Abstract

Key points

Wild‐type mice and mice with hepatocyte‐specific or whole‐body deletions of perilipin‐2 (Plin2) were used to define hepatocyte and extra‐hepatocyte effects of altered cellular lipid storage on obesity and non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) pathophysiology in a Western‐diet (WD) model of these disorders.

Extra‐hepatocyte actions of Plin2 are responsible for obesity, adipose inflammation and glucose clearance abnormalities in WD‐fed mice.

Hepatocyte and extra‐hepatic actions of Plin2 mediate fatty liver formation in WD‐fed mice through distinct mechanisms.

Hepatocyte‐specific actions of Plin2 are primary mediators of immune cell infiltration and fibrotic injury in livers of obese mice.

Abstract

Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an obesity‐ and insulin resistance‐related metabolic disorder with progressive pathology. Perilipin‐2 (Plin2), a ubiquitously expressed cytoplasmic lipid droplet scaffolding protein, is hypothesized to contribute to NAFLD in humans and rodent models through effects on cellular lipid metabolism. In this study, we delineate hepatocyte‐specific and extra‐hepatocyte Plin2 mechanisms regulating the effects of obesity and insulin resistance on NAFLD pathophysiology in mice fed an obesogenic Western‐style diet (WD). Total Plin2 deletion (Plin2‐Null) fully protected WD‐fed mice from obesity, insulin resistance, adipose inflammation, steatohepatitis (NASH) and liver fibrosis found in WT animals. Hepatocyte‐specific Plin2 deletion (Plin2‐HepKO) largely protected against NASH and fibrosis and partially protected against steatosis in WD‐fed animals, but it did not protect against obesity, insulin resistance, or adipose inflammation. Significantly, total or hepatocyte‐specific Plin2 deletion impaired WD‐induced monocyte recruitment and pro‐inflammatory macrophage polarization found in livers of WT mice. Analyses of the molecular and cellular processes mediating steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis identified differences in total and hepatocyte‐specific actions of Plin2 on the mechanisms promoting NAFLD pathophysiology. Our results demonstrate that hepatocyte‐specific actions of Plin2 are central to the initiation and pathological progression of NAFLD in obese and insulin‐resistant mice through effects on immune cell recruitment and fibrogenesis. Conversely, extra‐hepatocyte Plin2 actions promote NAFLD pathophysiology through effects on obesity, inflammation and insulin resistance. Our findings provide new insight into hepatocyte and extra‐hepatocyte mechanisms underlying NAFLD development and progression.

Keywords: Obesity, Insulin Resistance, Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis, Fibrosis, Perilipin‐2

Key points

Wild‐type mice and mice with hepatocyte‐specific or whole‐body deletions of perilipin‐2 (Plin2) were used to define hepatocyte and extra‐hepatocyte effects of altered cellular lipid storage on obesity and non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) pathophysiology in a Western‐diet (WD) model of these disorders.

Extra‐hepatocyte actions of Plin2 are responsible for obesity, adipose inflammation and glucose clearance abnormalities in WD‐fed mice.

Hepatocyte and extra‐hepatic actions of Plin2 mediate fatty liver formation in WD‐fed mice through distinct mechanisms.

Hepatocyte‐specific actions of Plin2 are primary mediators of immune cell infiltration and fibrotic injury in livers of obese mice.

Introduction

Aberrant hepatocyte neutral lipid accumulation (hepatosteatosis) is proposed to be central to the pathological progression of NAFLD due to correlation between hepatosteatosis severity and subsequent development of NASH and fibrosis (Day & James, 1998). However, the precise contributions of hepatosteatosis to NAFLD disease progression remain uncertain (Day & James, 1998), due to complications arising from the effects of metabolic and immune abnormalities of obesity on NAFLD pathogenesis (Brunt et al. 2015). Furthermore, animal experiments targeting neutral lipid synthesis have led to suggestions that hepatic neutral lipid accumulation is not required for progression to NASH and fibrosis, and may actually protect against these injuries (Neuschwander‐Tetri, 2010). Significantly, the effects of disrupting the hepatocellular lipid storage mechanisms involved in aberrant hepatic lipid accumulation on liver pathogenesis are largely undefined, particularly within the context of obesity and insulin resistance that characterize human NAFLD.

Neutral lipids are stored in cytoplasmic lipid droplets (CLDs), which are organelle‐like structures with multiple dynamic roles in regulating cellular lipid homeostasis (Greenberg et al. 2011). CLDs in hepatocytes of humans and mice are enriched in perilipin‐2 (Plin2) (Straub et al. 2008; Crunk et al. 2013), a ubiquitously expressed member of the Perilipin family of CLD‐associated proteins that regulate neutral lipid storage and metabolism in eukaryotic cells (Brasaemle, 2007). Human and mouse studies have correlated hepatic Plin2 levels and the degree of hepatosteatosis in multiple types of liver disease including NAFLD (Straub et al. 2008). Importantly, total Plin2 loss, or antisense oligonucleotide suppression of Plin2 expression, protect against obesity (McManaman et al. 2013; Libby et al. 2016), hepatosteatosis (Chang et al. 2006; Imai et al. 2007; McManaman et al. 2013) and insulin resistance (Imai et al. 2007; Libby et al. 2016) in high fat diet and genetic mouse models of obesity. Plin2 lipid storage functions as determinants of obesity‐associated metabolic disorders are not fully understood, and the extent to which hepatocyte‐specific actions of Plin2 determine obesity‐associated NAFLD pathophysiology is uncertain.

Here we used prolonged Western diet (WD) feeding to define hepatocyte and extra‐hepatocyte actions of Plin2 in promoting obesity and NAFLD progression to NASH and hepatic fibrosis. Our data demonstrate that extra‐hepatocyte actions of Plin2 mediate obesity and insulin resistance in WD‐fed mice, whereas hepatocyte‐specific actions of Plin2 are primary mediators of hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in obese and insulin resistant mice.

Methods

Ethical approval

We understand the ethical principles under which The Journal of Physiology operates and confirm that our experiments comply with the published animal ethics checklist. Animals were humanely treated and killed in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edn) by personnel trained in their care. All animal experiments and procedures were approved by the University of Colorado School of Medicine's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee on protocol B79213(11)1E.

Animals and induction of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease

All mice were on the C57Bl/6J background and obtained from breeding colonies maintained within the University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Campus, AAALAC‐accredited, Centre for Comparative Medicine. All experimental animals were males and were singly housed at 22°C in microisolator cages equipped with automated air and water on a 10:14 h dark:light cycle with ad libitum access to food. Mice were fed a standard chow diet until 8 weeks of age, at which time they were fed a defined Western (WD, Teklad TD.88137) or low‐fat control (CD, Teklad TD.08485) diet for up to 30 weeks. Plin2 fl/fl and total Plin2 knockout (Plin2‐Null) mice on the C57BL/6 background have been described previously in detail (McManaman et al. 2013). Mice with hepatocyte specific deletion of Plin2 (Plin2‐HepKO) were generated by breeding Plin2 fl/fl mice with transgenic C57Bl/6 mice expressing Cre‐recombinase driven by the albumin promoter (Alb‐Cre; Jackson Laboratory, No. 003574). Hepatocyte‐specific loss of Plin2 was confirmed by transcript and immunostaining analyses of mice fed CD or WD for 30 weeks (Fig. 1).

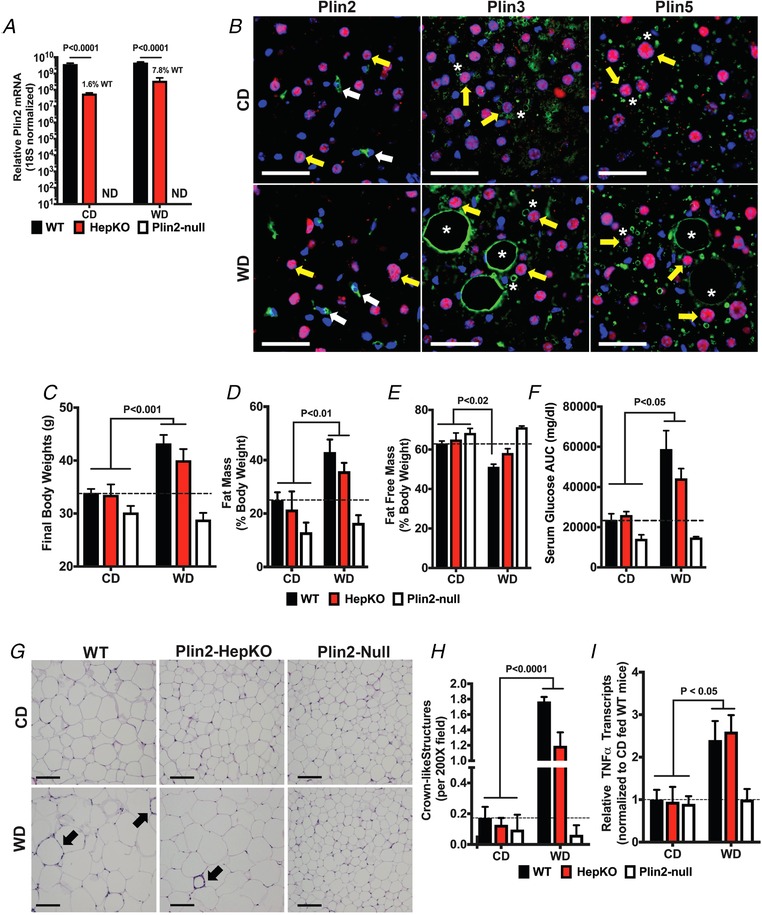

Figure 1.

Effects of WD feeding and Plin2 genotype on obesity, glucose clearance and adipose inflammation

A, relative Plin2 mRNA levels in livers of WT, Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice fed CD or WD for 30 weeks. Values are 18S RNA normalized means ± SEM (N = 4 mice per group). Plin2 was below detection levels (ND) in livers of Plin2‐Null mice. Note use of log scale for the y‐axis. B, representative liver sections from Plin2‐HepKO mice fed CD or WD for 30 weeks and immunostained for Plin2, Plin3 or Plin5 (green) and hepatocyte nuclear factor‐4 as marker of hepatocyte nuclei (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Plin2 staining (left panels) was exclusively detected on small CLDs found in sinusoidally localized hepatic stellate cells (white arrows) in both CD‐ and WD‐fed mice. Plin3 (middle panels) and Plin5 (right panels) were detected on small and large macrovesicular CLDs (asterisks) in hepatocytes (yellow arrows) of CD‐ and WD‐fed mice. Scale bars, 50 μM. C–F, final body weights (C), fat mass (D) and fat free mass (E) values as percentages of body weight, and serum glucose area under the curve values (F) for WT, Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice fed CD or WD for 30 weeks. G, representative images of Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E)‐stained epididymal adipose tissue (eWAT) sections from WT, Plin2‐HepKO or Plin2‐Null mice fed CD or WD for 30 weeks. Arrows indicate the crown‐like structures (CLS). Scale bars, 100 μm. Relative increases in CLS (H) and TNFα transcript (I) in eWAT of mice fed the WD for 30 weeks. For panels C–F, and H and I, values are means ± SEM (N = 3–6 mice per group). Values of WD‐fed mice that were statistically different from CD‐fed animals are indicated by brackets. The corresponding P values refer to the minimal statistical significance between the indicated WD‐ and CD‐fed mice. The dashed horizontal lines indicate values for CD‐fed WT mice.

Animal procedures

Body weights and food intake were monitored weekly. Body compositions of the animals were determined by quantitative magnetic resonance imaging using an EchoMRI‐900 Whole‐Body Composition Analyzer (Echo Medical Systems, Houston, TX, USA). Glucose tolerance was estimated in 18 h fasted mice by intraperitoneal injection of 2 g glucose/kg body weight. Glucose was determined in blood obtained from the tail vein prior to glucose injection and at 15, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min post injection using a calibrated glucometer, and integrated to calculate area under the curve values. At the end of the study, all animals were killed by CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation.

Gene expression analysis

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and qRT‐PCR analyses were performed as described (Libby et al. 2016). Fresh liver tissue was snap‐frozen and stored at −80°C until use. Briefly, RNA was extracted from fresh liver samples, which were snap‐frozen and stored at −80°C, using the RNeasy Plus mini kit (Qiagen), and cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad). qRT‐PCR was performed on a Bio‐Rad CFX96 instrument, using primer pairs listed in Table 1, SYBR green probes and either the iTaq SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad) or the 2XSYBR GreenqPCR Mastermix (BioTools). 18S rRNA was used to normalize gene expression and relative gene expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

Table 1.

qRT‐PCR primers

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| Plin2 | CAGCCAACGTCCGAGATTG | CACATCCTTCGCCCCAGTT |

| Plin3 | ACCTGAGGACTTTGCAACTG | CGTGGAACTGATAAGAGGCAG |

| Plin5 | GTGTGTAGTGTGACTACCTGTG | GCAGCTTCTCTTCCAATTTGTC |

| Srebp1c | GGAGCCATGGATTGCACATT | GGCCCGGGAAGTCACTGT |

| Scd1 | ACAGCCTGTTCGTTAGCACCTTCT | CCCGGGATTGAATGTTCTTGTCGT |

| Fas | GGTGTGGTGGGTTTGGTGAATTGT | TTGCTGAGGTTGGACAGCAGGATA |

| Acc1 | TAACAGAATCGACACTGGCTGGCT | ATGCTGTTCCTCAGGCTCACATCT |

| Pparγ | AGGGCGATCTTGACAGGAAAGACA | AAATTCGGATGGCCACCTCTTTGC |

| Cd36 | TCATGCCAGTCGGAGACATGCTTA | AACTGTCTGTACACAGTGGTGCCT |

| Col1a | CATAAAGGGTCATCGTGGCT | TTGAGTCCGTCTTTGCCAG |

| Timp1 | CTCAAAGACCTATAGTGCTGGC | CAAAGTGACGGCTCTGGTAG |

| Tgfβ1 | TAAAGAGGTCACCCGCGTGCTAAT | ACTGCTTCCCGAATGTCTGACGTA |

| Tnfα | TCTCAGCCTCTTCTCATTCCTGCT | AGAACTGATGAGAGGGAGGCCATT |

| Il10 | AGCCGGGAAGACAATAACTG | GGAGTCGGTTAGCAGTATGTTG |

| Ccl2 | GTCCCTGTCATGCTTCTGG | GCTCTCCAGCCTACTCATTG |

| Ccl5 | GGGTACCATGAAGATCTCTGC | TCTAGGGAGAGGTAGGCAAAG |

| Tlr2 | ACAACTTACCGAAACCTCAGAC | ACCCCAGAAGCATCACATG |

| Tlr4 | TGACACCAGGAAGCTTGAATCCCT | GGAATGTCATCAGGGACTTTGCTG |

| 18S | CGGCTTAATTTGACTCAACAC | ATCAATCTGTCAATCCTGTCC |

Lipid analyses

Hepatic lipids were analysed according to published procedures (Libby et al. 2016; Perreault et al. 2018). Frozen liver tissue was homogenized in Folch reagent (2:1 CHCl3:MeOH) containing 300 μg of tritridecanoin reference standard (Nu‐Check Prep Inc, Elysian, MN, USA) by bead‐homogenization for two cycles of 2 min at 30 Hz. Homogenates were diluted further with Folch reagent, treated with 800 μl of 0.9% sodium chloride solution, vortexed and centrifuged at 4000 g for 5 min. The organic phase was removed and dried under N2 gas. Total lipids were resuspended in 330 μl 100% chloroform and applied to HyperSep SI SPE columns (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) pre‐equilibrated with 15 column volumes chloroform. Neutral lipids were eluted with a total of 3 ml chloroform, dried under N2, and resuspended in 1 ml methanol containing 2.5% H2SO4. Fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) production was initiated by heating at 80°C for 1.5 h, 1 ml of HPLC‐grade water was added to quench the reactions, and FAMEs/cholesterol was extracted with 200 μl hexane. A Trace 1310 GC with a TG‐5MS column (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to separate lipids chromatographically, and lipids were analysed with an ISQ single quadrapole mass spectrometer. Xcalibur software (Thermo Scientific) was used to calculate peak areas. Areas were normalized to the tritridecanoin reference standard and then to tissue weight.

For diacylglycerol and ceramide analyses, samples were homogenized for 1 min in ice cold MeOH, followed by the addition of water, methyl‐tert‐butyl ether, and an internal standard cocktail. Samples were vortexed rotated for 15 min at room temperature to extract lipids and centrifuged to separate phases and the lipid containing fraction was re‐extracted. Triacylglycerol, diacylglycerol and ceramide species were analysed by an Agilent 1100 HPLC connected to an API 2000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Concentrations were determined by comparing ratios of unknowns to internal standards, with standard curves representing the majority of DAG and ceramide species run with each sample set. Quantification of lipid species was performed with MultiQuant software (Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA).

Histology, immunohistochemistry and image analysis

Histological and immunostaining (IHC) were performed as described (McManaman et al. 2013). Antibodies and their sources are listed in Table 2. Histological images were captured on an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a 17mp Olympus DP73 high‐definition, colour, digital camera using the Olympus CellSens software (Olympus, Waltham, MA, USA). Immunofluorescence images were captured on a Nikon Diaphot fluorescence microscope, or a Marianas Spinning Disc confocal microscope and analysed using SlideBook v. 6.0 (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO, USA). Immunostaining was quantified from total pixel area after normalization to DAPI (4ʹ,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole) stained DNA. Zone specific immunostaining was quantified using masking functions in SlideBook V. 6.0. In some experiments, hepatocyte nuclei were identified by immunostaining with antibodies to hepatocyte nuclear factor‐4α (HNF4α). Scoring of liver pathology used procedures adapted for mice as described (Lanaspa et al. 2018; Monks et al. 2018) from the validated histological scoring system established by Kleiner and Brunt (Kleiner et al. 2005). Scoring of adipose crown structure pathology was carried out as described previously (Monks et al. 2018). All histological scoring was conducted by a trained investigator who was blinded to the experimental conditions. All composite images were cropped and assembled using Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator.

Table 2.

Antibodies and sources

| Antibody | Source | Use |

|---|---|---|

| HNF4α | Abcam | IHC |

| Cd3 | DAKO | IHC |

| Cd45 | BD Biosciences | IHC |

| Collagen‐1 | Cedarlane | IHC |

| Collagen‐3 | Novus | IHC |

| Perilipins‐2,5 | Fitzgerald | IHC |

| Perilipin‐3 | Abcam | IHC |

| α‐Smooth muscle actin | Epitomics‐Abcam | IHC |

| Alexafluor secondary | Life Technologies | IHC |

| Cd3 (17A2) | Affymetrix | Flow |

| Cd11b (M1/70) | BD Biosciences | Flow |

| Cd45 (30‐F11) | BD Biosciences | Flow |

| Cd45R/B220 (RA3‐6B2) | BD Biosciences | Flow |

| Cd206 (CO68C2) | BioLegend | Flow |

| F4/80 (BM8) | Affymetrix | Flow |

| Ly6G (RB6‐8C5) | BD Biosciences | Flow |

| Ly6C (HK1.4) | BD Biosciences | Flow |

IHC, immunohistochemistry.

Flow cytometry

Hepatic immune cells were analysed by flow cytometry according to published procedures (McGettigan et al. 2016). Briefly, hepatic immune cells were obtained from fresh liver tissue that was homogenized and digested with collagenase IV (0.02%) for 1 h at 37°C and washed with RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) containing 10% FBS (HyClone). After lysing red blood cells in the sample using 0.16 M NH4Cl in 0.17 M Tris (pH 7.65), washing, and filtering the sample through a 70 μm filter, cells were labelled with fluor‐conjugated antibodies directed against surface antigens: CD45 (30‐F11: BD Biosciences); Ly6C (AL‐21; BD Biosciences); CD11b (M1/70; BD Biosciences); and F4/80 (BM8; eBiosciences) or against the intracellular antigen CD206 (MCA2235A647; AbD Serotec). For surface antigens, cells were labelled at 4°C for 30 min, washed twice with 1% BSA and 0.01% sodium azide in PBS and fixed in 200 μl paraformaldehyde. For CD206 labelling, cells were fixed and permeabilized using Fix&Perm reagents (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Multiparameter flow cytometry analysis was performed on a BD FACSCanto II instrument and data were analysed with BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences).

Data analysis

Data were analysed using statistical programs in Graphpad Prism 7 (La Jolla, CA, USA). Unless otherwise indicated, statistical significance was determined by two‐way ANOVA after correcting for multiple comparisons using the Dunnett's method. Data were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. Values are shown as mean ± SEM, for 3–6 animals per group.

Results

Effects of hepatocyte Plin2 deletion on WD‐induced obesity, insulin resistance and adipose inflammation

The effects of hepatocyte‐specific deletion on hepatic Plin2 levels were established in CD‐ and WD‐fed mice by transcript and immunostaining analyses. Prolonged WD feeding does not significantly influence hepatic Plin2 mRNA levels in WT mice (Libby et al. 2016). Hepatic Plin2 mRNA levels were also not significantly influenced by WD feeding in Plin2‐HepKO mice (P = 0.76, Fig 1 A). Hepatocyte deletion of Plin2 reduced total liver Plin2 mRNA to 1.6% and 7.8%, respectively, of that in CD‐ and WD‐fed WT mice (Fig. 1 A). As documented previously (Libby et al. 2016), Plin2 mRNA was not detected in livers of Plin2‐Null mice (Fig. 1 A). We demonstrated previously that Plin2 localizes to CLDs in hepatocytes and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) in livers of CD‐ and WD‐fed WT mice and is completely absent from livers of Plin2‐Null mice. As described previously (Libby et al. 2016), the small CLDs found in hepatocytes of Plin2‐Null mice are coated with perilipin‐3 (Plin3) and perilipin‐5 (Plin5), which are genetically and structurally related to Plin2, and expressed in livers of both mice and humans (Straub et al. 2008; Carr & Ahima, 2016; Hashani et al. 2018). In Plin2‐HepKO mice, Plin2 localized exclusively to CLDs in HSCs in livers of CD‐ and WD‐fed mice (Fig. 1 B), which is consistent with the absence of Plin2 from hepatocytes and the known presence of Plin2 in HSC (Straub et al. 2008; Carr & Ahima, 2016). In contrast, we detected Plin3 and Plin5 staining of small CLDs in HNF4α‐positive hepatocytes of CD‐fed, and large macrovesicular CLDs in HNF4α‐positive hepatocytes of WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO mice (Fig. 1 B).

Compared to Plin2‐Null mice, which are resistant to obesity and glucose intolerance found in WD‐fed WT mice (Libby et al. 2016), Plin2‐HepKO mice become obese and glucose intolerant after 30 weeks of WD feeding (Fig. 1 C–F). The final body weights (Fig. 1 C) and fat mass percentages (Fig. 1 D) of WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO mice were not different from those of WT mice, and were significantly greater than corresponding values of CD‐fed animals or WD‐fed Plin2‐Null mice. Conversely, fat free mass percentages of WD‐fed WT mice were significantly less, and those of WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO trended lower, than values for CD‐fed animals (Fig. 1 E). Increases in body weights and fat mass values in WD‐fed WT and Plin2‐HepKO mice were associated with increased energy consumption over that of CD‐fed littermates. WD‐fed WT and Plin2‐HepKO mice consumed an average of 12.94 ± 0.18 kcal/day and 14.70 ± 0.26 kcal/day, respectively, which was significantly greater than the average energy consumption of CD‐fed WT (11.32 ± 0.22 kcal/day; P < 0.001) and of Plin2‐HepKO (12.93 ± 0.13 kcal/day; P < 0.001). In contrast, for Plin2‐Null mice the average energy consumption of WD‐fed animals (11.89 ± 0.23 kcal/day) was not different (P = 0.56) from that of CD‐fed animals (11.56 ± 0.13 kcal/day).

We used serum glucose area under the curve (AUC) determinations following i.p. glucose injections of fasted mice to estimate glucose tolerance (Fig. 1 F). Compared to CD‐fed animals and WD‐fed Plin2‐Null mice, glucose AUC values of WD‐fed WT and Plin2‐HepKO mice were elevated 2‐ to 3‐fold (P < 0.05), and were not statistically different from each other, which suggests that they have a similar degree of glucose intolerance, indicative of insulin resistance.

Obesity in WD‐fed WT and Plin2‐HepKO mice corresponded with adipocyte hypertrophy and evidence of inflammation in epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT) (Fig. 1 G–I). Compared to CD‐fed mice and WD‐fed Plin2‐Null mice, the number of crown‐like structures (CLS), which are indicative of adipocyte death and inflammation (Cinti et al. 2005), was significantly (P < 0.0001) increased in eWAT of WD‐fed WT and Plin2‐HepKO mice (Fig. 1 H). In addition, mRNA levels of the inflammation marker Tnfα (tumor necrosis factor‐α) were increased ∼2.5‐fold (P < 0.05) in epididymal adipose of WD‐fed WT and Plin2‐HepKO mice (Fig. 1 I). These data are consistent with WD feeding promoting obesity, adipose inflammation and insulin resistance to similar extents in WT and Plin2‐HepKO mice. In contrast, Plin2‐Null mice are completely resistant to these abnormalities.

Fatty liver formation

Because obesity and insulin resistance are thought to be primary drivers of fatty liver in humans and animal models of NAFLD (Fabbrini et al. 2010), we investigated the extent to which obese WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO mice would exhibit fatty liver formation and liver injuries found in WD‐fed WT mice. We previously demonstrated that livers of Plin2‐Null mice are completely resistant to hepatomegaly induced in WT mice by WD feeding (Libby et al. 2016). In contrast, body weight corrected liver weights of WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO mice (6.2 ± 0.54 %) were significantly greater than those of CD‐fed animals (4.5 ± 0.1%) (Fig. 2 A). However, the relative liver weights of WD fed Plin2‐HepKO mice were significantly less (P < 0.0001) than those of WD‐fed WT mice (8.3 ± 0.52%) (Libby et al. 2016) (Fig. 2 A), which suggests that hepatocyte‐specific actions of Plin2 contribute to obesity‐associated hepatomegaly in WD‐fed mice. We did not detect significant differences in the relative liver weights of WT, Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null animals on the CD (Fig. 2 A).

Figure 2.

Effects of WD feeding and Plin2 genotype on fatty liver formation and NAFLD pathology

A, liver weights as percentage of body weight are presented relative to values of CD‐fed WT mice for animals fed CD or WD for 30 weeks. Values are means ± SEM (N = 3–6 mice per group). Bracket indicates values of WD‐fed mice that were statistically different from those of CD‐fed animals. The corresponding P value refers to the minimal statistical significance between the indicated WD‐ and CD‐fed mice. The asterisk indicates significant difference from WD‐fed WT mice (P < 0.01). The dashed horizontal line indicates values for CD‐fed WT mice. B, representative images of H&E‐stained liver sections of WT, Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice fed the WD or CD for 30 weeks. Green and yellow arrows in images from WD fed mice indicate hepatocytes with microvesicular and macrovesicular steatosis, respectively. PT, portal triad; CV, central vein. Scale bar, 50 μm. C–F, effects of 30 weeks of CD or WD feeding on relative hepatic levels of (C) neutral lipids (NL), (D) cholesteryl esters (CE), (E) diacylglycerol (DAG) and (F) ceramide (Cer) in WT, Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice. Values are means ± SEM (N = 3–6 mice per group). Brackets indicate values of WD‐fed mice that were statistically different from those of CD‐fed animals. The corresponding P values in these panels refer to the minimal statistical significance between the indicated WD‐ and CD‐fed mice. The asterisk in C indicates significant difference from WD‐fed WT mice (P < 0.0001). The dashed lines indicate values for CD‐fed WT mice. NS, not significant. G and H, relative levels of mRNA for Srebp1c, Scd1, Fas, and Acc1 (G), and PPARγ and Cd36 (H) in liver extracts of WT, Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice fed CD or WD for 30 weeks. Values are means ± SEM (N = 3–6 mice per group). The indicated P values in these panels refer to the statistical significance between the indicated WD and CD‐fed mice. NS, not significant. I–L, histological images of H&E‐ and PAS (periodic acid‐Schiff)‐stained liver sections from 30 week WD‐fed WT mice showing histopathological features indicative of NAFLD to NASH progression: I, inflammatory cells (arrows); J and K, foamy macrophages (arrows); L, ballooned cells (arrows). M, average NAFLD injury scores derived from data in Table 3 for WT, Plin2‐HepKO, and Plin2‐Null (the bar for Plin2‐Null animals appears to be missing because their scores were zero) fed the WD for 30 weeks. Horizontal line indicates statistically significant effects of genotype on NAFLD injury scores by one‐way ANOVA.

Hematoxylin and Eosin staining of liver sections from WD‐fed mice revealed substantial differences in the extent of hepatosteatosis, and the appearance and lobular distribution of lipid vesicles in livers of WD‐fed WT, Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice (Fig. 2 B). In contrast to the complete absence of overt hepatosteatosis previously observed in WD‐fed Plin2‐Null mice (Libby et al. 2016) (Fig. 2 B), there was substantial hepatosteatosis in Plin2‐HepKO mice. However, the extent of hepatosteatosis was markedly less than that of WT mice. Moreover, hepatosteatosis in Plin2‐HepKO mice was entirely composed of macrovesicular structures, which localized to the intermediate (zone 2) of the liver lobule. In WT mice, hepatosteatosis was panlobular and was composed of both macro‐ and microvesicular structures (Libby et al. 2016) (Fig. 2 B). Hepatosteaosis was not detected in livers of any of the CD‐fed mice (Fig. 2 B).

As expected, hepatosteatosis in WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO mice was associated with increased hepatic lipid levels compared to CD‐fed animals and to WD‐fed Plin2‐Null mice (Fig. 2 C and, D). Relative neutral lipid (NL, 2.38 ± 0.53 mmol/g) and cholesteryl ester (CE, 0.189 ± 0.05 mmol/g) levels in WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO mice were significantly increased 4.3‐fold (P = 0.004) and 13.5‐fold (P = 0.0002) respectively (Fig. 2 C and D) over corresponding NL (0.55 ± 0.06 mmol/g) and CE (0.014 ± 0.003 mmol/g) levels in CD‐fed littermates. However, NL and CE levels in WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO mice were respectively 54% (P < 0.001) and 37% (P = 0.059) less than those found in WD‐fed WT animals (Fig. 2 C and D) (Libby et al. 2016). Although hepatic diacylglycerol (DAG) levels in WD‐fed WT mice (1.42 ± 0.31 mg/g) were significantly elevated (P = 0.004) over those of CD‐fed WT mice (0.57 ± 0.07 mg/g) (Fig. 2 E), WD feeding did not significantly elevate DAG levels in livers of Plin2‐HepKO or Plin2‐Null mice (Fig. 2 E). In addition, neither WD feeding nor genotype affected hepatic ceramide levels (Fig. 2 F).

Fatty liver formation in NAFLD patients results from de novo lipid synthesis activation, as well as from increased availability and hepatic transport of free fatty acids (Fabbrini et al. 2010). We demonstrated previously (Libby et al. 2016), that total Plin2 deletion significantly reduced Srebp‐1c (sterol regulatory element binding proteins‐1c)‐regulated de novo lipid synthesis enzymes and Pparγ (peroxisomal proliferator activated receptor gamma)‐regulated expression of Cd36 (cluster of differentiation 36), the fatty acid translocase implicated in fatty liver formation in humans and mouse models of NAFLD (Miquilena‐Colina et al. 2011; Wilson et al. 2016), in WD‐fed mice. WD stimulation of Srebp‐1c, Scd1 (stearoyl‐CoA desaturase‐1), Fas (fatty acid synthase), and Acc1 (acetyl‐CoA carboxylase‐1) expression was prevented in Plin2‐HepKO mice (Fig. 2 G). In contrast, WD feeding significantly stimulated expression of Pparγ and Cd36 in Plin2‐HepKO mice (Fig. 2 H). These data indicate that hepatocyte‐specific Plin2 actions are required for WD‐induced expression of genes in the de novo lipogenesis (DNL) pathway. However, they do not appear to be required for the expression of genes regulating hepatic fatty acid uptake.

NAFLD pathophysiology

The severely steatotic livers of WD‐fed WT mice displayed marked hepatocellular hypertrophy, ballooned cells, inflammatory foci, lipogranulomas and foamy macrophages indicative of progressive inflammation and liver injury (Fig. 2 I–L). We quantified hepatic injury in all animals using a previously published NAFLD pathology injury scoring system (Lanaspa et al. 2018; Monks et al. 2018) (Table 3), which was adapted for mice from the validated liver injury scoring system used to characterize human NAFLD pathophysiology (Kleiner et al. 2005). In contrast, livers of WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO mice had only a few hypertrophied hepatocytes, no ballooned cells, and fewer lipogranulomas, foamy macrophages, and inflammatory foci than livers of WT mice (Table 3). No pathological abnormalities were detected in livers of WD‐fed Plin2‐Null mice or any CD‐fed mice (Table 3). The average NAFLD pathology injury score (Fig. 2 M) differed significantly among WD‐fed WT, Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice, with the NAFLD pathology index of WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO mice approximately half that of WD‐fed WT mice. These data identify hepatocyte‐specific and extra‐hepatocyte actions of Plin2 in the overall liver injury observed in WD induced NAFLD, and identify hepatocyte‐specific Plin2 actions as significant contributors to NAFLD pathophysiological progression in obese and insulin resistant mice.

Table 3.

NAFLD injury scores

| WT | Plin2‐HepKO | Plin2‐Null | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathology feature | Score (no. mice) | Avg ± SD | Score (no. mice) | Avg ± SD | Score (no. mice) | Avg ± SD |

| Macrovesicular steatosis | 2 (2); 1 (2) | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 2 (3); 1 (2); 0 (1) | 1.3 ± 0.75 | 0 (4) | 0 ± 0 |

| Microvesicular steatosis | 1 (4) | 1 ± 0 | 0 (6) | 0 ± 0 | 0 (4) | 0 ± 0 |

| Hypertrophy | 3 (4) | 3 ± 0 | 1 (6) | 1 ± 0 | 0 (4) | 0 ± 0 |

| Ballooning | 2 (4) | 2 ± 0 | 0 (6) | 0 ± 0 | 0 (4) | 0 ± 0 |

| Lobular inflammation | 2 (1); 1(3) | 1.25 ± 0.43 | 2 (1); 1 (3); 0(2) | 0.83 ± 0.69 | 0 (4) | 0 ± 0 |

| Inflammatory foci | 1 (3); 0 (1) | 0.75 ± 0.43 | 1 (5); 0 (1) | 0.83 ± 0.37 | 0 (4) | 0 ± 0 |

| Lipogranuloma (No./200× field) | 2 (2); 1 (2) | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1 (5); 0 (1) | 0.83 ± 0.37 | 0 (4) | 0 ± 0 |

| Foamy macrophages | 1 (4) | 1.0 ± 0 | 1 (2); 0 (4) | 0.33 ± 0.4 | 0 (4) | 0 ± 0 |

| Total | 12 ± 1 | 5.2 ± 1.9 | 0 ± 0 | |||

Macrovesicular steatosis: 3, >66%; 2, 33–66%; 1, 10–33%; 0, <10%. Microvesicular steatosis: 1, present; 0, not present. Hepatocyte hypertrophy: 3, >66%; 2, 33–66%; 1, 10–33%; 0, <10% hepatocytes. Ballooning: 2, >2/200× field; 1, 1–2/200× field; 0, <1/200× field. Lobular inflammation: 3, >4/200X field; 2, 2–4/200× field; 1, 1–2/200× field; 0, <1/200× field. Inflammatory foci: 1, present (>1/200× field); 0, absent (<1/200× field). Foamy macrophages: 1, present; 0 not present.

Hepatic fibrogenic processes

Hepatic fibrosis, characterized by fibrillary collagen accumulation in the sub‐endothelial space of Disse in response to damage (Friedman, 2008), characterizes progressive liver injury in patients with NAFLD (Day, 2006). To identify possible effects of WD feeding on hepatic fibrosis we stained liver sections CD‐ and WD‐fed mice with antibodies to fibrillary collagen type‐1 (Col1). As expected, we detected Col1 immunostaining of portal triads and central veins in liver sections from all CD‐ and WD‐fed mice (Fig. 3 A). Significantly, we also detected pronounced fibrillary collagen type‐1 (Col1) immunostaining with a central lobular sinusoidal pattern, indicative of fibrosis, in liver sections from WD‐fed WT mice, but not in liver sections of mice from the other groups. Importantly, higher magnification of liver sections co‐stained with Col1 and wheat germ agglutinin, a marker of the glycosylated protein containing endothelial surface, demonstrated that Col1 immunostaining found in the centrilobular region of WD‐fed WT mice localized to the sub‐endothelial sinusoidal surfaces (space of Disse) (Fig. 3 B), a defining feature of fibrosis. Col1 staining was also found around and through inflammatory foci and around lipogranulomas (Fig. 3 B), which is additional evidence of a fibrotic response to injury in these animals. The relative effects of diet and genotype on fibrotic changes were estimated by quantifying hepatic Col1 immunostaining that was exclusive of the portal triad and central vein. The overall lobular Col1 immunostaining of livers of WD‐fed WT mice was approximately twice that of CD‐fed mice (Fig. 3 C). However, Col1 immunostaining was detected predominately in the region between zones 2 and 3 (Fig. 3 B). When zone‐specific Col1 immunostaining was quantified, we found no difference in Col1 levels between CD‐ and WD‐fed WT mice, or between WT, Plin2‐HepKO or Plin2‐Null mice fed CD or WD, in the zone 1–2 region (Fig. 3 C). Whereas, Col1 immunostaining in the zone 2–3 region of livers of WD‐fed WT mice was approximately 3 times that of CD‐fed mice (P < 0.0001). In contrast, Col1 immunostaining of livers from WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice were not significantly different from that of CD‐fed animals (Fig. 3 C). Col1 immunostaining levels in livers of WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO or Plin2‐Null mice were not different from those of CD‐fed mice (Fig. 3 B). In WT mice, WD feeding markedly elevated transcript levels of Col1 and Timp1 (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase‐1), which inhibits collagen degradation (Friedman, 2008), by ∼40‐fold (P < 0.001) over those in CD‐fed animals (Fig. 3 D and E). We did not detect significant elevation in mRNA levels of these genes in livers of WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice (Fig. 3 D and E) compared to CD‐fed mice, although there was a non‐significant increase in Timp1 mRNA in livers of WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO mice (Fig. 3 E). Neither, Col1 staining nor Col1 and Timp1 transcript expression were affected by Plin2 genotype in CD‐fed animals (Fig. 3 B–E). Importantly, we did not detect effects of diet or genotype on immunostaining of hepatic collagen‐3, the core component of reticular fibres of the basement membrane including that of capillaries (Ushiki, 2002) (Fig. 3 F and G). Thus, WD feeding or Plin2 actions do not appear to affect the quantity of the reticular network underlying hepatic vasculature.

Figure 3.

Effects of WD feeding and Plin2 genotype on fibrotic processes

A, representative liver sections from 30‐week CD‐ and WD‐fed WT, Plin2‐HepKO, and Plin2‐Null mice stained for collagen‐1 (green). Nuclei, DAPI stained (blue). White arrows in WD‐fed mice identify collagen‐1 staining around lipogranulomas. Yellow arrow in WD‐fed WT liver section identifies collagen‐1 staining of inflammatory foci. Asterisk indicates representative sinusoidal pattern of collagen‐1 staining. PT, portal triad; CV, central vein. Lobular zones (z1 and z3) are indicated. Dashed line indicates zone 2 region used for analysis of zonal distribution of immunostaining. Scale bars, 50 μm. B, a representative immunostained liver section from a 30 week WD‐fed WT mouse showing deposition of collagen‐1 fibres (green, white arrows) beneath the sinusoidal endothelial cell layer (S), around a lipogranuloma (LG), and throughout an inflammatory cell focus (yellow arrow). Alexafluor 594‐wheat germ agglutinin staining (red) identifies glycosylated endothelial luminal surfaces. DAPI‐stained nuclei, blue. Tan arrows, endothelial cell nuclei. CV, central vein. Scale bar, 25μm. C, relative panlobular, zone 1–2 and zone 2–3 specific Col1 immunostaining levels in 3–7 randomly selected liver sections per mouse from groups of 4–6 WT, Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice fed CD or WD for 30 weeks. Values are means ± SEM. Brackets in panels indicate values of WD‐fed mice that were statistically different from those of CD‐fed animals. NS, not significant. Dashed line in panels indicates values of CD‐fed WT mice. D and E, relative mRNA levels for Collagen‐1a (D) and Timp1 (E) in livers of WT, Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice fed CD or WD for 30 weeks. Values are means ± SEM (N = 3–6 mice per group). Brackets in panels D and E indicate values of WD‐fed mice that were statistically different from those of CD‐fed animals. Dashed line in panels indicates values of CD‐fed WT mice. F, representative images of liver sections of CD‐ and WD‐fed WT, Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice immunostained for collagen‐3 (green). DAPI‐stained nuclei, blue. PT, portal triad; CV, central vein; Scale bars, 50 μm. G, quantitation of collagen‐3 immunostaining in 3–6 randomly selected liver sections per mouse from 4–6 mice per group. NS, not significant.

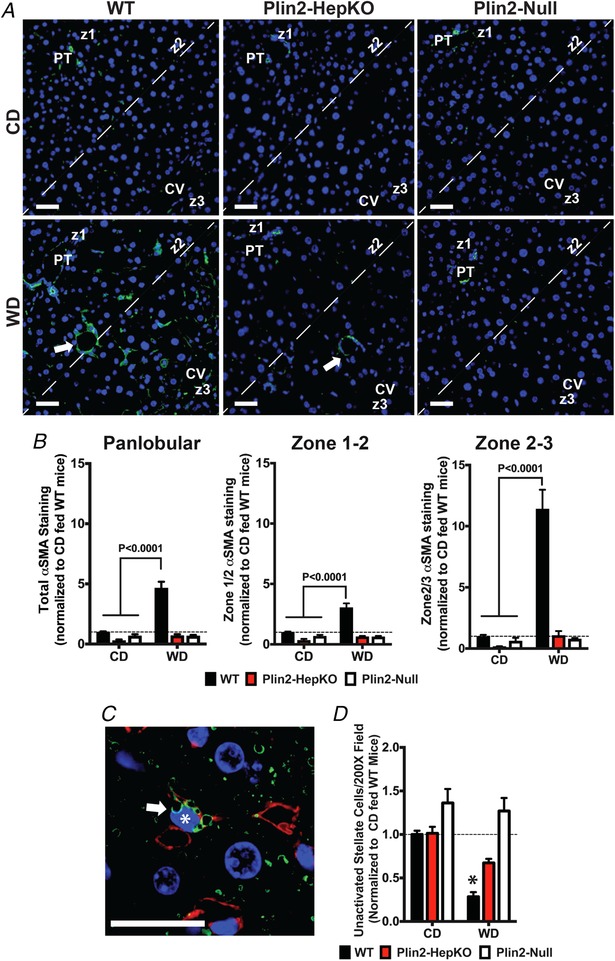

Production of sinusoidal and pericellular collagen is thought to result from activation and transdifferentiation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) to myofibroblasts (Friedman, 2008). We estimated the effects of WD and Plin2 genotype on HSC activation and transdifferentiation by first quantifying and defining the expression and lobular localization of α‐smooth muscle actin (SMA), a marker of HSC transdifferentiation (Friedman, 1993). Compared to CD‐fed mice, we found significantly (P < 0.001) elevated levels of SMA immunostaining in livers of WD‐fed WT mice, which predominantly localized to sinusoids and around lipogranulomas (Fig. 4 A). In contrast to the zone 2–3 specific localization of Col1, SMA staining was detected throughout the lobule in WD‐fed WT mice (Fig. 4 A and B). However, the magnitude of the increase in SMA staining in the zone 1–2 region (3‐fold, P < 0.001) was markedly less than that of the zone 2–3 region (11‐fold, P < 0.001), which is consistent with enhanced myofibroblast activation of Col1 expression observed in zone 2–3 of WD‐fed WT livers (Fig. 4 B). SMA immunostaining in livers of WD‐ or CD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice, was not significantly different from that of CD‐fed mice (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

Effects of WD feeding and Plin2 genotype on hepatic stellate cell activation

A, representative liver sections from 30 week CD‐ and WD‐fed WT, Plin2‐HepKO, and Plin2‐Null mice stained for α‐smooth muscle actin (SMA) (green). DAPI‐stained nuclei, blue. White arrows in WD‐fed mice indicate SMA actin staining around lipogranulomas. PT, portal triad; CV, central vein. Lobular zones (z1 and z3) are indicated. Dashed line indicates zone 2 region used for analysis of zonal distribution of immunostaining. Scale bars, 50 μm. B, relative panlobular, zone 1–2 and zone 2–3 specific SMA immunostaining quantitation in livers of WT, Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice fed CD or WD for 30 weeks. Values are means ± SEM. Brackets in panels indicate values of WD‐fed mice that were statistically different from those of CD‐fed animals. Dashed line in panels indicates values of CD‐fed WT mice. C, representative image of a quiescent hepatic stellate cell (arrow) in a liver section from a CD‐fed WT mouse, containing clusters of Plin2‐stained CLD (green) adjacent to a heterochromatic nucleus (asterisk, blue) with a ‘scalloped‐out’ shape. Cy3‐labelled WGA staining (red) identifies glycosylated sinusoids. Scale bar = 25μm. D, relative number of quiescent HSC quantified by counting sinusoidal CLD‐containing cells displaying ‘scalloped‐out’ nuclei in 10–15 randomly selected liver sections per mouse from 4–6 mice per group. Values are means ± SEM. The asterisk in D indicates significant difference from CD‐fed mice (P < 0.001). Dashed line indicates values of CD‐fed WT mice.

We next estimated numbers of non‐activated hepatic stellate cells (HSC) in liver sections of CD‐and WD‐fed mice as an additional test of the effects of WD feeding and Plin2 genotype on HSC activation. Non‐activated HSC are distinguished by prominent retinyl ester containing CLDs, which reside close to a highly heterochromatic nucleus with a ‘scalloped‐out’ shape (Friedman, 1993; Straub et al. 2008) (Fig. 4 C). In WT and Plin2‐HepKO mice, HSC CLD are coated by Plin2 (Libby et al. 2016) (Figs 1 B and 4 C). Whereas in Plin2‐Null mice, HSC CLDs are coated by Plin3 (Libby et al. 2016). In response to activation, HSCs release their CLD contents (Blaner et al. 2009), which we followed by quantifying the number of CLD‐containing HSCs in liver sections immunostained for either Plin2 or Plin3, depending on genotype. Consistent with HSC activation in livers of WD‐fed WT mice, we found significantly (P < 0.001) reduced numbers of Plin2‐positive non‐activated HSC in livers of these animals compared to CD‐fed mice (Fig. 4 D). The number of non‐activated HSC in WD‐fed WT mice was also significantly reduced compared to that found in livers of WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO (P < 0.05) or Plin2‐Null (P < 0.001) mice. The number of non‐activated HSCs in livers of WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO or Plin2‐Null mice was not significantly different from that of CD‐fed animals.

Immune infiltration

Having established that Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice were protected against WD‐induced HSC activation and fibrogenesis, we investigated if this protection correlated with suppression of hepatic immune responses. We found significant numbers of Cd45‐positive leukocytes, which are associated with NASH and fibrotic progression in humans and mouse models of NAFLD (Bertola et al. 2010; Henning et al. 2013), that disproportionately localized to lipogranulomas in liver sections of WD‐fed WT mice (Fig. 5 A). Cd45 immunostaining in livers of WD‐fed WT mice was ∼4.5 times (P < 0.001) that found in control mice, and was largely confined to the zone 2–3 region of the liver (Fig. 5 B), where collagen fibre deposition was also elevated (Fig. 4 B). Importantly, the number of Cd45‐positive lymphocytes in livers of WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice did not differ significantly from that of CD‐fed mice (Fig. 5 B). In addition to Cd45‐positive cells, we also detected significant numbers of Cd3+ T cells, which are linked to fibrotic progression in humans and some mouse models of NASH (Tajiri et al. 2009; Syn et al. 2010), around lipogranulomas in livers of WD‐fed WT mice (Fig. 5 C). In contrast, Cd3+ T cells in livers of CD‐fed mice were confined to the luminal space of sinusoids (Fig. 5 C). The number of Cd3+ T cells in livers of WD‐fed WT mice was ∼3 times greater (P < 0.001) than that in livers of CD‐fed WT mice or in WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO or Plin2‐Null mice (Fig. 5 D).

Figure 5.

Effects of WD feeding and Plin2 genotype on immune cell activation

A, representative H&E‐ (left panel), PAS‐ (middle panel) and Cd45‐immunostained (green, right panel) liver sections showing the presence of Cd45‐positive monocytes (yellow arrows) around a lipogranuloma. Scale bar = 25 μm. B, relative panlobular, zone 1–2 and zone 2–3 specific Cd45 immunostaining levels in 10–15 randomly selected liver sections per mouse from 4–6 mice per group. Values are means ± SEM. Brackets in panels indicate values of WD‐fed mice that were statistically different from those of CD‐fed animals. Dashed line in panels indicates values of CD‐fed WT mice. NS, not significant. C, 3D confocal images of Cd3‐immunostained liver sections from 30 week CD‐ or WD‐fed WT mice showing Cd3‐positive T cells localized within a sinusoid (S) of CD‐fed mice (arrow), and at the lipogranuloma (LG) margin (arrow) in WD‐fed mice. Cy3‐WGA staining (red) identifies glycosylated sinusoidal and lipogranuloma surfaces. DAPI‐stained nuclei (blue). Scale bar = 25 μm. D, relative Cd3 immunostaining normalized to DAPI stained nuclei in 10–15 randomly selected liver sections per mouse from 4–6 mice per group of WT, Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice fed CD or WD for 30 weeks. Values are means ± SEM. Bracket indicates values of WD‐fed mice that were statistically different from those of CD‐fed animals. Dashed line in panels indicates values of CD‐fed WT mice. E–L, relative hepatic transcript levels of Tgfβ1 (E), TNFα (F), IL10 (G), IL33 (H), CCL2 (I), CCL5 (J), TLR4 (K), and TLR2 (L) in mice fed the CD or WD for 30 weeks. Values are means ± SEM (N = 3–6 mice per group). Brackets in panels E–L indicate values of WD‐fed mice that were statistically different from those of CD‐fed animals. P values refer to the minimal statistical significance between the indicated WD‐ and CD‐fed mice. NS, not significant.

The mechanisms regulating hepatic immune cell recruitment, HSC activation, and fibrogenesis during NAFLD progression are complex, involving cooperative actions of diverse cytokine, chemokine, and pattern recognition signalling pathways (Holt et al. 2008; Guo & Friedman, 2010). In agreement with known roles of Tgfβ1(transforming growth factor‐β1) and Tnfα in inflammation‐induced HSC activation and hepatic fibrogenesis (Holt et al. 2008), we found that hepatic transcript levels of these genes in WD‐fed WT mice were each elevated by ∼3.5‐fold (P < 0.05) over levels in control mice (Fig. 5 E and F). Additionally, WD feeding of WT mice significantly elevated mRNA of cytokine, chemokine and Toll‐like receptor (TLR) genes implicated in immune cell activation and/or recruitment, and liver fibrosis, including Il33 (interleukin‐33) (McHedlidze et al. 2013) (2.4‐fold, P < 0.01), Ccl2/Mcp‐1 (chemokine ligand‐2/monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1) (Braunersreuther et al. 2012) (7.6‐fold, P < 0.001), and Tlr‐2 (4.5‐fold, P < 0.001) and ‐4 (2.2‐fold, P < 0.01) (Guo & Friedman, 2010), over control values (Fig. 5 H, I, K and L). Although Ccl5 (chemokine ligand‐5) mRNA levels were elevated in livers of WD‐fed WT mice compared to their CD‐fed counterparts, the increase was not significant due to marked variability in levels among WD‐fed WT mice (Fig. 5 J). In addition to increases in transcripts of pro‐fibrotic and pro‐inflammatory genes, we found that mRNA for Il10 (interleukin‐10) (Fig. 5 G), an inflammation‐induced anti‐inflammatory cytokine that is increased in steatotic livers of obese patients (Bertola et al. 2010) and in mouse models of diet‐induced NASH (Clapper et al. 2013), was significantly increased (3.3‐fold, P < 0.001) in livers of WD‐fed WT mice. The effects of WD feeding on the expression of each of these fibrosis and immune mediators was completely blocked in Plin2‐Null mice, suggesting that total Plin2 deletion fully protects against activation of hepatic inflammatory and fibrotic pathways in WD‐induced NAFLD. Hepatocyte‐specific Plin2 deletion prevented significant increases in mRNA levels of Tnfα, Il33, Ccl2 and Tlr4 in livers of WD‐fed mice (Fig. 5 F, H, I and K), although Tnfα, Ccl2 and Tlr4 transcript levels in WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO mice trended higher than in CD‐fed mice. Hepatic transcript levels of Tgfβ1, Il10 and Tlr2 were significantly elevated in WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO mice compared to CD‐fed animals (Fig. 5 E, G and L), and mRNA levels of these genes were not significantly different from those of WD‐fed WT mice. Collectively, these results indicate that total and hepatocyte‐specific Plin2 deletion differ in their effects on hepatic pro‐inflammatory and pro‐fibrogenic pathways activated by WD feeding, and suggest that hepatocyte‐specific Plin2 deletion may interfere with certain distinct pro‐inflammatory pathways involved in hepatic inflammatory cell recruitment.

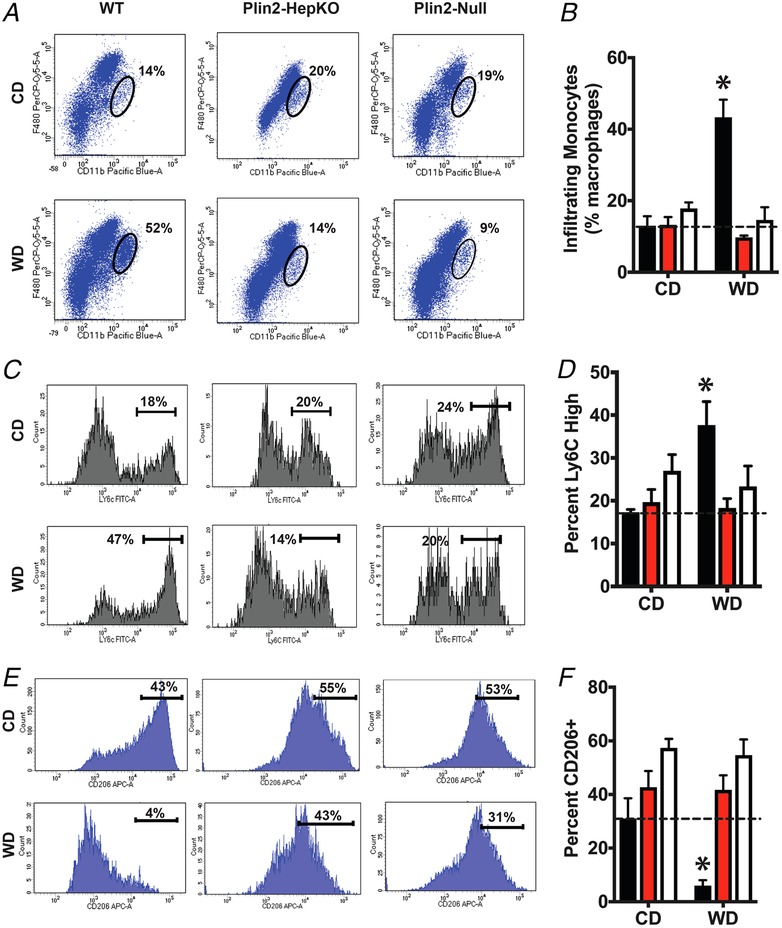

Macrophage recruitment and polarization

To directly test the role of hepatocyte Plin2 in hepatic recruitment of inflammatory cells, we quantified monocytes in livers of CD‐and WD‐fed mice by flow cytometry (Fig. 6). For these studies, we fed mice WD or CD for 6 weeks to identify possible alterations in hepatic immune phenotype prior to observable fibrotic injury, which requires 20–30 weeks of WD feeding (data not shown). Intra‐hepatic monocytes were identified by staining with antibodies to Cd45, Cd11b and F4/80 to distinguish infiltrating monocytes from Kupffer cells (Heymann & Tacke, 2016). For WT mice, the Cd45+ cell population in livers of WD‐fed animals was significantly enriched (45%) in cells that were Cd11b‐high (Cd11bhigh) and F4/80 intermediate F4/80int, indicating that they were monocyte‐derived macrophages (Heymann & Tacke, 2016) (Fig. 6 A and B). In contrast, hepatic populations of Cd45+/Cd11bhigh/F4/80int cells in WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO (10%) and Plin2‐Null (14%) mice were significantly reduced compared to those of WD‐fed WT animals and did not differ significantly from values found in CD‐fed mice (Fig. 6 A).

Figure 6.

Inflammatory cell recruitment

Flow cytometry analyses of hepatic immune cells in WT, Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice fed CD or WD for 6 weeks (N = 5 for each treatment group). A and B, representative flow cytometry profiles (A) and quantitation (B) of peripheral monocyte‐derived macrophages (F4/80‐intermediate and CD11b‐high) as a percentage of total macrophages in the Cd45+ fraction in livers of CD‐ and WD‐fed mice. Ovals in the representative flow profiles shown in A indicate gating settings used to identify monocyte derived macrophages. The corresponding quantities are shown next to each oval. C and D, representative flow cytometry profiles (C) and quantitation (D) of proinflammatory (Ly6c‐high) macrophages and quantitation of Ly6C+ cells are shown as a percentage of total Kupffer cells in CD‐ and WD‐fed mice. E and F, representative flow cytometry profiles (E) and quantitation of M2 polarized (CD206+) macrophages as a percentage of total infiltrating monocytes. Values are average percentages of total macrophages. Brackets in representative flow profiles shown in panels C and E indicate gating settings used to identify Ly6C high and CD206+ cell,s respectively. Their corresponding quantities are shown next to the respective bracket. Asterisks in B, D and F indicate values that were significantly different from CD‐fed mice.

To define the monocyte‐derived macrophage population further, we quantified the percentage of pro‐inflammatory (Ly6Chigh/M1) (Fig. 6 C and D) and anti‐inflammatory (Cd206+/M2) (Fig. 6 E and F) macrophages in livers of CD‐and WD‐fed mice. WD‐fed WT mice contained significantly elevated numbers of Ly6Chigh macrophages (38%), and significantly reduced numbers of Cd206+ macrophages (6%) compared to WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice, and to all CD‐fed mice (Fig. 6 B and C). There was no difference in the number of hepatic Ly6Chigh or Cd206+ macrophages between Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice fed the WD, or between WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO and Plin2‐Null mice and CD‐fed mice. Thus, WD feeding appears to promote hepatic recruitment of pro‐inflammatory macrophages in WT mice after as few as 6 weeks of exposure, through processes that involve hepatocyte‐specific actions of Plin2.

Discussion

Our study identifies hepatocyte‐specific and extra‐hepatocyte actions of Plin2, a prominent scaffold protein of lipid storage structures in mammalian cells, as determinants of NAFLD pathological progression to NASH and fibrotic liver injury in WD‐fed mice. Significantly, we provide evidence that Plin2‐regulated hepatocyte lipid metabolism promotes microvesicular steatosis and is crucial to the progression and the severity of NAFLD in obese individuals, whereas extra‐hepatocyte Plin2 actions promote NAFLD pathogenesis through effects on obesity, adipose inflammation, macrosteatosis, and insulin resistance.

Hepatic lipid accumulation in obese, insulin resistant, NAFLD patients results from both increased uptake of elevated serum fatty acids and the stimulation of de novo lipogenesis (Donnelly et al. 2005; Lambert et al. 2014). Our data indicate, that in obese, insulin resistant mice, these processes are regulated, in part, by the combined hepatocyte‐specific and extra‐hepatocyte actions of Plin2. The reduction of hepatic lipid levels observed in obese WD‐fed Plin2HepKO mice corresponds with the inhibition of obesity‐related increases in Srebp‐1c expression and the expression of Srebp‐1c‐regulated lipogenic enzymes, Acc1, Fas, and Scd1. Conversely, hepatocyte‐specific deletion of Plin2 did not inhibit obesity‐dependent activation of Pparγ or CD36 expression, which are implicated in the promotion of fatty liver formation by stimulating hepatic fatty acid uptake (Inoue et al. 2005; Miquilena‐Colina et al. 2011). Importantly, the complete prevention of fatty liver formation found in WD‐fed Plin2‐Null mice corresponds with inhibition of both the DNL and the Pparγ/Cd36 pathways (Libby et al. 2016). These findings raise the possibility that hepatocyte‐specific Plin2 actions promote fatty liver formation in obese mice through selective effects on the DNL pathway, while extra‐hepatic Plin2 actions appear to enhance fatty liver formation through effects on the Pparγ/Cd36‐regulated fatty acid uptake. However, Plin2 also functions in the regulation of lipolysis (Sapiro et al. 2009) and endoplasmic reticulum stress responses (Libby et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2017), both of which can influence hepatic lipid accumulation. Thus, additional studies of the effects of hepatic Plin2 expression on the levels and activities of hepatic DNL enzymes and lipid flux (Lambert et al. 2014) will be needed to precisely establish the functional importance of Plin2 in regulating the effects of obesity on DNL and fatty acid uptake, and their contributions to fatty liver formation.

Our observations that leukocytes, T‐cells, and peripherally derived pro‐inflammatory macrophages are elevated in livers of WD‐fed WT mice are consistent with evidence of hepatic recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells in NASH found in humans (Haukeland et al. 2006) and other animal models (Obstfeld et al. 2010; Miura et al. 2012). Both hepatocyte‐specific and total Plin2 deletion provided similar protection against these responses, suggesting that hepatocyte functions of Plin2 may be primary contributors to inflammatory immune infiltration and/or activation associated with progression to NASH in WD‐fed mice. Additionally, the demonstration that hepatocyte specific and total Plin2 deletions produced similar shifts in the ratio of M1 to M2 macrophages to the M2 phenotype in livers WD‐fed mice implicate hepatocyte actions of Plin2 as an important pathophysiological determinant of macrophage polarization responses during inflammatory cell infiltration, as well as the collagen accumulation phases of NASH progression.

Consistent with mechanistic diversity and cooperative interactions of processes regulating immune cell recruitment and activation during NAFLD progression (Holt et al. 2008; Guo & Friedman, 2010), our data show that WD feeding stimulates expression of genes encoding multiple cytokine, chemokine and pattern recognition factors implicated in NASH and fibrosis. Although we did not quantify serum or tissue levels of these factors in our study, the demonstration that their transcript levels are differentially suppressed in WD‐fed Plin2‐Null and Plin2‐HepKO mice suggests the hypothesis that Plin2‐regulated lipid storage contributes to processes that regulate hepatic immune cell recruitment and activation through cooperative hepatocyte and extra‐hepatocyte actions. Significantly, the observation that Tgfβ1, Tnfα, Il10, or Ccl5 transcript levels in livers of WD‐fed Plin2‐HepKO mice were not different from those of WT mice, whereas total Plin2 deletion completely blocked their elevation, indicates that activation of pathways regulating the expression of these factors may be selectively related to extra‐hepatocyte Plin2 actions associated with obesity, which potentially involve effects on intestinal epithelial cell and/or gut microbial properties (Frank et al. 2015; Xiong et al. 2017), and possibly adipose cytokines/adipokines of crown structure origin. Future studies that define how hepatocyte and extra‐hepatocyte actions of Plin2 affect levels of factors implicated in the regulation of hepatic immune cell recruitment and activation will be required to understand their functional importance in promoting NASH progression, and the contributions of Plin2 to the cellular mechanisms regulating this process.

The progression of steatosis to NASH and fibrosis is a multistep process involving hepatocyte injury, HSC activation and transformation to sinusoidal myofibroblasts producing fibrillar collagens (Friedman, 1993). Our data are consistent with activation of each of these processes in 30 week WD‐fed WT mice. Importantly, the complete suppression of WD‐induced increases in both SMA and Col1a levels and Col1a and Timp1(tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase‐1) activation observed in Plin2‐HepKO mice, indicates that hepatocyte‐specific actions of Plin2 are primary determinants of fibrotic progression in obesity‐associated NAFLD through combined effects on the pathophysiological processes regulating HSC activation and the synthesis and degradation of collagen fibres. Additional work is needed to delineate precisely how hepatocyte actions of Plin2 influence HSC activation and fibrosis. However, our findings are consistent with the reported communication between hepatocytes and HSCs (Marrone et al. 2016) and evidence linking hepatocyte DNL activation to hepatic fibrosis in NASH patients (Pinkosky et al. 2017; Lawitz et al. 2018; Loomba et al. 2018).

The observation that protection against HSC activation and fibrogenesis in Plin2‐HepKO mice was not associated with significant Tgfβ1 transcript reduction suggests that Tgfβ1 regulation of HSC activation is not a primary target of hepatocyte Plin2 action, although we cannot discount the possibility that Plin2 influences Tgfβ1‐regulated signalling pathways. Alternatively, immune cell factors acting at multiple levels have been shown to be critical to the initiation and perpetuation of HSC activation and fibrogenesis in response to various forms of liver injury (Holt et al. 2008). The demonstration that hepatocyte Plin2 is an important determinant of immune cell infiltration prior to the appearance of fibrosis, thus suggests the hypothesis that hepatocyte effects of Plin2 on HSC activation and fibrosis are mediated indirectly by effects on hepatic immune cell properties.

In summary, our results support a mechanism of NAFLD pathogenesis in obese and insulin resistant mice in which both hepatocyte‐specific and extra‐hepatocyte actions of Plin2 on lipid storage and metabolism promote activation of inflammatory and fibrotic processes of progressive liver injury. Significantly, our demonstration that the protective effects of hepatocyte Plin2 deletion on NAFLD progression are independent of obesity complications supports the concept that hepatocyte dysfunction related to de novo lipid synthesis and lipid accumulation are central to NASH pathogenic process(es). Additional studies are needed to determine how our results translate to humans. However, antisense oligonucleotide dependent disruption of hepatic Plin2 expression has been shown to protect against high fat diet‐induced fatty liver in mice (Imai et al. 2007), thus similar targeting of hepatocyte specific lipid accumulation may provide an avenue of intervention for treating NAFLD in humans.

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

D.J.O.: data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, drafted manuscript, study supervision; A.E.L.: data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, revised manuscript; E.S.B.: data acquisition, technical support; R.H.M.: data acquisition, analysis and interpretation); J.M.: data acquisition, revised manuscript; F.G.L.R.: data acquisition, material support; J.L.M.: data analysis and interpretation, drafted manuscript, statistical analysis; obtained funding; study supervision.

Funding

The work was supported by NIH grants: 2RO1‐HD045965 and R01‐HD075285 (J.L.M.); R01‐HD093729 (J.L.M. and J.M.); CCTSI/National Institutes of Health Grant TL1‐TR001081 (A.E.L.); P30CA046934 (University of Colorado Cancer Centre Support Grant); and DK48520 (the Colorado Nutrition and Obesity Research Centre).

Author's present address

A.E. Libby: Department of Biochemistry and Molecular and Cellular Biology, Georgetown University, Washington, DC 20057, USA

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the contribution to this research made by the University of Colorado Denver Histology Shared Resource Facility and thank Drs Kathleen Harrison and Bryan Bergman for help with lipid analysis. Sean Colgan and Andrew Bradford are acknowledged for critically reviewing the manuscript and helpful comments.

Biographies

David Orlicky is an Associate Professor of Pathology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. Dr Orlicky received an MS in Molecular Biology from the University of New Mexico in 1976 and obtained a PhD in experimental pathology from the University of Colorado in 1984. He teaches histopathology at the graduate level and is the author of more than 90 manuscripts related to molecular biology and pathophysiology. His primary research interests are the pathological mechanisms of metabolic disease.

Andrew Libby is currently a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Georgetown University in Washington DC. Dr Libby received a PhD in integrated physiology from the University of Colorado in 2018 for research on perilipin‐2 regulation of fatty liver formation and adipose browning in the laboratory of Dr James McManaman. Dr Libby's primary research interests are in the areas of lipid biology and metabolic disease.

Edited by: Peying Fong & Kim Barrett

D. J. Orlicky and A. E. Libby contributed equally to this work.

Linked articles: This article is highlighted in a Perspectives article by Kennedy et al. To read this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1113/JP277539.

References

- Bertola A, Bonnafous S, Anty R, Patouraux S, Saint‐Paul MC, Iannelli A, Gugenheim J, Barr J, Mato JM, Le Marchand‐Brustel Y, Tran A & Gual P (2010). Hepatic expression patterns of inflammatory and immune response genes associated with obesity and NASH in morbidly obese patients. PLoS One 5, e13577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaner WS, O'Byrne SM, Wongsiriroj N, Kluwe J, D'Ambrosio DM, Jiang H, Schwabe RF, Hillman EM, Piantedosi R & Libien J (2009). Hepatic stellate cell lipid droplets: a specialized lipid droplet for retinoid storage. Biochim Biophys Acta 1791, 467–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasaemle DL (2007). The perilipin family of structural lipid droplet proteins: Stabilization of lipid droplets and control of lipolysis. J Lipid Res 48, 2547–2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunersreuther V, Viviani GL, Mach F & Montecucco F (2012). Role of cytokines and chemokines in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 18, 727–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunt EM, Wong VW, Nobili V, Day CP, Sookoian S, Maher JJ, Bugianesi E, Serlin CB, Neuschwander‐Tetri BA & Rinella M (2015). Nonalcoholic fatty live disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 1, 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr RM & Ahima RS (2016). Pathophysiology of lipid droplet proteins in liver diseases. Exp Cell Res 340, 187–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang BH, Li L, Paul A, Taniguchi S, Nannegari V, Heird WC & Chan L (2006). Protection against fatty liver but normal adipogenesis in mice lacking adipose differentiation‐related protein. Mol Cell Biol 26, 1063–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Tsai TH, Li L, Saha P, Chan L & Chang BH (2017). PLIN2 is a key regulator of the unfolded protein response and endoplasmic reticulum stress resolution in pancreatic beta cells. Sci Rep 7, 40855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinti S, Mitchell G, Barbatelli G, Murano I, Ceresi E, Faloia E, Wang S, Fortier M, Greenberg AS & Obin MS (2005). Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J Lipid Res 46, 2347–2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapper JR, Hendricks MD, Gu G, Wittmer C, Dolman CS, Herich J, Athanacio J, Villescaz C, Ghosh SS, Heilig JS, Lowe C & Roth JD (2013). Diet‐induced mouse model of fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis reflecting clinical disease progression and methods of assessment. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 305, G483–G495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crunk AE, Monks J, Murakami A, Jackman M, Maclean PS, Ladinsky M, Bales ES, Cain S, Orlicky DJ & McManaman JL (2013). dynamic regulation of hepatic lipid droplet properties by diet. PLoS One 8, e67631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day CP (2006). Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease: current concepts and management strategies. Clin Med (Lond) 6, 19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day CP & James OF (1998). Hepatic steatosis: innocent bystander or guilty party? Hepatology 27, 1463–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly KL, Smith CI, Schwarzenberg SJ, Jessurun J, Boldt MD & Parks EJ (2005). Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest 115, 1343–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbrini E, Sullivan S & Klein S (2010). Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: biochemical, metabolic, and clinical implications. Hepatology 51, 679–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank DN, Bales ES, Monks J, Jackman MJ, MacLean PS, Ir D, Robertson CE, Orlicky DJ & McManaman JL (2015). Perilipin‐2 modulates lipid absorption and microbiome responses in the mouse intestine. PLoS One 10, e0131944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SL (1993). Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. The cellular basis of hepatic fibrosis. Mechanisms and treatment strategies. N Engl J Med 328, 1828–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SL (2008). Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology 134, 1655–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg AS, Coleman RA, Kraemer FB, McManaman JL, Obin MS, Puri V, Yan QW, Miyoshi H & Mashek DG (2011). The role of lipid droplets in metabolic disease in rodents and humans. J Clin Invest 121, 2102–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J & Friedman SL (2010). Toll‐like receptor 4 signaling in liver injury and hepatic fibrogenesis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 3, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashani M, Witzel HR, Pawella LM, Lehmann‐Koch J, Schumacher J, Mechtersheimer G, Schnolzer M, Schirmacher P, Roth W & Straub BK (2018). Widespread expression of perilipin 5 in normal human tissues and in diseases is restricted to distinct lipid droplet subpopulations. Cell Tissue Res 374, 121–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haukeland JW, Damas JK, Konopski Z, Loberg EM, Haaland T, Goverud I, Torjesen PA, Birkeland K, Bjoro K & Aukrust P (2006). Systemic inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is characterized by elevated levels of CCL2. J Hepatol 44, 1167–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning JR, Graffeo CS, Rehman A, Fallon NC, Zambirinis CP, Ochi A, Barilla R, Jamal M, Deutsch M, Greco S, Ego‐Osuala M, Bin‐Saeed U, Rao RS, Badar S, Quesada JP, Acehan D & Miller G (2013). Dendritic cells limit fibroinflammatory injury in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology 58, 589–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymann F & Tacke F (2016). Immunology in the liver – from homeostasis to disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 13, 88–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt AP, Salmon M, Buckley CD & Adams DH (2008). Immune interactions in hepatic fibrosis. Clin Liver Dis 12, 861–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Varela GM, Jackson MB, Graham MJ, Crooke RM & Ahima RS (2007). Reduction of hepatosteatosis and lipid levels by an adipose differentiation‐related protein antisense oligonucleotide. Gastroenterology 132, 1947–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Ohtake T, Motomura W, Takahashi N, Hosoki Y, Miyoshi S, Suzuki Y, Saito H, Kohgo Y & Okumura T (2005). Increased expression of PPARgamma in high fat diet‐induced liver steatosis in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 336, 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, Cummings OW, Ferrell LD, Liu YC, Torbenson MS, Unalp‐Arida A, Yeh M, McCullough AJ & Sanyal AJ (2005). Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 41, 1313–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JE, Ramos‐Roman MA, Browning JD & Parks EJ (2014). Increased de novo lipogenesis is a distinct characteristic of individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 146, 726–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanaspa MA, Andres‐Hernando A, Orlicky DJ, Cicerchi C, Jang C, Li N, Milagres T, Kuwabara M, Wempe MF, Rabinowitz JD, Johnson RJ & Tolan DR (2018). Ketohexokinase C blockade ameliorates fructose‐induced metabolic dysfunction in fructose‐sensitive mice. J Clin Invest 128, 2226–2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawitz EJ, Coste A, Poordad F, Alkhouri N, Loo N, McColgan BJ, Tarrant JM, Nguyen T, Han L, Chung C, Ray AS, McHutchison JG, Subramanian GM, Myers RP, Middleton MS, Sirlin C, Loomba R, Nyangau E, Fitch M, Li K & Hellerstein M (2018). Acetyl‐CoA carboxylase inhibitor GS‐0976 for 12 weeks reduces hepatic de novo lipogenesis and steatosis in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 16:1983–1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby AE, Bales E, Orlicky DJ & McManaman JL (2016). Perilipin‐2 deletion impairs hepatic lipid accumulation by interfering with sterol regulatory element‐binding protein (SREBP) activation and altering the hepatic lipidome. J Biol Chem 291, 24231–24246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomba R, Kayali Z, Noureddin M, Ruane P, Lawitz EJ, Bennett M, Wang L, Harting E, Tarrant JM, McColgan BJ, Chung C, Ray AS, Subramanian GM, Myers RP, Middleton MS, Lai M, Charlton M & Harrison SA (2018). GS‐0976 reduces hepatic steatosis and fibrosis markers in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 155, 1463–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGettigan BM, McMahan RH, Luo Y, Wang XX, Orlicky DJ, Porsche C, Levi M & Rosen HR (2016). Sevelamer improves steatohepatitis, inhibits liver and intestinal farnesoid X receptor (FXR), and reverses innate immune dysregulation in a mouse model of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem 291, 23058–23067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHedlidze T, Waldner M, Zopf S, Walker J, Rankin AL, Schuchmann M, Voehringer D, McKenzie AN, Neurath MF, Pflanz S & Wirtz S (2013). Interleukin‐33‐dependent innate lymphoid cells mediate hepatic fibrosis. Immunity 39, 357–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManaman JL, Bales ES, Orlicky DJ, Jackman M, MacLean PS, Cain S, Crunk AE, Mansur A, Graham CE, Bowman TA & Greenberg AS (2013). Perilipin‐2‐null mice are protected against diet‐induced obesity, adipose inflammation, and fatty liver disease. J Lipid Res 54, 1346–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrone G, Shah VH & Gracia‐Sancho J (2016). Sinusoidal communication in liver fibrosis and regeneration. J Hepatol 65, 608–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquilena‐Colina ME, Lima‐Cabello E, Sanchez‐Campos S, Garcia‐Mediavilla MV, Fernandez‐Bermejo M, Lozano‐Rodriguez T, Vargas‐Castrillon J, Buque X, Ochoa B, Aspichueta P, Gonzalez‐Gallego J & Garcia‐Monzon C (2011). Hepatic fatty acid translocase CD36 upregulation is associated with insulin resistance, hyperinsulinaemia and increased steatosis in non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis and chronic hepatitis C. Gut 60, 1394–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K, Yang L, van Rooijen N, Ohnishi H & Seki E (2012). Hepatic recruitment of macrophages promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through CCR2. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 302, G1310–G1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monks J, Orlicky DJ, Stefanski AL, Libby AE, Bales ES, Rudolph MC, Johnson GC, Sherk VD, Jackman MR, Williamson K, Carlson NE, MacLean PS & McManaman JL (2018). Maternal obesity during lactation may protect offspring from high fat diet‐induced metabolic dysfunction. Nutr Diabetes 8, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuschwander‐Tetri BA (2010). Hepatic lipotoxicity and the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: the central role of nontriglyceride fatty acid metabolites. Hepatology 52, 774–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obstfeld AE, Sugaru E, Thearle M, Francisco AM, Gayet C, Ginsberg HN, Ables EV & Ferrante AW Jr (2010). C‐C chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) regulates the hepatic recruitment of myeloid cells that promote obesity‐induced hepatic steatosis. Diabetes 59, 916–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreault L, Newsom SA, Strauss A, Kerege A, Kahn DE, Harrison KA, Snell‐Bergeon JK, Nemkov T, D'Alessandro A, Jackman MR, MacLean PS & Bergman BC (2018). Intracellular localization of diacylglycerols and sphingolipids influences insulin sensitivity and mitochondrial function in human skeletal muscle. JCI Insight 3, e96805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkosky SL, Groot PHE, Lalwani ND & Steinberg GR (2017). Targeting ATP‐citrate lyase in hyperlipidemia and metabolic disorders. Trends Mol Med 23, 1047–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapiro JM, Mashek MT, Greenberg AS & Mashek DG (2009). Hepatic triacylglycerol hydrolysis regulates peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor alpha activity. J Lipid Res 50, 1621–1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub BK, Stoeffel P, Heid H, Zimbelmann R & Schirmacher P (2008). Differential pattern of lipid droplet‐associated proteins and de novo perilipin expression in hepatocyte steatogenesis. Hepatology 47, 1936–1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syn WK, Oo YH, Pereira TA, Karaca GF, Jung Y, Omenetti A, Witek RP, Choi SS, Guy CD, Fearing CM, Teaberry V, Pereira FE, Adams DH & Diehl AM (2010). Accumulation of natural killer T cells in progressive nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 51, 1998–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajiri K, Shimizu Y, Tsuneyama K & Sugiyama T (2009). Role of liver‐infiltrating CD3+CD56+ natural killer T cells in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 21, 673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushiki T (2002). Collagen fibers, reticular fibers and elastic fibers. A comprehensive understanding from a morphological viewpoint. Arch Histol Cytol 65, 109–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CG, Tran JL, Erion DM, Vera NB, Febbraio M & Weiss EJ (2016). Hepatocyte‐specific disruption of CD36 attenuates fatty liver and improves insulin sensitivity in HFD‐fed mice. Endocrinology 157, 570–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X, Bales ES, Ir D, Robertson CE, McManaman JL, Frank DN & Parkinson J (2017). Perilipin‐2 modulates dietary fat‐induced microbial global gene expression profiles in the mouse intestine. Microbiome 5, 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]