DTI redefines drug toxicity, identifies hepatotoxic drugs, gives mechanistic insights, predicts clinical outcomes and has potential use as a screening tool.

DTI redefines drug toxicity, identifies hepatotoxic drugs, gives mechanistic insights, predicts clinical outcomes and has potential use as a screening tool.

Abstract

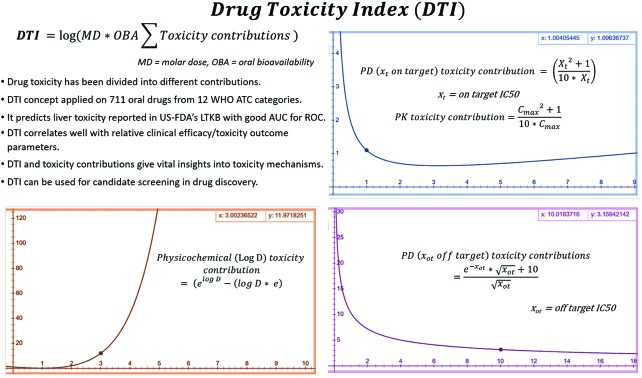

Linear drug toxicity models like therapeutic index (TI), physicochemical rules (rule of five, 3/75), ligand efficiency indices (LEI), ideal pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) profiles are widely used in drug discovery and development. In spite of this, predicting drug toxicity at various stages remains challenging and the overall productivity (<20%) and ultimate benefit to the patients remain low. A simple drug toxicity model, “Drug Toxicity Index” (DTI), is developed here using 711 oral drugs. DTI redefines drug toxicity as scaled biphasic and exponential functions of PD, PK and physicochemical parameters. PD, PK and physicochemical toxicity contributions were estimated from the on and off target IC50, maximum unbound plasma drug concentration (free Cmax), and log D values, respectively. These contributions are then scaled by molar dose and oral bioavailability and the logarithm of the sum of scaled contributions is DTI. Drugs with DTI above the WHO ATC drug category specific average values consistently have toxic profiles, while drugs with DTI below this average are relatively safe. DTI performs better than standard rules for lead optimization, LEI and exposure based TIs in identifying safe and toxic drugs. DTI classifies 392 drugs reported in the US-FDA's Liver Toxicity Knowledge Base (LTKB) with an AUC for ROC curves of 0.91–0.64 for different WHO ATC categories. DTI has been used to predict network meta-analysis results on relative toxicity within/across eight different therapeutic areas. It is useful in understanding PD, PK and physicochemical toxicity contributions and identifying potentially toxic drugs and the toxicity of recently approved drugs. Decision trees are proposed for applying the DTI concept in preclinical drug discovery and clinical trial settings. DTI can potentially reduce failure in drug discovery and might be useful in therapeutic drug monitoring and in xenobiotic and environmental toxicity studies.

1. Introduction

Drug safety is estimated in drug discovery by the measurement of the therapeutic index (TI) and its variants e.g. exposure based therapeutic indices (IC50/Cmax).1,2 But investigational drugs continue to fail in clinical trials due to low safety and efficacy.3,4 TI assumes simplified linear relationships between receptor affinity, maximum unbound plasma drug concentration (Cmax) and toxicity. But high TI does not guarantee safety. For drugs metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP450), estimating TI based on target potencies alone is insufficient. Toxicity may be due to the accumulation in a specific organ/tissue (e.g. bosentan), the co-administration of other drugs affecting ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, elimination and toxicity),5Cmax reaching off target IC50, or the high Cmax required for therapeutic effects, see ref. 1.

A 2D “TI heatmap grid” was developed earlier to compare efficacy and safety data.1 The limitations of this approach are: a lack of a universal TI value, large variations and difficulty of direct comparison across chemical or therapeutic classes. TI is used for risk–benefit assessment of known toxicities and is not applicable to rare and idiosyncratic toxicities. For example, the Valdecoxib TI values for COX-1 are 7 times those for CYP2C19 inhibition, but its toxicity is due to on target activity in cardiomyocytes, seldom considered in TI calculations.1,6 Using the same Cmax value for calculating TI at different doses seems erroneous.2 The major off target effects involve proteins closely related to the therapeutic target, CYP450s, hERG and BSEP activities.1 The use of 44 proteins (from GPCR, ion channel, neurotransmitter transporter, nuclear hormone receptors, AChE, COX, MAO, phosphodiesterase and kinase families) for off target profiling has been recommended.7 Pharmaceutical companies have been screening this protein set for decades, but data for most drugs are not available in the public domain. When such data are available the interpretation of complex TI heatmap grids could still present practical difficulties.

Physicochemical property and toxicity relationships have been extensively reviewed.8,9 Trends between oral bioavailability, drug-like properties and hepatotoxicities, e.g. the RO5,10 3/75, RO3,11 RO2,12 RO2-RM,13 and 4/400 rule,8 have been useful in lead optimization. Typically, compound libraries are filtered using predicted physicochemical properties, and drug-likeness rules, and subjected to biological activity (IC50, Ki, Kd or Km) predictions. Alternatively, high throughput, fragment, focused, physiological or even NMR screening, ligand and/or structure based design approaches can be used to find lead compounds.9,14 Predictions are then tested and structure–activity and/or structure–metabolism relationships are built and an iterative process may lead to candidates suitable for clinical testing. Major challenges are the simultaneous optimization of lead properties for on/off target, metabolic, toxicological, and pharmaceutical (e.g. solubility) issues.15 Current state-of-the-art for lead optimization includes multi-parameter optimization with different forms of predictive modelling, utility functions, weighed desirability and spread design.16 Typically compounds with the highest binding affinity or potency are selected for the further optimization of ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination), solubility, stability and other pharmaceutical properties with the hope that necessary structural changes will modify potency within acceptable limits. Although these methods avoid rigid rules and have improved success rates in lead optimization cycles, they assume a linear relationship between parameter values and desirability. Thus quantitative predictions and differentiating drug toxicity potential within/across therapeutic classes are challenging at this stage.

The effect of Cmax on the observed safety and toxicity of 245 drugs was reported earlier.9Fig. 3 of that reference suggests a non-linear relationship of total Cmax with toxicity, but the relationship was not discussed. Drugs with an average affinity of 10 nM for the target and 30 nM to 1 μM Cmax were considered safe. Wenlock has studied the estimation of Cmax and Cmin for 215 oral drugs.17 Ninety percent of the safe drugs had Cmax below 10.4 μM. Cmax at the non-observable adverse effect level (NOAEL) correlated with Cmax at the maximum dose. A maximum Cmax of 50 μM for oral drugs was suggested, but no lower bound was given. This suggests that for a drug-like molecule, Cmax, Cmin and pharmacologically effective concentration (Ceff) should be minimum. A Cmax/Cmin ≤ 30 is desirable for oral drugs.

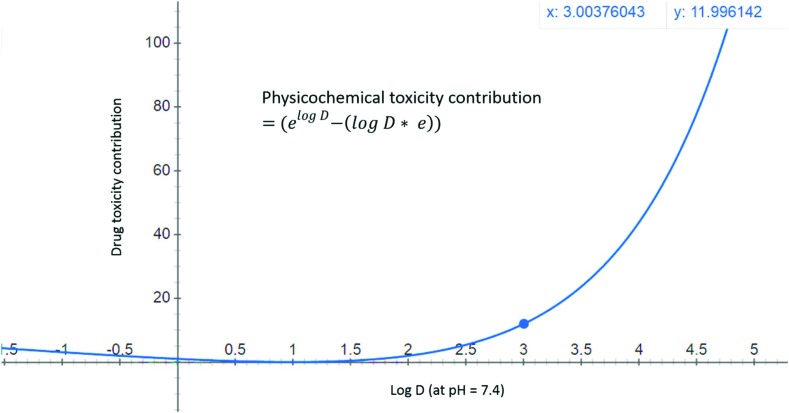

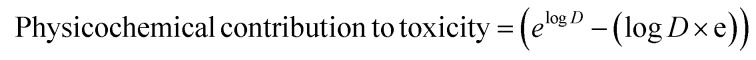

Fig. 3. Physicochemical toxicity of drugs is modelled as an exponential function of log D (at pH = 7.4) values. A compound with a log D value of zero will have a toxicity contribution of 1, while compounds with log D = 1 will have zero physicochemical contribution to toxicity, and candidates with log D > 3 are expected to have a high toxicity contribution (>12 units).

IC50, log P, bioavailability, % plasma protein binding (PPB), molecular weight, dose and Cmax have important roles in drug toxicity. Since oral drugs have molecular weight (∼150–750 Da), daily dose (∼0.1 mg to 1 g), log P (∼–5 to 6), IC50 (on and off target: ∼0.001 to 10 μM), oral bioavailability (0–1), and free Cmax (0.001 to 10 μM), predicting toxicity is a complex problem. Thus a novel method for estimating the clinical toxicity of drugs and combinations based on physicochemical, PD and PK properties is urgently required.

In this paper, drug toxicity is redefined as the logarithmic sum of scaled biphasic and exponential toxicity contributions from the basic in vitro, in vivo and physicochemical parameters, thus giving Drug Toxicity Index (DTI). DTI is a significant advancement as a simple model combining toxicity contribution from different parameters is presented for the first time. DTI values are compared between drugs and categories to estimate relative toxicity potentials. PD, PK and physicochemical contributions to DTI offer scope to gain mechanistic insights into drug toxicity. The DTI concept is applied for understanding drug (liver) toxicity, differentiating drug categories, toxic and safe drugs, and identifying potentially toxic drugs. Decision trees like thinking with potential applications of the DTI concept in various drug discovery phases are presented followed by the limitations of the current approach.

2. Methodology

Data on IC50 (on/off target), Cmax at a specified dose, % plasma protein binding, oral bioavailability, molecular weight, ACD log D, log P for 711 oral drugs were collected and analyzed using a methodology detailed in the ESI PDF file.†

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Pharmacodynamic (PD) toxicity and on target affinity (potency)

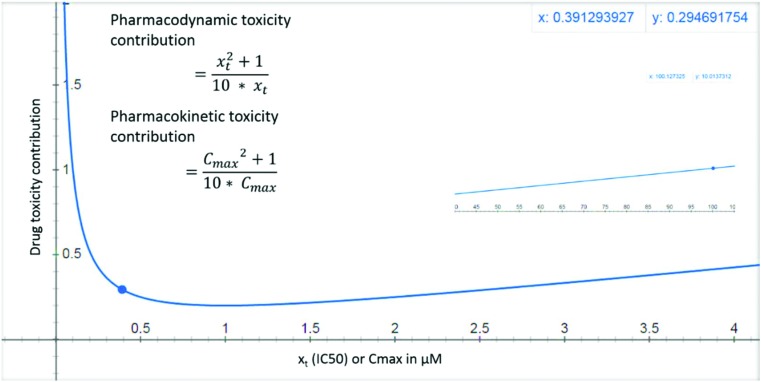

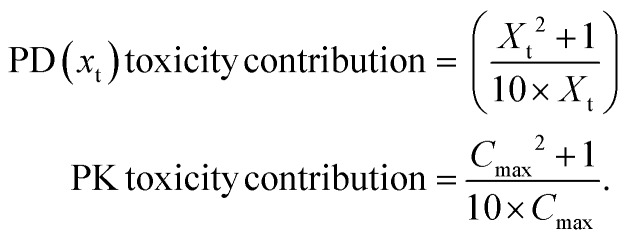

Maximizing LE may increase the drug-likeness, reduces dose and Cmax required for efficacy.18 Compounds with high affinity (IC50 < 0.01 μM) are less likely to cause off target toxicities. But they have the potential to cause on target toxicity e.g. bupivacaine19 or toxicity due to activation/inhibition of related targets.1 Such toxicities are hereby referred to as pharmacodynamic (PD) toxicity. Highly potent drugs (e.g. opioids) may cause PD toxicity when administered either alone or in combination with other drugs. This PD toxicity may precipitate due to small changes in the ADME of the highly potent drug induced by factors like the fluctuating patient's physiological parameters or due to the influence of co-administered drugs. For such drugs low doses are usually prescribed, but this doesn't eliminate toxicity risks. For some other highly potent drugs, large doses are required (mostly due to poor bioavailability e.g. bosentan), further increasing the PD toxicity risk due to ADME changes. Compounds with low affinity for the primary target generally require the administration of larger doses, achieve high Cmax, and have higher risk for off target activation and PD toxicity and are generally eliminated early in the drug discovery process. Thus compounds with IC50 > 10 or <0.01 μM at target are not drug-like. Therefore, PD on target (xt) toxicity contribution is modelled as a biphasic function of IC50 (Fig. 1 and eqn (1)). For molecules with very high binding affinity the toxicity potential is modelled as 1/(10 × xt), while for molecules with low binding affinity the toxicity potential is modelled as xt/10. The combined term (xt./10 + 1/10xt) then models the toxicity potential for both high and low affinity molecules.

Fig. 1. PD and PK toxicity of drug-like molecules is shown as a function of in vitro on target IC50 (xt) or Cmax (in vivo or extrapolated from in vitro permeability and metabolism assays) respectively. The inset shows that for a drug with an IC50 or Cmax value of 100 μM, the toxicity reaches a value of 10 units.

3.2. Pharmacokinetic (PK) toxicity and maximum plasma concentration (Cmax)

DRUGeff proposed earlier accounts for ADME, but ignores target potency.20 Drug Efficiency Index (DEI), proposed later, doesn't include PK and off target toxicity contributions.21 The lack of an upper bound on the unbound concentration (Cfree) for efficacy seems erroneous. When Cfree is comparable to dose (mg kg–1), exposure to the target organ may reach high levels, causing target over-activation, and PD toxicity. As toxicity correlates with Cmax, using steady state concentrations or Vd may not capture such toxicities. Utilizing the time to Cmax or AUC for toxicity prediction is complicated by factors like significant differences in frequency, duration of sampling/treatment, and ethical constraints in allowing drug concentrations to reach subtherapeutic levels, among others. Thus to keep the model simple Cmax was preferred.

In developing the DTI concept the relationship of free Cmax and toxicity is assumed to be similar to IC50 and toxicity (eqn (1), and Fig. 1). Cmax toxicity contribution is referred to here as “PK toxicity”. Drugs with Cmax < 0.01 μM required for efficacy are more likely to cause PK toxicity due to small variations in ADME e.g. bosentan.22 The toxicity potential for such compounds is modelled as 1/(10 × Cmax). Compounds with Cmax > 10 μM, required either for efficacy (due to high IC50, Vd or protein binding, or low clearance), may cause off target activation and PK toxicity and are modelled as Cmax./10. Thus, toxicity risk increases with very high or low IC50 and Cmax for drugs. Eqn (1) models the PD (on target) and PK toxicity contributions assuming that on target IC50 (xt) and Cmax between 0.01 and 10 μM represent safe drugs.

Pharmacodynamic PD (xt, on-target) and pharmacokinetic (PK) contributions to toxicity:

|

1 |

3.3. Pharmacodynamic (PD) toxicity and off target potency

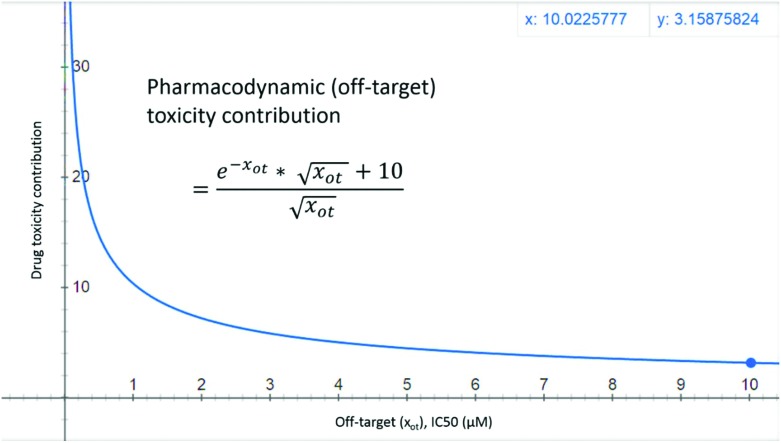

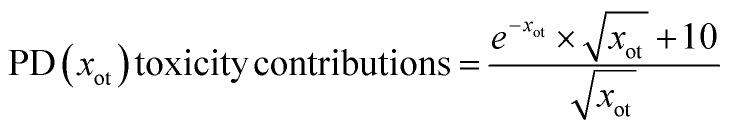

Compounds with high binding affinity at off targets (IC50 < 10 μM) are likely to have PD (off target) toxicity,1,7,20 while drugs with off target IC50 > 10 μM are usually considered further in the drug discovery process. One can model this fact using a negative exponential function, but a purely negative exponential function would always give a PD off target contribution of less than one (e–x < 1, for positive x and >1 for negative x values). Thus to keep the off target contributions aligned with the on target contributions an inverse square-root function 10/x0.5 was added. This gives the off target PD toxicity contribution of [(e–xot × (xot)0.5 + 10)/(xot)0.5] where xot is the off target IC50 (eqn (2)). Fig. 2 shows the PD (off target) toxicity contribution as a function of off target IC50. For a candidate with off target IC50 = 1, 10 and 100 μM, the off target PD contributions are 10.37, 3.16, and ∼1 respectively. Although negative exponential functions are commonly used in modeling PKPD properties (e.g. plasma concentrations, see chapter 2 in ref. 2), inverse square-root functions have been applied rarely. Inverse square-root relationships have been found useful in other fields like permeability (see the section on passive diffusion in chapter 5 of ref. 2), overall connectivity (Randić's inverse-square-root function),23 and radiotherapy.24 This paper represents the first ever application of an inverse square-root relationship to toxicity prediction.

Fig. 2. PD toxicity of drug-like molecules is shown as a function of in vitro off-target IC50 (xot) values. For a compound with an off-target IC50 value of 1 μM, the toxicity contribution has a value of 10.37.

Pharmacodynamic PD (xot, off-target) contributions to toxicity: An off target IC50 of 10 μM gives a PD toxicity contribution of 3.16.

|

2 |

3.4. Physicochemical contribution to toxicity and log D

A small increase in log D value causes significantly larger amounts of the drug to easily cross membranes, and accumulate in the liver, brain, and adipose tissues. Thus lipophilic compounds generally have off target activity, extensive metabolism, and hepatotoxicity, and are linked with adverse outcomes.9 A Clog P cut-off of 3 was found useful in categorizing drugs as toxic or non-toxic.25 But a mathematical formulation of the general relationship between these parameters and toxicity has not been proposed.

Log D is the ratio of the amount of drug present in the polar (water/cytoplasm) to that in the non-polar (octanol/cell membrane) compartments at physiological pH 7.4.26 Higher values for this ratio mean that a larger fraction of the drug would get absorbed, transported and/or metabolized. Because toxicity in most cases is likely to be related to this fraction of the drug entering into different organs, it is reasonable to expect that toxicity would correlate better with this fraction (rather than its logarithm). To recalculate this fraction of drug while keeping the physicochemical toxicity contribution aligned with PD contributions, the exponential of Log D was chosen (Fig. 3 and eqn (3)). Considering the RO3,11 and RO510 concepts, this contribution was corrected with a Log D × e term such that a molecule with Log D = 3, 5 get values close to 10 and 100 respectively. This gives eqn (3) for estimating physicochemical (Log D) toxicity contributions. Polar drugs (PSA > 75 Å2) inhibit anionic transporter systems with frequencies slightly higher than non-polar compounds (Fig. 3 of ref. 27) and may have similar toxicity potential. This highlights the need for the right balance between polar and non-polar characteristics. Log D contributions to DTI model this aspect as moderately higher contributions for polar compounds (3.09, 8.20, and 13.59 for –1, –3 and –5 Log D values respectively). To keep the model simple and aligned with PD contributions, additional overfitting and antilog functions (e.g. 10x–10 × x) with complex behavior (negative contributions between x = 0.1371 and 1.) were avoided.

Physicochemical (log D, pH = 7.4) contribution to toxicity:

|

3 |

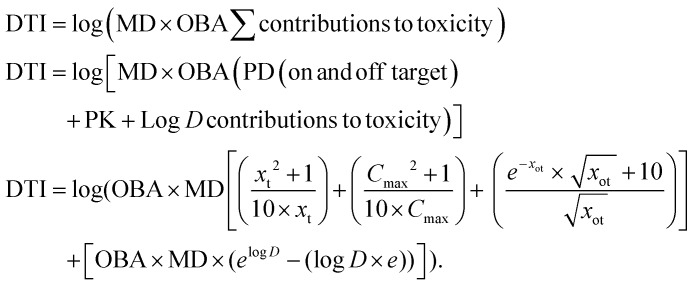

3.5. Drug toxicity index (DTI)

Although correlations between toxicity and physicochemical, PK and PD parameters are known, none of the toxicity prediction methods combines them into a single parameter. Thus a method using physicochemical, PD and PK data to estimate toxicity contributions for oral drugs was developed and tested. The individual PD, PK and physicochemical toxicity contributions discussed above estimate the intrinsic toxicity potentials of the drug/xenobiotics. Additionally, these intrinsic toxicity potentials are modulated by the exposure to the candidate toxicant, which in turn is determined by the dose and bioavailability28 (; https://toxtutor.nlm.nih.gov/03-002.html). For instance, very high or very low potency or Cmax values need not necessarily translate into high PD or PK toxicities respectively. These should rather be considered as one of the risk factors for toxicity and a realistic estimation of toxicity contributions requires scaling by oral bioavailability and molar dose. For example, Calcitriol has the lowest Cmax value (0.22 nM) in the dataset considered here and thus has the largest PK toxicity contribution (462 963). Scaling with molar dose (0.0000024 mmol) and oral bioavailability (0.61) gives a realistic PK toxicity contribution of 0.68 (and DTI = –0.17), which is in agreement with the generally safe clinical profile for this drug at recommended doses. Phentolamine with a high Cmax (45.8 μM) gives an unscaled PK toxicity contribution of 4.5, suggesting moderate potential for toxicity. Scaling with molar dose and bioavailability reduces this PK toxicity contribution to 0.17, in agreement with the well-known clinically safe profile of this drug.29

Although it is customary to avoid candidates with high off target affinity in drug discovery projects, a low IC50 value at the off target alone need not necessarily translate into a clinically relevant drug interaction and toxicity.30 For example, Pergolide Mesylate is a potent CYP2D6 inhibitor and has an unscaled PD (off target) toxicity contribution of 163 but has been found safe in patients with comorbidities (Parkinson's and heart diseases), and co-administered drugs (causes only mild liver enzyme elevations).30,31 Scaling with molar dose and oral bioavailability reduces the PD (off target) toxicity contribution to 0.31 (DTI to –0.20), thus correctly predicting a save clinical profile.

Categorizing drugs based on simple log P/D cut-off values is an oversimplification of the drug toxicity and lipophilicity relationship. For example, Cefdinir has the lowest log D value (–5.48) in this dataset and thus should be safe according to simplified rules and cut-off criteria. But Cefdinir has been reported to cause liver toxicity.32 Unscaled log D toxicity contribution (14.9) predicts high potential for toxicity, whereas scaled contribution reduces to 3.4 (DTI = 0.63), suggesting a moderate toxicity potential in agreement with rare literature reports on hepatotoxicity. Similarly, Nabilone is very lipophilic (log D = 7.25) and, according to RO3, is expected to have high potential for hepatotoxicity. The physicochemical log D toxicity contribution for this drugs is 1388. But scaling with molar dose and oral bioavailability significantly reduces the toxicity contribution to 0.75 (DTI = –0.06). This is in agreement with the absence of liver injury and safe clinical profile of this drug.31,32

The individual PD, PK and physicochemical (log D) contributions are thus scaled by molar dose and oral bioavailability, summed and the logarithmic sum is defined as the Drug Toxicity Index (DTI, eqn (4)). In contrast to classical TI, DTI does not consider drug toxicity to simply decrease (or increase) with a decrease (or increase) in on target IC50, plasma free Cmax, or log D. The proposal of higher response (toxicity) at very low or high doses has been tested, and debated under the Hormetic model of dose–response curves.33 The DTI concept is different and novel as it expresses the toxicity as a function of different physicochemical, PD and PK parameters of a molecule instead of just dose.

The utility of the DTI concept and values for understanding (i) differences in WHO ATC drug classes, (ii) classification of drugs for drug-induced liver injury (DILI) concern, (iii) relative toxicity potential within a therapeutic area, (iv) physicochemical, PK and PD toxicity contributions, (v) identifying potentially toxic drugs, and (vi) recently approved drugs is discussed below. A decision tree approach is presented describing the potential use of the DTI concept in a typical drug discovery project followed by limitations and scope for improvements.

The Drug Toxicity Index (DTI) is defined as the logarithmic sum of physicochemical (Log D), pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) contributions to toxicity scaled by absolute oral bioavailability (OBA), and molar dose (MD). Here, Xt is potency (IC50 or MIC) at the target protein, Cmax is the maximum unbound plasma drug concentration, Xot is the binding affinity at the off-target (CYP450 isoforms, hERG channel and BSEP transporter), and log D is the ACD log D at pH = 7.4. PD and PK contributions to DTI are defined only when Xt, Cmax and Xot are greater than zero.

|

4 |

3.6. DTI and WHO ATC drug classes

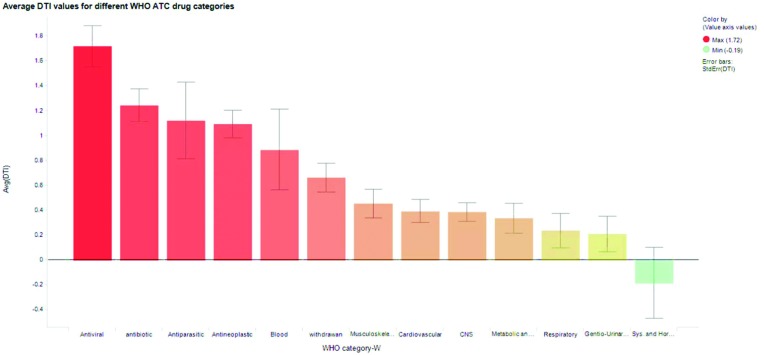

The DTI for WHO ATC drug classes (711 drugs) was analyzed. DTI values (for full data see Excel files in the ESI†) for antiviral, antibiotic, antineoplastic (anticancer), and withdrawn drugs are higher than those for other drug classes (Fig. 4). As small datasets are used, the average DTI for antiparasitic, systemic and hormonal, and blood categories should be interpreted cautiously.

Fig. 4. Average DTI values for different WHO ATC classes of drugs and withdrawn drugs considered in this work. Error bars represent standard errors.

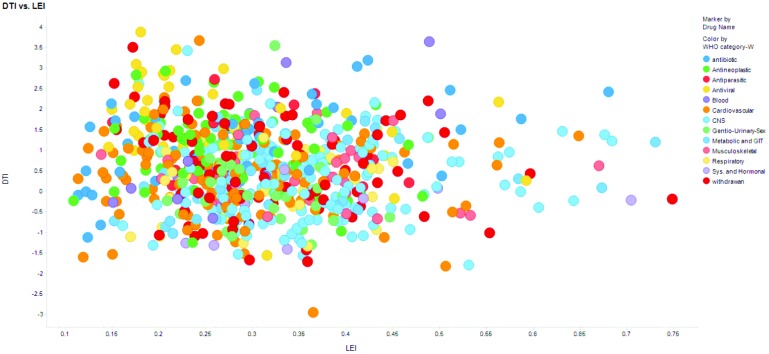

Fig. 5 shows scatter plot for DTI and LEI. Molecules with LEI > 0.3 and LLE > 5 are generally considered good candidates for drug development.18 Withdrawn drugs are expected to have LEI < 0.3, LLE < 5. Of 88 withdrawn drugs, 53% (Table 1) satisfy LEI criteria.18 DTI performs similarly (50%, at 0.67 cut-off). Only 43, 24 and 43% withdrawn drugs have dose >100 mg and log D > 3. On average 36 and 27% approved drugs satisfy RO2 criteria (73% for systemic and hormonal drugs) and 13 and 20% satisfy log D criteria (see Table S11†). Although DTI and LEI (LLE, 67%) have similar performances for withdrawn drugs, DTI offers scope for interpreting toxicity contributions.

Fig. 5. Scatter plots of LEI and DTI values for different WHO ATC drug classes show that LEI and DTI values have no correlation.

Table 1. Percentage of drugs satisfying the different efficiency (LEI, LLE), dose and physicochemical parameter criteria recently recommended. Comparison of average DTI values against these widely used parameters for lead optimization suggests that a DTI criterion of <1 is better in many cases and equal in others (except for antineoplastic and antiviral drugs). For PD on target/off target, PK and physicochemical contributions to DTI, the respective average values have been used as cut-off criteria (see ESI).

| WHO ATC drug category | LEI > 0.3 | LLE > 5 | PD on target | PK | Physicochemical Log D | PD off target |

DTI < 1 | Exposure based TI, % of IC50/Cmax values between 0.5–2 | Dose < 100 mg | ACD log D < 3 | log P < 3 | ||

| CYP450 | hERG | BSEP | |||||||||||

| Musculoskeletal | 58 | 24 | 71 | 89 | 84 | 84 | 95 | 89 | 84 | 13 | 34 | 97 | 55 |

| Antiparasitic | 45 | 18 | 73 | 82 | 91 | 100 | 91 | 82 | a 55 | 0 | 27 | 82 | 73 |

| Antibiotic | 36 | 54 | 94 | 86 | 80 | 84 | 86 | 76 | b 54 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 80 |

| Metabolic and GIT | 46 | 63 | 83 | 96 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 90 | 77 | 17 | 69 | 90 | 79 |

| CNS | 69 | 44 | 94 | 86 | 84 | 90 | 85 | 90 | 73 | 21 | 68 | 84 | 62 |

| Systemic and hormonal | 45 | 55 | 82 | 91 | 91 | 82 | 100 | 82 | 91 | 9 | 82 | 82 | 64 |

| Withdrawn | 53 | 67 | 18 | 14 | 01 | 11 | 18 | 9 | c 50 | 0 | 43 | 24 | 43 |

| Gentio-Urinary and Sex | 40 | 38 | 98 | 98 | 90 | 90 | 88 | 90 | 85 | 20 | 80 | 48 | 38 |

| Antiviral | 24 | 61 | 80 | 73 | 93 | 76 | 85 | 76 | d 51 | 7 | 17 | 56 | 39 |

| Respiratory | 61 | 31 | 89 | 78 | 83 | 89 | 83 | 92 | 83 | 17 | 75 | 75 | 47 |

| Blood | 33 | 27 | 93 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 80 | 87 | 73 | 13 | 53 | 73 | 40 |

| Cardiovascular | 37 | 31 | 86 | 98 | 89 | 86 | 89 | 88 | 74 | 11 | 63 | 70 | 48 |

| Antineoplastic | 35 | 56 | 82 | 85 | 90 | 85 | 81 | 87 | 43 | 10 | 35 | 62 | 50 |

| Average across therapeutic area | 45 | 44 | 80 | 82 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 80 | 69 | 11 | 50 | 72 | 55 |

DTI performs better than LEI, LLE, and the doses for Musculoskeletal, Antiparasitic, Metabolic and GIT, CNS, Systemic and Hormonal, Gentio-Urinary and Sex, Respiratory, Blood, and Cardiovascular categories (Table 1). DTI one cut-off performs better than other parameters for Cardiovascular, Respiratory, Blood, Gentio-Urinary and Sex, Systemic and Hormonal categories. For Antiparasitic, Antibiotic, Antiviral, and withdrawn drug categories the average DTI cut-off value performs better than other parameters. The use of the average cut-off value is justified considering the known higher toxicity for these drug classes. Across all categories the average percentage of drugs satisfying parameter cut-off values shows that DTI is the best parameter (69%) considering its interpretability. Log D gives minor improvement but has limited scope for understanding toxicity contributions. PK, physicochemical, PD on and off target, contributions to DTI also show excellent performance at identifying safe drugs (see ESI Tables S12 and S13† for the averages). Contributions to DTI have moderate performance for withdrawn drugs but DTI itself performs better. DTI is better than exposure based TI at estimating safety. Only 26, 20 and 23% drugs across different WHO ATC drug categories satisfied exposure based TI of ≥30 for CYP450, hERG and BSEP inhibition (Table S11†). At efficacious doses the free Cmax is generally within 0.5–2 times that of IC50.34 Against this criterion DTI is 6.6 times better at estimating drug safety. Within the dataset considered here, ∼27% of drugs have negative DTI values (see Table S12†). These should not be interpreted as having zero or no potential for toxicity. Rather negative DTI values indicate a total contribution to the toxicity of less than 1 (eqn (4), DTI = log(MD × OBA∑toxicity contributions)). These can be interpreted (cautiously) as having lower toxicity potential (see sections 3.8.1 and 3.13), arising from different physicochemical (Log D), PD (on and off target) and PK toxicity contributions (discussed in sections 3.1–3.4) considered for calculating the DTI. It is worth noting that, although DTI values can be negative, the individual and total toxicity contributions (as defined in eqn (1)–(3)) can be either positive or zero, but not negative.

DTI differentiates WHO ATC drug categories (ANOVA, Table S1†). Antibiotic and antiparasitic drugs are similar in their toxicity potential (similar DTI values avg; 1.12, 1.24, max; 3.2, 2.74, min; –1.12, –0.08 respectively, Fig. 4). The withdrawn drugs (avg; 0.67) are differentiated from nine drug classes (antibiotic, metabolic and GIT, nervous system (CNS), systemic and hormonal, gentio-urinary and sex, antiviral, respiratory, cardiovascular and antineoplastic). LEI, molar dose, dose, OBA, IC50, free Cmax, PPB, ACD log D, and log P differentiate only 4, 6, 6, 4, 5, 6, 4, 5 and 3 drug category pairs respectively (Tables S11–28†). Antiviral drugs have the highest average DTI, suggesting high toxicity. Although ∼64% correct differentiation among WHO ATC drugs may sound ordinary, it is better than random prediction and has been attempted for the first time. Thus differentiating the toxicity potential between the different WHO ATC drug classes is not possible with simple PD, PK and physicochemical parameters. This is possible with the DTI concept as it is able to differentiate withdrawn drugs from 9 (out of 12; 75%) other approved drug classes.

3.7. US-FDA's liver toxicity knowledge base (LTKB) and DTI

The utility of DTI to correctly classify drugs with drug induced liver injury (DILI) concern was tested with the US-FDA's LTKB containing 1039 drugs.13 DTI could be calculated for 392 drugs. Eighty-five, 233 and 74 had most-DILI-concern, less-DILI-concern and no-DILI-concern. This proportion of drugs with different types of concern annotations is similar to that present in the larger database with 1039 drugs. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC, Table 2) was generated by considering different DTI cut-off values. The AUC was calculated using two types of categorization (see Table 2 and ESI Excel file†).

Table 2. AUC values for the ROC curves calculated using different DTI cut-off values for the classification of toxic and safe drugs reported in the US-FDA LTKB database.

| WHO ATC drug category | Number of drugs | AUC value for ROC curve |

|

| (A) Toxic = Most-DILI concern safe = No-DILI + Less-DILI concern | (B) Toxic = Most-DILI + Less-DILI concern safe = No-DILI concern | ||

| Drugs used from LTKB | 392 | 0.72 | 0.62 |

| Gentio-urinary & sex | 20 | 0.61 | 0.64 |

| Antiviral | 19 | 0.53 | 0.89 |

| Respiratory | 16 | 0.73 | 0.46 |

| Metabolic and GIT | 26 | 0.52 | 0.39 |

| Musculoskeletal | 24 | 0.48 | 0.91 |

| CNS | 100 | 0.84 | 0.64 |

| Cardiovascular | 76 | 0.84 | 0.58 |

| Antibiotics | 34 | 0.69 | NA a |

aNone of the drugs in the antibiotics class for which DTI could be calculated had a No-DILI-concern annotation. For other drug categories, the no. of drugs with LTKB annotations and DTI values was below 10 and thus these were not analysed.

DTI gave a good AUC of 0.72 for all 392 drugs (categorization A), while for CNS and cardiovascular drugs excellent classification was achieved (AUC, 0.84). Respiratory and antibiotic drugs were classified with good AUC, 0.72 and 0.69. Categorization B gave an excellent AUC of 0.89 and 0.91 for antiviral and musculoskeletal drugs respectively. These drug categories are more likely to cause liver injury and even a low hepatotoxicity risk should be considered seriously. These results agree with the toxicity trends found earlier.13

The AUC for the ROC curves estimated with categorization A correlates well (r = 0.77) with the number of drugs within each therapeutic area. This suggests that predictions can be improved with the inclusion of additional drugs within each therapeutic area if the missing data (in vitro/in vivo) become available. Lack of correlation for categorization B (r = –0.09) suggests that this calcification is specific to antiviral and musculoskeletal drugs. But due to a small number of drugs considered here, data for additional drugs would be required to confirm this suggestion. DTI's ability to predict the potential for hepatotoxicity and other forms of toxicity is discussed in the following sections.

3.8. Relative toxicity potential within a therapeutic area

Assessing the relative drug efficacy and toxicity is important for medicinal chemists, pharmacologists, pharmacists, physicians, and regulators.35 As multiple treatment options are available for many diseases, relative toxicity assessment is necessary. Difficulty in direct clinical trial comparisons forces network meta-analyses for estimating the relative toxicity.36 The application of DTI for estimating network meta-analysis outcomes is discussed (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of the correlations of DTI values with clinical outcome measures reported in various network meta-analyses of clinical trials performed to analyse the relative safety and efficacy of different treatment options in following therapeutic areas.

| Therapeutic area | Number of drugs | Clinical toxicity/efficacy outcome (odds ratio) | Correlation of DTI values with clinical toxicity/efficacy outcomes |

| Musculo-skeletal (NSAIDs) | 9 | GIT side effects | 0.85 |

| Antibiotics | 5 | Overall adverse effects | 0.64 |

| CNS-antipsychotics | 13 | All cause discontinuation | 0.75 |

| CNS-antidepressants | 9 | Response rate odds ratio | –0.72 |

| Metabolic and GIT-antidiabetics | 15 | Hypoglycemia | –0.68 |

| Gentio-urinary and sex | 5 | Frequency of adverse effects | 0.84 |

| Antiviral | 10 | Discontinuation due to AE | 0.63 |

| Viral suppression | –0.86 | ||

| Blood and blood forming agents | 5 | All types of strokes | 0.69 |

| Myocardial infraction | 0.86 |

3.8.1. NSAIDs and DTI

DTI for a set of NSAIDs were compared with the clinical risk of gastrointestinal complications and gave a good correlation.37 Table S2† shows that the relative risk of gastrointestinal toxicity correlates well with DTI (r; 0.85, Diclofenac and Piroxicam excluded). The Diclofenac DTI is negative because all off-target effects are not considered. Addition of COX-1 IC50 (0.003 μM) and PD toxicity contribution (5.06) makes DTI 0.84, explaining Diclofenac's toxicity. Piroxicam's toxicity has been linked to reactive metabolite formation (see “section 3.13 Limitations of the current DTI methodology”). Thus, DTI gives reliable estimates of relative NSAID toxicity.

3.8.2. Antibiotics and DTI

The relative efficacy and adverse effects of 5 antibiotics (Ciprofloxacin, Norfloxacin, Amoxicillin-Clavulanate, Gatifloxacin, and Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole) give a moderate correlation of 0.64 with DTI (Table S3†).38 DTI correlates with the relative adverse effects (except for Gatifloxacin). For the trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole combination, a modification of the Hill function to predict the response to the combination has been used.39 A larger clinical dataset may confirm this utility of DTI.

3.8.3. CNS drugs and DTI

Leucht et al. performed a network meta-analysis to estimate the odds ratio (OR) for all-cause discontinuation, sedation, weight gain, QTc prolongation and extrapyramidal effects for fifteen antipsychotics.40 DTI correlates well with all-cause discontinuation OR (13 drugs, r; 0.75, Table S4†). Clozapine has been associated with many liver injuries. Clozapine's DTI captures liver toxicity via the contribution of log D, 22.5. A re-evaluation of Clozapine cardiotoxicity has been suggested (scaled hERG DTI contribution, 21.8).41

Relative tolerability was reported for ten antidepressants using OR for the response, remission rates, and withdrawal rates due to adverse effects.42 The OR for response rates correlated well (negatively, r; –0.72) with DTI (Table S5†). Agomelatine showed the highest OR for the response rate (low DTI). Thus DTI can predict the relative safety of CNS drugs.

3.8.4. Antidiabetic drugs and DTI

The relative hypoglycemia risk and body weight change estimated for 15 antidiabetic drugs correlated (negatively, r; –0.68, –0.60, Table S6†) with DTI.43 Relative risk for UTI and genital tract infections showed weak and decent correlations respectively with DTI. The significance of the negative correlations with adverse effects requires further investigation.

3.8.5. Gentio-urinary and sex drugs and DTI

The relative efficacy and adverse event frequencies reported for seven PDE5 inhibitors show good correlation (r; 0.84, Table S7†) with DTI.44 An earlier study comparing Tadalafil, Vardenafil, and Avanafil did not find a significant difference in their safety profiles45 and thus these results should be interpreted cautiously.

3.8.6. Antiviral drugs and DTI

Patel et al. estimated OR and percentage values for the efficacy, safety and discontinuation due to adverse effects (Table S8†) for Dolutegravir and seven other drugs.46 OR for efficacy parameters and triglyceride levels have good correlation with DTI. The correlation of OR for discontinuation due to AE with DTI is 0.63. Poor correlations for combined-DTI values can be due to different and undisclosed doses used in different combinations. This can significantly alter the individual (PD, physicochemical and PK) contributions and the DTI.

3.8.7. Blood and blood forming (anticoagulant) drugs and DTI

OR for myocardial infraction and all-cause-strokes for acetylsalicyclic acid plus Clopidogrel (ASA + C), Apixaban, Rivaroxaban, Dabigatran, and Edoxaban against Warfarin as a reference have excellent correlations with DTI (Table S10†).47 These suggest that DTI might be useful in estimating the relative toxicity of antithrombotics.

Although the relative toxicity/efficacy for cardiovascular,48 antiemetic,49 and antiulcer drugs is available, such studies often compare drug sub-classes (e.g. beta-blocker, ACE, proton-pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists, and 5HT-agonits). Molecule specific clinical risks associated with these and antiparasitic drugs were not found in the literature. Thus the use of the DTI concept in estimating relative drug safety/efficacy for these categories remains to be tested.

3.9. Physicochemical, PK and PD toxicity contributions

Efficacy (52%) and safety (24%) are top reasons for Phase II drug discovery failures.50 Thus estimating toxicity potential in Phase I studies is a high priority. The following examples demonstrate the utility of DTI in estimating toxicity potential from Phase I PK, PD, and physicochemical data.

Reactive metabolite formation has been proposed for Troglitazone toxicity.51 DTI estimates a PD on target contribution of 0.08 (IC50 at PPARγ, 0.98 μM), and PD (off target) contributions of 2.36, 0, and 2.51 (CYP450, hERG, BSEP, see Table 4). For a dose of 400 mg (MD, 0.91) and an oral bioavailability of 45%, the free Cmax value is 0.036 μM (PPB, 99%) and the PK toxicity contribution is 1.12.52 The largest contribution is from the physicochemical parameter (log D, 3.65) of 11.64, making DTI 1.25. Calculations for Pioglitazone (non-hepatotoxic) give DTI 0.45 (Table 4). Reducing the Troglitazone dose to 200 mg decreases these contributions to 0.04, 1.18, 0.0, 1.25, 1.00 and 5.82, marginally decreasing DTI (0.97) and suggesting a similar toxicity risk. Thus reducing the dose doesn't reduce the toxicity potential proportionally. Rosiglitazone cardiotoxicity is most likely the result of KATP or kinase inhibition.53 Thus, Rosiglitazone toxicity cannot be predicted using the current DTI formulation (–0.17), as it excludes other off target effects.

Table 4. Individual toxicity contributions and DTI for drugs discussed in the main text.

| Drug | Toxicity contributions |

DTI | |||||

| PD on target | PD off target |

PK | Log D (physicochemical) | ||||

| CYP450 | hERG | BSEP | |||||

| Troglitazone (400 mg) | 0.08 | 2.36 | 0.00 | 2.51 | 1.12 | 11.64 | 1.25 |

| Troglitazone (200 mg) | 0.04 | 0.00 | 1.25 | 1.00 | 1.18 | 5.82 | 0.97 |

| Pioglitazone | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 1.99 | 0.28 | 0.14 | 0.45 |

| Terfenadine | 4.24 | 4.05 | 1.49 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 6.91 | 1.22 |

| Fexofenadine | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 | –0.15 |

| Telotristat ethyl | 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 28.99 | 3.54 | 1.54 |

| Enasidenib | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 2.84 | 0.52 |

| Brivaracetam | 7.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 12.79 | 0.50 | 1.32 |

| Cariprazine | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 15.24 | 0.74 | 1.24 |

Terfenadine has PD on target (4.24), off target (1.49, hERG; 4.05, CYP450; 0.0, BSEP), PK (0.08) and physicochemical (6.91) toxicity contributions giving DTI 1.22 (Table 4). The physicochemical contribution is the largest; hERG and CYP450 inhibition contributes significantly to correct toxicity prediction. Fexofenadine (non-toxic)54 has PD on target (0.56), PD off target (0.10, 0.0, 0.0), PK (0.05) and physicochemical (0.01) toxicity contributions with DTI –0.15 (Table 4).

3.10. Identifying potentially toxic and relatively safe drugs

The LiverTox website categorizes drugs based on reports of clinically apparent liver injuries.31 This categorization along with the literature reports was used to assess predictions made with DTI. Since the categorizations in LiverTox are still in active development and all drugs do not have a likelihood score assignment or equal experience in the clinic, the assessment of toxicity potentials presented here is of qualitative and suggestive nature and is meant for retrospective analysis (; https://livertox.nih.gov/DrugCategory.html accessed on 11/11/2018). DTI values and different PD, PK and Log D contributions are with liver and other forms of toxicities. Representative examples with high, low and average DTI values are discussed below for musculoskeletal drugs.

Musculoskeletal category (DTI max, 1.85; min, –0.66; avg, 0.41), niflumic acid has the highest DTI value, but toxicity information is limited. Mesalazine (DTI, 1.73) has been associated with many cases of hepatotoxicity and has a likelihood score of C. Probenecid and Eperisone (DTI, 1.62) have been associated with hypersensitivity reactions and Eperisone's safety is questionable.55 Indomethacin (DTI, 0.46) has been associated with rare idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity and has a likelihood score of C. Meloxicam (DTI, –0.32) is generally found to be non-hepatotoxic and shows only rare serum enzyme elevations. Teriflunomide has a low DTI (–0.61), does not show liver injuries and show only mild serum enzyme elevations. With a likelihood score of D, it nevertheless has a black-boxed warning due to less clinical experience. Addition of off target (COX-1, IC50, 140 μM)1 PD contribution for Valdecoxib increases the DTI value to 0.53. With a toxicity cut-off >1, the musculoskeletal drugs were predicted with high accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity (0.84). A comparison with withdrawn drugs (DTI avg, 0.68, n = 9) shows that approved drugs tend to have lower DTI. A similar discussion on other drug categories is given in the ESI PDF file.†

3.11. Recently approved drugs

Telotristat ethyl has PD (on and off target) and physicochemical contributions to toxicity of 0.01, 0.96 (CYP450), 0.99 (hERG), 0.0 (BSEP) and 3.54 (log D), a PK contribution of 28.99, and DTI 1.54 (Table 4). This agrees with the safety data (US-FDA approval package) where 8.4% of the patients experience serum enzyme elevations, and 66.9% showed GIT side effects. Enasidenib, approved August 2017, has PD (on and off target), PK and physicochemical toxicity contributions of 0.02, 0.0 (CYP450), 0.40 (hERG), 0.0 (BSEP), 0.03 and 2.84 respectively and DTI 0.52 (Table 4). The US-FDA label warns of differentiation syndrome and embryo-fetal toxicity. Off target inhibition (UGT1A1, not considered here) has been suspected for this toxicity.56

Brivaracetam, approved February 2018, has PD (on and off target), PK and physicochemical toxicity contributions of 7.56, 0.0 (CYP450, hERG, BSEP), 12.79 and 0.50 respectively and DTI 1.32 (Table 4). The US-FDA label mentions hypersensitivity, hepatic injury and adverse neurological effects, but the mechanisms are unclear. PD (off target) and physicochemical contributions to DTI correctly predict a lack of hepatotoxicity. Cariprazine, approved September 2015, has PD (on and off target), PK and physicochemical toxicity contributions 1.25, 0.0 (CYP450, hERG, BSEP), 15.23 and 0.74 respectively and DTI 1.24 (Table 4). Increased death risk, weight gain, orthostatic hypotension, hypersensitivity, cerebrovascular, tardive dyskinesia, and bipolar mania were observed during clinical trials (US-FDA approval package). Thus the toxicity of Cariprazine is mostly related to complex pharmacological interactions; CNS disorder management and DTI capture these toxicities.

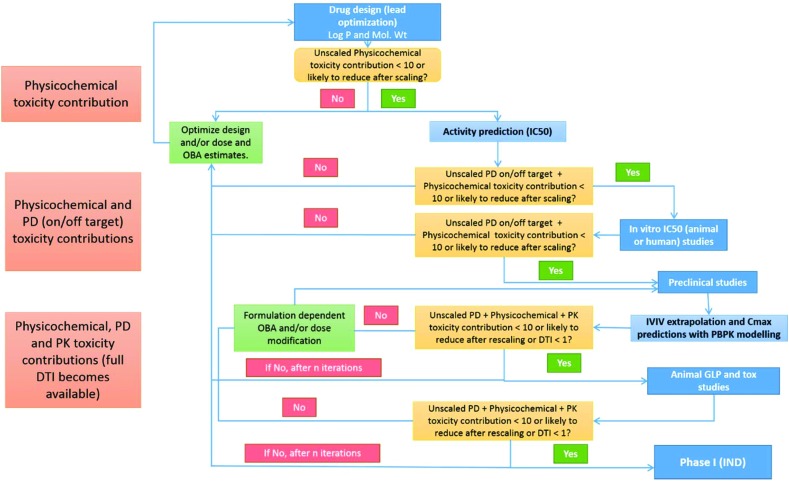

3.12. Decision trees for using DTI in a typical drug discovery project

Since the drug discovery usually starts with a large number of potential candidates it is important throughout this process to filter less efficacious or toxic candidates using a set of well understood rules or guidelines. At present none of the available rules or guidelines can be used from the start until the end i.e. each set of rules has its applicability domain within different drug discovery phases. For example, Lipinski's rule of five, ligand/structure based methods, and LEI are extensively used along with others in virtual screening and lead to optimization stages. But these have a limited role once a candidate enters preclinical or clinical stages where PK parameters and efficacy/toxicity endpoints are utilized for screening (on smaller sets). A comprehensive approach, like the DTI presented here, that allows a parameter's efficacy/toxicity prediction value to be used beyond the original application domain is likely to increase accuracy and offer scope for deeper insights as one moves ahead in drug discovery phases. A flowchart like decision tree summarizing the potential application of the DTI concept in a typical lead identification/optimization to Phase I drug discovery project is given in Fig. 6 and its caption.

Fig. 6. A decision tree proposed for potential application of Physicochemical, PD (on/off target) and PK toxicity contributions and the DTI concept in a typical small molecule drug discovery project. Ideally one would start with the structure and log D/P values for potential candidates obtained using different hit/lead identification procedures. Candidates with physicochemical toxicity contributions > 10 can be filtered out unless scaling with molar dose and/or oral bioavailability is likely to reduce them significantly. In silico prediction of selected compounds then gives an estimate of the PD (on/off target) toxicity contributions. Candidates with physicochemical + PD toxicity contributions > 10 can be filtered out unless scaling is likely to reduce them. Selected candidates can be tested in vitro and PD toxicity contributions re-estimated and candidates again filtered on the same criteria. In vitro–in vivo (IVIV) extrapolations for animal or human exposure of selected candidates using PBPK modelling will give estimates of Cmax (dose and oral bioavailability) and PK toxicity contributions. At this stage the first total DTI estimates will become available and candidates with DTI > 1 should be re-evaluated for progression to the next phase. Follow-up toxicity and efficacy studies may be useful based on a mechanistic understanding derived from toxicity contributions, and DTI. Preclinical studies performed on selected candidates will allow first experimental measurements of DTI in animals. Candidates with DTI < 0.5 can be considered for Phase I, while those with DTI ≥ 1 ± 0.5 should be carefully reassessed using general FDA guidelines, therapeutic area specific knowledge and risk/benefit ratio for patients. DTI and its physicochemical, PD and PK contributions are intended to complement existing state-of-the-art in drug discovery and any disagreement between DTI and other approaches should be assessed carefully considering the limitations of DTI (and other methods) before making a final decision. Blue filled boxes on the right indicate experimental studies. Light orange color filled boxes indicate decision points based on toxicity contributions (<10) or DTI values (<1). Light green filled boxes on the left indicate the requirement of additional cycle(s) of design and optimizations. Light red boxes on the left indicate the type of data required and toxicity contributions that can be estimated at different time points within a drug discovery project.

For example, let us consider Troglitazone (discussed in section 3.9) as a potential candidate for development. One begins with an unscaled Log D (3.65) contribution to DTI, which is 28.55. Thus if a highly bioavailable formulation for Troglitazone (OBA ≈ 1) is targeted, an oral dose of <20 mg (0.05 mmol) would be required to keep Log D's contribution below 1.3. Higher doses e.g. 100 mg (0.23 mmol) lead to higher Log D contributions, effectively reducing the flexibility and tolerance available with other parameter ranges (since DTI should be <1). Then the IC50 (on target; 0.98 μM) gives an unscaled PD (on target) contribution of 0.2. Thus, as per the DTI concept, Troglitazone's moderate potency is not a problem in terms of its toxicity potential. But its unscaled PD off target contributions would add a total of 11.93. This also constrains the dose to <20 mg to keep DTI < 1. Thus the design question to move such a candidate into the next (preclinical) phase is: can we achieve good exposure (Cfree) with these doses and OBA constraints and maintain PK contribution to DTI below 10 and ideally DTI below average for the therapeutic area? For Troglitazone the answer is no because larger doses are required for good exposure and a therapeutic effect, thus increasing the molar dose and PD, PK and physicochemical contributions to DTI and toxicity potential. Thus, using the DTI concept, Troglitazone can be dropped from further development at different stages if other compounds (with a similar/lower molecular weight) have lower lipophilicity, similar on target potency, lower off target potencies (>10 μM), good (predicted) exposures coupled with lower estimates for the PD, PK contributions and DTI.

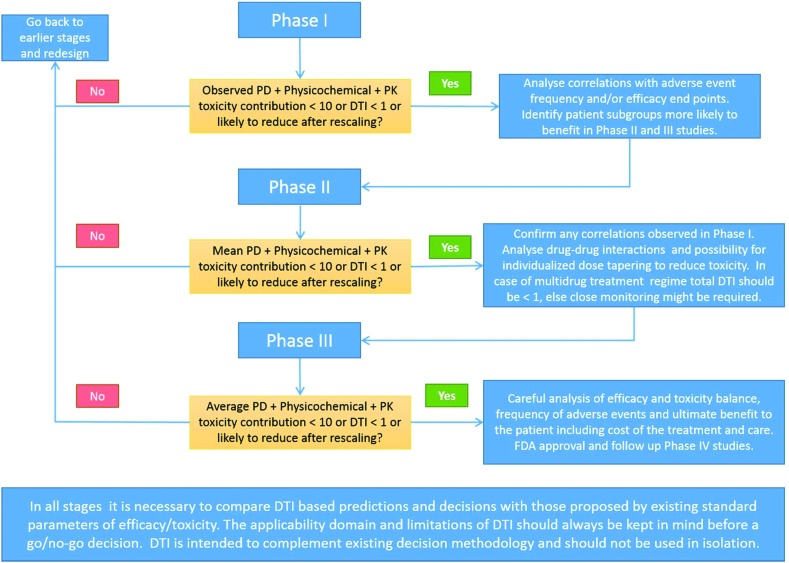

Based on the correlations discussed in “section 3.8 Relative toxicity potential within a therapeutic area”, applications of the DTI concept beyond Phase 1 are clear and a flowchart like decision tree is proposed in Fig. 7 and its caption.

Fig. 7. Physicochemical and PD toxicity contributions for candidates entering Phase I can be altered only by modification of dose and/or oral bioavailability. PK contributions can be estimated from the Phase I Cmax and estimates of oral bioavailability. DTI and different contributions can be interpreted with confidence in therapeutic areas with good correlation of efficacy/toxicity endpoints with DTI demonstrated in this study. Generally candidates with DTI < 0.5 can be considered for the next phase, while those with DTI ≥ 1 ± 0.5 should be reassessed carefully. Similar thinking can be applied during Phase II and Phase III to gain insights into the mechanisms of toxicity and propose measures to monitor and reduce them. Applications of DTI in combination therapies, personalized dosing/therapies and drug monitoring are principally possible but need to be established with a careful study design and data analysis. Blue filled boxes on the right indicate the data analysis required while moving to the next stage of clinical trials. Light orange color filled boxes indicate decision points based on toxicity contributions (<10) or DTI values (<1).

3.13. Limitations of the current DTI methodology

Current DTI formulation has some limitations which should be considered during interpretation. DTI considers hepatotoxicity arising only from lipophilicity, CYP450 and BSEP inhibition. Interaction with non-CYP450 metabolic enzymes might lead to drug–drug interactions and toxicity.57 Additional off target7 contributions may improve the predictive performance (as demonstrated for diclofenac, section 3.8.1), especially for drugs with negative DTI values. The PK contribution may indirectly compensate, but this needs to be tested. Cfree at the target has been suggested for in vivo efficacy but such information is not available for the majority of drugs.34 Oral bioavailability data for 59 (∼8%) compounds were not from human studies. This is unlikely to affect the major findings, but the prediction accuracy can improve with human data for these compounds.

Active and reactive metabolites play important roles in drug efficacy and toxicity. But accounting for this is non-trivial since information on the extent of metabolism, identity, and exposure to metabolites, and their on and off target effects is unknown. Currently, DTI doesn't include reactive metabolite contributions to toxicity.

The DTI concept was applied to orally administered drugs since Cmax and bioavailability of intravenously, arterially, intrathecally, and intracranially administered drugs may depend on the infusion rate and the site of administration. Topical, inhalational, rectal, vaginal, intramuscular, peritoneal, and other routes of administrations also present difficulty and thus were not considered. Since the PK and PD data for investigational compounds is generally not released before approval, the DTI concept could not be tested for them. Nevertheless, DTI and its PK, PD and physicochemical contributions are able to explain the observed clinical safety/toxicity profiles of recently approved drugs.

The DTI concept is not directly applicable to drugs with purely physical (e.g. sorbitol and deoxycholic acid), chemical (e.g. Clofazimine, Cyclophosphamide and Methoxsalen) or unknown mechanisms of action (e.g. Quinacrine, Omega-3 acid ethyl esters and Stiripentol). For these drugs biological targets are seldom well defined against which IC50 or Kd values can be evaluated. Estimation of off target PD, PK and physicochemical contributions might still prove useful for understanding toxicity profiles.

Since artificial intelligence (AI) or machine learning methods present unique difficulties (e.g. requirement of larger datasets, computational time, hardware, well-defined and consistent bioactivity end points) in the implementation and interpretation of complex drug discovery data, these methods were not applied in this study. Very few cases of AI based toxicity predictions, directly relevant here, exist.58 Nevertheless, the application of AI and deep learning may improve predictions; this will be taken up in our future attempts of toxicity studies.

4. Conclusions

The DTI, an improved mathematical model, has been presented to redefine drug toxicity as biphasic and exponential functions of typical PD, PK and physicochemical parameters. It has been found to perform better than some of the widely used ligand efficiency indices, drug-likeness rules, and exposure based TIs. DTI is useful in differentiating withdrawn drugs from nine other WHO ATC drug categories and correctly identifies higher toxicity potential for antiviral and antibiotic drugs. DTI correctly identifies the DILI concern with excellent–good accuracy for different WHO ATC drug categories. It does particularly well for CNS, Cardiovascular, Musculoskeletal and Antiviral categories. DTI was also found to be useful in estimating relative drug efficacy in eight therapeutic areas (Antibiotics, CNS: antipsychotics and antidepressants, Metabolic and GIT, Gentio-Urinary and Sex, Antiviral, Blood and blood forming agents, and Musculoskeletal) with good correlations with clinical outcome parameters. Predictions for Antiparasitic, Systemic & Hormonal, and Blood and blood forming agents should be interpreted cautiously due to the lower number of drugs analyzed in these categories. Contributions of PD, PK and physicochemical parameters to DTI give insights for understanding drug toxicity mechanisms and are useful for identifying potentially toxic drugs and doses. DTI is intended to complement the LEI, LLE, classical drug-likeness rules, lead optimization strategies and TI heatmap grids generated during drug development. Results for the recently approved drugs generate hope for applications in drug discovery and therapeutic drug monitoring. Flowchart like decision trees for the application of DTI throughout the drug discovery process has been proposed. Limitations of the current DTI approach must be considered during such applications. Additional studies are required to further explore the utility of the DTI concept in other therapeutic areas and settings.

Funding information

No funding was received for performing this work.

Abbreviations

- TI

Therapeutic index

- LEI

Ligand efficiency index

- PK

Pharmacokinetic

- PD

Pharmacodynamic

- DTI

Drug toxicity index

- Cmax

Maximum plasma drug concentration

- IC50

Half maximal inhibitory concentration

- LTKB

Liver toxicity knowledge base

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- AChE

Acetylcholine esterase

- COX

Cyclo-oxygenase

- MAO

Monoamine-oxidase

- RO5

Rule of five

- RO2

Rule of two

- RO2-RM

Rule of two-reactive metabolite

- nM

Nanomolar

- μM

Micromolar

- Cmin

Minimum plasma drug concentration

- Ceff

Pharmacologically effective concentration

- PPB

Plasma protein binding

- free Cmax

Unbound maximum plasma drug concentration

- LE

Ligand efficiency

- DEI

Drug efficiency index

- ADME

Absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination

- ADMET

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, elimination and toxicity

- Vd

Volume of distribution

- Clog P

Calculated log P

- LLE

Lipophilic ligand efficiency

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- GIT

Gastrointestinal tract

- DILI

Drug induced liver injury

- WHO ATC

World Health Organization anatomical therapeutic chemical classification

- PDE5

Phosphodiesterase 5

- PPARγ

Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma

- Kd

Dissociation rate constant

- AI

Artificial intelligence

Author contributions

VAD conceived the idea, conducted the literature search, collected data, performed analysis and wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Word file with ANOVA analysis for WHO ATC drugs, discussion on potentially toxic drugs from the remaining categories, detailed methodology for data collection and analysis, tables with relative efficacy/toxicity data, average values and performance of the different parameters considered, and pairwise t-test data for different drug categories. Microsoft Excel files containing raw data, DTI analysis, comparison with US-FDA's LTKB database and ROC analysis. See DOI: 10.1039/c8tx00261d

References

- Muller P. Y., Milton M. N. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2012;11:751. doi: 10.1038/nrd3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurence L. B., Bruce A. C. and Bjorn C. K., Goodman and Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics, The McGraw-Hill Companies, Twelfth Ed., 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cook D., Brown D., Alexander R., March R., Morgan P., Satterthwaite G., Pangalos M. N. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2014;13:419. doi: 10.1038/nrd4309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring M. J., Arrowsmith J., Leach A. R., Leeson P. D., Mandrell S., Owen R. M., Pairaudeau G., Pennie W. D., Pickett S. D., Wang J., Wallace O., Weir A. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2015;14:475. doi: 10.1038/nrd4609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eap C. B., Buclin T., Baumann P. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2002;41:1153–1193. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200241140-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Patel V. V., Ricciotti E., Zhou R., Levin M. D., Gao E., Yu Z., Ferrari V. A., Lu M. M., Xu J., Zhang H., Hui Y., Cheng Y., Petrenko N., Yu Y., FitzGerald G. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:7548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805806106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes J., Brown A. J., Hamon J., Jarolimek W., Sridhar A., Waldron G., Whitebread S. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2012;11:909. doi: 10.1038/nrd3845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson M. P. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:817–834. doi: 10.1021/jm701122q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J. D., Blagg J., Price D. A., Bailey S., DeCrescenzo G. A., Devraj R. V., Ellsworth E., Fobian Y. M., Gibbs M. E., Gilles R. W., Greene N., Huang E., Krieger-Burke T., Loesel J., Wager T., Whiteley L., Zhang Y. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:4872–4875. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C. A. Drug Discovery Today: Technol. 2004;1:337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhoti H., Williams G., Rees D. C., Murray C. W. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2013;12:644. doi: 10.1038/nrd3926-c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Borlak J., Tong W. Hepatology. 2012;58:388–396. doi: 10.1002/hep.26208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Borlak J., Tong W. Hepatology. 2016;64:931–940. doi: 10.1002/hep.28678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J. P., Rees S., Kalindjian S. B., Philpott K. L. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;162:1239–1249. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter M. C. Future Med. Chem. 2018;10:1623–1635. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2017-0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins D. J., Bell M. A. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:6999–7010. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenlock M. C. MedChemComm. 2016;7:706–719. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins A. L., Keserü G. M., Leeson P. D., Rees D. C., Reynolds C. H. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2014;13:105. doi: 10.1038/nrd4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachez M. M., Zapata-Sudo G., Moreira O. R., Chedid N. G. B., Russo V. F. T., Russo E. M. S., Sudo R. T. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2005;49:66–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braggio S., Montanari D., Rossi T., Ratti E. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery. 2010;5:609–618. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2010.490553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanari D., Chiarparin E., Gleeson M. P., Braggio S., Longhi R., Valko K., Rossi T. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery. 2011;6:913–920. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2011.602968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Giersbergen P. L. M., Halabi A., Dingemanse J. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002;53:589–595. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonchev D. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2001;20:65–75. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(01)00101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kron T., Elliott A., Metcalfe P. Med. Phys. 1993;20:1429–1438. doi: 10.1118/1.597157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring M. J. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery. 2010;5:235–248. doi: 10.1517/17460441003605098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foye W. O., Lemke T. L. and Williams D. A., Foye's principles of medicinal chemistry, Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Duan P., Li S., Ai N., Hu L., Welsh W. J., You G. Mol. Pharm. 2012;9:3340–3346. doi: 10.1021/mp300365t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ToxTutor, https://toxtutor.nlm.nih.gov/03-002.html.

- Padma-Nathan H., Goldstein I., Klimberg I., Coogan C., Auerbach S., Lammers P., Group V. S. Int. J. Impotence Res. 2002;14:266. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogu C. C., Maxa J. L. Proc. (Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent). 2000;13:421–423. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2000.11927719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björnsson E. S., Hoofnagle J. H. Hepatology. 2015;63:590–603. doi: 10.1002/hep.28323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Ahmad J. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008;23:1914–1916. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0758-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. W., Principles and methods of toxicology, CRC Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. A., Di L., Kerns E. H. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2010;9:929. doi: 10.1038/nrd3287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler H.-G., Bloechl-Daum B., Abadie E., Barnett D., König F., Pearson S. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2010;9:277. doi: 10.1038/nrd3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Gurrin L., Ademi Z., Liew D. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013;77:116–121. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry D., Lim L. L.-Y., Rodriguez L. A. G., Gutthann S. P., Carson J. L., Griffin M., Savage R., Logan R., Moride Y., Hawkey C., Hill S., Fries J. T. Br. Med. J. 1996;312:1563. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7046.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knottnerus B. J., Grigoryan L., Geerlings S. E., Moll van Charante E. P., Verheij T. J. M., Kessels A. G. H., ter Riet G. Fam. Pract. 2012;29:659–670. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cms029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer A., Katzir I., Dekel E., Mayo A. E., Alon U. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:10442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606301113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S., Cipriani A., Spineli L., Mavridis D., Örey D., Richter F., Samara M., Barbui C., Engel R. R., Geddes J. R., Kissling W., Stapf M. P., Lässig B., Salanti G., Davis J. M. Lancet. 2013;382:951–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curto M., Girardi N., Lionetto L., Ciavarella G. M., Ferracuti S., Baldessarini R. J. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18:68. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0704-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo A. L., Zhou H. J., Teng M., Lin L., Zhao Y. J., Soh L. B., Mok Y. M., Lim B. P., Gwee K. P. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:695–712. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mearns E. S., Sobieraj D. M., White C. M., Saulsberry W. J., Kohn C. G., Doleh Y., Zaccaro E., Coleman C. I., PLoS One, 2015, 10 , e0125879 , – . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Staubli S. E. L., Schneider M. P., Kessels A. G., Ivic S., Bachmann L. M., Kessler T. M. Eur. Urol. 2015;68:674–680. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J., Zhang R., Yang Z., Lee J., Liu Y., Tian J., Qin X., Ren Z., Ding H., Chen Q., Mao C., Tang J. Eur. Urol. 2013;63:902–912. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel D. A., Snedecor S. J., Tang W. Y., Sudharshan L., Lim J. W., Cuffe R., Pulgar S., Gilchrist K. A., Camejo R. R., Stephens J., Nichols G., PLoS One, 2014, 9 , e105653 , – . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik A., Bielecki J., Krahn M., Dorian P., Hoch J., Boon H., Husereau D., Pechlivanoglou P. Clin. Pharmacol.: Adv. Appl. 2016;8:93–107. doi: 10.2147/CPAA.S105165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fretheim A., Odgaard-Jensen J., Brørs O., Madsen S., Njølstad I., Norheim O. F., Svilaas A., Kristiansen I. S., Thürmer H., Flottorp S. BMC Med. 2012;10:33. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K., Schmoll H. J., Aapro M. S. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2007;61:162–175. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison R. K. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2016;15:817. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit V. A., Bharatam P. V. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011;24:1113–1122. doi: 10.1021/tx200110h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loi C.-M., Alvey C. W., Vassos A. B., Randinitis E. J., Sedman A. J., Koup J. R. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013;39:920–926. doi: 10.1177/00912709922008533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga Z. V., Ferdinandy P., Liaudet L., Pacher P. Am. J. Physiol.: Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015;309:H1453–H1467. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00554.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeves S. G., Appajosyula S. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003;112:S69–S77. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01879-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidot H., Carey S., Allman-Farinelli M., Shackel N. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014;40:221–232. doi: 10.1111/apt.12827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein E. M., DiNardo C. D., Pollyea D. A., Fathi A. T., Roboz G. J., Altman J. K., Stone R. M., DeAngelo D. J., Levine R. L., Flinn I. W., Kantarjian H. M., Collins R., Patel M. R., Frankel A. E., Stein A., Sekeres M. A., Swords R. T., Medeiros B. C., Willekens C., Vyas P., Tosolini A., Xu Q., Knight R. D., Yen K. E., Agresta S., de Botton S., Tallman M. S. Blood. 2017;130:722. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-779405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit V. A., Lal L. A., Agrawal S. R. WIREsWIREs Comput. Mol. Sci.Comput. Mol. Sci. 2017;7:e1323. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr A., Klambauer G., Unterthiner T., Hochreiter S. Front. Environ. Sci. 2016;3:80. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.