Abstract

Objective. To characterize the religiosity and spirituality of final year pharmacy students and examine the impact on performance in pharmacy school and future practice.

Methods. An electronic survey was sent to 308 students in their final year of pharmacy school at four universities (two private and two public institutions).

Results. There were 141 respondents to the survey for a response rate of 46%. Key findings are religiosity/spirituality did not impact academic performance, students felt supported in their spiritual/religious beliefs, religiosity/spirituality had a positive impact on students’ emotional/mental well-being, attending pharmacy school decreased organized religion, less than half of the students would work for a pharmacy not allowing the “right to refuse to dispense,” students felt religiosity/spirituality could affect health/medication adherence, and most students were not familiar with how to conduct a spiritual assessment.

Conclusion. Pharmacy schools should find ways to acknowledge and support religiosity/spirituality for pharmacy students and for promoting holistic patient well-being.

Keywords: spirituality, religiosity, student pharmacists, pharmacy education

INTRODUCTION

In the last several years, there has been a resurgence of interest in the impact of religiosity and spirituality (R/S) on health.1 Spirituality is defined as “a personal search toward understanding questions about life, its meaning, and its relationships to sacredness or transcendence that may or may not lead to the development of religious practices or formation of religious communities.” Religiosity is defined as the “extent to which an individual believes, follows, and practices a religion, either organizational (church or temple attendance) or non-organizational (praying, reading books, or watching religious programs on television).”2 In 1998, a resolution presented to the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed adding the term “spiritual” to the organization’s familiar and oft-quoted definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not just the absence of disease or infirmity.”3 Although the proposal has never been officially adopted, it is now a well-documented fact that spirituality is an important component of health.4 Indeed, studies continue to demonstrate a clear link, mostly positive, between religion, spirituality and health.5,6 Professional organizations and accrediting bodies have recognized this trend, and addressing religious and spiritual needs is increasingly seen through an evidence-based lens as a crucial aspect of quality, comprehensive care.7,8 Both nursing and medical professions have acknowledged the importance of addressing the spiritual and religious needs of patients.1,9,10 As VanderWeele and colleagues note, a greater focus on spirituality in medicine could move patients and clinicians toward better patient-centered care and well-being.1

Although the majority of medical schools (>80%) offer spirituality courses, Bates-Cooper and colleagues found that only 21% of pharmacy schools offer spirituality training.11 Colleges of pharmacy as an entity have been slower to respond. However, the educational outcomes for Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) standards 2016 state “contemporary practice of pharmacy in a health care environment…demands interprofessional collaboration and professional accountability for holistic patient well-being” and for graduates to demonstrate self-awareness.12 As the role of the pharmacist shifts gradually from a product-oriented dispenser to an information-focused, collaborative member of the health care team, there may be more opportunities for addressing the role of R/S in direct patient care and for contributing to holistic patient well-being.13,14 As a result, pharmacy schools may need to provide courses, such as spirituality in health, that will help to meet these educational outcomes and perhaps increase student self-awareness.

There is a dearth of literature reporting on the R/S of pharmacy students.15-17 We hope that this study will add to the body of literature evaluating R/S and pharmacy students. Therefore, we conducted a pilot study aimed at characterizing the R/S of final year pharmacy students and examining the impact on performance in pharmacy school and their future practice as pharmacists. We hypothesize that R/S may change over time and that both will impact the academic performance of students and how they practice pharmacy.

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional multi-center study involving four schools. The study was conducted from March 23, 2015 to April 6, 2015. Participating universities were Shenandoah University (SU), University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS), University of Charleston (UC), and University of Maryland Eastern Shore (UMES). Three schools use a four-year curriculum and one school (UMES) uses a three-year curriculum. The institutional review boards of all four schools approved the study protocol.

Areas examined in the study included foundational R/S before and after starting pharmacy school, academic performance, and various practice issues including health and adherence, various dispensing and counseling practices, and comfort in conducting a spiritual assessment and prayer. A 36-question electronic survey was created using Survey Monkey (San Mateo, CA). The survey was sent to 308 students in their final year of pharmacy school by faculty researchers from each school. Socio-demographic data collected in the survey included gender, ethnicity, age, school attended, and geographic region where they spent most of their lives. Students were also asked to select one of the following as their religious affiliation: Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant (eg, Methodist, Lutheran, Baptist, Presbyterian) and non-Christian affiliations (eg, Jewish, Muslim), Atheist, Agnostic, and “Other.” Religiosity was assessed using the Duke University Religion Index (DUREL) (which measures organized religious activity (ORA) and non-organized religious activity (NORA) on a 1-6 scale and intrinsic religiosity (IR) on a 3-15 scale, with increasing religiosity as the score increases).18 The DUREL was used with permission. Students were asked “How spiritual do you consider yourself to be?” as a self-assessment of spirituality. Scoring was as follows: 1=not spiritual, 2=somewhat not spiritual, 3=unsure, 4=somewhat spiritual, 5=very spiritual. The impact of R/S on mental well-being while in pharmacy school and support of spiritual and religious beliefs by pharmacy school were also assessed. The impact of R/S on GPA was also assessed, using a self-reported range of GPAs (eg, <2.0, 2.5-2.99, etc.). The impact of R/S on professional practice issues was assessed including health and adherence, various dispensing and counseling practices, and conducting spiritual assessments.

Minitab 17 Statistical Software (State College, PA) was used for all quantitative analyses. Descriptive statistics were used for categorical data and reported as numbers and percentages. The median was used for non-normally distributed data. Non-parametric tests were used for the remaining analyses as the survey used Likert scale type questions that resulted in non-normally distributed data. The Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was used to compare involvement in ORA and NORA before and after entering pharmacy school. Responses for ORA, NORA, IR, and spirituality were compared against the participants’ grade point average using the Spearman Rho coefficient. For questions that used a Likert scale, strongly agree and agree were grouped as “agree” and responses for strongly disagree and disagree were grouped as “disagree.” Neutral responses remained separate.

RESULTS

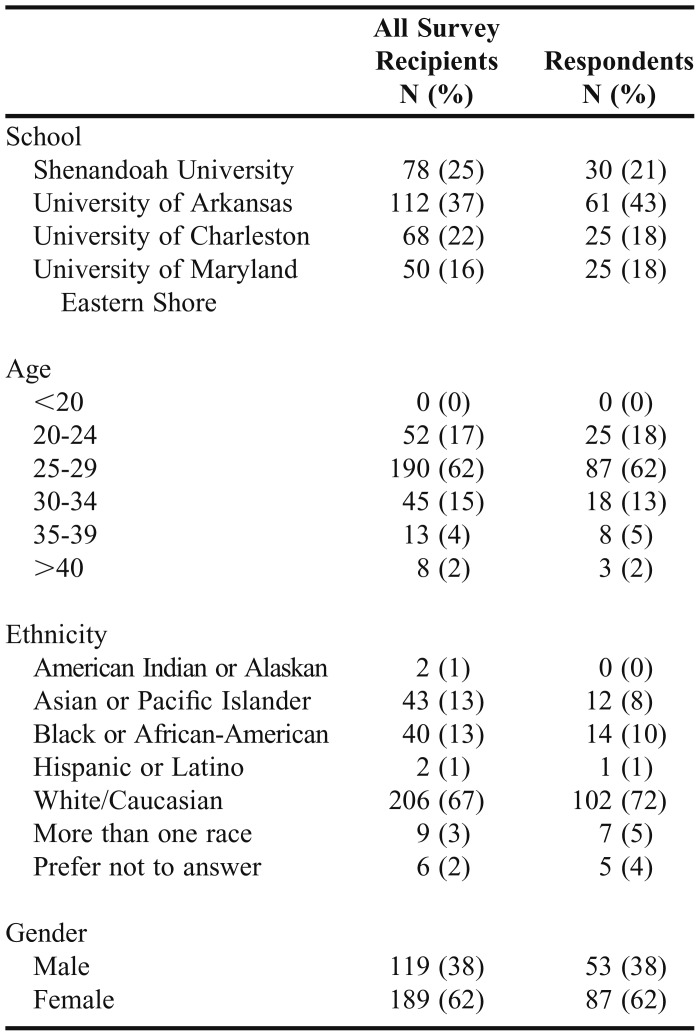

The survey was sent to 308 students in their final year of pharmacy school of which 141 (46%) responded. The number of students responding from each school is listed in Table 1 along with baseline demographics. Overall, these demographics were similar to the total population of students in their final year who received the survey at the four institutions as noted in Table 1. In terms of religious affiliation, 68% of the students identified themselves as Christian, followed by agnostic and atheist at 21%, and other/non-Christian at 11%. Additionally, 77% respondents spent most of their life in the southern region of the United States.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

Religiosity was calculated based on the median scores for responses to questions related to ORA, NORA, and IR. The median scores of the 134 students who answered the questions related to religiosity were 3.0, 2.5, and 12.0 for ORA, NORA, and IR respectively. The median spirituality score for these students was 4.0. Students were asked about ORA and NORA prior to starting pharmacy school and after starting pharmacy school. There was a statistically significant difference between ORA before students started pharmacy school and after (p<.001). However, no statistically significant difference was noted in NORA before and after starting pharmacy school (p=.25). Approximately 60% of students agreed that spirituality positively affected their emotional/mental well-being while in pharmacy school and 50% agreed that their pharmacy school supported their spiritual/religious beliefs. Median religiosity scores (ie, ORA, NORA, IR) and the spirituality score were higher in students who felt that spirituality positively affected their emotional/mental well-being while in pharmacy school compared to those who did not or were neutral (p<.001). The R/S scores were also higher for students who felt that their beliefs were supported by their school than those who did not or were neutral (p<.001). R/S did not correlate with students’ academic performance as measured by grade point average (GPA).

Students were also asked about dispensing and counseling practices. Students generally agreed that a patient’s spirituality or religious beliefs can affect their overall health (88%) and patient medication adherence (76%). Approximately 59% of students felt that it was their duty to inform patients about animal/human products in their medications that may interfere with their spiritual beliefs. Ninety-five percent of students were comfortable dispensing monthly traditional oral contraceptives and 96% would dispense the “morning after pill” if requested by a patient. Only 49% of students would work for a pharmacy that does not allow a pharmacist the “right to refuse to dispense” certain medications. The median IR for these students was lower than the IR for students who were neutral (28%) or disagreed (23%) with working for such a pharmacy (p=.01). Only 28% of students would dispense a pain medication as written or dispense the medication and alert the prescriber if they felt that the patient was taking it for purposes other than what was written. Approximately 63% of students would refuse to dispense and/or alert the prescriber.

Students were also asked questions about performing spiritual assessments and praying for patients. Only 12% of students were familiar with how to conduct a spiritual assessment on their patients in practice and only 19% felt that it is important to conduct a spiritual assessment of patients in practice. Approximately one-third of students (31%) had encountered a situation as a pharmacy student (on rotations or job) where a patient has asked them or other pharmacy staff to pray with them. More than half of the students surveyed (57%) would pray with patients when it is requested of them, while only 12% would routinely offer to pray with patients in their practice. Religiosity scores were lower for those who would not routinely pray for all patients (p<.001).

DISCUSSION

This study is the first multiple site, comprehensive study to date characterizing the R/S of final year pharmacy students and examining how R/S may affect key factors in pharmacy school and in future pharmacy practice.

The study surveyed pharmacy students at two public and two private schools of pharmacy. The age and gender of the pharmacy students in the study were fairly representative of the overall student population enrolled at the individual institutions and in ACPE-accredited institutions, but the students were geographically and ethnically less diverse than the pool of students enrolled at all accredited schools of pharmacy during the study period.19 The religious affiliation of the students was fairly representative of the US population based on data from the 2017 Pew Research Center that showed 77% of the US population identified themselves as Christian, 22% as unaffiliated (including atheist and agnostic), 8% as other, and 2% “don’t know” or “refuse to answer.”20

Higher education has been shown to affect students’ R/S. In a study conducted by University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), college students’ religiosity was shown to decrease while in school whereas spirituality increased.21 The present study gained insight as to the effect of pharmacy school on students’ foundational R/S and changes during pharmacy school, with participation in ORA significantly decreased during pharmacy school, whereas NORA did not significantly change. Possible reasons for this could be the time and academic commitment to be successful in graduate/professional schools with less time for organized activities or finding a place to worship. Non-organized religious activities, on the other hand, can be done privately requiring less time and planning. Students scored high on both intrinsic religiosity and spirituality in the final year of pharmacy school. No comparative data before beginning pharmacy school was collected for these parameters because intrinsic religiosity and spirituality are more subjective in nature and may be affected by recall bias. Due to the modest percentage (50%) of students who felt that their pharmacy school supported their spiritual/religious beliefs, pharmacy schools should find ways to support students’ religious and spiritual needs in the community and on campus, through student organizations, in recognizing religious observances, and in resources.

The effect of R/S on academic performance as measured by student-reported GPA showed no statistically significant correlations in this study, although this may have been subject to recall bias. This has been the focus of some thesis papers in various academic disciplines, but little research in health professional training has been published. George and colleagues found that spirituality played a role as a predictor of personal student success in liberal arts college students, although other factors such as time-management skills, intelligence, time spent studying, computer ownership, less time spent in passive leisure, and a healthy diet were predictors of GPA.22 This points to the need for future studies in this area particularly as it relates to the health professions.

The impact of R/S on various issues in pharmacy practice was examined. The majority of students felt that R/S could affect patients’ health and medication adherence. Understanding a patient’s spiritual history as it relates to medication adherence is important as demonstrated in the example from Muslim faith tradition during Ramadan.23 Since there is an increasing body of evidence in the literature correlating R/S to positive health outcomes,24 pharmacy schools should address the impact of a patient’s R/S on their health outcomes and medication adherence and make pharmacy students aware of the importance overall. Additionally, 59% of students felt that it was their duty regardless of their own R/S to make patients aware of animal/human products in medications that might interfere with spiritual beliefs. Daher and colleagues noted that pharmacists frequently encounter patients whose religious and spiritual beliefs affect their use of medications manufactured from animal sources and acknowledge that there is a greater need for pharmacist awareness in this area.25

The pharmacist's right to refuse to dispense certain medications such as contraceptives based on the pharmacist’s conscience has been an area of considerable debate. Davidson and colleagues found that religious affiliation significantly predicted pharmacists' willingness to dispense emergency contraception and medical abortifacients with nearly 6% of pharmacists indicating that they would refuse to dispense and refuse to transfer.26 Only 49% of students in the present study would work for a pharmacy that does not give them the “right to refuse to dispense” certain medications. The present study also demonstrated that students with higher intrinsic religiosity scores were less likely to work for a pharmacy that does not allow them the right to refuse to dispense.

Conducting a spiritual assessment of a patient in practice may play an important role in the holistic care of patients. Numerous tools including the FICA and HOPE questions can be used by clinicians when conducting a spiritual assessment.27,.28 The spiritual assessment supports patient care in many ways including: documenting a patient’s spiritual preferences, acknowledging the importance of faith traditions in treatment, supporting a patient’s spiritual traditions and communities in supporting wellness, strengthening the clinician-patient relationship.29 Only 19% of students agreed with the idea that it is important to conduct a spiritual assessment. Additionally, most pharmacy students were not familiar with conducting a spiritual assessment. Only one school included in this study offers a formal elective on spirituality. Cryder and colleagues found that pharmacy students who completed an elective course about spirituality felt significantly more confident in addressing spiritual concerns during patient encounters.15 Students should be made aware of the importance of conducting and how to perform a spiritual assessment. Perhaps modifications of the spiritual assessment tools could be made to make them more applicable to pharmacy such as asking questions like “Do you have any religious or spiritual beliefs that I need to be aware of as your pharmacist that might affect how you take your medications?”

The majority of students surveyed would not routinely pray with patients; however, 57% would pray if requested of them. Students who were less religious were less likely to offer prayer routinely. Since students may encounter patients asking for prayer in practice, proper training on how to best handle this request should be considered in pharmacy school. The use of a tool such as the Student Prayer Attitude Scale (SPAS) recently developed and validated by Pace and colleagues may be a valuable tool to further explore students’ attitudes toward prayer and to develop curricular elements to address prayer in practice.30

This study has several limitations. Although this was a multi-site study of 141 respondents, the response rate of 46% could have been improved. However, our study population is reflective of the larger student body at our schools as noted previously. The data mostly came from the southern geographic area and could have also influenced the response to survey questions. Additionally, our study included mostly Protestant students. While our institutions do have students with other religious affiliations, we do not know why they did not respond to the survey. We do recognize that this may introduce bias into our study. In addition, the patients’ religion was not specified in the questions asked. Since this was a pilot study, in future studies we will aim to obtain a larger sample that includes greater diversity, specifically in geographic and religious affiliation. Although the religiosity questions were validated, the spirituality assessment question was not and just consisted of one question. In addition, religion and spirituality are separate constructs and were surveyed separately in this study although they may be referred together in writing. The survey responses, including GPA, were self-reported by the participants and thus could have been affected by recall bias. This is particularly true as it relates to perceived changes of students’ R/S over time.

CONCLUSION

This study serves as a pilot study exploring the foundational R/S of pharmacy students and its impact on academic performance and professional practice development. Although R/S did not affect pharmacy student academic performance in this study, non-academic factors such as emotional/mental well-being, which are also important for student success, were positively affected by their R/S. The study also noted that ORA decreased while in pharmacy school whereas NORA did not significantly change. The majority of students felt that R/S could affect patients’ overall health/medication adherence and affect their future practice, although most lacked knowledge in spiritual assessment methods. Pharmacy schools should find ways to acknowledge and support R/S for pharmacy students and for promoting holistic patient well-being.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Shelly Schliesser, PharmD, for her assistance in planning the research project, Jayesh Parmar, PhD, and Arthur Harralson, PharmD, for providing guidance on the statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.VanderWeele TJ, Balboni TA, Koh HK. Health and spirituality. JAMA. 2017;318(6):519–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koenig HG, McCullough M, Larson D: Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

- 3.Nagase M. Does a multi-dimensional concept of health include spirituality? Analysis of Japan health science council’s discussions on WHO’s ‘definition of health’ (1998) Int J Appl Soc. 2012;2(6):71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical School Objectives Project. Report III: contemporary issues in medicine: communication in medicine (1999). https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/msop/. Accessed September 13, 2017.

- 5.Young C, Koopsen C. Spirituality, Health, and Healing: An Integrative Approach. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: the research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry. 2012;2012:Article 278730. doi: 10.5402/2012/278730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodge DR. A template for spiritual assessment: a review of the JCAHO requirements and guidelines for implementation. Soc Work. 2006;51(4):318–326. doi: 10.1093/sw/51.4.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borneman T, Koczywas M, Sun VC, Piper BF, Uman G, Ferrell B. Reducing patient barriers to pain and fatigue management. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(3):486–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomasso CS, Beltrame IL, Lucchetti G. Knowledge and attitudes of nursing professors and students concerning the interface between spirituality, religiosity and health. RLAE. 2011;19(5):1205–1213. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692011000500019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caldeira S, Carvalho EC, Vieira M. Spiritual distress-proposing a new definition and defining characteristics. Int J Nurs Knowl. 2013;24(2):77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-3095.2013.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bates-Cooper J, Brock TP, Ives TJ. The spiritual aspect of patient care in the curricula of colleges of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree, 2015. Standards 2016. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2017.

- 13.Campbell J, Blank K, Britton ML. Experiences with an elective in spirituality. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(1):Article 16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higginbotham AR, Marcy TR. Spiritual assessment: a new outlook on the pharmacist’s role. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(2):169–173. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cryder BT, Workman GM, Lee MM, Workman DE, Prerost FJ. Spirituality in the curriculum: impact on pharmacy students’ attitudes. 108th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, Orlando, Florida, July 14-17, 2007. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(3):Article 60. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacob B, White A, Shogbon A. First-year student pharmacists’ spirituality and perceptions regarding the role of spirituality in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(6):Article 108. doi: 10.5688/ajpe816108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown BK, Kleppe JT, Bierman SE. Spirituality and the Pharmacy Student. 108th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, Orlando, Florida. Am J Pharm Educ. 14-17, 2007;2007;71(3):Article 60. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koenig HG, Büssing A. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): A five-item measure for use in epidemiological studies. Religions. 2010;1(1):78–85. [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Student applications, enrollments and degrees conferred. Fall 2014 profile of pharmacy students. Enrollments. https://www.aacp.org/research/institutional-research/student-applications-enrollments-and-degrees-conferred. Accessed September 13, 2017.

- 20.Pew Research Center. More Americans now say they’re spiritual but not religious. Published September 6, 2017. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/06/more-americans-now-say-theyre-spiritual-but-not-religious/. Accessed September 13, 2017.

- 21. Spiritual changes in students during the undergraduate years: new longitudinal study shows growth in spiritual qualities from freshman to junior years. UCLA Higher Education Research Institute. http://spirituality.ucla.edu/docs/news/report_backup_dec07release_12.18.07.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2017.

- 22.George D, Dixon S, Stansal E, Gelb SL, Pheri T. Time diary and questionnaire assessment of factors associated with academic and personal success among university undergraduates. J Am Coll Health. 2008;56(6):706–715. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.6.706-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bragazzi NL, Briki W, Khabbache H, et al. Ramadan fasting and infectious diseases: a systematic review. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015;9(11):1186–1194. doi: 10.3855/jidc.5815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koenig HG, King DE, Carson VB. Handbook of Religion and Health. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daher M, Chaar B, Saini B. Impact of patients’ religious and spiritual beliefs in pharmacy: from the perspective of the pharmacist. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2015;11(1):e31–e41. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davidson LA, Pettis CT, Joiner AJ, Cook DM, Klugman CM. Religion and conscientious objection: a survey of pharmacists’ willingness to dispense medications. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(1):161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puchalski CM, Romer AL. Taking a spiritual history allows clinicians to understand patients more fully. J Palliat Med. 2000;3(1):129–137. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anandarajah G, Hight E. Spirituality and medical practice: Using the HOPE questions as a practical tool for spiritual assessment. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63(1):81–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saguil A, Phelps K. The spiritual assessment. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(6):546–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pace AC, Greene J, Deweese JE, et al. Measuring pharmacy student attitudes toward prayer: the student prayer attitude scale (SPAS) Christ Higher Educ. 2017;16(4):200–210. [Google Scholar]