Abstract

Background:

Walker and Goldsmith's classic article on fetal hip joint development reported that neck/shaft angle did not change from 12 weeks of gestational age through term while version increased from 0 to 40 degrees. This suggests no change in coronal alignment during development, a conclusion we dispute. By re-examining their data, we found that the true neck/shaft angle (tNSA) decreased by 7.5 degrees as version increased by 40 degrees from 12 weeks of gestational age to term.

Methods:

Four investigators measured both femoral version and neck-shaft angle from photographs published by the authors of femurs at multiple stages of maturation from 12 weeks of gestational age to term. The tNSAs and inclination angles were calculated for each femur illustrated using previously validated formula. Changes in the morphology of the femur over time were analyzed using a Student t test. Interobserver and intraobserver reliability were also determined by the Pearson R coefficient.

Results:

As reported by Walker and Goldsmith, apparent neck/shaft angle (aNSA) did not significantly change during maturation, whereas version increased by 40 degrees. However, tNSA decreased by 7.5 degrees during maturation, while the inclination increased by 32 degrees over the same period. This paper demonstrates angular changes in both the coronal and transverse planes with a 4:1 ratio of angular change in the transverse and coronal planes respectively. Interobserver Pearson coefficient R=0.98 and an intraobserver Pearson coefficient R=0.99.

Conclusions:

Although Walker and Goldsmith reported angular changes only in the transverse plane, we conclude that they identified angular changes in both the coronal and transverse planes. Here we show it is mathematically necessary for tNSA to decrease, if aNSA remains constant as version increases.

Clinical Relevance:

A reader who is not well versed in the difference between aNSA and tNSA or version and inclination cannot appreciate what Walker and Goldsmith presented. Surgeons operating on the proximal femur also benefit from understanding these distinctions.

Key Words: fetal development, femur, osteology

The geometric relationship between femoral version and neck-shaft angle is important for understanding the morphology and biomechanics involved in hip function.1 Previous studies by Drs Walker and Goldsmith2 tremendously increased the understanding of the morphological changes seen in the developing fetal hip but did not properly address the difference between apparent measures and actual measurements in the coronal and transverse planes.3 This led to the faulty conclusion that there is no change in coronal alignment during gestation.

Liu et al4 emphasizes the difference between apparent and actual measurements in the coronal and transverse planes by differentiating between true neck/shaft angle (tNSA) and apparent neck/shaft angle (aNSA) as well as inclination and version. The tNSA is measured with the femoral neck perpendicular to the viewer. The same applies to inclination. As such, both provide anatomic angles in the coronal and transverse planes, respectively. aNSA and version both present the femoral neck axis obliquely to the viewer (unless version is 0 in the former case and the neck/shaft angle is 90 degrees in the later). This makes it impossible to precisely measure coronal and transverse plane anatomy because the length of the neck will be distorted in these projected views.

For example, version is one of the factors that determine hip rotation. However, version cannot be used to represent inclination unless the femoral neck is perpendicular to the femoral shaft (Fig. 1). In any other configuration, the trajectory of the femoral neck out of the transverse plane artificially shortens the projection seen in the transverse plane. Equating version and inclination in such a case would overestimate the inclination. To directly measure inclination, one would have to abduct the femur until the axis of the femoral neck aligned with the transverse plane allowing the full length of the femoral neck to be appreciated (Fig. 2). When schematized, the difference between determining femoral version and femoral inclination involves the angle at which the camera captures the femur such that the version view is exactly parallel to the femoral shaft, whereas the inclination view is directly perpendicular to the femoral neck (Fig. 3). The difference between the 2 views can be appreciated when considering how proximal femoral landmarks appear on these views as depicted by the numbers also in Figure 3. Such a correction is of clinical importance in guiding surgeons on how much to “drop the hand” in the dorsal/ventral direction when placing hardware into the femoral neck.

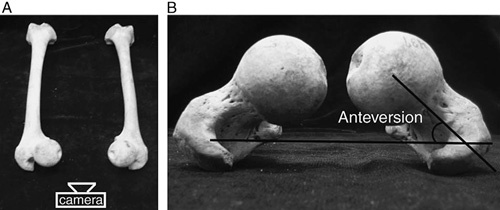

FIGURE 1.

As it appears in Liu et al, (A) demonstrates 2 femurs and the positioning of the viewer to measure version on a transverse plane perpendicular to the long axis of the femur. B, Version measured in the transverse plane with one line parallel to the bicondylar plane and the other parallel to the femoral neck axis.

FIGURE 2.

As it appears in Liu et al, (A) demonstrates 2 femurs abducted until the femoral neck axis lies entirely in the transverse plane. B, The inclination measured as the angle between the bicondylar plane and the femoral neck axis. Because the viewpoint is adjusted so that length of the femoral neck is fully appreciated, inclination is not affected by the neck-shaft angle. aNSA indicates apparent neck/shaft angle.

FIGURE 3.

A schematic representation of the difference in measuring femoral version and femoral inclination. Landmarks in the proximal femur including the femoral head (1), femoral neck (2), greater trochanter (3), and femoral shaft (4) are annotated on all views presented. Left—inclination view: the shaft of the femur is abducted until the femoral neck is perpendicular to the viewer. Right—version view: the shaft of femur is parallel to the beam of the camera, so it is invisible to the viewer. The femoral neck is oblique to the viewer.

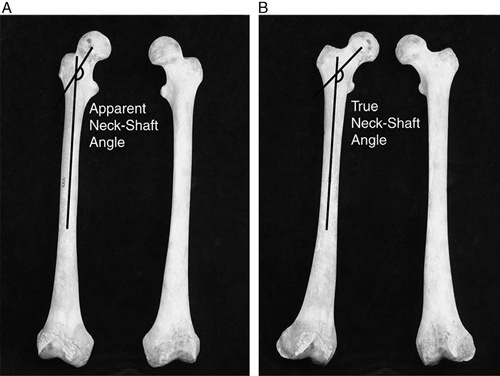

As regards neck-shaft angles, aNSA is affected by version. Ideally, the femoral neck-shaft angle would be measured with the axes of the femoral shaft and neck in the coronal plane, describing a femur with 0 degrees of version. As version increases, the projected length of the femoral neck is shortened leading to an increase in the projected neck-shaft angle. For the purposes of discussion, neck-shaft angle measured off the coronal projection of the femur will be called the “apparent” NSA while the angle corrected for version will be called the “true” NSA (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

As it appears in Liu et al, (A) demonstrates 2 femurs resting in the anatomic position. The apparent neck-shaft angle is measured in the coronal plane. B, Rotates the femurs so that the femoral neck is fully in the coronal plane. Because the femurs are rotated in this manner, version is eliminated. The full length of the femoral neck is appreciated and it is possible to measure the true neck-shaft angle directly.

The relationship between inclination, version, aNSA, and tNSA have been investigated in the setting of femoral derotation osteotomies4 but have not been previously described in the literature with regard to morphology of the developing fetal hip. We will reinterpret the classic work of Walker and Goldsmith by accounting for version, inclination, aNSA, and tNSA. In this way, we can describe both the apparent as well as the actual, anatomic relationships seen during gestation.

METHODS

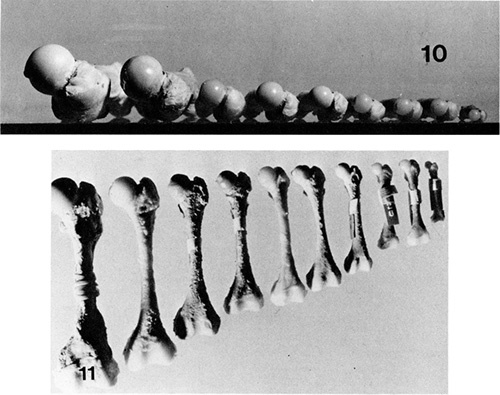

Walker and Goldsmith, in their paper entitled “Morphometric study of the fetal development of the human hip joint2,” acquired 140 fetuses (66 male, 74 female) from the Pathology and Anatomy Departments in Canada and the United States that were the products of elective abortions (62.2%), stillbirths (23.7%), or death during the perinatal period (14.1%). Their specimens ranged from 12 to 42 weeks of age and had no evidence of malformation, minimal maceration, and normal hip morphology by gross examination and under ×10 magnification. In their analysis of age on the developing hip, they measured femoral torsion and the aNSAs of developing femurs with 9 and 10 representative specimens shown in figures 10 and 11 of their paper respectively (Fig. 5). All femurs shown in those figures were right femurs. Femoral version and aNSAs of the specimens that are shown in those 2 figures were measured twice by 4 investigators ranging from medical student to attending. Note that the full set of specimens were not used, instead the study focused on the representative images provided. Inclination and tNSAs were calculated by mathematically manipulating formulas as outlined by Liu and colleagues:

FIGURE 5.

Walker and Goldsmith’s representative sample of developing fetal femoral version and neck-shaft angle. From Walker and Goldsmith,2 with permission from the Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine.

Changes in version, inclination, aNSAs, and tNSAs over time were analyzed by Student t test with α=0.05. Interobserver and intraobserver reliability was determined by Pearson’s R coefficient.

RESULTS

In congruity with previous work by Walker and Goldsmith, aNSA did not significantly change over development [95% confidence interval (CI), −1.83 to 3.33 degrees, P=0.59] while version increased by an average of 40 degrees (95% CI, +36.57 to +44.93 degrees, P<0.001). However, the tNSA significantly decreased over time by an average of −7.5 degrees (95% CI, −10.20 to −4.58 degrees, P=0.002) and the inclination increased by an average of 32 degrees (95% CI +30.57 to 33.72 degrees, P<0.001). The interobserver Pearson coefficient R=0.98 and the intraobserver Pearson coefficient R=0.99.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to elaborate on the findings of Walker and Goldsmith with regard to the morphology of the developing fetal hip. To better understand the changes in the developing joint, one must consider the 3-dimensional relationships between femoral version, inclination, and neck-shaft angle and how such relations are traditionally not fully accounted for when directly measuring off of transverse or coronal projections of the femur on standard radiographs with the femur in the anatomic position.

Version should not be used as a substitute for inclination unless the femoral neck and shaft are perpendicular, placing the femoral neck fully in the transverse plane. Any deviation of the femoral neck out of the transverse plane in the superior or inferior direction would lead to a shortening of the projection of the femoral neck in the transverse plane and an overestimation of inclination. Readers who have not previously been introduced to this concept may benefit from an in-depth review of Liu et al4 where these concepts are presented in detail. In addition, the direct measurement of the neck-shaft angle on a radiograph is most likely an overestimation of the actual neck-shaft angle. As version increases, the projection of the femoral neck in the coronal plane is also shortened leading to an increase in the aNSA, therefore overestimating tNSA.

After accounting for these spatial relationships, we examined the representative developing fetal femurs displayed in Walker and Goldsmith’s study. Our findings are consistent with theirs with respect to a significant increase in version and no significant change in aNSA during fetal development. Elaborating on their findings, we concluded that the 40 degrees change in version in the presence of no change in the aNSA is comprised of a significant −7.5 degrees change in tNSA and a +32 degrees change in inclination. When interobserver and intraobserver observations were plotted against each other, the Pearson Coefficients were R=0.98 and 0.99, respectively, indicating this set of observations was reliable among different observers and repeat observations. One potential weakness of the study is that only a selected sample rather than the full set of specimens were measured; however, the extremely high degree of correlation as well as the small SDs reported in the original paper suggest that additional measurements would closely replicate the findings detailed here.

In conclusion, Walker and Goldsmith made classic observations concerning changes in hip morphology from 12 weeks of gestational age to term. They demonstrated changes in both the coronal and transverse morphology of the femur over time, but the existence of that reality and its extent are lost on a reader who is not well versed in the difference between aNSA and tNSA, version and inclination. These 4 concepts are useful for tracking anatomic as well as apparent changes in the shape of the developing hip joint.5–7

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Archibald HD, Petro KF, Liu RW. An anatomic study on whether femoral version originates in the neck or the shaft. J Pediatr Orthop. 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker JM, Goldsmith CH. Morphometric study of the fetal development of the human hip joint: significance for congenital hip disease. Yale J Biol Med. 1981;54:411–437. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuller CB, Farnsworth CL, Bomar JD, et al. Femoral version: comparison among advanced imaging methods. J Orthop Res. 2018;36:1536–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu RW, Toogood P, Hart DE, et al. The effect of varus and valgus osteotomies on femoral version. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29:666–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lerch TD, Todorski IAS, Steppacher SD, et al. Prevalence of femoral and acetabular version abnormalities in patients with symptomatic hip disease: a controlled study of 538 hips. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:122–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paton RW. Screening in Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH). Surgeon. 2017;15:290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw BA, Segal LS. Evaluation and referral for developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants. Pediatrics. 2016;138:6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]