Abstract

Human studies show that obesity is associated with vitamin D insufficiency, which contributes to obesity-related disorders. Our aim was to elucidate the regulation of vitamin D during pregnancy and obesity in a nonhuman primate species. We studied lean and obese nonpregnant and pregnant baboons. Plasma 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25-OH-D) and 1α,25-(OH)2-D metabolites were analyzed using ELISA. Vitamin D-related gene expression was studied in maternal kidney, liver, subcutaneous fat, and placental tissue using real-time PCR and immunoblotting. Pregnancy was associated with an increase in plasma bioactive vitamin D levels compared with nonpregnant baboons in both lean and obese groups. Pregnant baboons had lower renal 24-hydroxylase CYP24A1 protein and chromatin-bound vitamin D receptor (VDR) than nonpregnant baboons. In contrast, pregnancy upregulated the expression of CYP24A1 and VDR in subcutaneous adipose tissue. Obesity decreased vitamin D status in pregnant baboons (162 ± 17 vs. 235 ± 28 nM for 25-OH-D, 671 ± 12 vs. 710 ± 10 pM for 1α,25-(OH)2-D; obese vs. lean pregnant baboons, P < 0.05). Lower vitamin D status correlated with decreased maternal renal expression of the vitamin D transporter cubulin and the 1α-hydroxylase CYP27B1. Maternal obesity also induced placental downregulation of the transporter megalin (LRP2), CYP27B1, the 25-hydroxylase CYP2J2, and VDR. We conclude that baboons represent a novel species to evaluate vitamin D regulation. Both pregnancy and obesity altered vitamin D status. Obesity-induced downregulation of vitamin D transport and bioactivation genes are novel mechanisms of obesity-induced vitamin D regulation.

Keywords: adipose tissue, obesity, placenta, pregnancy, renal, vitamin D

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is an important risk factor for multiple diseases across the lifespan (3, 8, 20, 24, 28, 48). Maternal obesity in pregnancy has been associated with multiple obstetric diseases, including gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, recurrent miscarriage, stillbirth, congenital birth defects, and macrosomia (24,28). Furthermore, there are multiple data showing lifelong programming by maternal obesity of offspring childhood diseases such as asthma and adult diseases such as metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus type II, and cardiovascular diseases (3, 5, 6, 10, 20, 48). The mechanisms by which maternal obesity affects the health of the offspring have not been fully elucidated and are the goal of multiple research efforts (14, 33, 38, 40, 42, 48, 51, 52).

The vitamin D system is a potential pathway by which obesity impacts health. Human studies have shown a consistent link between obesity and vitamin D deficiency, defined as circulating levels of the stable precursor 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25-OH-D) of <50 nM (37, 41, 44). Vitamin D supplementation studies have shown potentially beneficial effects of this micronutrient on insulin sensitivity and oral glucose tolerance in adult human obese populations (23, 45, 47). However, mechanisms by which obesity alters the vitamin D system, especially during pregnancy, remain ill-defined (23, 31, 41, 45, 47). Vitamin D has well-established classic effects on bone metabolism and mineral homeostasis in addition to effects on immune, pulmonary, and cardiovascular systems (4, 7, 15, 34). In reproduction, vitamin D deficiency is also highly prevalent worldwide and has been associated with a similar set of obstetric complications as obesity, with the exception of macrosomia and birth defects (43, 49). In addition, vitamin D deficiency is associated with intrauterine growth restriction, which can also be present in obese pregnancies (10). Furthermore, in utero vitamin D deficiency, similar to maternal obesity, is linked to the development of long-term complications in the offspring such as asthma, obesity, and cardiometabolic disease (25, 26, 50). Human studies have clearly shown that maternal obesity is associated with maternal and fetal vitamin D decreased status (16, 17, 30), but further research is needed to understand obesity-mediated effects on the maternal-fetal vitamin D system as well as the effect of vitamin D supplementation on obese pregnancies’ outcomes.

Vitamin D status and metabolism change significantly during mammalian pregnancy (9, 13, 21, 35). Maternal circulating levels of active 1α,25-(OH)2-D increase severalfold from early pregnancy and remain high during the entire pregnancies in humans, sheep, and rats (9, 11, 12). However, 25-OH-D and ionized calcium levels remain similar to prepregnancy levels. The physiological and molecular mechanisms responsible for pregnancy-specific vitamin D regulation remain incompletely characterized. Our previous studies using rat models of vitamin D sufficiency and insufficiency have led us to hypothesize that adequate vitamin D status during pregnancy is achieved by an uncoupling of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) upregulation of CYP24A1 (24-hydroxylase that inactivates vitamin D). In healthy rodent pregnancies, increased activation of vitamin D to 1α,25-(OH)2-D is achieved by CYP27B1 (1α-hydroxylase, the activating enzyme) and is not followed by increased VDR-dependent upregulation of CYP24A1 because renal expression of VDR is decreased (12). In this manner, pregnancy allows for stable increases in circulating levels of bioactive vitamin D. We have found a similar mechanism of vitamin D regulation in pregnant ewes (11). Therefore, the aims of this study were to investigate the role of pregnancy and obesity on vitamin D status and vitamin D-related gene expression in baboons. We hypothesized that both pregnancy and obesity independently alter vitamin D status in an important nonhuman primate experimental species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Dietary Interventions

Baboons (Papio spp.) were maintained in an outdoor social group environment with food and water given ad libitum. Nonpregnant female nulliparous baboons of similar characteristics were randomly assigned to a control diet or a high-fat/high-energy diet ≥4 mo prepregnancy and throughout the entire pregnancy. The control diet consisted of Purina Monkey Diet delivering 12% energy from fat, 0.29% from glucose, and 0.32% from fructose with an energy content of 3.07 kcal/g. The high-fat diet consisted of Purina Monkey Diet combined with lard to provide 45% energy from fat, 4.6% from glucose, 5.6% from fructose, and 2.3% from sucrose with an energy content of 4.03 kcal/g; high fructose beverages were also available ad libitum to the high-fat diet group. Both diets contained 6.6 IU of vitamin D/g diet and equal amounts of protein, essential minerals, and other vitamins. The weight of each baboon was obtained as it crossed an electronic scale system each morning on the way to being fed (27, 32). Control and obese animals were selected based on their diet regime and weight gain before breeding. Pregnant animals (6 control, 5 obese) were studied at 163–165 days gestation (0.9 gestation; term = 185 days gestation). We also studied nonpregnant control (n = 5) and obese (n = 5) female baboons with matching ages. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Southwest National Primate Research Center and conducted in Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International-accredited facilities.

Cesarean Section, Blood, and Tissue Processing

Maternal femoral vein blood samples were collected after 12 h of fasting, following tranquilization with ketamine, and immediately before cesarean section under general anesthesia, as previously described (27, 32). Blood samples were drawn into lithium heparinized vacutainer tubes (Becton-Dickinson). Umbilical cord vein blood was collected during general anesthesia. Then the fetus was euthanized by exsanguination while under general anesthesia, the placenta was removed, and samples from the central placenta that spanned the maternal to fetal sides were collected and snap-frozen. In addition, kidney cortex, liver, and subcutaneous adipose tissue samples from pregnant baboons and age-matched nonpregnant female baboons were also obtained under generalized anesthesia, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for later analysis.

ELISA Analysis of Vitamin D Metabolites, PTH, FGF23, Calcium, and Phosphate in Plasma Samples

Plasma levels of 25-OH-D and 1α,25-(OH)2-D were analyzed using commercially available EIA kits that determine total (bound and free) levels of vitamin D metabolites (Immunodiagnostic Systems, Scottsdale, AZ). We have previously validated these ELISA kits by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis (12). Plasma levels of total calcium and phosphorus were assayed using colorimetric kits (Abcam, San Francisco, CA). Commercially available kits to detect intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH; Elabscience Biotechnology, Houston, TX) and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23; MyBiosource, San Diego, CA) from Macaca species proteins were used. Normal plasma values reported for nonpregnant women range from 50 to 200 nM of 25-OH-D, 50–195 pM 1α,25-(OH)2-D, 8.5–11.8 mg/dl of total calcium, 10–88 pg/ml iPTH, and 3–4.5 mg/dLlphosphorus (4, 7, 21, 34).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

RNA isolation, RT reaction, and real-time PCR were performed as previously described (11, 12). Exon spanning primers were designed using Ensembl genome browser sequences for olive baboons (Table 1). PCR conditions and products were confirmed by obtaining a single PCR product with the correct sequence. Negative controls were included in each run. Samples were analyzed on the CFX Connect system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using the QuantiTect SYBR green kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Gene expression was determined for β-actin (ACTB), vitamin D receptor (VDR), 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1), 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1), 25-hydroxylases CYP2R1 and CYP2J2, megalin (LRP2), cubulin (CUBN), and vitamin D-binding protein (GC). Quantitative analysis was performed with the aid of standard curves, as previously described (11, 12). Data are reported as pg mRNA divided by nanograms of the housekeeping gene ACTB.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for real-time quantitative PCR analysis

| Name | Sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ACTB | Sense: 5′-CTGCCCTGAGGCTCTCTT-3′ | ENSPANT00000028493.2 |

| Antisense: 5-AGTTTCGTGGATGCCACAG-3′ | ||

| VDR | Sense: 5′-GGCTTTGCTAAGATGATCCCAGGATT-3′ | ENSPANG00000009409.2 |

| Antisense: 5′-GATGACCTCAATGGCACTTGACTT-3′ | ||

| CYP24A1 | Sense: 5′-CAAACCGTGGAAGGCCTATC-3′ | ENSPANG00000022315.2 |

| Antisense: 5′-AGTCTTCCCCTTCCAGGATCA-3′ | ||

| CYP27B1 | Sense: 5′-GAGCTTGGCAGACATCCCAGGC-3′ | ENSPANG0000009815.2 |

| Antisense: 5′-CCCTGCACCTGCAGCTCGTGTAG-3′ | ||

| CYP2R1 | Sense: 5′-TGGCATCCTGCCTTTTGGAAA-3′ | ENSPANG00000012005.2 |

| Antisense: 5′-GCTGAGGTAGCTGAGGCTTT-3′ | ||

| CYP2J2 | Sense: 5′-TCCATCCTCGAACCCTCCTGC-3′ | ENSPANG00000002786.2 |

| Antisense: 5′-GCGCCGTCTTTTGAGAAAGT-3′ | ||

| LRP2 | Sense: 5′-CCCCATAGCAGGGATACAGA-3′ | ENSPANG00000013114.2 |

| Antisense: 5′-CGTGGAGTGTCAAAACCTCA-3′ | ||

| CUBN | Sense: 5′-GAGATGGAGGCTATGAAAAATC-3′ | ENSPANG00000022736.2 |

| Antisense: 5′-CTACTTGGGCCATCATATACAG-3′ | ||

| GC | Sense: 5′-TAGAGAGAGGCCGGGATTATG-3′ | ENSPANG00000032046.1 |

| Antisense: 5′-CTTTCACAGGACTTGGCAGA-3′ |

ACTB, β-actin; CYP24A1, 24-hydroxylase; CYP27B1, 1α-hydroxylase; CUBN, cubulin; GC, vitamin D-binding protein; LRP2, megalin; VDR, vitamin D receptor.

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

Snap-frozen placentas, kidney cortex, and subcutaneous adipose tissue samples (50 mg) were homogenized in RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris·HCl, pH = 7.4, 0.05% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, and 20% glycerol) containing fresh Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermofisher, Pittsburgh, PA), sonicated for 3 min at low frequency, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm × 10 min at 4°C. To determine the levels of nuclear and chromatin-bound VDR, we performed subcellular fractionations using a kit (Pierce; Thermofisher). Protein lysates were then analyzed by Western immune blotting, as previously described (11, 12). Briefly, the protein samples were heat denatured in Laemmli buffer, separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE), and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dried milk in 0.05% Tris-buffered saline (TBST) for 1 h and then probed in primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The following antibodies were used: monoclonal anti-VDR, rabbit polyclonal anti-VDR (C20), anti-CYP24A1 (H87), and anti-CYP27b1 (H90) (Santa Cruz Laboratory, Santa Cruz, CA) at 1:200 dilution, monoclonal anti-LRP2 (MABS489) and rabbit anti-CUBN (ABS1070) (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA) at 1:1000 dilution, monoclonal TATA-binding protein (TBP; Ab818, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) at 1:1000 dilution, and monoclonal anti-β-actin (AC-15, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 1:5,000 dilution. All of the antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer containing 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST. After three 10-min washes with TBST, the membranes were incubated with corresponding secondary antibodies diluted at 1:2,000. Bound antibodies were visualized using the chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce; ThermoFisher). Digital images were captured using the Alpha Innotech ChemiImager Imaging System and quantified using the Alpha Innotech ChemiImager 4400 software (Cell Biosciences, Santa Clara, CA). Relative LRP2, CUBN, CYP24A1, and CYP27B1 protein expression were calculated with respect to ACTB; relative VDR expression was estimated with respect to TBP levels. To compare band densitometries of the same protein between different gels, a standard sample from a nonpregnant kidney was used in every gel.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as means ± SE. We used univariate analysis to determine the differences for each variable using SPSS 22.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY). Equal variance was determined by Levene’s test. Two-way ANOVA was used to determine the significance of two independent factors (obesity and pregnancy; obesity and fetal sex), and Student’s t-test was used when obesity was the only independent factor (for placental gene expression studies) on the measured variable. To determine specific differences between each of the four groups, we used one-way ANOVA using a composite-independent factor, followed by least significant difference post hoc analysis. Statistical significance was determined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Diet-Induced Obesity During Pregnancy Leads to Decreased Vitamin D Status

We first studied vitamin D status in age-matched nonpregnant and pregnant baboons that were either lean or obese. The study group parameters are shown in Table 2. Both nonpregnant and pregnant baboons exposed to a high-fat diet had significantly higher weights than their control groups (Table 2). We analyzed vitamin D status by measuring the stable precursor 25-OH-D and the bioactive metabolite 1α,25-(OH)2-D. Intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), total calcium, and phosphate levels were also analyzed because they cross-talk with the vitamin D system (4, 7, 15, 19, 21, 34).

Table 2.

Baboon study group parameters

| Parameter | Nonpregnant Control | Nonpregnant Obese | Pregnant Control | Pregnant Obese |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 12.9 ± 1.1 | 12.1 ± 1 | 11.7 ± 0.6 | 12.8 ± 0.9 |

| Weight at end of study, kg | 16.6 ± 0.6 | 20.2 ± 0.4* | 16.7 ± 0.9 | 22.6 ± 0.7* |

| Prepregnancy weight, kg | 15.8 ± 0.9 | 20.3 ± 0.7* | ||

| Maternal weight gain, kg | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | ||

| Fetal sex (male/female ratio) | 3/2 | 2/3 | ||

| Fetal weight, g | 748 ± 49 | 813 ± 77 | ||

| Placental weight, g | 188 ± 17 | 196 ± 13 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 5.

P < 0.05, control vs. obese.

Effect of pregnancy.

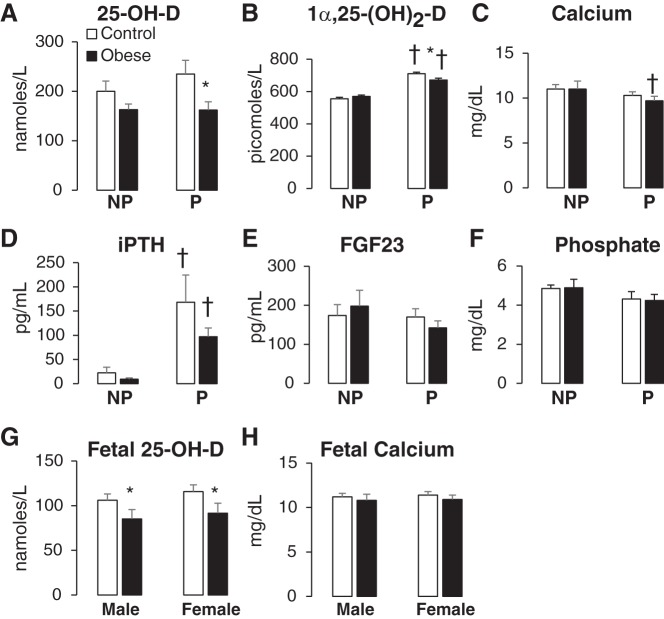

Pregnancy did not alter the levels of 25-OH-D (Fig. 1A) but induced a significant increase in the circulating levels of the bioactive metabolite 1α,25-(OH)2-D in both control and obese cohorts (28 and 18% increases over nonpregnancy values in controls and obese cohorts respectively; Fig. 1B). Pregnancy significantly decreased total calcium levels, especially in pregnant obese compared with nonpregnant obese adults (Fig. 1C). Pregnancy increased iPTH levels (Fig. 1D) but had no effect on plasma FGF23 and phosphate levels (Fig. 1, E and F).

Fig. 1.

Effects of pregnancy and obesity on vitamin D status in a baboon model. Age-matched pregnant (P) and nonpregnant (NP) baboons were fed a control or high-fat diet to induce obesity. Adult female circulating plasma levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25-OH-D; A), 1α,25-(OH)2-D (B), total calcium (C), intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH; D), fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23; E), and phosphate (F) were determined [10 NP females (5 obese and 5 lean) and 10 pregnant females (5 obese and 5 lean)]. Fetal umbilical cord plasma levels of 25-OH-D (G) and total calcium (H) of 16 female fetuses (8 control and 8 obese) and 16 male fetuses (8 control and 8 obese) were also analyzed. Data are shown as means ± SE. *P < 0.05 control vs. obese; †P < 0.05, NP vs. P.

Effect of obesity.

Diet-induced obesity was associated with decreased vitamin D status, and this effect was significant only in the pregnant cohorts, although there was a trend toward decreasing vitamin D status in nonpregnant baboons (Fig. 1, A and B). Obesity resulted in a significant 31% decrease in the stable precursor 25-OH-D plasma levels (162 ± 17 nM in obese pregnant compared with 235 ± 28 nM in control pregnant baboons, Fig. 1A). Obesity also induced a small but significant decrease in the circulating levels of bioactive vitamin D (671 ± 12 pM in obese pregnant vs. 710 ± 10 pM in control pregnant baboons, P < 0.05; Fig. 1B). Obesity did not did not alter total calcium, iPTH, FGF23, or phosphate levels (Fig. 1, C–F). Similar to the effect on adult vitamin D status, obesity also decreased 25-OH-D levels in the fetal circulation in both males and females (Fig. 1G) without affecting total calcium levels (Fig. 1H).

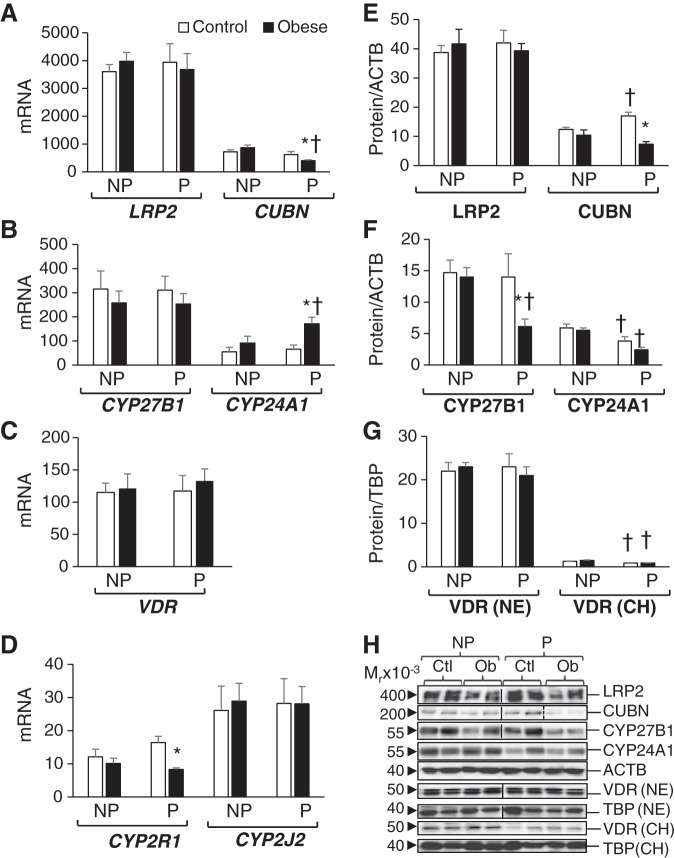

Effects of Pregnancy and Obesity on Renal Vitamin D-related Gene Expression

The kidney is the main regulator of vitamin D status in the adult, having the highest levels of expression of vitamin D-related genes (2, 22). These include the vitamin D transporters megalin (LRP2) and cubulin (CUBN), which uptake the 25-OH-D metabolite bound to the vitamin D binding protein (GC gene) and the vitamin D activating enzyme CYP27B1. The kidney also shows the highest expression of the vitamin D-catabolizing enzyme CYP24A1 and the vitamin D receptor (VDR). Similar to other mammal species, the baboon’s renal cortex had a >1,000-fold higher expression of LRP2 and CUBN than other organs such as liver, subcutaneous fat, and placenta (Figs. 2A, 3A, 4A, and 5A). There were no significant differences in megalin mRNA or protein levels between the four baboon groups (Fig. 2, A and E).

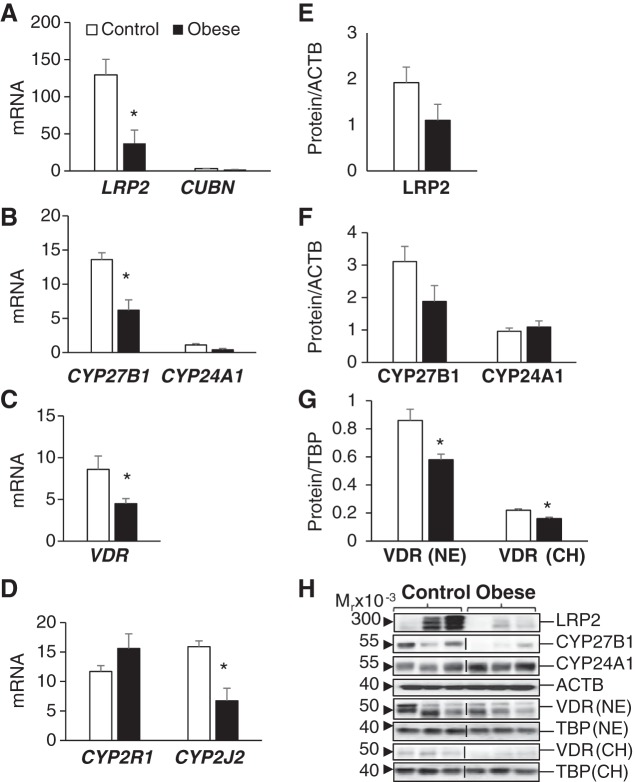

Fig. 2.

Effects of pregnancy and obesity on the adult renal vitamin D system. A–D: renal cortical mRNA levels of vitamin D transporters megalin (LRP2) and cubulin (CUBN) (A), vitamin D-metabolizing enzymes 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) and 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1) (B), vitamin D receptor (VDR; C), and 25-hydroxylases CYP2R1 and CYP2J2 (D) are shown as pg mRNA over ng of β-actin (ACTB) mRNA. Renal cortical protein expression of LRP2 and CUBN (E) and CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 (F) are shown as relative expression over ACTB expression levels. G: renal VDR protein levels in both nuclear extracts (NE) and chromatin extracts (CH) are expressed relative to TATA-binding protein (TBP) levels. H: representative immunoblots for proteins studied. Vertical lines indicate noncontiguous lanes, and dashed vertical lines indicate that the last 2 lanes were before the previous 2 lanes. Results are shown as means ± SE (n = 5/group). *P < 0.05 control vs. obese; †P < 0.05, nonpregnant (NP) vs. pregnant (P).

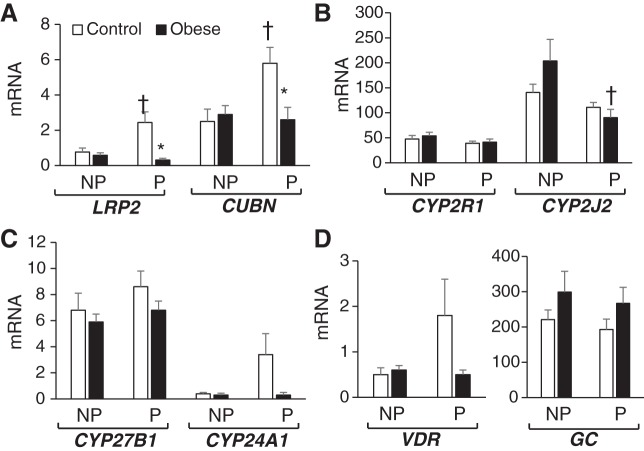

Fig. 3.

Effects of pregnancy and obesity on the adult liver vitamin D-related gene expression. Hepatic mRNA levels of vitamin D transporters megalin (LRP2) and cubulin (CUBN) (A), 25-hydroxylases CYP2R1 and CYP2J2 (B), 1α,25-(OH)2-D metabolizing enzymes 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) and 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1) (C), and vitamin D receptor (VDR) and vitamin D-binding protein (GC) (D) are shown as pg mRNA over ng of β-actin (ACTB) mRNA. Results are shown as means ± SE (n = 5/group). *P < 0.05 control vs. obese; †P < 0.05, nonpregnant (NP) vs. pregnant (P).

Fig. 4.

Effects of pregnancy and obesity on vitamin D-related gene expression of adult subcutaneous adipose tissue. A–D: adipose tissue mRNA levels of vitamin D transporters megalin (LRP2) and cubulin (CUBN) (A), vitamin D-metabolizing enzymes 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) and 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1) (B), vitamin D receptor (VDR; C), and 25-hydroxylases CYP2R1 and CYP2J2 (D) are shown as pg of mRNA over ng of β-actin (ACTB) mRNA. E and F: adipose protein expression of CUBN (E) and CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 (F) are shown as relative expression over ACTB expression levels. G: adipose VDR protein levels in both nuclear extracts (NE) and chromatin extracts (CH) are expressed relative to TATA-binding protein (TBP). H: representative immunoblots for proteins studied. Results are shown as means ± SE (n = 5/group). *P < 0.05 control vs. obese; †P < 0.05 nonpregnant (NP) vs. pregnant (P).

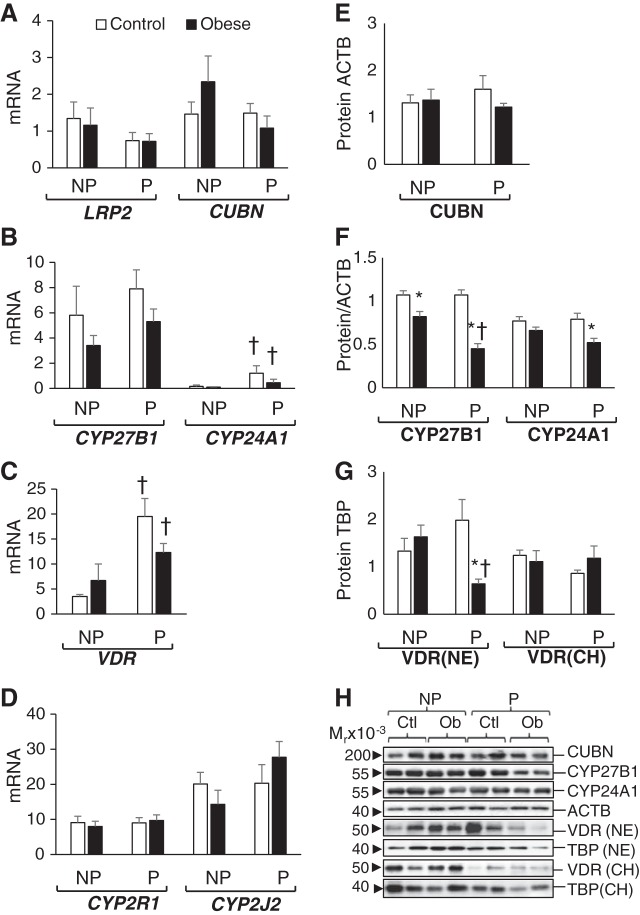

Fig. 5.

Vitamin D-related gene expression in placentas of control and obese pregnancies. A–D: placental mRNA levels of vitamin D transporters megalin (LRP2) and cubulin (CUBN) (A), vitamin D-metabolizing enzymes 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) and 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1) (B), vitamin D receptor (VDR; C), and 25-hydroxylases CYP2R1 and CYP2J2 (D) are shown as pg of mRNA over ng of β-actin (ACTB) mRNA. E and F: placental protein expression of LRP2 (E) and CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 (F) are shown as relative expression over ACTB expression levels. G: placental VDR levels in both nuclear extracts (NE) and chromatin extracts (CH) are expressed relative to the levels of TATA-binding protein (TBP). H: representative immunoblots for E, F, and G. Vertical lines indicate noncontiguous lanes. Results are shown as means ± SE (n = 5/group). *P < 0.05, control vs. obese.

Effect of pregnancy.

Pregnancy increased renal CUBN protein but not mRNA levels (Fig. 2, A and E). Pregnancy did not induce the expression of renal CYP27B1 but significantly downregulated the expression of CYP24A1 protein (Fig. 2, B and F). Renal VDR mRNA levels were similar between pregnant and nonpregnant subjects (Fig. 2C); however, there was significantly less chromatin-bound VDR in the pregnant cohorts compared with their corresponding nonpregnant cohorts (Fig. 2G).

Effect of obesity.

Obesity had no effect on renal expression of LRP2 (Fig. 2, A and E). Pregnant obese baboons had significantly lower renal expression of cubulin mRNA and protein than pregnant lean baboons (Fig. 2, A and E). Similarly, CYP27B1 protein, but not its mRNA, was significantly downregulated in obese pregnant compared with lean pregnant baboons (Fig. 2, B and F). Obese pregnant baboons had significantly higher CYP24A1 mRNA levels compared with lean pregnant baboons (Fig. 2B) but similar CYP24A1 protein levels (Fig. 2F). Obesity had no effect on renal VDR mRNA or protein expression (Fig. 2, C and G). Finally, renal CYP2R1 mRNA was significantly lower in obese pregnant compared with lean pregnant baboons, whereas there were no differences in the expression of CYP2J2 (Fig. 2D).

Effects of Pregnancy and Obesity on Liver Vitamin D-Related Gene Expression

The liver is known to be the main producer of vitamin D binding protein (VDBP; i.e., GC) and 25-hydroxylases CYP2R1 and CYP2J2, and thereby it has an important role in the homeostasis of circulating levels of 25-OH-D (4, 7, 34). In baboons, the liver also showed the highest expression of 25-hydroxylases compared with kidney, fat, and placenta (compare Fig. 3B with Figs 2D, 4D, and 5D) and abundant levels of GC mRNA (Fig. 3D). In contrast, expression of vitamin D transporters LRP2 and CUBN was >1,000-fold lower in liver than in the renal cortex (Fig. 3A vs. Fig. 2A). In addition, hepatic CYP27B1, CYP24A1, and VDR mRNA expression were more than 100-fold lower than renal mRNA levels (Fig. 2, B and C vs. Fig. 3, C and D).

Effect of pregnancy.

Pregnancy upregulated the expression of both megalin and cubulin, but only in lean baboons (Fig. 3A). Pregnancy had no effect on the liver expression of 25-hydroxylases CYP2R1 and CYP2J2, with the exception of a significant decrease in CYP2J2 expression in obese pregnant baboons compared with obese nonpregnant baboons (Fig. 3B). Pregnancy did not alter the hepatic expression of CYP27B1, CYP24A1, VDR, or GC (Fig. 3, C and D).

Effect of obesity.

Obesity did not alter the hepatic expression of the vitamin D-related genes studied. Obese pregnant baboons showed similar levels of vitamin D transporters LRP2 and CUBN as the nonpregnant subjects, whereas these genes were upregulated in pregnant control baboons. This resulted in a significantly lower expression of LRP2 and CUBN in obese pregnant baboons compared with their pregnant lean counterparts (Fig. 3A).

Effects of Pregnancy and Obesity on Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue Vitamin D-Related Gene Expression

Expression of vitamin D transporters megalin and cubulin were not different between groups (Fig. 4, A and E). Megalin protein expression was too low to quantify. Pregnancy and obesity did not affect the adipose tissue levels of CYP2R1 and CYP2J2 (Fig. 4D) or the chromatin-bound VDR protein levels (Fig. 4G) between the four baboon groups.

Effect of pregnancy.

Pregnancy induced upregulation in subcutaneous fat expression of CYP24A1 mRNA but not of CYP24A1 protein (Fig. 4, B and F). Pregnancy induced the expression of VDR (both mRNA and protein), but only in control animals; obese pregnant baboons showed higher VDR mRNA but lower nuclear protein levels (Fig. 4, C and G).

Effect of obesity.

Diet-induced obesity was associated with a lower expression of the 1α-hydroxylase CYP27B1, especially in pregnant animals (Fig. 4, B and F). Obesity also decreased the levels of CYP24A1 and VDR protein (in nuclear extracts) in pregnant baboons but not in nonpregnant baboons (Fig. 4, F and G).

Effects of Obesity on Placental Vitamin D-Related Gene Expression

The placenta is also important in regulating both maternal and fetal vitamin D status and is known to express all vitamin D-related genes (9,13.35). Placentas from obese pregnancies were characterized by lower LRP2 (Fig. 5A), lower CYP27B1 (Fig. 5B), lower VDR (Fig. 5, C and G), and lower CYP2J2 (Fig. 5D) mRNA levels compared with placentas from lean pregnancies. VDR nuclear protein levels (both free and chromatin bound) were lower in placentas from obese compared with lean pregnancies (Fig. 5G). The expression of placental cubulin was too low to quantify. Of interest is that the vitamin D catabolic enzyme CYP24A1 was not downregulated together with other vitamin D-related genes in placentas from obese pregnancies (Fig. 5, B and F). Therefore, the CYP27B1/CYP24A1 ratio decreased in obese compared with control pregnancies. The cumulative effect of these changes is that maternal obesity results in repression of the placental vitamin D system.

DISCUSSION

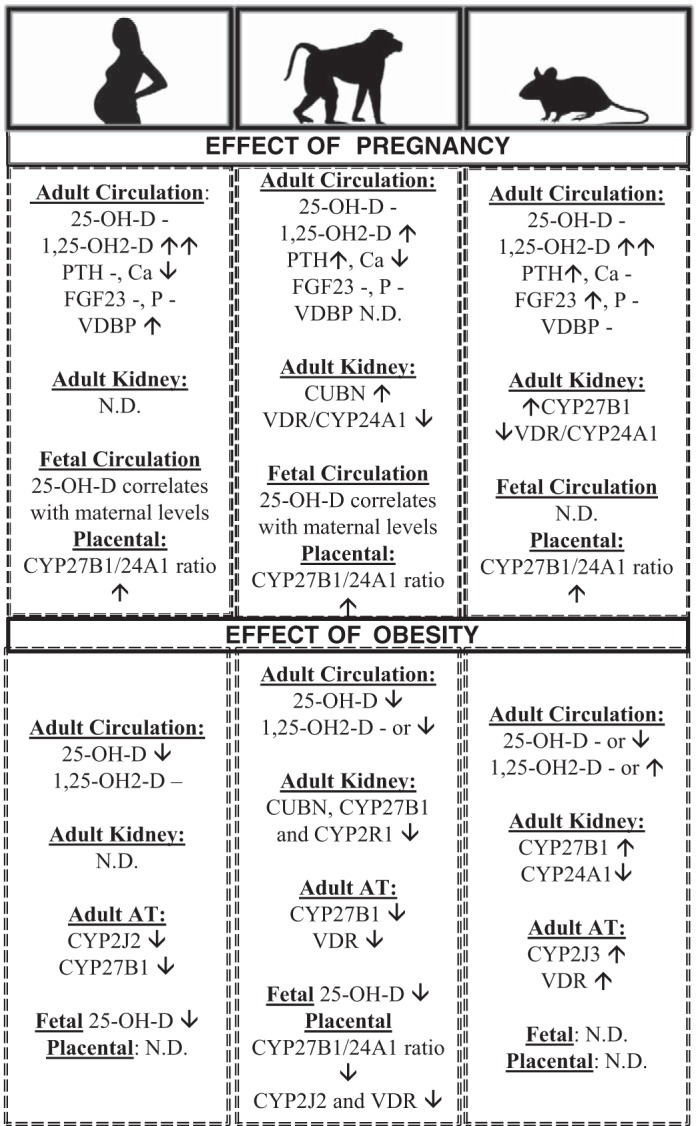

The findings on vitamin D status, transport, and metabolism presented here reveal novel aspects of regulation of the vitamin D system by pregnancy and obesity (Fig. 6). In this study, we found that nonpregnant adult baboons have more than twofold higher plasma levels of vitamin D metabolites than nonpregnant women with sufficient vitamin D status [∼200 vs. ∼70 nmol/l for 25-OH-D; and ∼500 vs. ∼100 pmol/l for 1α,25-(OH)2-D]. A previous study using radioimmunoassay found similar circulating levels of vitamin D metabolites in baboons (39). Furthermore, studies using the gold standard technique of LC-MS/MS in nonhuman primates found similar vitamin D status in other Old World primate species like Rhesus macaques (53). Therefore, the vitamin D status data presented in this study are in accord with data from other nonhuman primate studies, strengthening the validity of our data.

Fig. 6.

Summary of vitamin D regulation by pregnancy and obesity in humans, baboons, and mice. The effect of pregnancy has been determined in comparison with nonpregnancy in age-matched subjects. The effect of obesity has been determined in adults (both males and females) and in pregnant females. CUBN, cubulin; CYP24A1, 24-hydroxylase; CYP27B1, 1α-hydroxylase; FGF23, fibroblast growth factor 23; LRP2, megalin; ND, not determined; 25-OH-D, plasma 25-hydroxy vitamin D; PTH, parathyroid hormone; VDBP, vitamin D-binding protein; VDR, vitamin D receptor. -, Not changed; ↑increased; ↓decreased.

Role of Pregnancy on the Vitamin D System

It is well known that healthy mammalian pregnancy is associated with increases in the local and systemic levels of bioactive vitamin D [1α, 25-(OH)2-D] without increases in the stable precursor 25-OH-D (9,15). Potential mechanisms include increased maternal renal expression of CYP27B1 and decreased renal and placental expression of CYP24A1 (13, 22). In humans and rats, the circulating levels of bioactive vitamin D increase more than twofold within early gestation (9, 13). Baboons also showed a significant increase in circulating levels of bioactive vitamin D, although it was only 28% higher than age-matched nonpregnant female baboons (Fig. 6). In contrast with other animal models of pregnancy like the rat and the sheep, pregnancy did not increase renal expression of CYP27B1, and placental expression of CYP27B1 was significantly lower than those observed in other species (11,12,19). However, similar to other mammalian species, there was significant downregulation of renal CYP24A1 in renal cortex of pregnant compared with nonpregnant baboons (this study and Refs. 11 and 12). Therefore, we have confirmed once more that mammalian pregnancy is characterized by an uncoupling between elevations of bioactive vitamin D and VDR-dependent transcriptional activation of CYP24A1 expression. Renal CYP24A1 mRNA/protein decreases correlated with lower VDR-chromatin interactions in pregnancy. CYP24A1 uncoupling from high vitamin D status was also observed in placental tissue that showed higher expression of CYP27B1 than CYP24A1. In contrast, the classical VDR/CYP24A1 coupling was observed in maternal subcutaneous adipose tissue, where pregnancy-induced increases in vitamin D status correlated with upregulation of VDR and CYP24A1. This highly suggests that CYP24A1/vitamin D status uncoupling is tissue dependent and likely contributes to the increased vitamin D status that occurs in healthy pregnancy (Fig. 6). Therefore, tissue-dependent regulation of VDR protein expression and function is likely to be key in determining vitamin D status, as shown in VDR-null mice (2).

Role of Obesity on the Adult Vitamin D System

We have shown that diet-induced obesity is associated with significant reductions in vitamin D status and dysregulation of vitamin D-relevant gene expression in maternal and fetal tissues (Fig. 6). It is interesting that nonpregnant obese baboons were less sensitive to obesity-mediated decreases in vitamin D status, as this suggests that obesity and pregnancy interact in altering the vitamin D system. It is well established that obesity causes vitamin D deficiency in humans (37, 41). Multiple meta-analysis studies have shown that obesity is a risk factor for the development of vitamin D deficiency in humans, and reduction of body mass index (BMI) is associated with an improvement in vitamin D status (23,46). However, many questions remain, such as the mechanisms of obesity-induced dysregulation of vitamin D, the role of vitamin D deficiency in the development of obesity-related disorders, and the role of vitamin D supplementation in the prevention of obesity-related disorders.

Diet-induced obesity in baboons resulted in significant vitamin D-related gene dysregulation. In the adult kidney, obesity induced downregulation of CUBN mRNA and protein. This is of great significance, as CUBN−/− null mice have significant vitamin D deficiency due to decreased uptake of 25-OH-D bound to VDBP (18). CUBN is also the main transporter of vitamin B12; therefore, vitamin B12 deficiency is also observed in CUBN−/− null mice (18). Therefore, CUBN downregulation could be sufficient to explain the observed decreases in circulating vitamin D and vitamin B12 levels observed in obese baboons (this study and Ref. 52). Of importance is that vitamin B12 deficiency has also been observed in humans that are obese or have cardiometabolic syndrome (1). Vitamin B12 is a key micronutrient involved in one-carbon metabolism and the methyl-tetrahydrofolate pathway. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the effects of obesity on vitamin D transporters. Similar studies on human tissues are needed to define the significance of diet-induced regulation of vitamin D transporters. One human study showed that obese humans had lower CYP2J2 mRNA expression in subcutaneous adipose tissue (46), leading to the hypothesis that obesity alters the expression of 25-hydroxylases. Interestingly, the 25-hydroxylases CYP2R1 and CYP2J2 were not altered by obesity in adult baboon adipose tissue, but hepatic CYP2J2 expression was lower in obese pregnant baboons compared with nonpregnant obese baboons, indicating again that this 25-hydroxylase is regulated by obesity and pregnancy. In addition to decreased vitamin D transporter expression, obese pregnant baboons demonstrated renal and subcutaneous fat downregulation of CYP27B1 compared with the lean pregnant baboon group, which could account for the decreased levels of bioactive vitamin D observed in obese pregnant baboons. Similarly, CYP27B1 downregulation has been shown in subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese versus nonobese adult humans (46).

Role of Obesity on the Fetal and Placental Vitamin D System

Multiple animal studies have shown detrimental effects of maternal obesity on placental and fetal development in addition to long-term consequences to offspring health, but fewer studies have addressed potential mechanisms (27, 29, 32, 40). In this study, we found that maternal obesity significantly depresses the vitamin D system in fetal circulation and placental tissue. Obesity induced significant downregulation of placental vitamin D transporter LRP2 that can lead to decreased transport of other nutrients, including lipoproteins, sterols, vitamin-binding proteins, and hormones. A key finding in this study was decreased chromatin-bound VDR protein in placentas of obese pregnancies, which was uncoupled from CYP24A1 expression compared with lean pregnancies. Furthermore, maternal obesity downregulated placental CYP2J2 and CYP27B1 expression that can further contribute to suboptimal vitamin D status. Altogether, these data suggest that the fetuses of obese pregnancies are likely to also show decreased vitamin D status. In humans, maternal obesity is associated with fetal vitamin D insufficiency (7, 18, 28, 36), but the role of vitamin D in obesity-mediated effects on the health of human offspring remains unknown. Therefore, future studies on the role of vitamin D status reduction in obesity-induced fetal disorders and programming of adult disease are warranted.

Conclusion

The current study has some limitations, including the use of ELISA instead of LC-MS/MS to estimate vitamin D status, a relatively small number of animals per group, and the unavailability of baboon-specific antibodies and ELISAs to analyze some key molecules like the VDBP. On the other hand, this study showed multiple strengths, including the similarities between human and baboon pregnancy in terms of obesity effects on the vitamin D status (Fig. 6). Other mammal models of obesity have not shown decreased vitamin D status, and some obesity models even showed improved vitamin D status (36, 51). Another strength of this study is the comprehensive analysis of vitamin D status in both adult and fetal subjects and the multi-organ analysis of vitamin D-related gene expression that have identified potential novel mechanisms of vitamin D regulation in both maternal and placental tissues (Fig. 6). For instance, obesity-induced reduction of maternal vitamin D status is likely associated with both decreased vitamin D transport and bioactivation due to CUBN, CYP2J2, and CYP27B1 downregulation. Decreased vitamin D status in pregnant obese baboons then leads to decreased activation of VDR protein and interaction with chromatin. Future studies using chromatin immunoprecipitation of VDR or ChIP-seq will be helpful in understanding the effect of obesity on VDR target genes. In addition, epigenetic studies on specific vitamin D-related methylation-sensitive genes such as CYP24A1 in key tissues are warranted. Finally, the role of vitamin D insufficiency in obesity-related disorders can be determined in baboons by diet supplementation or depletion of vitamin D followed by detailed studies on well-characterized maternal and fetal obesity-induced phenotypes. Altogether, our findings show that the obese pregnant baboon is an excellent model for translational studies to determine mechanisms of obesity-induced vitamin D dysregulation and potential benefit of vitamin D supplementation in improving vitamin D status and health outcomes in human pregnancy.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grants HD-021350 to P. W. Nathanielsz and HD-083726 to E. Mata-Greenwood.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.M.-G. conceived and designed study; E.M.-G., H.F.H., and C.L. performed experiments; E.M.-G. and P.W.N. analyzed data; E.M.-G., H.F.H., C.L., and P.W.N. interpreted results of experiments; E.M.-G. prepared figures; E.M.-G. and P.W.N. drafted manuscript; E.M.-G., H.F.H., C.L., and P.W.N. edited and revised manuscript; E.M.-G., H.F.H., C.L., and P.W.N. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baltaci D, Kutlucan A, Turker Y, Yilmaz A, Karacam S, Deler H, Ucgun T, Kara IH. Association of vitamin B12 with obesity, overweight, insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, and body fat composition; primary care-based study. Med Glas (Zenica) 10: 203–210, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckman MJ, DeLuca HF. Regulation of renal vitamin D receptor is an important determinant of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) levels in vivo. Arch Biochem Biophys 401: 44–52, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burton GJ, Fowden AL, Thornburg KL. Placental Origins of Chronic Disease. Physiol Rev 96: 1509–1565, 2016. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeLuca HF. Overview of general physiologic features and functions of vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr 80, Suppl: 1689S–1696S, 2004. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1689S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desai M, Ross MG. Fetal programming of adipose tissue: effects of IUGR and maternal obesity/high fat diet. Semin Reprod Med 29: 237–245, 2011. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong M, Zheng Q, Ford SP, Nathanielsz PW, Ren J. Maternal obesity, lipotoxicity and cardiovascular diseases in offspring. J Mol Cell Cardiol 55: 111–116, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dusso AS, Brown AJ, Slatopolsky E. Vitamin D. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F8–F28, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00336.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elshenawy S, Simmons R. Maternal obesity and prenatal programming. Mol Cell Endocrinol 435: 2–6, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans KN, Bulmer JN, Kilby MD, Hewison M. Vitamin D and placental-decidual function. J Soc Gynecol Investig 11: 263–271, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gernand AD, Simhan HN, Klebanoff MA, Bodnar LM. Maternal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and measures of newborn and placental weight in a U.S. multicenter cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98: 398–404, 2013. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goyal R, Billings TL, Mansour T, Martin C, Baylink DJ, Longo LD, Pearce WJ, Mata-Greenwood E. Vitamin D status and metabolism in an ovine pregnancy model: effect of long-term, high-altitude hypoxia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 310: E1062–E1071, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00494.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goyal R, Zhang L, Blood AB, Baylink DJ, Longo LD, Oshiro B, Mata-Greenwood E. Characterization of an animal model of pregnancy-induced vitamin D deficiency due to metabolic gene dysregulation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 306: E256–E266, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00528.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray TK, Lowe W, Lester GE. Vitamin D and pregnancy: the maternal-fetal metabolism of vitamin D. Endocr Rev 2: 264–274, 1981. doi: 10.1210/edrv-2-3-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heerwagen MJR, Miller MR, Barbour LA, Friedman JE. Maternal obesity and fetal metabolic programming: a fertile epigenetic soil. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 299: R711–R722, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00310.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holick MF. Vitamin D: a D-Lightful health perspective. Nutr Rev 66, Suppl 2: S182–S194, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Josefson JL, Reisetter A, Scholtens DM, Price HE, Metzger BE, Langman CB; HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group . Maternal BMI associations with maternal and cord blood vitamin D levels in a North American subset of hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome (HAPO) study participants. PLoS One 11: e0150221, 2016. [Erratum in: PLoS One 11: e0153339, 2016]. 10.1371/journal.pone.0150221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karlsson T, Andersson L, Hussain A, Bosaeus M, Jansson N, Osmancevic A, Hulthén L, Holmäng A, Larsson I. Lower vitamin D status in obese compared with normal-weight women despite higher vitamin D intake in early pregnancy. Clin Nutr 34: 892–898, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaseda R, Hosojima M, Sato H, Saito A. Role of megalin and cubilin in the metabolism of vitamin D3. Ther Apher Dial 15, Suppl 1: 14–17, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2011.00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirby BJ, Ma Y, Martin HM, Buckle Favaro KL, Karaplis AC, Kovacs CS. Upregulation of calcitriol during pregnancy and skeletal recovery after lactation do not require parathyroid hormone. J Bone Miner Res 28: 1987–2000, 2013. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koletzko B, Brands B, Poston L, Godfrey K, Demmelmair H; Early Nutrition Project . Early nutrition programming of long-term health. Proc Nutr Soc 71: 371–378, 2012. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112000596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovacs CS. Maternal mineral and bone metabolism during pregnancy, lactation, and post-weaning recovery. Physiol Rev 96: 449–547, 2016. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar R, Tebben PJ, Thompson JR. Vitamin D and the kidney. Arch Biochem Biophys 523: 77–86, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landrier JF, Karkeni E, Marcotorchino J, Bonnet L, Tourniaire F. Vitamin D modulates adipose tissue biology: possible consequences for obesity? Proc Nutr Soc 75: 38–46, 2016. doi: 10.1017/S0029665115004164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim CC, Mahmood T. Obesity in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 29: 309–319, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lucas RM, Ponsonby AL, Pasco JA, Morley R. Future health implications of prenatal and early-life vitamin D status. Nutr Rev 66: 710–720, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erkkola M, Nwaru BI, Viljakainen HT. Maternal vitamin D during pregnancy and its relation to immune-mediated diseases in the offspring. Vitam Horm 86: 239–260, 2011. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386960-9.00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maloyan A, Muralimanoharan S, Huffman S, Cox LA, Nathanielsz PW, Myatt L, Nijland MJ. Identification and comparative analyses of myocardial miRNAs involved in the fetal response to maternal obesity. Physiol Genomics 45: 889–900, 2013. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00050.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marchi J, Berg M, Dencker A, Olander EK, Begley C. Risks associated with obesity in pregnancy, for the mother and baby: a systematic review of reviews. Obes Rev 16: 621–638, 2015. doi: 10.1111/obr.12288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcotorchino J, Tourniaire F, Astier J, Karkeni E, Canault M, Amiot MJ, Bendahan D, Bernard M, Martin JC, Giannesini B, Landrier JF. Vitamin D protects against diet-induced obesity by enhancing fatty acid oxidation. J Nutr Biochem 25: 1077–1083, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAree T, Jacobs B, Manickavasagar T, Sivalokanathan S, Brennan L, Bassett P, Rainbow S, Blair M. Vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy - still a public health issue. Matern Child Nutr 9: 23–30, 2013. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mutt SJ, Hyppönen E, Saarnio J, Järvelin MR, Herzig KH. Vitamin D and adipose tissue-more than storage. Front Physiol 5: 228, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nathanielsz PW, Yan J, Green R, Nijland M, Miller JW, Wu G, McDonald TJ, Caudill MA. Maternal obesity disrupts the methionine cycle in baboon pregnancy. Physiol Rep 3: e12564, 2015. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neri C, Edlow AG. Effects of maternal obesity on fetal programming: molecular approaches. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 6: a026591, 2016. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norman AW. From vitamin D to hormone D: fundamentals of the vitamin D endocrine system essential for good health. Am J Clin Nutr 88: 491S–499S, 2008. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.491S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novakovic B, Sibson M, Ng HK, Manuelpillai U, Rakyan V, Down T, Beck S, Fournier T, Evain-Brion D, Dimitriadis E, Craig JM, Morley R, Saffery R. Placenta-specific methylation of the vitamin D 24-hydroxylase gene: implications for feedback autoregulation of active vitamin D levels at the fetomaternal interface. J Biol Chem 284: 14838–14848, 2009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809542200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park JM, Park CY, Han SN. High fat diet-Induced obesity alters vitamin D metabolizing enzyme expression in mice. Biofactors 41: 175–182, 2015. doi: 10.1002/biof.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pereira-Santos M, Costa PRF, Assis AMO, Santos CAST, Santos DB. Obesity and vitamin D deficiency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 16: 341–349, 2015. doi: 10.1111/obr.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saben J, Lindsey F, Zhong Y, Thakali K, Badger TM, Andres A, Gomez-Acevedo H, Shankar K. Maternal obesity is associated with a lipotoxic placental environment. Placenta 35: 171–177, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Comuzzie AG, Mahaney MM, Hubbard GB, Dick EJ Jr, Kocak M, Gupta S, Carrillo M, Schenone M, Postlethwaite A, Slominski A. Serum vitamin D concentrations in baboons (Papio spp.) during pregnancy and obesity. Comp Med 66: 137–142, 2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segovia SA, Vickers MH, Gray C, Reynolds CM. Maternal obesity, inflammation, and developmental programming. BioMed Res Int 2014: 1–14, 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/418975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soskić S, Stokić E, Isenović ER. The relationship between vitamin D and obesity. Curr Med Res Opin 30: 1197–1199, 2014. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.900004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Speakman J, Hambly C, Mitchell S, Król E. Animal models of obesity. Obes Rev 8, Suppl 1: 55–61, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vandevijvere S, Amsalkhir S, Van Oyen H, Moreno-Reyes R. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women: a national cross-sectional survey. PLoS One 7: e43868, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vanlint S. Vitamin D and obesity. Nutrients 5: 949–956, 2013. doi: 10.3390/nu5030949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.vinh quốc Lu’o’ng K, Nguyễn LT. The beneficial role of vitamin D in obesity: possible genetic and cell signaling mechanisms. Nutr J 12: 89, 2013. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wamberg L, Christiansen T, Paulsen SK, Fisker S, Rask P, Rejnmark L, Richelsen B, Pedersen SB. Expression of vitamin D-metabolizing enzymes in human adipose tissue—the effect of obesity and diet-induced weight loss. Int J Obes 37: 651–657, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wamberg L, Pedersen SB, Rejnmark L, Richelsen B. Causes of vitamin D deficiency and effect of vitamin D supplementation on metabolic complications in obesity: a review. Curr Obes Rep 4: 429–440, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s13679-015-0176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wankhade UD, Thakali KM, Shankar K. Persistent influence of maternal obesity on offspring health: Mechanisms from animal models and clinical studies. Mol Cell Endocrinol 435: 7–19, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei SQ, Qi HP, Luo ZC, Fraser WD. Maternal vitamin D status and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 26: 889–899, 2013. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.765849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiss ST, Litonjua AA. The in utero effects of maternal vitamin D deficiency: how it results in asthma and other chronic diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183: 1286–1287, 2011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0160ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.West DB, York B. Dietary fat, genetic predisposition, and obesity: lessons from animal models. Am J Clin Nutr 67, Suppl: 505S–512S, 1998. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.3.505S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zambrano E, Nathanielsz PW. Mechanisms by which maternal obesity programs offspring for obesity: evidence from animal studies. Nutr Rev 71, Suppl 1: S42–S54, 2013. doi: 10.1111/nure.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ziegler TE, Kapoor A, Hedman CJ, Binkley N, Kemnitz JW. Measurement of 25-hydroxyvitamin D2&3 by tandem mass spectrometry: a primate multispecies comparison. Am J Primatol 77: 801–810, 2015. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]