Abstract

Neuroendocrine-type ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels are metabolite sensors coupling membrane potential with metabolism, thereby linking insulin secretion to plasma glucose levels. They are octameric complexes, (SUR1/Kir6.2)4, comprising sulfonylurea receptor 1 (SUR1 or ABCC8) and a K+-selective inward rectifier (Kir6.2 or KCNJ11). Interactions between nucleotide-, agonist-, and antagonist-binding sites affect channel activity allosterically. Although it is hypothesized that opening these channels requires SUR1-mediated MgATP hydrolysis, we show here that ATP binding to SUR1, without hydrolysis, opens channels when nucleotide antagonism on Kir6.2 is minimized and SUR1 mutants with increased ATP affinities are used. We found that ATP binding is sufficient to switch SUR1 alone between inward- or outward-facing conformations with low or high dissociation constant, KD, values for the conformation-sensitive channel antagonist [3H]glibenclamide ([3H]GBM), indicating that ATP can act as a pure agonist. Assembly with Kir6.2 reduced SUR1's KD for [3H]GBM. This reduction required the Kir N terminus (KNtp), consistent with KNtp occupying a “transport cavity,” thus positioning it to link ATP-induced SUR1 conformational changes to channel gating. Moreover, ATP/GBM site coupling was constrained in WT SUR1/WT Kir6.2 channels; ATP-bound channels had a lower KD for [3H]GBM than ATP-bound SUR1. This constraint was largely eliminated by the Q1179R neonatal diabetes-associated mutation in helix 15, suggesting that a “swapped” helix pair, 15 and 16, is part of a structural pathway connecting the ATP/GBM sites. Our results suggest that ATP binding to SUR1 biases KATP channels toward open states, consistent with SUR1 variants with lower KD values causing neonatal diabetes, whereas increased KD values cause congenital hyperinsulinism.

Keywords: ATP-binding cassette transporter subfamily C member 8 (ABCC8), ABC transporter, allosteric regulation, diabetes, ion channel, ATP-sensitive potassium channel, glibenclamide, hyperinsulinism, KCNJ11 (Kir6.2), neonatal diabetes, KATP channel, SUR1, congenital hyperinsulinism, metabolic sensor

Introduction

Neuroendocrine-type ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP)2 channels comprise an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) protein (1), ABCC8/SUR1, and a K+-selective inward rectifier (2), KCNJ11/Kir6.2, assembled as heterooctamers (3–5), (SUR1/Kir6.2)4. In pancreatic β-cells, these channels are metabolite sensors that couple cellular metabolism with membrane electrical activity to link insulin secretion with blood glucose levels. This coupling is critical for normal physiology; loss of channel function is a cause of congenital hyperinsulinism (Ref. 6; for reviews, see Refs. 7 and 8), whereas gain-of-function mutations in Kir6.2 (9) and SUR1 (10) cause neonatal diabetes (ND) (for reviews, see Refs. 11 and 12). Gain of function is one cause of mature-onset diabetes of the young (13), whereas a ABCC8/SUR1 polymorphism, the Ala amino acid allele at p.A1369S, is associated with an increased risk for type 2 diabetes (14).

Channel activity is regulated positively by ATP and ADP binding to SUR1 and negatively by nucleotide binding to Kir6.2 (15–20). Additionally, multiple metabolites, including phosphoinositides (21–23) and long-chain acyl-CoA esters (24–26), and phosphorylation (27–29) positively modulate channel activity. Pharmacologic modulation of SUR1 by channel antagonists, sulfonylureas like glibenclamide (GBM) and glinides like repaglinide (30–36), and by agonists like diazoxide (Refs. 31 and 37–39; for a review, see Ref. 40) is clinically important. These physiologic and pharmacologic modulators all affect channel gating via allosteric interactions in the sense that their binding sites on SUR1 are coupled to and known to be physically distinct from one another based on structural studies (41, 42). The available data are consistent with the idea that SUR1 exists in multiple conformations differing in affinity for ligands and ability to activate channel openings.

How nucleotides regulate KATP channels remains an open question. Early electrophysiological studies (15) showed that although ATP inhibited activity, MgADP, acting through SUR1, activated channel openings (16–18, 20). The finding that SUR1 was in the ABC protein family (1), whose members are ATPases that use the energy of ATP binding and hydrolysis to transport substrates across membranes (43–45), suggested that ATP hydrolysis on SUR1 might generate a conformation that activated channel openings. The idea that a “posthydrolytic,” MgADP-bound conformation of SUR1, generated as part of an ABC enzymatic cycle, uniquely activates channel openings was most concisely described by Zingman et al. (46, 47) and Bienengraeber et al. (48) and reviewed in Zingman et al. (49). The idea was supported by experiments with nonhydrolyzable analogs, e.g. AMPPNP, AMPPCP, and ATPγS, and by reports that the action of potassium channel agonists, e.g. diazoxide for SUR1-based channels and a pinacidil analog, P1075, for related SUR2-based channels, required ATP hydrolysis to reach an activating state (50–52).

The need for hydrolysis was questioned by Choi et al. (53), who failed to find the changes in microscopic reversibility and detailed balance expected for strong coupling, and by Ortiz et al. (54, 55), who used [3H]GBM to show that ATP binding was enough to switch SUR1, in the absence of Kir6.2, between conformations with high and low affinities for the ligand. In other ABC proteins, ATP binding to the nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs) results in NBD dimerization and a reconfiguration of the transmembrane helical domains (TMDs) from “inward- to outward-facing” states. Thus, Ortiz et al. (54) proposed that outward-facing, ATP-bound conformations of SUR1 with lowest affinity for [3H]GBM and highest affinity for the agonist diazoxide would activate channel openings without the need for hydrolysis. We tested this proposal here using KATP channels whose Kir6.2 pores are not inhibited by ATP.

In other ABC proteins, hydrolysis of ATP is essential to “reset” the transporter conformation and allow cyclic substrate transport, but the function of the low rate of hydrolysis reported for SUR1 is not yet clear (56, 57). Despite its structural relation to other ABC transporters, SUR1 is usually assumed to be a “regulatory protein,” not a transporter. However, the localization of GBM bound in the central cavity of SUR1 by cryo-EM (41, 42) together with earlier studies aimed at defining the GBM-binding site and defining the role(s) of the N terminus, KNtp, of Kir6.2 in GBM binding and channel gating (for a review, see Ref. 40) suggests that the transport idea deserves revisiting. The implication is that SUR1 is a “cryptic,” albeit frustrated, peptide transporter whose “substrate” is KNtp. This idea suggests that evolution has linked two fundamental transport mechanisms, ATP-driven substrate transport and ion transport, to couple cellular metabolism with membrane potential, thus effectively marrying the transport functionality of an ATP-binding cassette protein, ABCC8/SUR1, with the regulation of gating of an ion channel, Kir6.2/KCNJ11. Clearly, SUR1 cannot fully “transport” Kir6.2, but the idea implies a mechanism by which ATP-driven changes in SUR1 can couple directly to the pore by moving KNtp.

We have focused on ATP-driven conformational changes in SUR1, including testing the need for ATP hydrolysis to activate channel openings and defining the properties of different SUR1 conformations. We show that when the inhibitory action of ATP on the Kir6.2 pore is eliminated, ATP4− acts as a classic channel agonist even when potential nucleotide hydrolysis is minimized by limiting Mg2+ and/or by substitution of glutamine for the catalytic glutamate, SUR1E1507Q, needed for hydrolysis. We confirm that outward-facing conformations of SUR1 alone, i.e. without Kir6.2, have reduced affinity for [3H]GBM and show that assembly with full-length Kir6.2 increases the affinity and attenuates the negative allosteric effect of ATP on GBM interactions (58). One ND mutation, SUR1Q1179R, in transmembrane helix 15 near the GBM-binding site markedly increases coupling between the GBM and ATP sites. This suggests that helix 15 and helix 16, which cross over from TMD2 to contact NBD1, are part of a structural pathway or network connecting these sites. MgADP, like MgATP, efficiently switches the conformation of SUR1 alone but has no significant effect on [3H]GBM binding to wildtype (WT) SUR1 in channels. The results support the hypothesis that ATP acts as an agonist by switching SUR1 from inactive inward-facing to active outward-facing conformations that bias channels toward open states.

Results

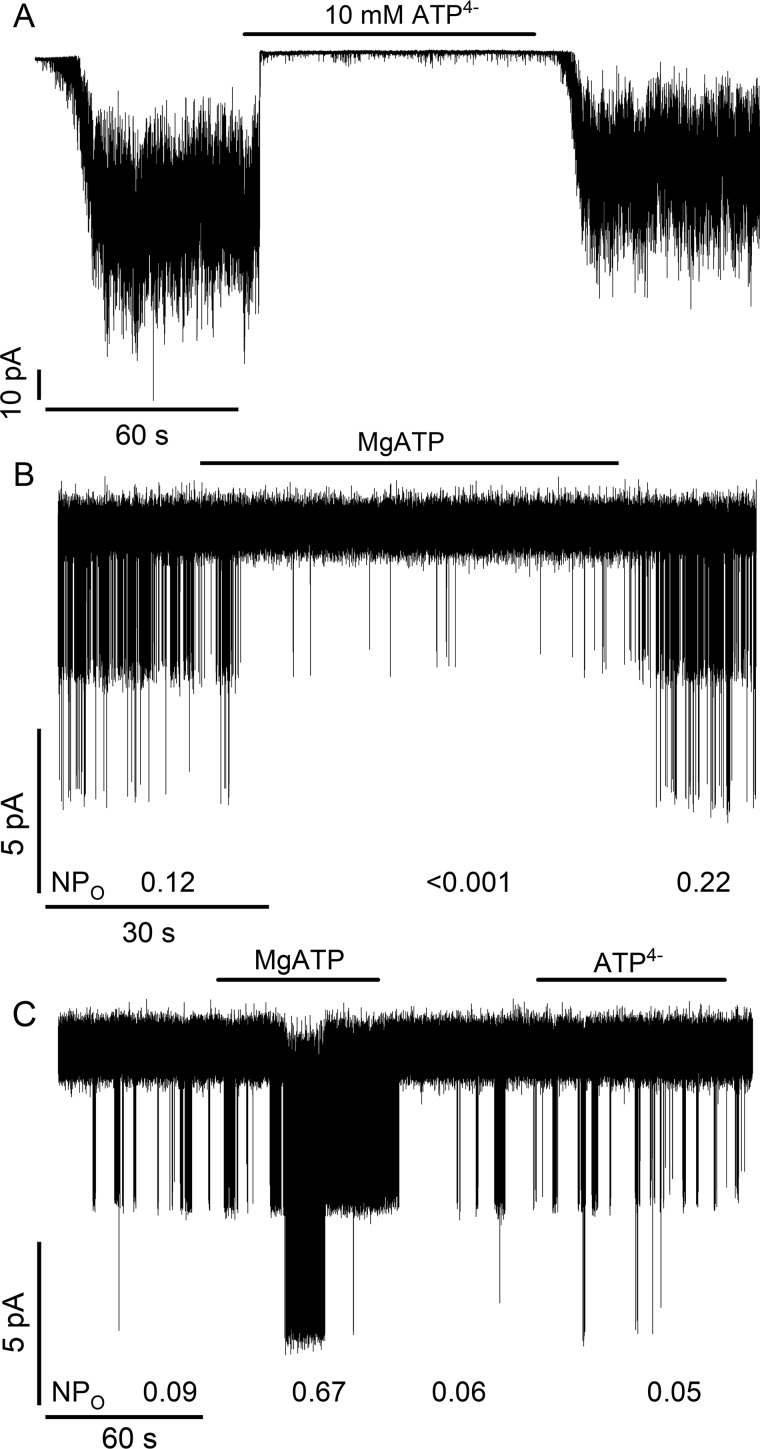

ATP activation of SUR1/Kir6.2G334D KATP channels

To test whether ATP can act directly as a channel agonist, the inhibitory action of ATP binding to the Kir6.2 pore was minimized by coexpressing SUR1 with a mutant pore subunit, Kir6.2G334D. This substitution, identified in cases of neonatal diabetes (59), reduces the affinity of Kir6.2 for inhibitory ATP, thus minimizing ATP antagonism (60–62). Fig. 1, A and B, confirm that ATP4− (10 mm) or MgATP (1 mm) reduce the activity of WT SUR1/WT Kir6.2 channels. In contrast, MgATP acts as an agonist on WT SUR1/Kir6.2G334D channels, increasing the product of the open probability (Po) and number (N) of open channels, NPo, 7–8-fold (Fig. 1C). The different nucleotide concentrations were chosen because SUR1 has a significantly lower KD for MgATP versus ATP4− as determined by their respective abilities to stabilize conformations that bind GBM more weakly (54, 55). WT Kir6.2 has estimated KD values of ∼5–20 μm (19, 63, 64) for inhibitory ATP (±Mg2+) and should be nearly saturated in either case. The agonist action is reversible: after washout of MgATP, channel activity rapidly returns to basal levels. The application of ATP4− (10 mm) had no significant effect on channel open probability.

Figure 1.

Assay for the action of nucleotides on KATP channels. ATP4− (10 mm), without Mg2+ (A), or MgATP (1 mm) (B) inhibits WT SUR1/WT Kir6.2 channels. C, WT SUR1/Kir6.2G334D channels, where the G334D mutant Kir6.2 subunit has a low affinity for adenine nucleotides, are activated by MgATP (1 mm) but not significantly affected by ATP4− (10 mm). In B and C, the NPo values (Current = Number of open channels × Channel open probability) were estimated over 20–45-s intervals before, during, or after the application of nucleotides.

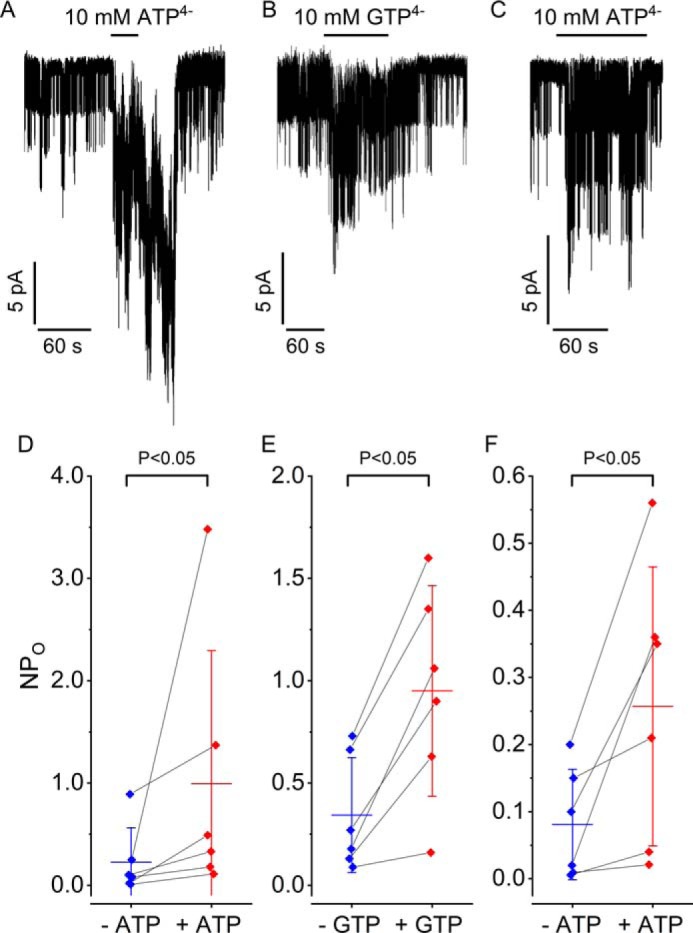

ATP4− activation of SUR1Q1179R/Kir6.2G334D KATP channels

Several ND SUR1 mutant receptors, including SUR1Q1179R, have lower KD values for nucleotides based on the allosteric effect(s) of ATP4− or MgATP on [3H]GBM binding (54, 55, 65). SUR1Q1179R/Kir6.2G334D channels were used to determine whether nucleotide binding, without the Mg2+ cofactor needed for ATP hydrolysis (56), was enough to activate channel openings. Fig. 2, A and D, show that the NPo of spontaneously active SUR1Q1179R/Kir6.2G334D channels is increased significantly by ATP4− (10 mm), consistent with nucleotide binding being enough to stabilize conformations of SUR1 that activate channel openings. Together with Fig. 1C, the results show that, in the absence of antagonism at Kir6.2, MgATP and more importantly ATP4− are channel agonists, albeit agonists with markedly different KD values.

Figure 2.

ATP4− (10 mm) and GTP4− (10 mm) activate KATP channels with ND mutations in SUR1 that have a lower KD for ATP. A and B, activation of SUR1Q1179R/Kir6.2G334D channels by ATP4− or GTP4−. D and E, summary of the results from 12 experiments on SUR1Q1179R/Kir6.2G334D channels. The activation of SUR1E1507Q/Kir6.2G334D channels by ATP4− (C) and a summary of results from seven experiments on SUR1E1507Q/Kir6.2G334D channels (F) are shown. Red and blue error bars are the means ± S.D. Significance was determined using the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

GTP4− activation of SUR1Q1179R/Kir6.2G334D KATP channels

We tested whether GTP4−, without Mg2+, was enough to activate SUR1Q1179R/Kir6.2G334D channels. Fig. 2, B and E, show that GTP4− (10 mm), like ATP4−, significantly increases channel activity. The results suggest that a lower KD for nucleotides may underlie the increased activation of the SUR1A1369 variant associated with type 2 diabetes risk (14) rather than the proposed altered rate of ATP hydrolysis (66, 67).

ATP4− activation of SUR1E1507Q/Kir6.2G334D KATP channels

To test further whether nucleotide binding is sufficient to select and stabilize SUR1-activating conformers, a glutamine was substituted for the “catalytic” glutamate in NBD2. This substitution strongly reduces ATPase and transport activity in related proteins (68, 69), and Glu → Gln substitutions have been used to trap ATP-bound conformations for structural studies (70–72). Fig. 2, C and F, show that SUR1E1507Q/Kir6.2G334D channels, lacking the catalytic glutamate and Mg2+, are significantly activated by ATP4−. The results imply that ATP4− and GTP4− are channel agonists whose binding energies are enough to shift the population of SUR1 conformers toward those that increase channel openings.

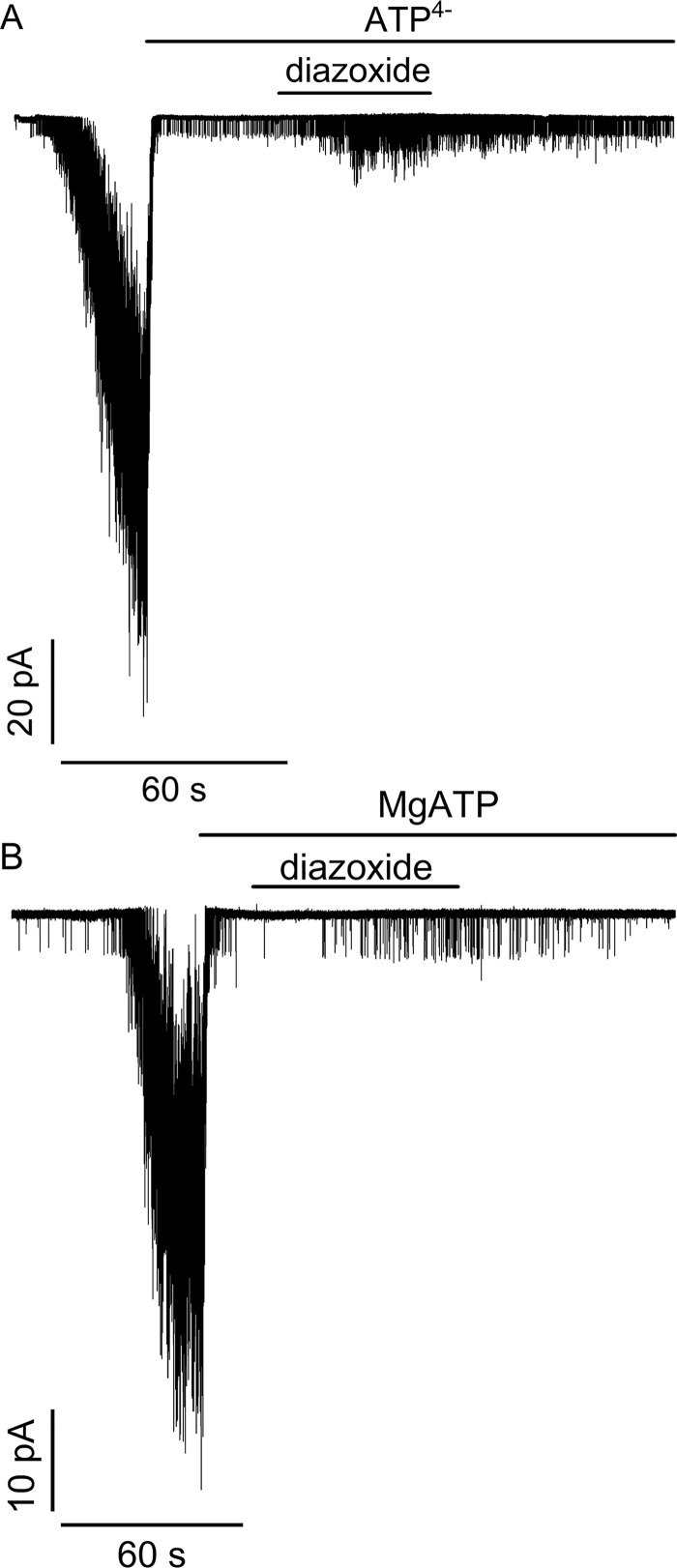

ATP4− supports the action of KATP channel agonists

To assess whether ATP binding is sufficient to support the action of channel openers, the ability of diazoxide to activate SUR1E1507K/WT Kir6.2 channels was tested. The SUR1E1507K mutation was used because congenital hyperinsulinism patients with this Glu → Lys mutation respond to diazoxide (73), and, without the catalytic glutamate, SUR1E1507K/WT Kir6.2 channels are expected to have impaired ATP hydrolysis. Fig. 3A shows that when patches from cells expressing SUR1E1507K/WT Kir6.2 channels are pulled into nucleotide-free medium, channels are activated as nucleotide antagonism on their WT pores is reduced. Application of ATP4− rapidly inhibits channel activity as expected, but coapplication of diazoxide shows that ATP4− does support its agonist action. Fig. 3B confirms that MgATP inhibits channel activity and supports the action of diazoxide as expected from patient responses. The response to diazoxide is consistent with the positive allosteric coupling between channel opener and nucleotide-binding sites seen with SUR1 alone where diazoxide stabilizes nucleotide-bound conformations (55).

Figure 3.

Activation of SUR1E1507K/WT Kir6.2 channels associated with congenital hyperinsulinism by the agonist diazoxide. At the arrows, patches were pulled into nucleotide-free medium, which activates a large number of channels as inhibitory nucleotides leave the pore. Application of ATP4− (10 mm) (A) or MgATP (1 mm) (B) rapidly inhibits channel activity. Concurrent application of diazoxide (340 μm) increases channel activity in both cases. Activation was observed in five of five trials for ATP4− and for MgATP.

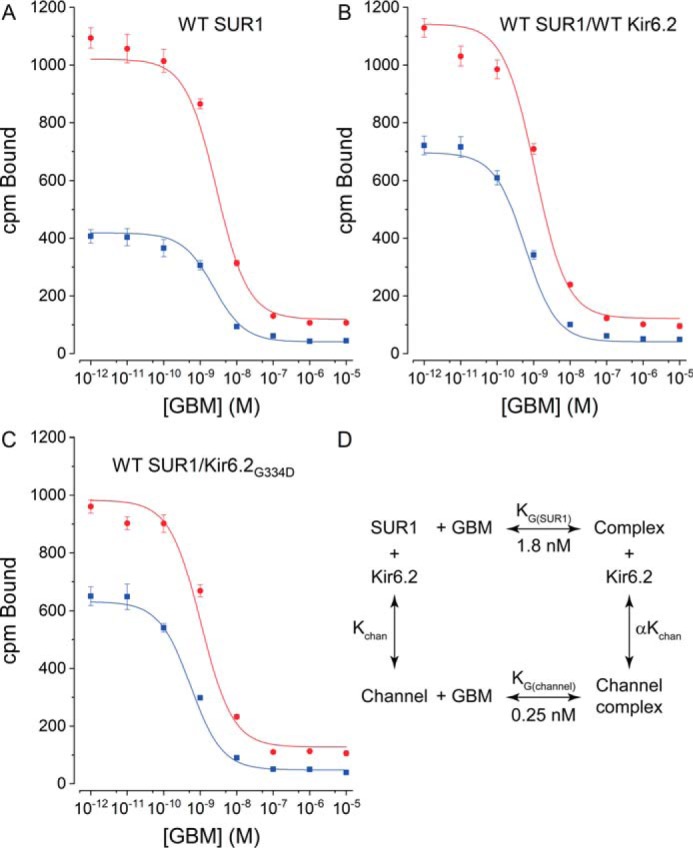

Assembly with Kir6.2 lowers the dissociation constant, KG, of SUR1 for GBM

We asked how assembly with Kir6.2 affects the GBM-binding site and the intramolecular linkage between the ATP- and GBM-binding sites within the receptor. The dissociation constant, KG, values for [3H]GBM binding to receptors and channels are needed to assess the impact of adding nucleotides; thus, KG values were determined from homologous competition experiments where [3H]GBM binding is competed by increasing concentrations of unlabeled GBM. KG values were obtained by simultaneously fitting a homologous competition model (74) using data at two concentrations of [3H]GBM (see “Experimental procedures”). The approach is illustrated in Fig. 4, A–C, for the WT receptor alone or coexpressed with Kir6.2 or Kir6.2G334D. The results extend earlier studies in isolated membranes (75) and live cells (76) showing that KATP channels bind [3H]GBM more tightly than SUR1 alone. Our binding assays were done without Mg2+ and ATP, conditions where cryo-EM studies show SUR1 in inward-facing conformations with GBM bound and a closed Kir6.2 pore (77, 78). Under these conditions, WT channels have approximately a 7.2-fold lower KG for GBM. Table 1 summarizes the data for four receptors and corresponding channels, including WT, one congenital hyperinsulinism (SUR1E1507K), and two neonatal diabetes ABCC8/SUR1 mutations (SUR1E1507Q and SUR1Q1179R). In all four cases, the KG values for channels are significantly lower than for SUR1 alone. There was no significant difference in KG values between channels assembled with WT Kir6.2 versus Kir6.2G334D. An average value for the increased stability of GBM–WT SUR1/Kir6.2 versus GBM–WT SUR1 complexes was estimated from the difference in free energies, ΔΔG = −1.2 ± 0.1 kcal/mol (mean ± S.E., n = 9), derived from the respective dissociation constants. The average ΔΔG value, −0.8 kcal/mol, for all the WT and mutant channels is somewhat lower. The structural changes underlying the increased stability of GBM–channel complexes are not well defined, but previous studies implicate the N terminus of Kir6.2, KNtp, as a major factor in the higher affinity of SUR1/Kir6.2 channels versus SUR1 for GBM (Refs. 75 and 76 and “Discussion”).

Figure 4.

Assembly with Kir6.2 increases the affinity of SUR1 for [3H]GBM. A–C, dissociation constants, KG values, for [3H]GBM were determined by displacement of 0.3 (blue) or 1 (red) nm [3H]GBM by unlabeled GBM. Plots are for WT SUR1 alone, WT SUR1/WT Kir6.2, and WT SUR1/Kir6.2G334D, respectively. The data are presented as the mean values (error bars are ±S.E., n = 9) of the total bound radioactivity. The radioactivity remaining at the foot of the binding curves shows nonspecific binding, which increases with higher [3H]GBM concentrations. The curves are global best fits to a homologous displacement model with radioligand depletion (74). Table 1 gives a summary of KG values for WT and mutant SUR1s and corresponding channels. D, the thermodynamic cycle used to estimate GBM stabilization of KATP channels. Binding assays were done in the absence of ATP and Mg2+ with 1 mm EDTA added.

Table 1.

Summary of dissociation constants (KG)

CI values are lower and upper 95% confidence intervals. p values were determined using one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's test for multiple comparisons.

| Sample | Mean | CI lower– upper | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| nm | |||

| WT SUR1 alone | 1.8 | 1.4–2.2 | |

| WT SUR1/WT Kir6.2 | 0.25 | 0.2–0.3 | <0.001 |

| WT SUR1/Kir6.2G334D | 0.4 | 0.3–0.5 | <0.001 |

| SUR1Q1179R | 3.9 | 3.2–4.8 | |

| SUR1Q1179R/WT Kir6.2 | 1.1 | 0.7–1.6 | <0.001 |

| SUR1Q1179R/WT Kir6.2G334D | 1.1 | 0.8–1.5 | <0.001 |

| SUR1E1507K | 1.7 | 1.4–2.0 | |

| SUR1E1507K/WT Kir6.2 | 0.6 | 0.5–0.9 | <0.001 |

| SUR1E1507Q | 0.8 | 0.4–1.5 | |

| SUR1E1507Q/Kir6.2 | 0.3 | 0.2–0.5 | <0.01 |

Consistent with our earlier results (54, 55) and cryo-EM structures (41, 42, 77, 78), the high affinity of GBM binding strongly selects and stabilizes inward-facing conformations of SUR1 with a ΔG0 value of approximately −12.4 or −13.6 kcal/mol for receptors or channels, respectively. The difference in binding energies of SUR1 versus SUR1/Kir6.2 reflects an increased stability of GBM-bound versus unliganded channels. We used the thermodynamic cycle shown in Fig. 4D to estimate the increased stability. We assumed channels and subunits are in equilibrium and that GBM interacts with different energies with SUR1 alone versus SUR1 in channels (data are summarized in Table 1). The products of the dissociation constants along the two branches forming GBM–channel complexes must be equal. Kchan, the dissociation constant for channels into subunits, is not known but must be low because channels are stable and complexes can be isolated (41, 42, 57, 77–79). The KG values for WT receptors versus channels gave an estimated value for α of ∼0.14, indicating channels complexed with GBM are ∼7 times more stable than unliganded KATP channels. The average stabilization, for all channels versus receptors, is ∼4-fold based on the average ΔΔG value.

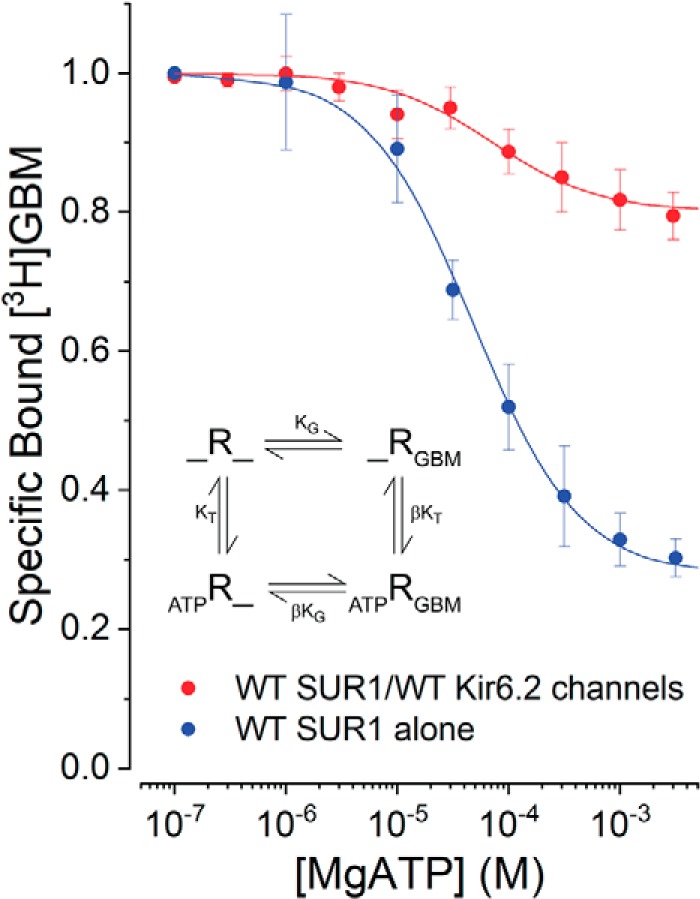

Assembly with Kir6.2 alters the allosteric coupling between the GBM and ATP-binding sites in WT SUR1

Table 1 shows that assembly with Kir6.2 alters the SUR1 GBM-binding site, increasing its affinity for GBM. The KG values were used to assess how channel assembly alters the negative allosteric coupling between GBM- and ATP-binding sites. The effects of increasing concentrations of MgATP on the binding of fixed concentrations of [3H]GBM were compared for SUR1 alone or SUR1/Kir6.2 channels. The GBM- and ATP-binding sites are physically distinct; thus, a reduction in bound [3H]GBM indicates negative allosteric coupling between these two binding sites. Fig. 5 shows stronger negative coupling for SUR1 alone than for SUR1/Kir6.2 channels. In both cases, a significant fraction of bound [3H]GBM remains at the highest, saturating concentrations of MgATP, but the fraction remaining is significantly lower for SUR1 alone; assembly with Kir6.2 markedly attenuates the ability of nucleotides to reduce [3H]GBM binding to SUR1/Kir6.2 channels versus SUR1 alone (58). Our previously described ternary complex model (54), shown in Fig. 5, inset, was used to interpret the data. In this model, the receptor (R) is presumed to have coupled GBM- and ATP-binding sites. The coupling factor, β, is a measure of the interaction between sites; β = 1 equates to no coupling, whereas β > 1 reflects an increase in the KD for the binding of one ligand when the opposite ligand-binding site is occupied. In this model, the fraction of bound [3H]GBM remaining at saturating concentrations of nucleotide reflects the higher KD (=βKG), i.e. a reduced affinity, of MgATP-bound SUR1 for [3H]GBM.

Figure 5.

Association with Kir6.2 affects the allosteric properties of WT SUR1. Increasing MgATP reduces the binding of [3H]GBM (1 nm). The data are given as specific bound [3H]GBM defined as [3H]GBM bound in the presence of MgATP divided by the radioactivity bound without nucleotide. The inset shows the four-state ternary complex model. R is defined as SUR1 with ATP bound to NBD1, the noncanonical nucleotide-binding site. ATP can induce NBD dimerization by binding to NBD2 with or without bound GBM. The KG values from Fig. 4, estimated in the absence of ATP, were used to estimate β and KT. The curves were generated using the global-fit parameters in Table 2; data are means with error bars indicating ±S.E., n = 6.

The parameters KT, the dissociation constant for ATP, and β, the allosteric constant, were estimated in two ways using Equation 1 given under “Experimental procedures.” In both cases, the individual KG values were fixed (parameters in Table 2). In one case, the two data sets were fit simultaneously (globally). This assumes the KT for ATP-binding is the same for both SUR1 and channels and yields a single KT value and best-fit estimates of β for SUR1 alone versus channels. In the alternative case, KT and β were estimated independently for each data set. The two estimates are nearly identical (Table 2). The curves in Fig. 5 were generated using the global parameters, but curves generated using the independent parameters are visually the same. In this four-state model, the fraction of bound [3H]GBM for SUR1 alone reflects the ∼5-fold lower affinity of SUR1-MgATP–bound complexes for [3H]GBM. The data in Table 1 show that channels have ∼7-fold higher affinity for [3H]GBM, which is reflected in the larger fraction of bound [3H]GBM seen in ATP-bound SUR1/Kir6.2 channels. It is worth noting that this negative allosteric effect is reciprocal; GBM–SUR1, alone or in channels, binds MgATP more weakly (compare KT versus βKT values in Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of binding parameters from Fig. 5

Data are given as mean values and 95% confidence intervals (lower–upper values).

| Species | KG | β | KT | βKG | βKT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | μm | nm | μm | ||

| Global fits | |||||

| SUR1 | 1.8 (1.5–2.2) | 5.0 (4.5–5.6) | 34.1 (29.6–40.4) | ∼9 | ∼170 |

| SUR1/Kir6.2 | 0.25 (0.19–0.32) | 2.2 (2.0–2.4) | 34.1 (29.6–40.4) | ∼0.6 | ∼75 |

| Independent fits | |||||

| SUR1 | 1.8 (1.5–2.2) | 5.0 (4.5–5.6) | 34.4 (27.7–42.6) | ∼9 | ∼170 |

| SUR1/Kir6.2 | 0.25 (0.19–0.32) | 2.2 (2.0–2.4) | 39.4 (22.3–69.7) | ∼0.6 | ∼86 |

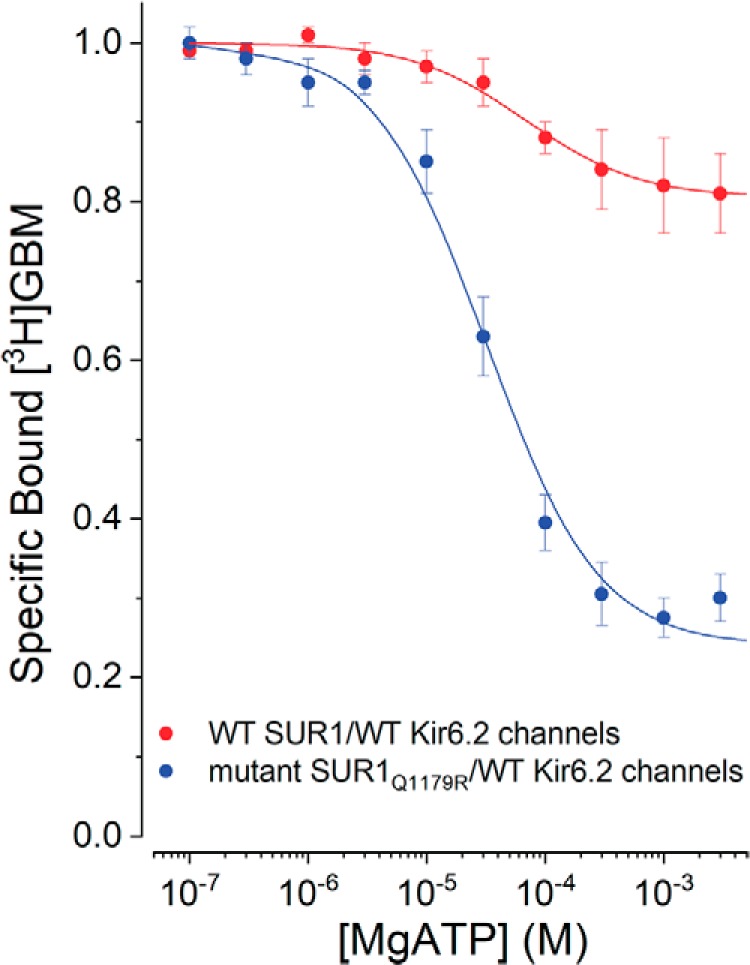

SUR1Q1179R, an ABCC8 neonatal diabetes mutation, affects allosteric coupling

Assembly with Kir6.2 markedly affects the coupling between the ATP and GBM sites in WT SUR1 (Fig. 5), but there are no informative data available on the structural pathway(s) or amino acid network(s) linking these sites. Analyses of coupling in ABCC8/SUR1 mutants provides one approach to identify amino acids in potential pathways. We tested whether the Gln → Arg substitution, SUR1Q1179R, might affect coupling. Position 1179 is near the top of helix 15, within 20 nm of the GBM-binding site (41). Helices 15 and 16 are the pair of helices from TMD2 that cross over to interact with NBD1. Intuitively, this “swapped” pair of helices is a potential pathway or link between the ATP- and GBM-binding sites. Fig. 6 compares the reduction of bound [3H]GBM by MgATP from WT SUR1/WT Kir6.2 versus ND mutant SUR1Q1179R/WT Kir6.2 channels. The Gln → Arg substitution largely reverses the constraint imposed by assembly with Kir6.2 (Fig. 5). In this experiment, the WT control data set includes the channel data shown in Fig. 5. The curves are based on fits to the ternary complex model (Fig. 5, inset) with values for WT channels of KG = 0.25 (0.19–0.32) nm, β = 2.2 (2.1–2.3), and KT = 38 (27.1–53.6) μm and for the SUR1Q1179R/wtKir6.2 channels of KG = 1.1 (3.2–4.8) nm, β = 7.3 (6.3–8.6), and KT = 18 (14.9–21.9) μm. Values are given as means with 95% confidence intervals (lower-upper values).

Figure 6.

Effect of the SUR1Q1179R ND mutation on allosteric coupling in KATP channels. Increasing MgATP reduces bound [3H]GBM (1 nm). Curves are the best fits of the ternary complex model (Fig. 5, inset) to the data. The KG values from Table 1 were used to estimate β and KT. The best-fit parameters are given in the text. Points are means with error bars indicating ±S.E., n = 6. The WT SUR1Q1179/Kir6.2 channel values include those shown in Fig. 5.

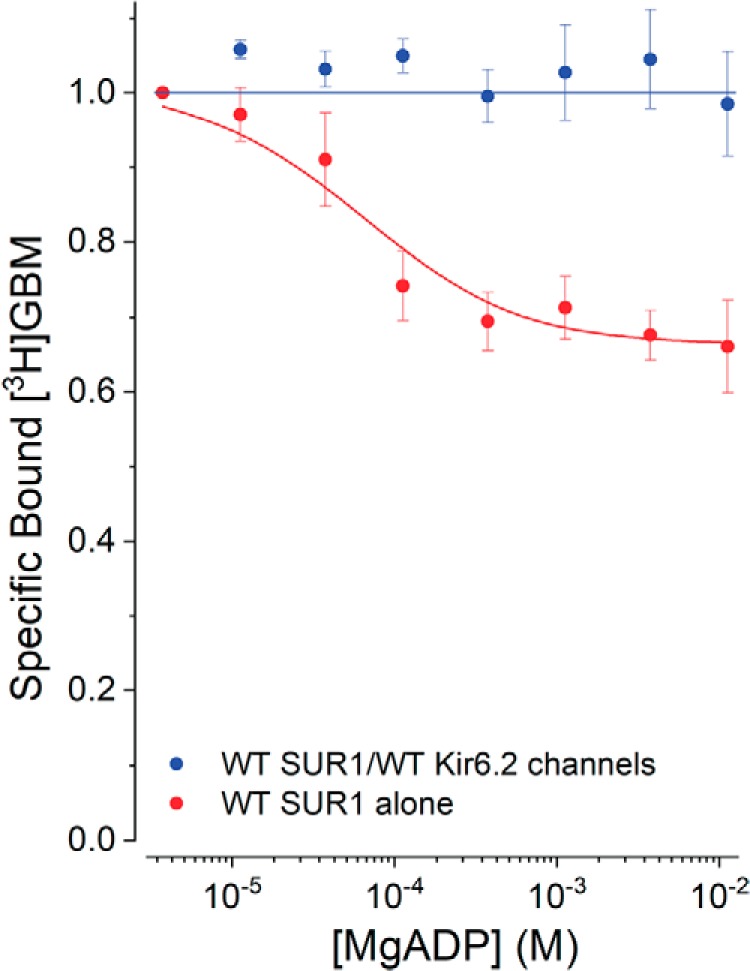

Effects of MgADP on SUR1 versus SUR1/Kir6.2

MgADP increases the open probability of WT KATP channels and stabilizes more outward-facing receptor conformations (42); thus, the effect of MgADP on GBM binding was determined for WT SUR1 versus WT SUR1/WT Kir6.2 channels. Ortiz et al. (54) used an excess of MgAMP to minimize conversion of added ADP to ATP by adenylate kinase and reported that MgADP stabilized SUR1 conformations with lower affinity for GBM somewhat better than MgATP. We added hexokinase plus glucose to reduce low levels of contaminant ATP and to convert any generated ATP to ADP. Under these conditions, MgADP was nearly as effective at switching the conformation of WT SUR1 as MgATP (dissociation constant for ADP, KADP, ∼55 (38–107) versus KT ∼38 (24–52) μm, respectively) with a β value of 1.8 (1.6–1.9) but had no significant effect on the GBM interaction with channels (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Effect of MgADP on allosteric coupling in SUR1 alone versus SUR1 in KATP channels. Increasing MgADP reduces bound [3H]GBM (1 nm). The KG values from Fig. 4 were used to estimate β and KADP. The SUR1 curve was drawn using best-fit parameters (mean (lower confidence interval–upper confidence interval): KG = 0.25 (0.19–0.32) nm, KADP = 55 (28–107) μm, and β = 1.8 (1.6–1.9)). Points are means ± S.E., n = 6.

Discussion

ATP has dual effects on (SUR1/Kir6.2)4 neuroendocrine KATP channels. Nucleotide interactions with the Kir6.2 pore inhibit channel openings, whereas binding to SUR1, including potential enzymatic activities, activate openings. This study focused on the ATP-binding cassette subunit ABCC8/SUR1, whether enzymatic hydrolysis of ATP by SUR1 is needed for channel activation, identifying which receptor conformation(s) activates channel openings, and the allosteric pathways coupling the SUR1 ATP- and GBM-binding sites.

ATP binding to SUR1 is sufficient to activate KATP channels

Prior results (53–55) and the data in Figs. 2 and 3 show that strong coupling between ATP hydrolysis and channel gating is not required. ATP binding, a key part of any ABC protein enzymatic cycle, is enough to switch SUR1 to activating conformations. Like other ABC proteins. SUR1 interacts with two ATPs with differing affinities (80). We assume that NBD1, with a higher affinity for ATP (±Mg2+), is occupied and that ATP binding at NBD2 results in NBD dimerization and a repositioning of TMDs 1 and 2 from inward- to more outward-facing conformations as confirmed by cryo-EM structures of KATP channels (42, 57). The agonist action of ATP4−, without Mg2+, on SUR1 mutant channels with impaired ATPase activity is clearly demonstrable when the inhibitory effect of ATP binding on the Kir6.2 pore is minimized (Fig. 2). This demonstrates that ATP is a KATP channel agonist and identifies ATP-bound, outward-facing states of SUR1 as activating conformations. This agonist action and our earlier reports (54, 55) on nucleotide-induced switching of SUR1 conformations show the dependence of switching, and thus agonist action, on the affinity of SUR1 for ATP4− or MgATP. SUR1 has a weaker affinity for ATP4− than MgATP and is less potent at switching conformations and activating channel openings (Fig. 1C). This dependence is physiologically and clinically important; ABCC8/SUR1 mutations, identified in cases of neonatal diabetes, have higher affinities for ATP, whereas mutations identified in cases of congenital hyperinsulinism have reduced affinities (65).

The idea that ATP is a KATP channel agonist is counterintuitive as it is widely appreciated that eliminating nucleotides, for example by pulling insulin-secreting β-cell membrane patches into nucleotide-free medium, a maneuver that favors inward-facing conformations, produces a large increase in KATP channel openings (see Fig. 3 for example). Despite this apparent contradiction, the results are readily rationalized. Removing nucleotides eliminates their inhibitory action on the Kir6.2 pore and shifts the SUR1 population in favor of inward-facing, nonactivating states, but the remaining equilibrium fraction of outward-facing, activating conformers supports channel openings. If this is correct, added sulfonylureas, e.g. tolbutamide or GBM, should act as “inverse agonists” by selecting and stabilizing inward-facing, nonactivating conformers. This idea is supported by early studies (37, 81–84), including the first report showing that the sulfonylurea receptor was part of KATP channels and that active, open channels, without added Mg2+ or ATP, were inhibited by tolbutamide or GBM (30). The idea that GBM binding will stabilize inward-facing conformers is a consequence of the high affinity of SUR1 for GBM and is directly supported by cryo-EM studies (77, 78).

Assembly with Kir6.2 alters ATP-induced switching of SUR1 between conformations with high or low affinity for GBM

ATP binding switches SUR1 to outward-facing conformations that activate channel openings (Figs. 2 and 3). This ATP-induced conformational change noncompetitively reduces [3H]GBM binding to SUR1 alone or in KATP channels (Figs. 5–7). The reduction of bound [3H]GBM by ATP is incomplete; at high, saturating concentrations of ATP, the remaining bound fraction reflects a new, lower-affinity equilibrium between [3H]GBM and ATP-bound SUR1 either alone or in channels. We used a four-state equilibrium model (Fig. 5, inset, and Equation 1) to quantify the allosteric reduction of bound [3H]GBM by ATP and to evaluate the effect(s) of pairing SUR1 with Kir6.2 on this allosteric coupling. Equation 1 relates bound [3H]GBM to the concentrations of GBM and ATP, their respective dissociation constants (KG for [3H]GBM and KT for nucleotides), and an allosteric coupling constant, β. The products, βKG and βKT, reflect the dissociation constants for ATP-bound and GBM-bound complexes, respectively. As described above, we assume ATP binding at NBD2 drives the conformational change (54, 55). In structural terms, this reflects switching SUR1 from inward-facing, nucleotide-free “apo” or singly liganded states with the greatest affinity for GBM to outward-facing, ATP-bound states with lower affinity.

To apply the four-state model, the dissociation constants for [3H]GBM, KG, are determined independently (Fig. 4 and Table 1) and assumed constant when fitting the ATP inhibition data. Determinations of KT and β for WT SUR1 alone or in channels (Fig. 5 and Table 2) indicate that the affinities of ATP-bound SUR1 alone or in channels for [3H]GBM are ∼5- or ∼2.2-fold weaker than the unliganded molecules, respectively (compare KG versus βKG values in Table 2). Thus, the greater reduction in bound [3H]GBM seen for SUR1 alone reflects the ∼5-fold weaker affinity of ATP-bound SUR1 for [3H]GBM. The lesser ATP effect observed for channels reflects the smaller change in affinities. The negative allosteric effects are reciprocal; GBM-bound SUR1 alone or in channels has a corresponding lower affinity for ATP (compare KT versus βKT values in Table 2). The data have two implications. First, the results imply that the attenuation of the agonist action of ATP underlies the inhibitory effect of GBM on WT KATP channels. Basically, ATP binding to SUR1 biases channels toward open states; reducing the affinity of SUR1 for ATP reduces channel activity. Second, the negative allosteric linkage is clinically important; glibenclamide is now a common therapy for the treatment of cases of neonatal diabetes (85), and GBM therapy will attenuate the excess agonist action of ATP on ABCC8/SUR1 mutations with higher affinities for ATP. Thus, GBM therapy attenuates the consequences of neonatal diabetes ABCC8 mutations with higher affinities for ATP by reducing their affinities for nucleotides.

We applied the four-state model to assess how MgADP affects ATP/GBM site coupling with somewhat surprising results. In agreement with earlier studies (54), MgADP did stabilize lower-affinity conformers of SUR1, but the effect on full channels was negligible (Fig. 7). The estimated KADP for MgADP binding to SUR1 alone was like the KT for MgATP, but the allosteric factor, β = 1.8, was low, and the reduction in bound [3H]GBM was less than for MgATP (Fig. 7). The result suggests that the energy of MgADP binding at both NBD1 and NBD2 may not be enough to stabilize SUR1 conformers in full channels that have a lower KG for [3H]GBM; ATP binding to NBD1 may be needed. Structural studies on channels with both GBM and ADP present and/or bound are needed to determine whether GBM prevents dimerization of the NBDs or affects reconfiguration of the TMDs to activating conformations.

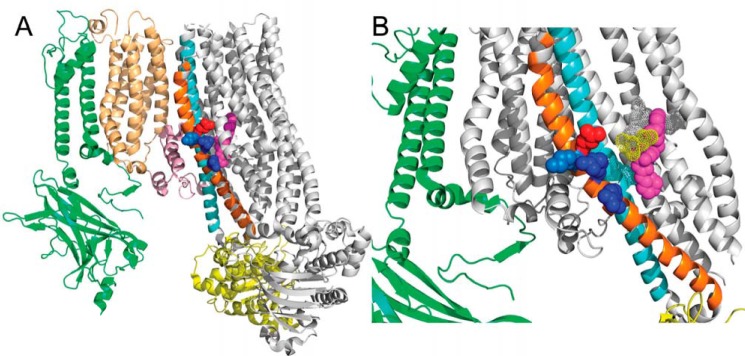

A potential structural pathway coupling the SUR1 ATP- and GBM-binding sites

Our results (Fig. 5 and Refs. 54, 55, and 65) and early studies on the effects of nucleotides on [3H]GBM binding clearly demonstrate negative allosteric effects (51, 58, 86–88). However, essentially nothing is known about possible amino acid networks or structural pathways coupling the ATP-binding sites (NBDs) with the GBM-binding site in SUR1. One obvious candidate is the pair of “crossover” helices (15 and 16) that link NBD1 with TMD2 in SUR1 (57, 77, 78) and other ABC proteins. We tested this possibility using SUR1Q1179R, a well-studied neonatal diabetes mutation (54, 55, 65, 89, 90). The Gln → Arg substitution at position 1179, near the top of helix 15 within 20 nm of the GBM-binding site (Fig. 8 and Ref. 41), effectively eliminates the constraint on coupling imposed by assembly with Kir6.2 (Fig. 7) This substitution places a positive charge adjacent to Lys-1180 and approximately one helical turn from Arg-1174. The introduced charge has two effects, increasing the KG of the “Arg” variant for [3H]GBM and increasing the allosteric factor β significantly. The results are consistent with the swapped transmembrane helices 15 and 16 coupling ATP binding and NBD dimerization with the sulfonylurea-binding site.

Figure 8.

Positioning of amino acid Gln-1179 in helix 15 relative to the GBM-binding site. A shows one Kir6.2 subunit (green) interacting with SUR1 core (gray) through TMD0 (tan) and L0 (pink). Helices 15 and 16 are orange and cyan, respectively. Residues Gln-1179 (red), Lys-1180 (light blue), Arg-1182 and Arg-1187 (dark blue) and GBM (magenta) are shown. NBD1 is shown in yellow. B is an enlarged view of the GBM site with the helices in the forefront hidden. The dotted surfaces show the amino acids identified in Martin et al. (41) as part of the GBM-binding site.

Why does assembly with Kir6.2 increase the affinity of SUR1 for [3H]GBM?

As noted above, to apply the four-state model, the dissociation constants for [3H]GBM were determined separately (Fig. 4 and Table 1). The results, although consistent with earlier studies reporting that SUR1 in channels binds [3H]GBM 5–10-fold more tightly than SUR1 alone (75, 91), are not well understood. The increased affinity is not unique to GBM; repaglinide, a related channel antagonist, has a 100–150-fold higher affinity for SUR1 in channels versus the receptor alone (75, 76). Early mechanistic attempts to account for these differences proposed that KNtp, the N terminus of Kir6.2, contributed in a direct fashion to GBM binding (for reviews, see Refs. 40, 92, and 93). A variety of data support a direct interaction, including the finding that truncations of KNtp eliminate the difference in affinity between channels and receptors (75, 76) but increase channel open probability and reduce the inhibitory action of the sulfonylurea antagonist tolbutamide (76, 94–96). Photoaffinity labeling with an azido derivative of GBM labels Kir6.2 but not truncated subunits missing KNtp, which implies that KNtp is near GBM (97). Restricting the positioning of KNtp by fusing the Kir and SUR N and C termini, SUR1–Kir6.2 (3–5), or by constructing “triple fusions,” SUR1–(Kir6.2)2, markedly reduces the affinities for MgATP and GBM (3). Additional studies tested the effects of a synthetic 32-amino-acid “KNtp,” showing it reduces the open probability of ΔN32Kir6.2/SUR1 channels but increases channel activity when applied to full-length channels (96). This suggested that SUR1 has a binding site for KNtp, whose occupation in truncated channels partially restores function, but competing with the endogenous KNtp mimics the effects of truncation (96). If KNtp is near GBM, as implied by these early results, the cryo-EM localization of bound GBM (41, 42) suggests that KNtp can access the central cavity and that SUR1 is a cryptic or frustrated peptide transporter. A cryo-EM study by Wu et al. (42) provides some support for this idea, reporting that electron densities near the GBM site may be due to KNtp, although the densities are not strong enough to allow modeling of the Kir N terminus. How this cryptic transport activity and potential movement(s) of KNtp during ATP-driven SUR1 conformational changes are coupled to channel gating remains an intriguing open question.

Summary

We have shown that ATP acts as a KATP channel agonist, switching SUR1 from inward- to outward-facing conformations that can activate channel openings. This is easily demonstrated when the inhibitory effects of ATP on the pore are minimized and ND mutants of SUR1 with higher affinity for ATP are tested. ATP binding is sufficient; strong coupling to ATP hydrolysis is not required. ATP-induced switching has a negative allosteric effect on GBM binding; channel activating, outward-facing conformations have the lowest affinity for GBM as expected for a channel antagonist. The allosteric effects are reciprocal; bound GBM reduces the affinity of SUR1 for ATP; thus, treatment with sulfonylureas will reduce the agonist action of ATP on WT and ND mutant channels and reduce channel openings. The structural links between the NBDs and GBM-binding site are not defined, but results with one ND SUR1 mutant, SUR1Q1179R, suggest involvement of helices 15 and 16 in TMD2 that contact NBD1. The biochemical prediction of ternary complexes, i.e. SUR1 liganded with both GBM and ATP, requires confirmation by cryo-EM studies.

Experimental procedures

Molecular biology and cell culture

WT or mutant hamster Abcc8/SUR1 cDNAs (National Institutes of Health NCBI sequence L40623.1) were cloned into the multiple cloning site of the Tet-On® 3G bicistronic inducible expression vector, pTRE3G-ZsGreen1 (TaKaRa Bio USA, Inc.). The ZsGreen1 marker was replaced by either WT human KCNJ11/Kir6.2 (National Institutes of Health reference sequence NG_012446) or KCNJ11/Kir6.2G334D in which aspartic acid was substituted for glycine at position 334. A puromycin resistance cassette was either engineered into the resulting plasmid or cotransfected into HEK 293 Tet-On cells carrying the Tet-On 3G transactivator (TaKaRa, Inc.). Amino acid numbering is based on the hamster sequence (NIH NCBI sequence L40623.1) to facilitate comparison with the numbering in the cryo-EM publications (41, 42, 77, 78). The exception is SUR1A1369S where the numbering follows the human reference sequence (National Institutes of Health NCBI accession number AH003589) without incorporation of exon 17. The equivalent numbering in the hamster sequence includes exon 17. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and glutamine. Stable cell lines were selected and subcloned using puromycin (600 μm). Expression was induced by addition of doxycycline (300 μm) and tested for characterization of channel activity from 24 to 72 h. In some experiments, transient transfections were done and induced with doxycycline after 24 h.

Membrane isolation

For membrane preparation, doxycycline-induced cells were centrifuged for 10 min at 500 × g at 37 °C and lysed by incubation in ice-cold hypotonic buffer containing 10 mm HEPES, 1 mm EGTA, and a protease inhibitor, HALT (Thermo Fisher), at pH 7.4. After 30 min on ice, the swollen cells were broken by 50 strokes in a tight-fitting Dounce homogenizer. Unbroken cells and nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 1,200 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was centrifuged at 105 × g at 4 °C for 60 min, and the resulting membrane pellet was resuspended in a buffer containing 5 mm HEPES, 5 mm KCl, and 139 mm NaCl at pH 7.4 (4 °C). Protein concentration was determined by the BCA method using BSA as the standard. The protein concentration was adjusted to 2.0 mg ml−1, and suspensions were frozen at −80 °C.

[3H]GBM homologous displacement experiments without nucleotides

The dissociation constant, KG, of SUR1 for [3H]GBM, in the absence of Mg2+ and nucleotides, was measured using isolated membranes from cells expressing WT or mutant SUR1 ± Kir6.2. Membranes were suspended in a buffered solution (139 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4) with 0.3 or 1 nm [3H]GBM plus increasing concentrations of unlabeled GBM for 30 min at 37 °C and then analyzed by rapid filtration as described previously (58) to determine total binding. The estimated values for free Mg2+, <10 nm, were calculated using MAXC (98) assuming contaminating Ca2+ and Mg2+ levels as high as 5 μm. Triplicate determinations were made for each GBM concentration per experiment; the data from three or more experiments were analyzed following the procedure described by Swillens (74) for homologous displacement curves. Analysis and global fitting were done with user-written functions in Origin2018 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA) or in Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). The data were weighted using a factor of (1/cpm)2.

[3H]GBM binding in nucleotide-containing solutions

[3H]GBM binding to isolated membranes was analyzed by rapid filtration as described previously (58). The [3H]GBM concentration, ∼1 nm, was determined for each experiment. MgATP-containing solutions (concentrations ranging from 10 nm to 10 mm MgATP) with a calculated free Mg2+ concentration of 1 mm were prepared using the BioEqCalc program from Akers and Goldberg (99). Solutions contained 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 5 mm KCl, and varying amounts of Na2ATP, MgCl2, and NaCl to give the appropriate MgATP concentration at an ionic strength of 0.2 m.

In the experiments using MgADP, hexokinase (1 unit) and glucose (10 mm) were added to scavenge contaminant ATP and ATP generated by adenylate kinase. ATP determinations using luciferase indicate that the ATP levels were <0.1% of added ADP. The solution conditions, pH, ionic strength, and free Mg2+ concentrations, for the MgADP experiments were equivalent to those for MgATP described above.

Model fitting

The four-state equilibrium model (Fig. 5, inset) described previously (54) was used to estimate the dissociation constant, KT, for binding of ATP (or KADP for ADP) at NBD2 of SUR1 and the allosteric constant β. The dissociation constants (KG) for [3H]GBM were estimated independently as described above and held constant. Following Alper and Gelb (100) and Christopoulos (101), a transformed binding equation was used with nonlinear least-squares methods to estimate approximately normally distributed values for pKT and pβ and to estimate confidence intervals.

| (Eq. 1) |

Here, KT = 10pKT and β = 10pβ.

Electrophysiology

Patch-clamp recordings were done in the inside-out configuration. KATP currents were measured at a membrane potential of −50 mV (pipette voltage, +50 mV); inward currents are shown as downward deflections. Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (Harvard Apparatus, March-Hugstetten, Germany) and had a resistance of 6–8 megaohms. Currents were recorded with an EPC-9 patch-clamp amplifier using Patchmaster software (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany). Single-channel KATP channel currents were about −4 pA at a holding potential of −50 mV, corresponding to a single-channel conductance of 80 picosiemens.

The pipette solution contained 130 mmol/liter KCl, 1.2 mmol/liter MgCl2, 2 mmol/liter CaCl2, 10 mmol/liter EGTA, and 10 mmol/liter HEPES; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with KOH at 25 °C. The magnesium-free bath solution contained 130 mmol/liter KCl, 4.6 mmol/liter CaCl2, 10 mmol/liter EDTA, and 20 mmol/liter HEPES with pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH at 25 °C. The MgATP bath solution contained 130 mmol/liter KCl, 2 mmol/liter CaCl2, 10 mmol/liter EGTA, 1 mmol/liter Na2ATP, 1.7 mmol/liter MgCl2, and 20 mmol/liter HEPES with pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH at 25 °C. Analyses to estimate NPo were done offline in IgorPro 7 (Wavemetrics, Inc., Lake Oswego, OR) with user-written software.

Statistics

Data values are given as means ± S.E. (n = number of replications). Estimated parameter values are reported as means ± (lower–higher) 95% confidence intervals. In Fig. 2, the number of channels in patches from randomly selected cells and randomly selected locations varied widely, presumably due to differences in expression levels and/or cell-surface distribution. To determine the significance of the action of nucleotides on SUR1/Kir6.2G334D KATP channels, in the absence of Mg2+, a nonparametric statistic, W, in the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied (102). This is a paired-difference test. Patches are chosen randomly, and the NPo values are determined for a fixed time, typically 30–60 s before and 30–60 s at the end of an application of nucleotide. The absolute differences in NPo values, plus versus minus nucleotide, were calculated and ranked smallest to largest. In all cases, the signed differences were positive; i.e. application of nucleotides always increased the NPo. The rank times the difference values were summed to give W. Comparison of W with calculated values for small sample numbers or using online Wilcoxon tests (e.g. http://www.vassarstats.net/wilcoxon.html)3 gave estimates of statistical significance. p values <0.05 were considered significant.

Author contributions

J. S., T. S. M., C. B., F. D., U. Q., P. K.-D., and J. B. data curation; J. S., T. S. M., C. B., U. Q., P. K.-D., G. D., and J. B. formal analysis; J. S., T. S. M., C. B., F. D., U. Q., P. K.-D., G. D., and J. B. validation; J. S., T. S. M., C. B., F. D., U. Q., P. K.-D., G. D., and J. B. investigation; J. S., T. S. M., C. B., F. D., U. Q., P. K.-D., G. D., and J. B. methodology; J. S., U. Q., and J. B. writing-original draft; J. S., T. S. M., C. B., F. D., U. Q., P. K.-D., G. D., and J. B. writing-review and editing; T. S. M., U. Q., and J. B. visualization; U. Q. and J. B. conceptualization; P. K.-D., G. D., and J. B. supervision; J. B. resources; J. B. software; J. B. funding acquisition.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Robert Goldberg for providing an updated version of BioCalcEq running under Mathematica v11.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK098647 (to J. B.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party-hosted site.

- KATP

- ATP-sensitive K+

- SUR1

- sulfonylurea receptor 1

- Kir

- K+-selective inward rectifier

- GBM

- glibenclamide

- KNtp

- Kir N terminus

- ND

- neonatal diabetes

- AMPPNP

- 5′-adenylyl-β,γ-imidodiphosphate

- AMPPCP

- adenosine 5′-(β,γ-methylene)triphosphate

- ATPγS

- adenosine 5′-O-(thiotriphosphate)

- NBD

- nucleotide-binding domain

- TMD

- transmembrane helical domain

- KD

- dissociation constant

- KG

- dissociation constant for GBM

- KT

- dissociation constant for ATP

- β

- allosteric constant

- KADP

- dissociation constant for ADP.

References

- 1. Aguilar-Bryan L., Nichols C. G., Wechsler S. W., Clement J. P. 4th, Boyd A. E. 3rd, González G., Herrera-Sosa H., Nguy K., Bryan J., and Nelson D. A. (1995) Cloning of the β cell high-affinity sulfonylurea receptor: a regulator of insulin secretion. Science 268, 423–426 10.1126/science.7716547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Inagaki N., Gonoi T., Clement J. P. 4th, Namba N., Inazawa J., Gonzalez G., Aguilar-Bryan L., Seino S., and Bryan J. (1995) Reconstitution of IKATP: an inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science 270, 1166–1170 10.1126/science.270.5239.1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clement J. P. 4th, Kunjilwar K., Gonzalez G., Schwanstecher M., Panten U., Aguilar-Bryan L., and Bryan J. (1997) Association and stoichiometry of KATP channel subunits. Neuron 18, 827–838 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80321-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Inagaki N., Gonoi T., and Seino S. (1997) Subunit stoichiometry of the pancreatic β-cell ATP-sensitive K+ channel. FEBS Lett. 409, 232–236 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00488-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shyng S., and Nichols C. G. (1997) Octameric stoichiometry of the KATP channel complex. J. Gen. Physiol. 110, 655–664 10.1085/jgp.110.6.655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thomas P. M., Cote G. J., Wohllk N., Haddad B., Mathew P. M., Rabl W., Aguilar-Bryan L., Gagel R. F., and Bryan J. (1995) Mutations in the sulfonylurea receptor gene in familial persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy. Science 268, 426–429 10.1126/science.7716548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aguilar-Bryan L., and Bryan J. (1999) Molecular biology of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels. Endocr. Rev. 20, 101–135 10.1210/edrv.20.2.0361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bryan J., Muñoz A., Zhang X., Düfer M., Drews G., Krippeit-Drews P., and Aguilar-Bryan L. (2007) ABCC8 and ABCC9: ABC transporters that regulate K+ channels. Pflugers Arch 453, 703–718 10.1007/s00424-006-0116-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hattersley A. T., and Ashcroft F. M. (2005) Activating mutations in Kir6.2 and neonatal diabetes: new clinical syndromes, new scientific insights, and new therapy. Diabetes 54, 2503–2513 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Babenko A. P., Polak M., Cavé H., Busiah K., Czernichow P., Scharfmann R., Bryan J., Aguilar-Bryan L., Vaxillaire M., and Froguel P. (2006) Activating mutations in the ABCC8 gene in neonatal diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 456–466 10.1056/NEJMoa055068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aguilar-Bryan L., and Bryan J. (2008) Neonatal diabetes mellitus. Endocr. Rev. 29, 265–291 10.1210/er.2007-0029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hattersley A. T., and Patel K. A. (2017) Precision diabetes: learning from monogenic diabetes. Diabetologia 60, 769–777 10.1007/s00125-017-4226-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bowman P., Flanagan S. E., Edghill E. L., Damhuis A., Shepherd M. H., Paisey R., Hattersley A. T., and Ellard S. (2012) Heterozygous ABCC8 mutations are a cause of MODY. Diabetologia 55, 123–127 10.1007/s00125-011-2319-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Emdin C. A., Klarin D., Natarajan P., CARDIOGRAM Exome Consortium, Florez J. C., Kathiresan S., and Khera A. V. (2017) Genetic variation at the sulfonylurea receptor, type 2 diabetes, and coronary heart disease. Diabetes 66, 2310–2315 10.2337/db17-0149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cook D. L., and Hales C. N. (1984) Intracellular ATP directly blocks K+ channels in pancreatic β-cells. Nature 311, 271–273 10.1038/311271a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dunne M. J., and Petersen O. H. (1986) Intracellular ADP activates K+ channels that are inhibited by ATP in an insulin-secreting cell line. FEBS Lett. 208, 59–62 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81532-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kakei M., Kelly R. P., Ashcroft S. J., and Ashcroft F. M. (1986) The ATP-sensitivity of K+ channels in rat pancreatic β-cells is modulated by ADP. FEBS Lett. 208, 63–66 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81533-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hopkins W. F., Fatherazi S., Peter-Riesch B., Corkey B. E., and Cook D. L. (1992) Two sites for adenine-nucleotide regulation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in mouse pancreatic β-cells and HIT cells. J. Membr. Biol. 129, 287–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tucker S. J., Gribble F. M., Zhao C., Trapp S., and Ashcroft F. M. (1997) Truncation of Kir6.2 produces ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor. Nature 387, 179–183 10.1038/387179a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gribble F. M., Tucker S. J., Haug T., and Ashcroft F. M. (1998) MgATP activates the β cell KATP channel by interaction with its SUR1 subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7185–7190 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baukrowitz T., Schulte U., Oliver D., Herlitze S., Krauter T., Tucker S. J., Ruppersberg J. P., and Fakler B. (1998) PIP2 and PIP as determinants for ATP inhibition of KATP channels. Science 282, 1141–1144 10.1126/science.282.5391.1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shyng S. L., and Nichols C. G. (1998) Membrane phospholipid control of nucleotide sensitivity of KATP channels. Science 282, 1138–1141 10.1126/science.282.5391.1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baukrowitz T., and Fakler B. (2000) KATP channels: linker between phospholipid metabolism and excitability. Biochem. Pharmacol. 60, 735–740 10.1016/S0006-2952(00)00267-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bränström R., Leibiger I. B., Leibiger B., Corkey B. E., Berggren P. O., and Larsson O. (1998) Long chain coenzyme A esters activate the pore-forming subunit (Kir6.2) of the ATP-regulated potassium channel. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 31395–31400 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rohács T., Lopes C. M., Jin T., Ramdya P. P., Molnár Z., and Logothetis D. E. (2003) Specificity of activation by phosphoinositides determines lipid regulation of Kir channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 745–750 10.1073/pnas.0236364100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schulze D., Rapedius M., Krauter T., and Baukrowitz T. (2003) Long-chain acyl-CoA esters and phosphatidylinositol phosphates modulate ATP inhibition of KATP channels by the same mechanism. J. Physiol. 552, 357–367 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.047035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Béguin P., Nagashima K., Nishimura M., Gonoi T., and Seino S. (1999) PKA-mediated phosphorylation of the human KATP channel: separate roles of Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunit phosphorylation. EMBO J. 18, 4722–4732 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Light P. E., Manning Fox J. E., Riedel M. J., and Wheeler M. B. (2002) Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits pancreatic ATP-sensitive potassium channels via a protein kinase A- and ADP-dependent mechanism. Mol. Endocrinol. 16, 2135–2144 10.1210/me.2002-0084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lin Y. F., and Chai Y. (2008) Functional modulation of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel by extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mediated phosphorylation. Neuroscience 152, 371–380 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sturgess N. C., Ashford M. L., Cook D. L., and Hales C. N. (1985) The sulphonylurea receptor may be an ATP-sensitive potassium channel. Lancet 2, 474–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sturgess N. C., Kozlowski R. Z., Carrington C. A., Hales C. N., and Ashford M. L. (1988) Effects of sulphonylureas and diazoxide on insulin secretion and nucleotide-sensitive channels in an insulin-secreting cell line. Br. J. Pharmacol. 95, 83–94 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb16551.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ashcroft F. M., Kakei M., Gibson J. S., Gray D. W., and Sutton R. (1989) The ATP- and tolbutamide-sensitivity of the ATP-sensitive K-channel from human pancreatic β cells. Diabetologia 32, 591–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Panten U., Heipel C., Rosenberger F., Scheffer K., Zünkler B. J., and Schwanstecher C. (1990) Tolbutamide-sensitivity of the adenosine 5′-triphosphate-dependent K+ channel in mouse pancreatic β-cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 342, 566–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hu S., Wang S., Fanelli B., Bell P. A., Dunning B. E., Geisse S., Schmitz R., and Boettcher B. R. (2000) Pancreatic β-cell K(ATP) channel activity and membrane-binding studies with nateglinide: A comparison with sulfonylureas and repaglinide. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 293, 444–452 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dabrowski M., Wahl P., Holmes W. E., and Ashcroft F. M. (2001) Effect of repaglinide on cloned β cell, cardiac and smooth muscle types of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Diabetologia 44, 747–756 10.1007/s001250051684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Quast U., Stephan D., Bieger S., and Russ U. (2004) The impact of ATP-sensitive K+ channel subtype selectivity of insulin secretagogues for the coronary vasculature and the myocardium. Diabetes 53, Suppl. 3, S156–S164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dunne M. J., Illot M. C., and Peterson O. H. (1987) Interaction of diazoxide, tolbutamide and ATP4− on nucleotide-dependent K+ channels in an insulin-secreting cell line. J. Membr. Biol. 99, 215–224 10.1007/BF01995702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lebrun P., Devreux V., Hermann M., and Herchuelz A. (1989) Similarities between the effects of pinacidil and diazoxide on ionic and secretory events in rat pancreatic islets. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 250, 1011–1018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Niki I., and Ashcroft S. J. (1991) Possible involvement of protein phosphorylation in the regulation of the sulphonylurea receptor of a pancreatic β-cell line, HIT T15. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1133, 95–101 10.1016/0167-4889(91)90246-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bryan J., Crane A., Vila-Carriles W. H., Babenko A. P., and Aguilar-Bryan L. (2005) Insulin secretagogues, sulfonylurea receptors and KATP channels. Curr. Pharm. Des. 11, 2699–2716 10.2174/1381612054546879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martin G. M., Kandasamy B., DiMaio F., Yoshioka C., and Shyng S. L. (2017) Anti-diabetic drug binding site in a mammalian KATP channel revealed by cryo-EM. Elife 6, e31054 10.7554/eLife.31054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu J. X., Ding D., Wang M., Kang Y., Zeng X., and Chen L. (2018) Ligand binding and conformational changes of SUR1 subunit in pancreatic ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Protein Cell 9, 553–567 10.1007/s13238-018-0530-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Linton K. J. (2007) Structure and function of ABC transporters. Physiology 22, 122–130 10.1152/physiol.00046.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Oldham M. L., Davidson A. L., and Chen J. (2008) Structural insights into ABC transporter mechanism. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18, 726–733 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rees D. C., Johnson E., and Lewinson O. (2009) ABC transporters: the power to change. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 218–227 10.1038/nrm2646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zingman L. V., Alekseev A. E., Bienengraeber M., Hodgson D., Karger A. B., Dzeja P. P., and Terzic A. (2001) Signaling in channel/enzyme multimers: ATPase transitions in SUR module gate ATP-sensitive K+ conductance. Neuron 31, 233–245 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00356-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zingman L. V., Hodgson D. M., Bienengraeber M., Karger A. B., Kathmann E. C., Alekseev A. E., and Terzic A. (2002) Tandem function of nucleotide binding domains confers competence to sulfonylurea receptor in gating ATP-sensitive K+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 14206–14210 10.1074/jbc.M109452200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bienengraeber M., Alekseev A. E., Abraham M. R., Carrasco A. J., Moreau C., Vivaudou M., Dzeja P. P., and Terzic A. (2000) ATPase activity of the sulfonylurea receptor: a catalytic function for the KATP channel complex. FASEB J. 14, 1943–1952 10.1096/fj.00-0027com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zingman L. V., Alekseev A. E., Hodgson-Zingman D. M., and Terzic A. (2007) ATP-sensitive potassium channels: metabolic sensing and cardioprotection. J. Appl. Physiol. 103, 1888–1893 10.1152/japplphysiol.00747.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dickinson K. E., Bryson C. C., Cohen R. B., Rogers L., Green D. W., and Atwal K. S. (1997) Nucleotide regulation and characteristics of potassium channel opener binding to skeletal muscle membranes. Mol. Pharmacol. 52, 473–481 10.1124/mol.52.3.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hambrock A., Löffler-Walz C., Kurachi Y., and Quast U. (1998) Mg2+ and ATP dependence of KATP channel modulator binding to the recombinant sulphonylurea receptor, SUR2B. Br. J. Pharmacol. 125, 577–583 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schwanstecher M., Sieverding C., Dörschner H., Gross I., Aguilar-Bryan L., Schwanstecher C., and Bryan J. (1998) Potassium channel openers require ATP to bind to and act through sulfonylurea receptors. EMBO J. 17, 5529–5535 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Choi K. H., Tantama M., and Licht S. (2008) Testing for violations of microscopic reversibility in ATP-sensitive potassium channel gating. J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 10314–10321 10.1021/jp712088v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ortiz D., Voyvodic P., Gossack L., Quast U., and Bryan J. (2012) Two neonatal diabetes mutations on transmembrane helix 15 of SUR1 increase affinity for ATP and ADP at nucleotide binding domain 2. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 17985–17995 10.1074/jbc.M112.349019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ortiz D., Gossack L., Quast U., and Bryan J. (2013) Reinterpreting the action of ATP analogs on KATP channels. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 18894–18902 10.1074/jbc.M113.476887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. de Wet H., Mikhailov M. V., Fotinou C., Dreger M., Craig T. J., Vénien-Bryan C., and Ashcroft F. M. (2007) Studies of the ATPase activity of the ABC protein SUR1. FEBS J 274, 3532–3544 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lee K. P. K., Chen J., and MacKinnon R. (2017) Molecular structure of human KATP in complex with ATP and ADP. Elife 6, e32481 10.7554/eLife.32481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hambrock A., Löffler-Walz C., and Quast U. (2002) Glibenclamide binding to sulphonylurea receptor subtypes: dependence on adenine nucleotides. Br. J. Pharmacol. 136, 995–1004 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Masia R., Koster J. C., Tumini S., Chiarelli F., Colombo C., Nichols C. G., and Barbetti F. (2007) An ATP-binding mutation (G334D) in KCNJ11 is associated with a sulfonylurea-insensitive form of developmental delay, epilepsy, and neonatal diabetes. Diabetes 56, 328–336 10.2337/db06-1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Li L., Wang J., and Drain P. (2000) The I182 region of KIR6.2 is closely associated with ligand binding in KATP channel inhibition by ATP. Biophys. J. 79, 841–852 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76340-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Proks P., de Wet H., and Ashcroft F. M. (2013) Molecular mechanism of sulphonylurea block of KATP channels carrying mutations that impair ATP inhibition and cause neonatal diabetes. Diabetes 62, 3909–3919 10.2337/db13-0531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Proks P., de Wet H., and Ashcroft F. M. (2014) Sulfonylureas suppress the stimulatory action of Mg-nucleotides on Kir6.2/SUR1 but not Kir6.2/SUR2A KATP channels: a mechanistic study. J. Gen. Physiol. 144, 469–486 10.1085/jgp.201411222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Babenko A. P., Gonzalez G., and Bryan J. (1999) Two regions of sulfonylurea receptor specify the spontaneous bursting and ATP inhibition of KATP channel isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 11587–11592 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Babenko A. P., and Bryan J. (2001) A conserved inhibitory and differential stimulatory action of nucleotides on KIR6.0/SUR complexes is essential for excitation-metabolism coupling by KATP channels. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 49083–49092 10.1074/jbc.M108763200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ortiz D., and Bryan J. (2015) Neonatal diabetes and congenital hyperinsulinism caused by mutations in ABCC8/SUR1 are associated with altered and opposite affinities for ATP and ADP. Front. Endocrinol. 6, 48 10.3389/fendo.2015.00048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fatehi M., Raja M., Carter C., Soliman D., Holt A., and Light P. E. (2012) The ATP-sensitive K+ channel ABCC8 S1369A type 2 diabetes risk variant increases MgATPase activity. Diabetes 61, 241–249 10.2337/db11-0371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Fatehi M., Carter C. R., Youssef N., Hunter B. E., Holt A., and Light P. E. (2015) Molecular determinants of ATP-sensitive potassium channel MgATPase activity: diabetes risk variants and diazoxide sensitivity. Biosci. Rep. 35, e00238 10.1042/BSR20150143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Orelle C., Dalmas O., Gros P., Di Pietro A., and Jault J. M. (2003) The conserved glutamate residue adjacent to the Walker-B motif is the catalytic base for ATP hydrolysis in the ATP-binding cassette transporter BmrA. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47002–47008 10.1074/jbc.M308268200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tombline G., Bartholomew L. A., Tyndall G. A., Gimi K., Urbatsch I. L., and Senior A. E. (2004) Properties of P-glycoprotein with mutations in the “catalytic carboxylate” glutamate residues. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 46518–46526 10.1074/jbc.M408052200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Moody J. E., Millen L., Binns D., Hunt J. F., and Thomas P. J. (2002) Cooperative, ATP-dependent association of the nucleotide binding cassettes during the catalytic cycle of ATP-binding cassette transporters. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 21111–21114 10.1074/jbc.C200228200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Smith P. C., Karpowich N., Millen L., Moody J. E., Rosen J., Thomas P. J., and Hunt J. F. (2002) ATP binding to the motor domain from an ABC transporter drives formation of a nucleotide sandwich dimer. Mol. Cell 10, 139–149 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00576-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Oldham M. L., Khare D., Quiocho F. A., Davidson A. L., and Chen J. (2007) Crystal structure of a catalytic intermediate of the maltose transporter. Nature 450, 515–521 10.1038/nature06264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pinney S. E., MacMullen C., Becker S., Lin Y. W., Hanna C., Thornton P., Ganguly A., Shyng S. L., and Stanley C. A. (2008) Clinical characteristics and biochemical mechanisms of congenital hyperinsulinism associated with dominant KATP channel mutations. J. Clin. Investig. 118, 2877–2886 10.1172/JCI35414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Swillens S. (1995) Interpretation of binding curves obtained with high receptor concentrations: practical aid for computer analysis. Mol. Pharmacol. 47, 1197–1203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hansen A. M., Hansen J. B., Carr R. D., Ashcroft F. M., and Wahl P. (2005) Kir6.2-dependent high-affinity repaglinide binding to β-cell KATP channels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 144, 551–557 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kühner P., Prager R., Stephan D., Russ U., Winkler M., Ortiz D., Bryan J., and Quast U. (2012) Importance of the Kir6.2 N-terminus for the interaction of glibenclamide and repaglinide with the pancreatic KATP channel. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 385, 299–311 10.1007/s00210-011-0709-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Li N., Wu J. X., Ding D., Cheng J., Gao N., and Chen L. (2017) Structure of a pancreatic ATP-sensitive potassium channel. Cell 168, 101–110.e10 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Martin G. M., Yoshioka C., Rex E. A., Fay J. F., Xie Q., Whorton M. R., Chen J. Z., and Shyng S. L. (2017) Cryo-EM structure of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel illuminates mechanisms of assembly and gating. Elife 6, e24149 10.7554/eLife.24149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Mikhailov M. V., Campbell J. D., de Wet H., Shimomura K., Zadek B., Collins R. F., Sansom M. S., Ford R. C., and Ashcroft F. M. (2005) 3-D structural and functional characterization of the purified KATP channel complex Kir6.2-SUR1. EMBO J. 24, 4166–4175 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Matsuo M., Kioka N., Amachi T., and Ueda K. (1999) ATP binding properties of the nucleotide-binding folds of SUR1. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37479–37482 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Trube G., Rorsman P., and Ohno-Shosaku T. (1986) Opposite effects of tolbutamide and diazoxide on the ATP-dependent K+ channel in mouse pancreatic β-cells. Pflugers Arch. 407, 493–499 10.1007/BF00657506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Ashcroft F. M., Kakei M., Kelly R. P., and Sutton R. (1987) ATP-sensitive K+ channels in human isolated pancreatic β-cells. FEBS Lett. 215, 9–12 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80103-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Schmid-Antomarchi H., De Weille J., Fosset M., and Lazdunski M. (1987) The receptor for antidiabetic sulfonylureas controls the activity of the ATP-modulated K+ channel in insulin-secreting cells. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 15840–15844 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zünkler B. J., Lenzen S., Männer K., Panten U., and Trube G. (1988) Concentration-dependent effects of tolbutamide, meglitinide, glipizide, glibenclamide and diazoxide on ATP-regulated K+ currents in pancreatic β-cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 337, 225–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lemelman M. B., Letourneau L., and Greeley S. A. W. (2018) Neonatal diabetes mellitus: an update on diagnosis and management. Clin. Perinatol. 45, 41–59 10.1016/j.clp.2017.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Schwanstecher M., Löser S., Rietze I., and Panten U. (1991) Phosphate and thiophosphate group donating adenine and guanine nucleotides inhibit glibenclamide binding to membranes from pancreatic islets. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 343, 83–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Schwanstecher M., Löser S., Brandt C., Scheffer K., Rosenberger F., and Panten U. (1992) Adenine nucleotide-induced inhibition of binding of sulphonylureas to their receptor in pancreatic islets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 105, 531–534 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb09014.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Schwanstecher M., Löser S., Chudziak F., and Panten U. (1994) Identification of a 38-kDa high affinity sulfonylurea-binding peptide in insulin-secreting cells and cerebral cortex. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 17768–17771 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Christesen H. B. T., Sjoblad S., Brusgaard K., Papadopoulou D., and Jacobsen B. B. (2005) Permanent neonatal diabetes in a child with an ABBC8 gene mutation. Horm. Res. 64, 135 [Google Scholar]

- 90. Babenko A. P. (2008) A novel ABCC8 (SUR1)-dependent mechanism of metabolism-excitation uncoupling. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 8778–8782 10.1074/jbc.C700243200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Stephan D., Winkler M., Kühner P., Russ U., and Quast U. (2006) Selectivity of repaglinide and glibenclamide for the pancreatic over the cardiovascular KATP channels. Diabetologia 49, 2039–2048 10.1007/s00125-006-0307-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Bryan J., Vila-Carriles W. H., Zhao G., Babenko A. P., and Aguilar-Bryan L. (2004) Toward linking structure with function in ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Diabetes 53, Suppl. 3, S104–S112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Babenko A. P. (2005) KATP channels “vingt ans après”: ATG to PDB to Mechanism. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 39, 79–98 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Koster J. C., Sha Q., and Nichols C. G. (1999) Sulfonylurea and K+-channel opener sensitivity of KATP channels. Functional coupling of Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunits. J. Gen. Physiol. 114, 203–213 10.1085/jgp.114.2.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Reimann F., Tucker S. J., Proks P., and Ashcroft F. M. (1999) Involvement of the N-terminus of Kir6.2 in coupling to the sulphonylurea receptor. J. Physiol. 518, 325–336 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0325p.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Babenko A. P., and Bryan J. (2002) SUR-dependent modulation of KATP channels by an N-terminal KIR6.2 peptide. Defining intersubunit gating interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43997–44004 10.1074/jbc.M208085200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Vila-Carriles W. H., Zhao G., and Bryan J. (2007) Defining a binding pocket for sulfonylureas in ATP-sensitive potassium channels. FASEB J. 21, 18–25 10.1096/fj.06-6730hyp [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Bers D. M., Patton C. W., and Nuccitelli R. (2010) A practical guide to the preparation of Ca2+ buffers. Methods Cell Biol. 99, 1–26 10.1016/B978-0-12-374841-6.00001-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Akers D. L., and Goldberg R. N. (2001) BioEqCalc: a package for performing equilibrium calculations on biochemical reactions. Math. J. 8, 27 [Google Scholar]

- 100. Alper J. S., and Gelb R. I. (1993) Application of nonparametric statistics to the estimation of the accuracy of Monte Carlo confidence intervals in regression analysis. Talanta 40, 355–361 10.1016/0039-9140(93)80246-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Christopoulos A. (1998) Assessing the distribution of parameters in models of ligand-receptor interaction: to log or not to log. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 19, 351–357 10.1016/S0165-6147(98)01240-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Siegel S. (1956) Non-parametric Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences, pp. 75–85, McGraw-Hill, New York [Google Scholar]