Abstract

Past research on immigrant health frequently finds that the duration of time lived in the U.S. is associated with the erosion of immigrants’ health advantages. However, the timing of U.S. migration during the life course is rarely explored. We draw from developmental and sociological perspectives to theorize how migration during childhood may be related to healthy eating among adult immigrants from Mexico. We test these ideas with a mechanism-based age-period-cohort model to disentangle age, age at arrival, and duration of residence. Results show that immigrants who arrived during preschool ages (2–5) and school ages (6–11) have less healthy diets than adult arrivals (age 25+). After accounting for age at arrival, duration of residence is positively related to healthy eating. Overall, the findings highlight the need to focus more research and policy interventions on child immigrants, who may be particularly susceptible to adopting unhealthy American behaviors during sensitive periods of childhood.

Keywords: Health, Diet, Immigrants, Acculturation, Age at arrival, Duration of residence, Life Course

Decades of research suggests that life in the U.S. can take a toll on the health of immigrants (e.g., Antecol and Bedard 2006; Akresh 2007). This process of “unhealthy assimilation” has been attributed to a host of individual, cultural, and structural factors and is commonly theorized as occurring over time. That is, the longer immigrants reside in the U.S., the worse their health. Yet, few previous studies have examined the influence of another critical dimension of immigrants’ time in the U.S.: their age at migration. Migration during socially and developmentally sensitive periods of childhood may raise immigrants’ health risks. We explore this idea by considering how the timing of migration, and not just the duration of U.S. residence, matters for an important health behavior: healthy eating.

Immigrants who moved to the U.S. as children, a group often referred to as the “1.5 generation” (Rumbaut 2004), enjoy some socioeconomic advantages over adult arrivals. For example, they are more likely to become proficient in English and have higher levels of educational attainment (Bleakley and Chin 2010; Stevens 1999). However, arrival during childhood or adolescence may also carry risks that could lead to long-term health problems. Child immigrants entering U.S. society and schools during sensitive ages when health habits are still developing may be particularly susceptible to adopting unhealthy behaviors. Consistent with this idea, immigrants who arrived during childhood or adolescence have worse maternal health (Teitler, Martinson, and Reichman 2015) and higher rates of obesity (Roshania, Narayan, and Oza-Frank 2008). Additionally, the preschool children of mothers who arrived in adolescence have lower cognitive scores than the children of other immigrant mothers (Glick, Bates, and Yabiku 2009).

Our study makes two key contributions. First, we extend prior work by exploring whether and how arrival during childhood affects healthy eating. Healthy eating is important because it is linked to multiple chronic health conditions (Schwingshackl and Hoffmann 2015) and is thus fundamental for understanding immigrants’ health risks. No prior research to our knowledge has examined how age at arrival is related to healthy eating. Rather, research has tended to focus on duration of residence, finding that diet worsens as immigrants spend time in the U.S. (Abraído-Lanza, Chao, and Flórez 2005; Akresh 2007). By focusing on duration of residence without also considering age at arrival, this work may have underestimated the vulnerability of childhood arrivals to unhealthy dietary assimilation and overestimated the negative effects of duration of residence.

A second contribution is that we employ a more robust method for disentangling the effects of age at arrival from duration of residence than used in past work. Early age at arrival and longer U.S. durations are correlated, and both are expected to be related to unhealthy eating. Therefore, both age at arrival and duration effects could be overestimated if either were ignored (Stevens 1999; Hamilton, Palermo, and Green 2015). Yet it is challenging to estimate the independent effects of these temporal factors because they are collinear with each other and with age (age at arrival + duration of residence = age). Prior research on immigrant health has dealt with this challenge by ignoring it (i.e., by dropping one of the three terms) or by imposing assumptions. We instead use a mechanism-based modeling approach developed by Winship and Harding (2008) which allows us to isolate the effects of age at migration from duration of residence and age.

Although the ideas we develop are likely applicable to many national origin groups, we focus on Mexican immigrants to minimize heterogeneity in dietary behaviors within our sample. Mexicans compose nearly one-third of the U.S. total foreign-born population (Grieco et al. 2012), have comparatively high prevalence of overweight, obesity, and diabetes (Holub et al. 2013; Lopez and Golden 2014), and are numerically large enough to analyze with our data. Our work provides an important illustration of how early life experiences affect a vulnerable immigrant group’s capacity for navigating the American food environment.

Background and Theory

The American Food Environment

The American food environment is characterized by the ubiquity of foods of minimal nutritional value. Described by prominent scholars such as Marion Nestle (2007), American stores and restaurants provide consumers access to low-cost, energy dense foods nearly anywhere, including unlikely venues such as hair salons, hardware stores, and banks (Farley et al. 2010). The expansion of highly efficient food production and distribution systems since World War II have enabled food producers to inundate Americans with large quantities of inexpensive food, particularly meat, dairy, and refined carbohydrates (Popkin 2006).

Identified as the nutrition transition (Hill and Peters 1998), the diets of middle- and high-income countries across the globe have shifted from featuring a balance of vegetables, grains, fruit, and meat toward diets featuring sugar-sweetened foods, vegetable oils, animal-sourced protein, processed foods, and large portion sizes in the last three to four decades (Popkin, Adair, and Ng 2012). The diet consumed by the average American now exceeds USDA recommendations for caloric intake and for sugar, saturated fat, sodium, refined grains and animal-sourced protein (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and USDA 2015).

Though the nutrition transition has deeply impacted Mexico (Rivera et al. 2004), most Mexican immigrants—two-thirds of whom immigrated in the 1990s or earlieri—encountered a dramatically different food environment from Mexico’s when they first came to the U.S. As recently as 1994, obesity prevalence among adults was only 10% in Mexico compared with 26% in the U.S. (Barquera et al. 2009; Flegal et al. 2002). By 2000, the prevalence in Mexico had risen to 26%--still lower than the U.S. prevalence of 31% (Ogden et al. 2014; Quezada and Lozada-Tequeanes 2015). Furthermore, Mexican immigrant women and children have lower obesity prevalence than their counterparts in Mexico (Ro and Fleischer 2014; Van Hook et al 2012) and Mexican Americans in the U.S. (Guendelman et al. 2013), partially because they frequently originate from rural areas in Mexico where obesity levels are relatively lower (Barquera et al. 2009). Cross-national research similarly suggests that migration from Mexico to the U.S. is associated with unhealthy changes in eating behaviors (Batis et al. 2011).

Duration of Residence and Healthy Eating

Given the contrast in diet quality and obesity risk between Mexico and the U.S., how might duration of U.S. residence and age at arrival shape healthy eating among Mexican immigrants? Comparably more research has focused on duration of residence than age at arrival, and the dominant expectation emerging from this work is that duration of residence will be associated with unhealthy eating as immigrants adopt the unhealthy eating habits that characterize the default American lifestyle. The implicit notion is that immigrants must be deliberate to avoid the adoption of unhealthy diets and other negative health behaviors (Mirowsky and Ross 2010). The widespread availability of inexpensive, unhealthy industrialized foods (Patil, Hadley, and Nahayo 2009) makes the “easy food choice” synonymous with the unhealthy one, so immigrants’ healthy eating behaviors are difficult to maintain.

Furthermore, duration of residence, which itself is often used as a proxy of immigrant integration, may operate through other indicators of immigrant integration, such as English language proficiency or residence outside immigrant enclaves, to increase unhealthy eating (Ayala, Baquero, and Klinger 2008; Dubowitz et al. 2008). For example, duration may influence healthy eating through social interactions with the U.S.-born. As immigrants and their families move out of ethnic communities and into more diverse employment sectors, neighborhoods, schools, and social networks, they may begin to adopt the eating habits of their American colleagues, acquaintances, and neighbors. Together, these ideas lead to our first hypothesis (H1): duration of residence is negatively associated with healthy eating.

Not all immigrants may follow this pattern, however. Building from segmented assimilation theory (Portes and Zhou 1993), several scholars have advanced structural explanations for immigrants’ health declines (Viruell-Fuentes, Miranda, and Abdulrahim 2012), leading us to expect the relationship between duration of residence and healthy eating to vary by socioeconomic status (SES). Among immigrants with low SES, healthy eating may decline with greater duration of residence. Given the time and money it takes to access and prepare healthy food in the U.S. (Rose 2007), immigrants with fewer resources and limited time may experience significant declines in diet quality the longer they live in the U.S. (e.g., Cuy Castellanos et al. 2013; Tovar et al. 2013). For immigrants with higher SES, healthy eating may improve with duration of residence. As immigrants learn English, obtain steady employment, higher-quality housing, higher incomes, and become more familiar with the U.S. food environment, they may be better able to satisfy the (often healthier) food preferences they developed as children in their countries of origin. These ideas lead to a second hypothesis (H2): Duration is associated with less healthy diets among immigrants with lower SES, but healthier diets among those with higher SES.

Childhood Experiences and Healthy Eating

A focus on duration of residence calls attention to the potentially harmful effects of accumulated time in the U.S., particularly for immigrants with few resources, but may overlook how life-long food preferences developed in childhood. We explore the role of age at arrival to enrich our understanding of how the timing of U.S. residence affects immigrants’ healthy eating. Life course models theorize that exposures to environmental conditions during sensitive periods of childhood shape children’s physiological and cognitive development and set in motion lifelong health trajectories (Ben-Shlomo and Kuh 2002; Lynch and Davey Smith 2005). Other scholars have used these ideas to examine immigrant adaptation (e.g., Rumbaut 2004; Teitler et al 2015). We likewise argue that migration experiences in childhood could be important for eating behavior in adulthood.

The food adults consume is strongly driven by food preferences, which are shaped by genetic predispositions, early life experiences, and social influences (Birch 1999). The combination of these factors means that sensitive periods in childhood—infancy, early and middle childhood, and adolescence—can have enduring influences on food preferences and eating behavior. Immigrants who arrived in the U.S. as adults may have already absorbed the often-healthier food preferences and dietary behaviors from Mexico before migration and may be less vulnerable to adopting American eating behaviors than immigrants who arrived as children.

That said, it is not clear whether migration in early childhood, rather than during school-aged years, would be more impactful on dietary behaviors. One possibility is that migration during the formative periods of infancy (ages 0–23 months) and the preschool years (ages 2–5) is the most detrimental. We base this expectation on the insight that adults’ food preferences are shaped by their experiences with food as infants and young children (Birch 1999). Food preferences are most easily modifiable among very young infants and preschool-aged children (Birch and Fisher 1998), and food preferences developed in childhood often persist into adulthood (Nicklaus et al. 2004). These ideas suggest that immigrants who arrived in early childhood, compared to immigrants who arrived at older ages, especially during infancy and preschool, would be more likely to adopt unhealthy American eating behaviors because they would have been exposed to American foods at much younger ages and lacked the opportunity to develop healthier food preferences in their countries of origin.

However, it is also possible that arrival during middle childhood is the most detrimental. Immigrants who arrived in infancy and the preschool years may have moderately healthy diets because parents serve as dietary role models and gatekeepers to young children (Brown and Ogden 2004) and may have buffered their children from the American food environment, especially given that few Mexican immigrants attend U.S. preschools (Crosnoe 2007). In contrast, people who migrated while they were school-aged (roughly 6–11) may be the most vulnerable because, as societal outsiders, they may have felt strong pressure at school to conform to American eating behaviors. In general, schools are important sites for acculturation because they introduce immigrant children to U.S. peers and American ways of thinking, behaving, and eating, possibly swamping parental influences (Zhou 1997). Once they attend school, many children adopt eating behaviors that are independent of their parents’, and immigrant children may undergo the most dramatic changes. One study showed that Mexican children of immigrants gain more weight than do non-Hispanic white or Mexican American children during kindergarten, but during other grades, suggesting that the “shock” of going to an American school for the first time is related to elevated risks of obesity and (most likely) changes in diet (Baumgartner, Frisco, and Van Hook 2017). Other research suggests that social anxiety associated with being foreign may be associated with efforts to fit in by eating American food and embarrassment over ethnic food and food practices even among Asian American college students (Guendelman, Cheryan, and Monin 2011).

These ideas inform a third hypothesis (H3): Immigrants who arrived in the U.S. as adults have healthier diets than those who arrived in childhood. More specifically, developmental perspectives predict that those who arrived during infancy and preschool have the least healthy diets (H3a). However, sociological perspectives about schools as settings for acculturation suggest that those who arrived during school-age years have the least healthy diets (H3b).

Importantly, the duration of residence and age at arrival perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Immigrants’ diets could both worsen with increasing time in the country and be unhealthy among those who arrived in childhood. It is also possible that age-of-arrival effects differ by family SES, similar to our expectations about duration of residence. Immigrants who arrived as children may have been particularly likely to develop unhealthy food preferences if they grew up in socioeconomically disadvantaged families (Martin, Van Hook, and Quiros 2015). Unfortunately, we cannot assess this idea because our data lack retrospective measures of family SES in childhood.

Methodology

Data and Sample

We analyzed the 1999/00—2011/12 Continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a nationally representative, cross-sectional study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHANES collects 24-hour dietary recall data over two different days by trained interviewers using the USDA Automated Multiple-pass Method. Day 1 recalls are conducted in person and Day 2 recalls are collected by telephone (Blanton et al. 2006). We analyzed the restricted version of the NHANES which contains detailed information on immigrants’ year and month of arrival and country of origin.

Our sample was restricted to Mexican-born adults aged 25–64 who completed at least one day of dietary recall. We excluded about 400 cases with out-of-range values on calories consumed (less than 500 or >8,000), leaving a final sample of 2,780 adults. Twelve percent of cases were missing on at least one analytic variables. We imputed missing data using the Stata 14.0 “MI” procedure (Royston 2005).

Approach

To estimate the association of age at arrival (Ri) and duration (Di) with healthy eating (Hi), one might attempt to adjust for age (Ai) and other confounders (Zi) in a regression model like this:

However, the linear dependence among the three temporal factors (A = R + D) makes it impossible to include all three without constraining one or more factor. For example, Teitler and colleagues (2015) estimated the effects of mothers’ age at arrival and duration on birth outcomes by categorizing age at arrival into five-year groups, treating duration as a continuous measure, and omitting a control for age. This strategy relies on assumptions that one of the three terms is unrelated to the outcome and may be safely omitted, or that the relationship between at least one of the three terms and the outcome follows a predetermined non-linear functional form.

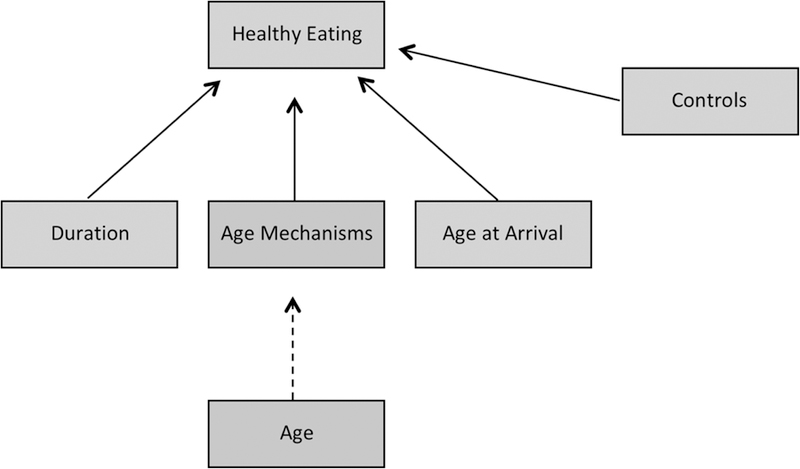

Rather than dropping one of the terms or making assumptions about their functional forms, we use Winship and Harding’s (2008) mechanism-based approach for identifying age-period-cohort (APC) models because the linear dependency among age at arrival, duration of residence, and age is akin to that of age, period, and cohort. Their approach weakens the linear dependency among the three temporal variables by specifying at least one of them—in our case, age—as operating indirectly through theoretically-informed mechanisms (Mik). This is illustrated by the solid and dashed paths in Figure 1ii and in the structural equation model below.

Figure 1.

Mechanism-based APC Model of Duration of U.S. Residence, Age at Arrival and Healthy Eating among Mexican-born Adults

| (solid paths) |

| (dashed path) |

This model assumes that age does not directly influence adults’ diets but instead operates through the age mechanisms. For example, young adults may consume less healthy diets than older adults not because of age per se, but because they tend to lead busy lives due to work and children and have less time to cook; they are healthier and less likely to be on special diets for medical reasons; and younger generations have greater preference for unhealthy foods like soda and snacks given greater access to such foods in their youth. Of course, there remain sharp disagreements about how to best address the collinearity problem (e.g., Bell and Jones 2014; Reither et al. 2015; Yang and Land 2013; Luo 2013), and the method we selected rests on assumptions just as other methods do. Nevertheless, we support our assumptions with a series of robustness tests described later and in Appendix 3.

Measures

We describe the analytic sample in Table 1. Our dependent variable, healthy eating, was measured by the 2010 Healthy Eating Index (HEI), which is a validated scale ranging from 1 to 100 indicating the degree to which respondent’s reported intake conforms to the guidelines recommended by the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion (Guenther et al. 2014). Points are given for adequate consumption of healthy foods and limited consumption of refined grains, sodium and empty caloriesiii. We used SAS code provided by the National Cancer Institute (http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/tools/hei/tools.html) to construct the HEI-2010 index for all adults in the sample. We averaged the dietary outcomes across both recall days for the 68% of the respondents who completed both days of dietary recall. For the remaining respondents, we used only the day 1 data.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Measure | Mean or Percentage | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy Eating (HEI-2010) | 50.61 | 11.50 |

| Duration of residence (years) | 17.28 | 11.78 |

| Age at arrival (%) | ||

| 0–23 months | 6.01 | |

| 2–5 years | 2.09 | |

| 6–12 years | 5.58 | |

| 13–18 years | 19.62 | |

| 19–24 years | 27.32 | |

| 25+ years | 39.38 | |

| Age Mechanisms | ||

| Marital Status (%) | ||

| Married | 65.28 | |

| Widowed | 1.88 | |

| Divorced | 3.46 | |

| Separated | 6.34 | |

| Never Married | 11.87 | |

| Cohabiting | 11.16 | |

| Family Size | 4.34 | 1.69 |

| Employment status/hours (%) | ||

| Not Employed | 31.47 | |

| 1–19 hours/week | 2.65 | |

| 20–34 hours/week | 9.44 | |

| 35+ hours/week | 56.44 | |

| Self-assessed health (%) | ||

| Excellent | 9.84 | |

| Very Good | 12.77 | |

| Good | 41.63 | |

| Fair | 31.00 | |

| Poor | 4.75 | |

| Height (standardized within sex) | −0.70 | 0.87 |

| Cohort-specific U.S. healthy eating | 46.78 | 2.46 |

| Childhood food environment | 25.84 | 3.21 |

| Controls | ||

| Immigration/Assimilation | ||

| English interview | 36.74 | |

| U.S. citizen | 21.81 | |

| Percent foreign-born in census tract | 26.93 | 15.47 |

| Food Similarity Index | 33.62 | 23.22 |

| Educational attainment (%) | ||

| Did not complete HS | 45.23 | |

| HS graduate | 22.86 | |

| Some college | 16.65 | |

| College graduate | 15.26 | |

| Income to poverty ratio | 1.55 | 1.15 |

| Female (%) | 46.45 | |

| Year (%) | ||

| 1999/00 | 9.38 | |

| 2001/02 | 12.38 | |

| 2003/04 | 12.90 | |

| 2005/06 | 15.80 | |

| 2007/08 | 15.81 | |

| 2009/10 | 17.15 | |

| 2011/12 | 16.57 | |

| Dietary recall days on weekend (%) | ||

| 0 | 55.44 | |

| 1 | 32.11 | |

| 2 | 12.45 | |

| Completed both dietary recall days (%) | 68.02 | |

Data Source: 1999–2012 Continuous NHANES

Sample: Mexican foreign-born adults age 25–64 (N = 2,780)

Our key independent variables, age at arrival and duration of residence, were constructed from the month and year of the respondent’s birth, when the respondent came “to the U.S. to stay,” and the NHANES interview. We categorized age at arrival to correspond with our theoretical ideas about infancy, preschool, and the school-aged years, and in accordance with commonly recognized periods of child development in obesity research (Ogden et al. 2014). We distinguished among those who arrived during infancy and toddlerhood (0–23 months), preschool years (age 2–5), school age (age 6–12), adolescence (age 13–18), young adulthood (age 19–24) and adulthood (25+). We treated duration of U.S. residence as a quadratic term (i.e., a linear and squared term) to capture nonlinear associations with healthy eating.

We selected age mechanisms to “stand in” for age and mediate the association between age and healthy eating as much as possible. No single mechanism fully captures age effects, so we incorporated several. We selected household and family structure because the presence of a spouse and children is related to both age and eating behaviors. We also included marital status and family size. Marital status helps us distinguish among young adults (who are more likely to cohabit or be never married), adults in their 30s and 40s (who are more likely to be currently or formerly married), and older adults (who are more likely to be widowed). We selected employment (working zero, 1–19, 20–34 hours/week, 35 or more hours/week) because younger adults are more likely to be employed and work longer hours than older people, and it influences how often people eat outside the home and how much time or energy they have for cooking.iv We also selected two indicators of health. Self-assessed health (excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor health) taps aging processes that could lead to dietary restrictions, medication use, and limited independence. Height (percentile within sex) is related to stunting, inadequate nutrition, and poor health in childhood (Lynch and Davey Smith 2005), and is related to age because childhood stunting has been declining in and therefore more common among older people in Mexico (Rivera, Irizarry, and Cossío 2009).

Finally, we selected two age mechanisms that are related to the fact that older people were raised in earlier eras and may therefore have different eating habits than younger people. The first, cohort-specific U.S. healthy eating, is the diet quality immigrants would have if they were similar to their U.S.-born counterparts born in the same year. To create it, we used NHANES data to estimate an OLS regression model among U.S.-born adults predicting healthy eating as a function of single-year dummies for year of birth, race/ethnicity, and gender, and used the coefficients to generate predicted values for the foreign-born adults in our sample. The second, childhood food environment, is the percentage of sweeteners and animal proteins (kcal) consumed by the population in Mexico in the year of the respondent’s birth (Food and Agricultural Association of the United Nations 2016). This measure is related to age because older immigrants were more likely to have grown up in pre-nutrition transition food environments than younger immigrants. This measure was available from 1961 to the present; we used 1961 values for immigrants born before 1961.

For analyses in which we test our second hypothesis about the moderating role of family SES, we created a single composite measure of family SES based on the respondent’s educational attainment (years) and the family’s income-to-poverty ratio. These measures were standardized and averaged for each respondent to yield a continuous, standardized measure of SES (mean = 0; SD = 1).

Finally, we controlled for several confounders: educational attainment, family income-to-poverty ratio, gender, year of survey, whether the dietary recalls occurred on a weekend, and whether the respondent completed one or two dietary recall days. Educational attainment and family income-to-poverty ratio were replaced by the composite SES measure in models that tested the SES and duration interaction. Some models also controlled for indicators of acculturation: English language of interview, U.S. citizenship, the food similarity index and the percentage of foreign-born in the respondent’s census tract. The food similarity index indicates the similarity of the foods consumed by individuals to the foods most commonly consumed by U.S-born adults (Van Hook, Quiros, and Frisco 2015).

Analysis

We first estimated mean levels of healthy eating by age at arrival and duration of residence (Table 2). Next, we assessed hypotheses 1 and 3 by estimating the mechanism-based APC model shown in Figure 1 using Stata’s Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) package. The coefficients for all paths can be found in Appendix Table 1 (paths with the dashed arrow) and Appendix Table 2 (paths with the solid arrows). The total estimated effects of age, age at arrival, and duration are summarized in Table 3. We estimated the total age effects by summing the indirect effects of age across all paths, using the non-linear combination post-estimation commands in Stata. We assessed Hypothesis 2 by testing the significance of interaction terms between duration of residence and family SES. Finally, we conducted a series of sensitivity tests and displayed the results in Tables 4 and 5 and Appendix 3.

Table 2.

Healthy Eating by Age at Arrival and Duration of U.S. Residence

| Mean | N | |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of Residence | ||

| 0–4 | 49.4 | 327 |

| 5–9 | 49.9 | 458 |

| 10–14 | 52.0 | 428 |

| 15–19 | 50.5 | 362 |

| 20+ | 50.8 | 1,205 |

| Age at Arrival | ||

| 0–23 months | 48.7 | 136 |

| 2–5 | 47.5 | 64 |

| 6–12 | 46.3 | 136 |

| 13–18 | 50.3 | 509 |

| 19–24 | 51.2 | 730 |

| 25+ | 51.4 | 1205 |

Data and Sample: See Table 1

Table 3.

Estimated Effects of Duration of Residence and Age at Arrival on Healthy Eating (coefficients; SEs in parentheses)

| Duration of Residence | 0.209 | * | (0.088) |

| Duration-squared | −0.003 | + | (0.002) |

| Age at Arrival (Ref = age 25+) | |||

| 0–23 months | −3.119 | (2.325) | |

| 2–5 years | −4.929 | * | (2.123) |

| 6–12 years | −6.074 | *** | (1.829) |

| 13–18 years | −1.066 | (1.063) | |

| 19–24 years | −0.075 | (0.915) |

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05

p<.10

Note: Model includes all controls and age mechanisms. The complete SEM model is shown in Appendix Tables 1 and 2.

Table 4.

Effects of Duration and Residence and Age at Arrival on Healthy Eating Across Multiple SEM Model Specifications (coefficients; SEs in parentheses)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | ||||||||

| Duration of Residence | 0.209 | ** | 0.150 | + | 0.141 | + | 0.157 | + | |||

| (0.088) | (0.079) | (0.077) | (0.094) | ||||||||

| Duration-squared | −0.003 | + | −0.004 | ** | −0.004 | * | −0.004 | ** | |||

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | ||||||||

| Treated as direct (x) or indirect (--) | |||||||||||

| Age | -- | x | -- | x | |||||||

| Age at Arrival | x | -- | -- | x | |||||||

| Duration | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Age of Arrival (Ref =age 25+) | |||||||||||

| 0–23 | −3.119 | −1.645 | −1.695 | −0.623 | |||||||

| (2.325) | (1.737) | (1.753) | (2.394) | ||||||||

| 2–5 | −4.929 | * | −3.251 | * | −3.569 | * | −2.671 | ||||

| (2.123) | (1.682) | (1.679) | (2.263) | ||||||||

| 6–12 | −6.074 | *** | −4.274 | ** | −4.607 | ** | −4.291 | * | |||

| (1.829) | (1.474) | (1.499) | (1.921) | ||||||||

| 13–18 | −1.066 | 0.575 | 0.130 | 0.338 | |||||||

| (1.063) | (0.808) | (0.806) | (1.182) | ||||||||

| 19–24 | −0.075 | 0.946 | 0.770 | 0.787 | |||||||

| (0.915) | (0.738) | (0.747) | (0.956) | ||||||||

| Treated as direct (x) or indirect (--) | |||||||||||

| Age | -- | x | -- | x | |||||||

| Age at Arrival | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Duration | x | -- | -- | x | |||||||

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05

p<.10

Table 5.

Sensitivity Tests of Estimated Effects of Duration and Residence and Age at Arrival on Healthy Eating (coefficients; SEs in parentheses)

| Original Model (Table 3) | Age treated as linear function | Excludes Assim Controls | Excludes SES Controls | Women | Men | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of Residence | 0.209 | * | 0.209 | * | 0.155 | + | 0.193 | * | 0.194 | 0.269 | * | |||||

| (0.088) | (0.088) | (0.086) | (0.089) | (0.128) | (0.118) | |||||||||||

| Duration-squared | −0.003 | + | −0.003 | + | −0.003 | −0.003 | + | −0.003 | −0.004 | + | ||||||

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |||||||||||

| Age of Arrival (Ref = age 25+) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0–23 months | −3.119 | −3.119 | −2.873 | −3.307 | −5.007 | −1.711 | ||||||||||

| (2.325) | (2.325) | (2.409) | (2.355) | (3.443) | (2.786) | |||||||||||

| 2–5 years | −4.929 | * | −4.929 | * | −5.504 | ** | −4.109 | * | −4.740 | −5.675 | + | |||||

| (2.123) | (2.123) | (2.144) | (2.070) | (2.971) | (2.994) | |||||||||||

| 6–12 years | −6.074 | *** | −6.074 | *** | −6.123 | *** | −5.878 | ** | −6.494 | ** | −6.067 | ** | ||||

| (1.829) | (1.829) | (1.885) | (1.863) | (2.574) | (2.390) | |||||||||||

| 13–18 years | −1.066 | −1.066 | −0.840 | −1.267 | −0.964 | −1.575 | ||||||||||

| (1.063) | (1.063) | (1.074) | (1.062) | (1.607) | (1.377) | |||||||||||

| 19–24 years | −0.075 | −0.075 | −0.011 | −0.086 | −0.414 | −0.389 | ||||||||||

| (0.915) | (0.915) | (0.933) | (0.915) | (1.328) | (1.201) | |||||||||||

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05

p<.10

We conducted all analyses in Stata 14.0. All models were weighted and standard errors were adjusted to account for the NHANES clustered sample design.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

As shown in Table 2, the relationship between duration of residence and healthy eating is modest and nonlinear (top panel). It rises slightly from 49.4 among those with less than five years of residence to 52.0 among those with 10–14 years of residence but falls to around 50.5 among those with more than 15 years of residence. The relationship between age at arrival and healthy eating is also nonlinear but somewhat stronger (bottom panel). Healthy eating worsens with increasing age at arrival among those who arrived as infants and preschoolers, is lowest among those who arrived during school age (age 6–12) and increases with age at arrival among those arriving in adolescence and adulthood. Those who arrived as young adults (age 19–24) and adults (age 25+) have the healthiest diets. These results are consistent with Hypothesis 3b in that arrival during the school-aged years appears to be particularly influential.

Multivariate Analyses

We next turn to the mechanism-based APC model estimates, which adjust for age mechanisms and other confounders. We show the full model in Appendix Tables 1 and 2, and summarize the results for duration of residence and age at arrival in Table 3. Age is related to each of the age mechanisms except height (Appendix Table 1), and in turn, many of the age mechanisms, including being separated (compared with married) and not being in excellent health are related to less healthy eating (Appendix Table 2)v. Net of the age mechanisms and controls, healthy eating increases with duration of residence but at a decreasing rate, as indicated by a positive coefficient for the linear term (b = .209; p<.05) and a negative coefficient for the squared term (b = −.003; p<.10; see Table 3). To interpret the results, we evaluated the association of duration with healthy eating at different values, and we see that during the first five years of residence, the healthy eating index is predicted to increase by .96 points. It is predicted to increase by another .80 points between 5 and 10 years of residence, by 0.64 points between 10 and 15 years, and by 0.48 points between 15 and 20 years, totaling 2.9 points over 20 years. For a respondent on a 2000-calorie diet, a 2.9-point increase would correspond with about 86 fewer “empty” calories from fat, alcohol, and added sugar per day (equivalent to about 8 potato chips). This may seem small, but the cumulative effects are noticeable. For a 180 lb. woman, 86 fewer calories per day translates into a 9 lb. weight loss over one year. This finding is inconsistent with Hypothesis 1, which predicts a negative association between duration and healthy eating.

However, we do find support for the idea that migration during childhood is associated with unhealthy eating (Hypothesis 3). Those who arrived during pre-school (2–5) and school ages (6–11) have significantly less healthy diets than those who arrived as adults (age 25+). Consistent with Hypothesis 3b, immigrants who arrived during school-aged years are particularly disadvantaged and have healthy eating scores that are lower than all other age-at-arrival groups (p<.05 for all comparisons except with infants). They are about 6 points lower than adult arrivals, corresponding with an additional 180 empty calories per day (equivalent to about one soda). If a 150 lb. woman consumed 180 calories per day beyond the amount needed to maintain her weight, she would gain 19 lbs. in a year. No other factor in the model was as important as age at arrival, including duration of residence.

Socioeconomic Status

We next assessed Hypothesis 2. We tested an interaction term between duration of residence and family SES to evaluate whether the relationship between duration and healthy eating differed by the respondent’s level of disadvantage. SES was positively associated with healthy eating, but the interaction was not statistically significant (p > .10), providing no support for Hypothesis 2. We also tested interactions between duration and other functional forms of SES (quadratic, categorical), educational attainment, and income-to-poverty ratio, and none were statistically significant. This was somewhat surprising, but it is important to note that SES (and especially educational attainment, as shown in Appendix Table 2) was positively associated with healthy eating. Thus, even though lower SES immigrants are at greater risk for unhealthy eating than higher SES immigrants, this difference does not widen (or narrow) with duration.

Robustness and Sensitivity Tests

We conducted many robustness and sensitivity tests. We first tested the assumption that the age mechanisms completely mediate the effects of age on healthy eating. We checked whether the age mechanisms explain a large share of the variance in age, and they did. In a model predicting age as a function of the age mechanisms, the R-square was .76. We also checked whether the age mechanisms mediated the effects of age on healthy eating, and again, they did. Age was not a significant predictor of healthy eating in models that included both age and the age mechanisms, regardless of whether we treated age as a linear or quadratic function. Finally, we estimated alternative mechanism-based APC models in which we altered which of the temporal variables – age, age at arrival, or duration – was treated as indirectly influencing healthy eating.vi We show the estimated effects of age at arrival and duration across the multiple specifications in Table 4. The results are consistent across all specifications, although the duration effects are weaker and lose significance in models that treat age at arrival as operating indirectly through mechanisms.

We next tested whether the results are sensitive to whether age is treated as a linear or quadratic function. We also wondered whether the effects of duration or age at arrival were “over-controlled” by the inclusion of the assimilation indicators and SES (given that assimilation and SES tend to increase by duration and for younger ages of arrival), so we estimated models that excluded them. Finally, we estimated separate models for men and women. The results, shown in Table 5, are consistent across all specifications and between men and women.

We then assessed whether the relationship between duration and healthy eating differed between child and adult arrivals. Interactions between duration of residence and age at arrival were not significant, meaning that the relationship between duration of residence and healthy eating was positive for both child and adult arrivals.

Finally, we examined other outcomes with clear theoretical links to age at arrival and duration of residence to show proof of concept for the mechanism-based APC method. First, we modeled education and height. We expected strong age-at-arrival effects because both education and height are established in childhood or adolescence, and weak duration effects because education and height tend not to increase for adults following migration. Second, we modeled English proficiency, an outcome for which both duration and age at arrival are likely to be important. As immigrants spend time in the U.S., they practice English and become more proficient, and those who arrived as children are likely to attain particularly high proficiency levels. Finally, we compared the results about healthy eating with a related outcome, weight gain, to see if the results were consistent. In all three cases, the results were consistent with our expectations, giving us greater confidence in the APC modeling method (see Appendix 3).

Discussion

The health burden of life in the U.S. on immigrants is well documented and is largely thought to accumulate with duration of U.S. residence. Less attention has been paid to the role of age at arrival in the U.S. Disentangling these two dimensions of U.S. residence is critical for understanding health assimilation processes. If the negative effect of U.S. residence is more strongly related to migration in childhood than to duration of residence, the focus of future research and policy should shift interventions toward children’s experiences in the migration and settlement process (Ben-Shlomo and Kuh 2002; Spallek, Zeeb, and Razum 2011).

Yet, methodological challenges stemming from the collinearity among duration of residence, age at arrival, and age have impeded understanding of immigrants’ healthy eating patterns and other health behaviors. Most of what is known about the association between U.S. residence and health behaviors is based on separate evaluations of duration of residence and age at arrival. In this study, we used mechanism-based APC models to overcome the linear dependency between duration of residence, age at arrival, and age and assess the independent effects of duration of residence and age at arrival on healthy eating among Mexican immigrant adults. This technique led to two key findings that reveal the lifelong health risks of childhood migration and a surprising pattern in which healthy eating improves with time in the U.S.

First, arrival in middle childhood, compared with arrival in infancy, adolescence, or adulthood, was associated with less healthy eating in adulthood. This pattern is consistent with Hypothesis 3b and points to the potential role of schools as health-shaping institutions. Immigrants who arrived between the ages of 6 and 11 would have attended school as the “new kid” and therefore may have had to make rapid adjustments and endured social pressures to hide or shed “foreign” ways of eating. It is possible that their status as societal outsiders during a sensitive age may have contributed to pressures to conform and adopt unhealthy American eating behaviors. In contrast, immigrants who arrived as infants had much healthier diets. Relatively few Mexican immigrants attend pre-school (Crosnoe 2007), so these immigrants may have experienced a protective period during which they were largely in the home and in the care of their parents, and thus shielded from external stressors associated with the concurrence of immigration and school entry. Immigrants who arrived in adolescence also had healthier diets. They would have spent less time in U.S. schools than those who arrived in middle childhood, and a large share of adolescent immigrants completed their schooling in Mexico and never even attended U.S. schools (Oropesa and Landale 2009).

Second, once we adjusted for the negative effects of migration during childhood, longer duration of U.S. residence was not associated with less healthy diets as previous research has often reported. In fact, longer duration of U.S. residence was associated with healthier diets regardless of SES. This finding may seem surprising but it is consistent with other research showing that immigrants gain resources with greater time in the country, such as English language proficiency (Stevens 1999), earnings (Lubotsky 2007), and access to health care (Leclere, Jensen and Biddlecom 1994). It also aligns with previous studies that found null or reduced effects of duration of residence on health after accounting for other temporal dimensions of U.S. residence (e.g., Teitler et al. 2015; Hamilton et al. 2015). This finding could reflect an adaptation process in which immigrants accumulate knowledge and resources over time, and ultimately, improve at navigating the U.S. food environment. Research that follows immigrants longitudinally would be helpful for better understanding how immigrants’ confidence, knowledge, and behaviors related to shopping and food consumption change over time.

Overall, our findings fit within a larger debate about why U.S. residence worsens health. The dominant explanation is that acculturation leads to the adoption of the American lifestyle. However, this idea has been strongly criticized in recent years for underemphasizing the stress and hazards associated with many immigrants’ low socioeconomic position, discrimination, and work (Viruell-Fuentes, Miranda, and Abdulrahim 2012). Backing this view is research showing that societal outsiders, such as non-citizens (Gubernskaya, Bean, and Van Hook 2013), and those with low socioeconomic status (Martin, Van Hook, and Quiros 2015), appear to be particularly vulnerable to unhealthy assimilation and that low social-structural position and social exclusion – not greater duration of residence or acculturation per se – may the key factor responsible for immigrants’ health declines (Riosmena et al. 2015). The research we present here supports this idea. Duration of residence is not associated with worse diet quality. Rather, migration during sensitive periods of childhood—when the effects of being a societal outsider may be amplified—appears to raise immigrants’ health risks.

Our study has limitations. Although robustness tests reveal consistent results across specifications, the Winship-Harding mechanism-based APC model does not completely resolve linear dependency and may be sensitive to the assumptions used. Second, our data exclude childhood circumstances (i.e. parental, school, and neighborhood characteristics, and place of residence) of the adults in our sample. Thus, it is possible that we saw no significant interaction effect between SES and duration of residence because our SES measure captures family SES at the time of the interview, not during the years when immigrants arrived and were adjusting to life in the U.S. A third limitation is that the healthy eating index is based on two 24-hour dietary recalls, which have been criticized for their susceptibility to recall bias and measurement error because of a limited observation period (Dhurandhar et al. 2015). Despite these criticisms, 24-hour dietary recalls remain the best known method for collecting dietary data from large samples of individuals, and measurement errors in large samples are likely to balance out (Subar et al. 2015).

Limitations notwithstanding, our findings concerning age at arrival and duration of residence are robust and question assumptions that healthy eating declines with increasing duration of U.S. residence. Instead, they suggest that the negative influence of U.S. residence on healthy eating may be anchored to migration during socially sensitive periods in childhood. This finding has implications for public health policy; it suggests that healthy eating interventions for Mexican immigrant children, a population with a relatively high obesity prevalence (Van Hook et al. 2009), might be most needed and effective during sensitive periods in childhood. Our findings also carry implications for future research on immigrant health. Although our study focused on one health behavior, healthy eating, our theoretical argument and methodological technique are applicable to future research on immigrant health more broadly. For example, both the timing of sensitive periods and the relative roles of age at arrival and duration of residence could vary across health outcomes. While some health outcomes are more strongly tied to childhood experiences and the long-term health habits formed in childhood or adolescence (e.g., healthy eating, smoking), others may accumulate later in life due to prolonged physical wear and tear or stress (e.g., functional limitations). Thus, we hope the results of this study will not only motivate future data collection and research on how childhood experiences affect immigrants’ health trajectories, but also encourage researchers to examine the most theoretically relevant dimension(s) of U.S. residence for a given health outcome.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R24 HD041025 and P01 HD062498). We analyzed restricted data provided by the National Center for Health Statistics in the Pennsylvania State University Federal Statistical Research Data Center. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Data Center, the National Center for Health Statistics, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Appendix Table 1.

Paths linking age to age mechanisms (each row is a separate path, estimates are coefficients, and SEs in parentheses)

| Intercept | Age Coefficient | Age2 coefficient | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Mechanisms (Dep Vars) | ||||||

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Widowed | 0.112 | * | −0.006 | * | 0.000 | ** |

| (0.055) | (0.003) | (0.000) | ||||

| Divorced | 0.008 | −0.001 | 0.000 | |||

| (0.060) | (0.003) | (0.000) | ||||

| Separated | −0.045 | 0.004 | 0.000 | |||

| (0.083) | (0.004) | (0.000) | ||||

| Never Married | 0.929 | *** | −0.035 | *** | 0.000 | *** |

| (0.186) | (0.008) | (0.000) | ||||

| Cohabiting | 0.321 | ** | −0.006 | 0.000 | ||

| (0.134) | (0.006) | (0.000) | ||||

| Family Size | 2.445 | *** | 0.110 | *** | −0.001 | *** |

| (0.709) | (0.034) | (0.000) | ||||

| Employment status/hours | ||||||

| 1–19 hours/week | −0.011 | 0.001 | 0.000 | |||

| (0.053) | (0.003) | (0.000) | ||||

| 20–34 hours/week | 0.228 | + | −0.005 | 0.000 | ||

| (0.127) | (0.006) | (0.000) | ||||

| 35+ hours/week | −0.281 | 0.047 | *** | −0.001 | *** | |

| (0.212) | (0.010) | (0.000) | ||||

| Self-assessed health | ||||||

| Very Good | 0.176 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| (0.132) | (0.006) | (0.000) | ||||

| Good | 0.220 | 0.016 | 0.000 | * | ||

| (0.216) | (0.010) | (0.000) | ||||

| Fair | 0.194 | −0.001 | 0.000 | |||

| (0.192) | (0.009) | (0.000) | ||||

| Poor | 0.123 | −0.008 | + | 0.000 | ** | |

| (0.087) | (0.005) | (0.000) | ||||

| Height | −0.446 | −0.004 | 0.000 | |||

| (0.377) | (0.018) | (0.000) | ||||

| Cohort-specific healthy eating | 46.082 | *** | −0.149 | *** | 0.004 | *** |

| (0.681) | (0.033) | (0.000) | ||||

| Childhood food environment | 53.689 | *** | −1.155 | *** | 0.011 | *** |

| (0.524) | (0.025) | (0.000) | ||||

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05

p<.10

Appendix Table 2.

Paths linking age mechanisms, duration, age at arrival, and controls to healthy eating (coefficients; SEs in parentheses)

| Duration of residence (years) | 0.209 | * | † | (0.088) | ||

| --squared | −0.003 | + | (0.002) | |||

| Age at arrival (ref = age 25+) | ||||||

| 0–23 months | −3.119 | b | † | (2.325) | ||

| 2–5 years | −4.929 | * | ac | (2.123) | ||

| 6–12 years | −6.074 | *** | b | (1.829) | ||

| 13–18 years | −1.066 | bc | (1.063) | |||

| 19–24 years | −0.075 | abc | (0.915) | |||

| Age Mechanisms | ||||||

| Marital Status (ref = married) | ||||||

| Widowed | −2.529 | (1.688) | ||||

| Divorced | −2.167 | (1.592) | ||||

| Separated | −2.808 | ** | (1.079) | |||

| Never Married | −0.075 | (1.000) | ||||

| Cohabiting | 1.459 | (0.931) | ||||

| Family Size | 0.156 | (0.175) | ||||

| Employment status/hours (ref=not employed) | ||||||

| 1–19 hours/week | −0.616 | (1.700) | ||||

| 20–34 hours/week | −1.374 | (1.059) | ||||

| 35+ hours/week | −0.993 | (0.699) | ||||

| Self-assessed health (ref=excellent) | ||||||

| Very Good | −3.927 | ** | (1.269) | |||

| Good | −3.913 | *** | (1.144) | |||

| Fair | −2.296 | + | (1.208) | |||

| Poor | −3.072 | (1.973) | ||||

| Height | −0.496 | (0.347) | ||||

| Cohort-specific healthy eating | 0.304 | (0.197) | ||||

| Childhood food environment | −0.120 | (0.149) | ||||

| Controls | ||||||

| Assimilation | ||||||

| English interview | 0.111 | (1.028) | ||||

| U.S. citizen | −0.514 | (0.837) | ||||

| % foreign-born in census tract | 0.029 | (0.018) | ||||

| Food Similarity Index | −0.072 | *** | (0.013) | |||

| Educ. attainment (ref=college grad) | ||||||

| Did not complete HS | −3.078 | ** | (0.979) | |||

| HS graduate | −2.745 | ** | (0.985) | |||

| Some college | −2.642 | ** | (1.030) | |||

| Income to poverty ratio | 0.389 | (0.304) | ||||

| Female | 1.938 | ** | (0.733) | |||

| Year (ref=1999/00) | ||||||

| 2001/02 | 1.694 | (1.091) | ||||

| 2003/04 | −2.420 | (1.841) | ||||

| 2005/06 | 1.930 | (1.673) | ||||

| 2007/08 | 1.973 | (1.570) | ||||

| 2009/10 | 1.736 | (1.573) | ||||

| 2011/12 | 2.010 | (1.702) | ||||

| Dietary recall days on weekend (ref=0) | ||||||

| 1 | −0.330 | (0.695) | ||||

| 2 | −3.282 | *** | (0.744) | |||

| Completed both dietary recall days | −1.013 | (1.127) | ||||

| Intercept | 43.351 | *** | (11.293) | |||

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05

p<.10

significant as a group (age at arrival categories, and duration polynomial)

significantly different from those who arrived age 0–23 months

significantly different from those who arrived age 2–5 years

significantly different from those who arrived age 6–12 years

Appendix 3. Tests of the Mechanism-based APC Model

We tested the mechanism-based APC approach by applying it to outcomes with unambiguous theoretical links to age at arrival and duration of residence for a sample of Mexican-born adults ages 25–6. For each outcome, we estimated the effects of duration net of the controls and age mechanisms in model 1 and added age at arrival in model 2.

First, we tested the method for two outcomes that are fixed in childhood/adolescence: education and height. We expected strong age-at-migration effects because both education and height are established in childhood, and immigrants who arrived as children would have more schooling opportunities and less food insecurity while they were growing up than immigrants who arrived in adulthood. We also expected weak or nonexistent duration effects because education and (especially) height tend not to increase for adults following migration. Model 1 showed that the effects of duration were positive and significant for both outcomes. Clearly, Model 1 was mis-specified for the reasons just mentioned. However, once we added age at arrival (Model 2), the results are much more plausible. The duration effects dropped in magnitude and became insignificant, and arrival at younger ages is associated with more education and greater height in adulthood. These results illustrate how not accounting for age at arrival can lead to misleading duration effects.

We next examined an outcome that is theoretically linked to both duration and age at arrival: English proficiency. As immigrants spend time in the U.S., they practice English and become more proficient, and immigrants who arrived as children are likely to have attained particularly high English proficiency. The results in Model 2 confirm these expectations. English proficiency increases with longer duration in the U.S. and is higher for those arriving as children. Significant duration effects remain after adjusting for age at arrival, which is consistent with common understandings of second language acquisition and with other research on this topic (Stevens 1999).

Finally, we compared the results for healthy eating with a related outcome, weight gain (i.e., change in BMI in the past decade). Results were consistent with our findings on healthy eating. Immigrants tended to gain the most weight when they first arrived in the country, but then gained comparably less weight with greater time in the country. This is consistent with the finding that immigrants’ diets become healthier with time in the country. Additionally, immigrants who arrived as children (particularly those arriving before age 12) gained the most weight as adults. Again, this is consistent with our findings that immigrants who arrived as children have the least healthy diets.

Appendix Table 3.

Duration and age at arrival effects in mechanism-based APC models for various outcomes (coefficients; SEs in parentheses)

| Years of Educationa | Height (cm)b | English Proficiencya | 10-year BMI gain b | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||

| Duration of U.S. residence | 0.041 | *** | −0.001 | 0.063 | *** | 0.015 | 0.042 | *** | 0.022 | *** | −0.008 | −0.053 | ** | |||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.013) | (0.027) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.009) | (0.015) | |||||||||

| Age at arrival (25+ = ref.) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0–4 | 2.321 | *** | 1.4151 | 0.926 | *** | 1.9166 | *** | |||||||||

| (0.033) | (1.024) | (0.009) | (0.652) | |||||||||||||

| 5–11 | 1.655 | *** | 2.1286 | * | 0.761 | *** | 1.9029 | ** | ||||||||

| (0.027) | (0.827) | (0.007) | (0.547) | |||||||||||||

| 12–17 | −0.085 | *** | 1.5315 | * | 0.242 | *** | 1.3539 | ** | ||||||||

| (0.020) | (0.654) | (0.005) | (0.429) | |||||||||||||

| 18–24 | −0.157 | *** | 0.8166 | + | 0.046 | *** | 0.8437 | ** | ||||||||

| (0.015) | (0.471) | (0.004) | (0.308) | |||||||||||||

2008–2016 American Community Survey (N= 631,579)

1999–2009 Continuous NHANES (N=2,780)

Samples restricted to Mexican-born adults ages 25–64. All models include controls for gender and year, and a set of age mechanisms (marital status, self-rated health (for NHANES), functional limitations (for ACS), educational attainment, and birth cohort-specific means of the dependent variable among U.S.-born persons).

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05

p<.10

Footnotes

Endnotes

Author’s analysis of the 2015 American Community Survey (Steven Ruggles, Katie Genadek, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, and Matthew Sobek. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 6.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2015. http://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V6.0.)

This model is not intended to depict a comprehensive behavioral process so it does not estimate all possible paths among the independent variables. Rather, it is designed to weaken the collinearity among the three temporal variables. Treating age this way allows the relationship between age and healthy eating to be nonlinear but does not impose a particular functional form. Instead, the shape of the function is determined by the ways that age is related to the mechanisms and in turn, how the mechanisms are related to healthy eating.

HEI has twelve subcomponents. Nine measure adequate consumption of healthy foods, including total fruit (5 points), whole fruit (5 points), total vegetables (5 points), greens and beans (5 points), whole grains (10 points), dairy (10 points), protein (5 points), seafood and plant proteins (5 points), and fatty acids (10 points). Three other subcomponents measure moderate consumption of refined grains (10 points), sodium (10 points), and empty calories (20 points). Partial scores are given for partial adherence, and higher values indicate a healthier diet. For example, an adult who consumed the recommended amounts of total fruit (5), whole fruit (5), whole grains (10), proteins (5), and fatty acids (10); no vegetables (0) and greens and beans (0); only half the recommended seafood and plant proteins (2.5); less than the recommended limit of refined grains (10) and sodium (10); and more than the maximum recommended empty calories (0), would have an HEI score of about 57.5.

Interaction terms between gender and employment were not significant and therefore excluded from the final models (available upon request). Additionally, results were the same regardless of whether employment was treated as an age mechanism, control, or omitted from the model.

Interestingly, employment status, family size, income-to-poverty ratio, and several acculturation indicators (English language usage, citizenship, and percentage foreign-born in the census tract) were unrelated to healthy eating net of the other independent variables.

In these analyses, age at arrival mechanisms included educational attainment, English language of interview, U.S. citizenship, and the food similarity index. Duration mechanisms included English language of interview, U.S. citizenship, the food similarity index, income-to-poverty ratio and the share of foreign-born in the respondent’s census tract.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Van Hook, Professor of Sociology and Demography, Population Research Institute, The Pennsylvania State University.

Susana Quiros, Sociology and Demography PhD Student, Population Research Institute, Pennsylvania State University.

Molly Dondero, Assistant Professor of Sociology, American University.

Claire E. Altman, Department of Health Sciences and the Truman School of Public Affairs, University of Missouri.

References

- Abraído-Lanza Ana F., Chao Maria T., and Flórez Karen R.. 2005. “Do Healthy Behaviors Decline with Greater Acculturation?: Implications for the Latino Mortality Paradox.” Social Science & Medicine 61(6):1243–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akresh Ilana. 2007. “Dietary Assimilation and Health among Hispanic Immigrants to the United States.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 48(4):404–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antecol Heather, and Bedard Kelly. 2006. “Unhealthy assimilation: why do immigrants converge to American health status levels?.” Demography 43(2): 337–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala Guadalupe X., Baquero Barbara, and Klinger Sylvia. 2008. “A Systematic Review of the Relationship between Acculturation and Diet among Latinos in the United States: Implications for Future Research.” Journal of the American Dietetic Association 108(8):1330–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batis C, Hernandez-Barrera L, Barquera S, Rivera JA, and Popkin BM. 2011. “Food Acculturation Drives Dietary Differences among Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and Non-Hispanic Whites.” The Journal of nutrition 141(10):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barquera Simón et al. 2009. “Obesity and Central Adiposity in Mexican Adults : Results from the Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey 2006.” Salud Pública de México 51(S4):S595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner Erin, Frisco Michelle, and Van Hook Jennifer. 2017. Population Association of America, Chicago, IL. Elementary Schools as a Context of Vulnerability for Weight Gain Among Hispanic Children of Immigrants

- Bell Andrew and Jones Kelvyn. 2014. “Another ‘Futile Quest’? A Simulation Study of Yang and Land’s Hierarchical Age-Period-Cohort Model.” Demographic Research 30:333. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo Yoav and Kuh Diana. 2002b. “A Life Course Approach to Chronic Disease Epidemiology: Conceptual Models, Empirical Challenges and Interdisciplinary Perspectives.” International Journal of Epidemiology 31(2):285–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch Leann L. 1999. “Development of Food Preferences.” Annual Review of Nutrition 19(1):41–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch Leann L. and Fisher Jennifer O.. 1998. “Development of Eating Behaviors among Children and Adolescents.” Pediatrics 101(Supplement 2):539–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton Cynthia A., Moshfegh Alanna J., Baer David J., and Kretsch Mary J.. 2006. “The USDA Automated Multiple-Pass Method Accurately Estimates Group Total Energy and Nutrient Intake.” The Journal of Nutrition 136(June):2594–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley Hoyt, and Chin Aimee. 2010. “Age at arrival, English proficiency, and social assimilation among US immigrants.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2(1): 165–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Rachael and Ogden Jane. 2004. “Children’s Eating Attitudes and Behaviour : A Study of the Modelling and Control Theories of Parental Influence.” Health Education Research 19(3):261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe Robert. 2007. “Early Child Care and the School Readiness of Children from Mexican Immigrant Families.” International Migration Review 41(1):152–81. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos Cuy, Diana et al. 2013. “Examining the Diet of Post-Migrant Hispanic Males Using the Precede-Proceed Model: Predisposing, Reinforcing, and Enabling Dietary Factors.” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 45(2):109–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhurandhar NV et al. 2015. “Energy Balance Measurement: When Something Is Not Better than Nothing.” International Journal of Obesity 39(7):1109–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz Tamara, Subramanian SV, Acevedo-Garcia Dolores, Osypuk Theresa L., and Peterson Karen E.. 2008. “Individual and Neighborhood Differences in Diet Among Low-Income Foreign and U.S.-Born Women.” Women’s Health Issues 18(3):181–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley Thomas A., Baker Erin T., Futrell Lauren, and Rice Janet C.. 2010. “The Ubiquity of Energy-Dense Snack Foods: A National Multicity Study.” American Journal of Public Health 100(2):306–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal Katherine M., Carroll Margaret D., Ogden Cynthia L., and Johnson Clifford L.. 2002. “Prevalence Trends among US Adults, 1999–2000.” JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 288(14):1723–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agricultural Association of the United Nations. 2016. FAOSTAT database available online at http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home.

- Glick Jennifer E., Bates Littisha, and Yabiku Scott T.. 2009. “Mother’s age at arrival in the United States and early cognitive development.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 24(4): 367–380. [Google Scholar]

- Grieco Elizabeth. The Foreign-Born Population in the United States: 2010. 2012.

- Gubernskaya Zoya, Bean Frank D., and Van Hook Jennifer. 2013. “(Un) Healthy immigrant citizens: Naturalization and activity limitations in older age.” Journal of health and social behavior 54(4): 427–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman Maya D., Cheryan Sapna, and Monin Benoît. 2011. “Fitting In but Getting Fat: Identity Threat and Dietary Choices Among U.S. Immigrant Groups .” Psychological Science 22(7):959–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther Patricia M. et al. 2014. “The Healthy Eating Index-2010 Is a Valid and Reliable Measure of Diet Quality According to the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.” The Journal of Nutrition jn-113:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton Tod G., Palermo Tia, and Green Tiffany L.. 2015. “Health assimilation among Hispanic immigrants in the United States: The impact of ignoring arrival-cohort effects.” Journal of health and social behavior 56(4): 460–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill James O. and Peters John C.. 1998. “Environmental Contributions to the Obesity Epidemic.” Science 280(May):1374–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holub Christina K. et al. 2013. “Obesity Control in Latin American and U.S. Latinos: A Systematic Rreview.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 44(5):529–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclere Felicia B., Jensen Leif, and Biddlecom Ann E.. 1994. “Health care utilization, family context, and adaptation among immigrants to the United States.” Journal of health and social behavior 370–384. [PubMed]

- Lopez Lenny and Hill Golden Sherita. 2014. “A New Era in Understanding Diabetes Disparities Among U.S. Latinos - All Are Not Equal.” Diabetes Care 37:2081–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubotsky Darren. 2007. Chutes or ladders? A longitudinal analysis of immigrant earnings. Journal of Political Economy, 115(5), 820–867. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Liying. 2013. “Assessing Validity and Application Scope of the Intrinsic Estimator Approach to the Age-Period-Cohort Problem.” Demography 50(6):1945–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J and Davey Smith G. 2005. “A Life Course Approach to Chronic Disease Epidemiology.” Ann Rev Public Health 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Molly A., Van Hook Jennifer, and Quiros Susana. 2015. “Is Socioeconomic Incorporation Associated with a Healthier Diet ? Dietary Patterns among Mexican-Origin Children in the United States.” Social Science & Medicine 147:20–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky John and Ross Catherine E.. 2010. “Self-Direction toward Health: Overriding the Default American Lifestyle.” Pp. 235–50 in The Handbook of Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, edited by Suls JM, Davidson KW, and Kaplan RM. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nestle Marion. 2007. Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition, and Health Berkeley: Univ of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nicklaus Sophie, Boggio Vincent, Chabanet Claire, and Issanchou Sylvie. 2004. “A Prospective Study of Food Preferences in Childhood.” Food Quality and Preference 15:805–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden Cynthia L., Carroll Margaret D., Kit Brian K., and Flegal Katherine M.. 2014. “Prevalence of Childhood and Adult Obesity in the United States, 2011–2012.” JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 311(8):806–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oropesa RS and Nancy S Landale. 2009. “Why Do Immigrant Youths Who Never Enroll in U.S. Schools Matter? School Enrollment Among Mexicans and Non-Hispanic Whites.” Sociology of Education 82(3):240–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil Crystal L., Hadley Craig, and Djona Nahayo Perpetue. 2009. “Unpacking Dietary Acculturation among New Americans: Results from Formative Research with African Refugees.” Journal of immigrant and minority health / Center for Minority Public Health 11(5):342–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin Barry M. 2006. “Technology, Transport, Globalization and the Nutrition Transition Food Policy.” Food policy 31(6):554–69. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin Barry M., Adair Linda S., and Wen Ng Shu. 2012. “Global Nutrition Transition and the Pandemic of Obesity in Developing Countries.” Nutrition reviews 70(1):3–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro and Zhou Min. 1993. “The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants.” The annals of the American academy of political and social science 530(1): 74–96. [Google Scholar]

- Quezada Amado D. and Lozada-Tequeanes Ana L.. 2015. “Time Trends and Sex Differences in Associations between Socioeconomic Status Indicators and Overweight-Obesity in Mexico (2006–2012).” BMC public health 15:1244–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reither Eric N. et al. 2015. “Clarifying Hierarchical Age-Period-Cohort Models : A Rejoinder to Bell and Jones.” Social Science & Medicine 145:125–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riosmena Fernando, Everett Bethany G., Rogers Richard G., and Dennis Jeff A.. 2015. “Negative acculturation and nothing more? Cumulative disadvantage and mortality during the immigrant adaptation process among Latinos in the United States.” International Migration Review 49(2): 443–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Juan A., Irizarry Laura M., and González-de Cossío Teresa. 2009. “Overview of the Nutritional Status of the Mexican Population in the Last Two Decades.” Salud Pública de México 51(S4):S645–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ro Annie, and Fleischer Nancy. 2014. “Changes in health selection of obesity among Mexican immigrants: A binational examination.” Social Science & Medicine 123: 114–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose D 2007. “Food Stamps, the Thrifty Food Plan, and meal preparation: the importance of the time dimension for US nutrition policy.” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 39: 226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roshania Reshma, Narayan KM, and Oza‐Frank Reena. 2008. “Age at arrival and risk of obesity among US immigrants.” Obesity 16(2): 2669–2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston Patrick. 2005. “Multiple Imputation of Missing Values: Update of Ice.” The Stata Journal 5(4):527–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut Rubén G. 2004. “Ages, Life Stages, and Generational Cohorts: Decomposing the Immigrant First and Second Generations in the United States1.” International Migration Review 38(3):1160–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Schwingshackl Lukas and Hoffmann Georg. 2015. “Diet Quality as Assessed by the Healthy Eating Index, the Alternate Healthy Eating Index, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Score, and Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies.” Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 115(5):780–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spallek Jacob, Zeeb Hajo, and Razum Oliver. 2011. “What Do We Have to Know from Migrants’ Past Exposures to Understand Their Health Status? A Life Course Approach.” Emerging Themes in Epidemiology 8(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens Gillian. 1999. “Age at immigration and second language proficiency among foreign-born adults.” Language in Society 28(4): 555–578. [Google Scholar]

- Subar Amy F. et al. 2015. “Addressing Current Criticism Regarding the Value of Self-Report Dietary Data.” The Journal of Nutrition 145(12):2639–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitler Julien, Martinson Melissa, and Reichman Nancy E.. 2015. “Does Life in the United States Take a Toll on Health? Duration of Residence and Birthweight among Six Decades of Immigrants.” International Migration Review

- Tovar Alison et al. 2013. “Immigrating to the US: What Brazilian, Latin American and Haitian Women Have to Say about Changes to Their Lifestyle That May Be Associated with Obesity.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 15(2):357–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans 8th ed.

- Hook Van, Jennifer Elizabeth Baker, and Altman Claire. 2009. “Does it begin at school or home? The institutional origins of overweight among young children of immigrants.” Pp. 205–224 in Immigration, Diversity, and Education, edited by Grigorenko Elena L. and Takanishi Ruby. New York: Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Hook Van, Jennifer Elizabeth Baker, Altman Claire E., and Frisco Michelle. 2012. “Canaries in a Coalmine: Immigration and Obesity among Mexican-origin Children. ” Social Science and Medicine 74(2): 125–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook Van, Jennifer Susana Quiros, and Frisco Michelle L.. 2015. “The Food Similarity Index : A New Measure of Dietary Acculturation Based on Dietary Recall Data.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 17(2):441–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes Edna A., Miranda Patricia Y., and Abdulrahim Sawsan. 2012. “Social Science & Medicine More than Culture : Structural Racism, Intersectionality Theory, and Immigrant Health.” Social Science & Medicine 75(12):2099–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winship Christopher and Harding David J.. 2008. “A Mechanism-Based Approach to the Identification of Age–period–cohort Models.” Sociological Methods & Research 36(3):362–401. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Yang and Land Kenneth C.. 2013. Age-Period-Cohort Analysis: New Models, Methods, and Empirical Applications Boca Raton: CRC Pres. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Min. 1997. “Growing Up American : The Challenge Confronting Immigrant Children and Children of Immigrants.” Annual Review of Sociology 23:63–95. [Google Scholar]