Mycobacterium tuberculosis, capable of latently infecting the host and causing aggressive tissue damage during active tuberculosis, is endowed with a complex regulatory capacity built of several sigma factors, protein kinases, and phosphatases. These proteins regulate expression of genes that allow the bacteria to adapt to various host-derived stresses, like nutrient starvation, acidic pH, and hypoxia. The cross talk between these systems is not well understood. SigF is one such regulator of gene expression that helps M. tuberculosis to adapt to stresses and imparts virulence. This work provides evidence for its inhibition by the multidomain regulator Rv1364c and activation by the kinase PknD. The coexistence of negative and positive regulators of SigF in pathogenic bacteria reveals an underlying requirement for tight control of virulence factor expression.

KEYWORDS: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, STPK, protein-protein interaction, serine/threonine protein kinase, sigma factor

ABSTRACT

Bacterial alternative sigma factors are mostly regulated by a partner-switching mechanism. Regulation of the virulence-associated alternative sigma factor SigF of Mycobacterium tuberculosis has been an area of intrigue, with SigF having more predicted regulators than other sigma factors in this organism. Rv1364c is one such predicted regulator, the mechanism of which is confounded by the presence of both anti-sigma factor and anti-sigma factor antagonist functions in a single polypeptide. Using protein binding and phosphorylation assays, we demonstrate that the anti-sigma factor domain of Rv1364c mediates autophosphorylation of its antagonist domain and binds efficiently to SigF. Furthermore, we identified a direct role for the osmosensor serine/threonine kinase PknD in regulating the SigF-Rv1364c interaction, adding to the current understanding about the intersection of these discrete signaling networks. Phosphorylation of SigF also showed functional implications in its DNA binding ability, which may help in activation of the regulon. In M. tuberculosis, osmotic stress-dependent induction of espA, a SigF target involved in maintaining cell wall integrity, is curtailed upon overexpression of Rv1364c, showing its role as an anti-SigF factor. Overexpression of Rv1364c led to induction of another target, pks6, involved in lipid metabolism. This induction was, however, curtailed in the presence of osmotic stress conditions, suggesting modulation of SigF target gene expression via Rv1364c. These data provide evidence that Rv1364c acts an independent SigF regulator that is sensitive to the osmosensory signal, mediating the cross talk of PknD with the SigF regulon.

IMPORTANCE Mycobacterium tuberculosis, capable of latently infecting the host and causing aggressive tissue damage during active tuberculosis, is endowed with a complex regulatory capacity built of several sigma factors, protein kinases, and phosphatases. These proteins regulate expression of genes that allow the bacteria to adapt to various host-derived stresses, like nutrient starvation, acidic pH, and hypoxia. The cross talk between these systems is not well understood. SigF is one such regulator of gene expression that helps M. tuberculosis to adapt to stresses and imparts virulence. This work provides evidence for its inhibition by the multidomain regulator Rv1364c and activation by the kinase PknD. The coexistence of negative and positive regulators of SigF in pathogenic bacteria reveals an underlying requirement for tight control of virulence factor expression.

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, responsible for an infection with the highest mortality due to any single bacterial species worldwide, is endowed with a genome enriched in signal transduction and gene regulatory modules (1, 2). Alternative sigma (σ) factors provide bacteria with the means to simultaneously regulate many genes in response to altered environmental or developmental signals encountered during the infection process (3, 4). Sigma factor F (SigF), the general stress response σ factor of M. tuberculosis, is implicated in persistence (5, 6). A sigF deletion mutant of M. tuberculosis is attenuated in the murine and guinea pig model of tuberculosis (7–9). Although the SigF regulon has been characterized in several studies (7, 10–14) and includes many genes involved in cell surface modification and virulence factor secretion (7, 14), there is a stark lack of uniformity in the phenotypic behavior of SigF mutant/overexpression strains in different studies, mostly attributed to the differences in the M. tuberculosis strains used (CDC1551 versus H37Rv) (8, 10, 12). Furthermore, very little is understood about how signals perceived in the host enable switching to the alternative σ factor.

The availability of most alternative σ factors is governed by a complex partner-switching system controlled by phosphorylation-dependent regulation, best exemplified by the Bacillus subtilis general stress response σ factor SigB (15). Under unstressed conditions, SigB is inactivated by the anti-σ factor RsbW, which physically binds to it and thus prevents the association of SigB with RNA polymerase. The anti-σ factor antagonist RsbV can bind and sequester RsbW in an unphosphorylated form, but this is prevented by the kinase activity of RsbW. This system is, in turn, regulated by two phosphatases, RsbP and RsbU, which on sensing different stress signals dephosphorylate RsbV. Another set of anti-σ factor and anti-σ factor antagonist homologs controls the activity of RsbU. Upon dephosphorylation by either RsbP or RsbU, RsbV binds RsbW, thus enabling stress-dependent transcription by a SigB-containing holoenzyme (15). However, the regulation of the B. subtilis SigB homolog in M. tuberculosis, SigF, is not very well understood. Cotranscribed with sigF, usfX encodes the cognate anti-σ factor for SigF (16). Apart from this, other putative anti-σ factor regulators (Rv0516c, Rv1364c, Rv1365c, Rv1904, Rv2638, Rv3687c) are present in the genome, and some of these have been characterized to be antagonists (16–23); however, ambiguity remains about their role vis-à-vis SigF. Although protein homology provides vital clues, it is difficult to extrapolate the function of these regulators. A study by Hatzios et al. revealed activation of the SigF regulon upon disruption of Rv0516c, questioning its role as an anti-σ factor antagonist (24). The existence of multiple regulators for SigF suggests that the inhibition of the alternate σ factor must also be crucial to its survival or pathogenesis. Rv1364c of M. tuberculosis is unique in its domain architecture, in that it mimics a tandem array of domains (sensor–phosphatase–kinase–anti-σ factor antagonist) in a single polypeptide, where the kinase domain is predicted to work as the anti-σ factor domain (17, 19, 20, 22, 23). Its function vis-à-vis an antagonist or agonist of SigF remains elusive, since both regulatory domains are present in a single protein.

In the present work, we demonstrate that Rv1364c functions primarily as a bona fide anti-SigF factor. We show that the kinase activity of Rv1364c is essential for its autophosphorylation of the anti-σ antagonist domain and that Rv1364c is capable of binding to SigF in the autophosphorylated form. This may have significance in restraining SigF activity under normal growth conditions. Through an independent mechanism, protein kinase D (PknD), a eukaryote-like serine/threonine protein kinase (STPK), induced the phosphorylation of both proteins and mobilized SigF release from Rv1364c. PknD overexpression has been shown in an earlier study to induce the SigF regulon indirectly (18); here we find evidence for a direct mechanistic link through phosphorylation-dependent dissociation with its anti-σ factor.

RESULTS

Autophosphorylation of recombinant Rv1364c and its effect on the interaction with SigF.

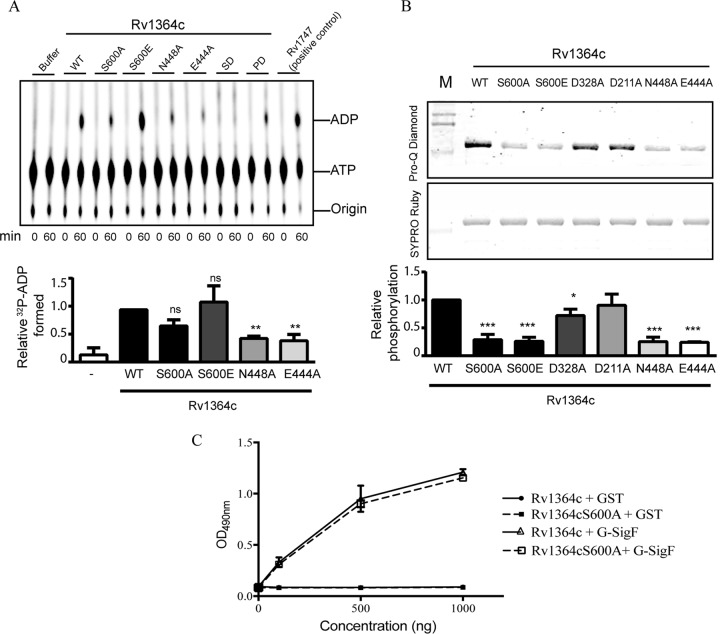

Previous studies on the characterization of Rv1364c reported the presence of an active phosphatase domain in Rv1364c, with D211 and D328 being identified as the active-site residues (19, 22). The kinase activity is questionable, as indicated by two opposing reports, with both being uncertain about the activity of the full-length protein (19, 20). The kinase domain of Rv1364c (RsbW) is reported to possess the characteristic Bergerat fold of the GHKL (gyrase, Hsp90, histidine kinase, MutL) ATPase/kinase superfamily (19, 20, 23). Our earlier attempts at characterizing this protein had demonstrated an inability of the protein to execute [γ-32P]ATP transfer to the C-terminal anti-σ factor antagonist domain belonging to the sulfate transporter and anti-sigma factor antagonist (STAS) family (19). We reasoned that this could be due to the dominant activity of the phosphatase in preventing retention of the transferred 32P. To further assess the activity of the anti-σ factor domain, we probed the ATPase activity of the full-length protein and found that it can indeed hydrolyze ATP. The kinase conserved active-site residues E444 and N448, based on sequence homology to B. subtilis proteins (19, 20, 23), were crucial for the ATPase activity (Fig. 1A). Surprisingly, the phosphomimetic mutant of the conserved phosphoacceptor residue (Rv1364cS600E) showed activity comparable to that of the full-length wild-type (WT) protein (Fig. 1A). So, we further probed if phosphorylation at the predicted S600 site was dependent on the kinase activity of Rv1364c. Using the phosphoprotein stain Pro-Q Diamond, we measured the phosphorylation status of the purified full-length protein Rv1364c. We observed that Rv1364c was efficiently phosphorylated under standard purification procedures (Fig. 1B). To explore the mechanism of autophosphorylation and to rule out phosphorylation due to any Escherichia coli kinase, we also probed the phosphorylation status of Rv1364c variants. Mutations in the kinase domain (N448A and E444A) and conserved phosphoracceptor site S600 in the substrate domain abolished the phosphorylation (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, mutations in conserved active-site residues of the phosphatase domain (D211A and D328A) had no effect on the phosphorylation status of the protein. Thus, our results indicate that Rv1364c is found in phosphorylated form when expressed in E. coli and provide a plausible reason why previous attempts at detecting the γ-32P of ATP being transferred at this site failed (19). The autophosphorylation at S600, however, does not confer any additional advantage to the interaction of Rv1364c with SigF (Fig. 1C). In view of the results of our previous study (19) and the present results, we therefore establish that full-length Rv1364c possesses both phosphatase and kinase activities and can efficiently bind to SigF independently of its autophosphorylation. Since PknD is known to influence the SigF regulon (18), we explored the cross talk of this STPK with the SigF-Rv1364c protein pair.

FIG 1.

Conserved ATPase and autophosphorylation activity in Rv1364c and effect on interaction with SigF. (A) (Top) Thin-layer chromatography- and autoradiography-based ATPase activity of purified Rv1364c, its indicated variants, or the positive control, Rv1747 possessing the ATPase domain, at 0 min and 60 min postincubation with [α-32P]ATP. Buffer alone acted as a negative control. SD, substrate domain of Rv1364c; PD, phosphatase domain of Rv1364c. (Bottom) Relative ADP formation, measured using densitometry and expressed as a percentage of the activity of the wild-type protein. The results from three independent experiments are presented here as the mean ± SEM. (B) (Top and middle) Pro-Q Diamond staining of recombinant Rv1364c and its variants. Pro-Q Diamond staining indicates the phosphorylation level, while SYPRO Ruby stains total protein. (Bottom) The ratio of the two densities normalized for each protein variant to the density of the wild-type protein. Data are means from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (mean ± SEM). Analysis of variance and Dunnett’s posttest were used to compare all groups to wild-type Rv1364c (***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; ns, not significant). Lanes M, molecular mass markers. (C) His6-tagged Rv1364c and its phosphoablative variant, Rv1364c S600A, were immobilized (500 ng/well) on the surface of the microtiter plate and challenged with increasing concentrations (0 to 1,000 ng) of GST-tagged fusion proteins, SigF, and GST alone (negative control) in solution. The error bars indicate the mean ± SD for triplicate readings.

Rv1364c and SigF are reversibly phosphorylated by PknD in vitro.

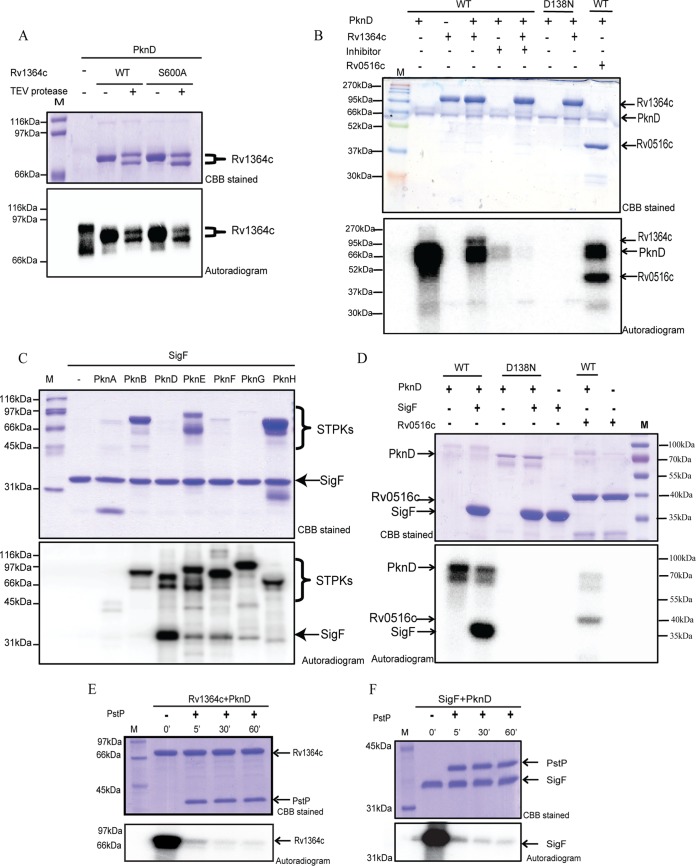

STPK-mediated phosphorylation fine-tunes a variety of cellular processes in Mycobacterium spp. to help these organisms rapidly adapt to host-derived stresses (25, 26). Studies have suggested the cross talk of STPK-mediated signaling and σ factor regulatory systems, indicating the importance of multimode regulation of transcription (18, 24, 27). PknD helps M. tuberculosis to adapt to osmotic stress by regulating the SigF regulon; however, the exact mechanism of how SigF is activated (released from its cognate anti-σ factors) is yet unknown (24). We performed an in vitro [γ-32P]ATP transfer assay with PknD and His6-tagged Rv1364c and found the efficient phosphorylation of Rv1364c by PknD (Fig. 2A). The kinase domains of PknD and Rv1364c are approximately the same size; therefore, to authenticate phosphotransfer to Rv1364c rather than the autophosphorylation of PknD in this assay, the reaction end products were treated with tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease, which cleaves the affinity tag from Rv1364c. The retention of radioactivity on the digested product validates the PknD-mediated phosphorylation of Rv1364c (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the S600A mutant retained the ability to be phosphorylated by PknD, suggesting the presence of additional phosphorylation sites on Rv1364c (Fig. 2A). Independently, Rv1364c cloned with a bigger maltose binding protein (MBP) tag was also subjected to the kinase assay in the presence of WT PknD or WT PknD in the presence of its specific inhibitor, SP600125, or the PknDD138N kinase-dead mutant, to confirm PknD-mediated phosphorylation of Rv1364c (Fig. 2B). The complete loss of phosphorylation of Rv1364c in the presence of the inhibitor and the PknD kinase-dead mutant confirmed the specificity of the reaction. The previously reported substrate of PknD, Rv0516c (18), was included as a positive control in these assays.

FIG 2.

PknD phosphorylates both Rv1364c and SigF. (A) In vitro kinase assay of Rv1364c with STPK (PknD). Digestion of the reaction products with TEV protease resolves the phosphorylation of WT Rv1364c, Rv1364c S600A, and PknD. Phosphorylation of Rv1364c S600A by PknD reveals a site distinct from the conserved autophosphorylation site. (B) In vitro kinase assay of Rv1364c with WT PknD, WT PknD in the presence of the inhibitor SP600125, and kinase-dead mutant PknDD138N. The loss of phosphorylation by the PknD inhibitor and kinase-dead PknD shows that PknD specifically phosphorylates Rv1364c. Rv0516c was included as a positive control. (C) In vitro kinase assay of M. tuberculosis STPKs (labeled on top) to check the phosphorylation of SigF in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. (D) An in vitro kinase assay of SigF with WT PknD and its kinase-dead mutant, PknDD138N, also shows the specificity of PknD-mediated phosphorylation of SigF. (E and F) (Bottom) Autoradiographs of PknD-phosphorylated Rv1364c (E) and SigF (F) after incubation with purified M. tuberculosis phosphatase PstP for the indicated times at 25°C show the reversibility of the PknD-mediated phosphorylation. (Top) Equal amount of protein in all lanes based on Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining. (Bottom) Images of autoradiographs of the same dried protein gel shown at the top visualized by use of a PhosphorImager FLA 2000/GE Typhoon Trio imager. Lanes M, molecular mass markers.

To test if extrinsic signals received by STPKs can also affect SigF directly, we performed in vitro [γ-32P]ATP transfer assays with purified full-length/kinase domains of PknA, PknB, PknD, PknE, PknF, PknG, and PknH. The kinase domain of PknD performed the most efficient phosphorylation of SigF (Fig. 2C), although other STPKs were also capable of phosphorylating it. The specificity of the PknD-mediated phosphorylation of SigF was also confirmed with the PknD kinase-dead mutant (Fig. 2D). The PknD-mediated phosphorylation of Rv1364c and SigF was reversed by PstP (Fig. 2E and F), the cognate phospho-Ser/Thr phosphatase, denoting the reversible regulation of their effector functions.

PknD phosphorylation attenuates the interaction of SigF with its anti-σ factor, Rv1364c.

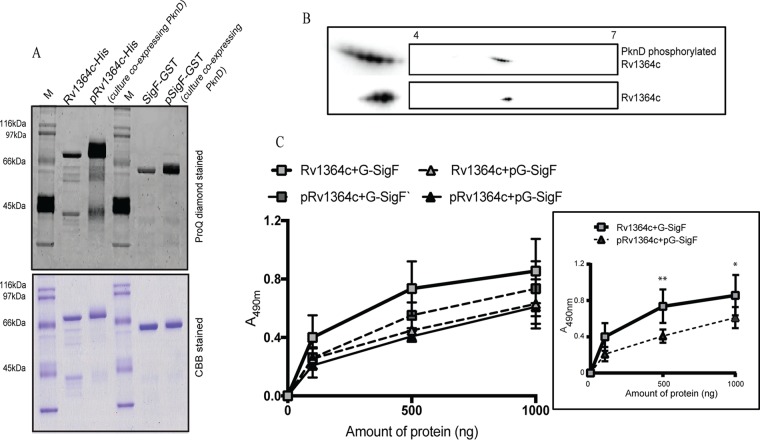

The PknD-mediated phosphorylation of Rv1364c and SigF was validated in vivo, using E. coli as a surrogate host (Fig. 3A). Rv1364c or SigF, coexpressed with PknD in vivo, were purified to assess phosphorylation. Pro-Q Diamond staining of purified Rv1364c (His tagged) and SigF (glutathione S-transferase [GST] tagged) showed phosphorylation (Fig. 3A). Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and immunoblot analysis of native Rv1364c and Rv1364c coexpressed with PknD in E. coli were also performed and indicated that multiple acidic phosphoisoforms of Rv1364c were generated by PknD, in contrast to the native Rv1364c, confirming the presence of additional phosphorylation sites (Fig. 3B). Through mass spectrometry, we identified the PknD-mediated phosphorylation of Rv1364c on multiple threonine and serine residues (Thr54, Thr81, Thr299, Thr390, Thr520, Thr568, and Ser506) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The results suggest that PknD directly phosphorylates the alternative σ factor SigF and its regulator, Rv1364c.

FIG 3.

PknD-mediated phosphorylation leads to decreased Rv1364c-SigF binding in vitro. Rv1364c (His6 tagged) and SigF (GST tagged) purified from cultures coexpressing MBP alone and MBP-PknD were evaluated for their phosphorylation by Pro-Q Diamond staining (A), two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (B), and interaction by ELISA (C). (A) (Top) Pro-Q Diamond-stained gel; (bottom) Coomassie brilliant blue staining of the same gel shown at the top. pG-SigF and pRv1364c refer to the phosphorylated forms of GST-tagged SigF (G-SigF) and Rv1364c, respectively, obtained from cultures coexpressing PknD. Lane M, molecular mass markers. (B) Two-dimensional gels of the Rv1364c protein purified from E. coli overexpressing pACYC-PknD-Rv1364c (top) or pACYC-Rv1364c (bottom). Approximately 500 pg of precipitated proteins was resolved on a 7-cm pH 4 to 7 linear gradient, followed by a second dimension on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and subjected to immunoblotting with anti-Rv1364c antibody. Rv1364c coexpressed with PknD in E. coli gets phosphorylated in vivo and shows additional acidic phosphoisoforms compared to the PknD-naive condition. (C) His6-tagged Rv1364c or pRv1364c was immobilized (500 ng/well) on the surface of the microtiter plate and challenged with increasing concentrations (0 to 1,000 ng) of GST-tagged SigF (G-SigF) or pG-SigF in solution. GST alone acted as a negative control. The values were normalized to those for the negative control, GST. (Inset) The same experiment with only the phosphorylated forms of the interacting proteins pRv1364c and pG-SigF. The error bars indicate the mean ± SD from three independent experiments, each with three technical replicates. Student's t test was applied for comparing means across groups (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

To examine the effect of PknD-mediated phosphorylation on the SigF-Rv1364c interaction in vitro, SigF and Rv1364c were coexpressed with and without PknD in the pACYC three-way protein expression system to obtain the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of these proteins (Fig. 3A). The protein-protein interaction was analyzed by a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Although the phosphorylation of only one of the interacting proteins (SigF or Rv1364) did not lead to a significant loss of the interaction (Fig. 3C), as shown in the inset in Fig. 3C, the interaction between SigF and Rv1364c was reduced significantly upon the in vivo phosphorylation of both proteins by PknD.

PknD-phosphorylated SigF mediates tighter complex formation with RNA polymerase.

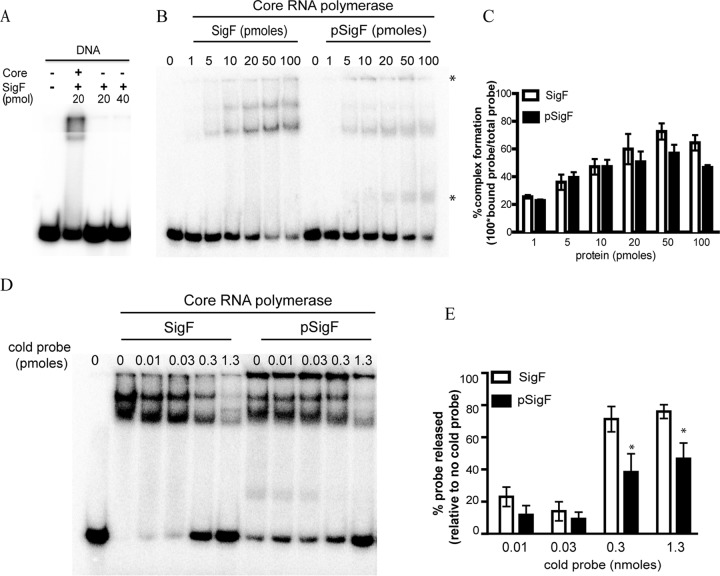

We questioned whether PknD-phosphorylated SigF retains its ability to recruit RNA polymerase to its cognate promoter. Purified SigF bound to the sigF promoter in an RNA core polymerase-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). Using the sigF promoter as the target sequence, we checked the ability of SigF and PknD-phosphorylated SigF (pSigF) to recruit E. coli core RNA polymerase to this DNA by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). We found that purified SigF and pSigF enabled DNA-protein complex formation with RNA polymerase in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). The phosphorylated protein reached saturation of binding at a lower protein concentration (Fig. 4B and C). Additional protein-DNA complexes of lower and higher mobility were found with PknD-phosphorylated SigF than with SigF (Fig. 4B, asterisks). Competition with a nonradioactive probe confirmed the specificity of the interaction in both cases. However, the release of only 50% of the radioactive probe from the pSigF-RNA polymerase-DNA complex compared to 80% of the probe from the unphosphorylated SigF counterpart at even 40 times the competing probe concentration suggested tighter complex formation by pSigF than by SigF (Fig. 4D and E). In view of the previous reports of studies in which PknD overexpression led to activation of the SigF regulon (18), our results show direct evidence of the effect of the PknD-mediated phosphorylation of SigF on its DNA binding ability and, thereby, its effect on the regulon. Thus, phosphorylation of SigF by PknD not only is responsible for the dissociation with its anti-σ factor but also causes tight binding of pSigF-RNA polymerase to DNA.

FIG 4.

Phosphorylated SigF binds tightly to the target gene promoter. (A) Binding of SigF to the sigF promoter in the presence of E. coli core RNA polymerase, measured using EMSA. (B and C) E. coli core RNA polymerase recruitment by SigF or pSigF to the sigF promoter, measured using EMSA. The percentage of DNA in complex was calculated using the following formula: 100 · (amount of bound probe/total amount of probe). (C) The bar graph represents the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. (D and E) Strength and specificity of DNA binding by SigF-RNA polymerase versus pSigF-RNA polymerase complexes measured by EMSA (D). The percentage of released DNA was calculated using the following formula: 100 · (1 − ΔFPc/ΔFP), where ΔFP = amount of free probe in the absence of SigF or pSigF − amount of free probe in the presence of SigF or pSigF; the subscript c indicates the presence of the competing cold probe. The graph (E) represents the mean ± SD from four independent experiments. The t test was used for comparing the means between SigF and pSigF for each DNA concentration (*, P < 0.05).

Rv1364c overexpression quenches SigF target gene espA induction under osmotic stress.

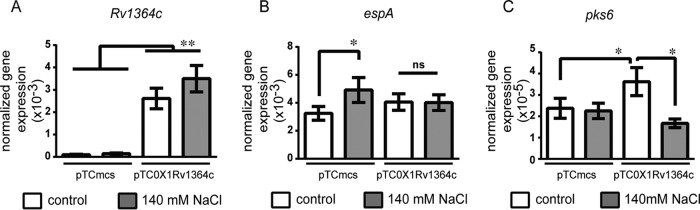

To understand how Rv1364c regulates SigF under stress, we looked at its role in the osmosensory signaling pathway. Hatzios et al. illustrated the PknD-mediated osmosensory activation of the SigF regulon gene espA, which enables M. tuberculosis to adapt to osmotic stress by cell wall remodeling and virulence factor production (24). We studied whether the induction of this gene is affected by the action of Rv1364c as either an anti-SigF or an anti-SigF antagonist. Approximately 25-fold overexpression of Rv1364c was achieved by the plasmid pTC0X1-Rv1364c in M. tuberculosis H37Rv (Fig. 5A). As shown earlier (24), osmotic stress led to a modest but statistically significant increase in the expression of espA (Fig. 5B). The ability to increase espA expression in response to osmotic stress was curtailed in cultures harboring the overexpression plasmid pTC0X1-Rv1364c (Fig. 5B). This suggested that Rv1364c functions as an anti-SigF factor. We studied another probable SigF target gene, the expression of which is not regulated by osmotic stress in wild-type cells, pks6 (7, 24). Expression of pks6 was indeed not induced by osmotic stress in the empty vector-containing strain (Fig. 5C). Cells overexpressing Rv1364c were found to express 50% higher levels of pks6 than cells of the control strain, probably due to an anti-SigF antagonist function in the basal state. Exposure to osmotic stress under this scenario led to an approximately 50% reduction in the expression of pks6, proposing activation of the anti-SigF property of Rv1364c by osmotic stress. Together, these data verify the role of osmotic stress-mediated control of SigF target genes via Rv1364c in M. tuberculosis.

FIG 5.

Rv1364c regulates the virulence factor espA under osmotic stress. The relative expression of Rv1364c (A), espA (B), and pks6 (C) in M. tuberculosis cultures harboring pTC0X1-Rv1364c versus pTC-mcs in the presence or absence of osmotic stress was measured by qRT-PCR. Cultures were exposed to 140 mM NaCl for 1 h to induce osmotic stress. Gene expression was normalized to 16S rRNA expression. Values are the mean ± SEM from six independent cultures. The t test was used for comparing means between the indicated groups (ns, not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

Distribution of Rv1364c-, SigF-, and PknD-like sequences in actinomycetes.

Earlier reports of divergence in SigF orthologs in M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis and, in general, in pathogenic versus nonpathogenic mycobacteria suggest that divergent regulatory circuits of SigF activation may play an important role in the virulence-associated features of this alternative σ factor (28, 29). The phylogenetic analysis of Rv1364c orthologs revealed that members from pathogenic mycobacteria form a distinct clade and appear to be phylogenetically closer to some nonmycobacterial actinobacterial members (Fig. S2A). We observed that the multidomain architecture is conserved in some actinobacterial species, such as Actinoplanes friuliensis, Nakamurella multipartita, Rhodococcus ruber, Modestobacter marinus, Amycolatopsis vancoresmycina, and Actinomadura madurae, apart from the pathogenic Mycobacterium. While A. madurae is an opportunistic human pathogen (30), R. ruber is a species closely related to a known opportunistic human pathogen, Rhodococcus equi. A. friuliensis and A. vancoresmycina are producers of friulimicin and vancoresmycin, respectively (31, 32). Since these environmental organisms are relatively less studied, we suggest that such a unique multidomain fusion event may endow these organisms with the means to adapt to environmental and host-derived stresses. The nonpathogenic mycobacterial clade conspicuously lacked the phosphatase-kinase-STAS occurrence. SigF orthologs formed three distinct clades, consisting of pathogenic Mycobacterium spp., nonpathogenic Mycobacterium spp., and nonmycobacterial actinomycetes (Fig. S2B). Interestingly, M. tuberculosis PknD sequence-specific features (viz., the kinase domain plus NHL repeats) are mostly conserved in the pathogenic Mycobacterium spp. only (Fig. S2C). This suggests the presence of a coregulatory mechanism for SigF-Rv1364c-PknD in the face of the specific stresses faced by these pathogenic members.

DISCUSSION

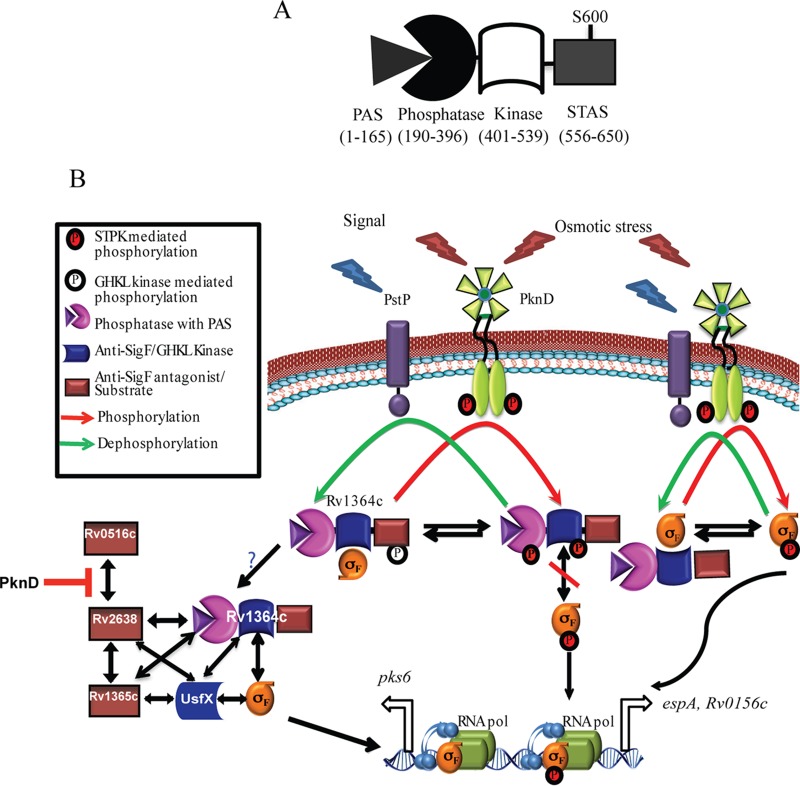

M. tuberculosis SigF draws parallels with B. subtilis SigB, by virtue of sequence homology. Compared to the paradigm of stressosome-dependent regulation of SigB in B. subtilis (33–35), a stressosome-independent control mechanism exists in M. tuberculosis for its homolog, SigF (Fig. 6). Since Bacillus possesses only stand-alone proteins possessing regulatory domains, M. tuberculosis probably evolved an alternate strategy to influence this interaction. While phosphorylation and dephosphorylation mediated by the GHKL family of kinases and PP2C phosphatases, respectively, are known to govern the opposing activities of regulatory proteins of SigB in B. subtilis (15), the regulation of M. tuberculosis SigF is not yet completely clear. Interestingly, bioinformatics analyses revealed a similar coevolution pattern for SigF and its regulator, Rv1364c, among members of the Mycobacterium genus (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The domain architecture of Rv1364c possesses a unique arrangement of sensor-PP2C phosphatase-GHKL kinase-STAS domains conserved only among the pathogenic mycobacterial members (19, 20, 23), suggesting additional ways to control virulence-associated SigF in the face of stresses (Fig. 6 and S2). While Rv1364c possesses both phosphatase and kinase activities, it primarily acts as a SigF anti-σ factor, with dominant autophosphorylation occurring at the conserved serine residue of the STAS domain (Fig. 1). The signal required for the switch to phosphatase activity is not yet known. The eukaryote-like STPK PknD has been implicated in activation of the SigF regulon under osmotic stress, albeit indirectly (18, 24). Here we describe a direct cross talk between PknD and SigF and its regulator, Rv1364c (Fig. 2 and 3). The PknD-mediated phosphorylation sites in Rv1364c identified in this work map to the different domains of the protein. These findings provide new directions toward understanding the regulation of SigF function.

FIG 6.

Schematic representation of the regulation of SigF in M. tuberculosis. (A) Domain architecture of Rv1364c indicating each of its domains. (B) Model of SigF regulation based on findings from previous studies (16, 18, 19, 24) and the results from the current study. Two anti-σ factors, the cognate UsfX and the multidomain regulator Rv1364c, bind to and negatively regulate SigF, the M. tuberculosis homolog of B. subtilis SigB. Osmotic stress-stimulated activation of PknD may lead to the phosphorylation of Rv1364c and SigF, thereby affecting their ability to interact with each other and releasing SigF. Both the native unphosphorylated and phosphorylated SigF can recruit RNA polymerase and may control different genes of its regulon in response to osmotic stress. Overexpression of Rv1364c may either increase the expression of some genes, such as pks6, or negatively influence the expression of others, such as espA, suggesting the influence of other SigF regulators that can directly interact with Rv1364c and influence the SigF regulon.

While STPKs have been described to target other mycobacterial σ factor regulators (27, 36), the role of phosphorylation of a σ factor has never been described in bacteria. In the plant Arabidopsis thaliana, SIG1 phosphorylation leads to inhibition of RNA polymerase recruitment to the photosystem I (PS-I) promoter, thereby helping in the switch to PS-II in response to redox stress (37). Phosphorylation-dependent relief from antagonists and the simultaneous activation of RNA polymerase recruitment would form a positive feed-forward loop for activation of the target σ factor regulon. Our work provides evidence for such a positive feed-forward activation mechanism of SigF by an extracellular sensor kinase, PknD, by not only destabilization of its interaction with its anti-σ factor, Rv1364c, but also simultaneous activation of its RNA polymerase recruitment function (Fig. 3 and 4). One of the consequences may be to initiate more frequent pulses of transcription initiation events, a phenomenon associated with amplification of the output in response to stress (38). Phosphorylated SigF may variably occupy certain targets of the SigF regulon, depending on the affinity of the promoter, leading to differential gene expression at various time points under stress conditions. It remains to be deciphered what signals modulate activation of the Ser/Thr phosphatase PstP that drives bacterial transcriptional regulation in the opposite direction.

A high density of SigF targets is involved in lipid metabolism and cell surface changes (11, 14). PknD activation by osmotic stress was shown to regulate espA via Rv0516c in the CDC1551 strain of M. tuberculosis (24). espA, an essential component of the ESX-1 secretion system, is involved in maintaining the integrity of the cell wall (24, 39). The lack of evidence for a direct interaction between Rv0516c and SigF left the pathway unlinked between phosphorylation of Rv0516c by PknD and induction of the SigF target, espA. Our data reveal the osmotic induction of espA in M. tuberculosis H37Rv and inhibition of this induction upon overexpression of Rv1364c, indicating its role as an anti-SigF factor under osmotic stress conditions (Fig. 5 and 6). Rv1364c-mediated repression of pks6, a gene involved in cell wall lipid synthesis (40), by osmotic stress also points toward its role as an anti-SigF factor under osmotic stress. Interestingly, the induction of pks6 upon overexpression of Rv1364c points toward an anti-SigF antagonist function which could be mediated through interaction with other SigF regulators. These results put forward another example of the intersection of signaling pathways mediated by eukaryote-like STPKs and alternative sigma factors, highlighting the tight regulation of the signal transduction mechanism in M. tuberculosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

E. coli DH5α (Novagen) was used as a host strain for cloning purposes, and E. coli BL21(DE3) (Stratagene) was used as a host strain for the expression of recombinant proteins. E. coli cells were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or LB agar (Difco) plates supplemented with 100 μg/ml of ampicillin and/or 25 μg/ml of kanamycin, when needed. M. tuberculosis H37Rv was grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco) supplemented with 0.2% glycerol, 0.05% Tween 80, and albumin-dextrose-catalase (Difco) at 37°C with shaking (150 rpm).

Constructs and gene manipulation.

pTC-mcs and pTC0X1L were kind gifts from Dirk Schnappinger, Weill Cornell Medical College (catalog numbers 20317 and 20315, respectively; Addgene) (41). The clones for GST- or His6-tagged STPKs and PstPcatalytic domain from previous studies were used (42–44). The plasmid coding for M. tuberculosis SigF, pLCD1, was kindly provided by W. R. Bishai (Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD). For the coexpression studies, the dual-expression vectors pETDuet-1 (Novagen) and pACYCDuet-1 (Novagen) were used (45, 46). The pETDuet-PknD construct from a previous study was used (45). SigF was subsequently cloned into the multiple-cloning site 1 (MCS1) region of the vector at HindIII-NotI sites. The PknD kinase domain amplicon was digested with NdeI and XhoI and cloned into the corresponding sites in MCS2 of pACYCDuet-1. Rv1364c was cloned into MCS1 of the pACYCDuet-1 and pACYC-PknD constructs at BamHI and HindIII sites. Rv1364c was also cloned into the pMAL vector to obtain MBP-Rv1364c. Rv0516c was cloned into the pGEX-5X-3 vector. All the DNA manipulations were carried out according to the standard protocols. The gene segment encoding Rv1364c cloned in pProExHTc and Rv1364cphosphatase domain, Rv1364ckinase domain, Rv1364csubstrate domain, Rv3287c (usfx) cloned in the pGEX-5X-3 vector from a previous study were used (19). Mutagenesis of the active-site residues of Rv1364c (D211A, D328A, E444A, N448A, S600A, S600E) and the PknD kinase active-site residue (D138N) was carried out using the HTc-Rv1364c construct and pGEX-PknD1–378 as templates, respectively, and a QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) as described previously (19). The sequences of all clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The primers and constructs used in this study are described in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer namea | Primer sequence (5ʹ → 3ʹ) |

|---|---|

| Rv1364c N448A F.P | TCCGAATTCGTCGAGGCCGCGGTCGAACACGGATAC |

| Rv1364c N448A R.P | GTATCCGTGTTCGACCGCGGCCTCGACGAATTCGGA |

| Rv1364c E444A F.P | CGTGCACGCGATCTCCGCATTCGTCGAGAACGCG |

| Rv1364c E444A R.P | CGCGTTCTCGACGAATGCGGAGATCGCGTGCACG |

| Rv1364c S600A F.P | GTCACCCACCTTGGTGCGGCCGGCGTCGGCGCC |

| Rv1364c S600A R.P | GGCGCCGACGCCGGCCGCACCAAGGTGGGTGAC |

| Rv1364c S600E F.P | GTCACCCACCTTGGTGAGGCCGGCGTCGGCGCC |

| Rv1364c S600E R.P | GGCGCCGACGCCGGCCTCACCAAGGTGGGTGAC |

| PknD D138N F.P | GGCGTAACGCACCGCAACGTAAAACCGG |

| PknD D138N R.P | CCGGTTTTACGTTGCGGTGCGTTACGCC |

| pETDuet_SigF_F.P | CGACGGGCGGCATCAAGCTTGTGACGGCGCGCGC |

| pETDuet_SigF_R.P | CTCGCCGAGATCAAGTAGGCGGCCGCCTACTCCAACTGATCCCG |

| pGEX_SigF_F.P | GCCCGACGGGCGGGATCCAGCAGGTGACGG |

| pGEX_SigF_R.P | CTCGCCGAGATCAAGTAAGGCGGCCGCCTACTCCAACTGATCCCG |

| pGEX_Rv0516c_F.P | CGACGGAGAACGAGGATCCTGATGACTACCACGATCCC |

| pGEX_Rv0516c_R.P | CACAACGACGACCCGCGGCCGCTTTAGGCTGACC |

| pMAL_1364_F.P | GGTCCGTAGGAGGGACGGATCCATGGCGGCCGAAATGG |

| pMAL_1364_R.P | CGTGCAGGCTCGTTGAAGCTTCTACTCCTGGGCGAAGATG |

| pACDuet_PknD F.P | GACCTAGTGAAGGGAATTCGCATATGAGCGATGCCGTTCCG |

| pACDuet_PknD R.P | GCCGACGACGGCCTCGAGCTTCCGTTTGTTGCCGGC |

| pACDuet_Rv1364c F.P | GTCCGTAGGAGGGATCCCCAAATGGCGGCCGAAATGG |

| pACDuet_Rv1364c R.P | CCGTGCAGGCTCGTTGAAGCTTCTACTCCTGGGCGAAG |

| Promoter_SigF F.P | GCGGCTGGAAATCCCGGCATCGCGGG |

| Promoter_SigF R.P | GGTCGGACCTGCTGGTAGTGGGGATCTAACGC |

| Rv1364c_RTF | TCGGTGCGGCCGAGGATGTACG |

| Rv1364c_RTR | TAGACCTCCCGAGCGGGCTGTC |

| 16S rRNA_RTF | TACGTTCCCGGGCCTTGT |

| 16S rRNA_RTR | AATCGCCGATCCCACCTT |

| espA_RTF | TCCGGGTGATGGCTGGTTAG |

| espA_RTR | GGTCGTGGATCAGGCTGATG |

| pks6_RTF | CGTAGTGCTGACTCGTTAAG |

| pks6_RTR | TCGGTCAGAAAGTCCCATAG |

F.P and F, forward primer; R.P and R, reverse primer.

TABLE 2.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid construct | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli DH5α | Used for cloning | Novagen, USA |

| Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) | Used for protein expression | Stratagene, USA |

| Plasmids | ||

| pProEx-HTc | E. coli expression vector with N-terminal His6 tag | Invitrogen |

| pProEx-HTc-Rv1364c (Rv1364c) | His6-Rv1364c1–653 (full length) | 19 |

| pProEx-HTc-Rv1364c D211A (Rv1364cD211A) | His6-Rv1364c1–653 carrying an Asp-to-Ala mutation in the phosphatase domain at residue 211 | 19 |

| pProEx-HTc-Rv1364c D328A (Rv1364cD328A) | His6-Rv1364c1–653 carrying an Asp-to-Ala mutation in the phosphatase domain at residue 328 | 19 |

| pProEx-HTc-Rv1364c E444A (Rv1364cE444A) | His6-Rv1364c1-653 carrying a Glu-to-Ala mutation in the kinase domain at residue 444 | This study |

| pProEx-HTc-Rv1364c N448A (Rv1364cN448A) | His6-Rv1364c1-653 carrying a Asn-to-Ala mutation in the kinase domain at residue 448 | This study |

| pProEx-HTc-Rv1364c S600A (Rv1364cS600A) | His6-Rv1364c1-653 carrying a Ser-to-Ala mutation in the substrate domain at residue 600 | This study |

| pProEx-HTc-Rv1364c S600E (Rv1364cS600E) | His6-Rv1364c1–653 carrying a Ser-to-Glu mutation in the substrate domain at residue 600 | This study |

| pProEx-HTc-PknAcat | His6-PknA1–337 (cytosolic domain) | 43 |

| pProEx-HTc-Pstpc | His6-Pstp1–300 (cytosolic domain) | 42 |

| pLCD1-SigF | His6-SigF | Kind gift from W. R. Bishai |

| pGEX-5X-3 | E. coli expression vector with an N-terminal glutathione S-transferase tag | GE Healthcare |

| pGEX-5X-3-Rv1365c (Rv1365c) | GST-Rv1365c1–128 (full length) cloned into BamHI/XhoI | This study |

| pGEX-5X-3-Rv1904 (Rv1904) | GST-Rv19041–143 (full length) cloned into BamHI/XhoI | This study |

| pGEX-5X-3-Rv2638 (Rv2638) | GST-Rv26381–148 (full length) | 19 |

| pGEX-5X-3-Rv3687c (Rv3687c) | GST-Rv3687c1–122 (full length) | 19 |

| pGEX-5X-3-Rv1364cKD (G-Rv1364cKD) | GST-Rv1364cc398–544 (kinase domain of Rv1364c) | 19 |

| pGEX-5X-3-Rv3287c (G-UsfX) | GST-Rv3287c1–145 (full length) cloned into BamHI/NotI | 19 |

| pGEX-5X-3-Rv3286c (G-SigF) | GST-Rv3286c1–261 (full length) | This study |

| pGEX-5X-3-PknBc (PknB) | GST-PknB1–331 (cytosolic domain) | 42 |

| pGEX-5X-3-PknDc (PknD) | GST-PknD1–378 (cytosolic domain) | 43 |

| pGEX-5X-3-PknDc D138N (PknDD138N) | GST-PknD1–378 carrying a mutation in the kinase domain at residue 138 | This study |

| pGEX-5X-3-PknE (PknE) | GST-PknE1–566 (full-length protein) | 43 |

| pGEX-5X-3-PknF (PknF) | GST-PknF1–476 (full-length protein) | 44 |

| pGEX-5X-3-PknG (PknG) | GST-PknG1–750 (full-length protein) | 44 |

| pGEX-5X-3-PknHc (PknH) | GST-PknH1–403 (cytosolic domain) | 43 |

| pGEX-5X-3-Rv0516c | GST- Rv0516c1–158 (full length) | This study |

| pMAL-c2x | E. coli expression vector with MBP tag | NEB |

| pMAL-Rv1364c | Rv1364c cloned into BamHI/HindIII | This study |

| pETDuet-1 | E. coli dual-expression vector with two multiple-cloning sites (MCS1 and MCS2), each preceded by an independent T7 promoter | Novagen |

| pETDuet-MBP | MBP tag cloned into Nde/EcoRV of MCS2 | 45 |

| pETDuet-MBP-PknDKD | MBP-PknD kinase domain cloned into Nde/EcoRV of MCS2 | 45 |

| pETDuet-MBP-SigF | SigF cloned into HindIII/NotI of MCS1 of pETDuet-MBP | This study |

| pETDuet-MBP-PknDKD-SigF | SigF cloned into HindIII/NotI of MCS1 of pETDuet-MBP-PknDKD | This study |

| pACYCDuet-1 | E. coli dual-expression vector with two multiple-cloning sites (MCS1 and MCS2), each preceded by an independent T7 promoter, Chlr | Novagen |

| pACDuet-PknDKD | PknD kinase domain cloned into Nde/XhoI of MCS2 | This study |

| pACDuet-Rv1364c | His6-Rv1364c cloned into BamHI/HindIII of MCS1 | This study |

| pACDuet-PknDKD-Rv1364c | PknD kinase domain cloned into Nde/XhoI of MCS2 and His6-Rv1364c cloned into BamHI/HindIII of MCS1 | This study |

| pCR-blunt | E. coli blunt cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pTC0X1L | Mycobacterial integrative expression vector containing the UV15tetO promoter, Kanr | Addgene (41) |

| pTC-mcs | Mycobacterial integrative vector, Kanr | Addgene (41) |

| pTC0X1-Rv1364c | Rv1364c was cloned at NdeI-PsiI site of the pTC0X1L plasmid | This study |

Purification of recombinant proteins.

All the recombinant constructs were expressed and purified with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid, glutathione-Sepharose, or amylose resin affinity columns (Qiagen/NEB) as His6-, GST-, or MBP-tagged fusion proteins from E. coli per the manufacturer’s instructions and as described previously (42, 45). The purified proteins were assessed by SDS-PAGE, and all the pure fractions were pooled and dialyzed with buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol). The protein concentrations were estimated by use of a Bio-Rad protein assay kit, and fractions were aliquoted and stored at −80°C until further use. To get phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of SigF, pETDuet-1 constructs coexpressing His6-SigF, MBP-PknD/His6-SigF, or MBP alone were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) Codon Plus cells (Stratagene). Cultures were induced with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) and further grown for 12 to 16 h at 18°C. Cells were harvested, and His6-tagged SigF and His6-tagged phospho-SigF were purified using the procedure mentioned above. The three-way coexpression of SigF and Rv1364c with PknD was obtained by cotransforming the pGEX-SigF plasmid with the pACYC-MBP-PknD-1364c and pACYC-MBPalone-1364c plasmids in E. coli to get phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of the proteins. The His6-tagged Rv1364c and GST-tagged SigF proteins were obtained from the overexpressed cultures by the purification procedure mentioned above.

ATPase activity assay.

The ATPase activity assay was performed essentially as described previously (47), with slight modifications. ATPase activity was determined in a reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1.0 μCi of [α-32P]ATP (20 μCi/mmol; Board of Radiation and Isotope Technology [BRIT], Hyderabad, India) and 3 μg purified protein of Rv1364c, Rv1364cD211A, Rv1364cD328A, Rv1364cN444A, Rv1364cN448A, Rv1364cS600A, Rv1364cS600E, or Rv1747 (positive control [48]). After 0 and 60 min of incubation at 25°C, the products were separated by thin-layer chromatography on polyethyleneimine cellulose sheets (Merck) using 0.75 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 3.75, as the solvent. The radioactive signal on the dried sheets was visualized with a PhosphorImager FLA 2000 imager (Fujifilm), and ATPase activity was assayed by measuring the relative intensity of the product, ADP, by the use of ImageQuant software.

Phosphorylation state detection by fluorescent staining.

For detection of the phosphorylation state of Rv1364c, Pro-Q Diamond phosphoprotein staining (Invitrogen) was performed per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, equal amounts of the wild-type and mutant proteins were electrophoresed by SDS-PAGE, and the gels were fixed twice in a solution of 50% (vol/vol) methanol and 10% (vol/vol) acetic acid and subsequently washed four times with Milli-Q water. The gels were stained with Pro-Q Diamond stain for 1.5 h. To remove the nonspecific background, the gels were destained three times with 20% acetonitrile, 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 4), followed by two additional washing steps. The gels were scanned using a Typhoon Trio+ scanner (GE Biosciences) (excitation source, 532-nm laser; long-pass emission filter, 560 nm). The same gels were then stained with SYPRO Ruby for total protein detection. To differentiate between phosphorylated and unphosphorylated proteins, the ratio of Pro-Q Diamond dye to SYPRO Ruby dye signal intensities for each band was determined by the use of imaging software. The molecular weight marker run in parallel with the proteins also served as a control.

In vitro kinase assay.

The in vitro kinase assays were performed by incubating 3 μg of Rv1364c or SigF and 0.5 to 3 μg of STPKs to obtain for each specific kinase the optimal autophosphorylation activity in a 25-μl reaction mixture containing 20 mM PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid); pH 7.2], 5 mM MnCl2, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 μCi [γ-32P]ATP (BRIT, Hyderabad, India) for 30 min at 25°C. The PknD inhibitor SP600125 was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and diluted in water, and the solution was added at a concentration of 20 μM to the reaction mixture (whenever required), as described previously (18). The reactions were terminated by adding Laemmli sample loading buffer, followed by boiling at 100°C for 5 min. The proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, stained with Coomassie blue, dried, and visualized by use of a PhosphorImager FLA 2000 (Fujifilm)/GE Typhoon Trio imager. For visualization of the phosphorylation signal on cleaved proteins, removal of recombinant tags was achieved by addition of proteases (thrombin [Novagen] for recombinant SigF and TEV for recombinant Rv1364c or its mutants) after the kinase reaction according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reactions were stopped by using SDS buffer and resolved on 8 to 10% SDS-PAGE gels. Likewise, for the dephosphorylation of phosphorylated SigF and Rv1364c, the reaction mixtures were incubated with PstPcat (1 μg) for an additional 0, 5, 30, and 60 min at 25°C and resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. The signals were visualized by autoradiography.

Analysis of protein isoforms by two-dimensional PAGE and immunoblotting.

To assess the phosphorylation status of native Rv1364c and PknD-phosphorylated Rv1364c, equal amounts of proteins were subjected to two-dimensional PAGE, followed by immunoblotting, as described earlier (27, 49). Briefly, each sample was rehydrated into 7-cm-long immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips with a pH range of 4 to 7 or 3.9 to 5.1, as appropriate (Bio-Rad). Isoelectric focusing was performed for 15,000 V-h in a Protean isoelectric focusing cell (Bio-Rad). After equilibration, strips were loaded and resolved in the second dimension through a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. The proteins were electrotransferred, and immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-Rv1364c polyclonal serum (customized antibody from Bangalore Genei India Pvt. Ltd.). The blots were developed using an Immobilon Western chemiluminescent horseradish peroxidase substrate kit (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

ELISA.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was done using the method described by Lu et al. (50) with some modifications. Briefly, the His6-tagged proteins were dissolved in coating buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3, pH 9.2) at a concentration of 5 μg/ml and adsorbed (100 μl/well) onto the surface of a 96-well ELISA plate (MaxiSorp; Nunc) overnight at 4°C. After rinsing the wells five times with wash buffer (phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, 0.05% Tween 20), the reactive sites were blocked with blocking buffer (2% bovine serum albumin in wash buffer) for 2 h at room temperature. After five washes, the adsorbed proteins were challenged with various concentrations of GST-tagged interacting proteins (100 μl/well) dissolved in binding buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 0.02% NP-40, 10% glycerol) for 1 h at room temperature. Following five washes, the wells were treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated GST antibody (catalog number ab3416; Abcam) at a 1:10,000-fold dilution for 1 h at room temperature. After five washes with wash buffer and an additional wash with phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, the chromogenic substrate o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (0.4 mg/ml in 0.1 M phosphate-citrate buffer, pH 5) and H2O2 were added to visualize the interaction. After addition of stop solution (2.5 M H2SO4), the absorbance was read at 490 nm.

EMSA.

DNA-σ factor binding was carried out by an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) as described previously (51). A DNA fragment derived from the upstream region of usfX containing the predicted SigF-specific promoter sequence (11, 16) was amplified from the M. tuberculosis H37Rv genome using specific primers (Table 1). After purification, the 118-bp PCR product (1 μg) was labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Roche Applied Science) and [γ-32P]ATP (BRIT, Hyderabad, India) per the manufacturer’s instructions. The radiolabeled PCR fragment was purified free of [γ-32P]ATP and polynucleotide kinase using a nucleotide removal kit (Qiagen). EMSAs were performed by incubation of 0.2 U of E. coli core polymerase enzyme (Epicentre Technologies) (11, 12) with various concentrations of purified SigF and pSigF in binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol) at 37°C for 10 min, followed by addition of 0.03 pmol labeled DNA probe. After incubation for an additional 30 min, 6× DNA loading buffer (Fermentas) was added, the reaction mixtures were electrophoresed at 4°C on 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) buffer for 2 h at 200 V, and the products were visualized by autoradiography (personal molecular imager system; Bio-Rad). To quantify the amount of DNA bound, ImageQuant data analysis software was used.

Gene expression analysis.

M. tuberculosis strains containing pTC-mcs, pTC0X1-Rv1364c, and pTC0X1-Rv1364c-S600A were grown in Sauton’s medium. Osmotic stress treatment was performed as described previously (24). Cultures were subcultured to an optical density (OD) of 0.05 in Sauton’s medium and grown to an OD of 0.6, and then NaCl (final concentration, 140 mM) or an equal volume of water was added, followed by incubation in a shaker incubator for 1 h at 37°C. The cultures were harvested by addition of equal volumes of 4 M guanidine isothiocyanate (GITC), followed by centrifugation. The culture pellet was resuspended in the TRIzol LS reagent, and RNA was extracted as reported previously (52). cDNA synthesis was performed using random hexamers, and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using the gene-specific primers listed in Table 1.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rakesh Sharma, Bhupesh Taneja, and Rajesh S. Gokhale for useful discussions during the course of this work and Ulf Gerth for helping with the mass spectrometry analysis.

This work was funded by CSIR Task Force projects BSC0403 and BSC0123, a DST Purse grant, and a JC Bose fellowship (SERB) to Y.S. Saba Naz was funded through a CSIR-Senior research fellowship.

We declare no conflict of interest with the contents of this article.

S. Gandotra and Y. Singh guided the study. R. Misra and S. Gandotra wrote the manuscript. R. Misra performed all experiments in E. coli and with recombinant proteins with contributions from G. Arora, R. Virmani, M. Gaur, S. Naz, A. Bothra, A. Maji, and A. Singhal; D. Menon and N. Jaisinghani performed the experiments with M. tuberculosis; C. Hentschker and D. Becher performed the mass spectrometry analysis; R. Misra and A. Bhaduri performed the phylogenetic analysis; V. Rao and V. K. Nandicoori provided strains and reagents; and V. Rao, P. Karwal, and V. K. Nandicoori provided inputs in discussion.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00725-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2014. Global tuberculosis report. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail MA, Rajandream M-A, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston JE, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodrigue S, Provvedi R, Jacques PE, Gaudreau L, Manganelli R. 2006. The sigma factors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Rev 30:926–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sachdeva P, Misra R, Tyagi AK, Singh Y. 2010. The sigma factors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: regulation of the regulators. FEBS J 277:605–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeMaio J, Zhang Y, Ko C, Young DB, Bishai WR. 1996. A stationary-phase stress-response sigma factor from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:2790–2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keren I, Minami S, Rubin E, Lewis K. 2011. Characterization and transcriptome analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persisters. mBio 2:e00100-11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00100-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geiman DE, Kaushal D, Ko C, Tyagi S, Manabe YC, Schroeder BG, Fleischmann RD, Morrison NE, Converse PJ, Chen P, Bishai WR. 2004. Attenuation of late-stage disease in mice infected by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutant lacking the SigF alternate sigma factor and identification of SigF-dependent genes by microarray analysis. Infect Immun 72:1733–1745. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1733-1745.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen P, Ruiz RE, Li Q, Silver RF, Bishai WR. 2000. Construction and characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutant lacking the alternate sigma factor gene, sigF. Infect Immun 68:5575–5580. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.10.5575-5580.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karls RK, Guarner J, McMurray DN, Birkness KA, Quinn FD. 2006. Examination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis sigma factor mutants using low-dose aerosol infection of guinea pigs suggests a role for SigC in pathogenesis. Microbiology 152:1591–1600. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28591-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartkoorn RC, Sala C, Uplekar S, Busso P, Rougemont J, Cole ST. 2012. Genome-wide definition of the SigF regulon in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol 194:2001–2009. doi: 10.1128/JB.06692-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodrigue S, Brodeur J, Jacques PE, Gervais AL, Brzezinski R, Gaudreau L. 2007. Identification of mycobacterial sigma factor binding sites by chromatin immunoprecipitation assays. J Bacteriol 189:1505–1513. doi: 10.1128/JB.01371-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams EP, Lee JH, Bishai WR, Colantuoni C, Karakousis PC. 2007. Mycobacterium tuberculosis SigF regulates genes encoding cell wall-associated proteins and directly regulates the transcriptional regulatory gene phoY1. J Bacteriol 189:4234–4242. doi: 10.1128/JB.00201-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galagan JE, Minch K, Peterson M, Lyubetskaya A, Azizi E, Sweet L, Gomes A, Rustad T, Dolganov G, Glotova I, Abeel T, Mahwinney C, Kennedy AD, Allard R, Brabant W, Krueger A, Jaini S, Honda B, Yu WH, Hickey MJ, Zucker J, Garay C, Weiner B, Sisk P, Stolte C, Winkler JK, Van de Peer Y, Iazzetti P, Camacho D, Dreyfuss J, Liu Y, Dorhoi A, Mollenkopf HJ, Drogaris P, Lamontagne J, Zhou Y, Piquenot J, Park ST, Raman S, Kaufmann SH, Mohney RP, Chelsky D, Moody DB, Sherman DR, Schoolnik GK. 2013. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis regulatory network and hypoxia. Nature 499:178–183. doi: 10.1038/nature12337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minch KJ, Rustad TR, Peterson EJ, Winkler J, Reiss DJ, Ma S, Hickey M, Brabant W, Morrison B, Turkarslan S, Mawhinney C, Galagan JE, Price ND, Baliga NS, Sherman DR. 2015. The DNA-binding network of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Commun 6:5829. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hecker M, Pané-Farré J, Völker U. 2007. SigB-dependent general stress response in Bacillus subtilis and related gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 61:215–236. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beaucher J, Rodrigue S, Jacques PE, Smith I, Brzezinski R, Gaudreau L. 2002. Novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis anti-sigma factor antagonists control sigmaF activity by distinct mechanisms. Mol Microbiol 45:1527–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parida BK, Douglas T, Nino C, Dhandayuthapani S. 2005. Interactions of anti-sigma factor antagonists of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the yeast two-hybrid system. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 85:347–355. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenstein AE, MacGurn JA, Baer CE, Falick AM, Cox JS, Alber T. 2007. M. tuberculosis Ser/Thr protein kinase D phosphorylates an anti-anti-sigma factor homolog. PLoS Pathog 3:e49. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sachdeva P, Narayan A, Misra R, Brahmachari V, Singh Y. 2008. Loss of kinase activity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis multidomain protein Rv1364c. FEBS J 275:6295–6308. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenstein AE, Hammel M, Cavazos A, Alber T. 2009. Interdomain communication in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis environmental phosphatase Rv1364c. J Biol Chem 284:29828–29835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.056168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malik SS, Luthra A, Ramachandran R. 2009. Interactions of the M. tuberculosis UsfX with the cognate sigma factor SigF and the anti-anti sigma factor RsfA. Biochim Biophys Acta 1794:541–553. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaiswal RK, Manjeera G, Gopal B. 2010. Role of a PAS sensor domain in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis transcription regulator Rv1364c. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 398:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King-Scott J, Konarev PV, Panjikar S, Jordanova R, Svergun DI, Tucker PA. 2011. Structural characterization of the multidomain regulatory protein Rv1364c from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Structure 19:56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatzios SK, Baer CE, Rustad TR, Siegrist MS, Pang JM, Ortega C, Alber T, Grundner C, Sherman DR, Bertozzi CR. 2013. Osmosensory signaling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis mediated by a eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E5069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321205110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakraborti PK, Matange N, Nandicoori VK, Singh Y, Tyagi JS, Visweswariah SS. 2011. Signalling mechanisms in mycobacteria. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 91:432–440. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chao J, Wong D, Zheng X, Poirier V, Bach H, Hmama Z, Av-Gay Y. 2010. Protein kinase and phosphatase signaling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis physiology and pathogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1804:620–627. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park ST, Kang CM, Husson RN. 2008. Regulation of the SigH stress response regulon by an essential protein kinase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:13105–13110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801143105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Humpel A, Gebhard S, Cook GM, Berney M. 2010. The SigF regulon in Mycobacterium smegmatis reveals roles in adaptation to stationary phase, heat, and oxidative stress. J Bacteriol 192:2491–2502. doi: 10.1128/JB.00035-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh AK, Singh BN. 2008. Conservation of sigma F in mycobacteria and its expression in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Curr Microbiol 56:574–580. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNeil MM, Brown JM, Scalise G, Piersimoni C. 1992. Nonmycetomic Actinomadura madurae infection in a patient with AIDS. J Clin Microbiol 30:1008–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vertesy L, Ehlers E, Kogler H, Kurz M, Meiwes J, Seibert G, Vogel M, Hammann P. 2000. Friulimicins: novel lipopeptide antibiotics with peptidoglycan synthesis inhibiting activity from Actinoplanes friuliensis sp. nov. II. Isolation and structural characterization. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 53:816–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wink JM, Kroppenstedt RM, Ganguli BN, Nadkarni SR, Schumann P, Seibert G, Stackebrandt E. 2003. Three new antibiotic producing species of the genus Amycolatopsis, Amycolatopsis balhimycina sp. nov., A. tolypomycina sp. nov., A. vancoresmycina sp. nov., and description of Amycolatopsis keratiniphila subsp. keratiniphila subsp. nov. and A. keratiniphila subsp. nogabecina subsp. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol 26:38–46. doi: 10.1078/072320203322337290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marles-Wright J, Grant T, Delumeau O, van Duinen G, Firbank SJ, Lewis PJ, Murray JW, Newman JA, Quin MB, Race PR, Rohou A, Tichelaar W, van Heel M, Lewis RJ. 2008. Molecular architecture of the “stressosome,” a signal integration and transduction hub. Science 322:92–96. doi: 10.1126/science.1159572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reeves A, Martinez L, Haldenwang W. 2010. Expression of, and in vivo stressosome formation by, single members of the RsbR protein family in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 156:990–998. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.036095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim TJ, Gaidenko TA, Price CW. 2004. A multicomponent protein complex mediates environmental stress signaling in Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol 341:135–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barik S, Sureka K, Mukherjee P, Basu J, Kundu M. 2010. RseA, the SigE specific anti-sigma factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is inactivated by phosphorylation-dependent ClpC1P2 proteolysis. Mol Microbiol 75:592–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimizu M, Kato H, Ogawa T, Kurachi A, Nakagawa Y, Kobayashi H. 2010. Sigma factor phosphorylation in the photosynthetic control of photosystem stoichiometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:10760–10764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911692107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Locke JC, Young JW, Fontes M, Hernandez Jimenez MJ, Elowitz MB. 2011. Stochastic pulse regulation in bacterial stress response. Science 334:366–369. doi: 10.1126/science.1208144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garces A, Atmakuri K, Chase MR, Woodworth JS, Krastins B, Rothchild AC, Ramsdell TL, Lopez MF, Behar SM, Sarracino DA, Fortune SM. 2010. EspA acts as a critical mediator of ESX1-dependent virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by affecting bacterial cell wall integrity. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000957. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waddell SJ, Chung GA, Gibson KJ, Everett MJ, Minnikin DE, Besra GS, Butcher PD. 2005. Inactivation of polyketide synthase and related genes results in the loss of complex lipids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Lett Appl Microbiol 40:201–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2005.01659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klotzsche M, Ehrt S, Schnappinger D. 2009. Improved tetracycline repressors for gene silencing in mycobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 37:1778–1788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta M, Sajid A, Arora G, Tandon V, Singh Y. 2009. Forkhead-associated domain-containing protein Rv0019c and polyketide-associated protein PapA5, from substrates of serine/threonine protein kinase PknB to interacting proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem 284:34723–34734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.058834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sajid A, Arora G, Gupta M, Singhal A, Chakraborty K, Nandicoori VK, Singh Y. 2011. Interaction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis elongation factor Tu with GTP is regulated by phosphorylation. J Bacteriol 193:5347–5358. doi: 10.1128/JB.05469-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koul A, Choidas A, Tyagi AK, Drlica K, Singh Y, Ullrich A. 2001. Serine/threonine protein kinases PknF and PknG of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: characterization and localization. Microbiology 147:2307–2314. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-8-2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan S, Nagarajan SN, Parikh A, Samantaray S, Singh A, Kumar D, Roy RP, Bhatt A, Nandicoori VK. 2010. Phosphorylation of enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase InhA impacts mycobacterial growth and survival. J Biol Chem 285:37860–37871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.143131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Molle V, Leiba J, Zanella-Cleon I, Becchi M, Kremer L. 2010. An improved method to unravel phosphoacceptors in Ser/Thr protein kinase-phosphorylated substrates. Proteomics 10:3910–3915. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chopra P, Singh A, Koul A, Ramachandran S, Drlica K, Tyagi AK, Singh Y. 2003. Cytotoxic activity of nucleoside diphosphate kinase secreted from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur J Biochem 270:625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molle V, Soulat D, Jault JM, Grangeasse C, Cozzone AJ, Prost JF. 2004. Two FHA domains on an ABC transporter, Rv1747, mediate its phosphorylation by PknF, a Ser/Thr protein kinase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 234:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singhal A, Arora G, Sajid A, Maji A, Bhat A, Virmani R, Upadhyay S, Nandicoori VK, Sengupta S, Singh Y. 2013. Regulation of homocysteine metabolism by Mycobacterium tuberculosis S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase. Sci Rep 3:2264. doi: 10.1038/srep02264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu YB, Ratnakar PV, Mohanty BK, Bastia D. 1996. Direct physical interaction between DnaG primase and DnaB helicase of Escherichia coli is necessary for optimal synthesis of primer RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:12902–12907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang X, Lopez de Saro FJ, Helmann JD. 1997. Sigma factor mutations affecting the sequence-selective interaction of RNA polymerase with −10 region single-stranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 25:2603–2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gandotra S, Schnappinger D, Monteleone M, Hillen W, Ehrt S. 2007. In vivo gene silencing identifies the Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteasome as essential for the bacteria to persist in mice. Nat Med 13:1515–1520. doi: 10.1038/nm1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.