Abstract

RIPK1 has emerged as a key effector in programmed necrosis or necroptosis. This function of RIPK1 is mediated by its protein serine/threonine kinase activity and through the downstream kinase RIPK3. Deletion of RIPK1 prevents embryonic lethality in mice lacking FADD, a signaling adaptor protein required for activation of Caspase 8 in extrinsic apoptotic pathways. This indicates that FADD-mediated apoptosis inhibits RIPK1-dependent necroptosis to ensure successful embryogenesis. However, the molecular mechanism for this critical regulation remains unclear. In the current study, a novel mouse model has been generated, by disrupting a potential caspase cleavage site at aspartic residue (D)324 in RIPK1. Interestingly, replacing D324 with alanine (A) in RIPK1 results in midgestation lethality, similar to the embryonic defect in FADD−/− mice but in stark contrast to the normal embryogenesis of RIPK1−/− null mutant mice. Surprisingly, disrupting the downstream RIPK3 alone is insufficient to rescue RIPK1D324A/D324A mice from embryonic lethality, unless FADD is deleted simultaneously. Further analyses reveal a paradoxical role for RIPK1 in promoting caspase activation and apoptosis in embryos, a novel mechanism previously unappreciated.

Introduction

Apoptosis is a major form of programmed cell death (PCD) and is executed by Caspases1. When PCD signaling pathways become dysregulated, developmental defects can occur at embryonic or postnatal stages. While apoptosis has been studied since the 1970s, necroptosis is a recently described form of PCD that is usually kept latent2–5. When apoptosis is disrupted, cell death signaling skews towards necroptosis, in which receptor interacting protein kinase 1 (RIP, RIP1 or RIPK1) and RIPK3 serve as key signaling effectors6–10. These two protein serine/threonine kinases interact with one another via their RIP homotypic interaction motif. This results in phosphorylation of both RIPK1 and RIPK3, leading to recruitment and activation of the mixed lineage kinase domain like (MLKL) protein. Once activated, MLKL translocates to and disrupts the plasma membrane11,12. Loss of membrane integrity during necroptosis results in the release of cellular contents, leading to inflammatory responses13.

In the immune system, PCD is required for maintaining homeostasis and suppression of autoimmunity14. The extrinsic pathway is triggered by the death receptors (DRs) including Fas and TNFR1, in which the FADD adaptor recruits Caspase 8, leading to apoptosis. RIPK1 has long been studied as a mediator of NFκB activation during pro-survival and pro-inflammatory signaling, until it became evident that RIPK1 also plays a role in an alternative death pathway, necroptosis, especially when apoptosis is compromised in various cell lines6,7,15. Studies by us and others provide evidence that RIPK1 and RIPK3-mediated necroptosis indeed occurs in vivo16–19, which helps explain the initial paradoxical observations of embryonic lethality in FADD−/− or Caspase 8−/− mice20–22. Moreover, RIPK1-mediated necroptosis leads to defect in mature T and B lymphocytes lacking FADD or Caspase 816,23,24. In total, these data indicate that successful embryogenesis and normal TCR-induced proliferative responses require FADD-mediated suppression of RIPK1 and RIPK3-dependent necroptosis in vivo.

RIPK1-mediated necroptosis also occurs in neuronal cells, which leads to neurodegenerative pathologies3. Apoptotic cells are engulfed by phagocytic cells, which prevents spillage of intracellular contents, and thus limits tissue damage and inflammation14,25,26. Therefore, there is a clear benefit for avoiding necrosis. Currently, it remains unclear how FADD-mediated signaling keeps RIPK1-mediated necroptosis latent. One possibility is that RIPK1 is disabled via cleavage by Caspase 8 activated through FADD. Indeed, an earlier study indicated aspartic acid residue (D)324 of RIPK1 being targeted by Caspase 827. However, this study argues that cleavage of RIPK1 by Caspase 8 promotes apoptosis, and there is currently a lack of definitive in vivo evidence to support this model or suggest an alternative mechanism. To address this paradox, we have developed a novel mouse model using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing to inactivate a predicted caspase cleavage site within the intermediate domain of RIPK1. Our data reveals a new mechanism in the regulation of RIPK1, indicating that RIPK1 resistance to Caspases not only facilitates necroptosis, but also promotes apoptosis in mouse embryos.

Results

Targeting the predicted Caspase 8 cleavage site in RIPK1 through CRIPSR/Cas9-mediated gene editing

A potential mechanism for suppression of RIPK1-dependent necroptosis is that FADD-mediated activation of caspases may lead to cleavage of RIPK1. A previous in vitro study indicated that RIPK1 could be a target of Caspase 827. In particular, Caspase 8 appears to cleave RIPK1 in vitro at aspartic acid (D) residue 324. To test this potential mechanism in vivo, we generated a novel mouse model in which D324 in RIPK1 was replaced with alanine (A) through the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing strategy28. DNA sequencing analysis of the founder mice in the C57BL/6 background confirmed the resulting D324A mutation (Supplementary Fig. S1). We found that the heterozygous RIPK1+/D324A founders were fertile, and when backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice, transmitted the mutant allele to the offspring. We found that heterozygous RIPK1+/D324A mutant mice contained normal numbers of T cells and B cells in the primary and secondary lymphoid organs (data not shown). This indicates that the D324A mutation does not impose a dominant-negative effect.

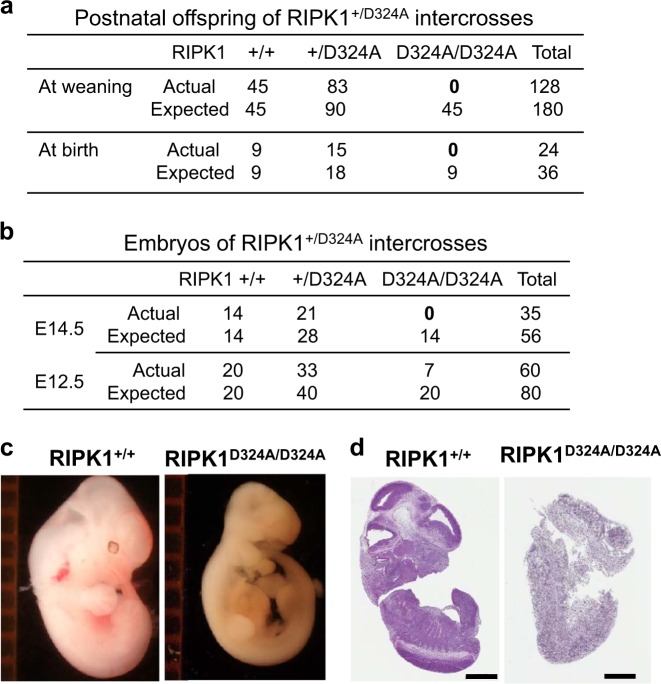

We then carried out intercrosses of the heterozygous RIPK1+/D324A mice. Interestingly, no homozygous RIPK1D324A/D324A mutant mice were detected in the offspring at the weaning age (Fig. 1a, top) or at birth (Fig. 1a, bottom). This data indicates that RIPK1D324A/D324A mutant mice die before birth. Therefore, we performed timed mating analyses, but again found no homozygous RIPK1D324A/D324A mutant embryos at embryonic (E) day 14.5 from intercrosses of heterozygous RIPK1+/D324A mutant mice (Fig. 1b, top). Further analysis of earlier stages showed that RIPK1D324A/D324A embryos were present at E12.5, albeit at lower than the predicted Mendelian ratios (Fig. 1b, bottom). When compared with wild type control E12.5 embryos, the RIPK1D324A/D324A mutant E12.5 embryos had a clear developmental defect (Figs. 1c, d). These data indicate that the D324A mutation in RIPK1 results in embryonic lethality around E12.5. This observation is in sharp contrast to normal embryogenesis in RIPK1−/− null mutant mice, as previously reported16.

Fig. 1. Analysis of the impact of the RIPK1 D324A mutation on postnatal and embryogenic development in mice.

RIPK1+/D324A heterozygous mutant mice undergo normal development, and were intercrossed. Genetic analyses of the offspring at weaning age or at birth (a), and at the indicated gestation stages (b), were performed. The RIPK1D324A/D324A homozygous mutants were detected at E12.5, but not at E14.5, at birth or at weaning age. Representative images of whole embryos (c) and H&E staining of embryo sections (d) of mutant and wild type control embryos at E12.5. The ruler division in mm is shown to the left of embryos in (c). Scale bars in (d) = 1 mm

RIPK1D324A/D324A embryonic death is partially dependent on RIPK3

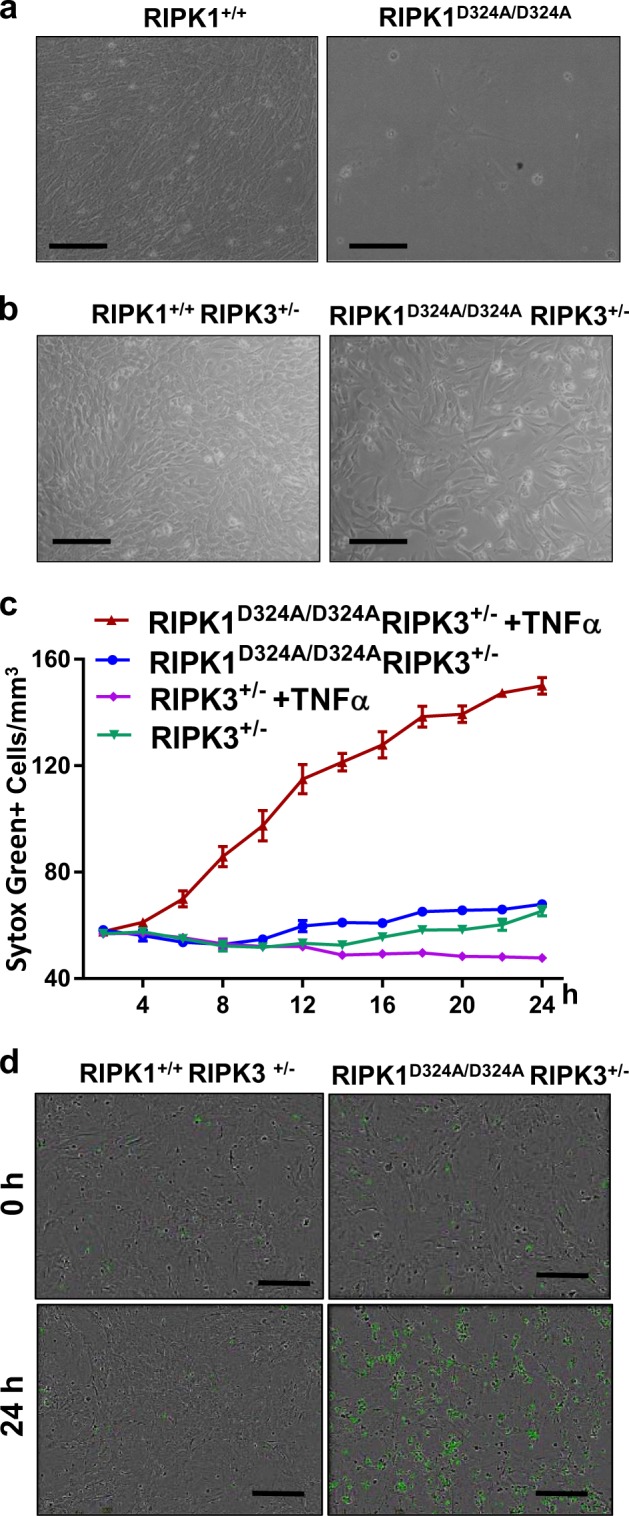

To facilitate further analysis, we prepared mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Interestingly, D324A mutant MEFs displayed dramatically poor viability in culture (Fig. 2a) and we were unable to obtain a sufficient number of cells for further analysis. However, we found that deletion of one allele of RIPK3 improved viability of D324A mutant MEFs (Fig. 2b). We then performed real-time analysis of cell death responses using an IncuCyte system, and found that RIPK1D324/D324 RIPK3+/− MEFs were highly sensitive to cell death induction by TNFα over a 24 h period, as shown by uptake of Sytox Green, whereas RIPK1+/+ RIP3K+/− control MEFs were highly resistant to the cell death induction (Fig. 2c). Snapshot images of cell death at 0 h and 24 h post TNFα treatment also allowed for direct visualization of the greatly increased cell death in RIPK1D324/D324 RIPK3+/− MEFs, compared with RIPK1+/+ RIPK3+/− control MEFs (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2. The RIPK1 D324A mutation leads to hypersensitivity to cell death responses.

Images of MEFs with indicated genotypes prepared from RIPK1+/D324A mouse intercross a or from RIPK1+/D324A RIPK3+/− mouse intercrosses (b). MEF cells of the indicated genotypes were cultured in the presence of SYTOX Green (50 nM), with or without TNFα (50 ng/ml) for 24 h (c). Real-time analysis was performed with an IncyCyte unit instrument. Dying cells are indicated as SYTOX Green+/mm2) and plotted against the indicated time-points. SEM were indicated by errors bars. d Real-time imaging analysis of MEFs treated with TNFα (50 ng/ml) and SYTOX Green (50 nM). Increased cell death is indicated by higher numbers of SYTOX Green+ cells in RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3+/− MEF, compared to RIPK1+/D324A RIPK3+/− control. The data represent at least three independent experiments. Scale bars in (a) and (b) = 100 μm, and in (d) = 300 μm

To determine whether embryonic death in RIPK1D324A/D324A mice is due to RIPK3-mediated necroptosis, RIP1K+/D324A mice were crossed to mice lacking RIPK3. The resulting RIPK1+/D324A RIPK3−/− mice were intercrossed and genetic analysis of the offspring was performed. At weaning age, we detected no viable RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− double mutant mice (Fig. 3a, top). Therefore, we analyzed embryos generated from RIPK1+/D324A RIPK3−/− mouse intercrosses and found that RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− double mutant embryos were present from E12.5 to E17.5 (Fig. 3a, bottom). Although RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− double mutant embryos appeared normal at E12.5 (Fig. 3b), they displayed an apparent defect by E17.5 (Fig. 3c), as compared to RIPK1+/+ RIPK3+/+ control embryos. Histological analysis revealed cell death at E17.5 in RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− embryos, compared to RIPK1+/+ RIPK3−/− control embryos (Fig. 3d). In total these data indicate that RIPK3-mediated necroptosis is partially responsible for death in RIPK1D324A/D324A embryos.

Fig. 3. RIPK3-mediated necroptosis does not entirely explain the embryonic lethality in RIPK1D324A/D324A mice.

Genetic analysis indicated that RIPK3 deletion was unable to correct the developmental defect, because no viable RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− mice were detected at weaning age (a, upper rows). Analyses of embryos from timed mating show that RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− embryos can be found as late as E17.5 (a, lower rows). Images of embryos of indicated genotypes at E12.5 (b) and E17.5 (c). RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− embryos appear normal at E12.5 (b), unlike the defect in E12.5 RIPK1D324A/D324A (Fig. 1c). However, severe defect in RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− embryos became apparent at E17.5 (c). Histological analysis via H&E staining of the embryos at E17.5 revealed major cell death in the RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− embryo, contrasting the normal histology in RIPK1+/+ RIPK3−/− control (d). Tissues shown represent the fetal liver areas. The ruler division in mm is shown to the left of embryos in (b), (c). Scale bars in (d) =100 μm.

Analysis of RIPK3-independent pathway unleashed in RIPK1D324A/D324A mice

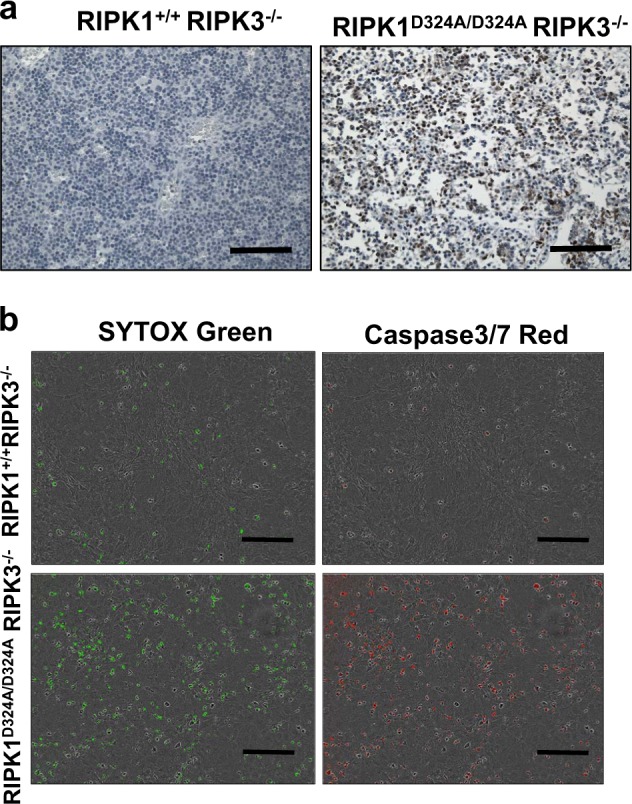

It is interesting that lack of RIPK3 fails to restore normal embryogenesis in RIPK1D324A/D324A mice, indicating that a RIPK3-independent pathway is also responsible in part for death at E17.5. During further analysis of the defect in RIPK1D324A/D324A mice, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays and found that Caspase activities were greatly elevated in RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− embryos, compared to RIPK1+/+ RIPK3−/− embryo control (Fig. 4a). We also analyzed MEFs treated with TNFα using the IncuCyte system for real-time simultaneous detection of cell death and caspase activities. RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− MEFs were hypersensitive to TNFα-induced death, as indicated by Sytox Green uptake (Fig. 4b, left). However, since RIPK3-mediated necroptosis is blocked in RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− MEFs, an alternative form of cell death is occurring. Agreeing with IHC analysis (Fig. 4a), dramatically higher levels of caspase 3/7 activities were detected in RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− MEFs than in control RIPK1+/+ RIPK3−/− MEFs after TNFα treatment (Fig. 4b, right). These data in total suggest a skewing towards apoptotic responses in embryonic cells when RIPK1 is resistant to Caspase 8 via the D324A point mutation and necroptosis is blocked through knockout of RIPK3.

Fig. 4. Caspase activities were greatly elevated in RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− embryos.

Immunohistochemistry analyses of E17.5 embryos of the indicated genotypes through staining with antibodies specific to cleaved Caspase 3 (a). Tissues shown represent the fetal liver areas. MEFs cells were treated with TNFα (50 ng/ml), and SYTOX Green (50 μM) was added to detect cell death (b). At 14 h, Caspase-3/7 red (5 μM) was added and two-color, real-time imaging was performed using an IncuCyte system at 24 h. Increased cell death (Green+, lower left) correlates with increased Caspase 3/7 activities (red+, lower right) in RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− MEFs, when compared with RIPK1+/+ RIPK3−/− control MEFs. Scale bars in (a) = 100 μm, and in (b) = 300 μm

FADD recruits and facilitates Caspase 8 activation during DR-mediated signaling. Given elevated Caspase activation in RIPK1D324/D324A embryos, it is possible that the D324A mutation in RIPK1 facilitates extrinsic apoptosis. To test this, the FADD knockout allele was crossed into RIPK1D324A/D324A mice. However, deletion of FADD provides little improvement to the development of RIPK1D324A/D324A embryos and vice versa. RIPK1D324A/D324A FADD−/−, RIPK1D324A/D324A FADD+/+ and FADD−/− mutant embryos displayed similar developmental blockage (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5. Normal development is restored by simultaneous deletion of both FADD and RIPK3 in RIPK1D324A/D324A mice.

Analysis was performed to determine the effect of disrupting FADD-mediated apoptosis. Defects in the three mutant E12.5 embryos of the indicated genotypes are similar, contrasting normal embryos in the wild type control (a). The ruler division in mm is shown to the left of embryos. At two-month age, RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− FADD−/− (TM) mice are indistinguishable in appearance (b) and in body weights (c) from the wild type (WT) and RIPK3−/− FADD−/− (DKO) control mice. Western blot analysis of total splenocytes confirming presence or absence of RIPK1, RIPK3, and FADD proteins (d). Ponceau S staining (pink) was performed as protein loading and transfer control

We then determined the effect of simultaneous inactivation of both RIPK3 and FADD. To this end, RIPK1+/D324A RIPK3+/− FADD+/− triple heterozygous (THZ) mutant mice were intercrossed. This mating produced no viable RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− mice containing one or both alleles of endogenous FADD. However, viable RIPK1D324A/D324A FADD−/− RIPK3−/− triple mutant mice were detected at weaning age (Fig. 5b). Western blot analysis of total splenocytes confirmed the presence or absence of RIPK1, RIPK3, and FADD protein (Fig. 5d). The resulting triple mutant mice reached adulthood with weight gain similar to wild type control mice as well as FADD−/− RIPK3−/− (DKO) mice (Fig. 5c), and they were fertile. In total, these data indicate that the D324A mutation of RIPK1 promotes both FADD-dependent apoptosis and RIPK3-dependent necroptosis, thus leading to embryonic lethality at midgestation stages, similar to FADD−/− embryonic defect. This is in sharp contrast to RIPK1−/− null mice, which undergo normal embryonic development but die soon after birth.

The impact of RIPK1 D324A mutations on lymphoid compartment

Earlier studies have shown that disruption of the function of FADD by using a FADD-DN mutant or by deletion of FADD in aged RIPK3−/− mice leads to a greatly exaggerated lpr-like symptom16,19,24. We found that the lpr phenotype, characterized as lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly, became apparent in FADD−/− RIPK3−/− double knockout (DKO) mice past 3 months of age (Fig. 6a, middle). A similar lpr-like phenotype was present in RIPK1D324A/D324A FADD−/− RIPK3−/− triple mutant mice, compared to wild type control mice (Fig. 6a). This signature lpr phenotype was comparable between TM mice and DKO mice.

Fig. 6. Analysis of the lymphoid compartments in TM mice.

Representative images of the thymus, lymph nodes, and spleen of 3-month-old mice of the indicated genotypes show that the TM mice develop the signature lpr phenotype, comparable to that in DKO mice, as indicated by lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly (a). The ruler division in mm is shown to the bottom. Wild type control is shown (left). Two color flow cytometry analysis show that the typical CD3+ B220+ T cell population accumulates in the peripheral lymphoid organs in TM and DKO mice, contrasting the wild type control mouse (b). Scatter plots of total number of CD3+B220+ T cells of 3-month-old mice of the indicated genotypes (c). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns not significant. Wild type (WT), double knockout mouse (DKO), and triple mutant (TM) mice are the same as in (a), (b)

Flow cytometric analyses shows that DKO mice contain the unique subset of CD3+ T cells that express the B cell marker B220 (Fig. 6b), a signature phenotype of the Fas−/− lpr mutant mice. Furthermore, these T cells lose the expression of CD4 and CD8 (Supplementary Fig. S3a). When absolute numbers of this peculiar T cell population were determined, DKO and TM mice at ages 3–6 months contain dramatically higher numbers of CD3+B220+ T cells (Fig. 6c). Moreover, the numbers of conventional T cells CD3+B220− T cells and B cells are also significantly increased in the lymph nodes in DKO and TM mice (Supplementary Figs. S3b,c). In young adult mice (6 week old), the thymus, spleen and lymph nodes of RIPK1D324A/D324A FADD−/− RIPK3−/− TM mice were similar in size and weight to that of FADD−/− RIPK3−/− DKO or wild type control mice (Supplementary Fig. S4a). Flow cytometric analysis revealed no obvious defect in the T cell and B cell lineages of TM mice, compared to DKO or wild control mice (Supplementary Figs. S4b, c).

Death receptor signaling in RIPK1D324A/D324A mutant mice

The extrinsic cell death pathways mediated by DRs are essential for immune homeostasis, as indicated by the Fas−/− lpr mouse model. We showed previously that when RIPK1 was absent, thymocytes underwent normal Fas-induced death, but became hypersensitive to TNFα-induced death29. In contrast, RIPK1−/− FADD−/− thymocytes were resistant to TNFα, similar to wild type thymocytes16. In order to determine the status of the DR pathways in TM mice, thymocytes were isolated and treated with various stimuli to initiate extrinsic cell death. Similar to DKO thymocytes, TM thymocytes were highly resistant to cell death responses induced by Fas (Fig. 7a). Unlike hypersensitivity in RIPK1−/− thymocytes16, TM and DKO thymocytes were resistant to TNFα-induced cell death (Fig. 7b). TNFα can also trigger activation of the NFκB pathway and MAPK signaling events in a RIPK1-dependent manner. However, we found that these pathways were not affected in RIPK1D324A/D324A MEFs cells treated with TNFα (Fig. 7b), indicating that the D324A mutation leads to a selective loss of function for RIPK1, essential for mouse embryogenesis. In contrast, loss of the entire RIPK1 protein results in severely impaired activation of NFκB and MAPKs Erk1/2 activation (Fig. 7b, bottom).

Fig. 7. Analysis of the effect of the D324A mutation on DR-induced signaling pathways.

a Thymocytes from mice of indicated genotypes were treated with various doses of anti-Fas antibodies (left) or TNFα (right) for 16 h and cell death was determined by PI uptake measured using a flow cytometer. b MEFs of the indicated genotypes were stimulated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) and induction of phosphorylation of p65 NFκB and Erk1/2 was analyzed by western blotting with the corresponding antibodies. Probing of the same membrane with antibodies for total NFκB or Erk1/2 protein was performed as protein loading/transfer control

Discussion

During embryonic development, RIPK1 can promote necroptosis, which is suppressed by FADD. This regulatory mechanism was demonstrated by our previous data showing that ablation of RIPK1 rescues FADD−/− mice from embryonic lethality16. The resulting FADD−/− RIPK1−/− DKO mice undergo normal embryonic development. The current study aims to understand the mechanism for how RIPK1-mediated necroptosis in embryos is suppressed by FADD, an adaptor for Caspase 8 activation. To this end, we performed gene editing of RIPK1 in mice in an in vivo analysis of a potential mechanism that RIPK1 could be cleaved by Caspase 8 activated through FADD. Our current study reveals novel insight by providing in vivo evidence that besides playing an effector role in necroptosis in embryos, RIPK1 may actually promote apoptosis.

Firstly, mutating the Caspase cleavage site D324 of RIPK1 led to embryonic lethality (Fig. 1). The fact that RIPK1D324A/D324A mutant mice die much earlier than RIPK1−/− null mice, but similar to FADD−/− embryonic death at E12.5 suggests that the D324A mutation rendered RIPK1constitutively active and readily promoted RIPK3-dependent necroptosis. Indeed, severe loss of cells was seen in RIPK1D324A/D324A embryos (Figs. 1b, c), and there was poor ex vivo survival of RIPK1D324A/D324A MEFs (Fig. 2a). Remarkably, deleting one allele of RIPK3 greatly improves RIPK1D324A/D324A MEF growth (Fig. 2b). Deleting both alleles of RIPK3 prolongs embryonic development to E17.5, indicating that RIPK1D324A/D324A embryos die, due in part to RIPK3-mediated necroptosis. However, these embryos do not survive to birth (Fig. 3). This observation was unexpected, especially given that RIPK1−/− or FADD−/− RIPK1−/− embryos undergo full term gestation, and no death occurs until after birth16.

A plausible explanation for this paradoxical observation is that the D324A mutation in RIPK1 skews response to another cell death pathway. To this end, we found elevated CC3 levels present in RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− embryos and TNFα-treated MEFs (Fig. 4), indicating that apoptosis may also occur in RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− embryos. In further support of this notion, we found that RIPK1D324A/D324A RIPK3−/− MEFs were hypersensitized to apoptotic death in responses to treatment with TNFα (Fig. 4b). However, deletion of FADD alone does not provide any improvement on embryogenesis (Fig. 5a). It is only when both FADD and RIPK3 are absent that normal development is ensured in RIPK1D324A/D324A mice (Fig. 5b). This striking observation illustrated the unique power of the new RIPK1D324A/D324A mouse model, which reveals a novel function of RIPK1 in protecting embryos from apoptosis. This newly discovered function of RIPK1 during embryogenesis has not been appreciated using the previously described RIPK1−/−, or FADD−/− RIPK1−/− or FADD−/− RIPK1−/− RIPK3−/− mice. In total, we determined that Caspase cleavage of RIPK1 not only protects against necroptosis, but also RIPK1-dependent apoptosis.

In contrast to the perinatal lethality of FADD−/− RIPK1−/− mice16, FADD−/− RIPK3−/− DKO mice have normal embryonic and postnatal development by blocking not only RIPK3-dependent necroptosis, but also FADD-independent apoptosis19. RIPK1D324A/D324A mice also survive to adulthood when both FADD and RIPK3 are knocked out (Fig. 5). These findings provide an additional platform to determine if caspase cleavage of RIPK1 has a cell death-independent role. To this end, the RIPK1D324A/D324A FADD−/− RIPK3−/− TM and FADD−/− RIPK3−/− DKO mice are comparable to wild type mice at young adult age (Supplementary Fig. S4) and develop progressive lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly, when aged, displaying the lpr-like phenotype (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. S3).

Although RIPK1 is isolated as a Fas-interacting protein, its absence does not impact Fas-induced apoptosis30,31. Instead, RIPK1 deficiency is most often associated with defective NFκB activation induced by TNFR132. Deletion of TNFR1 does not apparently affect mouse development, but RIPK1 deficiency leads to perinatal lethality31. This paradox remained unresolved until recent studies showed that RIPK1−/− mice can survive into late adulthood only when apoptosis is blocked by deletion of FADD or Caspase 8 and necroptosis is blocked by deletion of RIPK319,33–35. This finding implies that RIPK1 suppresses both FADD/Caspase 8-mediated apoptosis and RIPK3-mediated necroptosis at the perinatal stage.

RIPK1 has several putative functional domains, and each has been proposed to play important roles in distinct signaling pathways. Our current study employs a targeted and specific approach to answer a question, untestable through the previous models including RIPK1−/− mice lacking the entire RIPK1 protein. We found that although RIPK1D324A/D324A cells are hypersensitive to both necroptosis and apoptosis induction by TNFα, the Fas-induced cell death pathway was not affected by the D324A mutation in RIPK1 (Fig. 7a). Furthermore, non-cell death pathways induced by TNFα, such as activation of the NFκB and MAPK signaling were also not impacted (Fig. 7b). In particular, our data revealed a novel role for RIPK1 in promoting apoptosis in embryos. Previous in vitro/ex vivo study suggested that RIPK1 cleavage by Caspase 8 facilitate apoptosis in cell lines27. Our current study provides the first direct in vivo evidence that FADD-Caspase 8 disable RIPK1 through cleavage at D324, and as a result, protect embryonic cells against not only necroptosis but also apoptosis. RIPK1-dependent apoptosis induced by TNFα has been previously shown to occur in other settings32,36–42. A more recent study shows that a highly ubiquitinated, insoluble form of RIPK1 is important for apoptotic signaling and identifies new players regulating RIPK1-dependent apoptosis43. Previous studies have shown that the inhibitor cFLIP not only blocks apoptosis, but also necroptosis44. One possibility is that a cFLIP-caspase 8 heterodimmer blocks not only RIPK1-dependent necroptosis17 but also RIPK1-dependent apoptosis via a caspase 8 homodimer. Interestingly, in proximity to D324, S321 can be phosphorylated by MK2, which helps suppress RIPK1-dependent apoptosis and necroptosis, as shown in recent studies45,46. Therefore, several regulatory mechanisms target the intermediate region of RIPK1. The implications of the current study are wide ranging and could be studied in the context of cancer by inducing necroptosis in cancer cells through preventing RIPK1 cleavage or autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, where RIPK1 cleavage could be induced to prevent necroptosis.

Materials and methods

Mice

A previously described strategy28 was employed to generate RIPK1+/D324A founder mice, through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in the C57BL/6 background using the guide RNA 5′-CCTGAATTTGACCTGCTCGGAGG-3′. RIPK3−/− mice were kindly provided by Drs. Kim Newton and Vishva Dixit at Genentech47. FADD+/− mice have been described in our previous studies16,20. All animal studies were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Thomas Jefferson University. Genotyping of RIPK1+/D324A mice was performed using the primers: 5′-AGAATGTTTTCACTGCAGCATGAC-3′ and 5′-GGTACACAGACTCAGACACACATAC-3′ for the endogenous allele; 5′-AATGTTTTCACTGCAGCATGCT-3′ and 5′-GGTACACAGACTCAGACACACATAC-3′ for the D324A mutant allele. RIPK1+/D324A mice were intercrossed and the resulting offspring at various embryonic stages and the weaning age were genotyped by PCR. For embryo analysis, timed mating were set up with RIPK1+/D324A mice in the evening and females were checked in the morning. When vaginal plug was detected, embryos were designated E0.5. Embryos were isolated from pregnant mice at various gestation stages and genotypes were determined by PCR analyses. Genotyping information for additional gene alleles is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Cell culture

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from E10.5 to E12.5 embryos. Embryos of the desired genotypes were placed in 24-well plates with trypsin (0.25%), chopped up with scissors or a scalpel blade. The resulting tissues pieces (1–2 mm3) were further sheared by pipetting up and down several times, and then incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 10 min. The digested embryonic tissues/cells were cultured in DMEM medium containing FBS (10%), L-Glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), and β-mercaptoethanol (100 μM), at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Thymocytes and peripheral T cells were isolated from the spleen and lymph nodes and were cultured in RPMI medium containing FBS (10%), L-Glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), and β-mercaptoethanol (5 μM).

Immunohistochemistry analysis

Embryos were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 2 days, were then washed 2–3 times with PBS and transferred to 70% ethanol, and finally embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or with antibodies specific for activated/cleaved caspase 3 (Cell Signaling Technology #9661).

Flow cytometry

Lymph nodes, spleen and thymus were isolated during mouse dissection. Single cell suspension was prepared and red blood cells were depleted by hypotonic lysis. Cells were stained on ice for 30 min in PBS containing 3% BSA, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.05% sodium azide with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies anti-CD3 (BD Biosciences, clone 17A2), anti-CD4 (BD Biosciences, clone GK1.5), anti-CD8 (Caltag, clone CT-CD8a), anti-B220 (Caltag, clone RA3–6B2). Samples were washed twice with PBS. Data was acquired on LSR II flow cytometric analyzer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar). Total cell numbers were counted on Countess Automated Cell Counter (Invitrogen) and lymphocyte cellularity was determined by multiplying the total cell number of indicated organ by percentage of CD3+ or B220+ cells within the organ obtained by flow cytometry.

Cell death assays

Thymocytes (105/well) were seeded in triplicate in 96-well flat-bottom plates in complete RPMI with various concentrations of anti-Fas antibody (BD Biosciences, clone Jo2) or TNFα. After incubation for 16 h, 1 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI) and the percentage of cell death was analyzed by flow cytometry as determined by PI+ cells.

Western blotting analysis

The presence or absence of FADD, RIPK3, and RIPK1 protein was confirmed by western blotting. Total splenocytes were isolated from mice of the indicated genotypes. MEFs were stimulated with 10 ng/ml TNFα for indicated time points. Cell lysates were prepared in cold RIPA lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM phenylmethyl sulphonyl fluoride, and 1x Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, #78430). Additional inhibitors were added when probing for phospho-specific proteins (50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 10 mM sodium fluoride). Proteins (40 μg) were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Proteins on the membrane were stained with Ponceau S (Sigma-Aldrich, #78376) as a loading/transfer control. Antibodies specific for FADD (generated in house), RIPK3 (ProSci, #2283), RIPK1 (BD Biosciences, #610459), p65 (Cell Signaling, #3034), p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Cell signaling, #9102) were incubated with the membrane overnight at 4 °C followed by streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit (1/10,000,Vector laboratories #PI-1000) or anti-mouse antibodies (1/10,000, Vector laboratories #PI-2000). For analyses of TNF-induced signaling, membranes were blocked with 5% BSA in TBST for 1 h at room temperature and blotted overnight in 5% BSA in TBST containing antibodies specific for phosphorylated forms of p65 NFκB (Cell signaling, #3033S), Erk1/2(p42/44) (Cell signaling, #9106S). Membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h, followed by incubation with Western Lightning Plus-ECL reagent (Perkin Elmer, NEL105001EA). Chemiluminescent signals were detected using X-ray film or with ProteinSimple FluorChem M imaging system (ProteinSimple).

Cell viability and caspase 3/7 activity

MEFs cells were seeded to 24-well plate (105 cells/well). After overnight incubation (about 60% confluence), TNFα (50 ng/ml) and SYTOXTM Green (50 nM, Invitrogen, S34860) and/or Caspase-3/7 red (5 μM, Essen bioscience, #4440) were added and real-time analyses of cell death responses were analyzed an IncuCyte instrument.

Statistical analysis

Data is represented as mean ± Standard error of the mean (SEM). Student’s t-tests were performed using Prism software v7.03 (Graphpad Software, Inc.) to determine p values. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant. Sequence alignment was performed using Geneious Software (Geneious).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Kim Newton and Vishva Dixit for RIPK3−/− mice; Drs. Dan Erkes and Andrew Aplin for IncuCyte analysis help; Dr. Lili Liao, Mohamed Alsabbagh, Sarah Jahfali, and Sonia Ndeupen for technical help; Jennifer Wilson and Mohamed Alsabbagh for critical reading of the manuscript, and the technical staff at the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center for their assistance. Research reported in this publication utilized the Flow Cytometry Facility, Research Animal Facility, and Histopathology Facility at Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Jefferson Health, which was supported by the NCI of the NIH (P30CA056036). Publication made possible in part by support from The Thomas Jefferson University + Philadelphia University Open Access Fund. This study is supported in part by NIH grant 1R01AI119069 to JZ.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z.; Methodology, J.Z., X.Z., J.P.D.; Investigation, X.Z., J.P.D., J.Z.; Writing, Original Draft, J.Z., X.Z., J.P.D.; Writing—Review & Editing, X.Z., J.P.D., J.Z.; Funding Acquisition, J.Z.; Resources, J.Z., X.Z., J.P.D.; Supervision, J.Z.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by S. He

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41419-019-1490-8).

References

- 1.Nagata S. Apoptosis and clearance of apoptotic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2018;36:489–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinlich R, Oberst A, Beere HM, Green DR. Necroptosis in development, inflammation and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;18:127–136. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shan B, Pan H, Najafov A, Yuan J. Necroptosis in development and diseases. Genes Dev. 2018;32:327–340. doi: 10.1101/gad.312561.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dondelinger Y, Hulpiau P, Saeys Y, Bertrand MJM, Vandenabeele P. An evolutionary perspective on the necroptotic pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:721–732. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galluzzi L, et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death & Differ. 2018;25:486–541. doi: 10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holler N, et al. Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1:489–495. doi: 10.1038/82732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Degterev A, et al. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005;1:112–119. doi: 10.1038/nchembio711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho YS, et al. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell. 2009;137:1112–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He S, et al. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell. 2009;137:1100–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang DW, et al. RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science. 2009;325:332–336. doi: 10.1126/science.1172308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun L, et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell. 2012;148:213–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai Z, et al. Plasma membrane translocation of trimerized MLKL protein is required for TNF-induced necroptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:55–65. doi: 10.1038/ncb2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newton K, Manning G. Necroptosis and inflammation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2016;85:743–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagata S, Tanaka M. Programmed cell death and the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017;17:333–340. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vandenabeele P, Declercq W, Van Herreweghe F, Vanden Berghe T. The role of the kinases RIP1 and RIP3 in TNF-induced necrosis. Sci. Signal. 2010;3:re4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3115re4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H, et al. Functional complementation between FADD and RIP1 in embryos and lymphocytes. Nature. 2011;471:373–376. doi: 10.1038/nature09878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oberst A, et al. Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIP(L) complex inhibits RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature. 2011;471:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature09852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaiser WJ, et al. RIP3 mediates the embryonic lethality of caspase-8-deficient mice. Nature. 2011;471:368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature09857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dowling, J. P., Nair, A., Zhang, J. A novel function of RIP1 in postnatal development and immune homeostasis by protecting against RIP3-dependent necroptosis and FADD-mediated apoptosis. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 3, 12 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Zhang J, Cado D, Chen A, Kabra NH, Winoto A. Fas-mediated apoptosis and activation-induced T-cell proliferation are defective in mice lacking FADD/Mort1. Nature. 1998;392:296–300. doi: 10.1038/32681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeh WC, et al. FADD: essential for embryo development and signaling from some, but not all, inducers of apoptosis. Science. 1998;279:1954–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5358.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varfolomeev EE, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse caspase 8 gene ablates cell death induction by the TNF receptors, Fas/Apo1, and DR3 and is lethal prenatally. Immunity. 1998;9:267–276. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80609-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ch’en IL, Tsau JS, Molkentin JD, Komatsu M, Hedrick SM. Mechanisms of necroptosis in T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:633–641. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu, J. V., et al. Complementary roles of Fas-associated death domain (FADD) and receptor interacting protein kinase-3 (RIPK3) in T-cell homeostasis and antiviral immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 15312–15317 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Wallach D, Kang TB, Kovalenko A. Concepts of tissue injury and cell death in inflammation: a historical perspective. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:51–59. doi: 10.1038/nri3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanden Berghe T, Linkermann A, Jouan-Lanhouet S, Walczak H, Vandenabeele P. Regulated necrosis: the expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:135–147. doi: 10.1038/nrm3737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Y, Devin A, Rodriguez Y, Liu ZG. Cleavage of the death domain kinase RIP by caspase-8 prompts TNF-induced apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2514–2526. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paquet D, et al. Efficient introduction of specific homozygous and heterozygous mutations using CRISPR/Cas9. Nature. 2016;533:125. doi: 10.1038/nature17664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dowling, J. P., Cai, Y., Bertin, J., Gough, P. J., Zhang, J. Kinase-independent function of RIP1, critical for mature T-cell survival and proliferation. Cell Death Dis.7(9), e2379 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Ting AT, Pimentel-Muinos FX, Seed B. RIP mediates tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 activation of NF-kB but not Fas/APO-1-intitiated apoptosis. EMBO J. 1996;15:6189–6196. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb01007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelliher MA, et al. The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-kB signal. Immunity. 1998;8:297–303. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80535-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ting AT, Bertrand MJM. More to Llfe than NF-κB in TNFR1 signaling. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:535–545. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rickard James A, et al. RIPK1 regulates RIPK3-MLKL-driven systemic inflammation and emergency hematopoiesis. Cell. 2014;157:1175–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dillon Christopher P, et al. RIPK1 blocks early postnatal lethality mediated by caspase-8 and RIPK3. Cell. 2014;157:1189–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaiser WJ, et al. RIP1 suppresses innate immune necrotic as well as apoptotic cell death during mammalian parturition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:7753–7758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401857111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Du F, Wang X. TNF-alpha induces two distinct caspase-8 activation pathways. Cell. 2008;133:693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tenev, T. et al. The ripoptosome, a signaling platform that assembles in response to genotoxic stress and loss of IAPs. Mol. Cell43, 432–448 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Feoktistova, M. et al. CIAPs block ripoptosome formation, a RIP1/caspase-8 containing intracellular cell death complex differentially regulated by cFLIP isoforms. Mol. Cell43, 449–463 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Çöl Arslan S, Scheidereit C. The prevalence of TNFα-induced necrosis over apoptosis is determined by TAK1-RIP1 interplay. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Donnell MA, Hase H, Legarda D, Ting AT. NEMO inhibits programmed necrosis in an NFkappaB-independent manner by restraining RIP1. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vlantis K, et al. NEMO prevents RIP kinase 1-mediated epithelial cell death and chronic intestinal inflammation by NF-kappaB-dependent and independent functions. Immunity. 2016;44:553–567. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kondylis V, et al. NEMO prevents steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting RIPK1 kinase activity-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:582–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amin P, et al. Regulation of a distinct activated RIPK1 intermediate bridging complex I and complex II in TNFα-mediated apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018;115:E5944–E5953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1806973115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dillon CP, et al. Survival function of the FADD-CASPASE-8-cFLIP(L) complex. Cell Rep. 2012;1:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaco I, et al. MK2 phosphorylates RIPK1 to prevent TNF-induced cell death. Mol. Cell. 2017;66:698–710 e695. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Menon MB, et al. p38(MAPK)/MK2-dependent phosphorylation controls cytotoxic RIPK1 signalling in inflammation and infection. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017;19:1248–1259. doi: 10.1038/ncb3614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newton K, Sun X, Dixit VM. Kinase RIP3 is dispensable for normal NF-kappa Bs, signaling by the B-cell and T-cell receptors, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:1464–1469. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1464-1469.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.