Abstract

The effects of circadian misalignment and work shift on oxidative stress profile of shift workers have not been explored in the literature. The present study aimed to evaluate the role of shift work (day and night) and social jetlag - a measure of circadian misalignment - with oxidative stress markers. A cross-sectional study was performed with 79 men (21–65 years old, 27.56 ± 4.0 kg/m2) who worked the night shift (n = 37) or daytime (n = 42). The analyzed variables included anthropometric measures and determination of systemic levels of markers of oxidative damage and antioxidant defense. Social jetlag was calculated by the absolute difference between the mean sleep point on working and rest days. The night group presented higher systemic values of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances and hydrogen peroxide, and lower levels of nitrite, total antioxidant capacity, and catalase and superoxide dismutase activities in relation to the day group. However, social jetlag was not associated with oxidative stress-related biomarkers analyzed in the night group. These results suggest that the night worker has higher levels of oxidative stress damage and lower levels of antioxidant defenses, while social jetlag was not a possible responsible factor for this condition.

Introduction

In Western society, the demand for work by companies and services for 24 hours a day and seven days a week is increasing. As a result, the number of shift workers has increased massively in the last decades, corresponding to about 10% to 20% of the workforce in Europe and the United States1 and approximately 14.9% in Brazil2. However, this work modality leads to circadian misalignment3–5, which is associated with the onset of several pathological conditions such as dyslipidemia6, obesity7, metabolic syndrome8, type 2 diabetes mellitus,9 cardiovascular diseases10 and cancer11.

Currently, circadian misalignment has been measured by the calculation of social jetlag (SJL)10,12, a term used in similarity to the jetlag resulting from trans-meridional journeys. However, unlike displacement jetlag, SJL occurs chronically throughout the professional life of the individual and can lead to chronic health effects13. Indeed, SJL has been associated with biomarkers of inflammation and diseases such as diabetes and obesity14, as well as smoking, alcohol abuse and sedentary lifestyle15.

The circadian system represents a complex temporal regulatory network, which plays an important role in the synchronization of various biological processes within the organism and in its coordination with the environment. Circadian disorders, caused by work shift, may lead to the desynchronization of multiple physiological processes and the disruption of normal homeostasis in tissues16, and, with that, an increase in inflammatory activity17, disturbance in the activity of the neuroendocrine stress system18,19, reduction of immunological defenses19 and excessive formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)19,20.

ROS is a very broad term that encompasses, in addition to free radicals (hydroxyl radical, nitric oxide and superoxide radical), other non-radical species also derived from oxygen, such as hydrogen peroxide21,22. Oxidative stress, a condition that characterizes the imbalance between oxidative and antioxidant compounds, due to the excessive generation of free radicals or a deficiency in the capacity to fight them23,24, leads to the oxidation of biomolecules, with consequent loss of their biological functions and generation of homeostatic breaks that can affect the cells, tissues and organs25,26. Oxidative stress is considered a cardiometabolic risk factor27 and has been related to the pathophysiology of a wide variety of diseases28,29, many of them highly frequent in shift workers30,31.

Although these concepts are already individually established in the literature24,32, there is still limited evidence on the relationship between SJL, oxidative stress, antioxidant defenses and shift work. Given the importance of investigating the connection of oxidative stress to the health-illness relation of shift workers, this study was designed from the hypothesis that night workers present higher values of oxidative stress markers and lower levels of antioxidant defenses in relation to day workers. Also, we posited that SJL is positively associated with oxidative stress markers and negatively associated with antioxidant defenses in these workers. Thus, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the role of the work shift (day and night) and SJL on oxidative stress markers.

Results

Participant characteristics

The volunteers were between 21 and 65 years of age. There was no difference between the shifts in relation to the workers’ age (night: 42.43 ± 8.50 years; day: 43.40 ± 12.72 years, p = 0.688) and working time in the current shift (Table 1). Of the 37 night workers evaluated, 13 (35%) had daytime shifts, and only 10 (27%) did not take additional shifts. In addition, there was also no difference between the shifts in relation to body weight (night: 83.49 ± 11.73 kg; day: 81.13 ± 13.97 kg, p = 0.427), body mass index (BMI; night: 27.24 [26.05–29.64] kg/m²; day: 26.51 [24.00–28.49] kg/m², p = 0.115), waist circumference (WC; night: 97.62 ± 11.04 cm; day: 95.17 ± 11.04 cm, p = 334) and duration of physical exercise per week (night: 240.0 [157.50–330.00] min; day: 240.0 [135.00–435.00] min, p = 0.601). On the other hand, night workers presented higher workload (p < 0.001), daytime sleepiness (p = 0.002) and SJL (p < 0.001), as well as shorter sleep time in workdays (p < 0.001) in relation to day workers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Working hours per week, sleep patterns, score sleepiness, chronotype and social jetlag of employees according to shift worked.

| Night (n = 37) | Day (N = 42) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Hours/week | 57.0 [42.0–69.0] | 36.0 [36.0–40.0] | <0.001* |

| Working time (years) | 5.00 [2.00–12.5] | 4.00 [2.00–10.75] | 0.348 |

| Sleepiness Score ( Epworth ) | 10.76 ± 4.88 | 7.48 ± 4.00 | 0.002* |

| Daytime Sleepiness | 16 (43.2) | 9 (21.4) | 0.037* |

| No sleepiness | 21 (56.8) | 33 (78.6) | |

| Mean Sleep Duration (h) | |||

| Work days | 3:50 [2:22–4:27] | 6:35 [5:28–7:35] | <0.001* |

| Rest days | 7:56 ± 1:58 | 8:33 ± 1:52 | 0.170 |

| Chronotype (MSF E sc) (h) | 3:44 ± 1:00 | 3:38 ± 1:25 | 0.708 |

| Morning | 21 (56.8) | 29 (69.0) | 0.260 |

| Indifferent | 12 (32.4) | 7 (16.7) | |

| Evening | 4 (10.8) | 6 (14.3) | |

| Social Jetlag (h) | 5:07 [2:35–7:53] | 1:15 [0:45–2:02] | <0.001* |

| Yes | 32 (86.5) | 25 (59.5) | 0.011* |

| No | 5 (13.5) | 17 (40.5) | |

Values are presented as mean ± SD for normally distributed data or median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed data. Comparisons between groups were done using the Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney test, for independent samples, for data with and without normal distribution, respectively, or by the Chi-square test, for variables expressed as frequency. *p < 0.05 indicates statistically significant difference. SJL was calculated based on the absolute difference between the average sleep time on working and rest days and was dichotomically categorized as >60 min (with SJL) or <60 min (without SJL).

Comparison of parameters of oxidative stress damage and antioxidant defense between night and day workers

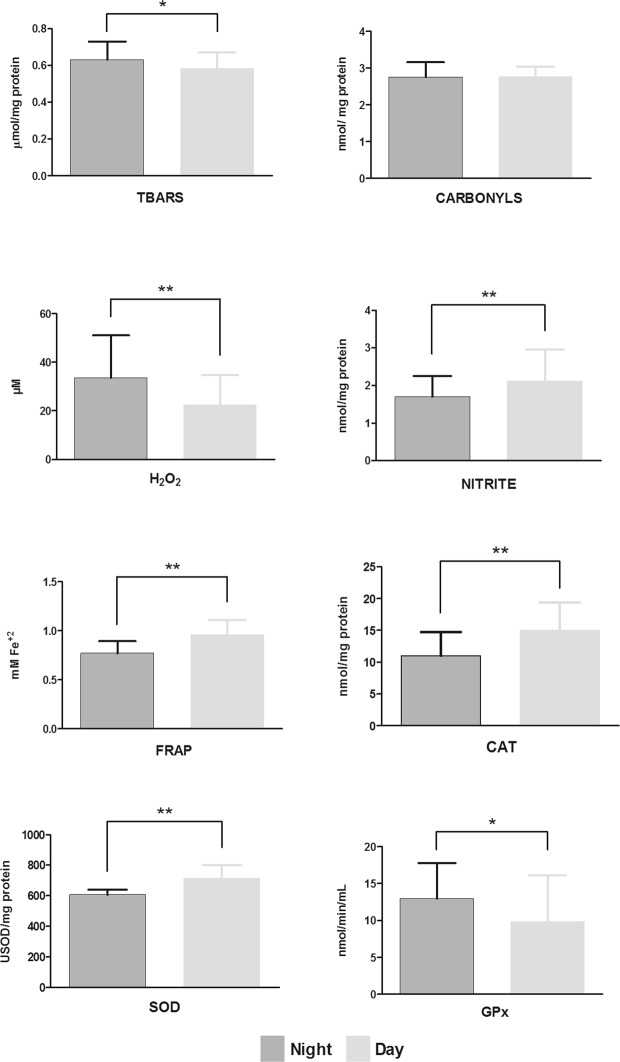

The parameters of oxidative stress between the work shifts are presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Comparison of parameters of oxidative stress damage (TBARS, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; carbonyls, plasma protein oxidation); prooxidants (H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; and nitrite) and antioxidant defense (FRAP, ferric reducing/antioxidant power; CAT, catalase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; and GPx, glutathione peroxidase) between night (dark grey) and day (light grey) workers, using Generalized Linear Model (GzLM) test, adjusted for age and working hours. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 indicates statistically significant difference.

Significantly higher values were found in night workers compared to day workers for the variables of lipoperoxidation (thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; TBARS), 0.63 [0.60–0.66] and 0.57 [0.55–0.61] µmol/mg protein (p = 0.016); H2O2, 33.55 [28.17–39.96] and 22.50 [19.11–26.49] µM (p = 0.001); and GPx, 12.97 [10.76–15.64] and 9.85 [8.23–11.79] nmol/min/mL (p = 0.037), respectively (Fig. 1).

On the other hand, significantly lower values were found in night workers in relation to day workers for the variables nitrite, 1.70 [1.51–1.91] and 2.12 [1.91–2.36] nmol/mg protein (p = 0.005); total antioxidant capacity (FRAP), 0.78 [0.73–0.83] and 0.95 [0.89–0.99] mM Fe(ii) (p < 0.001); CAT 11.07 [9.77–12.55] and 14.89 [13.27–16.70] nmol/mg protein (p = 0.003) and SOD, 609.11 [587.60–631.41] and 713.28 [688.91–738.50] USOD/mg protein (p < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 1).

Only protein oxidation values of night and day workers, 2.76 [2.65–2.87] and 2.77 [2.67–2.87] nmol/mg protein, respectively, did not differ significantly (p = 0.918).

Main effects of work shift, SJL and their interaction for parameters of oxidative damage and antioxidant defenses

Table 2 displays an effect of the work shift on the variables FRAP (p = 0.002), CAT (p = 0.034) and SOD (p < 0.001). In this analysis, significantly lower values were found in night workers compared to day workers for the variables FRAP, CAT and SOD, respectively. None of the analyses found interactions between work shift and SJL.

Table 2.

Main effects of work shift, social jetlag (SJL) and their interaction for parameters of oxidative damage and antioxidant defenses, adjusted for age and working hours.

| Night | Day | Shift | SJL | Shift*SJL | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With SJL (n = 33) | Without SJL (n = 4) | With SJL (n = 25) | Without SJL (n = 17) | DF | p-value | DF | p-value | DF | p-value | |

| TBARS (µmol/mg protein) | 0.62 [0.59–0.66] | 0.56 [0.49–0.65] | 0.58 [0.54–0.61] | 0.61 [0.57–0.66] | 1 | 0.896 | 1 | 0.468 | 1 | 0.064 |

| Carbonyls (nmol/mg protein) | 2.79 [2.66–2.93] | 2.51 [2.23–2.81] | 2.74 [2.60–2.88] | 2.79 [2.62–2.98] | 1 | 0.288 | 1 | 0.237 | 1 | 0.080 |

| H202 (µM H202) | 32.5 [26.2–40.4] | 24.5 [14.9–40.3] | 26.2 [20.9–32.9] | 18.7 [14.2–24.7] | 1 | 0.204 | 1 | 0.051 | 1 | 0.867 |

| Nitrite (nmol/mg protein) | 1.74 [1.53–1.97] | 1.64 [1.21–2.21] | 2.02 [1.77–2.30] | 2.05 [1.75–2.41] | 1 | 0.089 | 1 | 0.823 | 1 | 0.684 |

| FRAP (mM Fe+2) | 0.78 [0.73–0.83] | 0.77 [0.64–0.91] | 0.95 [0.89–1.02] | 0.95 [0.88–1.03] | 1 | 0.002* | 1 | 0.961 | 1 | 0.994 |

| CAT (nmol/mg protein) | 11.1 [9.7–12.6] | 11.6 [8.1–16.7] | 15.2 [13.2–17.4] | 14.1 [11.7–16.8] | 1 | 0.034* | 1 | 0.951 | 1 | 0.570 |

| SOD (USOD/mg protein) | 610 [587–633] | 610 [556–669] | 712 [684–742] | 697 [660–736] | 1 | <0.001* | 1 | 0.915 | 1 | 0.900 |

| GPx (nmol/min/mL) | 12.8 [10.3–16.2] | 14.4 [8.32–25.1] | 8.4 [6.6–10.8] | 11.9 [8.90–16.1] | 1 | 0.085 | 1 | 0.126 | 1 | 0.571 |

SJL was calculated based on the absolute difference between the average sleep time on working and rest days and was dichotomically categorized as >60 min (with SJL) or <60 min (without SJL).

Abbreviations: TBARS, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; carbonyls, plasma protein oxidation; H202, oxygen peroxide; FRAP, ferric reducing antioxidant power (total antioxidant capacity); CAT: catalase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GPx, glutathione peroxidase.

*p < 0.05 indicates statistically significant values. Data were represented as mean and Wald confidence interval (95% CI).

Associations between social jetlag and parameters of oxidative damage and antioxidant defense

When the variables of all volunteers were evaluated without stratification by work shift, through linear regression analysis, associations were not found. With the stratification of the volunteers per shift, a negative association between SJL and TBARS was found in day workers (β = −0.03, p = 0.013). Social jetlag was not associated with others oxidative stress-related biomarkers analyzed in day workers. Additionally, no correlations were obtained between SJL and oxidative stress parameters evaluated in the night group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Linear regression of SJL in relation to parameters of oxidative damage and antioxidant defense, adjusted for age, working hours and shift.

| Alla | Nightb | Dayb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p-value | R2 | β | p-value | R2 | β | p-value | R2 | |

| TBARS | −0.01 | 0.360 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.919 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.013* | 0.16 |

| Carbonyls | 0.01 | 0.877 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.983 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.380 | 0.03 |

| H202 | 0.62 | 0.394 | 0.15 | 0.28 | 0.775 | 0.07 | 2.56 | 0.185 | 0.07 |

| Nitrite | 0.01 | 0.953 | 0.25 | −0.01 | 0.958 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.898 | 0.20 |

| FRAP | 0.01 | 0.901 | 0.32 | −0.01 | 0.863 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.578 | 0.20 |

| CAT | −0.16 | 0.403 | 0.21 | −0.18 | 0.331 | 0.06 | 0.84 | 0.269 | 0.04 |

| SOD | −1.33 | 0.658 | 0.40 | −0.77 | 0.638 | 0.06 | −6.51 | 0.656 | 0.07 |

| GPx | −0.34 | 0.186 | 0.10 | −0.36 | 0.136 | 0.01 | −1.02 | 0.337 | 0.03 |

Abbreviations: SJL, Social Jetlag; TBARS, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances; H202, oxygen peroxide; FRAP, ferric reducing antioxidant power (total antioxidant capacity); CAT: catalase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GPx, glutathione peroxidase. aAdjusted for age and shift. bAdjusted for age and working hours.

*p < 0.05 indicates statistically significant adjustments.

Associations between sleep duration, sleep debt and parameters of oxidative damage and antioxidant defense

We performed partial Pearson correlation (adjusted for shift) between sleep duration in work days and stress parameters (TBARS: r = −0.25, p = 0.057; carbonyls: r = 0.06, p = 0.646; nitrite: r = 0.13, p = 0.331; H2O2: r = 0.13, p = 0.331; FRAP: r = 0.20, p = 0.380; CAT: r = −0.05, p = 0.716; SOD: r = 0.15, p = 0.275; GPx: r = −0.08, p = 0.543), and mean sleep duration and stress parameters (TBARS: r = −0.18, p = 0.179; carbonyls: r = −0.09, p = 0.519; nitrite: r = 0.04, p = 0.768; H2O2: r = 0.24, p = 0.067; FRAP: r = 0.05, p = 0.739; CAT: r = −0.12, p = 0.381; SOD: r = 0.17, p = 0.191; GPx: r = −0.10, p = 0.441) and no association was found. Similarly, we found no association in the partial Pearson correlation (adjusted for shift) between sleep debt and stress parameters (TBARS: r = 0.12, p = 0.358; carbonyls: r = −0.16, p = 0.243; H202: r = 0.12, p = 0.389, nitrite: r = −0.03, p = 0.827; FRAP: r = −0.12, p = 0.391; CAT: r = −0.02, p = 0.901; SOD: r = −0.09, p = 0.504; GPx: r = −0.04, p = 0.758).

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the oxidative stress profile according to the work shift and the circadian misalignment associated with SJL. The night workers had lower levels of antioxidant defense and higher levels of ROS and oxidative stress damage when compared to day workers, which confirms the initial hypothesis of this study. However, we did not find differences in relation to those variables between individuals with and without SJL or relevant associations of this chronobiological variable and the levels of antioxidant defense enzymes. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that showed that the oxidative damage markers suffer a chronic effect of night work.

Some studies have shown a reduction in total antioxidant capacity18,33 and an increase in levels of markers of oxidative stress18 after continuous hours of shift work. Indeed, the present study found that night workers presented higher values of TBARS and H2O2 and lower values of nitrite, FRAP, CAT and SOD. Thus, shift work might lead to increased oxidative stress damage (TBARS) in these workers, through an increase in ROS production (H2O2) and a reduction in enzymatic (CAT and SOD) and non-enzymatic (FRAP) antioxidant defenses. One of the possible explanations for this group’s high oxidative stress profiles may be due the lack of sleep to which these individuals are subjected. Sleep is a dynamic resting state with antioxidant properties, responsible for eliminating the ROS produced during wakefulness34,35. Thus, the normal response of oxidative stress could be impaired under conditions of sleep deprivation.

At the same time, the synthesis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) itself produces ROS, by-products formed as part of the normal aerobic metabolism of mitochondria and peroxisomes, which are neutralized by antioxidant molecules. Therefore, prolonged wakefulness requires higher metabolism to maintain the use of ATP, which necessitates an increased oxygen consumption, resulting in a significantly higher production of oxidants36. In addition, the formation of oxidants seems to be under the influence of circadian factors that regulate energetic metabolism37. Thus, a circadian misalignment could actually lead to exacerbation of ROS production as a result of changes in mitochondrial functioning36,38. In fact, the increase in ROS levels during prolonged wakefulness suggests the existence of an interrelation between redox metabolism and circadian rhythm35,39. In our study, however, we found no association between sleep duration, sleep debt and parameters of oxidative damage and antioxidant defense. We believe that the shorter sleep duration of night workers could play a role on oxidative stress parameters, but probably not in a direct and isolated way. In addition to the adaptation of biological rhythms to inversions of periods of rest and activity, these workers are also subject to a drastic change in lifestyle, which negatively influences general health, sleep and social and family interactions40. Thus, all these factors can interact and, together, take to higher levels oxidative stress of the volunteers. However, it becomes difficult to isolate a single factor associated with oxidative stress in a real-life study such as ours, given that shift workers are submitted to these different factors together. Randomized clinical trials need to be performed to test whether changes in the sleep duration/sleep debt can influence on oxidative stress in shift workers.

Considering that oxidative stress exerts a harmful effect on vital cell structures41, this would be one of the possible mechanisms for the higher incidence of disease in this population. Oxidative damage to DNA, for example, is a factor that has been related to several diseases42 and, in the face of oxidative stress, the repair of such damage is essential to prevent such disease onset. Since shift work promotes increased prooxidants but also decreased antioxidant defense - as observed in this study -, the cell is at the mercy of oxidative stress damage.

The decreased antioxidant defense in shift workers appears to occur via suppression of melatonin production43, which could - at least in part - justify the results of the present study. Indeed, some studies have shown that a key element in the relationship between work shift and oxidative stress is melatonin43–45. Endocrine changes caused by circadian rupture in shift workers result in suppression of melatonin production through artificial light exposure at night, leading to chronically reduced levels of this hormone46. Melatonin, exhibits antioxidant properties and is a powerful eliminator of ROS47. It is speculated that the increase of oxidative stress (due to constant exposure to artificial light) may be related to both the formation of ROS and the decrease in the secretion of this hormone48–50. In this sense, it is possible that it is the low level of circulating melatonin during night work, not adequately compensated for by the sleep period during the day43, that explains the association of oxidative stress with the circadian misalignment caused by the night work schedule observed in the present study. In addition, desynchronization of the biological rhythms resulting from shift work leads to deregulation of the hypothalamic-adrenal-pituitary axis, as well as its mediator, cortisol18. Such changes in cortisol levels can lead to alterations in the oxidative balance, including alterations in glutathione levels and DNA methylation51,52.

It is important to note that SJL reflects the misalignment between the endogenous circadian rhythm and the real time of sleep32 and has been associated with several metabolic risk factors, such as alterations in glycemia levels, lipid profile and adiposity10,13. In addition, both the expression and activity of antioxidant enzymes and the overall oxidative balance are synchronized with the biological rhythms53,54. In the present work, the levels of H2O2 tend to be higher in individuals with SJL (p = 0.051, Table 2), suggesting higher levels of pro oxidant induced by this condition. However, contrary to what we expected, the present study found no significant associations between the SJL and antioxidant defenses analyzing all subjects of this study or the night group. Unexpectedly, we observed a negative and significant association between SJL and TBARS only in day workers (Table 3). This finding is in contrast to the negative physiological effects associated with SJL previously reported in the literature13–15. Given the lack of studies that can be compared with our results, as well as the fact that the association between SJL and TBARS is unlike the others found in our study, we suspect that such a finding cannot be used to infer a causal relationship between the variables. In any regard, more studies should be conducted to confirm or discard this relationship found.

In fact, the findings of the present study confirm that work shift can influence the correct functioning of the antioxidant defense mechanisms55,56. It is noteworthy that SOD is an enzyme that catalyzes the formation of H2O2 from the superoxide radical. H2O2 is responsible for the formation of the hydroxyl radical, but can be removed by a reaction catalyzed by GPx or CAT19. GPx has a higher affinity for H2O2 than CAT, which means that, at low concentrations of H2O2, GPx plays a much more active role in its removal57. In this sense, it is possible that the increased GPx values in the night group may represent an unsuccessful attempt by the organism to adapt to the increased oxidative stress. Moreover, considering that CAT and GPx compete for the same substrate (H2O2), the responses of these enzymes to increased ROS could be opposite from those previously reported58. Furthermore, a loss in antioxidant protection, as verified in the present study, can generate lesions in the cells that would then be repaired with metabolic and molecular adaptive changes that, if not properly controlled, could result in apoptosis and even cell death38.

Ulas et al.28 found that the increase in oxidative stress parameters observed at the end of the night shift in health professionals was not influenced by the position or function at work, but rather by prolonged work activity and inadequate rest time. In the present study, the analyses in Fig. 1 and Table 2 were adjusted for working hours; even so, the differences of these parameters between the shifts remained. Moreover, we performed a partial correlation, adjusted for shift, between working time per week and stress parameters, and found no association with any of the variables evaluated (TBARS: r = 0.06, p = 0.651; carbonyls: r = −0.04, p = 0.780; H2O2 values: H2O2 : r = 0.13; p = 0.331, nitrite: r = −0.17, p = 0.206; FRAP: r = 0.04, p = 0.788; CAT: r = 0.02, p = 0.892; SOD: r = 0.01, p = 0.989; GPx: r = −0.02, p = 0.403; data not shown in Results section). Thus, it seems that night work promote oxidative stress, mainly affecting antioxidant defenses. It is important to mention that the studies found in the existing literature18,28,33,59 evaluated workers at different moments of the work shift (before and after), capturing only the acute effects of the same, instead of their long-term consequences. In the present study, shift workers were compared in a real-life situation, which expresses the chronic effects of shift and desynchronization of biological rhythms in the parameters of oxidative stress damage and antioxidant defense.

Another finding of this study was that night workers had higher SJL, lower average sleep time on workdays and greater daytime sleepiness, compared to daytime workers. In an intervention study, Vetter et al.5 adjusted the daytime preference of the volunteers to their work shift and found a mean reduction in SJL of 1 h 20 min (p = 0.002) and improvement in duration and quality of sleep. For these authors, SJL was found to be lower in individuals whose chronotype was in line with their working hours. Juda et al.60 showed that SJL depends on the work shift (p < 0.001). As we observed in the current study, these authors60 found higher SJL in night shift workers (p < 0.05). The results of the present study and others previously found in the literature5,15,60,61 clearly indicate the importance of aligning the individual’s chronotype to his or her work shift to minimize the differences between biological and social clocks. This can reduce SJL and, possibly, the consequences of circadian misalignment. However, such alignment is not always possible in real life conditions. In our study, for example, few individuals have an evening chronotype, which brings great difficulty to the decision of how to align chronotypes with the best or preferred shift for work.

This study presents some limitations, such as the variability in the workload among volunteers of both work shifts. For this reason, we adjusted the statistical analyses by working time per week to minimize any effect of this confounding factor. In addition, although the cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow the establishment of causal relationships, the large number of parameters analyzed allowed a better understanding of the oxidative profile in shift workers; this should serve as a basis for future research. We also emphasize, as a limitation, the high variability of sleep cycles in the workers, and the lack of a bona fide marker of circadian rhythmicity. Furthermore, the use of subjective methods those, although widely used in other studies, are dependent on participants’ memory and motivation. In this sense, replacing the questionnaires with objective alternatives - such as actigraphy in the evaluation of the sleep pattern - could provide a more reliable basis. Other limiting factors are the exclusion of female workers, which limits the impact of the current results, and the lack of evaluation of melatonin secretion, which would also help to provide a better understanding of the response of oxidative stress in shift workers. Finally, new studies and new tools will be needed to clarify how the circadian rhythm can modulate the oxidative profile, leading to a new understanding of its outcomes in the health of these workers.

In conclusion, the findings of this study indicate that night workers have lower levels of antioxidant defense and higher levels of ROS and lipoperoxidation, resulting in a condition of oxidative stress that is independent of SJL. More studies are needed to confirm these findings and to define the mechanisms underlying the relationship between shift work and oxidative stress. Preventive changes in working conditions and lifestyle are necessary to improve the health and quality of life of these workers. The effectiveness of these changes could be monitored through the evaluation of oxidative stress status.

Methods

Participants and Ethics

This study is in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and was previously approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Uberlândia. The population of this cross-sectional study was composed of male workers from two hospitals in the City of Uberlândia, MG, Brazil, aged between 21 and 65 years. The volunteers worked in the same routine for at least six months in administrative and health-related functions (nurse, physiotherapist, nursing technician, laboratory technician and stretcher bearer) and were classified according to their work shift as: (1) day workers, who worked only during the day, morning and/or afternoon, without developing any work activity at night. If these workers had an extra shift, this occurred only during the day; and (2) night workers, who worked at least six hours after midnight, with and without daytime additional work activities.

One hundred and thirty-five workers were invited to participate in the study. Individuals were excluded from the study if they: were carriers of diseases previously diagnosed and under treatment, except obesity (n = 9); had a different work shift from the two classifications of this study (n = 16) or were smokers (n = 9). In addition, 22 workers refused to participate in the study. Seventy-nine workers (37 night and 42 day workers) remained and completed all data collection. All participants had not recently used any supplements with antioxidant properties. All selected volunteers signed a free and informed consent form to participate in the study.

The volunteers who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were submitted to anthropometric, chronobiological and sleep evaluations, as well as to blood collection. In addition, data on socio-demographic characteristics, physical exercise and alcohol consumption were also collected. These assessments were made in the morning after a night’s sleep, before the work shift, as oxidative stress parameters do not appear to have important variations in the morning62. Individuals were asked to sleep through the whole night (7 to 8 hours) prior to blood collection. At the time of evaluation, blood was only collected if the participants reported that they had followed this guidance. All volunteers were submitted to the same environmental conditions at the time of collection, with artificial lighting and typical hospital noise.

Anthropometric Assessment

Body mass index (BMI, kg/m²) was calculated from the weight, measured in a scale with 0.1 kg precision (Welmy™, São Paulo, SP, Brazil), and height, measured using a wall-fixed stadiometer with 0.1 cm precision (Welmy™, São Paulo, SP, Brazil)63. Waist circumference (WC) was measured between the last costal arch and the iliac crest in volunteers with normal BMI or who were moderately overweight, as recommended by the World Health Organization63, and at the navel level in obese volunteers64.

Sleep Pattern, Chronotype and Social Jetlag

These evaluations were performed by a specialized team trained in sleep studies and were based on information compiled in the participants’ responses to a previously reported questionnaire: What time do you usually go to sleep on work days? How long (how many minutes, on average) do you stay up in bed before falling asleep (after turning off the lights) on work days? At what time do you usually wake up during work days? What time do you usually go to sleep on rest days? How long (how many minutes on average) do you stay up in bed before falling asleep (after turning off the lights) on rest days? What time do you usually wake up on rest days?65. Answers to these questions were used to account for hours of sleep on work and rest days, considering the time it took for each worker to fall asleep (sleep latency).

Sleep duration was calculated using the weighted average of the self-reported sleep duration, given by the following equation: [(sleep duration reported for working days × number of days worked in the week) + (sleep duration reported for rest days × number of rest days in the week)] ÷ 766.

The mid-sleep time on free days (MSF) of the weekend, with a sleep debt correction (MSFsc) given by the difference between the sleep duration on free days and its weekly average, was used to establish the chronotype of the daytime worker67. A specific formula proposed by Juda et al.68 was used to calculate MSFEsc and establish the chronotype of the night worker. The shift workers were categorized into early, intermediate and late chronotypes when their MSFsc values were ≤3:59 h, between 4:00 and 4:59 h and ≥5:00 h, respectively32. Social Jetlag was estimated with basis in the absolute difference between mid-sleep time on weekends and on weekdays12.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is a widely used and reliable predictor of daytime sleepiness69, therefore, its Portuguese-language version70, previously validated for use by Brazilian participants71, was used to evaluate daytime sleepiness. A total score ≥8 was considered indicative of excessive sleepiness70.

Blood Collection and Sample Preparation

Erythrocytes were washed three times with saline and stored in a preservative solution (3.98 mM MgSO4 and 0.96 mM glacial acetic acid) in an ultrafreezer at −80 °C for analysis of the activity of antioxidant defense enzymes.

Blood samples were collected by venipuncture in heparinized tubes (Vacutainer™, BD, Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil) after 12 h of fasting and immediately centrifuged at 1,300 × g for 15 min in a refrigerated centrifuge at 4 °C (Hitachi Koki™, model CFR15XRII Hitachinaka, Japan). The obtained supernatants were then frozen at −80 °C in an ultrafreezer model CUK-UB2I-PW (Panasonic™, Nijverheidsweg, the Netherlands) for further determination of the oxidative stress variables72. The erythrocytes were washed three times with saline and stored in a solution of 3.98 mM MgSO4 and 0.96 mM glacial acetic acid in an ultrafreezer at −80 °C for further determination of the activity of antioxidant enzymes. All blood samples were performed in a single moment, the morning after a night’s sleep, before the start of the work shift. The time of blood samples collection varied little between the groups studied: night: 9:00 am [8:00–9:45] and day: 8:00 am [8:00–8:45]; values are expressed in median and interquartile range. This difference occurred due to the fact that we instructed participants to maintain their usual waking hours.

Determination of Total Plasma Proteins

The protein concentration was determined according to the method previously described by Lowry et al.73, which uses bovine albumin solution at a concentration of 1 mg/ml as standard and 10 μL of sample.

Determination of Lipoperoxidation by Dosage of Thiobarbituric-Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) in Plasma

A volume of 0.75 mL of 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added to 0.25 mL of homogenate to denature its proteins and acidify the reaction medium. This solution was then stirred and centrifuged for three minutes at 1000 rpm. A mixture of 0.5 mL of its supernatant was added to 0.5 mL of 0.67% (w/v) thiobarbituric acid (TBA) was incubated at 100 °C in a thermostated water bath for 15 minutes and then cooled in an ice-water bath. Then, the absorbance generated at 535 nm, due to the reaction of the TBA with lipoperoxidation products present in the biological sample, was measured in a UV-VIS spectrophotometer74.

Determination of Protein Oxidation by Dosage of Carbonyls in Plasma

Oxidatively modified plasma proteins were determined by carbonyls quantification, based on the reaction with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) in 2.5 M HCl, followed by successive washes with organic acids and solvents and final incubation with guanidine (20% v/v TCA; 10% v/v TCA; 1:1 v:v ethanol and ethyl acetate; and 6 M guanidine in 2.5 M HCl pH 2.5)75. The absorbance at 360 nm of carbonyls was measured in a UV-VIS spectrophotometer.

Determination of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) from Erythrocytes

The determination of the SOD activity was based on the reaction of the superoxide radical with pyrogallol, with the formation of a colored product, detected spectrophotometrically at 420 nm for 2 minutes. The percentage inhibition of initial reaction rates depends on the pH and amount of SOD present in the reaction mixtures. The amount of enzyme required to inhibit the reaction by 50% was defined as one unit of SOD. The reaction mixture contained 980 μL of 50 mM tris-phosphate buffer pH 8.2, 10 μL of 24 mM pyrogallol, 5 μL of 30 mM CAT, and 5 μL of sample. A standard line with three different concentrations of SOD (0.25, 0.5 and 1 U) was obtained to determine the equation used in the calculations76.

Determination of Catalase (CAT) from Erythrocytes

The activity of CAT was determined by measuring the absorbance at 240 nm of a solution of H2O2. The decomposition rate of hydrogen peroxide is directly proportional to the activity of CAT. Catalase activity was given by peroxide consumption and expressed in nmol/mg protein.

Determination of Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) from Erythrocytes

GPx activity was expressed as nmol peroxide/hydroperoxide reduced/min/mg protein and was based on the consumption of NADPH at 480 nm77.

Determination of Total Antioxidant Capacity in Plasma

The total antioxidant capacity of the plasma was determined by the Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP), based on the production of Fe2+ (ferrous ion) from the reduction of the Fe3+ (ferric ion) present in the 2,4,6-tripyridyl-S-triazine complex (TPTZ). The reduction reaction changes the color of the medium from light purple to dark purple; this allows determination of the total reduction power of a sample by reading the absorbance at 593 nm. The assays were performed on a microplate with the addition of 290 μL of the FRAP reagent (sodium acetate and acetic acid buffer pH 3.6, 10 mM TPTZ and 20 mM ferric chloride hexahydrate) to 10 μL of ferrous sulfate heptahydrate solutions at 0, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 mM (for the standard-line construction) or 10 μL of sample (for FRAP determination by interpolation in the standard line). The microplate was incubated under stirring at 37 °C for 5 min before absorbance readings78.

Determination of Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) in Plasma

The plasma sample was initially incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in 10 mM phosphate buffer containing 140 mM NaCl and 5 mM dextrose. After adding an aliquot of this plasma treated sample to a solution containing 0.28 mM phenol red and 8.5 U/mL horseradish peroxidase (HRPO), and incubating for 5 minutes, a 1 M solution of NaOH was added, before reading of absorbance at 610 nm, which detects the oxidation product formed by the peroxidase-catalyzed reaction of H2O2 with phenol red. The results were expressed in μM of H2O279.

Determination of Total Plasma Nitrite

Total plasma nitrite was determined by reacting the plasma samples with 50 μL of Griess’s reagent and using a standard nitrite curve. Assays were performed on 96-well microplates in an ELISA reader at 592 nm80 and values were expressed as nmol/mg protein.

Statistical Analysis

Initially, the normality of the data was verified with the Shapiro-Wilk Test. Parametric data were presented as means and standard deviations and nonparametric data were presented as median and interquartile range. Comparison of proportions between groups for the variables expressed as frequency was done using the Chi-square test. The comparison between groups of variables related to socio-demographic and anthropometric characteristics, sleep patterns, drowsiness scores, chronotype, SJL, life habits and stress parameters was done using the Student’s t-test for independent samples or the Mann-Whitney Test. In addition, we performed partial Pearson correlation (adjusted for shift) between sleep duration in work days and stress parameters; mean sleep duration and stress parameters; and sleep debt and stress parameters.

The Generalized Linear Model (GzLM) was used to compare the differences of the variables of oxidative stress and antioxidant defense between shifts, adjusted for age and working time per week. The GzLM Test also was used to compare the differences of the variables of oxidative stress and antioxidant defense between shifts, SJL and shift versus SJL interaction, adjusted for age and working time per week. The sequential Šidák test was used to compare estimated marginal means. Multiple regression analysis with the total population, adjusted for age and shift, and the populations of each work shift, adjusted for age and working time per week, was used to determine if the variables of oxidative stress and antioxidant defense were associated with SJL. The statistical analysis of the data was done using the IBM SPSS software version 20.0. Statistical tests with values of p < 0.05 were accepted as significant.

Acknowledgements

To the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for the doctoral scholarship granted to K. R. C. Teixeira. To the Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento (CNPq) for the productivity grant awarded to N.P.S. To the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) for the funding granted for the development of this work. To the volunteers who participated in the study. To the Universidade Federal de Uberlândia (UFU), especially to the Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde (PPGCS), which made possible the accomplishment of this research.

Author Contributions

K.R.C.T. researched the data and wrote the manuscript. C.P.d.S. researched the data. L.A.d.M. researched the data and reviewed/edited the manuscript. J.A.M. researched the data. T.M.C. researched the data. K.D.A. researched the data and reviewed/edited the manuscript. N.P.S. contributed to the analytical plan, discussion, reviewed and edited the manuscript. E.P.d.O. contributed to the analytical plan, discussion, reviewed and edited the manuscript. C.A.C. contributed to the analytical plan, discussion, reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stevens RG, et al. Considerations of circadian impact for defining ‘shift work’ in cancer studies: IARC Working Group Report. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68:154–162. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.053512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brasil. (ed Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE) 66 (Rio de Janeiro, 2016).

- 3.Waterhouse J, Buckley P, Edwards B, Reilly T. Measurement of, and some reasons for, differences in eating habits between night and day workers. Chronobiol Int. 2003;20:1075–1092. doi: 10.1081/CBI-120025536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garaulet M, Ordovas JM, Madrid JA. The chronobiology, etiology and pathophysiology of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:1667–1683. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vetter C, Fischer D, Matera JL, Roenneberg T. Aligning work and circadian time in shift workers improves sleep and reduces circadian disruption. Curr Biol. 2015;25:907–911. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dochi M, et al. Shift work is a risk factor for increased total cholesterol level: a 14-year prospective cohort study in 6886 male workers. Occup Environ Med. 2009;66:592–597. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.042176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Padilha HG, et al. Metabolic responses on the early shift. Chronobiol Int. 2010;27:1080–1092. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2010.489883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pietroiusti A, et al. Incidence of metabolic syndrome among night-shift healthcare workers. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67:54–57. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.046797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esquirol Y, et al. Shift work and metabolic syndrome: respective impacts of job strain, physical activity, and dietary rhythms. Chronobiol Int. 2009;26:544–559. doi: 10.1080/07420520902821176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong PM, Hasler BP, Kamarck TW, Muldoon MF, Manuck SB. Social Jetlag, Chronotype, and Cardiometabolic Risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:4612–4620. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mancio, J., Leal, C., Ferreira, M., Norton, P. & Lunet, N. Does the association of prostate cancer with night-shift work differ according to rotating vs. fixed schedule? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate cancer and prostatic diseases, 10.1038/s41391-018-0040-2 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Wittmann M, Dinich J, Merrow M, Roenneberg T. Social jetlag: misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23:497–509. doi: 10.1080/07420520500545979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koopman ADM, et al. The Association between Social Jetlag, the Metabolic Syndrome, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the General Population: The New Hoorn Study. J Biol Rhythms. 2017;32:359–368. doi: 10.1177/0748730417713572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parsons MJ, et al. Social jetlag, obesity and metabolic disorder: investigation in a cohort study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015;39:842–848. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alves MS, et al. Social Jetlag Among Night Workers is Negatively Associated with the Frequency of Moderate or Vigorous Physical Activity and with Energy Expenditure Related to Physical Activity. J Biol Rhythms. 2017;32:83–93. doi: 10.1177/0748730416682110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kondratov RV, Gorbacheva VY, Antoch MP. The role of mammalian circadian proteins in normal physiology and genotoxic stress responses. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2007;78:173–216. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)78005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gan Y, et al. Shift work and diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Occup Environ Med. 2015;72:72–78. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2014-102150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buyukhatipoglu H, et al. Oxidative stress increased in healthcare workers working 24-hour on-call shifts. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2010;340:462–467. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181ef3c09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faraut B, Bayon V, Leger D. Neuroendocrine, immune and oxidative stress in shift workers. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casado A, et al. Relationship between oxidative and occupational stress and aging in nurses of an intensive care unit. Age (Dordr) 2008;30:229–236. doi: 10.1007/s11357-008-9052-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barreiros ALBS, David JM, David JP. Estresse oxidativo: relação entre geração de espécies reativas e defesa do organismo. Nova Química. 2006;29:113–123. doi: 10.1590/S0100-40422006000100021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mates JM. Effects of antioxidant enzymes in the molecular control of reactive oxygen species toxicology. Toxicology. 2000;153:83–104. doi: 10.1016/S0300-483X(00)00306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halliwell B, Whiteman M. Measuring reactive species and oxidative damage in vivo and in cell culture: how should you do it and what do the results mean? Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:231–255. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barbosa, K. B. F. et al. Oxidative stress: concept, implications and modulating factors. Revista de Nutrição23, 10.1590/S1415-52732010000400013 (2010).

- 25.Green K, Brand MD, Murphy MP. Prevention of mitochondrial oxidative damage as a therapeutic strategy in diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 1):S110–118. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.S110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inoue A, et al. Three job stress models/concepts and oxidative DNA damage in a sample of workers in Japan. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Syslova K, et al. Multimarker screening of oxidative stress in aging. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity. 2014;2014:562860. doi: 10.1155/2014/562860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ulas T, et al. The effect of day and night shifts on oxidative stress and anxiety symptoms of the nurses. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16:594–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santos Bernardes S, et al. Correlation of TGF-beta1 and oxidative stress in the blood of patients with melanoma: a clue to understanding melanoma progression? Tumour Biol. 2016;37:10753–10761. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-4967-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo Y, et al. The effects of shift work on sleeping quality, hypertension and diabetes in retired workers. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brum MC, Filho FF, Schnorr CC, Bottega GB, Rodrigues TC. Shift work and its association with metabolic disorders. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2015;7:45. doi: 10.1186/s13098-015-0041-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roenneberg T, Allebrandt KV, Merrow M, Vetter C. Social jetlag and obesity. Curr Biol. 2012;22:939–943. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharifian A, Farahani S, Pasalar P, Gharavi M, Aminian O. Shift work as an oxidative stressor. J Circadian Rhythms. 2005;3:15. doi: 10.1186/1740-3391-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gopalakrishnan A, Ji LL, Cirelli C. Sleep deprivation and cellular responses to oxidative stress. Sleep. 2004;27:27–35. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villafuerte G, et al. Sleep deprivation and oxidative stress in animal models: a systematic review. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity. 2015;2015:234952. doi: 10.1155/2015/234952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pena JL, Perez-Perera L, Bouvier M, Velluti RA. Sleep and wakefulness modulation of the neuronal firing in the auditory cortex of the guinea pig. Brain research. 1999;816:463–470. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)01194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green CB, Takahashi JS, Bass J. The meter of metabolism. Cell. 2008;134:728–742. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trivedi MS, Holger D, Bui AT, Craddock TJA, Tartar JL. Short-term sleep deprivation leads to decreased systemic redox metabolites and altered epigenetic status. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramanathan L, Gulyani S, Nienhuis R, Siegel JM. Sleep deprivation decreases superoxide dismutase activity in rat hippocampus and brainstem. Neuroreport. 2002;13:1387–1390. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200208070-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tai SY, et al. Effects of marital status and shift work on family function among registered nurses. Industrial health. 2014;52:296–303. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.2014-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishihara I, et al. Effect of work conditions and work environments on the formation of 8-OH-dG in nurses and non-nurse female workers. J UOEH. 2008;30:293–308. doi: 10.7888/juoeh.30.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilking M, Ndiaye M, Mukhtar H, Ahmad N. Circadian rhythm connections to oxidative stress: implications for human health. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:192–208. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhatti P, et al. Oxidative DNA damage during night shift work. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74:680–683. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2017-104414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nduhirabandi F, du Toit EF, Lochner A. Melatonin and the metabolic syndrome: a tool for effective therapy in obesity-associated abnormalities? Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2012;205:209–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2012.02410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagata C, et al. Sleep duration, nightshift work, and the timing of meals and urinary levels of 8-isoprostane and 6-sulfatoxymelatonin in Japanese women. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34:1187–1196. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2017.1355313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Folkard S. Do permanent night workers show circadian adjustment? A review based on the endogenous melatonin rhythm. Chronobiol Int. 2008;25:215–224. doi: 10.1080/07420520802106835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Claustrat B, Brun J, Chazot G. The basic physiology and pathophysiology of melatonin. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baydas G, Ercel E, Canatan H, Donder E, Akyol A. Effect of melatonin on oxidative status of rat brain, liver and kidney tissues under constant light exposure. Cell Biochem Funct. 2001;19:37–41. doi: 10.1002/cbf.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poeggeler B, et al. Melatonin’s unique radical scavenging properties - roles of its functional substituents as revealed by a comparison with its structural analogs. J Pineal Res. 2002;33:20–30. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079X.2002.01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodriguez C, et al. Regulation of antioxidant enzymes: a significant role for melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2004;36:1–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-079X.2003.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rains JL, Jain SK. Oxidative stress, insulin signaling, and diabetes. Free radical biology & medicine. 2011;50:567–575. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rahal A, et al. Oxidative stress, prooxidants, and antioxidants: the interplay. BioMed research international. 2014;2014:761264. doi: 10.1155/2014/761264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hardeland R, Coto-Montes A, Poeggeler B. Circadian rhythms, oxidative stress, and antioxidative defense mechanisms. Chronobiol Int. 2003;20:921–962. doi: 10.1081/CBI-120025245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sundar, I. K., Sellix, M. T. & Rahman, I. Redox regulation of circadian molecular clock in chronic airway diseases. Free radical biology & medicine, 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.10.383 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Krishnan N, Davis AJ, Giebultowicz JM. Circadian regulation of response to oxidative stress in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;374:299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fanjul-Moles ML, Prieto-Sagredo J, Lopez DS, Bartolo-Orozco R, Cruz-Rosas H. Crayfish Procambarus clarkii retina and nervous system exhibit antioxidant circadian rhythms coupled with metabolic and luminous daily cycles. Photochem Photobiol. 2009;85:78–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pisoschi AM, Pop A. The role of antioxidants in the chemistry of oxidative stress: A review. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;97:55–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Angelis KL, et al. Oxidative stress in the latissimus dorsi muscle of diabetic rats. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research=Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologicas. 2000;33:1363–1368. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2000001100016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gromadzinska J, et al. Relationship between intensity of night shift work and antioxidant status in blood of nurses. International archives of occupational and environmental health. 2013;86:923–930. doi: 10.1007/s00420-012-0828-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Juda M, Vetter C, Roenneberg T. Chronotype modulates sleep duration, sleep quality, and social jet lag in shift-workers. J Biol Rhythms. 2013;28:141–151. doi: 10.1177/0748730412475042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Petru R, Wittmann M, Nowak D, Birkholz B, Angerer P. Effects of working permanent night shifts and two shifts on cognitive and psychomotor performance. International archives of occupational and environmental health. 2005;78:109–116. doi: 10.1007/s00420-004-0585-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singh R, et al. Chronomics of circulating plasma lipid peroxides and anti-oxidant enzymes and other related molecules in cirrhosis of liver. In the memory of late Shri Chetan Singh. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy=Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2005;59(Suppl 1):S229–235. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(05)80037-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.WHO. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser894, i–xii, 1–253 (2000). [PubMed]

- 64.WHO. (ed WHO. World Health Organization) (Geneva, 2008).

- 65.Mota MC, Silva CM, Balieiro LCT, Fahmy WM, Crispim CA. Social jetlag and metabolic control in non-communicable chronic diseases: a study addressing different obesity statuses. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6358. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06723-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reutrakul S, et al. Chronotype is independently associated with glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2523–2529. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roenneberg T, et al. Epidemiology of the human circadian clock. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Juda M, Vetter C, Roenneberg T. The Munich ChronoType Questionnaire for Shift-Workers (MCTQShift) J Biol Rhythms. 2013;28:130–140. doi: 10.1177/0748730412475041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kendzerska TB, Smith PM, Brignardello-Petersen R, Leung RS, Tomlinson GA. Evaluation of the measurement properties of the Epworth sleepiness scale: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bertolazi, A. N. Tradução, adaptação cultural e validação de dois instrumentos de avaliação Do sono: Escala de Sonolência de Epworth e Índice de Qualidade de sono de Pittsburgh. Dissertação thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (2008).

- 72.Llesuy SF, Milei J, Molina H, Boveris A, Milei S. Comparison of lipid peroxidation and myocardial damage induced by adriamycin and 4’-epiadriamycin in mice. Tumori. 1985;71:241–249. doi: 10.1177/030089168507100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Buege JA, Aust SD. Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:302–310. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(78)52032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reznick AZ, Packer L. Oxidative damage to proteins: spectrophotometric method for carbonyl assay. Methods Enzymol. 1994;233:357–363. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(94)33041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutases. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1986;58:61–97. doi: 10.1002/9780470123041.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Flohe L, Gunzler WA. Assays of glutathione peroxidase. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:114–121. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(84)05015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Benzie IF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239:70–76. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pick E, Keisari Y. A simple colorimetric method for the measurement of hydrogen peroxide produced by cells in culture. J Immunol Methods. 1980;38:161–170. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(80)90340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Granger JP, et al. Role of nitric oxide in modulating renal function and arterial pressure during chronic aldosterone excess. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R197–202. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.1.R197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]