Abstract

Background

Trichomonas vaginalis is a protozoan parasite that causes trichomoniasis and annually infects approximately 276 million people worldwide. We observed an ambiguously higher probability of trichomoniasis in patients from the psychiatric department of Tri-Service General Hospital. Herein, we aimed to investigate the association between trichomoniasis and the risk of developing psychiatric disorders.

Methods

The nationwide population-based study utilized the database of the National Health Insurance (NHI) programme in Taiwan. A total of 46,865 subjects were enrolled in this study from 2000–2013, comprising 9373 study subjects with trichomoniasis and 37,492 subjects without trichomoniasis as the control group. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) of psychiatric disorders during the 14 years of follow-up.

Results

Of the study subjects with trichomoniasis, 875 (9.34%) developed psychiatric disorders compared with 1988 (5.30%) in the control group (P < 0.001). The adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of overall psychiatric disorders in the study subjects was 1.644 (95% confidence interval, CI: 1.514–1.766; P < 0.001). More specifically, the study subjects had a higher risk for developing an individual psychiatric disorder, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and substance abuse. Although metronidazole treatment reduced the risk for developing several subgroups of psychiatric disorders, significant reduction was detected for depression only. Furthermore, refractory trichomoniasis (trichomoniasis visits ≥ 2) enhanced the risk of psychiatric disorders.

Conclusions

We show herein that T. vaginalis infection increases the overall risk for psychiatric disorders. The novel role of T. vaginalis in developing psychiatric disorders deserves more attention, and the control of such a neglected pathogen is of urgent public health importance.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13071-019-3350-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Trichomonas vaginalis, Neglected tropical diseases, Psychiatric disorders

Background

Human trichomoniasis, caused by Trichomonas vaginalis, is the most widespread non-viral sexually transmitted infection, with approximately 276 million cases reported annually worldwide [1]. Trichomonas vaginalis infects both women and men, although 89% of trichomoniasis patients are women as a result of their higher occurrence of symptoms [2]. Men are often asymptomatic carriers of T. vaginalis infection, although dysuria, discharge and increased risk of infertility and prostate cancer have been reported [3]. Infected women may develop vaginitis, urethritis and cervicitis, potentially leading to serious health outcomes, such as infertility, preterm delivery, low-birth-weight infants, susceptibility to herpes simplex virus and human papillomavirus infection, and cervical cancer [4]. Trichomoniasis has been associated with an increased risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission [5].

In addition to the symptoms and signs, direct microscopic examination, including the wet mount test and Pap smear test, and traditional culture are the most common diagnostic methods for T. vaginalis infection. Moreover, rapid antigen detection and nucleic acid amplification test are also used for T. vaginalis diagnosis [6].

Current treatments for trichomoniasis include a single oral dose of metronidazole (MTZ; 2 g), a single oral dose of tinidazole (2 g), or a 7-day oral course of MTZ (500 mg twice daily) [7]. The prevalence of trichomoniasis varies among different subpopulations, ranging from 5.4% in family planning clinics and 17.3% in patients presenting to sexually transmitted disease clinics, to 32% among incarcerated women [8, 9]. The prevalence of T. vaginalis in women with recurrent urinary tract infections in Taiwan was 16.9% [10]. However, no large-scale epidemiological study of trichomoniasis in Taiwan has been conducted. Hence, it is necessary to understand the prevalence of trichomoniasis for women in Taiwan to improve their sexual and reproductive health.

Psychiatric disorders, also called mental disorders, are defined as clinically significant behavioral or psychological syndromes, with a high level of individual distress, anxiety and premature mortality [11]. In the USA, the regional disease burden attributable to mental disorders, neurological disorders, substance use disorders and self-harm comprises 19% of total disability-adjusted life-years and 34% of total years lived with disability in 2015 [12]. Mental health problems thereby represent important public health challenges worldwide. There is a growing interest in the role of microbes, such as viruses and protozoan parasites, in some psychiatric disorders [13–15]. For instance, several studies have shown impaired cognitive functions among individuals with schizophrenia exposed to neurotropic herpes simplex virus type 1 [16]. Additionally, it has been reported that prenatal maternal exposure to influenza, rubella, genital-reproductive infections and other pathogens are associated with schizophrenia and autism [17, 18]. The protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii is an extensively studied candidate that is associated with various psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia [19, 20]. Having a neurotropic nature and brain-damaging characteristic, T. gondii is a potential causative agent for mental and behavioral disorders [14]. However, there is limited evidence for the association of other protists and psychiatric disorders, especially those whose colonization sites are not directly linked to the central nervous system.

Recently, we observed an unexpected trend that trichomoniasis patients were accompanied by some psychiatric disorders in the Tri-Service General Hospital, raising the possibility that there is an association between T. vaginalis infection and the risk of psychiatric disorders. Hence, we conducted a nationwide population-based cohort study to verify whether T. vaginalis infection may lead to psychiatric disorders. Our findings underscore the potential risk of T. vaginalis for developing psychiatric disorders, providing a novel and clinically important role of this neglected protozoan parasite.

Methods

Data sources

The National Health Insurance (NHI) programme began in Taiwan in 1995 and covers more than 99% of entire population, with approximately 23 million beneficiaries [21]. The data were collected from the NHI Research Database (NHIRD) of Taiwan. The NHRID uses the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes to record diagnoses [22]. A subset of the NHIRD, the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000 (LHID 2000), was utilized to investigate the association between trichomoniasis and psychiatric disorders. The LHID 2000 provided a million individuals randomly selected from the entire NHI enrollee population in the year 2000. The ICD-9-CM codes of trichomoniasis-related diagnoses were included in the study group, such as trichomonal vulvovaginitis (ICD-9-CM 131.01), trichomonal urethritis (ICD-9-CM 131.02), other urogenital trichomoniasis (ICD-9-CM 131.09), trichomoniasis of other specified sites (ICD-9-CM 131.8) and unspecified trichomoniasis (ICD-9-CM 131.9). Detailed information of the ICD-9-CM codes used in this study is provided in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Study design and population

The patients newly diagnosed with trichomoniasis were selected from the LHID 2000 from 1st January 2000 to 31st December 2013. The following criteria were excluded: (i) patients with trichomoniasis before the index date; (ii) patients with psychiatric disorders before tracking; (iii) patients younger than 18 years of age; and (iv) gender is male or unknown. Ultimately, a total of 9373 subjects with trichomoniasis were included in the study group. The non-trichomoniasis control group (37,492 individuals) was established by matching the age and index year with a 4-fold ratio to the study group.

Covariates

We examined the sociodemographic factors in the study and control groups, including age, monthly income, season, place of residence, urbanization level and hospital level. The patients were classified into three groups based on age: 18–44 years; 45–64 years; and ≥ 65 years. The monthly income in New Taiwan Dollars (NTD) was divided into three groups: <18,000; 18,000–34,999; and ≥35,000. Four seasons (spring, summer, autumn and winter) were considered. The patients living in different areas of Taiwan, including northern, middle, southern, and eastern Taiwan, as well as the outlets islands were compared. The patients were categorized into four urbanization levels from the highest (1) to the lowest (4). Three levels for hospitals where the patients sought medical attention were considered: medical centers; regional hospitals; and local hospitals.

Main outcome measures

All study participants were followed from the index date until the onset of all recorded psychiatric disorders in the NHIRD. The incidences and risk of each individual psychiatric disorder, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and substance abuse, were compared between the study group and the control group. The incidences and risk for overall and subgroups of psychiatric disorders in the trichomoniasis patients treated with MTZ were compared with the untreated trichomoniasis patients and the non-trichomoniasis group.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software v.22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). A Chi-square test was used to analyze the categorical variables. Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the differences between the study and control groups. Differences in the risk of psychiatric disorders in the study and control groups were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method with a log-rank test and presented as a survival curve. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to determine the risk of psychiatric disorder, and the data were expressed as aHR with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Demographic characteristics of the study population at the baseline and endpoint

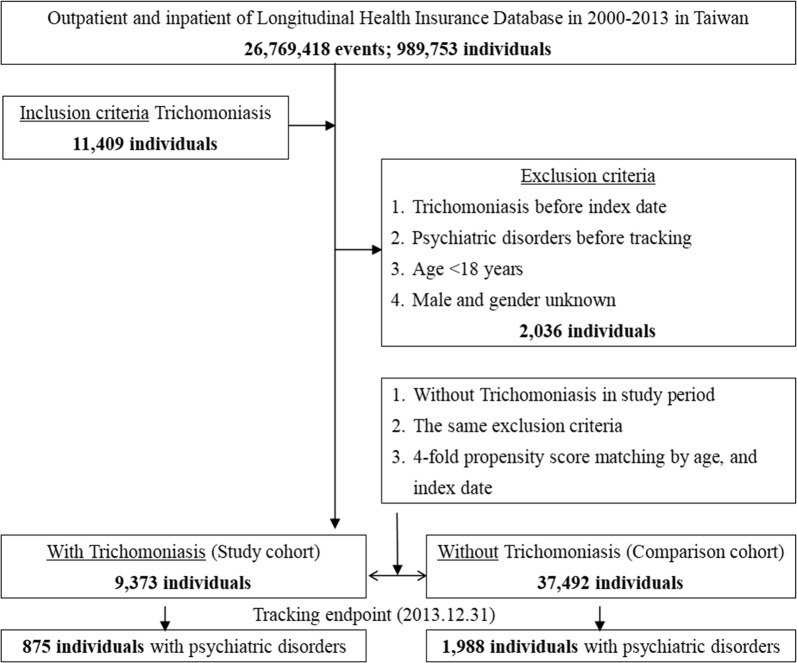

Based on propensity score matching (the ratio of the study population to the control population was 1:4), there were 9373 individuals with trichomoniasis in the study group and 37,492 individuals without trichomoniasis in the control group (Fig. 1). The demographic characteristics of the study and control populations at the baseline are described in Table 1. There was no significant difference in age between the control and study groups (42.06 ± 16.09 vs 42.09 ± 16.71). The percentage of the population whose monthly income less than NTD $18,000 in the study group was significantly higher than the control group (98.13 vs 88.15%; P < 0.001). Compared with the control population, the study population had more medical visits in summer (26.51 vs 23.95%; P < 0.001), with a higher proportion of patients living in eastern Taiwan (14.04 vs 4.35%; P < 0.001). Regarding the medical care system, more patients with trichomoniasis sought medical help in regional hospitals as compared to the non-trichomoniasis group (49.89 vs 29.59%; P < 0.001). The demographic characteristics of the study and control populations at the tracking endpoint are described in Additional file 2: Table S2. Except the difference in age between the study and control groups (45.49 ± 19.64 vs 46.85 ± 17.85; t-test, P < 0.001), all the trends of characteristics between trichomoniasis subjects and non-trichomoniasis subjects were similar to those observed at the baseline.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study and control subject’s collection from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database, a subset of the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of Taiwan. The subjects were tracked from 2000 to 2013

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study and control populations at the baseline

| Characteristic | Total | With | Without | P-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 46,865 | 9373 | 20.00 | 37,492 | 80.00 | ||

| Age (years) | 42.08 ± 16.59 | 42.06 ± 16.09 | 42.09 ± 16.71 | 0.889 | |||

| Age group (years) | 0.999 | ||||||

| 18–44 | 28,350 | 60.49 | 5670 | 60.49 | 22,680 | 60.49 | |

| 45–64 | 13,615 | 29.05 | 2723 | 29.05 | 10,892 | 29.05 | |

| ≥ 65 | 4900 | 10.46 | 980 | 10.46 | 3920 | 10.46 | |

| Insured premium (NT$) | <0.001 | ||||||

| < 18,000 | 42,248 | 90.15 | 9198 | 98.13 | 33,050 | 88.15 | |

| 18,000–34,999 | 3221 | 6.87 | 154 | 1.64 | 3067 | 8.18 | |

| ≥ 35,000 | 1396 | 2.98 | 21 | 0.22 | 1375 | 3.67 | |

| CCI | 0.48 ± 1.40 | 0.61 ± 1.46 | 0.45 ± 1.39 | <0.001 | |||

| Season | <0.001 | ||||||

| Spring (March-May) | 12,194 | 26.02 | 2380 | 25.39 | 9814 | 26.18 | |

| Summer (June-August) | 11,466 | 24.47 | 2485 | 26.51 | 8981 | 23.95 | |

| Autumn (September-November) | 11,242 | 23.99 | 2212 | 23.60 | 9030 | 24.09 | |

| Winter (December-February) | 11,963 | 25.53 | 2296 | 24.50 | 9667 | 25.78 | |

| Location | <0.001 | ||||||

| Northern Taiwan | 18,550 | 39.58 | 3241 | 34.58 | 15,309 | 40.83 | |

| Middle Taiwan | 13,405 | 28.60 | 2478 | 26.44 | 10,927 | 29.14 | |

| Southern Taiwan | 11,774 | 25.12 | 2331 | 24.87 | 9443 | 25.19 | |

| Eastern Taiwan | 2947 | 6.29 | 1316 | 14.04 | 1631 | 4.35 | |

| Outlets islands | 189 | 0.40 | 7 | 0.07 | 182 | 0.49 | |

| Urbanization level | <0.001 | ||||||

| 1 (The highest) | 16,142 | 34.44 | 2345 | 25.02 | 13,797 | 36.80 | |

| 2 | 20,160 | 43.02 | 4746 | 50.63 | 15,414 | 41.11 | |

| 3 | 3815 | 8.14 | 630 | 6.72 | 3185 | 8.50 | |

| 4 (The lowest) | 6748 | 14.40 | 1652 | 17.63 | 5096 | 13.59 | |

| Level of care | <0.001 | ||||||

| Hospital center | 14,329 | 30.58 | 2863 | 30.55 | 11,466 | 30.58 | |

| Regional hospital | 15,771 | 33.65 | 4676 | 49.89 | 11,095 | 29.59 | |

| Local hospital | 16,765 | 35.77 | 1834 | 19.57 | 14,931 | 39.82 | |

aChi-square/Fisher’s exact test on categorical variables and t-test on continuous variables

Abbreviation: CCI, Charlson comorbidity index

Association of trichomoniasis with psychiatric disorders

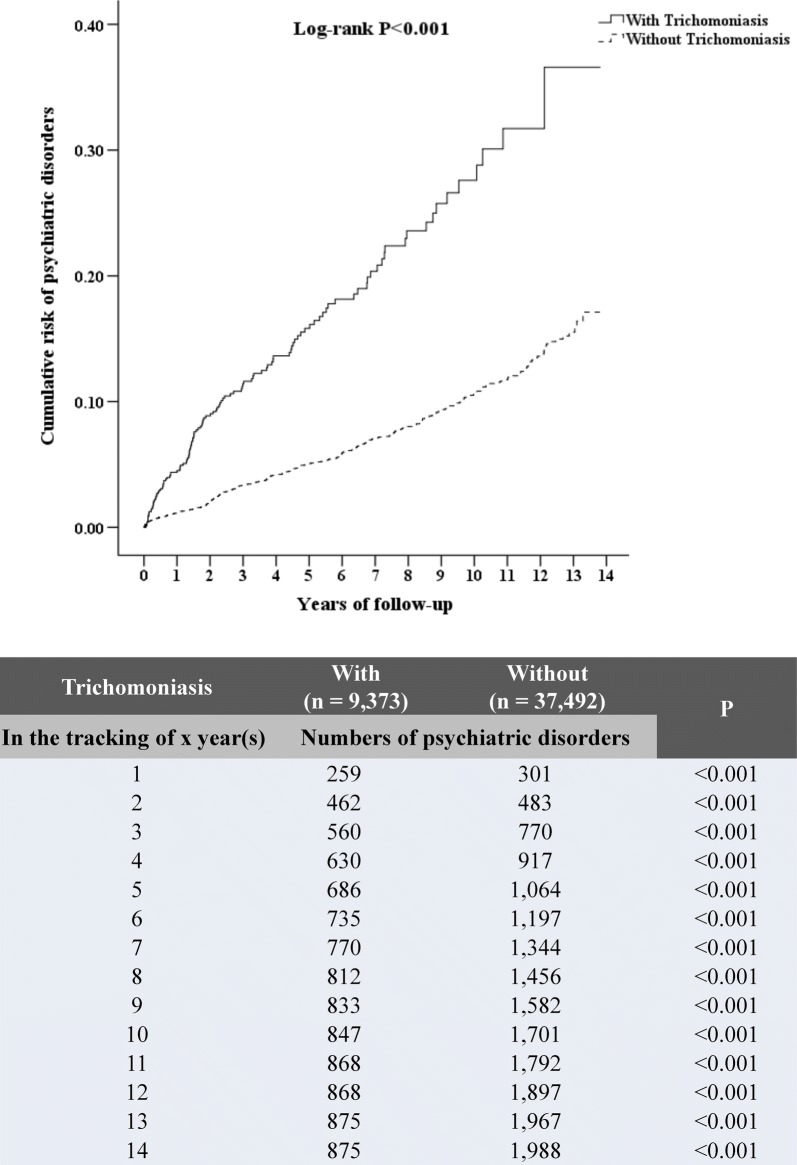

The incidences of psychiatric disorders were higher for study subjects with trichomoniasis (875 subjects, 9.34%) than control subjects (1988 subjects, 5.3%) (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Additionally, Kaplan-Meier analysis for the cumulative risk of psychiatric disorders during 14 years of follow-up showed a statistical difference in the study group compared with the control group (log-rank P < 0.001), and this difference began from the first year of tracking (Fig. 2). The medium duration from the diagnosis of T. vaginalis infection to the onset of overall psychiatric disorder was 2.17 years. Additionally, the medium duration from the diagnosis of T. vaginalis infection to the onset of individual psychiatric disorder ranged between 0.79–2.34 years (Additional file 3: Table S3). Furthermore, the incidences for the subgroups of the psychiatric disorders were significantly higher in the subjects with trichomoniasis than in the control group, including depression (3.96 vs 2.17%; P < 0.001), anxiety (3.14 vs 1.47%; P < 0.001), bipolar disorder (0.45 vs 0.28%; P = 0.011), schizophrenia (0.97 vs 0.39%; P < 0.001), substance abuse (0.9 vs 0.24%; P < 0.001) and other psychiatric disorders (0.82 vs 0.15%; P < 0.001). The risk of psychiatric disorders in subjects with trichomoniasis was analyzed by Cox regression and presented as adjusted hazard ratio (aHR), with reference to the non-trichomoniasis group (Table 3). The trichomoniasis patients showed a higher risk of overall psychiatric disorders, with an aHR of 1.644 (95% CI: 1.514–1.766; P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Incidence of psychiatric disorders in the trichomoniasis patients compared with the control group

| Variable | Total | With | Without | P-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 46,865 | 9,373 | 20.00 | 37,492 | 80.00 | ||

| Psychiatric disorders | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 44,002 | 93.89 | 8498 | 90.66 | 35,504 | 94.70 | |

| With | 2863 | 6.11 | 875 | 9.34 | 1988 | 5.30 | |

| Depression | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 45,682 | 97.48 | 9002 | 96.04 | 36,680 | 97.83 | |

| With | 1183 | 2.52 | 371 | 3.96 | 812 | 2.17 | |

| Anxiety | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 46,018 | 98.19 | 9079 | 96.86 | 36,939 | 98.53 | |

| With | 847 | 1.81 | 294 | 3.14 | 553 | 1.47 | |

| Bipolar disorders | 0.011 | ||||||

| Without | 46,718 | 99.69 | 9331 | 99.55 | 37,387 | 99.72 | |

| With | 147 | 0.31 | 42 | 0.45 | 105 | 0.28 | |

| PTSD/ASD | 0.375 | ||||||

| Without | 46,816 | 99.90 | 9366 | 99.93 | 37,450 | 99.89 | |

| With | 49 | 0.10 | 7 | 0.07 | 42 | 0.11 | |

| Schizophrenia | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 46,627 | 99.49 | 9282 | 99.03 | 37,345 | 99.61 | |

| With | 238 | 0.51 | 91 | 0.97 | 147 | 0.39 | |

| Substance abuse | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 46,690 | 99.63 | 9289 | 99.10 | 37,401 | 99.76 | |

| With | 175 | 0.37 | 84 | 0.90 | 91 | 0.24 | |

| Other psychiatric disorders | <0.001 | ||||||

| Without | 46,732 | 99.72 | 9296 | 99.18 | 37,436 | 99.85 | |

| With | 133 | 0.28 | 77 | 0.82 | 56 | 0.15 | |

aChi-square/Fisher’s exact test on categorical variables and t-test on continuous variables

Abbreviation: PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; ASD, acute stress disorder

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for cumulative risk of psychiatric disorders stratified by trichomoniasis with the log-rank test. The numbers of psychiatric disorders in the patients with trichomoniasis and the non-trichomoniasis group are shown during the 14 years of follow-up

Table 3.

Risk of psychiatric disorders in the trichomoniasis subjects identified by using Cox regression

| Variable | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without trichomoniasis | Reference | ||

| With trichomoniasis | 1.644 | 1.514–1.766 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: Adjusted HR, adjusted hazard ratio (adjusted for the variables listed in Table 1); CI, confidence interval

Risk of psychiatric disorders in the trichomoniasis group stratified by covariates

The risk of psychiatric disorders in the trichomoniasis group stratified by variables was further evaluated (Table 4). Except for level of medical care, almost all study subjects kept the higher risk of developing psychiatric disorders irrespective of being stratified by independent variables. Specifically, the trichomoniasis patients stratified by the different age groups revealed that the subjects aged 45–64 years had the highest risk (aHR = 2.637; P < 0.001) compared with the non-trichomoniasis control. Additionally, study subjects which had a monthly income of less than NTD $18,000 (aHR = 1.669; P < 0.001) were associated with a higher risk of psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, patients with the lowest urbanization level (level 4) (aHR = 3.814; P < 0.001) had a markedly increased risk of psychiatric disorders.

Table 4.

Risk of psychiatric disorders in the trichomoniasis subjects stratified by variables using Cox regression

| Stratified | With vs without trichomoniasis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P-value | ||

| Total | 1.644 | 1.514–1.766 | <0.001 | |

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 18–44 | 1.155 | 1.017–1.312 | 0.027 | |

| 45–64 | 2.637 | 2.325–2.991 | <0.001 | |

| ≥ 65 | 0.923 | 0.696–1.224 | 0.577 | |

| Insured premium (NT$) | ||||

| < 18,000 | 1.669 | 1.536–1.813 | <0.001 | |

| 18,000–34,999 | 0.000 | – | 0.937 | |

| ≥ 35,000 | 0.000 | – | 0.986 | |

| Season | ||||

| Spring | 1.551 | 1.307–1.841 | <0.001 | |

| Summer | 2.309 | 2.010–2.651 | <0.001 | |

| Autumn | 1.110 | 0.906–1.360 | 0.314 | |

| Winter | 1.428 | 1.195–1.706 | <0.001 | |

| Urbanization level | ||||

| 1 (the highest) | 1.803 | 1.596–2.037 | <0.001 | |

| 2 | 1.428 | 1.209–1.688 | <0.001 | |

| 3 | 1.291 | 1.074–1.552 | 0.007 | |

| 4 (the lowest) | 3.814 | 2.752–5.285 | <0.001 | |

| Level of care | ||||

| Hospital center | 1.479 | 1.315–1.664 | <0.001 | |

| Regional hospital | 1.594 | 1.354–1.877 | <0.001 | |

| Local hospital | 2.011 | 1.693–2.389 | <0.001 | |

Abbreviations: Adjusted HR, adjusted hazard ratio (adjusted for the variables listed in Table 1); CI, confidence interval; NT$, New Taiwan Dollars

Reduced risk for the subgroups of psychiatric disorders in the trichomoniasis subjects following MTZ treatment

The risk of the main subgroups of psychiatric disorders in trichomoniasis patients was examined (Table 5). Compared with the non-trichomoniasis group, trichomoniasis subjects had a higher risk of substance abuse (aHR = 2.794; 95% CI: 2.035–3.834; P < 0.001), anxiety (aHR = 2.011; 95% CI: 1.738–2.327; P < 0.001), schizophrenia (aHR = 1.981; 95% CI: 1.495–2.624; P < 0.001), bipolar disorders (aHR = 1.784; 95% CI: 1.241–2.565; P < 0.001) and depression (aHR = 1.675; 95% CI: 1.474–1.904; P < 0.001). There was no statistical significance in the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder or acute stress disorder (PTSD/ASD) and other psychiatric disorders between the trichomoniasis and non-trichomoniasis groups.

Table 5.

Risk of psychiatric disorders subgroup in the trichomoniasis patients treated with MTZ identified by using Cox regression

| Psychiatric disorder subgroup | Trichomoniasis and metronidazole (MTZ) | Competing risk in the model | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Event | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Overall | Without trichomoniasis | 37,492 | 198 | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis | 9373 | 875 | 1.644 | 1.514–1.766 | <0.001 | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis, without MTZ | 6433 | 630 | 1.732 | 1.577–1.902 | <0.001 | Ref. | ||||||

| With trichomoniasis, with MTZ | 2940 | 245 | 1.458 | 1.271–1.672 | <0.001 | 0.876 | 0.739–1.039 | 0.128 | ||||

| Depression | Without trichomoniasis | 37,492 | 812 | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis | 9373 | 371 | 1.675 | 1.474–1.904 | <0.001 | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis, without MTZ | 6433 | 266 | 1.865 | 1.613–2.156 | <0.001 | Ref. | ||||||

| With trichomoniasis, with MTZ | 2940 | 105 | 1.335 | 1.083–1.647 | 0.007 | 0.639 | 0.493–0.829 | 0.001 | ||||

| Anxiety | Without trichomoniasis | 37,492 | 553 | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis | 9373 | 294 | 2.011 | 1.738–2.327 | <0.001 | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis, without MTZ | 6433 | 231 | 2.120 | 1.807–2.486 | <0.001 | Ref. | ||||||

| With trichomoniasis, with MTZ | 2940 | 63 | 1.701 | 1.301–2.222 | <0.001 | 0.948 | 0.692–1.300 | 0.741 | ||||

| Bipolar disorder | Without trichomoniasis | 37,492 | 105 | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis | 9373 | 42 | 1.784 | 1.241–2.565 | 0.002 | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis, without MTZ | 6433 | 35 | 2.219 | 1.497–3.287 | <0.001 | Ref. | ||||||

| With trichomoniasis, with MTZ | 2940 | 7 | 0.908 | 0.418–1.972 | 0.807 | 0.481 | 0.207–1.118 | 0.089 | ||||

| PTSD/ASD | Without trichomoniasis | 37,492 | 42 | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis | 9373 | 7 | 0.792 | 0.354–1.772 | 0.570 | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis, without MTZ | 6433 | 7 | 1.015 | 0.450–2.288 | 0.972 | Ref. | ||||||

| With trichomoniasis, with MTZ | 2940 | 0 | 0.0001 | – | 0.963 | 0.0001 | – | 0.971 | ||||

| Schizophrenia | Without trichomoniasis | 37,492 | 147 | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis | 9373 | 91 | 1.981 | 1.495–2.624 | <0.001 | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis, without MTZ | 6433 | 70 | 2.315 | 1.699–3.156 | <0.001 | Ref. | ||||||

| With trichomoniasis, with MTZ | 2940 | 21 | 1.352 | 0.838–2.180 | 0.216 | 0.690 | 0.385–1.237 | 0.212 | ||||

| Substance abuse | Without trichomoniasis | 37,492 | 91 | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis | 9373 | 84 | 2.794 | 2.035–3.834 | <0.001 | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis, without MTZ | 6433 | 56 | 2.97 | 2.073–4.256 | <0.001 | Ref. | ||||||

| With trichomoniasis, with MTZ | 2940 | 28 | 2.516 | 1.615–3.919 | <0.001 | 0.978 | 0.428–2.686 | 0.057 | ||||

| Other psychiatric disorders | Without trichomoniasis | 37,492 | 56 | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis | 9373 | 77 | 1.098 | 0.872–1.211 | 0.184 | |||||||

| With trichomoniasis, without MTZ | 6433 | 49 | 1.012 | 0.642–1.19 | 0.872 | Ref. | ||||||

| With trichomoniasis, with MTZ | 2940 | 28 | 1.584 | 1.104–1.984 | 0.001 | 1.971 | 1.169–3.322 | 0.011 | ||||

Abbreviations: MTZ, metronidazole; Adjusted HR, adjusted hazard ratio (adjusted for the variables listed in Table 1); CI, confidence interval; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; ASD, acute stress disorder; Ref., reference

The risk for the subgroups of psychiatric disorders in the trichomoniasis subjects treated with MTZ was examined compared with the non-trichomoniasis group and the trichomoniasis subjects without MTZ treatment (Table 5). The trichomoniasis subjects treated with MTZ had a lower risk of developing bipolar disorder and schizophrenia than the trichomoniasis subjects without MTZ treatment, with aHRs of 0.908 (95% CI: 0.418–1.972; P = 0.807) and 1.352 (95% CI: 0.838–2.180; P = 0.216), respectively, with no statistical difference between the MTZ-treated group and the non-trichomoniasis control. Although MTZ treatment had a lower risk for developing several subgroups of psychiatric disorders with reference to the untreated trichomoniasis subjects, significant reduction was detected for depression only (aHR = 0.639; 95% CI: 0.493–0.829; P = 0.001).

Increased risk of psychiatric disorders in subjects with refractory trichomoniasis

It is estimated that approximately 5–10% of trichomoniasis patients display resistance to drug treatment [23, 24]. We also evaluated the risk for psychiatric disorders in the trichomoniasis subjects who sought medical help more than once (Table 6). Compared with the non-trichomoniasis group, the risk for overall psychiatric disorders in subjects with trichomoniasis was proportional to the number of medical visits. Except for bipolar disorder and PTSD/ASD, refractory trichomoniasis patients (trichomoniasis visits ≥2) had a higher risk for the other psychiatric disorders (P < 0.001) compared with the patients who sought medical help only once.

Table 6.

Risk of psychiatric disorders subgroup among study population and trichomoniasis cohort identified by using Cox regression

| Psychiatric disorders subgroup | Trichomoniasis visits | Study population | Trichomoniasis cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Event | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Overall | 0 (without trichomoniasis) | 37,492 | 1988 | Ref. | |||||

| 1 trichomoniasis visit | 9051 | 809 | 2.560 | 2.353–2.784 | <0.001 | Ref. | |||

| ≥ 2 trichomoniasis visits | 322 | 66 | 7.676 | 5.953–9.898 | <0.001 | 2.664 | 2.047–3.467 | <0.001 | |

| Depression | 0 | 37,492 | 812 | Ref. | |||||

| 1 | 9051 | 341 | 2.712 | 2.381–3.089 | <0.001 | Ref. | |||

| ≥ 2 | 322 | 30 | 8.306 | 5.667–12.173 | <0.001 | 2.594 | 1.741–3.866 | <0.001 | |

| Anxiety | 0 | 37,492 | 553 | Ref. | |||||

| 1 | 9051 | 271 | 2.975 | 2.562–3.454 | <0.001 | Ref. | |||

| ≥ 2 | 322 | 23 | 10.674 | 6.853–16.623 | <0.001 | 3.472 | 2.199–5.482 | <0.001 | |

| Bipolar disorder | 0 | 37,492 | 105 | Ref. | |||||

| 1 | 9051 | 42 | 2.679 | 1.854–3.873 | <0.001 | Ref. | |||

| ≥ 2 | 322 | 0 | 0.000 | – | 0.968 | <0.0001 | – | 0.972 | |

| PTSD/ASD | 0 | 37,492 | 42 | Ref. | |||||

| 1 | 9051 | 7 | 1.013 | 0.456–2.298 | 0.978 | Ref. | |||

| ≥ 2 | 322 | 0 | 0.000 | – | 0.988 | <0.0001 | – | 0.989 | |

| Schizophrenia | 0 | 37,492 | 147 | Ref. | |||||

| 1 | 9051 | 84 | 3.949 | 2.992–5.212 | <0.001 | Ref. | |||

| ≥ 2 | 322 | 7 | 12.471 | 5.739–27.101 | <0.001 | 2.806 | 1.260–6.247 | 0.012 | |

| Substance abuse | 0 | 37,492 | 91 | Ref. | |||||

| 1 | 9051 | 80 | 1.535 | 1.301–2.011 | <0.001 | Ref. | |||

| ≥ 2 | 322 | 4 | 3.897 | 2.049–7.122 | <0.001 | 3.286 | 1.870–5.864 | <0.001 | |

| Other psychiatric disorders | 0 | 37,492 | 56 | Ref. | |||||

| 1 | 9051 | 66 | 1.862 | 1.503–2.188 | <0.001 | Ref. | |||

| ≥ 2 | 322 | 11 | 5.897 | 3.402–9.864 | <0.001 | 5.642 | 2.864–7.862 | <0.001 | |

Abbreviations: Adjusted HR, adjusted hazard ratio (adjusted for the variables listed in Table 1); CI, confidence interval; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; ASD, acute stress disorder; Ref., reference

Association of trichomoniasis with other sexually transmitted infections

It has been shown that T. vaginalis infection was associated with other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Treponema pallidum and HIV [25–27]. Our data indicated that 3.03% of the subjects with trichomoniasis were co-infected with N. gonorrhoeae or T. pallidum, 0.61% co-infected with N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis, and 0.12% co-infected with T. pallidum or C. trachomatis (Additional file 4: Table S4). Combined analysis revealed that 13.99% of subjects with trichomoniasis were co-infected with one of these three common STIs (N. gonorrhoeae, T. pallidum or C. trachomatis). Additionally, a total of 12 trichomoniasis subjects were infected with HIV, whereas 4 non-trichomoniasis subjects were infected with HIV (Additional file 5: Table S5). Among the trichomoniasis subjects, 5 and 3 subjects were infected with HIV before and after the index date, respectively. For the non-trichomoniasis subjects, 1 and 2 cases were infected with HIV before and after the index date, respectively. All HIV-positive patients were treated.

Discussion

The trichomoniasis subjects enrolled in this study had a higher risk of overall psychiatric disorders, with an aHR of 1.644, as compared with the non-trichomoniasis control. This means that patients with trichomoniasis had a 1.644-fold increased risk for developing psychiatric disorders. The Kaplan-Meier analysis also supported the cumulative risk for psychiatric disorders in the trichomoniasis subjects during 14 years of follow-up (log-rank P < 0.001). More specifically, the trichomoniasis subjects had a significantly increased risk of depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and substance abuse. These results highlight the novel role of T. vaginalis in causing psychiatric disorders, and that clinicians should pay more attention to the possible risk resulting from this neglected tropical disease.

Previous studies have reported that some psychiatric disorders are associated with inflammatory diseases, such as periodontitis [28], psoriasis [29] and allergic diseases[30]. The underlying mechanism of this association is possibly due to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, which have been proved to be involved in the development of depression, anxiety and bipolar disorders. Trichomonas vaginalis infection has been shown to induce IL-8 secretion from primary human monocytes [31] and the symbiotic relationship with Mycoplasma hominis enables induction of an array of inflammatory cytokines in a macrophage cell line [32]. In addition to causing local inflammation, T. vaginalis also induces systemic immune response in infected pregnant women, resulting in higher concentrations of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and C-reactive protein in serum of patients [33]. Further investigation is needed to clarify whether the T. vaginalis-induced immune response plays a role in developing psychiatric disorders.

Another possibility is that a behavioral pathway may link T. vaginalis infection and the risk of psychiatric disorders. For instance, women with T. vaginalis infection might present many vaginal symptoms that may affect their sexual life. Their partners might be annoyed with the diagnoses which can complicate their sexual relationship. Therefore, these problems associated with difficulties in getting cured might increase anxiety and other common mental disorders. Additionally, it has been reported that there is an association between high-risk sexual behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases in patients with psychiatric disorders [34]. Thus, the higher T. vaginalis infection in psychiatric patients may alternatively have resulted from high-risk sexual behaviors of patients during their prodromal stage.

We found that trichomoniasis subjects aged 45–64 years had a higher risk of psychiatric disorders than those aged 18–44 years. Since the maximal follow-up time is 14 years, we proposed that a certain portion of the trichomoniasis population aged 18–44 years may not reach the age of onset for most major psychiatric disorders [35]. Another possible reason for this observation may be due to the menopausal transition, a period late in a woman’s reproductive life before the final menstruation, typically occurring between the ages of 40 and 55 years. Previous studies demonstrated that women with symptomatic menopausal transition may have a higher risk for developing subsequent psychiatric disorders, especially depression [36], anxiety [37] and bipolar disorder [38], thereby enhancing the risk in the trichomoniasis subjects.

Mental disorders contribute to 7% of the global burden of disease as estimated by disability adjusted life years in the world; this is rising, especially in low- and middle-income countries [39]. Low income has been demonstrated to be directly linked with psychiatric disorders [40]. Indeed, we have revealed that the trichomoniasis subjects with a monthly income less than NTD $18,000 were associated with a higher risk of psychiatric disorders.

Although MTZ treatment for the trichomoniasis patients had a lower risk for developing overall psychiatric disorders, the differences between the treated and untreated groups was not statistically significant. Specifically, MTZ treatment was remarkably associated with a decreased risk of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, suggesting that T. vaginalis infection is closely related with these two psychiatric disorders. Additionally, MTZ treatment was associated with a lower risk for developing depression as compared with the untreated group. Based on these findings, it is likely that trichomoniasis may directly or indirectly involve the process of development for specific psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, increasing reports of failures in the treatment of trichomoniasis and the rising prevalence of MTZ-resistant T. vaginalis isolates have occurred [23, 41, 42]. Hence, the differences in treatment outcomes of patients due to drug resistance may also influence the risk for developing psychiatric disorders. Indeed, our further analysis of the trichomoniasis subjects who sought medical help more than once (≥ 2 times) had a higher risk for psychiatric disorders, which is likely caused by drug resistance. Our data revealed that 68.6% patients with trichomoniasis were not treated. A recent study in Belgium demonstrated that 58.1% of women repeatedly positive for T. vaginalis infection had received no treatment; this was attributed to low awareness, poor attention, and failure of contact tracing of physicians [43].

One of the major strengths of this study is its large-scale population-based nationwide design. Additionally, the long-term monitoring from 2000 to 2013 made the analysis more reliable. However, the study has several limitations. First, the diagnoses were made using ICD-9 codes recorded in the NHIRD, but this database does not contain all types of data, such as laboratory parameters and genetic factors, which may help to postulate the mechanisms mediating the development of psychiatric disorders in patients with trichomoniasis. Secondly, although men were not included in the study, they potentially transmit the infection to women through sexual behavior and affect the treatment outcomes for women. Hence, sexual partners have to be treated to enhance the treatment efficiency. Thirdly, T. vaginalis infection is largely neglected because of ineffective screening protocols and a lack of public health attention [44]. The exact number of patients with trichomoniasis must be higher than those who seek medical attention, and thereby the cases of psychiatric disorders resulted from T. vaginalis infection must be underestimated.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, we provide the first evidence that T. vaginalis infection is associated with the risk of overall psychiatric disorders. The potential role of trichomoniasis in the devolvement of psychiatric disorders will highlight its clinical importance and public health impact. Clinicians should pay more attention to this neglected pathogen, which not only results in urogenital symptoms, but also leads to psychiatric disorders, especially in patients with refractory trichomoniasis.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1. ICD-9-CM codes used in this study.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Demographic characteristics of the study and control populations at the endpoint.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Years to the onset of psychiatric disorders.

Additional file 4: Table S4. Sexually transmitted infections of the trichomoniasis cohort.

Additional file 5: Table S5. The HIV status of all participants.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the National Defense Medical Center team for support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 107-2320-B-016-008-MY3) to KYH, Tri-Service General Hospital Songshan Branch, Taiwan (TSGHSB-C107-07) to HAL, and Tri-Service General Hospital, Taiwan (TSGH-C107-004; TSGH-C108-003) to WCC.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

HCL, KYH, WCC and TSC conceived the idea and wrote the first draft manuscript. HAL and RMC contributed to the manuscript. CHC and CHT contributed to statistical analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- aHR

adjusted hazard ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- HR

hazard ratio

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- IL

interleukin

- LHID 2000

Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000

- MTZ

metronidazole

- NHI

National Health Insurance

- NHIRD

National Health Insurance Research Database

- NTD

New Taiwan Dollars

- PTSD

post-traumatic stress disorder

- ASD

acute stress disorder

Contributor Information

Hsin-Chung Lin, Email: 1100sun@pchome.com.tw.

Kuo-Yang Huang, Email: cguhgy6934@gmail.com.

Chi-Hsiang Chung, Email: g694810042@gmail.com.

Hsin-An Lin, Email: shinean0928@gmail.com.

Rei-Min Chen, Email: j1885s@msn.com.

Chang-Huei Tsao, Email: changhuei@mail.ndmctsgh.edu.tw.

Wu-Chien Chien, Email: chienwu@ndmctsgh.edu.tw.

Tzong-Shi Chiueh, Email: drche0523@gmail.com.

References

- 1.WHO . Global incidence and prevalence of selected curable sexually transmitted infection. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gratrix J, Plitt S, Turnbull L, Smyczek P, Brandley J, Scarrott R, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis prevalence and correlates in women and men attending STI clinics in western Canada. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44:627–629. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leitsch D. Recent advances in the Trichomonas vaginalis field. F1000Res. 2016;5:162. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7594.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kissinger P. Trichomonas vaginalis: a review of epidemiologic, clinical and treatment issues. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:307. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1055-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukanyangezi MF, Sengpiel V, Manzi O, Tobin G, Rulisa S, Bienvenu E, et al. Screening for human papillomavirus, cervical cytological abnormalities and associated risk factors in HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in Rwanda. HIV Med. 2018;19:152–166. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hobbs MM, Sena AC. Modern diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:434–438. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1–137. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6404a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meites E. Trichomoniasis: the “neglected” sexually transmitted disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27:755–764. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Javanbakht M, Stirland A, Stahlman S, Smith LV, Chien M, Torres R, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with Trichomonas vaginalis infection among high-risk women in Los Angeles. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:804–807. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang PC, Hsu YC, Hsieh ML, Huang ST, Huang HC, Chen Y. A pilot study on Trichomonas vaginalis in women with recurrent urinary tract infections. Biomed J. 2016;39:289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein DJ, Phillips KA, Bolton D, Fulford KW, Sadler JZ, Kendler KS. What is a mental/psychiatric disorder? From DSM-IV to DSM-V. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1759–1765. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vigo DV, Kestel D, Pendakur K, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Disease burden and government spending on mental, neurological, and substance use disorders, and self-harm: cross-sectional, ecological study of health system response in the Americas. Lancet Public Health. 2018;4:e89–e96. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coughlin SS. Anxiety and depression: linkages with viral diseases. Public Health Rev. 2012;34:92. doi: 10.1007/BF03391675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fekadu A, Shibre T, Cleare AJ. Toxoplasmosis as a cause for behaviour disorders - overview of evidence and mechanisms. Folia Parasitol (Praha). 2010;57:105–113. doi: 10.14411/fp.2010.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Idro R, Kakooza-Mwesige A, Asea B, Ssebyala K, Bangirana P, Opoka RO, et al. Cerebral malaria is associated with long-term mental health disorders: a cross sectional survey of a long-term cohort. Malar J. 2016;15:184. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prasad KM, Watson AM, Dickerson FB, Yolken RH, Nimgaonkar VL. Exposure to herpes simplex virus type 1 and cognitive impairments in individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:1137–1148. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao J, Prandovszky E, Kannan G, Pletnikov MV, Dickerson F, Severance EG, et al. Toxoplasma gondii: biological parameters of the connection to schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:983–992. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuglewicz AJ, Piotrowski P, Stodolak A. Relationship between toxoplasmosis and schizophrenia: a review. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26:1031–1036. doi: 10.17219/acem/61435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown AS. Epidemiologic studies of exposure to prenatal infection and risk of schizophrenia and autism. Dev Neurobiol. 2012;72:1272–1276. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khandaker GM, Zimbron J, Lewis G, Jones PB. Prenatal maternal infection, neurodevelopment and adult schizophrenia: a systematic review of population-based studies. Psychol Med. 2013;43:239–257. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu TY, Majeed A, Kuo KN. An overview of the healthcare system in Taiwan. London J Prim Care (Abingdon). 2010;3:115–119. doi: 10.1080/17571472.2010.11493315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Hospital Association. American Medical Record Association. Health Care Financing Administration. National Center for Health Statistics ICD-9-CM coding and reporting official guidelines. J Am Med Rec Assoc. 1990;61(Suppl.):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmid G, Narcisi E, Mosure D, Secor WE, Higgins J, Moreno H. Prevalence of metronidazole-resistant Trichomonas vaginalis in a gynecology clinic. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:545–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crowell AL, Sanders-Lewis KA, Secor WE. In vitro metronidazole and tinidazole activities against metronidazole-resistant strains of Trichomonas vaginalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1407–1409. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.4.1407-1409.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ginocchio CC, Chapin K, Smith JS, Aslanzadeh J, Snook J, Hill CS, et al. Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis and coinfection with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the United States as determined by the Aptima Trichomonas vaginalis nucleic acid amplification assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2601–2608. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00748-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbai NS, Wand H, Ramjee G. Sexually transmitted infections in women participating in a biomedical intervention trial in Durban: prevalence, coinfections, and risk factors. J Sex Transm Dis. 2013;2013:358402. doi: 10.1155/2013/358402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis A, Dasgupta A, Goddard-Eckrich D, El-Bassel N. Trichomonas vaginalis and human immunodeficiency virus coinfection among women under community supervision: a call for expanded T. vaginalis screening. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43:617–622. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sperr M, Kundi M, Tursic V, Bristela M, Moritz A, Andrukhov O, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in periodontitis patients compared to the general Austrian population. J Periodontol. 2017 doi: 10.1902/jop.2017.170333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pompili M, Innamorati M, Forte A, Erbuto D, Lamis DA, Narcisi A, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and suicidal ideation in psoriasis, melanoma and allergic disorders. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2017;21:209–214. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2017.1301482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tzeng NS, Chang HA, Chung CH, Kao YC, Chang CC, Yeh HW, et al. Increased risk of psychiatric disorders in allergic diseases: a nationwide, population-based, cohort study. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:133. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaio MF, Lin PR, Liu JY, Yang KD. Generation of interleukin-8 from human monocytes in response to Trichomonas vaginalis stimulation. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3864–3870. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.3864-3870.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiori PL, Diaz N, Cocco AR, Rappelli P, Dessi D. Association of Trichomonas vaginalis with its symbiont Mycoplasma hominis synergistically upregulates the in vitro proinflammatory response of human monocytes. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:449–454. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-051006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson BL, Cosentino LA, Simhan HN, Hillier SL. Systemic immune response to Trichomonas vaginalis infection during pregnancy. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:392–396. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000243618.71908.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King C, Feldman J, Waithaka Y, Aban I, Hu J, Zhang S, et al. Sexual risk behaviors and sexually transmitted infection prevalence in an outpatient psychiatry clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:877–882. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31817bbc89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin H, Xu G, Tian H, Yang G, Wardenaar KJ, Schoevers RA. The prevalence, age-of-onset and the correlates of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders in the Tianjin Mental Health Survey (TJMHS) Psychol Med. 2018;48:473–487. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717001878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen MH, Su TP, Li CT, Chang WH, Chen TJ, Bai YM. Symptomatic menopausal transition increases the risk of new-onset depressive disorder in later life: a nationwide prospective cohort study in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bryant C, Judd FK, Hickey M. Anxiety during the menopausal transition: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;139:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu LY, Shen CC, Hung JH, Chen PM, Wen CH, Chiang YY, et al. Risk of psychiatric disorders following symptomatic menopausal transition: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2800. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mokdad AH, Forouzanfar MH, Daoud F, Mokdad AA, El Bcheraoui C, Moradi-Lakeh M, et al. Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors for young people’s health during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2016;387:2383–2401. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00648-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caron J, Fleury MJ, Perreault M, Crocker A, Tremblay J, Tousignant M, et al. Prevalence of psychological distress and mental disorders, and use of mental health services in the epidemiological catchment area of Montreal South-West. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:183. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klebanoff MA, Carey JC, Hauth JC, Hillier SL, Nugent RP, Thom EA, et al. Failure of metronidazole to prevent preterm delivery among pregnant women with asymptomatic Trichomonas vaginalis infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:487–493. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwebke JR, Barrientes FJ. Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis isolates with resistance to metronidazole and tinidazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:4209–4210. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00814-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donders GGG, Ruban K, Depuydt C, Bellen G, Vanden Broeck D, Jonckheere J, et al. Treatment attitudes for Belgian women with persistent Trichomonas vaginalis infection in the VlaResT study. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roth AM, Williams JA, Ly R, Curd K, Brooks D, Arno J, et al. Changing sexually transmitted infection screening protocol will result in improved case finding for Trichomonas vaginalis among high-risk female populations. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:398–400. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318203e3ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. ICD-9-CM codes used in this study.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Demographic characteristics of the study and control populations at the endpoint.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Years to the onset of psychiatric disorders.

Additional file 4: Table S4. Sexually transmitted infections of the trichomoniasis cohort.

Additional file 5: Table S5. The HIV status of all participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.