Abstract

Objective:

Patient-clinician communication (PCC) may generate or reduce healthcare disparities. This paper is based on the 2017 International Conference on Communication in Healthcare keynote address and reviews PCC literature as a research area for the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD).

Methods:

A narrative review of selected evidence on disparities in PCC experienced by race and ethnic minorities, associations between PCC and poor health outcomes, and patient and clinician factors related to PCC.

Results:

Factors associated with poor quality PCC on the patient level include being a member of racial/ethnic minority, having limited English proficiency, and low health and digital literacy; on the clinician level, being less culturally competent, lacking communication skills to facilitate shared decision-making, and holding unconscious biases. Recommendations include offering patient- and/or clinician- targeted interventions to guard against unconscious biases and improve PCC, screening patients for health literacy and English proficiency, integrating CC in performance processes, and leveraging health information technologies to address unconscious biases.

Conclusion:

Effective PCC is a pathway to decrease health disparities and promote health equity.

Practice Implications:

Standardized collection of social determinants of health in the Electronic Health Record is an important first step in promoting more effective PC.

Keywords: minority health, health disparities, patient-clinician communication

Introduction

The 2003 Institute of Medicine’s Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care summarized a legacy of unequal healthcare in the U.S.1 The publication highlighted disparities in outcomes for most leading causes of death and disability among African Americans compared to Whites.1 Limited data on the status of other racial/ethnic groups, a lack of understanding of the etiologic factors contributing to unequal care, and a sense of urgency to “do something” were compelling lessons from this report.1 Numerous factors were identified as contributing to unequal healthcare related to the patients, clinicians, and the healthcare system. Fundamental among these factors was patient-clinician communication (PCC) and its potential role in both generating and reducing healthcare disparities.1

PCC is defined as “the myriad of interpersonal communication activities that have intruded themselves on the examination room.”2 The focus on PCC comes amidst an emphasis on patient-centeredness as essential to improve healthcare.3 Researchers have documented associations between quality PCC and better health outcomes, medical adherence, and satisfaction with care.4–7 These results raise concerns given evidence of poor quality PCC experienced by racial/ethnic minorities and socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.8–10 The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) identified PCC as a priority topic under its Clinical and Health Services research program area.11 Through the lens of NIMHD’s research framework, we define PCC and review its association with health outcomes; review selected evidence of disparities in PCC and their patient and clinician related correlates; and provide recommendations to ensure quality PCC among these populations to reduce health disparities. This narrative review is based on a keynote address given at the 2017 International Conference on Communication in Healthcare.

NIMHD’s mission and guiding research framework

The Office of Minority Health Research transformed into the Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities in 2000 and then to NIMHD in 2010.12 Advancing, understanding, and improving health among the NIH-designated health disparity populations of minority racial/ethnic groups, populations of less privileged socioeconomic status (SES), underserved rural residents, and persons identifying as sexual gender minorities in the U.S. is NIMHD’s mandate.

The construct of race has been long ingrained in US history.13,14 Race has been the salient measure of inequalities in the US (compared to social class in other high-income countries). Despite the intersection of race and social class, studies in the US show that race is associated with inequalities above and beyond the contribution of social class. Race-attributed inequalities in the US transcend all aspects of life (e.g., education).13,14 In healthcare, a complex web of patient, clinician, and system factors interact to yield well-documented health inequalities among racial/ethnic minorities prompting policies to monitor and eliminate such inequalities.1 Race and ethnicity categories have been modified over the decades to reflect the evolving demography of the U.S.15 The reliability and validity of such measures have been subject of scientific debate.13

NIMHD adopts the standards used for federal data collection purposes, which include defining “Hispanic or Latino” ethnicity followed by five categories for race: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, White, and a multi-race category.16 Minority health research includes all topics relevant to these race/ethnic groups, independent of the presence of disparities, with Whites being a referent group. A full understanding of the meaning of the constructs captured by these categories is lacking and needs further disaggregation, particularly because of additional considerations (e.g., multi-race identity) that further complicate the race construct.14

Evaluation of health disparities among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations requires reliable measures that will assist the clinician. Information on annual household income, formal years of education, and occupation are usually absent from the medical record and infrequently ascertained by the clinical team.17,18 Type of health insurance often is the main proxy for SES but it is a limited metric. There is increased interest in life course SES that would require the clinician to ask about life growing up. Ultimately, total assets or wealth defines social class and this measure is rarely assessed in the clinical setting or even in most research studies. here is almost always some interaction between SES and race/ethnicity that needs to be considered in most clinical encounters and in many specific health issues.

Persons living in rural counties in the U.S. make up about 6% of the population and health disparities are usually related to less privileged SES and being from a minority race/ethnic group. However, there is increasing evidence of mortality disparities in rural populations for heart disease, cancer, accidents and stroke that merit more research on possible contributing factors such as geographic isolation and limited digital access that may affect .19 NIMHD declared sexual gender minorities (SGM) as a disparity population in part to promote needed research. Most of the research in SGM populations has focused on Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection and for progress in other areas there must be a systematic ascertainment of sexual orientation and gender identity in clinical settings and with research participants.

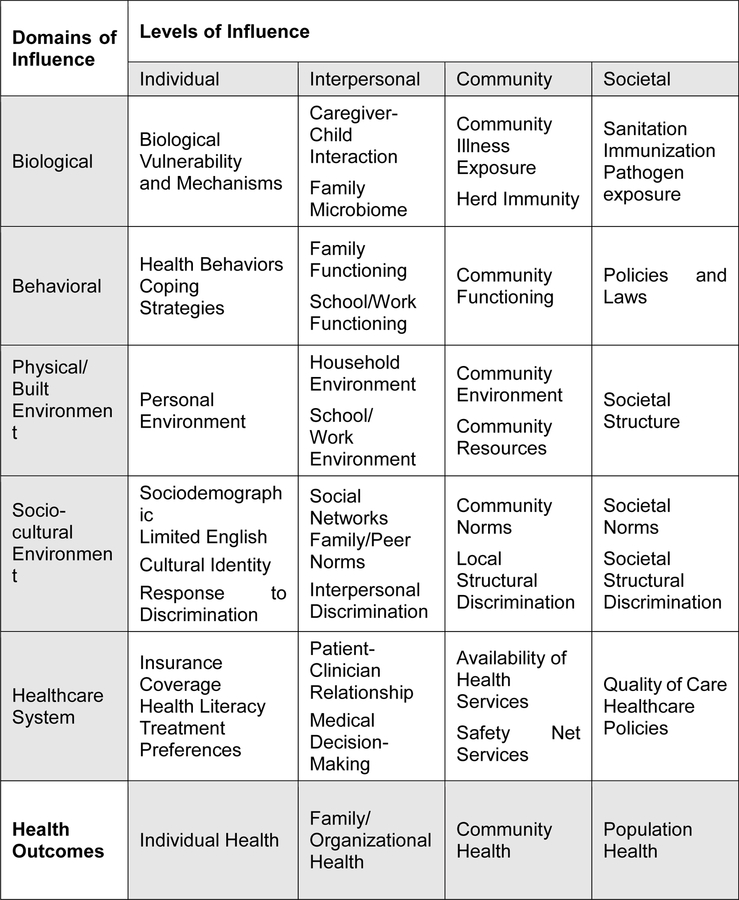

NIMHD’s mission is “to lead scientific research to improve minority health and reduce health disparities” through three scientific program areas: (a) clinical and health services research, (b) integrative biological and behavioral sciences, and (c) community health and population sciences.20,21 NIMHD’s research framework (Figure 1) reflects a conceptualization of factors relevant to the understanding of minority health and reduction of health disparities.22 The framework identifies five categories of determinants of health and four levels of influence within these domains. All these factors influence individuals in their interactions with the health care system for prevention, treatment, or disease management and represent opportunities to address minority health and reduce health disparities. We use NIMHD’s framework to review select individual- and interpersonal-level patient and clinician correlates of and recommendations to improve PCC under behavioral, social and cultural environment, and healthcare system domains of influence.

Figure 1:

NIMHD Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework22

PCC and its association with health outcomes

PCC encompasses all forms of communication (i.e., verbal, nonverbal, written) that occurs between patients and their physicians.2 Emphasis on PCC is grounded in a patient-centeredness approach to health and the ethical obligations of healthcare organizations.3,23 Patient-centered care “is respectful of and response to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensures that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”3 The ethical foundation of PCC is highlighted in professional codes and guidelines such as Code of Medical Ethics24 and Ethical Conduct for Health Care Institutions.25 Quality PCC rests on seven basic principles: “mutual respect, harmonized goals, a supportive environment, appropriate decision partners, the right information, transparency and full disclosure, and continuous learning.”26 In the context of caring for patients with cancer, six emotional and cognitive functions of communication were identified: “fostering patient-clinician relationship, exchanging information, responding to emotions, managing uncertainty, making decisions, and enabling patient self-management.”27

Effective communication between patients and their clinician has been consistently associated with improved clinical (e.g., blood pressure) and symptom-based (e.g., pain scores) health outcomes.28–33 In addition to its direct effect on health outcomes, PCC can indirectly improve health through proximal and intermediate outcomes. Examples of proximal outcomes include understanding, satisfaction, trust, and positive affect whereas examples of intermediate outcomes include medical adherence, self-care skills, and quality medical decision.4,34–36 However, more research is needed to establish the causal mechanistic relationship between PCC and health outcomes. Beyond individual-level outcomes, quality PCC is cost effective to healthcare system, conforms to ethical guidelines of medical practice, and reduces health disparities.27

Disparities in PCC and their correlates

To achieve equitable quality PCC, special attention is given to populations who are likely to experience “communication gaps,” defined as “instances of misunderstanding between a health care organization or professional and the individual or population they are serving.”3 Minorities and health disparity populations report lower quality PCC. early two decades ago, a Commonwealth Foundation survey asked whether patients had trouble understanding their doctor, had questions that they were not able to ask, or whether the physician did not listen to their concerns. Among Whites, 16% responded yes to one of the three questions, compared to 23% for African Americans, 33% for Latinos and 27% for Asians.37 Recent studies show that levels of poor communication experienced by racial/ethnic groups remain unchanged among African Americans, Latinos, and Asians compared to Whites using both self-report measures and objective assessments of the patient-clinician interaction (e.g., coded audio/video tapes of medical visits).8,38 Women, individuals with less education, and low SES also reported poor quality PCC, although the evidence is inconsistent.10,39

Disparities in PCC can be attributed to numerous factors related to patients and clinicians that interact together within the healthcare system to influence health outcomes. We highlight evidence on select patient (i.e., language proficiency, health and digital literacy) and clinician (i.e., cultural competency, communication skills, unconscious bias) factors that may contribute to poor PCC. These factors are interconnected in complex ways and rarely can be considered in isolation.

Patient factors

Race/ethnicity, SES, geographic location, and family background or country of origin are fundamental factors to consider in clinical care. A substantially higher proportion of minorities and health disparity populations have unmet needs that interfere with their abilities to care for themselves. For example minorities experience food (31.5% of African Americans and 35.4% of Latinos vs.18.2% of Whites) or housing (43.7% of African Americans and 47.3% of Latinos vs. 28.4% of Whites) insecurities.40 Similarly, 40.1% and 51.8% of persons with less than high school education (vs. 11% and 21.4% of college graduates) experience food and housing insecurities.40 Among immigrants, religion, cultural background, English language proficiency, acculturation level, immigrant generation, and documentation status have heightened relevance.41 Further, health disparity populations often exhibit factors associated with poor health such as low health literacy and/or limited English proficiency.42 Together, these factors underscore the unique challenges in communicating with minorities and health disparity populations.

Limited language proficiency (LEP):

Individuals with LEP are considered “communication-vulnerable populations.”23 With over 100 languages spoken in US households, 25 million persons not speaking English well at all, and 20% speaking a language other than English at home,43 clinicians in most areas of the US will encounter patients with LEP. Patients with L P status experience less patient-centered care, lower quality PCC,44 and report fewer healthcare visits.45

Low health literacy:

Patients can communicate with and understand their clinicians based, in large part, on health literacy. Limited health literacy means having problems with reading, calculations, oral communication, new learning, and carrying out medical instructions. According to the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), one in six and one in three adults in the US have poor literacy and numeracy skills, respectively, corresponding to a level 2 on a 5-point proficiency scale.46 Blacks and Latinos disproportionately have higher rates of poor literacy and numeracy skills,46 and this translates to less capacity “to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”47 In fact, PIAAC showed that individuals with low literacy and numeracy skills were four times more likely to report poor health compared to those with the highest proficiency levels.46

Among American adults 53% have intermediate and 22% have basic health literacy levels. However, race/ethnic minorities disproportionately had limited health literacy with 24% of Blacks, 41% of Latinos, 13% of Asians/Pacific Islanders, and 25% of American Indians/Alaska Natives compared to 9% of Whites.48ndividuals 65 years or older, those living under the poverty level, and persons with less than high school education also had higher proportions below basic health literacy.48 Limited health literacy is associated with poor PCC and negative health outcomes.49 For example, individuals with limited health literacy report poor receptive (physician to patient) and proactive (patient to physician) communication regardless of language spoken and language concordance.44 Similarly, limited health literacy was associated with a two-fold greater risk of high HbA1C and retinopathy among patients with diabetes, 1.5 risk of late stage presentation of cancer, greater risk of depression or anxiety, 1.5 risk of hospitalization, higher rates of poor self-rated health, and higher infant mortality (based on mother’s health literacy) and total mortality.50–53

Low digital literacy:

Recent shifts in the healthcare environment favor electronic communication and introduce digital literacy disparities related to information technologies. Increasingly, information technologies (e.g., web, mobile phones) serve as platforms for health information, patient-clinician interactions (e.g., patient portals), and interventions for disease prevention, treatment, and management (e.g., mobile apps and text messaging programs). Digital literacy is a multifaceted construct that encompasses technological and modality competencies in addition to cognitive capabilities.54 According to PIAAC, one in thr0.ee US adults demonstrate less than level 1 on a 3-point proficiency scale or no problem solving skills in information-rich environments, defined as “the capacity to access, interpret and analyze information found, transformed and communicated in digital environments.”46 Greater proportions of race/ethnic minorities, poor people and rural residents lack access to information technologies and have limited digital literacy, which is often associated with poor health literacy and health outcomes.55,56

Clinician factors

Cultural competency:

Race/Ethnic concordance is when both the patient and clinician share a common identity grounded in race/ethnic. A systematic review showed that racial/ethnic discordance was associated with poor PCC in 11 of 12 studies, while other reviews did not find that concordance was associated with PCC.57,58 Inconsistences in the association between race concordance and PCC may be attributed to different conceptualizations and measures of CC (e.g., clinician rating, communication satisfaction) and different patient settings in which PCC is assessed.57 Some studies identified plausible mechanisms through which racial concordance improves PCC such as perceived ethnic similarity between patient and clinician.59 A qualitative study of patient centeredness based on analyses of audiotaped visits in an internal medicine practice showed that race-concordant visits were 2.15 minutes longer and overall patients reported higher positive affect, satisfaction with care, and rated their physicians as having a more participatory decision-making style.60 Empirical research to evaluate the effect of race/ethnic concordance on PCC remains challenging.

As most race/ethnic minorities have more difficulty finding physicians who look like them, there is an emphasis on developing cultural competence. The term refers to “the set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies to support cross-cultural work.”61 Studies show that cultural competence is positively associated with clinician-related outcomes (e.g., knowledge, attitudes)62 but limited association with patient-related outcomes (e.g., adherence),63 or disparities in clinical outcomes.64 Regardless, caring for diverse patients requires integrating a level of knowledge about the specific populations, awareness of practices that may differ from established norms in the U.S. in everyday clinical practice.

Poor communication skills:

Over the past 20 years, clinical recommendations depended on a shared decision-making (SDM) model in patient-centered approaches to healthcare. Under SDM, patients, in consultation with their clinician, choose optimal diagnostic, treatment, or management regimens.65 Furthermore, the clinician’s “authority” assumes a secondary role whereas patients’ preferences are foremost in all considerations above any communal concerns for the patient’s family or for society in general. SDM has been associated with improved health outcomes and seems to be most helpful in “toss-up” decisions or when there are clear similar options on management decisions. SDM represents a perfect example where patient and clinician factors are hard to disentangle.

An underlying assumption of the SDM paradigm is that communication of risk, defined as a numerical proportion that a clinical event can occur over specific time, derived from population statistics and average demographic characteristics is accurately understood. However, a patient’s demographics (e.g., race/ethnicity, SES, gender, age)66 and other social determinants such as geographic residence, numeracy67, personal beliefs, preferences, and level of family involvement in health decisions68 may impact risk information processing and shared decision making especially when a patient is asymptomatic or is recommended for preventive services. Other factors such as subjective pessimistic or optimistic risk perceptions and biases and heuristics in decision making (e.g., overconfidence, confirmation bias) may also play roles.69,70,71.

On the other hand, clinicians’ communication skills such as negative or limited nonverbal communication, and personality traits such as condescending authoritarianism, may drive patients to adhere to the “good patient” role to avoid resentment or retribution from clinicians.72,73 Further, power imbalance in patient-clinician dynamics can also impede SDM. For example, African Americans with diabetes reported deference to a clinician’s authority and feelings of disempowerment in making decisions about their health.74 One approach in management of chronic disease is to promote the patient self-management as part of the therapeutic plan adding a level of responsibility in the SDM process. Finally, other structural factors that can impede SDM include inadequate consultation time, lack of coordination between clinicians, and not having a primary care clinician.72 Together, such barriers seem insurmountable for diverse patients and can exacerbate disparities.

Although clinician- and/or patient-targeted interventions to adopt SDM show promise,75 most SDM tools that have been developed and evaluated are biased towards mainstream White patients with limited understanding of their effects among culturally diverse patients and those with fewer years of formal education. A recent example of a patient decision aid that was shown to be effective in conjunction with navigation resulted in increased colon cancer screening rates within 6 months of the intervention among a vulnerable population.76 Other recommendations to improve SDM for dual-minority populations (e.g., based on race/ethnicity and sexual orientation) are being put forth.77

Unconscious Bias:

Perceptions of unfair treatment in social interactions in general are common for race/ethnic minorities in the .S. The Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Americans on race showed that, within healthcare settings, 12% of African Americans and 14% of Latinos, compared to 5% of Whites, reported being treated unfairly in the past 30 days because of their racial or ethnic background. he construct of unconscious bias has gained acceptability in the past decade among healthcare professionals and researchers. Unconscious bias refers to social stereotypes about certain groups of people that individuals form outside their own conscious awareness. All of us hold unconscious beliefs about various social and identity groups that in general favor men over women, Whites over non-Whites, youth over older, heterosexuals over sexual gender minorities, and physically able over disabled individuals.78

Although few empirical studies have evaluated the role of unconscious bias in providing health care, it is reasonable to hypothesize that unconscious bias may explain observed disparities in healthcare settings.79 For example, unconscious bias has been implicated as reason that Blacks and other minorities are less likely to be referred for and obtain procedures to evaluate and treat coronary artery disease,80 be referred for evaluation for kidney transplantation,81 and to be considered for surgical treatment of early lung cancer.82,83 In fact, the lower rate of prescription opioid overdose deaths among African Americans and Latinos compared to Whites has been explained by some as physician bias in not prescribing the medications because of concerns about abuse potential that may be driven by unconscious bias.84 Recent studies evaluating unconscious bias have used virtual patients in scenarios or clinical vignettes and two of nine studies found bias favoring treatment of Whites in emergency room settings.85

Recommendations to ensure quality PCC to reduce health disparities

The patient-clinician interaction is the main portal through which individuals engage with the health care system and thus represents an opportunity to address minority health and health disparities. In this section, we offer selected recommendations to address patient and clinician correlates of communication organized under three of the domains of influence – behavioral, socio-cultural environment, and healthcare system – included in NIMHD’s research framework. Noteworthy is that each recommendation addresses one or more PCC correlates and that recommendations that address each PCC correlate can spread over different domains of influence.

Behavioral domain

At the individual level, there is some evidence that unconscious bias may be modifiable. A longitudinal study of 3,547 students in 49 medical schools evaluated potential change in implicit bias towards African American patients. Analysis compared results from the Black-White Implicit Association Test (IAT) administered in the first six months of medical school to results obtained during the last six months. Multivariate models showed that over a four year period having completed the IAT itself, student’s self-assessment of skills in caring for Black patients, having heard negative comments about African Americans from clinical supervisors, and the nature of their clinical interactions with African American patients were significant factors in predicting IAT change.86 Although more empirical work is needed to further evaluate the role of IAT in healthcare, it is at a minimum an excellent tool to enhance awareness of potential bias in making clinical and staffing decisions.

At the interpersonal level, effective communication between clinicians and their patients is a learnable skill that requires continuous quality improvement maintenance. Many clinicians take good communication with patients for granted or as an inherent gift or associated with personality type. This sets up the potential to increase health disparities based on poor or ineffective communication leading to differential treatments, poor understanding of medication instructions and more adverse effects, inadequate access to care when needed, and misuse of diagnostic tests and services. The most vulnerable clinical situations or conditions may be the most susceptible to harm by ineffective communication. Interventions show promise in improving the quality of PCC. For example, in a randomized trial, patients with somatic symptoms assigned to general practitioners who offered explanations and addressed sensitive topics indirectly had better clinical outcomes (e.g., mental health, physical functioning) compared to patients assigned to general practitioners who used standard communication techniques.87 Similarly, an AskShareKnow programme proved feasible in training patients to ask three questions in a primary healthcare setting: “what are my options, what are the possible benefits and harms of those options, how likely are each of those benefits and harms to happen to me.”88 Finally, attempts to design and test interventions to improve digital literacy are underway.89 These interventions, upon proven effective, should be culturally tailored for minorities and health disparity populations to improve PCC.

Social and Cultural environment domain

Patients should be routinely screened for health literacy using validated measures such as the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine Short Form and Test of Functional Health Literacy of Adults.49,90 Similarly, ascertainment of LEP status should be systematically done in all health care systems. In the Census, the question used is simple: “How well do you speak English?” with response categories of “Very well, well, not well, or not at all.” All persons responding any answer other than “very well” is considered LEP by Census definition. Adding a second question about preference for language during clinical care augments the specificity of identifying LEP patients especially among those who respond speaking English “well”.91

Language concordant care should be the reference point and physicians should be tested, recognized, and compensated for having language skills used in clinical practice. Areas with higher rates of LEP patients should consider clinician’s language skills in hiring decisions. Language concordant care among Spanish speaking patients has been shown to be more important than health literacy in determining communication quality among LEP patients.44 In general, patients with LEP in language concordant encounters feel better, report less pain, have better health outlook, ask more questions, and report higher level of satisfaction in multiple settings.92 Recent analyses also showed that diabetes patients with concordant clinicians had better diabetes control with lower HbA1C levels than those with discordant clinicians within a staff model health maintenance organization.93–95 From a policy perspective, clinicians who are fluent in languages other than English should be placed in clinical settings where they care for LEP patients and this would enhance quality of care in these populations.

In the absence of concordance, professional interpreters should always be used given that ad hoc interpreters may result in errors and lower quality of care. Evidence from a hospital-based study showed that for 3071 LEP patients, interpreters were not used at all in 14% of admissions, which resulted in a significantly higher rate of 30-day re-admission (24.3% vs. 14.9%) when compared to interpreter use only at admission and discharge.96 In another study of 234 hospitalized patients, only 57% of patients used a professional interpreter on admission when interviewed by the physician and 37% used an interpreter with their nurse at any time of the hospitalization.97 Older patients and those speaking Chinese were more likely to have interpreters during the hospitalization.97

A clinical encounter with an interpreter becomes more complex with the involvement of a third person. Even with a professional interpreter, patients are less likely to ask questions, speak less frequently and in general have less opportunity to respond to clinician questions. Outpatient encounters take twice as long or as occurs most often, less conversation and interactions occur. Although interpretation from ad hoc untrained interpreters, staff or family or friends, is an improvement over no interpreter at all, non-professional interpreters are prone to more errors and result in lower quality of healthcare.98 Accordingly, it is imperative that in language discordant encounters the interpreter be professionally trained with standard quality control.

Sexual and gender issues are almost always a sensitive topic for most individuals regardless of cultural background. Appropriate codes for clinical questions and assessments will vary and often deviate from the clinician’s own perspective. It is precisely this challenge that needs to be continuously considered when caring for diverse patients. Similarly, all topics related to end of life care are almost always a sensitive and these are heightened in cross-cultural communication. Finally, for non-verbal communication, there are limited empirical data to support any broad recommendation on communication with diverse patients. Different styles of communication are, in part, defined by cultural norms and anchored in national origin, religion, or ethnic group. The amount of non-verbal communication relevant in the patient encounter may vary and be perceived as especially important in some cultures including the level of eye contact between clinician and patient, touching a patient other than during the physical examination, and the acceptable physical distance between persons during casual conversation varies by cultural background.

Despite a historical legacy of racism in the U.S. dating to the enslavement of people of African origin, most of the scientific research on racism and discrimination has focused on the personally mediated racism with self-reported perceived discrimination, which has been linked to mental and physical health status, blood pressure and heart rate. Much less research has been conducted evaluating the role of institutionalized/structural and internalized racism on health. Institutionalized racism is “differential access to the goods, services, and opportunities of society by race” whereas internalized racism is “acceptance by members of the stigmatized races of negative messages about their own abilities and intrinsic worth.99 Alleviating interwoven levels of racism requires national strategies to allocate resources that level the playing field for disadvantaged groups and address their unmet needs.

At the community and societal levels, several strategies are needed to ensure ownership, affordability, and skills necessary for use of health technologies are in place. Successful examples include the Medicaid cell phone program that provides free cell phone with text messaging and limited minutes and data plan.100 Furthermore, we recommend user-centered designs and cultural tailoring of digital interfaces to minorities and underserved populations, embedding tools to engage and sustain their engagement, and improve usability. Finally, additional efforts are needed to secure and protect electronic health information, a necessity to re-build trust between the medical community and minorities/underserved populations.101 Examples of trust-building strategies include adopting cultural tailoring approaches to healthcare and putting in place safeguards against racial/ethnic stereotyping and biased clinical decisions.102

Healthcare system

By diversifying clinicians to represent the communities that they serve, healthcare organizations can achieve better health outcomes.61 The proportion of medical school graduates in 2016–17 who are African Americans was 5.5% (n = 1069), Latinos were 5.1% (n = 982), and American Indian/Alaska Native was only 0.15% (n = 30).103 Evidence shows that underrepresented minority physicians are more likely to care for uninsured and Medicaid insured patients and to disproportionately care for concordant minority patients regardless of distance from their clinical practice.104 An analysis of medical school graduates from 2010–2012 showed that race/ethnic underrepresented students had greater intent to work in underserved communities after adjustment for gender, primary care career choice, and loan burden (63% of underrepresented minority graduates had a loan burden >$200,000).105 The divide in representativeness is large and unlikely to change significantly in the near future without directed programs and policy changes on medical school admissions to diversity the medical profession. Given the lack of diversity in clinicians, the requirement for cultural competence training is imperative.68,106 Color-blind and multicultural strategies hold promise to improve to improve communication with diverse patients, become aware of and overcome personal unconscious biases and institutional racial climate PCC.86,106,107

Health care systems should support increased access to language services through professional interpreters, videoconferencing and telephone language lines. Technological advances provide ready access to remotely based professional interpreters via video conferencing with tablets. In hospitals, dual head set telephones with access to language services have been shown to increase communication with clinicians and nursing staff especially for short interactions when in person interpreters are not available. advanced digital translators may also ameliorate the lack of concordant physicians and access to professional interpreters. Structural changes to healthcare system to allow sufficient consultation time, and efficient workflow and continuity of care are necessary to allow the use of methods to improve PCC (e.g., teach back).

Health information technologies afford opportunities to improve PCC through enhanced data collection, monitoring activities, and adherence to clinical protocols. For example, standardized measures of social determinants need to be routinely entered in the electronic medical records and used by clinicians in all clinical management decisions. Information on LEP should automatically assign interpreter services. Finally, implementation of clinical decision support systems can circumvent clinicians’ unconscious bias through checklists of required services based on standard protocols. Although these recommendations are aimed to improve the cognitive functions of PCC (e.g., exchanging information, making decisions), equally important are the emotional functions (e.g., managing uncertainties).108 Well-designed technology portals can simplify data collection, thus freeing clinicians’ time to devote to patients. Other non-technology-driven strategies that establish patient-clinician rapport include having a regular provider.

Conclusion

Although challenging, effective communication between clinicians and patients is essential to improved healthcare per numerous ethical and professional guidelines such as the American Medical Association’s Principles of Medical Ethics.23 Ensuring quality and equality of PCC requires ongoing intricate multi-level efforts. We consider that standardization of race and ethnic categories is an essential component of minority health and health disparities research and endorse the Census nomenclature and definitions as the starting point for specificity in the field.

We offer several recommendations to address root causes of poor PCC chief among them is assessing PCC in patient safety, clinician performance, and certification processes; delivering interventions aimed at clinicians and patients to improve PCC; and relying on health information technologies to automate data collection, aid in delivery of needed services such as interpreters, and subvert unconscious biases. Health equity has been a staple national goal but achieving it has proven to be challenging.109 The recommendations offered here are but a select few on a long road to alleviate health disparities.

Research wise, studies are needed to parse correlates of PCC among health disparity populations independent of race/ethnicity as well as the interplay of race/ethnicity with health disparities especially among understudied disparity populations (e.g., SGM). Finally, using uniform measures, improving the methodological quality of studies, and enrolling diverse patients in studies, particularly randomized clinical and behavioral trials, remain top priorities to resolve the inconclusiveness on best practices to improve PCC (and, subsequently, health outcomes) for diverse patients.

Table 1:

Recommendations for Patient-Clinician Communication in Health Disparity Populations

| Correlates of PCC | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Patient factors | |

| Limited language proficiency |

• Compensating clinicians’ language skills by added training • Making professional interpreters available in real time through videoconferencing or telephone • Screening for limited English proficiency and preferred language of clinical care |

| Low health literacy | • Adopting methods appropriate for limited health literacy individuals (e.g., teach back, icon arrays, illustrations) • Routine screening for health literacy |

| Low digital literacy | •Adopting user-centered designs and cultural tailoring of health information technology interfaces • Provide tutorials on access to patient portals • Encourage use of trusted proxy • Protecting and securing health electronic health information Interventions to increase ownership, affordability, and skills for health technologies |

| Clinician factors | |

| Cultural incompetency |

• Cultural competency training tailored to the local population • Diversifying medical school graduates |

| Communication skills | • Requiring training and quality improvement • Adopting efficient workflow and continuity of care |

| Unconscious bias | • Requiring implicit bias training |

| • Collecting data in electronic health records • Adopting clinical decision systems |

Highlights.

Effective communication between clinicians and patients improves quality of care

Need to have standardized collection of social determinants of health in EHR

Unconscious bias, cultural factors, literacy and language fluency must be considered

Acknowledgments

The effort of Dr. Sherine El-Toukhy was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health (K99MD011755). This research was supported in part by the Division of Intramural Research, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Eliseo J. Pérez-Stable, Office of the Director, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Division of Intramural Research, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Sherine El-Toukhy, Investigator, Division of Intramural Research, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, sherine.el-toukhy@nih.gov.

References

- 1.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare In: Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgoon M Strangers in a strange land: The Ph. D. in the land of the medical doctor. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 1992;11(1–2):101–106. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurtado M, Swift E, Corrigan J. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Institute of Medicine, Committee on the National Quality Report on Health Care Delivery 2001.

- 4.Zolnierek KBH, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Medical care 2009;47(8):826–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal 1995;152(9):1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. The Ochsner Journal 2010;10(1):38–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart M, Brown JB, Boon H, Galajda J, Meredith L, Sangster M. Evidence on patient-doctor communication. Cancer 1999; 3(1):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient–physician communication during medical visits. American journal of public health 2004;94(12):2084–2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Street RL Jr, Gordon H, Haidet P. Physicians’ communication and perceptions of patients: is it how they look, how they talk, or is it just the doctor? Social science & medicine 2007;65(3):586–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeVoe JE, Wallace LS, Fryer GE Jr. Measuring patients’ perceptions of communication with healthcare providers: do differences in demographic and socioeconomic characteristics matter? Health Expectations 2009;12(1):70–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Clinical and Health Services Research https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/programs/extramural/researchareas/clinical-research.html. Accessed March 15, 2018.

- 12.National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. NIMHD’s history in review https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/history/. Accessed March 15, 2018.

- 13.Travassos C, Williams DR. The concept and measurement of race and their relationship to public health: a review focused on Brazil and the United States. Cadernos de saúde pública 2004;20:660–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omi MA. The changing meaning of race, Smelser NJ, Wilson WJ, Mitchell F (Eds.), America becoming: Racial trends and their consequences, Vol. 1, National Academy Press, Washington DC, 2001, pp. 243–263. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pew Research Center: Social & Demographic Trends. What census calls us: A historical timeline 2015. (Accessed 16 March 2018) http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/06/ST_15.06.11_MultiRacial-Timeline.pdf

- 16.Office of Management and Budget. Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity 1997; https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/fedreg_1997standards. Accessed March 15, 2018.

- 17.Marmot MG, Stansfeld S, Patel C, et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. The Lancet 1991;337(8754):1387–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, et al. Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. Jama 2005;294(22):2879–2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia MC. Reducing potentially excess deaths from the five leading causes of death in the rural United States. MMWR Surveillance Summaries 66(2)(2017) 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Mission and vision https://nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/mission-vision.html. Accessed March 20, 2018.

- 21.National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. NIMHD minority health and health disparities research interest areas (Accessed 20 March 2018) https://nimhd.nih.gov/programs/extramural/research-areas/.

- 22.National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. NIMHD Research Framework https://nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/research-framework.html. Accessed March 16, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Association AM. An Ethical Force Program Consensus Report. Improving communication—improving care Chicago: American Medical Association 2006.

- 24.American Medical Association. AMA Code of Medical Ethics https://www.amaassn.org/delivering-care/ama-code-medical-ethics. Accessed April 2, 2018.

- 25.Association AH. AHA Management Advisory: Ethical Conduct for Health Care Institutions American Hospital Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paget L, Han P, Nedza S, et al. Patient-clinician communication: Basic principles and expectations Washington, DC: IOM Working Group Report, Institute of Medicine; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Epstein R, Street RL. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering National Cancer Institute, US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, Kossowsky J, Riess H. The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PloS one 2014;9(4):e94207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao JK, Anderson LA, Inui TS, Frankel RM. Communication interventions make a difference in conversations between physicians and patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Medical care 2007;45(4):340–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffin SJ, Kinmonth A-L, Veltman MW, Gillard S, Grant J, Stewart M. Effect on health-related outcomes of interventions to alter the interaction between patients and practitioners: a systematic review of trials. The Annals of Family Medicine 2004;2(6):595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orth JE, Stiles WB, Scherwitz L, Hennrikus D, Vallbona C. Patient exposition and provider explanation in routine interviews and hypertensive patients’ blood pressure control. Health Psychology 1987;6(1):29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fogarty LA, Curbow BA, Wingard JR, McDonnell K, Somerfield MR. Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? Journal of Clinical Oncology 1999;17(1):371–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Street RL Jr, Voigt B. Patient participation in deciding breast cancer treatment and subsequent quality of life. Medical Decision Making 1997;17(3):298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez LS, Schwartz JS, Freres D, Fraze T, Hornik RC. Patient–clinician information engagement increases treatment decision satisfaction among cancer patients through feeling of being informed. Patient education and counseling 2009;77(3):384–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson L, McCabe R. The effect of clinician-patient alliance and communication on treatment adherence in mental health care: a systematic review. BMC psychiatry 2012;12:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient education and counseling 2009;74(3):295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collins KS, Hughes DL, Doty MM, Ives BL, Edwards JN, Tenney K. Diverse communities, common concerns: assessing health care quality for minority Americans Commonwealth Fund New York; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palmer NR, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in patientprovider communication, quality-of-care ratings, and patient activation among long-term cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2014;32(36):4087–4094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spooner KK, Salemi JL, Salihu HM, Zoorob RJ. Disparities in perceived patient– provider communication quality in the United States: Trends and correlates. Patient education and counseling 2016;99(5):844–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Njai R, Siegel P, Yin S, Liao Y. Prevalence of Perceived Food and Housing Security-15 States, 2013. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2017;66(1):12–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kreps GL, Sparks L. Meeting the health literacy needs of immigrant populations. Patient education and counseling 2008;71(3):328–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sentell T, Braun KL. Low health literacy, limited English proficiency, and health status in Asians, Latinos, and other racial/ethnic groups in California. Journal of health communication 2012;17(sup3): 82–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.United States Census Bureau. Detailed languages spoken at home and ability to speak English for the population 5 years and over: 2009–2013. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- 44.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Perez-Stable EJ, Bibbins-Domingo K, Williams BA, Schillinger D. Unraveling the relationship between literacy, language proficiency, and patient–physician communication. Patient education and counseling 2009;75(3):398–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi L, Lebrun LA, Tsai J. The influence of English proficiency on access to care. Ethnicity & health 2009;14(6):625–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.The Ogranisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). United States - Country note - Survey of adult skills - First results 2013; http://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/Country%20note%20-%20United%20States.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- 47.Ratzan SC, Parker RM. Introduction. In: Selden CR, Zorn M, Ratzan SC, Parker RM, eds. National Library of Medicine Current Bibligoraphies in Medicine: Health Literacy Vol NLM Pub. No. CBM 2000–1. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kutner M, Greenburg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. NCES 2006–483. National Center for Education Statistics 2006.

- 49.Kindig DA, Panzer AM, Nielsen-Bohlman L. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeWalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes. Journal of general internal medicine 2004;19(12):1228–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sudore RL, Yaffe K, Satterfield S, et al. Limited literacy and mortality in the elderly: the health, aging, and body composition study. Journal of general internal medicine 2006;21(8):806–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. Jama 2002;288(4):475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gokhale MK, Rao SS, Garole VR. Infant mortality in India: use of maternal and child health services in relation to literacy status. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition 2002:138–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bawden D Origins and concepts of digital literacy. In: Lankshear C, Knobel M, eds. Digital literacies: Concepts, policies and practices Vol 30 Peter Lang; 2008:17–32. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bailey SC, O’conor R, Bojarski EA, et al. Literacy disparities in patient access and health‐related use of Internet and mobile technologies. Health Expectations 2015;18(6):3079–3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patel V, Barker W, Siminerio E Disparities in Individuals’ Access and Use of Health IT in 2014. In. Vol ONC Data Brief, no.34 Washington DC: ffice of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, et al. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities 2018;5(1):117–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sweeney CF, Zinner D, Rust G, Fryer GE. Race/Ethnicity and Health Care Communication. Medical care 2016;54(11):1005–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Street RL, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, Haidet P. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. The Annals of Family Medicine 2008;6(3):198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patientcentered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Annals of internal medicine 2003;139(11):907–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, . A proposed framework for integration of quality performance measures for health literacy, cultural competence, and language access services: Proceedings of a workshop In. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, et al. Cultural competency: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Medical care 2005;43(4):356–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lie DA, Lee-Rey E, Gomez A, Bereknyei S, Braddock CH. Does cultural competency training of health professionals improve patient outcomes? A systematic review and proposed algorithm for future research. Journal of general internal medicine 2011;26(3):317–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sequist TD, Fitzmaurice GM, Marshall R, et al. Cultural competency training and performance reports to improve diabetes care for black patients: a cluster randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine 2010;152(1):40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. Journal of general internal medicine 2012;27(10):1361–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim SE, Pérez-Stable EJ, Wong S, et al. Association between cancer risk perception and screening behavior among diverse women. Archives of Internal Medicine 2008;168(7):728–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wong ST, Pérez-Stable EJ, Kim SE, et al. Using visual displays to communicate risk of cancer to women from diverse race/ethnic backgrounds. Patient education and counseling 2012;87(3):327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hawley ST, Morris AM. Cultural challenges to engaging patients in shared decision making. Patient education and counseling 2017;100(1):18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ. Changing inaccurate perceptions of health risk: results from a randomized trial. Health psychology 1995;14(1):56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fischhoff B, Slovic P, Lichtenstein S. Knowing with certainty: The appropriateness of extreme confidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human perception and performance 1977;3(4):552–564. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nickerson RS. Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of general psychology 1998;2(2):175–220. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient education and counseling 2014;94(3):291–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Frosch DL, May SG, Rendle KA, Tietbohl C, Elwyn G. Authoritarian physicians and patients’ fear of being labeled ‘difficult’among key obstacles to shared decision making. Health Affairs 2012;31(5):1030–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Peek ME, Wilson SC, Gorawara-Bhat R, Odoms-Young A, Quinn MT, Chin MH. Barriers and facilitators to shared decision-making among African-Americans with diabetes. Journal of general internal medicine 2009;24(10):1135–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Légaré F, Ratté S, Stacey D, et al. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Reuland DS, Brenner AT, Hoffman R, et al. Effect of combined patient decision aid and patient navigation vs usual care for colorectal cancer screening in a vulnerable patient population: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA internal medicine 2017;177(7):967–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.DeMeester RH, Lopez FY, Moore JE, Cook SC, Chin MH. A model of organizational context and shared decision making: application to LGBT racial and ethnic minority patients. Journal of general internal medicine 2016;31(6):651–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Project Implicit. http://implicit.harvard.edu/). Accessed April 10, 2018.

- 79.Van Ryn M, Fu SS. Paved with good intentions: do public health and human service providers contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health? American journal of public health 2003;93(2):248–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Van Ryn M, Burgess D, Malat J, Griffin J. Physicians’ perceptions of patients’ social and behavioral characteristics and race disparities in treatment recommendations for men with coronary artery disease. American journal of public health 2006;96(2):351–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Furth SL, Hwang W, Neu AM, Fivush BA, Powe NR. Effects of patient compliance, parental education and race on nephrologists’ recommendations for kidney transplantation in children. American Journal of Transplantation 2003;3(1):28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cykert S, Dilworth-Anderson P, Monroe MH, et al. Factors associated with decisions to undergo surgery among patients with newly diagnosed early-stage lung cancer. Jama 2010;303(23):2368–2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bach PB, Cramer LD, Warren JL, Begg CB. Racial differences in the treatment of early-stage lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 1999;341(16):1198–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. Jama 2008;299(1):70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dehon E, Weiss N, Jones J, Faulconer W, Hinton E, Sterling S. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Physician Implicit Racial Bias on Clinical Decision Making. Academic Emergency Medicine 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 86.van Ryn M, Hardeman R, Phelan SM, et al. Medical school experiences associated with change in implicit racial bias among 3547 students: a medical student CHANGES study report. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2015;30(12):1748–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aiarzaguena JM, Grandes G, Gaminde I, Salazar A, SANchez A, AriNO J. A randomized controlled clinical trial of a psychosocial and communication intervention carried out by GPs for patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Psychological medicine 2007;37(2):283–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shepherd HL, Barratt A, Jones A, et al. Can consumers learn to ask three questions to improve shared decision making? A feasibility study of the ASK (AskShareKnow) Patient–Clinician Communication Model® intervention in a primary health‐care setting. Health Expectations 2016;19(5):1160–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Car J, Lang B, Colledge A, Ung C, Majeed A. Interventions for enhancing consumers’ online health literacy Cochrane Database Syst. Issue 6 (2011) Art. No. CD007092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Baker DW. The meaning and the measure of health literacy. Journal of general internal medicine 2006;21(8):878–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Karliner LS, Napoles-Springer AM, Schillinger D, Bibbins-Domingo K, Pérez- Stable EJ. Identification of limited English proficient patients in clinical care. Journal of general internal medicine 2008;23(10):1555–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nerenz DR, McFadden B, Ulmer C. Race, ethnicity, and language data: standardization for health care quality improvement National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fernandez A, Schillinger D, Warton EM, et al. Language barriers, physician-patient language concordance, and glycemic control among insured Latinos with diabetes: the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Journal of general internal medicine 2011;26(2):170–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Parker MM, Fernández A, Moffet HH, Grant RW, Torreblanca A, Karter AJ. Association of patient-physician language concordance and glycemic control for limited–english proficiency latinos with type 2 diabetes. JAMA internal medicine 2017;177(3):380–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fernández A, Quan J, Moffet H, Parker MM, Schillinger D, Karter AJ. Adherence to newly prescribed diabetes medications among insured Latino and White patients with diabetes. JAMA internal medicine 2017;177(3):371–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lindholm M, Hargraves JL, Ferguson WJ, Reed G. Professional language interpretation and inpatient length of stay and readmission rates. Journal of general internal medicine 2012;27(10):1294–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schenker Y, Pérez-Stable EJ, Nickleach D, Karliner LS. Patterns of interpreter use for hospitalized patients with limited English proficiency. Journal of general internal medicine 2011;26(7):712–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nápoles AM, Santoyo-Olsson J, Karliner LS, Gregorich SE, Pérez-Stable EJ. Inaccurate language interpretation and its clinical significance in the medical encounters of Spanish-speaking Latinos. Medical care 2015;53(11):940–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. American journal of public health 2000;90(8):1212–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.http://medicaidcellphone.com/ Accessed July 31, 2018.

- 101.Perloff RM, Bonder B, Ray GB, Ray EB, Siminoff LA. Doctor-patient communication, cultural competence, and minority health: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. American Behavioral Scientist 2006;49(6):835–852. [Google Scholar]

- 102.López L, Green AR, Tan-McGrory A, King RS, Betancourt JR. Bridging the digital divide in health care: the role of health information technology in addressing racial and ethnic disparities. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 2011;37(10):437–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.ASsociation of American Medical Colleges. Total US medical school graduates by race/ethnicity and sex, 2012–2013 through 2016–2017 https://www.aamc.org/download/321536/data/factstableb4.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- 104.Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. New England Journal of Medicine 1996;334(20):1305–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Garcia AN, Kuo T, Arangua L, Pérez-Stable EJ. Factors associated with medical school graduates’ intention to work with underserved populations: Policy implications for advancing workforce diversity. Academic Medicine 2018;93(1):82–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Betancourt JR, Green AR. Commentary: linking cultural competence training to improved health outcomes: perspectives from the field. Academic Medicine 2010;85(4):583–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.WT V, Antoinette S Color-Blind and Multicultural Strategies in Medical Settings. Social Issues and Policy Review 2017;11(1):124–158. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rathert C, Mittler JN, Banerjee S, McDaniel J. Patient-centered communication in the era of electronic health records: What does the evidence say? Patient education and counseling 2017;100(1):50–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.National Center for Health Statistics, Health, United States, 2015: with special feature on racial and ethnic health disparities. 2016, Report No.: 2016–1232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]