Abstract

Peripheral arterial pseudoaneurysm, while relatively rare, are encountered by most vascular specialists. This review evaluates the epidemiology, diagnosis, natural history, and treatment of pseudoaneurysm in the peripheral arteries. Most of this review concentrates on iatrogenic peripheral pseudoaneurysms, but pseudoaneurysms of other etiologies will also be discussed.

Keywords: aneurysm, endovascular repair, peripheral arterial disease, percutaneous, pseudoaneurysm, ultrasound, vascular surgery

An arterial pseudoaneurysm is an interruption in the arterial wall in which blood is outside the layers of the wall and is being contained by the surrounding tissues. A pseudoaneurysm falls in a continuum of arterial hemorrhage between frank hemorrhage with rapid hematoma expansion, the most severe, and the temporary hemorrhage that subsides as a stable hematoma, the least severe. In an active pseudoaneurysm a fibrin sac develops that contains the pseudoaneurysm but also allows it to persist by separating it from extracellular signals that would often induce thrombosis. 1 Pseudoaneurysms are concerning for health care providers as there is a risk of free rupture, thromboembolism of the associated artery, extrinsic compression on adjacent neurovascular structures and surrounding tissue (skin, adipose tissue, muscle) necrosis. Therefore, treatment of them is often indicated. 2

In modern medicine, the most common cause of arterial pseudoaneurysms is complication from arterial catheterization performed for diagnostic or therapeutic interventions. Other sources of arterial pseudoaneurysms include complications arising as a result of percutaneous hemodialysis access, percutaneous intra-aortic balloon pump placement, traumas, intravenous drug injections, breakdown of surgical arterial anastomosis, and complications of central line placement. 3

The incidence of iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms is 0.44 to 1.8% following diagnostic arterial catheterization and from 3.2 to 7.7% after intervention. 1 2 In several studies evaluating all patients after femoral access for catheterization, the incidence ranges from 2.9 to 3.8%. 1 The risk of pseudoaneurysm increases with several procedure-related factors: the number of arterial accesses at the same site, urgent/emergent procedures, the increased complexity and duration of the procedure, increased sheath size, early mobilization of the limb, and the use of anticoagulation and/or antiplatelet medications during and after the procedure. 4 5 Patient factors that increase the risk of pseudoaneurysm include female sex, older age (> 75 years old) calcified arteries, increased body mass index, and thrombocytopenia. 1 3 6 7

The common femoral artery is the most common site of iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms which is due to it being the most common access site but also the thicker soft tissues allow for long, narrow necks, and provide space for the sac to develop. 4 Access of the femoral artery below the bifurcation increases the risk for pseudoaneurysms. 5 Less than 2% of iatrogenic pseudoaneurysm cases occur in the upper extremities but have higher rates of functional and neurological damage especially when the axillary artery is the site of access. 8

Diagnostic Evaluation

Diagnosis of pseudoaneurysm requires a high index of suspicion on part of the clinician. For out-patient interventions, there must also be patient education for the signs of pseudoaneurysm to watch for and return to the hospital for evaluation. The physical exam is paramount in identifying patients with pseudoaneurysms and any complaint of pain after a recent arterial access should be examined by the physician.

Pain and swelling are the most classic presentation, but bruising, pain to palpation, auscultation of a bruit, a widened pulse, and a pulsatile mass are associated with extremity pseudoaneurysms in the early state. 9 As the pseudoaneurysm enlarges adjacent structures begin to be compressed. Nerve compression may lead to limb pain or paraesthesias. Venous compression results in limb swelling and a rarely deep venous thrombosis. 1 In late stages, arterial compression leads to loss of distal pulses and limb ischemia. 9 Two laboratory studies have also been associated with the presence of a pseudoaneurysm: D-Dimer elevation and a platelet count of < 200,000/L. 1

Once the clinical exam is suspicious for a pseudoaneurysm, imaging is required for confirmatory diagnosis. Diagnostic imaging techniques, such as real-time duplex ultrasonography, computed tomography angiography (CTA), and standard angiography, can be utilized to diagnosis pseudoaneurysms. Historically angiography was used for confirmation, but now it has been replaced by real-time duplex ultrasonography due to cost, invasiveness, radiation, and contrast associated with angiography. Angiography is reserved for atypical cases and during potential interventions. 9

CTA may be useful in initial diagnosis of peripheral pseudoaneurysms if ultrasound is not readily available (middle of the night, etc.) but does not give the details that can be obtained from an ultrasound. While a contained area of bleeding and arterial injury can be noted, the exact size and neck characteristics are often not obtainable from this modality. Secondarily the patient is exposed to radiation and intravenous contrast that have their own risks. There is also greater cost with CTA over ultrasonography. Therefore, this imaging should be reserved for selected cases.

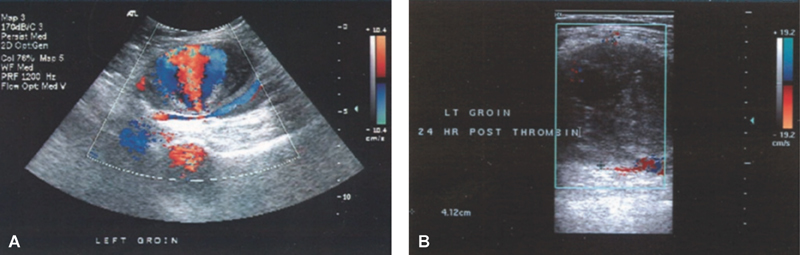

Ultrasonography has become the gold-standard in imaging peripheral artery pseudoaneurysms ( Fig. 1A ). 1 2 3 The “yin-yang sign” has become the common finding on most pseudoaneurysms that are evaluated by ultrasonography and is created by blood flow from the arterial injury into the sac that creates a swirl of motion as blood moves in with systole and out with diastole. 2 Ultrasonographic evaluation images are typically obtained with a 4 to 7 MHz linear transducer that utilizes B-mode, Doppler's waveform, and color flow to help diagnose a pseudoaneurysm and rule out the presence of an arteriovenous fistula. 1 Ultrasonography can determine the size of pseudoaneurysm, presence or absence of surrounding hematoma, length and diameter of the neck of the pseudoaneurysm, velocity of flow in the native vessel and in the pseudoaneurysm cavity, patency of surrounding vasculature, number of lobes to the sac, and compression of the vein. 1 3 9 Not only does duplex ultrasonography provide a reliable, quick imaging modality but it may also be utilized for the initial therapy (compression or thrombin injection). 1

Fig. 1.

( A ) Duplex ultrasound image of the left common femoral artery with a 5.5 pseudoaneurysm present. ( B ) Thrombosed left common femoral artery pseudoaneurysm 24 hours after thrombin injection. Source: Franz and Hughart. 14

Treatment

Treatment of limb pseudoaneurysm is done via multiple modalities and can include: observation and surveillance, ultrasound-guided compression, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, endovascular intervention, and open surgery. Each modality has its risks, benefits, and certain patient and pseudoaneurysm characteristics are more ideal for each type.

Observation and Surveillance

Pseudoaneurysms that are smaller than 2 cm can often be observed with ultrasound surveillance. 3 9 10 A repeat ultrasound is recommended at 1 week, and if there is no expansion and no symptoms then the patient can go without an intervention. 3 9 It is our practice to image the patient at least once more 1 month later. Often this has thrombosed. If not thrombosed and no expansion has occurred, a longer time period follow-up with duplex is scheduled.

Stone et al reviewed several studies from the 1990s in which femoral pseudoaneurysms were reviewed. Those studies demonstrated 58 to 100% thrombosis rates with pseudoaneurysms as large as 3.5 cm. 1 These studies demonstrated that patients on postprocedure anticoagulation, who had neck lengths less than 0.9 cm, and higher flow volumes (larger active pseudoaneurysm), were more likely to not thrombose and eventually require intervention. 1 8 11 12 Toursarkissian et al demonstrated the average time to thrombosis of pseudoaneurysm when less than 3 cm to be 23 days. 13

Compression Therapy

Ultraound-guided compression therapy has often become the initial therapy for treatment of peripheral pseudoaneurysms that are generally larger than 2 cm, but smaller than 4 cm. This therapy is also reserved for acute or subacute pseudoaneurysms that are less than 1 month old. 14 Contraindications of this procedure are infection, skin ischemia impending compartment syndrome, and inability to occlude the tract or neck without occluding native vessel. 9

This technique was first described in 1991 by Fellmeth and colleagues. 15 Duplex evaluation is used to first diagnose the pseudoaneurysm and evaluate the anatomy of the pseudoaneurysm, native artery, and the connecting neck. The ultrasound transducer is positioned to best view the pseudoaneurysm neck. Then, force is applied with transducer until flow through the tract is eliminated without compromising flow through the native artery. Direct pressure is applied for generally 30 minutes followed by slow release of the compression. Thrombosis can be checked at 10-minute intervals. If persistent flow is noted in the pseudoaneurysm the process is repeated until the process is successful with elimination of flow in the pseudoaneurysm sac. Successful compression times range from 10 to 150 minutes with a means of 30 to 53 minutes reported in the literature. 1 9 Patients are maintained on bed rest for up to 24 hours and a follow-up ultrasound is obtained at 2 and 24 hours after the compression procedure.

The success rate using ultrasound-guided compression therapy is only 60 to 93%. 14 15 16 The disadvantages of the procedure include increased time for the ultrasonographer, pain for the patient, prolonged hospital stay due to the need for multiple attempts, and postprocedure surveillance, and increased failure rates with anticoagulation. 14 Ultrasound-guided compression therapy has the advantage of a lower chance of occlusion of the native vessel due to thrombus propagation with thrombin administration and no risk of the side effects associated with the systemic injection of thrombin. 14

Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection

Ultrasound-guided thrombin injection (UGTI) has become the standard of care in treating pseudoaneurysm in stable patients with appropriate anatomy. Success of 93 to 100% has been reported ( Fig. 1B ). 1 3 14 UGTI has the advantage of minimal patient discomfort, high efficacy, ability to use with anticoagulation, ability to do in the ultrasound suite, and efficiency of the procedure. 3 This modality has the advantage of being efficacious in both acute and chronic pseudoaneurysms as it can be used in pseudoaneurysms up to 2 years old. 14

UGTI is also not impacted by anticoagulation. Schneider et al demonstrated in their series of UGTI an overall 97% efficacy of thrombin injection in all of their patients, and their anticoagulation status (19% of the patients) had no impact on the efficacy of pseudoaneurysm thrombosis. 17 In addition, Görge et al attempted to thrombose pseudoaneurysms of patients on anticoagulation with only ultrasound-guided compression and only had 17% success, but those who failed had a 93% success rate of thrombosis with UGTI. 18 Yang et al demonstrated 100% success thrombosis rate with UGTI on femoral pseudoaneurysms in patients on single antiplatelet medication, on dual antiplatelet medications, on anticoagulation and on both antiplatelet and anticoagulation. 19

Most physicians utilize 1,000 units/mL concentrations of thrombin when performing UGTI. 14 The amount of thrombin required to thrombose the pseudoaneurysm ranges from 300 to 4,000 units in the literature. 3 A more dilute concentration of 100 units/mL has been shown to be effective and therefore utilizes less thrombin with less chance for embolization into the native vessel. Taylor et al demonstrated 300 units (range: 100–600 units) were effective at thrombosing 93% of the femoral pseudoaneurysms that they treated. 16

Most published reports of UGTI treatment is in the femoral arteries (common, profunda femoral, and superficial femoral). 1 3 14 However, Jargiełło et al, in their series of pseudoaneurysm treatments, did treat a small number of upper extremity pseudoaneurysms in the brachial and radial arteries with good success. 20

Generally, it is accepted that a reasonable neck, connection tract between the sac and source artery, needs to be present to perform UGTI. Yang et al had 100% success in treating femoral pseudoaneurysms. There average neck length was 1.03 ± 0.9 cm and widths of 0.3 ± 0.1 cm. In this series 65.5% were shorter than 1 cm and 31.0% were less than 0.5 cm. In fact, they treated neck lengths as short as 0.11 cm. Length did not impact the success nor did negative complications develop with the shorter neck. 19

Overall UGTI is durable with published reoccurrences of only 3.4%. 1 Of those that recanalize after first successful UGTI, 71% had long term success with a second treatment with UGTI. 20 However, Khoury et al did report one pseudoaneurysm rupture after initially successful UGTI. 21 This modality can be used multiple times with success after the repeat administration. In addition, it appears to be very safe with reports in several series of femoral artery pseudoaneurysm treatment with no allergic reactions, 0 to 1.5% intra-arterial injections, and no embolic complications. 21 22

Endovascular Intervention

Endovascular interventions may be used in very selected cases to treat peripheral pseudoaneurysms. Often this technique is inferior to the other in both efficacy and cost compared with the other described techniques in this paper. 3 22 The most commonly described techniques utilize cover stents, direct coil embolization, or bare stents with coils placed through them. 22 23 This technique is utilized more often for arteriovenous fistulas in the periphery and emergent free ruptures. 23 This technique would be considered for pseudoaneurysms in patients who have failed compression and/or thrombin injection or who are not candidates for this procedure and are very high risk for open surgery.

Surgery

Surgery is still the definitive repair for peripheral artery pseudoaneurysms. While only utilized now in select situations, it is usually reserved for complex pseudoaneurysms with multiple lobes, short, or no necks that have ruptured or the patient is unstable, when overlying skin has been compromised, have vascular or nerve compromise, and may involve infection, are trauma related or for pseudoaneurysms that have failed less noninvasive therapies. 3 9 Open repair has risks include potential hemorrhage, wound infections, seromas, nerve injury, skin comprise, and anesthetic complications. 3

Huseyin et al have reported their experience with open surgical repair of iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms of the femoral arteries. Greater than 90% of surgeries were able to be performed with local anesthesia therefore avoiding the risks of general anesthesia. All repairs were accomplished with primary arterial repair and drains were placed. Success rate was 100% with no limb loss or procedure related deaths. Overall they demonstrated surgery for femoral pseudoaneurysms is safe and effective and certainly should be considered in the appropriate patients. The one drawback of this study is that this group did not utilize ultrasound compression or thombin-injection and used surgery as their first line therapy. In this group only one patient had a wound infection. By doing this they included many pseudoaneurysms that most would treat with less invasive modalities; therefore, the excellent results may not be as replicated by the patients that undergo surgical intervention in real world scenarios. 10

Noniatrogenic pseudoaneurysms often require open surgical repair due to the presence of infection or foreign materials. Luther et al published their 10-year experience with 50 patients of which most had pseudoaneurysms secondary to IV drug abuse and trauma. In this series most patients had ligation of the artery and excision of the pseudoaneurysm due to infection. They also reconstructed several patients using saphenous vein, primary repair, and a few synthetic grafts. Wound infection complicated 36% of the cases and 8% of the patients required the affected limb to be amputated. 24 San Norberto García et al presented their surgical treatment of complex pseudoaneurysm they demonstrated almost 75% complications rates. Blood transfusions, wound break down, and wound infections were the most common. Of this group 3.8% died in the perioperative period and many of these patients required prolonged hospitalizations of over 1 month. 25 These populations are more contemporary populations that are more likely to undergo surgical intervention. Overall this patient population is in high risk for complications. Wound infection rates are high. Limb loss and even death can occur in patients who require open surgical repair. Appropriate management and patient/family education should be used when treating patient with pseudoaneurysms that require open surgery.

Discussion

With several treatment modalities available physicians should try to employ a standardized approach for the care of patients with peripheral pseudoaneurysms. As most are iatrogenic in nature, we have provided an algorithm for their treatment ( Fig. 2 ). In small, asymptomatic pseudoaneurysm observation is likely the best option. In the actively bleeding patient, potentially infected, breakdown of the skin, or with no neck present, surgery is often the best option or in rare cases an endovascular intervention. For moderate size or symptomatic pseudoaneurysms utilizing ultrasound-guided compression and/or thrombin injection should be used as the primary means of therapy. When the pseudoaneurysm is from other sources, such as vascular anastomosis breakdown, infection, or trauma the options may be less and surgery should strongly be considered.

Fig. 2.

Treatment algorithm for peripheral pseudoaneurysms. Source: Shah et al. 3

Conclusion

While relatively uncommon, peripheral pseudoaneurysms will be encountered by most physicians performing vascular intervention. Iatrogenic causes are the most frequent source and therefore the busier practices will likely experience these several times a year with the frequency is as high as 3%. 1 A high clinical suspicion and utilization of duplex imaging is necessary in diagnosing patient with pseudoaneurysms. Once diagnosed therapeutic options include: observation, ultrasound-guided compression, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, and surgery. Patient condition and pseudoaneurysm characteristics will dictate which modality is the best. Once treated these patients will require follow-up to ensure continued thrombosis.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Stone P A, Campbell J E, AbuRahma A F. Femoral pseudoaneurysms after percutaneous access. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(05):1359–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chun E J. Ultrasonographic evaluation of complications related to transfemoral arterial procedures. Ultrasonography. 2018;37(02):164–173. doi: 10.14366/usg.17047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah K J, Halaharvi D R, Franz R W, Jenkins Ii J. Treatment of iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms using ultrasound-guided thrombin injection over a 5-year period. Int J Angiol. 2011;20(04):235–242. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1295521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gale S S, Scissons R P, Jones L, Salles-Cunha S X. Femoral pseudoaneurysm thrombinjection. Am J Surg. 2001;181(04):379–383. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00581-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mlekusch W, Haumer M, Mlekusch I et al. Prediction of iatrogenic pseudoaneurysm after percutaneous endovascular procedures. Radiology. 2006;240(02):597–602. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2402050907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayhan E, Isik T, Uyarel H et al. Femoral pseudoaneurysm in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: incidence, clinical course and risk factors. Int Angiol. 2012;31(06):579–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoke M, Koppensteiner R, Schillinger M et al. D-dimer testing in the diagnosis of transfemoral pseudoaneurysm after percutaneous transluminal procedures. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52(02):383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.02.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paulson E K, Hertzberg B S, Paine S S, Carroll B A. Femoral artery pseudoaneurysms: value of color Doppler sonography in predicting which ones will thrombose without treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159(05):1077–1081. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.5.1414779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franklin J A, Brigham D, Bogey W M, Powell C S. Treatment of iatrogenic false aneurysms. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197(02):293–301. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huseyin S, Yuksel V, Sivri N et al. Surgical management of iatrogenic femoral artery pseudoaneurysms: a 10-year experience. Hippokratia. 2013;17(04):332–336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kent K C, McArdle C R, Kennedy B, Baim D S, Anninos E, Skillman J J.A prospective study of the clinical outcome of femoral pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulas induced by arterial puncture J Vasc Surg 19931701125–131., discussion 131–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samuels D, Orron D E, Kessler A et al. Femoral artery pseudoaneurysm: Doppler sonographic features predictive for spontaneous thrombosis. J Clin Ultrasound. 1997;25(09):497–500. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0096(199711/12)25:9<497::aid-jcu6>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toursarkissian B, Allen B T, Petrinec Det al. Spontaneous closure of selected iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulae J Vasc Surg 19972505803–808., discussion 808–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franz R W, Hughart C. Delayed pseudoaneurysm repair: a case report. Int J Angiol. 2007;16(03):119–120. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1278263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fellmeth B D, Roberts A C, Bookstein J J et al. Postangiographic femoral artery injuries: nonsurgical repair with US-guided compression. Radiology. 1991;178(03):671–675. doi: 10.1148/radiology.178.3.1994400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor B S, Rhee R Y, Muluk S et al. Thrombin injection versus compression of femoral artery pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(06):1052–1059. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider C, Malisius R, Küchler R et al. A prospective study on ultrasound-guided percutaneous thrombin injection for treatment of iatrogenic post-catheterisation femoral pseudoaneurysms. Int J Cardiol. 2009;131(03):356–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Görge G, Kunz T, Kirstein M. A prospective study on ultrasound-guided compression therapy or thrombin injection for treatment of iatrogenic false aneurysms in patients receiving full-dose anti-platelet therapy. Z Kardiol. 2003;92(07):564–570. doi: 10.1007/s00392-003-0919-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang E Y, Tabbara M M, Sanchez P G et al. Comparison of ultrasound-guided thrombin injection of iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms based on neck dimension. Ann Vasc Surg. 2018;47:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2017.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jargiełło T, Sobstyl J, Światłowski Ł et al. Ultrasound-guided thrombin injection in the management of pseudoaneurysm after percutaneous arterial access. J Ultrason. 2018;18(73):85–89. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2018.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khoury M, Rebecca A, Greene K et al. Duplex scanning-guided thrombin injection for the treatment of iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35(03):517–521. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.120029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stone P A, Aburahma A F, Flaherty S K. Reducing duplex examinations in patients with iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43(06):1211–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kufner S, Cassese S, Groha P et al. Covered stents for endovascular repair of iatrogenic injuries of iliac and femoral arteries. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015;16(03):156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luther A, Kumar A, Negi K NR. Peripheral arterial pseudoaneurysms–a 10-year clinical study. Indian J Surg. 2015;77 02:603–607. doi: 10.1007/s12262-013-0939-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.San Norberto García E M, González-Fajardo J A, Gutiérrez V, Carrera S, Vaquero C. Femoral pseudoaneurysms post-cardiac catheterization surgically treated: evolution and prognosis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;8(03):353–357. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2008.188623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]