Chromatography, Germany) using a linear gradient (0–42% solvent B in 42 min); mobile phases were 0.1 M ammonium acetate, pH 7.0, (Solvent A) and methanol (Solvent B). The analysis was carried out at room temperature with 0.7 ml/min flow rate and the elution profile was monitored by a fluorescence detector (2475 Multy λ Fluorescence Detector, Waters, Italy), with excitation and emission wavelengths of 425 and 525 nm, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out by the software Prism by GraphPad v7.0 and the type of analysis is stated in the figure legends; all results are presented as mean ± SD.

Results

Generation of the Cre mediated switch allele in mice

In order to generate the two conditional knock-in mice, a combination of two partially mutated lox sites in the head-to-head orientation was used. This strategy guarantees stable inversion of DNA between the lox sites since after Cre recombination a wild-type loxP site and a double mutant lox, no longer recognized by the enzyme, are generated (Fig 1A). First the combination lox71 and loxKR3, reported previously by Araki et al [13] in a head-to-head orientation was tested for recombination efficiency in a Cre expressing E.coli strain. Five clones were isolated from each transformation and analyzed via restriction analysis with BstBI. All clones showed the expected restriction pattern corresponding to the inverted version of the test vector (Fig 1B).

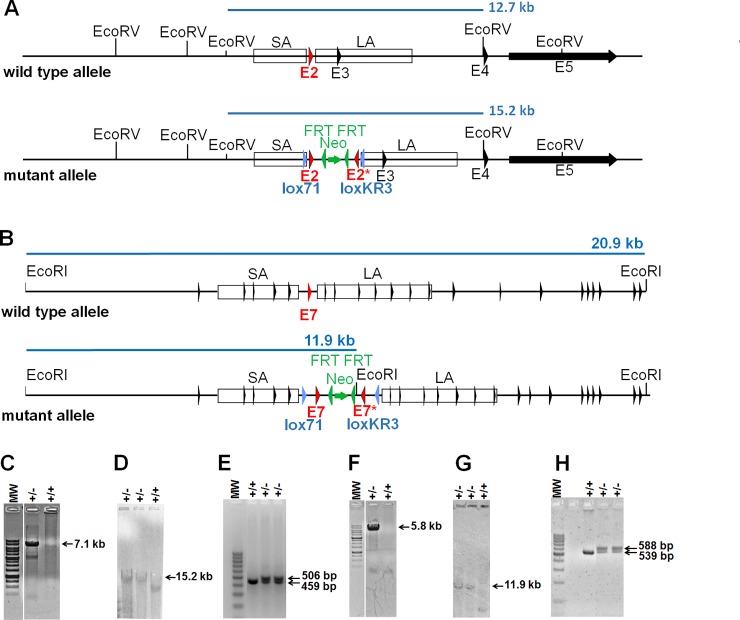

Two gene targeting vectors were generated based on the lox71/loxKR3 construct. The first for an Impad1 mutation (p.Asp175>Asn) and the latter for a mutation in the Clcn7 (p.Gly213>Arg) (Fig 1C and Fig 2A and 2B).

Fig 2. Generation of the Impad1 and Clcn7 mouse lines.

(A) Schematic drawing of the wild-type and targeted loci for Impad1. EcoRV restriction sites and fragments for Southern blot analyses are indicated in light blue. (B) Schematic drawings of the wild-type and targeted loci for Clcn7. EcoRI restriction sites and fragments for Southern blot analyses are indicated in light blue. Exons, indicated by arrowheads, are not numbered to simplify the figure. (C) Long range PCR analysis for correct homologous recombination of ES clones with primers SY08.19 and LRPCRneo1. The expected fragment of 7.1 kb confirms correct homologous recombination in the Impad1 locus. (D) Southern blot analysis of Impad1 targeted ES cells after EcoRV digestion using a neomycin specific probe; the 15.2 kb fragment corresponding to correct homologous recombination is indicated. (E) Genotyping PCR analysis for heterozygous Impad1 floxed pups using primers SY08.20 and SY08.21 flanking the lox71 site. The wild-type and floxed allele result in PCR products of 459 bp and 506 bp, respectively. (F) Long range PCR analysis for correct homologous recombination of ES clones with primers SY03.9 and LRPCRneo1. The expected amplicon of 5.8 kb confirms correct homologous recombination in the Clcn7 locus. (G) Southern blot analysis of Clcn7 targeted ES cells after EcoRI digestion using a neomycin specific probe; the 11.9 kb fragment corresponding to correct homologous recombination is indicated. (H) Genotyping PCR analysis for heterozygous Clcn7 floxed pups using primers SY03.11 and SY03.12 flanking the lox71 site. The wild-type and floxed allele result in PCR products of 539 bp and 588 bp, respectively. Black arrowhead: exon; green arrowhead: FRT site; light blue arrowhead: lox71 or loxKR3 site; red arrowhead: targeted exon 2 in Impad1 or targeted exon 7 in Clcn7; green arrow: neomycin cassette; SA: short arm; LA: long arm; E#: exon number; MW: DNA molecular weight marker.

Homologous recombination was performed in C57Bl/6N-based (Impad1) and 129Ola-based (Clcn7) ES cells and confirmed by long range PCR and Southern blot analysis (Fig 2C and 2D for Impad1 and Fig 2F and 2G for Clcn7). Proper targeted ES cell clones were injected into C57Bl/6N blastocysts and the resulting chimeras were bred to FLP-deleter mice for neomycin cassette deletion. The heterozygous offsprings, here called “floxed” mice (Impad1Flox/WT mice and Clcn7Flox/WT mice, respectively), were then confirmed by the presence of the lox71 site (Fig 2E and 2H) and the deletion of the neomycin cassette based on the absence of a 542 bp fragment after PCR with primers Neo3-for and Neo4-rev.

To generate heterozygous Impad1 knock-in animals (Impad1D175N/WT), Impad1Flox/WT mice were mated to a global Cre mouse strain for stable inversion and activation of the mutation.

Phenotypic characterization of the Impad1 knock-in mouse

Impad1D175N/WT mice did not show any phenotypic alteration by X-ray analysis and visual inspection as human carriers of IMPAD1 mutations and were no further studied.

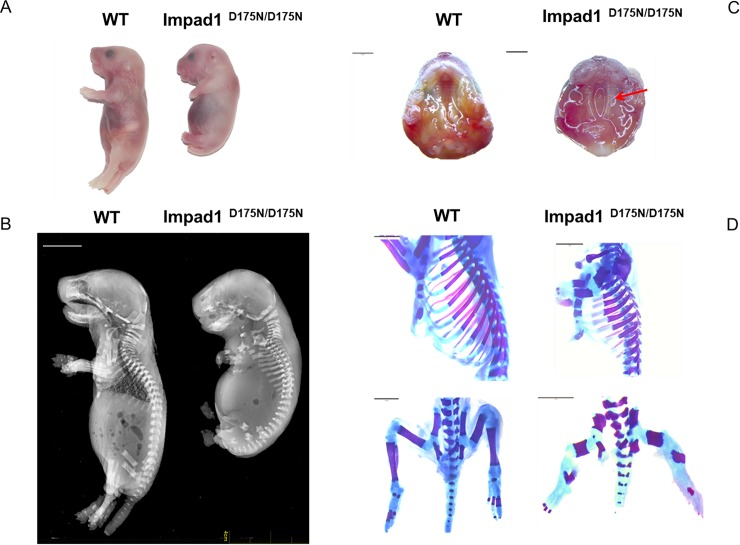

Homozygous mutant (Impad1D175N/D175N) animals died at birth and were smaller compared to wild-type and heterozygous littermates; visual inspection and X-ray analysis demonstrated growth retardation and skeletal defects (Fig 3A and 3B). Mutant animals showed severe hypoplasia of the skeleton; the length of the axial skeleton and of the limbs were reduced. By X-rays and alcian blue and alizarin red skeletal staining, the femur, tibia and fibula were markedly shorter compared to wild-type animals; furthermore, reduced sternal length and diminished rib spacing were evident (Fig 3B and 3D). Moreover, Impad1D175N/D175N mice showed cleft palate already observed in patients with chondrodysplasia with joint dislocations, gPAPP type (Fig 3C).

Fig 3. Phenotypic characterization of the Impad1D175N/D175N mouse.

(A) Gross morphology of wild-type and Impad1D175N/D175N newborn mice. Mutant animals die at birth and are considerably smaller than wild-type littermates demonstrating severe growth retardation. (B) X-rays of wild-type and mutant mice at birth. The mutant shows skeletal defects and growth retardation. (C) In Impad1D175N/D175N mice cleft palate is observed (arrow). Scale bars: 2 mm. (D) Alcian blue and alizarin red skeletal staining of Impad1D175N/D175N and wild-type bones at birth; the femur, tibia and fibula are markedly shorter compared to wild-type animals; rib cages of mutant mice display skeletal defects characterized by reduced sternal length and diminished rib spacing. Scale bars: 2 mm.

Surprisingly, the Impad1D175N/D175N mouse showed the same peculiar phenotype described previously in the Impad1 knock-out mouse [19, 24]. Thus, we further investigated the molecular and biochemical basis causing neonatal lethality in our animal model.

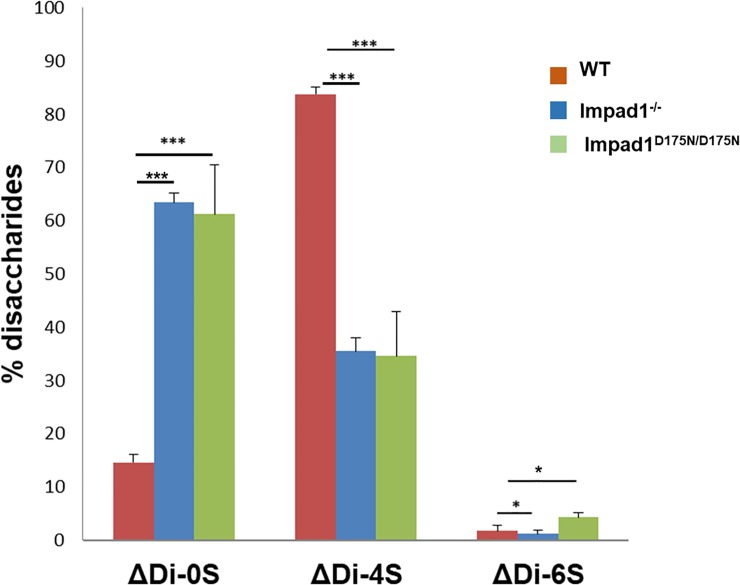

Impad1 encodes for a Golgi 3’-phosphoadenosine 5’-phosphate phosphatase crucial for macromolecular sulfation. In whole embryo and in the limbs of the Impad1 knock-out mouse, severe undersulfation of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans was demonstrated compared to wild-type mice [19, 24]. For this reason, proteoglycan sulfation was measured by HPLC disaccharide analysis in femoral head cartilage of wild-type and Impad1D175N/D175N mice and, for comparison, in the Frederick’s Impad1 knock-out [19]. Glycosaminoglycans were purified by digestion of femoral head cartilage with papain. Then glycosaminoglycans were digested with chondroitinase ABC and ACII and released disaccharides separated by HPLC after derivatization with a fluorescent tag. A dramatic increase in the relative amount of the chondroitin non-sulfated disaccharide (ΔDi-0S) was observed in newborn Impad1D175N/D175N mice compared to wild-type animals indicating chondroitin sulfate undersulfation (61 ± 9.2% and 14 ± 1.6% ΔDi-0S, respectively; P < 0.001 n = 3). Interestingly, the extent of proteoglycan undersulfation in mutant mice was similar to homozygous Impad1 knock-out animals (63 ± 1.6% ΔDi-0S, n = 3) (Fig 4).

Fig 4. Sulfation of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans from femoral head cartilage.

Sulfation of proteoglycans was determined by HPLC disaccharide analysis after digestion by chondroitinase ABC and ACII of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans from the femoral head cartilage of wild-type (WT) and Impad1D175N/D175N mice at birth. In parallel the same analysis was performed also in the Impad1 knock-out (Impad1-/-) mouse studied by Frederick [19]. The amount of non sulfated disaccharide (ΔDi-0S) relative to the total amount of disaccharides (ΔDi-0S, ΔDi-4S and ΔDi-6S) is significantly increased in mutant mice compared to the wild-types indicating proteoglycan undersulfation. Interestingly, the level of proteoglycan undersulfation in mutants is similar to the Frederick’s knock-out mouse. Three mice per group were used; data are reported as mean ± SD (Student’s t-test, *p<0.05; ***p<0.001).

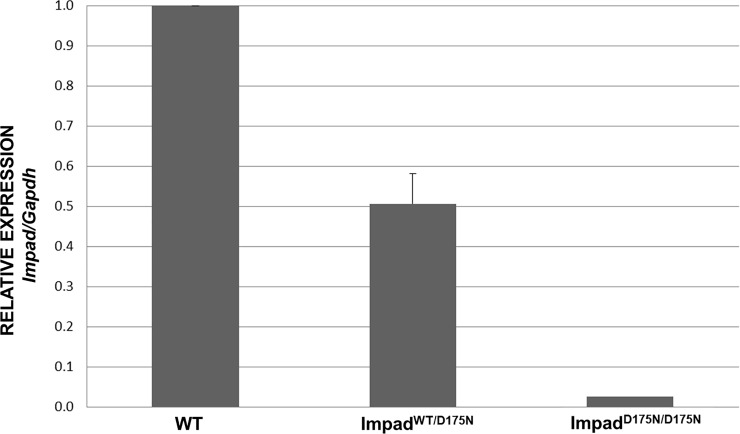

Since the clinical and biochemical phenotype of Impad1D175N/D175N animals overlap with Impad1 knock-outs, the expression of Impad1 was measured by qPCR with primers spanning exons 2 and 3. Impad1 mRNA was barely detectable in Impad1D175N/D175N mice compared with wild-types; Impad1 expression level in heterozygous mice was reduced by half (Fig 5).

Fig 5. Relative expression analysis of the Impad1 gene.

RT-qPCR on total RNA isolated from skin of wild-type (WT), heterozygous (Impad1WT/D175N) and Impad1D175N/D175N newborn mice was performed with primers spanning exon 2 and exon 3. Expression of Impad1 mRNA normalized to Gapdh is absent in homozygous mutant animals compared to wild-types. Three mice per genotype were used; each sample was run in triplicate and three different experiments were performed.

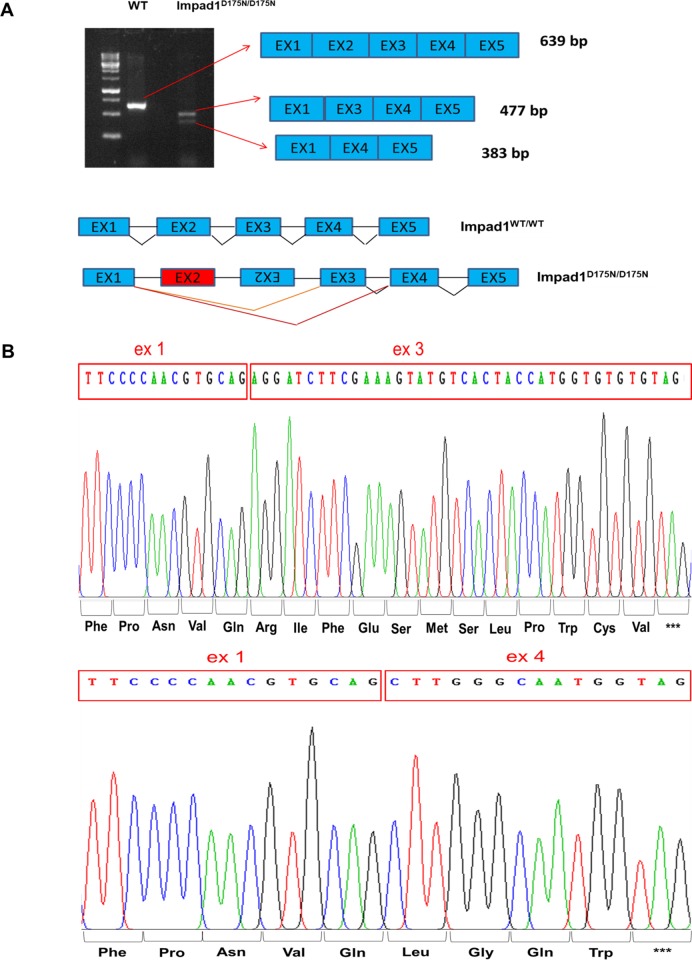

Since in Impad1D175N/D175N mice no Impad1 transcript was detected by qPCR, we checked whether the modified Impad1 locus impairs correct RNA splicing. Thus, we considered potential alternative splicing of Impad1 exons by RT-PCR using primers Imp7 and Imp12 spanning the coding sequence from exon 1 to 5 (Fig 6). Results showed that in wild-type animals one band, 639 bp long, corresponding to a unique transcript including the 5 coding exons was present. This band was not detected in Impad1D175N/D175N mice; conversely two different bands, 477 bp and 383 bp long, respectively, were observed (Fig 6A). Sequencing of the two bands demonstrated that the two transcript variants lack exon 2 or exon 2 and exon 3 (Fig 6B) causing, if translated, frameshift mutations leading to premature stop codons p.Ile128ArgfsX13 and p.Ile128LeufsX5, respectively.

Fig 6. Alternative splicing analysis of Impad1 mRNA.

(A) RT-PCR using primers Imp7 and Imp12 that amplify a region spanning exon 1 to exon 5 was performed from skin total RNA of wild-type and Impad1D175N/D175N newborn mice and analysed by 1.5% agarose gel. In wild-type animals one band, 639 bp long, corresponding to the correctly spliced Impad1 transcript including the 5 coding exons is present. This band is not detected in mutant mice, conversely two different bands, 477 bp and 383 bp long, respectively are observed. (B) Sequencing of the two bands demonstrates that the two transcript variants lack exon 2 or both exon 2 and exon 3.

Retrospectively we noted that Impad1Flox/WT cross breeding resulted in an unusual small litters size. The analysis of some pups found dead at birth revealed their homozygous Impad1Flox/Flox genotype. Furthermore, their X-ray showed the same severe skeletal phenotype observed in Impad1D175N/D175N mice (S1 Fig).

Phenotypic characterization of the Clcn7 floxed mice

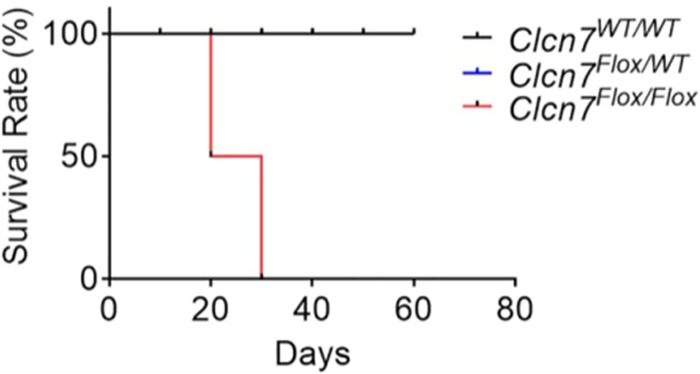

Since the Impad1D175N/D175N phenotype was not due to the missense mutation, but by altered splicing of the modified Impad1 allele, and that aberrant splicing was likely responsible for Impad1Flox/Flox mice unexpected lethal outcome, we checked whether similar modification affected also the Clcn7Flox/Flox mice. For this reason heterozygous Clcn7 floxed mice (Clcn7Flox/WT) were mated together to observe the phenotype in homozygous floxed mice (Clcn7Flox/Flox). Since these mice were not mated yet to a Cre expressing murine strain, inversion of the mutated exon, bearing the p.Gly213>Arg mutation, did not occurr yet and thus no phenotype should have been observed. The Clcn7Flox/Flox mouse presented the phenotypic features of autosomal recessive osteopetrosis. In particular the Clcn7Flox/Flox displayed a phenotype resembling Clcn7 knock-out mice [25], with reduced survival (Fig 7) and a normal Mendelian ratio of genotypes at birth. As expected, no significant changes in survival was found in the heterozygous Clcn7Flox/WT mice (Fig 7).

Fig 7. Survival rate of Clcn7Flox/Flox mice.

Survival rates were calculated following Clcn7WT/WT (black line), Clcn7Flox/WT (blue line) and Clcn7Flox/Flox (red line) mice for 60 days. The Clcn7WT/WT and Clcn7Flox/WT survival rates overlap, for this reason the blue line is not visible in the graph. Survival rate of Clcn7Flox/Flox mice is dramatically reduced. Data are the mean ± SD of 5 mice for each group (Mantel-Cox test).

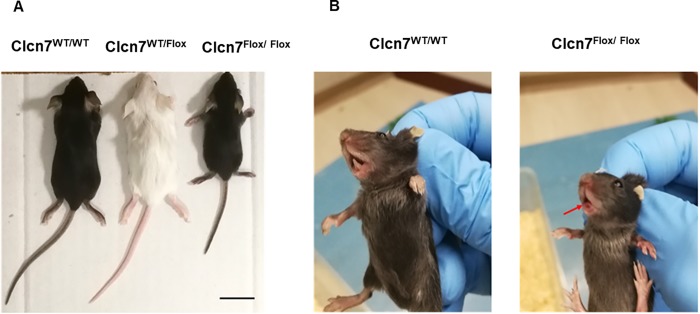

Moreover, Clcn7Flox/Flox mice were shorter than heterozygous and wild-type littermates (Fig 8A) and showed no tooth eruption when compared with wild-type littermates (Fig 8B). Both features are clinical signs of autosomal recessive osteopetrosis.

Fig 8. Clcn7Flox/Flox mouse phenotype.

Twenty-one day old Clcn7WT/WT, Clcn7Flox/WT and Clcn7Flox/Flox mice were evaluated for (A) gross appearance and (B) tooth eruption. Clcn7Flox/Flox mice show reduced skeletal growth and no tooth eruption (the red arrow points to the absence of teeth). Scale bar: 1 cm.

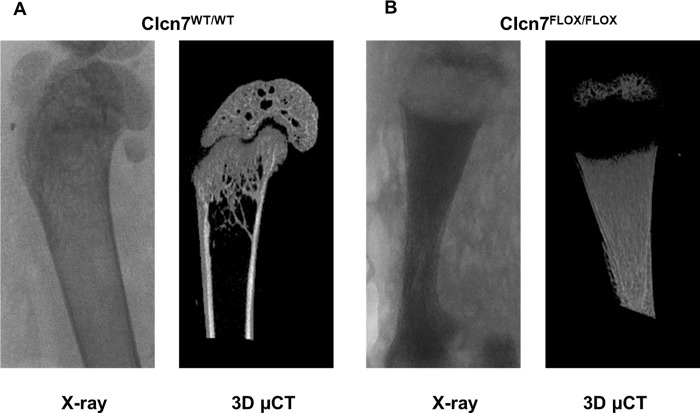

After gross evaluation, femoral bones were analyzed by X-ray and μCT that revealed the 3D architecture of the bones and confirmed a severe osteopetrotic phenotype in Clcn7Flox/Flox mice (Fig 9), with an extremely high bone volume/tissue volume (72 ± 4.3% in Clcn7Flox/Flox and 13 ± 3.2% in wild-type littermates).

Fig 9. Bone phenotype of the Clcn7Flox/Flox mice.

Twenty-one day old (A) Clcn7WT/WT and (B) Clcn7Flox/Flox mice were sacrificed and then X-ray and μCT imaging were performed on femurs. A severe osteopetrotic phenotype with high bone mass is present in mutant mice. Pictures are representative of 5 mice per group.

Altogether, these results revealed that the Clcn7Flox/Flox mouse did not show the expected phenotype, but rather recapitulated the loss-of-function model suggesting that the genomic modification resulted in a knock-out allele.

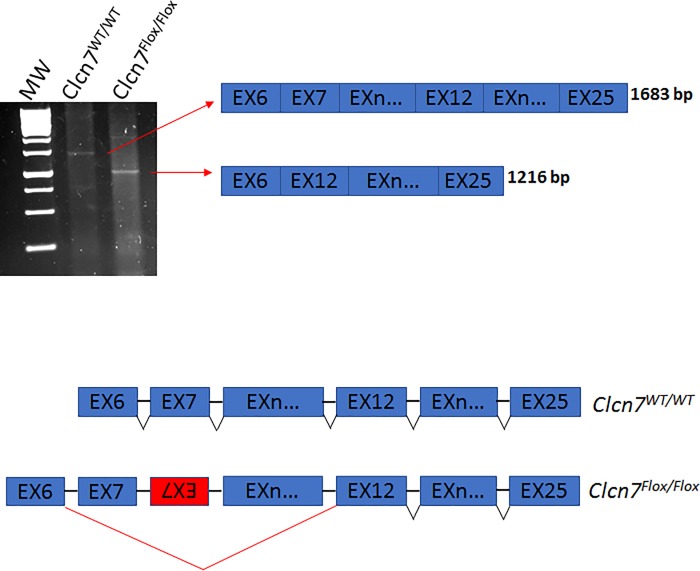

We checked whether the modified Clcn7 locus impairs correct RNA splicing as observed in mutant Impad1. Thus, we considered potential alternative splicing of Clcn7 exons by RT-PCR using primers Clcn7Ex6 and Clcn7Ex25 spanning the coding sequence from exon 6 to 25 (Fig 10). In wild-type animals one band, 1683 bp long, corresponding to a unique transcript including 20 coding exons was present; conversely a band 1216 bp long, lacking exon 7–11 was observed in Clcn7Flox/Flox mice (Fig 10). This should result in an in-frame deletion of 129 amino acid residues.

Fig 10. Alternative splicing analysis of Clcn7 mRNA.

(A) RT-PCR using primers that amplify a region spanning exon 6 to exon 25 was performed from bone total RNA of wild-type (Clcn7WT/WT) and Clcn7Flox/Flox mice and analysed by 1.5% agarose gel. In wild-type animals one band, 1683 bp long, corresponding to the correctly spliced Clcn7 transcript including 20 coding exons is present. This band is not detected in mutant mice, conversely a 1216 bp long band lacking exon 7–11 is observed.

Discussion

We have tested a Cre-mediated genetic switch combining the ability of Cre recombinase to invert a DNA fragment, depending upon the orientation of the flanking loxP sites, and the use of wild-type and mutant loxP sites in order to make recombination irreversible. The notion was that Cre recombinase-mediated inversion would place the exon bearing the missense mutation into a position where it would be spliced properly, while the inverted wild-type exon would be spliced out.

We have used this strategy to generate two conditional knock-in mice for the Impad1 and Clcn7 genes. Mutations in these genes cause in humans two different skeletal disorders: chondrodysplasia with joint dislocations gPAPP type and autosomal dominant or recessive osteopetrosis, respectively. Impad1 encodes for a Golgi resident adenosine 3’,5’-bisphosphate phosphatase crucial for macromolecular sulfation [19, 24], while the Clcn7 gene encodes for the ClC7 protein, a proton/chloride antiporter important in lysosomal acidification [26]. In bone, the ClC7 is expressed especially by osteoclasts and it has a pivotal role in bone resorption, charge-balancing the acidified osteoclast resorption lacuna. The missense mutation knocked-in the murine Impad1 was the p.Asp175>Asn corresponding to the p.Asp177>Asn detected previously in a patient [17]. The mutation knocked-in the murine Clc7 was the p.Gly213>Arg described previously in a patient with ADO2 [27, 28].

Both mouse models generated through this strategy resulted in an unexpected severe skeletal phenotype. Heterozygous floxed Impad1 (Impad1Flox/WT) mice were mated to a Cre deleter mouse strain in order to generate Impad1D175N/WT animals. Impad1D175N/D175N mice died at birth with severe hypoplasia of the skeleton and at the biochemical level cartilage proteoglycans were dramatically undersulfated. The phenotype overlapped with the lethal phenotype described previously in Impad1 knock-out mice generated by a gene trap approach [19, 24]. Expression studies by qPCR and RT-PCR demonstrated that the mutant Impad1 mRNA underwent abnormal splicing with loss of exon 2 or exons 2 and 3; no mutant full length mRNA spanning exons 1–5 as in normal Impad1 mRNA was detected. This may result in the activation of non-sense mediated decay or anyway in the synthesis of transcripts encoding for a non-functional enzyme since the active site of the phosphatase is encoded by exon 2.

A skeletal phenotype was observed also in homozygous Clcn7Floxed/Floxed mice before mating to Cre deleter mice, when the wild-type exon 7 was into a position where it would be spliced properly and thus a wild-type Clcn7 mRNA would have been generated. The skeletal phenotype observed in these mice overlaps with the Clcn7 knock-out reported previously [25]; in fact also in this murine model abnormal splicing causing exons skipping occurred, generating a knock-out allele, likely because of the wild-type and mutant exon 7 in opposite orientation in the mutant Clcn7.

Thus in both animal models the skeletal phenotype parallels the phenotypes of their knock-out mice suggesting that the skeletal defects were not due to the missense mutations, but to aberrant splicing causing the synthesis of non-functional proteins. It is tempting to speculate that the two exons in opposite orientation generate a hairpin loop leading to exon skipping.

A similar strategy was devised previously in order to generate a conditional knock-in of the cAMP response element binding protein (CBP) [14]. To achieve the Cre recombinase-mediated mutation CBPTyr658Ala, a targeting construct containing the wild-type exon 5 of the CBP and a mutated exon 5 (p.Tyr658>Ala) in an inverted orientation was generated. These sequences were flanked by two mutated loxP sites, which were positioned in a head-to-head orientation. The authors demonstrated that in ES cells the genetic switch worked properly when cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing Cre-recombinase, but unfortunately, no data were available regarding the expression at the mRNA or protein level. The generation and further characterization of transgenic animals from these ES cells has never been reported to date.

In conclusion, the Cre mediated genetic switch strategy has paved the way to the engineering of sophisticated genetic modifications including conditional point mutations, conditional rescue, conditional gene replacement and recombinase mediated cassette exchange which have been used successfully in vitro. However, it is worth noting that modifying the genome of eukaryotic cells to generate Cre mediated switch alleles may have some drawbacks. The repetition of endogenous splicing sites in the antisense orientation may also induce the occurrence of aberrantly spliced mRNA. In any case, it is probably safe to reduce DNA repetitions as much as possible and to test for functionality in transiently transfected cells when possible, or in ES cell clones before further proceeding to blastocyst injections.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

The newborn mutant shows severe underdevelopment of the skeleton compared to the wild-type mouse.

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement n. 602300 (SYBIL) (to DS, AF, AT and AR), Fondazione Telethon, Italy (grant n. GEP15062 to AR and GGP14014 to AT), MIUR “Dipartimenti di Eccellenza 2018-2022” (to AF and AR), MIUR “ Progetti di ricerca di rilevante interesse nazionale” (PRIN 2015F3JHMB to AT and AR) and “Fondo di finanziamento per le attività base di ricerca” (FFABR to MC). Animal model development at PolyGene AG was performed as a directly funded, nonprofit activity aimed at delivering animal models to partner groups in the European SYBILconsortium. No financial profit except funded remuneration for the works performed was generated, and no intellectual property was obtained. The SYBIL Grant Agreement retains no rights for animal models to PolyGene AG. The funders provided support in the form of salaries for authors SS, CP and LM, but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section.

References

- 1.Krakow D. Skeletal dysplasias. Clin Perinatol. 2015;42(2):301–19, viii. Epub 2015/06/05. 10.1016/j.clp.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonafe L, Cormier-Daire V, Hall C, Lachman R, Mortier G, Mundlos S, et al. Nosology and classification of genetic skeletal disorders: 2015 revision. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167(12):2869–92. 10.1002/ajmg.a.37365 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neben CL, Roberts RR, Dipple KM, Merrill AE, Klein OD. Modeling craniofacial and skeletal congenital birth defects to advance therapies. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(R2):R86–r93. Epub 2016/06/28. 10.1093/hmg/ddw171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gioia R, Tonelli F, Ceppi I, Biggiogera M, Leikin S, Fisher S, et al. The chaperone activity of 4PBA ameliorates the skeletal phenotype of Chihuahua, a zebrafish model for dominant osteogenesis imperfecta. Human Molecular Genetics. 2017;26(15):2897–911. 10.1093/hmg/ddx171 WOS:000405706800008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiedler I, Schmidt F, Wölfel E, Plumeyer C, Milovanovic P, Gioia R, et al. Severely Impaired Bone Material Quality in Chihuahua Zebrafish Resembles Classical Dominant Human Osteogenesis Imperfecta. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2018;33(8):1489–99. 10.1002/jbmr.3445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Andrea CE, Prins FA, Wiweger MI, Hogendoorn PC. Growth plate regulation and osteochondroma formation: insights from tracing proteoglycans in zebrafish models and human cartilage. J Pathol. 2011;224(2):160–8. Epub 2011/04/21. 10.1002/path.2886 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garofalo S, Horton WA. Genetic-engineered models of skeletal diseases. II. Targeting mutations into transgenic mice chondrocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;137:491–8. Epub 2000/08/19. 10.1385/1-59259-066-7:491 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capecchi MR. Gene targeting in mice: functional analysis of the mammalian genome for the twenty-first century. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6(6):507–12. Epub 2005/06/03. 10.1038/nrg1619 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley A, Anastassiadis K, Ayadi A, Battey JF, Bell C, Birling MC, et al. The mammalian gene function resource: the International Knockout Mouse Consortium. Mamm Genome. 2012;23(9–10):580–6. Epub 2012/09/13. 10.1007/s00335-012-9422-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birling MC, Herault Y, Pavlovic G. Modeling human disease in rodents by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Mamm Genome. 2017;28(7–8):291–301. Epub 2017/07/06. 10.1007/s00335-017-9703-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bockamp E, Maringer M, Spangenberg C, Fees S, Fraser S, Eshkind L, et al. Of mice and models: improved animal models for biomedical research. Physiol Genomics. 2002;11(3):115–32. Epub 2002/12/05. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00067.2002 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bockamp E, Sprengel R, Eshkind L, Lehmann T, Braun JM, Emmrich F, et al. Conditional transgenic mouse models: from the basics to genome-wide sets of knockouts and current studies of tissue regeneration. Regen Med. 2008;3(2):217–35. Epub 2008/03/01. 10.2217/17460751.3.2.217 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Araki K, Okada Y, Araki M, Yamamura K. Comparative analysis of right element mutant lox sites on recombination efficiency in embryonic stem cells. BMC Biotechnol. 2010;10:29 Epub 2010/04/02. 10.1186/1472-6750-10-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Z, Lutz B. Cre recombinase-mediated inversion using lox66 and lox71: method to introduce conditional point mutations into the CREB-binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(17):e90 Epub 2002/08/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnutgen F, Doerflinger N, Calleja C, Wendling O, Chambon P, Ghyselinck NB. A directional strategy for monitoring Cre-mediated recombination at the cellular level in the mouse. Nat Biotechnol. 21 United States2003. p. 562–5. 10.1038/nbt811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnutgen F, Ghyselinck NB. Adopting the good reFLEXes when generating conditional alterations in the mouse genome. Transgenic Res. 2007;16(4):405–13. Epub 2007/04/07. 10.1007/s11248-007-9089-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vissers LE, Lausch E, Unger S, Campos-Xavier AB, Gilissen C, Rossi A, et al. Chondrodysplasia and abnormal joint development associated with mutations in IMPAD1, encoding the Golgi-resident nucleotide phosphatase, gPAPP. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(5):608–15. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.002 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alam I, Gray AK, Chu K, Ichikawa S, Mohammad KS, Capannolo M, et al. Generation of the first autosomal dominant osteopetrosis type II (ADO2) disease models. Bone. 2014;59:66–75. Epub 2013/11/05. 10.1016/j.bone.2013.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frederick JP, Tafari AT, Wu SM, Megosh LC, Chiou ST, Irving RP, et al. A role for a lithium-inhibited Golgi nucleotidase in skeletal development and sulfation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(33):11605–12. 10.1073/pnas.0801182105 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorensen WE, Cline HE. Marching cubes: A high resolution 3D surface construction algorithm. ACM SIGGRAPH Comput Graph. 1987;21:163–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouxsein ML, Boyd SK, Christiansen BA, Guldberg RE, Jepsen KJ, Muller R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(7):1468–86. Epub 2010/06/10. 10.1002/jbmr.141 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forlino A, Piazza R, Tiveron C, Della Torre S, Tatangelo L, Bonafe L, et al. A diastrophic dysplasia sulfate transporter (SLC26A2) mutant mouse: morphological and biochemical characterization of the resulting chondrodysplasia phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(6):859–71. 10.1093/hmg/ddi079 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monti L, Paganini C, Lecci S, De Leonardis F, Hay E, Cohen-Solal M, et al. N-acetylcysteine treatment ameliorates the skeletal phenotype of a mouse model of diastrophic dysplasia. Human Molecular Genetics. 2015;24(19):5570–80. 10.1093/hmg/ddv289 WOS:000363018100015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sohaskey ML, Yu J, Diaz MA, Plaas AH, Harland RM. JAWS coordinates chondrogenesis and synovial joint positioning. Development. 2008;135(13):2215–20. 10.1242/dev.019950 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kornak U, Kasper D, Bosl MR, Kaiser E, Schweizer M, Schulz A, et al. Loss of the ClC-7 chloride channel leads to osteopetrosis in mice and man. Cell. 2001;104(2):205–15. Epub 2001/02/24. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graves AR, Curran PK, Smith CL, Mindell JA. The Cl-/H+ antiporter ClC-7 is the primary chloride permeation pathway in lysosomes. Nature. 2008;453(7196):788–92. Epub 2008/05/02. 10.1038/nature06907 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waguespack SG, Koller DL, White KE, Fishburn T, Carn G, Buckwalter KA, et al. Chloride channel 7 (ClCN7) gene mutations and autosomal dominant osteopetrosis, type II. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(8):1513–8. Epub 2003/08/22. 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.8.1513 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capulli M, Maurizi A, Ventura L, Rucci N, Teti A. Effective Small Interfering RNA Therapy to Treat CLCN7-dependent Autosomal Dominant Osteopetrosis Type 2. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2015;4:e248 Epub 2015/09/02. 10.1038/mtna.2015.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

The newborn mutant shows severe underdevelopment of the skeleton compared to the wild-type mouse.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.