Abstract

Most microbial pathogens have a metabolic iron requirement, necessitating the acquisition of this nutrient in the host. In response to pathogen invasion, the human host limits iron availability. Although canonical examples of nutritional immunity are host strategies that limit pathogen access to Fe(III), little is known about how the host restricts access to another biologically relevant oxidation state of this metal, Fe(II). This redox species is prevalent at certain infection sites and is utilized by bacteria during chronic infection, suggesting that Fe(II) withholding by the host may be an effective but unrecognized form of nutritional immunity. Here, we report that human calprotectin (CP; S100A8/S100A9 or MRP8/MRP14 heterooligomer) inhibits iron uptake and induces an iron starvation response in Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells by sequestering Fe(II) at its unusual His6 site. Moreover, under aerobic conditions in which the Fe(III) oxidation state is favored, Fe(II) withholding by CP was enabled by (i) its ability to stabilize this redox state in solution and (ii) the production and secretion of redox-active, P. aeruginosa–produced phenazines, which reduce Fe(III) to Fe(II). Analyses of the interplay between P. aeruginosa secondary metabolites and CP indicated that Fe(II) withholding alters P. aeruginosa physiology and expression of virulence traits. Lastly, examination of the effect of CP on cell-associated metal levels in diverse human pathogens revealed that CP inhibits iron uptake by several bacterial species under aerobic conditions. This work implicates CP-mediated Fe(II) sequestration as a component of nutritional immunity in both aerobic and anaerobic milieus during P. aeruginosa infection.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), bacteria, iron, innate immunity, metal homeostasis, calprotectin, nutritional immunity, phenazine, virulence, metal sequestration

Introduction

Iron is an essential nutrient for the vast majority of microbial pathogens that cause human disease (1). This metal ion can exist in several oxidation states, and microbes can acquire both the ferrous (+2) and ferric (+3) forms. During infection, the mammalian innate immune system limits the availability of iron and other essential metals to starve microbes and thus limit their growth in a process termed “nutritional immunity” (2, 3). Fe(III) withholding is the paradigm for nutritional immunity (1, 2); the complex interplay between host proteins that limit Fe(III) availability (transferrin, lactoferrin, and lipocalin-2 (siderocalin)) and diverse microbial Fe(III) acquisition strategies has been extensively studied (4–6). In contrast, the possibility of Fe(II) withholding by the innate immune system has been largely overlooked. Although Fe(II) can be abundant at chronic infection sites (7) and a variety of murine models highlight the importance of bacterial Fe(II) uptake systems during infection (8), an Fe(II)-sequestering host-defense protein was identified only recently (9). We discovered that human calprotectin (CP;4 S100A8/S100A9 or MRP8/MRP14 oligomer), a metal-sequestering protein well-known for withholding Mn(II) and Zn(II), coordinates Fe(II) with high affinity and has the capacity to inhibit microbial iron acquisition under reducing conditions (9). This initial work allowed us to propose a new hypothesis that CP is an unrecognized player in the iron-withholding innate immune response in reducing or anaerobic environments where Fe(II) is available. Nevertheless, this initial study did not directly link the observed inhibition of iron acquisition to host-defense function because the 55Fe-uptake assay designed and used was performed under conditions where CP did not exert bacteriostatic activity (9). Moreover, this study did not examine the consequences of Fe(II) sequestration by CP on microbial physiology and iron homeostasis pathways.

The antimicrobial activity of CP has historically only been attributed to its ability to sequester two essential metals, manganese and zinc; however, in addition to our study of Fe(II), recent work has revealed that CP is also capable of withholding additional nutrient metals, including nickel and copper (10). Taken together, these studies indicate that CP is functionally versatile, that the metal ions sequestered by CP must be considered on a case-by-case basis, and that CP function will depend on metal availability at an infection site. From a structural standpoint, CP is a heterooligomer of the Ca(II)-binding polypeptides S100A8 and S100A9. Each CP heterodimer has two transition metal–binding sites that form at the S100A8/S100A9 interface: a His3Asp motif (site 1) and a His6 motif (site 2) (11–14). The unusual His6 motif provides CP with its functional versatility; this site captures Fe(II) and other divalent metal ions, including Mn(II), Ni(II), and Zn(II) (9, 10).

Prior to our observations that CP chelates Fe(II) and can inhibit microbial iron uptake, several published reports indicated that CP cannot bind iron and thus concluded that the protein cannot be involved in iron homeostasis (12, 15). Moreover, murine model studies reported to date have not provided evidence for an Fe(II)-withholding function for CP (15–18). As a result, our initial report of Fe(II) withholding by CP and a new hypothesis sparked some debate in the literature, and several publications posited that Fe(II) binding by CP is irrelevant to its antimicrobial activity (19–21). The uncertainty surrounding the role of CP in iron homeostasis has arisen from these factors as well as the fact that Fe(II) is highly susceptible to oxidation to form Fe(III) under aerobic or oxidative conditions (22). Our initial study found that CP has negligible affinity for Fe(III) (9), indicating that it cannot sequester Fe(III) from microbes. Thus, our early analyses suggested that CP-mediated limitation of iron would only occur in anaerobic or reducing environments where we expect Fe(II) to be the dominant oxidation state. Nonetheless, more recent work has shown that CP stabilizes the Fe(II) oxidation state and shifts the redox speciation of iron from Fe(III) to Fe(II) under aerobic conditions and in the absence of an exogenous reductant (23). We also obtained preliminary evidence that microbial metabolites that affect iron speciation in solution, in particular Fe(III)-sequestering siderophores and redox-cycling phenazines, can enhance or inhibit Fe(II) sequestration by CP under aerobic conditions (23). As a result of these findings, we revised our initial hypothesis and reasoned that Fe(II) sequestration by CP may also occur in aerobic environments.

To address the hypothesis that CP can withhold Fe(II) and affect microbial iron homeostasis pathways under aerobic conditions, we examined the consequences of Fe(II) withholding by CP on the physiology and virulence potential of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an opportunistic bacterial pathogen that has a high metabolic iron requirement. CP levels are markedly increased in advanced cystic fibrosis (CF) lung disease, a hereditary disease characterized by reduced lung function and chronic P. aeruginosa infection (24–26). P. aeruginosa is adept at overcoming host-mediated iron deprivation and expresses several machineries for acquiring Fe(II) and Fe(III) ions as well as heme during infection (27, 28). Iron depletion also induces expression of the PrrF small regulatory RNAs, which reduce the metabolic requirement of P. aeruginosa for iron when this nutrient is limiting (29). This process, referred to as the iron-sparing response (30), is central to P. aeruginosa survival during iron starvation and is therefore required for successful infection (31). As intracellular iron increases, the ferric uptake regulator (Fur) represses genes encoding iron acquisition systems and the PrrF sRNAs (32). Within the CF lung, P. aeruginosa becomes more reliant on Fe(II) by lowering production of Fe(III)-scavenging siderophores and increasing production of redox-cycling phenazines that can reduce extracellular Fe(III) to Fe(II) (27, 33, 34). Taken together with the colocalization of P. aeruginosa and CP in the CF lung (16), P. aeruginosa provides an excellent model for evaluating the effect of CP on iron-dependent processes that include growth, metabolite production, and virulence potential.

In this work, we report that CP affects multiple iron-dependent processes in P. aeruginosa. CP prevents iron uptake and induces an iron starvation response by this pathogen. Moreover, we describe a role for phenazines in CP-mediated iron starvation, and we demonstrate that P. aeruginosa responds to CP by altering the production of iron-regulated virulence traits. Lastly, we look beyond P. aeruginosa and demonstrate that CP can inhibit iron uptake by a range of bacterial pathogens. Together, this work shows that Fe(II) sequestration by CP impacts iron homeostasis in multiple pathogens and supports a role for Fe(II) withholding in nutritional immunity.

Results

CP inhibits iron uptake by P. aeruginosa

To evaluate how CP affects metal levels in P. aeruginosa, we quantified cell-associated manganese, iron, nickel, copper, and zinc in two commonly used strains, PAO1 and PA14 (Table S1), grown in the absence or presence of CP (10 μm; ∼260 μg/ml). We performed these studies with WT CP and a variant with two Cys → Ser point mutations (S100A8(C42S)/S100A9(C3S)) termed CP-Ser (Table S3) (14). The mutated Cys residues are distant from the His3Asp and His6 sites, and WT CP and CP-Ser display comparable antimicrobial activities (14). We decided to use CP-Ser throughout this work because it was used for the majority of reported metal-binding and antimicrobial activity studies of CP. We also performed key experiments with WT CP and in all cases found that both proteins elicited similar results. We cultured PAO1 and PA14 in Tris/tryptic soy broth (TSB), a buffered medium commonly used in antimicrobial activity studies of CP. Throughout this work, Tris/TSB contains a 2 mm Ca(II) supplement and no exogenous reducing agent (e.g. β-mercaptoethanol (βME)). Inductively coupled plasma (ICP)-MS showed that this medium contained ∼4 μm iron (Table S4). Following aerobic growth (8 h at 37 °C), we collected the P. aeruginosa cells and quantified the cell-associated metal levels by ICP-MS (Fig. S1). We observed that CP-Ser and WT CP caused an ∼1.5-fold reduction in cell-associated iron for PAO1 and PA14 compared with the untreated control, in agreement with previously reported inhibition of P. aeruginosa iron uptake by CP-Ser (Fig. 1A and Fig. S2) (9). The current data show, for the first time, CP-mediated inhibition of iron uptake under aerobic conditions in the absence of an exogenous reductant. A reduction in cell-associated manganese, but not nickel, copper, or zinc, was also observed for both strains (Fig. S3).

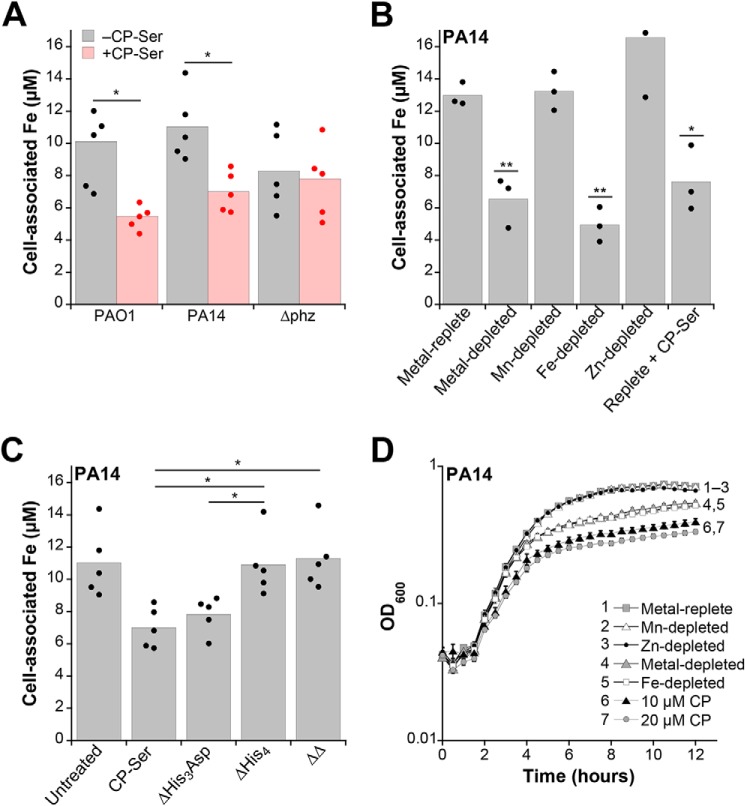

Figure 1.

CP inhibits iron uptake and growth by P. aeruginosa in aerobic culture. A, cell-associated iron for PAO1, PA14, and PA14 Δphz grown in Tris/TSB in the absence or presence of CP-Ser (10 μm) (n = 5; *, p < 0.05). B, cell-associated iron in PA14 grown in metal-depleted Tris/TSB in the absence or presence of CP-Ser (10 μm) (n = 3; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 for comparison with the replete condition). C, cell-associated iron in PA14 grown in Tris/TSB in the absence or presence of CP-Ser, ΔHis3Asp, ΔHis4, or ΔΔ (10 μm) (n = 4; *, p < 0.05). For comparison with the untreated culture condition, p < 0.05 for CP-Ser and ΔHis3Asp. A–C, cultures were grown at 37 °C for 8 h. Cell-associated metal levels correspond to the concentration of metal in a liquefied suspension of cells at an A600 of 10. D, PA14 exhibits a growth defect in iron-depleted Tris/TSB and in the presence of CP-Ser (10 or 20 μm). PA14 was grown at 37 °C for 12 h (n = 3; error bars represent S.E.).

Next, we evaluated the cell-associated iron levels in PA14 grown in iron-depleted, manganese-depleted, or zinc-depleted Tris/TSB (Table S5 and Fig. 1B). PA14 cultured in iron-depleted medium showed an ∼3-fold decrease in cell-associated iron, whereas a negligible change was observed for bacteria cultured in the manganese-depleted or zinc-depleted medium (Fig. 1B). Thus, the similar decrease in cell-associated iron when PA14 is cultured with CP-Ser and in iron-depleted medium indicates that CP is preventing iron uptake by P. aeruginosa via iron sequestration.

The His6 site is required for inhibition of iron uptake by P. aeruginosa

The His6 site is the high-affinity Fe(II) site (9), and we hypothesized that CP requires this site to withhold iron from P. aeruginosa. We analyzed the cell-associated iron levels of PA14 after growth in the presence of CP-Ser variants that lack one (ΔHis3Asp or ΔHis4) or both (ΔΔ) metal-binding sites (Table S3). Like CP-Ser and WT CP, ΔHis3Asp treatment reduced cell-associated iron levels, whereas ΔHis4 or ΔΔ had negligible effect (Fig. 1C). Thus, the His6 site is required for CP to inhibit iron uptake by P. aeruginosa.

CP and iron depletion inhibit growth of P. aeruginosa

In prior work, we observed attenuated PAO1 growth in the presence of CP-Ser and in iron-depleted Tris/TSB (9). These experiments were performed at 30 °C in Tris/TSB supplemented with βME as this reducing agent is commonly added to growth media used in studies of CP (9, 14). Guided by the metal-uptake studies described above, we reanalyzed the growth-inhibitory activity of CP-Ser and the metal dependence of P. aeruginosa growth at 37 °C and in the absence of an exogenous reductant. Under these conditions, CP-Ser inhibited growth of PAO1 and PA14 (Fig. 1D and Fig. S4). Attenuated P. aeruginosa growth also occurred in iron-depleted Tris/TSB but not in manganese- or zinc-depleted medium (Fig. 1D and Fig. S4). Thus, although CP-Ser inhibited manganese uptake by PAO1 and PA14 during growth in Tris/TSB (Fig. S3), Mn(II) withholding alone cannot account for the growth-inhibitory activity of CP against P. aeruginosa under these conditions.

Phenazines enhance CP-mediated inhibition of iron uptake

Phenazines are redox-cycling secondary metabolites that P. aeruginosa secretes into the extracellular space. By reducing extracellular Fe(III) to Fe(II), phenazines make Fe(II) available as an iron source for P. aeruginosa in environments where Fe(III) normally predominates (35). To ascertain whether phenazines produced by P. aeruginosa promote Fe(II) withholding by CP in culture, we examined cell-associated iron levels in a Δphz mutant of PA14 lacking the operons phzA1-G1 and phzA2-G2 (Table S1) (36). The enzymes encoded by phzA1-G1 and phzA2-G2 catalyze the conversion of chorismate to phenazine-1-carboxylate (PCA), which is a biosynthetic precursor to other phenazines including pyocyanin (PYO). Thus, the Δphz mutant cannot produce phenazines (Fig. S2). Following growth in Tris/TSB, Δphz exhibited no reduction of cell-associated iron when CP-Ser or WT CP was added to the medium (Fig. 1A and Fig. S2). Moreover, a similar reduction of manganese and zinc uptake following treatment with CP-Ser was observed for Δphz and PA14 (Fig. S3). We note that the Δphz strain exhibits reduced cell-associated iron levels compared with the parent strain, which we reason is due to the pleiotropic roles of phenazines in signaling (36), redox homeostasis (37), metabolism (38, 39), and iron acquisition (40). The Δphz mutant is therefore expected to have an altered baseline requirement for iron, leading to altered cellular iron levels compared with the parent strain. Overall, these results suggest that phenazine production enhances CP-mediated iron withholding from P. aeruginosa. This finding provides physiological relevance to prior work, which demonstrated that phenazines enhance the iron-depleting activity of CP in aerobic solution (23).

CP promotes pyoverdine production

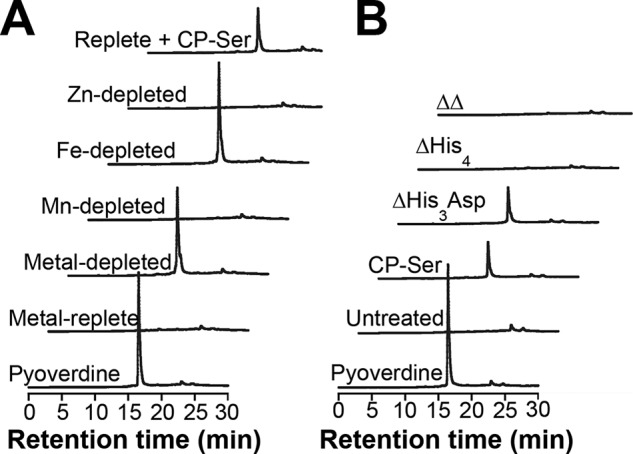

We next questioned whether Fe(II) withholding by CP induces an iron starvation response in P. aeruginosa. When confronted with iron limitation, P. aeruginosa biosynthesizes and exports the fluorescent siderophore pyoverdine (41). In preliminary studies, we observed that supernatants from CP-treated cultures of P. aeruginosa were more fluorescent than untreated cultures. To further investigate whether P. aeruginosa responds to CP by producing pyoverdine, we measured pyoverdine levels in the supernatants of P. aeruginosa cultures grown in the absence or presence of CP-Ser by fluorescence spectroscopy. Supernatants from cultures of the pyoverdine biosynthesis mutant PAO1 ΔpvdA (±CP-Ser) exhibited negligible fluorescence (Table S1 and Fig. S5). An ∼10-fold increase in pyoverdine emission occurred when PAO1 and PA14 were cultured in the presence of CP-Ser compared with the untreated cultures (Fig. S5). Thus, CP causes P. aeruginosa to boost pyoverdine production, indicative of an iron starvation response. Although pyoverdine biosynthesis is primarily regulated by Fur, its levels can be affected by other metal ions (42, 43). To evaluate the role of other metal ions, we monitored pyoverdine levels in the supernatants of cultures grown in Tris/TSB depleted of manganese, iron, or zinc by analytical high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) alongside a purified standard (Fig. S6), which provided more reliable quantification of pyoverdine levels than fluorescence spectroscopy. We found that iron depletion, but not manganese or zinc depletion, promoted pyoverdine production (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, enhanced pyoverdine production was observed for PA14 grown in the presence of CP-Ser, WT CP, or ΔHis3Asp but not ΔHis4 or ΔΔ (Fig. 2B and Fig. S7). Taken together, these results indicate that P. aeruginosa responds to CP by increasing pyoverdine production, and the His6 site of CP elicits this response by sequestering Fe(II).

Figure 2.

Iron depletion and Fe(II) sequestration by CP promote pyoverdine production. A and B, HPLC fluorescence detection (λex = 398 nm, λem = 455 nm) for supernatants from PA14 grown in Tris/TSB in the absence or presence of CP-Ser (10 μm) (A) and PA14 grown in Tris/TSB in the absence or presence of CP-Ser, ΔHis3Asp, ΔHis4, and ΔΔ (B). Cultures were grown at 37 °C for 8 h. Three biological replicates were performed, and representative chromatograms are shown. Average culture A600 values ranged from 1.6 to 2.6 (Table S6).

In response to low intracellular iron levels, Fur derepresses the transcription of pvdS, a gene that encodes a σ factor necessary for inducing expression of genes for pyoverdine biosynthesis (44). By inhibiting iron uptake, we expected that CP induces pyoverdine production via activation of pvdS transcription. We analyzed transcript levels of pvdS in PAO1 by qPCR to determine whether CP increases transcription of this key mediator of the iron-dependent pathway that induces pyoverdine production. Cultures for this qPCR analysis were grown in a chemically defined medium (CDM) due to difficulties obtaining reproducible qPCR data in the more nutrient–depleted Tris/TSB medium. In CDM, CP induces pyoverdine production in PAO1 similarly to that observed in Tris/TSB (Fig. S8). Moreover, transcript levels of pvdS increase by a factor of ∼2.2 after growth in the presence of CP-Ser compared with the untreated control (Fig. S8), suggesting that iron starvation by CP leads to increased production of PvdS, which in turn promotes pyoverdine biosynthesis.

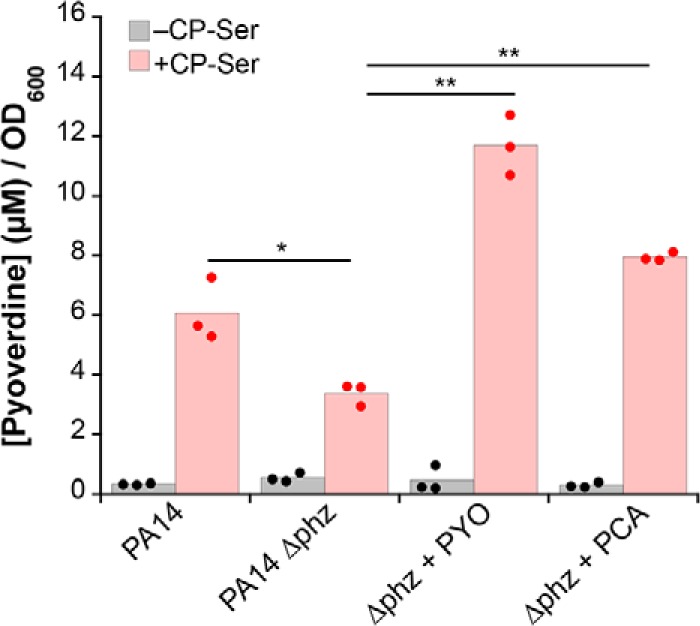

Phenazines enhance CP-mediated induction of pyoverdine production

We next probed whether phenazines affect the ability of CP to induce pyoverdine biosynthesis in P. aeruginosa. Supernatants of PA14 and Δphz grown without CP contained ∼0.4 μm pyoverdine after normalization to the culture A600. In the presence of CP-Ser, normalized pyoverdine levels in the PA14 and Δphz supernatants increased to ∼6 and ∼3.5 μm, respectively (Fig. 3). Moreover, the normalized pyoverdine levels in CP-Ser–treated cultures of Δphz grown in Tris/TSB supplemented with 20 μm PYO or PCA increased to ∼12 and ∼8 μm, respectively (Fig. 3). Because the Δphz mutant contains the biosynthetic enzymes that can modify PCA, the PCA supplement may restore the ability of Δphz to produce PYO. Thus, PYO may also be an active reductant following supplementation with PCA. Overall, these data indicate that phenazines enhance the Fe(II)-sequestering activity of CP and, as a result, promote an increase in pyoverdine production by P. aeruginosa.

Figure 3.

Phenazines enhance CP-induced pyoverdine production. Pyoverdine was quantified in supernatants from PA14 and Δphz cultures grown in Tris/TSB in the absence or presence of CP-Ser (10 μm) and PYO or PCA (20 μm) at 37 °C for 8 h. Concentrations were normalized to culture A600, which ranged from 1.8 to 2.9 (n = 3; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01).

CP inhibits antR translation

As a second, independent readout for iron starvation in P. aeruginosa, we measured activity of an iron-responsive translational reporter for antR, which encodes an activator of genes for anthranilate catabolism. In low-iron conditions, translation of antR mRNA is repressed by the PrrF sRNAs; in high-iron conditions, expression of the PrrF sRNAs is repressed by Fur, allowing translation of antR (32, 45). We grew the PAO1 antR translational reporter strain (PAO1/PantR-′lacZ−SD; Table S1) in Tris/TSB or CDM either in the absence or presence of CP-Ser and observed decreased reporter activity in response to ≥10 μm CP as determined by β-gal assay (Fig. 4A and Fig. S8). Furthermore, we observed that CP-Ser does not reduce antR translation effectively in the ΔprrF/PantR-′lacZ−SD strain (Fig. 4A and Fig. S8), consistent with CP regulation of antR being mediated by the iron-responsive PrrF sRNAs. Analysis of the metal dependence of antR translation in these strains indicated that PAO1 antR translation is responsive to iron depletion but not manganese or zinc depletion and that the ΔprrF strain does not reduce antR translation in response to iron depletion as effectively as PAO1, as has been observed previously (Fig. S9) (46). We also introduced the antR translational fusion onto the chromosomes of PA14 and PA14 Δphz and observed that both are responsive only to iron depletion (Table S1 and Fig. S9). Consistent with the PAO1 reporter strain, the PA14/PantR-′lacZ−SD strain showed decreased reporter activity in response to ≥10 μm CP-Ser (Fig. 4B). To ascertain whether phenazines enhance the response of the antR translational reporter strain to CP, we also examined PA14 Δphz/PantR-′lacZ−SD. Indeed, ≥10 μm CP-Ser elicited less response in PA14 Δphz/PantR-′lacZ−SD than in PA14/PantR-′lacZ−SD (Fig. 4B). Taken together, these data indicate that CP induces iron starvation via PrrF-mediated repression of antR and that this activity is enhanced in the presence of phenazines.

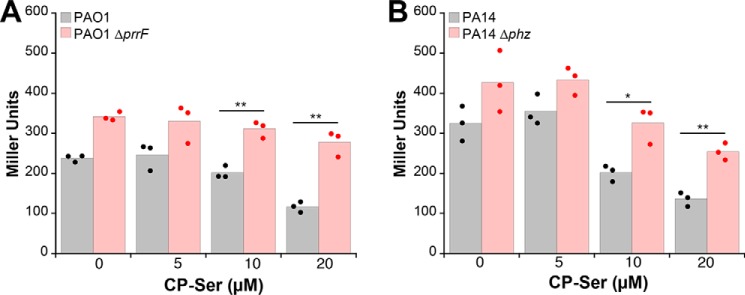

Figure 4.

CP inhibits AntR translation. P. aeruginosa PAO1/PantR-′lacZ−SD and ΔprrF/PantR-′lacZ−SD (A) and PA14/PantR-′lacZ−SD and PA14 Δphz/PantR-′lacZ−SD (B) were grown in Tris/TSB in the absence or presence of 5, 10, or 20 μm CP-Ser at 37 °C for 8 h. β-Galactosidase activity was assayed in cell suspensions (n = 3; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). For comparison with untreated cultures of PAO1 and PA14, p < 0.05 for 10 μm CP-Ser and p < 0.01 for 20 μm CP-Ser. For comparison with untreated culture of Δphz and ΔprrF, p < 0.05 for 20 μm CP-Ser treatment.

CP inhibits phenazine production

Early on, we observed that P. aeruginosa cultures treated with CP lost the characteristic blue color indicative of PYO, suggesting that CP inhibits the production of this secondary metabolite. To further investigate whether CP affects phenazine production, we detected PYO and PCA in PAO1 and PA14 culture supernatants by analytical HPLC and quantified levels of these two phenazines in the supernatants of cultures grown in the absence or presence of CP-Ser or WT CP (Fig. S10). Treatment of PAO1 and PA14 with either protein resulted in a ∼10-fold decrease in PCA and PYO levels compared with the untreated control, suggesting that P. aeruginosa responds to CP by decreasing production of these two metabolites (Fig. 5A and Fig. S11). To evaluate how CP affects phenazine levels, we first quantified PYO and PCA in supernatants from cultures grown in Tris/TSB depleted of manganese, iron, zinc, or all three metals. Iron depletion, but not manganese or zinc depletion, inhibited phenazine production by P. aeruginosa (Fig. 5B). This analysis indicates that the reduction of phenazine biosynthesis by P. aeruginosa is a consequence of iron limitation and thus Fe(II) withholding by CP.

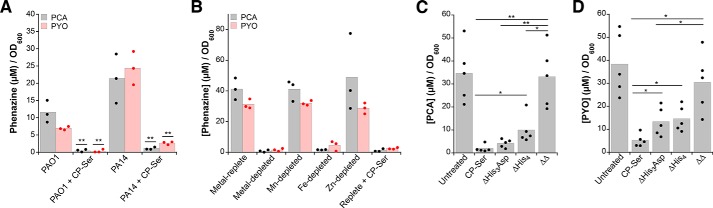

Figure 5.

CP and iron depletion inhibit phenazine production. A, average PYO and PCA concentrations in supernatants from P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14 cultures grown in the absence or presence of 10 μm CP-Ser (n = 3; **, p < 0.01). B, average PYO and PCA concentrations in supernatants from PA14 cultures grown in metal-depleted Tris/TSB supplemented with the indicated metals in the absence or presence of 10 μm CP-Ser (n = 3). For comparison with the replete condition, p < 0.01 for PYO and PCA levels in depleted, iron-depleted, and replete + CP-Ser conditions. C and D, effect of CP variants on phenazine production. Average PCA (C) and PYO (D) concentration in supernatants from PA14 cultures grown in the absence or presence of 10 μm CP-Ser, ΔHis3Asp, ΔHis4, or ΔΔ (n = 3; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). For comparison with the untreated condition, p < 0.01 for CP-Ser, ΔHis3Asp, and ΔHis4 (C) and p < 0.01 for CP-Ser and p < 0.05 for ΔHis3Asp and ΔHis4 (D). A–D, cultures were grown at 37 °C for 8 h. Supernatants were analyzed by HPLC alongside a standard curve, and integrated phenazine peak areas (absorption at 365 nm) were converted to concentration. Phenazine concentrations were normalized to the A600 of their respective cultures. Culture A600 ranged from 1.6 to 3.1.

We next examined how each metal-binding site contributes to this phenomenon by quantifying phenazine levels in supernatants of PA14 cultures treated with ΔHis3Asp, ΔHis4, or ΔΔ (Fig. 5, C and D). As anticipated, cultures treated with ΔΔ exhibited PCA and PYO levels comparable to those of the untreated control. Moreover, treatment of PA14 with ΔHis3Asp reduced both PCA and PYO levels to concentrations similar to those observed after treatment with CP-Ser or WT CP (Fig. 5, C and D, and Fig. S11). This result also agreed with our expectations because the His6 site sequesters Fe(II). The ΔHis4 variant, however, elicited an unexpected response from P. aeruginosa. Although ΔHis4 had negligible effect on the levels of PCA, reduced levels of PYO were detected following treatment of PA14 with this variant (Fig. 5, C and D). Taken together, these data indicate that a link between iron availability and phenazine biosynthesis exists and that CP treatment inhibits phenazine production, at least in part, by limiting iron availability. It also appears that the His3Asp site affects phenazine levels, albeit to a lesser extent than the His6 site. Regulation of phenazines is complex and is likely not directly regulated by iron because no obvious Fur or PrrF regulatory sites are identified upstream of the phz1 and phz2 operons. How the His6 and His3Asp sites of CP and, and more generally, metal ion levels affect phenazine production certainly warrants further investigation.

Toward elucidating the mechanism by which iron restriction and CP inhibit phenazine production, we questioned an indirect role of PrrF sRNAs in this response. By regulating AntR levels, PrrF sRNAs affect the sourcing of anthranilate to production of 2-alkyl-4(1H)-quinolones (AQs) or to its catabolic degradation in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (45). Recent work has revealed that phenazine production is closely tied to both AQ levels and nutrient-regulated metabolic activity of P. aeruginosa (38, 47). Thus, we hypothesized that PrrF sRNAs may be critical mediators for CP-mediated inhibition of phenazine production. To evaluate the involvement of PrrF in CP-mediated inhibition of phenazine production, we measured PYO and PCA in cultures of PAO1 ΔprrF grown in the absence or presence of CP-Ser (Fig. S12). CP remained capable of inhibiting phenazine production in the ΔprrF strain, suggesting that the PrrF sRNA–directed iron-sparing response is not essential for CP to inhibit phenazine production. Thus, the mechanism by which CP and iron regulate phenazine levels is unresolved and requires further investigation.

Low levels of phenazines are sufficient to enhance Fe(II) sequestration by CP

Our metal uptake, pyoverdine, and antR translation studies indicated that phenazines enhance CP-mediated iron starvation. After observing that CP reduces phenazine production, we questioned whether low concentrations of phenazines are sufficient to promote Fe(II) sequestration by CP. We therefore evaluated the iron-depleting activity of CP-Ser in Tris/TSB medium in the absence and presence of 5 μm PYO. This concentration is representative of the unnormalized PYO levels detected in PA14 culture supernatants when the bacteria were grown in the presence of 10 μm CP-Ser or WT CP. The 5 μm PYO supplement enhanced iron depletion of Tris/TSB by CP-Ser (Fig. 6A). This result is consistent with a prior study where PYO, albeit at a higher concentration, enhanced the iron-depleting activity of CP-Ser (23). Because prior work also showed that bacterial siderophores such as enterobactin and staphyloferrin B attenuated iron depletion by CP under aerobic conditions (23), we evaluated this activity for pyoverdine and found that 2 μm pyoverdine inhibited iron depletion by CP-Ser (Fig. 6B). Even at relatively low levels, both phenazines and siderophores utilized by P. aeruginosa alter the ability of CP to capture Fe(II), demonstrating the ability of bacterial metabolites to modulate the activity of CP.

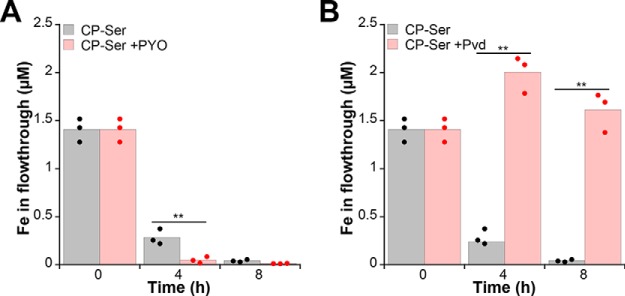

Figure 6.

P. aeruginosa metabolites affect iron depletion by CP. Tris/TSB was supplemented with 10 μm CP-Ser in the absence or presence of 5 μm PYO (A) or 2 μm pyoverdine (Pvd) (B) and incubated at 37 °C. At 4 and 8 h, CP-Ser was filtered out, and the metal content in the flow-through was analyzed by ICP-MS. The t = 0 h time point corresponds to filtered media before any CP, PYO, or pyoverdine supplementation and is thus the same for each condition (n = 3; **, p < 0.01).

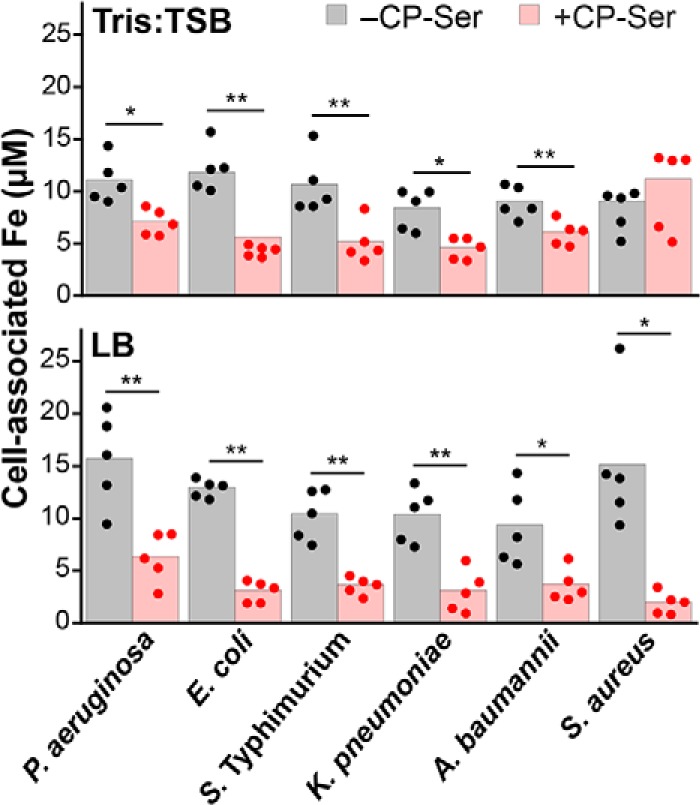

CP inhibits iron uptake by multiple bacterial pathogens

Our studies of P. aeruginosa prompted us to evaluate how CP affects iron levels in other bacterial pathogens. We examined cell-associated metal content of four additional Gram-negative and one Gram-positive species. In Tris/TSB, CP-Ser treatment afforded a significant decrease in cell-associated iron for all Gram-negative bacterial strains but not for the Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus USA300 JE2 (Fig. 7). Cell-associated manganese, nickel, copper, and zinc levels also decreased for some, but not all, of the species included in this screen (Fig. S13). Because metal speciation and bacterial metabolism can differ depending on medium conditions, we repeated this experiment in Luria-Bertani medium (LB), which contains ∼8 μm iron (Table S7). After growth in LB, P. aeruginosa PA14 accumulated ∼12 μm iron, which corresponds to ∼6 × 105 iron atoms/cfu. This result is similar to previous elemental analysis of P. aeruginosa PAO1 after growth in LB (Fig. 7) (49). When grown in the presence of CP-Ser, a reduction of cell-associated iron was observed for all six pathogens (Fig. 7). Changes to cell-associated manganese, nickel, copper, and zinc in the presence of CP-Ser were similar to those observed in Tris/TSB (Fig. S13). Taken together, these results highlight the functional versatility of CP and underscore that metal withholding must be examined on a case-by-case basis. From the standpoint of Fe(II) withholding, these data show that CP-Ser inhibits iron uptake by a diverse set of bacteria grown in aerobic culture and in the absence of an exogenous reductant like βME. Moreover, reduction in cell-associated iron occurred for all organisms examined, whereas decreased levels of other metals, including manganese and zinc, occurred less frequently. Indeed, the cell-associated “metal inventory” for these six bacteria illuminates the variable effects of CP on different bacterial species (Fig. S13). The data also reveal notable differences in metal uptake in different growth media. In particular, the effect of CP on iron uptake by S. aureus varies tremendously depending on the medium because extensive inhibition of iron uptake by S. aureus was observed in LB, whereas negligible change occurred in Tris/TSB. Along these lines, metal inventory data from studies of the competition between CP and S. aureus showed that CP only reduced manganese acquisition by S. aureus strain Newman following growth in TSB or Tris/TSB (20, 50). Taken together, these data indicate the importance of considering the effect of growth conditions on bacterial metabolism in studies of CP and, more broadly, nutritional immunity.

Figure 7.

Analysis of cell-associated iron levels shows that CP inhibits iron uptake by several bacterial pathogens during aerobic culture. Bacteria (Table S1) were grown in Tris/TSB or LB in the absence or presence of 10 μm CP-Ser (in Tris/TSB) or 20 μm CP-Ser (in LB) at 37 °C for 8 h. Cell-associated iron corresponds to the concentration of iron in an A600 = 10.0 cell suspension (n = 5; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). The P. aeruginosa strain used was PA14.

Discussion

Nutritional immunity was first conceptualized to explain Fe(III) withholding by the host during infection (2). Explorations of the battles between host and microbial pathogens for Fe(III) have led to many important discoveries, including the roles of the host proteins lactoferrin and lipocalin-2 in Fe(III) withholding and the elucidation of microbial Fe(III) acquisition systems that can overcome host-mediated Fe(III)-withholding strategies (1). Many bacterial pathogens also acquire heme as an iron source (51), and complex pathways of microbial heme uptake and utilization during infection compete with the heme-binding host proteins haptoglobin and hemopexin (51, 52). In contrast to Fe(III) and heme, the battle for Fe(II) between host and pathogen was overlooked for many years. The prevalence of Fe(II) at infection sites and the importance of Fe(II) acquisition for microbial pathogenesis have only been recognized recently (7, 8). Several murine models of infection, including P. aeruginosa lung infection, have indicated the essentiality of Fe(II) uptake via the Feo transport system (8). Furthermore, the development and application of new tools to image Fe(II) ions during infection at the organismal level recently revealed that Fe(II) localizes to infected tissues (53). Despite these reports that provide compelling evidence for the importance of Fe(II) in microbial pathogenesis, a means for Fe(II) limitation by the host remained unidentified until 2015. We discovered that CP, a protein well-known for sequestering Mn(II) and Zn(II), has remarkable high affinity for Fe(II) (9). In our current work, we address the gap in our understanding of host-mediated Fe(II) limitation and report that CP inhibits iron uptake by a variety of bacterial pathogens. Previous work has shown that CP can inhibit iron uptake by Escherichia coli and P. aeruginosa under reducing conditions where Fe(II) is expected to predominate (9, 54). The current study indicates similar activity in an aerobic environment and in the absence of an exogenous chemical reductant where Fe(III) is expected to be most abundant. Together, these studies indicate that the battle for Fe(II) between CP and a variety of microbes is likely relevant in diverse environments that have highly variable oxygen levels.

For P. aeruginosa in particular, we show that CP elicits several physiological responses via Fe(II) sequestration. We report that CP increases biosynthesis of the siderophore pyoverdine, inhibits antR translation, and reduces production of PYO and PCA. These results agree with CP-induced changes to pyoverdine and phenazine levels that were observed previously (16). However, the previous report concluded that CP affects levels of these metabolites via manganese or zinc sequestration (16). At the time, this conclusion was in accord with a prevailing notion that CP sequesters only Mn(II) and Zn(II). In light of our discovery that CP chelates Fe(II), and with higher affinity than Mn(II), at the His6 site (9), we evaluated the metal dependences of these observations and arrived at a different conclusion. The current work attributes induction of pyoverdine production, inhibition of antR expression, and inhibition of phenazine biosynthesis to CP-mediated iron starvation. By altering signaling pathways involving these molecules and others, it is likely that CP-mediated iron starvation drastically alters the virulence of P. aeruginosa, and we further consider this notion below.

Pyoverdine regulates virulence factor production via a signaling cascade that originates with recognition of ferric pyoverdine by its outer membrane receptor, FpvA. Upon recognition of ferric pyoverdine, FpvA activates the σ factor PvdS, which initiates transcription of pyoverdine biosynthesis genes and two virulence factors, endoprotease PrpL and exotoxin A (55). Down-regulation of AntR by the PrrF sRNAs also promotes the production of virulence factors by preventing anthranilate degradation, which is a precursor for several AQs produced by P. aeruginosa (45). One of these AQs, 2-heptyl-4-hydroxyquinoline N-oxide, is growth-inhibitory toward S. aureus, a competing pathogen for P. aeruginosa during early stages of CF lung infection (56). Thus, our analysis of the effect of CP on pyoverdine production and antR translation suggests that CP enhances the expression of some P. aeruginosa virulence traits.

In contrast, our studies of the effect of CP on phenazines indicate that CP may reduce expression of other P. aeruginosa virulence traits. PYO and PCA play several roles in P. aeruginosa biology by promoting biofilm formation, extracellular oxidative stress, intracellular generation of ATP, and quorum sensing (36, 37, 40, 57). In particular, PCA promotes biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa by enhancing Feo-mediated Fe(II) acquisition (40). Because phenazines aid iron uptake, it is possible that CP reduces P. aeruginosa iron acquisition in part by inhibiting phenazine biosynthesis and thus compromising Fe(II) uptake by this organism. This possibility and, more broadly, the implications of CP-mediated inhibition of phenazine production for P. aeruginosa viability and virulence warrant further investigation. CP has been detected at concentrations as high as 40 μm (1 mg/ml) in the extracellular space, and its levels correlate with disease severity of CF lung infections (58, 59). Previously, investigations using an airway infection model of coinfection by the CF pathogens S. aureus and P. aeruginosa in WT and CP-deficient mice indicated that the presence of CP did not significantly reduce P. aeruginosa cfu in the murine lung (16). We reason that this study does not preclude the possibility of CP affecting P. aeruginosa growth and virulence in vivo. It is possible that this observation is model-dependent and that a different outcome will occur in a different infection type or under different physiological circumstances. Furthermore, CP may alter P. aeruginosa virulence in a manner independent of growth inhibition and may elicit a much different phenotype in other contexts such as during monoinfection of P. aeruginosa or chronic infection that has not yet been captured using murine models of infection. We also note that the repertoire of host-defense factors found in mice and humans varies, and differences between murine CP and human CP exist (60). For these reasons, it is also possible that CP functions in humans and mice differently.

Our study of the competition between CP and P. aeruginosa also illuminates a novel function of phenazines: the capacity to enhance CP-induced iron starvation. We further show that CP inhibits phenazine production; however, only low levels of PYO are necessary to enhance iron depletion by CP. We note that although phenazines aid CP-mediated inhibition of iron uptake, they are not essential for CP to induce an iron starvation response by P. aeruginosa. Indeed, CP is still capable of up-regulating pyoverdine production and inhibiting antR translation in the PA14 Δphz strain, indicative of iron starvation in this nonphenazine-producing strain. Although the current work suggests that phenazines enhance the efficacy of the innate immune response toward P. aeruginosa, phenazines are also known to be necessary for full virulence in the mammalian host (47) and impart several beneficial functions for the producer, including pathogenic effects on human tissues (61) and the promotion of mineral reduction for soil-dwelling pseudomonads (62). Thus, we reason that aiding the innate immune system is not an intended or evolved role of phenazines. Future studies in mammalian infection models should take into account the impact of phenazines on the competition between CP and P. aeruginosa for iron.

The current study and previous work have indicated a contrasting role for microbial siderophores, which can prevent Fe(II) chelation by CP when Fe(III) is the dominant redox state (23). Broadly, these results highlight that microbial metabolites can alter host defense by tuning the extracellular environment to either promote or attenuate Fe(II) sequestration by CP. Every organism has a unique metabolic profile and may adapt metabolite production based on nutrient availability. Accordingly, our organism screen data indicate that metal withholding by CP varies by species and growth condition. Thus, both our studies of P. aeruginosa metabolites and our organism screen data reveal a complex interplay between CP and microbes that will require further elucidation on a case-by-case basis.

In closing, this work addresses the role of CP in an overlooked facet of nutritional immunity: the battle for Fe(II). There is extensive evidence for the presence and microbial utilization of Fe(II) at infection sites, and the current work indicates that the innate immune protein CP limits availability of this metal ion and thereby impacts gene expression, metabolic networks, and virulence potential. This work provides a foundation for future studies directed at elucidating how this abundant innate immune protein affects iron physiology in a diversity of human pathogens and infection models.

Experimental procedures

General materials and methods

Solutions and buffers

All chemicals were acquired from commercial suppliers and used as received. All solutions were prepared using Milli-Q water (18.2 megaohms·cm). All buffer solutions were filtered (0.2 μm) before use. Stock solutions of metal ions were prepared in acid-washed volumetric glassware by dissolving 99.99% CaCl2 (1.0 m), 99.999% MnCl2 (100 mm), 99.997% (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2·6H2O (100 mm), and 99.999% anhydrous ZnCl2 (1.0 m) (Sigma) into water and transferring the solutions to polypropylene containers. For stock solutions of Fe(II), (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2·6H2O powder was transferred into a glove box, dissolved with deoxygenated Milli-Q water, and stored in the glove box. Ultrapure Tris (VWR) was used to prepare Tris/TSB medium.

General CP methods

CP-Ser was used in this work because it has been more extensively evaluated in both metal-binding studies and microbiology studies than the WT protein. In multiple experiments presented in this work, CP-Ser and WT CP were compared and shown to display the same behavior. The CP heterodimer and its variants (Table S3) were prepared and stored as described previously (14). For CP-Ser preparations used in the current work, the overexpression was performed on an 8-liter scale using 4 liters of S100A8(C42S) and 4 liters of S100A9(C3S) overexpression cultures. At this 8-liter scale, the yield of CP-Ser ranged from 150 to 200 mg/8-liter culture. In some cases, CP-Ser was dialyzed into 20 mm Tris, 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.5 at the final step in its purification and stored in this buffer. Protein aliquots were thawed only once, immediately prior to use. If stored in the standard purification buffer (20 mm HEPES, 100 mm NaCl, pH 8.0, for CP-Ser and the metal-binding site variants; for WT CP, the buffer also contained 5 mm DTT), the protein was buffer-exchanged three times into 20 mm Tris, 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.5 using presterilized 0.5-ml 10,000 molecular weight–cutoff spin concentrators (Amicon) before use. Protein concentrations are reported for the CP heterodimer and were determined by A280 using the calculated extinction coefficient of the CP heterodimer (ϵ280 = 18,450 m−1 cm−1) obtained from the online ExPASy ProtParam tool.

Instrumentation

Mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometric analyses were conducted using an Agilent 6510 quadrupole TOF mass spectrometer with an Agilent Jetstream electrospray ionization source, which is housed in the Center for Environmental Health Sciences Bioanalytical Core Facility at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Pyoverdine samples were prepared in Milli-Q water and injected directly. Solvent A was 0.1% formic acid in water, and solvent B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile.

Optical absorption spectroscopy

Optical absorption spectra and A600 measurements were recorded on a Beckman Coulter DU800 spectrophotometer operated at ambient temperature. Quartz cuvettes (1-cm path length; Starna) were used to measure the pyoverdine absorption spectrum. Disposable plastic cuvettes (1-cm path length) were used for A600 measurements.

Fluorescence spectroscopy

Fluorescence spectroscopy was performed using a Photon Technologies International QuantaMaster 40 fluorometer outfitted with a continuous xenon source for excitation, autocalibrated QuadraScopic monochromators, a multimode photomultiplier tube detector, and a circulating water bath set at 25 °C. The spectrophotometer was controlled by the FelixGX software package. The fluorometer parameters used for acquiring emission spectra are described below (see “Pyoverdine fluorescence measurements”).

HPLC

HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1200 instrument equipped with a thermostated autosampler set at 4 °C; a thermostated column compartment set at 20 °C; a multiwavelength detector set at 220, 280, and 365 nm (500-nm reference wavelength, 40-nm bandwidth); and a fluorescence detector set at λex = 398 nm and λem = 455 nm for pyoverdine detection. For all HPLC runs, solvent A was 0.1% TFA in water, and solvent B was 0.1% TFA in MeCN. A Clipeus C18 column (5-μm pore, 4.6 × 250 mm; Higgins, Inc.) and a flow rate of 1 ml/min were used for all analytical HPLC. A Zorbax 300SB C18 column (5-μm pore, 9.4 × 250 mm; Agilent) and a flow rate of 4 ml/min were used for semipreparative HPLC. Elution gradients are given for specific experiments below.

Microwave digestion

For metal analysis of bacterial suspensions, bacterial suspensions were liquefied using a Milestone UltraWAVE digestion system housed in the Center for Environmental Health Sciences Core Facility at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. A standard microwave protocol (15-min ramp to 180 °C at 1500-watt power; 10-min ramp to 220 °C at 1500-watt power) was used for the acid digestion.

ICP-MS

Metal ion concentrations were quantified using an Agilent 7900 inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometer housed in the Center for Environmental Health Sciences Bioanalytical Core Facility at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The instrument was operated in helium mode. The instrument was calibrated before each analysis session using a series of five serially diluted (1:10) samples of the Environmental Calibration Standard (Agilent, part number 5183-4688) in 5% nitric acid (Honeywell, TraceSELECT; >69.0%) as well as a 5% nitric acid–only standard. The concentrations of magnesium, calcium, manganese, iron, cobalt, nickel, copper, and zinc were quantified, and terbium (1 ppb terbium; Agilent, part number 5190-8590) was used as an internal standard. Samples were prepared in 15-ml Falcon tubes, and 2-ml samples were transferred to ICP-MS polypropylene vials (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, B3001566) and analyzed.

General microbiology methods

Bacterial growth media

TSB (VWR) and LB (VWR) were prepared as recommended by the supplier. TSB was supplemented with 0.25% dextrose from a sterile solution of 40% dextrose (Sigma).

Preparation of metal-depleted Tris/TSB

Tris/TSB is a 62:38 mixture of 20 mm Tris, 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.5, and TSB medium. This medium was supplemented with 2 mm Ca(II) from a 1 m stock in Milli-Q water and sterilized by filtration (0.2 μm). The medium was supplemented with 10 μm CP-Ser from a 600–800 μm stock solution in 20 mm Tris, 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.5. The medium containing CP-Ser was incubated at 37 °C for 40 h before being transferred to a 10,000 molecular weight–cutoff spin filter and centrifuged for 20 min at 3750 rpm at 4 °C. The resulting flow-through was metal-depleted Tris/TSB. Replete, depleted, manganese-depleted, iron-depleted, and zinc-depleted media were prepared from metal-depleted Tris/TSB as follows. Replete Tris/TSB was prepared by supplementing 0.3 μm Mn(II), 5 μm Fe(II), and 6 μm Zn(II); depleted Tris/TSB was prepared by supplementing 0.03 μm Mn(II), 0.5 μm Fe(II), and 0.6 μm Zn(II); manganese-depleted Tris/TSB was prepared by supplementing 0.03 μm Mn(II), 5 μm Fe(II), and 6 μm Zn(II); iron-depleted Tris/TSB was prepared by supplementing 0.3 μm Mn(II), 0.5 μm Fe(II), and 6 μm Zn(II); and zinc-depleted Tris/TSB was prepared by supplementing 0.3 μm Mn(II), 5 μm Fe(II), and 0.6 μm Zn(II). Metals were added from 1 mm (Mn(II)) or 10 mm (Fe(II) and Zn(II)) stock solutions prepared in Milli-Q water and sterilized by syringe filtration (0.2 μm).

Preparation of CDM

Metal-depleted CDM was prepared as described previously (63). This medium was supplemented with 1 mm Ca(II), 0.3 μm Mn(II), 5 μm Fe(II), 0.1 μm Ni(II), 0.1 μm Cu(II), and 6 μm Zn(II) to make CDM.

Strain generation

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1. The mini-CTX1-PantR-′lacZ−SD construct was used to introduce the PantR-′lacZ−SD reporter at the chromosomal attB site of PA14 and PA14 Δphz as described previously (64).

Metal inventory assay

Bacteria (Table S1) were streaked on TSB or LB 1.5% agarose plates and incubated at 37 °C for 12–16 h. A single colony was used to inoculate 3 ml of LB or TSB and incubated at 37 °C for 12 h. This culture was diluted 1:100 into 2 ml of LB, Tris/TSB, or metal-depleted Tris/TSB (both contained 2 mm Ca(II)) and supplemented with CP-Ser, WT CP, or CP variant (10 μm for Tris/TSB and metal-depleted Tris/TSB cultures; 20 μm for LB cultures). Untreated cultures were supplemented with an equivalent volume of buffer (20 mm Tris, 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.5). Diluted cultures were incubated for 8 h at 37 °C at 250 rpm before measuring the A600 of the culture and harvesting the cells by centrifugation (3750 rpm, 4 °C, 5 min). Supernatants (1 ml) were stored at −20 °C until further use in metabolite analyses. Cell pellets were washed by a three-step procedure with 1 ml of cold (i) Tris buffer, (ii) Tris buffer + 500 μm EDTA (VWR, product number M101-500G), and (iii) Tris buffer. Cells were resuspended to an A600 of 10 in Tris buffer, and 200 μl of this cell suspension was diluted into 1.8 ml of 5% HNO3 (Honeywell, TraceSELECT; >69.0%). The resulting acidified samples were liquefied by microwave digestion and analyzed by ICP-MS. As an additional control for a consistent number of cells between untreated and CP-treated cultures, only biological replicates of CP-treated cultures with magnesium content within 20% of the magnesium content of the untreated culture were included in subsequent analyses. In addition to A600, cfu/ml in cultures grown in the absence and presence of CP was measured for select experiments. Reported metal concentrations correspond to the metal content of an A600 = 10 cell suspension, which corresponds to ∼1.2 × 1010 cfu/ml for P. aeruginosa PA14. The number of iron atoms/cfu was calculated using iron atoms/ml determined by ICP-MS, correcting for the difference in volume between the original culture and the resuspension volume to get to an A600 of 10, and dividing by cfu/ml measured in each culture. For growth of P. aeruginosa PA14 in the absence or presence of CP in LB, similar A600 and cfu/ml values were observed (A600 ranged from 2.2 to 2.8; cfu/ml ranged from 2 × 109 to 3.6 × 109). Both individual data points and the mean metal content are reported with p values from a two-tailed t test assuming unequal variances.

Metal and CP supplementation growth assay

P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14 were streaked from freezer stocks onto TSB agar plates and grown overnight at 37 °C. Five colonies were used to inoculate 2 ml of TSB and grown overnight at 37 °C at 250 rpm. The A600 of the overnight culture was measured, and the culture was diluted into experimental cultures to a final A600 of 0.05. Cultures were grown in metal-depleted Tris/TSB (see “Preparation of metal-depleted Tris/TSB” above) in the absence or presence of CP-Ser (10 or 20 μm). Growth of cultures at 37 °C with fast shaking was monitored in a Bioscreen C MBR (Oy Growth Curves Ab Ltd., Helsinki, Finland). The mean optical density and S.E. are reported.

Purification of pyoverdine

P. aeruginosa PAO1 was streaked onto a 1.5% agar TSB plate and incubated for 14–20 h at 37 °C. Tris/TSB medium (40 ml) was supplemented with 2 mm CaCl2 and 600 μm 2,2′-dipyridyl (Sigma-Aldrich; added from a 200 mm stock in DMSO) in a sterile 250-ml baffled flask. Medium was inoculated with a single PAO1 colony, and this culture was incubated for 20 h at 37 °C at 150 rpm. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C), and the supernatant was removed and stored at −20 °C for ∼24 h. The supernatant was thawed and filtered through a 0.2-μm filter. A Sep-Pak Plus C18 Environmental Cartridge (Waters, WAT023635) was equilibrated first with 10 ml of 0.1% TFA in MeCN (solvent B) and then with 40 ml of 0.1% TFA in 40 ml of Milli-Q water (solvent A). The cartridge was loaded with the supernatant (∼35 ml), and the resin turned a dark green color. The cartridge was washed with solvent A (10 ml), which caused the cartridge to turn brown. Pyoverdine was eluted with 5 ml of 5% MeCN in Milli-Q water containing 0.1% TFA. This fraction was centrifuged (14,000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C), and pyoverdine was purified from the resulting supernatant by semipreparative HPLC (method, 8–13% B over 20 min at 4 ml/min) using eight injections of 200–600 μl. Pyoverdine eluted at 14.3 min. The peak corresponding to pyoverdine from each run was collected, and the combined material was lyophilized to dryness. The identity and purity of the product were assessed by HPLC, optical absorption spectroscopy, ICP-MS, and MS. For analytical HPLC, the method used was 0–35% B over 30 min at 1 ml/min. Integration of the HPLC trace obtained at 220 nm indicated a purity of 56%. This purification yielded ∼0.1 mg of pyoverdine from a 40-ml culture. The final product was dissolved in Milli-Q water, and its concentration was determined by optical absorption spectroscopy (ϵ380 = 16,500 m−1 at pH 5.0) (65). A concentrated stock solution of pyoverdine (∼500 μm in Milli-Q water) was stored at −20 °C until use. The metal content of purified pyoverdine was determined by ICP-MS (Table S8). Mass spectrometry indicated that this isolation yielded PVD1 with a succinamide R group (Fig. S6). The isolated product was used as a standard for HPLC quantification of pyoverdine in supernatant samples and as a supplement for CP-Ser metal depletion assays.

Detection of metabolites by HPLC

Culturing

P. aeruginosa PAO1, PAO1 ΔprrF, PA14, and PA14 Δphz were streaked on TSB 1.5% agarose plates and incubated at 37 °C for 12–16 h. A single colony was used to inoculate 3 ml of TSB, and the culture was incubated at 37 °C for 12 h on a rotating wheel. This culture was diluted 1:100 into 2 ml of Tris/TSB + 2 mm Ca(II) or CDM, and CP-Ser or variants (10 μm) or an equivalent volume of buffer (20 mm Tris, 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.5) for untreated cultures was added. For cultures with phenazine supplementation, PYO or PCA (20 μm) was added to this culture from a 10 mm stock solution in DMSO. Diluted cultures were incubated for 8 (Tris/TSB cultures) or 16 h (CDM cultures) at 37 °C at 250 rpm before harvesting the supernatant (3750 rpm, 4 °C, 5 min) for HPLC analysis.

Pyoverdine

Supernatants were thawed and centrifuged to pellet any cell debris (14,000 rpm, 4 °C, 10 min). A 150-μl aliquot was transferred to an HPLC vial and analyzed by analytical HPLC using a gradient of 0–35% B for 30 min at 1 ml/min. A 10-μl volume of supernatant or standard was injected. Using this method, pyoverdine eluted at ∼16.5 min. HPLC fluorescence detection (λex = 398 nm, λem = 455 nm) is shown. For pyoverdine quantification, a standard curve of pyoverdine (100, 50, 25, 13, 6, 3, 1.5, and 0.75 μm) was run alongside supernatant samples, and calculated pyoverdine concentrations were normalized to culture A600. Both the mean normalized pyoverdine concentration and individual data points are reported with p values from a two-tailed t test assuming unequal variances.

Phenazines

Supernatants were thawed and centrifuged to pellet any cell debris (14,000 rpm, 4 °C, 10 min). A 150-μl aliquot was transferred to a vial and analyzed by analytical HPLC (15–80% B, 30 min, 1 ml/min). A 50-μl volume of supernatant or standard was injected. Integration at 365 nm was converted to phenazine concentration using a standard curve of PYO or PCA (500, 100, 50, 10, 5, 2.5, and 1.25 μm). Phenazine concentrations were normalized to culture A600 to control for slight differences in growth between conditions. Both individual data points and the mean normalized phenazine concentrations are reported with p values from a two-tailed t test assuming unequal variances.

Pyoverdine fluorescence measurements

Supernatants of PA14, PA14 Δphz, PAO1, and PAO1 ΔpvdA (cultured as described for detection of microbial metabolites above) were thawed and centrifuged to pellet any cell debris (14,000 rpm, 4 °C, 10 min). Supernatant samples (100 μl) were diluted into 900 μl of 50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, and fluorescence spectra were recorded from 410 to 600 nm (λex = 400 nm, 1 nm/s, 0.4-mm slits).

Real-time PCR

P. aeruginosa PAO1 were streaked on TSB 1.5% agarose plates and incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. A single colony was used to inoculate 3 ml of TSB, and the culture was incubated at 37 °C for 16 h at 250 rpm. This culture was diluted 1:100 into 5-ml CDM in an acid-washed 50-ml flask and supplemented with CP-Ser (10 μm) or an equivalent volume of buffer (20 mm Tris, 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.5). This diluted culture was grown at 37 °C for 16 h at 250 rpm, and an aliquot of culture (500 μl) was combined with RNAlater (Sigma; 500 μl) prior to RNA extraction. RNA was extracted using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's directions. RNA (50 ng/μl) was used to generate cDNA with an ImPromII cDNA synthesis kit (Promega). A StepOnePlus instrument (Applied Biosystems) and TaqMan reagents (Life Technologies) were used to analyze cDNA. Primers and probes for pvdS and oprF are listed in Table S2. Relative RNA levels were normalized to the levels of the oprF mRNA, and -fold changes in mRNA relative to the untreated control are shown. Both individual data points from three biological replicates and the mean -fold change are reported with p values from a two-tailed t test assuming unequal variances.

antR translational reporter assay

P. aeruginosa PAO1/PantR′lacZ−SD, ΔprrF/PantR-′lacZ−SD, PA14/PantR-′lacZ−SD, and PA14 Δphz/PantR-′lacZ−SD were grown in Tris/TSB, metal-depleted Tris/TSB, or CDM in the absence or presence of 5, 10, or 20 μm CP-Ser at 37 °C for 8 (Tris/TSB and metal-depleted Tris/TSB) or 16 h (CDM). β-Galactosidase activity was measured as described previously (48). Briefly, cell density was measured (A600), and cells were harvested by centrifugation. The cell pellet was resuspended in 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, and diluted 1:10 in Z-buffer (60 mm Na2HPO4, 35 mm NaH2PO4, 1 mm KCl, 100 mm MgSO4, 50 mm β-mercaptoethanol (all components acquired from Sigma)). Cells were lysed using chloroform and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). The reaction was initiated with the addition of o-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside (Thermo; 4 mg/ml solution in 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) and proceeded until the solution turned light yellow. The reaction was quenched using 1 m sodium carbonate. The quenched reaction solution was centrifuged at 13,000 × g to remove cell debris, and the absorbance (A420) of the supernatant was determined. β-Galactosidase activity was quantified as Miller units calculated using the following equation: (1000 × A420)/(time (in min) × volume (in ml) × A600). Both individual data points and the mean Miller units are reported with p values from a two-tailed t test assuming unequal variances.

Metal depletion assay

Tris/TSB supplemented with 2 mm Ca(II) (20 ml) was aliquoted into 50-ml Falcon tubes and supplemented with 10 μm CP-Ser in the absence or presence of 5 μm PYO or 2 μm pyoverdine. Samples were incubated at 37 °C at 150 rpm, and at 0, 4, and 8 h, a 2-ml aliquot was removed from each sample and applied to a 10,000 molecular weight–cutoff filter (4 ml; Amicon) and centrifuged at 3750 rpm for 20 min. The flow-through (1 ml) was diluted into 1 ml of 5% HNO3 (Honeywell, TraceSELECT; >69.0%). All samples were supplemented with 1 ppb terbium and analyzed by ICP-MS. Both the individual data points and the mean iron concentration are reported with p values from a two-tailed t test assuming unequal variances.

Data sharing

All data are presented in the main text and supporting information. Original data files, plasmids, strains, and protein samples (when a laboratory is unable to perform protein purification) will be made available upon request.

Author contributions

E. M. Z. designed the research, performed research, analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript; C. E. N. designed the research, performed research, analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript; L. K. B. designed the research, performed research, analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript; A. G. O.-S. designed the research, analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript; E. M. N. designed the research, analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The ICP-MS instrument at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is maintained by the MIT Center for Environmental Health Sciences (National Institutes of Health Grant P30-ES002109). We thank Dr. H. Neu for technical assistance with ICP-MS analysis at the University of Maryland, Baltimore School of Pharmacy Mass Spectrometry Center (Grant SOP1841-IQB2014). We thank Prof. D. K. Newman for kindly providing the PA14 and Δphz strains.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 GM126376 (to E. M. N. and A. G. O.-S.), T32 AI095190 (to C. E. N.), and T32 GM066706 (to L. K. B.) The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S13 and Tables S1–S7.

- CP

- calprotectin

- CF

- cystic fibrosis

- Fur

- ferric uptake regulator

- sRNA

- small RNA

- βME

- β-mercaptoethanol

- ICP

- inductively coupled plasma

- PCA

- phenazine-1-carboxylate

- PYO

- pyocyanin

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- CDM

- chemically defined medium

- TSB

- tryptic soy broth

- AQ

- 2-alkyl-4(1H)-quinolone

- LB

- Luria-Bertani medium.

References

- 1. Cassat J. E., and Skaar E. P. (2013) Iron in infection and immunity. Cell Host Microbe 13, 509–519 10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weinberg E. D. (1975) Nutritional immunity. Host's attempt to withold iron from microbial invaders. JAMA 231, 39–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hood M. I., and Skaar E. P. (2012) Nutritional immunity: transition metals at the pathogen–host interface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 525–537 10.1038/nrmicro2836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schaible U. E., Collins H. L., Priem F., and Kaufmann S. H. (2002) Correction of the iron overload defect in β-2-microglobulin knockout mice by lactoferrin abolishes their increased susceptibility to tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 196, 1507–1513 10.1084/jem.20020897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goetz D. H., Holmes M. A., Borregaard N., Bluhm M. E., Raymond K. N., and Strong R. K. (2002) The neutrophil lipocalin NGAL is a bacteriostatic agent that interferes with siderophore-mediated iron acquisition. Mol. Cell 10, 1033–1043 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00708-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hider R. C., and Kong X. (2010) Chemistry and biology of siderophores. Nat. Prod. Rep. 27, 637–657 10.1039/b906679a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hunter R. C., Asfour F., Dingemans J., Osuna B. L., Samad T., Malfroot A., Cornelis P., and Newman D. K. (2013) Ferrous iron is a significant component of bioavailable iron in cystic fibrosis airways. MBio 4, e00557–13 10.1128/mBio.00557-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lau C. K., Krewulak K. D., and Vogel H. J. (2016) Bacterial ferrous iron transport: the Feo system. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 40, 273–298 10.1093/femsre/fuv049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nakashige T. G., Zhang B., Krebs C., and Nolan E. M. (2015) Human calprotectin is an iron-sequestering host-defense protein. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 765–771 10.1038/nchembio.1891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zygiel E. M., and Nolan E. M. (2018) Transition metal sequestration by the host-defense protein calprotectin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 87, 621–643 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-012312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Korndörfer I. P., Brueckner F., and Skerra A. (2007) The crystal structure of the human (S100A8/S100A9)2 heterotetramer, calprotectin, illustrates how conformational changes of interacting α-helices can determine specific association of two EF-hand proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 370, 887–898 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Damo S. M., Kehl-Fie T. E., Sugitani N., Holt M. E., Rathi S., Murphy W. J., Zhang Y., Betz C., Hench L., Fritz G., Skaar E. P., and Chazin W. J. (2013) Molecular basis for manganese sequestration by calprotectin and roles in the innate immune response to invading bacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 3841–3846 10.1073/pnas.1220341110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hayden J. A., Brophy M. B., Cunden L. S., and Nolan E. M. (2013) High-affinity manganese coordination by human calprotectin is calcium-dependent and requires the histidine-rich site formed at the dimer interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 775–787 10.1021/ja3096416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brophy M. B., Hayden J. A., and Nolan E. M. (2012) Calcium ion gradients modulate the zinc affinity and antibacterial activity of human calprotectin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18089–18100 10.1021/ja307974e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Corbin B. D., Seeley E. H., Raab A., Feldmann J., Miller M. R., Torres V. J., Anderson K. L., Dattilo B. M., Dunman P. M., Gerads R., Caprioli R. M., Nacken W., Chazin W. J., and Skaar E. P. (2008) Metal chelation and inhibition of bacterial growth in tissue abscesses. Science 319, 962–965 10.1126/science.1152449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wakeman C. A., Moore J. L., Noto M. J., Zhang Y., Singleton M. D., Prentice B. M., Gilston B. A., Doster R. S., Gaddy J. A., Chazin W. J., Caprioli R. M., and Skaar E. P. (2016) The innate immune protein calprotectin promotes Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus interaction. Nat. Commun. 7, 11951 10.1038/ncomms11951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Diaz-Ochoa V. E., Lam D., Lee C. S., Klaus S., Behnsen J., Liu J. Z., Chim N., Nuccio S.-P., Rathi S. G., Mastroianni J. R., Edwards R. A., Jacobo C. M., Cerasi M., Battistoni A., Ouellette A. J., et al. (2016) Salmonella mitigates oxidative stress and thrives in the inflamed gut by evading calprotectin-mediated manganese sequestration. Cell Host Microbe 19, 814–825 10.1016/j.chom.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kehl-Fie T. E., Chitayat S., Hood M. I., Damo S., Restrepo N., Garcia C., Munro K. A., Chazin W. J., and Skaar E. P. (2011) Nutrient metal sequestration by calprotectin inhibits bacterial superoxide defense, enhancing neutrophil killing of Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Host Microbe 10, 158–164 10.1016/j.chom.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Garcia Y. M., Barwinska-Sendra A., Tarrant E., Skaar E. P., Waldron K. J., and Kehl-Fie T. E. (2017) A superoxide dismutase capable of functioning with iron or manganese promotes the resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to calprotectin and nutritional Immunity. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006125 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Radin J. N., Kelliher J. L., Párraga Solórzano P. K., and Kehl-Fie T. E. (2016) The two-component system ArlRS and alterations in metabolism enable Staphylococcus aureus to resist calprotectin-induced manganese starvation. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1006040 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kelliher J. L., and Kehl-Fie T. E. (2016) Competition for manganese at the host–pathogen interface. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 142, 1–25 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2016.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pantopoulos K., Porwal S. K., Tartakoff A., and Devireddy L. (2012) Mechanisms of mammalian iron homeostasis. Biochemistry 51, 5705–5724 10.1021/bi300752r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nakashige T. G., and Nolan E. M. (2017) Human calprotectin affects the redox speciation of iron. Metallomics 9, 1086–1095 10.1039/C7MT00044H [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wilkinson M. M., Busuttil A., Hayward C., Brock D. J., Dorin J. R., and Van Heyningen V. (1988) Expression pattern of two cystic fibrosis-associated calcium binding proteins in normal and abnormal tissues. J. Cell Sci. 91, 221–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lyczak J. B., Cannon C. L., and Pier G. B. (2002) Lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15, 194–222 10.1128/CMR.15.2.194-222.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cowley E. S., Kopf S. H., LaRiviere A., Ziebis W., and Newman D. K. (2015) Pediatric cystic fibrosis sputum can be chemically dynamic, anoxic, and extremely reduced due to hydrogen sulfide formation. MBio 6, e00767 10.1128/mBio.00767-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cornelis P., and Dingemans J. (2013) Pseudomonas aeruginosa adapts its iron uptake strategies in function of the type of infections. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 3, 75 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nguyen A. T., and Oglesby-Sherrouse A. G. (2015) Spoils of war: iron at the crux of clinical and ecological fitness of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biometals 28, 433–443 10.1007/s10534-015-9848-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wilderman P. J., Sowa N. A., FitzGerald D. J., FitzGerald P. C., Gottesman S., Ochsner U. A., and Vasil M. L. (2004) Identification of tandem duplicate regulatory small RNAs in Pseudomonas aeruginosa involved in iron homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9792–9797 10.1073/pnas.0403423101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Massé E., Vanderpool C. K., and Gottesman S. (2005) Effect of RyhB small RNA on global iron use in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187, 6962–6971 10.1128/JB.187.20.6962-6971.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reinhart A. A., Nguyen A. T., Brewer L. K., Bevere J., Jones J. W., Kane M. A., Damron F. H., Barbier M., and Oglesby-Sherrouse A. G. (2017) The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PrrF small RNAs regulate iron homeostasis during acute murine lung infection. Infect. Immun. 85, e00764–16 10.1128/IAI.00764-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reinhart A. A., and Oglesby-Sherrouse A. G. (2016) Regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by distinct iron sources. Genes 7, E126 10.3390/genes7120126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Konings A. F., Martin L. W., Sharples K. J., Roddam L. F., Latham R., Reid D. W., and Lamont I. L. (2013) Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses multiple pathways to acquire iron during chronic infection in cystic fibrosis lungs. Infect. Immun. 81, 2697–2704 10.1128/IAI.00418-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nguyen A. T., O'Neill M. J., Watts A. M., Robson C. L., Lamont I. L., Wilks A., and Oglesby-Sherrouse A. G. (2014) Adaptation of iron homeostasis pathways by a Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyoverdine mutant in the cystic fibrosis lung. J. Bacteriol. 196, 2265–2276 10.1128/JB.01491-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang Y., and Newman D. K. (2008) Redox reactions of phenazine antibiotics with ferric (hydr)oxides and molecular oxygen. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 2380–2386 10.1021/es702290a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dietrich L. E., Price-Whelan A., Petersen A., Whiteley M., and Newman D. K. (2006) The phenazine pyocyanin is a terminal signalling factor in the quorum sensing network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 1308–1321 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05306.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Glasser N. R., Kern S. E., and Newman D. K. (2014) Phenazine redox cycling enhances anaerobic survival in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by facilitating generation of ATP and a proton-motive force. Mol. Microbiol. 92, 399–412 10.1111/mmi.12566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meirelles L. A., and Newman D. K. (2018) Both toxic and beneficial effects of pyocyanin contribute to the lifecycle of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 110, 995–1010 10.1111/mmi.14132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Price-Whelan A., Dietrich L. E., and Newman D. K. (2007) Pyocyanin alters redox homeostasis and carbon flux through central metabolic pathways in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol. 189, 6372–6381 10.1128/JB.00505-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang Y., Wilks J. C., Danhorn T., Ramos I., Croal L., and Newman D. K. (2011) Phenazine-1-carboxylic acid promotes bacterial biofilm development via ferrous iron acquisition. J. Bacteriol. 193, 3606–3617 10.1128/JB.00396-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xiao R., and Kisaalita W. S. (1997) Iron acquisition from transferrin and lactoferrin by Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyoverdin. Microbiology 143, 2509–2515 10.1099/00221287-143-7-2509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mastropasqua M. C., Lamont I., Martin L. W., Reid D. W., D'Orazio M., and Battistoni A. (2018) Efficient zinc uptake is critical for the ability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to express virulence traits and colonize the human lung. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 48, 74–80 10.1016/j.jtemb.2018.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Braud A., Geoffroy V., Hoegy F., Mislin G. L., and Schalk I. J. (2010) Presence of the siderophores pyoverdine and pyochelin in the extracellular medium reduces toxic metal accumulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and increases bacterial metal tolerance. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2, 419–425 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00126.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cunliffe H. E., Merriman T. R., and Lamont I. L. (1995) Cloning and characterization of pvdS, a gene required for pyoverdine synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: PvdS is probably and alternative σ factor. J. Bacteriol. 177, 2744–2750 10.1128/jb.177.10.2744-2750.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Oglesby A. G., Farrow J. M. 3rd, Lee J.-H., Tomaras A. P., Greenberg E. P., Pesci E. C., and Vasil M. L. (2008) The influence of iron on Pseudomonas aeruginosa physiology: a regulatory link between iron and quorum sensing. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 15558–15567 10.1074/jbc.M707840200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Djapgne L., Panja S., Brewer L. K., Gans J. H., Kane M. A., Woodson S. A., and Oglesby-Sherrouse A. G. (2018) The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PrrF1 and PrrF2 small regulatory RNAs promote 2-alkyl-4-quinolone production through redundant regulation of the antR mRNA. J. Bacteriol. 200, e00704–17 10.1128/JB.00704-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Recinos D. A., Sekedat M. D., Hernandez A., Cohen T. S., Sakhtah H., Prince A. S., Price-Whelan A., and Dietrich L. E. (2012) Redundant phenazine operons in Pseudomonas aeruginosa exhibit environment-dependent expression and differential roles in pathogenicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 19420–19425 10.1073/pnas.1213901109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Green M. R., and Sambrook J. (2012) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 4th Ed, pp. 1346–1349, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cunrath O., Geoffroy V. A., and Schalk I. J. (2016) Metallome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a role for siderophores. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 3258–3267 10.1111/1462-2920.12971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Radin J. N., Zhu J., Brazel E. B., McDevitt C. A., and Kehl-Fie T. E. (2018) Synergy between nutritional immunity and independent host defenses contributes to the importance of the MntABC manganese transporter during Staphylococcus aureus infection. Infect. Immun. 87, e00642–18 10.1128/IAI.00642-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Huang W., and Wilks A. (2017) Extracellular heme uptake and the challenge of bacterial cell membranes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86, 799–823 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Becker K. W., and Skaar E. P. (2014) Metal limitation and toxicity at the interface between host and pathogen. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 38, 1235–1249 10.1111/1574-6976.12087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]