Abstract

Background and Aims

Because functional–structural plant models (FSPMs) take plant architecture explicitly into consideration, they constitute a promising approach for unravelling plant–plant interactions in complex canopies. However, existing FSPMs mainly address competition for light. The aim of the present work was to develop a comprehensive FSPM accounting for the interactions between plant architecture, environmental factors and the metabolism of carbon (C) and nitrogen (N).

Methods

We developed an original FSPM by coupling models of (1) 3-D wheat architecture, (2) light distribution within canopies and (3) C and N metabolism. Model behaviour was evaluated by simulating the functioning of theoretical canopies consisting of wheat plants of contrasting leaf inclination, arranged in pure and mixed stands and considering four culm densities and three sky conditions.

Key Results

As an emergent property of the detailed description of metabolism, the model predicted a linear relationship between absorbed light and C assimilation, and a curvilinear relationship between grain mass and C assimilation, applying to both pure stands and each component of mixtures. Over the whole post-anthesis period, planophile plants tended to absorb more light than erectophile plants, resulting in a slightly higher grain mass. This difference was enhanced at low plant density and in mixtures, where the erectophile behaviour resulted in a loss of competitiveness.

Conclusion

The present work demonstrates that FSPMs provide a framework allowing the analysis of complex canopies such as studying the impact of particular plant traits, which would hardly be feasible experimentally. The present FSPM can help in interpreting complex interactions by providing access to critical variables such as resource acquisition and allocation, internal metabolic concentrations, leaf life span and grain filling. Simulations were based on canopies identically initialized at flowering; extending the model to the whole cycle is thus required so that all consequences of a trait can be evaluated.

Keywords: Carbon, erectophile, functional–structural plant model, leaf inclination, light competition, light model, mixture, nitrogen, planophile, plant interactions, Triticum aestivum, wheat

INTRODUCTION

Plant architecture, defined as organ topology and geometry, represents the interface of plants with their environment (Thompson, 1945; Hallé, 1999; Prusinkiewicz and Runions, 2012; Bucksch et al., 2017). As such, plant architecture determines the competition for resources (light, water and soil nutrients), the perception of neighbours (e.g. through photomorphogenetic and thigmomorphogenetic signals) as well as the interactions with other biotic and abiotic factors (humidity, temperature, pollinators, pests, diseases and pesticides). The physiological processes involved in plant growth and development are themselves dependent on the acquisition of resources and perceived signals (Varlet-Grancher et al., 1993; Ballaré and Casal, 2000), thereby leading to complex feedbacks. Taking into account the architecture of plants is particularly important when analysing species or varietal mixtures in which individual plants may perceive different environmental conditions and/or respond differently to the environment (Sinoquet, 1993; Sinoquet and Cruz, 1995; Barillot et al., 2011). Despite the agronomic interest provided by crop mixtures in terms of biomass production, input reduction or agrosystem biodiversity (for a review, see Malézieux et al., 2009), our lack of knowledge about the complex plant–plant interactions makes it difficult to elaborate rules for assembling species or varieties in high-performance intercropping systems (Litrico and Violle, 2015; Barot et al., 2017). Moreover, the very large number of possible combinations of species and varieties is beyond what can be analysed experimentally.

Functional–structural plant models (FSPMs) allow us to account explicitly for the interactions between plant architecture, functioning and environment (Godin and Sinoquet, 2005; Fourcaud et al., 2008; Vos et al., 2010; DeJong et al., 2011). In addition, FSPMs simulate a crop using an individual-based approach in which individual plants may have different phenotypes and/or genotypes. FSPMs therefore represent a promising tool for simulating plant–plant interactions and identifying ideotypes suited for various agronomic systems. However, existing architectural models mainly focus on competition for light and carbon (C) acquisition (Fournier and Andrieu, 1999; Louarn et al., 2008; Evers et al., 2010; Sarlikioti et al., 2011; Barillot et al., 2011, 2014). Obviously, water and nitrogen (N) are important resources which regulate plant functioning and crop production, and disregarding them hampers our ability to simulate plant behaviour in various conditions including heterogeneous crops. As a step towards more comprehensive FSPMs, Louarn and Faverjon (2018) developed a generic individual-based model for legume species which integrates the responses of plants to light, water and N using the concept of potential plant growth and an allometric allocation of biomass. We previously developed a mechanistic FSPM (CN-Wheat) simulating both C and N allocation in wheat culms during the post-anthesis period (Barillot et al., 2016a, b). The approach used in CN-Wheat is to formalize by differential equations the main physiological processes involved in the primary metabolism of C and N and to keep track of the metabolites at the organ scale. In a previous development of CN-Wheat, light absorption was set from experimental measurements, which limited our ability to simulate contrasting irradiance conditions, wheat varieties or complex cropping systems such as mixtures.

The aim of the present paper is to describe a comprehensive and mechanistic FSPM accounting for the interactions between the primary metabolism of C and N, the 3-D plant architecture and environmental factors (light, temperature, humidity and soil N). For this purpose, we developed a simulator based on the coupling of (1) the CN-Wheat model with (2) the ADEL-Wheat (Fournier et al., 2003), an architectural model of wheat plants, and (3) the radiosity model Caribu (Chelle and Andrieu, 1998). In order to illustrate the behaviour of this FSPM, we have simulated the functioning of wheat canopies composed of plants that differ in a single trait, i.e. leaf inclination. Leaf inclination is amongst the major traits considered in breeding programmes of cereals such as wheat (Zhu et al., 2010; Reynolds et al., 2012) and rice (Cheng et al., 2007; Peng et al., 2008). One difficulty for understanding the impact of this trait from experimental data is the entanglement between other architectural traits (Araus et al., 1993) or between light and N profiles within a canopy, with implications for the photosynthesis light response and leaf life span for instance (Li et al., 2013). Using a mechanistic approach of C–N interactions may allow a step further in the analysis. Here, we analyse how the present FSPM can help in interpreting these interactions, by providing access to critical variables such as resource acquisition and allocation, internal metabolic concentrations, green leaf area and grain filling during the post-anthesis period. We considered both homogenous and complex canopies resulting from the mixture of erectophile and planophile plants with contrasting sowing densities and sky conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After a brief overview of the CN-Wheat model, we will present the method used for coupling CN-Wheat, ADEL-Wheat and Caribu models. Finally, we will describe the simulations performed for assessing model behaviour in theoretical scenarios involving plants with contrasting leaf inclination in pure and mixed stands at various densities.

Overview of the CN-Wheat model

CN-Wheat was developed for post-anthesis stages, during which photosynthetic organs have already reached their final dimensions; thus, plant structure is considered to be static, except for leaf senescence. The model is defined at culm scale, which is represented by botanical modules: the root system, each photosynthetic organ, the grains and a common pool mimicking the phloem and allowing fluxes of metabolites among organs. The model accounts for the main C and N metabolites and physiological processes encountered in wheat plants. Briefly, roots are assumed to absorb nitrates according to the nitrate concentration in the soil and the root internal concentration of C and N metabolites. Absorbed nitrates are exported towards the photosynthetic organs according to their respective transpiration. Root supply with carbohydrates results from the unloading of phloemic sucrose following a Michaelis–Menten equation. For photosynthetic organs, the assimilation of C is calculated by using a biochemical model (Farquhar et al., 1980; Müller et al., 2005; Braune et al., 2009) which is regulated by organ incident photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), temperature [calculated from Penman–Monteith’s equations (Monteith, 1975)] and N content. Assimilated C is used as (1) a substrate for the synthesis of mobile and storage carbohydrates and (2) a co-substrate (along with nitrates) for the synthesis of amino acids which are assumed to be in a turnover with the protein compartment. A sub-model triggers the death of a part of the photosynthetic tissues when their protein concentrations drop below a given threshold. The loading of mobile metabolites (sucrose and amino acids) into the phloem (transport resistance equations) allows sink organs (mainly roots and grains) to be supplied. The originality of the model is that physiological processes that drive C and N fluxes are regulated by both environmental factors and local concentrations of metabolites.

As mentioned, CN-Wheat includes a sub-model of photosynthesis that requires computing the distribution of light absorption at the organ scale. In the previous version of the model, this information was estimated from experimental data rather than a radiative model because the 3-D representation of plant architecture was not supported.

Model coupling

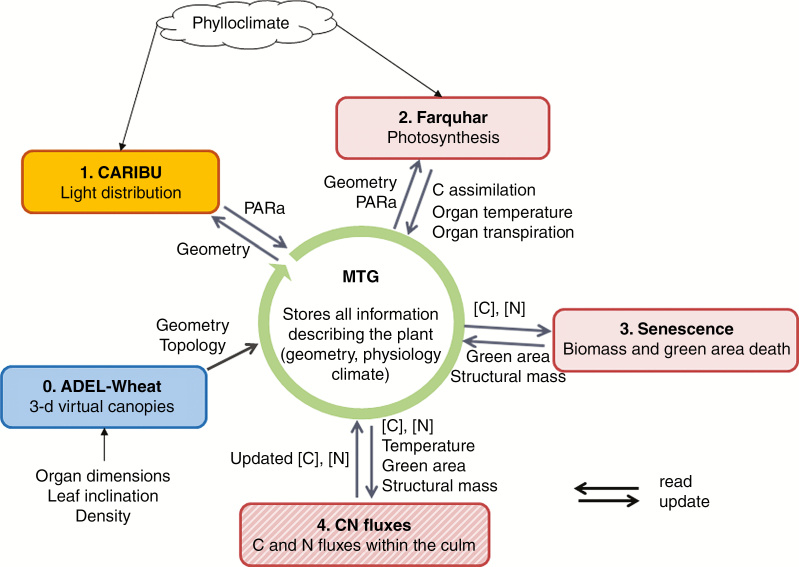

The coupling of CN-Wheat, ADEL-Wheat (Fournier et al., 2003) and Caribu (Chelle and Andrieu, 1998) models uses the Multiscale Tree Graph formalism (MTG) as a central data structure in which each model stores and reads information (Fig. 1). The MTG is a generic formalism allowing the representation of plant architecture at different scales, in which various properties can be attributed to each node of a graph (Godin and Caraglio, 1998; Balduzzi et al., 2017). Specific adaptors were therefore developed in order to use MTG objects as a support of information shared by the different models. Each organ of simulated plants was encoded in the MTG as a topological node bearing the (1) geometrical information required by ADEL-Wheat to build up the plant architecture in 3-D, (2) absorbed PAR computed by the light model from the 3-D mock-ups, (3) C assimilation, organ temperature and transpiration computed by the Farquhar model from the absorbed PAR and climatic information, (4) organ green area and structural dry mass computed from C and N concentrations and (5) the values of the metabolic compartments computed by CN-Wheat. Model coupling was performed within the OpenAlea framework (Pradal et al., 2008, 2015) which defines a conceptual framework to simulate complex functional–structural models by combining heterogeneous components while preserving modularity (Fournier et al., 2010; Garin et al., 2014, 2017). Here, it was used to allow the scheduling and exchange of information as described in Fig. 1. The present FSPM is distributed under an open source licence (CeCILL-C), which is fully compatible with the FSF’s L-GPL licence. The source code is hosted on a French software platform (https://sourcesup.renater.fr/projects/fspm-wheat/) and is available on request from the authors.

Fig. 1.

Coupling of ADEL-Wheat, Caribu and CN-Wheat models using the Multiscale Tree Graph formalism (MTG). The MTG is used as a central data structure in which each model stores and reads information (black arrows). The CN-Wheat model was decomposed in three sub-models simulating the photosynthesis based on the Farquhar approach, tissue death (senescence), and the fluxes of C and N using a solver of ordinary differential equations (hatched box). Each wheat organ was encoded as a topological node in the MTG bearing (1) the geometrical and topological information required by ADEL-Wheat to build up the plant architectures in 3-D, (2) the absorbed PAR (PARa) computed by the light model from the 3-D mock-ups and (3) the values of the metabolic compartments ([C], [N]) computed by CN-Wheat sub-models. Numbering refers to the order in which the models are called.

The behaviour of the model was assessed by running simulations that involved three types of calculation that are listed below and presented in detail in the following sections.

(1) The above-ground architectures of planophile and erectophile wheat plants at flowering were built up using the ADEL-Wheat model and arranged in pure and mixed stands at four different culm densities.

(2) Light absorption at organ scale was simulated with an hourly time step by using the Caribu model. We considered three sky conditions with contrasting proportions of diffuse light: (a) clear sky; (b) overcast sky; and (c) actual proportions of diffuse light as measured by a meteorological station during the grain-filling period.

(3) Photosynthesis, N acquisition, synthesis, and allocation of C and N metabolites in culms were simulated by using the CN-Wheat model. We keep track of N availability in the soil using a budget equation between absorption by plants and nitrification assuming a constant rate of mineralization.

In these simulations, the 3-D architecture is built only once by ADEL-Wheat, then each time step consists of (1) running Caribu and updating the MTG with light absorption and (2) running CN-Wheat and updating the MTG with new values for C and N metabolites.

Above-ground architectures of virtual canopies

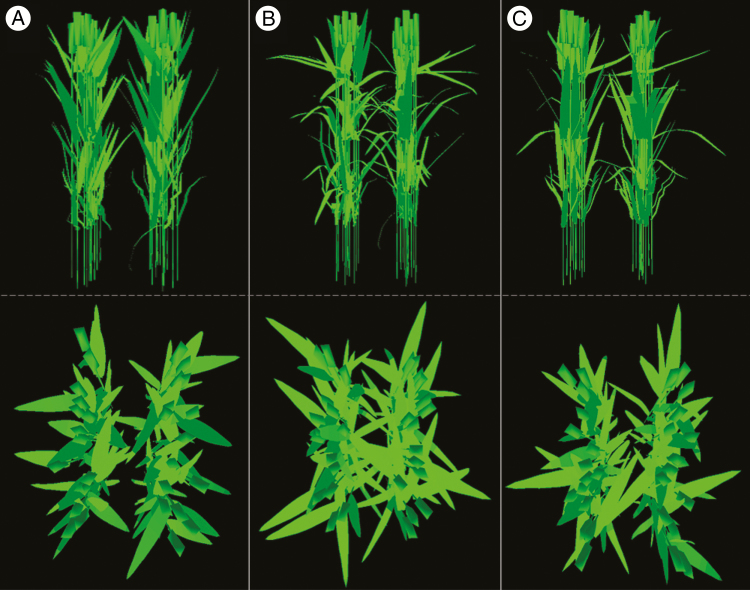

The ADEL-Wheat model was designed to generate the 3-D architecture of planophile and erectophile plants by using databases of leaf shapes and curvatures of the cultivars ‘Soissons’ and ‘Caphorn’, respectively (original data in Bertheloot et al., 2012). They will subsequently be referred to simply as planophile and erectophile. Because CN-Wheat is defined at the culm scale, 3-D virtual canopies were approximated as a collection of individual culms. Culms of planophile and erectophile plants were composed of four vegetative phytomers each consisting of a lamina, a sheath and an internode, plus an uppermost phytomer consisting of the peduncle and the ear (chaff and grains). Organ dimensions (length, width, height and area) were taken from Barillot et al. (2016b; see their Table 3) and were assumed to be identical between culms. Four culm densities were simulated for both pure and mixed stands: 200, 410, 600 and 800 culms m–2, hereafter referred to as D200, D410, D600 and D800, respectively. D410 and D600 represent the usual range observed in agronomic conditions. For all stands, the inter-row distance was 0.15 m. The mixtures were composed of 50 % planophile and 50 % erectophile plants distributed along each row. Leaf area index (LAI) ranged from 2.14 at D200 to 8.57 at D800. Three different canopies were built up for each of the four densities (pure planophile, pure erectophile and the mixture), each of them being composed of culms with identical organ dimensions but different leaf inclination (Fig. 2). In order to have more realistic computations of light absorption, we defined a random leaf azimuth and a variation of 0.03 m around the theoretical position of each culm.

Fig. 2.

Horizontal (up) and vertical (down) views of the virtual pure stands of erectophile plants (A), planophile plants (B) and the mixture (C). The illustration is shown for a density of 410 culms m–2.

Computation of light absorption

The Caribu model was used to compute the absorption of PAR at the organ scale using a radiosity algorithm. First, the relative PAR absorption was simulated for (1) diffuse radiation sources – computations were run one single time per stand because we assumed a constant plant architecture over the post-anthesis period and (2) direct radiation sources according to the day of year (DOY), hour of the day and latitude. Then, relative absorption simulated for both diffuse and direct radiation was used to define three scenarios of sky conditions with a similar incident PAR but with contrasting proportions of diffuse light (rdiff:PARi). The first scenario represented a constant clear sky with rdiff:PARi = 25 %; the second scenario represented a constant overcast sky (rdiff:PARi = 100 %); and the third scenario used the actual proportion of diffuse light as measured by a meteorological station. Finally, the absolute PAR absorbed (, μmol m–2 s–1) by a photosynthetic organ of type tp (standing for lamina, sheath, internode, peduncle or chaff) of rank i was calculated as:

| (1) |

Where and (μmol m–2 s–1) are the relative PAR absorption for the diffuse and direct radiation, respectively. PARi (μmol m–2 s–1) is the incident PAR above the canopy.

Diffuse radiation was approximated by a set of light sources from a sky vault discretized in 20 solid angle sectors including five zenith angles. The contribution of each sky sector to the incoming light energy was weighted according to the standard overcast sky radiation distribution (Moon and Spencer, 1942). Regarding direct radiation, relative light absorption was calculated hourly from DOY 150 to 199 between 05.00 h and 19.00 h UTC (co-ordinated universal time) for latitude 49°N (during this period, daylight duration changes by approx. 10 min, which was neglected in our simulations).

For each condition, the simulations of light absorption were performed on virtual canopies consisting of 1000 culms. Calculations were done using the built-in algorithm of the infinite periodic canopy in the Caribu model (Chelle et al., 1998), thus allowing simulation of light absorption without border effects. At present, CN-Wheat does not include a sub-model to calculate leaf optical properties; these were therefore kept constant during the simulated period: reflectance and transmittance of leaves were set to 0.10 and 0.05, respectively, and stem reflectance to 0.10. By keeping these optical properties constant, we assumed that the variations in optical properties due to senescence (which first occurs in the bottom of the canopy) have little effect on the light absorption by the remaining photosynthetically active tissues. However, the computation of photosynthesis and other metabolic fluxes was performed for living tissues only. Lastly, the absorption of light by enclosed tissues was considered to be null, i.e. for the first two internodes, a part of the fourth one and a part of the peduncles that are enclosed within sheaths.

CN-Wheat model inputs and sky conditions

The inputs of CN-Wheat model are (1) the soil nitrate concentration at anthesis, (2) the meteorological data and (3) the distribution of relative absorbed PAR among photosynthetic organs. Nitrate concentration in soil was initialized at 4.50 g m–3 (Barillot et al., 2016b, ‘H3’ treatment), which represents a standard agronomic application of 3 g N m–2 at anthesis. Regarding the meteorological data, we used the hourly incident PAR (PARi), air temperature (°C), humidity, CO2 (ppm) and wind speed at 2 m above the canopy (m s–1) collected by a meteorological station located in Lusignan, France (46°25′N, 0°7′W) in 2009. Wind speed above the canopy is required to compute wind speed at organ height which determines the boundary layer conductance and ultimately organ temperature (see Supplementary information 2 in Barillot et al., 2016a). The same meteorological data were used for all stands and sky conditions, except for the proportion of diffuse light. Initialization of the metabolic compartments of each organ was taken from Barillot et al. (2016b). The CN-Wheat model was run with an hourly time step.

In principle, the CN-Wheat model could be run for each culm of a stand. However, computational time for simulating the whole post-flowering period with a personal computer is typically half an hour per culm. In order to deal with available computer resources, we performed two types of simulation. First CN-Wheat was run for one ‘average culm’ per pure stand and one ‘average planophile’ and one ‘average erectophile’ culm per mixture. For each stand, PAR absorption of each organ was therefore averaged across all culms of the same plant type (n = 1000), and the simulation of C and N dynamics (i.e. outputs of the CN-Wheat model) therefore represents canopies composed of ‘average’ culms. Secondly, CN-Wheat was run for individual plants, considering sub-samples of ten culms in each stand. This provided insight into the behaviour at the individual plant level and the variation within each population.

RESULTS

The functioning of planophile and erectophile plants during the post-anthesis period was simulated in theoretical scenarios with contrasting cropping systems, densities and sky conditions. We present below the simulation results related to the physical structure of the canopies, the absorption of light and the acquisition of C, and the consequences on the dynamics of lamina green area and grain filling.

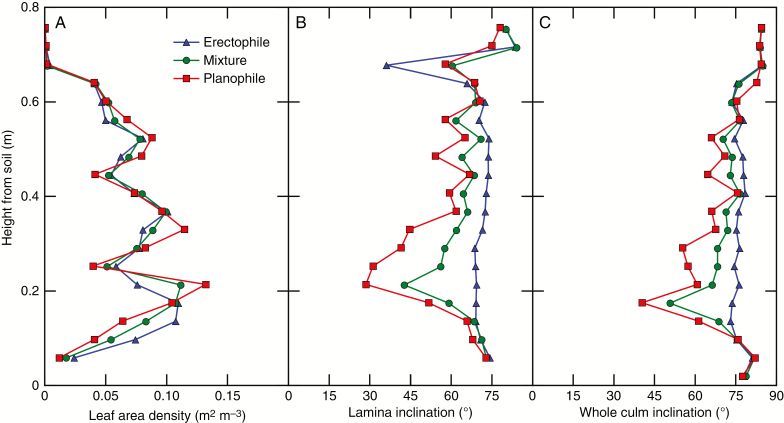

Vertical profile of lamina area density and inclination

Detailed profiles of leaf area density and inclination are illustrated for D410 only, as the density did not affect the relative profiles (Fig. 3). In our theoretical canopies, almost all leaves were distributed between 0.05 and 0.6 m height for all stands (Fig. 3A). The profiles of leaf area density were rather uniform despite occasional decreases due to the elongated internodes that space out the leaves. The vertical distribution of leaf area density was very similar between the planophile, erectophile and mixed stand, which was expected as all plants have the same characteristics for internode and sheath lengths. In contrast, the stands differed by the vertical profile of lamina inclination (Fig. 3B). In the erectophile stand, mean lamina inclination was 70.4 ± 9° and showed little vertical gradient except at approx. 0.65 m height; however, this deviation was associated with a very low foliar density (Fig. 3A). In the planophile stand, mean lamina inclination was 58.9 ± 14°, and inclination showed a marked vertical gradient, ranging from approx.70° at the top of the canopy to 30° at 0.2 m above ground. Lamina inclination was 70° again below 0.2 m because tissues in this layer correspond mainly to the insertion points of laminae in the stem. As expected, the mixture exhibited an intermediary profile of lamina inclination (mean = 65.7 ± 9°). Also, the differences in inclination among stands decreased when taking into account the vertical components such as internodes, peduncles and chaff. Indeed, mean inclination calculated for the whole culms was 70.4, 77.42 and 74.88° for the planophile, erectophile and mixed stand, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Vertical profiles of leaf area density (A), lamina inclination (B) and whole culm inclination (C). Results are shown for the density of 410 culms m–2 only as the density did not affect the relative profiles.

Simulation of PAR absorption

In this section, we present the differences of PAR absorption by planophile and erectophile culms between pure and mixed stands according to the sky conditions (actual, clear and overcast sky) and culm densities.

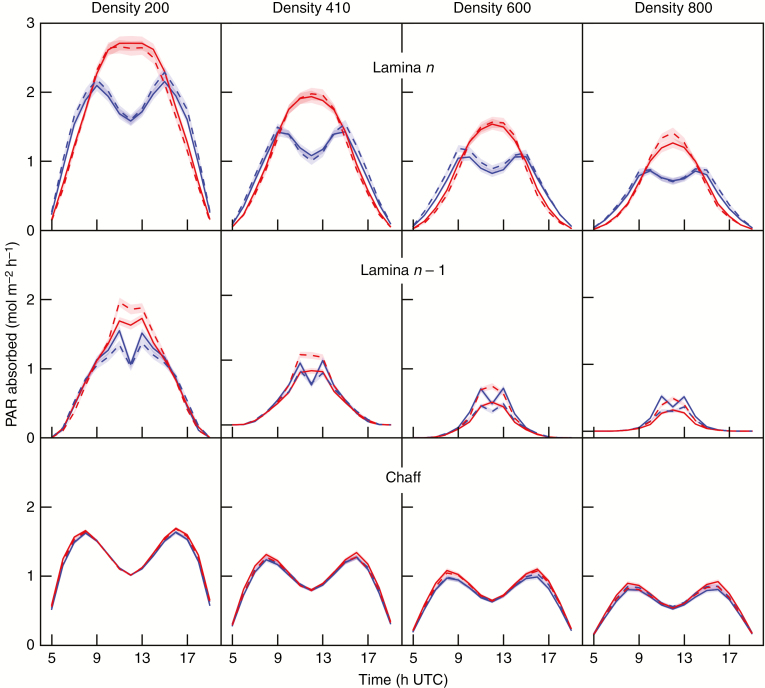

Insights into the daily variations of absorbed PAR.

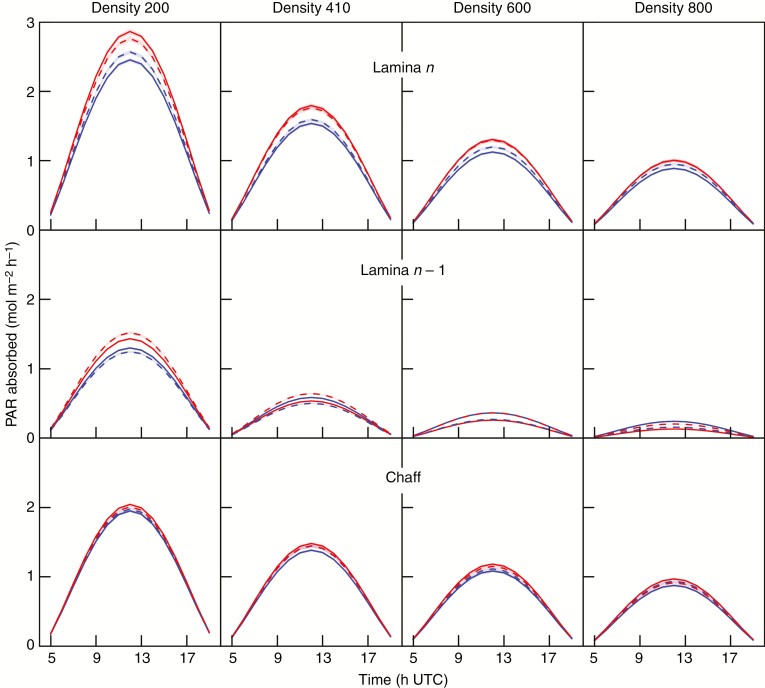

The simulated daily variations of absorbed PAR (PARa) for three main organs (the chaff, lamina of the flag leaf and the penultimate lamina) are shown for full direct radiation (Fig. 4) and diffuse radiation (Fig. 5), at the four culm densities. For the sake of clarity, simulations are shown for one representative day (summer solstice, DOY 173) using the theoretical incident PAR calculated following the model of Bird and Riordan (1986).

Fig. 4.

Theoretical absorption of PAR under direct radiation sources for densities of 200, 410, 600 and 800 culms m–2. The results are shown for three main organs from the top to the bottom of the canopy, i.e. for the chaff, lamina of the flag leaf (lamina n) and penultimate lamina (lamina n – 1) of planophile (red) and erectophile (blue) plants in pure stands (solid lines) and mixed stands (dashed lines). The shaded areas represent the confidence intervals (α = 0.05; n culms = 1000). For this illustration, we assumed that the incident PAR followed the theoretical astronomical calculations.

Fig. 5.

Theoretical absorption of PAR under diffuse radiation sources for densities of 200, 410, 600 and 800 culms m–2. The results are shown for three main organs from the top to the bottom of the canopy, i.e. for the chaff, lamina of the flag leaf (lamina n) and penultimate lamina (lamina n – 1) of planophile (red) and erectophile (blue) plants in pure stands (solid lines) and mixed stands (dashed lines). The shaded areas represent the confidence intervals (α = 0.05; n culms = 1000). For this illustration, we assumed that the incident PAR followed the theoretical astronomical calculations.

The lamina of the flag leaf (lamina n) absorbed more PAR than the chaff and the penultimate lamina (lamina n – 1) whatever the time of day, stand and sky conditions. The ratio between absorbed PAR per culm at D800 and D200 was approx. 1:1.8 for chaff, 1:3 for lamina n and 1:5 for lamina n – 1. This illustrates the increasing contribution of upper layers, especially chaff, to light absorption at higher densities. The daily dynamics of absorbed PAR by each organ were significantly different between direct and diffuse conditions. Under direct radiation (Fig. 4A), the PAR absorbed by planar components (planophile laminae) was maximum for high solar elevations (10–14 h UTC) while the PAR absorbed by erect components (erectophile laminae and chaff) was maximum around 8 and 16 h UTC, with a strong decrease around mid-day. Lamina n of planophile plants absorbed more PAR than those of erectophile plants at high solar elevations, whereas the opposite occurred at low solar elevations, whatever the density. For intermediate and high densities, lamina n – 1 of erectophile stands absorbed more light than those of planophile stands, as expected from the higher transmission of the upper layer. This advantage was lost, however, in mixtures where laminae n – 1 of planophile plants were more efficient at absorbing the light transmitted to that layer than those of erectophile plants.

Under diffuse radiation, the diurnal dynamics of PARa were similar for all organs and stands as they follow the pattern of incoming solar energy, the maximum being reached during the highest solar elevations (Fig. 5). Lamina n of planophile plants absorbed more PAR than that of erectophile plants, but the differences were smaller than for clear sky. Lamina n of erectophile plants absorbed more light in the mixture compared with pure stands. Increasing plant density in the mixture decreases the difference between the upper laminae of planophile plants and those of erectophile plants. Such behaviour is expected to result from the combination of a slightly higher position of leaf tissues due to erectophile behaviour and the higher contribution of light coming at a low zenith angle in the incoming PAR. Except at the lowest density, PAR absorption was higher for the penultimate laminae of erectophile pure stands than for those of planophile pure stands, whereas the opposite result was simulated for the mixtures. Such hierarchy was also observed for the lower laminae (n – 2, n – 3) including at D200 (data not shown).

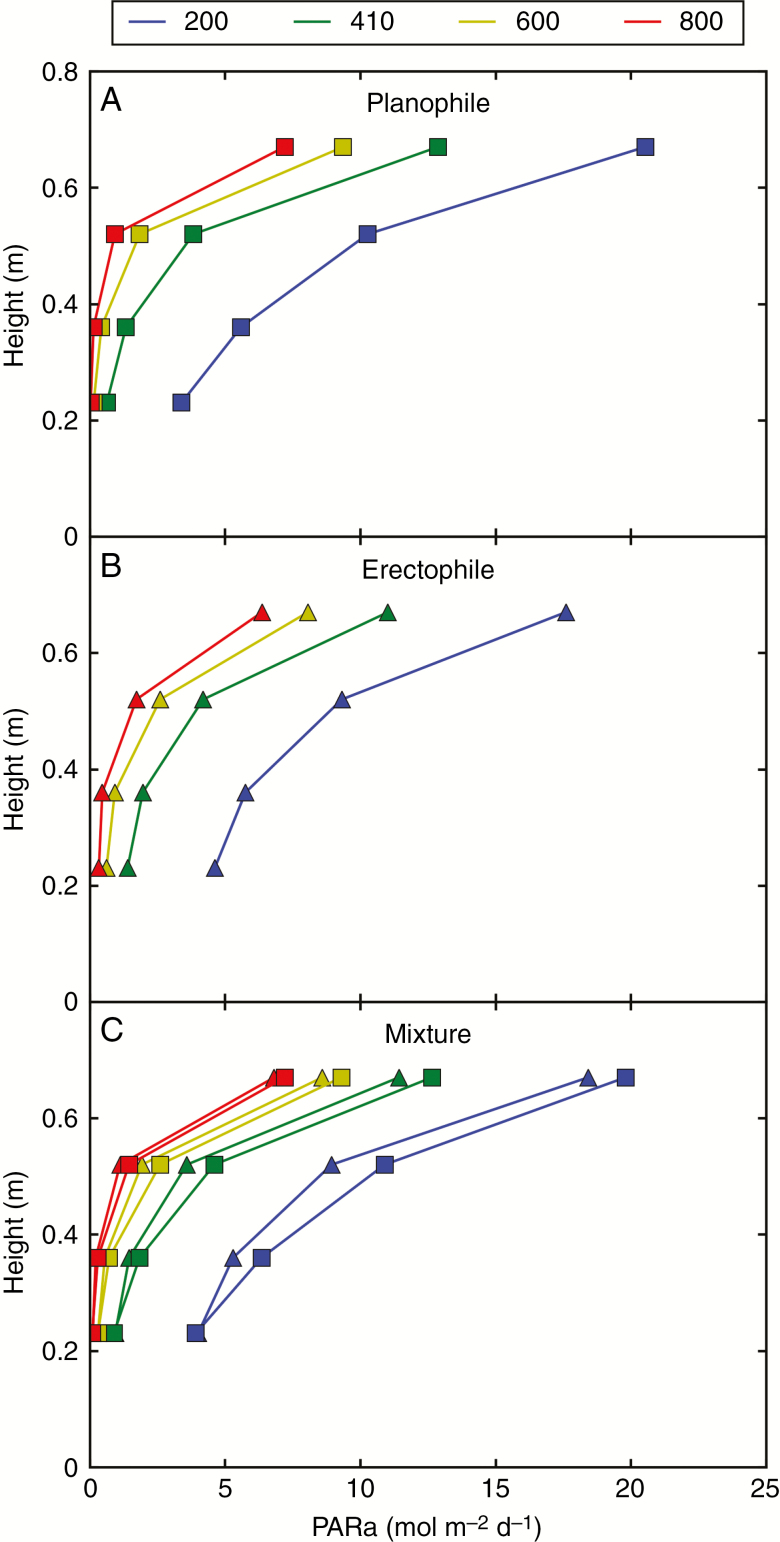

To conclude, the hourly dynamics of absorbed PAR varied in a complex way according to the cropping system (pure or mixture), radiation regime, organ, leaf inclination and culm density. In order to show how these differences are integrated over time and space, we analysed the vertical gradient of absorbed PAR by laminae when integrated over a day. Because the results were very similar between the radiation regimes, the results in Fig. 6 are only shown for diffuse conditions. The transmission of PAR to the lower layers of the canopy was higher in the erectophile pure stands (Fig. 6B) than in planophile stands (Fig. 6A). Indeed, at medium and high densities, a better penetration of light improving photosynthesis of lower layers is a key feature expected from the erectophile trait. The simulations showed that in the theoretical mixed stands, the higher penetration of light resulting from the presence of erectophile plants mainly benefits the planophile plants (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Vertical profiles of absorbed PAR by laminae integrated over 1 d (under diffuse radiation only). Profiles are shown for planophile and erectophile plants in pure stands (A and B, respectively) and in the mixture (C) at four culm densities (D200, D410, D600 and D800).

Comparison of absorbed PAR between canopies during the whole post-anthesis period

In interactions with sky conditions and plant architecture, leaf life span also strongly determines the amount of light absorbed by active tissues and thus plant functioning. In order to compare our different theoretical canopies over the whole post-anthesis period (50 d), we present below the cumulated PAR absorbed by photosynthetically active tissues during the post-anthesis period (Table 1). Cumulated absorbed PAR was calculated from the actual hourly incident PAR measured by a meteorological station and different ratios of diffuse radiation, from clear, to actual and overcast sky conditions. These results integrate the diurnal variations of PARa over the post-anthesis period as well as the dynamics of the area of green tissues as simulated by CN-Wheat on ‘average’ culms (see the Materials and Methods). As expected, the main source of variation in cumulated PARa was culm density. As culm density increased from D200 to D800, the LAI increased proportionally (from 2.14 to 8.57) and the cumulated PARa per culm decreased approximately inversely from 7.675 to 1.694 mol. Planophile plants absorbed more PAR than erectophile plants in all treatments (8.2 to 9.1 % in D200 and 2.8 to 5.6 % in D800). In our theoretical canopies, cumulated PARa was slightly higher in mixed stands than in pure stands (0.47 % in D200 to 0.91 % in D800). Despite the effect of sky conditions on hourly dynamics of PARa (Figs 4 and 5), the total amount of PAR absorbed during the whole post-anthesis period was very similar under diffuse, actual and clear skies. We only observed that diffuse radiation resulted in higher PARa compared with direct radiation, but the difference decreased with higher plant density (from 1.70 to –0.06 % at D200 and D800, respectively). In addition, diffuse sky lowered the advantage of planophile plants over erectophile plants for PARa in pure stands while it increased it in mixtures. These results were obtained for ‘average’ culms mimicking the behaviour of homogeneous canopies; in order to illustrate the variation of total PARa within each canopy, we also simulated the dynamics of PARa for each plant of sub-samples of ten culms (Supplementary Data Table SI1). The effects of culm density and sky conditions on total PARa were very similar to those simulated for ‘average’ culms. In contrast, the ratio of dominance between planophile and erectophile plants was highly variable among the canopies, so that these simulations do not allow the identification of clear trends for the effect of leaf inclination. Supplementary Data Table SI1 shows the variance in the PAR absorbed by individual plants and the confidence intervals estimated on the sub-samples. The large confidence intervals reflect the fact that the size of the sub-samples did not allow buffering for the plant to plant variation in absorbed PAR, as within a same plant type, individual plants can differ greatly from the average in terms of architecture and thus light absorption.

Table 1.

Cumulated absorbed PAR (mol) per culm during the post-anthesis period

| D200 | D410 | D600 | D800 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stand | Leaf inclination | Clear sky | Actual sky | Diffuse sky | Clear sky | Actual sky | Diffuse sky | Clear sky | Actual sky | Diffuse sky | Clear sky | Actual sky | Diffuse sky |

| Pure | Mean | 7.606 | 7.622 | 7.745 | 3.552 | 3.555 | 3.600 | 2.342 | 2.340 | 2.355 | 1.686 | 1.684 | 1.688 |

| Planophile | 7.936 | 7.953 | 8.074 | 3.665 | 3.666 | 3.699 | 2.415 | 2.410 | 2.411 | 1.734 | 1.731 | 1.724 | |

| Erectophile | 7.277 | 7.290 | 7.415 | 3.439 | 3.444 | 3.501 | 2.269 | 2.271 | 2.299 | 1.637 | 1.637 | 1.652 | |

| Mixture | Mean | 7.649 | 7.658 | 7.774 | 3.579 | 3.585 | 3.628 | 2.360 | 2.355 | 2.372 | 1.704 | 1.701 | 1.699 |

| Planophile | 7.978 | 8.006 | 8.144 | 3.713 | 3.723 | 3.779 | 2.436 | 2.433 | 2.468 | 1.728 | 1.725 | 1.724 | |

| Erectophile | 7.320 | 7.310 | 7.404 | 3.446 | 3.447 | 3.477 | 2.284 | 2.278 | 2.276 | 1.679 | 1.677 | 1.675 | |

The simulations were performed on planophile and erectophile plants submitted to either clear, actual (i.e. from meteorological data) or diffuse sky conditions in pure and mixed stands of different densities (D200, D410, D600 and D800).

C acquisition

Using the CN-Wheat model on ‘average’ culms, we assessed how the differences in total absorbed PAR affected the assimilation of C during the post-anthesis period (Table 2). Gross C assimilation ranged from approx. 55 mmol of CO2 per culm at D800 to 244 mmol per culm at D200. At all investigated densities and sky conditions, C assimilation was slightly higher in mixed stands than in pure stands (approx. 0.7 %, as seen above for PARa). Planophile plants accumulated more C than erectophile plants; the difference increased with decreasing plant densities, from approx. 2 % at D800 to 6.7 % at D200. Regarding the effect of sky conditions, C assimilation was higher for overcast conditions than under actual and clear sky conditions (except for mixed erectophile plants at D200).

Table 2.

Gross C assimilated (mmol) per culm cumulated over the post-anthesis period

| D200 | D410 | D600 | D800 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stand | Leaf inclination | Clear sky | Actual sky | Diffuse sky | Clear sky | Actual sky | Diffuse sky | Clear sky | Actual sky | Diffuse sky | Clear sky | Actual sky | Diffuse sky |

| Pure | Mean | 228.91 | 229.32 | 232.20 | 110.28 | 110.70 | 113.27 | 74.74 | 74.84 | 76.35 | 55.04 | 55.04 | 56.29 |

| Planophile | 236.34 | 237.07 | 240.54 | 112.22 | 112.56 | 115.12 | 75.51 | 75.61 | 76.87 | 55.45 | 55.39 | 56.48 | |

| Erectophile | 221.48 | 221.57 | 223.85 | 108.34 | 108.84 | 111.43 | 73.97 | 74.08 | 75.82 | 54.63 | 54.68 | 56.11 | |

| Mixture | Mean | 230.02 | 230.22 | 233.17 | 111.11 | 111.55 | 113.87 | 75.41 | 75.56 | 76.98 | 55.64 | 55.60 | 56.68 |

| Planophile | 236.25 | 237.70 | 243.60 | 114.15 | 114.99 | 118.68 | 76.81 | 77.14 | 79.96 | 56.23 | 56.23 | 57.94 | |

| Erectophile | 223.78 | 222.75 | 222.75 | 108.08 | 108.12 | 109.05 | 74.01 | 73.99 | 74.00 | 55.06 | 54.97 | 55.42 | |

The simulations were performed on planophile and erectophile plants submitted to either clear, actual (i.e. from meteorological data) or diffuse sky conditions in pure and mixed stands of different densities (D200, D410, D600 and D800).

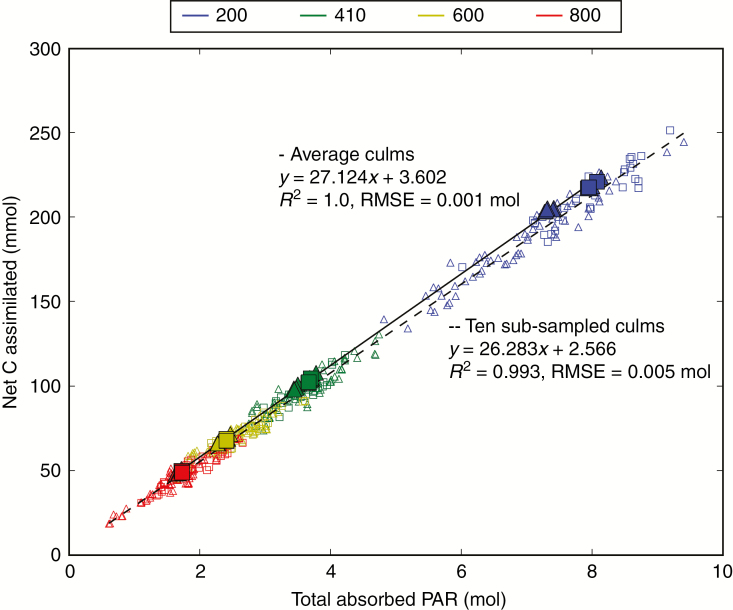

We investigated the relationship between the cumulated PAR absorbed (Table 1) and the net C assimilation, calculated as the difference between gross photosynthesis (Table 2) and respiration of photosynthetic tissues as determined by CN-Wheat (Barillot et al., 2016a). This relationship was investigated for CN-Wheat run either on ‘average culms’ or on each culm of the sub-samples mentioned previously. A linear relationship between PARa and C assimilation, encompassing all plant types, density and sky conditions, emerged from the model (Fig. 7). Moreover, the relationship for the ‘average culms’ only slightly differed from those on individual culms, with yields of approx. 0.027 and approx. 0.026 mol of C per mol of PAR, respectively. The y-intercept of the ‘average culms’ was, however, 28.76 % of that calculated for individual culms. It is striking that such a high degree of linearity emerged from the model, especially at the scale of individual plants, despite the non-linear equations implemented in the photosynthesis calculation and other model components (e.g. respiration, N partitioning and leaf life span). In addition, this result shows that to a large extent, the behaviour predicted for the average plant can be transposed to individuals.

Fig. 7.

Relationships between the cumulated absorbed PAR and cumulated assimilated C per culm over the post-anthesis period for culm densities D200, D410, D600 and D800. Results are presented for planophile (squares) and erectophile (triangles) plants. Filled symbols represents the results obtained on ‘average culms’ and the open symbols those for the sub-sample of ten culms. A linear regression (straight line) was fitted among all treatments.

Dynamic of the green area of laminae in relation to protein concentration

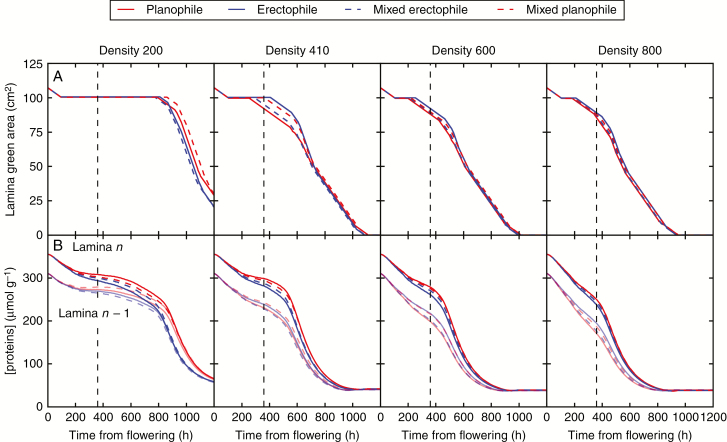

Leaf life span is illustrated in Fig. 8 along with the dynamic of their protein content. Results were very similar among the different sky conditions and are therefore presented for diffuse radiation only. The simulations showed a drastic decrease in lamina green area resulting from metabolite remobilization towards the growing grain (Fig. 8A). The decrease started later at low densities than at high densities, as expected from the differences in PAR absorption and photosynthesis (Tables 1 and 2). Combining the dynamics of photosynthetic green area with the amount of absorbed PAR over the grain-filling period revealed that light interception efficiency (LIE, i.e. the fraction of incoming light intercepted by photosynthetically active tissues) was 0.75 for D200, 0.81 for D410, 0.79 for D600 and 0.77 for D800. The non-monotone relationship between LIE and culm density resulted from a balance between the initial LAI at flowering (highest for D800) and leaf life span which was longer at D200 as plants kept some green tissues until the end of the simulation.

Fig. 8.

Dynamics of total lamina green area (A) and protein concentration (B) in the lamina of the flag leaf (lamina, n) and the penultimate leaf (lamina, n – 1; shaded lines) from anthesis to maturity at four culm densities (D200, D410, D600 and D800). The results are shown for planophileand erectophile plants in pure and mixed stands. The vertical dashed line represents the beginning of the rapid filling stage of grains. Results are shown only for diffuse sky conditions.

In most of the pure stands (except at D200), lamina death started later for erectophile plants than for planophile plants. The model simulated the opposite behaviour in all mixed stands. A more detailed analysis revealed that these differences were related to the life span of the laminae located in the bottom of the canopy: lower laminae remained green longer in pure erectophile stands than in planophile stands and conversely in the mixture (data not shown). At high densities, the differences between canopies tended to decrease. The LIE over the grain-filling period was higher for planophile plants than for erectophile plants, especially at low densities (8 % higher at D200, 5 % at D800). Similar patterns were observed from the simulations performed on the sub-samples of 10 culms (Supplementary Data Fig. SI2).

Organ senescence is a complex process that involves signals and mechanisms of various natures (e.g. ageing, trophic and water status, and hormones). In CN-Wheat (Barillot et al., 2016a), we assumed tissue death to be regulated by protein concentration (see the Materials and Methods) and therefore by the processes involved in protein turnover (nitrate reduction, amino acid and cytokinin concentrations). Protein concentration in the lamina of the flag leaf (lamina n) and the penultimate leaf (lamina, n – 1) decreased from anthesis until reaching a plateau at maturity (Fig. 8B). The depletion of proteins started earlier and was faster at high densities, and thus led to an earlier senescence than at low densities. The amount of remaining proteins that were not remobilized at the end of grain filling was similar between canopies. In addition, the model predicted a vertical gradient of protein concentration, steeper in planophile compared with erectophile plants, which is in agreement with the well-known light–N relationship (e.g. Bertheloot et al., 2012). However, at D200, lamina n and n – 1 showed similar protein concentrations from 600 h post-flowering, which is expected to result from the high penetration of light into the lower layers of the canopy, leading to the synthesis of sufficient C skeletons for protein synthesis and thus a delayed senescence. From D410 to D800, protein concentration in the lamina n of pure planophile plants was higher than that of erectophile plants, reflecting the higher absorption of PAR (Fig. 6). The opposite situation was observed for the lower leaves: the better penetration of light allowed by the erectophile stature resulted in a higher concentration of proteins in lower leaves of pure erectophile stands than that observed in pure planophile plants. The life span of these lower leaves explained why the total lamina area remained green longer in pure erectophile plants than in planophile plants.

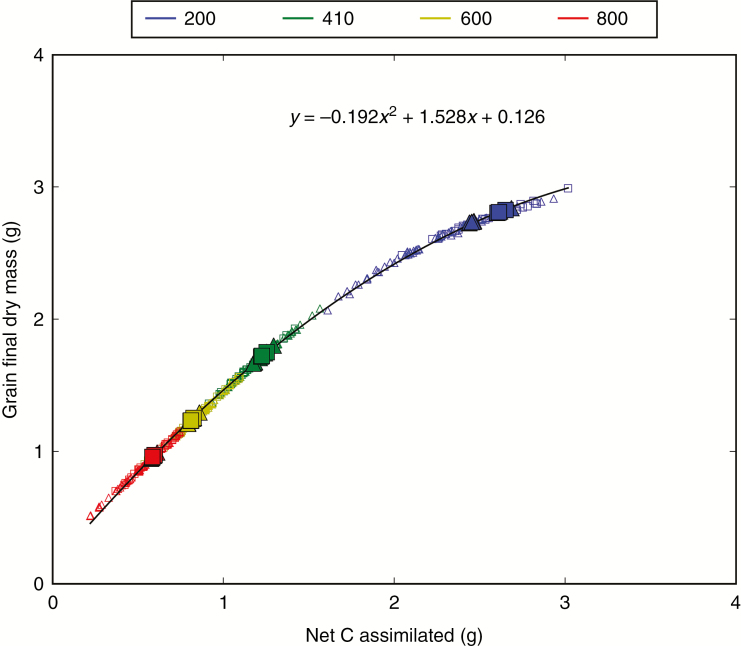

Dynamic of grain filling and C remobilization from vegetative organs

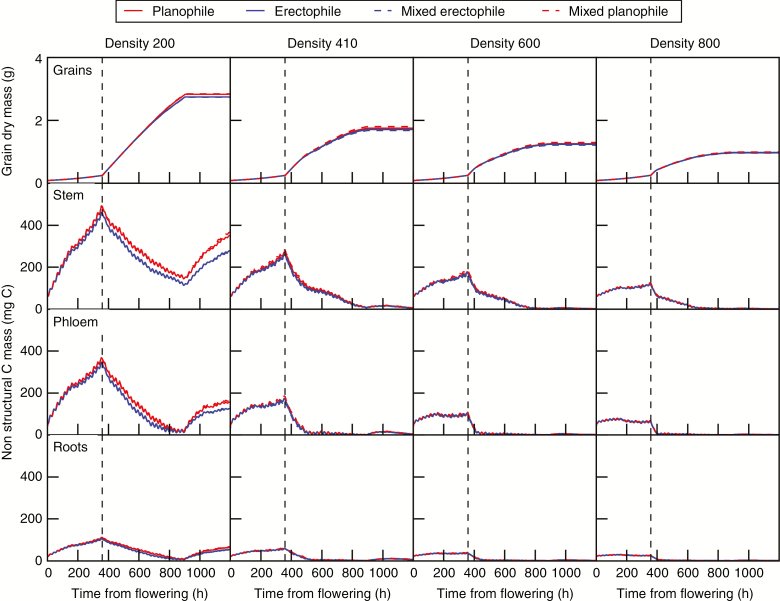

Finally, the CN-Wheat model was used to assess how the observed differences in light absorption, C assimilation and leaf life span affected the dynamic of grain filling (Fig. 9). Grain dry mass followed sigmoidal-like kinetics, reaching contrasting final values according to culm densities, from 0.94 g at D800 to 2.83 g at D200. At the square metre scale, grain production therefore ranged from 752 g m–2 at D800 to 566 g m–2 at D200. In the static canopies used here, leaf inclination variation resulted in a final grain dry mass slightly higher for planophile plants than for erectophile plants (approx. 3 %), the difference being accentuated in the mixtures compared with pure stands. No significant differences (approx. 0.4 %) in the final dry mass of grains were found between pure and mixed stands (mean = 1.67 g). Similar conclusions can be drawn from the simulations performed on individual plants (Supplementary Data Fig. SI2), with, however, a large variability at D410 and D800. The final grain dry mass predicted by the model was closely related to the cumulated amount of C assimilated per culm whatever the density, cropping system, sky conditions and leaf inclination (Fig. 10), and encompassing both ‘average’ culm and individual plant simulations. The relationship was curvilinear, with a slope close to 1:1 for assimilated C below approx. 1.5 g per plant, while higher values of assimilated C, which occurred mainly at D200, resulted in a lower fraction of assimilated C contributing to grain production.

Fig. 9.

Dynamics of grain mass and non-structural carbohydrate mass in the stem (sum of internodes, sheaths and peduncles), phloem and roots from anthesis. Results are shown for plants submitted to diffuse sky conditions. Planophile and erectophile plants are represented by solid lines in pure stands and dashed lines in mixtures. As the phloem is botanically present in each organ, non-structural C shown for stem and roots includes a contribution from the phloem according to their respective structural mass and area. The vertical dashed line shows the beginning of the rapid filling stage of grains.

Fig. 10.

Relationship between the mass of C accumulated in culms during the post-anthesis period and the final grain dry mass for D200, D410, D600 and D800. Planophile plants are represented by squares and erectophile plants by triangles. Filled symbols represent the results obtained on ‘average culms’ and the open symbols those for the sub-sample of ten culms. The dotted line represents the second-order polynomial regression among all treatments (y = –0.192x2 + 1.528x + 0.126).

Remobilization of non-structural carbohydrate mass (sum of sucrose, starch and fructan mass) from stem organs (sum of sheaths, internodes and peduncles), the common pool of the model named ‘phloem’ and the roots is presented in Fig. 9 (for the sake of clarity, results are only shown for the stands under diffuse sky conditions). Although absolute values differed between organs, the mass of non-structural carbohydrates followed similar kinetics in stems, phloem and roots. First, carbohydrate mass increased until the beginning of the rapid filling phase of grains. From that stage, the grains became a strong competitor for the phloemic C, thus leading to its depletion. Consequently, the unloading of C towards roots decreased while the photosynthetic organs increased the loading of sucrose and started remobilizing their storage of C which is mainly under the form of fructans accumulated in stems (Schnyder, 1993; Gebbing, 2003; Barillot et al., 2016b). At D600 and D800, the decrease in carbohydrate ultimately resulted in a total depletion in all plant compartments, meaning the death of the culm. At D200 and to a lesser extent at D410, the simulations showed an increase of non-structural carbohydrates after the end of grain filling (t = 900). In these virtual canopies, laminae were not fully senesced at completion of grain filling and therefore maintained a photosynthetic activity (i.e. the model predicted a stay-green behaviour).

The overall mass of non-structural carbohydrates decreased with increasing density. The maximum amount of non-structural carbohydrates varied approximately inversely to plant density: the ratio between that at D800 and that at D200 was approx. 1:3.7 for stem, 1:5 for phloem and 1:3.6 for roots. Also, the time when carbohydrates reached their minimum in the phloem was delayed in lower densities, from approx. 400 to 860 h post-anthesis at D800 and D200, respectively. The maintenance of a photosynthetic activity after completion of grain filling explains the curvilinear relationship between assimilated C and grain mass (Fig. 10). A higher accumulation of carbohydrates was observed for planophile plants compared with erectophile plants at low densities. At high densities, the results showed no significant difference of non-structural carbohydrate accumulation between planophile and erectophile plants or between pure and mixed stands.

DISCUSSION

Here, we describe a comprehensive and mechanistic FSPM taking into account plant architecture, the primary metabolism of C and N, and environmental factors (mainly light, temperature, humidity, wind and soil N). For this purpose, we developed an original simulator coupling CN-Wheat, ADEL-Wheat and Caribu models in the OpenAlea platform by using the multi-scale topological data-structure MTG as a central layer for indirect communication among models. We have illustrated the behaviour of this new FSPM by simulating the functioning of theoretical wheat canopies in which erectophile and planophile plants were arranged in pure and mixed stands.

Leaf inclination is among the major traits affecting light distribution within the canopy (Sinoquet and Caldwell, 1995) and is therefore a target for cereal breeding programmes. An erectophile stature of the upper leaves is considered as a favourable trait in conventional agriculture because of the high penetration of light into the deeper layers of the canopy, thus improving leaf photosynthesis, leaf life span and N economy (Zhu et al., 2010). Erect cultivars are therefore expected to allow dense plant packing, avoiding saturation of photosynthesis and thermal stresses under high irradiance. Modern wheat genotypes have been selected for erect or semi-erect stature (Reynolds et al., 2012), but even though various experimental comparisons showed an effect of leaf inclination on leaf mass per unit area, number of tillers and individual grain weight, they failed to find a significant difference in yield (e.g. Austin et al., 1976; Araus et al., 1993; Monneveux et al., 2004). The expected benefits of an upright stature have been highlighted in tropical climates, and this trait is part of the definition of modern rice ideotypes (Cheng et al., 2007; Peng et al., 2008; Yuan, 2008). These conclusions are also supported by model simulations of photosynthesis using 3-D reconstructions of the rice canopy (Song et al., 2013; Burgess et al., 2017). However, the specific benefit brought by an upright leaf stature remains challenging to assess experimentally, because cultivars often differ by multiple traits (e.g. leaf growth, tillering, height or precocity) and by modelling approaches because of the simplifications involved in the modelling exercise. One difficulty is the entanglement between light and N profiles within a canopy, with consequences on the photosynthesis response to light and leaf life span for instance. Using a mechanistic approach of C–N interactions would allow us to take a step further in the analysis. In the present study, we analysed how the developed FSPM can help to decipher such interactions, by providing access to critical variables such as resource acquisition and allocation, internal metabolic concentrations, green leaf area and grain filling during the post-anthesis period. We considered both homogenous and complex canopies resulting from the mixture of erectophile and planophile plants.

First, we observed contrasting daily dynamics of light absorption between canopies and sky conditions. Our simulations highlighted that chaff absorbed a large fraction of the incoming light, from approx. 34 % at D200 to 57 % at D800 of the PAR absorbed by the whole culms over the post-anthesis period. This attenuated the differences between erectophile and planophile plants, especially at high densities. Similarly to erect leaves, chaff absorbed more light at low solar elevation in clear sky conditions. This implies that the photosynthetic activity of chaff mainly occurs at grazing angles, i.e. in the morning and late afternoon. Because the temperatures are lower during these periods of the day, our results can contribute to explain why some studies reported that chaff have a better photosynthetic performance and a higher water content than flag leaves under water stress (Tambussi et al., 2005). Under a clear sky, the simulations showed a temporal complementarity between planophile and erectophile plants, the upper leaves of the former absorbing more PAR for vertical angles while those of the latter were more efficient for grazing angles, as demonstrated by several theoretical studies conducted at the canopy scale (e.g. Goudriaan, 1988; Kimes, 1991; Chen et al., 1994). Under diffuse conditions, the daily dynamics became independent of canopy structure (de Wit, 1965), and a slightly higher fraction of the incoming PAR was absorbed in almost all virtual stands. Indeed, overcast conditions imply a high contribution of light coming from low zenith angles, which is highly absorbed because the longer optical path through the canopy favours interception.

The comprehensive description of C and N metabolism in the CN-Wheat model allowed us to assess the effect of the complex spatiotemporal variations of absorbed PAR on the functioning of the culm over the post-anthesis period. Indeed, the distribution of light and leaf life span interactively determine the cumulated absorbed PAR. In our theoretical canopies, we showed that plants that only differ in leaf inclination absorbed slightly more light with planophile leaves during the post-anthesis period, whatever the culm density and sky conditions (Table 1). This was the case in particular in the mixtures, where planophile plants took advantage of the higher penetration of light in the lower layers of the canopy. A slight dominance of planophile plants was observed for all densities, although light sharing was more balanced at high densities. These results show that under certain conditions, the erectophile behaviour can be associated with a competitive handicap promoting the growth of the planophile component.

Several studies in the literature have promoted the use of erectophile cultivars as they could improve light penetration in the canopy and thus increase the photosynthetic activity and life span of lower leaves (Austin et al., 1976; Monneveux et al., 2004). Interestingly, at leaf scale, our simulations in pure stands at intermediate and high densities (D410, D600 and D800) are consistent with these observations as they show that more light was reaching the lower layers of the erected plants compared with planophile plants (lamina n – 1, Fig. 4). The model also predicted a delayed lamina death for erectophile plants compared with planophile plants in the pure stands (Fig. 8). However, integrating the present results at canopy scale using a model of C and N economy over the whole post-anthesis period and for different planting densities shows that the sole effect of leaf inclination only slightly affected total C assimilation and grain yield, which was approx. 3 % higher for planophile plants. These small differences observed between plants that only differ in leaf inclination was also discussed in previous works (e.g. Chen et al., 1994; Barillot et al., 2014). Nevertheless, the present results were obtained while assuming that erectophile and planophile plants had the same leaf area at flowering, independently of the stand density, whereas it is likely that the higher light penetration in erectophile stands during shoot development (i.e. before flowering)) would have led to a higher LAI at flowering compared with planophile stands. Also, our simulations did not consider the impact of stresses, and we may think that high temperatures or water stresses have less impact on erectophile plants because of the lower absorption of light by the upper leaves around mid-day when planophile leaves may experience water deficit and/or impaired photosynthesis.

At canopy scale, CN-Wheat simulations showed that the photosynthetic efficiency was approx. 0.026 mol of C assimilated per mol of PAR absorbed. This linear relationship between C net assimilation and cumulated absorbed PAR encompassed all canopies, whatever the cropping system and leaf posture. In the present simulations, we covered a large range of situations, from shaded organs at the bottom of the canopy to highly irradiated organs such as chaff and flag leaves, but it is likely that active radiation absorption was generally in the linear zone of the photosynthetic response to light. Thus, such a linear relationship may be expected at the organ scale, but the striking aspect is that this relationship was also valid at the canopy scale after integration over the post-anthesis period. This emergent property was not straightforward given the non-linear models used to simulate photosynthesis and its relationship to the N profile, tissue death, respiration and C fluxes among culm organs (Farquhar et al., 1980; Cannell and Thornley, 2000; Thornley and Cannell, 2000; Barillot et al., 2016a). Moreover, this unique relationship found for both pure and mixed stands suggests that the concept of radiation use efficiency (RUE; Monteith, 1977) could also be used for estimating biomass accumulation of individual plants in complex canopies. For the present simulations, mean daily RUEs varied between 0.57 at D800 and 0.82 at D200 (Supplementary Data Table SI3), which is consistent with the literature, e.g. Calderini et al. (1997) reported RUEs between 0.37 and 1.02 in different wheat cultivars during the post-anthesis period. Nevertheless, these results mean that in our theoretical scenario culms at D200 were 30 % more efficient in converting light into aerial biomass than those at D800. A preliminary analysis of the results showed that for most of the time, daily RUEs were very similar between densities, except on days of low irradiation (see Supplementary Data Fig. SI3). This was the case at the beginning of the rapid grain-filling phase, where PARa and photosynthesis were strongly reduced, thus decreasing sucrose concentration in the phloem (Fig. 9). As a consequence, the accumulation of above-ground dry mass stops and even becomes negative at high densities because of the respiration costs, thus strongly decreasing the daily RUE. Interestingly, such negative conditions of low light had a stronger impact on plants with a low trophic status, i.e. those with low phloemic concentration of sucrose (e.g. at D800). This opens up the view that the present model could help in exploring under which conditions the RUE does vary, e.g. according to light conditions, but also N fertilization, temperature (Louarn et al., 2008) or under contrasting root/shoot ratios.

We also found that the final dry mass of grains followed the cumulated assimilation of C during the post-anthesis period with a curvilinear relationship, highlighting the role of leaf life span. All other things being equal, we found that during the post-anthesis period, pure stands made up of planophile leaves produced a slightly higher final grain mass than erectophile stands (approx. 3 %). In the present mixtures, the increase in grain production estimated for the planophile plants was mainly counterbalanced by the loss estimated for the erectophile plants, thus leading to a slight overyielding compared with pure stands (overyield <0.4 % for a gain of 0.8 % in absorbed PAR). This result is consistent with the literature that reports non-significant or small yield advantages for wheat mixtures in unstressed conditions (for a review, see Smithson and Lenné, 1996). The evidence which promotes the interest of wheat mixtures lies in a better stability against environmental stresses and a higher resistance to diseases (Smithson and Lenné, 1996; Mundt, 2002) rather than in a higher efficiency to capture or use of resources.

The theoretical canopies defined here were used for illustrating the model behaviour; however, they present some approximations whose impacts on the results must be outlined. First, our simulations showed that diffuse radiation slightly increases PAR absorption and therefore final grain mass (+1.8 %) compared with direct radiation. However, overcast conditions usually result in a significant decrease in incident solar radiation. Obviously, accounting for a decrease of incident light would have resulted in very different C and N balances. The sky conditions used here were aimed at rather testing the sensitivity of the FSPM to the sky representations as there are large differences in computation time between an accurate (direct + diffuse radiation) or a simplified (diffuse radiation only) description of the sky conditions (the latter being much faster). Secondly, one of the main drawbacks of the model lies in the computation times required for solving the differential equations describing the variations of metabolite concentrations within a plant. This led us to define a strategy combining the simulation for ‘average culms’ and sub-samples of ten individual culms. The major trends for PAR absorption (Supplementary Data Table SI1), leaf life span and grain mass (Supplementary Data Fig. SI2) calculated for individual plants were consistent with the results obtained for ‘average’ culms, and the emerging relationships between these integrative variables were nearly identical for individual and for averaged culms. On the other hand, the inter-plant variability resulted in large confidence intervals for the estimate of variables at the stand level from the sub-samples of individual culms, which hampered the comparison between erectophile and planophile plants. We believe that simulating a few hundred individual plants would widen the possibility for use of the model and we expect that significant reductions in the computation time are possible by optimizing the code, e.g. defining matrix representation of the differential equations, and taking advantage of the multiple cores. For instance, this will allow a full analysis of the numerical errors to be performed in order to assess the significance of the small differences found between pure stands and mixtures and between planophile and erectophile plants. Finally, the present study was restricted to the post-anthesis period during which plant architecture could be assumed to be static except for leaf senescence. In these conditions, plant architecture is an input to the model whatever the previous mechanisms that determined it. An obvious drawback when investigating the impact of a specific trait is that the considered trait (leaf inclination here) would generally impact plant architecture at flowering, which means that agronomic transposition of the results must be done with sufficient caution. On the other hand, the method allows analysis of the specific impact of the trait during the period of interest, which would be difficult or impossible to characterize experimentally. Despite the limitations mentioned above, we think that the concept presented here can help in understanding plant behaviours such as the relationships between light absorption, C assimilation and grain filling. These emergent properties, observed for both pure and mixed stands, highlight the major role of leaf life span on plant functioning during grain filling. One of the key features of the present FSPM therefore lies in the mechanistic approach used to simulate leaf life span based on the multiple interactions between plant architecture, light absorption and the metabolism of C and N. The approach proposed here to account for leaf life span is based on several complex processes related to C and N metabolism which were formalized according to experimental evidence, but we lack data to assess our hypotheses in a large range of conditions. Nevertheless, the present model represents actual plant state variables and biological processes that are experimentally accessible. One of the advantages of such FSPMs is therefore to help in designing experiments intended to assess the model behaviour and consequently improve our understating of plant functioning.

Conclusions

Our work proves that this approach can help to decipher the interactions between environmental factors (e.g. light and N) and plant functioning (e.g. resource acquisition and allocation) in heterogeneous crops and provides a framework that unifies the analysis of simple and complex canopies. The model presented here constitutes a step forward to more comprehensive and mechanistic FSPMs. Further developments are aimed at accounting for the water status and the processes driving the plasticity of plant morphogenesis (leaf growth and tillering). Such comprehensive FSPMs will offer an unmatched possibility to assess processes of interest (e.g. resource acquisition and allocation, leaf area dynamics) and identify rules for assembling species or varieties in high-performance intercropping systems.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Table SI1: cumulated absorbed PAR (mol) per culm during the post-anthesis period. Figure SI2: dynamics of lamina green area and grain dry mass simulated from a sub-sample of ten plants with random leaf azimuth and variable positions on the row. Table SI3: absorbed PAR (PARa), cumulated dry mass and radiation use efficiency (RUE) of the canopies from anthesis to the end of grain filling. Figure SI3: daily increment of dry mass, absorbed PAR and RUE for the wheat canopies at the four densities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research leading to these results has received funding through the AGROBIOSPHERE programme of the National Research Agency (Wheatamix project ANR-13-AGRO-0008) and through the Investment for the Future programme managed by the National Research Agency (BreedWheat project ANR-10-BTBR-03) This funding originates from the French government, from FranceAgriMer and from French Funds to support Plant Breeding (FSOV).

LITERATURE CITED

- Araus JL, Reynolds MP, Acevedo E. 1993. Leaf posture, grain yield, growth, leaf structure, and carbon isotope discrimination in wheat. Crop Science 33: 1273–1279. [Google Scholar]

- Austin RB, Ford MA, Edrich JA, Hooper BE. 1976. Some effects of leaf posture on photosynthesis and yield in wheat. Annals of Applied Biology 83: 425–446. [Google Scholar]

- Balduzzi M, Binder BM, Bucksch A, et al. 2017. Reshaping plant biology: qualitative and quantitative descriptors for plant morphology. Frontiers in Plant Science 8:117. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballaré CL, Casal JJ. 2000. Light signals perceived by crop and weed plants. Field Crops Research 67: 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Barillot R, Louarn G, Escobar-Gutiérrez AJ, Huynh P, Combes D. 2011. How good is the turbid medium-based approach for accounting for light partitioning in contrasted grass–legume intercropping systems? Annals of Botany 108: 1013–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barillot R, Escobar-Gutiérrez AJ, Fournier C, Huynh P, Combes D. 2014. Assessing the effects of architectural variations on light partitioning within virtual wheat–pea mixtures. Annals of Botany 114: 725–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barillot R, Chambon C, Andrieu B. 2016a. CN-Wheat, a functional–structural model of carbon and nitrogen metabolism in wheat culms after anthesis. I. Model description. Annals of Botany 118: 997–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barillot R, Chambon C, Andrieu B. 2016b. CN-Wheat, a functional–structural model of carbon and nitrogen metabolism in wheat culms after anthesis. II. Model evaluation. Annals of Botany 118: 1015–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barot S, Allard V, Cantarel A, et al. 2017. Designing mixtures of varieties for multifunctional agriculture with the help of ecology. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 37: 13. [Google Scholar]

- Bertheloot J, Andrieu B, Martre P. 2012. Light–nitrogen relationships within reproductive wheat canopy are modulated by plant modular organization. European Journal of Agronomy 42: 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bird RE, Riordan C. 1986. Simple solar spectral model for direct and diffuse irradiance on horizontal and tilted planes at the earth’s surface for cloudless atmospheres. Journal of Climate and Applied Meteorology 25: 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Braune H, Müller J, Diepenbrock W. 2009. Integrating effects of leaf nitrogen, age, rank, and growth temperature into the photosynthesis-stomatal conductance model LEAFC3-N parameterised for barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Ecological Modelling 220: 1599–1612. [Google Scholar]

- Bucksch A, Atta-Boateng A, Azihou AF, et al. 2017. Morphological plant modeling: unleashing geometric and topological potential within the plant sciences. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 900. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess AJ, Retkute R, Herman T, Murchie EH. 2017. Exploring relationships between canopy architecture, light distribution, and photosynthesis in contrasting rice genotypes using 3D canopy reconstruction. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 734. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderini DF, Dreccer MF, Slafer GA. 1997. Consequences of breeding on biomass, radiation interception and radiation-use efficiency in wheat. Field Crops Research 52: 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Cannell MGR, Thornley JHM. 2000. Modelling the components of plant respiration: some guiding principles. Annals of Botany 85: 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chelle M, Andrieu B. 1998. The nested radiosity model for the distribution of light within plant canopies. Ecological Modelling 111: 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Chelle M, Andrieu B, Bouatouch K. 1998. Nested radiosity for plant canopies. The Visual Computer 14: 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Chen SG, Shao BY, Impens I, Ceulemans R. 1994. Effects of plant canopy structure on light interception and photosynthesis. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer 52: 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S-H, Cao L-Y, Zhuang J-Y, et al. 2007. Super hybrid rice breeding in China: achievements and prospects. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 49: 805–810. [Google Scholar]

- DeJong TM, Da Silva D, Vos J, Escobar-Gutiérrez AJ. 2011. Using functional–structural plant models to study, understand and integrate plant development and ecophysiology. Annals of Botany 108: 987–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers JB, Vos J, Yin X, Romero P, van der Putten PEL, Struik PC. 2010. Simulation of wheat growth and development based on organ-level photosynthesis and assimilate allocation. Journal of Experimental Botany 61: 2203–2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Caemmerer S von, Berry JA. 1980. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149: 78–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourcaud T, Zhang X, Stokes A, Lambers H, Körner C. 2008. Plant growth modelling and applications: the increasing importance of plant architecture in growth models. Annals of Botany 101: 1053–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier C, Andrieu B. 1999. ADEL-maize: an L-system based model for the integration of growth processes from the organ to the canopy. Application to regulation of morphogenesis by light availability. Agronomie 19: 313–327. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier C, Andrieu B, Ljutovac S, Saint-Jean S. 2003. ADEL-wheat: a 3D architectural model of wheat development. In: Hu B-G, Jaeger M, eds. Proceedings PMA03: 2003 International symposium on plant growth modeling, simulation, visualization and their applications. Beijing, China: IEEE Computer Society, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier C, Pradal C, Louarn G, et al. 2010. Building modular FSPM under OpenAlea: concepts and applications. In: 6th International Workshop on Functional-Structural Plant Models. 109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Garin G, Fournier C, Andrieu B, Houlès V, Robert C, Pradal C. 2014. A modelling framework to simulate foliar fungal epidemics using functional–structural plant models. Annals of Botany 114: 795–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garin G, Pradal C, Fournier C, Claessen D, Houlès V, Robert C. 2018. Modelling interaction dynamics between two foliar pathogens in wheat: a multi-scale approach. Annals of Botany 121: 927–940. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcx186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebbing T. 2003. The enclosed and exposed part of the peduncle of wheat (Triticum aestivum) – spatial separation of fructan storage. New Phytologist 159: 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin C, Caraglio Y. 1998. A multiscale model of plant topological structures. Journal of Theoretical Biology 191: 1–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin C, Sinoquet H. 2005. Functional–structural plant modelling. New Phytologist 166: 705–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudriaan J. 1988. The bare bones of leaf-angle distribution in radiation models for canopy photosynthesis and energy exchange. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 43: 155–169. [Google Scholar]

- Hallé F. 1999. Éloge de la plante. Pour une nouvelle biologie. Paris: Seuil/Science ouverte. [Google Scholar]

- Kimes DS. 1991. Radiative transfer in homogeneous and heterogeneous vegetation canopies. In: Myneni RB, Ross J, eds. Photon–vegetation interactions: applications in optical remote sensing and plant ecology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 339–388. [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Zhao C, Huang W, Yang G. 2013. Non-uniform vertical nitrogen distribution within plant canopy and its estimation by remote sensing: a review. Field Crops Research 142: 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Litrico I, Violle C. 2015. Diversity in plant breeding: a new conceptual framework. Trends in Plant Science 20: 604–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louarn G, Faverjon L. 2018. A generic individual-based model to simulate morphogenesis, C–N acquisition and population dynamics in contrasting forage legumes. Annals of Botany 121: 875–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louarn G, Chenu K, Fournier C, Andrieu B, Giauffret C. 2008. Relative contributions of light interception and radiation use efficiency to the reduction of maize productivity under cold temperatures. Functional Plant Biology 35: 885–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malézieux E, Crozat Y, Dupraz C, et al. 2009. Mixing plant species in cropping systems: concepts, tools and models. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 29: 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Monneveux P, Reynolds MP, González-Santoyo H, Peña RJ, Mayr L, Zapata F. 2004. Relationships between grain yield, flag leaf morphology, carbon isotope discrimination and ash content in irrigated wheat. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 190: 395–401. [Google Scholar]

- Monteith JL. 1975. Principles of environmental physics, 4th edn. London: Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Monteith JL. 1977. Climate and the efficiency of crop production in Britain. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 281: 277–294. [Google Scholar]

- Moon P, Spencer DE. 1942. Illumination from a non-uniform sky. Illuminating Engineering Society 37: 707–726. [Google Scholar]

- Müller J, Wernecke P, Diepenbrock W. 2005. LEAFC3-N: a nitrogen-sensitive extension of the CO2 and H2O gas exchange model LEAFC3 parameterised and tested for winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Ecological Modelling 183: 183–210. [Google Scholar]

- Mundt CC. 2002. Use of multiline cultivars and cultivar mixtures for disease management. Annual Review of Phytopathology 40: 381–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S, Khush GS, Virk P, Tang Q, Zou Y. 2008. Progress in ideotype breeding to increase rice yield potential. Field Crops Research 108: 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pradal C, Dufour-Kowalski S, Boudon F, Fournier C, Godin C. 2008. OpenAlea: a visual programming and component-based software platform for plant modelling. Functional Plant Biology 35: 751–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradal C, Fournier C, Valduriez P, Cohen-Boulakia S. 2015. OpenAlea: scientific workflows combining data analysis and simulation. SSDBM ‘15. Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Scientific and Statistical Database Management New York: ACM, 11:1–11:6. [Google Scholar]

- Prusinkiewicz P, Runions A. 2012. Computational models of plant development and form. New Phytologist 193: 549–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds M, Foulkes J, Furbank R, et al. 2012. Achieving yield gains in wheat. Plant, Cell & Environment 35: 1799–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarlikioti V, de Visser PHB, Marcelis LFM. 2011. Exploring the spatial distribution of light interception and photosynthesis of canopies by means of a functional–structural plant model. Annals of Botany 107: 875–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder H. 1993. The role of carbohydrate storage and redistribution in the source–sink relations of wheat and barley during grain filling – a review. New Phytologist 123: 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Sinoquet H. 1993. Modelling radiative transfer in heterogeneous canopies and intercropping systems. In: Varlet-Grancher C, Bonhomme R, Sinoquet H, eds. Crop structure and light microclimate. Paris: INRA Editions, 229–252. [Google Scholar]

- Sinoquet H, Caldwell MM. 1995. Estimation of light capture and partitioning in intercropping systems. In: Sinoquet H, Cruz P, eds. Ecophysiology of tropical intercropping. Paris: INRA Editions, 79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sinoquet H, Cruz P. 1995. Ecophysiology of tropical intercropping. Paris: INRA Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Smithson JB, Lenné JM. 1996. Varietal mixtures: a viable strategy for sustainable productivity in subsistence agriculture. Annals of Applied Biology 128: 127–158. [Google Scholar]

- Song Q, Zhang G, Zhu X-G. 2013. Optimal crop canopy architecture to maximise canopy photosynthetic CO2 uptake under elevated CO2 – a theoretical study using a mechanistic model of canopy photosynthesis. Functional Plant Biology 40: 108–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambussi EA, Nogués S, Araus JL. 2005. Ear of durum wheat under water stress: water relations and photosynthetic metabolism. Planta 221: 446–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DW. 1945. On growth and form. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; /New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Thornley JHM, Cannell MGR. 2000. Modelling the components of plant respiration: representation and realism. Annals of Botany 85: 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Grancher C, Moulia B, Sinoquet H, Russell G. 1993. Spectral modification of light within plant canopies – how to quantify its effects on the architecture of the plant stand. In: Varlet-Grancher C, Moulia B, Sinoquet H, eds. Crop structure and light microclimate. Characterization and applications. Versailles: INRA, 427–452. [Google Scholar]

- Vos J, Evers JB, Buck-Sorlin GH, Andrieu B, Chelle M, de Visser PHB. 2010. Functional–structural plant modelling: a new versatile tool in crop science. Journal of Experimental Botany 61: 2101–2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit CT. 1965. Photosynthesis of leaf canopies. Wageningen: Pudoc. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan LP. 2008. Progress of super hybrid rice breeding. China Rice 1: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X-G, Long SP, Ort DR. 2010. Improving photosynthetic efficiency for greater yield. Annual Review of Plant Biology 61: 235–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.