Abstract

Data from controlled clinical studies in patients with more advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) could inform clinical practice, but they are limited, since this sub-population is usually excluded from clinical trials. These exploratory post-hoc analyses of the open-label, long-term extension study RECAP (NCT00662038) aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of pirfenidone in patients with more advanced IPF. Patients were categorised according to the extent of lung function impairment at baseline: more advanced (percent predicted FVC <50% and/or DLco <35%) and less advanced (percent predicted FVC ≥50% and DLco ≥35%).

Overall, 596 patients with baseline FVC and/or DLco values available were included in the analyses; 187 patients had more advanced disease, and 409 patients had less advanced disease. Mean percent predicted FVC declined throughout 180 weeks of treatment in both more and less advanced disease subgroups. Both subgroups exhibited a similar pattern of adverse events; however, adverse events related to IPF progression were experienced by a higher proportion of patients with more advanced versus less advanced disease. Discontinuation rates due to any reason, adverse events related to IPF progression, or deaths were each higher in the more advanced versus the less advanced disease subgroup.

These analyses found that longer-term pirfenidone treatment resulted in a similar rate of lung function decline and safety profile in patients with more advanced versus less advanced IPF, and the data suggest that pirfenidone is efficacious, well tolerated, and a feasible treatment option in patients with more advanced IPF.

Keywords: Advanced disease, Antifibrotic, Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Lung function, Pirfenidone

Background

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a debilitating, progressive, fatal, fibrosing lung disease [1, 2]. Lung function, measured by percent predicted forced vital capacity (FVC) or carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLco), correlates with IPF disease outcomes, with more advanced impairments associated with decreased health-related quality of life [3] and survival [4]. Data from controlled clinical studies in patients with more advanced disease, which could inform clinical practice, are limited, since this subpopulation is usually excluded from clinical trials in IPF [5–8]. For example, in the phase III ASCEND (NCT01366209) and CAPACITY trials (NCT00287729 and NCT00287716) of pirfenidone in patients with IPF, patients with percent predicted FVC <50%, or DLco <30% (ASCEND) or <35% (CAPACITY), were excluded [6, 7]. Nevertheless, in daily practice, patients would be expected to remain on treatment if their percent predicted FVC or DLco decreased to <50% or <35%, respectively. These exploratory post-hoc analyses of RECAP aimed to assess efficacy and safety of pirfenidone in patients with more advanced IPF.

Methods

RECAP (PIPF-012; NCT00662038) was an open-label, long-term extension study in patients with IPF who had completed ASCEND or CAPACITY (there were no restrictions on disease severity for entry into RECAP), the methods and primary outcomes of which have been described previously [9]. Patients who previously received pirfenidone or placebo in CAPACITY and received pirfenidone 2403 mg/day during RECAP were included in the analyses. Patients from ASCEND were not included due to lack of FVC follow-up data [9].

Patients were categorised according to IPF severity, assessed by lung function impairment at baseline (entry into RECAP): more advanced (percent predicted FVC < 50% and/or DLco <35%) and less advanced (percent predicted FVC ≥50% and DLco ≥35%; FVC ≥50% or DLco ≥35%, if other lung function data were missing). Efficacy of pirfenidone by IPF severity was assessed by decline in percent predicted FVC and FVC volume over 180 weeks, as measured using change from baseline and linear slope analysis of annual rate of decline. Safety of pirfenidone by IPF severity was assessed by adverse event (AE) occurrence and reasons for discontinuation over 180 weeks.

Results

Overall, 628/779 (80.6%) patients completed CAPACITY without discontinuing treatment [6]; of these, 603 patients were enrolled in RECAP (n = 68 and n = 261 had received previous pirfenidone treatment at 1197 and 2403 mg/day, respectively; n = 274 had previously received placebo). In total, 596 patients with baseline FVC and/or DLco values available were included in these analyses; 187 patients had more advanced disease (n = 100, previous pirfenidone group; n = 87, previous placebo group) and 409 patients had less advanced disease (n = 225, previous pirfenidone group; n = 184, previous placebo group). Demographics in both the previous pirfenidone and placebo groups, respectively, were similar for more versus less advanced disease subgroups (mean age, 68.1 years and 68.0 years vs 68.3 years and 68.4 years; male, 72.0 and 78.2% vs 70.7 and 70.7%; white, 98.0 and 100.0% vs 97.8 and 96.7%; mean body mass index, 28.9 kg/m2 and 30.0 kg/m2 vs 29.2 kg/m2 and 29.8 kg/m2). Mean (standard deviation) percent predicted FVC at baseline for the previous pirfenidone and placebo groups, respectively, was 61.0% (14.3) and 58.4% (13.7) for more advanced disease, and 76.0% (15.2) and 76.1% (15.4) for less advanced disease. Corresponding values for percent predicted DLco were 29.5% (5.9) and 28.8% (6.2), respectively, for more advanced disease, and 46.7% (11.4) and 47.4% (8.8), respectively, for less advanced disease. Mean duration of pirfenidone exposure over 180 weeks of treatment was 102.3 weeks for the more advanced and 138.1 weeks for the less advanced disease subgroup.

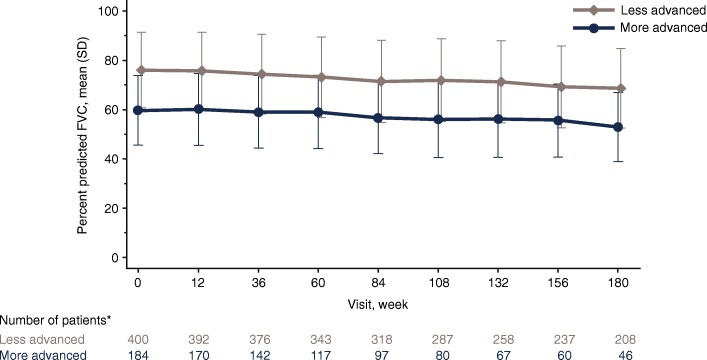

Mean percent predicted FVC declined throughout 180 weeks of treatment in both more and less advanced disease subgroups (Fig. 1). In the more advanced disease subgroup, mean (standard error) annual rate of percent predicted FVC decline was 3.8% (0.40) and 3.4% (0.43) following previous pirfenidone and placebo treatment, respectively. Corresponding values in the less advanced disease subgroup were 3.9% (0.24) and 3.9% (0.27). Mean (standard error) annual decline in FVC volume in the more advanced disease subgroup was 146.1 mL (15.5) and 137.6 mL (16.7) following previous pirfenidone and placebo treatment, respectively. Corresponding values in the less advanced disease subgroup were 151.7 mL (10.0) and 156.0 mL (11.2).

Fig. 1.

Mean percent predicted FVC over time by IPF severity at baseline in RECAP. *Patients with missing percent predicted FVC and DLco values were excluded. FVC Forced vital capacity, DLco Carbon monoxide diffusing capacity, IPF Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, SD Standard deviation

Overall, 187 (100.0%) patients with more advanced and 408 (99.8%) patients with less advanced disease experienced ≥1 AE during 180 weeks of treatment (Table 1). AE incidence per patient-year exposure was 8.29 and 7.40 in the more and less advanced disease subgroups, respectively. Both subgroups exhibited a similar pattern of AEs; however, AEs related to IPF progression were experienced by a higher proportion of patients with more advanced versus less advanced disease (56.1% vs 39.6% for dyspnoea; 58.3% vs 27.4% for worsening of IPF; Table 1). Nausea and diarrhoea were each experienced by a higher proportion of patients with less dvanced than more advanced disease (37.7% vs 29.9% for nausea; 30.1% vs 23.5% for diarrhoea; Table 1); however, there were similar AE incidences per patient-year exposure in the more and less advanced disease subgroups (0.19 vs 0.18 for nausea; 0.19 vs 0.16 for diarrhoea). Discontinuation rates due to any reason, AEs related to IPF progression and deaths were each higher in the more advanced than less advanced disease subgroup (Table 1). Throughout the treatment period there was little difference in mean body weight of patients with more versus less advanced disease (baseline: 85.8 kg vs 85.5 kg; Week 180: 81.2 kg vs 81.8 kg).

Table 1.

Summary of common adverse eventsa and reasons for treatment discontinuation by IPF severity at RECAP baseline

| More advanced disease (n = 187) | Less advanced disease (n = 409) | Total (n = 596) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients with ≥1 adverse event in the first 180 weeks of treatment, n (%) | |||

| Total | 187 (100.0) | 408 (99.8) | 595 (99.8) |

| Cough | 96 (51.3) | 209 (51.1) | 305 (51.2) |

| Dyspnoea | 105 (56.1) | 162 (39.6) | 267 (44.8) |

| Fatigue | 68 (36.4) | 164 (40.1) | 232 (38.9) |

| Worsening of IPFb | 109 (58.3) | 112 (27.4) | 221 (37.1) |

| Nausea | 56 (29.9) | 154 (37.7) | 210 (35.2) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 61 (32.6) | 137 (33.5) | 198 (33.2) |

| Bronchitis | 51 (27.3) | 130 (31.8) | 181 (30.4) |

| Diarrhoea | 44 (23.5) | 123 (30.1) | 167 (28.0) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 40 (21.4) | 117 (28.6) | 157 (26.3) |

| Dizziness | 39 (20.9) | 105 (25.7) | 144 (24.2) |

| Headache | 37 (19.8) | 98 (24.0) | 135 (22.7) |

| Back pain | 36 (19.3) | 91 (22.2) | 127 (21.3) |

| Dyspepsia | 26 (13.9) | 96 (23.5) | 122 (20.5) |

| Reasons for discontinuation, n (%) | |||

| All reasons | 134 (71.7) | 177 (43.3) | 311 (52.2) |

| Adverse event | 81 (43.3) | 110 (26.9) | 191 (32.0) |

| Related to IPFc | 26 (13.9) | 21 (5.1) | 47 (7.9) |

| Not related to IPF | 55 (29.4) | 89 (21.8) | 144 (24.2) |

| Withdrawal by patient | 16 (8.6) | 35 (8.6) | 51 (8.6) |

| Death | 20 (10.7) | 13 (3.2) | 33 (5.5) |

| Lung transplantation | 12 (6.4) | 14 (3.4) | 26 (4.4) |

| Physician decision | 5 (2.7) | 3 (0.7) | 8 (1.3) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) |

IPF Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

aIn ≥20% of total patients

bWorsening of the underlying disease from baseline

cAdverse event designated with the preferred terms ‘IPF’, ‘disease progression’ or ‘interstitial lung disease’

Conclusion

These post-hoc analyses of RECAP found that annual rate of FVC decline was similar with longer-term pirfenidone treatment in patients with more and less advanced IPF (3.4–3.9%), and in line with that of the pirfenidone arm at 52 weeks in CAPACITY (~ 5%) [6]. Moreover, the safety profile of pirfenidone was generally similar between patients with more and less advanced disease (except for AEs related to IPF progression) and in line with that of pirfenidone in ASCEND and CAPACITY [6, 7]. However, the discontinuation rate, particularly due to AEs related to IPF, was higher for patients with more advanced than less advanced disease, which could reflect the higher severity of IPF in the more advanced versus less advanced disease subgroup.

Limitations of this study include the high discontinuation rate, the relatively small number of patients with more advanced disease, and that these were post-hoc exploratory analyses of an open-label extension study without a placebo arm. Additionally, the study population was biased towards patients who had completed CAPACITY, with patients in the previous pirfenidone subgroup having tolerated pirfenidone treatment for ≥72 weeks prior to being categorised by severity of IPF.

In summary, longer-term pirfenidone treatment resulted in a similar rate of lung function decline and safety profile in patients with more advanced versus less advanced IPF. These data suggest that pirfenidone is efficacious, well tolerated and a feasible treatment option in patients with more advanced IPF.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Rebekah Waters, PhD, of CMC AFFINITY, a division of McCann Health Medical Communications Ltd., Manchester, UK, funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd.

Funding

The original study and the post-hoc analysis were funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd./Genentech, Inc.

Availability of data and materials

Qualified researchers may request access to individual patient level data through the clinical study data request platform (www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com). Further details on Roche’s criteria for eligible studies are available here (https://clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Study-Sponsors/Study-Sponsors-Roche.aspx). For further details on Roche’s Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see here (https://www.roche.com/research_and_development/who_we_are_how_we_work/clinical_trials/our_commitment_to_data_sharing.htm).

Abbreviations

- AE

Adverse event

- DLco

Carbon monoxide diffusing capacity

- FVC

Forced vital capacity

- IPF

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- SD

Standard deviation

Authors’ contributions

All authors were involved in the interpretation of study results, contributed to the research letter from the outset, and read and approved the final draft. All authors vouch for the accuracy of the content included in the final letter.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, written informed consent was required from all patients participating in the study, and the institutional review board or ethics committee at each centre approved the study protocol.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

UC was a member of the CAPACITY trial steering committee and an advisor on IPF trials to Bayer, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd., FibroGen, GlaxoSmithKline, Global Blood Therapeutics, InterMune/Roche and UCB Celltech, and has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim and InterMune/Roche. CA was an advisor on IPF trials to F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd. and FibroGen, and has received personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, FibroGen, GlaxoSmithKline, InterMune/Roche, MSD and Sanofi. MKG was a member of the ASCEND study steering committee and an advisor for Bellerophon, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, InterMune/Roche and Patara, and has received research grants from Genentech and InterMune/Roche. LHL reports research grants, prior advisory board, and disease state education from Genentech, research grants and disease state education from Boehringer Ingelheim, research grants from Celgene and Novartis, and research grants and consulting fees from Galapagos and Bellerophon outside of the submitted work. WAW is on the speaker bureaus for F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd. and Boehringer Ingelheim; his institution has received research funding from both companies. UP was an employee of Clinipace-Accovion GmbH – a company contracted by F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd. to perform analyses of study data – at the time of this study. FG is an employee of F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd. K-UK is an employee and shareholder of F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd. PWN was a member of the ASCEND and CAPACITY study steering committees and a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, InterMune/Roche, Moerae Matrix and Takeda.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ulrich Costabel, Phone: +49 0201 433 4020, Email: ulrich.costabel@rlk.uk-essen.de.

Carlo Albera, Email: carlo.albera@yahoo.it.

Marilyn K. Glassberg, Email: mglassbe@med.miami.edu

Lisa H. Lancaster, Email: lisa.lancaster@vumc.org

Wim A. Wuyts, Email: wim.wuyts@uzleuven.be

Ute Petzinger, Email: ute.petzinger@gmx.net.

Frank Gilberg, Email: frank.gilberg@roche.com.

Klaus-Uwe Kirchgaessler, Email: klaus-uwe.kirchgaessler@roche.com.

Paul W. Noble, Email: paul.noble@cshs.org

References

- 1.Ley B, Collard HR, King TE., Jr Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:431–440. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-0894CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glaspole IN, Chapman SA, Cooper WA, Ellis SJ, Goh NS, Hopkins PM, et al. Health-related quality of life in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: data from the Australian IPF registry. Respirology. 2017;22:950–956. doi: 10.1111/resp.12989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nathan SD, Shlobin OA, Weir N, Ahmad S, Kaldjob JM, Battle E, et al. Long-term course and prognosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the new millennium. Chest. 2011;140:221–229. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wuyts WA, Kolb M, Stowasser S, Stansen W, Huggins JT, Raghu G. First data on efficacy and safety of nintedanib in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and forced vital capacity of ≤50% of predicted value. Lung. 2016;194:739–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, Costabel U, Glassberg MK, Kardatzke D, et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;377:1760–1769. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King TE, Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, Fagan EA, Glaspole I, Glassberg MK, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2083–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, Azuma A, Brown KK, Costabel U, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2071–2082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costabel U, Albera C, Lancaster LH, Lin CY, Hormel P, Hulter HN, et al. An open-label study of the long-term safety of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (RECAP). Respiration. 2017;94:408–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Qualified researchers may request access to individual patient level data through the clinical study data request platform (www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com). Further details on Roche’s criteria for eligible studies are available here (https://clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Study-Sponsors/Study-Sponsors-Roche.aspx). For further details on Roche’s Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see here (https://www.roche.com/research_and_development/who_we_are_how_we_work/clinical_trials/our_commitment_to_data_sharing.htm).