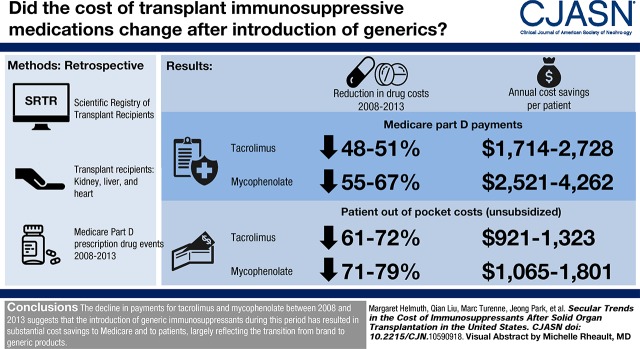

Visual Abstract

Keywords: transplantation, kidney; liver failure; heart disease; end-stage renal disease; Mycophenolic Acid; tacrolimus; Medicare Part D; Immunosuppressive Agents; Health Expenditures; Cost Savings; Insurance Carriers; Transplant Recipients; Linear Models; Drugs, Generic; Prescription Drugs; Heart Transplantation

Abstract

Background and objectives

Immunosuppressive medications are critical for maintenance of graft function in transplant recipients but can represent a substantial financial burden to patients and their insurance carriers.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

To determine whether availability of generic immunosuppressive medications starting in 2009 may have alleviated some of that burden, we used Medicare Part D prescription drug events between 2008 and 2013 to estimate the average annualized per-patient payments made by patients and Medicare in a large national sample of kidney, liver, and heart transplant recipients. Repeated measures linear regression was used to determine changes in payments over the study period.

Results

Medicare Part D payments for two commonly used immunosuppressive medications, tacrolimus and mycophenolic acid (including mycophenolate mofetil and mycophenolate sodium), decreased overall by 48%–67% across organs and drugs from 2008 to 2013, reflecting decreasing payments for brand and generic tacrolimus (21%–54%), and generic mycophenolate (72%–74%). Low-income subsidy payments, which are additional payments made under Medicare Part D, also decreased during the study period. Out-of-pocket payments by patients who did not receive the low-income subsidy decreased by more than those who did receive the low-income subsidy (63%–79% versus 24%–44%).

Conclusions

The decline in payments by Medicare Part D and by transplant recipients for tacrolimus and mycophenolate between 2008 and 2013 suggests that the introduction of generic immunosuppressants during this period has resulted in substantial cost savings to Medicare and to patients, largely reflecting the transition from brand to generic products.

Introduction

Solid organ transplantation is a life-saving and cost-effective (1,2) treatment for patients with end-stage organ failure. In order to maintain a functioning graft, however, transplant recipients must remain on immunosuppressive medications for the rest of their lives. In 2000, the yearly average cost of standard maintenance immunosuppressive medication regimens for kidney transplant recipients was estimated to be between $10,000 and $14,000 (3). Since then, generic versions of some commonly prescribed immunosuppressive medications, including tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and mycophenolate sodium, have become available (4). The first generic versions of mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2008 and 2009, respectively (5,6). Use of generic versions of these immunosuppressive medications increased rapidly after their initial market entry; by 2013, 80%–90% of prescriptions covered under Medicare Part D for tacrolimus or mycophenolate mofetil were dispensed as generics (7). A generic version of mycophenolate sodium, frequently prescribed as an alternative to mycophenolate mofetil, was approved in 2012. Generic substitution for brand-name products is thought to reduce pharmaceutic expenditures while delivering comparable therapeutic benefit (8).

Medicare pays for 60%, 30%, and 39% of kidney, liver, and heart transplants, respectively (9). Medicare also covers immunosuppressive medications for eligible kidney transplant recipients for 3 years after transplant via Part B. Payment beyond that time and for all other organs requires that patients qualify for Medicare coverage on the basis of age or disability. Transplant recipients with other sources of coverage may have their immunosuppressive medications covered by Medicare Part D when they become eligible. Coverage for immunosuppressive medications for the duration of transplant function has been recommended; however, such a policy has gained little traction in the United States (3,10).

Generic immunosuppressive medications have the potential to reduce costs for transplant recipients, resulting in a wide range of social and economic benefits for patients and the United States health care system. Despite the expected benefits of more affordable immunosuppressive medications, little information is available regarding the actual financial effect of substitution with generic immunosuppressive medications (11). The objective of our study was to assess potential cost savings from substitution with generic immunosuppressive medications for organ transplant recipients and the Medicare Part D program. We examined the trajectories of per-patient payments for brand-name and generic tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil and brand-name mycophenolate sodium in a large national sample over a 6-year period, during which generic versions of these drugs were first introduced.

Materials and Methods

Data and Study Sample

This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The SRTR includes data on all donors, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States, submitted by members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), US Department of Health and Human Services, provides oversight to OPTN and SRTR contractor activities.

SRTR data were used to identify all United States kidney, liver, and heart recipients transplanted between 1987 and 2013. The SRTR data set was linked to Medicare Part D prescription drug event data to identify immunosuppressive medication prescriptions filled between 2008 and 2013 for transplant recipients whose immunosuppressive medications were covered through a Part D plan. This study period reflects years shortly before and after generic versions of the most common immunosuppressive medications became available. The linked data set was used to estimate transplant recipients’ out-of-pocket payments, Medicare Part D prescription drug plan payments, and Medicare Part D low-income subsidy payments for generic and brand-name oral immunosuppressive medications dispensed after heart, liver, or kidney transplantation.

Patients were eligible for analysis if they received a single-organ transplant and maintained graft function for at least 30 days after transplantation; had graft function on January 1, 2008 for those transplanted before 2008; and had at least one post-transplant Part D prescription drug event during the study period for tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, or mycophenolate sodium. Patients with repeat transplants were allowed to contribute multiple transplants to the analysis if the above criteria were met for each transplant. Prescription drug events for immunosuppressive medications reported between graft failure and repeat transplantation were excluded from analysis. This study was deemed exempt from Institutional Review Board review.

Statistical Analyses

We calculated the average annualized amount paid by transplant recipients, Medicare Part D plans, and the Medicare Part D low-income subsidy program for brand-name and generic tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil and brand-name mycophenolate sodium. The FDA approved generic mycophenolate sodium in August of 2012 (not observed in our data; only brand-name mycophenolate sodium data are presented in these analyses). An overall average annualized per-patient payment amount that included brand-name and generic products was calculated to show overall payment trends during the study period. Because mycophenolate sodium is often used as a substitute for mycophenolate mofetil, and we only observed brand-name mycophenolate sodium use, the overall average per-patient payment amounts for mycophenolate mofetil and mycophenolate sodium were combined into one estimate for any mycophenolic acid product.

Per-patient payment amounts were annualized to a full calendar year to account for patients with partial years of prescription drug data, i.e., patients transplanted or enrolled/dis-enrolled from Medicare Part D during a given year, or patients with periods of missing prescription drug events. Annualized per-patient payment amounts were calculated as the total amount paid during the year, divided by the proportion of days with immunosuppressive medication prescription coverage during that year. Average annualized per-patient payment amounts were calculated by averaging all patients’ annualized per-patient payment amounts, across each year, weighted by the proportion of days each patient had immunosuppressive medication prescription coverage. The proportion of days with immunosuppressive medication prescription coverage was calculated using the total number of days’ supply reported for each recipient’s prescription drug events for each specific immunosuppressive medication in a year, divided by the number of days in that year. Many transplant recipients had multiple prescriptions for the same immunosuppressive medication, with overlapping days of supply covering the same period of time. Medicare Part D prescription drug event data do not include information on dose prescribed; in these cases, days with overlapping immunosuppressive medication prescriptions of the same medication were only counted once. The average annualized per-patient payment amount thus represents an estimate of the amount that would be paid by a patient, by a Part D plan, or in the form of a low-income subsidy, if the patient had been transplanted, enrolled in Medicare, and filled immunosuppressive medication prescriptions covered by Part D for an entire year.

Overall, brand-name, and generic average annualized per-patient payment amounts were calculated separately for each organ and immunosuppressive medication for each year from 2008 to 2013. Patient and low-income subsidy payment amounts were reported separately by patient low-income subsidy status. All payment amounts were adjusted for price inflation using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, and are expressed in 2013 dollars (12).

To determine whether the change in overall average annualized per-patient payments from the start (year 2008) to the end (year 2013) of our study period was statistically significant, we used repeated measures linear regression with annualized payments as the outcome and calendar year as a categorical variable and reported P values from pairwise comparisons between years the 2008 and 2013. Regression was done separately by organ type and immunosuppressive medication. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

There were 27,625 kidney, 15,882 liver, and 6851 heart transplant recipients enrolled in Part D who were eligible for this study, accounting for 8%, 14%, and 12% of all kidney, liver, and heart transplant recipients since 1987, respectively. In all three cohorts, recipients were predominantly male, white, and aged 50–64 years (Table 1). Among kidney transplant recipients, 38% had living donor transplants, compared with only 3% of liver recipients. Previous transplants of the same organ type were reported for 11%, 6%, and 2% of kidney, liver, and heart transplant recipients, respectively. Compared with the SRTR transplant population not included in our Medicare Part D data set, but otherwise eligible for study inclusion, patients in our study sample were older and more likely to be transplanted before 2010 (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for transplant recipients with tacrolimus or mycophenolic acid prescription drug events through Medicare Part D during 2008–2013, by organ type

| Variable | Kidney | Liver | Heart |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of transplant recipients | 27,625 | 15,882 | 6851 |

| Number of transplants | 27,736 | 15,958 | 6874 |

| Yr of transplant | |||

| 1987–1990 | 223 (1%) | 216 (1%) | 124 (2%) |

| 1991–1995 | 1007 (4%) | 1003 (6%) | 539 (8%) |

| 1996–2000 | 4146 (15%) | 2637 (17%) | 1341 (20%) |

| 2001–2005 | 8560 (31%) | 4643 (29%) | 1949 (28%) |

| 2006–2010 | 10,963 (40%) | 5753 (36%) | 2266 (33%) |

| 2011–2013 | 2726 (10%) | 1630 (10%) | 632 (9%) |

| Male | 15,787 (57%) | 9638 (61%) | 4980 (73%) |

| Racea | |||

| White | 14,382 (52%) | 11,409 (72%) | 4954 (72%) |

| Black | 6869 (25%) | 1345 (9%) | 1150 (17%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 4417 (16%) | 2308 (15%) | 551 (8%) |

| Asian/Other | 1956 (7%) | 815 (5%) | 196 (3%) |

| Age at transplant, yr | |||

| Median (IQR) | 52 (39–61) | 54 (48–60) | 54 (45–60) |

| <18 | 1023 (4%) | 145 (1%) | 107 (2%) |

| 18–34 | 3979 (14%) | 824 (5%) | 712 (10%) |

| 35–49 | 7002 (25%) | 3861 (24%) | 1577 (23%) |

| 50–64 | 11,762 (43%) | 9779 (62%) | 3919 (57%) |

| 65+ | 3859 (14%) | 1273 (8%) | 536 (8%) |

| Age at first Medicare Part D claim during 2008–2013, yr | |||

| Median (IQR) | 58 (45–66) | 60 (53–65) | 62 (50–66) |

| <18 | 557 (2%) | 3 (0.0%) | 5 (0.1%) |

| 18–34 | 2891 (11%) | 647 (4%) | 597 (9%) |

| 35–49 | 5620 (20%) | 1894 (12%) | 989 (14%) |

| 50–64 | 9618 (35%) | 7992 (50%) | 2630 (38%) |

| 65+ | 8939 (32%) | 5346 (34%) | 2630 (38%) |

| BMIa | |||

| <18.5 | 1071 (4%) | 372 (3%) | 263 (4%) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 8519 (35%) | 4375 (30%) | 2429 (37%) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 7773 (32%) | 5182 (35%) | 2400 (37%) |

| ≥30 | 6870 (28%) | 4810 (33%) | 1404 (22%) |

| Donor typea | |||

| Donation after circulatory death | 1410 (5%) | 474 (3%) | |

| Donation after brain death | 15,446 (57%) | 14,186 (93%) | |

| Living related donation | 6933 (26%) | 382 (3%) | |

| Living unrelated donation | 3319 (12%) | 140 (1%) | |

| Previous transplant of the same organ type | 3010 (11%) | 884 (6%) | 145 (2%) |

| Number of human leukocyte antigen mismatches: 1–6 versus 0a | 23,865 (88%) | ||

| Recipient diagnosis (kidney)a | |||

| Diabetes | 6168 (23%) | ||

| Hypertension | 6140 (22%) | ||

| GN | 6943 (25%) | ||

| Cystic kidney disease | 2410 (9%) | ||

| Other | 5728 (21%) | ||

| Recipient diagnosis (liver)b | |||

| Acute hepatic necrosis | 933 (6%) | ||

| Cholestatic liver disease/cirrhosis | 2011 (13%) | ||

| Noncholestatic cirrhosis | 7933 (50%) | ||

| Hepatitis C | 6408 (40%) | ||

| Malignant neoplasm | 2812 (18%) | ||

| Metabolic disease | 584 (4%) | ||

| Other liver disease | 2307 (15%) | ||

| Recipient diagnosis (heart)a | |||

| Coronary artery disease | 2925 (43%) | ||

| Cardiomyopathy | 3416 (50%) | ||

| Congenital/valvular/other | 501 (7%) | ||

| Ventricular assist device (heart)a | 1746 (38%) |

Data displayed as n (%) unless otherwise noted. IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index.

Missing for at most 5% of patients, except BMI missing for 7% and 12% of Medicare Part D liver and kidney patients, respectively, and ventricular assist device missing for 33% of Medicare Part D heart patients.

Diagnoses for liver transplant recipients are on the basis of primary and secondary diagnoses and are not mutually exclusive. Each liver recipient can have one or two diagnoses; therefore, percentages will not sum to 100%.

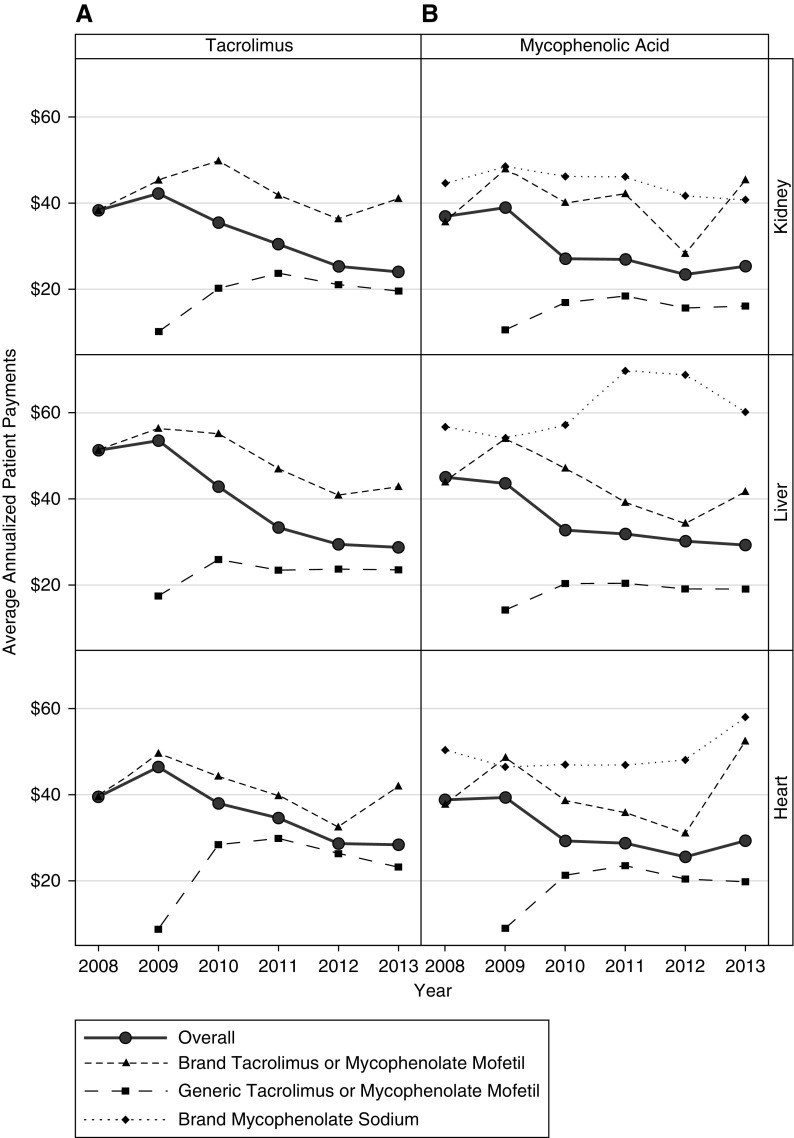

Medicare Payments

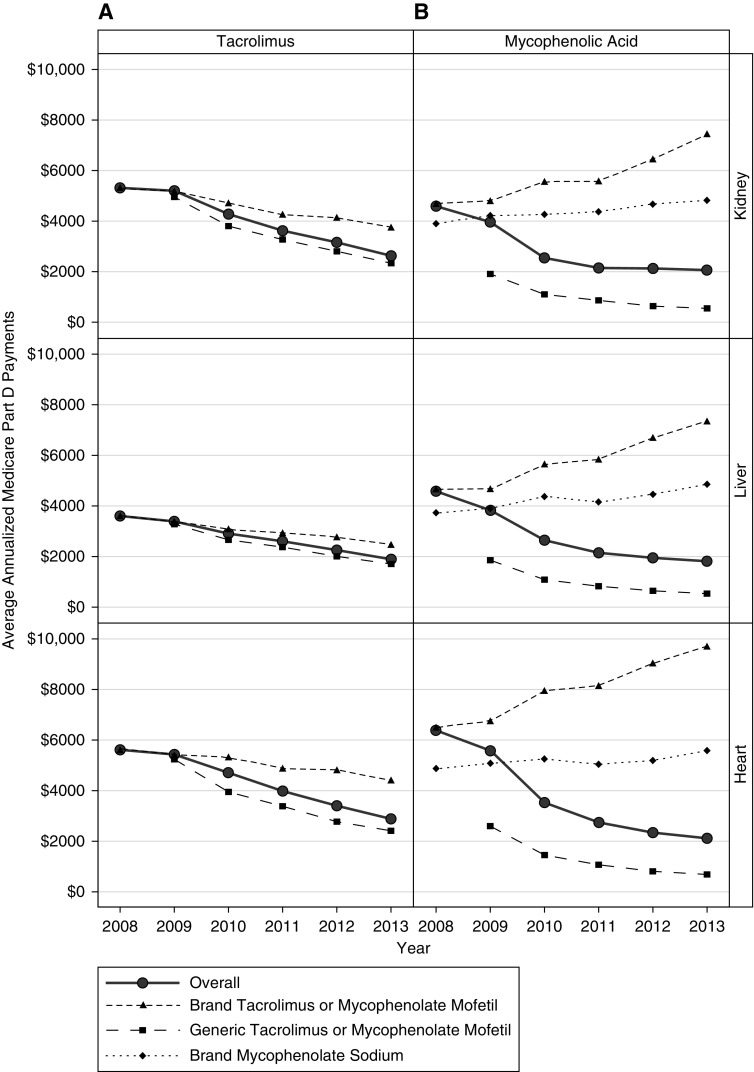

The overall average annualized per-patient Medicare Part D payments for tacrolimus decreased by 51% (P<0.001), 48% (P<0.001), and 49% (P<0.001) between 2008 and 2013 for kidney, liver, and heart transplant recipients, respectively (Figure 1A, Supplemental Table 2), representing cost savings to Medicare of $1714 to $2728 per patient. Similar decreases were observed for overall average annualized per-patient Medicare Part D payments for mycophenolic acid (55% P<0.001 [$2521], 61% P<0.001 [$2771], and 67% P<0.001 [$4262] for kidney, liver, and heart recipients, respectively; Figure 1B). The decline in overall average per-patient payments largely reflects a shift toward increased generic use. Declines in the average overall per-patient Medicare Part D payments were observed for brand-name (29%, 32%, and 21% for kidney, liver, and heart recipients between 2008 and 2013, respectively) and generic tacrolimus (53%, 48%, and 54% for kidney, liver, and heart recipients between 2009 and 2013, respectively). Unlike for tacrolimus, overall per-patient payment amounts for Medicare Part D beneficiaries for brand-name mycophenolate mofetil and brand-name mycophenolate sodium increased over time for all organs. From 2008 to 2013, average overall brand-name mycophenolate mofetil per-patient payments for Part D beneficiaries increased by 59%, 57%, and 49% for kidney, liver, and heart recipients, respectively; average overall brand-name mycophenolate sodium per-patient payments increased by 23%, 30%, and 15%, respectively. By contrast, average overall per-patient payments for Medicare Part D beneficiaries for generic mycophenolate mofetil decreased by 72%, 72%, and 74% between 2009 and 2013 for kidney, liver, and heart recipients, respectively.

Figure 1.

Trends in Medicare Part D payments from 2008–2013. Average annualized Medicare Part D plan payments (2013 US dollars) for overall, brand-name, and generic (A) tacrolimus and (B) mycophenolic acid by organ type.

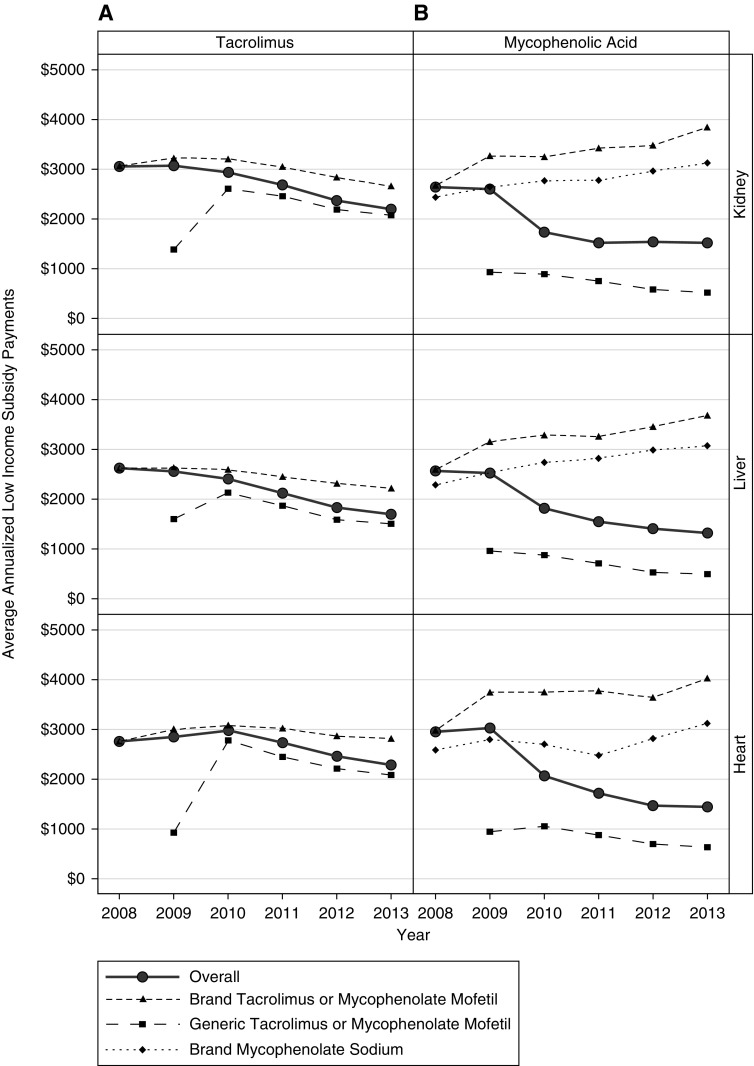

Overall, per-patient Part D low-income subsidy payment amounts for tacrolimus and mycophenolic acid decreased between 2008 and 2013. Per-patient Part D low-income subsidy payment amounts for brand-name tacrolimus and generic mycophenolate mofetil also decreased between 2008 and 2013; the brand-name mycophenolate mofetil and brand-name mycophenolate sodium Part D low-income subsidy payments increased during this time period. Payment amounts for generic tacrolimus increased from 2009 to 2010, likely due to the low proportion of days covered in the first year of its introduction (average 16%), then decreased from 2010 to 2013 (Figure 2, Supplemental Table 3).

Figure 2.

Trends in low-income subsidy payments from 2008–2013. Average annualized payments (2013 US dollars) by the Medicare Part D low-income subsidy program for overall, brand-name, and generic (A) tacrolimus and (B) mycophenolic acid by organ type. Patients not receiving the low-income subsidy were excluded from this analysis.

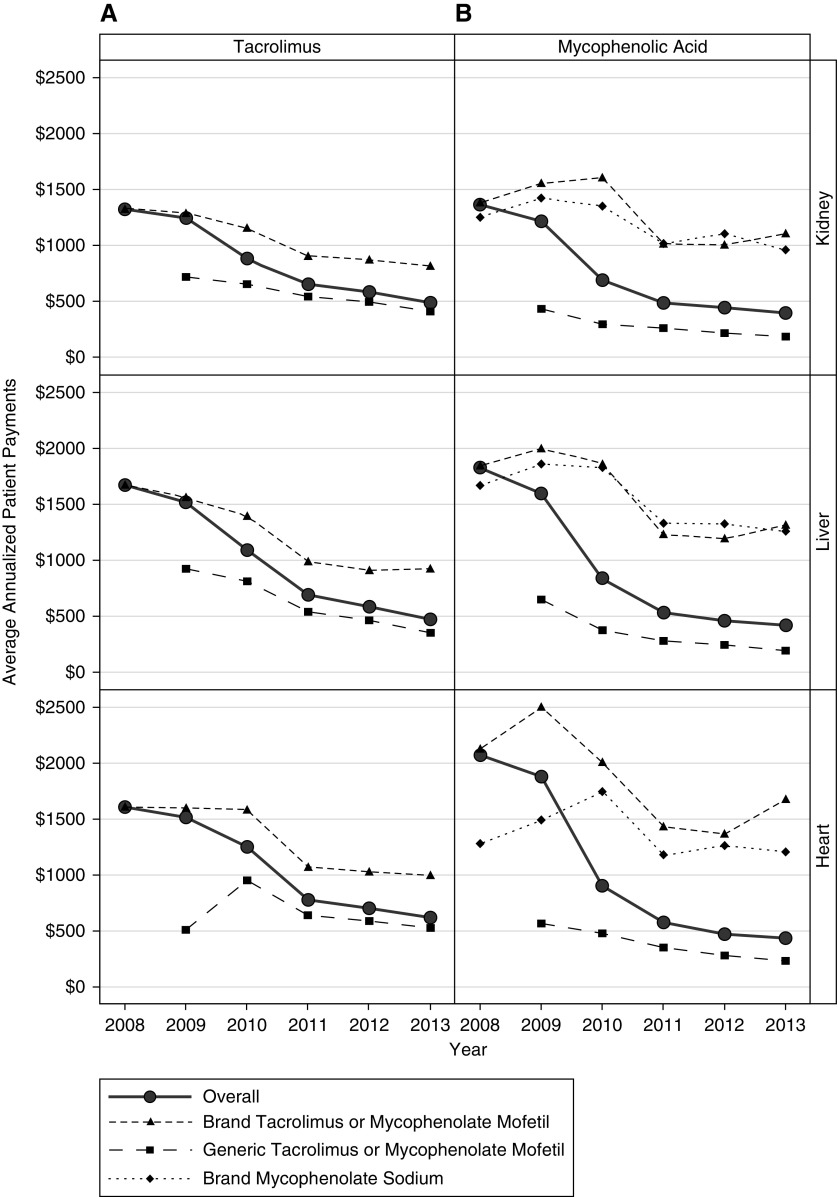

Patient Payments

The proportion of patients not receiving the low-income subsidy ranged from 37% to 58%, 45% to 58%, and 46% to 63% for kidney, liver, and heart patients, across drugs and years. The overall average annualized out-of-pocket payments for tacrolimus by transplant recipients with Part D who did not receive the low-income subsidy decreased by 63% ($921, P<0.001), 72% ($1,323, P<0.001), and 61% ($1,086, P<0.001) between 2008 and 2013 for kidney, liver, and heart transplant recipients, respectively (Figure 3A, Supplemental Table 4). As with the trend in average overall Medicare Part D per-patient payment amounts for tacrolimus, patient out-of-pocket payments for tacrolimus decreased over the study period for brand-name and generic immunosuppressive medications. The percentage decreases in patient payments for all organs were greater than those observed for Part D payments. Annualized averages for generic tacrolimus for 2009 represent a relatively low proportion of days covered (average 16%), given that generic tacrolimus was not approved until August of 2009. Although overall annualized out-of-pocket per-patient payments for tacrolimus for patients receiving the low-income subsidy were low (ranging from $24 to $53 per year across organs and across years) compared with those not receiving the low-income subsidy, they also decreased during the study period, by 37% (P<0.001), 44% (P<0.001), and 28% (P=0.01) for kidney, liver, and heart recipients, respectively (Figure 4A, Supplemental Table 5).

Figure 3.

Trends in non-low-income subsidy patient payments from 2008–2013. Average annualized out-of-pocket payments (2013 US dollars) by patients not receiving the low-income subsidy for overall, brand-name, and generic (A) tacrolimus and (B) mycophenolic acid by organ type. Patients receiving the low-income subsidy were excluded from this analysis.

Figure 4.

Trends in low-income subsidy patient payments from 2008–2013. Average annualized out-of-pocket payments (2013 US dollars) by patients receiving the low-income subsidy for overall, brand-name, and generic (A) tacrolimus and (B) mycophenolic acid by organ type. Patients not receiving the low-income subsidy were excluded from this analysis.

The average annualized out-of-pocket payments by patients with mycophenolic acid prescriptions decreased from 2008 to 2013 for all organs (Figure 3B). Unlike tacrolimus, which showed a steady decline over the study period, the overall out-of-pocket payment amounts for patients not receiving the low-income subsidy decreased more rapidly between 2008 and 2010, then more slowly between 2011 and 2013, with overall decreases of 71% ($1,065, P<0.001), 77% ($1,555, P<0.001), and 79% ($1,801, P<0.001) for kidney, liver, and heart recipients, respectively. Per-patient payments for generic mycophenolate mofetil decreased 58%, 71%, and 59% for kidney, liver, and heart transplant recipients, respectively, between 2009 and 2013. Between 2008 and 2013, per-patient payments for brand-name mycophenolate mofetil decreased by 20%, 29%, and 21%; brand-name per-patient payments for mycophenolate sodium decreased by 23%, 25%, and 6%. Although patients receiving the low-income subsidy made relatively low out-of-pocket payments for mycophenolic acid (ranging from $23 to $45 per year), their payments also decreased by 31% (P<0.001), 35% (P<0.001), and 24% (P=0.06) between 2008 and 2013 for kidney, liver, and heart recipients, respectively (Figure 4B).

Discussion

Overall, annual payments by patients for tacrolimus and mycophenolic acid decreased from 2008 to 2013 for kidney, liver, and heart transplant recipients, and for the Medicare Part D program. These trends are largely explained by substitution of generic immunosuppressive medications after the introduction of generic products in 2008 and 2009. Across organs, the percentage of prescription drug events for generic tacrolimus increased from 10% to 11% in 2009 to 76% to 80% in 2013; generic mycophenolate mofetil increased from 28% to 30% of prescription drug events in 2009 to 68% to 77% in 2013 (7). This led to a substantial reduction in the overall financial burden of immunosuppressive medications to organ transplant recipients and Medicare Part D. The cost savings to Medicare result from decreases in per-patient Part D plan payments and per-patient Part D low-income subsidy program payments.

This is the first study to document the cost savings to organ transplant recipients and the Medicare program in a large national sample after the introduction of generic immunosuppressive medications. As this study shows, the decrease in costs over time was often substantial. For transplant recipients not receiving the low-income subsidy, we observed declines in average out-of-pocket payments of $1000 to $1750 per patient per year between 2008 and 2013, depending on the organ type and drug. For the Medicare program, we observed savings of $1500 to $4500 per patient per year in Part D plan payments between 2008 and 2013, and additional savings to Medicare of $400 to $1500 per low-income subsidy recipient per year over the same time period. This documentation of cost-savings is relevant to ongoing policy discussions regarding the extension of Medicare coverage of immunosuppressants beyond 36 months post-transplant for kidney transplant recipients not eligible for Medicare on the basis of age or a disability; it could inform evaluations of the cost effectiveness of such a reform.

Ensuring that transplant recipients have consistent access to affordable immunosuppressive medications is critical to the medical and financial wellbeing of patients. Nonadherence with immunosuppressive medications is associated with higher graft loss rates (13–15). In a survey of United States kidney transplant programs investigating cost-related medication nonadherence, >94% of programs described the level of difficulty their patients encounter when paying for their immunosuppressive medications as serious or worse; 83% of programs reported being contacted by patients with concerns about the high cost of medications (16). Other studies have found higher nonadherence rates among individuals with lower socioeconomic status (17–19). Furthermore, return to dialysis after kidney graft failure has high medical, economic, and societal costs related to dialysis and repeat transplantation, competition for scarce deceased donor organs, higher patient mortality, and reduced quality of life while on dialysis. Annual expenses for payers associated with graft failure and subsequent return to dialysis and/or retransplantation are estimated to be between $70,000 and $106,000 compared with approximately $16,000 for patients with a functioning graft (20).

The overall reductions in per-patient payments by beneficiaries and the Medicare Part D program support the hypothesis that the introduction of generic drug products provides economic (i.e., reduced costs to patients and payers) benefits to organ transplant recipients, which may subsequently result in health benefits (i.e., increased access to medications and improved outcomes). Reductions in the out-of-pocket burden of transplant recipients could reduce the prevalence of cost-related medication nonadherence and the associated risks and costs of graft failure. The possibility of longer and more widespread immunosuppressive medication coverage for kidney transplant recipients, such as Medicare coverage for the life of the transplant (21), may be more palatable given reductions in payments for the Medicare program.

This study also highlights the large difference in out-of-pocket payments between transplant recipients who did and did not qualify for the low-income subsidy. Given this substantial difference, we speculate that transplant recipients who do not meet the income eligibility requirements for the full or partial low-income subsidy, but are close to the income cutoffs, may experience financial strain related to the yearly overall out-of-pocket payments for immunosuppressive medications (range $436 to $2279 per year) and that this strain could result in a higher risk of medication nonadherence compared with those that receive the low-income subsidy. Data to support this hypothesis are needed.

In assessing potential cost savings of generic substitution, we documented changes over time in payments specific to brand and generic medications. In contrast to payments for generic and brand tacrolimus, which declined over the study period, Medicare Part D payments for brand mycophenolic acid actually increased over time for the remaining subset of transplant recipients continuing to use these brand-name products. This finding may be explained by increases in brand prices after generic market entry, made possible by a subset of brand-loyal patients (22,23).

One limitation of this study is that it is restricted to Medicare transplant recipients who obtained immunosuppressive medications through Part D. Although Medicare Part B pays for immunosuppressive medications for transplant recipients covered by Medicare Part A at the time of transplant (60%, 30%, and 39% of kidney, liver, and heart transplant recipients, respectively) (9), these analyses cannot be performed using Part B claims because they do not include National Drug Codes required to distinguish between generic and brand medications. Our cost analysis does not include 36 months of coverage by Part B provided to kidney transplant recipients whose transplants are covered by Medicare; immunosuppressant costs may differ between Part B and Medicare Part D plans. Our annualization method assumes no medication nonadherence or dose adjustments over the year, which may not be valid; however, our results can still be interpreted as the payment amount, assuming that the reported regimen was in place for the full year, which has value for counseling potential recipients. Finally, this analysis is limited to post-transplant immunosuppressant costs and does not include other transplant costs, i.e., pretransplant and transplant hospitalization costs, which have been reported elsewhere as ranging from $414,800 to $1,382,400 for the organs studied (24).

This study provides a description of trends in payments for two immunosuppressive medications, tacrolimus and mycophenolic acid (including mycophenolate mofetil and mycophenolate sodium), since the introduction of generic versions of these drugs. Reductions in overall per-patient payments by the Medicare Part D program and transplant recipients during 2009–2013 supports the hypothesis that the introduction of generic versions of these drugs has resulted in substantial cost savings for patients and payers. The cost effect of generic substitution may be amplified by increased competition in the immunosuppressive medication market (25). In addition, we observed large differences in average yearly out-of-pocket payments for immunosuppressive medications between Part D beneficiaries who do and do not qualify for the low-income subsidy. Further research is needed to assess whether there is a potential causal link between recipient immunosuppressive medication payments, adherence, and graft outcomes.

Disclosures

A.B.L. reports grants from the US Food and Drug Administration during the conduct of the study; other from Watermark Research Partners, Inc., Indianapolis, IN, outside the submitted work. M.E.H., M.N.T., J.M.P., R.B., P.S., J.Z., A.B.L., and A.R.S. report grants from the US Food and Drug Administration during the conduct of the study. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Heather Van Doren, senior medical editor with Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, provided editorial assistance on this manuscript.

Funding for this research was made possible by the Food and Drug Administration through grant 1U01FD005274-01. Views expressed in written materials or publications and by speakers and moderators do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Food and Drug Administration or the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does any mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organization imply endorsement by the United States government. The data reported here have been supplied by the Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute (HHRI) as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the United States government. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and from HHRI as the contractor for the SRTR. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from cms.org and SRTR.org with the permission of CMS and HHRI.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.10590918/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Material Title and Authors.

Supplemental Table 1. Demographics for transplant recipients with and without tacrolimus or mycophenolate Part D prescription drug events during 2008 to 2013, by organ type.

Supplemental Table 2. Average (SEM) annualized Medicare Part D plan payments (2013 US dollars).

Supplemental Table 3. Average (SEM) annualized Medicare Part D low-income subsidy payments (2013 US dollars).

Supplemental Table 4. Average (SEM) annualized out-of-pocket payments by patients not receiving the low-income subsidy (2013 US dollars).

Supplemental Table 5. Average (SEM) annualized out-of-pocket payments by patients receiving the low-income subsidy (2013 US dollars).

References

- 1.Loubeau PR, Loubeau JM, Jantzen R: The economics of kidney transplantation versus hemodialysis. Prog Transplant 11: 291–297, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laupacis A, Keown P, Pus N, Krueger H, Ferguson B, Wong C, Muirhead N: A study of the quality of life and cost-utility of renal transplantation. Kidney Int 50: 235–242, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasiske BL, Cohen D, Lucey MR, Neylan JF; American Society of Transplantation : Payment for immunosuppression after organ transplantation. JAMA 283: 2445–2450, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Hajj S, Kim M, Phillips K, Gabardi S: Generic immunosuppression in transplantation: Current evidence and controversial issues. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 11: 659–672, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FDA approval of tacrolimus, 2009. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2009/065461s000ltr.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2018

- 6.FDA approval of mycophenolate mofetil, 2008. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2008/065413s000ltr.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2018

- 7.Liu Q, Smith AR, Park JM, Oguntimein M, Dutcher S, Bello G, Helmuth M, Turenne M, Balkrishnan R, Fava M, Beil CA, Saulles A, Goel S, Sharma P, Leichtman A, Zee J: The adoption of generic immunosuppressant medications in kidney, liver, and heart transplantation among recipients in Colorado or nationally with Medicare part D. Am J Transplant 18: 1764–1773, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips CJ: A health economic perspective on generic therapeutic substitution. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci Pract 20: 290–292, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients : (SRTR). OPTN/SRTR 2016 Annual Data Report, Rockville, MD, Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yen EF, Hardinger K, Brennan DC, Woodward RS, Desai NM, Crippin JS, Gage BF, Schnitzler MA: Cost-effectiveness of extending Medicare coverage of immunosuppressive medications to the life of a kidney transplant. Am J Transplant 4: 1703–1708, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDevitt-Potter LM, Sadaka B, Tichy EM, Rogers CC, Gabardi S: A multicenter experience with generic tacrolimus conversion. Transplantation 92: 653–657, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor: Consumer price index—all urban consumers. Series ID: CUUR0000SA0, Washington, DC, US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014. Available at: http://data.bls.gov/timeseries/CUUR0000SA0. Accessed July 17, 2017

- 13.Schweizer RT, Rovelli M, Palmeri D, Vossler E, Hull D, Bartus S: Noncompliance in organ transplant recipients. Transplantation 49: 374–377, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Geest S, Borgermans L, Gemoets H, Abraham I, Vlaminck H, Evers G, Vanrenterghem Y: Incidence, determinants, and consequences of subclinical noncompliance with immunosuppressive therapy in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 59: 340–347, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinsky BW, Takemoto SK, Lentine KL, Burroughs TE, Schnitzler MA, Salvalaggio PR: Transplant outcomes and economic costs associated with patient noncompliance to immunosuppression. Am J Transplant 9: 2597–2606, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans RW, Applegate WH, Briscoe DM, Cohen DJ, Rorick CC, Murphy BT, Madsen JC: Cost-related immunosuppressive medication nonadherence among kidney transplant recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2323–2328, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frazier PA, Davis-Ali SH, Dahl KE: Correlates of noncompliance among renal transplant recipients. Clin Transplant 8: 550–557, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon EJ, Prohaska TR, Sehgal AR: The financial impact of immunosuppressant expenses on new kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant 22: 738–748, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rovelli M, Palmeri D, Vossler E, Bartus S, Hull D, Schweizer R: Noncompliance in organ transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 21: 833–834, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James A, Mannon RB: The cost of transplant immunosuppressant therapy: Is this sustainable? Curr Transplant Rep 2: 113–121, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.HR 6139. Comprehensive immunosuppressive drug coverage for kidney transplant patients act of 2016. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/6139. Accessed November 20, 2018

- 22.Grabowski HG, Vernon JM: Brand loyalty, entry, and price competition in pharmaceuticals after the 1984 drug act. J Law Econ 35: 331–350, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frank RG, Salkever DS: Generic entry and the pricing of pharmaceuticals. J Econ Manage Strategy 6: 75–90, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milliman research report. 2017 US organ and tissue transplant cost estimates and discussion. Available at: http://us.milliman.com/uploadedFiles/insight/2017/2017-Transplant-Report.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2018

- 25.Dave CV, Hartzema A, Kesselheim AS: Prices of generic drugs associated with numbers of manufacturers. N Engl J Med 377: 2597–2598, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.