Abstract

A consolidated overview of evidence for the effectiveness and safety/tolerability of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) treatment over the long term is currently lacking. We identified and assessed published evidence for the long-term (≥6 months) pharmacological management of HE with lactulose and/or rifaximin. A literature search was conducted in PubMed (cutoff date 05 March 2018) using the search terms ‘hepatic encephalopathy+rifaximin’ and ‘hepatic encephalopathy+lactulose’. All articles containing primary clinical data were manually assessed to identify studies in which long-term (≥6 months) effectiveness and/or safety/tolerability end points were reported for lactulose and/or rifaximin. Long-term effectiveness outcomes were reported in eight articles for treatment with lactulose alone and 19 articles for treatment with rifaximin, alone or in combination with lactulose. Long-term safety/tolerability outcomes were reported in six articles for treatment with lactulose alone and nine articles for treatment with rifaximin, alone or in combination with lactulose. These studies showed that lactulose is effective for the prevention of overt HE recurrence over the long term and that the addition of rifaximin to lactulose significantly reduces the risk of overt HE recurrence and HE-related hospitalization, compared with lactulose therapy alone, without compromising tolerability. Current evidence therefore supports recommendations for the use of lactulose therapy for the prevention of overt HE recurrence over the long term, and for the additional benefit of adding rifaximin to lactulose therapy. Addition of rifaximin to standard lactulose therapy may result in substantial reductions in healthcare resource utilization over the long term, by reducing overt HE recurrence and associated rehospitalization.

Keywords: antibiotics, cirrhosis, hepatic encephalopathy, lactulose, nonabsorbable disaccharides, rifaximin, secondary prophylaxis, systematic review

Introduction

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a brain dysfunction caused by liver insufficiency and/or portosystemic shunting, which manifests as a wide spectrum of neurological or psychiatric abnormalities, ranging from subclinical alterations to coma 1. The primary pathophysiological mechanism underlying HE is thought to involve elevated blood levels of gut-derived neurotoxins – in particular, ammonia – entering the brain owing to the inability of the cirrhotic liver to remove them from the blood circulation 2–4. HE increases the risk of mortality 5 and is one of the most debilitating complications of liver disease 1. Overt HE (OHE) occurs in 30–40% of patients with cirrhosis at some time during their clinical course, with minimal HE (MHE) reported to potentially affect 20–80% of patients with cirrhosis 1.

HE has a substantial economic effect, not only owing to the direct costs of its management (particularly HE-related hospitalization) but also to the indirect costs arising from, for example, absence from work and loss of work productivity 1,6,7. HE negatively affects the lives of both patients and caregivers 1,8 and the socioeconomic implications of HE over the longer term may be very profound, decreasing work performance, increasing the risk of vehicle accidents and severely impairing quality of life 1. Currently available treatment options for HE include nonabsorbable disaccharides (e.g. lactulose), antibiotics (e.g. rifaximin-α 550 mg) and l-ornithine l-aspartate (LOLA) 1. Other potential therapies include branched-chain amino acids, probiotics, metabolic ammonia scavengers and glutaminase inhibitors 1.

Nonabsorbable disaccharides not only remove nitrogen-containing substances from the gastrointestinal tract via their laxative effects but are also metabolized by the colonic microbiota to produce short-chain organic acids 2. These acids are thought to inhibit the growth of ammonia-producing bacteria and to convert ammonia to nonabsorbable ammonium, thereby further decreasing the ammonia load 2. Adherence to lactulose may be affected by its adverse effects, which can include severe diarrhea, hypokalemia, hyponatremia, bloating, flatulence, nausea and vomiting 9,10.

The most commonly used antibiotic, rifaximin-α 550 mg, is a locally acting oral antibiotic that is minimally absorbed in the gut to reduce the effects of intestinal flora, including ammonia-producing species 11,12. Rifaximin-α 550 mg is indicated for the reduction in recurrence of episodes of OHE in patients aged ≥18 years 13. C. difficile-associated diarrhea has been reported with the use of nearly all antibacterial agents, including rifaximin-α 550 mg 13.

Current guidelines recommend that an episode of OHE (whether spontaneous or precipitated) should be actively treated, and that secondary prophylaxis should be initiated after an episode to prevent recurrence 1. Lactulose is recommended as the first choice for treatment of episodic HE, and for the prevention of recurrent episodes of HE after the initial episode 1. Rifaximin is recommended as an effective add-on to lactulose for the prevention of OHE recurrence after the second episode 1. Intravenous LOLA and oral branched-chain amino acids can be used as alternative or additional agents to treat patients who are not responsive to conventional therapy 1. Prophylactic therapy should be continued, unless precipitating factors (e.g. infections and variceal bleeding) have been well controlled or liver function or nutritional status improved 1. However, a consolidated overview of current evidence for the effectiveness and safety/tolerability of HE treatment in the long-term setting is currently lacking. The aims of this systematic review were therefore to identify and assess published evidence for the long-term (≥6 months) pharmacological management of HE and to discuss the implications of this evidence for everyday clinical practice.

Materials and methods

Literature searches were conducted in PubMed of titles and abstracts only, with language restricted to English and the date range unrestricted up to the cutoff date (5 March 2018), using the following search terms: ‘hepatic encephalopathy+rifaximin’ and ‘hepatic encephalopathy+lactulose’. The abstracts of all identified articles were manually assessed to identify primary clinical data-containing manuscripts (i.e. articles containing clinical trial, clinical practice study, observational, registry, health economic and/or survey data, including journal-published congress abstracts if indexed on PubMed). These were then assessed to identify studies in which long-term effectiveness and/or safety/tolerability end points were reported for lactulose and/or rifaximin. Long-term treatment was defined as at least 6 months. The results of studies were then tabulated for further evaluation.

Similar initial searches were additionally conducted using the search terms ‘hepatic encephalopathy+l-ornithine-l-aspartate, ‘hepatic encephalopathy+LOLA’ and ‘hepatic encephalopathy+ornithine aspartate’. However, as only one study was identified that reported long-term (≥6 months) outcomes 14, the subsequent review process was restricted to evidence for lactulose and rifaximin only.

Number needed to treat (NNT) analyses were carried out for studies reporting significant between-group differences in the rate of OHE recurrence following at least 6 months of secondary prophylaxis with lactulose and/or rifaximin. Studies investigating primary prophylaxis and different dosing regimens of rifaximin were excluded from the NNT analysis.

Results

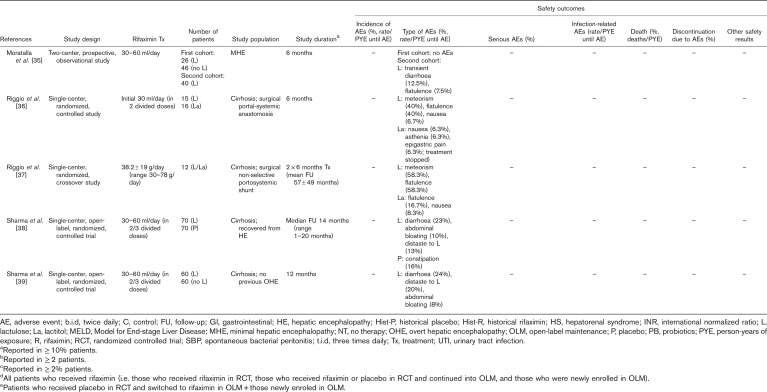

The search term ‘hepatic encephalopathy+rifaximin’ identified a total of 235 articles, of which 71 were assessed as containing primary clinical data (Fig. 1). The search term ‘hepatic encephalopathy+lactulose’ identified 355 articles, of which 130 contained primary clinical data (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Summary of numbers of journal articles indexed on PubMed, identified using the search terms ‘hepatic encephalopathy+lactulose’ and ‘hepatic encephalopathy+rifaximin’. Searches were conducted of titles and abstracts only, with language restricted to English and the date range unrestricted up to the cutoff date (5 March 2018). aArticles without an abstract; barticles containing primary clinical trial, clinical practice study, observational, registry, health economic, or survey data, including journal-published congress abstracts, if indexed on PubMed; c≥6 months; darticles relating to rifaximin alone or in combination with lactulose; earticles relating to lactulose alone.

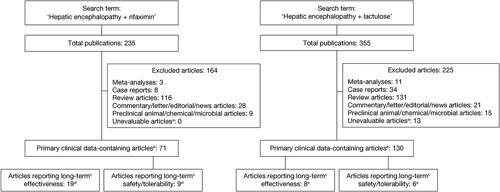

Effectiveness of long-term (>_6 months) treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with rifaximin and/or lactulose

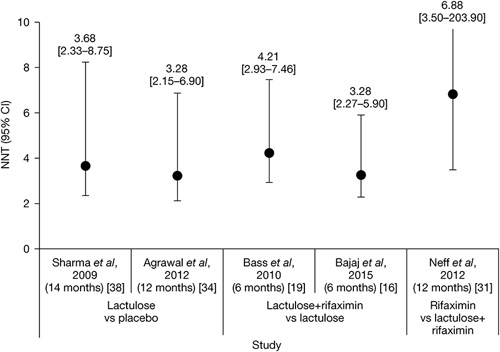

Manual assessment of the articles containing primary clinical data identified long-term effectiveness outcomes for treatment of HE, with eight articles reporting outcomes for treatment with lactulose alone and a further 19 articles reporting outcomes for treatment with rifaximin, alone or in combination with lactulose (Table 1). NNT analyses were carried out of studies reporting at least 6 months of secondary prophylaxis with lactulose versus no lactulose (n=1) 34, lactulose versus placebo (n=1) 38, rifaximin+lactulose versus placebo+lactulose (n=2) 16,19 and rifaximin monotherapy versus rifaximin+lactulose (n=1) 31 (Fig. 2). Details of studies including more than 100 patients are summarized in more detail later.

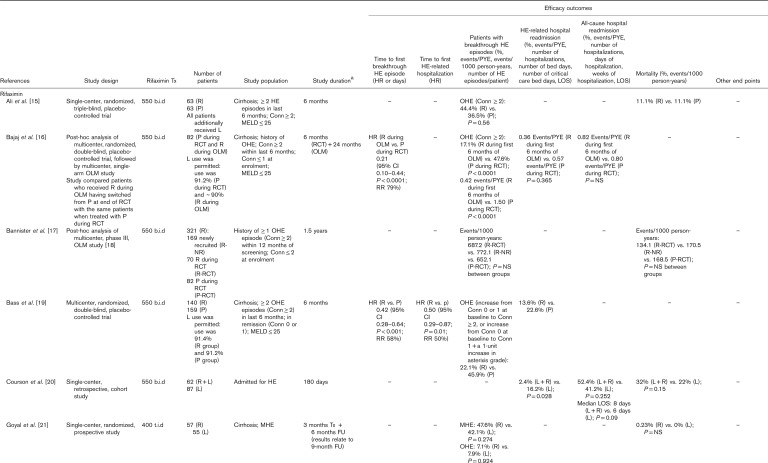

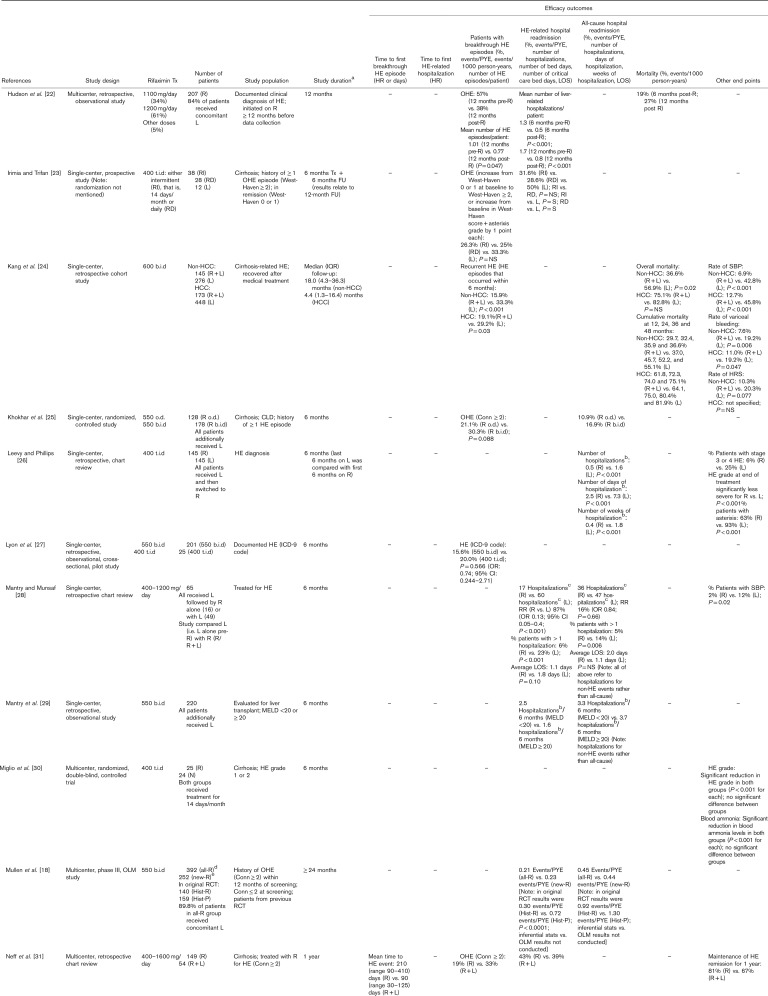

Table 1.

Articles reporting effectiveness outcomes over the long term (≥6 months) for patients treated with rifaximin and/or lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy. Articles reporting data for rifaximin and lactulose are presented in the rifaximin section; those reporting data for lactulose, but not rifaximin, are presented in the lactulose section.

Fig. 2.

NNTs with 95% CIs for lactulose versus no lactulose/placebo 34,38, rifaximin+lactulose versus placebo+lactulose 16,19, and rifaximin monotherapy versus rifaximin+lactulose 31. CI, confidence interval; NNT, number needed to treat.

Table 1.

(Continued)

Table 1.

(Continued)

Lactulose alone

In a single-center, retrospective, chart review of 137 patients who received lactulose for a mean duration of 27±6 months after their first HE event, it was found that 75% of the patients experienced HE recurrence after 9±1 months 10. The rate of HE-related hospital readmission was 73%, and the mortality rate was 34% 10. Thirty-nine (28.5%) patients had HE recurrence associated with lactulose nonadherence, mostly resulting from gastrointestinal adverse effects 10.

Several large single-center, open-label, randomized, controlled studies have assessed the long-term (≥6 months) effectiveness of lactulose therapy, compared with placebo, probiotics and/or no therapy. Compared with no treatment or placebo, the calculated NNT values [95% confidence intervals (CIs)] for lactulose as secondary prophylaxis for OHE recurrence were 3.28 (2.15–6.90) 34 and 3.68 (2.33–8.75) 38 (Fig. 2).

In a primary prophylaxis study, patients with cirrhosis but no previous history of OHE were randomized to receive lactulose therapy (n=60) or no lactulose therapy (n=60) for 12 months 39. Lactulose significantly reduced the rate of OHE occurrence versus no lactulose (11 vs. 28%; P=0.02) and reduced the median length of stay for HE-related hospitalization, although not significantly 39. In a secondary prophylaxis study, patients with cirrhosis who had recovered from OHE were randomized to receive lactulose (n=68), probiotics (n=64) or no therapy (n=65) for up to 12 months 34. The rate of OHE recurrence was 26.5% with lactulose, 34.4% with probiotics and 56.9% with no therapy (lactulose vs. probiotics, P=not significant; lactulose vs. no therapy, P=0.001; and probiotics vs. no therapy, P=0.02) 34. The mortality rate was 19.1, 17.2 and 24.6% for the lactulose, probiotics and no therapy groups, respectively (P=not significant between groups) 34. In a similar secondary prophylaxis study, patients were randomized to receive lactulose or placebo over a median follow-up duration of 14 months 38. Lactulose was significantly superior to placebo in reducing the rate of OHE recurrence (19.6 vs. 46.8%; P=0.001) but not in reducing the rate of hospitalization for non-HE events or mortality 38.

Rifaximin with or without lactulose

Most rifaximin studies assessed the additional benefit of rifaximin prophylaxis as an adjunct to lactulose therapy. Compared with placebo+lactulose, NNT values (95% CIs) for rifaximin+lactulose as secondary prophylaxis for OHE recurrence were calculated to be 3.28 (2.27–5.90) 16 and 4.21 (2.93–7.46) 19 (Fig. 2).

A phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial compared the effectiveness of rifaximin-α 550 mg twice daily versus placebo for the prevention of OHE recurrence over 6 months in 299 patients with cirrhosis who had experienced at least two OHE episodes in the previous 6 months but who were currently in remission 19. More than 90% of patients in both treatment arms additionally received lactulose therapy. The rate of OHE recurrence was 22.1% with rifaximin versus 45.9% with placebo 19. The hazard ratio for the time to a breakthrough OHE episode for rifaximin versus placebo was 0.42 (95% CI: 0.28–0.64; P<0.001), reflecting a relative risk reduction of 58% with rifaximin versus placebo 19. The rate of HE-related hospital readmission was 13.6% with rifaximin versus 22.6% with placebo, and the hazard ratio for time to first HE-related hospitalization for rifaximin versus placebo was 0.50 (95% CI: 0.29–0.87; P=0.01), representing a 50% relative reduction in risk 19. In a subanalysis of this trial (n=219), conducted primarily to assess health-related quality of life, the rate of OHE recurrence was 25.7% with rifaximin versus 50.0% with placebo, and HE remission was maintained for 6 months in 74.3% of patients treated with rifaximin versus 50.0% of those treated with placebo 32.

In a similarly designed single-center, randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 126 patients with cirrhosis who were admitted to hospital with an index OHE event, having experienced at least one other OHE event in the previous 6 months, were treated with rifaximin-α 550 mg or placebo for 6 months, in addition to lactulose therapy 15. In this trial, rate of HE recurrence was 44.4% with rifaximin versus 36.5% with placebo (P=not significant), and the mortality rate was 11.1% in both treatment groups 15.

When examining long-term use specifically, patients completing the trial by Bass and colleagues were eligible to enter a phase III, multicenter, open-label maintenance study, in which patients received open-label treatment with rifaximin-α 550 mg for 24 months 18. In total, 392 patients were treated with rifaximin (‘all-rifaximin’ group), including 252 patients who received de novo treatment (‘new-rifaximin’ group). As in the initial trial, ~90% of patients were additionally treated with lactulose. The rates of HE-related hospitalization were 0.21 and 0.23 events/person-year of exposure (PYE) for the all-rifaximin and new-rifaximin groups, respectively 18. In the original trial, the corresponding values were 0.30 events/PYE for rifaximin versus 0.72 events/PYE for placebo (P<0.0001) 18. A post-hoc analysis of this study was conducted for 321 patients who had been treated for mean duration of 1.5 years 17. Data were compared between patients who had been newly recruited, having not participated in the original trial (‘rifaximin-newly recruited’ group), with those who received rifaximin in the original randomized controlled trial (‘rifaximin-RCT’ group) and those who received placebo in the original trial (‘placebo-RCT’ group) 17. The rates of OHE recurrence were 772.1, 687.2 and 652.1 events/1000 person-years for the rifaximin-newly recruited, rifaximin-RCT and placebo-RCT groups, respectively (P=not significant between groups), and the corresponding mortality rates were 170.5, 134.1 and 168.5 events/1000 patient years, respectively (P=not significant between groups) 17.

In addition to these prospective data, several large retrospective studies have assessed the effectiveness of rifaximin+lactulose in comparison with lactulose alone. The IMPRESS study was a multicenter, retrospective, observational study of 207 patients with HE, 84% of whom received concomitant lactulose, designed to assess the effect of rifaximin-α 550 mg on hospital resource use 22. Outcomes were compared for the 6 months before starting rifaximin (‘pre-rifaximin’) versus the 6 months following rifaximin initiation (‘post-rifaximin’), and for 12 months pre-rifaximin versus 12 months post-rifaximin. OHE episodes were experienced by 57% of patients in the 12 months pre-rifaximin versus 38% in the 12 months post-rifaximin 22. The mean number of HE episodes per patient decreased significantly from the 12 months pre-rifaximin to the 12 months post-rifaximin (P=0.047) 22.

A single-center, retrospective, cohort study compared the effectiveness of rifaximin (600 mg, twice daily)+lactulose versus lactulose alone in patients with cirrhosis-related HE who either did or did not have hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) 24. Median follow-up was 18.0 months in the non-HCC population (n=421) and 4.4 months in the HCC population (n=621) 24. In the non-HCC population, the rate of HE recurrence was 15.9% for rifaximin+lactulose versus 33.3% for lactulose alone (P<0.001), and the overall mortality rate was 36.6% for rifaximin+lactulose versus 56.9% for lactulose alone (P=0.02) 24. Furthermore, NNT analysis showed that 9.6 patients without HCC would need to be treated with rifaximin to increase the survival rate of one patient each year 24. In the HCC population, the rate of HE recurrence was 19.1% for rifaximin+lactulose versus 29.2% for lactulose alone (P=0.03), and the overall mortality rate was 75.1% for rifaximin+lactulose versus 82.8% for lactulose alone (P=not significant) 24. In both the non-HCC and HCC populations, rates of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and variceal bleeding were significantly lower for rifaximin+lactulose versus lactulose alone 24. Finally, a single-center, retrospective, cohort study of patients admitted for HE compared the effectiveness of rifaximin-α 550 mg+lactulose (n=62) versus lactulose alone (n=87) over 180 days 20. The rate of HE-related hospital readmission was significantly lower with rifaximin+lactulose versus lactulose alone (2.4 vs. 16.2%; P=0.028), but the rate of all-cause hospital readmission was not significantly different between groups, and neither were the median length of hospital stay or the rate of mortality 20.

Studies have also assessed the effectiveness of different rifaximin treatment regimens when used in addition to lactulose therapy. No significant differences were observed between patients treated with rifaximin-α 550 mg once-daily versus twice daily 25, or between patients treated with rifaximin-α 550 mg twice daily versus rifaximin 400 mg, three times daily; although rifaximin-α 550 mg twice daily was shown to be more cost-effective than the three times daily regimen 27.

Direct head-to-head evidence of the long-term effectiveness of rifaximin versus lactulose is scarce. In a single-center, retrospective chart review, 145 patients diagnosed with HE received at least 6 months of treatment with lactulose before receiving at least 6 months of treatment with rifaximin (400 mg, three times daily), and outcomes were compared for the last 6 months of lactulose treatment versus the first 6 months of rifaximin treatment 26. The number of hospitalizations per patient was significantly lower with rifaximin versus lactulose (0.5 vs. 1.6; P<0.001), as was the number of days of hospitalization per patient (2.5 vs. 7.3; P<0.001) and number of weeks of hospitalization per patient (0.4 vs. 1.8; P<0.001) 26. Rifaximin was also compared with lactulose in a single-center, prospective study, designed to investigate for how long patients with MHE should be treated 21. Patients with cirrhosis with MHE were randomized to receive primary prophylaxis treatment with either rifaximin (400 mg, three times daily) or lactulose for 3 months, and then followed up for a further 6 months 21. After 9 months, the rate of MHE recurrence was 47.6% for rifaximin versus 42.1% for lactulose (P=not significant), and the rate of OHE occurrence was 7.1% for rifaximin versus 7.9% with lactulose (P=not significant) 21.

Only one long-term study has assessed the effectiveness of rifaximin monotherapy with that of rifaximin+lactulose therapy 31. Compared with rifaximin+lactulose, the calculated NNT value (95% CI) for rifaximin monotherapy as secondary prophylaxis for OHE recurrence was 6.88 (3.50–203.90) (Fig. 2). This was a multicenter, retrospective, chart review comparing 1-year outcomes of 149 patients with cirrhosis treated with rifaximin (400–1600 mg/day) with those of 54 patients treated with rifaximin+lactulose 31. The rate of maintenance of HE remission for 1 year was 81% with rifaximin monotherapy versus 67% with rifaximin+lactulose 31. Mean time to a breakthrough OHE event was 210 days with rifaximin monotherapy versus 90 days with rifaximin+lactulose 31. HE-related hospitalization rates were similar with rifaximin (43%) and rifaximin+lactulose (39%) 31. In both groups, response to rifaximin appeared to be enhanced in patients with a mean baseline model for end-stage liver disease score of less than or equal to 20 31. These findings appear to contrast with those of a single-center, retrospective, observational study of 225 patients evaluated for liver transplantation, all of whom were treated with rifaximin-α 550 mg+lactulose for 6 months, which showed a lower rate of HE-related hospitalization in patients with a model for end-stage liver disease score of at least 20 versus less than 20 (1.6 vs. 2.5 per 6 months) 29.

Safety/tolerability of long-term (>_6 months) treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with rifaximin and/or lactulose

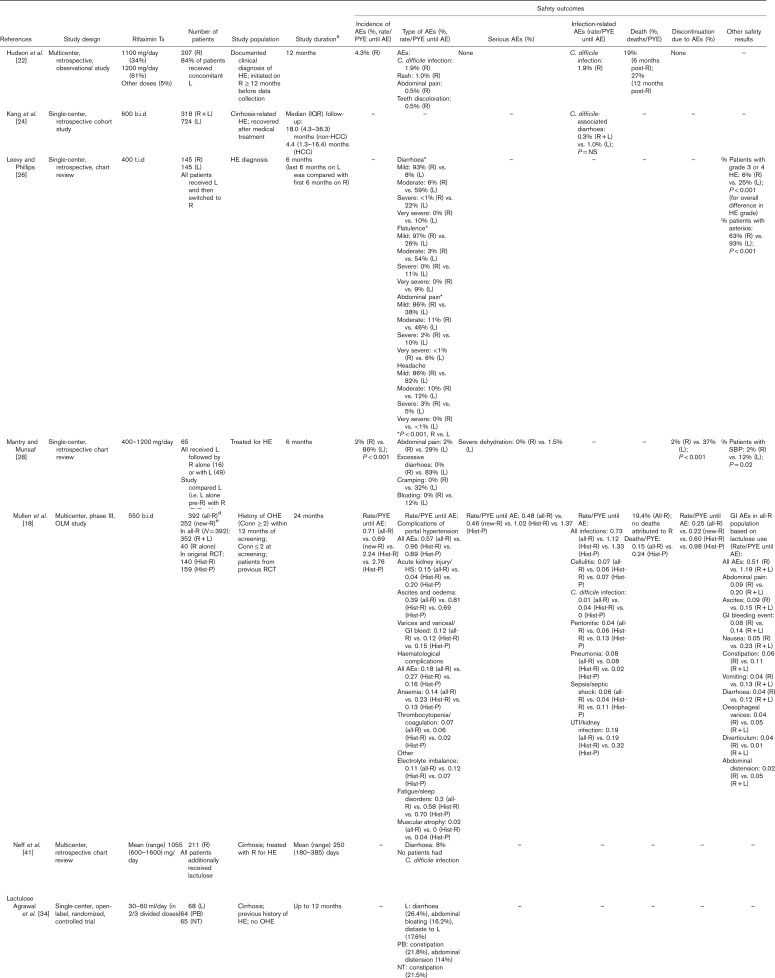

Manual assessment of the articles containing primary clinical data identified six articles reporting long-term safety/tolerability outcomes for treatment with lactulose alone and a further nine articles reporting long-term safety/tolerability outcomes for treatment of HE with rifaximin, alone or in combination with lactulose (Table 2). Details of studies including more than 100 patients are summarized in more detail later.

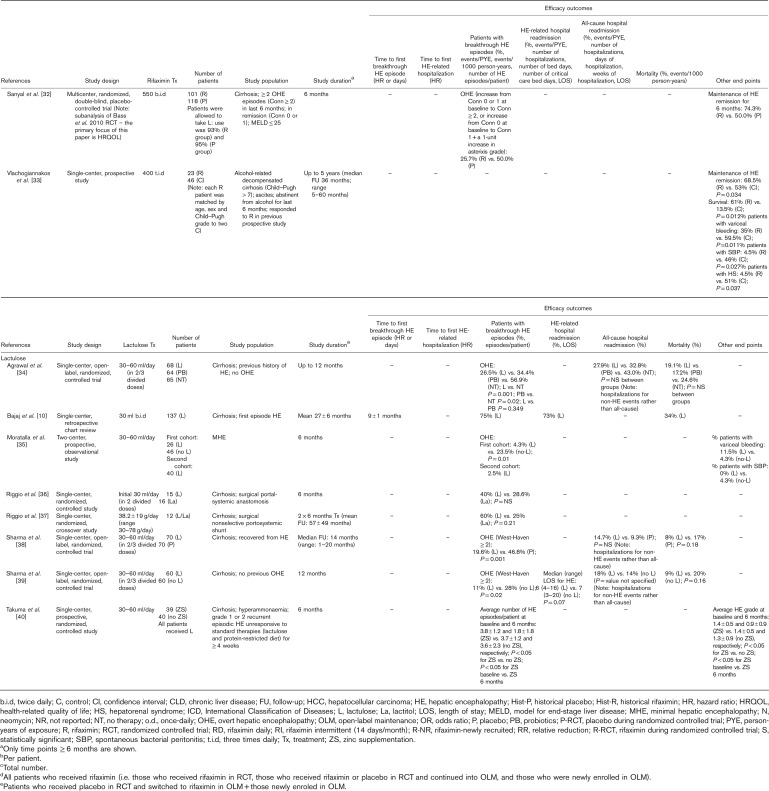

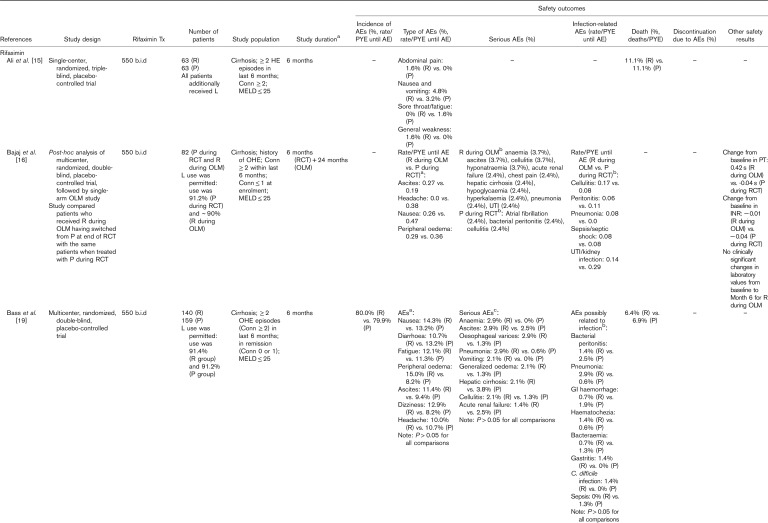

Table 2.

Articles reporting safety/tolerability outcomes over the long term (≥6 months) for patients treated with rifaximin and/or lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy. Articles reporting data for rifaximin and lactulose are presented in the rifaximin section; those reporting data for lactulose, but not rifaximin, are presented in the lactulose section

Table 2.

(Continued)

Table 2.

(Continued)

Lactulose alone

Three large single-center, open-label, randomized, controlled studies have assessed the long-term (≥6 months) safety/tolerability of lactulose therapy, compared with placebo, probiotics and/or no therapy 34,38,39. In a primary prophylaxis study, in which patients with cirrhosis but no previous history of OHE were randomized to receive lactulose therapy (n=60) or no lactulose therapy (n=60) for 12 months, all patients treated with lactulose remained adherent to treatment 39. The most commonly reported adverse events (AEs) with lactulose were diarrhea, distaste to lactulose and abdominal bloating, which improved following reduction of lactulose dosing 39. In a secondary prophylaxis study, in which patients with cirrhosis who had recovered from OHE were randomized to receive lactulose (n=68), probiotics (n=64) or no therapy (n=65) for up to 12 months, all lactulose patients remained adherent to treatment 34. AEs in the lactulose group again comprised diarrhea, distaste to lactulose and abdominal bloating 34. Lactulose dosing was reduced in these patients but not stopped. In the probiotics group, AEs comprised constipation and abdominal distension, which were managed with dietary advice and on-and-off use of proton pump inhibitors 34. In the no therapy group, only constipation was reported, which was managed with dietary modifications 34. Similar results were observed in another secondary prophylaxis study, in which patients were randomized to receive lactulose or placebo over a median follow-up duration of 14 months 38. All patients remained adherent to lactulose therapy, and AEs in the lactulose group comprised diarrhea, distaste to lactulose and abdominal bloating 38. Lactulose dosing was decreased in these patients but not stopped. In the placebo group, the only AE was constipation, which was managed with dietary modifications 38.

Rifaximin with or without lactulose

In the phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, carried out by Bass et al. 19, which compared rifaximin-α 550 mg (n=140) versus placebo (n=159) for the prevention of OHE recurrence over 6 months (concomitant lactulose use >90% in both groups), the overall incidence of AEs was 80.0% with rifaximin versus 79.9% with placebo. The most commonly reported AEs (≥10% of patients in either group) were nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, peripheral edema, ascites, dizziness and headache, but there were no significant differences between treatment groups 19. There were also no significant differences between groups in the incidences of serious AEs and AEs related to infection, including Clostridium difficile infection 19. Deaths occurred in 6.4 and 6.9% of rifaximin-treated and placebo-treated patients, respectively 19.

In the similarly designed single-center, randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial carried out by Ali et al. 15, the incidence of AEs was low and similar in patients treated with rifaximin-α 550 mg (n=63) or placebo (n=63) for 6 months, in addition to lactulose therapy. Deaths occurred in 11.1% of patients in both treatment groups 15.

In the 24-month, open-label maintenance study that followed the trial by Bass and colleagues, a total 392 patients were treated with rifaximin-α 550 mg (‘all-rifaximin’ group), including 252 patients who received de novo treatment (82 patients who received placebo in the original trial and 170 newly recruited patients; ‘new-rifaximin’ group) 18. Approximately 90% of the patients in the all-rifaximin group additionally received treatment with lactulose. Safety/tolerability results were compared with those for patients who received rifaximin and placebo in the original phase III trial [‘historical-rifaximin’ (n=140) and ‘historical-placebo’ (n=159) groups, respectively]. The overall rates of AEs/PYE were lower in the all-rifaximin (0.71) and new-rifaximin (0.69) groups than in the historical-rifaximin (2.24) and historical-placebo (2.76) groups 18, as were the rates of serious AEs/PYE and discontinuation owing to AEs (rate/PTE) 18. The rate of death/PYE was 0.15 in the all-rifaximin group compared with 0.24 in the historical-placebo group 18. The rate of C. difficile infection remained stable with long-term rifaximin treatment 18. When comparing patients who received rifaximin in combination with lactulose (n=352) with those who received rifaximin alone (n=40), the incidence of gastrointestinal-related AEs was significantly higher in the combination therapy group than in the monotherapy group (69.6 vs. 47.5%; P<0.001), including the incidences of nausea and abdominal pain 18.

In the multicenter, retrospective, observational IMPRESS study of 207 patients with HE (all of whom were treated with rifaximin-α 550 mg and 84% of whom received concomitant lactulose), 4.3% of patients had documented AEs, most commonly C. difficile infection (n=4) and rash (n=2) 22. No serious AEs were reported. Of the four patients who developed C. difficile infection, none had a history of C. difficile and none was on concomitant antibiotics. All patients continued rifaximin therapy 22. In a single-center, retrospective, cohort study that compared the effectiveness of rifaximin (600 mg, twice daily)+lactulose (n=318) versus lactulose alone (n=724) in patients with cirrhosis-related HE who either did or did not have HCC, C. difficile infection rates were 0.3% with rifaximin+lactulose versus 1.0% with lactulose alone, over a median follow-up duration of 18.0 months in patients without HCC and 4.4 months in patients with HCC 24. In a multicenter, retrospective chart review of 211 patients treated with rifaximin (mean: 1055 mg/day; range: 600–1600 mg/day), in addition to lactulose, over a mean follow-up duration of 250 days, 8% of patients experienced diarrhea but none experienced C. difficile infection 41. All cases of diarrhea were resolved with standard antidiarrheal therapy, which was administered after stool analysis excluded C. difficile infection 41.

Direct head-to-head evidence of the long-term safety/tolerability of rifaximin versus lactulose is limited to a single-center, retrospective chart review, in which 145 patients diagnosed with HE received at least 6 months of treatment with lactulose before receiving at least 6 months of treatment with rifaximin (400 mg, three times daily) 26. Outcomes were compared for the last 6 months of lactulose treatment versus the first 6 months of rifaximin treatment 26. The percentages of patients with diarrhea, flatulence and abdominal pain were significantly higher during the lactulose period than the rifaximin period (P<0.001 for all) 26. There was no significant difference in the percentage of patients with headache, which was the only other AE reported 26.

Discussion

This systematic review shows an increasing body of evidence for the use of rifaximin in addition to lactulose, and for lactulose therapy alone, in the long-term management of patients with HE. In line with the current guidelines 1, this evidence supports the use of lactulose therapy as secondary prophylaxis for the prevention of recurrence of OHE events over the long term 34,35,38. In addition, one study has showed the effectiveness of lactulose as primary prophylaxis in the prevention of long-term OHE occurrence 39. Although there is very little direct head-to-head evidence of rifaximin versus lactulose over the long term, there is considerable evidence to support recommendations for the use of rifaximin as an add-on treatment to standard lactulose therapy in the secondary prophylaxis setting 1.

In terms of effectiveness, several long-term, open-label clinical trials and clinical practice studies have showed that, when added to lactulose therapy, rifaximin significantly reduces the recurrence of OHE events and rate of HE-related hospitalization, in comparison with lactulose therapy alone 16,19,20,22,24,28. An exception to this was a single-center, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, carried out by Ali et al., in which rifaximin was found to be no better than placebo when combined with lactulose therapy as secondary prophylaxis against OHE recurrence 15. In discussing the potential reasons for the discrepancy in the findings of this trial, compared with those of the phase III trial by Bass et al. 19, the authors point out that the study populations differed in terms of primary etiology of cirrhosis, geographical and dietary background 15. The authors therefore speculated that the gut flora 42–44 of the two study populations might have differed. Nevertheless, the majority of current evidence supports an enhanced therapeutic benefit in adding rifaximin to lactulose therapy for the prevention of OHE recurrence and HE-related hospitalization.

Historically, the NNT measure was designed to quantify treatment benefit directly in terms of the number of patients who would need to be treated before benefit is observed, thereby providing a means of expressing absolute, as opposed to relative, risk in a clinically meaningful way 45–47. Although the number of studies eligible for inclusion in the current NNT analyses was limited, the results showed that, in terms of long-term secondary prophylaxis for the prevention of OHE recurrence, approximately four patients would need to be treated with lactulose before clinical benefit is observed, compared with no treatment or placebo. This must be considered within the clinical context showing a very high rate of OHE recurrence with no prophylaxis or with poor adherence to lactulose therapy. Importantly, to show the add-on benefit of rifaximin to lactulose, the NNT is approximately four patients to prevent the recurrence of OHE. The relatively low NNT value for adding rifaximin to lactulose therapy provides further support for the clinical benefit of these treatments for the prevention of OHE recurrence over the long term. Only one study compared rifaximin monotherapy versus rifaximin+lactulose, and NNT analysis showed that approximately seven patients would need to be treated with rifaximin monotherapy before clinical benefit is observed (in comparison with rifaximin+lactulose). However, the results of this single study should be viewed with caution, not only because the 95% CI was very wide but also because the study design was such that patients who received rifaximin monotherapy may have had less severe HE than those who received combination therapy, which may have affected their likelihood of long-term remission 31.

For chronic conditions such as HE, the success of treatment is dependent on its tolerability, as patients will only adhere to treatment if they are able to tolerate it over the long term. Long-term tolerability problems, such as adverse gastrointestinal symptoms, also have a major effect on health-related quality of life 48. In the case of lactulose, tolerability is a major clinical consideration. In a study of 137 patients who received long-term secondary prophylaxis with lactulose, 75% experienced OHE recurrence, and this was associated with lactulose nonadherence in 38% of these patients, mainly because of gastrointestinal adverse effects, such as unpredictable diarrhea, abdominal pain and bloating 10. Crucially, all patients who were nonadherent on lactulose therapy, and nearly two-thirds of those who were adherent, experienced OHE recurrence 10. There is evidence to suggest that patient acceptance of lactulose is influenced by sociocultural factors; for example, in a recent survey of 100 outpatients with cirrhosis from India and the USA, who did not have previous or current experience with lactulose but who underwent dedicated education about its use for HE prevention, a significantly higher proportion of Indian versus US patients agreed to accept lactulose treatment 49. In this context, it is perhaps noteworthy that a substantial number of the lactulose studies identified in this review were carried out in patients from the Indian subcontinent. Taken together, such findings highlight the need for additional, effective and better tolerated therapeutic options in the long-term management of HE, across all sociocultural patient groups.

In the 6-month phase III trial that compared rifaximin-α 550 mg with placebo for the prevention of OHE recurrence in patients in HE remission, more than 90% of whom were additionally treated with lactulose, the overall incidence of AEs was the same in both groups, and there were no significant between-group differences in the incidence of the most commonly reported AEs and serious AEs 19. In the 24-month open-label maintenance study that followed this trial, the incidences of total AEs, serious AEs and AEs leading to discontinuation were lower than those observed in the rifaximin and placebo arms of the original 6-month trial 18. In addition, long-term retrospective studies have showed a low incidence of AEs when rifaximin is added to lactulose therapy in clinical practice 22,41. As with nearly all antibacterial agents, C. difficile-associated diarrhea has been reported with rifaximin treatment 13. However, this has not emerged as a major safety concern following long-term treatment in clinical trials 18,19 and in clinical practice studies 22,24,41.

HE is associated with a substantial economic burden, primarily because of the direct costs of hospitalization and rehospitalization following recurrence, and secondarily because of the indirect costs associated with outpatient care, disability, lost productivity and the wider negative effect on the lives of patients’ caregivers 1,50,51. As previously discussed, current evidence for the long-term treatment of HE with rifaximin as an add-on to lactulose therapy demonstrates that it not only significantly decreases OHE recurrence, in comparison with lactulose therapy alone, but also significantly reduces the rate of HE-associated hospitalization and length of hospital stay 16,19,20,22,24,28,52. There is therefore a substantial body of evidence showing that the addition of rifaximin to standard lactulose therapy results in significant reductions in healthcare resource utilization over the long term.

A limitation of this systematic review was that, following a thorough assessment of the available data, meta-analysis of outcome measures was found to be unfeasible and inappropriate, because of the heterogeneity of the designs, treatment settings and patient populations of the studies that were identified. NNT analysis was also limited by the low number of studies that could be assessed in this way.

Conclusion

Current evidence supports recommendations for the use of lactulose therapy for the prevention of OHE recurrence over the long term, and for the additional benefit of adding rifaximin to lactulose therapy. The addition of rifaximin to lactulose significantly further reduces the risk of OHE recurrence and HE-related hospitalization, compared with lactulose therapy alone, with a demonstrably low NNT to achieve these further benefits. There is also emerging evidence to indicate that a switch to rifaximin monotherapy may be appropriate for those for whom lactulose is ineffective and/or poorly tolerated, and/or when adherence to lactulose therapy is problematic, although this requires further research.

Acknowledgements

Editorial support was provided by John Scopes of mXm Medical Communications and funded by Norgine.

Conflicts of interest

M.H.: Speaker fees and travel expenses from Norgine, Astellas, Janssen and AbbVie; in addition, advisory board honoraria from Norgine and Novartis. M.S.: Lecture and travel fees from AbbVie, Gilead, Falk and Norgine; in addition, advisory board honoraria from AbbVie and Norgine.

References

- 1.American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 practice guideline by the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. J Hepatol 2014; 61:642–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elwir S, Rahimi RS. Hepatic encephalopathy: an update on the pathophysiology and therapeutic options. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2017; 5:142–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferenci P. Hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2017; 5:138–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams R. Review article: bacterial flora and pathogenesis in hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25 (Suppl 1):17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordoba J, Ventura-Cots M, Simón-Talero M, Amorós À, Pavesi M, Vilstrup H, et al. CANONIC Study Investigators of EASL-CLIF Consortium. Characteristics, risk factors, and mortality of cirrhotic patients hospitalized for hepatic encephalopathy with and without acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). J Hepatol 2014; 60:275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chacko KR, Sigal SH. Update on management of patients with overt hepatic encephalopathy. Hosp Pract (1995) 2013; 41:48–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neff GW, Kemmer N, Duncan C, Alsina A. Update on the management of cirrhosis - focus on cost-effective preventative strategies. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2013; 5:143–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bajaj JS, Wade JB, Gibson DP, Heuman DM, Thacker LR, Sterling RK, et al. The multi-dimensional burden of cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy on patients and caregivers. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:1646–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu A, Perumpail RB, Kumari R, Younossi ZM, Wong RJ, Ahmed A. Advances in cirrhosis: optimizing the management of hepatic encephalopathy. World J Hepatol 2015; 7:2871–2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bajaj JS, Sanyal AJ, Bell D, Gilles H, Heuman DM. Predictors of the recurrence of hepatic encephalopathy in lactulose-treated patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 31:1012–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott LJ. Rifaximin: a review of its use in reducing recurrence of overt hepatic encephalopathy episodes. Drugs 2014; 74:2153–2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bajaj JS. Review article: potential mechanisms of action of rifaximin in the management of hepatic encephalopathy and other complications of cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016; 43 (Suppl 1):11–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norgine Limited. TARGAXAN summary of product characteristics; 2016. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/27427. [Accessed 16 October 2018].

- 14.Alvares-da-Silva MR, de Araujo A, Vicenzi JR, da Silva GV, Oliveira FB, Schacher F, et al. Oral l-ornithine-l-aspartate in minimal hepatic encephalopathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Hepatol Res 2014; 44:956–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali B, Zaidi YA, Alam A, Anjum HS. Efficacy of Rifaximin in prevention of recurrence of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis of liver. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2014; 24:269–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bajaj JS, Barrett AC, Bortey E, Paterson C, Forbes WP. Prolonged remission from hepatic encephalopathy with rifaximin: results of a placebo crossover analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 41:39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bannister CA, Orr JG, Reynolds AV, Hudson M, Conway P, Radwan A, et al. Natural history of patients taking rifaximin-α for recurrent hepatic encephalopathy and risk of future overt episodes and mortality: a post-hoc analysis of clinical trials data. Clin Ther 2016; 38:1081.e4–1089.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mullen KD, Sanyal AJ, Bass NM, Poordad FF, Sheikh MY, Frederick RT, et al. Rifaximin is safe and well tolerated for long-term maintenance of remission from overt hepatic encephalopathy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12:1390.e2–1397.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A, Poordad F, Neff G, Leevy CB, et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1071–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Courson A, Jones GM, Twilla JD. Treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy: comparing the effects of adding rifaximin to lactulose on patient outcomes. J Pharm Pract 2016; 29:212–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goyal O, Sidhu SS, Kishore H. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis- how long to treat? Ann Hepatol 2017; 16:115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudson M, Radwan A, Di Maggio P, Cipelli R, Ryder SD, Dillon JF, et al. The impact of rifaximin-α on the hospital resource use associated with the management of patients with hepatic encephalopathy: a retrospective observational study (IMPRESS). Frontline Gastroenterol 2017; 8:243–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irimia R, Trifan A. Efficacy of rifaximin versus lactulose for reducing the recurrence of overt hepatic encephalopathy and hopitalizations in cirrhosis. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi 2012; 116:1021–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang SH, Lee YB, Lee JH, Nam JY, Chang Y, Cho H, et al. Rifaximin treatment is associated with reduced risk of cirrhotic complications and prolonged overall survival in patients experiencing hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 46:845–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khokhar N, Qureshi MO, Ahmad S, Ahmad A, Khan HH, Shafqat F, et al. Comparison of once a day rifaximin to twice a day dosage in the prevention of recurrence of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with chronic liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 30:1420–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leevy CB, Phillips JA. Hospitalizations during the use of rifaximin versus lactulose for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Dig Dis Sci 2007; 52:737–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lyon KC, Likar E, Martello JL, Regier M. Retrospective cross-sectional pilot study of rifaximin dosing for the prevention of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 32:1548–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mantry PS, Munsaf S. Rifaximin for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Transplant Proc 2010; 42:4543–4547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mantry PS, Mehta A, Graydon R. Efficacy and tolerability of rifaximin in combination with lactulose in end-stage liver disease patients with MELD greater than 20: a single center experience. Transplant Proc 2014; 46:3481–3486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miglio F, Valpiani D, Rossellini SR, Ferrieri A. Rifaximin, a non-absorbable rifamycin, for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. A double-blind, randomized trial. Curr Med Res Opin 1997; 13:593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neff GW, Jones M, Broda T, Jonas M, Ravi R, Novick D, et al. Durability of rifaximin response in hepatic encephalopathy. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012; 46:168–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanyal A, Younossi ZM, Bass NM, Mullen KD, Poordad F, Brown RS, et al. Randomised clinical trial: rifaximin improves health-related quality of life in cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34:853–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vlachogiannakos J, Viazis N, Vasianopoulou P, Vafiadis I, Karamanolis DG, Ladas SD. Long-term administration of rifaximin improves the prognosis of patients with decompensated alcoholic cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 28:450–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agrawal A, Sharma BC, Sharma P, Sarin SK. Secondary prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis: an open-label, randomized controlled trial of lactulose, probiotics, and no therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107:1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moratalla A, Ampuero J, Bellot P, Gallego-Durán R, Zapater P, Roger M, et al. Lactulose reduces bacterial DNA translocation, which worsens neurocognitive shape in cirrhotic patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Liver Int 2017; 37:212–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riggio O, Balducci G, Ariosto F, Merli M, Pieche U, Pinto G, et al. Lactitol in prevention of recurrent episodes of hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients with portal-systemic shunt. Dig Dis Sci 1989; 34:823–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riggio O, Balducci G, Ariosto F, Merli M, Tremiterra S, Ziparo V, et al. Lactitol in the treatment of chronic hepatic encephalopathy: a randomized cross-over comparison with lactulose. Hepatogastroenterology 1990; 37:524–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma BC, Sharma P, Agrawal A, Sarin SK. Secondary prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy: an open-label randomized controlled trial of lactulose versus placebo. Gastroenterology 2009; 137:885–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma P, Sharma BC, Agrawal A, Sarin SK. Primary prophylaxis of overt hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: an open labeled randomized controlled trial of lactulose versus no lactulose. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 27:1329–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takuma Y, Nouso K, Makino Y, Hayashi M, Takahashi H. Clinical trial: oral zinc in hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 32:1080–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neff GW, Jones M, Jonas M, Ravinuthala R, Novick D, Kaiser TE, et al. Lack of Clostridium difficile infection in patients treated with rifaximin for hepatic encephalopathy: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013; 47:188–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marathe N, Shetty S, Lanjekar V, Ranade D, Shouche Y. Changes in human gut flora with age: an Indian familial study. BMC Microbiol 2012; 12:222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Escobar JS, Klotz B, Valdes BE, Agudelo GM. The gut microbiota of Colombians differs from that of Americans, Europeans and Asians. BMC Microbiol 2014; 14:311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bajaj JS, Idilman R, Mabudian L, Hood M, Fagan A, Turan D, et al. Diet affects gut microbiota and modulates hospitalization risk differentially in an international cirrhosis cohort. Hepatology 2018; 68:234–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laupacis A, Sackett DL, Roberts RS. An assessment of clinically useful measures of the consequences of treatment. N Engl J Med 1988; 318:1728–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weeks DL, Noteboom JT. Using the number needed to treat in clinical practice. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85:1729–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akobeng AK. Communicating the benefits and harms of treatments. Arch Dis Child 2008; 93:710–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalaitzakis E, Simrén M, Olsson R, Henfridsson P, Hugosson I, Bengtsson M, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with liver cirrhosis: associations with nutritional status and health-related quality of life. Scand J Gastroenterol 2006; 41:1464–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rathi S, Fagan A, Wade JB, Chopra M, White MB, Ganapathy D, et al. Patient acceptance of lactulose varies between Indian and American cohorts: implications for comparing and designing global hepatic encephalopathy trials. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2018; 8:109–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poordad FF. Review article: the burden of hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25 (Suppl 1):3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stepanova M, Mishra A, Venkatesan C, Younossi ZM. In-hospital mortality and economic burden associated with hepatic encephalopathy in the United States from 2005 to 2009. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10:1034.e1–1041.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orr JG, Currie CJ, Berni E, Goel A, Moriarty KJ, Sinha A, et al. The impact on hospital resource utilization of treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with rifaximin-α. Liver Int 2016; 36:1295–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]