Abstract

Objective. To describe a longitudinal evidence-based medicine (EBM) curriculum and to evaluate its impact on the attitudes and perceptions of student pharmacists toward EBM.

Methods. Western University of Health Sciences has had a structured, longitudinal, EBM curriculum for more than 10 years, spanning the first to third years, including the introductory experiential experiences. A survey was administered prior to the main EBM course and at the completion of the course at three time periods to assess student pharmacists’ attitudes and perceptions of EBM and interactive pedagogical methods. Student pharmacists at Western University of Health Sciences voluntarily participated in the self-administered survey. The three time periods examined included: directly after completion of the EBM course, after completion of the didactic curriculum, and after completion of the advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPE).

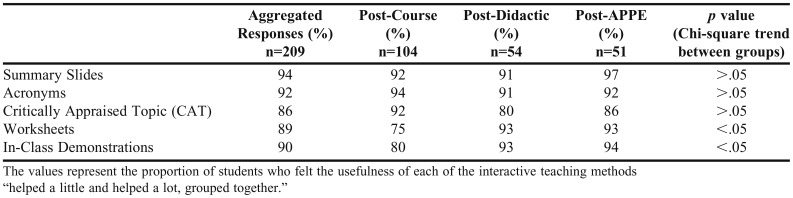

Results. The response rates were: pre-survey 94% and post-survey 53%. The three classes surveyed had similar baseline characteristics. Students’ perceptions of EBM skills and attitudes improved at all time periods post-course. Students felt strongly both before and after exposure to the EBM course and the longitudinal EBM curriculum about learning new EBM skills and that all pharmacists should have these skills. Significantly more students appreciated all the interactive pedagogical methods after APPE completion (>85% of students), as compared with over 74% of students directly after the EBM course, and over 79% of students after didactic completion.

Conclusion. The attitudes and perceptions of student pharmacists toward EBM improved after exposure to a longitudinal EBM curriculum.

Keywords: evidence-based medicine, pharmacy, student pharmacist, longitudinal curriculum, interactive learning methods

INTRODUCTION

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is a health care principle of incorporating knowledge gained from the best available research evidence and clinical expertise and applying this to individual patient preferences and circumstances.1 EBM, as originally defined by David Sackett, is “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients.”2 The steps of practicing EBM include formulating a focused clinical question from a patient's problem, searching the literature for relevant clinical evidence, critically appraising the evidence for its validity, applying evidence to the patient, and implementing the evidence in decision-making in clinical practice.

EBM has been included in undergraduate medical education for more than 20 years, and many EBM educational interventions for medical students have been published.3 Today, most medical schools include EBM in their curricula, although its implementation is not standardized.4-20 Several studies have examined the knowledge, skills, behaviors and/or attitudes of physicians and medical students, as well as in other health professions, such as nursing and physical therapy.4-6,9,10,12,14,15,19-22

Given the importance of EBM in informing decisions about medication use, EBM is critical to the practice of pharmacy. The EBM curriculum at Western University of Health Sciences, College of Pharmacy, Pomona, California has been in place for more than 10 years and has evolved from teaching EBM concepts to its students in a single, focused, 4-credit hour EBM course in the second year, to a longitudinal EBM curriculum that spans the first to the third years of the didactic courses, including the introductory pharmacy practice experiences (IPPE) (Table 1). The EBM curriculum uses the McMaster University framework of EBM core concepts using a 5-step process often referred to as “the 5A’s.” The first A refers to “Ask” where one develops a focused and answerable clinical question using a structured format known as PICO (patient, intervention, comparator, outcome). The second A refers to “Acquire” where one effectively and comprehensively obtains information that answers the clinical question. The third A refers to “Appraise” where one critically appraises the evidence collected for validity, importance, generalizability and applicability to answer the clinical question. The fourth A refers to “Apply” where one applies the information to a patient case or population of interest as identified in the PICO statement. The fifth A refers to “Assess” where one self-assesses their ability to practice the previous four steps and refines their skills and abilities. Recently, “Assess” was revised to “Act” where one conducts shared decision-making with patients, implements and monitors the plan, and self-assesses one’s performance.1

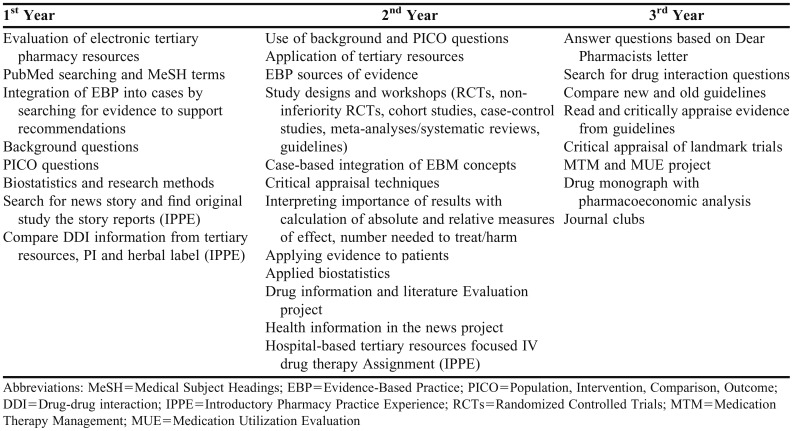

Table 1.

Longitudinal EBM Curriculum

During the first-year curriculum, students are taught about background and foreground questions, how to develop a focused foreground clinical question using the PICO method, and how to search various tertiary and EBM resources (eg, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Dynamed, and UpToDate), concepts which are applied in IPPE rotations. In addition, students are required to complete an intensive 1-credit hour biostatistics and research methods course at the completion of the first year focusing on understanding study design and interpreting biostatistics calculations.

During the second year, students are required to complete a mandatory 4-credit hours EBM-focused modular block course that further develops their foundational knowledge of asking clinical questions, searching EBM resources efficiently, examining validity of various study designs, interpreting study results for importance and applicability to patient cases, implementing their plan, and self-assessing their own performance.

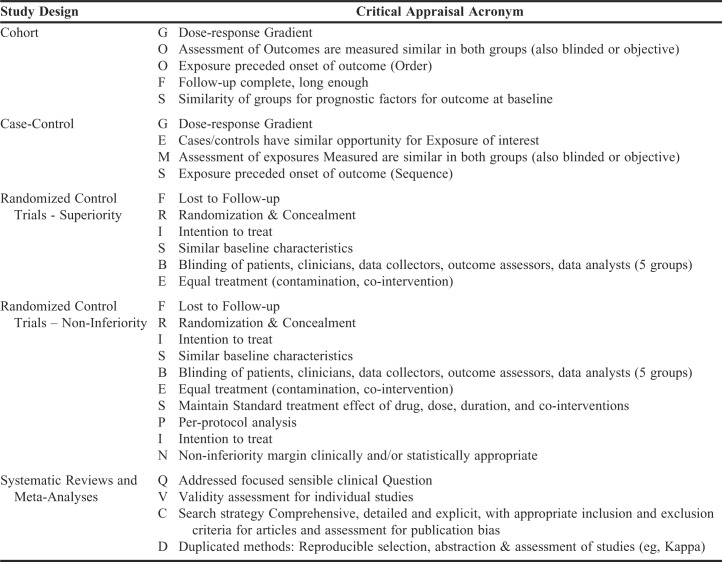

Interactive pedagogical teaching techniques are extensively used during the EBM course and continued in the second and third years throughout other didactic courses in EBM-focused projects and activities. These teaching techniques include creation of summary slides, use of acronyms that were developed to assist students with recalling major validity criteria to critically appraise for bias in different clinical study designs, creation of 1-page critically appraised topic (CAT) synopses of critical appraisal of studies, use of worksheets with instructions for appraising and applying evidence, and participation in in-class demonstrations. All these techniques focused on developing student learning and understanding of various study designs, criteria used to assess study validity, methods to generalize study results to patient cases, and methods to present one’s critical analysis of the information gathered and assessed. Appendix I lists samples of the acronyms used for the interactive teaching methods.

During the therapeutic courses of the second and third year, EBM concepts are applied through integration into case-based scenarios, case-based assignments, projects, journal clubs, and presentations, as well as a drug monograph and pharmacoeconomics project which have been previously described and evaluated (Table 1).33 The majority of courses in the second and third years included at least one structured EBM activity that was prepared by course and/or EBM faculty members. EBM is further incorporated within IPPE activities through exercises directed toward developing a focused clinical question to participation in activities such as journal clubs and applying clinical evidence to decision-making. Student understanding of EBM concepts is evaluated through graded quizzes and examinations, patient cases, projects and presentations. Throughout the longitudinal curriculum, the EBM concepts are intensified through repeated application and extension of prior concepts in subsequent student assignments and presentations.

The EBM curriculum at the college has continuously improved based upon literature and teaching techniques throughout this period and reflects the current Center for Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) recommendations for inclusion of EBM concepts within pharmacy education.23-25

Student pharmacists are the next generation of pharmacist practitioners, and their knowledge, attitudes and behaviors toward EBM need to be explored. Unlike other health professions, very little has been published about EBM in pharmacy practice.26,27 Of the published literature, student pharmacists’ perceptions of EBM concepts have only been assessed after exposure to either clinical rotations or two- to six-week didactic courses or traditional drug information courses.28-36 However, only one study examined the impact of a longitudinal EBM curriculum. The authors previously reported their experience with integrating EBM into a didactic pharmacoeconomics course assignment.37,38 Because little is known about the attitudes and perceptions of student pharmacists toward EBM, the objective of this study was to describe the longitudinal EBM curriculum and to evaluate these aspects among student pharmacists after exposure to an EBM course that uses interactive pedagogical methods, along with a longitudinal EBM curriculum.

METHODS

A survey was used to explore the attitudes, knowledge and behavior of student pharmacists toward EBM and how they change after being exposed to an EBM course and longitudinal EBM curriculum. Furthermore, the authors sought to characterize how an EBM course and longitudinal curriculum influence student pharmacists’ attitudes to better understand the EBM awareness of future pharmacist practitioners. The graduating classes of 2016 to 2018 student pharmacists at Western University of Health Sciences were invited to complete a voluntary pre-and post-survey. Survey participation was determined solely based on being a member of the PharmD Class of 2016, 2017 and 2018 and willingness to participate in the surveys. The subjects’ unwillingness to take the survey was the only exclusion criteria for the subject population.

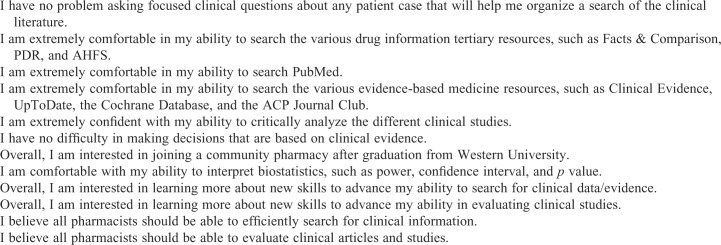

The pre-survey was administered prior to beginning the EBM course, on the first day of the second year. A post-survey was administered at three time periods: directly after completion of the EBM course in the P2 year (Class of 2018 – post-course), after completion of the didactic curriculum in the P3 year (Class of 2017 – post-didactic), and after completion of all the advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPE) in the P4 year (Class of 2016 – post-APPE). The post-survey was identical to the pre-survey except that the post-survey also included several questions assessing student attitudes toward the interactive pedagogical methods used during the course (Appendix 2).

Pre-survey responses were on a 5-point scale and post-survey responses were on a 4-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree, excluding an option for a “neutral” response. This variation in the scaled responses was made during transcribing the paper survey to the electronic survey format for the post-survey. For the analysis, the responses were further simplified to dichotomous responses of agree/disagree, with agree including agree and strongly agree, and disagree including disagree and strongly disagree. Furthermore, neutral responses in the pre-survey were split evenly, with half included among the “agree” and half among the “disagree” responses. A sensitivity analysis was conducted with the neutral responses classified as all positive and all negative. Chi-squared analysis was used to compare the pre-survey for each class and the cumulative pre-survey to each of the time periods to the post-surveys. This allowed for assessing potential differences in perceptions toward EBM curriculum at various time intervals after the initial EBM course. A p value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Western University of Heath Sciences.

RESULTS

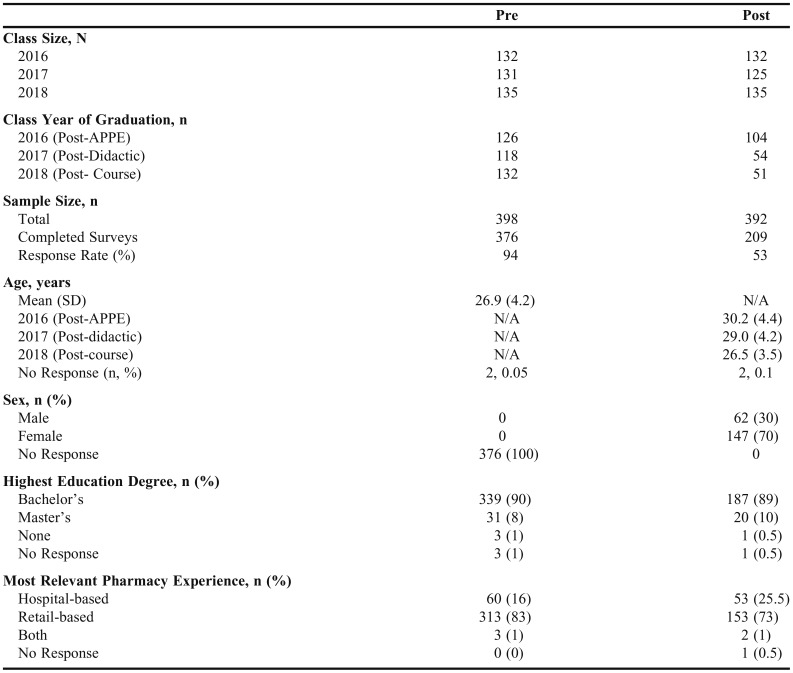

Pre-surveys were distributed to the Classes of 2016, 2017 and 2018 with class sizes of 132, 131, and 135, respectively. Students voluntarily participated in the pre-survey resulting in a response rate for the Class of 2016 of 95% (n=126), Class of 2017 of 89% (n=118), and Class of 2018 of 98% (n=132). The overall pre-survey response rate was 94% (376/398). Class sizes for Classes 2016 to 2018 at time of post-surveys distribution were 132, 125, and 135, respectively. Post-survey response rates for the Class of 2016 (post-APPE) was 79% (n=104), Class of 2017 was 43% (post-didactic) (n=54), and Class of 2018 (post-course) was 38% (n=51). The overall post-survey response rate was 53% (209/392). The three classes had similar baseline characteristics with an average age of 26.9 (4.2) Mean (SD) years for the pre-survey. Most students reported their highest educational degree as a bachelor’s degree (90% pre-survey and 89% post-survey) and most relevant pharmacy experience in the community setting (83% pre-survey and 73% post-survey) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study Population Baseline Characteristics Demographics

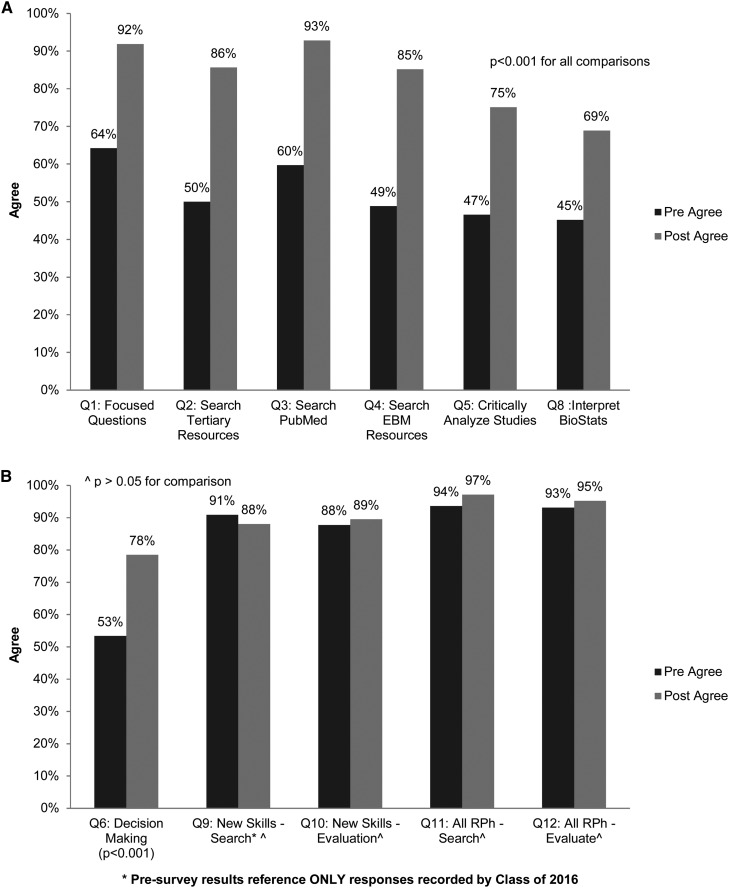

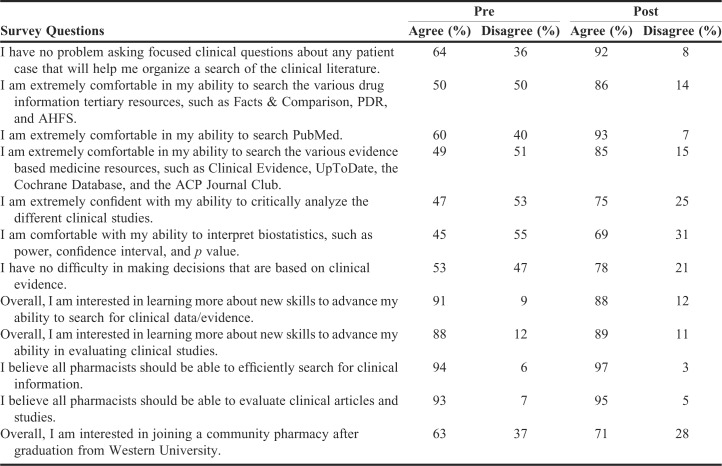

There were no differences in the pre-survey responses when comparing the three classes. (p>.05) Therefore, the pre-survey responses were combined for analysis. Similarly, there were no differences between the three time periods in the post-survey responses (p>.05), except for two questions that related to students’ perceived confidence to critically analyze clinical studies and ability to interpret biostatistics for which the class of 2018 (immediate post-course period) had a higher agreement (p<.001) (Figures 1a and 1b). Consequently, four comparisons of the pre- and post-surveys were conducted: all pre-/all post-survey responses, all pre-/post-course survey responses, all pre-/post-didactic survey responses, and all pre-/post-APPE survey responses. The sensitivity analysis with pre-survey neutral responses categorized as all positive or all neutral that was conducted suggests that the results were robust to the sensitivity analysis.

Figure 1.

(a) Pre-Post Survey Results – Steps 1-3 Ask, Acquire, and Appraise. (b) Pre-Post Survey Results – Steps 4-5 Apply and Assess.

The comparison of pre- to the aggregated post-survey responses for all three time periods showed significant improvement in students’ perceived ability in EBM skills and knowledge regarding all questions asked in the Ask, Acquire, Appraise, and Apply steps of EBM (p<.001). Students’ desire to further develop EBM skills and belief that all pharmacists should possess EBM skills remained high and did not differ from baseline (p>.05) (Figures 1a and 1b). The pre-survey vs post-APPE survey responses showed a similar pattern as the overall aggregate responses.

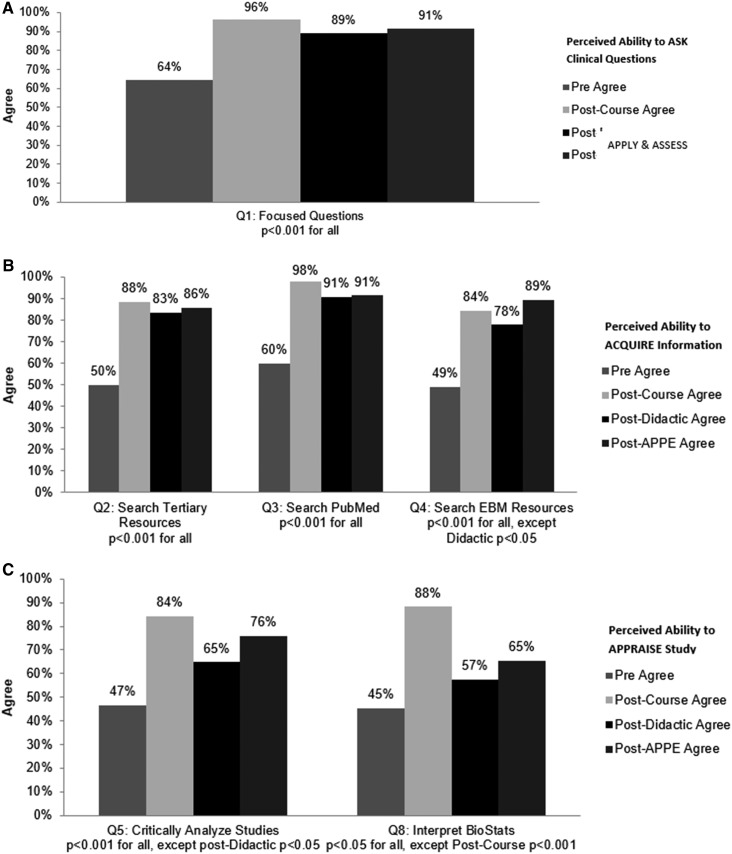

The immediate post-didactic survey responses were significantly higher compared with baseline regarding students’ perceived ability to Ask, Apply, and Acquire (search tertiary resources, PubMed, and EBM resources (p<.001)), and critically analyze study results (p<.05), while perceived ability to interpret biostatistics showed no difference (p>.05). Comparison of students’ desire to further develop EBM skills and belief that all pharmacists should possess EBM skills remained high in both time periods (p>.05) (Figures 2a, 2b, and 2c).

Figure 2.

(a) Survey Results Comparing Pre- to Each Post-Course Time Period – Step 1 (Ask); (b) Survey Results Comparing Pre- to Each Post-Course Time Period – Step 2 (Acquire); (c) Survey Results Comparing Pre- to Each Post-Course Time Period – Step 3 (Appraise).

The post-APPE survey responses were significantly higher compared with baseline regarding students’ perceived ability to Ask, Acquire and Appraise (p<.001), and Apply study results (p<.05). Comparison of students’ desire to further develop EBM skills and belief that all pharmacists should possess EBM skills remained high in both periods (p>.05) (Figures 2a, 2b, and 2c).

Included within the post-survey were questions that aimed to gauge the helpfulness of various interactive pedagogical techniques that were primarily employed during the EBM course, and to some extent throughout the P2 and P3 curriculum. These techniques included use of summary slides, EBM acronyms, critically appraised topics, worksheets with instructions, and in-class demonstrations. Based on the survey, 86% to 94% of students found these interactive learning techniques helpful (Table 3). There were no differences between time periods for the helpfulness of the summary slides, acronyms, and critically appraised topics (p>.05), while the usefulness of the worksheets with instructions and in-class demonstrations were rated more favorably in the post-didactic and post-APPE time period compared with the immediate post-course period (75% vs 93%) (p<.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Post-Survey Results Regarding the Usefulness of Interactive Pedagogical Methods

DISCUSSION

The objective of Western University of Health Sciences College of Pharmacy’s longitudinal EBM curriculum is to help students acquire the necessary knowledge, skills and attitudes of the 5-step EBM process in order to foster evidence-based practice. The curriculum develops student learning of EBM through utilization of various teaching methods and interactive learning tools and integration of EBM concepts within all didactic courses and clinical rotations. A survey of US and Canadian medical schools’ EBM curriculum demonstrate integration of EBM topics and learning over the span of four years through various learning settings and methods that are comparable to the curriculum within the Western University of Health Sciences College of Pharmacy.7 Through this study, the authors explored the impact of the longitudinal EBM curriculum on student pharmacists’ perceived attitudes, knowledge and behavior toward EBM. Consequently, student pharmacists’ attitudes, knowledge and behavior toward EBM improved after exposure to the EBM course, interactive pedagogical methods, and the longitudinal curriculum. Improvements in attitudes and knowledge, as well as the ability to apply evidence to clinical decision making, were demonstrated at each point of analysis. Furthermore, students continued to feel strongly that all pharmacists should possess the ability to search for clinical evidence and evaluate clinical studies.

The longitudinal curriculum and increasing level of EBM concept integration through the various assignments may account for the trends in students’ perceived confidence in EBM concepts. A study conducted at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy found similar results; students’ knowledge, perceptions and clinical application of EBM skills improved after exposure to a longitudinal EBM curriculum.37

No differences were noted in survey responses when comparing the three classes at baseline through the pre-survey responses. This lends to the idea that all students in the three classes felt similarly about their perceived confidence in EBM concepts after completion of the first year and prior to beginning the main EBM course. When comparing the baseline responses to the overall post-survey responses and to each time point, there were marked improvement in students’ perceptions of EBM skills and attitudes at all-time points after the course as compared to before the EBM course. Furthermore, both before and after exposure to the EBM course, didactic courses and the EBM curriculum, students felt strongly about learning new EBM skills and that all pharmacists should have these skills. A survey completed by practicing pharmacists in the community and hospital settings demonstrated that pharmacists, regardless of formal EBM training, had a positive attitude toward EBM and felt strongly that applying EBM skills in the clinical setting improves patient care.26 It is promising to see that both students and current practicing pharmacists agree upon the importance of possessing EBM skills.

A comparison of the post-survey responses among the three time periods resulted in no difference in their overall perceived ability in the Ask, Acquire, and Apply EBM skills to clinical decision-making, desire to learn new EBM skills, and belief that all pharmacists should have these skills. However, one notable difference was in the students’ ability to interpret biostatistics and to critically analyze study results (p<.05). The difference between the students’ ability to interpret biostatistics may be attributable to when and how biostatistics topics were taught. The one-week intensive biostatistics course was administered to the post-APPE group at the end of their first year; whereas, it was administered earlier, between the first and second semester of the P1 year for the post-didactic and post-course groups. Furthermore, biostatistics topics taught within the EBM course during the second year were instructed by different faculty for the post-APPE and post-didactic groups as compared with the post-course group, with the practical application of biostatistics concepts integrated to a greater degree for the post-course group.

The gradient noted between the three groups regarding their ability to apply clinical evidence to clinical decision-making may be attributable to the difference with in-class case-based decision-making versus practical application during APPE. The post-APPE group, having completed their APPE rotations would have had more opportunities to apply clinical evidence to decision-making; and therefore, they may have felt more confident in their ability. In contrast, the post-didactic group felt less confident in their ability as compared to the post-APPE group as they had only just completed the longitudinal EBM curriculum and were exposed to more complex patient cases and projects without the opportunity to apply their skills in the practice setting yet. The immediate post-course group may have felt the least confident in their ability due to having only completed the EBM course at the time of post-survey administration with fewer opportunities for practical application. These findings follow suit with studies that assessed the impact of an EBM course on APPE performance and confidence in EBM skills. In one study, student pharmacists were exposed to a 2-hour elective EBM course prior to completing APPEs in which students reported improved EBM skills and confidence in its application as compared to students who were not exposed to the course.28 In another study, students were exposed to a 4-week EBM specific APPE in which students reported improved skills, understanding and confidence in their EBM skills.29

Students were asked to assess the benefits of EBM teaching tools (acronyms, critical appraisal tools, summary slides, etc.) used during the course at the time point when the post-survey was administered. More students appreciated all the interactive pedagogical methods after completion of APPE vs only some methods after the course and didactics. All three groups found that the EBM acronyms, which were developed based on the criteria that should be met to determine the study’s validity, were universally helpful. These acronyms may be incorporated into summary slides and used in critically appraised topics, as shown in Appendix I, according to study design type.

This study has some limitations. First, there was a reduced response rate for the post-surveys for the post-didactic and post-course groups. Second, the pre-survey included the response of “neutral” as an option for students to select whereas the post-survey did not. Therefore, during the analysis, neutral responses were split evenly and included among the “agree” and “disagree” responses. This avoided the potential chance of over or underestimating the students’ perceived confidence in their EBM skills. Third, due to a clerical issue, survey questions gauging student interest in learning more about new EBM skills were not included in the pre-survey for the post-didactic and immediate post-course groups. Fourth, since the pre-survey was conducted on the first day of the P2 year, a true baseline prior to any exposure to EBM concepts in P1 was not done. However, since most EBM concepts are taught in P2 and P3 years, the baseline represents a reasonable estimation of students’ perceptions. Lastly, students who completed the post-survey may not remember all the different interactive learning techniques that were used during the EBM course, resulting in recall bias. However, this would mean the students’ bias would lean toward finding the teaching methods less useful.

CONCLUSION

The attitudes, knowledge and behavior of student pharmacists toward EBM improved after exposure to the EBM course, interactive pedagogical methods, and the longitudinal EBM curriculum. Comparison of post-surveys found a statistically significant difference in students’ perceived ability to critically analyze studies and interpret biostatistics. Over each period, slight improvements were seen in students’ perceived ability to apply evidence to decision-making. Students, from baseline as compared to each period post-EBM exposure, continued to feel strongly that all pharmacists should be able to search for clinical evidence and evaluate clinical studies.

Appendix 1. Example of Interactive Learning Tools – Mnemonics to Recall Key Validity Criteria for Common Study Designs

Appendix 2. Survey Questionnaire, Including Questions During All Periods Post-Course

Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Survey

Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements regarding your

CURRENT knowledge and skills related to searching and evaluating the medical literature.

Choose one per row with 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=agree, 4=strongly agree.

Please indicate to what extent the tools listed below influenced your understanding of evidence-based practice. Choose one per row with 1=confused me a lot, 2=confused me a little, 3=helped me a little, 4=helped me a lot

Please indicate your current age: _____Years Sex: _____Male _____Female

What is your highest educational degree: ____ Bachelor’s _____ Master’s _____ None

How would you describe your most relevant pharmacy experience? (Please check ONLY one)

_____ Hospital-based experience _____ Retail-based experience

Appendix 3. Survey Question Responses Per Response Category

REFERENCES

- 1.Guyatt G, Rennie D, Meade MO, Cook DJ. 2015. Users' Guides to the Medical Literature: A Manual for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice, 3rd Ed. American Medical Association: McGraw-Hill Education.

- 2.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JA, et al. What is evidence-based medicine? BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coomarasamy A, Khan KS. What is the evidence that postgraduate teaching in evidence-based medicine changes anything? a Systematic Review. BMJ. 2004;329:1–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7473.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloch RM, Swanson MS, et al. An extended evidence-based medicine curriculum for medical students. Acad Med. 1997;72:431–432. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199705000-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maggio LA, Tannery NH, et al. Evidence-based medicine training in undergraduate medical education: a review and critique of the literature published 2006-2011. Acad Med. July. 2013;88(7):1022–1028. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182951959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flores-Mateo G, Argimon JM. Evidence based practice in postgraduate healthcare education: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. 2007;7:119. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanco MA, Capello CF, Dorsch JL, et al. A survey study of evidence-based medicine training in US and Canadian medical schools. J Med Lib Assoc. 2014;102(3) doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.102.3.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis P, Green M, Kernan W. An evidence-based medicine curriculum for medical students: the art of asking focused clinical questions. Acad Med. 2000;75(5) doi: 10.1097/00001888-200005000-00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norman GR, Shannon SI. Effectiveness of instruction in critical appraisal (evidence-based medicine) skills: a critical appraisal. Can Med Assoc J. 1998;158(2):177–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liabsuetrakul T, Suntharasaj T, Tangtrakulwanich B, et al. Longitudinal analysis of integrating evidence-based medicine into a medical student curriculum. Fam Med. 2009;41(8):585–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green ML. Graduate medical education training in clinical epidemiology, critical appraisal, and evidence-based medicine: a critical review of curricula. Acad Med. 1999;74(6) doi: 10.1097/00001888-199906000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorsch JL, Aiyer MK, Meyer LE. Impact of an evidence-based medicine curriculum on medical students' attitudes and skills. J Med Libr Assoc. 2004;92(4):397–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aiyer M, Hemmer P, Meyer L, et al. Evidence-based medicine in internal medicine clerkships: a national survey. Southern Med J. 2002;95(12):1389–1395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.West CP, McDonald FS. Evaluation of a longitudinal medical school evidence-based medicine curriculum: a pilot study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1057–1059. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0625-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West CP, Jaeger TM, McDonald FS. Extended evaluation of a longitudinal medical school evidence-based medicine curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(6):611–615. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1642-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green ML. Evidence-based medicine training in graduate medical education: past, present and future. J Eval Clin Pract. 2000;6(2):121–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2000.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green ML, Ellis PJ. Impact of an evidence-based medicine curriculum based on adult learning theory. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:742–750. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meats E, Heneghan C, Crilly M, et al. Evidence-based medicine teaching in UK medical schools. Med Teacher. 2009;31(4):332–337. doi: 10.1080/01421590802572791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghali WA, Saitz R, Eskew AH, et al. Successful teaching in evidence-based medicine. Med Educ. 2000;34:18–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okoromah CAN, Adenuga AO, Lesi FEA. Evidence-based medicine curriculum: impact on medical students. Med Educ. 2006;40:459–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scholten-Peeters GG, Beekman-Evers MS, et al. Attitude, knowledge and behaviour towards evidence-based medicine of physical therapists, students, teachers and supervisors in the Netherlands: a survey. J Eval Clin Pract. August. 2013;19(4):598–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs SK, Rosenfeld PR, Haber J. Information literacy as the foundation for evidence-based practice in graduate nursing education: a curriculum-integrated approach. J Prof Nurs. 2003;19(5):320–328. doi: 10.1016/s8755-7223(03)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Center for Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) educational outcomes. 2004. http://www.aacp.org/resouces/education/documents/CAPE2004.pdf Accessed February 11, 2015.

- 24.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. http://www.acpeaccredit.org/pdf/ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.pdf Accessed February 11, 2015.

- 25.Bruce SP, Bower A, Hak E, Schwartz AH. Utilization of the Center of Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education educational outcomes, revised version 2004: Report of the 2005 American College of Clinical Pharmacy Educational Affairs Committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(4):Article 79. doi: 10.5688/aj700479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burkiewicz JS, Zgarrick DP. Evidence-based practice by pharmacists: utilization and barriers. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1214–1219. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson GM, Jackson SL, et al. Attitudes of Australian pharmacists towards practice-based research. J Clin Pharm Ther. August. 2009;34(4):397–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bookstaver PB, Rudisill CN, Bickley AR, et al. An evidence-based medicine elective course to improve student performance in advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(1):Article 9. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neill KK, Johnson JT. An advanced pharmacy practice experience in application of evidence-based policy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(7):Article 133. doi: 10.5688/ajpe767133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burkiewicz JS, Komperda KE. An elective course on landmark trials to improve pharmacy students' literature evaluation and therapeutic application skills. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(2):Article 31. doi: 10.5688/aj730231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arif SA, Gim S, Nogid A, Shah B. Journal clubs during advanced pharmacy practice experiences to teach literature-evaluation skills. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(5):Article 88. doi: 10.5688/ajpe76588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Timpe EM, Motl SE, Eichner SF. Weekly active-learning activities in a drug information and literature evaluation course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(3):Article 52. doi: 10.5688/aj700352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips JA, Gabay MP, Ficzere C, et al. Curriculum and instructional methods for drug information, literature evaluation, and biostatistics: Survey of US pharmacy schools. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:793–801. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Sullivan TA, Phillips J, Demaris K. Medical literature evaluation education at US schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(1):Article 5. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dawn S, Dominguez KD, Troutman WG, et al. Instructional scaffolding to improve students' skills in evaluating clinical literature. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(4):Article 62. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harpe SE, Phipps LB. Evaluating student perceptions of a learner-centered drug literature evaluation course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(6):Article 135. doi: 10.5688/aj7206135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin BA, Kraus CK, Kim SY. Longitudinal teaching of evidence-based decision making. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(10):Article 197. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7610197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Law AV, Jackevicius CA, Bounthavong M. A monograph assignment as an integrative application of evidence-based medicine and phamacoeconomic principles. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(1):Article 1. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]