Abstract

miR-214 has been recently found to be significantly downregulated in calcified human aortic valves (AVs). ER stress, especially the ATF4-mediated pathway, has also been shown to be significantly upregulated in calcific AV disease. Since elevated cyclic stretch is one of the major mechanical stimuli for AV calcification and ATF4 is a validated target of miR-214, we investigated the effect of cyclic stretch on miR-214 expression as well as those of ATF4 and two downstream genes (CHOP and BCL2L1). Porcine aortic valve (PAV) leaflets were cyclically stretched at 15% for 48 hours in regular medium and for one week in osteogenic medium to simulate the early remodeling and late calcification stages of stretch-induced AV disease, respectively. For both stages, 10% cyclic stretch served as the physiological counterpart. RT-qPCR revealed that miR-214 expression was significantly downregulated during the late calcification stage, whereas the mRNA expression of ATF4 and BCL2L1 was upregulated and downregulated, respectively, during both early remodeling and late calcification stages. When PAV leaflets were statically transfected with miR-214 mimic in osteogenic medium for 2 weeks, calcification was significantly reduced compared to the control mimic case. This implies that miR-214 may have a protective role in stretchinduced calcific AV disease.

Keywords: cyclic stretch, miR-214, aortic valve, calcification

Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is one of the most prevalent valvular diseases in the world, affecting more than 12% of the elderly population41. The primary reasons of AS are AV fibrosis10 and calcification45. Currently, there are no therapeutic drugs available to treat this disease29 and the only treatment options are surgical or transcatheter AV replacement55. However, these procedures entail several complications, such as bleeding21, thrombosis9, etc.

It has been well established that mechanical forces (such as stretch and shear) play a key role in AV pathogenesis1, 4, 22. For example, both elevated mechanical stretch (15%) and low, oscillatory shear stress (i. e. disturbed flow; ± 5 dynes/cm2) have been shown to promote AV calcification3, 48. However, high mechanical stretch induces 5-fold higher AV calcification compared to low, oscillatory shear stress46, implying that elevated mechanical stretch has a more pronounced effect on AV calcification than disturbed flow. Interestingly, 15% stretch was also found to correspond to a hypertensive condition in AV73, with hypertension being one of the major risk factors for calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD)44. Hence, 15% stretch is considered to represent the pathological level of mechanical stretch, whereas 10% stretch is representative of the physiological level58, 73.

In the pursuit of effective therapeutics to treat CAVD, manipulation of microRNA (miRNA) expression levels by miRNA mimic or inhibitor has recently emerged as an exciting candidate62. miRNAs are small (~ 22 nucleotides in length) non-coding RNAs that modulate gene expression by silencing their targets24. Due to their role in modulating gene expression, miRNAs have been widely considered as a potential therapeutic option for different diseases, such as cancer51. Interestingly, calcified human AVs have distinct miRNA expression profiles compared to healthy AVs13, 56, 65. However, considering the hundreds of potential miRNAs for therapeutic application in CAVD, identification of the most effective ones is a critical first step. To this end, mechanosensitive miRNAs are promising, given that perturbations to mechanical stimuli promote AV pathogenesis1, 4, 22. In recent years, several studies have focused on the identification of shear-sensitive miRNAs and their functional relations to CAVD25, 28, 47. However, stretch-sensitive miRNAs relevant to CAVD remain to be identified or functionally described42, even though elevated mechanical stretch induces increased AV calcification compared to disturbed flow46. In a recent study42, it was found that 14% stretch downregulated the expression of miR-148a-3p in human aortic valve interstitial cells (HAVICs) compared to static condition. This downregulation resulted in increased expression of IKBKB (a target of miR-148a-3p) and activation of downstream inflammatory signaling. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated the effects of physiological and pathological stretch on miRNA expression in AV to date.

Among the plethora of discovered miRNAs so far, miRNA 214 (or miR-214) is one of the most studied miRNAs, especially in cancer59, 70. miR-214 (along with miR-199a) is encoded by the opposite strand of DNM3 (DNM3os)15, 66 and well known to inhibit osteogenesis34, 53, 69. In line with the anti-osteogenic effect, miR-214 expression was found to be downregulated in calcified human AVs compared to healthy AVs13, 56, 65.Recently, miR-214 was found to be shear-sensitive in AV47. However, the functional role of miR-214 in stretch-induced AV calcification is not known. To this end, Activating Transcription Factor 4 or ATF4 may play a key role in mediating the effect of miR-214 in AV calcification. ATF4, which is one of the major targets of miR-21464, is a component of the PERK-eIF2α signaling pathway, which is one of the three endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathways27. These pathways significantly regulate cellular processes like inflammation19, apoptosis43, etc. Interestingly, ER stress has been shown to promote AV calcification, in which the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 signaling pathway plays a major role8, 63. Mechanical stretch has been found to promote inflammation and apoptosis in smooth muscle cells via induction of ER stress30. Under ER stress, both transcription and translation of ATF4 are increased, resulting in cell death situations via upregulation of C/EBP-Homologous Protein or CHOP expression16.

Interestingly, ATF4 has been shown to promote mineralization in vascular smooth muscle cells36, osteoblasts68, mesenchymal stem cells74, etc. On the other hand, CHOP has been shown to have a potentially repressive effect on the expression of pro-survival gene Bcl-2-Like Protein 1 or BCL2L1 under apoptotic conditions20. Hence, considering the anti-osteogenic effect of miR-214 and pro-osteogenic effect of ATF4, this study investigates the role of miR-214 in stretch-induced AV calcification, especially focusing on the ATF4/CHOP/BCL2L1 pathway.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Simulation of Different Stages of Stretch-Induced Calcific Aortic Valve Disease (CAVD)

The cyclic stretch bioreactor [Supplemental Figure 1] used in this study was previously validated in our laboratory2, 3. An ex vivo experimental approach using porcine aortic valves (PAVs)2, 3, 47 was adopted as it incorporates the contributions from both valvular endothelial cells (VECs) and valvular interstitial cells (VICs). Cyclic stretch experiments were carried out to simulate two different stages of stretch-induced calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD), namely, early remodeling and late calcification. Stretch-induced early remodeling stage was experimentally simulated by cyclic stretching at 15% for 48 hours in regular medium2, 3, whereas 10% stretch (with all other conditions remaining the same) represented the physiological counterpart. It was previously found that cyclic stretching at 15% for 48 hours in regular medium induced significant changes in the expression levels of key extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling proteins (such as MMP2, Cathepsin S and Cathepsin K) in PAV leaflets compared to 10% stretch2.

On the other hand, stretch-induced late calcification stage was experimentally simulated by cyclic stretching at 15% for one week in osteogenic medium (regular medium supplemented with 3.8 mM NaH2PO4.H2O, 1 mM β-Glycerophosphate, 10 µM Dexamethasone and 1 ng/mL TGF-β1)3, whereas 10% stretch (with all other conditions remaining the same) again represented the physiological counterpart. When PAV leaflets were cyclically stretched at 15% for one week in osteogenic medium, it was found that the degree of calcification (as quantified by Calcium Arsenazo assay) was at least two-fold higher than the one at 10% stretch [Supplemental Figure 2 (a)]. Similar qualitative results were obtained from Alizarin Red and Von Kossa staining [Supplemental Figure 2 (b)]. Balachandran et al.3 observed similar increase in PAV calcification under 15% stretch with osteogenic medium over a culture duration of two weeks.

miR-214 Overexpression in PAV Leaflets

PAV leaflets were transfected with either negative control mimic (QIAGEN) or miR-214 mimic (QIAGEN) in static culture for 48 hours and under 15% stretch for 72 hours. It should be noted here that for the 1-week long 15% stretch and 2-week long static miR214 overexpression experiments, the mimics were added only at Day 0 and (Day 0 and Day 7), respectively. In all transfection experiments, osteogenic medium was used to promote a calcification environment.

RNA Isolation and Real-time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated using a RNA isolation kit (ZYMO RESEARCH). cDNA was synthesized using a Reverse Transcription kit (QIAGEN). RT-qPCR was carried out in triplicates using a 96-well Real-Time PCR system. U6 and 18S were used as the housekeeping genes for miRNA and mRNA RT-qPCR, respectively. The primer assays for U6 and miR-214 were directly obtained from QIAGEN, whereas the forward and reverse primers for ATF4, CHOP and BCL2L1 mRNAs were custom designed [Table 1]. The relative expression levels of miR-214 and mRNAs were calculated using the ΔCT method52.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for 18S, ATF4, CHOP and BCL2L1

| mRNA | Forward Primer (5’→3’) | Reverse Primer (5’→3’) |

|---|---|---|

| 18S | AGGAATTGACGGAAGGGCACCA | GTGCAGCCCCGGACATCTAAG |

| ATF4 | AGTCCTTTTCTGCGAGTGGG | GAGAAGCGCCATGGCCTAAG |

| CHOP | CCCTGGAAATGAGGAGGAGTC | TGACTGGAATCAGGCGAGTG |

| BCL2L1 | TGACCACCTAGAGCCTTGGA | CGTCAGGAACCATCGGTTGA |

Assessment of PAV Calcification

PAV calcification was assessed by Calcium Arsenazo assay, Alizarin Red and Von Kossa stains3.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean. During statistical analysis, the first step was to discard outliers from each independent group of data. Outliers were detected based on the interquartile range. When comparing two independent data sets, independent samples t-test was used if both data sets were normally distributed. In case where either one or both data sets were not normally distributed, non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare these two groups. A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical tests were carried out in the IBM SPSS Statistics software. In addition to assessing statistical significance, effect size (Hedges’ g-value) was calculated for each case of comparison26. Small, medium and large effect sizes were represented by Hedges’ g-values of 0.2, 0.5 and 0.8, respectively.

Results

miR-214 Expression During Stretch-Induced Early Remodeling of PAV Leaflets

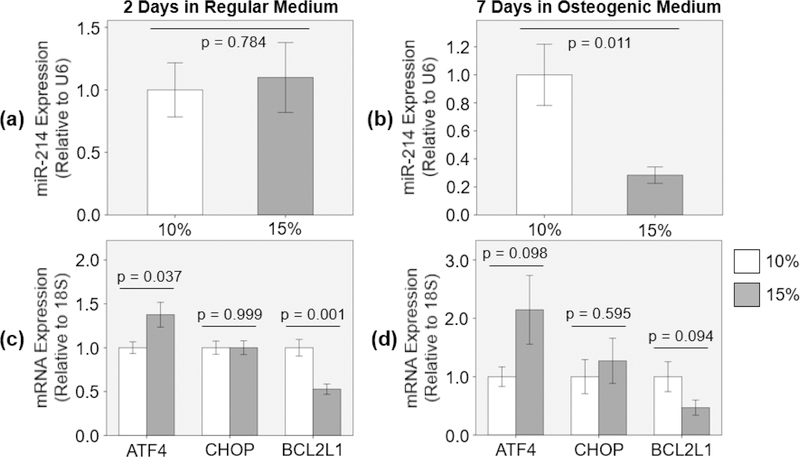

When PAV leaflets were cyclically stretched at 15% for 48 hours in regular medium, there was no significant change in miR-214 expression (9.9% increase with Hedges’ g- value of 0.14) compared to 10% stretch [Figure 1 (a)].

Figure 1:

(a) miR-214 [n = 8] and (c) ATF4, CHOP and BCL2L1 mRNA [n = 7 – 8] expression during the early remodeling stage, and (b) miR-214 [n = 9 – 10] and (d) ATF4, CHOP and BCL2L1 mRNA [n = 7 – 8] expression during the late calcification stage of stretch-induced PAV disease.

ATF4, CHOP and BCL2L1 mRNA Expression During Stretch-Induced Early Remodeling of PAV Leaflets

When PAV leaflets were cyclically stretched at 15% for 48 hours in regular medium,ATF4 mRNA expression was significantly upregulated (37.6% increase with Hedges’ g-value of 1.19) and BCL2L1 mRNA expression was significantly downregulated (47.3% decrease with Hedges’ g-value of 2.25) compared to the ones at 10% stretch [Figure 1 (c)]. However, the mRNA expression of CHOP remained the same under both stretch conditions (0.0% change with Hedges’ g-value of 0.000356) [Figure 1 (c)].

miR-214 Expression During Stretch-Induced Late Calcification of PAV Leaflets

When PAV leaflets were cyclically stretched at 15% for 1 week in osteogenic medium, miR-214 expression was significantly downregulated (71.6% decrease with Hedges’ g- value of 1.52) compared to 10% stretch [Figure 1 (b)]. Similar downregulation of miR-214 expression was also observed in calcified human AVs compared to healthy control13, 56, 65.

ATF4, CHOP and BCL2L1 mRNA Expression During Stretch-Induced Late Calcification of PAV Leaflets

When PAV leaflets were cyclically stretched at 15% for 1 week in osteogenic medium, there was considerable upregulation of ATF4 mRNA expression (114.5% increase with Hedges’ g-value of 0.91) and downregulation of BCL2L1 mRNA expression (53.1% decrease with Hedges’ g-value of 0.91) compared to the ones at 10% stretch [Figure 1 (d)]. These trends were similar to the ones observed for the early remodeling stage of stretch-induced aortic valve (AV) disease [Figure 1 (c)]. Additionally, there was slight increase in CHOP mRNA expression (27.1% increase with Hedges’ g-value of 0.28) at 15% stretch compared to 10% [Figure 1 (d)]. Interestingly, calcified human AVs have been shown to express increased levels of ATF4 and CHOP compared to healthy control8, 63.

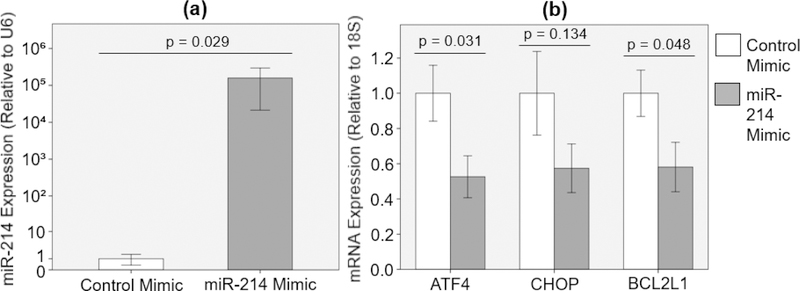

Effect of miR-214 Overexpression on ATF4, CHOP and BCL2L1 mRNA Expression in PAV Leaflets

When PAV leaflets were transfected with miR-214 mimic (50 nM) in static culture with osteogenic medium for 48 hours, miR-214 expression was significantly upregulated (15868121.8% increase with Hedges’ g-value of 0.82) compared to the case with control mimic (50 nM) [Figure 2 (a)]. Consequently, miR-214 overexpression resulted in significant downregulation of ATF4 and BCL2L1 mRNA expression (47.4% and 41.9% decrease with Hedges’ g-values of 1.19 and 1.12, respectively) compared to the control mimic case [Figure 2 (b)]. Additionally, there was considerable downregulation of CHOP mRNA expression (42.6% decrease with Hedges’ g-value of 0.83) with miR-214 mimic compared to the control mimic case [Figure 2 (b)].

Figure 2:

(a) miR-214 overexpression [n = 4] and (b) effect of miR-214 overexpression on ATF4, CHOP and BCL2L1 mRNA expression [n = 7 – 8] after 48-hour static PAV culture in osteogenic medium.

Effect of miR-214 Overexpression on PAV Calcification

When PAV leaflets were transfected with miR-214 mimic (50 nM) in static culture with osteogenic medium for 2 weeks and under 15% stretch with osteogenic medium for 1 week, miR-214 expression was significantly upregulated (19306.3% increase with Hedges’ g-value of 1.47 and 771.0% increase with Hedges’ g-value of 3.45, respectively) compared to the case with control mimic (50 nM) [Figures 3 (a) and 6 (a)]. Consequently, miR-214 overexpression resulted in significant reduction of PAV calcification (37.4% decrease with Hedges’ g-value of 1.14 in static culture and 20.6% decrease with Hedges’ g-value of 0.98 under 15% stretch) compared to the control mimic case, as determined by Calcium Arsenazo assay [Figures 3 (b) and 6 (b)]. Alizarin Red [Figure 4 (a) and (b)] and Von Kossa [Figure 5 (a) and (b)] staining showed similar reduction in PAV calcification (59.9% and 28.2% decrease with Hedges’ g- values of 1.39 and 1.81, respectively) upon transfection with miR-214 mimic.

Figure 3:

(a) miR-214 overexpression [n = 7 – 8] and (b) effect of miR-214 overexpression on PAV calcification [n = 7 – 8] as determined by Calcium Arsenazo assay after 2-week static culture in osteogenic medium.

Figure 6:

(a) miR-214 overexpression [n = 6 – 7] and (b) effect of miR-214 overexpression on PAV calcification [n = 8] as determined by Calcium Arsenazo assay after 1-week 15% stretch in osteogenic medium.

Figure 4:

(a) Representative Alizarin Red staining images (top: lower magnification, bottom: higher magnification) and (b) quantification of whole Alizarin Red stained PAV sections after 2-week static culture in osteogenic medium [n = 6; arrows indicate calcification].

Figure 5:

(a) Representative Von Kossa staining images (top: lower magnification, bottom: higher magnification) and (b) quantification of whole Von Kossa stained PAV sections after 2-week static culture in osteogenic medium [n = 4 – 6; arrows indicate calcification].

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the role of miR-214 in stretch-induced calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD), especially focusing on the ATF4/CHOP/BCL2L1 pathway. We found that elevated cyclic stretch (15%) downregulates miR-214 expression in PAVs during the late calcification stage of stretch-induced aortic valve (AV) disease. We also found that ATF4 and BCL2L1 expression was upregulated and downregulated, respectively, by 15% stretch during both early remodeling and late calcification stages of stretch- induced AV disease. When miR-214 was overexpressed in PAVs under static culture with osteogenic medium for 48 hours, there was significant reduction in ATF4 and BCL2L1 expression. Additionally, miR-214 overexpression resulted in significant reduction of PAV calcification after 2 weeks. Similar regulation of ATF4 expression by miR-214 was reported for chondrogenesis49 and osteogenesis34, 64, 72. In addition to that, inhibition of ATF4 expression by siRNA was found to downregulate the expression of osteogenic markers in valvular interstitial cells (VICs)8. However, to the best of our knowledge, the stretch-sensitive nature of this miR-214/ATF4 interaction has not been reported for AV, especially in relation to AV calcification.

It was intriguing to observe no significant change in miR-214 expression during the early remodeling stage of stretch-induced AV disease. This can be explained by the effect of TWIST1 on miR-214 expression. TWIST1, a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor, is a positive regulator of miR-214 expression33. TWIST1 expression was previously shown to be induced by TIMP114. Interestingly, Balachandran et al.2 showed that there was no significant change in TIMP1 expression between 10% and 15% stretch after 48 hours of cyclic stretching in regular medium. Consequently, similar TIMP1 expression under both stretch levels implies that there may be no significant change in TWIST1 expression, explaining the observed non-significant difference in miR-214 expression during the early remodeling stage of stretch-induced AV disease. On the other hand, TWIST1 expression was found to be significantly downregulated in calcified human AVs compared to healthy AVs75. In addition to that, TWIST1 has an inhibiting effect on osteogenesis6, 38 and cyclic stretching at 15% for a longer duration (>> 48 hours) may downregulate its expression via Scleraxis (SCX), another bHLH transcription factor5, 39, 50. This may explain the significantly downregulated miR-214 expression during the late calcification stage of stretch-induced AV disease.

It has been well established that ATF4 is a pro-osteogenic transcription factor8, 36. Valentine et al.60 showed that exposure of mouse type II alveolar epithelial cells (ATII) to 15% stretch resulted in significant increase of ATF4 expression compared to static control. Yang et al.71 reported that 10% stretch significantly upregulated ATF4 expression in human periodontal ligament cells (hPDLCs) compared to static control. Since elevated cyclic stretch (15%) induces higher AV calcification compared to the physiological level (10%)3, the observed upregulation of ATF4 expression (15% vs. 10% stretch) in PAV leaflets makes sense from both biomechanical and functional point of view. ATF4 can upregulate the expression of MMP2 and MMP9 in cancer cells17, 76. Similar upregulation of MMP2 and MMP9 expression was observed in PAV leaflets under pathological cyclic stretch (15%) compared to the physiological level (10%)2.

It was surprising to observe that CHOP expression remained effectively the same during the early remodeling and late calcification stages of stretch-induced AV disease. Jia et al.30 reported that 18% stretch significantly upregulated CHOP expression in mouse aortic smooth muscle cells (SMCs) compared to static control. However, Cheng et al.12 showed that 20% stretch induced a brief (during the culture period from 12 to 18 hours) increase in CHOP expression of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) compared to 10% stretch, which was attenuated afterwards (culture period > 18 hours). Therefore, it is possible that pathological cyclic stretch (15%) induces similar transient increase of CHOP expression in PAV leaflets compared to the physiological level (10%), which is later attenuated by some adaptive response of the tissue itself. Tribbles Homolog 3 (TRB3) is one of the transcriptional targets of ATF4 that is upregulated when there is an increase in ATF4 expression40. It should be noted here that CHOP is another transcriptional target of ATF416. Interestingly, increased TRB3 expression works in a negative feedback loop to inhibit the transcriptional induction of CHOP31. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that the insensitivity of CHOP expression to pathological cyclic stretch (15%) during the early remodeling and late calcification stages of stretch- induced AV disease may be caused by TRB3-mediated inhibition of its transiently increased expression at 15% stretch compared to 10%. On the other hand, the observed non-significant effect of miR-214 overexpression on CHOP mRNA expression in PAV leaflets makes sense since miR-214 has not been predicted to target CHOP at the 3’UTR region18.

BCL2L1 is mainly a pro-survival gene due to its predominant anti-apoptotic isoform, BCL-XL54. Contrary to our findings, 15% stretch was found to upregulate BCL-XL expression in aortic smooth muscle cells (SMCs) compared to both static condition and 5% stretch37. One of the positive regulators of BCL2L1 is B-Cell Lymphoma/Leukemia 11B (BCL11B)23, 32. Interestingly, BCL11B expression was found to be downregulated with increased arterial stiffness61, 67. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that decrease in BCL2L1 expression during the early remodeling and late calcification stages of stretch- induced AV disease may be mediated by downregulation of BCL11B expression. Surprisingly, both BCL11B and BCL2L1 expression was found to be upregulated in calcified human AVs compared to healthy control7, 35. This indicates that disturbed flow may have a more pronounced effect in upregulating BCL2L1 expression compared to the downregulation induced by elevated mechanical stretch57. In addition to that, miR-214 overexpression resulted in significant reduction of BCL2L1 expression in PAV leaflets, as observed in our study. This confirms the already known anti-proliferative effect of miR-214, especially in cancer cells11.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge NIH grant R01HL119798 for funding support. We would also like to thank Holifield Farms (Covington, GA) for graciously providing the porcine hearts and Jaeyeon Lee for her help with imaging and quantification.

References

- 1.Arjunon S, Rathan S, Jo H, and Yoganathan AP. Aortic valve: mechanical environment and mechanobiology. Ann Biomed Eng, 41(7), 1331–1346, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balachandran K, Sucosky P, Jo H, and Yoganathan AP. Elevated cyclic stretch alters matrix remodeling in aortic valve cusps: implications for degenerative aortic valve disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 296(3), H756–H764, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balachandran K, Sucosky P, Jo H, and Yoganathan AP. Elevated cyclic stretch induces aortic valve calcification in a bone morphogenic protein-dependent manner. Am J Pathol, 177(1), 49–57, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balachandran K, Sucosky P, and Yoganathan AP. Hemodynamics and mechanobiology of aortic valve inflammation and calcification. Int J Inflam, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Bagchi RA, Roche P, Aroutiounova N, Espira L, Abrenica B, Schweitzer R, and Czubryt MP. The transcription factor scleraxis is a critical regulator of cardiac fibroblast phenotype. BMC Biol, 14(1), 21, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bialek P, Kern B, Yang X, Schrock M, Sosic D, Hong N, Wu H, Yu K, Ornitz DM, Olson EN, Justice MJ, and Karsenty GA. Twist code determines the onset of osteoblast differentiation. Dev Cell, 6(3), 423–435, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bossé Y, Miqdad A, Fournier D, Pépin A, Pibarot P, and Mathieu P. Refining molecular pathways leading to calcific aortic valve stenosis by studying gene expression profile of normal and calcified stenotic human aortic valves. Circ Genom Precis Med, 2(5), 489–498, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai Z, Li F, Gong W, Liu W, Duan Q, Chen C, Ni L, Xia Y, Cianflone K, Dong N, and Wang DW. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Participates in Aortic Valve Calcification in Hypercholesterolemic Animals. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 33(10), 2345–2354, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakravarty T, Søndergaard L, Friedman J, et al. Subclinical leaflet thrombosis in surgical and transcatheter bioprosthetic aortic valves: an observational study. Lancet, 389(10087), 2383–2392, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen JH, and Simmons CA. Cell-matrix interactions in the pathobiology of calcific aortic valve disease: critical roles for matricellular, matricrine, and matrix mechanics cues. Circ Res, 108(12), 1510–1524, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen DL, Wang ZQ, Zeng ZL, et al. Identification of microRNA‐214 as a negative regulator of colorectal cancer liver metastasis by way of regulation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 expression. Hepatology, 60(2), 598–609, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng WP, Hung HF, Wang BW, and Shyu KG. The molecular regulation of GADD153 in apoptosis of cultured vascular smooth muscle cells by cyclic mechanical stretch. Cardiovasc Res, 77(3), 551–559, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coffey S, Williams MJ, Phillips LV, Galvin IF, Bunton RW, and Jones GT.Integrated microRNA and messenger RNA analysis in aortic stenosis. Sci Rep, 6,36904, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Angelo RC, Liu XW, Najy AJ, Jung YS, Won J, Chai KX, Fridman R, and Kim HRC. TIMP-1 via TWIST1 induces EMT phenotypes in human breast epithelial cells. Mol Cancer Res, molcanres-0105, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Desvignes T, Contreras A, and Postlethwait JH. Evolution of the miR199–214 cluster and vertebrate skeletal development. RNA Biol, 11(4), 281–294, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dey S, Baird TD, Zhou D, Palam LR, Spandau DF, and Wek RC. Both transcriptional regulation and translational control of ATF4 is central to the Integrated Stress Response. J Biol Chem, jbc-M110, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Dey S, Sayers CM, Verginadis II, Lehman SL, Cheng Y, Cerniglia GJ, Tuttle SW, Feldman MD, Zhang PJL, Fuchs SY, Diehl JA, and Koumenis C.ATF4-dependent induction of heme oxygenase 1 prevents anoikis and promotes metastasis. J Clin Invest, 125(7), 2592–2608, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dweep H, & Gretz N. miRWalk2.0: a comprehensive atlas of microRNA-target interactions. Nat Methods, 12(8), 697, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garg AD, Kaczmarek A, Krysko O, Vandenabeele P, Krysko DV, and Agostinis P. ER stress-induced inflammation: does it aid or impede disease progression?. Trends Mol Med, 18(10), 589–598, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaudette BT, Iwakoshi NN, and Boise LH. Bcl-xL protein protects from CHOP- dependent apoptosis during plasma cell differentiation. J Biol Chem, jbc-M114, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Généreux P, Cohen DJ, Williams MR, Mack M, Kodali SK, Svensson LG,Kirtane AJ, Xu K, McAndrew TC, Makkar R, Smith CR, and Leon MB.Bleeding complications after surgical aortic valve replacement compared with transcatheter aortic valve replacement: insights from the PARTNER I Trial (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve). J Am Coll Cardiol, 63(11), 1100–1109, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gould ST, Srigunapalan S, Simmons CA, and Anseth KS. Hemodynamic and cellular response feedback in calcific aortic valve disease. Circ Res, 113(2), 186–197, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grabarczyk P, Przybylski GK, Depke M, Völker U, Bahr J, Assmus K, Bröker BM, Walther R, and Schmidt CA. Inhibition of BCL11B expression leads to apoptosis of malignant but not normal mature T cells. Oncogene, 26(26), 3797, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ha M, and Kim VN. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 15(8), 509, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heath JM, Esmerats JF, Khambouneheuang L, Kumar S, Simmons R, and Jo H. Mechanosensitive microRNA-181b regulates aortic valve endothelial matrix degradation by targeting TIMP3. Cardiovasc Eng Technol, 9(2), 141–150, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hedges LV Distribution theory for Glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Educ Behav Stat, 6(2), 107–128, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hetz C The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 13(2), 89, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holliday CJ, Ankeny RF, Jo H, and Nerem RM. Discovery of shear-and side- specific mRNAs and miRNAs in human aortic valvular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 301(3), H856–H867, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutcheson JD, Aikawa E, and Merryman WD. Potential drug targets for calcific aortic valve disease. Nat Rev Cardiol, 11(4), 218, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia LX, Zhang WM, Zhang HJ, Li TT, Wang YL, Qin YW, Gu H, and Du J. Mechanical stretch‐induced endoplasmic reticulum stress, apoptosis and inflammation contribute to thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection. J Pathol, 236(3), 373–383, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jousse C, Deval C, Maurin AC, Parry L, Chérasse Y, Chaveroux C, Lefloch R,Lenormand P, Bruhat A, and Fafournoux P. TRB3 inhibits the transcriptional activation of stress-regulated genes by a negative feedback on the ATF4 pathway. J Biol Chem, 282(21), 15851–15861, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamimura K, Mishima Y, Obata M, Endo T, Aoyagi Y, and Kominami R. Lack of Bcl11b tumor suppressor results in vulnerability to DNA replication stress and damages. Oncogene, 26(40), 5840, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee YB, Bantounas I, Lee DY, Phylactou L, Caldwell MA, and Uney JB.Twist-1 regulates the miR-199a/214 cluster during development. Nucleic Acids Res,37(1), 123–128, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li D, Liu J, Guo B, et al. Osteoclast-derived exosomal miR-214–3p inhibits osteoblastic bone formation. Nat Commun, 7, 10872, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li F, Song R, Ao L, Reece TB, Cleveland JC Jr, Dong N, Fullerton D, and Meng X. ADAMTS5 deficiency in calcified aortic valves is associated with elevated pro-osteogenic activity in valvular interstitial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 37(7), 1339–1351, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masuda M, Miyazaki-Anzai S, Keenan AL, Shiozaki Y, Okamura K, Chick WS, Williams K, Zhao X, Rahman SM, Tintut Y, Adams CM, and Miyazaki M. Activating transcription factor-4 promotes mineralization in vascular smooth muscle cells. JCI Insight, 1(18), 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayr M, Hu Y, Hainaut P, and Xu Q. Mechanical stress-induced DNA damage and rac-p38MAPK signal pathways mediate p53-dependent apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. FASEB J, 16(11), 1423–1425, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miraoui H, Severe N, Vaudin P, Pagès JC, and Marie PJ. Molecular silencing of Twist1 enhances osteogenic differentiation of murine mesenchymal stem cells: implication of FGFR2 signaling. J Cell Biochem, 110(5), 1147–1154, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morita Y, Watanabe S, Ju Y, and Xu B. Determination of optimal cyclic uniaxial stretches for stem cell-to-tenocyte differentiation under a wide range of mechanical stretch conditions by evaluating gene expression and protein synthesis levels. Acta Bioeng Biomech, 15(3), 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohoka N, Yoshii S, Hattori T, Onozaki K, and Hayashi H. TRB3, a novel ER stress‐inducible gene, is induced via ATF4-CHOP pathway and is involved in cell death. EMBO J, 24(6), 1243–1255, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osnabrugge RL, Mylotte D, Head SJ, Van Mieghem NM, Nkomo VT, LeReun CM, Ad JJC Bogers, N. Piazza, and A. P. Kappetein. Aortic stenosis in the elderly: disease prevalence and number of candidates for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a meta-analysis and modeling study. J Am Coll Cardiol, 62(11), 1002–1012, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel V, Carrion K, Hollands A, Hinton A, Gallegos T, Dyo J, Sasik R, Leire E,Hardiman G, Mohamed SA, Nigam S, King CC, Nizet V, and Nigam S. The stretch responsive microRNA miR-148a-3p is a novel repressor of IKBKB, NF-κB signaling, and inflammatory gene expression in human aortic valve cells. FASEB J, 29(5), 1859–1868, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Puthalakath H, O’Reilly LA, Gunn P, Lee L, Kelly PN, Huntington ND, Hughes PD, Michalak EM, McKimm-Breschkin J, Motoyama N, Gotoh T, Akira S, Bouillet P, and Strasser A. ER stress triggers apoptosis by activating BH3-only protein Bim. Cell, 129(7), 1337–1349, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajamannan NM, Evans FJ, Aikawa E, Grande-Allen KJ, Demer LL, Heistad DD, Simmons CA, Masters KS, Mathieu P, O’Brien KD, Schoen FJ, Towler DA, Yoganathan AP, and Otto CM. Calcific Aortic Valve Disease: Not Simply a Degenerative Process: A Review and Agenda for Research from the National Heart and Lung and Blood Institute Aortic Stenosis Working Group Executive Summary: Calcific Aortic Valve Disease-2011 Update. Circulation, 124(16), 1783–1791, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajamannan NM, Subramaniam M, Rickard D, Stock SR, Donovan J, Springett M, Orszulak T, Fullerton DA, Tajik AJ, Bonow RO, and Spelsberg T. Human aortic valve calcification is associated with an osteoblast phenotype. Circulation, 107(17), 2181–2184, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rathan S Aortic Valve Mechanobiology – Role of Altered Hemodynamics in Mediating Aortic Valve Inflammation and Calcification (Doctoral dissertation, Georgia Institute of Technology), 2016.

- 47.Rathan S, Ankeny CJ, Arjunon S, Ferdous Z, Kumar S, Esmerats JF, Heath JM, Nerem RM, and Jo H. Identification of side-and shear-dependent microRNAs regulating porcine aortic valve pathogenesis. Sci Rep, 6, 25397, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rathan S, Yap CH, Morris E, Arjunon S, Jo H, and Yoganathan AP. Low and Unsteady Shear Stresses Upregulate Calcification Response of the Aortic Valve Leaflets. In ASME 2011 Summer Bioengineering Conference (pp. 245–246), June 2011.

- 49.Roberto VP, Gavaia P, Nunes MJ, Rodrigues E, Cancela ML, and Tiago DM. Evidences for a New Role of miR-214 in Chondrogenesis. Sci Rep, 8(1), 3704, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roche PL, Nagalingam RS, Bagchi RA, Aroutiounova N, Belisle BM, Wigle JT, and Czubryt MP. Role of scleraxis in mechanical stretch-mediated regulation of cardiac myofibroblast phenotype. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 311(2), C297–C307, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rupaimoole R, and Slack FJ. MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 16(3), 203, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmittgen TD, and Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc, 3(6), 1101, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shi K, Lu J, Zhao Y, Wang L, Li J, Qi B, Li H, and Ma C. MicroRNA-214 suppresses osteogenic differentiation of C2C12 myoblast cells by targeting Osterix. Bone, 55(2), 487–494, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shimizu S, Eguchi Y, Kosaka H, Kamiike W, Matsuda H, and Tsujimoto Y. Prevention of hypoxia-induced cell death by Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL. Nature, 374(6525), 811–813, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic- valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med, 364(23), 2187–2198, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song R, Fullerton DA, Ao L, Zhao KS, Reece TB, Cleveland JC, and Meng X. Altered MicroRNA Expression Is Responsible for the Pro‐Osteogenic Phenotype of Interstitial Cells in Calcified Human Aortic Valves. J Am Heart Assoc, 6(4), e005364, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takabe W, Alberts-Grill N, and Jo H. Disturbed flow: p53 SUMOylation in the turnover of endothelial cells. J Cell Biol, 193(5), 805–807, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thubrikar M The aortic valve Abingdon, UK, Routledge, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ueda T, Volinia S, Okumura H, et al. Relation between microRNA expression and progression and prognosis of gastric cancer: a microRNA expression analysis. Lancet Oncol, 11(2), 136–146, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Valentine MS, Herbert JA, Link PA, Gninzeko FJK, Schneck MB, Shankar K, Nkwocha J, Reynolds AM, and Heise RL. The Influence of Aging and Mechanical Stretch in Alveolar Epithelium ER Stress and Inflammation. bioRxivorg, 157677, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Valisno JA, Elavalakanar P, Nicholson C, Singh K, Avram D, Cohen RA, Mitchell GF, Morgan KG, and Seta F. Bcl11b is a Newly Identified Regulator of Vascular Smooth Muscle Phenotype and Arterial Stiffness. bioRxivorg, 193110, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Rooij E, and Olson EN. MicroRNA therapeutics for cardiovascular disease: opportunities and obstacles. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 11(11), 860, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang B, Cai Z, Liu B, Liu Z, Zhou X, Dong N, and Li F. RAGE deficiency alleviates aortic valve calcification in ApoE−/− mice via the inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis, 1863(3), 781–792, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang X, Guo B, Li Q, et al. (2013). miR-214 targets ATF4 to inhibit bone formation. Nat Med, 19(1), 93, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang H, Shi J, Li B, Zhou Q, Kong X, and Bei Y. MicroRNA expression signature in human calcific aortic valve disease. Biomed Res Int, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Watanabe T, Sato T, Amano T, Kawamura Y, Kawamura N, Kawaguchi H, Yamashita N, Kurihara H, and Nakaoka T. Dnm3os, a non‐coding RNA, is required for normal growth and skeletal development in mice. Dev Dyn, 237(12), 3738–3748, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu J, Thabet SR, Kirabo A, Trott DW, Saleh MA, Xiao L, Madhur MS, Chen W, and Harrison DG. Inflammation and mechanical stretch promote aortic stiffening in hypertension through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Circ Res, 114(4), 616–625, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xiao G, Jiang D, Ge C, Zhao Z, Lai Y, Boules H, Phimphilai M, Yang X, Karsenty G, and Franceschi RT. Cooperative interactions between activating transcription factor 4 and Runx2/Cbfa1 stimulate osteoblast-specific osteocalcin gene expression. J Biol Chem, 280(35), 30689–30696, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang L, Ge D, Cao X, Ge Y, Chen H, Wang W, and Zhang H. MiR-214 attenuates osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells via targeting FGFR1. Cell Physiol Biochem, 38(2), 809–820, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang H, Kong W, He L, Zhao JJ, O’Donnell JD, Wang J, Wenham RM, Coppola D, Kruk PA, Nicosia SV, and Cheng JQ. MicroRNA expression profiling in human ovarian cancer: miR-214 induces cell survival and cisplatin resistance by targeting PTEN. Cancer Res, 68(2), 425–433, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang SY, Wei FL, Hu LH, and Wang CL. PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 pathway mediated by endoplasmic reticulum stress response is involved in osteodifferentiation of human periodontal ligament cells under cyclic mechanical force. Cell Signal, 28(8), 880–886, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yao S, Zhao W, Ou Q, Liang L, Lin X, and Wang Y. MicroRNA-214 suppresses osteogenic differentiation of human periodontal ligament stem cells by targeting ATF4. Stem Cells Int, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Yap CH, Kim HS, Balachandran K, Weiler M, Haj-Ali R, and Yoganathan AP. Dynamic deformation characteristics of porcine aortic valve leaflet under normal and hypertensive conditions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 298(2), H395–H405, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yu S, Zhu K, Lai Y, Zhao Z, Fan J, Im HJ, Chen D, and Xiao G. Atf4 promotes β-catenin expression and osteoblastic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Biol Sci, 9(3), 256, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang XW, Zhang BY, Wang SW, Gong DJ, Han L, Xu ZY, and Liu XH.Twist-related protein 1 negatively regulated osteoblastic transdifferentiation of human aortic valve interstitial cells by directly inhibiting runt-related transcription factor 2. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 148(4), 1700–1708, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhu H, Chen X, Chen B, Chen B, Song W, Sun D, and Zhao Y. Activating transcription factor 4 promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma invasion and metastasis in mice and is associated with poor prognosis in human patients. PLoS One, 9(7), e103882, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.