Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The Pharmacy Quality Alliance (PQA) recently developed 3 quality measures for prescribing opioids: high dosages, multiple providers and pharmacies, and concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines.

OBJECTIVE:

To examine the prevalence of the PQA measures and identify the patient demographic and health characteristics associated with the measures.

METHODS:

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis using Pennsylvania Medicaid data (2013-2015). We limited our analyses to noncancer patients who were aged 18-64 years and not dual-eligible for Medicare/Medicaid. Per PQA specifications, patients were required to possess ≥ 2 opioid prescriptions for ≥ 15 days annual supply each year. Outcome measures included (a) high dosages, defined as > 120 morphine milligram equivalents for ≥ 90 consecutive days; (b) multiple providers/pharmacies, defined as receiving opioid prescriptions from ≥ 4 providers and ≥ 4 pharmacies; and (c) concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines, defined as ≥ 30 cumulative days of overlapping opioids and benzodiazepines among individuals having ≥ 2 opioid and ≥ 2 benzodiazepine fills. Patient characteristics assessed included demographics; other medication use; and physical, mental, and behavioral health comorbidities. We present descriptive and multivariable statistical analyses of the data to describe trends in quality measure prevalence and associations with enrollee health characteristics.

RESULTS:

Numbers of enrollees meeting inclusion criteria ranged from 73,082 in 2013 to 85,710 in 2015. From 2013 to 2015, high dosage prevalence increased from 5.1% to 5.5%; the use of multiple providers/pharmacies decreased from 7.1% to 5.0%; and concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines decreased from 29.1% to 28.4% (all P < 0.05). A substantial portion of patients with > 1 PQA measure from 2013 to 2015 was eligible for Medicaid because of disability (41.8%-81.9%). Enrollees with opioid use disorder were more likely to have high dosages (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.83-2.21). Enrollees with anxiety and mood disorders were more likely to have multiple providers/pharmacies (anxiety: AOR = 1.54, 95% CI = 1.43-1.65; mood: AOR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.06-1.25) and concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines (anxiety: AOR = 3.50, 95% CI = 3.38-3.63; mood: AOR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.36-1.48).

CONCLUSIONS:

Given high levels of eligibility based on disability and the prevalence of mood, anxiety, and opioid use disorders among those identified by the quality measures, providers may require additional support to care for this patient population.

What is already known about this subject

Continuous monitoring of opioid use with quality metrics is paramount for health care systems and payers.

Current measures of opioid use employed in the field have been used inconsistently.

The recently developed Pharmacy Quality Alliance (PQA) measures, 2 of which have been endorsed by the National Quality Forum in 2017, have the potential to better standardize the measurement of opioid prescribing across health systems.

What this study adds

This study evaluated the prevalence of the PQA measures in a Medicaid-enrolled population using recent data.

This study described the prevalence of physical, mental, and behavioral health characteristics in a Medicaid population with high opioid dosages, use of multiple providers and pharmacies, and concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines.

To address high rates of problematic opioid consumption and overdose mortality,1 U.S. health systems are increasingly employing a variety of measures in administrative data to monitor patient risk from opioid medication exposure. The 3 most commonly used conceptual definitions of risk for opioid overdose relate to (1) high opioid dosage, measured in daily morphine equivalents2-9; (2) indicators of “shopping,” measured by patients visiting multiple providers or pharmacists for opioids10-13; and (3) concurrent use of opioid medications with drugs that can heighten negative effects of opioids (e.g., benzodiazepines).14-16

While there is broad consensus on the conceptual definition of these risk factors, they have been measured in a wide variety of ways. For instance, milligram morphine equivalents > 100 per day have been observed to heighten the risk of an overdose death.2-9 However, measures have included doses as low as 90 or as high as 200.7,17-19 In terms of shopping, definitions have included possessing narcotic prescriptions from 2 to 5 or more prescribers within 6 to 12 months of an overdose or filling opioids from 3 to 4 or more pharmacies in a period of 3, 6, or 18 months.10-12 Overlapping medications have been measured to include 2 or more pharmacy claims of opioids,13 overlapping long- and short-acting opioids,2,4 and overlapping opioids and sedatives (e.g., benzodiazepines).20

The Pharmacy Quality Alliance (PQA) is a national multistakeholder, consensus-based organization that has developed and disseminated a series of measures for monitoring medication utilization for many acute and chronic conditions with a focus on safety, adherence, and appropriateness.21 The PQA has recently established 3 measures of the quality of opioid prescribing that correspond closely to the commonly used concepts of risk previously outlined: (1) high opioid dosages, (2) multiple providers and multiple pharmacies,22(3) high dosages/multiproviders, and (4) the concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines.23

PQA measures have been adopted for use by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and numerous private organizations whose work focuses on system-level medication monitoring and treatment.24,25 For instance, the National Quality Forum has endorsed “high opioid dosages” and “multiple providers and multiple pharmacies” as performance measures to address opioid misuse and abuse.26 Nevertheless, while the PQA measures may bring more uniformity, some health professionals have raised concerns about the implementation of measures with similar characteristics. Specifically, some are concerned about unintended consequences for pain treatment arising from the use of these measures as thresholds for prescription and medication access restrictions.27 Further, given that empirical studies of the PQA measures have not been published, limited information is available about the physical, mental, and behavioral health of the patient population identified by the PQA measures and what supports may be required for providers treating those patients.

The purpose of this project was to apply the PQA opioid quality measures using administrative claims and encounter data from the Pennsylvania (PA) Medicaid program from 2013 to 2015 in order to describe their prevalence, how prevalence overall and among subgroups has changed over time, and associations with demographic and health characteristics of patients who met criteria for these measures. Examination of these measures within Medicaid data is particularly important given serious concerns for opioid medication misuse and overdose events within this population and may allow policymakers and payers to better plan resource allocation.28-30

Methods

Data Source and Sample

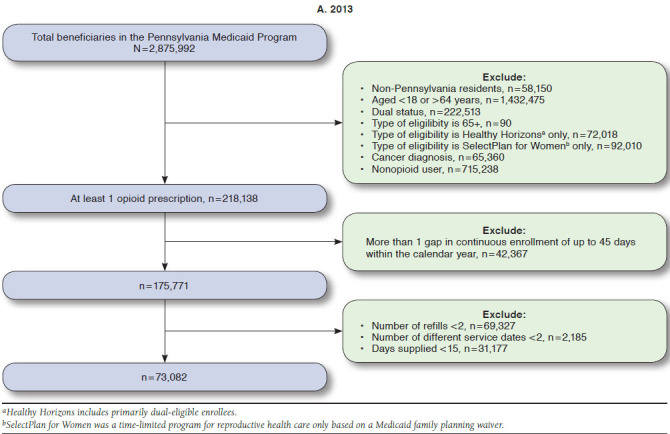

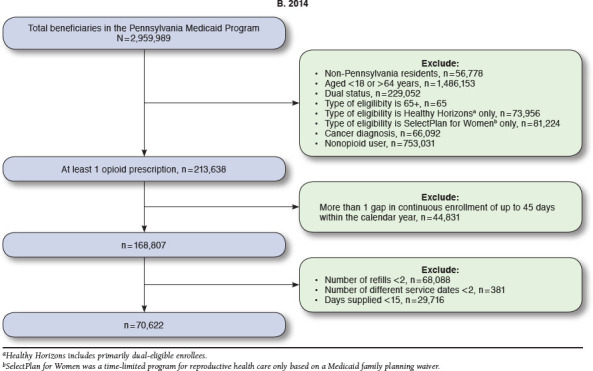

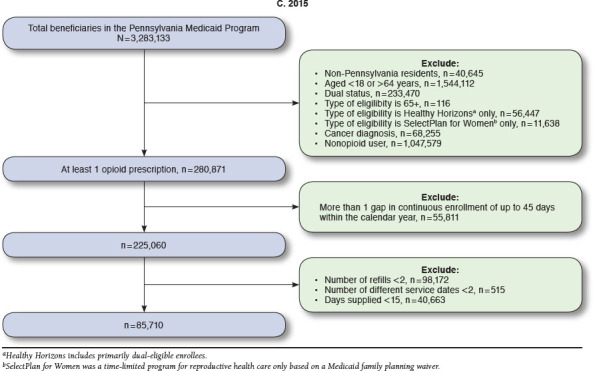

To examine the prevalence of PQA measures, we conducted 3 cross-sectional analyses each year from 2013 to 2015. We used pharmacy claims from PA Medicaid, along with enrollment files, professional claims, and medical claims to create the cohort (Appendix A, available in online article) and measure characteristics of the population. The PA Medicaid program is among the largest in terms of expenditures and enrollment in the United States, with about 2.9 million enrollees annually. In addition, PA’s health care utilization, access, and statewide demographic profile are similar to those seen across the nation (with the exception of fewer Hispanic enrollees).31,32 PA also has opioid prescribing rates that are consistently above national averages,1,33 and Medicaid enrollees have generally been observed to have opioid-related health problems and poor outcomes.30,34-36 Therefore, PA Medicaid program data are an appropriate and valuable source for examining the PQA opioid measures. We obtained data directly from the PA Department of Human Services for all fee-for-service and managed care enrollees. This project was designated as exempt by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Patients eligible for inclusion were identified following PQA specifications that comprise a population more likely to be using opioids for chronic rather than for acute pain conditions. Patients were excluded if they were aged < 18 and > 64 years, dual-eligible for Medicaid and Medicare (given we could not observe the prescription claims for these patients), and had any cancer diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes 140.0-239.9). Eligible patients were also required to have continuous Medicaid enrollment with no more than 1 gap of up to 45 days within a calendar year. The observation period for the measures was across 1 calendar year. Patients must have also had ≥ 2 documented prescription opioid medication fills on ≥ 2 separate days wherein the days supplied was ≥ 15 days. The opioid medications included buprenorphine, codeine, dihydro-codeine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, levorphanol, meperidine, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, oxymorphone, pentazocine, tapentadol, and tramadol.24,25 Patients filling only injectable opioids, oral opioid cough products, and buprenorphine/naloxone products were not included.

PQA Opioid Measures

We examined 3 binary PQA opioid quality measures:

The measure for high opioid dosages is defined as a daily dosage > 120 milligram morphine equivalents (MMEs) for ≥ 90 consecutive days. We calculated daily MME based on the strength per unit, quantities dispensed, days supplied, and MME conversion factor of each opioid prescription (i.e., strength per unit × [quantities dispensed/days supplied] × MME conversion factor).

The measure for multiple providers and multiple pharmacies is defined as individuals who received opioid prescriptions from ≥ 4 prescribers and who have filled their opioid medications at ≥ 4 pharmacies.

The measure for concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines (referred to as “opioids + benzodiazepine combination”) is defined as a ≥ 30-day overlapping supply of opioids and benzodiazepines among individuals having ≥ 2 opioids and ≥ 2 benzodiazepine fills.25

We did not include the measure for high dosages/multiprovider in our analyses.24 This measure was not included given its small prevalence (< 1% of the cohort), resulting in prohibitively small cell sizes when comparing characteristics of enrollees meeting criteria for this measure.

Patient Descriptive Characteristics

Demographic and eligibility characteristics from the Medicaid enrollment file were included in the analyses to describe the patient population. We included participant age (18-29, 30-39, 40-49, and 50-64 years); sex; race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, and other); urban/rural living location (Rural-Urban Continuum Codes37,38); eligibility category (disabled, newly eligible through Medicaid expansion [implemented in PA in 2015], and other nondisabled adults); and dominant plan type (fee for service and managed care).

In addition to demographics, we constructed several measures of comorbid health conditions. Using ICD-9-CM codes, we included any diagnoses of anxiety or mood disorders.39 Using ICD-9/10-CM codes,40 we also included the following individual indicators of underlying addiction separately in the descriptive and multivariate analyses: diagnoses for opioid use disorder, fatal and nonfatal heroin/opioid overdose (see Appendix B for ICD-9/10-CM codes, available in online article), use of medication-assisted treatment (methadone maintenance [Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes H0020/J1230], buprenorphine use [identified by National Drug Code numbers as forms approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for opioid use disorder], and naltrexone [identified by National Drug Code numbers]). We likewise reported numbers of opioid medications filled (i.e., list of described opioids) for those with the 3 measures and numbers of benzodiazepine prescriptions filled for those with the opioids + benzodiazepine combination in the calendar year. We also included a modified Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (with mood and opioid use disorder removed from the index) based on ICD-9/10-CM codes, depending on the month and year.41

Statistical Analyses

We examined the prevalence of the 3 PQA measures each year and described patient characteristics using frequencies and percentages for patients with and without PQA measures. We employed 3 generalized estimating equation models to determine the difference in prevalence for each PQA measure for 2013 compared with 2015 (2015 as the dependent variable and 2013 as the comparison group). These models were adjusted for age, sex, race, and rural/urban living area. Chi-square difference and t-tests were used to assess bivariate differences for mental and behavioral health of the enrollees, as well as for opioid and benzodiazepine filling patterns using data for the most recent year (2015). Finally, we developed 3 multivariable logistic regression models to examine the cross-sectional associations between the health comorbidities and medication use previously described and each of the 3 PQA measures. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Demographics

Table 1 displays the unadjusted overall prevalence and cohort demographics by quality measure. Approximately 5% of the cohort was identified as having high dosages of opioid medications (5.1% [n = 3,753] in 2013 and 5.5% [n = 4,708] in 2015). The prevalence of patients with multiple providers decreased over time, from 7.1% in 2013 (n = 5,215) to 5% in 2015 (n = 4,311). The prevalence of the opioids + benzodiazepine combination use was 29.1% (n = 21,244) in 2013 and 28.4% (n = 24,346) in 2015. All of these changes were statistically significant when we compared 2015 to 2013 in the multivariate model, controlling for age, sex, race, and living area (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Population Characteristics by Pharmacy Quality Alliance Opioid Quality Measures, 2013-2015

| High Dosage | Multiple Providers | Opioids + Benzodiazepine | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| Total patients | 73,082 | 70,622 | 85,710 | 73,082 | 70,622 | 85,710 | 73,082 | 70,622 | 85,710 |

| Overall cohort prevalence | 3,753 (5.1) | 3,823 (5.4) | 4,708 (5.5) | 5,215 (7.1) | 3,692 (5.2) | 4,311 (5.0) | 21,244 (29.1) | 21,153 (30.0) | 24,346 (28.4) |

| Age group | |||||||||

| 18-29 | 230 (6.1) | 225 (5.9) | 259 (5.5) | 1,099 (21.1) | 761 (20.6) | 774 (18.0) | 1,716 (8.1) | 1,524 (7.2) | 1,590 (6.5) |

| 30-39 | 717 (19.1) | 715 (18.7) | 923 (19.6) | 1,534 (29.4) | 1,144 (31.0) | 1,383 (32.1) | 4,265 (20.1) | 4,285 (20.3) | 4,997 (20.5) |

| 40-49 | 1,144 (30.5) | 1,151 (30.1) | 1,402 (29.8) | 1,379 (26.4) | 920 (24.9) | 1,116 (25.9) | 6,234 (29.3) | 6,016 (28.4) | 6,908 (28.4) |

| 50-64 | 1,662 (44.3) | 1,732 (45.3) | 2,124 (45.1) | 1,203 (23.1) | 867 (23.5) | 1,038 (24.1) | 9,029 (42.5) | 9,328 (44.1) | 10,851 (44.6) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 2,059 (54.9) | 2,065 (54.0) | 2,477 (52.6) | 3,521 (67.5) | 2,539 (68.8) | 2,838 (65.8) | 14,785 (69.6) | 14,738 (69.7) | 16,840 (69.2) |

| Male | 1,694 (45.1) | 1,758 (46.0) | 2,231 (47.4) | 1,694 (32.5) | 1,153 (31.2) | 1,473 (34.2) | 6,459 (30.4) | 6,415 (30.3) | 7,506 (30.8) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 2,938 (78.3) | 2,875 (75.2) | 3,442 (73.1) | 3,032 (58.1) | 2,222 (60.2) | 2,631 (61.0) | 14,770 (69.5) | 14,484 (68.5) | 16,897 (69.4) |

| Black | 628 (16.7) | 754 (19.7) | 1,019 (21.6) | 1,737 (33.3) | 1,152 (31.2) | 1,323 (30.7) | 3,961 (18.6) | 4,122 (19.5) | 4,607 (18.9) |

| Hispanic | 110 (2.9) | 132 (3.5) | 155 (3.3) | 347 (6.7) | 248 (6.7) | 278 (6.4) | 2,160 (10.2) | 2,177 (10.3) | 2,377 (9.8) |

| Other | 77 (2.1) | 62 (1.6) | 92 (2.0) | 99 (1.9) | 70 (1.9) | 79 (1.8) | 353 (1.7) | 370 (1.7) | 465 (1.9) |

| Living area | |||||||||

| Urban | 3,085 (82.2) | 3,170 (82.9) | 3,894 (82.7) | 4,646 (89.1) | 3,225 (87.4) | 3,775 (87.6) | 17,690 (83.3) | 17,656 (83.5) | 20,283 (83.3) |

| Rural | 668 (17.8) | 653 (17.1) | 814 (17.3) | 569 (10.9) | 467 (12.6) | 536 (12.4) | 3,554 (16.7) | 3,497 (16.5) | 4,063 (16.7) |

| Type of eligibility | |||||||||

| Disabled | 3,052 (81.3) | 3,130 (81.9) | 2,907 (61.7) | 3,317 (63.6) | 2,349 (63.6) | 1,804 (41.8) | 16,617 (78.2) | 16,708 (79.0) | 14,246 (58.5) |

| Newly eligible | NA | NA | 1,101 (23.4) | NA | NA | 1,479 (34.3) | NA | NA | 6,205 (25.5) |

| Nondisabled adults | 701 (18.7) | 693 (18.1) | 700 (14.9) | 1,898 (36.4) | 1,342 (36.3) | 1,028 (23.8) | 4,627 (21.8) | 4,438 (21.0) | 3,895 (16.0) |

| Managed care | 3,648 (97.2) | 3,787 (99.1) | 4,676 (99.3) | 5,126 (98.3) | 3,633 (98.4) | 4,252 (98.6) | 20,655 (97.2) | 20,546 (97.1) | 23,878 (98.1) |

Note: Fee-for-service data are not shown due to small sample size.

NA = not applicable given that Medicaid expansion took place in 2015 in Pennsylvania.

TABLE 2.

| 2013 Unadjusted Prevalence, n (%) | 2015 Unadjusted Prevalence, n (%) | Estimated Adjusted Difference,c % | 95% CId | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High dosage | 3,753 (5.1) | 4,708 (5.5) | 0.2 | 0.03, 0.4 | 0.020 |

| Multiple providers | 5,215 (7.1) | 4,311 (5.0) | -1.4 | -1.7, -1.2 | < 0.001 |

| Opioids + benzodiazepine | 21,244 (29.1) | 24,346 (28.4) | -0.5 | -0.8, -0.1 | 0.010 |

aReference group = 2013; n = 73,082.

bFor 2015, n = 85,710; 30,103 patients were in both the 2013 and 2015 cohorts.

c2015 was the year of Medicaid expansion, which resulted in an increase in enrollment.

dGeneralized estimating equation models were adjusted for age, sex, race, and living area.

CI = confidence interval.

Enrollee characteristics with each of the PQA measures were largely stable over the 3-year period. In 2015, a majority were female (range: 52.6% [high dosages] to 69.2% [opioids + benzodiazepine]); white (range: 61.0% [multiple providers] to 73.1% [high dosages]); and resided in urban areas (range: 82.7% [high dosages] to 87.6 [multiple providers]). A large share of enrollees was eligible due to disability (range: 41.8 [multiple providers] to 61.7 [high dosages]).

Health Comorbidities

We also examined cross-sectional differences for mental and behavioral health status of patients with and without the quality measures in the 2015 cohort (Table 3). The prevalence of anxiety disorders was significantly higher among those with multiple providers relative to their counterparts (53.3% vs. 34.4%, P < 0.001). Anxiety disorders were also more than twice as prevalent among those with the opioids + benzodiazepine combination as those without (58.6% vs. 25.6%, P < 0.001). Similarly, the prevalence of mood disorders was significantly higher among those with multiple providers and the opioids + benzodiazepine combination relative to those without the measures (59.8% vs. 44.2%, P < 0.001, and 60.7% vs. 37.8%, P < 0.001, respectively). Larger portions of enrollees with each quality measure compared with their counterparts also had opioid use disorder (high dosage: 21.8% vs. 11.7%; multiple providers: 24.4% vs. 11.6%; opioids + benzodiazepine: 15.6% vs. 10.9%; P < 0.001 for each measure) and heroin/opioid overdose (high dosage: 2.0% vs. 1.1%; multiple providers: 2.7% vs. 1.1%; opioids + benzodiazepine: 1.8% vs. 0.9%; P < 0.001 for each measure).

TABLE 3.

Bivariate Description of Behavioral Health Indicators and Opioid Fills Among Enrollees with the Pharmacy Quality Alliance Measures, 2015

| Characteristics | High Dosage | Multiple Providers | Opioids + Benzodiazepine | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | P Value | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | P Value | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | P Value | |

| Total enrollees | 4,708 | 81,002 | 4,311 | 76,319 | 24,346 | 61,364 | |||

| Anxiety disorder | 1,692 (35.9) | 28,270 (34.9) | 0.150 | 2,298 (53.3) | 26,256 (34.4) | < 0.001 | 14,266 (58.6) | 15,696 (25.6) | < 0.001 |

| Mood disorder | 1,919 (40.8) | 36,077 (44.5) | < 0.001 | 2,580 (59.8) | 33,714 (44.2) | < 0.001 | 14,785 (60.7) | 23,211 (37.8) | < 0.001 |

| Opioid use disorder | 1,028 (21.8) | 9,442 (11.7) | < 0.001 | 1,053 (24.4) | 8,816 (11.6) | < 0.001 | 3,789 (15.6) | 6,681 (10.9) | < 0.001 |

| Heroin/opioid overdose | 96 (2.0) | 862 (1.1) | < 0.001 | 115 (2.7) | 806 (1.1) | < 0.001 | 431 (1.8) | 527 (0.9) | < 0.001 |

| Medication-assisted treatment | 140 (3.0) | 3,141 (3.9) | 0.002 | 250 (5.8) | 2,822 (3.7) | < 0.001 | 1,064 (4.4) | 2,217 (3.6) | < 0.001 |

| Antidepressant drug use | 2,558 (54.3) | 44,007 (54.3) | 0.990 | 2,752 (63.8) | 41,484 (54.4) | < 0.001 | 17,263 (70.9) | 29,302 (47.8) | < 0.001 |

| Opioid fills, mean (SD) | 22.0 (9.6) | 9.0 (6.4) | < 0.001 | 16.0 (8.2) | 9.4 (7.0) | < 0.001 | 13.2 (7.8) | 8.3 (6.5) | < 0.001 |

| Benzodiazepine fills, mean (SD) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10.6 (5.0) | 0.9 (2.6) | < 0.001 |

| Elixhauser Index, mean (SD) | 3.6 (2.8) | 3.5 (2.7) | 0.040 | 4.7 (3.2) | 3.5 (2.7) | < 0.001 | 4.2 (2.8) | 3.3 (2.7) | < 0.001 |

SD = standard deviation.

Medication Filling Patterns

We also examined medication use among patients with and without the PQA measures in 2015 (Table 3). Compared with those without the quality measures, more patients with multiple providers and the opioids + benzodiazepine combination were identified as receiving medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder (multiple prescribers: 5.8% vs. 3.7%; opioids + benzodiazepine: 4.4% vs. 3.6%; P < 0.001 for each) and taking antidepressants (multiple prescribers: 63.8% vs. 54.4%; opioids + benzodiazepine: 70.9% vs. 47.8%; P < 0.001 for each). Patients with each of the measures also had a higher number of fills for opioid medications (range in differences of mean number of fills: 4.9-13.0, P < 0.001) compared with those who did not have the quality measures.

Associations with Opioid Risks

Results from multivariable models of cross-sectional associations between the quality measures and demographic and health comorbidities in 2015 are displayed in Table 4. In terms of increased likelihood for the measures, enrollees with opioid use disorder were more likely to have high dosages (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.83-2.21), as were enrollees with heroin/opioid overdose (AOR = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.10-1.85) and those with a higher number of opioid fills (AOR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.18-1.19). Enrollees with anxiety disorder were more likely to fill opioid prescriptions from multiple providers (AOR = 1.54, 95% CI = 1.43-1.65), as were enrollees with opioid use disorder (AOR = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.31-1.57) and those residing in an urban area (AOR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.25-1.52). Use of the opioids + benzodiazepine combination was associated with diagnosis of anxiety disorder (AOR = 3.50, 95% CI = 3.38-3.63), use of antidepressants (AOR = 1.53, 95% CI = 1.47-1.59), and mood disorder (AOR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.36-1.48).

TABLE 4.

Adjusted Logistic Regression Estimates for Pharmacy Quality Alliance Measures, 2015

| Predictor | High Dosage (n = 85,710) | P Value | Multiple Providers (n = 80,630) | P Value | Opioids + Benzodiazepine (n = 85,710) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |||||

| Age, years | 1.01 (1.01-1.02) | < 0.001 | 0.96 (0.95-0.96) | < 0.001 | 1.03 (1.03-1.03) | < 0.001 | |

| Female | 0.63 (0.59-0.67) | < 0.001 | 0.95 (0.89-1.02) | 0.160 | 1.26 (1.22-1.31) | < 0.001 | |

| Race (reference = white) | |||||||

| Black | 0.84 (0.77-0.91) | < 0.001 | 1.53 (1.41-1.65) | < 0.001 | 0.70 (0.67-0.73) | < 0.001 | |

| Hispanic | 0.46 (0.38-0.55) | < 0.001 | 0.85 (0.75-0.98) | 0.020 | 1.22 (1.15-1.30) | < 0.001 | |

| Other | 0.87 (0.68-1.11) | 0.250 | 0.98 (0.77-1.25) | 0.890 | 0.84 (0.75-0.95) | 0.004 | |

| Urban | 1.08 (0.99-1.19) | 0.090 | 1.38 (1.25-1.52) | < 0.001 | 1.15 (1.10-1.21) | < 0.001 | |

| Eligibility (reference = nondisabled adults) | |||||||

| Disabled | 1.18 (1.06-1.32) | 0.003 | 0.66 (0.60-0.73) | < 0.001 | 1.28 (1.21-1.35) | < 0.001 | |

| Medicaid expansion | 0.91 (0.82-1.02) | 0.120 | 1.06 (0.97-1.16) | 0.210 | 0.94 (0.89-0.99) | 0.020 | |

| Heroin/opioid overdose | 1.43 (1.10-1.85) | 0.010 | 1.05 (0.84-1.31) | 0.660 | 1.25 (1.08-1.45) | 0.003 | |

| Opioid use disorder | 2.01 (1.83-2.21) | < 0.001 | 1.43 (1.31-1.57) | < 0.001 | 1.04 (0.98-1.10) | 0.180 | |

| Anxiety disorder | 0.99 (0.92-1.07) | 0.770 | 1.54 (1.43-1.65) | < 0.001 | 3.50 (3.38-3.63) | < 0.001 | |

| Mood disorder | 0.86 (0.79-0.93) | < 0.001 | 1.15 (1.06-1.25) | < 0.001 | 1.42 (1.36-1.48) | < 0.001 | |

| Medication-assisted treatment | 0.83 (0.68-1.02) | 0.080 | 1.09 (0.93-1.27) | 0.280 | 1.22 (1.11-1.34) | < 0.001 | |

| Antidepressant drug use | 0.94 (0.87-1.01) | 0.100 | 1.00 (0.93-1.08) | 0.990 | 1.53 (1.47-1.59) | < 0.001 | |

| Opioid fills | 1.18 (1.18-1.19) | < 0.001 | 1.10 (1.09-1.10) | < 0.001 | 1.09 (1.09-1.10) | < 0.001 | |

| Elixhauser Index | 0.91 (0.90-0.93) | < 0.001 | 1.15 (1.13-1.16) | < 0.001 | 0.97 (0.96-0.98) | < 0.001 | |

AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Hispanic and black enrollees were significantly less likely than white enrollees to have the PQA measures across all categories (P < 0.05), with the exception of slightly higher odds of having opioids + benzodiazepine combination among Hispanic enrollees (AOR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.15-1.30).

Enrollees newly eligible for Medicaid in 2015 were less likely to have the opioids + benzodiazepine combination (AOR = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.89-0.99). Enrollees with a greater number of comorbidities, measured by the Elixhauser Index, were less likely to have high dosages (AOR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.90-0.93) and opioids + benzodiazepine combination (AOR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.96-0.98) but more likely to have multiple providers (AOR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.13-1.16).

Discussion

This study applied 3 opioid quality measures recently developed by the PQA to PA Medicaid program data from 2013 to 2015. These measures are based on previous research that has linked patient and prescriber behavior with increased risk for problematic patient-level outcomes, including overdose. Limited research is available regarding the prevalence and the characteristics of patients who will be potentially identified by these metrics. Our analyses show findings in 3 key areas in terms of comorbid health conditions, trends showing improvement over time, and their consistency with previous research of patients with problematic opioid medication use.

First, study results showed there were high rates of mental and behavioral health conditions among those with the PQA measures. Approximately 60% of those with the opioids + benzodiazepine combination and multiple providers/pharmacies had a mood disorder. Among those with the opioids + benzodiazepine combination, nearly 16% had opioid use disorders compared with almost 11% among those not meeting criteria for concurrent use—both rates of opioid use disorder being higher than the general adult PA Medicaid population, which was 3.6% in 2007 and 4.5% in 2012.42 In the multivariable models, both mental and behavioral health disorders and overdose were also highly associated with the PQA measures.

These findings may signal a need for improved communication and coordination between prescribers providing pain and mental health medications. The high rates of combination prescribing and high opioid dosages should be carefully examined and monitored by health systems in order to ensure patients are not exposed to unnecessary risks.43 Given the number of concomitant health conditions among identified patients—these measures may be used by payers to better target needed supports to those who care for these patients. Moreover, because of the limitations of drug monitoring programs affecting patient health beyond lowering prescribing and filling behaviors,44-46 strategies to engage and direct patients to integrated care will be paramount given the apparent needs of these populations.47,48 Furthermore, these data also suggest the importance of risk adjustment when comparing these quality measures across populations. For instance, as payers compare prevalence of the PQA measures across plans, they will need to account for differences in prevalence of mental health conditions in order to not penalize plans that serve a disproportionate share of patients with these conditions.

Second, in terms of changes across study years, there were differences in the prevalence of enrollees accessing opioids from multiple providers/pharmacies and having the opioids + benzodiazepine combination from 2013 to 2015. The changes could appear to be relatively minor; however, they represent approximately 1,000-3,000 lives—a clinically significant amount of individuals overall. There was a divergent trend in the prevalence of high dosages, which increased a small degree during the observation period. Increasingly stringent laws, formulary management, and public awareness in the state could have helped promote these shifts.49 However, these findings are congruent with recent research that has shown that dispensing of opioids in most states and negative outcomes related to the opioid epidemic have also increased during comparable years.1,50

Third, results from these analyses are consistent with previous research among patients with problematic opioid medication use and help show the value of the PQA metrics to measure prescribing quality across U.S. health plans. The largest proportions of patients positive for these measures were white, lived in urban areas of the state, and were female. Previous research has observed that problematic opioid medication use, prescribing, and misuse as well as higher rates of overdose are more prevalent among white patients compared with other races/ethnicities.29,51-53 Urban residents likewise have been noted to have higher rates of prescription opioid misuse compared with rural residents.54 In addition, a substantial portion of patients was eligible for Medicaid because of disability, which has been noted as a characteristic of patients who experience overdose.55 Previous research has also documented mood, anxiety, and opioid use disorders are associated with misuse and overdose.29,30 Finally, we found that the newly eligible enrollees had a lower likelihood of having an opioids + benzodiazepine combination, and no significant relationship between enrollment in Medicaid due to the expansion and the other PQA measures. This finding adds to the literature on the role of Medicaid expansion in addressing the opioid crisis.56

Limitations

This study has some limitations to consider. Although utilization, access, and demographics of the PA Medicaid program are similar to other states,31,32 the results herein are nonetheless from a single state among a population that have differing needs from the general population, which limit their generalizability. In addition, while the PQA measures are based on evidence and show initial validity for monitoring problematic opioid consumption and behavior, their current construction should continue to be validated. We also recognize that our study cohorts and analytical approach are largely descriptive and causation cannot be inferred, nor can we fully control for unmeasured confounders. Our analyses were not able to take into account policies, social, and economic factors that may have influenced the results. However, the purpose of the project was not to assess causal inference. Rather, the purpose was to be descriptive in order to increase understanding around the prevalence and characteristics of enrollees positive for these recently developed PQA measures of prescribing quality. Future work should seek to employ the PQA measures within research designs, such as difference-in-differences analyses, which have greater ability to infer causal relationships.

Conclusions

As problematic opioid use and overdose continues to take a serious toll on state health care systems, payers and systems have the important burden of continually monitoring patient risk. The PQA has set forth 3 research-based quality measures that have the potential to be implemented in pharmacy claims data for health surveillance. Through concerted and coordinated surveillance, health systems and payers stand to make a major contribution to confronting the opioid epidemic through monitoring patient risk across systems.

APPENDIX A. Medicaid Sample Flowcharts for Pharmacy Quality Alliance Measures, 2013-2015

APPENDIX B. Codes for Opioid Use, Anxiety, and Mood Disorders and Heroin/Opioid Overdose

| Condition | ICD-9/10-CM Codes |

|---|---|

| Opioid use disorder | • ICD-9-CM: 3040, 30400, 30401, 30402, 30403, 3047, 30470, 30471, 30472, 30473, 3055, 30550, 30551, 30552, 30553 • ICD-10-CM: F1110, F11120, F11121, F11122, F11129, F1114, F11150, F11151, F11159, F11181, F11182, F11188, F1119, F1120, F1121, F11220, F11221, F11222, F11229, F1123, F1124, F11250, F11251, F11259, F11281, F11282, F11288, F1129, F1190, F11920, F11921, F11922, F11929, F1193, F1194, F11950, F11951, F11959, F11981, F11982, F11988, F1199 |

| Anxiety disorders | • ICD-9-CM: 29384, 30000, 30001, 30002, 30009, 30010, 30020, 30021, 30022, 30023, 30029, 3003, 3005, 30089, 3009, 3080, 3081, 3082, 3083, 3084, 3089, 30981, 3130, 3131, 31321, 31322, 3133, 31382, 31383 |

| Mood disorders | • ICD-9-CM: 29383, 29600, 29601, 29602, 29603, 29604, 29605, 29606, 29610, 29611, 29612, 29613, 29614, 29615, 29616, 29620, 29621, 29622, 29623, 29624, 29625, 29626, 29630, 29631, 29632, 29633, 29634, 29635, 29636, 29640, 29641, 29642, 29643, 29644, 29645, 29646, 29650, 29651, 29652, 29653, 29654, 29655, 29656, 29660, 29661, 29662, 29663, 29664, 29665, 29666, 2967, 29680, 29681, 29682, 29689, 29690, 29699, 3004, 311 |

| Heroin/opioid overdose | • ICD-9-CM: 96500, 96501, 96502, 96509, E8500, E8501, E8502 • ICD-10-CM: T400X1A, T400X3A, T400X4A, T401X, T401X1, T401X1A, T401X1D, T401X1S, T401X 3, T401X3A, T401X3D, T401X3S, T401X4, T401X4A, T401X4D, T401X4S, T402X1A, T402X1D, T402X1S, T402X3A, T402X3D, T402X3S, T402X4A, T402X4D, T402X4S, T402X5A, T402X5D, T402X5S, T403X1, T403X1A, T403X1D, T403X1S, T403X3A, T403X3D, T403X3S, T403X4A, T403X4D, T403X4S, T403X5A, T403X5D, T403X5S, T404X1, T404X1A, T404X1D, T404X1S, T404X3A, T404X3D, T404X3S, T404X4A, T404X4D, T404X4S, T404X5A, T404X5D, T404X5S, T40601A, T40603A, T40604A, T40691, T40691A, T40693A, T40694A |

ICD-9/10-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth/Tenth Revisions, Clinical Modification.

References

- 1.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50-51):1378-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Logan J, Liu Y, Paulozzi L, Zhang K, Jones C. Opioid prescribing in emergency departments: the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing and misuse. Med Care. 2013;51(8):646-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mack KA, Zhang K, Paulozzi L, Jones C. Prescription practices involving opioid analgesics among Americans with Medicaid, 2010. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(1):182-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y, Logan JE, Paulozzi LJ, Zhang K, Jones CM. Potential misuse and inappropriate prescription practices involving opioid analgesics. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(8):648-65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohnert ASB, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. . Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paulozzi LJ, Strickler GK, Kreiner PW, Koris CM. Controlled substance prescribing patterns—prescription behavior surveillance system, eight states, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2015;64(9):1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dasgupta N, Funk MJ, Proescholdbell S, Hirsch A, Ribisl KM, Marshall S. Cohort study of the impact of high-dose opioid analgesics on overdose mortality. Pain Med. 2016;17(1):85-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gwira Baumblatt JA, Wiedeman C, Dunn JR, Schaffner W, Paulozzi LJ, Jones TF. High-risk use by patients prescribed opioids for pain and its role in overdose deaths. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):796-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. . Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):85-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, et al. . Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA. 2008;300(22):2613-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peirce GL, Smith MJ, Abate MA, Halverson J. Doctor and pharmacy shopping for controlled substances. Med Care. 2012;50(6):494-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cepeda MS, Fife D, Chow W, Mastrogiovanni G, Henderson SC. Assessing opioid shopping behaviour: a large cohort study from a medication dispensing database in the U.S. Drug Saf. 2012;35(4):325-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Z, Wilsey B, Bohm M, et al. . Defining risk of prescription opioid overdose: pharmacy shopping and overlapping prescriptions among long-term opioid users in Medicaid. J Pain. 2015;16(5):445-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou R, Deyo R, Devine B, et al. . The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid treatment of chronic pain. Evidence report/technology assessment No. 218. (Prepared by the Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2012-00014-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 14-E005-EF. 2014. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK258809/. Accessed July 16, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brands B, Blake J, Marsh DC, Sproule B, Jeyapalan R, Li S. The impact of benzodiazepine use on methadone maintenance treatment outcomes. J Addict Dis. 2008;27(3):37-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuerbis A, Sacco P, Blazer DG, Moore AA. Substance abuse among olderadults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(3):629-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becker WC, Fenton BT, Brandt CA, et al. . Multiple sources of prescription payment and risky opioid therapy among veterans. Med Care. 2017; 55(7 Suppl 1):S33-S36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braden JB, Russo J, Fan MY, et al. . Emergency department visits among recipients of chronic opioid therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(16):1425-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. . Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernardy NC, Lund BC, Alexander B, Friedman MJ. Increased polysedative use in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Pain Med. 2014;15(7):1083-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pharmacy Quality Alliance. Pharmacy Quality Alliance performance measures . 2017. Available at: http://pqaalliance.org/measures/default.asp. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- 22.Pharmacy Quality Alliance. Use of opioids from multiple providers or at high dosage in persons without cancer . 2016. Available at: http://pqaalliance. org/measures/default.asp. Accessed June 25, 2018.

- 23.Pharmacy Quality Alliance. Concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines . Available at: http://pqaalliance.org/measures/default.asp. Accessed June 25, 2018.

- 24.Pharmacy Quality Alliance. Pharmacy Quality Alliance measures used by CMS in the star ratings . 2017. Available at: http://pqaalliance.org/measures/cms.asp. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- 25.Pharmacy Quality Alliance. Licensing Pharmacy Quality Alliance measures . 2017. Available at: http://pqaalliance.org/measures/licensing.asp. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- 26.Pharmacy Quality Alliance. PQA receives NQF endorsement of three performance measures to address opioid misuse/abuse. Press release . May 10, 2017. Available at: http://myemail.constantcontact.com/Press-Release---PQA-Receives-NQF-Endorsement-of-Three-Performance-Measures-to-Address-Opioid-Misuse-Abuse.html?soid=1108959632030&aid=tfl6y6ucO Go. Accessed June 25, 2018.

- 27.Kertesz SG. An opioid quality metric based on dose alone? 80 professionals respond to NCQA. Medium. March 22, 2017. Available at: https://medium.com/@StefanKertesz/an-opioid-quality-metric-based-on-dose-alone-80-professionals-respond-to-ncqa-6f9fbaa2338. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- 28.Sharp M, Melnick T. Poisoning deaths involving opioid analgesics—New York State, 2003-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(14):377-80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cochran G, Gordon AJ, Lo-Ciganic WH, et al. . An examination of claims-based predictors of overdose from a large Medicaid program. Med Care. 2016;55(3):291-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Fan M-Y, Devries A, Brennan Braden J, Martin BC. Risks for possible and probable opioid misuse among recipients of chronic opioid therapy in commercial and Medicaid insurance plans: the TROUP Study. Pain. 2010;150(2):332-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Center for Health Statistics . Health, United States 2012: With Special Feature on Emergency Care. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pating DR, Miller MM, Goplerud E, Martin J, Ziedonis DM. New systems of care for substance use disorders: treatment, finance, and technology under health care reform. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35(2):327-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention status report 2013: prescription drug overdose, Pennsylvania . 2014. Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/psr/2013/prescriptiondrug/2013/pa-pdo. pdf. Accessed June 25, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids among Medicaid enrollees—Washington, 2004-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(42):1171-75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Fan M-Y, Braden JB, Devries A, Sullivan MD. An analysis of heavy utilizers of opioids for chronic noncancer pain in the TROUP study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(2):279-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faul M, Bohm M, Alexander C. Methadone prescribing and overdose and the association with Medicaid preferred drug list policies—United States, 2007-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(12):320-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Department of Agriculture. Rural-urban continuum codes . 2013. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/documentation.aspx#.VC61zGddUrA. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- 38.Baldwin LM, Andrilla CH, Porter MP, Rosenblatt RA, Patel S, Doescher MP. Treatment of early-stage prostate cancer among rural and urban patients. Cancer. 2013;119(16):3067-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization . International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization . International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41.University of Manitoba. Concept: Elixhauser Comorbidity Index . 2016. Available at: http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/viewConcept. php?printer=Y&conceptID=1436. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- 42.Gordon AJ, Lo-Ciganic WH, Cochran G, et al. . Patterns and quality of buprenorphine opioid agonist treatment in a large Medicaid program. J Addict Med. 2015;9(6):470-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DuPont RL. “Should patients with substance use disorders be prescribed benzodiazepines?” No. J Addict Med. 2017;11(2):84-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bao Y, Pan Y, Taylor A, et al. . Prescription drug monitoring programs are associated with sustained reductions in opioid prescribing by physicians. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(6):1045-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paulozzi LJ, Kilbourne EM, Desai HA. Prescription drug monitoring programs and death rates from drug overdose. Pain Med. 2011;12(5):747-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ali MM, Dowd WN, Classen T, Mutter R, Novak SP. Prescription drug monitoring programs, nonmedical use of prescription drugs, and heroin use: evidence from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Addict Behav. 2017;69:65-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cochran G, Gordon AJ, Field C, et al. . Developing a framework of care for opioid medication misuse in community pharmacy. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016;12(2):293-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solution. Behavioral health homes for people with mental health and substance use conditions . May 2012. Available at: https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/CIHS_Health_Homes_Core_Clinical_Features.pdf. Accessed June 25, 2018.

- 49.Katz NP, Birnbaum H, Brennan MJ, et al. . Prescription opioid abuse: challenges and opportunities for payers. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(4):295-302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mack KA, Jones CM, McClure RJ. Physician dispensing of oxycodone and other commonly used opioids, 2000-2015, United States. Pain Med. 2018;19(5):990-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in U.S. emergency departments. JAMA. 2008;299(1):70-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang KH, Becker WC, Fiellin DA. Prevalence and correlates for non-medical use of prescription opioids among urban and rural residents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;127(1-3):156-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Unick GJ, Rosenblum D, Mars S, Ciccarone D. Intertwined epidemics: national demographic trends in hospitalizations for heroin- and opioid-related overdoses, 1993-2009. PloS One. 2013;8(2):e54496-e54496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rigg KK, Monnat SM. Urban vs. rural differences in prescription opioid misuse among adults in the United States: informing region specific drug policies and interventions. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(5):484-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson EM, Lanier WA, Merrill RM, et al. . Unintentional prescription opioid-related overdose deaths: description of decedents by next of kin or best contact, Utah, 2008-2009. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(4):522-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McKenna RM. Treatment use, sources of payment, and financial barriers to treatment among individuals with opioid use disorder following the national implementation of the ACA. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;179:87-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]