Abstract

One commonly practiced procedural step to reduce the risk of postoperative hematoma accumulation when performing cranioplasties is to place a closed negative-pressure subgaleal drain. We present a patient with sinking skin flap syndrome that underwent such a procedure and subsequently experienced immediate postoperative ascending transtentorial herniation and intracranial hemorrhage remote from the surgical site. On determining that the subgaleal drain was the responsible cause, it was immediate removed, and the patient had neurological recovery. Fewer than 30 cases of life-threatening subgaleal drain-related complications have been documented, and this is the first reported case of ascending herniation occurring after cranioplasty. This report illustrates the potential risks of subgaleal drainage, the importance of early recognition of this rare phenomenon and that intervention can be potentially life-saving.

Keywords: Ascending transtentorial herniation, cranioplasty, subgaleal drainage

Introduction

Cranioplasties are regularly performed neurosurgical procedures that can be associated with a variety of complications such as bone flap infection, seizures, and surgical site hematoma in almost a third of patients.[1] However, most complications are readily amenable to treatment and seldom fatal. One commonly practiced procedural step to reduce the risk of postoperative hematoma accumulation is to place a closed negative-pressure subgaleal drain. We present a patient with sinking skin flap syndrome (SSFS) that underwent a cranioplasty and subgaleal drainage. She subsequently experienced immediate postoperative ascending transtentorial herniation (ATH). Fewer than 30 cases of life-threatening subgaleal drain-related complications have been documented. This case illustrates the importance of early recognition of this rare phenomenon and intervention can be potentially life-saving.

Case Report

A 58-year-old female with a history of chronic rheumatic heart disease and atrial fibrillation was admitted for cranioplasty. She previously underwent a decompressive craniectomy for the management of her massive right middle and anterior cerebral artery infarction 6 months before. The ischemic stroke rendered the patient severely disabled with left hemiplegia and hemisensory loss. The patient also experienced chronic headache and nonspecific dull aching pain over the left side of the body that required gabapentin for partial relief. There was a large right fronto-parietal-temporal scalp concavity coinciding with a craniectomy skull defect of 25 cm × 20 cm [Figure 1a–c].

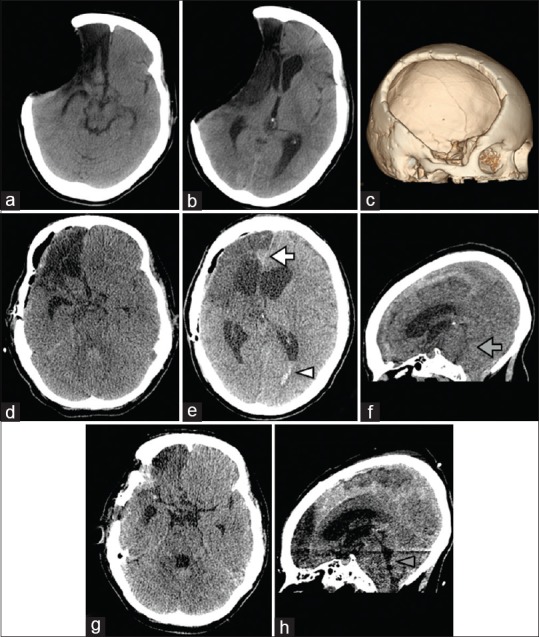

Figure 1.

Preoperative computed tomography scan revealing a large sunken craniectomy site with paradoxical herniation (a, b axial; c three-dimensional reconstruction). Immediate postcranioplasty scan showing interhemispheric acute subdural hematoma (white arrow), intraventricular hemorrhage (white arrowhead) and ascending transtentorial herniation with upward displacement of the cerebellar vermis (grey arrow) (d, e, axial; f midsagittal). One-day postoperative scan after subgaleal drain removal showing spontaneous resolution of transtentorial herniation (g, axial; h, midsagittal)

Cranioplasty using the patient's autologous bone flap was performed uneventfully and there was no intraoperative breach of the dura. Blood loss was 150 ml and the operation lasted for 100 minutes. During scalp wound closure, a single subgaleal suction drain was placed with vacuum applied as a routine measure. The drain was a negative pressure closed system with an inner diameter of 3.33 mm (Fr 10) and according to the manufacturer supplied medical device specifications, exerted a negative pressure 75 mmHg (10kPa). Within 1 hour after extubation the patient developed status epilepticus with bilateral eye deviation to the left. Pupil size was 3 mm bilaterally and reactive to light. There was fast atrial fibrillation (160 beats/min) and hypotension of 85/40 mmHg. At that juncture, the subgaleal drain output was <20 ml. The patient was mechanically ventilated and her seizures were controlled after administrating intravenous midazolam and phenytoin. A computed tomography (CT) brain scan showed an interhemispheric acute subdural hematoma, intraventricular hemorrhage within the left occipital horn of the lateral ventricle with obliteration of the quadrigeminal and superior cerebellar cisterns. There was also upward displacement of the vermis at the level of the incisura and flattening of the posterior third ventricle [Figure 1d–f]. The patient was diagnosed with ATH and the subgaleal drain was immediately removed. She was sedated for 24 hours and a CT brain performed the next day showed resolution of the ATH [Figure 1g, h]. The patient eventually recovered to her preoperative functional performance level with no further headaches and resolution of her limb numbness. There were no seizures and her phenytoin was weaned off a month after the cranioplasty.

Discussion

The term “SSFS” was first introduced in 1977 by Yamaura and is synonymous with the “syndrome of the trephined” that exclusively affects craniectomy patients.[2] The clinical presentation is protean ranging from chronic fatigue, headache, and dizziness to more disabling symptoms such as cognitive decline, seizures, visual disturbances, speech, and sensorimotor deficits.[3] The exact incidence is unknown, but from a prospective cohort study of patients with malignant middle cerebral artery syndrome who underwent hemicraniectomy 26% experienced SSFS 5 months after the procedure.[4] There are no diagnostic criteria, but a characteristic feature of SSFS is the reversibility of symptoms after cranioplasty and this has led to greater understanding of its possible pathophysiology.[5] The syndrome is believed to develop when atmospheric pressure exceeds intracranial pressure and in extreme cases can manifest as paradoxical herniation. The paradox lying in the fact that herniation occurs in the absence of intracranial hypertension. The consequences of atmospheric pressure exertion on a large craniectomy site can be far reaching. Not only is there direct brain compression but also a global disruption of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hydrodynamics with regional reductions in microarterial and venous outflow circulation.[3] Cranioplasty has been shown to elicit significant improvements in cerebral perfusion by xenon-133 CT; glucose metabolism by fluorodeoxyglucose-18 positron emission tomography; and systolic craniocaudal CSF flow velocities by dynamic phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging.[4,5,6] In spite of the benefits of cranioplasty, there have been sporadic reports of postoperative hemorrhagic stroke or diffuse cerebral edema (DCE or pseudohypoxic edema) attributed to the rapid increase in cerebral blood flow following reexpansion of fragile damaged brain tissue with impaired vascular autoregulation.[7,8,9,10] We suspect that the additional application of negative pressure drainage in our patient may have aggravated luxury hyperperfusion injury as exemplified by the presence of subdural and intraventricular hemorrhage.

From the year 2000–2017, 25 patients, including the present case, have been reported to develop severe cardiovascular changes, DCE, or intracranial hemorrhage attributable to negative-pressure drainage [Table 1]. Most patients had preceding SSFS and experienced drain-related complications after cranioplasty regardless of the presence of a CSF shunt. Two developed severe intracerebral hemorrhage secondary to tearing of the superior sagittal sinus and even intracranial aneurysm rupture after an otherwise uneventful craniotomy.[12,15] An overwhelming majority of these cases were fatal and neurological deterioration usually occurred within 3 hours after the operation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with postcranioplasty/craniotomy negative-suction subgaleal drainage-related complications

| Author, year | Patient age (years)/sex | Primary etiology | Procedure | CSF shunt (yes/no) | Interval duration to cranioplasty | Sinking scalp flap (yes/no) | Postprocedure time duration to deterioration | Postoperative presentation | Radiological findings | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van Roost et al.[11] | 32/male | TBI | Cranioplasty | Yes | NS | NS | NS | Coma; bilateral fixed and dilated pupils | NS | Death |

| Mohindra et al.[12] | 13 months/male | Traumatic leptomeningeal cyst | Craniotomy and dural repair | No | - | - | Immediate | Fresh blood in drain; cardiac arrest | Autopsy: Torn SSS | Death |

| Toshniwal et al.[13] | 45/female | Intracranial aneurysm | Craniotomy for clipping | No | - | - | Immediate | Bradycardia | - | No new deficit |

| Karamchandani et al., 2006[14] | 65/female | Intracranial aneurysm | Craniotomy for clipping | No | - | - | Immediate | Bradycardia; hypotension | - | No new deficit |

| Prabhakar et al.,[15] | 45/male | Intracranial aneurysm | Craniotomy for clipping | No | - | - | Immediate | Fresh blood in drain | Surgical exploration: rupture of incompletely clipped aneurysm | Death |

| Honeybul[16] | 22/male | TBI | Cranioplasty | No | 3 months | Yes | NS | Coma; bilateral dilated pupils; hypertension; tachycardia; seizure | DCE | Death |

| 16/male | TBI | Cranioplasty | Yes | 2 months | Yes | 3 h | Coma; bilateral dilated pupils; hypertension | DCE | Death | |

| 16/male | TBI | Cranioplasty | Yes | 2.5 months | Yes | 1 h | Coma; bilateral dilated pupils; hypertension | DCE | Death | |

| Roth et al.[17] | 3.5/male | Choroid plexus carcinoma | Cranioplasty | No | NS | No | Immediate | Bradycardia; hypotension | EDH | No new deficit |

| Zebian and Critchley[18] | 40/female | Ischemic stroke | Cranioplasty | Yes | 24 months | Yes | NS | Coma; bilateral dilated pupils; seizure | DCE; ICH | Death |

| Bhagat et al.[19] | 60/male | Intracranial aneurysm | Craniotomy for clipping | No | - | - | Immediate | Asystole | - | NS |

| Yadav et al.[20] | 1/male | Arachnoid cyst | Craniotomy for excision | No | - | - | Immediate | Asystole | IVH | Death |

| Broughton et al.[21] | NS | NS | Cranioplasty | No | NS | Yes | NS | Coma; bilateral dilated pupils; tachycardia | DCE | Death |

| Lee et al.[10] | 50/female | Aneurysmal SAH | Cranioplasty | NS | 2 months | Yes | Autologous | Seizure | DCE | NS |

| Sviri[22] | 22/male | TBI | Cranioplasty | No | 9 months | NS | Autologous | Coma; bilateral dilated pupils | DCE | Death |

| 14/male | TBI | Cranioplasty | Yes | 10 months | Yes | Autologous | Coma; bilateral dilated pupils | DCE | Death | |

| 28/male | TBI | Cranioplasty | Yes | 17 months | Yes | Methylmetharcylate | Coma; bilateral dilated pupils | DCE; ICH | Death | |

| 24/male | TBI | Cranioplasty | No | 3 months | Yes | Autologous | Coma; bilateral dilated pupils | DCE | Death | |

| Honeybul et al.[23] | 25/female | Ischemic stroke | Cranioplasty | No | 11 months | Yes | Titanium | Coma; bilateral dilated pupils | DCE | Death |

| 74/female | Ischemic stroke | Cranioplasty | No | 2 months | Yes | Autologous | Seizure | DCE; ICH | Death | |

| 41/female | Hemorrhagic stroke | Cranioplasty | No | 12 months | NS | Titanium | Seizure | DCE | Death | |

| Moon et al., 2016[9] | 22/male | TBI | Cranioplasty | Yes | 4 months | Yes | NS | Coma | DCE | Disability |

| Kaneshiro et al.[24] | 64/male | Hemorrhagic stroke | Cranioplasty | No | 1 month | Yes | Titanium | Coma; bilateral dilated pupils | DCE | Death |

| Shen et al.[25] | 51/male | TBI | Cranioplasty | No | 6 months | Yes | Autologous | Coma; bilateral dilated pupils; seizure | DCE; ICH | Death |

| Current | 58/female | Ischemic stroke | Cranioplasty | No | 6 months | Yes | Autologous | Seizure | DCE, ATH, IVH, SDH | Disability |

CSF – Cerebrospinal fluid; TBI – Traumatic brain injury; SAH – Subarachnoid hemorrhage; SSS – Superior sagittal sinus; NS – Not specified; PEEK – Polyether ether ketone; DCE – Diffuse cerebral edema; ICH – Intracerebral hemorrhage; IVH – Intraventricular hemorrhage; SDH – Subdural hematoma; ATH – Ascending transtentorial herniation

Ever since Georges Dieulafoy's 1873 seminal treatise on the merits of “pneumatic aspiration” in the management of wounds, the placement of drains has dominated surgical practice.[26] In his treatise, Dieulafoy cautioned that “the operator must be condemned who makes use of aspiration without understanding.”[26,27] The induction of acute intracranial hypotension by subgaleal drains can result in catastrophic outcomes.[11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,28,32] Our patient likely experienced ATH when vacuum suction to the supratentorial compartment was applied. The immediate clamping of the subgaleal drain with subsequent recovery of the patient's consciousness and stabilization of vital signs supports this theory. ATH, also known as reverse or upward coning, is the least frequently encountered of brain herniation syndromes. It is generally triggered by the abrupt supratentorial decompression of obstructive hydrocephalus secondary to cerebellar mass lesions in 65% of cases.[29] The precipitous plunge of supratentorial compartment pressure establishes a steep gradient that displaces the anterior lobe and vermis of the cerebellum superiorly through the tentorial incisura. Subsequent brainstem compression and compaction of the basal veins could cause life-threatening hemorrhagic venous infarction. Early signs of ATH include somnolence, cardiovascular collapse, arrhythmias (either bradycardia, atrial, or ventricular fibrillation), and pinpoint pupils.[2,3] A high-index of suspicion is required for this uncommon phenomenon and is potentially reversible if recognized early. This is the first documented case of ATH occurring after cranioplasty, but it is believed that previous cases of severe bradycardia and arterial hypotension encountered during subgaleal drain placement may have been due to the rostral shift of trigeminal or vagal brainstem nuclei.[13,14,17,19,32]

To demonstrate the degree of intracranial compartment pressure changes created, researchers have noted that intracranial pressure in the contralateral hemisphere can drop expeditiously to -20 mmHg at the moment of drain vacuum suction.[11] Furthermore, an experimental study of three commonly used closed drainage systems discovered that significantly high negative pressures, in excess of -150 mmHg and beyond physiological intra-arterial pressure, could be generated.[27] In contrast, there is little evidence to support the prophylactic use of closed suction drainage and its adoption is typically founded on anecdotal experience.[27,30,31] Only two retrospective cohort studies of supratentorial craniotomy patients were performed and both failed to demonstrate their efficacy in preventing postoperative epidural hematoma.[30,31]

This case illustrates the risks of routine negative-pressure subgaleal drainage during cranioplasty for patients with suspected SSFS. To avoid this complication, we recommend refraining from drain placement by conducting meticulous hemostasis, and if considered necessary, withholding vacuum application until after the cranioplasty. Alternatively, one may dispense with suction altogether and allow drainage to occur passively by gravity although the efficacy of such a measure remains unknown.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The preparation of this manuscript was supported by the Kwong Wah Hospital Clinical Research Center.

References

- 1.Zanaty M, Chalouhi N, Starke RM, Clark SW, Bovenzi CD, Saigh M, et al. Complications following cranioplasty: Incidence and predictors in 348 cases. J Neurosurg. 2015;123:182–8. doi: 10.3171/2014.9.JNS14405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamaura A, Makino H. Neurological deficits in the presence of the sinking skin flap following decompressive craniectomy. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1977;17:43–53. doi: 10.2176/nmc.17pt1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annan M, De Toffol B, Hommet C, Mondon K. Sinking skin flap syndrome (or syndrome of the trephined): A review. Br J Neurosurg. 2015;29:314–8. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2015.1012047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winkler PA, Stummer W, Linke R, Krishnan KG, Tatsch K. Influence of cranioplasty on postural blood flow regulation, cerebrovascular reserve capacity, and cerebral glucose metabolism. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:53–61. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.1.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dujovny M, Fernandez P, Alperin N, Betz W, Misra M, Mafee M, et al. Post-cranioplasty cerebrospinal fluid hydrodynamic changes: Magnetic resonance imaging quantitative analysis. Neurol Res. 1997;19:311–6. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1997.11740818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida K, Furuse M, Izawa A, Iizima N, Kuchiwaki H, Inao S, et al. Dynamics of cerebral blood flow and metabolism in patients with cranioplasty as evaluated by 133Xe CT and 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;61:166–71. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.2.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chitale R, Tjoumakaris S, Gonzalez F, Dumont AS, Rosenwasser RH, Jabbour P, et al. Infratentorial and supratentorial strokes after a cranioplasty. Neurologist. 2013;19:17–21. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31827c6bb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cecchi PC, Rizzo P, Campello M, Schwarz A. Haemorrhagic infarction after autologous cranioplasty in a patient with sinking flap syndrome. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2008;150:409–10. doi: 10.1007/s00701-007-1459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moon HJ, Park J, Kim SD, Lim DJ, Park JY. Multiple, sequential, remote intracranial hematomas following cranioplasty. J Korean Neurosurg. 2007;42:228–31. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee GS, Park SQ, Kim R, Cho SJ. Unexpected severe cerebral edema after cranioplasty: Case report and literature review. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2015;58:76–8. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2015.58.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Roost D, Thees C, Brenke C, Oppel F, Winkler PA, Schramm J, et al. Pseudohypoxic brain swelling: A newly defined complication after uneventful brain surgery, probably related to suction drainage. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:1315–26. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000093498.08913.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohindra S, Mukherjee KK, Chhabra R, Khosla VK. Subgaleal suction drain leading to fatal sagittal sinus haemorrhage. Br J Neurosurg. 2005;19:352–4. doi: 10.1080/02688690500305308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toshniwal GR, Bhagat H, Rath GP. Bradycardia following negative pressure suction of subgaleal drain during craniotomy closure. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2007;149:1077–9. doi: 10.1007/s00701-007-1246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karamchandani K, Chouhan RS, Bithal PK, Dash HH. Severe bradycardia and hypotension after connecting negative pressure to the subgaleal drain during craniotomy closure. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:608–10. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prabhakar H, Bithal PK, Chouhan RS, Dash HH. Rupture of intracranial aneurysm after partial clipping due to aspiration drainage system – A case report. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2008;19:1185–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honeybul S. Sudden death following cranioplasty: A complication of decompressive craniectomy for head injury. Br J Neurosurg. 2011;25:343–5. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2011.568643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roth J, Galeano E, Milla S, Hartmannsgruber MW, Weiner HL. Multiple epidural hematomas and hemodynamic collapse caused by a subgaleal drain and suction-induced intracranial hypotension: Case report. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:E271–5. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181fe6165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zebian B, Critchley G. Sudden death following cranioplasty: A complication of decompressive craniectomy for head injury. Br J Neurosurg. 2011;25:785–6. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2011.623801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhagat H, Mangal K, Jain A, Sinha R, Mallik V, Gupta SK, et al. Asystole following craniotomy closure: Yet another complication of negative-pressure suctioning of subgaleal drain. Indian J Anaesth. 2012;56:304–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.98787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yadav M, Nikhar SA, Kulkarni DK, Gopinath R. Cardiac arrest after connecting negative pressure to the subgaleal drain during craniotomy closure. Case Rep Anesthesiol 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/146870. 146870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broughton E, Pobereskin L, Whitfield PC. Seven years of cranioplasty in a regional neurosurgical centre. Br J Neurosurg. 2014;28:34–9. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2013.815319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sviri GE. Massive cerebral swelling immediately after cranioplasty, a fatal and unpredictable complication: Report of 4 cases. J Neurosurg. 2015;123:1188–93. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.JNS141152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Honeybul S, Damodaran O, Lind CR, Lee G. Malignant cerebral swelling following cranioplasty. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;29:3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaneshiro Y, Murata K, Yamauchi S, Urano Y. Fatal cerebral swelling immediately after cranioplasty: A case report. Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:156. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_137_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen L, Zhou Y, Xu J, Su Z. Malignant cerebral swelling after a cranioplasty: A case report and literature review. World Neurosurg. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.07.125. pii: S1878-8750(17) 31830-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dieulafoy G. In: Treatise on the Aspiration of Morbid Liquids, Medico-Surgical Methods for Diagnosis and Treatment. Masson G, editor. Paris: Librairie de L’Academie de Medicine; 1873. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grobmyer SR, Graham D, Brennan MF, Coit D. High-pressure gradients generated by closed-suction surgical drainage systems. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2002;3:245–9. doi: 10.1089/109629602761624207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demetriades AK. Negative pressure suction from subgaleal drainage: Bradycardia and decreased consciousness. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2008;150:1111. doi: 10.1007/s00701-008-0028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cuneo RA, Caronna JJ, Pitts L, Townsend J, Winestock DP. Upward transtentorial herniation: Seven cases and a literature review. Arch Neurol. 1979;36:618–23. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1979.00500460052006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi SY, Yoon SM, Yoo CJ, Park CW, Kim YB, Kim WK, et al. Necessity of surgical site closed suction drain for pterional craniotomy. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg. 2015;17:194–202. doi: 10.7461/jcen.2015.17.3.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guangming Z, Huancong Z, Wenjing Z, Guoqiang C, Xiaosong W. Should epidural drain be recommended after supratentorial craniotomy for epileptic patients? Surg Neurol. 2009;72:138–41. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernández-Palazón J, Tortosa JA, Sánchez-Bautista S, Martínez-Lage JF, Pérez-Flores D. Cardiovascular disturbances caused by extradural negative pressure drainage systems after intracranial surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:599–601. doi: 10.1093/bja/80.5.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]