Abstract

Background

Covalent RNA modifications, such as N-6-methyladenosine (m6A), have been associated with various biological processes, but their role in cancer remains largely unexplored. m6A dynamics depends on specific enzymes whose deregulation may also impact in tumorigenesis. Herein, we assessed the differential abundance of m6A, its writer VIRMA and its reader YTHDF3, in testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs), looking for clinicopathological correlates.

Methods

In silico analysis of TCGA data disclosed altered expression of VIRMA (52%) and YTHDF3 (48%), prompting subsequent validation. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues from 122 TGCTs (2005–2016) were selected. RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and real-time qPCR (Taqman assays) for VIRMA and YTHDF3 were performed, as well as immunohistochemistry for VIRMA, YTHDF3 and m6A, for staining intensity assessment. Associations between categorical variables were assessed using Chi square and Fisher’s exact test. Distribution of continuous variables between groups was compared using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests. Biomarker performance was assessed through receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve construction and a cut-off was established by Youden’s index method. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

In our cohort, VIRMA and YTHDF3 mRNA expression levels differed among TGCT subtypes, with Seminomas (SEs) depicting higher levels than Non-Seminomatous tumors (NSTs) (p < 0.01 for both). A positive correlation was found between VIRMA and YTHDF3 expression levels. VIRMA discriminated SEs from NSTs with AUC = 0.85 (Sensitivity 77.3%, Specificity 81.1%, PPV 71.6%, NPV 85.3%, Accuracy 79.7%). Immunohistochemistry paralleled transcript findings, as patients with strong m6A immunostaining intensity depicted significantly higher VIRMA mRNA expression levels and stronger VIRMA immunoexpression intensity (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively).

Conclusion

Abundance of m6A and expression of VIRMA/YTHDF3 were different among TGCT subtypes, with higher levels in SEs, suggesting a contribution to SE phenotype maintenance. VIRMA and YTHDF3 might cooperate in m6A establishment in TGCTs, and their transcript levels accurately discriminate between SEs and NSTs, constituting novel candidate biomarkers for patient management.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12967-019-1837-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Epitranscriptomics, M6A, RNA, Testicular germ-cell tumors, VIRMA, YTHDF3

Background

Testicular cancer is the most common neoplasia among Caucasian men aged 15–44 years, with rising incidence due to widespread adoption of Western lifestyle, with 65,827 new cases expected worldwide in 2030 [1–3]. More than 95% of cases are derived from germ cells—testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs)—and the vast majority of these correspond to germ-cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS)-related tumors, according to the most recent World Health Organization (WHO) classification [4]. Furthermore, this category comprises two major subtypes—seminomas (SEs) and non-seminomatous tumors (NSTs)—and discrimination between them is of paramount clinical importance, entailing different prognosis and treatment algorithms [5, 6].

TGCTs are fascinating tumors, in part because they are truly developmental cancers [7]. Heterogeneity is the hallmark of GCNIS-related TGCTs, reflecting this complex tumor model, although they share a common cytogenetic background, i.e., isochromosome 12p [4, 8]. Thus, biological, morphological and clinical heterogeneity might also be related with dissimilar epigenetic backgrounds, which might be surveyed using novel biomarkers. Indeed, there is an increasing need for reliable and clinically validated TGCT biomarkers that might improve diagnosis, subtype discrimination, prognostication and patient monitoring, overcoming the limitations of classical serum markers currently employed in the clinical setting [9–14].

Recently, post-translational RNA modifications (so-called “Epitranscriptomics”) have emerged as fundamental modulators of many biological and disease processes [15, 16]. The most abundant of these modifications, N6-methyladenosine (m6A), is dynamically regulated by a variety of m6A-related proteins, organized as writers (which catalyze the methyl code), erasers (which delete the methyl code) and readers (m6A-binding proteins that target RNAs to their final destiny) [17–22]. The amount of m6A modification in messenger RNAs (mRNAs) has been implicated in diverse biological mechanisms and related diseases, such as immune response, metabolism, gametogenesis, embryogenesis, neurodevelopment and cancer [23–27].

Deregulation of m6A-related proteins has been shown to impact tumorigenesis and progression of several neoplasms, including breast, lung, liver and colorectal carcinomas, leukemias and glioblastoma, among others [24, 28–31]. Recently, we have thoroughly reviewed the available literature concerning these players in all tumor models [32]. There have been several studies, focusing both on the writer METTL3 [33] and other components of the methylation complex (such as METTL14 [34]), on erasers (such as ALKBH5 [35]) and readers (such as YTHDF1 [36]), seeking for clinicopathological correlates or further upstream or downstream (de)regulation mechanisms in cancer. While most studies seem to imply that overexpression of writers associates with poor prognostic features, many exceptions were depicted. However, no studies have focused on VIRMA and YTHDF3 as a writer/reader pair, which is surprising since our in silico analysis of publicly available databases pointed out these players as being preferably deregulated in urological cancers, including prostate, kidney and bladder cancer and also in TGCTs.

Moreover, and to the best of our knowledge, no studies on TGCTs have been reported, despite the importance of m6A modification in germ cell differentiation [37]. Given this link between m6A modification and embryogenesis and spermatogenesis, and since TGCTs are developmental-related, we hypothesize that alterations in m6A amount may also have a role in these tumors, with possible differences among more undifferentiated forms such as SE and more differentiated subtypes such as Teratoma (TE).

Methods

Given this rationale, we set out to assess the differential expression of m6A writer VIRMA and reader YTHDF3, in a cohort of TGCT patients, comparing with m6A abundance and establishing associations with clinicopathological data, looking for potential biological and clinical relevance of these findings.

Patients and tissue sample collection

All patients presenting with TGCTs at the Portuguese Oncology Institute of Porto between 2005 and 2016 were retrospectively queried using the Department of Pathology’s database. Thus, a cohort of 122 consecutive GCNIS-related TGCT patients with material available for analysis was selected for this study. All patients were operated and subsequently treated at our Institution by the same multidisciplinary team. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Portuguese Oncology Institute of Porto (Comissão de Ética para a Saúde—CES-IPO-1-2018).

Clinical files and pathology reports were reviewed. All histological slides (of both primary tumors and matching metastatic specimens) were reviewed and tumors were reclassified in light of the most recent 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs [4]. Staging was performed according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual. Patients presenting with metastases at diagnosis were further properly classified according to the International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group (IGCCCG) prognostic system [38, 39]. Follow-up was last updated on November 30, 2017.

All tumor samples corresponded to formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) orchiectomy specimens (prior to any systemic treatment) and matched metastatic specimens. Representative blocks (with > 80% tumor cellularity) were selected and individual tumor areas were thoroughly macro-dissected (eliminating areas of necrosis or exuberant inflammation), considering each tumor subtype/component in mixed germ cell tumors (MGCTs) as an independent sample. Ten micrometer sections were obtained for subsequent RNA extraction and 5 μm sections for immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using FFPE RNA/DNA Purification Plus Kit (Cat. 54300, Norgen), according to manufacturer instructions. RNA quantification and purity were assessed in NanoDrop™ Lite Spectophotometer (Cat. ND-LITE, Thermo Scientific™). cDNA synthesis (1000 ng) was accomplished by reverse transcription using RevertAid™ RT Reverse Transcription Kit (Cat. K1691, Thermo Scientific™). The reaction was performed in MyCycler™ Thermal Cycler System (Cat. 1709703, Bio-Rad) using the following conditions: 5 min at 25 °C, 60 min at 42 °C and 5 min at 70 °C. Samples were then stored at − 20 °C.

Real-time quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed in LightCycler® 480 multiwell plate system (Product no. 05015243001, Roche), according to the recommended protocol. TaqMan™ gene expression assays for VIRMA (assay ID Hs00936421, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Life Technologies®) and YTHDF3 (assay ID Hs00405590, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Life Technologies®) were used. For normalization of the assay (guaranteeing stable levels among all tumor samples) two normalizing TaqMan™ gene expression assays (beta-glucoronidase—GUSB—assay ID Hs99999908, Applied biosystems®; and 18S ribosomal RNA—18S rRNA, assay ID Hs99999901, Applied biosystems®) were used as internal controls. Mean concentration of both normalizing genes was calculated and relative expression of targets tested in each sample were obtained using the formula: . The ratio obtained was then multiplied by 1000 for easier tabulation. Serial dilutions of cDNA obtained from Human Reference Total RNA (Cat. 750500, Agilent Technologies®) were used to compute standard curves for each plate. All experiments were run in triplicate and two negative controls were used in each plate.

Immunohistochemistry

Antigenic recovery was performed with EDTA buffer in water bath (40 min) and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by 0.6% hydrogen peroxide. Nonspecific reactions were blocked with normal horse serum (dilution 1:50). Slides were incubated overnight with the following primary antibodies: anti-VIRMA rabbit polyclonal (Cat. PA5-56772, RRID AB_2643047, dilution 1:100; Thermo Fisher Scientific®); anti-YTHDF3 rabbit polyclonal (Product code ab103328, dilution 1:100, Abcam®); and anti-m6A rabbit monoclonal (Product code ab190886, dilution 1:750, Abcam®). Both post-primary antibody and polymer were incubated for 30 min at room temperature (Novolink™ Polymer Detection System—Novocastra, Product No. RE7150-K). Diaminobenzidine was used as chromogen and hematoxylin as counterstain. Urothelial carcinoma, breast carcinoma and normal brain tissue were used as positive controls for VIRMA, YTHDF3 and m6A, respectively. Negative control consisted on omission of primary antibodies. However, when the protocols were developed, negative external controls were used. Immunoexpression intensity was estimated separately for each TGCT component (including different components among MGCTs), considering staining as “weak”, “moderate” or “intense”; the percentage of stained cells was also assessed, but the staining was rather homogeneous among tumor samples, with all cells showing “positive” staining.

Statistical analysis

Data was tabulated using Microsoft Excel 2016 and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 and GraphPad Prism 6. Percentages were calculated based on the number of cases with available data. Associations between categorical variables were assessed using Chi square and Fisher’s exact test, and group proportions were compared with odds ratios (ORs). Distribution of continuous variables between groups was compared using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test and Kruskal–Wallis test, as appropriate. Bonferroni’s correction and Dunn’s test were employed for adjusting p-values in multiple comparisons, as appropriate. Correlation between continuous variables was assessed with Spearman’s (rs) non-parametric correlation test and interpretation of strength of results according to the system proposed by Evans [40]. In patients diagnosed with MGCT, the highest expression levels among all tumor components was considered for evaluating associations with clinicopathological features. Biomarker performance was assessed through receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve construction. ROC curves were constructed plotting sensitivity (true positive) against 1-specificity (false positive). A cut-off was established by Youden’s index method [41, 42]. In addition, area under the curve (AUC) and biomarker performance parameters, including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and accuracy, were ascertained. A logistic regression model was built to assemble the expression levels of both biomarkers as a panel. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In silico analysis

In silico analysis of the publicly available The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database for TGCTs concerning m6A-related proteins (writers, erasers and readers) was carried out. For this purpose, the online resource cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics was used [43] with the user-defined entry gene set “METTL3, METTL14, METTL4, METTL16, WTAP, VIRMA, RBM15, RBM15B, FTO, ALKBH5, YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, YTHDC1, YTHDC2, EIF3A, HNRNPC and HNRNPA2B1″. The database includes 156 tumors samples [65 SEs (42%) and 91 NSTs (58%)] from 150 patients, with a median age at diagnosis of 31 years. Most patients were stage I (79.4%) and considering patients with metastatic disease, most belonged to the good prognosis group (74.4%).

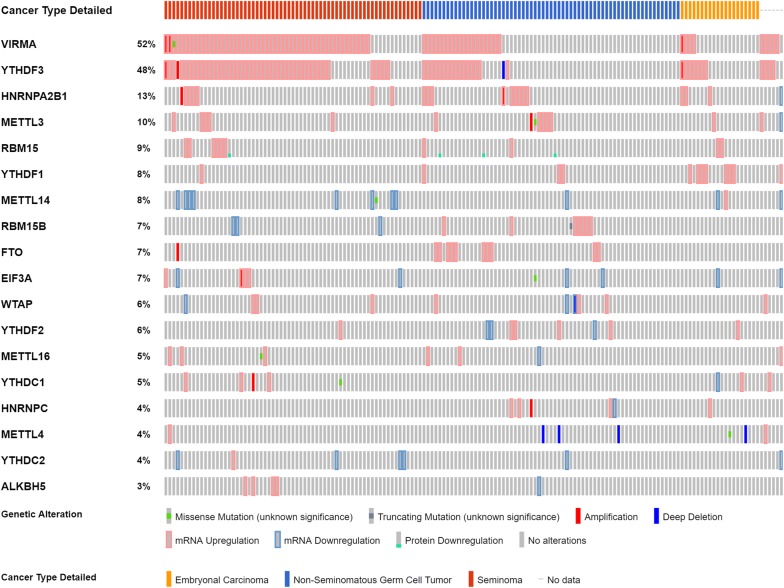

TCGA dataset analysis revealed that KIAA1429/VIRMA (a player belonging to the m6A writer complex) and YTHDF3 (m6A reader) were the two most commonly altered m6A-related genes in TGCTs (52% and 48% of the samples, respectively). Most alterations consisted of transcript upregulation, with no mutations found for YTHDF3 and only one depicted for VIRMA (Fig. 1). Importantly, the analysis of TCGA data depicted a strong correlation between mRNA expression levels of both these m6A regulators (rs = 0.77). Based on the results of this in silico analysis, VIRMA and YTHDF3 were selected for further validation in a patient tissue cohort.

Fig. 1.

In silico analysis: frequency of alterations in queried genes in TCGA database. Notice the frequency of alterations in VIRMA and YTHDF3 compared to other queried genes. Also, note the frequent co-existence of alterations in this pair of genes, and the high proportion of seminomas showing deregulation of such genes

In the same dataset, transcript levels of both genes were significantly higher in SE and in stage I disease (p < 0.001 for both), with VIRMA achieving an AUC of 0.83 in the discrimination between SEs and NSTs, using ROC curve analysis (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

IPO Porto’s cohort: characterization and validation

A total of 122 GCNIS-related TGCT patients were included in this study, comprising 56 (46%) with pure SE and 66 (54%) with NSTs, which included 58 MGCTs. Considering each tumor component as an independent sample (in a similar approach already used by us [44, 45]), we obtained a series of 75 SE (56 pure and 19 as MGCT component), 39 embryonal carcinomas (ECs) (5 pure and 34 as MGCT component), 35 postpubertal-type yolk sac tumors (YSTs) (all as MGCT components), 12 choriocarcinomas (CHs) (all as MGCT components) and 36 postpubertal-type TEs (3 pure and 33 as MGCT components). Most patients were stage I (78/122, 63.9%) and among patients with metastatic disease, most belonged to the good prognosis group (31/44, 70.5%). Detailed cohort description is depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the testicular germ cell tumor cohort

| Clinicopathological features | TGCT patients (n = 122) |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (IQR) | 28 (24–36) |

| Histological type | |

| Seminoma | 56/122 (45.9%) |

| Embryonal carcinoma | 5/122 (4.1%) |

| Postpubertal-type yolk sac tumor | 0/122 (0%) |

| Choriocarcinoma | 0/122 (0%) |

| Postpubertal-type teratoma | 3/122 (2.5%) |

| Mixed tumor | 58/122 (47.5%) |

| Pathological stage | |

| I | 78/122 (63.9%) |

| II | 23/122 (18.9%) |

| III | 21/122 (17.2%) |

| IGCCCG grouping (for metastatic disease) | |

| Good | 31/44 (70.5%) |

| Intermediate | 6/44 (13.6%) |

| Poor | 7/44 (15.9%) |

| Clinicopathological features | Primary TGCT tumor samples (n = 197) |

|---|---|

| Histological type | |

| Seminoma | 75/197 (38.0%) |

| Embryonal Carcinoma | 39/197 (19.8%) |

| Postpubertal-type yolk sac tumor | 35/197 (17.8%) |

| Choriocarcinoma | 12/197 (6.1%) |

| Postpubertal-type teratoma | 36/197 (18.3%) |

| Clinicopathological features | Metastatic TGCT tumor samples (n = 19) |

|---|---|

| Histological type | |

| Seminoma | 1/19 (5.3%) |

| Embryonal carcinoma | 5/19 (26.3%) |

| Postpubertal-type yolk sac tumor | 3/19 (15.8%) |

| Choriocarcinoma | 1/19 (5.3%) |

| Postpubertal-type teratoma | 9/19 (47.3%) |

| Type of metastasis | |

| Lymph node | 12/19 (63.2%) |

| Visceral | 7/19 (36.8%) |

IGCCCG International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group, IQR interquartile range, TGCT testicular germ cell tumors

VIRMA and YTHDF3 mRNA expression levels in IPO Porto’s cohort

SE vs. NST tissue samples

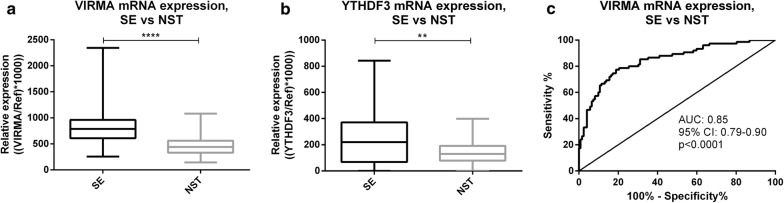

VIRMA and YTHDF3 mRNA levels were significantly higher in SEs compared to NSTs (p < 0.001 and p = 0.0014, respectively) (Fig. 2a, b). Moreover, VIRMA transcript levels discriminated SEs from NSTs with 77.3% sensitivity, 81.1% specificity, 72.0% PPV, 86.1% NPV and 80.2% accuracy, corresponding to an AUC of 0.85 in ROC curve analysis (Fig. 2c). Nonetheless, YTHDF3 discriminative power was rather modest: 53.3% sensitivity, 81.1% specificity, 63.5% PPV, 73.9% NPV, 70.6% accuracy and an AUC of 0.64.

Fig. 2.

Transcript levels of VIRMA and YTHDF3 among seminoma and non-seminomatous tumor samples. a VIRMA mRNA expression in seminomas vs. non-seminomatous tumors; b YTHDF3 mRNA expression in seminomas vs. Non-seminomatous tumors; c ROC curve for discrimination among seminomas and non-seminomatous tumors based on VIRMA mRNA expression levels. SE Seminoma, NST non-seminomatous tumor, AUC area under the curve, Ref reference genes GUSB and 18S, CI confidence interval

Combining expression levels of both genes in a logistic regression model, YTHDF3 did not significantly increment the performance of VIRMA transcript. Indeed, a similar AUC value was depicted (AUC = 0.84). Nevertheless, considering the VIRMA/YTHDF3 panel “positive” if at least one of the genes was expressed above the empirical cutoff value, high sensitivity (82.7) and NPV (87.1%) were achieved (Table 2).

Table 2.

Performance parameters for discriminating among Seminomas and Non-Seminomatous Tumors

| Gene/panel | AUC (95% CI) |

Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIRMA | 0.85 (0.79–0.90) | 77.3 | 81.1 | 72.0 | 86.1 | 80.2 |

| YTHDF3 | 0.64 (0.55–0.72) | 53.3 | 81.1 | 63.5 | 73.9 | 70.6 |

| VIRMA/YTHDF3 (≥ 1 above cutoff) |

– | 82.7 | 72.1 | 64.6 | 87.1 | 76.1 |

| VIRMA/YTHDF3 (both above cutoff) |

– | 48.0 | 90.2 | 75.0 | 73.8 | 74.1 |

AUC area under the curve, CI confidence interval, PPV positive predictive value; NPV negative predictive value

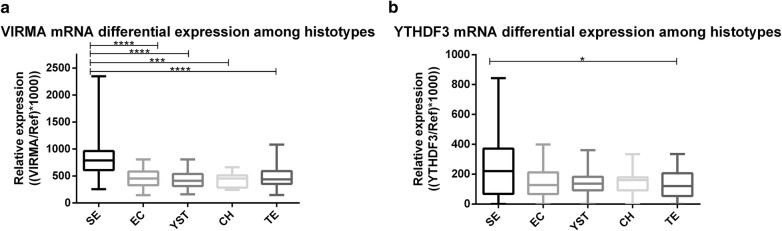

Differential expression of VIRMA and YTHDF3 among TGCT subtypes

In a preliminary analysis, no significant differences for VIRMA and YTHDF3 transcript levels between pure (SE, EC and TE) and respective mixed tumor forms were found (Additional file 2: Figure S2). Thus, similar histological components derived from pure or MGCT were grouped together for subsequent analyses.

VIRMA transcript levels were significantly higher in SEs compared to all other NST components (adjusted p value: 0.0005 for SE vs. CH and < 0.0001 for SE vs. EC, YST or TE) (Fig. 3a). No significant differences were depicted among NST subtypes. As for YTHDF3, transcript levels were significantly higher in SEs compared to TEs, only (adjusted p-value 0.042) (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

VIRMA (a) and YTHDF3 (b) mRNA expression levels among different tumor subtypes. SE Seminoma, EC embryonal carcinoma, YST pospubertal-type Yolk sac tumor, CH choriocarcinoma, TE postpubertal-type Teratoma, Ref reference genes GUSB and 18S

Considering all tumor samples, VIRMA and YTHDF3 mRNA expression levels were positively correlated (rs = 0.44, p < 0.001) (Additional file 3: Figure S3).

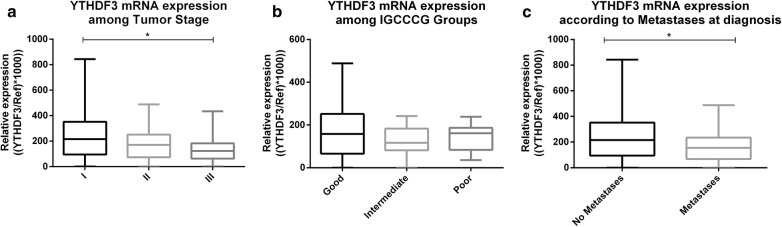

Association with clinicopathological parameters

Significantly higher YTHDF3 mRNA expression levels were observed in stage I compared to stage III TGCTs (adjusted p-value 0.0472), with a trend for decreasing expression in each disease stage. Also, patients with no metastases at diagnosis showed higher YTHDF3 transcript levels compared to patients with metastases (p = 0.0212) (Fig. 4). Conversely, no significant associations between VIRMA expression levels and stage, IGCCCG grouping or metastatic disease status at diagnosis were depicted (Additional file 4: Figure S4).

Fig. 4.

YTHDF3 transcript levels among Stage (a), IGCCCG Prognostic Group (b) and presence of metastases at diagnosis (c). IGCCCG international Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group; Ref reference genes GUSB and 18S

Evaluation of VIRMA, YTHDF3 and m6A immunoexpression

m6A, VIRMA and YTHDF3 immunoexpression in primary tumors

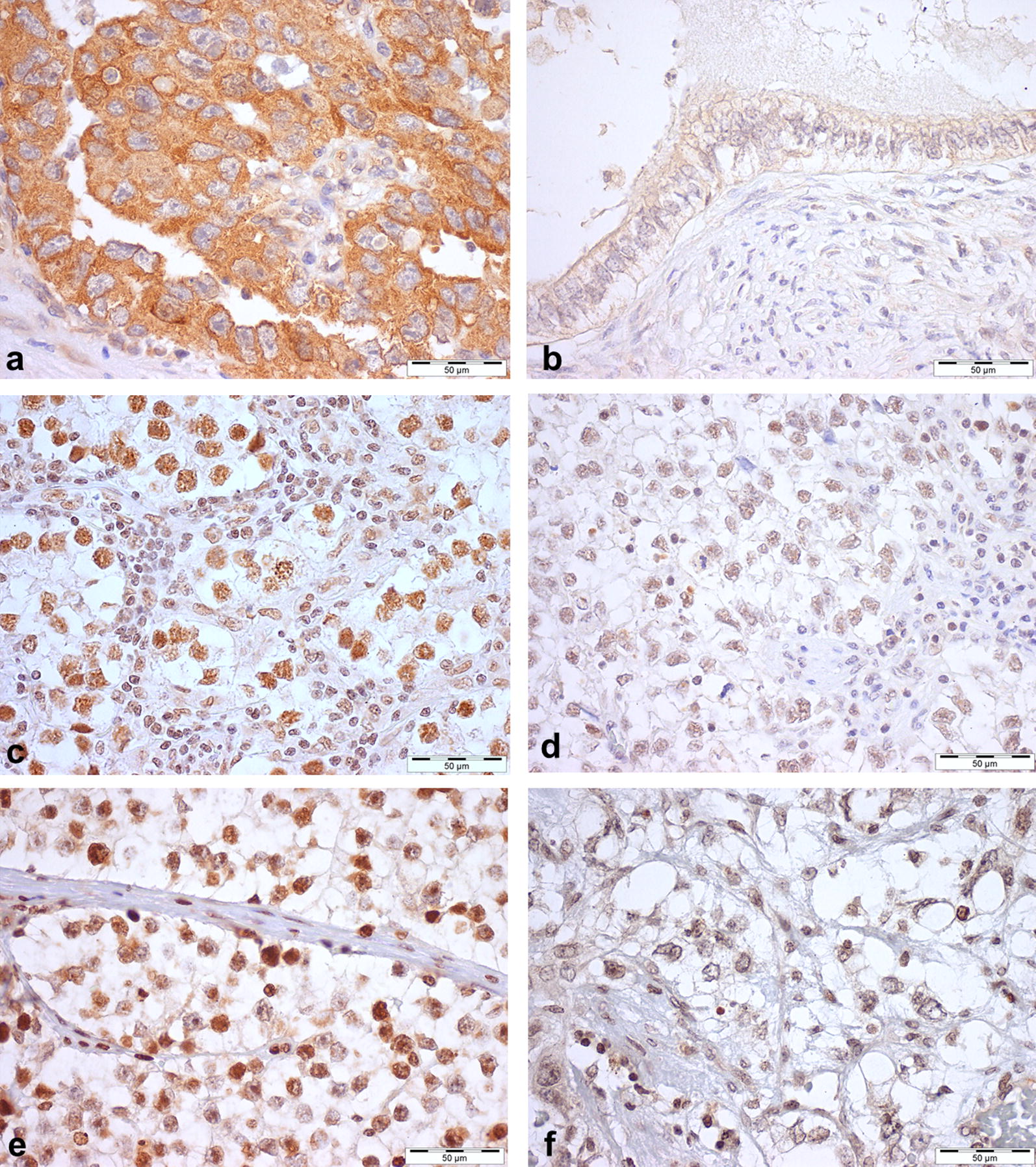

The cellular distribution of the m6A modification, VIRMA and YTHDF3 differed among tested tumor tissues (detailed immunoexpression parameters are depicted in Additional file 5: Table S1). m6A immunostaining was predominantly nuclear [194/196 (99.0%) cases], with cytoplasmic staining in only 29.1% of tumor samples. Concerning m6A regulators, VIRMA staining was predominantly nuclear in all cases, whereas YTHDF3 exhibited mostly cytoplasmic staining. The nuclear staining of m6A and VIRMA and the cytoplasmic staining of YTHDF3 displayed a granular characteristic. Illustrative examples of immunostaining are depicted in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Immunostaining for YTHDF3 (a, b), VIRMA (c, d); and m6A (e, f) in testicular germ cell tumors. a Strong YTHDF3 cytoplasmic immunoexpression in embryonal carcinoma; b Weak/moderate YTHDF3 cytoplasmic immunoexpression in postpubertal-type teratoma; c strong VIRMA nuclear immunoexpression in seminoma; d Weak/moderate VIRMA nuclear immunoexpression in Seminoma; e Strong m6A nuclear immunostaining in seminoma; f Weak/moderate m6A nuclear immunostaining in postpubertal-type yolk sac tumor. Note the granularity of staining, particularly in c, d and e

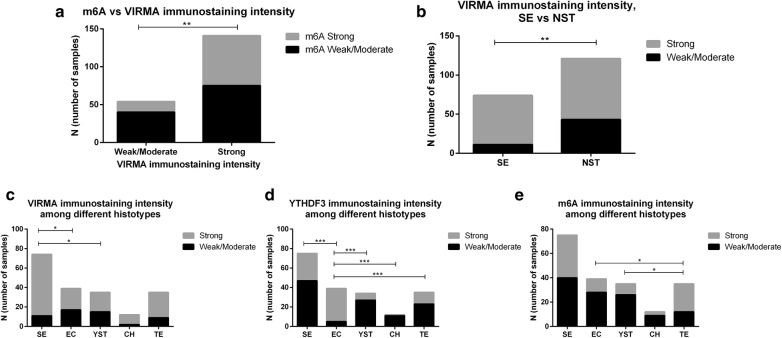

Immunostaining for m6A and VIRMA were significantly associated (p = 0.0092) (Fig. 6a). Indeed, the odds of having m6A strong immunoexpression was 2.5 times higher in samples with VIRMA strong staining intensity (OR = 2.514, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.3–5.0). Contrarily, no significant association was found between m6A and YTHDF3 immunoexpression, neither between VIRMA and YTHDF3 immunoexpression.

Fig. 6.

Immunostaining intensity of VIRMA, YTHDF3 and m6A. a m6A vs. VIRMA immunostaining intensity; b VIRMA immunostaining intensity among seminomas vs. non-seminomatous Tumors; c–e VIRMA, YTHDF3 and m6A immunostaining intensity among different tumor subtypes. SE Seminoma; EC embryonal carcinoma, YST pospubertal-type Yolk sac tumor, CH choriocarcinoma, TE postpubertal-type teratoma, NST non-seminomatous tumors

Considering tumor types, a significant association between VIRMA immunoexpression and SE (p = 0.0017) was depicted (Fig. 6b). Indeed, SEs were 3 times more likely to exhibit VIRMA strong immunoexpression intensity (OR = 3.157, 95% CI 1.5–6.6). On the other hand, m6A and YTHDF3 immunoexpression intensity did not differ between SEs and NSTs as a whole.

Differential immunoexpression of VIRMA, YTHDF3 and m6A was observed among TGCT subtypes. SEs commonly displayed stronger VIRMA immunoexpression intensity compared to EC and YST (adjusted p-value 0.012 and 0.032, respectively), whereas ECs displayed the strongest YTHDF3 immunoexpression among all subtypes (adjusted p-value < 0.001 for all) and TEs showed stronger m6A immunoexpression than YSTs and ECs (adjusted p-value 0.016 and 0.022, respectively) (Fig. 6c–e).

m6A, VIRMA and YTHDF3 immunoexpression in metastases

A total of 19 metastatic specimens from 12 patients were available for immunoexpression analysis (tumor components in metastases that were also present in the orchiectomy specimen, Additional file 5: Table S1). Three and eight primary tumor samples with weak/moderate VIRMA and YTHDF3 immunoexpression, respectively, displayed strong immunoreactivity in the respective metastases, whereas disagreement in m6A immunoexpression between primary and metastatic samples occurred in four cases, all for from strong to weak/moderate (Additional file 6: Figure S5a–c).

Most metastatic tumor samples showed strong VIRMA and YTHDF3 immunoexpression intensity, while weak/moderate staining was observed for m6A (Additional file 6: Figure S5d–f).

Regarding TEs [primary tumors (n = 35) and metastases (n = 9)] strong YTHDF3 immunoexpression was more frequent in metastatic specimens (p = 0.0063), whereas m6A immunoexpression was stronger in primary tumors (p = 0.0270) (Additional file 6: Figure S5g–i).

Association between immunoexpression and transcript levels

VIRMA transcript levels were significantly higher in tumor samples that exhibited strong VIRMA (p < 0.0001) and m6A (p = 0.0001) immunoexpression. No association was observed between VIRMA mRNA expression and YTHDF3 immunoexpression. Tumor samples with strong VIRMA immunoexpression also displayed significantly higher YTHDF3 transcript levels (p = 0.0303) whereas those with strong YTHDF3 protein expression disclosed a trend for higher YTHDF3 transcript levels (p = 0.0724) (Additional file 7: Figure S6).

Discussion

Although relatively infrequent, TGCTs are highly curable, carrying a generally good prognosis. Nevertheless, and despite continuous improvement of multimodal treatments, reduced fertility and second neoplasms remain important side effects. On the other hand, 15–20% of patients with disseminated disease eventually relapse, entailing poor prognosis (especially late relapses) whereas others develop cisplatin resistance, by still elusive mechanisms, and the therapeutic strategy for these patients is suboptimal. Thus, novel disease biomarkers that may improve TGCT diagnosis and subtyping, prediction of disease progression and patient monitoring are needed, and their clinical implementation might aid in tailoring and individualizing therapeutic strategies [9, 11, 13, 46–52]. Over the past few years, more than 140 RNA modifications have been uncovered, as well as their context-dependent role in regulating target RNAs fate, namely in stability, translation and splicing [53]. Among these modifications, m6A seems, by far, the most abundant in mammalian mRNAs and a handful of enzymes that regulate this covalent modification have been characterized, including adenosine methyltransferases (writers), demethylating enzymes (erasers) and m6A-binding proteins (readers). Recently, the amount of m6A in RNAs, fine-tune regulated by those proteins, has been suggested to impact in cancer onset and progression. These players may also constitute therapeutic targets [19, 22, 24, 25, 28, 54], thus representing potential cancer biomarkers.

Considering the role of m6A modification in germ cell development, and being TGCTs considered development-related cancers [7, 55], we hypothesized that changes in abundance of this mark and/or altered expression of the enzymes involved in its writing, reading or erasing might be potential TGCT biomarkers. For selection of the best candidates among all m6A-related players, the TCGA dataset was surveyed, and VIRMA (a component of the m6A writer complex) and YTHDF3 (reader) surfaced as the most commonly altered genes involved in m6A dynamics in TGCTs, prompting validation in an independent tissue cohort. Remarkably, SEs displayed higher VIRMA and YTHDF3 transcript levels compared to NSTs, in both cohorts (TCGA’s and IPO Porto’s), notwithstanding some differences in composition. Indeed, although the proportion of SEs was similar (46% vs. 42%, in IPO Porto’s and TCGA cohorts, respectively), IPO Porto’s cohort globally displayed a lower proportion of stage I tumors (64% in IPO Porto’s vs. 79% in TCGA). Nonetheless, most metastatic tumors were within the Good IGCCCG Prognosis group in both series (71% and 74%, respectively). Moreover, median age at diagnosis was 28 years in our cohort and 31 years in TCGA’s, slightly lower than the 35 years reported in most studies, which might be due to the lower proportion of SEs in both series, as SEs tend to be diagnosed a decade later that NSTs [3, 4]. Thus, the overall characteristics of both cohorts might be considered globally representative of TGCT patients.

TGCTs tumorigenesis relates to biological processes of spermatogenesis and stem-cell differentiation [55], with SE constituting the so-called default pathway for GCNIS cells, whereas reprogramming originates NST components, including more undifferentiated and embryonal forms like EC, but also extra-embryonal forms like YST and CH, and more differentiated and somatic forms like TE [14, 51]. Because RNAs m6A chemical modification has been implicated in stemness state maintenance [37, 56–59], changes in abundance of m6A mark and differential expression of respective regulating proteins might be expected along differentiation of the various TGCT components. SEs displayed the highest VIRMA and YTHDF3 mRNA levels, which were further confirmed at protein level for VIRMA, with no significant differences among NST subtypes. Considering their roles as m6A writer and reader, respectively, it is tempting to speculate whether m6A might contribute to the emergence and maintenance of the SE phenotype. Interestingly, knockdown of m6A writer complexes such as METTL3, METTL14, VIRMA, Hakai and WTAP lead to mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) self-renewal capacity loss, triggering differentiation [37, 56]. Hence, it has been proposed that m6A modification preferentially targets transcripts involved in development regulation, acting predominantly by reducing their stability and/or promoting degradation, maintaining mESCs at their ground state [37]. This observation is also in line with higher VIRMA expression observed in SEs compared to TEs, which represent the more differentiated TGCTs. TEs, however, showed the stronger m6A immunostaining intensity, suggesting that other writer complexes might be responsible for establishing m6A in this tumor subtype and/or that m6A modification might target other RNAs and even impart them a different fate. Intriguingly, this might parallel previous observations in mESCs, in which m6A displays conflicting results depending on the cell state: preserving stability of primed epiblast stem cells—EpiSCs—which are primed for differentiation, but inducing differentiation of naïve stem cells by degrading pluripotency factors [23, 58].

Overall, IHC results were concordant with transcript analysis, as tumors with strong VIRMA immunoexpression showed significantly higher VIRMA mRNA levels and a similar trend was depicted for YTHDF3. Moreover, a positive correlation between the writer and reader transcript levels was demonstrated in both cohorts, indicating they may cooperate in catalyzing and recognizing m6A modification in target RNAs. Furthermore, we found an association between higher expression of the writer (both at the transcript and immunohistochemical levels) and stronger m6A immunoexpression, suggesting that changes in m6A abundance might be due to VIRMA upregulation. Importantly, the observed immunoexpression patterns are coincidental with the expected subcellular localization. Indeed, VIRMA is mainly localized in nuclear bodies and nucleoplasm (correlating with granular/dot-like immunoexpression), whereas YTHDF3 is mostly cytoplasmic (especially in processing-bodies, imparting the granular staining observed in our samples) but it may also localize to nuclear speckles and nuclear membrane [19, 60–62]. Furthermore, m6A may be localized inside or outside the nucleus, imparting different biological significance [27], which may underlie the differences in immunoexpression depicted among distinct TGCT subtypes. On the other hand, immunostaining results in primary TGCTs and respective metastases was somewhat unexpected. Paradoxically, VIRMA and YTHDF3 immunostaining were increased in the metastatic context, whereas m6A modification displayed reduced intensity, suggesting that m6A erasure may occur during the metastatic process. In this context, a role for m6A erasers FTO and ALKBH5 in TGCT metastization is suggested. WTAP is fundamental for maintaining the writer complex inside the nuclear speckles, and it has been reported that WTAP knockdown results in m6A reduction mediated by sequestering of the writer complex in the cytoplasm; however, in our study, VIRMA immunoexpression in metastatic samples still occurred mainly in the nucleus [19, 63]. Nonetheless, our results should be interpreted with caution considering the limited number of metastatic samples and that most metastases were obtained following chemo- and/or radiotherapy, which may impact in m6A maintenance and detection.

Accurate discrimination of SEs from NST is key for patient management because SEs are particularly susceptible to chemo- and radiotherapy agents and display generally good prognosis, whereas NSTs show variable degrees of chemo- and radio-resistance and are more commonly associated with unfavorable prognostic features [6, 64, 65]. Thus, the ability of VIRMA transcript levels to discriminate SEs from NSTs is also of clinical significance and displayed similar results in both cohorts (AUC of 0.85 and 0.83 in IPO Porto’s and TCGA cohorts, respectively). Moreover, a gene panel comprising VIRMA and YTHDF3 further increased sensitivity and specificity. If confirmed in liquid biopsies in the future, these results outperform those of classical TGCT serum markers [66, 67] and might constitute promising biomarkers for patient monitoring.

The retrospective nature of this study and the validation cohort size are important limitations of this study. Nevertheless, our cohort is similar in many respects to that of TCGA and reflects many aspects of TGCTs epidemiology. Furthermore, all patients were evaluated and treated in a single institution by the same multidisciplinary team, entailing homogeneity in patients’ staging and clinical management. Although m6A IHC assay is not ideal and qualitative analysis carries a considerable inter- and intra-observer variation, it is a widespread and accessible technique that may corroborate transcript findings.

Conclusion

In summary, in this work we have used a bioinformatic tool to perform an in silico analysis, which allowed us to identify the most promising players to be further validated in a patient tissue cohort. We have shown that m6A writer VIRMA and reader YTHDF3 are differentially expressed among TGCTs subtypes, with significant overexpression in SEs compared to NSTs, suggesting a contribution to stemness maintenance. Furthermore, a positive correlation between VIRMA and YTHDF3 expression and an association with m6A abundance was also disclosed. Because VIRMA and YTHDF3 transcript levels accurately discriminate between SEs and NSTs, they might constitute novel biomarkers for patient management. Hence, our results confirm in silico findings and further enlighten the differentiation biology of TGCTs, which are development-related neoplasms. If confirmed in liquid biopsies, these players may also prove useful in the clinical setting.

To the best of our knowledge this is the first study assessing the value of m6A and related proteins in TGCTs. Additional research on m6A modification dynamics might further illuminate TGCTs biology and clinical behavior.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1. In silico analysis: ROC curve for discrimination among seminomas and non-seminomatous tumors based on VIRMA mRNA expression levels using TCGA database. Abbreviations: SE: Seminoma; NST: non-seminomatous tumor; AUC: area under the curve; CI: confidence interval.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Transcript levels of VIRMA and YTHDF3 among pure and matched mixed tumor forms. a VIRMA mRNA expression in pure seminoma vs. seminoma in mixed tumors; b VIRMA mRNA expression in pure embryonal carcinoma vs. embryonal carcinoma in mixed tumors; c VIRMA mRNA expression in pure teratoma vs. teratoma in mixed tumors; d YTHDF3 mRNA expression in pure seminoma vs. seminoma in mixed tumors; e YTHDF3 mRNA expression in pure embryonal carcinoma vs. embryonal carcinoma in Mixed tumors; f YTHDF3 mRNA expression in pure postpubertal-type teratoma vs. teratoma in mixed tumors. Abbreviations: SE: Seminoma; EC; embryonal carcinoma; TE: teratoma; Ref: reference genes GUSB and 18S.

Additional file 3: Figure S3. Correlation between mRNA expression levels of VIRMA and YTHDF3 in our cohort. Normalized for reference genes GUSB and 18S.

Additional file 4: Figure S4. VIRMA transcript levels among Stage (a), IGCCCG Prognostic Group (b) and presence of metastases at diagnosis (c). Abbreviations: IGCCCG: International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group; Ref: reference genes GUSB and 18S.

Additional file 5: Table S1. Immunostaining for m6A, YTHDF3 and VIRMA in TGCT tumor samples.

Additional file 6: Figure S5. Immunohistochemistry findings in metastatic tumor samples. Comparison between immunostaining intensity of VIRMA (a), YTHDF3 (b) and m6A (c) between primary tumor samples and matched metastatic samples; immunostaining intensity of VIRMA (d), YTHDF3 (e) and m6A (f) among different tumor subtypes; comparison between immunostaining intensity of VIRMA (g), YTHDF3 (h) and m6A (i) in primary and metastatic Teratoma samples. Abbreviations: SE: Seminoma; EC: embryonal carcinoma; YST: pospubertal-type yolk sac tumor; CH: choriocarcinoma; Met: metastases; TE: postpubertal-type Teratoma.

Additional file 7: Figure S6. Association between transcript and immunohistochemistry findings. a VIRMA mRNA expression vs. VIRMA immunostaining; b VIRMA mRNA expression vs. YTHDF3 immunostaining; c VIRMA mRNA expression vs. m6A immunostaining; d YTHDF3 mRNA expression vs. YTHDF3 immunostaining; e YTHDF3 mRNA expression vs. VIRMA immunostaining; f YTHDF3 mRNA expression vs. m6A immunostaining.

Authors’ contributions

JL collected the clinical data and reviewed histological specimens. IB and JO assisted in clinical data collection. MP guided the in silico analysis. JL and ALC performed the experiments. MC, RG and PL prepared the histological sections for immunohistochemistry. JL assessed the immunohistochemistry. JL and LA analyzed the data. JL drafted the manuscript. RH and CJ supervised the work and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Portuguese Oncology Institute of Porto (Comissão de Ética para a Saúde—CES-IPO Porto-1-2018). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

This work was supported by “FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia” under Grant “POCI-01-0145-FEDER-29043″. JL is supported by “FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia” under grant “SFRH/BD/132751/2017”. Part of this work was carried out in the framework of the European COST Action EPITRAN CA16120.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- AUC

area under the curve

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- CH

choriocarcinoma

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- EC

embryonal carcinoma

- EpiSCs

epiblast stem cells

- FFPE

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- GCNIS

germ cell neoplasia in situ

- GUSB

beta-glucoronidase

- IGCCCG

International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- m6A

N-6-methyladenosine

- mESCs

mouse embryonic stem cells

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- MGCT

mixed germ cell tumor

- NPV

negative predictive value

- NST

non-seminomatous tumor

- OR

odds ratio

- PPV

positive predictive value

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- rRNA

ribosomal RNA

- ROC

receiver operating characteristics

- rs

Spearman’s correlation coefficient

- RT-qPCR

real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SE

seminoma

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TE

postpubertal-type teratoma

- TGCT

testicular germ cell tumor

- WHO

World Health Organization

- YST

postpubertal-type yolk sac tumor

Footnotes

Rui Henrique and Carmen Jerónimo are joint senior authors

Contributor Information

João Lobo, Email: jpedro.lobo@ipoporto.min-saude.pt.

Ana Laura Costa, Email: alscosta94@gmail.com.

Mariana Cantante, Email: marianacantantecf@gmail.com.

Rita Guimarães, Email: ritaguimaraes.apct@gmail.com.

Paula Lopes, Email: lopesanapaula.s@gmail.com.

Luís Antunes, Email: luis.antunes@ipoporto.min-saude.pt.

Isaac Braga, Email: isaac.braga@gmail.com.

Jorge Oliveira, Email: urojorge@gmail.com.

Mattia Pelizzola, Email: mattia.pelizzola@iit.it.

Rui Henrique, Phone: +351 225084000, Email: henrique@ipoporto.min-saude.pt, Email: rmhenrique@icbas.up.pt.

Carmen Jerónimo, Phone: +351 225084000, Email: carmenjeronimo@ipoporto.min-saude.pt, Email: cljeronimo@icbas.up.pt.

References

- 1.Shah MN, Devesa SS, Zhu K, McGlynn KA. Trends in testicular germ cell tumours by ethnic group in the United States. Int J Androl. 2007;30:206–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trabert B, Chen J, Devesa SS, Bray F, McGlynn KA. International patterns and trends in testicular cancer incidence, overall and by histologic subtype, 1973–2007. Andrology. 2015;3:4–12. doi: 10.1111/andr.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moch H, Ulbright T, Humphrey P, Reuter V. WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. 4. IARC: Lyon; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beyer J, Albers P, Altena R, Aparicio J, Bokemeyer C, Busch J, Cathomas R, Cavallin-Stahl E, Clarke NW, Classen J, et al. Maintaining success, reducing treatment burden, focusing on survivorship: highlights from the third European consensus conference on diagnosis and treatment of germ-cell cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:878–888. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krege S, Beyer J, Souchon R, Albers P, Albrecht W, Algaba F, Bamberg M, Bodrogi I, Bokemeyer C, Cavallin-Stahl E, et al. European consensus conference on diagnosis and treatment of germ cell cancer: a report of the second meeting of the European Germ Cell Cancer Consensus group (EGCCCG): part I. Eur Urol. 2008;53:478–496. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lobo J, Gillis AJM, Jeronimo C, Henrique R, Looijenga LHJ. Human germ cell tumors are developmental cancers: impact of epigenetics on pathobiology and clinic. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:258. doi: 10.3390/ijms20020258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lobo J, Costa AL, Vilela-Salgueiro B, Rodrigues A, Guimaraes R, Cantante M, Lopes P, Antunes L, Jeronimo C, Henrique R. Testicular germ cell tumors: revisiting a series in light of the new WHO classification and AJCC staging systems, focusing on challenges for pathologists. Hum Pathol. 2018;82:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henrique R, Jeronimo C. Testicular germ cell tumors go epigenetics: will miR-371a-3p replace classical serum biomarkers? Eur Urol. 2017;71:221–222. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoun F, Kourie HR, Albisinni S, Roumeguere T. Will testicular germ cell tumors remain untargetable? Target Oncol. 2016;11:711–721. doi: 10.1007/s11523-016-0439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray MJ, Huddart RA, Coleman N. The present and future of serum diagnostic tests for testicular germ cell tumours. Nat Rev Urol. 2016;13:715–725. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2016.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Der Zwan YG, Stoop H, Rossello F, White SJ, Looijenga LH. Role of epigenetics in the etiology of germ cell cancer. Int J Dev Biol. 2013;57:299–308. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.130017ll. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costa AL, Lobo J, Jeronimo C, Henrique R. The epigenetics of testicular germ cell tumors: looking for novel disease biomarkers. Epigenomics. 2017;9:155–169. doi: 10.2217/epi-2016-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rijlaarsdam MA, Looijenga LH. An oncofetal and developmental perspective on testicular germ cell cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;29:59–74. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jantsch MF, Quattrone A, O’Connell M, Helm M, Frye M, Macias-Gonzales M, Ohman M, Ameres S, Willems L, Fuks F, et al. Positioning Europe for the EPITRANSCRIPTOMICS challenge. RNA Biol. 2018;15:829–831. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2018.1460996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davalos V, Blanco S, Esteller M. SnapShot: messenger RNA modifications. Cell. 2018;174(498–498):e491. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Z, Park E, Lin L, Xing Y. A panoramic view of RNA modifications: exploring new frontiers. Genome Biol. 2018;19:11. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1394-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaefer M, Kapoor U, Jantsch MF. Understanding RNA modifications: the promises and technological bottlenecks of the ‘epitranscriptome’. Open Biol. 2017;7:170077. doi: 10.1098/rsob.170077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR. Rethinking m(6)A readers, writers, and erasers. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2017;33:319–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacob R, Zander S, Gutschner T. The dark side of the epitranscriptome: chemical modifications in long non-coding RNAs. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2387. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frye M, Jaffrey SR, Pan T, Rechavi G, Suzuki T. RNA modifications: what have we learned and where are we headed? Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:365–372. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu N, Pan T. N6-methyladenosine-encoded epitranscriptomics. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Visvanathan A, Somasundaram K. mRNA traffic control reviewed: N6-methyladenosine (m(6) A) takes the driver’s seat. Bioessays. 2018;40:1700093. doi: 10.1002/bies.201700093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lian H, Wang QH, Zhu CB, Ma J, Jin WL. Deciphering the epitranscriptome in cancer. Trends Cancer. 2018;4:207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang S, Sun C, Li J, Zhang E, Ma Z, Xu W, Li H, Qiu M, Xu Y, Xia W, et al. Roles of RNA methylation by means of N(6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A) in human cancers. Cancer Lett. 2017;408:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batista PJ. The RNA modification N(6)-methyladenosine and Its Implications in Human Disease. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2017;15:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR. The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:313–326. doi: 10.1038/nrm3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esteller M, Pandolfi PP. The epitranscriptome of noncoding RNAs in cancer. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:359–368. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang S. Mechanism of N(6)-methyladenosine modification and its emerging role in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tusup M, Kundig T, Pascolo S. Epitranscriptomics of cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2018;9:42–55. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v9.i3.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang S, Chai P, Jia R, Jia R. Novel insights on m(6)A RNA methylation in tumorigenesis: a double-edged sword. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:101. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0847-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lobo J, Barros-Silva D, Henrique R, Jeronimo C. The emerging role of epitranscriptomics in cancer: focus on urological tumors. Genes (Basel) 2018;9:552. doi: 10.3390/genes9110552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen M, Wei L, Law CT, Tsang FH, Shen J, Cheng CL, Tsang LH, Ho DW, Chiu DK, Lee JM, et al. RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase-like 3 promotes liver cancer progression through YTHDF2-dependent posttranscriptional silencing of SOCS2. Hepatology. 2018;67:2254–2270. doi: 10.1002/hep.29683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma JZ, Yang F, Zhou CC, Liu F, Yuan JH, Wang F, Wang TT, Xu QG, Zhou WP, Sun SH. METTL14 suppresses the metastatic potential of hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating N(6) -methyladenosine-dependent primary MicroRNA processing. Hepatology. 2017;65:529–543. doi: 10.1002/hep.28885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang S, Zhao BS, Zhou A, Lin K, Zheng S, Lu Z, Chen Y, Sulman EP, Xie K, Bogler O, et al. m(6)A demethylase ALKBH5 maintains tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem-like cells by sustaining FOXM1 expression and cell proliferation program. Cancer Cell. 2017;31(591–606):e596. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishizawa Y, Konno M, Asai A, Koseki J, Kawamoto K, Miyoshi N, Takahashi H, Nishida N, Haraguchi N, Sakai D, et al. Oncogene c-Myc promotes epitranscriptome m(6)A reader YTHDF1 expression in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2018;9:7476–7486. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y, Li Y, Toth JI, Petroski MD, Zhang Z, Zhao JC. N6-methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:191–198. doi: 10.1038/ncb2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group International germ cell consensus classification: a prognostic factor-based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:594–603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fankhauser CD, Gerke TA, Roth L, Sander S, Grossmann NC, Kranzbuhler B, Eberli D, Sulser T, Beyer J, Hermanns T. Pre-orchiectomy tumor marker levels should not be used for International Germ Cell Consensus Classification (IGCCCG) risk group assignment. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145:781–785. doi: 10.1007/s00432-019-02844-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans JD. Straightforward statistics for the behavioral sciences. Pacific Grove: Brooks/Cole Publishing; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3:32–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::AID-CNCR2820030106>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schisterman EF, Perkins NJ, Liu A, Bondell H. Optimal cut-point and its corresponding Youden Index to discriminate individuals using pooled blood samples. Epidemiology. 2005;16:73–81. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000147512.81966.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vilela-Salgueiro B, Barros-Silva D, Lobo J, Costa AL, Guimaraes R, Cantante M, Lopes P, Braga I, Oliveira J, Henrique R, Jeronimo C. Germ cell tumour subtypes display differential expression of microRNA371a-3p. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2018;373:20170338. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2017.0338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costa AL, Moreira-Barbosa C, Lobo J, Vilela-Salgueiro B, Cantante M, Guimaraes R, Lopes P, Braga I, Oliveira J, Antunes L, et al. DNA methylation profiling as a tool for testicular germ cell tumors subtyping. Epigenomics. 2018;10:1511–1523. doi: 10.2217/epi-2018-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gonzalez-Exposito R, Merino M, Aguayo C. Molecular biology of testicular germ cell tumors. Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18:550–556. doi: 10.1007/s12094-015-1423-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cavallo F, Feldman DR, Barchi M. Revisiting DNA damage repair, p53-mediated apoptosis and cisplatin sensitivity in germ cell tumors. Int J Dev Biol. 2013;57:273–280. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.130135mb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ostrowski KA, Walsh TJ. Infertility with testicular cancer. Urol Clin North Am. 2015;42:409–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curreri SA, Fung C, Beard CJ. Secondary malignant neoplasms in testicular cancer survivors. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rajpert-De Meyts E, McGlynn KA, Okamoto K, Jewett MA, Bokemeyer C. Testicular germ cell tumours. Lancet. 2016;387:1762–1774. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Looijenga LH, Stoop H, Biermann K. Testicular cancer: biology and biomarkers. Virchows Arch. 2014;464:301–313. doi: 10.1007/s00428-013-1522-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Wit R. Management of germ cell cancer: lessons learned from a national database. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3078–3079. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.9907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boccaletto P, Machnicka MA, Purta E, Piatkowski P, Baginski B, Wirecki TK, de Crecy-Lagard V, Ross R, Limbach PA, Kotter A, et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D303–D307. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dai D, Wang H, Zhu L, Jin H, Wang X. N6-methyladenosine links RNA metabolism to cancer progression. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:124. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0129-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng L, Albers P, Berney DM, Feldman DR, Daugaard G, Gilligan T, Looijenga LHJ. Testicular cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:29. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wen J, Lv R, Ma H, Shen H, He C, Wang J, Jiao F, Liu H, Yang P, Tan L, et al. Zc3h13 regulates nuclear RNA m(6)A methylation and mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Mol Cell. 2018;69(1028–1038):e1026. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bertero A, Brown S, Madrigal P, Osnato A, Ortmann D, Yiangou L, Kadiwala J, Hubner NC, de Los Mozos IR, Sadee C, et al. The SMAD2/3 interactome reveals that TGFbeta controls m(6)A mRNA methylation in pluripotency. Nature. 2018;555:256–259. doi: 10.1038/nature25784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geula S, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Dominissini D, Mansour AA, Kol N, Salmon-Divon M, Hershkovitz V, Peer E, Mor N, Manor YS, et al. Stem cells. m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naive pluripotency toward differentiation. Science. 2015;347:1002–1006. doi: 10.1126/science.1261417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang D, Qiao J, Wang G, Lan Y, Li G, Guo X, Xi J, Ye D, Zhu S, Chen W, et al. N6-Methyladenosine modification of lincRNA 1281 is critically required for mESC differentiation potential. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;17:101. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu B, Li L, Huang Y, Ma J, Min J. Readers, writers and erasers of N(6)-methylated adenosine modification. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;47:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Patil DP, Pickering BF, Jaffrey SR. Reading m(6)A in the transcriptome: m(6)A-binding proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:113–127. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maity A, Das B. N6-methyladenosine modification in mRNA: machinery, function and implications for health and diseases. FEBS J. 2016;283:1607–1630. doi: 10.1111/febs.13614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ping XL, Sun BF, Wang L, Xiao W, Yang X, Wang WJ, Adhikari S, Shi Y, Lv Y, Chen YS, et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res. 2014;24:177–189. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feldman DR, Motzer RJ. Good-risk-advanced germ cell tumors: historical perspective and current standards of care. World J Urol. 2009;27:463–470. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0431-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Albers P, Albrecht W, Algaba F, Bokemeyer C, Cohn-Cedermark G, Fizazi K, Horwich A, Laguna MP, Nicolai N, Oldenburg J. European Association of U: guidelines on testicular cancer: 2015 update. Eur Urol. 2015;68:1054–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mir MC, Pavan N, Gonzalgo ML. Current clinical applications of testicular cancer biomarkers. Urol Clin North Am. 2016;43:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gilligan TD, Seidenfeld J, Basch EM, Einhorn LH, Fancher T, Smith DC, Stephenson AJ, Vaughn DJ, Cosby R, Hayes DF. American Society of Clinical O: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline on uses of serum tumor markers in adult males with germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3388–3404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. In silico analysis: ROC curve for discrimination among seminomas and non-seminomatous tumors based on VIRMA mRNA expression levels using TCGA database. Abbreviations: SE: Seminoma; NST: non-seminomatous tumor; AUC: area under the curve; CI: confidence interval.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Transcript levels of VIRMA and YTHDF3 among pure and matched mixed tumor forms. a VIRMA mRNA expression in pure seminoma vs. seminoma in mixed tumors; b VIRMA mRNA expression in pure embryonal carcinoma vs. embryonal carcinoma in mixed tumors; c VIRMA mRNA expression in pure teratoma vs. teratoma in mixed tumors; d YTHDF3 mRNA expression in pure seminoma vs. seminoma in mixed tumors; e YTHDF3 mRNA expression in pure embryonal carcinoma vs. embryonal carcinoma in Mixed tumors; f YTHDF3 mRNA expression in pure postpubertal-type teratoma vs. teratoma in mixed tumors. Abbreviations: SE: Seminoma; EC; embryonal carcinoma; TE: teratoma; Ref: reference genes GUSB and 18S.

Additional file 3: Figure S3. Correlation between mRNA expression levels of VIRMA and YTHDF3 in our cohort. Normalized for reference genes GUSB and 18S.

Additional file 4: Figure S4. VIRMA transcript levels among Stage (a), IGCCCG Prognostic Group (b) and presence of metastases at diagnosis (c). Abbreviations: IGCCCG: International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group; Ref: reference genes GUSB and 18S.

Additional file 5: Table S1. Immunostaining for m6A, YTHDF3 and VIRMA in TGCT tumor samples.

Additional file 6: Figure S5. Immunohistochemistry findings in metastatic tumor samples. Comparison between immunostaining intensity of VIRMA (a), YTHDF3 (b) and m6A (c) between primary tumor samples and matched metastatic samples; immunostaining intensity of VIRMA (d), YTHDF3 (e) and m6A (f) among different tumor subtypes; comparison between immunostaining intensity of VIRMA (g), YTHDF3 (h) and m6A (i) in primary and metastatic Teratoma samples. Abbreviations: SE: Seminoma; EC: embryonal carcinoma; YST: pospubertal-type yolk sac tumor; CH: choriocarcinoma; Met: metastases; TE: postpubertal-type Teratoma.

Additional file 7: Figure S6. Association between transcript and immunohistochemistry findings. a VIRMA mRNA expression vs. VIRMA immunostaining; b VIRMA mRNA expression vs. YTHDF3 immunostaining; c VIRMA mRNA expression vs. m6A immunostaining; d YTHDF3 mRNA expression vs. YTHDF3 immunostaining; e YTHDF3 mRNA expression vs. VIRMA immunostaining; f YTHDF3 mRNA expression vs. m6A immunostaining.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.