Abstract

Background:

Subjective cognitive complaint is a sensitive marker of decline.

Objective:

This study aimed to (1) examine reliability of subjective cognitive complaint using the Cognitive Function Instrument (CFI), and (2) assess the utility of the CFI to detect cognitive decline in non-demented elders.

Methods:

Data from a four-year longitudinal study at multiple Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS) sites were extracted (n = 644). Of these, 497 had Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) global scores of 0 and 147 had a CDR of 0.5. Mean age and education were 79.5±3.6 and 15.0±3.1 years, respectively. All participants and their study partners completed the subject and study partner CFI yearly. Modified Mini-Mental State Exam (mMMSE) and Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT) were administered. Scores below the predetermined cut-off scores on either measure at annual visit were triggers for a full diagnostic evaluation. Cognitive decline was defined by the absence/presence of the trigger.

Results:

Three-month test retest reliability showed that inter-class coefficients for subject and study partner CFI were 0.76 and 0.78, respectively. Generalized estimating equation method revealed that both subject and study partner CFI change scores and scores from previous year were sensitive to cognitive decline in the CDR 0 group (p < 0.05). In the CDR 0.5 group, only the study partner CFI change score predicted cognitive decline (p < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Cognitive decline was predicted differentially by CDR level with subject CFI scores providing the best prediction for those with CDR 0 while study partner CFI predicted best for those at CDR 0.5.

Keywords: Cognitive decline, healthy older adults, non-demented elders, subjective cognitive complaints

INTRODUCTION

Emerging data in clinical studies suggest that subjective report of cognitive change in everyday life is a sensitive marker of decline, even at the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1–7]. Accordingly, as part of the Prevention Instrument (PI) project, the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS) has developed the Cognitive Function Instrument (CFI) to determine if subjective report of cognitive change can be used as an outcome measure in AD clinical trials [8]. The CFI is a 14-item assessment of cognitive status, which is completed by participants. There is also a study partner version because even mild cognitive impairment can challenge the ability of the subject to recall or compare current performance with past performance. One purpose of the PI project was to determine the utility of the CFI in clinical trials focused on prevention of AD.

Baseline report from the ADCS PI project suggested that both subject and study partner CFI scores were associated with cognitive performance in a cohort of non-demented older adults, supporting the utility of CFI as an indicator of cognitive impairment in healthy elderly [9]. Subsequently, other researchers investigated the CFI data longitudinally in a subset of asymptomatic subjects (those who obtained a global Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) of 0) and found that both subject and study partner CFI were associated with cognitive decline over time [10]. However, clinical characterization also includes categories such as mild cognitive impairment and prodromal dementia. Thus, it is important to address subjective complaint in older adults who may begin with some impairment or those who presumably will progress to some impairment (i.e., subjects who obtained a global CDR of 0.5). In addition, previous studies on CFI defined cognitive decline as an absolute change or subtle decline in cognitive tests, as opposed to a critical clinical change (i.e., a “cognitive evaluation trigger”).

In the current study, we aimed to (1) establish three-month test-retest reliability for the subject and study partner CFI, and (2) examine the utility of CFI to detect cognitive decline in non-demented older adults. To the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated test-retest reliability of CFI. While our study cohort overlapped with that of the previous CFI studies [9, 10], this is the first study using “cognitive evaluation trigger” as an outcome measure. This work allowed us to examine the degree to which subjective complaints is related to clinically observable declines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

A total of 644 older adults were recruited for the AD simulated primary prevention trial of the ADCS PI study. The research design and procedure for the ADCS PI study have been explained in depth elsewhere [8]. In brief, the ADCS instrument committee conducted a four-year PI study at 39 ADCS sites across the United States to evaluate the feasibility and utility of in-home completion of new experimental measures in prevention trials for AD. Each ADCS site included at least 16 subjects, 20% of whom were minority individuals. At baseline, all participants were non-demented, 75 years or older, in good physical and mental health, and not taking any exclusionary medications (e.g., antipsychotic drugs). Participants were also required to have a study partner who was able to provide information about their daily functioning. All participants received assessments associated with the PI study at screening, baseline, and annually for four years. A full description of the assessments has been described in detail in other published articles [9, 11–16]. The current study included participants with a CDR Global score of 0 and 0.5 at baseline [8]. Institutional review board approval was obtained at each site. All participants provided signed informed consent.

Measures

Modified Mini-Mental State Exam (mMMSE) [17], Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT) [18], and CDR [19] were administered at screening as subject-selection-criteria [8]. Participants met the selection criteria if they performed above the cut-off scores on all three tests. mMMSE is an assessment of global cognitive function, including cognitive domains of orientation, language, verbal recall, recognition, and constructional ability. mMMSE scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better cognitive test performance. Cut-off scores for the mMMSE were 88 or above for subjects with more than 8 years of education, and 80 or above for subjects with 0 to 8 years of education [8]. These cut off score have been used extensively in earlier literature to identify individuals with dementia [20, 21].

FCSRT is a 16-item word list with visual and auditory presentation, including three trials of free plus cued recall. FCSRT score ranges from 0 to 48, with higher scores indicating better cognitive test performance. Cut-off score for FCSRT was 45 or above [8]. This cutoff point has been empirically tested and shown to have high discriminative validity to distinguish individuals with and without dementia in a criterion sample [22].

CDR is a semi-structured global dementia measurement rated by a clinician who was blind to CFI scores following interviews with subject and study partner. It assesses daily functioning in the areas of memory, orientation, judgment, hobbies, community affairs, and personal care. CDR Sum of Boxes (SOB) is a simple aggregate of scores in the six clinical domains. CDR-SOB scores range from 0 to 18, with higher scores indicating worse clinical status. CDR Global scores range from 0 to 3 with: 0 = intact cognition, 0.5 = mild cognitive impairment, 1 = mild dementia, 2 = moderate dementia, and 3 = severe dementia. The score is generated using an algorithm weighted toward memory.

Objective cognitive function was measured yearly by the predetermined cut-off scores for mMMSE and FCSRT. These cut-off scores have been extensively used in the existing literature to differentiate older adults with cognitive impairments [21–23]. At each annual visit, scores below the cut-off scores on either the mMMSE or FCSRT were triggers for a full diagnostic evaluation (“cognitive evaluation trigger”). Cognitive decline in this study was defined by the absence/presence of the trigger.

Subjective cognitive function was measured by the subject (see Table 1) and study partner CFI (see Table 2) at screening and annually. At the screening visit, CFI forms were distributed to participants and their study partners to be completed at home and mailed back to the site. Prior to each annual evaluation, the CFI was mailed separately to the subjects and study partners, who were asked to complete the instruments at home independently and mail them back to the site. For half of the subjects and study partners, the mail-in screening instrument was sent at three months following baseline to evaluate its test-retest reliability. The instrument was derived from a standard clinical dementia assessment covering changes in cognitive and functional abilities over the previous year with yes/no/maybe as available responses to 14 questions. For questions about driving, handling finances, and work performance, an additional option of not applicable was available. Total scores on the instrument range from 0 to 14 (Yes = 1, No = 0, and Maybe = 0.5), with higher scores indicating greater subjective cognitive complaints.

Table 1.

Subject CFI [10]

| Answer all questions with reference to one year ago. | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Compared to one year ago, do you feel that your memory has declined substantially? |

| 2. | Do others tell you that you tend to repeat questions over and over? |

| 3. | Have you been misplacing things more often? |

| 4. | Do you find that lately you are relying more on written reminders (e.g., shopping lists, calendars)? |

| 5. | Do you need more help from others to remember appointments, family occasions or holidays? |

| 6. | Do you have more trouble recalling names, finding the right word, or completing sentences? |

| 7. | Do you have more trouble driving (e.g., do you drive more slowly, have more trouble at night, tend to get lost, have accidents)? |

| 8. | Compared to one year ago, do you have more difficulty managing money (e.g., paying bills, calculating change, completing tax forms)? |

| 9. | Are you less involved in social activities? |

| 10. | Has your work performance (paid or volunteer) declined significantly compared to one year ago? |

| 11. | Do you have more trouble following the news, or the plots of books, movies or TV shows, compared to one year ago? |

| 12. | Are there any activities (e.g., hobbies, such as card games, crafts) that are substantially more difficult for you now compared to one year ago? |

| 13. | Are you more likely to become disorientated, or get lost, for example when traveling to another city? |

| 14. | Do you have more difficulty using household appliances (such as the washing machine, VCR or computer)? |

Table 2.

Study partner CFI [10]

| Answer all questions with reference to one year ago. | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Do you feel the subject has had a significant decline in memory compared to one year ago? |

| 2. | Do the subject tend to repeat questions over and over? |

| 3. | Has the subject been misplacing things more often? |

| 4. | Does it seem to you that lately the subject is relying more on written reminders (e.g., shopping lists, calendars)? |

| 5. | Does the subject need more help from others to remember appointments, family occasions or holidays? |

| 6. | Does the subject have more trouble recalling names, finding the right word, or completing sentences? |

| 7. | Is the subject having more trouble driving (e.g., drive more slowly, have more trouble at night, tend to get lost, have accidents)? |

| 8. | Compared to one year ago, is the subject having more difficulty managing money (e.g., paying bills, calculating change, completing tax forms)? |

| 9. | Is the subject less involved in social activities? |

| 10. | Do you believe, based on your own observations or comments from the subject’s co-workers, that the subject’s work performance (paid or volunteer) has declined significantly, compared to one year ago? |

| 11. | Does the subject have more trouble following the news, or the plots of books, movies or TV shows, compared to one year ago? |

| 12. | Are there any activities (e.g., hobbies, such as card games, crafts) that are substantially more difficult for the subject now compared to one year ago? |

| 13. | Is the subject more likely to become disorientated, or get lost, for example when traveling to another city? |

| 14. | Does the subject have more difficulty usin2 household appliances (such as the washing machine, VCR or computer)? |

Statistics

Using t tests and chi-square tests, demographic and clinical variables were compared between subjects with CDR Global 0 and those with CDR Global 0.5. We also compared the two CDR groups by cognitive and retention status: cognitively stable versus cognitive decline groups (cognitive decline group = subjects who had a “cognitive evaluation trigger” at any time point) and “completers” versus “non-completers”(non-completer = subjects who did not complete all four annual visits). Inter-class coefficients (ICC) were calculated to assess three-month test-retest reliability for subject and study partner CFI. Ten thousand bootstrap samples were generated to compare the ICCs between subject and study partner CFI. Generalized estimating equation (GEE) method was used to examine the extent to which CFI score predicted cognitive decline as measured by the presence and absence of a “cognitive evaluation trigger,” while controlling for other variables and accounting for the within-subject correlation. To examine the short-term prediction ability of the CFI, the CFI score from the previous year and the change in CFI score from current year to previous year were used as independent variables. mMMSE and FCSRT scores in the previous year, CDR Global score and age at baseline, ethnicity, and subjects’ primary language were used as covariates in the GEE analysis. To examine the long-term prediction ability of the CFI, the CFI score from two years ago and the change in CFI score from current year to two-year-ago were used as independent variables. mMMSE and FCSRT scores from two years prior, CDR Global score and age at baseline, ethnicity, and subjects’ primary language were used as covariates in the GEE analysis. Statistical significance was defined a priori at p = 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographics

At baseline, 644 healthy non-demented subjects and study partners completed the CFI. Table 3 summarizes the demographic and clinical variables of the entire study cohort by baseline CDR Global score (0 versus 0.5). Compared to subjects with CDR 0, those with CDR 0.5 were more likely to be older and less educated. Subjects with CDR 0.5 also reported more depressive symptoms on Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), scored higher on both subject and study partner CFI at baseline, and performed worse on cognitive measures (i.e., mMMSE and FCSRT) than those with CDR 0. In both CDR 0 and 0.5 groups, the cognitive decline group tended to be older and less educated compared to the cognitively stable group. Subjects in the cognitive decline group also reported more depressive symptoms on the GDS, scored higher on both subject and study partner CFI at baseline, and performed worse on the cognitive measures than cognitively stable group. Compared to completers in both CDR groups, non-completers tended to be older and less educated. Non-completers also reported more depressive symptoms on the GDS, scored higher on both subject and study partner CFI at baseline, and performed worse on the cognitive measures than completers.

Table 3.

Comparisons of demographic and clinical variables between subjects with baseline CDR Global score of 0 and 0.5

| Variables | All sample | Baseline CDR |

Baseline CDR 0 |

Baseline CDR 0.5 |

Baseline CDR 0 |

Baseline CDR 0.5 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.5 | Cognitive stable | Cognitive decline | Cognitive stable | Cognitive decline | Non-completers | Completers | Non-completers | Completers | ||

| Subject, n | 644 | 497 | 147 | 435 | 62 | 101 | 46 | 186 | 311 | 67 | 80 |

| Age, M (SD) | 79.5 (3.6) | 79.4 (3.6) | 79.8 (3.6) | 79.3 (3.6) | 80.2 (3.9) | 79.3 (3.5) | 81.0 (3.6)* | 80.0 (4.2) | 79.0 (3.2)* | 80.3 (4.0) | 79.4 (3.2) |

| Male, % | 41.8 | 39.6 | 49.0* | 40.2 | 35.5 | 51.5 | 43.5 | 37.1 | 41.2 | 55.2 | 43.8 |

| White, % | 77.2 | 77.3 | 76.9 | 79.5 | 61.3* | 76.2 | 78.3 | 71.5 | 80.7* | 68.7 | 83.8* |

| Married, % | 55.9 | 54.3 | 61.2 | 55.2 | 48.4 | 63.4 | 56.5 | 45.7 | 59.5* | 68.7 | 55 |

| Education (y), M (SD) | 15.0(3.1) | 15.0 (3.0) | 14.8 (3.4) | 15.2 (2.9) | 14.0 (3.4)* | 14.8 (3.5) | 14.7 (3.1) | 14.5 (3.0) | 15.3 (2.9)* | 14.1 (3.6) | 15.4 (3.1)* |

| Living with study partners, % | 49.1 | 47.5 | 54.4 | 46.9 | 51.6 | 56.4 | 50 | 41.9 | 50.8 | 62.7 | 47.5 |

| Subject’s CFI at baseline | 2.4 (2.3) | 2.0 (1.9) | 3.8 (2.9)* | 1.9 (1.8) | 2.7 (2.3)* | 3.4 (2.8) | 4.5 (3.1)* | 2.4 (2.1) | 1.8 (1.8)* | 4.5 (3.3) | 3.2 (2.4)* |

| Study partner’s CFI at baseline | 1.5 (2.1) | 1.0 (0.2) | 3.0 (2.9)* | 0.9 (1.4) | 1.6 (2.1)* | 2.8 (2.8) | 3.5 (2.9) | 1.1 (1.6) | 1.0 (1.5) | 3.6 (3.2) | 2.5 (2.5)* |

| CDR-SOB, M (SD) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.5)* | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2)* | 1.0 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.5)* | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.6) | 0.9 (0.5)* |

| mMMSE, M (SD) | 95.3 (3.7) | 95.6 (3.5) | 94.1 (3.9)* | 96.1 (3.2) | 92.2 (3.8)* | 94.7 (3.9) | 92.8 (3.8)* | 94.8 (3.8) | 96.1 (3.2)* | 93.0 (4.4) | 94.9 (3.3) |

| FSCRT, M (SD) | 47.8 (0.5) | 47.8 (0.5) | 47.7 (0.7)* | 47.9 (0.4) | 47.6 (0.8)* | 47.8 (0.5) | 47.5 (0.9)* | 47.8 (0.6) | 47.9 (0.4) | 47.6 (0.8) | 47.8 (0.5) |

| GDS, M (SD) | 1.5 (2.0) | 1.3 (1.8) | 2.4 (2.4)* | 1.2 (1.8) | 1.6 (2.3) | 2.3 (2.3) | 2.7 (2.7) | 1.6 (2.0) | 1.1 (1.7)* | 2.9 (2.4) | 2.0 (2.4)* |

p ≤ 0.05.

Three-month test-retest reliability

The ICC was used to establish three-month test-retest reliability for both subject and study partner CFI. ICC for the subject’s and study partner’s reports were 0.76 (95% confidence interval (CI) = [0.71, 0.80]) and 0.78 (95% CI = [0.73, 0.82]), respectively, indicating a high reliability. Among those with CDR 0, ICC for the subject’s and study partner’s reports were 0.75 (95% CI = [0.69, 0.80] and 0.65 (95% CI = [0.59, 0.72]), respectively. Among those with CDR 0.5, ICC for the subject’s and study partner’s reports were 0.72 (95% CI = [0.59, 0.81] and 0.80 (95% CI = [0.70, 0.87]), respectively. Comparison of ICC between subject and study partner CFI showed that ICC was significantly higher for study partners compared to subjects for the entire sample (p < 0.0001) and in subjects with CDR 0.5 (p < 0.0001). However, ICC was significantly lower for study partners compared to subjects in those with CDR 0 (p < 0.0001).

The relationship between CFI and cognitive decline

The relationship between CFI and cognitive decline over the four-year period was estimated using GEE models, while accounting for other variables and controlling for the within-subject correlation. The models were estimated separately for the subject and study partner CFI. Table 4 shows that subject and study partner CFI from the previous year as well as one-year change in subject and study partner CFI significantly predicted cognitive decline at the current year in the entire sample (p < 0.05). Similar results were found in those with CDR 0. For those with CDR 0.5 however, only one-year change in study partner CFI significantly predicted cognitive decline at the current year (p < 0.05). Subject and study partner CFI from the previous year as well as one-year change in subject CFI were not associated with cognitive decline at the current year. Table 5 shows that subject and study partner CFI from two years ago as well as the two-year change in subject and study partner CFI significantly predicted cognitive decline at the current year in the entire sample (p < 0.05). Results were similar in those with CDR 0. For those with CDR 0.5; however, only two-year change in study partner CFI significantly predicted cognitive decline at the current year (p < 0.05).

Table 4.

The short term (one year) predictability of subject and study partner CFI by baseline CDR

| Subject | All Sample |

CDR = 0 |

CDR = 0.5 |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | p | Estimate | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | p | Estimate | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | p | ||||

| CFI in the previous year | 0.227 | 0.131 | 0.323 | 1.255 | <0.001 | 0.296 | 0.166 | 0.426 | 1.344 | <0.001 | 0.098 | −0.026 | 0.222 | 1.103 | 0.122 |

| One year change of CFI | 0.184 | 0.071 | 0.297 | 1.202 | 0.001 | 0.2940 | 0.150 | 0.438 | 1.342 | <0.001 | 0.048 | −0.124 | 0.219 | 1.049 | 0.586 |

| mMMSE score in the previous year | −0.136 | −0.263 | −0.009 | 0.873 | 0.036 | −0.156 | −0.319 | 0.007 | 0.855 | 0.060 | −0.104 | −0.3137 | 0.105 | 0.901 | 0.329 |

| FCSRT score in the previous year | −0.384 | −0.848 | 0.079 | 0.681 | 0.104 | −0.270 | −0.790 | 0.251 | 0.764 | 0.310 | −0.614 | −1.155 | −0.073 | 0.541 | 0.026 |

| Age at baseline | 0.073 | 0.016 | 0.131 | 1.076 | 0.012 | 0.037 | −0.040 | 0.113 | 1.037 | 0.349 | 0.108 | 0.023 | 0.193 | 1.114 | 0.013 |

| Ethnicity | −0.177 | −0.701 | 0.346 | 1.093 | 0.507 | −0.232 | −0.880 | 0.417 | 0.793 | 0.484 | 0.010 | −0.949 | 0.969 | 1.010 | 0.984 |

| Subjects’ language | 0.272 | −0.382 | 0.926 | 1.313 | 0.415 | 0.370 | −0.514 | 1.254 | 1.448 | 0.412 | 0.076 | −1.034 | 1.185 | 1.079 | 0.894 |

| CDR Global score at baseline | 0.571 | 0.109 | 1.033 | 1.770 | 0.015 | ||||||||||

| Study Partner | |||||||||||||||

| CFI in the previous year | 0.174 | 0.101 | 0.247 | 1.190 | <0.001 | 0.237 | 0.151 | 0.322 | 1.267 | <0.001 | 0.100 | −0.028 | 0.228 | 1.105 | 0.125 |

| One year change of CFI | 0.240 | 0.137 | 0.344 | 1.271 | <0.001 | 0.256 | 0.144 | 0.368 | 1.291 | <0.001 | 0.273 | 0.081 | 0.464 | 1.313 | 0.005 |

| mMMSE score in the previous year | −0.127 | −0.254 | 0.001 | 0.881 | 0.053 | −0.159 | −0.322 | 0.005 | 0.853 | 0.057 | −0.106 | −0.314 | 0.103 | 0.900 | 0.321 |

| FCSRT score in the previous year | −0.353 | −0.817 | 0.111 | 0.703 | 0.136 | −0.216 | −0.761 | 0.329 | 0.806 | 0.438 | −0.675 | −1.209 | −0.142 | 0.509 | 0.013 |

| Age at baseline | 0.068 | 0.005 | 0.131 | 1.070 | 0.036 | 0.034 | −0.049 | 0.116 | 1.034 | 0.424 | 0.100 | 0.007 | 0.192 | 1.105 | 0.034 |

| Ethnicity | −0.275 | −0.826 | 0.276 | 0.759 | 0.328 | −0.360 | −1.031 | 0.311 | 0.698 | 0.293 | 0.048 | −0.954 | 1.050 | 1.049 | 0.9252 |

| Subjects’ language | 0.119 | −0.516 | 0.753 | 1.126 | 0.714 | 0.281 | −0.623 | 1.186 | 1.325 | 0.542 | −0.181 | −1.359 | 0.998 | 0.835 | 0.7638 |

| CDR Global score at baseline | 0.558 | 0.092 | 1.024 | 1.747 | 0.019 | ||||||||||

CFI, Cognitive Function Instrument; mMMSE, Modified Mini-Mental State Exam; FCSRT, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating.

Table 5.

The medium to long term (two-year) predictability of subject and study partner CFI by baseline CDR

| Subjects | All Sample |

CDR = 0 |

CDR = 0.5 |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | p | Estimate | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | p | Estimate | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | p | ||||

| CFI from two years ago | 0.241 | 0.145 | 0.337 | 4.92 | <0.0001 | 0.301 | 0.166 | 0.435 | 4.39 | <0.0001 | 0.088 | −0.028 | 0.204 | 1.49 | 0.136 |

| Two-year change of CFI | 0.177 | 0.051 | 0.303 | 2.76 | 0.006 | 0.279 | 0.118 | 0.439 | 3.40 | 0.001 | 0.037 | −0.140 | 0.213 | 0.41 | 0.684 |

| mMMSE score from two years ago | −0.198 | −0.245 | −0.151 | −8.33 | <0.0001 | −0.224 | −0.282 | −0.167 | −7.62 | <0.0001 | −0.153 | −0.236 | −0.070 | −3.63 | <0.0001 |

| FCSRT score from two years ago | −0.128 | −0.225 | −0.032 | −2.60 | 0.009 | −0.080 | −0.202 | 0.042 | −1.28 | 0.200 | −0.561 | −0.891 | −0.232 | −3.34 | 0.001 |

| Age at baseline | 0.098 | 0.042 | 0.155 | 3.44 | 0.001 | 0.049 | −0.026 | 0.124 | 1.28 | 0.200 | 0.164 | 0.064 | 0.265 | 3.20 | 0.001 |

| Ethnicity | 0.274 | −0.305 | 0.853 | 0.93 | 0.353 | 0.006 | −0.707 | 0.718 | 0.02 | 0.988 | 0.867 | −0.186 | 1.920 | 1.61 | 0.107 |

| Subjects’ language | 0.345 | −0.423 | 1.113 | 0.88 | 0.379 | 0.122 | −0.842 | 1.086 | 0.25 | 0.804 | 0.976 | −0.716 | 2.669 | 1.13 | 0.258 |

| CDR Global score at baseline | 0.929 | 0.398 | 1.461 | 3.43 | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Study Partner | |||||||||||||||

| CFI from two years ago | 0.152 | 0.059 | 0.245 | 3.20 | 0.001 | 0.280 | 0.171 | 0.390 | 5.02 | <0.0001 | −0.001 | −0.132 | 0.130 | −0.01 | 0.989 |

| Two-year change of CFI | 0.226 | 0.137 | 0.315 | 4.96 | <0.0001 | 0.248 | 0.141 | 0.355 | 4.55 | <0.0001 | 0.170 | 0.013 | 0.327 | 2.12 | 0.034 |

| mMMSE score from two years ago | −0.201 | −0.246 | −0.155 | −8.61 | <0.0001 | −0.232 | −0.285 | −0.180 | −8.65 | <0.0001 | −0.179 | −0.264 | −0.095 | −4.16 | <0.0001 |

| FCSRT score from two years ago | −0.125 | −0.233 | −0.016 | −2.25 | 0.025 | −0.050 | −0.197 | 0.097 | −0.67 | 0.503 | −0.590 | −0.935 | −0.245 | −3.35 | 0.001 |

| Age at baseline | 0.083 | 0.028 | 0.139 | 2.93 | 0.003 | 0.028 | −0.043 | 0.099 | 0.78 | 0.436 | 0.166 | 0.062 | 0.270 | 3.12 | 0.002 |

| Ethnicity | 0.238 | −0.398 | 0.873 | 0.73 | 0.464 | −0.166 | −0.931 | 0.599 | −0.43 | 0.671 | 1.009 | −0.036 | 2.053 | 1.89 | 0.058 |

| Subjects’ language | 0.172 | −0.602 | 0.946 | 0.44 | 0.663 | 0.110 | −0.909 | 1.129 | 0.21 | 0.832 | 0.736 | −1.068 | 2.539 | 0.80 | 0.424 |

| CDR Global score at baseline | 0.947 | 0.423 | 1.470 | 3.55 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

CFI, Cognitive Function Instrument; mMMSE, Modified Mini-Mental State Exam; FCSRT, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating.

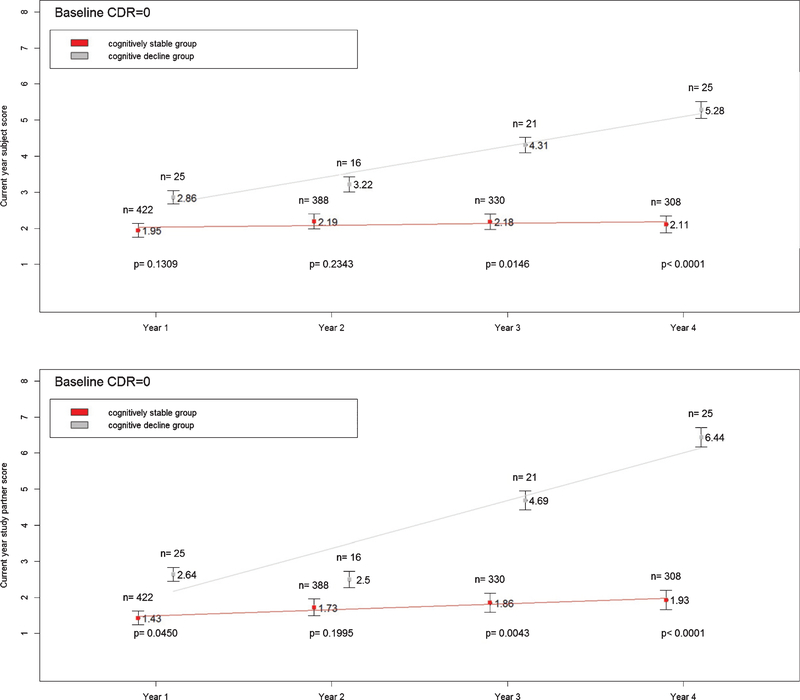

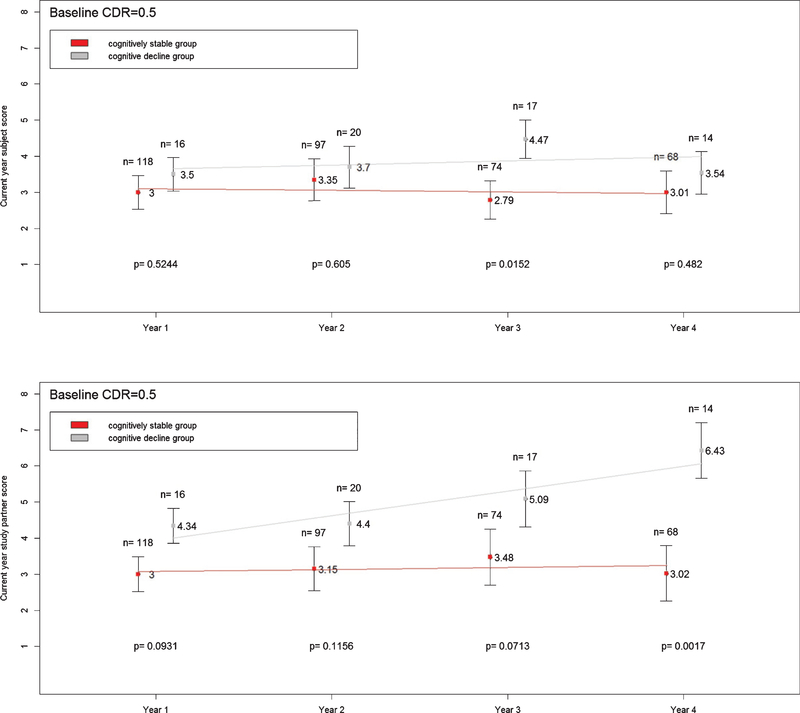

Figure 1 shows that differences in subject and study partner CFI scores between the cognitively stable and cognitive decline groups continued to increase over time at CDR 0. Figure 2 shows that while differences in study partner CFI between cognitively stable and cognitive decline groups steadily increased over time at CDR 0.5, such increase was not observed in subject CFI. The differences in subject CFI between the cognitively stable and cognitive decline groups were variable at CDR 0.5.

Fig. 1.

Mean subject (top panel) and study partner (bottom panel) CFI scores at current year in cognitively stable and cognitive decline groups. Subjects with CDR=0 only. Vertical bars represent standard deviation.

Fig. 2.

Mean subject (top panel) and study partner (bottom panel) CFI scores at current year in cognitively stable and cognitive decline groups. Subjects with CDR = 0.5 only. Vertical bars represent standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

The CFI was developed by the ADCS to examine whether subjective report from a self-administered instrument is a reliable measure of change, and is useful in diagnostic assessment and as an outcome in dementia prevention trials. Results demonstrate reasonable test-retest reliability at three months for both subject and study partner responses. However, the reliability of subject and study partner CFI differ between CDR 0 and 0.5. Specifically, the subject is more reliable than the study partner at CDR 0 while the study partner is more reliable at CDR 0.5. This finding suggests that the best reporter of CFI is dependent on CDR level.

Additionally, our findings provide data on when in the trajectory of decline the CFI is likely to be most sensitive in predicting later changes. We examined the predictive value of the previous year score and the change scores for each CDR group. Our results showed that both subject’s and study partner’s baseline and longitudinal CFI were sensitive to cognitive decline in CDR 0 group; however, subject’s reports were poor predictor of cognitive decline in CDR 0.5 group. In particular, subject CFI score from previous year and change score in subject CFI were not predictive of future changes at CDR 0.5. Among the CDR 0.5 group, only the study partner’s longitudinal CFI predicted cognitive decline. Both one- and two-year change in study partner CFI predicted future changes in subject with CDR 0.5. The poor prediction ability of self-report from the subject with a CDR 0.5 is consistent with a previous study in which researchers found that subject CFI underestimates cognitive deterioration when there is a progression to cognitive deficits [10]. More importantly, our results suggest that while baseline values among the cognitively healthy might be a marker of risk to progress, change scores including those from study partners may be useful outcome measures in predicting decline among individuals with some impairment.

Furthermore, our study used “cognitive evaluation trigger” as an outcome measure to examine the degree to which subjective complaint is related to critical clinical declines. Consistent with the previous CFI studies using subtle changes in cognitive scores as outcome measures [9, 10], we found that both subject and study partner CFI are good predictors of cognitive decline in individuals with normal cognition. Our results show that subject CFI may be a better predictor of decline than study partner CFI in the CDR 0 group. Moreover, the current study examined subjective complaint in healthy elders who may have some impairment and were not part of the longitudinal CFI study (i.e., CDR 0.5 group) [10]. Our work addressed the ability of CFI to capture a clinically detectable phenomenon among non-demented elders with different clinical status. In particular, as trials plan to assess even earlier stages of disease it would be important to focus on subject rather than study partner scores. Alternately in studies with symptomatic individuals, even at the earliest stages it would seem that the study partner score alone would be most sensitive. The results provide valuable insights into the clinical research operations.

Some limitations to this study should be considered. First, it should be noted that our use of cognitive evaluation trigger which includes the mMMSE and FCSRT cutoff points is one of many possible methods of identifying cognitive impairment. Continuous measures of cognitive performance, for instance, are important in assessing trajectories of change. However, our selected cutoff points have been extensively used in the literature to distinguish individuals with and without dementia [8, 21–23]. While the FCSRT score is not age or education adjusted, the cut-score was selected based on its ability to identify individuals with dementia in a criterion sample [22]. It is important to note that our sample is similar to the criterion sampling, except ours have a higher level of education. Second, while it is known that depression affects cognitive function, examining the effect of depressive symptoms on the predictive utility of CFI and overall decline is beyond the scope of the current paper. Third, our study included a cohort consisting mostly of highly educated participants. Future studies should examine the CFI in a more representative sample with a wider range of education. Fourth, it is possible that subjective cognitive complaint may have been a motivator to participate in this study, and thus, it is unclear to what extent sample characteristics are generalizable to the larger older population or whether unintended sampling biases may have affected the results. In fact, very little overall change in cognition was observed in our cohort. While there was an association between cognitive decline and the CFI scores during a four-year observational period, the association would be stronger if a cohort with greater cognitive change was included. This could be achieved with a longer period of observation or with a cohort at greater risk. Lastly, we did not investigate how often the study partners were in contact with the subjects. However, many of our study partners were living with the subjects at the time of the evaluation. Controlling for this factor would likely strengthen the relationship between study partner CFI and cognitive decline.

In conclusion, the current study confirms that self-reported subjective change can be reliably assessed from both elderly subjects and their study partners with the CFI. We also found that cognitive decline was predicted differentially by CDR level, with subject CFI scores providing the best prediction for those with CDR 0 while study partner CFI predicted best for those at CDR 0.5. While large-samples, long duration, high costs and physical constraints are major barriers to the success of AD clinical prevention trials [24], our findings contribute to the validation of self-administered assessments that improve the efficiency and reduce the cost of these trials. Since subjective cognitive complaints might be the first sign for older patients to seek clinical services or care for memory loss, it is important to assess how these cognitive complaints predict objective cognitive declines. CFI allows us to assess cognitive complaint as a continuous variable and examine the degree to which subjective cognitive complaint is associated with future cognitive declines.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/16-1294r2).

REFERENCES

- [1].Hohman TJ, Beason-Held LL, Lamar M, Resnick SM (2011) Subjective cognitive complaints and longitudinal changes in memory and brain function. Neuropsychology 25, 125–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wang L, van Belle G, Crane PK, Kukull WA, Bowen JD, McCormick WC, Larson EB (2004) Subjective memory deterioration and future dementia in people aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 52, 2045–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Reisberg B, Shulman MB, Torossian C, Leng L, Zhu W (2010) Outcome over seven years of healthy adults with and without subjective cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement 6, 11–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jessen F, Feyen L, Freymann K, Tepest R, Maier W, Heun R, Schild HH, Scheef L (2006) Volume reduction of the entorhinal cortex in subjective memory impairment. Neurobiol Aging 27, 1751–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Saykin AJ, Wishart HA, Rabin LA, Santulli RB, Flashman LA, West JD, McHugh TL, Mamourian AC (2006) Older adults with cognitive complaints show brain atrophy similar to that of amnestic MCI. Neurology 67, 834–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Amariglio RE, Becker JA, Carmasin J, Wadsworth LP, Lorius N, Sullivan C, Maye JE, Gidicsin C, Pepin LC, Sperling RA, Johnson KA, Rentz DM (2012) Subjective cognitive complaints and amyloid burden in cognitively normal older individuals. Neuropsychologia 50, 2880–2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jessen F, Amariglio RE, van Boxtel M, Breteler M, Ceccaldi M, Chetelat G, Dubois B, Dufouil C, Ellis KA, van der Flier WM, Glodzik L, van Harten AC, de Leon MJ, McHugh P, Mielke MM, Molinuevo JL, Mosconi L, Osorio RS, Perrotin A, Petersen RC, Rabin LA, Rami L, Reisberg B, Rentz DM, Sachdev PS, de la Sayette V, Saykin AJ, Scheltens P, Shulman MB, Slavin MJ, Sperling RA, Stewart R, Uspenskaya O, Vellas B, Visser PJ, Wagner M (2014) A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 10, 844–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ferris SH, Aisen PS, Cummings J, Galasko D, Salmon DP, Schneider L, Sano M, Whitehouse PJ, Edland S, Thal LJ (2006) ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: Overview and initial results. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 20, S109–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Walsh SP, Raman R, Jones KB, Aisen PS (2006) ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: The Mail-In Cognitive Function Screening Instrument (MCFSI). Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 20, S170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Amariglio RE, Donohue MC, Marshall GA, Rentz DM, Salmon DP, Ferris SH, Karantzoulis S, Aisen PS, Sperling RA (2015) Tracking early decline in cognitive function in older individuals at risk for Alzheimer disease dementia: The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Cognitive Function Instrument. JAMA Neurol 72, 446–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cummings JL, Raman R, Ernstrom K, Salmon D, Ferris SH (2006) ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: Behavioral measures in primary prevention trials. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 20, S147–S151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Galasko D, Bennett DA, Sano M, Marson D, Kaye J, Edland SD (2006) ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: Assessment of instrumental activities of daily living for community-dwelling elderly individuals in dementia prevention clinical trials. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 20, S152–S169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Salmon DP, Cummings JL, Jin S, Sano M, Sperling RA, Zamrini E, Petersen RC, Edland SD, Thal LJ, Ferris SH (2006) ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: Development of a brief verbal memory test for primary prevention clinical trials. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 20, S139–S146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sano M, Zhu CW, Whitehouse PJ, Edland S, Jin S, Ernstrom K, Thomas RG, Thal LJ, Ferris SH (2006) ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: Pharmacoeconomics: Assessing health-related resource use among healthy elderly. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 20, S191–S202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Schneider LS, Clark CM, Doody R, Ferris SH, Morris JC, Raman R, Reisberg B, Schmitt FA (2006) ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: ADCS-clinicians’ global impression of change scales (ADCS-CGIC), self-rated and study partner-rated versions. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 20, S124–S138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Patterson MB, Whitehouse PJ, Edland SD, Sami SA, Sano M, Smyth K, Weiner MF (2006) ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: Quality of life assessment (QOL). Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 20, S179–S190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Teng EL, Chui HC (1987) The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry 48, 314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Grober E, Buschke H, Crystal H, Bang S, Dresner R (1988) Screening for dementia by memory testing. Neurology 38, 900–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Berg L (1988) Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). Psychopharmacol Bull 24, 637–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tombaugh TNHA, McDowell I, Kristjansson B (1996) Mini-mental state examination (MMSE) and the modified MMSE (3MS): A psychometric comparison and normative data. Psychol Assess 8, 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, Thal L, Wallace RB, Ockene JK, Hendrix SL, Jones BN 3rd, Assaf AR, Jackson RD, Kotchen JM, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Wactawski-Wende J (2003) Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 289, 2651–2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Buschke H, Kuslansky G, Katz M, Stewart WF, Sliwinski MJ, Eckholdt HM, Lipton RB (1999) Screening for dementia with the memory impairment screen. Neurology 52, 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lipton RB, Katz MJ, Kuslansky G, Sliwinski MJ, Stewart WF, Verghese J, Crystal HA, Buschke H (2003) Screening for dementia by telephone using the memory impairment screen. J Am Geriatr Soc 51, 1382–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sano M, Egelko S, Donohue M, Ferris S, Kaye J, Hayes TL, Mundt JC, Sun CK, Paparello S, Aisen PS (2013) Developing dementia prevention trials: Baseline report of the Home-Based Assessment study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 27, 356–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]