Abstract

Background:

Medicaid expansion was associated with an increase in hospitalizations funded by Medicaid. Whether this increase reflects an isolated payer shift or broader changes in case-mix among hospitalized adults remains uncertain.

Reseearch Design:

Difference-in-differences analysis of discharge data from four states that expanded Medicaid in 2014 (AZ, IA, NJ, and WA) and three comparison states that did not (NC, NE, and WI).

Subjects:

All non-obstetric hospitalizations among patients aged 19–64 years of age admitted between January 2012 and December 2015.

Measures:

Outcomes included state-level per-capita rates of insurance coverage, several markers of admission severity, and admission diagnosis.

Results:

We identified 6,516,576 patients admitted during the study period. Per-capita admissions remained consistent in expansion and non-expansion states, though Medicaid-covered admissions increased in expansion states (274.6 to 403.8 per 100,000 people versus 268.9 to 262.8 per 100,000, p <0.001). There were no significant differences after Medicaid expansion in hospital utilization, based on per capita rates of patients designated emergent, admitted via the emergency department (ED), admitted via clinic, discharged within one day, or with lengths of stay ≥ 7 days. Similarly, there were no differences in diagnosis category at admission, admission severity, comorbidity burden, or mortality associated with Medicaid expansion (p>0.05 for all comparisons).

Conclusion:

Medicaid expansion was associated with a shift in payers among non-elderly hospitalized adults without significant changes in case-mix or in several markers of acuity. These findings suggest that Medicaid expansion may reduce uncompensated care without shifting admissions practices or acuity among hospitalized adults.

Keywords: Health insurance, Medicaid, hospital care, case mix

Introduction

The Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion sought to reduce rates of uninsurance among low-income Americans by expanding income eligibility for Medicaid coverage.1,2 This has resulted in improved access to primary, preventive, and specialty care among newly insured adults and an increase in the fraction of hospitalizations covered by Medicaid.3–8 Yet, it remains unclear how the rising rate of Medicaid-funded hospitalizations has influenced case-mix among hospitalized patients.9,10

There are several ways in which Medicaid expansion may have influenced admission severity and case-mix. One possibility is that Medicaid expansion may have simply shifted insurance status away from private insurance and uninsurance and towards Medicaid coverage among adults who would have been hospitalized regardless of coverage, resulting in little change in case-mix and acuity among hospitalized adults. Alternatively, Medicaid expansion may have resulted in greater hospital admissions among a sicker group of newly insured adults, with a compensatory shift towards alternative care settings for others.11 A third possibility is that the uninsured adults gaining access to Medicaid coverage under the ACA were potentially healthier than those who previously obtained coverage12,13, shifting acuity among hospitalized adults with Medicaid towards this healthier group. Each of these possibilities carries important implications for the financing of hospitals under the Affordable Care Act and for state and federal financing of inpatient care under the Medicaid program.

This study tested the hypothesis that the Affordable Care Act led to changes in case-mix among hospitalized patients. In order to test this hypothesis, the study utilized variation among states’ adoption of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion as a natural experiment. By using a difference-in-differences study design to analyze individual state-level data, this study was able to examine changing rates of selected admission characteristics, diagnoses, and outcomes over time as a way of gauging the effects of Medicaid expansion on the hospitalized population.

Methods

Data Source and Population

We performed a retrospective cohort study using hospital discharge records from seven states between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2015. Arizona, Iowa, Nebraska, New Jersey, North Carolina, Washington state, and Wisconsin were selected because they represented geographically diverse regions and differed in the adoption of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. Control states (Nebraska, North Carolina, and Wisconsin) were selected to be similar to intervention states (Arizona, Iowa, New Jersey, and Washington) across observed demographic, coverage, economic, and health resources characteristics (Supplemental Table 1). We included patients who were aged between 19 and 64 at the time of hospitalization and who resided in one of the included states. Data were obtained from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Databases (SIDs), maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The SIDs include >95% of hospital discharges from hospitals in participating states.14 United States Census annual population estimates from 2012 to 2015 were used to obtain annual state populations.15

Variable Definition

Payer was defined as the expected primary payer for a hospitalization. Diagnosis categories were obtained using the HCUP Clinical Classification Software (CCS).16 The CCS categorizes each International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) or, beginning in the fourth quarter of 2015, International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) diagnosis code, into one of eighteen specific categories. Categories of diagnoses were used over individual diagnoses to limit misclassification stemming from the ICD-9-CM to ICD-10 switch that occurred in the fourth quarter of 2015.

We also examined rates of several hospitalization characteristics corresponding to acuity. These included rates of hospital admissions receiving emergency department (ED) care (defined using charges, revenue codes, and admission source information), admissions flagged as emergent (and not “urgent” or “elective”), admissions from an ambulatory clinic, live discharge in one day or less, lengths-of-stay greater ≥ 7 days, and rates of in-hospital mortality. In a separate analysis, we generated flags corresponding to Elixhauser comorbidities and used the weights outlined by Moore et al., to generate an mortality prediction score.17,18 This Elixhauser score has been shown previously to strongly predict mortality in administrative datasets. For identification of Elixhauser comorbidities and the associated mortality score, we used data through the third quarter of 2015 to avoid introducing errors associated with the ICD-10 transition.19

A binary variable was created to identify patients as residing in a Medicaid expansion or non-expansion state. Arizona, Iowa, New Jersey, and Washington implemented the ACA’s Medicaid expansion on January 1, 2014.20 Nebraska, North Carolina, and Wisconsin did not adopt the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, although Wisconsin had previously obtained a federal waiver to implement a more modest coverage expansion.21 A binary variable was also used to classify admissions as occurring before or after January 1, 2014, when Medicaid expansion took effect.

Statistical Analysis

To account for underlying secular trends in hospital admission rates, a difference-in-differences analysis was performed.22 The difference-in-differences estimator was obtained from a linear model that included an interaction term between the binary variable indicating hospital admission in a Medicaid expansion state and the binary variable indicating admission during the expansion period. The estimator corresponded to the absolute change in rates of each outcome after Medicaid expansion in expansion versus non-expansion states. The dependent variables in each model were quarterly per-capita rates of each outcome aggregated at the state level or, for analyses among Medicaid patients alone, the fraction of Medicaid-covered admissions with each outcome. Pre-expansion trends in both the control and intervention groups were assessed using an interaction term between time in quarters prior to expansion and admission in an expansion state. (Supplemental Tables 3–5). Robust variance estimates were used to allow for clustering of observations at the state level and for heteroscedasticity. In a sensitivity analysis, we used wild cluster bootstrap standard errors given the small number of clusters (Supplemental Table 6).23 Scatterplots employed locally weighted scatterplot smoothing to account for seasonal differences.24

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) and Stata 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). All tests were two tailed, and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Because this study used publicly available, de-identified data, the project was deemed exempt from full review by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan.

Results

The study cohort included 6,516,576 total hospitalizations over the study period, including 2,716,642 hospitalizations in non-expansion states and 3,799,934 hospitalizations in expansion states. Prior to Medicaid expansion, hospitalized patients in expansion states tended to be slightly younger (median age 50 years versus 51 years), less often female (49.6% versus 50.9%), and more often uninsured (12.9% versus 11.6%) than hospitalized patients in non-expansion states (all p<0.001) (Table 1). Non-expansion states had higher baseline Medicaid coverage rates among admitted patients (18.9% versus 17.1%).

Table 1:

Patient Characteristics Prior to Expansion (n=3,317,023)

| Expansion States (n=1,938,056) | Non-Expansion States (n=1,378,967) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients | <0.001 | ||

| Age | 50 | 51 | <0.001 |

| Female | 49.6% | 50.9% | <0.001 |

| LOS | 3 | 3 | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 17.1% | 18.9% | |

| Private Insurance | 45.4% | 42.4% | <0.001 |

| Uninsured | 12.9% | 11.6% | <0.001 |

Admission Rates and Payer Trends

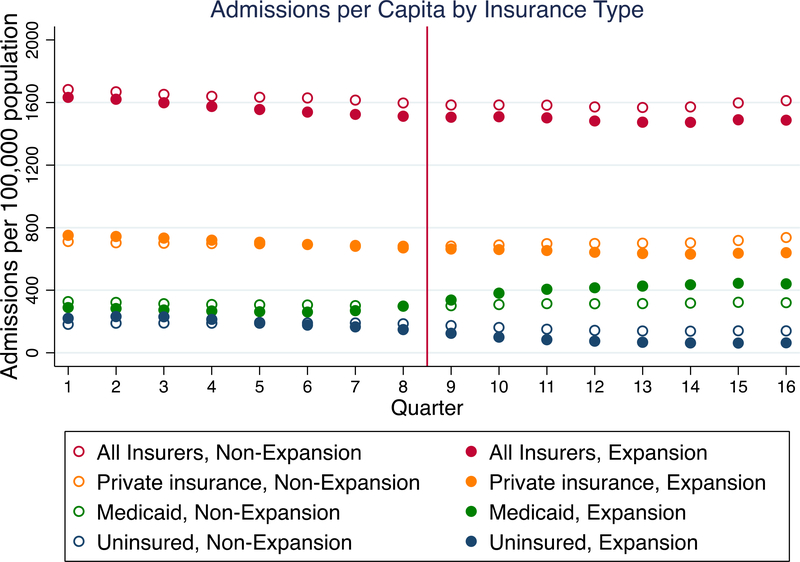

Total per-capita admissions remained stable over the study period in both expansion and non-expansion states (1,497.7 to 1,487.1 per 100,000 non-elderly adult residents in expansion states and 1,552.1 to 1,543.0 per 100,000 in non-expansion states, p=0.94), (Table 2). However, the rate of Medicaid-covered admissions increased in expansion states versus non-expansion states from 274.6 to 403.8 per 100,000 versus 268.9 to 262.8 per 100,000 (p=0.012) (Figure 1).

Table 2:

Admission Characteristics and Outcomes over Time

| Outcome (per 100,000) | Expansion States | Non-Expansion States | Difference-in-Differences, (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Expansion | Post-Expansion | Pre-expansion | Post-Expansion | |||

| Total Admissions | 1497.7 | 1487.1 | 1,552.1 | 1543.0 | −1.5 (−47.0, 44.0) | 0.94 |

| Medicaid Admissions | 274.6 | 403.8 | 268.9 | 262.8 | 135.3 (42.8, 227.8) | 0.012 |

| Admissions Designated “Emergent” | 919.9 | 920.6 | 785.7 | 804.1 | −17.7 (−90.5, 55.1) | 0.57 |

| Admissions via ED | 939.7 | 939.9 | 852.9 | 862.9 | −9.9 (−62.9, 43.2) | 0.67 |

| Admissions via Clinic | 162.7 | 127.1 | 166.3 | 139.1 | −8.4 (−109.9, 93.1) | 0.85 |

| Admissions ≤ 1 Day | 246.3 | 231.0 | 233.5 | 212.5 | 5.7 (−12.7, 24.0) | 0.48 |

| Admissions ≥ 7 Days | 282.0 | 286.2 | 287.4 | 286.2 | 5.5 (−7.6, 18.6) | 0.34 |

| Elixhauser Mortality Prediction Score (mean) | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 0.0 (−0.1, 0.2) | 0.43 |

| In-Hospital Mortality | 19.3 | 19.6 | 20.3 | 20.8 | −0.1 (−1.9, 1.6) | 0.84 |

Figure 1:

Admission volume by insurer over time, per 100,000 people. Medicaid expansion is denoted by the verticle red line.

Admission Characteristics, Outcomes, and Diagnoses

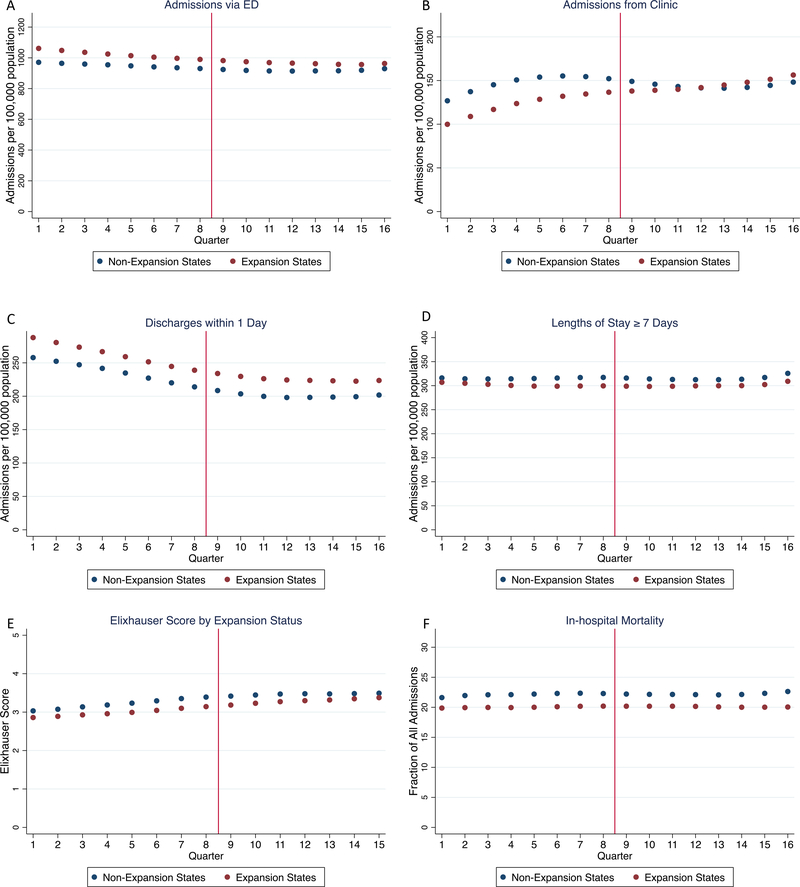

There were no significant differences after Medicaid expansion in per capita rates of patients designated ‘emergent’, admitted via the emergency department (ED), admitted via clinic, discharged within one day, or with lengths of stay ≥7 days (p>0.05 for all comparisons) (Table 2). Similarly, there were no differences in Elixhauser score (p=0.43) or in-hospital mortality (p=0.84) associated with Medicaid expansion. There were no differences in diagnosis category at admission associated with Medicaid expansion (p>0.05 for all comparisons) (Table 3).

Table 3:

Per-Capita Admission Rates over Time by Diagnosis

| Admissions (per 100,000) | Expansion States | Non-Expansion States | Difference-in-Differences (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Expansion | Post-Expansion | Pre-expansion | Post-Expansion | |||

| Infection | 72.6 | 97.8 | 63.3 | 84.6 | 2.9 (−6.8, 12.5) | 0.49 |

| Neoplasm | 85.5 | 85.8 | 85.6 | 84.4 | 1.4 (−2.2, 5.1) | 0.37 |

| Endocrine | 82.7 | 81.4 | 83.8 | 79.1 | 3.5 (−2.6, 9.7) | 0.21 |

| Hematologic | 19.8 | 20.5 | 21.4 | 21.7 | 0.4 (−1.1, 1.9) | 0.53 |

| Mental Health | 174.1 | 167.0 | 247.8 | 239.3 | 1.5 (−16.8, 19.8) | 0.85 |

| Neurologic | 53.3 | 50.9 | 50.3 | 48.6 | −0.8 (−4.6, 3.0) | 0.64 |

| Circulatory | 206.9 | 207.5 | 221.7 | 219.5 | 2.7 (−11.0, 16.5) | 0.64 |

| Respiratory | 107.3 | 123.3 | 112.5 | 132.1 | −3.6 (−12.8, 5.7) | 0.38 |

| Digestive | 209.6 | 204.8 | 192.9 | 195.5 | −7.3 (−18.4, 3.7) | 0.16 |

| Genitourinary | 79.0 | 75.2 | 70.3 | 68.2 | −1.8 (11.5, 7.9) | 0.66 |

| Dermatologic | 50.5 | 48.4 | 38.3 | 37.4 | −1.1 (3.5, 1.3) | 0.31 |

| Musculoskeletal | 131.4 | 121.7 | 139.8 | 129.3 | 0.8 (−6.1, 7.8) | 0.78 |

| Injury/Poisoning | 164.9 | 159.3 | 159.4 | 153.3 | 0.6 (−4.7, 5.9) | 0.80 |

| Ill-Defined Symptoms | 39.7 | 42.9 | 45.5 | 48.6 | 0.1 (−3.8, 3.9) | 0.97 |

Characteristics Among Medicaid Patients

When limited to Medicaid-covered hospitalizations, Medicaid expansion was associated with a statistically significant though small 1.2% increase in the fraction of patients discharged within one day (p=0.04). Otherwise, there were no differences in rates of admission via the ED, clinic, lengths of stay ≥7 days, Elixhauser score, or in-hospital mortality (p>0.05 for all comparisons) (Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

Using a large cohort of hospitalized patients in seven states, we found that Medicaid expansion was associated with a payer shift among hospitalized non-elderly adults, with no significant changes in case-mix or comorbidities. Specifically, total admissions remained stable over the study period in both expansion and non-expansion states, while Medicaid-covered admissions increased in expansion relative to non-expansion states. Meanwhile, there were no significant post-expansion differences between expansion and non-expansion states in rates of emergent admission, admissions from clinic, rapid discharges, or lengthy hospitalizations. Furthermore, there were no differences in a previously-validated mortality prediction score based on Elixhauser comorbidities in observed mortality.18 Together, these findings suggest that Medicaid expansion was not associated with a shift in admissions practices or acuity among hospitalized non-elderly adults.

This study extends the findings of prior work revealing a decline in uncompensated hospital care in states that expanded Medicaid.25–28 Specifically, several studies have revealed evidence of a shift towards Medicaid coverage from uninsurance and private insurance without a significant increase in total admissions.9,10,27 This has amounted to a $2.8 million mean decline in uncompensated care per hospital associated with Medicaid expansion through the end of 2014, contributing to a 1.1% increase in hospital profit margins.25 Though some have hypothesized that this decline in uncompensated care may have come at the cost of admitting costlier patients, our study suggests that the shift towards Medicaid coverage was not associated with significant changes in several markers of admission severity among admitted patients.

Lindrooth and colleagues found that Medicaid expansion was associated with a decline in hospital closures, particularly in rural areas and in areas with high rates of baseline uninsurance.29 Notably, the ACA mandated an annual phased reduction in federal Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments to hospitals through 2024. The DSH payments, initially established in 1981 for Medicaid and 1986 for Medicare, were designed to defray the added costs to hospitals providing uncompensated care to large numbers of low-income patients.30 Under the ACA, DSH payments are slated to decline by $2 billion in 2018, with ongoing cuts by $1 billion annually to $8 billion in 2024.31 Our findings supports prior work suggesting that Medicaid expansion may indeed compensate for declining DSH payments in expansion states, at least at the state level, as rates of uncompensated care declined in expansion states without simultaneous changes in the hospitalized population that may make caring for Medicaid patients costlier. Future work should evaluate the effects of declining DSH payments on hospitals in non-expansion states that will not experience the payer shift seen in expansion states.

Notably, we found differences in the pre-expansion trends in the number of Medicaid-covered hospitalizations between expansion and non-expansion states, violating the parallel trends assessment for this particular outcome and potentially leading to misleading results in our difference-in-differences estimates. Though this may affect our estimates, other studies have similarly reported increases in Medicaid-covered hospitalizations after Medicaid expansion, and so these findings are unlikely to be due to issues with our analytical strategy alone.9,10 We hypothesize that the reasons behind this pre-expansion difference between expansion and non-expansion states includes the “welcome-mat” effect, whereby previously eligible (though unenrolled) adults gained coverage after learning about anticipated changes in Medicaid eligibility.32

This study should be interpreted in the context of several important limitations. First, this study included seven states, limiting generalizability to the entire country, particularly among states that differed significantly in baseline rates of uninsurance. Nonetheless, the selected states included a large population of patients spanning multiple regions, and baseline demographic factors were representative of the broader population of expansion and non-expansion states. Second, administrative data have several inherent limitations, including misclassification of diagnoses stemming from the ICD-9-CM to ICD-10 transition. To limit the effects of this transition, we used broad categories of diagnoses represented by CCS codes and not individual diagnoses. Third, our study was limited to several characteristics thought to reflect admission acuity. Though findings using these markers were concordant, suggesting that acuity did not change significantly after Medicaid expansion, other characteristics may have yielded differing results. Additionally, our follow-up data was limited to two years after Medicaid expansion, and so would not capture delayed effects occurring after this period. As seen in Figure 1, however, Medicaid coverage among hospitalized patients increased rapidly after Medicaid expansion began, and the plotted results in Figures 2a-2f do not reveal a consistent transition point after Medicaid expansion suggestive of a delayed effect. Finally, this study identified Medicaid expansion at the state level and could not identify individual patients who gained Medicaid coverage under Medicaid expansion. Future studies with longitudinal patient-level information on insurance coverage may help clarify whether individual patient or hospital behaviors changed with regards to hospital admission decisions after Medicaid expansion.

Figure 2a-2f:

Admission characteristics and outcomes over time by expansion status (adjusted for seasonal differences). Medicaid expansion is denoted by the verticle red line.

2a: Admissions via the emergency department (ED) per 100,000 people

2b: Admissions from clinic per 100,000 people

2c: Live discharges within one day of admission per 100,000 people

2d: Hospitalizations lasting 7 days or more per 100,000 people

2e: Mean Elixhauser score among hospitalized patients

2f: In-hospital deaths per 100,000 people

In conclusion, we found that Medicaid expansion was associated with a shift in payer among hospitalized adults, with no significant changes in several markers of admission severity or admission diagnosis. These findings suggest that Medicaid expansion reduced uncompensated care without shifting admissions practices or acuity among hospitalized adults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: This work was supported, in part, by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1R01HL137816, Dr. Cooke, K23HL140165, Dr. Valley, and T32HL007749, Dr. Admon). Dr. Tipirneni is additionally supported by a K08 Clinical Scientist Development Award from the National Institute on Aging (1K08AG056591).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: No authors have conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer: The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States Government, or the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Under contract with the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, the University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation is conducting the evaluation of Medicaid expansion in Michigan (Healthy Michigan Plan) required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

References

- 1.Sommers BD, Gunja MZ, Finegold K, Musco T. Changes in self-reported insurance coverage, access to care, and health under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2015;314(4):366–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser Family Foundation. Change in the Nonelderly Adult Uninsured, 2013–2016. Analysis of the 2016 NHIS and Census Bureau Population Estimates. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wherry LR, Miller S. Early coverage, access, utilization, and health effects associated with the affordable care act medicaid expansions: A quasi-experimental study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(12):795–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sommers BD, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Changes in utilization and health among low-income adults after medicaid expansion or expanded private insurance. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1501–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon K, Soni A, Cawley J. The Impact of Health Insurance on Preventive Care and Health Behaviors: Evidence from the First Two Years of the ACA Medicaid Expansions. J Policy Anal Manag. 2017;36(2):390–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sommers BD, Maylone B, Blendon RJ, John Orav E, Epstein AM. Three-year impacts of the affordable care act: Improved medical care and health among low-income adults. Health Aff. 2017/05/19. 2017;36(6):1119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller S, Wherry LR. Health and Access to Care during the First 2 Years of the ACA Medicaid Expansions. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(10):947–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akhabue E, Pool LR, Yancy CW, Greenland P, Lloyd-Jones D. Association of State Medicaid Expansion With Rate of Uninsured Hospitalizations for Major Cardiovascular Events, 2009–2014. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(4):e181296–e181296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman S, Nikpay S, Carroll A, Simon K. Changes in inpatient payer-mix and hospitalizations following Medicaid expansion: Evidence from all-capture hospital discharge data. PLoS One. 2017;12(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pickens G, Karaca Z, Cutler E, Dworsky M, Eibner C, Moore B, et al. Changes in Hospital Inpatient Utilization Following Health Care Reform. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(4):2446–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vistnes JP, Lipton B, Miller GE. Uninsurance and Insurance Transitions Before and After 2014: Estimates for U.S., Non-Elderly Adults by Health Status, Presence of Chronic Conditions and State Medicaid Expansion Status Statistical Brief (Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (US)). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Decker SL, Kostova D, Kenney GM, Long SK. Health Status, Risk Factors, and Medical Conditions Among Persons Enrolled in Medicaid vs Uninsured Low-Income Adults Potentially Eligible for Medicaid Under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2013. June 26;309(24):2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Decker SL, Kenney GM, Long SK. Characteristics of uninsured low-income adults in states expanding vs not expanding medicaid. JAMA Intern Med. 2014. June 1;174(6):988–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz RM, Cadarette SM, Wong L, Sarrazin MSV, Rosenthal GE, Neubauer S, et al. The healthcare cost and utilization project: an overview. Appl Clin Informatics 2 2013; [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States Census Bureau. State Population Totals; Tables 2010–2016. 2017;

- 16.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Clinical Classification Software [Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp

- 17.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998. January;36(1):8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying Increased Risk of Readmission and In-hospital Mortality Using Hospital Administrative Data: The AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care. 2017;55(7):698–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khera R, Dorsey KB, Krumholz HM. Transition to the ICD-10 in the United States an emerging data chasm. Vol. 320, JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2018. p. 133–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid Expansion Enrollment: FY 2016. 2016.

- 21.Gates A, Rudowitz R. Wisconsin’s BadgerCare Program and the ACA. The Kaiser Family Foundation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimick JB, Ryan AM. Methods for evaluating changes in health care policy: The difference-in-differences approach. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2014;312(22):2401–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rokicki S, Cohen J, Fink G, Salomon JA, Landrum MB. Inference With Difference-in-Differences With a Small Number of Groups. Med Care. 2018. January;56(1):97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cleveland WS. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. J Am Stat Assoc. 1979;74(368):829–36. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blavin F Association between the 2014 medicaid expansion and US hospital finances. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2016; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dranove D, Garthwaite C, Ody C. Uncompensated Care Decreased At Hospitals In Medicaid Expansion States But Not At Hospitals In Nonexpansion States. Health Aff. 2016; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikpay S, Buchmueller T, Levy HG. Affordable care act medicaid expansion reduced uninsured hospital stays in 2014. Health Aff. 2016;35(1):106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis MM, Gebremariam A, Ayanian JZ. Changes in insurance coverage among hospitalized nonelderly adults after medicaid expansion in Michigan. Vol. 315, JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2016. p. 2617–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindrooth RC, Perraillon MC, Hardy RY, Tung GJ. Understanding the relationship between Medicaid expansions and hospital closures. Health Aff. 2018;37(1):111–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fishman LE, Bentley JD. The Evolution of Support for Safety-Net Hospitals. Health Aff. 1997;16(4):30–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Camilleri S The ACA Medicaid Expansion, Disproportionate Share Hospitals, and Uncompensated Care. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1562–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sonier J, Boudreaux MH, Blewett LA. Medicaid “welcome-mat” effect of affordable care act implementation could be substantial. Health Aff. 2013;32(7):1319–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.